Abstract

Given the high protein binding rates of antifungal drugs and the effect of serum proteins on Aspergillus growth, we investigated the in vitro pharmacodynamics of amphotericin B, voriconazole, and three echinocandins in the presence of human serum, assessing both inhibitory and fungicidal effects. In vitro inhibitory (IC) and fungicidal (FC) concentrations against 5 isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus flavus, and Aspergillus terreus were determined with a CLSI M38-A2-based microdilution method using the XTT methodology after 48 h of incubation at 35°C with a medium supplemented with 50% human serum. In the presence of serum, the IC and FC of amphotericin B and the IC of echinocandins were increased (1.21- to 13.44-fold), whereas voriconazole IC and FC were decreased (0.22- to 0.90-fold). The amphotericin B and voriconazole FC/IC ratios did not change significantly (0.59- to 2.33-fold) in the presence of serum, indicating that the FC increase was due to the IC increase. At echinocandin concentrations above the minimum effective concentration (MEC), fungal growth was reduced by 10 to 50% in the presence of human serum, resulting in complete inhibition of growth for some isolates. Thus, the in vitro activities of amphotericin B and echinocandins were reduced, whereas that of voriconazole was enhanced, in the presence of serum. These changes could not be predicted by the percentage of protein binding, indicating that other factors and/or secondary mechanisms may account for the observed in vitro activities of antifungal drugs against Aspergillus species in the presence of serum.

INTRODUCTION

Invasive aspergillosis is a severe infectious disease, characterized by significant mortality rates despite antifungal therapy (1). The antifungal drugs that are commonly used to treat invasive aspergillosis belong to three classes with distinct mechanisms of action: the polyene amphotericin B, which acts on the cell membrane; the azole voriconazole, which acts on ergosterol biosynthesis; and the echinocandins, which act on the cell wall (2). Among the most common species causing invasive aspergillosis are Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus flavus, and Aspergillus terreus, against which antifungal drugs demonstrated different in vivo efficacies (3–6), while most strains exhibited similar in vitro susceptibilities, particularly to amphotericin B and echinocandins (7, 8). Standardized in vitro susceptibility testing methods (CLSI or EUCAST) for Aspergillus species have been developed and proven to be very useful in testing in vitro activities of antifungal drugs (9, 10). However, a clear in vitro-in vivo clinical correlation is still lacking (11). In vitro conditions do not simulate well the in vivo microenvironment, where drugs have fluctuating concentrations and interact with the fungus in the presence of human tissue and serum proteins. Thus, antifungal activity may be altered in the presence of serum, resulting in relative differences among species and drugs within a class that were not apparent in medium without serum (12, 13).

Antifungal drugs are characterized by a significant protein binding, ranging from 58% with voriconazole and 95% with amphotericin B to >96% with echinocandins. In particular, caspofungin is 96% bound to serum proteins, micafungin is 99.8% bound, and anidulafungin is >99% bound (14). It is generally accepted that only the unbound fraction of drug is pharmacologically active (15), although several studies have demonstrated that MIC increases for antifungals do not parallel the percentage of protein binding (16, 17) and greater pharmacodynamic effects can be observed in the presence of human serum (18). Furthermore, serum may alter the in vitro activities of antifungal drugs, since serum proteins enhance Aspergillus growth and stimulate enzyme production (19, 20). Although the effect of serum on inhibitory activities of antifungal drugs against Aspergillus spp. has been sparsely studied previously (17), the effect on fungicidal activities of antifungal drugs is largely unknown. Thus, the interplay between drugs and fungi in the presence of serum proteins is a rather complex phenomenon and may be clinically relevant given that MIC determination in the presence of serum may be a better predictor of in vivo outcome (12).

In the present study, the concentration-effect relationships of inhibitory and fungicidal activities of amphotericin B, voriconazole, and the three echinocandins caspofungin, micafungin, and anidulafungin against A. fumigatus, A. flavus, and A. terreus clinical isolates were determined with the XTT methodology in the presence and in the absence of serum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates.

A collection of 15 clinical isolates of Aspergillus spp. was used: 5 isolates each of A. fumigatus, A. flavus, and A. terreus. Isolates were kept frozen in solutions of 10% glycerol in sterile normal saline at −70°C, revived by subculturing twice on Sabouraud dextrose agar plates, and incubated at 35°C for 7 to 10 days. Conidial suspensions were prepared by touching a wet cotton swab on the surface of the Aspergillus cultures and then suspended in sterile normal saline containing 0.025% Tween 20. The conidial suspensions were adjusted with a hemacytometer to 4 × 104 conidia/ml, which corresponded to twice the desired final inoculum in normal saline or human serum. Candida krusei ATCC 6258, Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019, and A. fumigatus ATCC MYA-3626 were used as quality control (QC) strains.

Medium.

RPMI 1640 medium with l-glutamine and without bicarbonate, buffered with 0.165 M 3-N-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) (AppliChem, Darmstadt, Germany) to pH 7.0, was used as the growth medium. Human serum was pooled from healthy volunteers and heat inactivated at 56°C for 30 min. Briefly, whole-blood samples in silicon-coated plastic tubes (BD Vacutainer tubes) were centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 10 min, and supernatant serum was pooled from several samples in 50-ml Falcon tubes which were then incubated in a water bath at 56°C for 30 min with constant swirling. Heat-inactivated human serum was aliquoted into Falcon tubes, stored at −70°C, and used within 7 to 10 days.

