Abstract

Onychomycosis is a common fungal nail infection in adults that is difficult to treat. The in vitro antifungal activity of efinaconazole, a novel triazole antifungal, was evaluated in recent clinical isolates of Trichophyton rubrum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Candida albicans, common causative onychomycosis pathogens. In a comprehensive survey of 1,493 isolates, efinaconazole MICs against T. rubrum and T. mentagrophytes ranged from ≤0.002 to 0.06 μg/ml, with 90% of isolates inhibited (MIC90) at 0.008 and 0.015 μg/ml, respectively. Efinaconazole MICs against 105 C. albicans isolates ranged from ≤0.0005 to >0.25 μg/ml, with 50% of isolates inhibited (MIC50) by 0.001 and 0.004 μg/ml at 24 and 48 h, respectively. Efinaconazole potency against these organisms was similar to or greater than those of antifungal drugs currently used in onychomycosis, including amorolfine, ciclopirox, itraconazole, and terbinafine. In 13 T. rubrum toenail isolates from onychomycosis patients who were treated daily with topical efinaconazole for 48 weeks, there were no apparent increases in susceptibility, suggesting low potential for dermatophytes to develop resistance to efinaconazole. The activity of efinaconazole was further evaluated in another 8 dermatophyte, 15 nondermatophyte, and 10 yeast species (a total of 109 isolates from research repositories). Efinaconazole was active against Trichophyton, Microsporum, Epidermophyton, Acremonium, Fusarium, Paecilomyces, Pseudallescheria, Scopulariopsis, Aspergillus, Cryptococcus, Trichosporon, and Candida and compared favorably to other antifungal drugs. In conclusion, efinaconazole is a potent antifungal with a broad spectrum of activity that may have clinical applications in onychomycosis and other mycoses.

INTRODUCTION

Onychomycosis (tinea unguium) is a chronic fungal infection of the nail characterized by nail discoloration, thickening, and deformity (1). The disease, although not life-threatening, can markedly affect quality of life and well-being (1). It is the most common nail disorder in older adults, frequently involving several nails and affecting the toenail in 80% of cases (2). Onychomycosis can be caused by dermatophytes, nondermatophytes, and yeasts, and the species prevalence in nail infections varies with geographical location, climate, and migration (3).

Dermatophytes, mainly Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton mentagrophytes, are the predominant causative agents of fingernail and toenail onychomycosis, accounting for approximately 50 to 90% of cases, with infection prevalence in toenails much higher than in fingernails (3–6).

The role of nondermatophytes and yeasts as sole causative agents of onychomycosis has not been fully established, and in several cases, these organisms are considered to be colonizing organisms or contaminants rather than pathogens (6, 7). However, in recent years, yeasts, as well as other nondermatophytes, have been increasingly recognized as pathogens in fingernail infections (6, 8). Isolation of an organism from infected nail tissue is not proof that it is the causative pathogen, and positive potassium hydroxide and histopathological examinations demonstrating fungus invasion of the nail plate are usually required to confirm disease etiology (8).

Among yeasts, Candida albicans and Candida parapsilosis are most commonly implicated in onychomycosis (4, 5). Candida species have a high incidence in fingernail infections, present in as many as 75% of cases, and are more prevalent than dermatophytes (4). In contrast, the incidence of yeasts in toenail infections is much lower, approximately 2 to 10% of cases.

The incidence of nondermatophytic fungi, such as Scopulariopsis, Scytalidium, Acremonium, Fusarium, and Aspergillus, in onychomycotic nails is lower, 2 to 21% of cases (5, 6). Infections attributed to nondermatophytes are estimated to be 2 to 6% of cases, although higher rates, 15%, have been reported (8, 9). Nondermatophyte onychomycosis is seen most frequently in the elderly, in patients with skin diseases that affect the nails, and in immunocompromised patients and is more frequent in toenails than in fingernails (6, 8).

Clinical management of onychomycosis includes prescription systemic and topical antifungal treatments. Currently used antifungals include terbinafine (an allylamine), amorolfine (a morpholine), itraconazole (a triazole), and ciclopirox (a hydroxypiridone). Ciclopirox, itraconazole, and terbinafine are approved in the United States and around the world for onychomycosis treatment, while amorolfine and fluconazole are approved in Europe.

In spite of the availability of several therapeutic options, onychomycosis remains difficult to treat, and new drugs with improved safety and efficacy are needed. Efinaconazole (also known as KP-103) is a novel triazole antifungal that inhibits lanosterol-14α demethylase and blocks fungal-membrane ergosterol biosynthesis, a mechanism of action consistent with other azole antifungals (Y. Tatsumi, M. Nagashima, T. Shibanushi, A. Iwata, Y. Kangawa, F. Inui, W. Jo Siu, R. Pillai, and Y. Nishiyama, unpublished data). Efinaconazole is active in vitro against dermatophytes, including Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton species, responsible for tinea unguium, tinea corporis, tinea pedis, and tinea capitis (10). It is also effective against C. albicans and other Candida species responsible for nail and skin candidiasis and Malassezia species responsible for tinea versicolor. Further, efinaconazole administered topically is effective in reducing the fungal burden in guinea pig models of tinea unguium and tinea pedis (11).

In this study, we aimed to characterize the in vitro antifungal activity of efinaconazole. We conducted a comprehensive assessment of efinaconazole's activity against recent clinical isolates recovered from onychomycosis patients. We further compared its activity to those of terbinafine, ciclopirox, itraconazole, and amorolfine in T. rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, and C. albicans isolates. In addition, we characterized efinaconazole's spectrum of activity against various pathogenic fungal species, many of which are associated with onychomycosis and other superficial mycoses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antifungal agents.

