Abstract

MUC1 variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs) conjugated to tumor-associated carbohydrate antigens (TACAs) have been shown to break self-tolerance in humanized MUC1 transgenic mice. Therefore, we hypothesize that a MUC1 VNTR TACA-conjugate can be successfully formulated into a liposome-based anti-cancer vaccine. The immunogenicity of the vaccine should be further augmented by incorporating surface displayed L-rhamnose (Rha) epitopes onto the liposomes to take advantage of a natural antibody-dependent antigen uptake mechanism. To validate our hypothesis we synthesized a 20-amino acid MUC1 glycopeptide containing a GalNAc-O-Thr (Tn) TACA by SPPS and conjugated it to a functionalized Toll-like receptor ligand (TLRL). An L-Rha-cholesterol conjugate was prepared using tetraethylene glycol (TEG) as a linker. The liposome-based anti-cancer vaccine was formulated by the extrusion method using TLRL-MUC1-Tn conjugate, Rha-TEG-cholesterol and 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC) in a total lipid concentration of 30 mM. The stability, homogeneity and size characterization of the liposomes was evaluated by SEM and DLS measurements. The formulated liposomes demonstrated positive binding with both anti-Rha and mouse anti-human MUC1 antibodies. Groups of female BALB/c mice were immunized and boosted with a rhamnose-Ficoll (Rha-Ficoll) conjugate formulated with alum as adjuvant to generate the appropriate concentration of anti-Rha antibodies in the mice. Anti-Rha antibody titers were >25-fold higher in the groups of mice immunized with the Rha-Ficoll conjugate than the non-immunized control groups. The mice were then immunized with the TLRL-MUC1-Tn liposomal vaccine formulated either with or without the surface displaying Rha epitopes. Sera collected from the groups of mice initially immunized with Rha-Ficoll and later vaccinated with the Rha-displaying TLRL-MUC1-Tn liposomes showed a >8-fold increase in both anti-MUC1-Tn and anti-Tn antibody titers in comparison to the groups of mice that did not receive Rha-Ficoll. T-cells from BALB/c mice primed with a MUC1-Tn peptide demonstrated increased proliferation to the Rha-liposomal vaccine in the presence of antibodies isolated from Rha-Ficoll immunized mice compared to nonimmune mice, supporting the proposed effect on antigen presentation. The anti-MUC1-Tn antibodies in the vaccinated mice serum recognized MUC1 on human leukemia U266 cells. Because this vaccine uses separate rhamnose and antigenic epitope components, the vaccine can easily be targeted to different antigens or epitopes by changing the peptide without having to change the other components.

Introduction

Tumor-associated carbohydrate antigens (TACAs) have found use in cancer immunotherapy as markers for cancer detection and disease progression.1,2,3 The overexpression and aberrant structural distribution of TACAs on tumor cells relative to normal cells makes them potential targets for anti-cancer vaccines.4–8 Numerous TACAs have been identified from the glycoprotein MUC1 obtained from cancer cells of epithelial origin. Some of these antigens include the Thomsen-Friedenreich (TF), Tn, STn as well as α-2,6-sialyl-TF and α-2,3-sialyl-TF antigens.9,10,11 A recent finding made by Finn and coworkers reported that MUC1 variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs) containing TACAs were more potent at breaking self tolerance in MUC1 transgenic mice than the unglycosylated VNTR.12,13 The authors believe that the glycopeptide is a more ‘foreign’ like epitope in comparison to the unglycosylated MUC1 which is more ‘self’ like. Vaccination with TACA-containing MUC1 was successful in generating glycopeptide specific antibodies and boosting previously suppressed MUC1 specific T-cell responses. Further, they identified a population of dendritic cells (DCs) that display the VNTRs bearing the GS(GalNAc-O-T)A epitope on MHC class-II molecules.

We have considered different ways in which a MUC1 glycopeptide could be formulated into an anti-cancer vaccine with improved immunogenicity. We believe that an interesting approach would be to incorporate xenoantigens onto the target antigen. The xenoantigens would complex naturally occurring cognate antibodies which would facilitate uptake of the target antigen by antigen presenting cells (APCs). Past studies have focused on the installation of α-Gal epitopes on vaccine constructs to boost the immune response with promising results,14 since human serum is abundant in anti-α-Gal antibodies.15–17 However, recent studies by both Bovin and Gildersleeve on human serum have revealed that even more abundant human natural anti-carbohydrate antibodies are present against the xenoantigen L-rhamnose (Rha).18,19 Further, anti-Rha antibodies can be generated in non-transgenic mice in contrast to anti-α-Gal antibodies,20,21 In this paper we explore the Rha eptiope as a noncovalently-linked ligand displayed on the surface of a liposomal vaccine for enhancing the immune response against a tumor-associated glycopeptide fragment of MUC1 in mice producing anti-Rha antibodies.21

An important strategy for the development of successful anti-cancer vaccines is the efficient delivery of the antigens to the APCs.22,23 Liposomes have been effective in the delivery of viral, bacterial and tumor antigens to APCs24,25 and have the advantage of protecting peptide-based antigens against proteolysis in vivo. Liposomes also generate multivalency in the vaccine, promoting numerous antigen-antibody interactions facilitating opsonization of the vaccine. Additional mechanisms may also involve Rha epitopes interacting with endogenous B-cell receptors (BCRs) to uptake and present antigens on B-cells.15

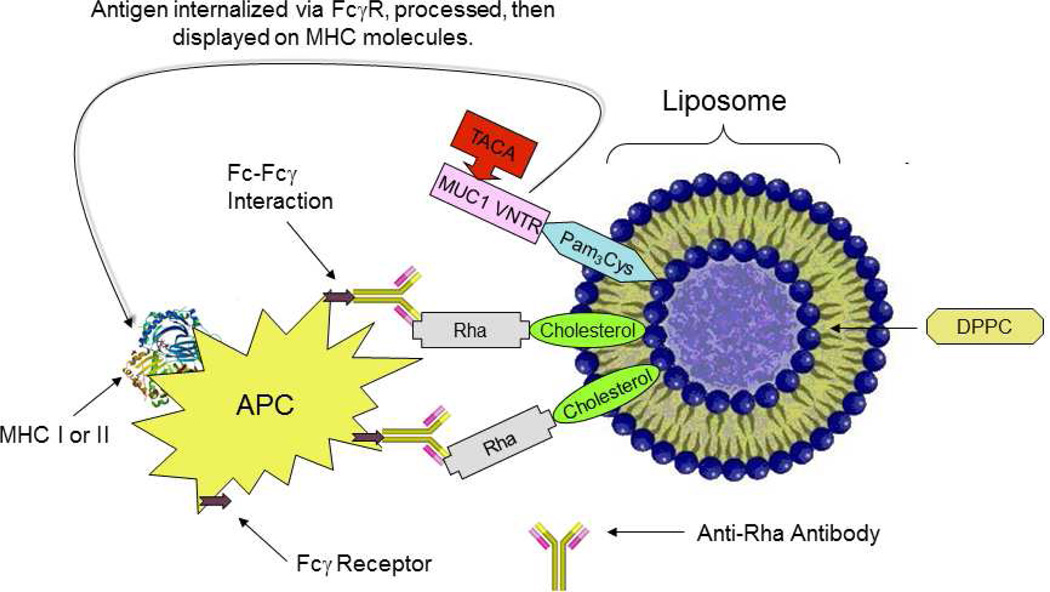

Vaccine immunogenicity can also be improved by the introduction of an adjuvant. Toll-like receptor ligands (TLRL), for example, have potent adjuvant activity.26 Therefore we incorporated the prototypic TLR-2 ligand, Pam3Cys, into our vaccine synthesis to serve the dual role of adjuvant and lipid anchor to a liposome. Further, we envisioned a liposome capable of displaying Rha epitopes, the latter designed to bind endogenous anti-Rha antibodies in human serum. The resulting Ig-vaccine complex would then be taken up by APCs (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of Fc-Fcγ interaction in the in vivo generated immune complex leading to enhanced antigen uptake by APCs, e.g. dendritic cells.

