Abstract

Sepsis is a clinical entity in which complex inflammatory and physiological processes are mobilized, not only across a range of cellular and molecular interactions, but also in clinically relevant physiological signals accessible at the bedside. There is a need for a mechanistic understanding that links the clinical phenomenon of physiologic variability with the underlying patterns of the biology of inflammation, and we assert that this can be facilitated through the use of dynamic mathematical and computational modeling. An iterative approach of laboratory experimentation and mathematical/computational modeling has the potential to integrate cellular biology, physiology, control theory, and systems engineering across biological scales, yielding insights into the control structures that govern mechanisms by which phenomena, detected as biological patterns, are produced. This approach can represent hypotheses in the formal language of mathematics and computation, and link behaviors that cross scales and domains, thereby offering the opportunity to better explain, diagnose, and intervene in the care of the septic patient.

Keywords: sepsis, inflammatory response, SIRS, septic shock, mathematical modeling

I. INTRODUCTION: THE SIGNIFICANCE AND PUZZLE OF SEPSIS

Sepsis is a significant may account for nearly 10% of total U.S. deaths.1–4 It can be argued that for most infections, death, despite antibiotics, occurs primarily through the final common pathway of sepsis-induced multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS). When viewed thus, sepsis is the tenth leading cause of death overall in the United States.2,5 Sepsis affects persons of all ages groups,6 and is the second leading cause of morbidity and mortality for patients admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU).1,7–10 Sepsis also substantially reduces the quality of life of many of those who survive.2,11,12 As the population ages, and the increasing preponderance of complex medical comorbidities expected in that population, the impact of sepsis would be expected to increase.1,2,6,13

Despite a large body of scientific literature concerning individual mechanisms that are involved in sepsis—ranging from disordered endothelial activation, public 14,15 organ dysfunction due to epithelial cell fail-health concern that ure,16,17 to dysregulated inflammation and the associated complement and coagulation networks18,19—the primary challenge in the management of sepsis is the effective integration and characterization of multiple abnormal configurations of all these factors, and the identification of which patients set of disorders. This challenge is manifest not only among individuals (i.e., patient heterogeneity), but also during the course of disease within a single patient (temporal heterogeneity). The heterogeneous nature of the sepsis patient population has made it difficult to parse that population into sufficiently precise, molecularly defined pathophysiologic subgroups. The field has progressed from a recognition of the basic clinical features of sepsis in antiquity20 through the germ theory (in which pathogens were the sole causes),21–23 to the development of various sets of fairly rigid diagnostic and evolving guidelines and scoring systems developed in part in response to the inability to curb sepsis solely through therapy aimed at the pathogen.22,24–26 However, recent advances in the analysis and modeling of high-dimensional, dynamic data (physiologic, genomic, and proteomic) on acutely ill patients (discussed below) suggest that the field is heading toward multidimensional characterization of the state of individual patients, rather than rigid diagnoses.27–29