Since medium and pH changes may have significant effects on the in vitro potencies of echinocandins and amphotericin B (21), the similar pHs and osmolalities of growth medium with and without 50% human serum were confirmed with the pH meter and by the percentage of hemolysis of erythrocytes, respectively. For the hemolysis experiment, 106 human erythrocytes/per ml were incubated at 37οC for 30 min with serial dilutions (up to 1/10) of both growth media in sterile distilled water (dH2O), with 100% sterile dH2O serving as a positive control (100% hemolysis) and 100% human serum as a negative control (0% hemolysis), and counted in hemacytometer.

Antifungal agents.

The antifungal agents were supplied by their respective manufacturers as pure powders: caspofungin acetate (Merck, Athens, Greece), anidulafungin (Pfizer, Athens, Greece), micafungin (Astellas, Athens, Greece), voriconazole (Pfizer), and amphotericin B (MP Biomedicals, Bioline, Athens, Greece). Stock solutions were prepared by dissolving drug powders in dimethyl sulfoxide (voriconazole, anidulafungin, and amphotericin B) or water (caspofungin and micafungin) and were stored at −70°C until use. Following the principles of CLSI M38-A2, serial dilutions at twice the desired concentration were prepared in double-strength test medium (RPMI 1640 medium with MOPS) in 96-well flat-bottom microtitration plates (Costar 3596; Corning Inc., Antisel, Athens, Greece). The final concentrations of antifungal agents, after the addition of conidial inocula, ranged from 8 to 0.03 mg/liter. Lower concentrations were used in case of off-scale antifungal effects.

XTT and menadione.

The XTT {2,3-bis[2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-(sulphenylamino)carbonyl]-2H-tetrazolium hydroxide} sodium salt (Applichem, Bioline, Athens, Greece) was dissolved in water before use. Menadione (Applichem, Bioline) was initially dissolved in absolute ethanol at a concentration of 58 × 10−3 M. A working solution of 0.5 mg/ml of XTT with 31.25 × 10−6 Μ menadione was prepared in sterile water.

Susceptibility testing.

The in vitro susceptibilities of Aspergillus isolates to amphotericin B, voriconazole, and all three echinocandins were tested based on the CLSI M38-A2 method. Twofold serial dilutions of antifungal drugs in 100 μl of double-strength growth medium in flat-bottom 96-well microtitration plates were inoculated with 100 μl of conidial suspensions in saline or 100% human serum. Plates were shaken for 10 s and incubated at 35°C for 48 h when fungal growth in each well was quantified with the XTT methodology (see below) in order to assess inhibitory and fungicidal activities. All experiments were performed in triplicates. The minimum effective concentrations (MEC) of caspofungin, micafungin, and anidulafungin were macroscopically and microscopically determined as the lowest drug concentrations with prominent growth reduction and short, stubby, and aberrant hyphae, respectively, whereas the MICs of amphotericin B and voriconazole were determined as the lowest drug concentrations showing complete inhibition of growth.

Inhibitory activity.

Inhibitory activities of antifungal drugs were assessed using the XTT methodology previously described (22, 23). Briefly, after the 48 h of incubation, 50 μl of the XTT-menadione working solution was added to each well, yielding final concentrations of 0.1 mg/ml of XTT and 6.25 × 10−6 M menadione. Subsequently, the microtitration plates were incubated at 35°C for 2 h. Plates were shaken for 1 to 2 min (Wallac Plate Shake 1296-004; Wallac OY, Turku, Finland) until the formazan derivatives were completely dissolved, and the color absorbance (A) was measured spectrophotometrically at 450 nm, with the reference wavelength at 630 nm (Infinite F200; Tecan, Austria). After background absorbance (Abackground) (absorbance of conidium-free plates processed in the same way as the inoculated plates) was subtracted, the percentage of growth at each drug concentration (Awell) with and without serum was calculated based on the absorbance of the drug-free control (Acontrol) with and without serum, respectively, as 100 × (Awell −Awell background)/(Acontrol − Acontrol background). It has been shown that the MICs of amphotericin B and voriconazole and the MEC of echinocandins correspond to the lowest drug concentration with <10% and ∼50% growth, respectively, as determined with the XTT methodology (22, 23).

Fungicidal activity.

After inhibitory activities were estimated as described above, fungicidal activities were determined as previously described (8). Briefly, the contents of all clear wells and the well at 0.5× MIC of the 96-well plates were carefully aspirated and washed twice with 200 μl of normal saline (prewarmed at 35°C) with gentle agitation. Fresh medium was added to each well, and microtitration plates were incubated at 35°C for 24 h, after which 50 μl of the XTT-menadione working solution was added to each well and the plates were further incubated at 35°C for 2 h. After plates were shaken for 1 to 2 min, the color absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically at 450 nm, with the reference wavelength at 630 nm (Infinite F200; Tecan, Austria), and the percentage of fungal growth was calculated as described above. It has been previously shown that the minimal fungicidal concentrations (MFC) of amphotericin B and voriconazole correspond to the lowest drug concentration with <10% growth as determined with this new XTT methodology (8).

Statistical analysis.

