Abstract

Streptomycin at subinhibitory concentrations was found to inhibit quorum sensing in Acinetobacter baumannii. Conditioned medium prepared by growth of A. baumannii in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of streptomycin exhibited reduced activation of two quorum-sensing-regulated genes, abaI, encoding an autoinducer synthase, and A1S_0112. The reduced expression of AbaI resulted in greatly decreased levels of 3-OH-C12-HSL as confirmed by direct analysis using thin-layer chromatography. The effect on acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) signal production was specific to streptomycin, as gentamicin and myomycin had no significant effect at subinhibitory levels.

TEXT

Acinetobacter baumannii is an aerobic Gram-negative nosocomial pathogen possessing mechanisms of resistance to all classes of antibiotics and is responsible for various life-threatening infections, including those of the lung, skin and soft tissue, urinary tract, and bloodstream (1–5). The ability of A. baumannii to survive under adverse conditions, resist desiccation, and form biofilms further complicates treatment and allows these organisms to colonize health care settings (6–11).

Many bacteria respond to their population density by controlling gene expression through quorum sensing, a phenomenon where bacteria respond to small, self-generated diffusible molecules (12, 13). Previous work in our laboratory has identified and characterized an autoinducer synthase (AbaI) required for production of the acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) signal 3-OH-C12-HSL in A. baumannii M2, where it plays a role in biofilm formation (14) and surface motility (15). Other studies have shown a similar role for AbaI in biofilm formation (16).

