Abstract

We developed a PCR-based method to detect and quantify viable Bifidobacterium bifidum BF-1 cells in human feces. This method (PMA-qPCR) uses propidium monoazide (PMA) to distinguish viable from dead cells and quantitative PCR using a BF-1-specific primer set designed from the results of randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis. During long-term culture (10 days), the number of viable BF-1 cells detected by counting the number of CFU on modified MRS agar, by measuring the ATP contents converted to CFU, and by using PMA-qPCR decreased from about 1010 to 106 cells/ml; in contrast, the total number of (viable and dead) BF-1 cells detected by counting 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindolee (DAPI)-stained cells and by using qPCR without PMA and reverse transcription-qPCR remained constant. The number of viable BF-1 cells in fecal samples detected by using PMA-qPCR was highly and significantly correlated with the number of viable BF-1 cells added to the fecal samples, within the range of 105.3 to 1010.3 cells/g feces (wet weight) (r > 0.99, P < 0.001). After 12 healthy subjects ingested 1010.3 to 1011.0 CFU of BF-1 in a fermented milk product daily for 28 days, 104.5 ± 1.5 (mean ± standard deviation [SD]) BF-1 CFU/g was detected in fecal samples by using strain-specific selective agar; in contrast, 106.2 ± 0.4 viable BF-1 cells/g were detected by using PMA-qPCR, and a total of 107.6 ± 0.7 BF-1 cells/g were detected by using qPCR without PMA. Thus, the number of viable BF-1 cells detected by PMA-qPCR was about 50 times higher (P < 0.01) than that detected by the culture-dependent method. We conclude that strain-specific PMA-qPCR can be used to quickly and accurately evaluate viable BF-1 in feces.

INTRODUCTION

In the human gastrointestinal tract, bifidobacteria are a numerically important group of microorganisms that are considered to exert positive influences on biological activities related to host health (1–4). Bifidobacterium bifidum strain YIT 10347 (BF-1) was isolated from B. bifidum YIT 4007 as an oxygen-resistant strain, and it is used as a starter culture for the production of fermented milk products. The consumption of fermented milk containing BF-1 can improve gastric symptoms caused by Helicobacter pylori infection (5), and BF-1 affects regulatory mechanisms in human cells, especially nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) expression, which is induced by H. pylori infection (6).

The generally accepted definition of probiotics was proposed by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) (7). “Probiotics are live microorganisms which when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host.” To determine the effectiveness of probiotics, it is therefore essential to establish a specific method to identify and quantify them (8).

First, we developed a strain-specific method for detecting and identifying BF-1 that was based on a conventional culture method. Because BF-1 is resistant to erythromycin and streptomycin (9), we used a selective agar containing transgalactosylated oligosaccharide-erythromycin-streptomycin (T-EMSM), followed by strain-specific identification of the colonies on the agar plate by random amplified polymorphism DNA (RAPD) fingerprinting (10). Such culture-based methods, however, require considerable time, labor, experience, and skill.

Therefore, there has been increasing interest in the development of rapid PCR-based methods for strain-specific detection (11–13) and cell viability determination (14–17). Recently, a method for the strain-specific quantification of viable cells was reported (18). This method uses a combination of intercalating dye, propidium monoazide (PMA) (which selectively penetrates dead cells through their compromised cell membranes and covalently binds to their DNA under bright visible light), and strain-specific primers for quantitative PCR (qPCR).

Here, we developed a PCR-based procedure for the detection and quantification of viable BF-1 cells in feces. The procedure combines the use of PMA with qPCR using strain-specific primers designed from BF-1-specific sequences derived from RAPD analysis. We used this method to examine changes in the membrane permeability of BF-1 cells in long-term culture and following artificial gastric juice treatment. We also successfully used the technique to quantify viable BF-1 cells in the feces of subjects who had ingested fermented milk containing BF-1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reference strains and culture conditions.

The 127 bacterial strains (30 strains of B. bifidum and 97 strains of other bacteria commonly isolated from human feces) (Table 1) were obtained from the culture collection of the Yakult Central Institute (YIT) (Tokyo, Japan). Anaerobic bacteria were cultured at 37°C for 1 or 2 days in GAM broth (modified “Nissui”; Nissui Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) supplemented with 0.5% glucose. Lactic acid bacteria were cultured in MRS broth (Becton, Dickinson, Sparks, MD) at 37°C for 1 day. Since it was necessary to know the cell count for a quantitative PCR standard, BF-1 cells were stained with 4′,6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) in Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and counted as described by Fujimoto et al. (11).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Genus | Strain(s) |

|---|---|

| Bacteroides | B. caccae YIT 10226T, B. distasonis YIT 6162T, B. eggerthii YIT 10227T, B. fragilis YIT 6158T, B. ovatus YIT 6161T, B. thetaiotaomicron YIT 6163T, B. uniformis YIT 6164T, B. vulgatus YIT 6159T |

| Bifidobacterium | |

| B. bifidum | B. bifidum YIT 4013 (ATCC 15696), YIT 4039T, YIT 4042 (ATCC 11863), YIT 4069, YIT 4070, YIT 10987, YIT 10988, YIT 10990, YIT 10991, YIT 10992, YIT 10993, YIT 10994, YIT 10995, YIT 10996, YIT 10997, YIT 10998, YIT 10999, YIT 11000, YIT 11001, YIT 11002, YIT 11003, YIT 11004, YIT 11005, YIT 11007, YIT 1100, YIT 11009, YIT 11010, YIT 11011, YIT 11012, YIT 10347 (BF-1) |

| Not B. bifidum | B. adolescentis YIT 4011T, B. angulatum YIT 4012T, B. animalis subsp. animalis YIT 4044T, B. animalis subsp. lactis YIT 4121T, B. asteroides YIT 4033T, B. boum YIT 4091T, B. breve YIT 4014T, B. breve YIT 12272, B. catenulatum YIT 4016T, B. choerinum YIT 4067T, B. coryneforme YIT 4092T, B. cuniculi YIT 4093T, B. dentium YIT 4017T, B. gallicum YIT 4085T, B. gallinarum YIT 4094T, B. indicum YIT 4083T, B. longum subsp. infantis YIT 4018T, B. longum subsp. longum YIT 4021T, B. longum subsp. suis YIT 4082T, B. magnum YIT 4098T, B. merycicum YIT 4095T, B. minimum YIT 4097T, B. pseudocatenulatum YIT 4072T, B. pseudolongum subsp. globosum YIT 4101T, B. pseudolongum subsp. pseudolongum YIT 4102T, B. pullorum YIT 4104T, B. ruminantium YIT 4105T, B. saeculare YIT 4111T, B. subtile YIT 4116T, B. thermophilum YIT 4073T |

