Abstract

qnr genes were discovered on plasmids by their ability to reduce quinolone susceptibility, but homologs can be found in the genomes of at least 92 Gram-negative, Gram-positive, and strictly anaerobic bacterial species. The related pentapeptide repeat protein-encoding mfpA gene is present in the genome of at least 19 species of Mycobacterium and 10 other Actinobacteria species. The native function of these genes is not yet known.

TEXT

The qnrA gene was discovered on a plasmid (1), and in 2002, when its sequence was established and homologs were first searched for in GenBank, few related chromosomal genes were evident (2). One was the mfp gene which had been found in the genome of mycobacteria and shown to influence fluoroquinolone susceptibility (3). Soon, however, many more chromosomal homologs were discovered in a variety of organisms. Table 1 summarizes studies in which qnr and mfpA genes from different organisms were proven to affect quinolone susceptibility, usually by providing resistance when cloned on a plasmid in Escherichia coli, but also by demonstration of increased susceptibility after inactivating the gene in its host organism.

Table 1.

Organisms with chromosomally determined pentapeptide repeat protein genes shown to reduce quinolone susceptibility

| Bacterial isolate | Demonstration of function | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Aeromonas hydrophila | Cloned and expressed in E. coli | 4 |

| Aliivibrio salmonicida | Cloned and expressed in E. coli | 5 |

| Bacillus cereus | Cloned and expressed in E. coli | 6 |

| Citrobacter freundii | Cloned and expressed in E. coli, I-CeuI localization | 7, 8 |

| Citrobacter werkmanii | Cloned and expressed in E. coli, I-CeuI localization | 7–9 |

| Clostridium difficile | Cloned and expressed in E. coli | 6 |

| Clostridium perfringens | Cloned and expressed in E. coli | 6 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | Cloned and expressed in E. faecalis and E. coli, chromosomal gene inactivated | 6, 10, 11 |

| Enterococcus faecium | Cloned and expressed in E. coli | 6 |

| Listeria monocytogenes | Cloned and expressed in E. coli | 6 |

| Mycobacterium smegmatis | Cloned and expressed in M. smegmatis, chromosomal gene inactivated | 3 |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Cloned and expressed in E. coli | 12, 13 |

| Photobacterium profundum | Cloned and expressed in E. coli | 14 |

| Serratia marcescens | Cloned and expressed in E. coli | 15 |

| Shewanella algae | Cloned and expressed in E. coli, I-CeuI localization | 14, 16 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Cloned and expressed in E. coli and S. maltophilia, chromosomal gene inactivated | 17–21 |

| Vibrio cholerae | Transferred and expressed in E. coli as a component of an integrating conjugative element | 22, 23 |

| Vibrio parahaemolyticus | Cloned and expressed in E. coli | 14, 24 |

| Vibrio splendidus | Cloned and expressed in E. coli | 25 |

| Vibrio vulnificus | Cloned and expressed in E. coli | 14 |

The discovery of the qnrA gene was soon followed by discovery of plasmid-mediated genes qnrS (26), qnrB (27), qnrC (28), and qnrD (29). The qnrVC gene from Vibrio cholerae can also be located in a plasmid (30) or in transmissible form as part of an integrating conjugative element (23). These qnr genes generally differ in sequence by 30% or more from qnrA and each other.

Qnr and MfpA are pentapeptide repeat proteins composed of tandemly repeated units of five amino acids with a consensus sequence of [S,T,A,V][D,N][L,F][S,T,R][G] (31). They dimerize and form a rod-like right-handed quadrilateral β-helix with a size, shape, and negative charge that mimics the β form of DNA (12). The two Qnr proteins of known 3-dimensional structure from Gram-negative organisms (AhQnr from Aeromonas hydrophila and plasmid-mediated QnrB1) have two loops, a smaller loop of 8 and a larger of 12 amino acids, that are essential for protective activity (4, 32). MtMfpA from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and EfsQnr from Enterococcus faecalis lack loops, but EfsQnr differs from MtMfpA at its N terminus, where it has an additional β-helical rung, a capping peptide, and a 25-amino-acid flexible extension (11, 12). In a cell-free system, MtMfpA inhibits DNA gyrase whereas the other proteins protect gyrase from quinolone inhibition and inhibit only at high concentrations (12, 13, 27).

