Abstract

Neonates and juvenile ruminants are very susceptible to paratuberculosis infection. This is likely due to a high degree of exposure from their dams and an immature immune system. To test the influence of age on vaccine-induced responses, a cocktail of recombinant Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis proteins (MAP0217, MAP1508, MAP3701c, MAP3783, and MAP1609c/Ag85B) was formulated in a cationic liposome adjuvant (CAF01) and used to vaccinate animals of different ages. Male jersey calves were divided into three groups that were vaccinated at 2, 8, or 16 weeks of age and boosted twice at weeks 4 and 12 relative to the first vaccination. Vaccine-induced immune responses, the gamma interferon (IFN-γ) cytokine secretion and antibody responses, were followed for 20 weeks. In general, the specific responses were significantly elevated in all three vaccination groups after the first booster vaccination with no or only a minor effect from the second booster. However, significant differences were observed in the immunogenicity levels of the different proteins, and it appears that the older age group produced a more consistent IFN-γ response. In contrast, the humoral immune response is seemingly independent of vaccination age as we found no difference in the IgG1 responses when we compared the three vaccination groups. Combined, our results suggest that an appropriate age of vaccination should be considered in vaccination protocols and that there is a possible interference of vaccine-induced immune responses with weaning (week 8).

INTRODUCTION

Paratuberculosis is a chronic nontreatable granulomatous enteritis affecting all domestic and nondomestic ruminants and some nonruminants worldwide. It is an economically significant and widespread disease of the ruminants caused by Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Neonates and juvenile animals are most susceptible to infection, which progresses through subclinical, clinical, and advanced clinical disease stages (1, 2).

Currently available vaccines against M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis consist of killed or attenuated M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis in an oil adjuvant, which has been reported to provide partial protection through delayed fecal shedding and a reduction in the number of clinically affected animals (3, 4, 40). Whole-cell-based vaccines, however, induce the production of antibodies and a sensitization to delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH), making it impossible to differentially diagnose naturally infected from vaccinated animals. Vaccination against M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis also interferes with the diagnosis and surveillance of bovine tuberculosis due to false-positive skin test results (5). Moreover, whole-cell-based live vaccines suffer from a lack of characterization, localized prolonged swelling, and granuloma formation at the site of injection as well as risk of accidental self-inoculation among veterinarians while they are vaccinating animals (6–8).

Subunit vaccination with identified protective protein antigens in combination with an adjuvant inducing strong Th1-type immune responses could be an ideal strategy to surmount the limitations associated with whole-cell-based vaccines (9, 10). Recently, paratuberculosis experimental vaccines based on recombinant proteins expressing mycobacterial antigens (4, 11–14), DNA vaccines (14), and expression library immunizations (15) have been found to induce partial protection against experimental infection with M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Immaturity of the neonatal immune system contributes to an increased susceptibility of the young animal to infectious disease and may limit its capacity to develop a protective response to vaccination (16). Cattle usually become infected with M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis as calves, either through in utero transmission or as neonates via ingestion of fecal material, milk, or colostrum containing M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis organisms (17–19). Newborns have a tendency to exhibit a Th2 profile (20), and paratuberculosis infection is characterized by a distinct Th1 response (21). If calf susceptibility to M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis infection is related to maturation of the immune system, the immune response to an M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis vaccine may also be influenced by the age of vaccination. Evaluating the appropriate age of the animals for vaccination against M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis is therefore important in order to generate a high frequency of antigen-specific T cells with more rapid effector functions. We hypothesized that age of vaccination influences the quality of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis vaccine-induced T-cell responses. In order to substantiate this hypothesis, we vaccinated calves with well-defined M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis recombinant proteins at 2, 8, or 16 weeks of age and followed this with two booster rounds 4 and 12 weeks after the first vaccination. Vaccine-induced gamma interferon (IFN-γ) release and antibody responses were analyzed in individual animals to assess the immunogenicity of the vaccine. The upregulation of these immune responses was prospectively correlated with the ages of the calves.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

A total of 27 male jersey calves were used in the present study. The animals were obtained at the age of 2 weeks from a farm which, by the Danish paratuberculosis surveillance program, had a true prevalence equal to or close to zero at all milk antibody samplings from September 2006 to January 2011 (22). Animals were housed and raised under appropriate biological containment facilities (biosafety level 2 [BSL-2]) in a community pen with straw bedding. Calves were fed a commercial milk replacer (DLG, Denmark) and Green Start (DLG, Denmark) for the first 2 months twice a day. At 8 weeks of age, calves were weaned and fed pellets and hay ad libitum for the remainder of the study period. Calves had access to water ad libitum, and bedding was changed every day. Calves were checked daily for general health.

The use of animals described in this experiment was approved by the Danish National Experiments Inspectorate, and the experiment was carried out in compliance with their regulations and policies.

Antigens.

Antigens in the vaccine are detailed in Table 1. They were selected based on their immunogenicity as studied in naturally infected heifers and represent one protein from each of the secreted proteins (MAP0217), latency proteins (MAP3701c), and ESAT-6 family member proteins (MAP1508) along with a hypothetical protein (MAP3783), as reported earlier (22). MAP1609c (antigen Ag85B) was included as a positive-control antigen based on earlier studies reporting significant IFN-γ responses in cattle and mice to the MAP1609c (Ag85B) of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis (12, 13). All antigens were produced in Escherichia coli and purified by metal affinity and anion columns as previously described (22). The protein concentration of the final products was measured by a NanoOrange protein quantification kit (Invitrogen).