The percentage of fungal growth measured from the inhibitory and fungicidal experiments was analyzed with nonlinear regression analysis based on the sigmoidal Emax model with variable slope described by the equation E = Emin+ (Emax − Emin) × Cn/(Cn + IC50n), where Emax is maximal growth at the drug-free control for the inhibitory experiments and at 0.5× MIC for the fungicidal experiments, Emin is the minimal growth observed at high drug concentrations, C is the drug concentration, IC50 is the drug concentration corresponding to 50% of the value obtained by subtracting Emin from Emax, and n is the hillslope (GraphPad Prism 5.0 software, San Diego, CA). The Emax was globally fitted among different data sets, whereas all the other parameters were individually fitted for each isolate. Based on this equation, the near-maximum inhibitory (IC10) and fungicidal (FC10) concentrations were calculated using the interpolation function of GraphPad Prism 5.0 as the concentration corresponding to 10% of the value obtained by subtracting Emin from Emax from the inhibitory and fungicidal experiments, respectively. This endpoint corresponded to 10% and ∼50% growth for the concentration-effect curves of amphotericin B/voriconazole and echinocandin, respectively. The Emin from the inhibitory experiments was also calculated for each isolate in absence and in the presence of human serum. In addition, the FC10/IC10 ratio was calculated in order to assess the fungistatic (FC10/IC10 > 4) versus fungicidal (FC10/IC10 < 4) action (8) and whether the differences in fungicidal activities are due to differences observed in inhibitory activities, since an increase of IC10 will result in an increase in FC10. All comparisons were assessed statistically with the paired Student t test for each species after log 2 transformation in order to approximate normal distribution as confirmed with the Kologorov-Smirnof normality test. A P value lower than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

In vitro activities without serum.

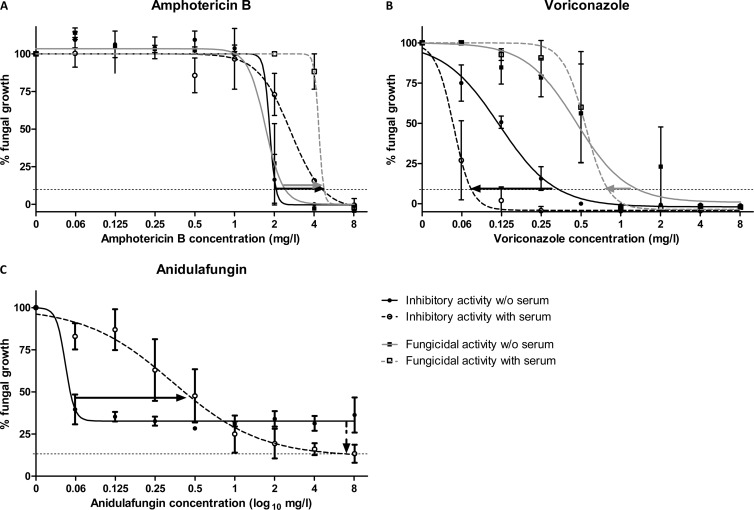

The MICs of the QC strains were within the reference ranges (8). The inhibitory and fungicidal activities of amphotericin B and voriconazole based on the XTT methodology followed a sigmoid pattern, with fungal growth ranging from 100 to 0% as shown in Fig. 1. The inhibitory and fungicidal concentration-effect curves of voriconazole were shallower than those of amphotericin B, indicating that voriconazole exhibited stronger sub-MIC and sub-MFC antifungal activities than did amphotericin B. Echinocandins did not show complete growth inhibition or any fungicidal activity at the concentrations tested in the absence of serum. The lowest IC10 were found for the echinocandins (median IC10, 0.04 to 0.32 mg/liter) against the three Aspergillus spp., with caspofungin showing the highest median IC10 (Table 1). For some isolates the paradoxical increase of fungal growth was observed at high concentrations more pronounced for A. fumigatus isolates; these concentrations were excluded from the Emax model nonlinear regression analysis. The highest median amphotericin B and voriconazole IC10 were found for A. terreus (1.57 and 0.56 mg/liter, respectively) compared to A. flavus (1.38 and 0.19 mg/liter) and A. fumigatus (1.01 and 0.3 mg/liter). The minimum percentage of fungal growth (Emin) which was observed at high concentrations of echinocandins was higher for A. fumigatus (46 to 56%) than the other two Aspergillus spp. (25 to 36%) in the absence of serum (Table 2). Although voriconazole median FC10 (1.66 mg/liter for A. fumigatus, 1.26 mg/liter for A. flavus, and 9.15 mg/liter for A. terreus) were similar to amphotericin B median FC10 (2.1, 2.22, and 6.39 mg/liter, respectively), the voriconazole FC10/IC10 ratio (7.58 to 9.89) was significantly larger than the amphotericin B ratios (1.42 to 4.07) in the absence of serum for all Aspergillus spp. (Table 3).

Fig 1.

Concentration-effect curves of amphotericin B (A), voriconazole (B), and anidulafungin (C) with (open symbols and dashed regression lines) and without (closed symbols and solid regression lines) 50% serum based on inhibitory (circles and black lines) and fungicidal (squares and gray lines) activities against an Aspergillus flavus isolate. Error bars represent standard errors of the means, and lines are the regression lines of the Emax model. No fungicidal activity was found for anidulafungin. Horizontal dotted lines represent the level of 10% growth. Horizontal black and gray arrows represent the shift of inhibitory and fungicidal concentration-effect curves, respectively, whereas the vertical dotted arrow in panel C represents the reduction of the minimal growth Emin at supra-MEC concentrations.

Table 1.