In 2008, Sánchez et al. (17) reported a search of GenBank for homologs to QnrA, QnrB, or QnrS using a cutoff of 45% identity and found qnr genes in 22 of 960 genomes examined. In the ensuing years, many more bacterial genomes have been sequenced. An important consideration in a search for qnr homologs is where to set the breakpoint for identity. MtMfpA and the three Qnr proteins of known structure share surprisingly little homology. AhQnr and QnrB1 have 41.7% identity, but the rest have 20.3% or less, with EfsQnr and QnrB1 having only 13.8%, testimony to their interaction with topoisomerases as proteins with shape and charge but limited localized amino acid specificity.

The aim of this study was to determine the distribution of Qnr-like proteins among sequenced bacterial genomes. We searched GenBank in August and December 2012 using the amino acid sequence of each of the proteins listed in Table 1 with PHI-BLAST (33) and a cutoff value of 40% identity. Forty percent was chosen as a natural breakpoint in the distribution of organisms related to the 6 plasmid-mediated Qnrs, where few if any organisms have 30% to 40% homology and a miscellany of uncommonly encountered Gram-negative and Gram-positive organisms match at ≤30% identity. Where multiple related genes were present in organisms from a particular species, only the one with highest homology was retained. The designation “sp.” was allowed once for each genus (e.g., one Vibrio sp.).