Table 1.

Details of antigens used in the study

| Antigen | Homology (%) in: |

Protein size (aa)a | Product of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. avium subsp. avium | M. bovis | |||

| MAP0217 | 99 | 83 | 300 | LipW secreted protein |

| MAP1609c | 99 | 85 | 330 | Secreted antigen 85B (Ag85B) |

| MAP1508 | 100 | 87 | 98 | Hypothetical ESAT-6-like protein EsxK |

| MAP3701c | 100 | 71 | 146 | Heat shock protein 20 (latency protein) |

| MAP3783 | 100 | 84 | 97 | Hypothetical ESAT-6-like protein EsxG |

aa, amino acids.

Experimental design.

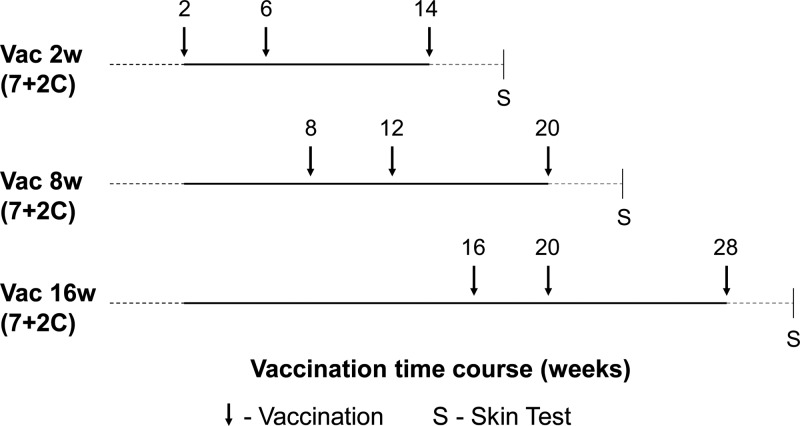

Calves were distributed into three groups, Vac2w, Vac8w, and Vac16w, with nine calves in each group. Each group was comprised of seven calves that received vaccine (vaccine calves) and two randomly assigned adjuvant controls. Calves were born over a period of 4 months and assigned into groups as they were born; i.e., group Vac16w includes the nine oldest animals followed by groups Vac8w and Vac2w. All vaccine calves in the three groups received 100 μg each of MAP0217, MAP1508, MAP3701c, MAP3783, and MAP1609c (Ag85B) recombinant vaccine antigen formulated with the DDA/TDB (N,N′-dimethyl-N,N′-dioctadecylammonium/α,α′-trehalose 6,6′-dibeheneate; 2,500 μg/500 μg) (CAF01) adjuvant (23). After the vaccine antigens were mixed, they were allowed to adsorb to the adjuvant CAF01 for 1 h at room temperature (RT) before injection. Controls received the adjuvant only, along with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Vaccinations were performed through the subcutaneous route in the right midneck region 7 cm ahead of the prescapular lymph node. The ages at the first vaccinations in the groups Vac2w, Vac8w, and Vac16w were 2, 8, and 16 weeks, respectively. All vaccine calves were vaccinated three times, with revaccinations at weeks 4 and 12 after the first vaccination (Fig. 1). Blood samples were collected every 2 weeks throughout the experiment. Heparinized samples were used for whole-blood IFN-γ assays, and serum samples were taken for serological analysis.

Fig 1.

Experimental design. Within each age group, seven animals were vaccinated against M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis and two calves received the CAF01 adjuvant only (7 + 2C).

IFN-γ assay.

Heparinized whole-blood samples were collected by the Vacutainer system. Whole blood (0.5 ml) was stimulated in 48-well culture plates (Greiner Bio-One, Heidelberg, Germany) with previously added purified protein derivatives of Johnin (PPDj), bovine (PPDb), and avian (PPDa) (a kind gift from James McNair, Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute [AFBI], Belfast, Ireland), each of the five recombinant M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis vaccine antigens, PBS (nil antigen), and positive-control stimulation with phytohemagglutinin (PHA; Sigma) or the superantigen Staphylococcus enterotoxin B (SEB; Sigma) (50 μl volume). All M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis antigens, PPDb, PPDa, and SEB were added to a final concentration of 1 μg/ml, while PHA and PPDj were added to final concentrations of 5 μg/ml and 10 μg/ml, respectively. Whole-blood cultures were incubated for 18 to 20 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 in air. Following overnight incubation, 55 μl of heparin solution (10 IU/ml in blood) was added to avoid clots in the supernatant after freezing. Plates were then centrifuged, and approximately 0.35 ml of supernatant was collected into 96-well 1-ml polypropylene storage plates (Greiner Bio-One, Heidelberg, Germany) and frozen at −20°C until analysis.

The antigen-specific IFN-γ secretion in supernatants was determined by use of an in-house monoclonal sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described earlier (24). The levels of IFN-γ (pg/ml) were calculated using linear regression on log-log-transformed readings from the 2-fold dilution series of a reference plasma standard with predetermined IFN-γ concentration. The IFN-γ response to PBS was subtracted from the IFN-γ response to each of the five recombinant M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis antigens among all the calves, and the result was defined as the antigen-specific IFN-γ response.

Antigen-specific serum IgG1 ELISA.