Experimental Procedures

General Methods

All fine chemicals such as L-rhamnose, cholesterol, p-toluene sulfonyl chloride, copper sulfate etc. and anhydrous solvents such as anhydrous methanol were purchased from Acros Organics. 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC) was obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids Inc. (Alabaster, AL). Boron trifluoride etherate was from Aldrich. The chemicals were used without further purification. All solvents were obtained from Fisher and used as received except dichloromethane, which was dried and distilled following the standard procedures.27 Silica (230–400 mesh) for flash column chromatography was obtained from Sorbent Technologies; thin-layer chromatography (TLC) precoated plates were from EMD. TLCs (silica gel 60, f254) were visualized under UV light or by charring (5% H2SO4-MeOH). Flash column chromatography was performed on silica gel (230–400 mesh) using solvents as received. 1H NMR was recorded either on a Varian VXRS 400 MHz or an INOVA 600 MHz spectrometer in CDCl3 or CD3OD using residual CHCl3 and CHD2OH as internal references, respectively. 13C NMR was recorded on a Varian VXRS 100.56 MHz or an INOVA 150.84 MHz in CDCl3 using the triplet centered at δ 77.273 or CD3OD using the septet centered at δ 49.0 as internal reference. High resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) was performed on a TOF mass spectrometer. The peptide was synthesized on an Omega 396 synthesizer (Advanced ChemTech, Louisville, KY). Tris [(1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl] amine (TBTA), preloaded Fmoc-L-Ala-Wang resin and all other Fmoc-L-amino acids were procured from Anaspec (San Jose, CA). FicollR 400 and ImjectR Alum were purchased from Sigma and Thermo Scientific respectively. FITC goat antimouse IgG/IgM and purified mouse anti-human CD227 (anti-human MUC1) were obtained from BD-biosciences (San Jose, CA). Scanning electron microscope imaging was done on a JEOL JSM-7500F field scanning electron microscope. Dynamic light scattering measurements were done with a DynaPro Titan temperature controlled microsampler (Wyatt Technology Corporation). Fluorescence microscopy was done on a Nikon TiU microscope. All other secondary antibodies were obtained from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA). Female BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks old) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). U266 human leukemia cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA).

(5-Cholesten-3α-yloxy)-3n39-trixaundecanyl 2,3,4-Tri-O-acetyl-α-L-rhamnopyranoside (2)

To a solution of 1,2,3,4-tetra-O-acetyl rhamnopyranose (0.64 g, 1.92 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (3 mL) was added (5-cholesten-3α-yloxy)-n39-trixaundecan-1-ol (1.30g, 2.30 mmol) in CH2Cl2 and the mixture was cooled to 0 °C. BF3.OEt2 (486 mL, 3.84 mmol) was added dropwise to the reaction mixture and the resulting solution was stirred at ambient temperature under N2 atmosphere. The reaction was monitored by TLC (EtOAc:hexanes = 1:1) and appeared complete after 18 h. The reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (25 mL) and washed with saturated NaHCO3 (25 mL), water (25 mL) and brine (25 mL) after which the organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. Excess solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and the residue was purified by silica gel flash column chromatography using 30% EtOAc in hexanes as solvent to afford 2 as a light yellow solid (0.51 g, 32%). 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.67 (s, 3H, cholesterol), 0.85–1.15 (23H, cholesterol), 1.21 (d, 3H, J = 6 Hz, C-5 CH3), 1.24–1.52 (12H, cholesterol), 1.80–1.95 (5H, cholesterol), 1.98 (s, 3H, COCH3), 2.05 (s, 3H, COCH3), 2.15 (s, 3H, COCH3), 3.17 (m, 1H, −OCH-cholesterol), 3.63–3.66 (16H, −CH2-CH2O-TEG), 3.92 (m, 1H, H-5), 4.77 (d, 1H, J = 1.8 Hz, H-1), 5.06 (t, 1H, J = 10.2 Hz, H-4), 5.26 (dd, 1H, J = 1.8, 3.6 Hz, H-2), 5.30 (dd, 1H, J = 4.2, 9.9 Hz, H-3), 5.33 (m, 1H, −C=CH-cholesterol). 13C NMR (100.56 MHz, CDCl3): δ 12.04, 17.61, 18.90, 19.58, 20.95, 21.03, 21.14, 21.25, 22.76, 23.02, 24.01, 24.48, 28.21, 28.43, 28.53, 29.90, 32.07, 32.13, 35.97, 36.37, 37.07, 37.42, 39.23, 39.70, 39.96, 42.50, 50.36, 53.63, 56.32, 56.96, 66.46, 67.30, 67.46, 69.30, 70.03, 70.24, 71.35, 79.68, 97.74 (C-1), 121.74 (C=C), 141.15 (C=C), 170.18 (COCH3), 170.25 (COCH3), 170.32 (COCH3). HRMS [M + Na] m/z: calcd for C47H78NaO12, 857.5391; found, 857.5396.

(5-Cholesten-3α-yloxy)-3n39-triundecanyl Rhamnopyranoside (3)

To a solution of 2 (0.45 g, 0.54 mmol) in MeOH (10 mL) was added metallic sodium (0.03 g) and the resulting solution was stirred at ambient temperature under N2 atmosphere. The reaction was monitored by TLC (5% MeOH in CH2Cl2) and appeared complete after 1 h. The solution was neutralized by Amberlite H+ exchange resin. Excess solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and the residue was purified by silica gel flash column chromatography using 5% MeOH in CH2Cl2 as solvent to afford 3 as a yellowish white solid (0.32 g, 85%). 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.68 (s, 3H, cholesterol), 0.86 – 1.25 (24H, cholesterol), 1.32 (d, 3H, J = 6 Hz, C-5 CH3), 1.44 – 1.53 (16H, cholesterol), 2.83 (s, 1H, C-4 OH), 3.08 (d, 1H, J = 3 Hz, H-1), 3.20 (m, 1H, −O-CH-cholesterol), 3.43 (t, 1H, J = 9.6 Hz, H-4), 3.62 – 3.71 (16H, −CH2-CH2O-TEG), 3.73 (m, 1H, H-5), 3.83 (dd, 1H, J = 3, 6.9 Hz, H-3), 3.98 (s, 1H, H-2), 4.87 (s, 1H, C-2 OH), 5.31 (s, 1H, C-3 OH), 5.35 (m, 1H, −C=CH-cholesterol). 13C NMR (100.56 MHz, CDCl3): δ 12.07, 17.83, 18.92, 19.60, 21.27, 22.78, 23.04, 24.03, 24.50, 28.23, 28.44 (2), 32.08, 32.15, 35.99, 36.39, 37.06, 37.39, 39.09, 39.73, 39.97, 42.53, 50.36, 56.34, 56.97, 66.74, 67.32, 68.07, 70.48, 70.63, 70.75, 70.81, 70.93, 70.97, 71.05, 71.80, 73.81, 79.87, 99.98 (C-1), 121.96 (C=C-cholesterol), 140.98 (C=C-cholesterol). HRMS [M + Na] m/z: calcd for C41H72NaO9, 731.5074; found, 731.5090.

N-propargyl Pam2FmocCys Amide Derivative 5

Pam2FmocCys tertiary butyl ester (0.30 g, 0.32 mmol) was dissolved in a minimum volume of neat TFA (1 mL) and stirred at ambient temperature under N2 atmosphere. TLC (EtOAc:hexanes = 1:4) indicated the completion of the reaction after 1 h. The reaction mixture was evaporated to dryness under vacuum and the residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (3 mL). PyBOP (198 m g, 0.38 mmol), HOBt (58 mg, 0.38 mmol), DIPEA (78 µL, 0.47 mmol) and 4 A mol. sieves (2–3 beads) were added sequentially and the mixture was stirred for 5 minutes at room temperature followed by the addition of propargyl amine (25 µL, 0.38 mmol) and stirred at ambient temperatures under N2 atmosphere. The reaction was monitored by TLC (EtOAc:hexanes = 1:4) and appeared complete after 4 h. The reaction mixture was filtered, washed with phosphate buffer (10 mL) and extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 10 mL). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated. The residue was purified by silica gel flash column chromatography using EtOAc-hexanes (1:4) as solvent to afford 5. as a white solid (192 mg, 66%). 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.87 (t, 6H, J = 7.2 Hz, Pam-CH3), 1.14 – 1.65 (m, 52H, Pam-CH2), 1.68 (s, 1H, alkyne-CH), 2.18–2.35 (m, 4H, COCH2), 2.83 (m, 1H, Cys-CHH), 2.89 (dd, 1H, J = 7.2, 14.4 Hz, S-glyceryl-O-CHH), 3.01 (dd, 1H, J = 6, 14.4 Hz, Cys-CHH), 4.06 (dd, 1H, J = 3, 4.8 Hz, S-glyceryl-O-CHH), 4.08 (s, 2H, CO-NH-CH2), 4.18 (dd, 1H, J = 6, 11.4 Hz, S-glyceryl-O-CHH), 4.23 (t, 1H, J = 7.2 Hz, Fmoc-CH), 4.39 (m, 1H, NH-CH-CO), 4.42 (m, 2H, Fmoc-CH2), 5.12 (m, 1H, S-glyceryl-O-CH), 5.73 (d, 1H, J = 7.8 Hz, Pam-NH), 6.89 (s, 1H, CO-NH-CH2), 7.31 – 7.81 (m, 8H, Fmoc-ArH). 13C NMR (150.84 MHz, CDCl3): δ 14.35 – 36.70 (30C, Pam-C), 47.29 (2), 53.32, 63.58, 67.48, 70.61, 71.78, 72.07, 79.09, 79.85, 120.22, 125.30, 127.30 (2), 127.97 (2) 141.49, 141.50, 143.85, 143.89 (Aromatic-C), 170.07, 173.66 (2), 174.04 (Cys-CO). HRMS [M + Na] m/z: calcd for C56H86N2NaO7S, 953.6053; found, 953.6073.