Efinaconazole was supplied by Kaken Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Kyoto, Japan). Efinaconazole, amorolfine (Tokyo Chemical Industry Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan; 3B Pharmachem International [Wuhan] Co. Ltd., Libertyville, IL), ciclopirox (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), itraconazole (Sigma-Aldrich), and terbinafine (Tokyo Chemical Industry Co. Ltd.) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to make 100× or 200× stock solutions. Stocks were freshly prepared before use or stored frozen until use.

Fungal isolates.

A total of 1,751 clinical isolates were used for in vitro susceptibility testing. One hundred and six T. mentagrophytes and 1,387 T. rubrum isolates were recovered from toenail onychomycosis patients in the United States, Canada, and Japan, and an additional 44 T. mentagrophytes clinical isolates from U.S. patients were obtained from the Fungus Testing Laboratory collection, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX. One hundred and five C. albicans clinical isolates recovered from skin, nails, and oral and vaginal mucosa were obtained from the Fungus Testing Laboratory collection. The T. mentagrophytes, T. rubrum, and C. albicans isolates were recovered between 2009 and 2011. One hundred and nine research repository isolates of other dermatophyte (Tricophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton), nondermathophyte (Acremonium, Fusarium, Paecilomyces, Pseudallescheria, Scopulariopsis, and Aspergillus), and other yeast (Candida, Trichosporon, and Cryptococcus) species were obtained from several Japanese bioresource centers and from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). They included a total of 33 species, with the number of isolates per species ranging from 1 to 13. The collection date for these isolates was not available. The reference strains T. mentagrophytes ATCC MYA-4439, T. rubrum ATCC MYA-4438, C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019, and Candida krusei ATCC 6258 were used for assay validation.

Fungal isolates post-efinaconazole therapy.

Thirteen T. rubrum clinical isolates from toenail onychomycosis patients treated topically with efinaconazole were tested for efinaconazole susceptibility in vitro. These isolates were obtained from two identical multicenter, multicountry, vehicle-controlled phase 3 clinical trials with topical 10% efinaconazole applied daily to toenails for 48 weeks. Isolates were recovered at the end of treatment (study week 48) and 4 weeks later (study week 52).

In vitro antifungal susceptibility.

Testing was conducted using the broth dilution MIC assay following the standard procedures described in the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) documents M38-A2 and M27-A3. Clinical isolates were tested against efinaconazole, amorolfine, ciclopirox, itraconazole, and terbinafine. Drug stock solutions (100× or 200×) in DMSO were serially diluted 1/2 in DMSO to obtain a range of 10 concentrations, which were further diluted 1/100 or 1/50 in RPMI medium. The final DMSO concentration was 0.5% or 1% in the drug microdilution plates. Concurrent DMSO vehicle control wells were included as 100% growth controls. The MIC was determined in fungal cultures at 96 h postinoculation for dermatophytes. For nondermatophytes, the MIC was determined at 48 h, except for Acremonium potronii and Scopulariopsis brumptii (7 days). For yeasts, the MIC was determined at 24 and 48 h, except for Cryptococcus neoformans (72 h). Reference strains were assayed concurrently on each test day, and drug MICs were compared to CLSI quality control ranges (when established).

Statistical analysis.

MIC data for each drug were log (base 2) transformed in Excel 2003 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) and compared using the repeat measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey's multiple-comparison tests (α = 0.05) in Prism version 5.04 (Graphpad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). For MICs with values above the highest concentration tested, the next higher multiple of two was used as the MIC in the statistical analysis. For MIC values equal to or below the lowest concentration, the lowest concentration tested was used. Correlation analysis between drug pair MICs was conducted with the Spearman correlation function in Prism (two-tailed; confidence interval [CI] = 95%).

RESULTS

Susceptibility pattern of efinaconazole against T. mentagrophytes and T. rubrum onychomycosis clinical isolates.

The in vitro susceptibility to efinaconazole was determined in recent clinical isolates of T. rubrum (n = 1,387) and T. mentagrophytes (n = 106) from onychomycosis patient toenails in the United States, Canada, and Japan. Control wells containing culture medium and DMSO vehicle alone showed normal dermatophyte growth with no apparent vehicle effect. Efinaconazole inhibited fungal growth at concentrations ranging from ≤0.002 to 0.06 μg/ml (Table 1), with most T. rubrum and T. mentagrophytes isolates inhibited at 0.008 and 0.015 μg/ml, respectively, based on the MIC90. The MICs of 58% of isolates were ≤0.002 μg/ml. Overall, efinaconazole activities against T. mentagrophytes and T. rubrum isolates were comparable. There were no differences in susceptibility patterns by geographical location; the MIC ranges, MIC50s, and MIC90s were comparable between the United States, Canada, and Japan. Reproducible MIC results were obtained for efinaconazole when using the reference strains T. mentagrophytes ATCC MYA-4439 and T. rubrum ATCC MYA-4438 in a series of more than 30 separate sets of assays conducted over 12 months (data not shown).

Table 1.