| Blautia | B. producta YIT 6141T |

| Clostridium | C. acetobutylicum YIT 10170T, C. bifermentans YIT 10228T, C. butyricum YIT 10073T, C. celatum YIT 6056T, C. coccoides YIT 6035T, C. perfringens YIT 6050T |

| Collinsella | C. aerofaciens YIT 10235T |

| Enterococcus | E. faecalis YIT 2031T, E. faecium YIT 2032T |

| Escherichia | E. coli YIT 6044T |

| Eubacterium | E. biforme YIT 6076T, E. rectale YIT 6082T |

| Lactobacillus | L. acidophilus YIT 0070T, L. amylophilus YIT 0255T, L. amylovorus YIT 0211T, L. bifermentans YIT 0260T, L. brevis YIT 0076T, L. buchneri YIT 0077T, L. casei YIT 0078T, L. coryniformis YIT 0237T, L. crispatus YIT 0212T, L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus YIT 0181T, L. delbrueckii subsp. delbrueckii YIT 0080T, L. delbrueckii subsp. lactis YIT 0086T, L. fermentum YIT 0081T, L. gallinarum YIT 0218T, L. gasseri YIT 0192T, L. helveticus YIT 0083T, L. johnsonii YIT 0219T, L. malefermentans YIT 0271T, L. oris YIT 0277T, L. parabuchneri YIT 0272T, L. paracasei YIT 0209T L. paraplantarum YIT 0445T, L. pentosus YIT 0238T, L. plantarum YIT 0102T, L. pontis YIT 0273T, L. reuteri YIT 0197T, L. rhamnosus YIT 0105T, L. sakei YIT 0247T, L. salivarius subsp. salicinius YIT 0089T, L. salivarius subsp. salivarius YIT 0104T, L. sharpeae YIT 0274T, L. vaginalis YIT 0276T |

| Lactococcus | L. garviae YIT 2071T, L. lactis subsp. cremoris YIT 2007T, L. lactis subsp. hordiniae YIT 2060T, L. lactis subsp. lactis YIT 2008T, L. plantarum YIT 2061T, L. raffinolactis YIT 2062T |

| Parascardovia | P. denticolens YIT 4114T |

| Propionibacterium | P. acnes YIT 6165T |

| Ruminococcus | R. bromii YIT 6078T, R. lactaris YIT 6084T |

| Scardovia | S. inopinata YIT 4115T |

| Streptococcus | S. thermophilus YIT 2001, S. thermophilus YIT 2021, S. thermophilus YIT 2037T |

RAPD analysis.

Bacterial DNA for the RAPD analysis was extracted by the physical disruption of cells and benzyl chloride purification, as described previously (11). PCR amplification was performed by using 27 RAPD primers as described by Fujimoto et al. (11). RAPD products were separated by electrophoresis at 50 V in a 1.5% agarose gel.

Cloning and sequence analysis of RAPD products specific to BF-1.

Potential strain-specific RAPD markers were extracted from the agarose gels with the use of a gel indicator DNA extraction kit (BioDynamics Laboratory, Tokyo, Japan). The extracted amplification products were cloned by using pTAC-1 vector and Jet Competent Cells (DH5α) (TA PCR cloning kit; BioDynamics Laboratory). The DNA sequences of 5 clones of each potential strain-specific marker were determined by using an ABI 3130xl DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA) and a BigDye Terminator v3.1 sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems).

Specificity of RAPD-derived primers.

The BF-1-specific primer set (pBF-1) was designed from the potential strain-specific sequences identified by RAPD analysis. The specificity of this primer set was confirmed by PCR analysis of DNA from 127 bacterial strains (Table 1). PCR amplifications were performed in a PTC-200 DNA engine (MJ Research, Waltham, MA) as described previously by Fujimoto et al. (11), with a slight modification. Each reaction mixture (20 μl) contained 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 0.4 U Taq DNA polymerase (TaKaRa Bio, Shiga, Japan), 0.4 μmol primers, and 10 ng template DNA. The amplification program consisted of 1 cycle of 94°C for 2 min, 32 cycles of 94°C for 20 s, 60°C for 10 s, and 72°C for 20 s, and 1 cycle of 72°C for 3 min. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis at 100 V in a 1.5% agarose gel.

PMA treatment.

Pure cultures of BF-1 or fecal samples were treated with 50 μM PMA (Biotium, Inc., CA) and underwent photoactivation for 2 min as described by Fujimoto et al. (18). The PMA-treated cell pellets were preserved at −20°C until DNA extraction was performed.

Quantification of ATP content of samples.

The ATP content of each sample tested was measured using an ATP-luciferase reaction kit (Lucifer HS; Kikkoman, Chiba, Japan), based on the firefly luciferin-luciferase reaction (19), and a luminescence-measuring instrument, TD-20/20 (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. ATP content was measured in relative light units (RLU). To convert RLU to CFU, we used the ratio (RLU/CFU) obtained from BF-1 that was cultured anaerobically at 37°C for 24 h in modified MRS (m-MRS) (glucose replaced with lactose) broth containing (per liter) 10 g BBL Trypticase peptone (BD, Sparks, MD), 5 g yeast extract, 3 g Bacto tryptose (BD), 3.9 g K2HPO4·3H2O, 3 g KH2PO4, 2 g diammonium hydrogen citrate, 5 ml salt solution (11.5% [wt/vol] MgSO4·7H2O, 3.09% MnSO4·5H2O, 0.68% FeSO4·7H2O), 1 g Tween 80, 1.7 g sodium acetate, 10 g lactose, and 0.2 g l-cysteine HCl·H2O (20). The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 4 min at 4°C and suspended in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The samples were stored at −80°C until further use. The number of CFU of BF-1 were determined by using an m-MRS agar plate cultured anaerobically at 37°C for 72 h.

Extraction of nucleic acid from BF-1 cells.

The bacterial culture (250 μl) was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and the pellet was suspended in 500 μl RNAlater solution (Ambion, Austin, TX) to stabilize the RNA. After incubation at 4°C for 1 h, the solution was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and the pellet was stored at −80°C until nucleic acid extraction. The pellet was vortexed with 250 μl of extraction buffer (100 mM Tris, 40 mM EDTA disodium salt [pH 9.0]), 500 μl of Tris-EDTA (TE)-saturated phenol (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan), 50 μl of 10% SDS, and glass beads (700 mg; 0.1 mm in diameter) (Shinmaru Enterprises, Osaka, Japan) by using a FastPrep 24 instrument (MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA) at a speed of 6.5 m/s for 30 s at room temperature. We added 100 μl of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 4.8) to the suspension and incubated it on ice for 5 min. The suspension was then centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 8 min at 4°C, and the supernatant (400 μl) was mixed with 400 μl ice-cold 100% isopropanol. After centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 8 min at 4°C, the pelleted nucleic acids were washed in ice-cold 70% ethanol and air-dried prior to suspension in 250 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]).