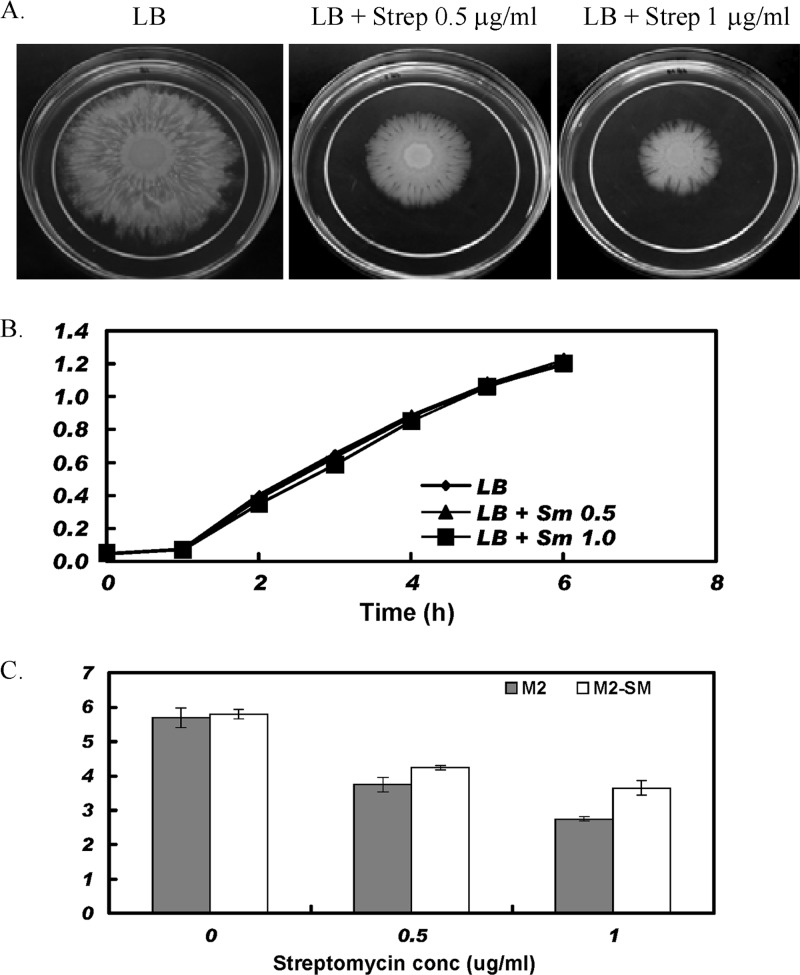

Surface motility has been described in Acinetobacter species (17–22). Motility has been linked to virulence in many pathogenic bacteria and is regulated by diverse mechanisms (23–25). Recent work in our laboratory has demonstrated that motility of A. baumannii strain M2 on low-percentage (0.2 to 4%) agar plates was dependent on quorum sensing, as an abaI mutant exhibited a severe reduction in motility that was rescued by the addition of 3-OH-C12-HSL to plates (15). In the course of studying motility, we found that wild-type A. baumannii M2, with a streptomycin MIC of 16 μg/ml, exhibited a prominent defect in motility in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of streptomycin (0.5 and 1 μg/ml) (Fig. 1A). In order to demonstrate that the reduction in motility in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of streptomycin was not due to effects on growth rate, growth curve analysis was performed. As shown in Fig. 1B, the growth of A. baumannii was not affected by the presence of streptomycin at 0.5 and 1.0 μg/ml. However, to further rule out possible subtle growth effects, we selected a spontaneous mutant of M2 resistant to high levels of streptomycin (>3,200 μg/ml), designated M2-SM. The A. baumannii M2-SM strain also exhibited a reduction in motility in the presence of 0.5 and 1 μg/ml of streptomycin (Fig. 1C). These results indicated that the decrease in motility of A. baumannii M2 in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of streptomycin was not due to a growth defect.

Fig 1.

Motility in the presence of streptomycin. In panel A, the motility of A. baumannii M2 is shown on modified LB (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% NaCl) containing 0.3% Eiken either unsupplemented or containing streptomycin at 0.5 or 1 μg/ml. A. baumannii M2 was grown overnight in 3 ml of modified LB broth, and a 1-μl drop was placed on the surface of each plate. Plates were photographed when the migration on the LB-only plate reached the outer edge at 37°C. In panel B, a growth curve analysis of A. baumannii M2 is shown. M2 was grown overnight in 3 ml LB and adjusted to an A600 of 0.05 in 3 ml fresh LB only or in LB with streptomycin at concentrations of 0.5 and 1.0 μg/ml and shaken at 225 rpm at 37°C. The optical density was then monitored at hourly intervals. In panel C, the migration of wild-type M2 or the M2-SM mutant resistant to high levels of streptomycin was monitored on 0.3% Eiken agar plates. The values shown represent migration distances in centimeters. Results are the means ± standard deviations (SD) from three independent experiments performed in duplicates. The statistical significance was determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (P < 0.05).

Subinhibitory concentrations of streptomycin inhibits quorum sensing.