Effect of serum on inhibitory activities of antifungal drugs against different Aspergillus species based on IC10 obtained from the nonlinear regression analysis

| Species (no. of isolates) | Druga | Median (range) IC10 (mg/liter) |

Median (range) fold change | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without serum | With serum | ||||

| A. fumigatus (5) | AMB | 1.01 (0.73–1.69) | 2.58 (1.65–3.7) | 2.96 (1.11–5.06) | 0.044 |

| VRC | 0.3 (0.15–0.51) | 0.13 (0.07–0.21) | 0.42 (0.31–0.88) | 0.021 | |

| CAS | 0.32 (0.24–0.4) | 0.8 (0.39–3.87) | 5.46 (2.04–18.24) | 0.092 | |

| MICA | 0.08 (0.05–0.12) | 0.44 (0.18–1.26) | 5.69 (1.77–16.18) | 0.068 | |

| ANID | 0.10 (0.03–0.18) | 0.67 (0.49–1.68) | 7.28 (4.91–19.4) | 0.022 | |

| A. flavus (5) | AMB | 1.38 (1.34–2.39) | 5.13 (4.45–6.57) | 3.72 (1.91–4.92) | 0.002 |

| VRC | 0.19 (0.17–0.37) | 0.08 (0.04–0.14) | 0.35 (0.24–0.69) | 0.012 | |

| CAS | 0.28 (0.24–0.36) | 1.71 (0.46–3.49) | 13.44 (3.42–19.56) | 0.032 | |

| MICA | 0.06 (0.06–0.07) | 0.37 (0.27–1.1) | 6.14 (4.14–17.29) | 0.043 | |

| ANID | 0.10 (0.08–0.12) | 1.25 (0.73–2.54) | 12.15 (6.25–20.62) | 0.013 | |

| A. terreus (5) | AMB | 1.57 (1.11–3.07) | 4.26 (3.29–6.18) | 2.71 (1.38–4.51) | 0.011 |

| VRC | 0.56 (0.23–5.9) | 0.22 (0.15–4.3) | 0.53 (0.31–0.73) | 0.116 | |

| CAS | 0.15 (0.07–1.2) | 0.24 (0.14–2.85) | 1.27 (0.27–40.22) | 0.581 | |

| MICA | 0.07 (0.06–0.09) | 0.45 (0.29–1.17) | 7.06 (3.22–17.35) | 0.027 | |

| ANID | 0.04 (0.04–0.06) | 0.48 (0.4–0.74) | 8.77 (7.33–14.49) | 0.001 | |

AMB, amphotericin B; VRC, voriconazole; CAS, caspofungin; MICA, micafungin; ANID, anidulafungin.

Table 2.

Effect of serum on growth observed at high concentrations of echinocandins

| Species (no. of isolates) | Druga | Median (range) Emin (% growth) |

Median (range) % growth reduction | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without serum | With serum | ||||

| A. fumigatus (5) | CAS | 46.86 (42.5–68.45) | 8.28 (0–10.18) | 40.72 (67.26–32.75) | 0.002 |

| MICA | 56.38 (30.1–72.1) | 6.07 (0–11.85) | 50.26 (90.25–24.03) | 0.009 | |

| ANID | 50.55 (21.41–57.82) | 4.28 (0–13.55) | 40.84 (57.82–21.41) | 0.003 | |

| A. flavus (5) | CAS | 25.54 (19.37–28.63) | 8.14 (3.81–9.98) | 17.06 (21.93–11.58) | 0.001 |

| MICA | 35.19 (27.52–37.52) | 5.43 (0–5.6) | 29.75 (37.52–22.33) | 0.000 | |

| ANID | 27.13 (24.14–32.29) | 7.36 (4.08–14.14) | 18.15 (25.21–16.48) | 0.000 | |

| A. terreus (5) | CAS | 34.28 (30.6–43.33) | 20.93 (14.2–23.79) | 13.85 (29.13–6.94) | 0.017 |

| MICA | 36.63 (29.24–45.48) | 10.91 (4.49–20.87) | 28.63 (32.14–7.91) | 0.008 | |

| ANID | 36.36 (27.84–42.21) | 21.98 (15.83–25.95) | 10.82 (16.85–9.25) | 0.001 | |

CAS, caspofungin; MICA, micafungin; ANID, anidulafungin.

Table 3.

Effect of serum on EC10 for each Aspergillus species and antifungal drug

| Species (no. of isolates) | Druga | Index | Median (range) fungicidal activity |

Median (range) fold change | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without serum | With serum | |||||

| A. fumigatus (5) | AMB | FC10 (mg/liter) | 2.1 (1.25–4.38) | 4.15 (3.21–24.63) | 2.7 (1.17–7.28) | 0.024 |

| FC10/IC10 | 2.09 (0.74–5.1) | 0.99 (0.83–14.93) | 0.68 (0.4–6.56) | 0.540 | ||

| VRC | FC10 (mg/liter) | 1.66 (0.67–86.17) | 0.74 (0.37–25.07) | 0.45 (0.29–1.65) | 0.375 | |

| FC10/IC10 | 7.71 (2.26–169.22) | 11.13 (3.52–117.67) | 1.44 (0.7–1.88) | 0.657 | ||

| A. flavus (5) | AMB | FC10 (mg/liter) | 2.22 (1.26–6.34) | 8.89 (4.46–11.44) | 4.44 (1.34–7.31) | 0.017 |