An in-house developed and optimized indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was applied for the demonstration of serum IgG1 antibody responses against the five vaccine recombinant proteins throughout the study. Serum IgG2 levels were also measured but were found to be too weak for any useful interpretation and thus are not discussed further. Briefly, microtiter plates (Maxisorp; Nunc A/S, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated overnight with 100 μl of 1 μg/ml of each of the five M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis antigens in sodium carbonate buffer except for MAP3701c, for which 0.2 μg of coating concentration was used. On the next day, plates were blocked using 200 μl of PBS with 0.05% Tween 20 and 1% bovine serum albumin (PBS-T-BSA). The plates were then washed with PBS with 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T), and serum at a final dilution of 1:40 in PBS-T-BSA was added to test wells in duplicate and incubated at RT in a shaking incubator for 1 h. To allow for plate-to-plate calibration, positive- and negative-control (PosC and NegC, respectively) sera were added to test wells in triplicate and along with blank (PBS-T-BSA) wells included on each plate. PosC serum was the serum from a vaccinated calf with consistently higher antibody responses against all vaccine antigens collected at 4 weeks after the second vaccination (V2) and at 2 and 4 weeks after the third vaccination (V3), with responses following an exponential curve. NegC serum was the serum from the same calf on the day of vaccination (day 0). The plates were washed with PBS-T buffer and incubated with 100 μl of a 1:500 dilution of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated mouse anti-bovine IgG1 (clone IL-A60; AbD Serotec) for 1 h at room temperature. After samples were washed with PBS-T buffer, substrate (1,2-orthophenyl-diamine [OPD], H2O2) was added to each test well, and the absorbance was read at 493 nm with a 649-nm reference subtraction. The mean optical density (OD) value for each test serum (ODSample) was calibrated according to the OD values of the control sera on the respective plate, and the result is presented as the calibrated OD (ODCal), calculated as follows: ODCal = [(ODSample − ODNegC) × (ODPnorm − ODNnorm)/(ODPosC − ODNegC)] + ODNnorm, where ODSample is the sample OD, ODPosC is the mean of the positive controls on the plate (mean OD of three sera all in triplicate), ODNegC is the mean of the negative controls on the plate (mean OD of day 0 sera in triplicate), ODPnorm is the mean over all runs of positive controls, and ODNnorm is the mean over all runs of negative controls.

Tuberculin skin test.

To evaluate the development of the cell-mediated immune (CMI) response and to negate the possibility of any cross-reactivity with surveillance testing for bovine tuberculosis, tuberculin skin testing was performed 6 weeks after the third immunization. The single comparative intradermal tuberculin test with avian and bovine purified protein derivative (PPDa and PPDb, respectively; 2,000 IU each) was performed by intradermal inoculation of 0.1 ml of PPDa and PPDb (a kind gift from James McNair, AFBI, Belfast, Ireland), and reactions were read 72 h later. Results were recorded as the increase in skin thickness at 72 h compared to thickness before injection and interpreted according to a standard protocol (European Communities Commission regulation 141 number 1226/2002) (25). Reactions to each of the tuberculin's were interpreted as follows: a skin test reaction was considered positive when skin thickness increased 4 mm or more, inconclusive when there was an increase of more than 2 mm and less than 4 mm, and negative when the increase was not more than 2 mm.

Following the guideline to the official interpretation of the intradermal comparative cervical tuberculin test, an animal was scored positive if the increase in skin thickness at the bovine site of injection was more than 4 mm greater than at the avian site, inconclusive if the increase in skin thickness at the bovine site was 1 to 4 mm greater than the avian reaction, and negative if the increase in skin thickness at the bovine site of injection was less than or equal to the increase in the skin reaction at the avian site of injection.

Statistical analysis and interpretation.

For the statistical analyses of the antigen-specific immune responses, the adjuvant control animals were pooled into one group. In order to obtain a single value of the immune response following each vaccination, the mean of the IFN-γ values obtained 2 and 4 weeks after each vaccination was used. For each antigen, data were analyzed with a zero-inflated model due to the excess amount of data registered with a 0 measurement. The probability that an IFN-γ measurement was positive was modeled (model A) with a logistic regression model where vaccine group (Vac2w, Vac8w, Vac16w, or control) and vaccination number (1, 2, or 3) were entered as deterministic explanatory variables, while an animal effect was included as a random effect. In order to obtain normality distributions, the responses above 2 pg/ml were log transformed and modeled (model B) with a mixed linear model with the same set of explanatory variables, and the two models were combined into one zero-inflated model (model C). A statistically significant immunological response to the individual antigen was defined as a statistically significant effect in model C (P < 0.05). Tests were performed with the likelihood method, using the Wald test (26). For MAP3783, the number of positive values were so different between vaccinated and nonvaccinated animals that a logistic regression model (model A), and thus a zero-inflated model (model C), did not apply. Instead, a nonparametric Wilcoxon test (27) was used. This was modified to the Kruskal-Wallis rank test (27) when more than two groups were compared. For each antigen, the corresponding antibody responses were modeled with a model similar to model B. Log transformation of ODCal values was performed for all antibody responses except for antigen MAP0217, whose values were normally distributed. Identical analyses were also performed using only the results after the first two vaccinations to assess the immune response following a two-dose regimen. All analyses were carried out in Splus, version 6.1.

RESULTS

Observations following vaccination.

The animals were observed throughout the study for any visible effects postvaccination. However, no side effect, such as swelling or palpable growth, was observed following midneck subcutaneous inoculation of the recombinant proteins formulated in CAF01 adjuvant or from adjuvant alone.