In vitro susceptibility pattern of efinaconazole in dermatophyte clinical isolates

| Geographical location (no. of isolates) | No. of isolates inhibited at concn (μg/ml)a: |

MIC (μg/ml) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤0.002 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.015 | 0.03 | 0.06 | Range | MIC50 | MIC90 | |

| T. mentagrophytes | |||||||||

| U.S. (39) | 5 | 4 | 17 | 12 | 0 | 1 | ≤0.002–0.06 | 0.008 | 0.015 |

| Canada (21) | 7 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 0 | ≤0.002–0.015 | 0.004 | 0.015 |

| Japan (46) | 27 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 1 | ≤0.002–0.06 | ≤0.002 | 0.008 |

| All (106)b | 39 | 18 | 29 | 18 | 0 | 2 | ≤0.002–0.06 | 0.004 | 0.015 |

| T. rubrum | |||||||||

| U.S. (963) | 588 | 228 | 119 | 25 | 3 | 0 | ≤0.002–0.03 | ≤0.002 | 0.008 |

| Canada (218) | 123 | 60 | 28 | 6 | 1 | 0 | ≤0.002–0.03 | ≤0.002 | 0.008 |

| Japan (206) | 122 | 40 | 34 | 9 | 1 | 0 | ≤0.002–0.03 | ≤0.002 | 0.008 |

| All (1,387)b | 833 | 328 | 181 | 40 | 5 | 0 | ≤0.002–0.03 | ≤0.002 | 0.008 |

The test concentration range was 0.002 to 1 μg/ml; all isolates were inhibited at concentrations of ≤0.06 μg/ml.

All includes United States, Canada, and Japan.

Susceptibility of T. rubrum isolates recovered from toenail onychomycosis patients treated topically with efinaconazole for 48 weeks.

In order to evaluate potential changes in fungal susceptibility to efinaconazole after prolonged treatment, the MICs of isolates from onychomycosis patients treated with efinaconazole were determined. A total of 13 T. rubrum isolates were tested, which were recovered from patient toenails following once daily topical application of efinaconazole for 48 weeks (immediately after treatment cessation and 4 weeks later). The efinaconazole MICs ranged from ≤0.002 to 0.015 μg/ml and were within the range for isolates from untreated patients. Ten of these 13 isolates had a corresponding isolate collected prior to treatment from the same patient toenail; the MICs of 6 increased minimally at posttreatment relative to screening (the greatest change was from ≤0.002 to 0.008 μg/ml), 1 decreased, and 3 did not change.

In vitro antifungal activities of efinaconazole and comparator antifungals against the dermatophytes T. rubrum and T. mentagrophytes.

The in vitro susceptibility to efinaconazole was compared to those to amorolfine, ciclopirox, itraconazole, and terbinafine in recent isolates of T. rubrum (n = 130) and T. mentagrophytes (n = 129), mostly recovered from onychomycosis patients. Due to the high number of isolates with efinaconazole MICs of ≤0.002 μg/ml in the large-scale evaluation of clinical isolates, as reported above, the test concentration range was decreased by two dilutions, and the lowest concentration was 0.0005 μg/ml.

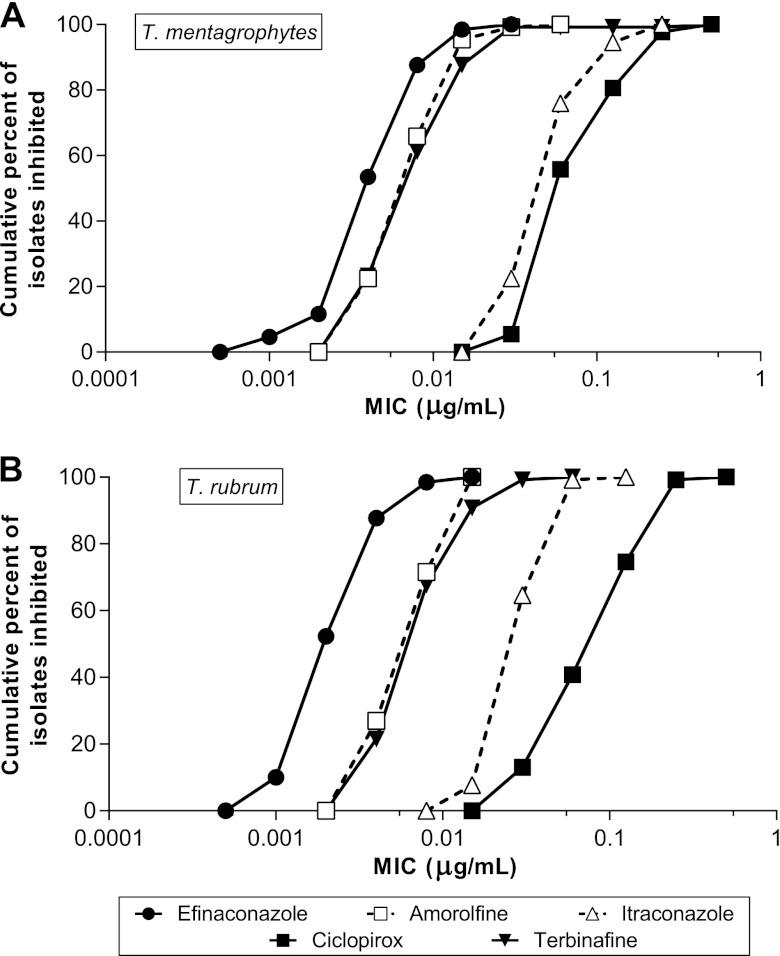

Efinaconazole inhibited fungal growth at concentrations ranging from 0.001 to 0.03 μg/ml (Table 2). Efinaconazole activities against T. mentagrophytes and T. rubrum isolates were comparable and higher than those of the comparator drugs (Fig. 1). In general, there was no species selectivity in the antifungal activities of efinaconazole and comparator drugs.

Table 2.