| FC10/IC10 | 1.42 (0.53–4.59) | 1.65 (1–2.02) | 0.9 (0.36–3.83) | 0.658 | ||

| VRC | FC10 (mg/liter) | 1.26 (0.41–6.86) | 0.34 (0.28–0.66) | 0.22 (0.05–0.68) | 0.136 | |

| FC10/IC10 | 7.58 (1.23–18.73) | 3.3 (2.62–9.89) | 0.59 (0.14–2.69) | 0.202 | ||

| A. terreus (5) | AMB | FC10 (mg/liter) | 6.39 (2.22–88.85) | 10.45 (7.52–13.67) | 1.71 (0.11–6.16) | 0.521 |

| FC10/IC10 | 4.07 (1.32–50.49) | 2.08 (1.58–3.33) | 0.82 (0.03–2.27) | 0.321 | ||

| VRC | FC10 (mg/liter) | 9.15 (4.86–12.48) | 5.77 (2.98–18.93) | 0.9 (0.24–1.7) | 0.836 | |

| FC10/EC10 | 9.89 (1.89–53.19) | 26.32 (4.4–32.09) | 2.33 (0.37–3.52) | 0.725 | ||

AMB, amphotericin B; VRC, voriconazole.

Serum effects on inhibitory activities.

Table 1 shows the IC10 of antifungal drugs in the presence and absence of serum, the fold change, and t test P value for each Aspergillus sp. and drug. Overall, the IC10 of amphotericin B and echinocandins were increased (1.27- to 13.44-fold) whereas voriconazole IC10 were decreased (0.35- to 0.53-fold) in the presence of serum. The addition of serum resulted in a 2.96-fold (1.11- to 5.06-fold) increase of amphotericin B IC10 for A. fumigatus (P = 0.044), 3.72-fold (1.91- to 4.92-fold) for A. flavus (P = 0.002), and 2.71-fold (1.38- to 4.51-fold) for A. terreus (P = 0.011), indicating reduction of inhibitory activity. The same overall effect was observed for echinocandins, with median increases of 5.46- to 7.28-fold, 6.14- to 13.44-fold, and 1.27- to 8.77-fold for A. fumigatus, A. flavus, and A. terreus, respectively (P < 0.05 for most drug-species combinations). In contrast, voriconazole IC10 were decreased in the presence of serum 0.42-fold (0.31- to 0.88-fold) for A. fumigatus, 0.35-fold (0.24- to 0.69-fold) for A. flavus, and 0.53-fold (0.31- to 0.73-fold) for A. terreus, indicating enhancement of inhibitory activity.

Serum effects on Emin.

The percentages of growth observed at high concentrations of echinocandins are shown in Table 2, together with the differences in the presence of serum and the t test P value. Overall, the Emins of amphotericin B and voriconazole were not affected by serum (Fig. 1), whereas the Emins of echinocandins were reduced by 10 to 50%, resulting in complete inhibition of fungal growth for many isolates (Table 2). The largest Emins were observed for A. fumigatus and micafungin (median Emin, 56.38%). However, the Emins of all species-echinocandin pairs were reduced in the presence of serum, resulting in complete inhibition of fungal growth of many isolates at concentrations of >1 mg/liter. In particular, the Emin values were decreased from >25% median percent growth without serum to <22% median percent growth in the presence of serum for all Aspergillus spp., resulting in statistically significantly (P < 0.05) decreases of 40.72 to 50.26% for A. fumigatus, 17.06 to 27.75% for A. flavus, and 10.82 to 28.63% for A. terreus. Of note, complete inhibition of growth was observed in the presence of serum for many A. fumigatus isolates. For those isolates for which no growth was observed in the presence of serum, the fungicidal activity of echinocandins was assessed as described above but no fungicidal action was found. Among the three echinocandins, the greatest decreases of Emin were found for micafungin (50.26% for A. fumigatus, 29.75% for A. flavus, and 28.63% for A. terreus). No paradoxical effect was observed in the presence of serum.

Serum effects on fungicidal activities.

The fungicidal activities in terms of FC10 in the presence and absence of serum are shown in Table 3, together with the fold change and the P value. Overall, in the presence of serum, the FC10 of amphotericin B were increased (1.71- to 4.44-fold), whereas voriconazole FC10 were decreased (0.22- to 0.90-fold) (Table 3). In order to assess whether differences of FC10 were related to the differences observed with IC10, the FC10/IC10 ratios were also calculated. Statistically significantly increases of amphotericin B FC10 in the presence of serum were observed for A. fumigatus (2.7-fold; P = 0.024) and A. flavus (4.4-fold; P = 0.017) but not for A. terreus (1.71-fold; P = 0.99). However, the FC10/IC10 ratio did not change significantly (0.68- to 0.9-fold) in the presence of serum, indicating that the increase of FC10 was due to the increase of the IC10. Voriconazole FC10 was reduced in the presence of serum (0.22- to 0.9-fold change) for all Aspergillus spp., whereas the FC10/IC10 ratio increased for A. fumigatus (1.44-fold) and A. terreus (2.33-fold) and decreased for A. flavus (0.59-fold), indicating that voriconazole fungicidal activity against A. flavus may be enhanced. These changes of voriconazole activity were not statistically significant because of the large interstrain variability. Thus, the fungicidal activities of amphotericin B and voriconazole were not significantly affected by serum, since any difference found was due to the effect of serum on inhibitory activities.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that the inhibitory activities of amphotericin B and the echinocandins decreased 4-fold and 13-fold, respectively, whereas those of voriconazole increased 2-fold in the presence of human serum. A second effect of serum on the echinocandins' action was the 10 to 50% enhancement of their in vitro inhibitory activities at concentrations higher than the MEC, where complete growth inhibition and no paradoxical effect were observed in the presence of serum. Regarding the fungicidal activities of antifungal drugs, no effect of serum was observed, since the increase (in case of amphotericin B) or decrease (in case of voriconazole) of fungicidal concentrations (FC) in the presence of serum was associated with the increase of inhibitory concentrations (IC), resulting in no statistically significant change of FC/IC ratios.