Cell-mediated immune responses to vaccine antigens.

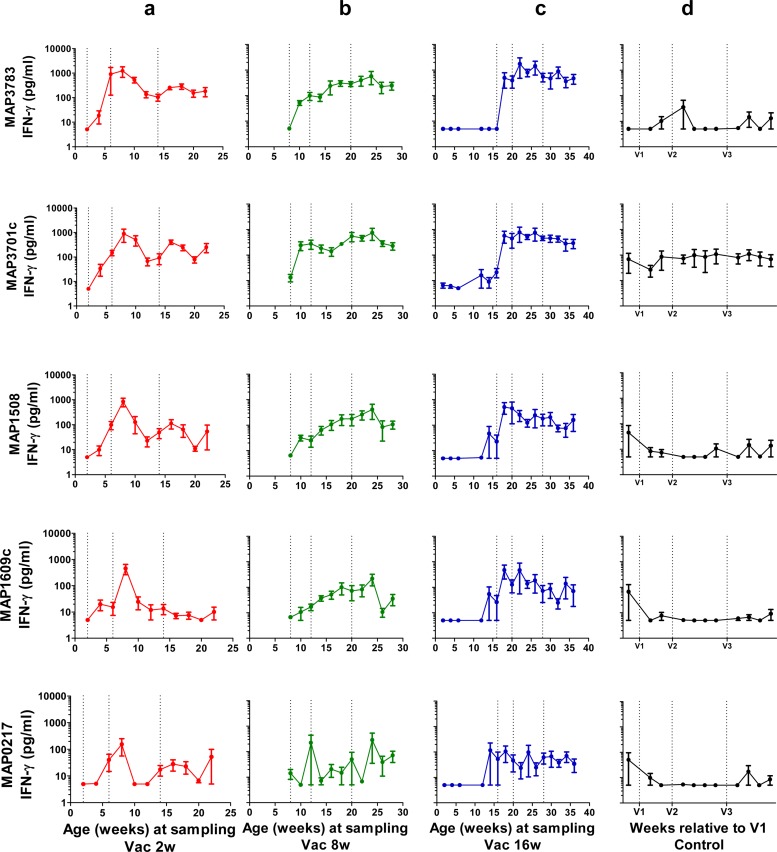

IFN-γ release toward each of the five antigens in the vaccine was followed in individual animals for 20 weeks (Fig. 2). In general, adjuvant control calves did not show antigen-specific responses to the vaccine antigens. However, the heat shock protein MAP3701c induced some IFN-γ responses in all adjuvant controls, and one calf responded to several of the other antigens at the first sampling prior to vaccination and at two samplings after the third vaccination.

Fig 2.

Antigen-specific IFN-γ responses in whole-blood cultures. Levels of IFN-γ released from whole-blood cultures stimulated with M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis recombinant antigens from calves in groups Vac2w, Vac8w, Vac16w and adjuvant controls following vaccinations, indicated as dotted lines. IFN-γ levels are expressed as mean values (± standard deviations) for plasma concentrations (pg/ml).

Statistically significant immune responses to all the vaccine antigens were observed following vaccination compared to levels in adjuvant controls (Table 2). The most significant responses were observed against MAP3783, MAP3701c, and MAP1508, while responses against MAP1609c (Ag85B) and, in particular, MAP0217 were less significant. Comparison of the response levels to different vaccine antigens confirmed that MAP3783 and MAP3701c induced significantly higher levels than other antigens. Vaccinated calves had IFN-γ levels below 50 pg/ml toward PPDj and PPDb antigens (data not shown).

Table 2.

P values and parameter estimates with the full zero-inflated model (IFN-γ)

| Antigen |

P value for the indicated group vs the control |

Vaccination response at three vaccinations |

P value for: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vac2w | Vac8w | Vac16w | Equal? | P value | Vaccination at all time points vs the control | Effect of age | |

| MAP0217 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.006** | Yes | 0.28 | 0.04* | 0.64 |

| MAP1609c | 0.30 | 0.003** | 0.005** | Yes | 0.15 | 0.005** | 0.68 |

| MAP1508 | 0.0009*** | 0.02* | <0.0001*** | Yes | 0.55 | <0.0001*** | 0.08 |

| MAP3701c | <0.0001***a | <0.0001***a | <0.0001***a | Yes | 0.70a | <0.0001*** | NA |

| MAP3783 | <0.0001***a | <0.0001***a | <0.0001***a | No | 0.02a | NAb | 0.13a |

All noncontrols were positive. For group Vac2w and Vac16w (MAP3783), the difference is significant with respect to the level of response (P = 0.03 and 0.01). For MAP3701c, all controls except three were positive, one at vaccination number 2 and two at vaccination number 3. For MAP3701c, the P value on time for the positive level is thus based on a very small sample, which makes it unreliable. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

NA, not applicable.

From the data shown in Fig. 2, it appears that immune responses in group Vac16w were more consistent than responses in younger age groups. However, no statistically significant differences in the immune responses between the three vaccine age groups were observed in the zero-inflated model, except for the response to MAP3783, where the Vac8w group responded with significantly lower levels. There was no statistically significant effect of the second vaccine booster on IFN-γ responses against vaccine antigens; however, for Vac2w and Vac8w animals, the response to MAP0217 was not statistically significant different from that of the controls after only two vaccinations.