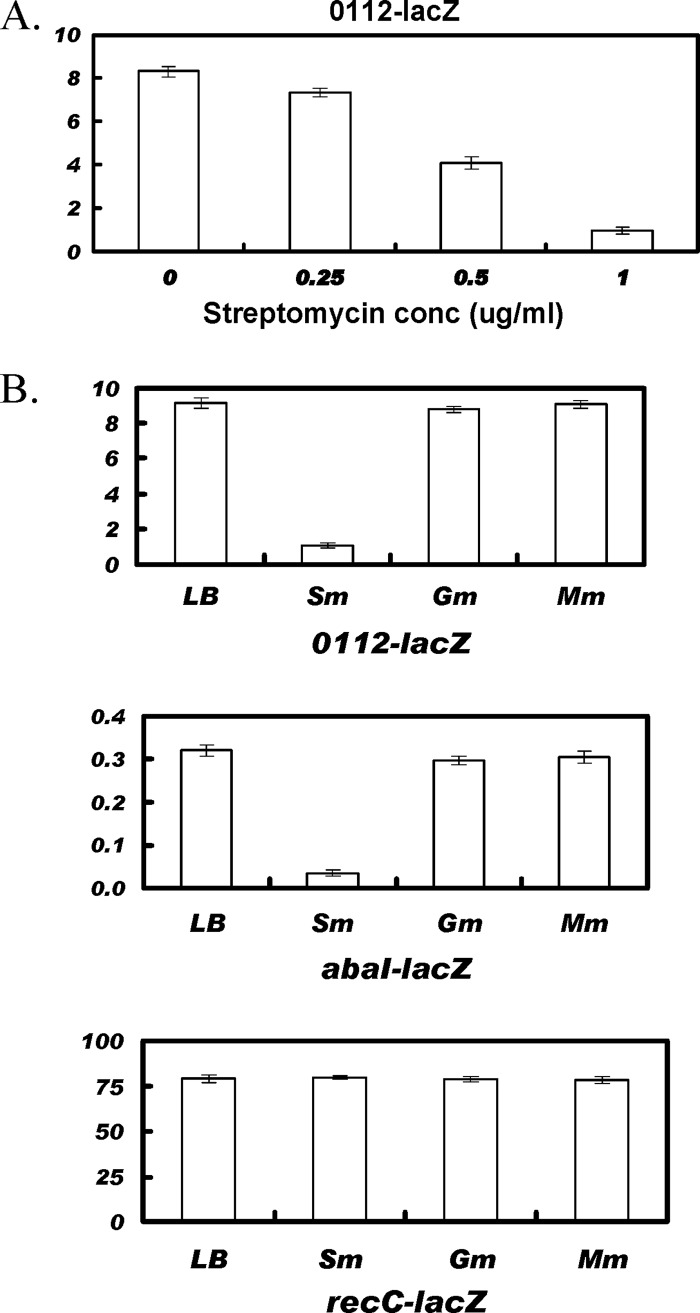

Previously, the motility of A. baumannii M2 was shown to be dependent on quorum sensing (15). Therefore, the possibility that streptomycin decreased motility by altering quorum sensing was investigated. Previous work in our laboratory has identified two quorum-sensing-regulated genes, abaI and A1S_0112 (14, 15). To investigate the effect of streptomycin on quorum sensing, the expression of a transcriptional lacZ fusion to the A1S_0112 was assayed in various subinhibitory concentrations of streptomycin. The expression levels for A1S_0112-lacZ decreased with increasing concentrations of streptomycin and were reduced by 2.1- and 8.4-fold at streptomycin concentrations of 0.5 μg/ml and 1 μg/ml, respectively (Fig. 2A).

Fig 2.

Streptomycin inhibits expression of quorum-sensing-regulated genes. In panel A, the expression of A1S_0112-lacZ in the presence of streptomycin is shown. Cells were grown overnight in 3 ml LB and adjusted to an A600 of 0.05 in 3 ml fresh LB containing streptomycin at concentrations of 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 μg/ml and shaken at 37°C. The cells were harvested at an A600 of 1.0 and assayed for β-galactosidase activity. The expression levels were calculated in terms of Miller units. In panel B, the expression of A1S_0112-lacZ, abaI-lacZ, and recC-lacZ in conditioned medium is shown. Conditioned medium was prepared by growing A. baumannii M2 in LB only or in the presence of LB plus either streptomycin (1 μg/ml), gentamicin (0.1 μg/ml), or myomycin (0.25 μg/ml) to an optical density of 1.0. A. baumannii M2 strains with the indicated lacZ fusions were grown overnight in 3 ml LB and adjusted to an A600 of 0.05 in 3 ml of each conditioned medium and shaken at 37°C. The cells were harvested at an A600 of 0.3 and assayed for β-galactosidase activity (Miller units).

To test if the above-described effect of subinhibitory concentrations of streptomycin on quorum sensing resulted from decreased quorum-sensing signal activity, conditioned medium was prepared by growing the M2 strain to a density of A600 of 1.0 in 30 ml LB medium alone or with streptomycin at concentrations of 1 μg/ml. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation to obtain a clear supernatant which was adjusted to a pH of 7.0 and filter sterilized. Tryptone was added to a final concentration of 0.5% to the filtrate and used as conditioned medium. Conditioned medium with gentamicin or myomycin was prepared in a similar way with concentrations of 0.1 μg/ml and 0.25 μg/ml, respectively. A 9-fold decrease in the expression of A1S_0112 was found in conditioned medium prepared in the presence of streptomycin, relative to LB only (Fig. 2B). A similar effect was also observed with the quorum-sensing-regulated abaI-lacZ fusion (Fig. 2B).

To determine if the reduced signal activity in conditioned medium was due to a general effect of aminoglycosides on protein synthesis, the expression levels of A1S_0112 and abaI were examined in conditioned medium prepared in the presence of gentamicin or myomycin at 0.1 μg/ml and 0.25 μg/ml, respectively, representing concentrations just below that which resulted in growth inhibition (data not shown). A slight decrease was seen in the expression of A1S_0112-lacZ or abaI-lacZ in conditioned medium prepared in the presence of gentamicin, but no effect was seen with myomycin (Fig. 2B). In addition, a control fusion, recC-lacZ, that was not quorum sensing regulated was used and has been described previously (26). Expression of this control recC-lacZ fusion was not altered in any of the conditioned medium preparations, demonstrating that the loss of activation of the quorum-sensing-regulated fusions was due to the decrease in production of quorum-sensing molecules and not by the action of residual streptomycin on protein synthesis.