In vitro antifungal activities of efinaconazole and four reference drugs against common onychomycosis-causing fungi

| Organism (no. of isolates) | Test agent | MIC (μg/ml) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | MIC50 | MIC90 | Geometric mean | ||

| T. rubrum (130) | Efinaconazole | 0.001–0.015 | 0.002 | 0.008 | 0.003 |

| Terbinafine | 0.004–0.06 | 0.008 | 0.015 | 0.009 | |

| Ciclopirox | 0.03–0.5 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.101 | |

| Itraconazole | 0.015–0.125 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.037 | |

| Amorolfine | 0.004–0.015 | 0.008 | 0.015 | 0.008 | |

| T. mentagrophytes (129) | Efinaconazole | 0.001–0.03 | 0.004 | 0.015 | 0.005 |

| Terbinafine | 0.004–0.5 | 0.008 | 0.03 | 0.010 | |

| Ciclopirox | 0.03–0.5 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.094 | |

| Itraconazole | 0.03–0.25 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.063 | |

| Amorolfine | 0.004–0.06 | 0.008 | 0.015 | 0.009 | |

| C. albicans (105)a | Efinaconazole | ≤0.0005–>0.25 | 0.001 | 0.06 | 0.0029 |

| Terbinafine | 0.06–>16 | 1 | 4 | 1.409 | |

| Ciclopirox | 0.06–0.5 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.151 | |

| Itraconazole | ≤0.004–>2 | 0.008 | 0.125 | 0.014 | |

| Amorolfine | ≤0.03–0.5 | 0.03 | 0.125 | 0.041 | |

| C. albicans (105)b | Efinaconazole | ≤0.0005–>0.25 | 0.004 | >0.25 | 0.0079 |

| Terbinafine | 0.125–>16 | 4 | >16 | 6.873 | |

| Ciclopirox | 0.06–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.248 | |

| Itraconazole | ≤0.004–>2 | 0.015 | >2 | 0.039 | |

| Amorolfine | ≤0.03–8 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.091 | |

MIC endpoint determined at 24 h.

MIC endpoint determined at 48 h.

Fig 1.

Cumulative MIC frequency distribution of efinaconazole and comparator drugs against T. mentagrophytes (n = 129) (A) and T. rubrum (n = 130) (B).

The MIC50 and MIC90 of efinaconazole were comparable to those of amorolfine and terbinafine (within 4-fold) and 8- to 64-fold lower than those of ciclopirox and itraconazole (Table 2). The geometric mean MICs of efinaconazole in the two dermatophyte species were 2- to 34-fold lower than those of the comparator drugs. For both T. mentagrophytes and T. rubrum, the efinaconazole MIC values were significantly lower than those of the comparator drugs (P < 0.001).

In vitro antifungal activities of efinaconazole and comparator antifungals against C. albicans isolates.

In vitro susceptibility to efinaconazole was evaluated in recent C. albicans isolates (n = 105) recovered primarily from the skin, nails, or oral or vaginal mucosa of candidiasis patients. Because there is no CLSI-recommended reading time point for efinaconazole in C. albicans, the MICs for all test drugs were determined after 24 and 48 h of incubation. The MICs of efinaconazole, amorolfine, itraconazole, and terbinafine could not be determined for several isolates, as they were outside the tested concentration range. However, it was possible to calculate the MIC90 in most cases, as the number of affected isolates was ≤10% of the total tested. Efinaconazole inhibited C. albicans growth at concentrations ranging from ≤0.0005 to >0.25 μg/ml (Table 2), with 50% of isolates inhibited (MIC50) at 0.001 and 0.004 μg/ml at 24 and 48 h, respectively. The MIC50 and MIC90 for all drugs increased at 48 h relative to 24 h. Growth control wells showed normal C. albicans growth with no apparent vehicle effect.

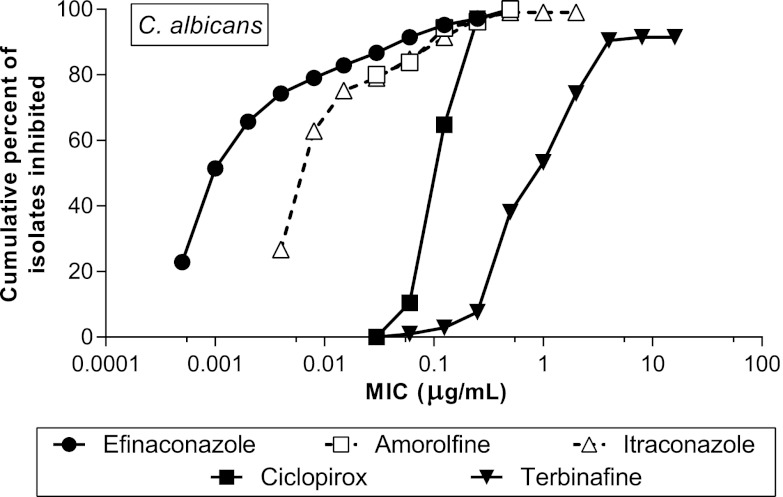

At 24 h, efinaconazole was more potent in inhibiting C. albicans growth than amorolfine, ciclopirox, itraconazole, and terbinafine. The higher potency of efinaconazole relative to the other drugs was particularly marked in the low and middle ranges of the susceptibility distribution spectrum (Fig. 2); the MIC50 of efinaconazole was 8- to 1,000-fold lower than those of the comparator drugs, while the MIC90 was 2- to 66-fold lower. At 48 h, efinaconazole was also more potent than the comparator drugs; the MIC50 of efinaconazole was 4- to 1,000-fold lower. However, a comparison could not be made based on the MIC90 because it was higher than the top concentrations tested for three drugs (Table 2).