N-propargyl Pam3Cys Amide Derivative 6

Compound 5 (192 mg, 0.21 mmol) was dissolved in a mixture of CH3CN-CH2Cl2-Et2NH (2:1:2, 2.50 mL) and stirred at ambient temperature under N2 atmosphere. TLC (EtOAc:hexanes = 1:4) indicated the complete deprotection of the Fmoc group after 2 h. The reaction mixture was evaporated to dryness under vacuum. Palmitic acid (64 mg, 0.25 mmol), PyBOP (128 mg, 0.25 mmol), and HOBt (38 mg, 0.25 mmol) were dissolved in CH2Cl2 (3 mL) followed by the addition of DIPEA (51 µL, 0.31 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 5 minutes and added to the residue of the Fmoc deprotected product from compound 5 containing 4 A mol. sieves (2–3 beads). The reaction mixture was stirred at ambient temperature under N2 atmosphere. The reaction was monitored by TLC (EtOAc:hexanes = 1:4) and appeared complete after 4 h. The reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (15 mL), filtered and evaporated to dryness. The residue was purified by silica gel flash column chromatography using EtOAC – hexanes (1 : 4) as solvent to afford 6 as a pale yellow solid (156 mg, 80%). 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.88 (t, 12H, J = 6.6 Hz, Pam-CH3), 1.10 – 1.63 (m, 78H, Pam-CH2), 2.23 (s, 1H, Alkyne-CH), 2.24 – 2.36 (m, 6H, COCH2), 2.71 (dd, 1H, J = 7.8, 14.4 Hz, Cys-CHH), 2.86 (m, 6H, COCH2), 2.95 (dd, 1H, J = 6, 14 Hz, Cys-CHH), 4.06 (m, 2H, CO-NH-CH2), 4.18 (dd, 1H, J = 6.6, 12 Hz, S-glyceryl-O-CHH), 4.40 (dd, 1H, J = 3, 12 Hz, S-glyceryl-O-CHH), 4.64 (q, 1H, J = 6 Hz, NH-CH-CO), 5.12 (m, 1H, S-glyceryl-OCH), 6.64 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz, Pam-NH), 7.02 (t, 1H, J = 5.4 Hz, CO-NH-CH2). 13C NMR (150.84 MHz, CDCl3): δ 14.35 – 42.19 (48C, Pam-C, Cys-Cβ, S-glyceryl-C, NH-C), 51.30 (Cys-Cα), 63.65, 70.61, 71.98, 79.08, 170.40 (Cys-CO), 173.70, 173.86, 174.06 (Pam-CO). HRMS [M + Na] m/z: calcd for C57H106N2NaO6S, 969.7669; found, 969.7682.

Glycopeptide Azide 9

The glycopeptide azide was synthesized by Fmoc strategy on an Omega 396 synthesizer (Advanced ChemTech, Louisville, KY) using solid phase chemistry. The peptide synthesis was performed by coupling amino acid esters of HOBt using DIC as the coupling agent. A 6-fold excess of Nα-Fmoc amino acid esters of HOBt in NMP were used in the synthesis. A 1:1 ratio of amino acid to DIC was used in all the coupling reactions. Deprotection of the Nα-Fmoc group was accomplished by treatment with 25% piperidine in dimethylformamide twice; first for 5 minutes and then a second time for 25 minutes. After the synthesis was complete, the peptide was cleaved from the solid support and deprotected using a modified reagent K cocktail consisting of 88% TFA, 3% thioanisole, 5% ethanedithiol, 2% water and 2% phenol. 4 mL of cleavage cocktail was added to the dried peptide-resin in a 15 mL glass vial blanketed with nitrogen. Cleavage was carried out for 2.5 hrs with gentle magnetic stirring. At the end of the cleavage time, the cocktail mixture was filtered on a Quick-Snap column. The filtrate was collected in 20 mL ice-cold butane ether. The peptide was allowed to precipitate for an hour at −20 °C, centrifuged, and washed twice with ice-cold methyl-t-butyl ether. The precipitate was dissolved in 25% acetonitrile and lyophilized to complete dry powder. Quality of peptides was analyzed by analytical reverse phase HPLC and MALDI-TOF (matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight) mass spectrometer, model 4800 from Applied Biosystems. HR-MALDI-MS: [M+H] m/z calcd for C100H155N29O37, 2355.1172; found, 2355.1753.

Glycopeptide Azide 10

Compound 9 (5 mg, 2.24 µmol) was dissolved in 2 mL of dry methanol and 12 µL of freshly prepared 1 M sodium methoxide was added and the reaction mixture was stirred at ambient temperature under N2 atmosphere for 2 h. The reaction mixture was neutralized with solid carbon dioxide. The reaction mixture was concentrated and purified by Bio-Gel (P-2, fine 45–90 µm) size exclusion chromatography using deionized water as solvent. Lyophilization of the elutants afforded 10 as a white powder (4.7 mg, 100%). HR-MALDI-MS: [M+H] m/z calcd for C94H149N29O34, 2229.0895; found 2229.0959.

Lipopeptide 11

CuSO4.5H2O (134 µg, 0.54 µmol) and TBTA (2.14 mg, 4.04 µmol) were dissolved in H2O – THF (1:1, 0.40 mL) and to it Na-ascorbate (0.80 mg, 4.04 µmol) was added and stirred for 5 minutes. Compound 6 (1.27 mg, 1.35 µmol) in THF (0.40 mL) was added to the reaction mixture and stirred for 15 minutes followed by the addition of a solution of compound 10 (1 mg, 0.45 µmol) in H2O-MeOH (1:3, 0.4 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at ambient temperature under N2 atmosphere for 40 h. The reaction mixture was concentrated, dissolved in CH2Cl2-MeOH (1:1) and purified by a short LH 20 size exclusion column using CH2Cl2-MeOH (1:1) as solvent. Lyophilization of the elutants afforded 11 as a white solid (1.9 mg, 100%). HR-MALDI-MS: [M+H] m/z calcd for C151H255N31O40S, 3175.593; found 3175.425. A mass peak corresponding to a protonated methyl ester of the product was also observed.

Liposome Formulation

Lipid stock solutions were prepared by dissolving each lipid into chloroform inside glass vials. Aliquots of the stock solutions were mixed in proportions in another small glass vial to give a solution with a total lipid concentration of 30 mM in a total volume of 2 mL (Batch 1: DPPC 80%, Cholesterol 10%, Rha-cholesterol 10% and Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn 0.69 ZM; Batch 2: DPPC 80%, cholesterol 20%, Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn 0.69 ZM; Batch 3: DPPC 80%, cholesterol 20%). Chloroform was removed by subjecting the lipid solutions to a constant stream of nitrogen. The resulting lipid films were dried under vacuum overnight. The dried lipid films were hydrated with 2 mL of HEPES buffer (pH = 7.4). The suspensions of the lipids in the buffer were agitated at 43 °C for 40 mins. The suspensions were subjected to 10 freeze-thaw cycles (dry ice/acetone and water at 40 °C). Final liposomes were prepared by extrusion (21 times) using a LipoFast Basic fitted with a 100 nm polycarbonate membrane to control the liposome size.