Quantification of BF-1 cells by using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR and quantitative PCR.

For the quantification of viable BF-1 cells, real-time reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis was conducted in two steps. In the first step, reverse transcription was performed with the use of a TaKaRa RNA PCR kit (AMV) version 3.0 (TaKaRa Bio). The template nucleic acids were diluted 1:50 before use. Each reaction mixture (10 μl) contained 1 μl of template nucleic acids, 1× RT Buffer, 1 mM dNTP mixture, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 U RNase inhibitor, 2.5 U AMV reverse transcriptase XL, and 1 μM reverse primer (B. bifidum species specific; BiBIF-2) (21). The reaction was performed at 52°C for 20 min, and then the reaction mixture was heated to 95°C for 10 min and quick-chilled on ice. In the second step, qPCR was performed with the use of an ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems), as described previously (18), with slight modifications. The reaction mixture (20 μl) contained 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM each dNTP, 0.2 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (TaKaRa Bio), a 1:75,000 dilution of SYBR green I (Invitrogen), 0.4 U Taq DNA polymerase Hot Start version (TaKaRa Bio), 0.4 μmol of each of the B. bifidum species-specific primers (BiBIF-F and BiBIF-R) (21), and 5 μl of template cDNA that had been diluted 10-, 102-, or 103-fold. The amplification program consisted of an initial heating step at 94°C for 5 min, 40 cycles of 94°C for 20 s, 55°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 50 s, and a final extension step at 72°C for 3 min. Fluorescence intensities were detected during the last step of each cycle. To distinguish the targeted PCR product from nontargeted PCR products (22), RT-qPCR melting curves were obtained after the amplification by continuously collecting fluorescence intensity measurements as the reaction mixture was slowly heated from 60 to 95°C in increments of 0.2°C/s.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis was performed to quantify the total number of BF-1 cells (without PMA treatment) or viable BF-1 cells (with PMA treatment) using an ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems), as described above, as the second step of RT-qPCR, with slight modifications: the qPCR was performed with pBF-1, and the annealing temperature was changed to 60°C for 10 s.

Long-term culture and artificial gastric juice treatment of BF-1 cells.

Long-term culture was performed as follows. After preincubation in m-MRS broth anaerobically at 37°C for 24 h, B. bifidum BF-1 culture was inoculated onto 4 ml of m-MRS broth (1%, vol/vol) and cultured anaerobically at 37°C for 1, 2, 4, 7, or 10 days.

Artificial gastric juice treatment was performed as follows. After preincubation at 37°C for 24 h, the BF-1 culture was inoculated onto 16 ml of m-MRS broth (1% vol/vol) and cultured anaerobically at 37°C for 24 h. The BF-1 cells were harvested by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C and suspended in 16 ml of artificial gastric juice. The artificial gastric juice was prepared by supplementing the basal medium (pH 2.8) with pepsin as follows: 900 ml of basal medium (5.0 g/liter Trypticase peptone, 1.5 g/liter mucin from porcine stomach [Wako Pure Chemical Industries], 5.0 g/liter NaCl, 3.0 g/liter NaHCO3, 1.0 g/liter KH2PO4, adjusted to pH 2.8 with 1 N HCl) was autoclaved for 15 min at 115°C and then supplemented with 100 ml of filter-sterilized 400 mg/liter pepsin solution (pepsin diluted 1:10,000 from porcine stomach mucosa [Wako Pure Chemical Industries]). BF-1 cells suspended in artificial gastric juice were cultured aerobically at 37°C for 1, 2, or 3 h.

Quantification of BF-1 cells added to fecal samples.

Fecal samples were collected in individual sterile feces containers (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany), refrigerated at 4°C, and taken to the laboratory within 4 h. The total concentration of intestinal microorganisms obtained by counting DAPI-stained cells (DAPI count) was 1011.1 ± 0.2 (mean ± SD)/g feces (wet weight). We added viable or heat-killed (80°C for 10 min) BF-1 cells at an estimated (by DAPI count) concentration of 1010.3 cells/g feces (wet weight) to 3 fecal samples (200 μl of 10-fold-diluted suspension) (from different volunteers) containing no BF-1 that were confirmed by using a culture method with a BF-1 strain-specific T-EMSM selective agar (described below) and strain-specific qPCR with pBF-1. Then, viable BF-1 cells were added to 2 fecal samples (200 μl of a 10-fold-diluted suspension) (from different volunteers) containing no BF-1 to give final concentrations ranging from 104.3 to 1010.3 cells/g. After PMA treatment, the DNA was extracted as described previously (11) from each sample and subjected to qPCR analysis using the pBF-1.

Examination of fecal samples produced after ingestion of BF-1.

The study population comprised 12 healthy volunteers (age range, 25 to 60 years; mean ± SD, 45.5 ± 11.3 years). The subjects ingested a commercially available fermented milk product (BF-1) containing 1010.3 to 1011.0 CFU BF-1/bottle, once daily for 28 days. Fecal samples excreted before and after ingestion of the fermented milk product were collected in individual sterile feces containers (Sarstedt), refrigerated at 4°C, and taken to the laboratory within 4 h. No subject ingested probiotic products, including the study product, during the 2-week period before the commencement of this study. Informed consent was obtained from all volunteers who provided fecal samples. The ethics committee of the Oriental Ueno Health Promotion Center (Tokyo, Japan) provided ethical clearance for this microbiological research study in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Quantitative detection of ingested BF-1 in feces by qPCR.

The DNA from fecal samples was extracted by using a stool mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), as described previously (18). The qPCR method with PMA or without PMA was performed to quantify the viable or total (viable plus dead) BF-1 cells in the feces of subjects who drank a fermented milk product containing BF-1, according to the method described previously (18), using pBF-1.

Quantification of BF-1 cells by culturing on T-EMSM selective agar.