II. PATTERNS OF PHYSIOLOGY AND INFLAMMATION IN SEPSIS

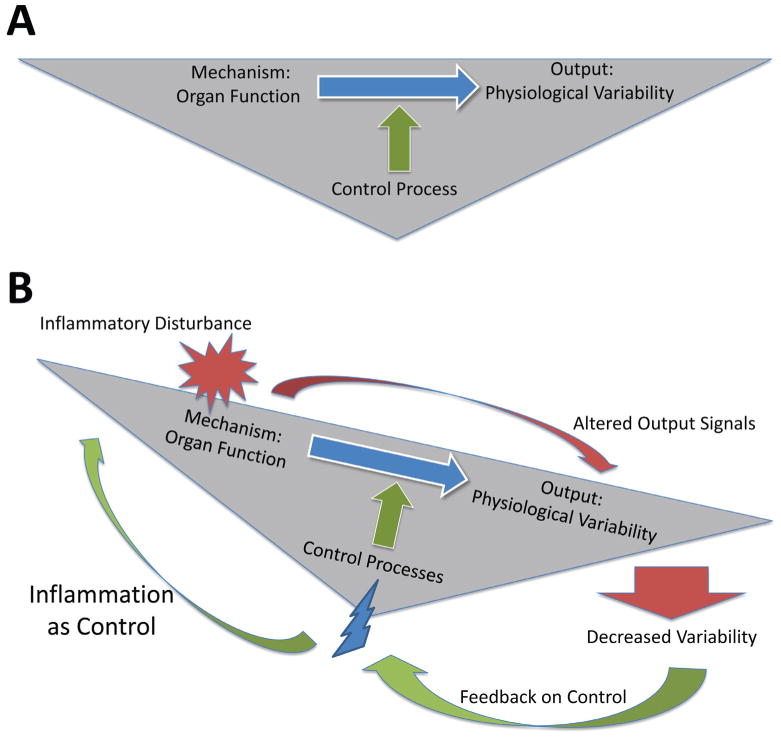

Two, heretofore parallel, approaches have evolved over time in an attempt to address sepsis diagnosis and therapy from a systems perspective, both of which utilize patterns of information. One area of active research involves the analysis of physiological signals retrievable from bedside monitoring devices, dealing with the processing and interpretation of complex physiological signals. Twenty years of research in this area30 have led to the identification of metrics representing loss of complexity of physiologic variability in heart rate and breathing patterns; these metrics are finally being used for the diagnosis of sepsis in a limited fashion.31,32 These descriptive methods have been used in an attempt to elucidate more precise and potentially predictive metrics associated with clinical manifestations of sepsis/MODS; the hope is that these metrics will also provide some mechanistic insight into the control systems responsible for their output. For instance, organ dysfunction in sepsis has been viewed as a decoupling of the oscillatory systems manifest in intact organ-to-organ feedback.33 Both experimental and clinical studies have suggested that one measure of this disrupted oscillatory coupling is reduced variability (or increased regularity) in various physiologic signals, chief among them being heart rate (Fig. 1).34–36 Time-domain analysis of heart rate variability (HRV) has subsequently evolved as a potentially noninvasive diagnostic modality for sepsis.37 Using sophisticated physiological signal-processing techniques, various studies have reported that a decrease in HRV indices may be potentially diagnostic of higher morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients.35,38–45 In addition to HRV, examination of other physiologic parameters from a complex systems approach has also yielded valuable insights into the physiology of sepsis.46,47 The rising interest in the diagnostic utility of metrics of HRV in the setting of trauma and sepsis43,48 was highlighted at the recent Ninth International Conference on Complexity in Acute Illness.49

FIGURE 1.

The effects of inflammation on organ function and accompanying physiologic variability occur via a neuroendocrine control architecture. (A) In the healthy state, normal organ function manifests in physiologic variability due to the actions of a neuroendocrine control architecture. (B) Inflammation affects healthy physiologic variability, and defined changes in physiologic variability are sensed via the neuroendocrine control architecture (that in turn is itself affected by inflammation). This control system in turn induces further inflammation in an attempt to restore healthy variability, but is most likely degraded in the face of persistent inflammation, creating a positive feedback loop of inflammation → dysfunction → inflammation.

However, despite the demonstrated validity and usefulness of these types of physiological signal analyses, these methods remain primarily phenomenological and diagnostic in nature—in essence, connecting biological pattern with clinical outcome through the use of statistical methods.50 The clinical management of sepsis/MODS is significantly hampered in both diagnostics and therapeutics; therefore, any cohesive attempt to deal with the challenge of sepsis needs to connect phenomenology with mechanism in order to attack both needs simultaneously. There have been some attempts to establish anatomic correlates to the control systems involved in organ-to-organ oscillatory coupling: HRV data have been used indirectly to detect variability attributed to sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the autonomic nervous system as well as other physiological processes that affect heart rate, including respiration, blood pressure, and temperature.37 However, in order to design and develop therapeutics in a rationally directed manner, a precise dynamic characterization of the cellular and molecular mechanisms responsible for generating the sepsis phenotype is required.

Toward this end, the other parallel track of complex systems analysis in the study of sepsis invovles dynamic mathematical and computational modeling at the cellular and molecular level. It is well appreciated that inflammation is both a communication mechanism for, and the primary driver of, the cascading organ dysfunction characteristic of sepsis and MODS51 (Fig. 1). Inflammation in trauma/hemorrhage and sepsis manifests in patterns evident at the genomic,50–53 proteomic,28,56,57 and metabolomic28,58 levels. The complexity of dynamic patterns in inflammation is potentially daunting, and multiple groups have approached characterizing this critical generative process through pattern-oriented analyses.59–66 Such analyses may suggest principal drivers of inflammation and MODS, and may define the interconnected networks of mediators and signaling responses that underlie the pathobiology of critical illness.

III. A TRANSLATIONAL SYSTEMS BIOLOGY APPROACH TO CRITICAL ILLNESS

Despite these advanced pattern-oriented methods, the knowledge necessary to both decipher the complexity of acute inflammation and MODS may require going beyond patterns toward mechanism, using the tools of mathematical modeling.29,67–75 The pathogenesis of sepsis is dynamic and involves tissue-level cellular activation resulting in the release of inflammatory mediators such as cytokines; the activation of neutrophils, monocytes, and microvascular endothelial cells; triggered involvement of neuroendocrine mechanisms; and activation of the complement, coagulation, and fibrinolytic systems76,77(Fig. 1). The innate immune/acute inflammatory response recognizes the presence of invading pathogens, acts toward initial containment, recruits additional cells to eliminate the pathogens, and, concurrently, involves feedback mechanisms that serve to limit and restrict the proinflammatory component such that homeostatic dynamic equilibrium can be reestablished.78 These factors function in a series of interlinked and overlapping networks that function at multiple scales, suggesting that “inflammation is communication.”79 As in any situation that involves communication, the content, tone, and context are of critical importance. For instance, an appropriately robust inflammatory response is necessary to survive trauma/hemorrhage, both in the very short and long terms,66,80 a finding that contradicts the driving dogma of trauma/sepsis from the 1980s and 1990s.81,82

It is important to note that organs obtained from sepsis patients postmortem do not exhibit histological damage;83 however, these organs are nonetheless dysfunctional through various functional defects identified at the cellular/molecular level in both epithelial84 and endothelial cells.14,15 This dysfunction may evolve from and help maintain disordered positive feedback loops, in which inflammation induced by pathogen-derived signals leads to the release from epithelial and endothelial cells of molecular messengers of tissue damage, namely, damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) molecules. These alarm/danger signals recruit and stimulate inflammatory cells to produce more inflammatory mediators, leading to a further release of DAMPs, resulting in a self-maintaining inflammatory cycle, even after the pathogen has been cleared. The body is equipped to suppress inflammation and promote the healing of cells, tissues, and organs both through the production of anti-inflammatory mediators as well as through an inherent suppression of proinflammatory signaling (referred to as tolerance or desensitization). In sepsis, these anti-inflammatory influences are either insufficient to suppress self-maintaining inflammation, or are overproduced and lead to an immunosuppressed state.78,85–87 Given the complexity of these feedback relationships, it not surprising that, despite promising results at the basic science and preclinical level, large-scale trials of therapies targeted at inhibiting specific inflammatory mediators have generally failed to improve survival.88