Fig 2.

Cumulative MIC frequency distribution of efinaconazole and comparator drugs against C. albicans at 24 h (n = 105). Not all isolates were inhibited at the highest dose tested following treatment with efinaconazole, itraconazole, and terbinafine.

The efinaconazole MIC values were significantly lower than those of the comparator drugs at both 24 and 48 h (P < 0.001). As expected, terbinafine had the lowest activity in vitro among all test agents evaluated (i.e., the highest MICs) against C. albicans. Among the comparator drugs, terbinafine exhibited the greatest difference from efinaconazole, with a MIC50 and a MIC90 that were 1,000- and 66-fold higher, respectively.

We further compared the susceptibility patterns of efinaconazole and itraconazole at 48 h. The breakpoint for itraconazole resistance in C. albicans is >0.5 μg/ml, and a total of 15 isolates tested (14%) were considered resistant. In this case, the susceptibilities to the two drugs were well correlated (r = 0.85) (Table 3).

Table 3.

MIC analysis for efinaconazole and itraconazole against C. albicans isolatesa

| Itraconazole MIC (μg/ml) | No. of isolates with efinaconazole MIC (μg/ml): |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤0.0005 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.015 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.25 | >0.25 | Total | |

| ≤0.004 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 17 | |||||||

| 0.008 | 6 | 12 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 28 | ||||||

| 0.015 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 19 | |||||

| 0.03 | 3 | 1 | 4 | |||||||||

| 0.06 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||||||

| 0.125 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 8 | ||||||

| 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | ||||||||

| 0.5 | 4 | 2 | 6 | |||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 2 | 0 | |||||||||||

| >2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 9 | 14 | |||||||

| Total | 14 | 25 | 10 | 11 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 14 | 105 |

Spearman correlation coefficient (r), 0.85. Comparisons were made with MICs determined at 48 h.

In vitro antifungal activities against various fungal pathogens.

The spectrum of antifungal activity of efinaconazole was characterized in a panel of repository isolates, which included dermatophyte, nondermatophyte, and yeast species. Efinaconazole was active against all of the isolates tested, with most MICs at 1 μg/ml or lower (Table 4), and generally compared favorably with comparator drugs. Growth control wells showed normal fungal growth with no apparent vehicle effect.

Table 4.

In vitro antifungal activities of efinaconazole and four reference drugs against a variety of fungal speciesa

| Organism (no. of isolates) | MIC (μg/ml) [geometric mean (range)]b |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efinaconazole | Terbinafine | Ciclopirox | Itraconazole | Amorolfine | |

| Dermatophytes | |||||

| Trichophyton ajelloi (2) | 0.044 (0.031–0.063) | 0.046 (0.016–0.13) | 0.25 (0.25) | 0.35 (0.25–0.5) | 0.5 (0.25–1) |

| Trichophyton schoenleinii (1) | NC (0.0039) | NC (0.0039) | NC (0.25) | NC (0.13) | NC (0.016) |

| Trichophyton tonsurans (1) | NC (0.016) | NC (0.016) | NC (0.25) | NC (0.13) | NC (0.25) |

| Trichophyton verrucosum (1) | NC (0.0039) | NC (0.016) | NC (0.13) | NC (0.016) | NC (0.25) |

| Microsporum canis (2) | 0.18 (0.13–0.25) | 0.13 (0.063–025) | 0.25 (0.25) | 0.35 (0.25–0.5) | >4.0 (>4) |

| Microsporum cookei (1) | NC (0.5) | NC (0.13) | NC (0.25) | NC (0.5) | NC (0.5) |

| Microsporum gypseum (3) | 0.010 (0.0039–0.016) | 0.050 (0.031–0.063) | 0.31 (0.25–0.5) | 0.1 (0.031–0.25) | 0.08 (0.063–0.13) |

| Epidermophyton floccosum (3) | ≤0.005 (≤0.002–0.0078) | 0.039 (0.031–0.063) | 0.31 (0.25–0.5) | 0.08 (0.063–0.13) | 0.16 (0.13–0.25) |

| Yeasts | |||||

| Candida glabrata (7) | 0.026 (0.0039–0.13) | >8 (>8) | 0.13 (0.13) | 0.74 (0.25–2) | >4.9 (2–>8) |

| Candida krusei (10) | 0.024 (0.0078–0.063) | >8 (>8) | 0.21 (0.13–0.25) | 0.38 (0.13–0.5) | 0.27 (0.13–0.5) |

| Candida parapsilosis (13) | ≤0.0046 (≤0.002–0.016) | 0.28 (0.13–1) | 0.22 (0.13–0.5) | 0.13 (0.063–0.25) | 0.56 (0.13–4) |

| Candida tropicalis (10) | 0.014 (0.0078–0.063) | >8 (>8) | 0.5 (0.5) | 0.31 (0.063–0.5) | NC (≤0.016–>8) |

| Candida guilliermondii (1) | NC (0.016) | NC (1) | NC (0.25) | NC (0.13) | NC (0.25) |

| Candida kefyr (1) | NC (≤0.002) | NC (2) | NC (0.13) | NC (0.031) | 0.063 |

| Candida lusitaniae (1) | NC (0.0039) | NC (4) | NC (0.25) | NC (0.13) | 0.5 |

| Cryptococcus neoformans (5) | ≤0.0023 (0.002–0.0039) | 0.25 (0.063–0.5) | ≤0.031 (≤0.016–0.063) | 0.041 (0.031–0.063) | ≤0.064 (≤0.016–0.13) |