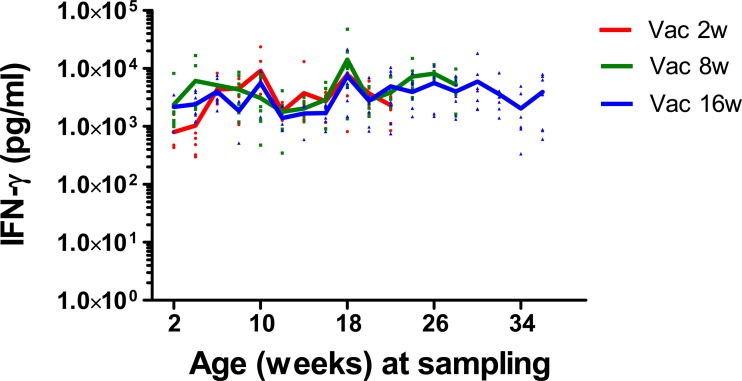

To investigate if the animal's age had an effect on the IFN-γ-producing capacity of blood cells, whole blood from all vaccinated calves was stimulated with SEB (a bacterial superantigen) at 2-week intervals throughout the study (Fig. 3) or PHA (phytohemagglutinin) at the time of the three vaccinations (data not shown). There was no effect of animal age on the IFN-γ-producing capacity.

Fig 3.

Secretion of IFN-γ in whole-blood cultures stimulated with SEB from the calves in the vaccinated groups Vac2w, Vac8w, and Vac16w. Individual IFN-γ levels are plotted against the age of the calves at the time of blood collection. Solid lines represent means for each age group.

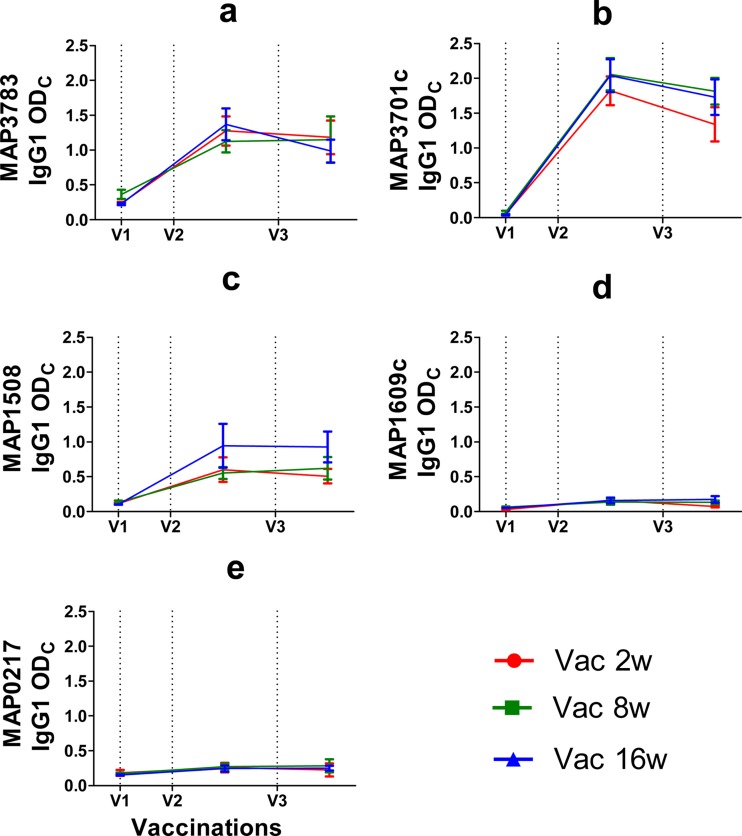

Antibody responses to vaccine proteins.

Antigen-specific IgG1 levels in serum from immunized calves were measured at first vaccination and at 4 weeks after the second and third vaccinations (Fig. 4). In general, the humoral responses emulate the IFN-γ responses. IgG1 responses were statistically significant for all the vaccine antigens in the vaccinated groups compared to the adjuvant controls. As seen with the IFN-γ responses, the most significant responses were observed against MAP3701c, MAP3783, and MAP1508, followed by MAP1609c (Ag85B) and MAP0217. However, no significant differences in the humoral immune responses were observed between the three vaccine groups.

Fig 4.

Seroreactivities to M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis recombinant proteins in calves in groups Vac2w, Vac8w, and Vac16w following vaccinations, indicated as dotted lines. Antigen-specific IgG1 antibody responses were measured by ELISA and are expressed as ODCal. Ages at first vaccination (V1) in group Vac2w, Vac8w, and Vac16w were 2, 8, and 16 weeks, respectively. Booster immunizations were given 4 (V2) and 12 weeks (V3) later. IgG1 antibody production in response to stimulation with M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis recombinant proteins MAP3783, MAP3701c, MAP1508, MAP1609c, and MAP0217 are shown. IgG1 levels are expressed as mean values (± standard deviations) for serum ODCal values.

The second vaccination strongly boosted the IgG1 antibody responses toward all five vaccine antigens, and these responses were statistically strongly significant (P < 0.0001); the third vaccination, however, did not increase the IgG1 levels above the level found after the second vaccination. Among the various recombinant antigens used, IgG1 response levels were the highest for MAP3701c (even though the coating concentration for this antigen was only 0.2 g/ml), followed by MAP3783, MAP1508, MAP1609c (Ag85B), and MAP0217. None of the prevaccination serum samples from any of the calves reacted with any of the M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis recombinant antigens used.