Although there are no reports on the effect of human serum on amphotericin B and voriconazole antifungal activity against Aspergillus spp., it was found previously that the MICs of amphotericin B and itraconazole but not of voriconazole increased 1 to 3 twofold in the presence of human albumin against Aspergillus spp. (20). In agreement with the present study, echinocandins' MICs against Aspergillus spp. increased up to 64-fold in the presence of 50% human serum (16, 17). It seems that the activities of highly protein-bound antifungal drugs are reduced in the presence of human serum, whereas the activities of low-grade protein-bound drugs are enhanced. This is in agreement with a study in which the MICs of fluconazole, a low-grade protein-bound drug, were decreased ≥4-fold in the presence of serum, whereas the MICs of three highly protein-bound drugs, itraconazole, ketoconazole, and anidulafungin, were increased against Candida spp. (13, 24). However, the MICs of flucytosine, a low-grade protein-bound drug, were increased, whereas the MICs of posaconazole, a highly protein-bound drug, were decreased in the presence of serum against Candida spp., suggesting more complex interactions between serum and antifungal drugs (13, 18).

The decrease of inhibitory activities of amphotericin B and the echinocandins in the presence of serum could be explained by the free-drug hypothesis, considering the relatively high protein binding, with reported rates of 95% for amphotericin B, 96% for caspofungin, 99% for anidulafungin, and 99.8% for micafungin. However, the increase of the IC in the presence of serum cannot be predicted by the degree of protein binding, since the observed IC without serum were higher than the predicted IC of the free fraction of drugs in the presence of serum. This was also previously found for Aspergillus spp. and Candida spp. (17, 24). Thus, the free-drug hypothesis (the unbound drug is pharmacodynamically active under equilibrium conditions) may not directly apply in vitro for antifungal drugs, and the effect of human serum seems to be unpredictable, indicating that other factors and/or secondary mechanisms may account for the observed in vitro activity. The equilibrium free drug↔protein-bound drug↔fungal target-bound drug in vitro might differ from that in vivo, with the in vitro equilibrium being shifted to the right arm (toward fungal target-bound drug) since drug concentrations remain constant over time. The in vivo equilibrium may be shifted to the left arm (toward free drug) since free drug is constantly eliminated. This equilibrium might also be affected by the type (reversible versus nonreversible) and the strength (weak or strong) of protein binding, like the reversible and weak interaction of micafungin with serum proteins which was used to explain the smaller MIC increase than predicted by the percentage of protein binding (25). Finally, in vivo the volume of drug distribution is much larger than the volume of infection, whereas in vitro the opposite is true. Thus, the activity of antifungal drugs in the presence of serum may be more potent than predicted by the unbound drug in vitro, but not necessarily in vivo.

Serum has a direct effect on the drugs by altering their ability to interact with their target, since it was found that in vitro inhibition of the cell-free glucan synthase by echinocandins could be predicted by the percentage of protein binding (17). However, because the MIC shifts (of fungal cells) were smaller than the effect of serum on pure enzymes, secondary mechanisms were suggested to play a role such as drug transport, as was found for Candida spp. (26). Serum has a direct effect on Aspergillus growth. Human albumin was found to promote conidial germination of A. fumigatus but not of A. flavus or Aspergillus niger and mycelial growth of all three species (19, 20). Another effect of serum on Aspergillus growth is the exogenous import of human cholesterol by A. fumigatus, providing a substitute for fungal membrane ergosterol (27). This effect may contribute to the decreased antifungal activity of amphotericin B in the presence of serum found in the present study, since cholesterol has a lower affinity for amphotericin B (28). Serum may also affect efflux pumps, since it was found that serum repressed the Candida albicans CDR1 efflux pump (29). This may explain the increased antifungal activity of voriconazole in the presence of serum found in the present study, since CDR1-like pumps are involved in the efflux of voriconazole (30). Thus, the net in vitro effect of serum on antifungal activity may be a result of the interaction between factors that affect drug access to the target, e.g., protein binding, drug diffusion, efflux pumps, target affinity, and the dynamics of fungal growth, e.g., germination, hyphal formation, mycelial growth, and growth rate, in the presence of serum and cannot be predicted only by the percentage of protein binding.