Counts (in CFU) of BF-1 were determined by using a strain-specific T-EMSM selective agar plate that contained transgalactosylated oligosaccharide (TOS) as a growth factor and erythromycin (EM) and streptomycin (SM) as selective agents for BF-1 (8). The T-EMSM selective agar was based on commercially available TOS propionate agar medium (Yakult Pharmaceutical Industry, Tokyo, Japan) and consisted of (per liter) 10 g Trypticase, 1.0 g yeast extract, 3.0 g KH2PO4, 4.8 g K2HPO4, 3.0 g (NH4)2SO4, 0.2 g MgSO4, 0.5 g l-cysteine, 15 g sodium propionate, 10 g TOS, 15 g powdered agar, 50 mg erythromycin (Wako Pure Chemical Industries), and 5,000,000 U streptomycin sulfate (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO). Aliquots (100 μl each) of 10-fold serial dilutions of feces (starting sample, 0.5 g) in 0.85% NaCl were spread on T-EMSM agar and incubated anaerobically at 37°C for 72 h in an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products, Grass Lake, MI) (under an atmosphere comprising 91:6:3 N2/CO2/H2). For each fecal sample, we isolated colonies from the T-EMSM plate that was inoculated with the highest dilution that yielded growth and subjected these colonies to PCR analysis using the pBF-1. The number of BF-1 cells/g feces was estimated from the number of colonies that were identified as BF-1 by PCR analysis with the pBF-1. All isolates were also analyzed by RAPD analysis.

Statistical methods.

Differences in the concentrations of BF-1 added to the fecal samples measured by qPCR were analyzed by the paired Student t test. Simple linear regression was used to develop regression equations for statistically significant relationships. Pearson's correlation coefficients were used to determine the correlations between the number of BF-1 cells added to the fecal samples and the BF-1 cell counts determined by qPCR. Tukey's method was used to determine the correlations between the numbers of BF-1 cells detected in the fecal samples produced after the ingestion of a BF-1-containing fermented milk product by using three methods (T-EMSM selective agar-based culture, PMA-qPCR, and qPCR without PMA). P values of <0.05 were classified as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Screening for strain-specific RAPD markers.

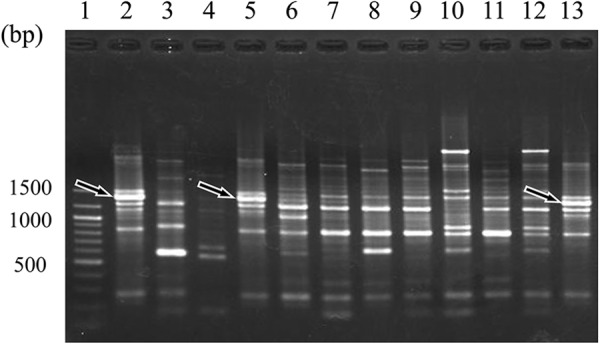

To identify a strain-specific marker for BF-1, we tested a total of 27 RAPD primers on 30 B. bifidum strains and analyzed the specificities of the resultant PCR products. Primer OPA11 (5′ CAA TCG CCG T 3′) generated a 1.4-kb BF-1-specific PCR product (Fig. 1). We determined the sequence of this BF-1-specific PCR product (DDBJ accession no. AB748455).

Fig 1.

RAPD patterns obtained from 10 B. bifidum strains with the use of OPA11 primer. Lane 1, 100-bp DNA size marker; lanes 2, 5, and 13, B. bifidum BF-1; lane 3, YIT 4013; lane 4, YIT 4039T; lane 6, YIT 4042; lane 7, YIT 4069; lane 8, YIT 4070; lane 9, YIT 10990; lane 10, YIT 10994; lane 11, YIT 10996; lane 12, YIT 10999. Arrows indicate bands corresponding to a BF-1-specific PCR product.

Design of a specific RAPD-derived primer pair.

Based on the sequence of the BF-1-specific PCR product, we designed BF-1-specific primers (pBF-1 [pBF-1f, 5′ ATG GCA AAA CCG GGC TGA A 3′, and pBF-1r, 5′ GCG GAT GAG AGG TGG G 3′]). We tested the specificities of these primers against DNA extracted from 127 bacterial strains, including 30 strains of B. bifidum (Table 1). The primers exclusively supported PCR amplification of BF-1 template DNA, with no amplification against nontarget microorganisms (data not shown). The amplification product was 697 bp in length and had two melting temperatures of 89.3°C (main) and 86.7°C.

Quantitative PCR detection of viable or heat-killed BF-1 cells in feces.

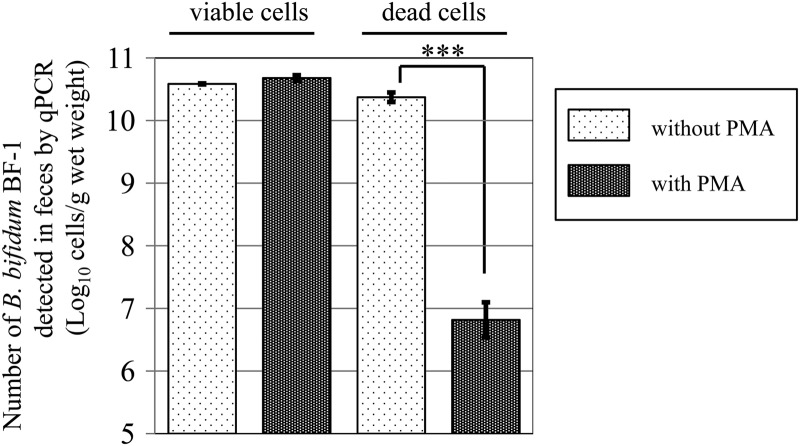

When viable BF-1 was added to the fecal samples, the counts of BF-1 cells obtained by PMA-qPCR (50 μM PMA solution and 2 min photoactivation) were similar to those obtained by qPCR without PMA treatment (Fig. 2). In contrast, in the case of heat-killed BF-1 cells added to the fecal samples, the use of PMA-qPCR resulted in a significantly reduced count of BF-1 cells (106.8 ± 0.3 cells/ml) (P < 0.001) compared to that obtained without PMA treatment (1010.4 ± 0.1 cells/ml) (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Effect of PMA treatment on quantitative real-time PCR amplification of heat-killed BF-1 cells in human feces. Viable or heat-killed BF-1 cells (80°C, 10 min) were introduced into human fecal samples and the cells were quantitated by real-time PCR with or without PMA treatment. ***, P < 0.001 for PMA treatment versus no PMA treatment. Data are the mean ± SD (from 3 independent experiments).

Accuracy of PMA-qPCR method for quantitative determination of viable BF-1 cells in feces.