Skin test reactivity of the M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis-vaccinated and control calves.

The cross-reactivity with surveillance testing for bovine tuberculosis is a major drawback of available live or killed whole-cell M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis vaccines. Vaccinated calves were therefore evaluated for cross-reactivity using the standard tuberculin skin test 6 weeks after the third vaccination. All 27 calves were found to be negative by a comparative intradermal tuberculin test. The skin test results correlate with the low IFN-γ levels against PPDb and PPDa in the samples collected at that time point (data not shown). Interpretation of a single tuberculin test also showed a negative reading in all calves except for one with a 5.9-mm reaction to bovine tuberculin and 2.6-mm reaction to avian tuberculin.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the effect of age on vaccine-induced immune response following subunit vaccination using defined M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis recombinant proteins. Vaccinations in the three groups Vac2w, Vac8w, and Vac16w revealed three immune response profiles. After the first vaccination, there was an immediate rise in the IFN-γ levels against vaccine proteins in vaccinated animals compared to levels in the adjuvant control group. In mycobacterial infections including paratuberculosis, CD4 Th1-cell-mediated immunity is essential to keep the infection in check, and IFN-γ has a central role (28–31). Since IFN-γ is a quintessential cytokine in the Th1 response, it is supposedly an immune response variable and a correlate of vaccine-induced immune protection (21, 32). In our study, the vaccine proteins did induce a significant IFN-γ response relative to controls, indicating that CAF01-adjuvanted vaccination induces a measurable antigen-specific cell-mediated immune response in cattle. There was no age-related correlation between vaccinations and the immune responses to vaccine antigens, which were significant except for the response to MAP3783, where Vac8w had significantly lower response levels. One of the possible explanations for the low IFN-γ responses of the calves in the group Vac8w could be the change in the feeding schedule, with milk being replaced with pellets and hay at a time coinciding with the first vaccination. Thus, a change in the feeding pattern with resulting dietary stress (16, 33) could have modulated the IFN-γ responses following primary vaccination for the group Vac8w calves, and such dietary changes should be taken into account when vaccine experiments involving young animals are designed. In addition, the responsiveness of the young cattle in the IFN-γ assay to mycobacterial infections has also been associated with NK cells (34). In our study we did not look at IFN-γ production by NK cells and could not associate their role with any nonspecific IFN-γ production. However, one possible scenario could be that NK cells did not respond to the recombinant M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis proteins used in our study. IFN-γ responses following whole-blood stimulation with SEB and PHA revealed that all the animals in the three vaccine groups produced comparable levels of IFN-γ. Thus, there was no difference in the IFN-γ-producing capacity of the animals with age or in response to the vaccinations.

Analysis of the immune responses among the groups after only two vaccinations revealed a strikingly similar portrait as responses after three vaccinations. Notably, the third vaccination was not able to induce a statistically significant increase in the levels of IFN-γ against any of the recombinant vaccine antigens. Thus, it seems likely that a second booster dose for M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis vaccination is trivial at this time point and hence could be omitted.

Among the vaccine antigens used in this study, secreted proteins MAP0217 and MAP1609c (Ag85B) are expected to be highly immunogenic due to their extracellular environment and high likelihood of encountering immune cells (35, 36). However, we found that postvaccination immune responses of the animals with these antigens were weak compared to responses with the other recombinant proteins. Also the antibody responses corroborated this observation. This contrasts with previously published data which showed that recombinant Mycobacterium bovis Ag85B induces strong proliferative and ex vivo IFN-γ responses following natural and experimental infection in cattle and mice (13). Despite the fact that Ag85B induces an early immune response following infection, whether it plays a major role in the protection against M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis infection when used as a recombinant subunit vaccine is still to be confirmed.

The recombinant M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis antigens encoded by MAP3783, MAP3701c, and MAP1508 induced the most significant immune responses, with higher IFN-γ levels than the secreted proteins. MAP3783, a conserved hypothetical protein the function of which is yet unknown, produced sustained and average higher IFN-γ levels in the animals. MAP3701c is an immunogenic latent protein (heat shock protein) which is known to be expressed during the latent stage of M. tuberculosis infection and may contribute to the control of mycobacterial infection (37). The vaccinated animals in all three groups responded very well to MAP3701c antigen throughout the study period, supporting its role as a potential candidate in subunit vaccine strategy against M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis infection. Another protein, MAP1508, which is a hypothetical ESAT-6 like protein, was found to be comparatively weaker than MAP3783 and MAP3701c; however, the responses peaked after first booster in the youngest animal group.

Although vaccinated calves developed strong cell-mediated immune responses, their humoral responses characterized by IgG1 antibody levels were low but detectable. Postvaccination antibody levels were differentially elevated for MAP3701c, MAP3783, and MAP1508 compared to responses to other recombinant proteins in all three groups. Some recent studies have suggested that the age of the calf and ingestion of colostral antibodies interfere with the immune capacity of young calves to produce antigen-specific antibody responses, with little or no effect on cell-mediated immune responses (16, 38). However, in this study no significant differences in the humoral immune responses were observed between the vaccine groups. Despite the fact that humoral responses are not considered protective in M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis infection, the production of IgG1 antibody in response to recombinant M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis antigens is indicative of the role of vaccine-induced IFN-γ in the isotype switching from IgM to IgG (39).