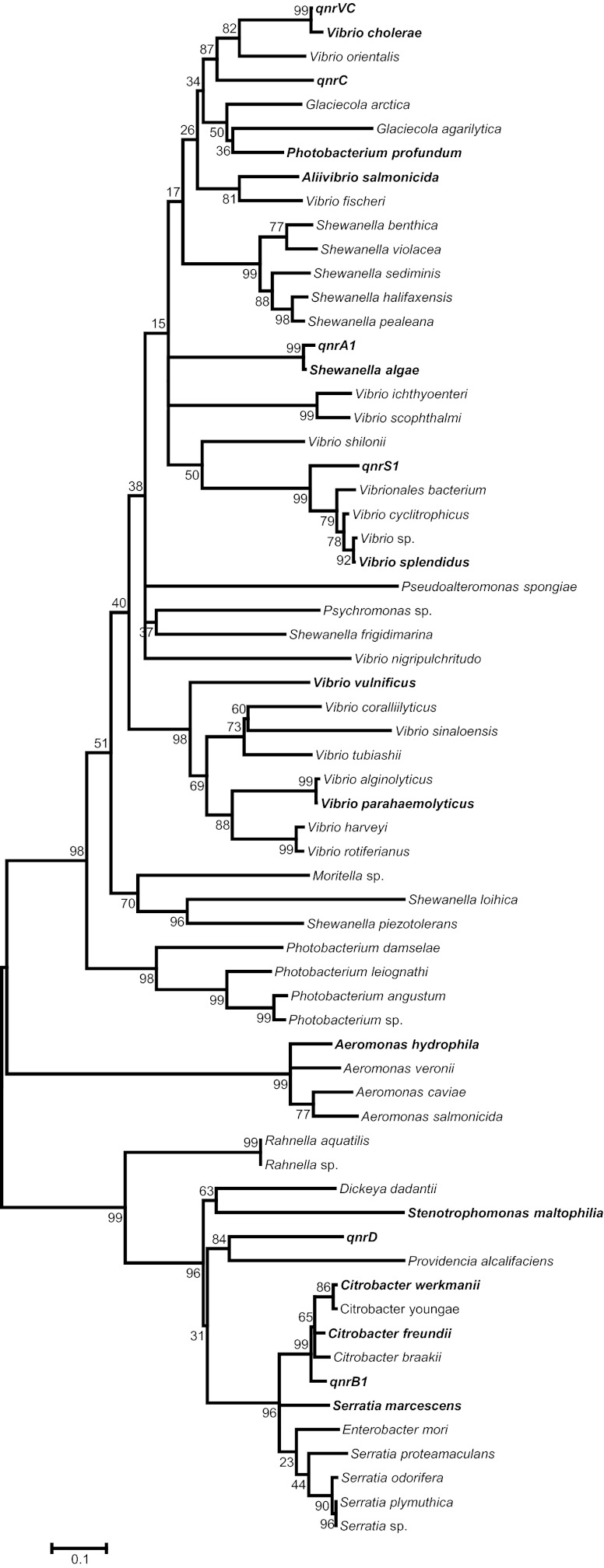

Searching with the Gram-negative organism in Table 1 generated a list of 58 organisms. All are gammaproteobacteria. In an alignment of their sequences, 28 of the ∼218 amino acids were invariant, including 18 positioned in the repetitive pentapeptide structure to play a critical role in maintaining its integrity (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). There were no gaps in the alignment, implying that all the proteins had similar structures with two loops per monomer (34). A phylogenetic tree representing the relationships among them is shown in Fig. 1. Aquatic bacteria predominated, with 18 species of Vibrio, 9 of Shewanella, 5 of Photobacterium, 4 of Aeromonas, and 2 of Glaciecola. The only members of the Enterobacteriaceae family were 4 species of Citrobacter, 5 of Serratia, 2 of Rhanella, and single species of Dickeya, Enterobacter, and Providencia. Neisseria spp. and nonfermenters such as Acinetobacter, Bordetella, Burkholderia, Legionella, Moraxella, and Pseudomonas spp. were absent, but Stenotrophomonas maltophilia was included and has more than 45 distinct chromosomal Smqnr variants (21) with a unique system of regulation (38).

Fig 1.

Phylogenetic tree of Qnr from gammaproteobacteria. The tree was constructed using the maximum-likelihood method in MEGA5 (35) based on the JTT model (36) with 1,000 bootstrap replicates. The percentages of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test are shown next to the branches (37). The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in number of substitutions per site. Plasmid-mediated qnr genes and those from Table 1 used to search for homology are shown in bold.

Transmissible Qnrs are included in Fig. 1 for comparison. As reported previously, QnrA1 is 98% identical to the chromosomally determined Qnr protein from Shewanella algae (16), QnrB1 is 93% to 95% identical to Qnr proteins from species of Citrobacter (8), and QnrS1 is 83% identical to chromosomal Qnr from Vibrio splendidus (25) and 84% identical to Qnr from a marine Vibrionales sp. (GenBank accession no. ZP_01811734.1). Close matches for QnrC and QnrD have yet to be found, but QnrC is 72% identical to Qnr proteins from Vibrio orientalis (GenBank accession no. ZP_05945497.1) and Vibrio cholerae (28), and QnrD is 64% to 66% identical to chromosomal Qnr proteins from Providencia alcalifaciens (GenBank accession no. ZP_03320716.1) and several species of Serratia (GenBank accession no. YP_004500429 and ZP_06189743).