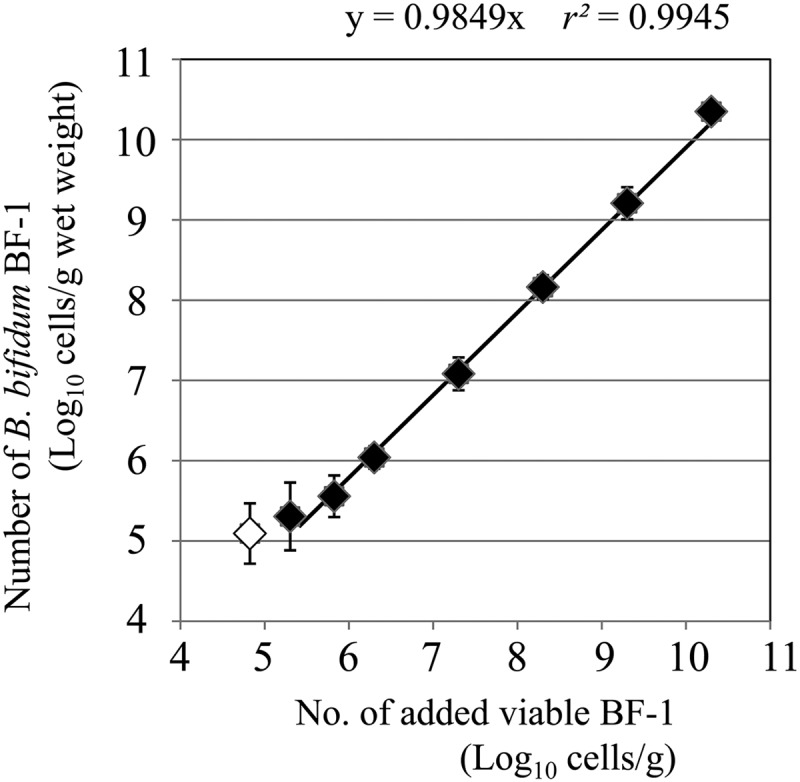

We added viable BF-1 directly to 200 μl of 10-fold-diluted fecal samples in amounts ranging from 104.3 to 1010.3 cells/g feces (wet weight) and determined the number of BF-1 cells by using PMA-qPCR with pBF-1. Amplification products were not always detected for samples with 104.8 cells/g feces, so this amount was deemed to be below the limit of detection. When the amount of viable BF-1 cells added was 105.3 to 1010.3 cells/g feces (wet weight), the PMA-qPCR results significantly correlated with the number of added viable BF-1 cells (r > 0.99, P < 0.001; Fig. 3), suggesting that the PMA-qPCR method accurately determined the number of viable BF-1 cells, without any inhibitions, to amplify viable BF-1 cells.

Fig 3.

Correlation between the number of viable BF-1 cells added to fecal samples and the number determined by real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) with PMA. The regression line was made between 105.3 cells/g and 1010.3 cells/g (wet weight), as detected by qPCR, because amplification products were not always detected with an input of 104.8 cells/g (open diamond). The regression line was calculated with an intercept of 0. Each error bar represents the standard deviation from three independent tests.

PMA-qPCR detection of viable BF-1 cells in long-term and artificial gastric juice-treated cultures.

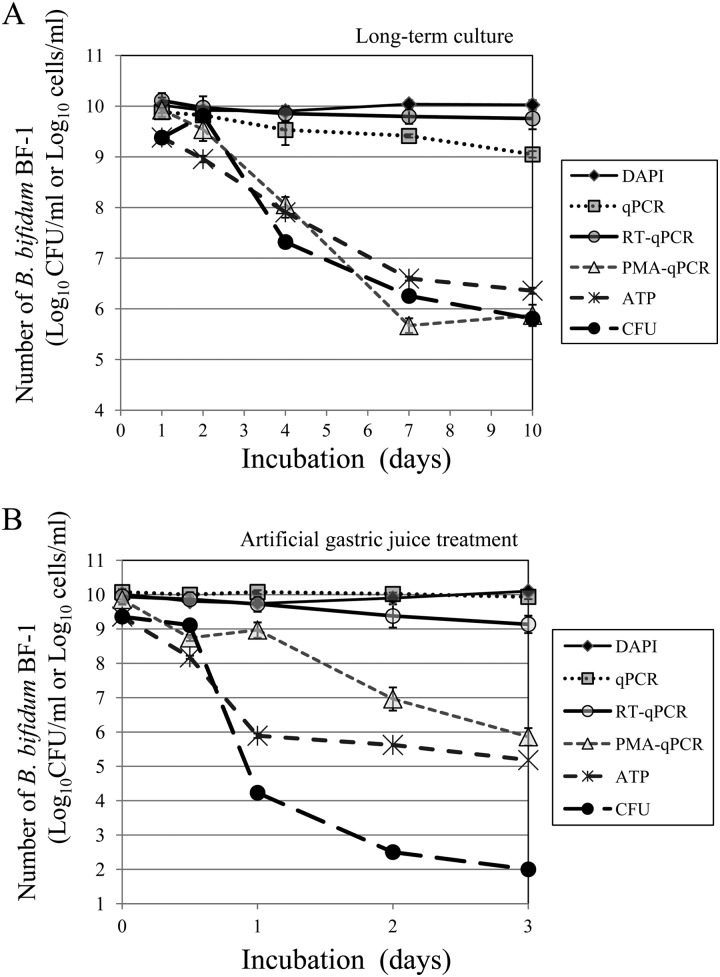

During long-term culture (10 days), the total number of BF-1 cells determined by a DAPI count or RT-qPCR remained constant at about 1010 cells/ml, and the number determined by qPCR without PMA treatment decreased slowly to about 109 cells/ml. In contrast, the numbers of viable BF-1 cells determined by PMA-qPCR, by measurement of the ATP contents that were converted to CFU, and by the culture method employing m-MRS agar all decreased dramatically to a similar final level of 106 cells/ml or CFU/ml (Fig. 4A).

Fig 4.

Use of real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) with PMA and other methods to determine the number of BF-1 cells during long-term culture in m-MRS broth or artificial gastric juice. Cells were cultured long-term (10 days) in m-MRS broth at 37°C (A) or treated with artificial gastric juice at 37°C for 3 h (B), and the cell numbers were assayed by various methods at the specified time points. The methods were DAPI count (DAPI), qPCR with pBF-1 but no PMA treatment of cells before DNA extraction (qPCR), RT-qPCR targeting of B. bifidum-specific 16S rRNA sequences (RT-qPCR), qPCR with pBF-1 and PMA treatment of cells before DNA extraction (PMA-qPCR), measurement of ATP content as RLU converted to CFU (ATP), and culturing of cells on T-EMSM selective agar (CFU).

During the first hour of treatment with artificial gastric juice, the numbers of viable BF-1 cells determined by measuring ATP content and by the m-MRS-based culture method decreased rapidly from 109.4 to 105.9 CFU/ml and from 109.4 to 104.2 CFU/ml, respectively, whereas the number of viable BF-1 cells determined by PMA-qPCR decreased slowly from 109.9 to 109.0 cells/ml. During the entire 3-h treatment, the number of viable BF-1 cells determined by PMA-qPCR decreased to 106 cells/ml. In contrast, the number of viable BF-1 cells determined by the m-MRS-based culture method decreased rapidly to 102 CFU/ml, and the number of viable BF-1 cells determined by RT-qPCR targeting of BF-1-specific 16S rRNA sequences decreased slightly from 109.9 to 109.1 cells/ml (Fig. 4B).