| Trichosporon asahii (3) | ≤0.005 (≤0.002–0.0078) | 0.63 (0.5–1) | 0.13 (0.13) | 0.1 (0.063–0.13) | 0.08 (0.063–0.13) |

| Trichosporon beigeleii (2) | 0.016 (0.0078–0.031) | 0.5 (0.5) | 0.18 (0.13–0.25) | 0.18 (0.13–0.25) | 0.35 (0.25–0.5) |

| Nondermatophytes | |||||

| Acremonium potronii (3) | 0.31 (0.25–0.5) | 0.25 (0.13–0.5) | 0.25 (0.13–0.5) | >2.5 (1–>4) | 0.26 (0.13–1) |

| Acremonium sclerotigenum (2) | 0.18 (0.13–0.25) | 0.09 (0.063–0.13) | 1.4 (1–2) | >4 (>4) | 1 (1) |

| Fusarium oxysporum (3) | 1 (0.5–2) | 2.5 (1–4) | 1 (1) | >4 (>4) | >4 (>4) |

| Fusarium solani (1) | NC (0.5) | NC (4) | NC (>4) | NC (>4) | NC (>4) |

| Paecilomyces variotii (1) | NC (0.0078) | NC (0.25) | NC (0.25) | NC (0.13) | NC (>4) |

| Paecilomyces lilacinus (3) | 0.031 (0.031) | 0.1 (0.063–0.13) | 4 (4) | 1.6 (1.0–4) | 0.25 (0.25) |

| Pseudallescheria boydii (1) | NC (0.063) | NC (>4) | NC (4) | NC (>4) | NC (4) |

| Scopulariopsis brevicaulis (4) | 0.25 (0.13–0.5) | 1 (0.5–2) | 0.59 (0.5–1) | >4 (>4) | 0.09 (0.063–0.13) |

| Scopulariopsis brumptii (1) | NC (0.13) | NC (1) | NC (0.5) | NC (>4) | NC (0.5) |

| Aspergillus fumigatus (4) | 0.089 (0.031–0.5) | 1.4 (1–2) | 0.42 (0.25–0.5) | 0.5 (0.25–1) | >4 (>4) |

| Aspergillus flavus (4) | 0.11 (0.063–0.13) | 0.11 (0.063–0.5) | >3.4 (2–>4) | 0.18 (0.13–0.25) | >4 (>4) |

| Aspergillus niger (3) | 0.2 (0.13–0.25) | 0.16 (0.13–0.25) | 0.63 (0.5–1) | 0.63 (0.5–1) | >4 (>4) |

| Aspergillus sydowii (4) | 0.037 (0.0078–0.25) | 0.076 (0.063–0.13) | 0.59 (0.5–1) | >0.3 (0.063–>4) | >4 (>4) |

| Aspergillus terreus (4) | 0.09 (0.063∼0.13) | 0.13 (0.13) | 0.5 (0.25–1) | 0.21 (0.13–0.25) | >4 (>4) |

| Aspergillus nidulans (4) | 0.0078 (0.0078) | 0.063 (0.063) | 1 (0.5–4) | 0.089 (0.063–0.25) | >4 (>4) |

ATCC or Japanese repository isolates.

MIC geometric means are calculated for species with at least 2 isolates tested; NC, not calculated. MIC is presented instead of MIC range for species with one isolate tested.

Against dermatophytes (excluding T. mentagrophytes and T. rubrum), the MIC range for efinaconazole was ≤0.002 to 0.5 μg/ml. Efinaconazole MICs were generally similar to those of terbinafine and lower than those of amorolfine, ciclopirox, and itraconazole.

Against Candida species (excluding C. albicans), the MIC range for efinaconazole was ≤0.002 to 0.13 μg/ml. Efinaconazole inhibited the growth of Cryptococcus and Trichosporon species, with MICs ranging from ≤0.002 to 0.031 μg/ml. The MIC and MIC range of efinaconazole were at least 1 order of magnitude lower than those of terbinafine, ciclopirox, itraconazole, and amorolfine.

The MICs of efinaconazole against nondermatophyte species ranged from 0.0078 to 2 μg/ml. In comparison, the MICs of amorolfine, ciclopirox, terbinafine, and itraconazole ranged from 0.063 to >4 μg/ml. Based on the geometric mean MIC or MIC values, the antifungal activities of efinaconazole against these nondermatophyte molds were similar to or greater than those of the comparators.

DISCUSSION

Efinaconazole is a novel triazole antifungal agent. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the antifungal activities of efinaconazole against T. rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, and C. albicans, pathogens most commonly associated with onychomycosis. We also compared its activity to those of current topical and oral treatments for onychomycosis, including terbinafine, ciclopirox, itraconazole, and amorolfine.

Dermatophytes, primarily T. mentagrophytes and T. rubrum, are responsible for almost 90% of toenail onychomycosis infections. We conducted a large in vitro survey that included 1,493 recent clinical isolates of these two species recovered from toenail onychomycosis patients. Efinaconazole showed potent antifungal activity within a narrow concentration range (i.e., 0.001 to 0.06 μg/ml), with no geographical differences in susceptibility patterns between North American (United States and Canada) and Japanese isolates.

The MICs obtained in the current study were approximately 13 to 63 times lower than previously reported efinaconazole MICs in Japanese T. rubrum and T. mentagrophytes clinical isolates (10). The higher MICs reported previously may be due to a different methodology, which included use of Sabouraud dextrose broth (pH 5.6) and a later time point for MIC reading (7 days). In contrast, we determined the MIC in accordance with the current CLSI standard, using RPMI 1640 medium (pH 7.0) and endpoint reading at 96 h (4 days).