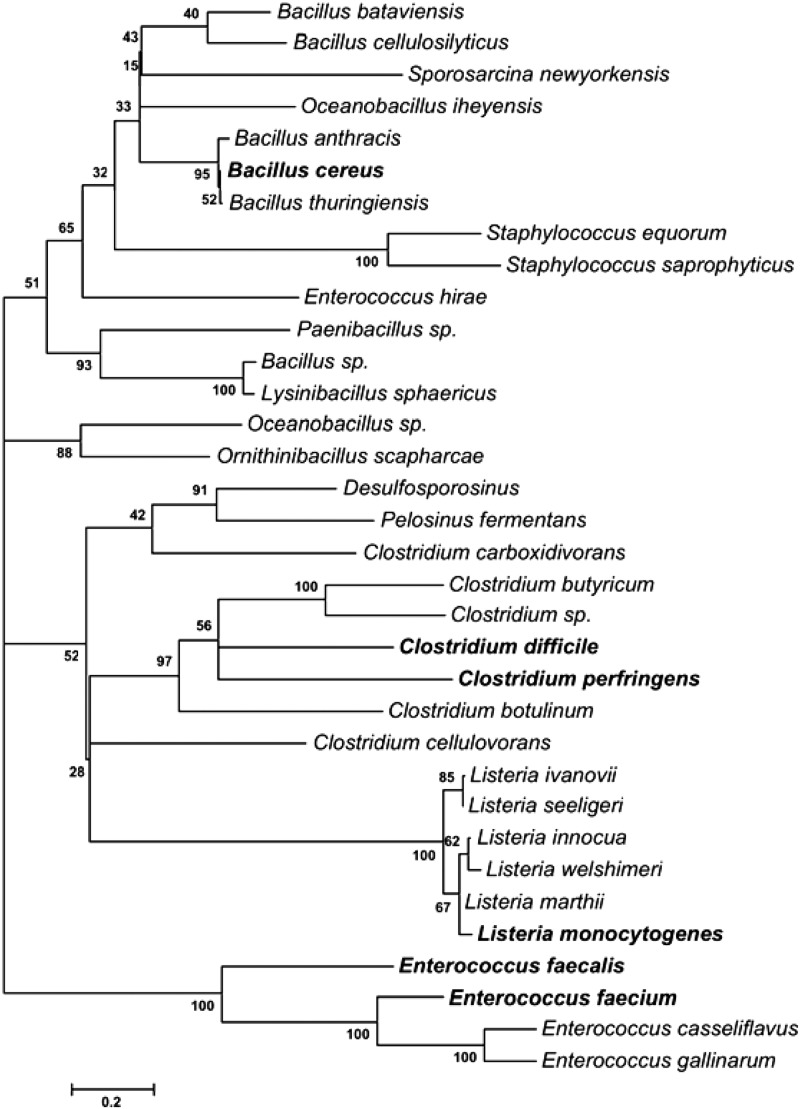

A similar search of GenBank with Qnr proteins from Gram-positive organisms from Table 1 located 34 organisms with 40% or greater identity to one or more of them. Their overall alignment has greater diversity than that of the gammaproteobacterial group, with several gaps and only 5 amino acid residues of ∼215 shared in common (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Some of the variability could represent variations in the length and composition of N-terminal extensions, which have been directly demonstrated only for EfsQnr (4). Qnr proteins from an individual Gram-positive genus, however, showed more similarity, with the greatest being 80% sequence identity among Listeria spp. All were Firmicutes, with the largest class being the Bacillales, with 20 species of Bacillus, Lysinibacillus, Oceanobacillus, Ornithinibacillus, and Paenibacillus, as well as 6 species of Listeria and 2 of coagulase-negative staphylococci. Eight varieties of Clostridium species were included, as well as 5 species of Enterococcus. Staphylococcus aureus was conspicuously absent, as were Streptococcus pneumoniae, any groupable streptococci besides members of group D, and corynebacteria. The consensus tree of this group is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig 2.

Phylogenetic tree of Qnr from Gram-positive bacteria, derived as described for Fig. 1. Qnr from the organisms shown in bold was used to initiate the search.