Liposome characterization

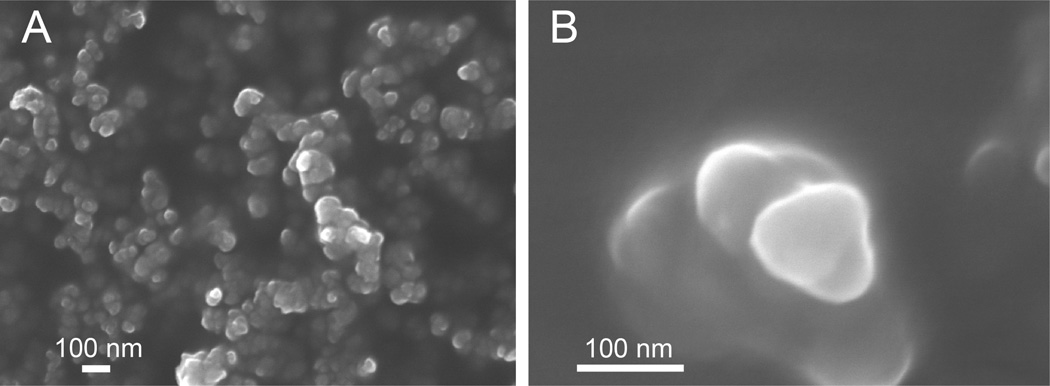

Liposome Size Characterization

Size determination of the liposomes was done by scanning electron microscope (SEM) imaging and dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements. For SEM characterization the liposome samples were diluted 1000 times with HEPES buffer (pH = 7.4) and freeze dried over copper studs fitted with a carbon conducting tape and the images recorded at an acceleration voltage of 5 kV. DLS measurements were done after dilution of the liposome samples 10000 times with HEPES buffer (pH = 7.4).

Anti-Rha and Anti-MUC1 Antibody Binding to Surface Exposed Rha and MUC1 Epitopes on Liposomes

One million liposomes from each batch in 50 ZL phosphate buffered saline (PBS) were added separately into a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube followed by 50 ZL of primary antibody solution, prepared by dilution in deionized water containing 5–50 Zg/mL of antibodies [either control IgG (isolated from the serum of non-immunized mice) or anti-Rha IgG isolated from the serum of Rha-ovalbumin immunized mice21 or mouse anti-human CD227 monoclonal antibodies (anti-human MUC1)] and incubated on ice for 30 mins. 1 mL PBS-0.1% Tween was added to each tube and vortexed. Liposomes were centrifuged at 14000 rpm in an Eppendorf centrifuge at 4 °C for 5 mins. The supernatants were carefully discarded and the washing and centrifugation steps were repeated 2 more times for a total of 3 washes. Liposomes were then resuspended in 50 ZL of PBS-0.1% Tween. 50 ZL of diluted FITC goat anti-mouse IgG/IgM secondary antibody were added (2–30 Zg/mL) to the tubes, mixed and covered with aluminum foil to protect from light and incubated on ice for 30 mins. After washing 3 times with PBS-0.1% Tween and centrifugation, the supernatants were removed and pellets were resuspended in 1 mL PBS-0.1% Tween. 10 ZL of the resuspended solutions were put on glass slides and imaged under a fluorescence microscope.

2-Azidoethyl-2,3,4-Tri-O-acetyl-α-L-rhamnopyranoside (13)

To a solution of 1,2,3,4-tetra-O-acetylrhamnopyranoside (12) (2.00 g, 6.02 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (5.00 mL) were added 2-azidoethanol (0.79 g, 9.03 mmol) and BF3.OEt2 (1.53 mL, 12.04 mmol) at 0 °C and the resulting solution was stirred at ambient temperature under N2 atmosphere. The reaction was monitored by TLC and appeared to be complete after 12 h. The reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (15 mL) and washed with water (2 × 20 mL), saturated NaHCO3 (2 × 20 mL) and brine (20 mL), after which the organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. Excess solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the crude material was purified by silica gel flash column chromatography (3.3 × 8.5 cm). Elution with 1:5 EtOAc/hexanes afforded 13 as a colorless solid (1.78 g, 83%). 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.24 (d, 3H, J = 6.6 Hz, C-5 CH3), 1.99 (s, 3H, COCH3), 2.06 (s, 3H, COCH3), 2.16 (s, 3H, COCH3), 3.42 (m, 1H, −CHH-N3), 3.48 ( m, 1H, −CHH-N3), 3.64 (m, 1H, −O-CHH), 3.87 (m, 1H, −O-CHH), 3.93 (m, 1H, H-5), 4.79 (d, 1H, J = 1.8 Hz, H-1), 5.09 (t, 1H, J = 10.2 Hz, H-4), 5.27 (dd, 1H, J = 1.2, 3.3 Hz, H-2), 5.31 (dd, 1H, J = 3.3, 9.9 Hz, H-3). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 17.66 (CH3), 20.93, 21.03, 21.13, 50.58, 66.91, 66.99, 69.08, 69.87, 71.09, 97.79 (C-1), 170.09 (C=O), 170.24 (C=O), 170.30 (C=O). HRMS [M + Na] m/z: calcd for C14H21N3O8, 382.1226; found, 382.1215.

2-Azidoethyl α-L-Rhamnopyranoside (14)

To a solution of 13 (1.53 g, 4.26 mmol) in MeOH (5 mL) was added metallic Na (0.01 g) and the resulting solution was stirred at ambient temperature under N2 atmosphere. The reaction was monitored by TLC and appeared complete after 2 h. Excess solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the crude material was purified by silica gel flash column chromatography (3.3 × 8.5 cm). Elution with 2:23 MeOH/CH2Cl2 yielded 14 as a colorless solid (0.85 g, 86%). 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.34 (d, 3H, J = 6.6 Hz, C-5 CH3), 3.41 (m, 2 H, −CH2-N3), 3.49 (t, 1 H, J = 9.3 Hz, H-4), 3.63 (m, 1H, −O-CHH), 3.69 (m, 1H, H-5), 3.81 (dd, 1H, J = 3.3, 9.3 Hz, H-3), 3.89 (m, 1H, −O-CHH), 3.99 (q, 1H, J = 1.6 Hz, H-2), 4.83 (d, 1H, J = 1.2 Hz, H-1). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 17.75 (CH3), 50.71, 66.72, 68.49, 70.98, 71.76, 73.27, 100.02 (C-1). HRMS [M + Na] m/z: calcd for C8H15N3O5, 256.0909; found, 256.0906.

2-Aminoethyl α-L-Rhamnopyranoside (15)

To a solution of 14 (0.42 g, 1.82 mmol) in MeOH (3 mL) was added activated Pd/charcoal (0.025 g) and the resulting solution was stirred at ambient temperature under H2 atmosphere. The reaction was monitored by TLC and appeared to be complete after 12 h. The reaction mixture was diluted with MeOH (2 mL), filtered through Celite and concentrated under reduced pressure to yield 15 as a colorless gel (0.46 g, quantitative) which was used without further purification for subsequent reactions. ESIMS [M + H] m/z: cacld for C8H17NO5, 208.2243; found, 208.30.

2-Aminoethyl α-L-Rhamnopyranoside-Ficoll Conjugate (16)

Ficoll 400 (1.00 g, 0.0025 mmol) was dissolved in acetate buffer (10 mL, pH 4.7) and NaIO4 (0.01 g, 0.047 mmol) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 2 h in the dark. Excess NaIO4 was removed by dialysis against the acetate buffer (pH 4.7) through dialysis tubing with a molecular weight cutoff value of 10000 Da with six to seven changes of the buffer at 4 °C. The oxidized Ficoll 400 was transferred to a round bottom flask and excess solvent was evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in borate buffer (20 mL, pH 8.0) followed by the addition of 15 (0.05 g, 0.25 mmol) and stirred at ambient temperature for 2 h. To the reaction mixture was added NaBH3CN (0.094 g, 1.50 mmol) and the resulting solution was incubated overnight at 4 °C. The mixture was dialyzed through dialysis tubing with a molecular weight cutoff value of 10000 Da with six to seven changes in buffer at 4 °C to afford 16. The epitope ratio of 16 was calculated to be 9.44 (Rha:Ficoll) by hydrolysis of 16 followed by derivatization with 4-amino-N-[2-(diethylamino)ethyl] benzamide (DEAEAB) and comparison of the UV-HPLC peak area with a standard curve obtained from DEAEAB derivative of 14 by the methods described by Dalpathado and coworkers. Briefly, the standard curve was generated by refluxing Compound 14 (0.007 g, 0.031 mmol) with 1 N HCl at 100 °C for 4 h and the reaction mixture was evaporated to dryness. The residue was dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (2 mL) and DEAEAB (0.011 g, 0.037 mmol) and Et3N (0.007 mL, 0.046 mmol) were added and the resulting solution was refluxed for 2 h. The reaction mixture was evaporated to dryness and the residue was dissolved in MeOH (2 mL) followed by the addition of NaB(OAc)3H and the resulting solution refluxed for 8 h. The solution was evaporated to dryness and the residue was dissolved in MeOH (2 mL) and filtered through a syringe filter. Serial dilutions from this stock solution were prepared and the components were separated on a reverse phase HPLC using a C18 column. Water containing 0.1% TFA (A) and 95% ACN/H2O (B) were used as the mobile phases using a linear gradient (5–20% B in 20 min) at the flow rate of 1 mL/min. Absorbances were recorded at 289 nm. The standard curve was generated by plotting the UV-HPLC peak area against the concentration in mmol of DEAEAB derivative of 14.