Based on MIC50 and MIC90 data, efinaconazole is at least as effective as the currently available antifungal agents used to treat onychomycosis and, in many cases, more potent. Against T. rubrum and T. mentagrophytes, efinaconazole has activities (1- to 4-fold) comparable to those of amorolfine and terbinafine and higher (8- to 64-fold) than those of ciclopirox and itraconazole. Based on MIC geometric means, efinaconazole was more potent than all comparator drugs.

Onychomycotic infections can also be caused by yeasts, generally C. albicans. Efinaconazole was active against recent C. albicans isolates, with MIC50s of 0.001 μg/ml (24 h) and 0.004 μg/ml (48 h). Furthermore, efinaconazole was more potent in inhibiting C. albicans growth than terbinafine, ciclopirox, itraconazole, and amorolfine. These results were obtained in topical isolates, mostly from vaginal and oral candidiasis, and the patients may have been treated with topical or systemic azole antifungals. For all drugs, the MIC range of C. albicans isolates was broader than for T. rubrum and T. mentagrophytes. A broad susceptibility range of C. albicans has also been reported for terbinafine and fluconazole in cutaneous isolates (12). The relatively extensive usage of existing antifungals in candidiasis possibly affected the sensitivity of isolates against the drugs tested, including efinaconazole.

We further characterized efinaconazole's antifungal spectrum of activity in 33 other fungal species. Overall, efinaconazole was active against all species tested, with MIC ranges of ≤0.002 to 0.5 μg/ml for other dermatophytes, ≤0.002 to 0.13 μg/ml for other yeasts, and 0.0078 to 2 μg/ml for nondermatophyte molds. Efinaconazole was generally more active against these molds than amorolfine, ciclopirox, itraconazole, and terbinafine, and its antifungal spectrum was broader than that of the existing drugs.

Although efinaconazole and terbinafine had comparable antifungal activities against dermatophytes and nondermatophytes, their activities were markedly different against Candida spp. Efinaconazole was significantly more potent than terbinafine, with MICs mostly <0.1 μg/ml and ≥1 μg/ml, respectively. Terbinafine was previously found to be inactive against Candida glabrata, C. krusei, and Candida tropicalis when tested at concentrations as high as 128 μg/ml. In contrast, efinaconazole has potent antifungal activity against these species, as well as other yeast in which terbinafine is also active.

In vitro studies have reported that some fungal clinical isolates, including Candida species, with reduced susceptibility to one azole antifungal agent may also be less susceptible to other azoles (13). The MICs of efinaconazole against C. albicans correlated well with those of itraconazole, another azole, although efinaconazole showed 1 order of magnitude higher potency. There are no breakpoints established for efinaconazole. However, there were 15 resistant C. albicans isolates tested based on a resistant breakpoint of >0.5 μg/ml, 12 of which were also the least susceptible (MIC ≥ 0.25 μg/ml) to efinaconazole (Table 3). Thus, it appears that the mechanisms of resistance common to azoles, as discussed in the literature, may also affect fungal susceptibility to efinaconazole.

There are few reports of drug resistance in dermatophytes. In our large-scale susceptibility investigation, efinaconazole demonstrated potent antifungal activity, with a narrow range of MICs against T. rubrum and T. mentagrophytes. Very few isolates were recovered after 48 weeks with daily topical treatment with efinaconazole, and there were no apparent changes in susceptibility compared to isolates from untreated patients. There were no significant increases in MICs in T. rubrum and T. mentagrophytes after serial subculturing in vitro with efinaconazole (A. Iwata, Y. Watanabe, M. Nagashima, K. Sugiura, R. Pillai, and Y. Tatsumi, unpublished data). Although data are limited, these results suggest a low potential for dermatophytes to develop resistance to efinaconazole in a clinical setting. However, the possibility of emergence of efinaconazole-resistant strains over time, after widespread clinical use, cannot be excluded.

Epidermophyton, Microsporum, Acremonium, Fusarium, Scopulariopsis, Scytalidium, Aspergillus, and Candida are commonly associated with onychomycosis, as they have been isolated from onychomycotic nails (4–6). Several studies have confirmed the role of these organisms as causative pathogens, although their relative incidence compared to Trichophyton infections is low (14–16). Further, mixed fungal infections occur in approximately one-fifth of onychomycosis cases and may be a reason for clinical treatment failure (17, 18). Potent antifungal agents with broad spectra of activity may be advantageous in onychomycosis therapy. Our results show that efinaconazole is active not only against the most common onychomycosis pathogens, but also against other pathogenic/colonizing species. Because many infections are of mixed-pathogen nature, the broad spectrum of activity of efinaconazole is expected to be useful in onychomycosis treatment.

In vitro evaluation of antifungal activity enables comparison between different antimycotic agents and may clarify the reasons for lack of clinical response and assist the clinician in therapy selection (19). Onychomycosis MIC breakpoints have not been established for any of the agents that we tested, and therefore, it is unclear whether in vitro activity is predictive of clinical outcome. Drug delivery to the nail site of action at effective concentrations represents the main difficulty in developing topical antifungals. Thus, excellent in vitro activity against fungal pathogens may not necessarily translate well into high clinical cure rates in onychomycosis. For example, ciclopirox nail lacquer has demonstrated only modest efficacy in onychomycosis, with reported complete cure rates of 5.5 to 8.5% (20). Other topical agents, such as amorolfine nail lacquer and terbinafine nail solution (under development), have been shown to have minimal efficacy (<2% complete cure rates), even though both are reasonably potent antifungals (21). Our in vitro data on efinaconazole are encouraging, and the unique properties of the molecule and its topical formulation have led to an extensive clinical program to evaluate its efficacy in onychomycosis (22).