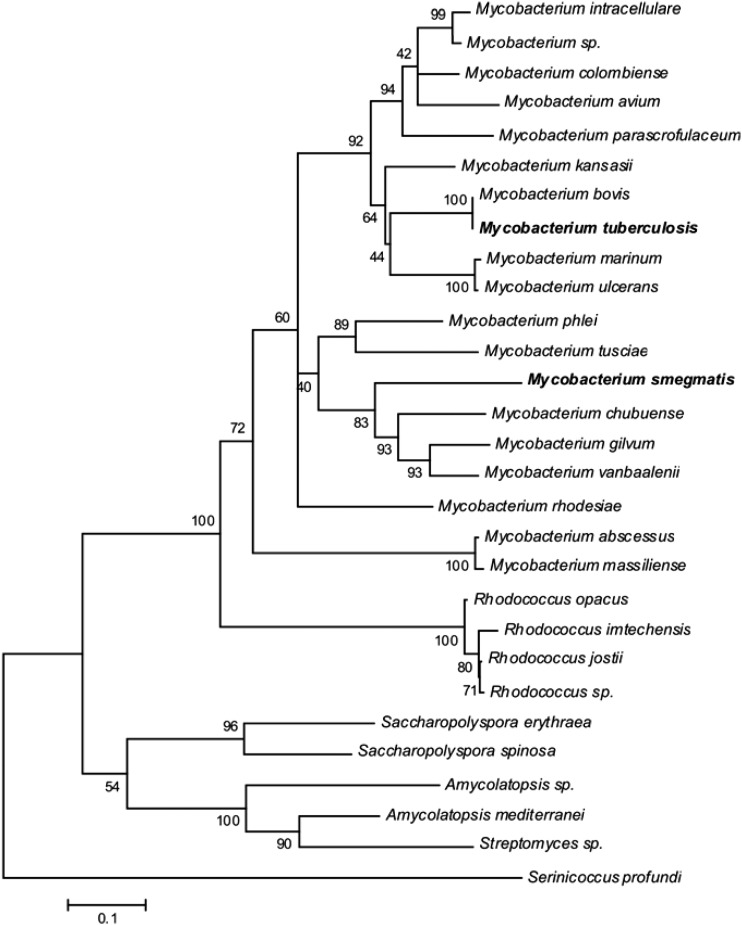

A search of GenBank with MtMfpA from M. tuberculosis found 18 other species of Mycobacterium and 10 other members of the order Actinomycetales with 40% or greater homology. There were no gaps in their alignment, and 24 of 183 amino acids in MtMfpA were conserved within the group (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). A phylogenetic tree of their relationships is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig 3.

Phylogenetic tree of matches to MfpA, derived as described for Fig. 1. MfpA from the organisms shown in bold was used to initiate the search.

There is thus little doubt that qnr genes have been present in a variety of bacterial hosts far longer than the need to protect against the recent threat of exposure to quinolone antimicrobials would require. Quinolones do occur in nature (39); for example, a variety of alkyl quinolones are produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, but such naturally occurring compounds seem inadequate to explain the ubiquity of qnr genes. Expression of qnr genes is responsive to stress: cold shock in the case of qnrA in Shewanella algae (40), activation of the SOS system for qnrB, qnrD, and the chromosomal qnr of Serratia marcescens (41–43), and fluoroquinolone exposure independent of the SOS system for qnrS and the chromosomal qnr of V. splendidus (44).

This listing of qnr genes is undoubtedly incomplete. More would be revealed with a lower cutoff for identity; for example, there are candidate Qnr proteins in many Bacteroides spp., with 30% to 35% homology to BcQnr from Bacillus cereus, and EfsQnr is 36% identical to a protein (YP_001812923) from an organism isolated from 3-million-year-old permafrost (45). Metagenomic sequence collections have not been sampled, and there are more sophisticated ways than BLAST to conduct a database homology search (46). Nonetheless, it is evident that qnr genes are widely distributed in the environment and in the bacterial world and have been recognized only recently in their role of protecting against quinolone antimicrobials. Future study of Qnr natural functions may be instructive in the modulation of topoisomerase activities and in the ways in which organisms, particularly those in aquatic environments, adapt to their surroundings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant R01 AI057576 (to D.C.H. and G.A.J.) from the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Public Health Service.