Inflammatory pathways and the organ-level physiology to which they are coupled exhibit nonlinear behavior, significantly limiting the intuitive extrapolation of mechanistic knowledge derived from basic science to clinically relevant effects at the level of the whole patient.89–93 Reductionism, the primary approach in biomedical research, has been successful when applied to systems whose behavior can be reduced to a “linear” (i.e., single direct relationship) representation such that the results of various independent experiments can be aggregated additively to obtain and predict the behavior of the system as a whole.89 However, systems that have multiple positive and negative feedback loops, and therefore display nonlinear behavior such as the acute inflammatory response, require more sophisticated mathematical representation for their characterization. It is now recognized that such an approach is necessary to understand complex biologic processes.89,91,94–98

Systems biology provides some methods and approaches that move in the appropriate direction.95,99 In silico (i.e., computer-based) research consisting of the use of dynamic mathematical and computational models has been suggested as a necessary step in untangling complex biological processes such as the acute inflammatory response by both the NIH in its Roadmap Initiative100 and the FDA in its “Critical Path” document.99 Dynamic mathematical and computational models characterize the evolution of variables (corresponding to observable properties in the real world) over time, and thus account for the temporal dimension in the description of a biological phenomenon/system. Therefore, the purpose of such computational models is predictive description—to provide entailment and insight into the future state of the system given knowledge of the current state of the system. This property suggests that dynamic mathematical and computational models can be considered testable hypotheses. When such a model predicts measurable behavior that matches the corresponding metrics experimentally observed in the system under study, one can reasonably infer that the model has captured potentially useful interrelations.89 Conversely, when model and experiment disagree, the assumptions/hypotheses represented in the model must be reassessed (it should be noted that this process is not limited to mathematical models).

Transparency in model construction is critical, insomuch that the assumptions underlying a particular model must be able to be examined in detail so that the iterative process of model refinement (essentially a proxy for the scientific method) can be executed.101,102 Furthermore, the formal process of creating and executing in silico models can provide useful frameworks for integrating hypotheses and dealing with the uncertainties associated with the calibration of experimental data, given behavioral nonlinearities, high-dimensional parameter spaces, and sparse sample points.103

Mechanistic in silico models of acute inflammation have been applied successfully to sepsis, trauma, and wound healing, leading to the concept of translational systems biology of inflammation.29,67,70–75,104,105 In terms of theory, simple models of acute inflammation have suggested that morbidity and mortality in sepsis may arise from diverse insult- and patient-specific circumstances, 106 and have given basic insight into properties of molecular control structures and sufficient levels of representation.107,108 Dynamic mathematical and computational models have been used to characterize inflammatory signal-transduction cascades, and these studies may help drive mechanism-based drug discovery.109–111 Other computational models were used to yield insights into the acute inflammatory response in diverse shock states,112–117 as well as the responses to anthrax,118 necrotizing enterocolitis,119 and toxic-shock syndrome.120 In silico modeling has helped define and predict the acute inflammatory responses seen in both experimental animals112,115,121–123 and humans.124 Initial translational successes of dynamic mathematical and computational models involved the ability to reproduce (and suggest improvements to) clinical trials in sepsis,98,125 and these successes have been extended to the design of prospective clinical trials.67,71,72,74,75 An in silico clinical trial environment, consisting of a multiscale, equation-based mechanistic simulation that encompasses dynamic interactions among multiple tissues, immune cells, and inflammatory mediators, has been augmented with a “virtual clinician” in order to better reproduce the clinical environment of critical care.61,71,72,74,75

IV. SEPSIS: FROM PATTERN TO MECHANISM VIA TRANSLATIONAL SYSTEMS BIOLOGY

Despite all of the aforementioned research into, and emerging translational applications of, complex systems methods, there has been little success in mechanistically connecting inflammation and physiologic variability. Our long-term goal is a systems understanding of sepsis that will allow us to unify the pattern-based, diagnostically relevant use of physiological waveforms with the increasingly detailed, mechanistic understanding of acute inflammation in order to improve therapy for sepsis. At present, however, patterns of physiologic signals and inflammatory mediators are, at best, statistically associated with changes in organ function and overall health status.126 We suggest that these processes need to be viewed from a dynamic, mechanistic standpoint, and that the missing ingredient in many current research endeavors is the ability to connect multidimensional data with underlying biological and physiologic mechanisms. In short, we are not satisfied with associations and correlations between patterns of signals and disease state; we seek to understand the generative processes by which those signals arise. We suggest that translational systems biology is the path to representing this critical connectivity, an approach that involves mechanistic mathematical modeling with a clinically translational focus.67,71–75 We view both inflammation and physiologic variability from a “Goldilocks” perspective, i.e., too little or too much of either is a hallmark of disease, and our engineering focus104 has led us to suggest that we need to understand the control architecture involved in balancing inflammation and physiologic demands. We hypothesize that breakdowns in the control architecture and connectivity lead to the myriad derangements associated with sepsis, and that these failure modes can be described and quantified in order to separate critical signals from “red herring” signals that arise from the inherent system architecture (Fig. 1). We suggest that future sepsis research would be greatly enhanced by developing approaches to bridge the gap between cellular-molecular mechanism and clinically relevant physiological phenomenon, hopefully leading to a solid mechanistic foundation to diagnostically relevant changes in physiologic waveforms and patterns of inflammatory mediators.

V. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PROSPECTS

There can be little doubt about the potential future societal impact of sepsis.1,2,6,13 As with virtually all aspects of sepsis, the difficulties clinicians face in the future are due, ironically, at least to some degree to the prior successes of the very same clinical community: the consequences of their successes are that people are now older and generally sicker when they reach the ICU. The advances in mechanistic understanding associated with the pathophysiology of sepsis are also impressive, but these advances, too, have often only served to complicate matters: we now recognize that “sepsis” is not one clinical entity, but rather a broad and heterogeneous spectrum of acute systemic inflammation. Any rational approach to the challenge of sepsis and related disorders requires the ability to parse out the clinical population into more mechanistically defined subgroups; it is only then that effective interventions might be designed and implemented with a nonrandom chance of success (in contrast to the past 25 years of attempts at therapeutic intervention in sepsis).

Many research communities have recognized the importance of mathematical and computational integration of knowledge in order to advance their science. Drawing on the experience in physics,127 ecology,128 material science,129 geochemistry,130 and many other scientific fields, we do not suggest that mathematical modeling is a substitute for experiments performed in the real world. However, computational modeling of critical illness and intervention is a means of leveraging the expertise in knowledge integration and engineering present across scientific disciplines. Specifically related to critical illness and sepsis, computational modeling serves at least two purposes. First, any model that predicts behaviors closely corresponding to experiment and/or clinical observation reassures us that the model has, in fact, captured the relevant components and their interactions.131 Second, and perhaps most important, discordance between the model’s behavior and anticipated or actual outcomes illuminates those areas where further experiments should focus.131 Ultimately, translational systems biology should continue to inspire both hope131 and skepticism132 on the path to mechanism from biological and physiological patterns.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health grants R01GM67240, P50GM53789, R33HL089082, R01HL080926, R01AI080799, R01HL76157, R01DC008290, and UO1 DK072146; National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research grant H133E070024; a Shared University Research Award from IBM, Inc.; and grants from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the Pittsburgh Life Sciences Greenhouse, and the Pittsburgh Tissue Engineering Initiative/Department of Defense.

ABBREVIATIONS

- DAMP

damage-associated molecular pattern

- ICU

intensive care unit

- MODS

multiple organ dysfunction syndrome

References

- 1.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7):1303–10. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(16):1546–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vincent JL, Sakr Y, Sprung CL, Ranieri VM, Reinhart K, Gerlach H, Moreno R, Carlet J, Le Gall JR, Payen D. Sepsis in European intensive care units: results of the SOAP study. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(2):344–53. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000194725.48928.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heron M, Hoyert DL, Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: final data for 2006. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2009;57(14):1–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoyert DL, Arias E, Smith BL, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD. Deaths: final data for 1999. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2001;49(8):1–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weycker D, Akhras KS, Edelsberg J, Angus DC, Oster G. Long-term mortality and medical care charges in patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(9):2316–23. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000085178.80226.0B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wheeler AP, Bernard GR. Treating patients with severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(3):207–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901213400307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angus DC, Wax RS. Epidemiology of sepsis: an update. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7 Suppl):S109–16. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107001-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sands KE, Bates DW, Lanken PN, Graman PS, Hibberd PL, Kahn KL, Parsonnet J, Panzer R, Orav EJ, Snydman DR, Black E, Schwartz JS, Moore R, Johnson BL, Jr, Platt BL. Epidemiology of sepsis syndrome in 8 academic medical centers. JAMA. 1997;278(3):234–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parrillo JE, Parker MM, Natanson C, Suffredini AF, Danner RL, Cunnion RE, Ognibene FP. Septic shock in humans. Advances in the understanding of pathogenesis, cardiovascular dysfunction, and therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(3):227–42. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-3-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heyland DK, Hopman W, Coo H, Tranmer J, McColl MA. Long-term health-related quality of life in survivors of sepsis. Short Form 36: a valid and reliable measure of health-related quality of life. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(11):3599–605. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200011000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perl TM, Dvorak L, Hwang T, Wenzel RP. Long-term survival and function after suspected gram-negative sepsis. JAMA. 1995;274(4):338–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Increase in National Hospital Discharge Survey rates for septicemia—United States, 1979–1987. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1990;19;39(2):31–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aird WC. The role of the endothelium in severe sepsis and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Blood. 2003;101(10):3765–77. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ait-Oufella H, Maury E, Lehoux S, Guidet B, Offenstadt G. The endothelium: physiological functions and role in microcirculatory failure during severe sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(8):1286–98. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1893-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Protti A, Singer M. Bench-to-bedside review: potential strategies to protect or reverse mitochondrial dysfunction in sepsis-induced organ failure. Crit Care. 2006;10(5):228–34. doi: 10.1186/cc5014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balestra GM, Legrand M, Ince C. Microcirculation and mitochondria in sepsis: getting out of breath. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009;22(2):184–90. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e328328d31a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rittirsch D, Flierl MA, Ward PA. Harmful molecular mechanisms in sepsis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(10):776–87. doi: 10.1038/nri2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levi M, van der Poll T. Inflammation and coagulation. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(2 Suppl):S26–S34. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c98d21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geroulanos S, Douka ET. Historical perspective of the word “sepsis”. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(12):2077. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0392-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ewald PW. Evolution of virulence. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2004;18(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5520(03)00099-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vincent JL. Clinical sepsis and septic shock—definition, diagnosis and management principles. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393(6):817–24. doi: 10.1007/s00423-008-0343-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schottmueller H. Wesen und Behandlung der Sepsis. Inn Med. 2009;31:257–80. (1914) [Google Scholar]

- 24.American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference: definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1992;20(6):864–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, Cohen J, Opal SM, Vincent JL, Ramsay G. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4):1250–6. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000050454.01978.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, Schein RM, Sibbald WJ. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992;101(6):1644–55. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ventetuolo CE, Levy MM. Biomarkers: diagnosis and risk assessment in sepsis. Clin Chest Med. 2008;29(4):591–603. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Claus RA, Otto GP, Deigner HP, Bauer M. Approaching clinical reality: markers for monitoring systemic inflammation and sepsis. Curr Mol Med. 2010;10(2):227–35. doi: 10.2174/156652410790963358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Namas R, Zamora R, Namas R, An G, Doyle J, Dick TE, Jacono FJ, Androulakis IP, Chang S, Billiar TR, Kellum JA, Angus DC, Vodovotz Y. Sepsis: Something old, something new, and a systems view. J Crit Care. 2012 Jun;27(3):314.e1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.www.physionet.org 2012.