Evaluation of the comparative skin test results revealed no cross-reaction with either M. bovis PPD or M. avium PPD tuberculins. Only one calf reacted to bovine PPD tuberculin. This is an important observation considering the fact that the currently available whole-cell M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis vaccines show cross-reaction with M. bovis PPD and thus pose a problem in the differentiation of vaccinated and naturally infected animals. The cross-reactivity of one of the calves to bovine PPD tuberculin in the skin test could not be explained, and the same calf reacted poorly to Ag85B in the whole-blood IFN-γ assay performed on the sample collected before the skin test. Ag85B is a major component of bovine PPD, and the gene encoding the Ag85B protein from M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis shares 85% sequence identity with M. bovis Ag85B at the protein level (22). Therefore, at the blood level there was no cross-reactivity between M. bovis and M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis for Ag85B.

In summary, we have shown enhanced cell-mediated and humoral immune responses after immunization of calves at different ages with recombinant M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis proteins, and we have shown that the age of vaccination of the calves has some correlation with the vaccine-induced immune response to selected M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis proteins. In particular, vaccination of the calves against M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis at the age of weaning could jeopardize the immune response, and vaccination of older calves appears to result in more sustained CMI responses. Also, vaccination followed by a single booster could be sufficient for the generation of an ample immune response and thus might circumvent the need for additional boosting of the immune response. We have provided supplementary evidence that vaccination of the calves using selected recombinant M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis proteins administered as in this study will not result in any side effects and interference with M. bovis diagnosis. Furthermore, it is interesting here in the context of vaccination that MAP3783, MAP3701c, and MAP1508 could elicit in calves immune responses which were statistically significant when these antigens were administered as recombinant proteins in CAF01 adjuvant. No live M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis experimental challenge was performed in this study as the main purpose was to characterize and compare antigen-specific adaptive immune responses in different age groups of calves using a cocktail of recombinant M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis proteins.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge especially Jeanne Toft Jakobsen and Vivi Andersen for their technical assistance and the staff of the Technical University of Denmark National Veterinary Institute animal facilities for care of the animals.