The amphotericin B IC10 of A. fumigatus isolates were smaller than the IC10 of the other two Aspergillus spp., although these differences were smaller than 1 twofold dilution. These differences were more pronounced based on the fungicidal activity, particularly in the presence of serum, as previously observed (8). Indeed, comparative animal studies have shown that treatment with a 2.5-mg/kg (of body weight) dose of amphotericin B of experimental murine model of disseminated aspergillosis resulted in 77% survival for A. fumigatus infection but only 15% for A. flavus infections (31). For voriconazole, the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) parameter total area under the concentration-time curve (AUC)/MIC associated with 50% of maximal activity was found to be 115 for C. albicans (or 24 for free AUC/MIC) and only 36 (or 11.2 for free AUC/MIC) for A. fumigatus in murine models of disseminated fungal infections (32, 33). However, taking into account that voriconazole inhibitory activity against A. fumigatus is increased twofold in the presence of serum as found in the present study, the total AUC/MIC associated with 50% maximal activity against Aspergillus approaches the one reported for Candida spp. The similar in vitro activities of caspofungin and anidulafungin in the presence of serum against A. fumigatus are in concordance with animal data demonstrating that caspofungin showed in vivo activity similar to that of anidulafungin, while in vitro IC10 without serum indicated a potency three times smaller (34). Similarly, animal data showed that 5 mg/kg of caspofungin or micafungin resulted in similar in vivo outcomes (spleen and kidney fungal burden and survival) when caspofungin concentrations were two times higher than those of micafungin (35). This difference could be explained by the 2-fold differences of IC10 in the presence of serum (0.8 versus 0.44 mg/liter) but not by the at least 4-fold differences in protein binding (96% versus 99.8%) and the IC10 without serum (0.08 versus 0.32 mg/liter).

Fungicidal experiments showed a fungicidal action (FC/IC < 4) of amphotericin B against A. fumigatus and A. flavus but not against A. terreus and a fungistatic action (FC/IC > 4) of voriconazole against of all three species, although the FC10s were smaller than the corresponding ones of amphotericin B, in agreement with previous studies (8, 36). Serum increased in case of amphotericin B or decreased in case of voriconazole FC10s as a result of IC10 increase. Fungicidal concentrations could better discriminate amphotericin B-resistant A. terreus from the other two species compared to inhibitory activities with and without serum as also previously found (5). Among the three species, voriconazole exhibited the most potent activity against A. flavus and the least against A. terreus. Although fungicidal concentrations correlated better than inhibitory concentrations with in vivo outcome of zygomycosis (37), further studies are needed to explore the usefulness of this parameter in in vitro-in vivo correlation and PK/PD studies, particularly in the neutropenic setting.