Direct inhibition of 3-OH-C12-HSL signal production by streptomycin.

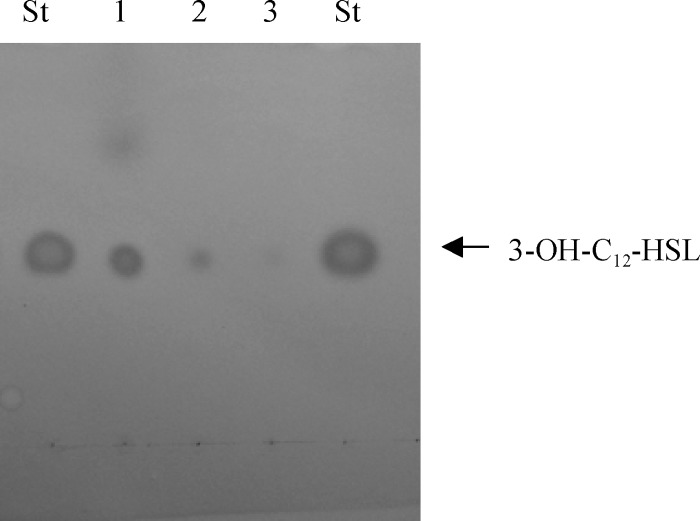

The above-described data suggested a direct effect of streptomycin on the production of 3-OH-C12-HSL. However, it was also possible that streptomycin resulted in the production of a molecule that inhibited the activity of 3-OH-C12-HSL. Therefore, to directly examine the effect of subinhibitory concentrations of streptomycin on 3-OH-C12-HSL signal accumulation, conditioned medium was prepared and analyzed on a reversed-phase C18 thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plate. To detect the signal, the TLC plate was dried and then overlaid with a soft agar lawn containing the Agrobacterium tumefaciens traG-lacZ biosensor, which can be activated by 3-OH-C12-HSL, resulting in a blue spot in the agar overlay. In Fig. 3, compared to standards, the accumulation of 3-OH-C12-HSL was greatly reduced in conditioned medium prepared from cells grown in the presence of 0.5 or 1 μg/ml of streptomycin.

Fig 3.

Bioassay for the production of 3-OH-C12-HSL. The production of 3-OH-C12-HSL by A. baumannii M2 was assayed using Agrobacterium tumefaciens traG::lacZ fusion as described previously by Niu et al. (14). Cell-free supernatant from growth of A. baumannii M2 in LB to an A600 of 1.0 was extracted with acidified ethyl acetate (0.01%). The extract was concentrated by drying under a gentle stream of air down to 100 μl. The concentrated extract (5 μl) was applied to a C18 reverse phase thin-layer chromatography plate and developed in a glass chamber with methanol-water (60:40). The developed TLC plate was overlaid with a 0.7% soft agar lawn containing X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) and the A. tumefaciens traG::lacZ indicator strain and was incubated at 28°C until blue spots appeared, typically 24 h. Standards of 3-OH-C12-HSL at 3 uM (designated St) were added on either side of the conditioned medium samples. Lane 1 represents conditioned medium prepared from LB medium. Lane 2 represents conditioned medium prepared from LB with streptomycin (0.5 μg/ml). Lane 3 represents conditioned medium prepared from LB with streptomycin (1 μg/ml).

Streptomycin acts as an antagonist of 3-OH-C12-HSL.