T-Cell Proliferation Study. Immunization

One female BALB/c mouse (6–8 weeks old, The Jackson Laboratory) was primed (day 0) and boosted three times (days 14, 28 and 42) with 100 µL subcutaneous injections of an equivolume emulsion of the MUC1-Tn conjugate 10 (prepared in phosphate buffer saline-PBS) and sigma adjuvant system (SAS) (50 µg of peptide per mouse, each injection).

Preparation of Anti-Rha Antibodies

The Rha-Ficoll and the Rha-OVA immunized mice (Supporting Information) were bled on day 66 and the sera was pooled. IgG fractions from each pool were prepared by precipitation at 40% saturation of ammonium sulfate. The mixtures were incubated overnight and centrifuged at 10000 × g for 10 minutes and then resuspended in 0.5 mL water. The antibody solutions were concentrated and buffer was changed twice with PBS using an Ultrafree 0.5 centrifugal filter device (Millipore, Billerica, MA) having a molecular cut off of 50000 D. Absorbances of the antibody solutions were recorded at 280 nm to calculate the concentrations and the anti-Rha antibody solutions generated and isolated from the Rha-Ficoll and the Rha-OVA immunized mice were each diluted to 1.0 mg/mL.

Preparation of Spleen Cell Suspensions and Assay Setup

On day 49, the mouse was sacrificed and the spleen was removed and placed in 5 mL of freshly prepared spleen cell culture medium (DMEM with 10% fetal calf serum). Single cell suspension was prepared using modified sterile glass homogenizers. The cells were washed three times with culture medium and brought to 5 × 106 cells/mL. 100 µL of the spleen cell suspensions were added to 96 well plates (5×105 cells per well). The dendritic cell (DC) suspension cultured from the bone marrow of a BALB/c mouse (Supporting Information) was pulsed with the antigen by incubating with the Rha-displaying MUC1-Tn liposomes at antigen concentrations of 8.8×10−3 – 1.1 µg/mL at 37 °C for 4 h together with anti-Rha antibodies generated from either Rha-Ficoll or Rha-OVA immunized mice sera (5 µg per well) or with control antibodies isolated from non-immunized mice serum. 100 µL of the pulsed DCs was added to the wells containing the spleen cells (5 × 104 DCs per well). The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 4 days. On day 4 the cells were pulsed with [3H]-thymidine (40 µCi/mL, 25 µL per well) and incubated overnight at 37 °C. The cells were harvested on glass-fiber filters and incorporation was determined by measurements on a Top Count scintillation counter (Packard, Downers Grove, IL).

Immunizations

The 20 female BALB/c mice used for this study were divided into four groups A1, A2, B1 and B2 containing 5 mice each. Groups A1 and B1 served as the control groups and were not immunized. Groups A2 and B2 were injected subcutaneously (day 0) with a 100 µL equivolume emulsion of Rha-Ficoll conjugate 16 and Alum (100 µg of Rha-Ficoll per mouse). The mice were boosted with 100 µL subcutaneous injections of Rha-Ficoll/Alum on days 14, 28, 42 and 56 (100 µg of Rha-Ficoll per mouse, each boost). The mice in each groups A1, A2, B1 and B2 were bled on day 66 and the collected sera was tested for anti-Rha antibodies.

ELISA for Measuring Anti-Rha Antibody Titers

96 Well plates (Immulon 4 HBX) were coated with Rha-BSA conjugate 6 (2 µg/mL) in 0.01 M PBS and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The plates were washed 5 times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20. Blocking was achieved by incubating the plates for 1 h at room temperature with BSA in 0.01 M PBS (1mg/mL). The plates were then washed 5 times and incubated for 1 h with serum dilutions in PBS. Unbound antibody in the serum was removed by washing and the plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) goat anti-mouse IgG + IgM (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories) diluted 5000 times in PBS/BSA. The plates were washed and TMB (3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine) One component HRP microwell substrate (Bio FX, Owings Mills, MD) was added and allowed to react for 10 mins. Absorbances were recorded at 620 nm and were plotted against log10 [1/serum dilution].

Vaccinations

Vaccination was performed on day 77. Two separate liposomal formulations were prepared with DPPC (80%), cholesterol (20%) and Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn 11 (2 nmol) (Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn liposomes) and DPPC (80%), cholesterol (10%), Rha-TEG-cholesterol 3 (10%) and Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn 11 (2 nmol) (Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn +Rha liposomes) in total lipid concentrations of 30 mmol. Groups A1 and A2 were vaccinated with 100 µL subcutaneous injections of the Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn liposomes (2 nmol of peptide per mouse) and groups B1 and B2 were vaccinated with 100 µL subcutaneous injections of the Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn +Rha liposomes (2 nmol peptide per mouse). The mice were boosted on day 91 with either the Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn liposomes (groups A1 and A2, 2 nmol peptide per mouse) or the Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn +Rha liposomes (groups B1 and B2). The mice were bled on day 101 and the sera collected were tested for anti-MUC1-Tn and anti-Tn antibodies.

ELISA for Measuring Anti-MUC1-Tn Antibody Titers

96 Well plates (Immulon 4 HBX) were coated with MUC1-Tn conjugate 10 (15 µg/mL) in 0.01 M PBS and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The ELISA was continued as described above.

ELISA for Measuring Anti-Tn Antibody Titers

96 Well plates (Immulon 4 HBX) were coated with Tn-BSA conjugate (15 µg/mL) in 0.01 M PBS and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The ELISA was continued as described above.

Anti-MUC1-Tn Antibody Subclass Identification

96 Well plates (Immulon 4 HBX) were coated with MUC1-Tn conjugate 10 (15 µg/mL) in 0.01 M PBS and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The plates were washed 4 times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20. Blocking was achieved by incubating the plates for 1 h at room temperature with BSA in 0.01 M PBS (1mg/mL). The plates were then washed 4 times and incubated for 1 h with 1/100 serum dilution in PBS. Unbound antibody in the serum was removed by washing and the plates were incubated overnight at 4 °C with subclass specific (IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, 1gA and IgM) rabbit anti-mouse antibody (Zymed Laboratories mouse monoAb-ID kit). The plates were washed and incubated with HRP-goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) for 1 h at room temperature. The plates were washed and ABTS substrate buffer (diluted 50 times) was added and allowed to react for 30 min. Absorbances were recorded at 405 nm and compared for each antibody subclass in each group.

ELISA for Competitive Binding with Free MUC1-Tn

A 96 well plate (Immulon 4 HBX) was coated with MUC1-Tn conjugate 10 (15 µg/mL) in PBS and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The plate was washed 5 times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20. Blocking was achieved by incubating the plate for 1 h at room temperature with BSA in M PBS (1mg/mL). The plate was then washed 5 times and incubated for 1 h with serum dilutions of 1/100 in PBS with or without prior mixing with varying concentrations of free MUC1-Tn (compound 10) from 0, 10−5, 10−4, 10−3 M in PBS. Unbound antibody in the serum was removed by washing and the plate was incubated for 1 h at room temperature with Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) goat anti-mouse IgG + IgM (secondary antibody) diluted 5000 times in PBS/BSA. The plate was washed and TMB 1 component HRP microwell substrate was added and allowed to react for 10 mins. Absorbances were recorded at 620 nm and were plotted against log10 [1/free Tn concentration].