We thank C. Velasco for providing Qnr sequences from Serratia marcescens.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 January 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02080-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Martínez-Martínez L, Pascual A, Jacoby GA. 1998. Quinolone resistance from a transferable plasmid. Lancet 351:797–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tran JH, Jacoby GA. 2002. Mechanism of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:5638–5642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Montero C, Mateu G, Rodriguez R, Takiff H. 2001. Intrinsic resistance of Mycobacterium smegmatis to fluoroquinolones may be influenced by new pentapeptide protein MfpA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3387–3392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xiong X, Bromley EH, Oelschlaeger P, Woolfson DN, Spencer J. 2011. Structural insights into quinolone antibiotic resistance mediated by pentapeptide repeat proteins: conserved surface loops direct the activity of a Qnr protein from a gram-negative bacterium. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:3917–3927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sun HI, Jeong DU, Lee JH, Wu X, Park KS, Lee JJ, Jeong BC, Lee SH. 2010. A novel family (QnrAS) of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinant. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 36:578–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rodríguez-Martínez JM, Velasco C, Briales A, García I, Conejo MC, Pascual A. 2008. Qnr-like pentapeptide repeat proteins in gram-positive bacteria. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:1240–1243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sanchez-Cespedes J, Marti S, Soto SM, Alba V, Melción C, Almela M, Marco F, Vila J. 2009. Two chromosomally located qnrB variants, qnrB6 and the new qnrB16, in Citrobacter spp. isolates causing bacteraemia. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 15:1132–1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jacoby GA, Griffin CM, Hooper DC. 2011. Citrobacter spp. as a source of qnrB alleles. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4979–4984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kehrenberg C, Friederichs S, de Jong A, Schwarz S. 2008. Novel variant of the qnrB gene, qnrB12, in Citrobacter werkmanii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1206–1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arsène S, Leclercq R. 2007. Role of a qnr-like gene in the intrinsic resistance of Enterococcus faecalis to fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:3254–3258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hegde SS, Vetting MW, Mitchenall LA, Maxwell A, Blanchard JS. 2011. Structural and biochemical analysis of the pentapeptide repeat protein EfsQnr, a potent DNA gyrase inhibitor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:110–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hegde SS, Vetting MW, Roderick SL, Mitchenall LA, Maxwell A, Takiff HE, Blanchard JS. 2005. A fluoroquinolone resistance protein from Mycobacterium tuberculosis that mimics DNA. Science 308:1480–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mérens A, Matrat S, Aubry A, Lascols C, Jarlier V, Soussy CJ, Cavallo JD, Cambau E. 2009. The pentapeptide repeat proteins MfpAMt and QnrB4 exhibit opposite rffects on DNA gyrase catalytic reactions and on the ternary gyrase-DNA-quinolone complex. J. Bacteriol. 191:1587–1594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Poirel L, Liard A, Rodriguez-Martinez JM, Nordmann P. 2005. Vibrionaceae as a possible source of Qnr-like quinolone resistance determinants. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56:1118–1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Velasco C, Rodriguez-Martinez JM, Briales A, Diaz de Alba P, Calvo J, Pascual A. 2010. Smaqnr, a new chromosome-encoded quinolone resistance determinant in Serratia marcescens. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:239–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Poirel L, Rodriguez-Martinez JM, Mammeri H, Liard A, Nordmann P. 2005. Origin of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinant QnrA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3523–3525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sánchez MB, Hernández A, Rodríguez-Martínez JM, Martínez-Martínez L, Martínez JL. 2008. Predictive analysis of transmissible quinolone resistance indicates Stenotrophomonas maltophilia as a potential source of a novel family of Qnr determinants. BMC Microbiol. 8:148–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shimizu K, Kikuchi K, Sasaki T, Takahashi N, Ohtsuka M, Ono Y, Hiramatsu K. 2008. Smqnr, a new chromosome-carried quinolone resistance gene in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3823–3825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sánchez MB, Martínez JL. 2010. SmQnr contributes to intrinsic resistance to quinolones in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:580–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gordon NC, Wareham DW. 2010. Novel variants of the Smqnr family of quinolone resistance genes in clinical isolates of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:483–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang R, Sun Q, Hu YJ, Yu H, Li Y, Shen Q, Li GX, Cao JM, Yang W, Wang Q, Zhou HW, Hu YY, Chen GX. 2012. Detection of the Smqnr quinolone protection gene and its prevalence in clinical isolates of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in China. J. Med. Microbiol. 61:535–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fonseca EL, Dos Santos Freitas F, Vieira VV, Vicente AC. 2008. New qnr gene cassettes associated with superintegron repeats in Vibrio cholerae O1. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:1129–1131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim HB, Wang M, Ahmed S, Park CH, LaRocque RC, Faruque AS, Salam MA, Khan WA, Qadri F, Calderwood SB, Jacoby GA, Hooper DC. 2010. Transferable quinolone resistance in Vibrio cholerae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:799–803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Saga T, Kaku M, Onodera Y, Yamachika S, Sato K, Takase H. 2005. Vibrio parahaemolyticus chromosomal qnr homologue VPA0095: demonstration by transformation with a mutated gene of its potential to reduce quinolone susceptibility in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:2144–2145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cattoir V, Poirel L, Mazel D, Soussy CJ, Nordmann P. 2007. Vibrio splendidus as the source of plasmid-mediated QnrS-like quinolone resistance determinants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:2650–2651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hata M, Suzuki M, Matsumoto M, Takahashi M, Sato K, Ibe S, Sakae K. 2005. Cloning of a novel gene for quinolone resistance from a transferable plasmid in Shigella flexneri 2b. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:801–803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jacoby GA, Walsh KE, Mills DM, Walker VJ, Oh H, Robicsek A, Hooper DC. 2006. qnrB, another plasmid-mediated gene for quinolone resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1178–1182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang M, Guo Q, Xu X, Wang X, Ye X, Wu S, Hooper DC, Wang M. 2009. New plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance gene, qnrC, found in a clinical isolate of Proteus mirabilis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:1892–1897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cavaco LM, Hasman H, Xia S, Aarestrup FM. 2009. qnrD, a novel gene conferring transferable quinolone resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Kentucky and Bovismorbificans strains of human origin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:603–608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Xia R, Guo X, Zhang Y, Xu H. 2010. qnrVC-like gene located in a novel complex class 1 integron harboring the ISCR1 element in an Aeromonas punctata strain from an aquatic environment in Shandong Province, China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:3471–3474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vetting MW, Hegde SS, Fajardo JE, Fiser A, Roderick SL, Takiff HE, Blanchard JS. 2006. Pentapeptide repeat proteins. Biochemistry 45:1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vetting MW, Hegde SS, Wang M, Jacoby GA, Hooper DC, Blanchard JS. 2011. Structure of QnrB1, a plasmid-mediated fluoroquinolone resistance factor. J. Biol. Chem. 286:25265–25273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Park KS, Lee JH, Jeong DU, Lee JJ, Wu X, Jeong BC, Kang CM, Lee SH. 2011. Determination of pentapeptide repeat units in Qnr proteins by the structure-based alignment approach. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4475–4478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28:2731–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jones DT, Taylor WR, Thornton JM. 1992. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 8:275–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Felsenstein J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chang YC, Tsai MJ, Huang YW, Chung TC, Yang TC. 2011. SmQnrR, a DeoR-type transcriptional regulator, negatively regulates the expression of Smqnr and SmtcrA in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:1024–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Heeb S, Fletcher MP, Chhabra SR, Diggle SP, Williams P, Camara M. 2011. Quinolones: from antibiotics to autoinducers. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35:247–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kim HB, Park CH, Gavin M, Jacoby GA, Hooper DC. 2011. Cold shock induces qnrA expression in Shewanella algae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:414–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang M, Jacoby GA, Mills DM, Hooper DC. 2009. SOS regulation of qnrB expression. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:821–823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Da Re S, Garnier F, Guerin E, Campoy S, Denis F, Ploy MC. 2009. The SOS response promotes qnrB quinolone-resistance determinant expression. EMBO Rep. 10:929–933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Briales A, Rodriguez-Martinez JM, Velasco C, Machuca J, Diaz de Alba P, Blazquez J, Pascual A. 2012. Exposure to diverse antimicrobials induces the expression of qnrB1, qnrD and smaqnr genes by SOS-dependent regulation. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:2854–2859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Okumura R, Liao CH, Gavin M, Jacoby GA, Hooper DC. 2011. Quinolone induction of qnrVS1 in Vibrio splendidus and plasmid-carried qnrS1 in Escherichia coli, a mechanism independent of the SOS system. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:5942–5945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rodrigues DF, Ivanova N, He Z, Huebner M, Zhou J, Tiedje JM. 2008. Architecture of thermal adaptation in an Exiguobacterium sibiricum strain isolated from 3 million year old permafrost: a genome and transcriptome approach. BMC Genomics 9:547 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-9-547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Eddy SR. 2011. Accelerated profile HMM searches. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7:e1002195 doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]