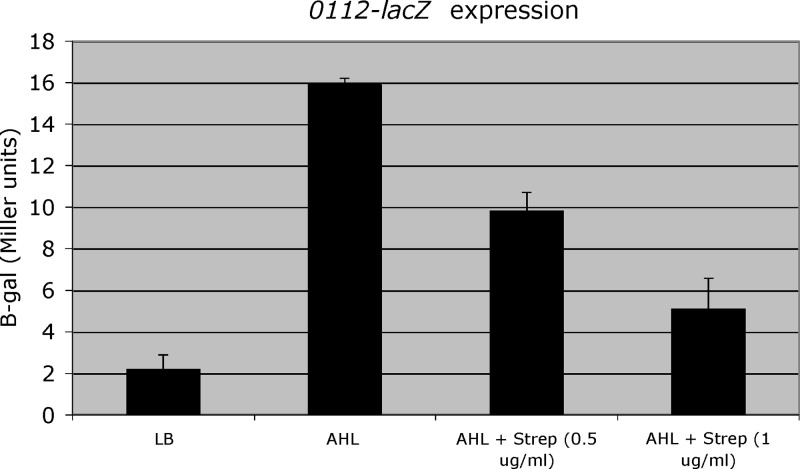

To determine if streptomycin could antagonize the ability of exogenous 3-OH-C12-HSL to act as a quorum-sensing signal, A. baumannii M2 containing the A1S_0112-lacZ fusion was grown to early log phase in LB medium containing 3-OH-C12-HSL at a concentration of 1 μM either with or without streptomycin at concentrations of 0.5 or 1 μg/ml. As seen in Fig. 4, the addition of streptomycin decreased the 3-OH-C12-HSL-mediated activation of A1S_0112-lacZ by 39% and 68% at streptomycin concentrations of 0.5 μg/ml and 1 μg/ml, respectively.

Fig 4.

Expression of A1S_0112-lacZ in the presence of 3-OH-C12-HSL. A. baumannii M2 with A1S_0112-lacZ fusion was grown overnight in 3 ml LB and adjusted to an A600 of 0.05 in 3 ml fresh LB. AHL was added at 1 μM. Streptomycin was added to LB at the indicated concentrations. Cells were harvested at an A600 of 0.3 and assayed for β-galactosidase activity in Miller units.

In summary, data from this study suggest that the inhibition of quorum sensing by subinhibitory concentrations of streptomycin results from decreased transcription of the abaI gene, encoding the autoinducer synthase responsible for 3-OH-C12-HSL production (14). Currently, the mechanism responsible for the decreased abaI transcription is unknown. Our findings are reminiscent of those of Tateda et al., who found that subinhibitory concentrations of azithromycin inhibit quorum-sensing signal production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (27). Although, like azithromycin, the aminoglycosides can alter a wide variety of cellular pathways via protein synthesis inhibition (28–32), the inhibition of quorum sensing in A. baumannii does not appear to be the result of protein synthesis inhibition. This is based on the finding that two other aminoglycosides, gentamicin and myomycin, when used at concentrations just below their MIC, did not significantly alter quorum sensing. Furthermore, use of myomycin, which may have the same target site as streptomycin, indicates that a unique aspect of streptomycin may be responsible for the inhibitory effects (33). The ability of streptomycin to inhibit the ability of exogenous 3-OH-C12-HSL to activate quorum-sensing-dependent gene expression suggests that streptomycin itself may act as a 3-OH-C12-HSL antagonist and interfere with the signal binding to the AbaR protein, which directly activates the abaI gene (14). Since the abaI gene is subject to a positive feedback activation loop via 3-OH-C12-HSL and AbaR, this decreased transcription would directly lead to a reduction in quorum-sensing signal production. However, at this time, it is also a possibility that streptomycin directly inhibits the production or activity of the AbaI protein, which in turn would decrease the quorum-sensing response via reduced 3-OH-C12-HSL signal production. Regardless of the mechanism, our data point to the possible use of streptomycin in treatment therapies to inhibit quorum sensing and possibly reduce the virulence of A. baumannii.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Julian Davies for the suggestion to use myomycin in this study and for providing this antibiotic.