Tumor Cell Staining

U266 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA), were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 15% fetal calf serum (FCS). Cells were stained with purified mouse anti-human MUC1 antibodies (CD227, 0.5 µg), non-immune BALB/c mice serum (1/5 dilution) and group B2 mice serum (1/5 dilution). The cells were then stained with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG + IgM (0.5 µg) and fluorescence was quantified with a BD FACS Calibur.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of Rha-TEG-Cholesterol

To validate our hypothesis we first synthesized an L-Rha-cholesterol conjugate using tetraethylene glycol (TEG) as a linker which is reported to facilitate the formation of small-sized homogenous liposomes and allows good binding interaction of the head group28,29 (Scheme 1A). Cholesterol tetraethylene glycol 116 was glycosylated with peracetyl rhamnose in presence of boron trifluoride etherate to afford peracetyl rhamnose-TEG-cholesterol 2 (32%) which was deacetylated under Zemplen conditions to generate Rha-TEG-cholesterol 3 (85%).10 In a liposomal formulation the cholesterol fragment in 3 will anchor the Rha epitopes on the surface of the liposomes thereby facilitating anti-Rha antibody binding.

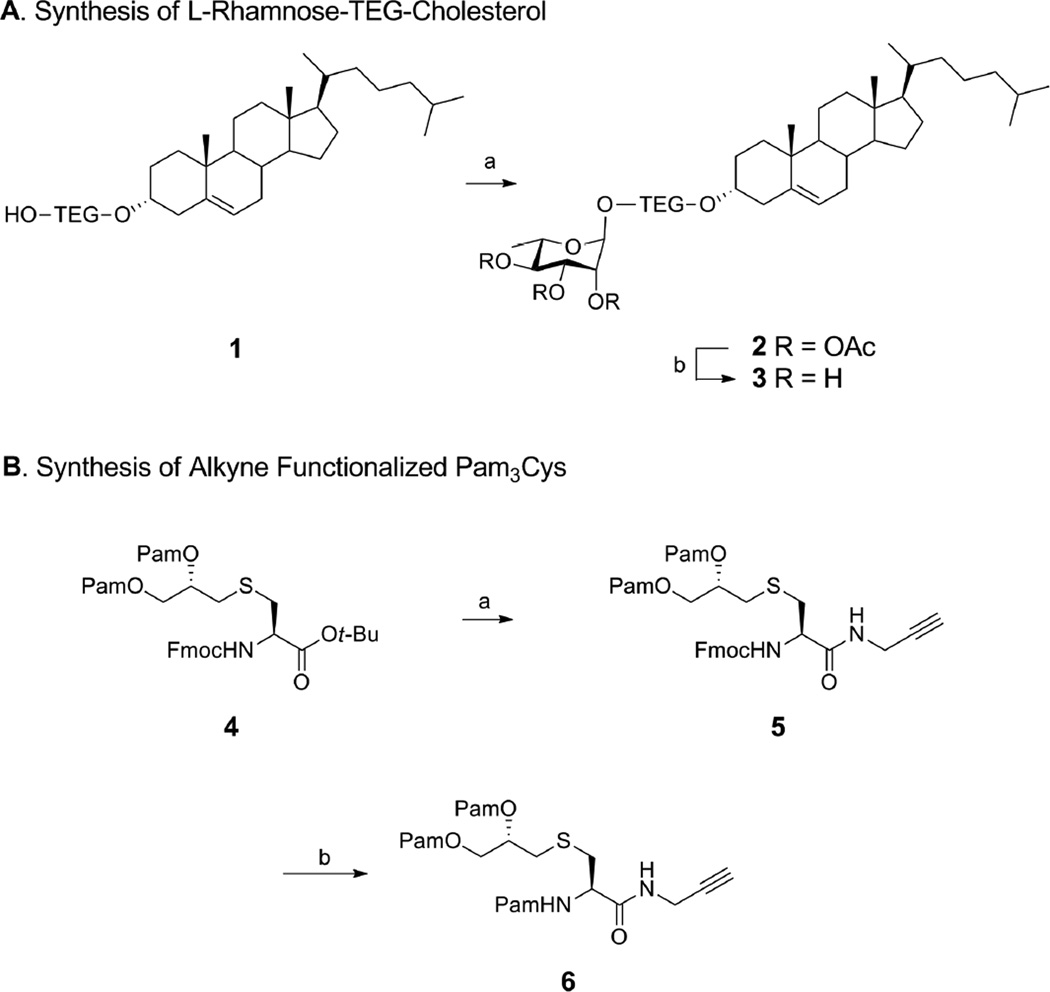

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Rha-TEG-Cholesterol and alkyne functionalized Pam3Cys.a

aReagents and conditions: (A) (a) peracetyl L-rhamnose, BF3.OEt2, CH2Cl2, 0 °C r.t., 18 h, 32%; (b) NaOMe, MeOH, r.t., 1 h, 85% [TEG= CH2CH2(OCH2CH2)3]; (B) (a) (i) TFA, r.t., 1 h; (ii) propargyl amine, PyBOP, HOBt, DIPEA, 4 Å mol. sieves, CH2Cl2, r.t., 4 h, 66% (2 steps); (b) (i) CH3CN-CH2Cl2-Et2NH (2:1:2), r.t., 2 h; (ii) PamOH, PyBOP, HOBt, DIPEA, CH2Cl2, 4 Å mol. sieves, r.t., 4 h, 80% (2 steps) [Pam = CH3(CH2)14CO].

Synthesis of Alkyne Functionalized Pam3Cys

Our next target was to synthesize a functionalized Toll-like receptor ligand (TLRL) which will serve the purpose of an immunoadjuvant for our vaccine candidate and also anchor the MUC1-Tn conjugate on the surface of the liposome. We focused our attention towards the synthesis of a conjugable form of the lipopeptide S-[(R)-2,3-dipalmitoyloxy-propyl]-N-palmitoyl-(R)-cysteine (Pam3Cys) which has been identified as a TLR-2 agonist and has been successfully used in the past as an immonoadjuvant in the design of three component vaccines.30,31

We planned to incorporate an alkyne functionality through an amide linkage at the C-terminal of Pam3Cys which can be conjugated to an azide moiety on a MUC1-Tn construct by a simple copper-catalyzed ‘click reaction’. To synthesize a conjugatable Pam3Cys alkyne (Scheme 1B), first the tert-butyl protection of O-palmitoylated Fmoc L-cystine tert-butyl ester 430,31 was cleaved by a brief treatment with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). The free acid was coupled with propargyl amine in the presence of benzotriazol-1-yl-oxytripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate (PyBOP), 1-hydroxy-benzotriazole (HOBt) and N,N-Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) to yield 5 (66% over 2 steps).32,33 Finally the Fmoc group in compound 5 was removed by treatment with a mixture of acetonitrile–dichloromethane–diethyl amine (2:1:2) followed by subsequent palmitoylation by coupling with palmitic acid, PyBOP, HOBt and DIPEA to afford our target alkyne functionalized Pam3Cys amide derivative 6 (80% over 2 steps).33,34