- 31.Gang Y, Malik M. Heart rate variability in critical care medicine. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2002;8(5):371–5. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200210000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moorman JR, Lake DE, Griffin MP. Heart rate characteristics monitoring for neonatal sepsis. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2006;53(1):126–32. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2005.859810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Godin PJ, Buchman TG. Uncoupling of biological oscillators: a complementary hypothesis concerning the pathogenesis of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Crit Care Med. 1996;24(7):1107–16. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199607000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Annane D, Trabold F, Sharshar T, Jarrin I, Blanc AS, Raphael JC, Gajdos P. Inappropriate sympathetic activation at onset of septic shock: a spectral analysis approach. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(2):458–65. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.2.9810073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Korach M, Sharshar T, Jarrin I, Fouillot JP, Raphael JC, Gajdos P, Annane D. Cardiac variability in critically ill adults: influence of sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7):1380–5. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piepoli M, Garrard CS, Kontoyannis DA, Bernardi L. Autonomic control of the heart and peripheral vessels in human septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 1995;21(2):112–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01726532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fairchild KD, Saucerman JJ, Raynor LL, Sivak JA, Xiao Y, Lake DE, Moorman JR. Endotoxin depresses heart rate variability in mice: cytokine and steroid effects. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297(4):R1019–27. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00132.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heart rate variability. Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Eur Heart J. 1996;17(3):354–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kleiger RE, Stein PK, Bigger JT., Jr Heart rate variability: measurement and clinical utility. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2005;10(1):88–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2005.10101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pomeranz B, Macaulay RJ, Caudill MA, Kutz I, Adam D, Gordon D, Kilborn KM, Barger AC, Shannon DC, Cohen RJ, Benson H. Assessment of autonomic function in humans by heart rate spectral analysis. Am J Physiol. 1985;248(1 Pt 2):H151–3. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.248.1.H151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Godin PJ, Fleisher LA, Eidsath A, Vandivier RW, Preas HL, Banks SM, Buchman TG, Suffredini AF. Experimental human endotoxemia increases cardiac regularity: results from a prospective, randomized, crossover trial. Crit Care Med. 1996;24(7):1117–24. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199607000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barnaby D, Ferrick K, Kaplan DT, Shah S, Bijur P, Gallagher EJ. Heart rate variability in emergency department patients with sepsis. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(7):661–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb02143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen WL, Kuo CD. Characteristics of heart rate variability can predict impending septic shock in emergency department patients with sepsis. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(5):392–7. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pontet J, Contreras P, Curbelo A, Medina J, Noveri S, Bentancourt S, Migliaro ER. Heart rate variability as early marker of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome in septic patients. J Crit Care. 2003;18(3):156–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahmad S, Ramsay T, Huebsch L, Flanagan S, McDiarmid S, Batkin I, McIntyre L, Sundaresan SR, Maziak DE, Shamji FM, Hebert P, Fergusson D, Tinmouth A, Seely AJ. Continuous multi-parameter heart rate variability analysis heralds onset of sepsis in adults. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(8):e6642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Magder S. Bench-to-bedside review: ventilatory abnormalities in sepsis. Crit Care. 2009;13(1):202–13. doi: 10.1186/cc7116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Preas HL, Jubran A, Vandivier RW, Reda D, Godin PJ, Banks SM, Tobin MJ, Suffredini AF. Effect of endotoxin on ventilation and breath variability: role of cyclooxygenase pathway. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(4):620–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.2003031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cancio LC, Batchinsky AI, Salinas J, Kuusela T, Convertino VA, Wade CE, Holcomb JB. Heart-rate complexity for prediction of prehospital lifesaving interventions in trauma patients. J Trauma. 2008;65(4):813–9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181848241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.www.iccai.org/sci_info_2010.php.