This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the Atlanta Research and Education Foundation to P.N.R. and by R01AI072219-01A1 from the National Institutes of Health. P.N.R. is supported by a Research Career Scientist award from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 January 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Bergogne-Bérézin E, Towner KJ. 1996. Acinetobacter spp. as nosocomial pathogens: microbiological, clinical, and epidemiological features. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 9:148–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Doughari HJ, Ndakidemi PA, Human IS, Benade S. 2011. The ecology, biology and pathogenesis of Acinetobacter spp.: an overview. Microbes Environ. 26:101–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Joly-Guillou ML. 2005. Clinical impact and pathogenicity of Acinetobacter. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 11:868–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dijkshoorn L, Nemec A, Seifert H. 2007. An increasing threat in hospitals: multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:939–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Perez F, Hujer AMKM, Hujer Decker BK, Rather PN, Bonomo RA. 2007. Global challenge of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:3471–3484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Villers D, Espaze E, Coste-Burel M, Giauffret F, Ninin E, Nicolas F, Richet H. 1998. Nosocomial Acinetobacter baumannii infections: microbiological and clinical epidemiology. Ann. Intern. Med. 129:182–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Antunes LC, Imperi F, Carattoli A, Visca P. 2011. Deciphering the multifactorial nature of Acinetobacter baumannii pathogenicity. PLoS One 6:e22674 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cerqueira GM, Peleg AY. 2011. Insights into Acinetobacter baumannii pathogenicity. IUBMB Life 63:1055–1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gaddy JA, Actis LA. 2009. Regulation of Acinetobacter baumannii biofilm formation. Future Microbiol. 4:273–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL. 2008. Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. 21:538–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tomaras AP, Dorsey CW, Edelmann RE, Actis LA. 2003. Attachment to and biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces by Acinetobacter baumannii: involvement of a novel chaperone-usher pili assembly system. Microbiology 149:3473–3484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Kievit TR, Iglewski BH. 2000. Bacterial quorum sensing in pathogenic relationships. Infect. Immun. 68:4839–4849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Miller MB, Bassler BL. 2001. Quorum sensing in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55:165–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Niu C, Clemmer KM, Bonomo RA, Rather PN. 2008. Isolation and characterization of an autoinducer synthase from Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Bacteriol. 190:3386–3392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Clemmer KM, Bonomo RA, Rather PN. 2011. Genetic analysis of surface motility in Acinetobacter baumannii. Microbiology 157:2534–2544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Anbazhagan D, Mansor M, Yan GO, Md Yusof MY, Hassan H, Sekaran SD. 2012. Detection of quorum sensing signal molecules and identification of an autoinducer synthase gene among biofilm forming clinical isolates of Acinetobacter spp. PLoS One 7:e36696 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barker J, Maxted H. 1975. Observations on the growth and movement of Acinetobacter on semi-solid media. J. Med. Microbiol. 8:443–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eijkelkamp BA, Stroeher UH, Hassan KA, Papadimitrious MS, Paulsen IT, Brown MH. 2011. Adherence and motility characteristics of clinical Acinetobacter baumannii isolates. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 323:44–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Henrichsen J. 1984. Not gliding but twitching motility of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J. Clin. Pathol. 37:102–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McQueary CN, Kirkup BC, Si Y, Barlow M, Actis LA, Craft DW, Zurawski DV. 2012. Extracellular stress and lipopolysaccharide modulate Acinetobacter baumannii surface associated motility. J. Microbiol. 50:434–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mussi MA, Gaddy JA, Cabruja M, Arivett BA, Viale AM, Rasia R, Actis LA. 2010. The opportunistic human pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii senses and responds to light. J. Bacteriol. 192:6336–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Skiebe E, de Berardinis V, Morczinek P, Kerrinnes T, Faber F, Lepka D, Hammer B, Zimmermann O, Ziesing S, Wichelhaus TA, Hunfeld KP, Borgmann S, Grobner S, Higgins PG, Seifert H, Busse HJ, Witte W, Pfeifer Y, Wilharm G. 2012. Surface associated motility, a common trait of clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii depends on 1,3 diaminopropane. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 302:117–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harshey RM. 2003. Bacterial motility on a surface: many ways to a common goal. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:249–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Josenhans C, Suerbaum S. 2002. The role of motility as a virulence factor in bacteria. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291:605–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shi W, Sun H. 2002. Type IV pilus-dependent motility and its possible role in bacterial pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 70:1–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saroj SD, Clemmer KM, Bonomo RA, Rather PN. 2012. Novel mechanism for fluoroquinolone resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:4955–4957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tateda K, Comte R, Pechere JC, Kohler T, Yamaguchi K, Van Delden C. 2001. Azithromycin inhibits quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chem. 45:1930–1933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Curran HR, Evans FR. 1947. Stimulation of sporogenic and nonsporogenic bacteria by traces of penicillin or streptomycin. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 64:231–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Davies J, Gilbert W, Gorini L. 1964. Streptomycin, suppression, and the code. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 51:883–890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Davies J, Gorini L, Davis BD. 1965. Misreading of RNA codewords induced by aminoglycoside antibiotics. Mol. Pharmacol. 1:93–106 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Davies J, Cannon M, Mauer MB. 1988. Myomycin: mode of action and mechanisms of resistance. J. Antibiot. 41:366–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bryan LE, Kwan S. 1983. Roles of ribosomal binding, membrane potential, and electron transport in bacterial uptake of streptomycin and gentamicin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 23:835–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kornder JD. 2002. Streptomycin revisited: molecular action in the microbial cell. Med. Hypotheses 58:34–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]