In summary, the inhibitory activities of amphotericin B and the echinocandins decreased 4-fold and 13-fold, respectively, whereas those of voriconazole increased 2-fold in the presence of human serum. The free-drug hypothesis may not directly apply in vitro for antifungal drugs, and the effect of human serum seems to be unpredictable, indicating that other factors and/or secondary mechanisms may play role in the observed in vitro activity. PK/PD experiments and in vitro-in vivo correlation studies could explore the applicability of serum-based MICs and fungicidal concentrations of antifungal drugs.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 January 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Patterson TF, Kirkpatrick WR, White M, Hiemenz JW, Wingard JR, Dupont B, Rinaldi MG, Stevens DA, Graybill JR. 2000. Invasive aspergillosis. Disease spectrum, treatment practices, and outcomes. I3 Aspergillus Study Group. Medicine (Baltimore) 79:250–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Groll AH, Walsh TJ. 2002. Antifungal chemotherapy: advances and perspectives. Swiss Med. Wkly. 132:303–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johnson EM, Oakley KL, Radford SA, Moore CB, Warn P, Warnock DW, Denning DW. 2000. Lack of correlation of in vitro amphotericin B susceptibility testing with outcome in a murine model of Aspergillus infection. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 45:85–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mosquera J, Warn PA, Morrissey J, Moore CB, Gil-Lamaignere C, Denning DW. 2001. Susceptibility testing of Aspergillus flavus: inoculum dependence with itraconazole and lack of correlation between susceptibility to amphotericin B in vitro and outcome in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1456–1462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Walsh TJ, Petraitis V, Petraitiene R, Field-Ridley A, Sutton D, Ghannoum M, Sein T, Schaufele R, Peter J, Bacher J, Casler H, Armstrong D, Espinel-Ingroff A, Rinaldi MG, Lyman CA. 2003. Experimental pulmonary aspergillosis due to Aspergillus terreus: pathogenesis and treatment of an emerging fungal pathogen resistant to amphotericin B. J. Infect. Dis. 188:305–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Warn PA, Sharp A, Denning DW. 2006. In vitro activity of a new triazole BAL4815, the active component of BAL8557 (the water-soluble prodrug), against Aspergillus spp. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57:135–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Antachopoulos C, Meletiadis J, Sein T, Roilides E, Walsh TJ. 2008. Comparative in vitro pharmacodynamics of caspofungin, micafungin, and anidulafungin against germinated and nongerminated Aspergillus conidia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:321–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meletiadis J, Antachopoulos C, Stergiopoulou T, Pournaras S, Roilides E, Walsh TJ. 2007. Differential fungicidal activities of amphotericin B and voriconazole against Aspergillus species determined by microbroth methodology. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:3329–3337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. CLSI 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi. Approved standard M38-A2, 2nd ed CLSI, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 10. EUCAST 2008. Technical note on the method for the determination of broth dilution minimum inhibitory concentrations of antifungal agents for conidia-forming moulds. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14:982–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baddley JW, Marr KA, Andes DR, Walsh TJ, Kauffman CA, Kontoyiannis DP, Ito JI, Balajee SA, Pappas PG, Moser SA. 2009. Patterns of susceptibility of Aspergillus isolates recovered from patients enrolled in the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3271–3275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maki K, Matsumoto S, Watabe E, Iguchi Y, Tomishima M, Ohki H, Yamada A, Ikeda F, Tawara S, Mutoh S. 2008. Use of a serum-based antifungal susceptibility assay to predict the in vivo efficacy of novel echinocandin compounds. Microbiol. Immunol. 52:383–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhanel GG, Saunders DG, Hoban DJ, Karlowsky JA. 2001. Influence of human serum on antifungal pharmacodynamics with Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2018–2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kauffman CA, Carver PL. 2008. Update on echinocandin antifungals. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 29:211–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zeitlinger MA, Derendorf H, Mouton JW, Cars O, Craig WA, Andes D, Theuretzbacher U. 2011. Protein binding: do we ever learn? Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:3067–3074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Odabasi Z, Paetznick V, Rex JH, Ostrosky-Zeichner L. 2007. Effects of serum on in vitro susceptibility testing of echinocandins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:4214–4216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Paderu P, Garcia-Effron G, Balashov S, Delmas G, Park S, Perlin DS. 2007. Serum differentially alters the antifungal properties of echinocandin drugs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:2253–2256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lignell A, Lowdin E, Cars O, Chryssanthou E, Sjolin J. 2011. Posaconazole in human serum: a greater pharmacodynamic effect than predicted by the non-protein-bound serum concentration. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:3099–3104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gifford AH, Klippenstein JR, Moore MM. 2002. Serum stimulates growth of and proteinase secretion by Aspergillus fumigatus. Infect. Immun. 70:19–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rodrigues AG, Araujo R, Pina-Vaz C. 2005. Human albumin promotes germination, hyphal growth and antifungal resistance by Aspergillus fumigatus. Med. Mycol. 43:711–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Clavaud C, Beauvais A, Barbin L, Munier-Lehmann H, Latge JP. 2012. The composition of the culture medium influences the beta-1,3-glucan metabolism of Aspergillus fumigatus and the antifungal activity of inhibitors of beta-1,3-glucan synthesis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:3428–3431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Antachopoulos C, Meletiadis J, Sein T, Roilides E, Walsh TJ. 2007. Concentration-dependent effects of caspofungin on the metabolic activity of Aspergillus species. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:881–887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meletiadis J, Mouton JW, Meis JF, Bouman BA, Donnelly JP, Verweij PE. 2001. Colorimetric assay for antifungal susceptibility testing of Aspergillus species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3402–3408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schäfer-Korting M, Korting HC, Rittler W, Obermuller W. 1995. Influence of serum protein binding on the in vitro activity of anti-fungal agents. Infection 23:292–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ishikawa J, Maeda T, Matsumura I, Yasumi M, Ujiie H, Masaie H, Nakazawa T, Mochizuki N, Kishino S, Kanakura Y. 2009. Antifungal activity of micafungin in serum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4559–4562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Paderu P, Park S, Perlin DS. 2004. Caspofungin uptake is mediated by a high-affinity transporter in Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3845–3849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Xiong Q, Hassan SA, Wilson WK, Han XY, May GS, Tarrand JJ, Matsuda SP. 2005. Cholesterol import by Aspergillus fumigatus and its influence on antifungal potency of sterol biosynthesis inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:518–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Baginski M, Resat H, Borowski E. 2002. Comparative molecular dynamics simulations of amphotericin B-cholesterol/ergosterol membrane channels. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1567:63–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yang YL, Lin YH, Tsao MY, Chen CG, Shih HI, Fan JC, Wang JS, Lo HJ. 2006. Serum repressing efflux pump CDR1 in Candida albicans. BMC Mol. Biol. 7:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rajendran R, Mowat E, McCulloch E, Lappin DF, Jones B, Lang S, Majithiya JB, Warn P, Williams C, Ramage G. 2011. Azole resistance of Aspergillus fumigatus biofilms is partly associated with efflux pump activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:2092–2097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Odds FC, Van Gerven F, Espinel-Ingroff A, Bartlett MS, Ghannoum MA, Lancaster MV, Pfaller MA, Rex JH, Rinaldi MG, Walsh TJ. 1998. Evaluation of possible correlations between antifungal susceptibilities of filamentous fungi in vitro and antifungal treatment outcomes in animal infection models. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:282–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Andes D, Marchillo K, Stamstad T, Conklin R. 2003. In vivo pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a new triazole, voriconazole, in a murine candidiasis model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3165–3169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mavridou E, Bruggemann RJ, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE, Mouton JW. 2010. Impact of cyp51A mutations on the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of voriconazole in a murine model of disseminated aspergillosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:4758–4764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lewis RE, Liao G, Hou J, Prince RA, Kontoyiannis DP. 2011. Comparative in vivo dose-dependent activity of caspofungin and anidulafungin against echinocandin-susceptible and -resistant Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:1324–1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Olson JA, George A, Constable D, Smith P, Proffitt RT, Adler-Moore JP. 2010. Liposomal amphotericin B and echinocandins as monotherapy or sequential or concomitant therapy in murine disseminated and pulmonary Aspergillus fumigatus infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:3884–3894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Clancy CJ, Nguyen MH. 1998. In vitro efficacy and fungicidal activity of voriconazole against Aspergillus and Fusarium species. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 17:573–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Salas V, Pastor FJ, Calvo E, Alvarez E, Sutton DA, Mayayo E, Fothergill AW, Rinaldi MG, Guarro J. 2012. In vitro and in vivo activities of posaconazole and amphotericin B in a murine invasive infection by Mucor circinelloides: poor efficacy of posaconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:2246–2250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]