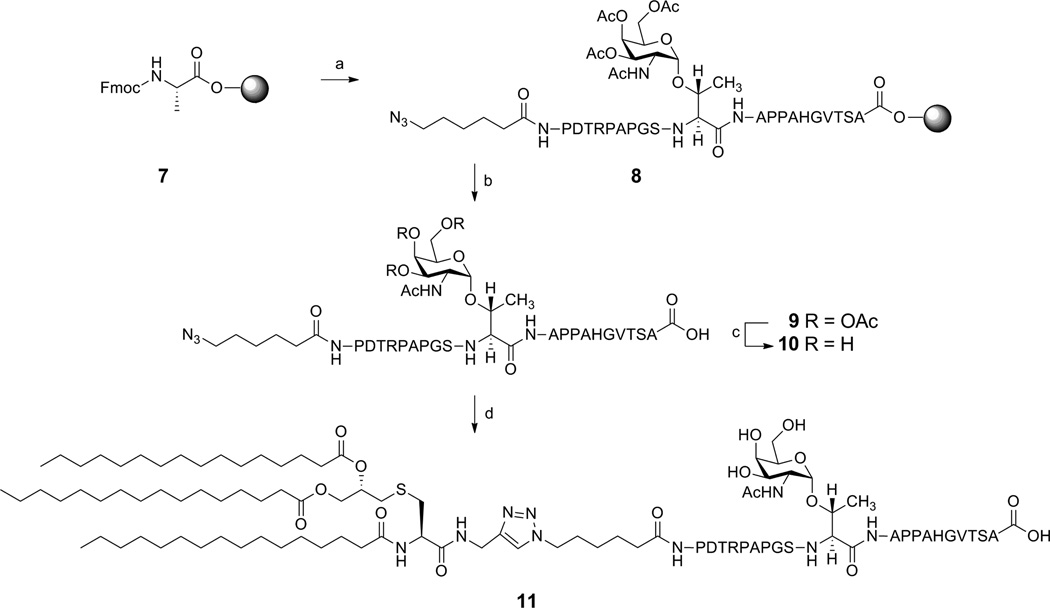

Synthesis of Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn Conjugate

For synthesis of the MUC1-Tn construct, we targeted the 20-amino acid tandem repeat of MUC1 which included the GS(GalNAc-O-T)A epitope identified by Finn et al.12,13 We planned to install a terminal azido group into the glycopeptide which would make the ‘click’ conjugation to the Pam3Cys alkyne feasible. The glycopeptide azide was synthesized by Fmoc strategy on an Omega 396 synthesizer (Advanced ChemTech, Louisville, KY) starting from preloaded Fmoc-L-Ala Wang resin using solid-phase chemistry (Scheme 2). The peptide synthesis was performed by coupling amino acid esters of HOBt using DIC as the coupling agent. A 6-fold excess of Nα-Fmoc amino acid esters of HOBt in NMP were used in the synthesis. A 1:1 ratio of amino acid to DIC was used in all the coupling reactions. Deprotection of Nα-Fmoc group was accomplished by treatment with piperidine in DMF. After the synthesis was complete, the peptide was cleaved from the solid support and deprotected using a modified reagent K cocktail consisting of TFA-thioanisole-ethanedithiol-water-phenol (88:3:5:2:2). The cocktail mixture was filtered through a Quick Snap column, purified by C18 reverse phase HPLC and lyophilized to afford 9. The acetyl groups in compound 9 were deprotected by treatment with 6 mM sodium methoxide in methanol.35 The product was purified by Bio-Gel (P-2, fine 45–90 µm) size exclusion chromatography using deionized water as solvent. Lyophilization of the elutants afforded 10 (100%) as a white powder.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Pam3Cys-MUC-1-Tn Conjugate.a

aReagents and conditions: (a) (i) 25% piperidine, DMF, r.t. 30 min; (ii) HOBt, DIC, NMP, FmocNH-Ser(Ot-Bu)-OH, repeat steps with T, V, G, H, A, P, P, A, T(Ac3GalNAc), S, G, P, A, P, R, T, D, P, 6-azido hexanoic acid; (b) 88% TFA, 3% thioanisole, 5% ethanedithiol, 2% water and 2% phenol; (c) NaOMe, MeOH, r.t., 2 h, 100%; (d) 6, CuSO4.5H2O, Na-ascorbate, TBTA, water-methanol-THF (1:1:2), r.t., 40 h, (100%).

Our next challenge was the conjugation of alkyne functionalized Pam3Cys derivative 6 with the glycopeptide azide 10. Our initial efforts to conjugate the alkyne and the azide fragments via a copper catalyzed ‘click’ reaction using copper sulfate pentahydrate and sodium ascorbate failed. To counteract this problem we used a Cu (I) stabilizing agent tris [(1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl] amine (TBTA) which is known to increase the yield of copper catalyzed click reactions significantly by stabilizing the in situ generated Cu(I) intermediate.36

Conjugation of 10 (1 eqv.) with 6 (3 eqv.) in presence of copper sulfate pentahydrate (12 eqv.), TBTA (12 eqv.) and sodium ascorbate (12 eqv.) in H2O-MeOH-THF (1:1:2) as solvent at ambient temperatures afforded our target Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn conjugate 11 after 40 h. Compound 11 was purified by LH20 using MeOH-dichloromethane (1:1) as solvent. The elutants were lyophilized to afford 11 as a white solid.

Liposome Formulation and Characterization

For the preparation of the liposomes we used 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC). The liposomes were formulated by the extrusion method in a total lipid concentration of 30 mM.37 To test specific antibody binding to the surface-displayed Rha and glycosylated MUC1 epitopes, we prepared three batches of the liposomes. Batch 1 was our positive batch of the liposomes and was formulated with Rha-TEG-cholesterol (10%), Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn 11 (0.69 µM), DPPC (80%) and cholesterol (10%). Batch 2 lacked the surface displayed Rha epitopes and was formulated with Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn 11 (0.69 µM), DPPC (80%) and cholesterol (20%). Batch 3 was our control and was formulated with only DPPC (80%) and cholesterol (20%). Particle size can be an important modulator of the immune response for neutral liposomes.38 Therefore, the homogeneity, stability as well as size characterization of the liposomes were evaluated by scanning electron microscope (SEM) imaging (Figure 2) and dynamic light scatter scattering (DLS) measurements (Figure S1, Supporting Information). All batches of liposomes were found to be stable at 4 °C for 2 days and were around 100 nm in diameter. An antibody binding study showed positive binding of the Batch 1 liposomes with both our previously generated anti-Rha antibodies15 as well as mouse anti-human-MUC1 (CD 227) antibodies using FITC goat anti-mouse IgG/IgM secondary antibodies and fluorescence imaging of the coated liposomes (Figure 3). The binding assay proved that the Rha and the MUC1-Tn epitopes of each conjugate were displayed on the surface of the liposomes. No such antibody binding (both anti-Rha and anti-human MUC1) was observed for the Batch 3 liposomes. Batch 2 liposomes only demonstrated mouse anti-human-MUC1 antibody binding (not shown).

Figure 2.

Size characterization of liposomes: SEM images at 5 kV acceleration voltage (A) Batch 1 liposomes under 50000 × magnification, (B) Batch 1 liposomes under 250000 × magnification.

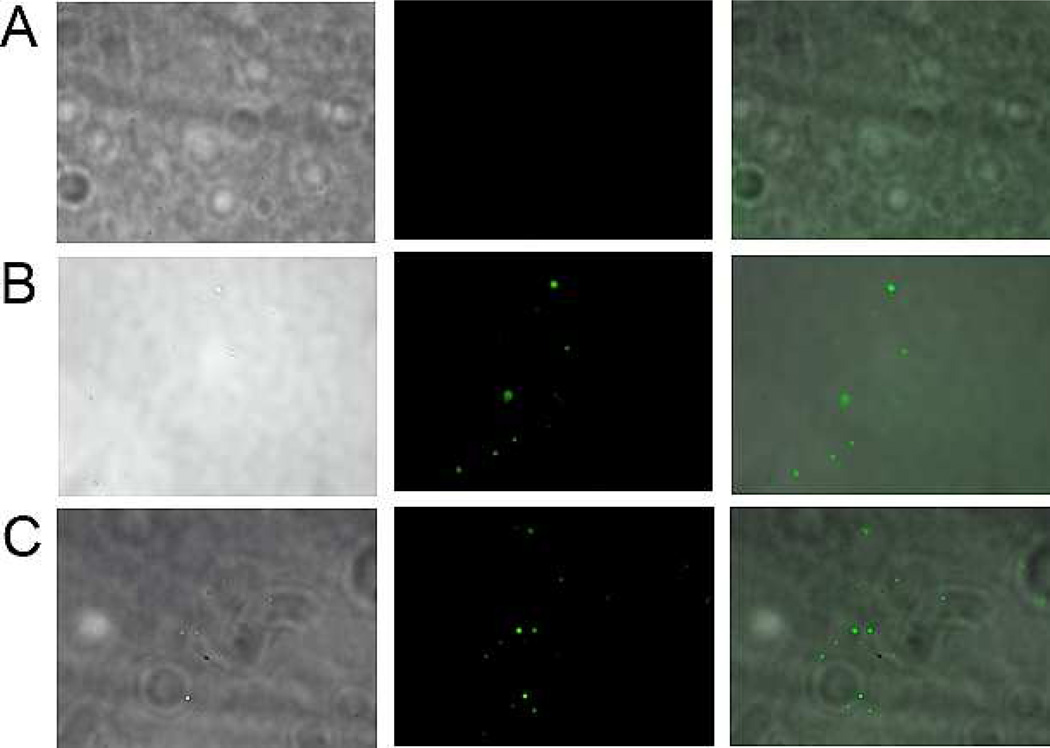

Figure 3.

Fluorescence microscope images with Batch 1 liposomes under 60 × magnification (A) Images with control antibodies (antibodies isolated from pre-immunization serum) 1st, 2nd and 3rd images: brightfield, FITC and overlay; (B) Images with anti-Rha antibodies, 1st, 2nd and 3rd images: brightfield, FITC and overlay; (C) Images with anti-MUC 1 antibodies, 1st, 2nd and 3rd images: brightfield, FITC and overlay.