In conclusion, efinaconazole has potent in vitro antifungal activity against T. rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, and C. albicans. The activity of efinaconazole is at least comparable to and in many cases is more potent than current treatments used in onychomycosis. The relevance of these in vitro findings to clinical efficacy has not been established. Furthermore, efinaconazole has a broad spectrum of activity against fungi associated with onychomycosis and other mycoses and may have additional therapeutic utility.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Linda Mutter and Brian Bulley for discussions and review of the manuscript.

W.J.J.S. and R.P. are employees of and stockholders in Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America LLC. H.S., T.N., D.S., and Y.T. are employees of and stockholders in Kaken Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 January 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Elewski BE. 2000. Onychomycosis. Treatment, quality of life, and economic issues. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 1:19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gupta AK, Jain HC, Lynde CW, Macdonald P, Cooper EA, Summerbell RC. 2000. Prevalence and epidemiology of onychomycosis in patients visiting physicians' offices: a multicenter Canadian survey of 15,000 patients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 43:244–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Faergemann J, Baran R. 2003. Epidemiology, clinical presentation and diagnosis of onychomycosis. Br. J. Dermatol. 149:1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Foster KW, Ghannoum MA, Elewski BE. 2004. Epidemiologic surveillance of cutaneous fungal infection in the United States from 1999 to 2002. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 50:748–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ghannoum MA, Hajjeh RA, Scher R, Konnikov N, Gupta AK, Summerbell R, Sullivan S, Daniel R, Krusinski P, Fleckman P, Rich P, Odom R, Aly R, Pariser D, Zaiac M, Rebell G, Lesher J, Gerlach B, Ponce-De-Leon GF, Ghannoum A, Warner J, Isham N, Elewski B. 2000. A large-scale North American study of fungal isolates from nails: the frequency of onychomycosis, fungal distribution, and antifungal susceptibility patterns. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 43:641–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kaur R, Kashyap B, Bhalla P. 2008. Onychomycosis—epidemiology, diagnosis and management. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 26:108–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ellis DH, Marley JE, Watson AB, Williams TG. 1997. Significance of non-dermatophyte moulds and yeasts in onychomycosis. Dermatology 194(Suppl. 1):40–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Greer DL. 1995. Evolving role of nondermatophytes in onychomycosis. Int. J. Dermatol. 34:521–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Garcia-Martos P, Dominguez I, Marin P, Linares M, Mira J, Calap J. 2000. Onychomycoses caused by non-dermatophytic filamentous fungi in Cadiz. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 18:319–324 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tatsumi Y, Yokoo M, Arika T, Yamaguchi H. 2001. In vitro antifungal activity of KP-103, a novel triazole derivative, and its therapeutic efficacy against experimental plantar tinea pedis and cutaneous candidiasis in guinea pigs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1493–1499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tatsumi Y, Yokoo M, Senda H, Kakehi K. 2002. Therapeutic efficacy of topically applied KP-103 against experimental tinea unguium in guinea pigs in comparison with amorolfine and terbinafine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3797–3801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ryder NS, Wagner S, Leitner I. 1998. In vitro activities of terbinafine against cutaneous isolates of Candida albicans and other pathogenic yeasts. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1057–1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johnson E, Espinel-Ingroff A, Szekely A, Hockey H, Troke P. 2008. Activity of voriconazole, itraconazole, fluconazole and amphotericin B in vitro against 1763 yeasts from 472 patients in the voriconazole phase III clinical studies. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 32:511–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Lorenzi S. 2000. Onychomycosis caused by nondermatophytic molds: clinical features and response to treatment of 59 cases. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 42:217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Meireles TE, Rocha MF, Brilhante RS, de Cordeiro RA, Sidrim JJ. 2008. Successive mycological nail tests for onychomycosis: a strategy to improve diagnosis efficiency. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 12:333–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moreno G, Arenas R. 2010. Other fungi causing onychomycosis. Clin. Dermatol. 28:160–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Finch JJ, Warshaw EM. 2007. Toenail onychomycosis: current and future treatment options. Dermatol. Ther. 20:31–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Scher RK, Baran R. 2003. Onychomycosis in clinical practice: factors contributing to recurrence. Br. J. Dermatol. 149(Suppl. 65):5–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gupta A, Kohli Y. 2003. In vitro susceptibility testing of ciclopirox, terbinafine, ketoconazole and itraconazole against dermatophytes and nondermatophytes, and in vitro evaluation of combination antifungal activity. Br. J. Dermatol. 149:296–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gupta AK, Fleckman P, Baran R. 2000. Ciclopirox nail lacquer topical solution 8% in the treatment of toenail onychomycosis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 43:S70–S80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Elewski BE, Ghannoum MA, Mayser P, Gupta AK, Korting HC, Shouey RJ, Baker DR, Rich PA, Ling M, Hugot S, Damaj B, Nyirady J, Thangavelu K, Notter M, Parneix-Spake A, Sigurgeirsson B. 2011. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of topical terbinafine nail solution in patients with mild-to-moderate toenail onychomycosis: results from three randomized studies using double-blind vehicle-controlled and open-label active-controlled designs. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. [Epub ahead of print.] doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04373.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Elewski BE, Rich P, Pollak R, Pariser DM, Watanabe S, Senda H, Ieda C, Smith K, Pillai R, Ramakrishna T, Olin JT. 2012. Efinaconazole 10% solution in the treatment of toenail onychomycosis: two phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind studies. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. [Epub ahead of print.] doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]