- 50.An G. Phenomenological issues related to the measurement, mechanisms and manipulation of complex biological systems. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(1):245–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000191131.95141.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hodgin KE, Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14(19):1833–9. doi: 10.2174/138161208784980590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chung TP, Laramie JM, Province M, Cobb JP. Functional genomics of critical illness and injury. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(1 Suppl):S51–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cobb JP, O’Keefe GE. Injury research in the genomic era. Lancet. 2004;363(9426):2076–83. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16460-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wurfel MM. Microarray-based analysis of ventilator-induced lung injury. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4(1):77–84. doi: 10.1513/pats.200608-149JG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Winkelman C. Inflammation and genomics in the critical care unit. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2008;20(2):213–21. vi. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nguyen A, Yaffe MB. Proteomics and systems biology approaches to signal transduction in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(1 Suppl):S1–6. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200301001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bauer M, Reinhart K. Molecular diagnostics of sepsis--where are we today? Int J Med Microbiol. 2010;300(6):411–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Serkova NJ, Standiford TJ, Stringer KA. The Emerging Field of Quantitative Blood Metabolomics for Biomarker Discovery in Critical Illnesses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011 Sep 15;184(6):647–55. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0474CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Calvano SE, Xiao W, Richards DR, Felciano RM, Baker HV, Cho RJ, Chen RO, Brownstein BH, Cobb JP, Tschoeke SK, Miller-Graziano C, Moldawer LL, Mindrinos MN, Davis RW, Tompkins RG, Lowry SF Large Scale Collab Res Program. A network-based analysis of systemic inflammation in humans. Nature. 2005;437:1032–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu T, Qian WJ, Gritsenko MA, Xiao W, Moldawer LL, Kaushal A, Monroe ME, Varnum SM, Moore RJ, Purvine SO, Maier RV, Davis RW, Tompkins RG, Camp DG, Smith RD. High dynamic range characterization of the trauma patient plasma proteome. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5(10):1899–913. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600068-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McDunn JE, Husain KD, Polpitiya AD, Burykin A, Ruan J, Li Q, Schierding W, Lin N, Dixon D, Zhang W, Coopersmith CM, Dunne WM, Colonna M, Ghosh BK, Cobb JP. Plasticity of the systemic inflammatory response to acute infection during critical illness: development of the riboleukogram. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(2):e1564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Warren HS, Elson CM, Hayden DL, Schoenfeld DA, Cobb JP, Maier RV, Moldawer LL, Moore EE, Harbrecht BG, Pelak K, Cuschieri J, Herndon DN, Jeschke MG, Finnerty CC, Brownstein BH, Hennessy L, Mason PH, Tompkins RG. A genomic score prognostic of outcome in trauma patients. Mol Med. 2009;15(7–8):220–7. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2009.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cobb JP, Moore EE, Hayden DL, Minei JP, Cuschieri J, Yang J, Li Q, Lin N, Brownstein BH, Hennessy L, Mason PH, Schierding WS, Dixon DJ, Tompkins RG, Warren HS, Schoenfeld DA, Maier RV. Validation of the riboleukogram to detect ventilator-associated pneumonia after severe injury. Ann Surg. 2009;250(4):531–9. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b8fbd5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Qian WJ, Petritis BO, Kaushal A, Finnerty CC, Jeschke MG, Monroe ME, Moore RJ, Schepmoes AA, Xiao W, Moldawer LL, Davis RW, Tompkins RG, Herndon DN, Camp DG, Smith RD. Plasma proteome response to severe burn injury revealed by 18O-labeled “universal” reference-based quantitative proteomics. J Proteome Res. 2010;9(9):4779–89. doi: 10.1021/pr1005026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhou B, Xu W, Herndon D, Tompkins R, Davis R, Xiao W, Wong WH, Toner M, Warren HS, Schoenfeld DA, Rahme L, McDonald-Smith GP, Hayden D, Mason P, Fagan S, Yu YM, Cobb JP, Remick DG, Mannick JA, Lederer JA, Gamelli RL, Silver GM, West MA, Shapiro MB, Smith R, Camp DG, Qian W, Storey J, Mindrinos M, Tibshirani R, Lowry S, Calvano S, Chaudry I, West MA, Cohen M, Moore EE, Johnson J, Moldawer LL, Baker HV, Efron PA, Balis UG, Billiar TR, Ochoa JB, Sperry JL, Miller-Graziano CL, De AK, Bankey PE, Finnerty CC, Jeschke MG, Minei JP, Arnoldo BD, Hunt JL, Horton J, Cobb JP, Brownstein B, Freeman B, Maier RV, Nathens AB, Cuschieri J, Gibran N, Klein M, O’keefe G. Analysis of factorial time-course microarrays with application to a clinical study of burn injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(22):9923–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002757107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mi Q, Constantine G, Ziraldo C, Solovyev A, Torres A, Namas R, Bentley T, Billiar TR, Zamora R, Puyana JC, Vodovotz Y. A dynamic view of trauma/hemorrhage-induced inflammation in mice: Principal drivers and networks. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19424. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vodovotz Y, Csete M, Bartels J, Chang S, An G. Translational systems biology of inflammation. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4:1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Foteinou PT, Yang E, Androulakis IP. Networks, biology and systems engineering: a case study in inflammation. Comput Chem Eng. 2009;33(12):2028–41. doi: 10.1016/j.compchemeng.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Foteinou PT, Calvano SE, Lowry SF, Androulakis IP. Translational potential of systems-based models of inflammation. Clin Transl Sci. 2009;2(1):85–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2008.00051.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vodovotz Y, Constantine G, Rubin J, Csete M, Voit EO, An G. Mechanistic simulations of inflammation: Current state and future prospects. Math Biosci. 2009;217:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vodovotz Y, An G, Yan Q, editors. Systems biology in drug discovery and development: methods and protocols. Totowa, NJ: Springer Science & Business Media; 2009. pp. 181–201. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vodovotz Y, Constantine G, Faeder J, Mi Q, Rubin J, Sarkar J, Squires R, Okonkwo DO, Gerlach J, Zamora R, Luckhart S, Ermentrout B, An G. Translational systems approaches to the biology of inflammation and healing. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2010;32:181–95. doi: 10.3109/08923970903369867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vodovotz Y. Translational systems biology of inflammation and healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2010;18(1):3–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00566.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mi Q, Li NYK, Ziraldo C, Ghuma A, Mikheev M, Squires R, Okonkwo DO, Verdolini Abbott K, Constantine G, An G, Vodovotz Y. Translational systems biology of inflammation: Potential applications to personalized medicine. Personalized Med. 2010;7:549–59. doi: 10.2217/pme.10.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.An G, Bartels J, Vodovotz Y. In silico augmentation of the drug development pipeline: Examples from the study of acute inflammation. Drug Dev Res. 2010;72:1–14. doi: 10.1002/ddr.20415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vincent JL, Abraham E. The last 100 years of sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(3):256–63. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200510-1604OE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cinel I, Opal SM. Molecular biology of inflammation and sepsis: a primer. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(1):291–304. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819267fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vodovotz Y, Chow CC, Bartels J, Lagoa C, Prince JM, Levy RM, Kumar R, Day J, Rubin J, Constantine G, Billiar TR, Fink MP, Clermont G. In silico models of acute inflammation in animals. Shock. 2006;26(3):235–44. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000225413.13866.fo. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mi Q, Li NYK, Ziraldo C, Ghuma A, Mikheev M, Squires R, Okonkwo DO, Verdolini Abbott K, Constantine G, An G, Vodovotz Y. Translational systems biology of inflammation: Potential applications to personalized medicine. Personalized Med. 2010;7:549–59. doi: 10.2217/pme.10.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Namas R, Ghuma A, Torres A, Polanco P, Gomez H, Barclay D, Gordon L, Zenker S, Kim HK, Hermus L, Zamora R, Rosengart MR, Clermont G, Peitzman A, Billiar TR, Ochoa J, Pinsky MR, Puyana JC, Vodovotz Y. An adequately robust early TNF-α response is a hallmark of survival following trauma/hemorrhage. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(12):e8406. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rose S, Marzi I. Mediators in polytrauma--pathophysiological significance and clinical relevance. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 1998;383(3–4):199–208. doi: 10.1007/s004230050119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Smith RM, Giannoudis PV. Trauma and the immune response. J R Soc Med. 1998;91(8):417–20. doi: 10.1177/014107689809100805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE. The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(2):138–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fink MP, Delude RL. Epithelial barrier dysfunction: a unifying theme to explain the pathogenesis of multiple organ dysfunction at the cellular level. Crit Care Clin. 2005;21(2):177–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Marshall JC. Inflammation, coagulopathy, and the pathogenesis of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7 Suppl):S99–106. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107001-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jarrar D, Chaudry IH, Wang P. Organ dysfunction following hemorrhage and sepsis: mechanisms and therapeutic approaches (Review) Int J Mol Med. 1999;4(6):575–83. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.4.6.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Crouser E, Exline M, Knoell D, Wewers MD. Sepsis: links between pathogen sensing and organ damage. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14(19):1840–52. doi: 10.2174/138161208784980572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bone RC. Why sepsis trials fail. JAMA. 1996;276(7):565–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vodovotz Y, Clermont G, Chow C, An G. Mathematical models of the acute inflammatory response. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2004;10(5):383–90. doi: 10.1097/01.ccx.0000139360.30327.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Neugebauer EA, Willy C, Sauerland S. Complexity and non-linearity in shock research: reductionism or synthesis? Shock. 2001;16(4):252–8. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200116040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tjardes T, Neugebauer E. Sepsis research in the next millennium: concentrate on the software rather than the hardware. Shock. 2002;17(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200201000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Buchman TG, Cobb JP, Lapedes AS, Kepler TB. Complex systems analysis: a tool for shock research. Shock. 2001;16(4):248–51. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200116040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Seely AJ, Christou NV. Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome: exploring the paradigm of complex nonlinear systems. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(7):2193–200. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200007000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.An G. Agent-based computer simulation and sirs: building a bridge between basic science and clinical trials. Shock. 2001;16(4):266–73. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200116040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kitano H. Systems biology: a brief overview. Science. 2002;295(5560):1662–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1069492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Vodovotz Y, Csete M, Bartels J, Chang S, An G. Translational systems biology of inflammation. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4(4):e1000014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cohen MJ, Grossman AD, Morabito D, Knudson MM, Butte AJ, Manley GT. Identification of complex metabolic states in critically injured patients using bioinformatic cluster analysis. Crit Care. 2010;14(1):R10–20. doi: 10.1186/cc8864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.An G. In-silico experiments of existing and hypothetical cytokine-directed clinical trials using agent based modeling. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:2050–60. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000139707.13729.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Vodovotz Y. Deciphering the complexity of acute inflammation using mathematical models. Immunol Res. 2006;36(1–3):237–45. doi: 10.1385/IR:36:1:237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.http://commonfund.nih.gov/aboutroadmap.aspx