Selectivity of BF-1 strain-specific T-EMSM selective agar.

To determine the performance of the T-EMSM selective agar, equal amounts of BF-1 cells sampled from BF-1 cells cultured overnight in m-MRS broth and fermented milk product containing BF-1 were separately inoculated onto T-EMSM agar plates or TOS propionate agar plates. In both the pure cultures and the fermented milk, BF-1 formed large milky-white smooth colonies on the T-EMSM agar plate, and there was no significant difference between the numbers of colonies on the T-EMSM agar plate and on the TOS propionate agar plate (unpaired Student's t test) (Table 2). When fecal samples taken from subjects prior to ingestion of the fermented milk were inoculated onto T-EMSM agar plates, some colonies grew on the selective medium; however, these colonies could be distinguished from BF-1 colonies by size or color and were confirmed to be non-BF-1 by PCR using pBF-1 and RAPD analysis (data not shown).

Table 2.

Comparison of recoveries of BF-1 by T-EMSM selective medium and nonselective medium (TOS propionate agar medium)

| Agar medium | Mean amount (log CFU/ml ± SD) in: |

|

|---|---|---|

| Pure culture of BF-1 | Fermented milk containing BF-1 | |

| T-EMSM | 9.34 ± 0.03 | 9.01 ± 0.05 |

| TOS propionate | 9.33 ± 0.02 | 8.97 ± 0.07 |

Quantitative detection of ingested BF-1 in feces.

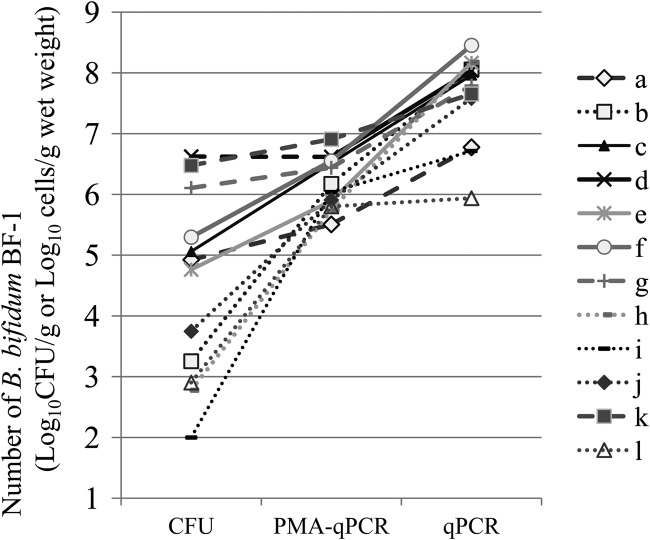

We used our PMA-qPCR method to measure the number of viable BF-1 cells in the fecal samples of subjects who drank fermented milk product containing BF-1. Before ingestion of the fermented milk product, the number of BF-1 cells in the fecal samples was below the detection limit for the strain-specific qPCR method without PMA treatment (<105.3 cells/g feces [wet weight]) and the conventional culturing method employing a T-EMSM agar plate (<102.0 CFU/g). After ingestion of the fermented milk, BF-1 was detected in the fecal samples of all subjects at concentrations of 107.6 ± 0.7 cells/g by qPCR without PMA treatment and 106.2 ± 0.4 cells/g by PMA-qPCR. In addition, BF-1 was isolated from all subjects at a concentration of 104.5 ± 1.5 CFU/g by using a T-EMSM agar plate (Table 3).

Table 3.

Number of BF-1 cells in the feces of 12 volunteers who ingested a fermented milk product containing BF-1 for 28 days

| Subject | No. of BF-1 cells (log cells/g feces or log CFU/g feces [wet weight]) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantified before ingestiona |

Quantified after ingestion |

|||||

| qPCRb |

Culture | qPCR |

Culture | |||

| Without PMA | With PMA | Without PMA | With PMA | |||

| a | <5.3 | <5.3 | <2 | 6.8 | 5.5 | 4.9 |

| b | <5.3 | <5.3 | <2 | 8.1 | 6.2 | 3.3 |

| c | <5.3 | <5.3 | <2 | 8.0 | 6.5 | 5.1 |

| d | <5.3 | <5.3 | <2 | 8.0 | 6.6 | 6.6 |

| e | <5.3 | <5.3 | <2 | 8.2 | 5.9 | 4.8 |

| f | <5.3 | <5.3 | <2 | 8.5 | 6.6 | 5.3 |

| g | <5.3 | <5.3 | <2 | 7.8 | 6.4 | 6.1 |

| h | <5.3 | <5.3 | <2 | 8.2 | 5.7 | 2.8 |

| i | <5.3 | <5.3 | <2 | 6.7 | 6.0 | 2.0 |

| j | <5.3 | <5.3 | <2 | 7.6 | 5.9 | 3.7 |

| k | <5.3 | <5.3 | <2 | 7.7 | 6.9 | 6.5 |

| l | <5.3 | <5.3 | <2 | 5.9 | 5.8 | 2.9 |

The lower limits of detection of qPCR and the culture method were 105.3 cells/g feces (wet weight) and 102.0 CFU/g feces, respectively.

PMA, propidium monoazide; qPCR, real-time quantitative PCR.

DISCUSSION

Due to the disadvantages of conventional microbiological methods, e.g., underestimation by using selective reagents, the clumping of bacterial cells, or the need for laborious process and skills, bacterial quantification based on PCR detection of nucleic acids is increasingly being used (11, 23–25). Here, we confirmed that the RAPD technique is one of the best methods for developing strain-specific primers for use in qPCR analysis. As noted by Briczinski et al. (26) and Fujimoto et al. (18), RAPD can comprehensively compare the whole genomes of many strains to easily and rapidly find strain-specific sequences.

The use of DNA-based molecular detection tools for bacteria has been hampered by the inability to distinguish signals originating from viable and dead cells; recently, however, the differentiation of viable and dead cells in samples with several types of bacteria has been accomplished with methods that PCR-amplify DNA from cells that have been treated with ethidium monoazide (EMA) or PMA (27–30). However, EMA has been suggested to be toxic to some viable cells (15). When BF-1 cells that were heat killed by treatment at 80°C for 10 min (18) were introduced into fecal samples, the number of BF-1 cells detected in the feces by PMA-qPCR was 1/10,000 of that detected without PMA treatment (Fig. 2). This result confirmed that PMA-qPCR detected only viable cells from the negligible amount of amplification of dead cells. We also demonstrated the accuracy of PMA-qPCR by confirming that the counts of BF-1 in feces analyzed by PMA-qPCR were highly and significantly correlated with the number of viable BF-1 cells added to the fecal samples (Fig. 3).