This work was supported by grant 274-08-0166 from the Danish Research Council for Technology and Production Sciences.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 6 February 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Larsen AB, Merkal RS, Cutlip RC. 1975. Age of cattle as related to resistance to infection with Mycobacterium paratuberculosis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 36: 255–257 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Whitlock RH, Buergelt C. 1996. Preclinical and clinical manifestations of paratuberculosis (including pathology). Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract. 12: 345–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rosseels V, Huygen K. 2008. Vaccination against paratuberculosis. Expert Rev. Vaccines 7: 817–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Uzonna JE, Chilton P, Whitlock RH, Habecker PL, Scott P, Sweeney RW. 2003. Efficacy of commercial and field-strain Mycobacterium paratuberculosis vaccinations with recombinant IL-12 in a bovine experimental infection model. Vaccine 21: 3101–3109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wentink GH, Bongers JH, Zeeuwen AA, Jaartsveld FH. 1994. Incidence of paratuberculosis after vaccination against M. paratuberculosis in two infected dairy herds. Zentralbl. Veterinarmed. B 41: 517–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kohler H, Gyra H, Zimmer K, Drager KG, Burkert B, Lemser B, Hausleithner D, Cubler K, Klawonn W, Hess RG. 2001. Immune reactions in cattle after immunization with a Mycobacterium paratuberculosis vaccine and implications for the diagnosis of M. paratuberculosis and M. bovis infections. J. Vet. Med. B Infect. Dis. Vet. Public Health 48: 185–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Langelaar M, Koets A, Muller K, van, Noordhuizen EWJ, Howard C, Hope J, Rutten V. 2002. Mycobacterium paratuberculosis heat shock protein 70 as a tool in control of paratuberculosis. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 87: 239–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patterson CJ, LaVenture M, Hurley SS, Davis JP. 1988. Accidental self-inoculation with Mycobacterium paratuberculosis bacterin (Johne's bacterin) by veterinarians in Wisconsin. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 192: 1197–1199 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kathaperumal K, Park SU, McDonough S, Stehman S, Akey B, Huntley J, Wong S, Chang CF, Chang YF. 2008. Vaccination with recombinant Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis proteins induces differential immune responses and protects calves against infection by oral challenge. Vaccine 26: 1652–1663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sable SB, Verma I, Khuller GK. 2005. Multicomponent antituberculous subunit vaccine based on immunodominant antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Vaccine 23: 4175–4184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Koets A, Hoek A, Langelaar M, Overdijk M, Santema W, Franken P, Eden W, Rutten V. 2006. Mycobacterial 70 kD heat-shock protein is an effective subunit vaccine against bovine paratuberculosis. Vaccine 24: 2550–2559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mullerad J, Michal I, Fishman Y, Hovav AH, Barletta RG, Bercovier H. 2002. The immunogenicity of Mycobacterium paratuberculosis 85B antigen. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 190: 179–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rosseels V, Marche S, Roupie V, Govaerts M, Godfroid J, Walravens K, Huygen K. 2006. Members of the 30- to 32-kilodalton mycolyl transferase family (Ag85) from culture filtrate of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis are immunodominant Th1-type antigens recognized early upon infection in mice and cattle. Infect. Immun. 74: 202–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sechi LA, Mara L, Cappai P, Frothingam R, Ortu S, Leoni A, Ahmed N, Zanetti S. 2006. Immunization with DNA vaccines encoding different mycobacterial antigens elicits a Th1 type immune response in lambs and protects against Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis infection. Vaccine 24: 229–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huntley JF, Stabel JR, Paustian ML, Reinhardt TA, Bannantine JP. 2005. Expression library immunization confers protection against Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis infection. Infect. Immun. 73: 6877–6884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nonnecke BJ, Waters WR, Foote MR, Palmer MV, Miller BL, Johnson TE, Perry HB, Fowler MA. 2005. Development of an adult-like cell-mediated immune response in calves after early vaccination with Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin. J. Dairy Sci. 88: 195–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chiodini RJ, Van Kruiningen HJ, Merkal RS. 1984. Ruminant paratuberculosis (Johne's disease): the current status and future prospects. Cornell Vet. 74: 218–262 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sweeney RW. 1996. Transmission of paratuberculosis. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract. 12: 305–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sweeney RW, Whitlock RH, Rosenberger AE. 1992. Mycobacterium paratuberculosis isolated from fetuses of infected cows not manifesting signs of the disease. Am. J. Vet. Res. 53: 477–480 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morein B, Abusugra I, Blomqvist G. 2002. Immunity in neonates. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 87: 207–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stabel JR, Robbe-Austerman S. 2011. Early immune markers associated with Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis infection in a neonatal calf model. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 18: 393–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mikkelsen H, Aagaard C, Nielsen SS, Jungersen G. 2011. Novel antigens for detection of cell mediated immune responses to Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis infection in cattle. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 143: 46–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Agger EM, Rosenkrands I, Hansen J, Brahimi K, Vandahl BS, Aagaard C, Werninghaus K, Kirschning C, Lang R, Christensen D, Theisen M, Follmann F, Andersen P. 2008. Cationic liposomes formulated with synthetic mycobacterial cordfactor (CAF01): a versatile adjuvant for vaccines with different immunological requirements. PLoS One 3: e3116 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mikkelsen H, Jungersen G, Nielsen SS. 2009. Association between milk antibody and interferon-gamma responses in cattle from Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis infected herds. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 127: 235–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Morrison WI, Bourne FJ, Cox DR, Donnelly CA, Gettinby G, McInerney JP, Woodroffe R. 2000. Pathogenesis and diagnosis of infections with Mycobacterium bovis in cattle. Independent Scientific Group on Cattle TB. Vet. Rec. 146: 236–242 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Anderson TW. 1984. Introduction to multivariate statistical analysis. Wiley, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lehmnann EL. 2006. Nonparametrics: statistical methods based on ranks. Springer, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cooper AM, Dalton DK, Stewart TA, Griffin JP, Russell DG, Orme IM. 1993. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon gamma gene-disrupted mice. J. Exp. Med. 178: 2243–2247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Flynn JL, Chan J, Triebold KJ, Dalton DK, Stewart TA, Bloom BR. 1993. An essential role for interferon gamma in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Exp. Med. 178: 2249–2254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stabel JR. 2000. Cytokine secretion by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from cows infected with Mycobacterium paratuberculosis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 61: 754–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sweeney RW, Jones DE, Habecker P, Scott P. 1998. Interferon-gamma and interleukin 4 gene expression in cows infected with Mycobacterium paratuberculosis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 59: 842–847 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Delvig AA, Lee JJ, Chrzanowska-Lightowlers ZM, Robinson JH. 2002. TGF-β1 and IFN-gamma cross-regulate antigen presentation to CD4 T cells by macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 72: 163–166 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Adams LG, Babiuk L, McGavin D, Nordgren R. 2009. Special issue around veterinary vaccines, p 225–254 In Ian DTB, Lawrence RS. (ed), Vaccines for biodefence and emerging and neglected diseases. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 34. Olsen I, Boysen P, Kulberg S, Hope JC, Jungersen G, Storset AK. 2005. Bovine NK cells can produce gamma interferon in response to the secreted mycobacterial proteins ESAT-6 and MPP14 but not in response to MPB70. Infect. Immun. 73: 5628–5635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Park SU, Kathaperumal K, McDonough S, Akey B, Huntley J, Bannantine JP, Chang YF. 2008. Immunization with a DNA vaccine cocktail induces a Th1 response and protects mice against Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis challenge. Vaccine 26: 4329–4337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shin SJ, Chang CF, Chang CD, McDonough SP, Thompson B, Yoo HS, Chang YF. 2005. In vitro cellular immune responses to recombinant antigens of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 73: 5074–5085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Leyten EM, Lin MY, Franken KL, Friggen AH, Prins C, van Meijgaarden KE, Voskuil MI, Weldingh K, Andersen P, Schoolnik GK, Arend SM, Ottenhoff TH, Klein MR. 2006. Human T-cell responses to 25 novel antigens encoded by genes of the dormancy regulon of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbes Infect. 8: 2052–2060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nonnecke BJ, Waters WR, Goff JP, Foote MR. 2012. Adaptive immunity in the colostrum-deprived calf: response to early vaccination with Mycobacterium bovis strain bacille Calmette Guerin and ovalbumin. J. Dairy Sci. 95: 221–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Abbas B, Riemann HP. 1988. IgG, IgM and IgA in the serum of cattle naturally infected with Mycobacterium paratuberculosis. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 11: 171–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Knust B, Patton E, Ribeiro-Lima J, Bohn JJ, Wells SJ. 2013. Evaluation of the effects of a killed whole-cell vaccine against Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis in 3 herds of dairy cattle with natural exposure to the organism. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 242: 663–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]