- 101.An G. Translational systems biology using an agent-based approach for dynamic knowledge representation: An evolutionary paradigm for biomedical research. Wound Rep Reg. 2010;18:8–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.An G. Closing the scientific loop: Bridging correlation and causality in the petaflop age. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:41ps34. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Vodovotz Y, Clermont G, Hunt CA, Lefering R, Bartels J, Seydel R, Hotchkiss J, Ta’asan S, Neugebauer E, An G. Evidence-based modeling of critical illness: an initial consensus from the Society for Complexity in Acute Illness. J Crit Care. 2007;22(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.An G, Faeder J, Vodovotz Y. Translational systems biology: Introduction of an engineering approach to the pathophysiology of the burn patient. J Burn Care Res. 2008;29:277–85. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31816677c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.An G, Mi Q, Dutta-Moscato J, Solovyev A, Vodovotz Y. Agent-based models in translational systems biology. WIRES. 2009;1:159–71. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kumar R, Clermont G, Vodovotz Y, Chow CC. The dynamics of acute inflammation. J Theoretical Biol. 2004;230:145–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.An G, Faeder JR. Detailed qualitative dynamic knowledge representation using a BioNetGen model of TLR-4 signaling and preconditioning. Math Biosci. 2009;217:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.An G. A model of TLR4 signaling and tolerance using a qualitative, particle event-based method: Introduction of Spatially Configured Stochastic Reaction Chambers (SCSRC) Math Biosci. 2009;217:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gibbs JB. Mechanism-based target identification and drug discovery in cancer research. Science. 2000;287(5460):1969–73. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Faeder JR, Hlavacek WS, Reischl I, Blinov ML, Metzger H, Redondo A, Wofsy C, Goldstein B. Investigation of early events in Fc epsilon RI-mediated signaling using a detailed mathematical model. J Immunol. 2003;170(7):3769–81. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rivière B, Epshteyn Y, Swigon D, Vodovotz Y. A simple mathematical model of signaling resulting from the binding of lipopolysaccharide with toll-like receptor 4 demonstrates inherent preconditioning behavior. Math Biosci. 2009;217:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chow CC, Clermont G, Kumar R, Lagoa C, Tawadrous Z, Gallo D, Betten B, Bartels J, Constantine G, Fink MP, Billiar TR, Vodovotz Y. The acute inflammatory response in diverse shock states. Shock. 2005;24:74–84. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000168526.97716.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Reynolds A, Rubin J, Clermont G, Day J, Vodovotz Y, Ermentrout GB. A reduced mathematical model of the acute inflammatory response: I. Derivation of model and analysis of anti-inflammation. J Theor Biol. 2006;242:220–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Day J, Rubin J, Vodovotz Y, Chow CC, Reynolds A, Clermont G. A reduced mathematical model of the acute inflammatory response: II. Capturing scenarios of repeated endotoxin administration. J Theor Biol. 2006;242:237–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Torres A, Bentley T, Bartels J, Sarkar J, Barclay D, Namas R, Constantine G, Zamora R, Puyana JC, Vodovotz Y. Mathematical modeling of post-hemorrhage inflammation in mice: Studies using a novel, computer-controlled, closed-loop hemorrhage apparatus. Shock. 2009;32:172–8. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318193cc2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Foteinou PT, Calvano SE, Lowry SF, Androulakis IP. Modeling endotoxin-induced systemic inflammation using an indirect response approach. Math Biosci. 2009;217:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Foteinou PT, Calvano SE, Lowry SF, Androulakis IP. In silico simulation of corticosteroids effect on an NFkB-dependent physicochemical model of systemic inflammation. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(3):e4706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kumar R, Chow CC, Bartels J, Clermont G, Vodovotz Y. A mathematical simulation of the inflammatory response to anthrax infection. Shock. 2008;29:104–11. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318067da56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Arciero J, Rubin J, Upperman J, Vodovotz Y, Ermentrout GB. Using a mathematical model to analyze the role of probiotics and inflammation in necrotizing enterocolitis. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Chau TA, McCully ML, Brintnell W, An G, Kasper KJ, Vines ED, Kubes P, Haeryfar SM, McCormick JK, Cairns E, Heinrichs DE, Madrenas J. Toll-like receptor 2 ligands on the staphylococcal cell wall downregulate superantigen-induced T cell activation and prevent toxic shock syndrome. Nat Med. 2009;15(6):641–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Prince JM, Levy RM, Bartels J, Baratt A, Kane JM, III, Lagoa C, Rubin J, Day J, Wei J, Fink MP, Goyert SM, Clermont G, Billiar TR, Vodovotz Y. In silico and in vivo approach to elucidate the inflammatory complexity of CD14-deficient mice. Mol Med. 2006;12:88–96. doi: 10.2119/2006-00012.Prince. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Lagoa CE, Bartels J, Baratt A, Tseng G, Clermont G, Fink MP, Billiar TR, Vodovotz Y. The role of initial trauma in the host’s response to injury and hemorrhage: Insights from a comparison of mathematical simulations and hepatic transcriptomic analysis. Shock. 2006;26:592–600. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000232272.03602.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Daun S, Rubin J, Vodovotz Y, Roy A, Parker R, Clermont G. An ensemble of models of the acute inflammatory response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide in rats: results from parameter space reduction. J Theor Biol. 2008;253:843–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Foteinou PT, Calvano SE, Lowry SF, Androulakis IP. Multiscale model for the assessment of autonomic dysfunction in human endotoxemia. Physiol Genomics. 2010;42(1):5–19. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00184.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Clermont G, Bartels J, Kumar R, Constantine G, Vodovotz Y, Chow C. In silico design of clinical trials: a method coming of age. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(10):2061–70. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000142394.28791.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Tateishi Y, Oda S, Nakamura M, Watanabe K, Kuwaki T, Moriguchi T, Hirasawa H. Depressed heart rate variability is associated with high IL-6 blood level and decline in the blood pressure in septic patients. Shock. 2007;28(5):549–53. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e3180638d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Fokas AS, Halliwell J, Kibble T, Zegarlinski B, editors. Highlights of Mathematical Physics. Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kot M. Elements of Mathematical Ecology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Baskes MI. The status role of modeling and simulation in materials science and engineering. Curr Opin Solid State Mater Sci. 1999;4(3):273–7. [Google Scholar]

- 130.van der Lee J, De Windt L. Present state and future directions of modeling of geochemistry in hydrogeological systems. J Contam Hydrol. 2001;47(2–4):265–82. doi: 10.1016/s0169-7722(00)00155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Buchman TG. In vivo, in vitro, in silico. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(10):2159–60. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000142900.95726.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Marshall JC. Through a glass darkly: the brave new world of in silico modeling. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(10):2157–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000142935.34916.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]