We compared the changes in the numbers of BF-1 viable cells determined by various methods (T-EMSM selective agar-based culture, ATP content measurement, RT-qPCR targeting of B. bifidum-specific 16S rRNA sequences, and PMA-qPCR) when the cells were subjected to moderately slow death by long-term cultivation and rapid death by artificial gastric juice treatment. After long-term cultivation, the number of viable BF-1 cells determined by PMA-qPCR was similar to the numbers determined by T-EMSM selective agar-based culture and measurement of ATP contents converted to CFU (Fig. 4A). In contrast, during treatment with artificial gastric juice, the number of viable BF-1 cells determined by PMA-qPCR, which is dictated by membrane permeability, began to decrease 1 h later than the numbers determined by a T-EMSM selective agar-based culture and measurement of ATP contents converted to CFU (Fig. 4B). The T-EMSM selective agar-based culture method has the inherent disadvantage of the underestimation of viable microbes because of the use of antibiotics or the clumping of cells. The method for quantifying ATP content also has disadvantages; it cannot be used to target specific bacterial strains in complex environmental samples, such as feces. In addition, contrary to our expectations, the RT-qPCR method, which targets B. bifidum-specific 16S rRNA sequences and is believed to quantify only viable cells only in some bacterial species (31, 32), did not successfully discriminate between viable and dead BF-1 cells (Fig. 4). Lahtinen et al. (33) demonstrated that viable but nonculturable probiotics maintain high levels of rRNA and retain viable properties. In our study, the rRNA contents of BF-1 did not change or experience a slight reduction after either long-term culture or treatment with artificial gastric juice, whereas other properties of viability (CFU assayed by T-EMSM selective agar-based culture, measurement of ATP content, and membrane integrity assayed by PMA-qPCR) were decreased. Our results suggest that the rRNA of BF-1 is retained after the cells lose their viability. Therefore, we consider PMA-qPCR to be the best way to rapidly and accurately quantify viable BF-1 cells.

To exert the expected positive effects, the basic requirement for probiotic strains is that they remain alive in the digestive tract (34). Here, we demonstrated that ingested BF-1 was detectable as viable cells in human fecal samples by using T-EMSM selective agar and RAPD fingerprinting. We used PCR with pBF-1 to identify 74 colonies that appeared on the T-EMSM agar plates at the highest fecal dilution that yielded growth. Forty-nine isolates that formed large milky-white smooth colonies were identified as B. bifidum by using pBF-1 and RAPD analysis, and the remaining 25 isolates formed colonies smaller than those of BF-1; gray or ocher colonies were confirmed as non-BF-1 by both methods. Thus, PCR using pBF-1 enabled us to identify BF-1 colonies on the T-EMSM selective agar efficiently and accurately. It also enabled us to reduce the laborious process of identification, including the isolation and purification of isolates, and RAPD analysis.

After subjects ingested fermented milk product containing BF-1, the total number of BF-1 cells in their fecal samples determined by using qPCR without PMA treatment was 107.6 ± 0.7 cells/g, but the number of viable BF-1 cells determined by PMA-qPCR was 106.2 ± 0.4 cells/g. This result suggests that about 11% (the average BF-1 ratio of PMA-qPCR to qPCR in 12 subjects) of the total BF-1 cells in the fecal samples were still viable after passing though the digestive tract, when viability was assayed in terms of integrity of the cell membrane. The number of viable BF-1 cells determined by PMA-qPCR was 50 times higher (P < 0.01) than that determined by the T-EMSM selective agar-based culture method, suggesting that the use of antibiotics in the culture-dependent method might lead to the underestimation of the number of viable BF-1 cells, even when the minimum amount of antibiotics required for selection (erythromycin and streptomycin at 5,000 μg/ml and 50 μg/ml, respectively [9]) was used.

After the subjects ingested the fermented milk product containing BF-1 for 28 days, the numbers of BF-1 cells in the fecal samples were compared between subjects (Fig. 5). The numbers of viable BF-1 cells detected by the T-EMSM selective agar-based culture method ranged from 102.0 to 106.6 CFU/g among the subjects; in contrast, the numbers determined by the PMA-qPCR method showed a smaller range of 105.5 to 106.9 cells/g. The numbers of viable BF-1 cells determined by PMA-qPCR in 5 of the 12 subjects (b, h, i, j, and l) were >100 times higher (P < 0.01) than those determined by T-EMSM selective agar-based culture (Fig. 5, dotted lines). In contrast, the numbers of viable BF-1 cells determined by PMA-qPCR in the other seven subjects (a, c, d, e, f, g, and k) were almost at the same level as those determined by T-EMSM selective agar-based culture (Fig. 5, dashed lines). Thus, intersubject differences in the recovery of viable BF-1 cells by T-EMSM selective agar-based culture may be due to differences in the magnitude of increased membrane permeability (reflected in the differences in the PMA-qPCR results) and decreased colony-forming ability of BF-1 during its transit in the gastrointestinal tract in each individual. Further studies are required to understand the survival mechanisms of BF-1 in different compartments of the digestive tract and the influence of different parameters on these mechanisms.

Fig 5.

Number of BF-1 cells in the feces of 12 volunteers who ingested a fermented milk product for 28 days. The dashed line represents the volunteer whose number of viable BF-1 cells determined by the PMA-qPCR was 10 times less than that determined by the T-EMSM selective agar-based culture. The dotted line represents the volunteer whose number of BF-1 cells determined by PMA-qPCR was 100 times higher (P < 0.01) than that determined by the T-EMSM selective agar-based culture.

In conclusion, the BF-1-specific PCR primer set, pBF-1, which we developed in this study, enabled the efficient and accurate identification of colonies that formed on T-EMSM agar. We confirmed that combining PMA treatment of samples before DNA extraction and quantitative PCR with the pBF-1 could be used to quickly and accurately analyze the number of viable BF-1 cells in fecal samples. We believe that the PMA-qPCR methodology we have described here will be a powerful tool in future studies for understanding the use of BF-1 as a probiotic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate the support provided by Atsushi Gomi for fecal sampling. We also thank Tohru Iino and Yasuhisa Shimakawa for their understanding and encouragement throughout our research activities.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 25 January 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Collins MD, Gibson GR. 1999. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics: approaches for modulating the microbial ecology of the gut. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 69(Suppl): 1052S–1057S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kleerebezem M, Vaughan EE. 2009. Probiotic and gut lactobacilli and bifidobacteria: molecular approaches to study diversity and activity. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 63: 269–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Leahy SC, Higgins DG, Fitzgerald GF, van Sinderen D. 2005. Getting better with bifidobacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 98: 1303–1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Turroni F, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. 2011. Genomics and ecological overview of the genus Bifidobacterium. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 149: 37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Miki K, Urita Y, Ishikawa F, Iino T, Shibahara-Sone H, Akahoshi R, Mizusawa S, Nose A, Nozaki D, Hirano K, Nonaka C, Yokokura T. 2007. Effect of Bifidobacterium bifidum fermented milk on Helicobacter pylori and serum pepsinogen levels in humans. J. Dairy Sci. 90: 2630–2640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shirasawa Y, Shibahara-Sone H, Iino T, Ishikawa F. 2010. Bifidobacterium bifidum BF-1 suppresses Helicobacter pylori-induced genes in human epithelial cells. J. Dairy Sci. 93: 4526–4534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. FAO/WHO 2001. Health and nutritional properties of probiotics in food including powder milk with live lactic acid bacteria. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and World Health Organization, Cordoba, Argentina [Google Scholar]

- 8. Klaenhammer TR, Kullen MJ. 1999. Selection and design of probiotics. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 50: 45–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sato T, Iino T. 2010. Genetic analyses of the antibiotic resistance of Bifidobacterium bifidum strain Yakult YIT 4007. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 137: 254–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Williams JG, Kubelik AR, Livak KJ, Rafalski JA, Tingey SV. 1990. DNA polymorphisms amplified by arbitrary primers are useful as genetic markers. Nucleic Acids Res. 18: 6531–6535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fujimoto J, Matsuki T, Sasamoto M, Tomii Y, Watanabe K. 2008. Identification and quantification of Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota in human feces with strain-specific primers derived from randomly amplified polymorphic DNA. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 126: 210–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peng M, Smith AH, Rehberger TG. 2011. Quantification of Propionibacterium acidipropionici P169 bacteria in environmental samples by use of strain-specific primers derived by suppressive subtractive hybridization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77: 3898–3902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xiang SR, Cook M, Saucier S, Gillespie P, Socha R, Scroggins R, Beaudette LA. 2010. Development of amplified fragment length polymorphism-derived functional strain-specific markers to assess the persistence of 10 bacterial strains in soil microcosms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76: 7126–7135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nocker A, Camper AK. 2009. Novel approaches toward preferential detection of viable cells using nucleic acid amplification techniques. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 291: 137–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nocker A, Cheung CY, Camper AK. 2006. Comparison of propidium monoazide with ethidium monoazide for differentiation of live vs. dead bacteria by selective removal of DNA from dead cells. J. Microbiol. Methods 67: 310–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Taskin B, Gozen AG, Duran M. 2011. Selective quantification of viable Escherichia coli bacteria in biosolids by quantitative PCR with propidium monoazide modification. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77: 4329–4335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Varma M, Field R, Stinson M, Rukovets B, Wymer L, Haugland R. 2009. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of total and propidium monoazide-resistant fecal indicator bacteria in wastewater. Water Res. 43: 4790–4801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fujimoto J, Tanigawa K, Kudo Y, Makino H, Watanabe K. 2011. Identification and quantification of viable Bifidobacterium breve strain Yakult in human faeces by using strain-specific primers and propidium monoazide. J. Appl. Microbiol. 110: 209–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sakakibara T, Murakami S, Hattori N, Nakajima M, Imai K. 1997. Enzymatic treatment to eliminate the extracellular ATP for improving the detectability of bacterial intracellular ATP. Anal. Biochem. 250: 157–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Watanabe K, Fujimoto J, Sasamoto M, Dugersuren J, Tumursuh T, Demberel S. 2008. Diversity of lactic acid bacteria and yeasts in Airag and Tarag, traditional fermented milk products of Mongolia. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 24: 1313–1325 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Matsuki T, Watanabe K, Tanaka R, Fukuda M, Oyaizu H. 1999. Distribution of bifidobacterial species in human intestinal microflora examined with 16S rRNA-gene-targeted species-specific primers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65: 4506–4512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ririe KM, Rasmussen RP, Wittwer CT. 1997. Product differentiation by analysis of DNA melting curves during the polymerase chain reaction. Anal. Biochem. 245: 154–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ahlroos T, Tynkkynen S. 2009. Quantitative strain-specific detection of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in human faecal samples by real-time PCR. J. Appl. Microbiol. 106: 506–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maruo T, Sakamoto M, Toda T, Benno Y. 2006. Monitoring the cell number of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris FC in human feces by real-time PCR with strain-specific primers designed using the RAPD technique. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 110: 69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ndoye B, Lessard MH, LaPointe G, Roy D. 2011. Exploring suppression subtractive hybridization (SSH) for discriminating Lactococcus lactis ssp. cremoris SK11 and ATCC 19257 in mixed culture based on the expression of strain-specific genes. J. Appl. Microbiol. 110: 499–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Briczinski EP, Loquasto JR, Barrangou R, Dudley EG, Roberts AM, Roberts RF. 2009. Strain-specific genotyping of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis by using single-nucleotide polymorphisms, insertions, and deletions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75: 7501–7508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fittipaldi M, Codony F, Adrados B, Camper AK, Morató J. 2010. Viable real-time PCR in environmental samples: can all data be interpreted directly? Microb. Ecol. 61: 7–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kramer M, Obermajer N, Bogovic Matijasić B, Rogelj I, Kmetec V. 2009. Quantification of live and dead probiotic bacteria in lyophilised product by real-time PCR and by flow cytometry. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 84: 1137–1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Meng XC, Pang R, Wang C, Wang LQ. 2010. Rapid and direct quantitative detection of viable bifidobacteria in probiotic yogurt by combination of ethidium monoazide and real-time PCR using a molecular beacon approach. J. Dairy Res. 77: 498–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nocker A, Richter-Heitmann T, Montijn R, Schuren F, Kort R. 2010. Discrimination between live and dead cells in bacterial communities from environmental water samples analyzed by 454 pyrosequencing. Int. Microbiol. 13: 59–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Matsuda K, Tsuji H, Asahara T, Kado Y, Nomoto K. 2007. Sensitive quantitative detection of commensal bacteria by rRNA-targeted reverse transcription-PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73: 32–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McKillip JL, Jaykus LA, Drake M. 1999. Nucleic acid persistence in heat-killed Escherichia coli O157:H7 from contaminated skim milk. J. Food Prot. 62: 839–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lahtinen SJ, Ahokoski H, Reinikainen JP, Gueimonde M, Nurmi J, Ouwehand AC, Salminen SJ. 2008. Degradation of 16S rRNA and attributes of viability of viable but nonculturable probiotic bacteria. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 46: 693–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fuller R. 1989. Probiotics in man and animals. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 66: 365–378 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]