Synthesis of Rha-Ficoll Conjugate

To evaluate the efficacy of our vaccine in a mouse model we generated mice with anti-Rha antibodies using a Rha-Ficoll immunization. The naive animals do not contain significant amounts of anti-Rha antibodies.21 We were interested in immunizing the mice with a Rha conjugate which would show a minimal T-dependant immune response. We focused our attention on the synthesis of a Rha-Ficoll conjugate since the carrier, Ficoll, has been reported to be excellent for generating a T-independent immune response.39,40 For the synthesis of the Rha-Ficoll conjugate 16 (Scheme 3), tetraacetyl rhamnopyranoside 12 was glycosylated with 2-azido ethanol in presence of boron trifluoride etherate to generate the peracetylated rhamnose 2-azidoethyl glycoside 13 (83 %).41,42 Deacetylation of 13 under Zemplen conditions afforded rhamnose 2-azidoethyl glycoside 14 (86 %) which was reduced by treatment with Pd/charcoal under H2 atmosphere to furnish the rhamnose 2-aminoethyl glycoside 15 (quantitative).43,44 Commercially available Ficoll 400 was oxidized by sodium periodate in acetate buffer (pH 4.7) followed by conjugation with 15 via reductive amination using sodium cyanoborohydride in borate buffer (pH 8.0) to produce Rha-Ficoll conjugate 16.45 The conjugate was purified by filtration through a dialysis tubing with a molecular weight cut off value of 10000 Da. The epitope ratio of 16 was calculated to be 9.44 Rha/Ficoll molecule by hydrolysis of 16 followed by derivatization with 4-amino-N-[2-(diethylamino)ethyl] benzamide (DEAEAB) and comparison of the UV-HPLC peak area with standard curve obtained from DEAEAB derivative of 14 by the methods described by Dalpathado and coworkers.46

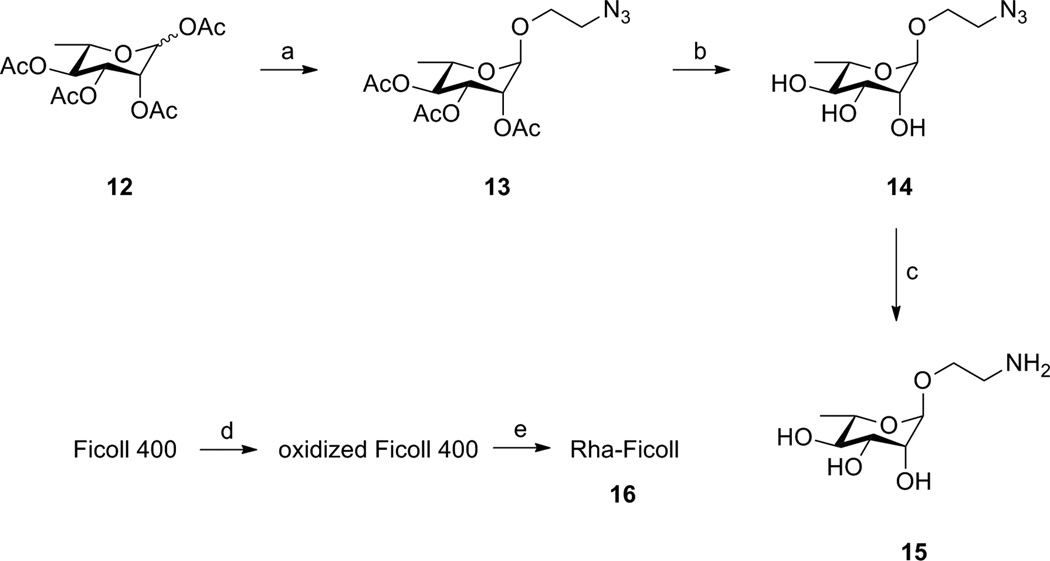

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of Rha-Ficoll Conjugate.a

aReagents and conditions: (a) 2-azidoethanol, BF3.OEt2, CH2Cl2, 0 °C - r.t., 12 h, 83%; (b) NaOMe / MeOH, r.t., 2 h, 86%; (c) H2 / Pd-C / MeOH, 12 h, quantitative; (d) NaIO4, acetate buffer, 2 h; (e) 15, borate buffer, Na(CN)BH3, 12 h, epitope ratio = 9.44 (Rha per Ficoll molecule).

Immunological Results and Discussion

Comparison of Anti-Rha Antibody Titers generated against Rha-Ficoll and Rha-OVA

The first goal of the immunological study was to immunize mice with the Rha-Ficoll conjugate and elicit anti-Rha antibody titers in order to have a model animal that could simulate the naturally occurring anti-Rha antibodies found in human serum. Two groups of five female BALB/c mice each were immunized on day 0 with Rha-Ficoll/Alum adjuvant (group A) or Rha-OVA/complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) (group B). The mice were boosted three more times on days 14, 28 and 42 with either Rha-Ficoll/Alum (group A) or Rha-OVA/incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (ICF) (group B). Sera was collected separately from groups A and B after the 3rd boost and the anti-Rha antibodies in the sera from the two groups of mice were isotyped by screening against Rha-BSA (Figure S2, Supporting Information). The results demonstrated the anti-Rha antibody titers in the Rha-OVA immunized mice groups were 100-fold higher than those from the Rha-Ficoll immunized mice. However, the isotype distribution confirmed that Rha-Ficoll and Rha-OVA produced the anti-Rha antibody subclasses in different proportions. Anti-Rha antibodies from Rha-OVA immunization were dominated by IgG1 (65 %) while Rha-Ficoll immunization produced antibodies which comprised mainly of IgG3 (48 %) and IgM (25%). IgG1 and IgG3 act similarly in that they both stimulate high affinity FcγRI receptors which trigger responses from macrophages.47 However, IgG1 also stimulates low affinity FcγRIIB receptors which inhibit the signals from the FcγRI and B cell receptors thereby diminishing B-cell activity and immunogenicity of macrophages.48 On the other hand the anti-Rha antibody isotypes from Rha-Ficoll immunized mice serum resemble those naturally occurring in the human serum which is presumed to be generated through a T-independent response. Thus, we anticipated that initial immunization with Rha-Ficoll prior to the vaccine challenge will be a more realistic animal model for the human.

T-Cell Proliferation Study

T-cell proliferation assays were performed to determine if the combination of anti-Rha antibodies and Rha-modified liposomal vaccine would potentiate a T-cell proliferative response. In the first part of the study we optimized the proliferation assay conditions. BALB/c mice were immunized (day 0) and boosted (days 14, 28 and 42) with 100 µL emulsions of MUC1-Tn 10/Sigma adjuvant system (SAS) (50 µg peptide per mouse, each injection). The mice were sacrificed (day 49), the spleens were removed and single cell suspensions were prepared and incubated with MUC1-Tn (8.8 × 10−3 – 1.1 µg/mL) alone or with syngeneic bone marrow dendritic cells (DCs) previously pulsed with the same doses of antigen. We observed that DCs enhanced proliferation (Figure S3, Supporting Information), as had been previously observed for C57BL/6 mice.12 To test the ability of anti-Rha antibodies to enhance antigen presentation, spleen cells from BALB/c mice immunized as above were prepared. DCs from BALB/c bone marrow (Supporting Information) were pulsed with the antigen by incubating with Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn + Rha liposomes at antigen concentrations of 8.8 × 10−3 – 0.22 µg/mL together with antibodies isolated from either Rha-Ficoll or Rha-OVA immunized mice or nonimmune mice. The pulsed DCs were added to the spleen cells and proliferation assessed after 3 days. The spleen T-cells proliferated better in presence of anti-Rha antibodies (from both Rha-Ficoll and Rha-OVA immunized mice serum) than in the presence of control serum antibodies over the antigen concentration range of 8.8 × 10−3 – 0.22 µg/mL (Figure 4A). Also the T-cell proliferation was higher in presence of anti-Rha antibodies generated against Rha-Ficoll (6328, 6045 and 6521 counts per minute (cpm) at antigen concentrations of 8.8 × 10−3, 0.044 and 0.22 µg/mL) than those against Rha-OVA (5018, 4926 and 4880 cpm at antigen concentrations of 8.8 × 10−3, 0.044 and 0.22 µg/mL), even though the titer of anti-Rha antibodies was higher in the serum of Rha-OVA immunized mice. The results strongly suggest that the Rha-modified antigen was more effectively internalized and presented by the APCs in the presence of anti-Rha antibodies, particularly those less-inhibitory isotypes characteristic of natural antibodies and generated by Rha-Ficoll immunization. Therefore, we concluded that BALB/c mice in which anti-Rha antibodies are generated with Rha-Ficoll 16 immunization will be an appropriate model for the immunogenicity of the Rha-conjugated MUC1-Tn liposomes.

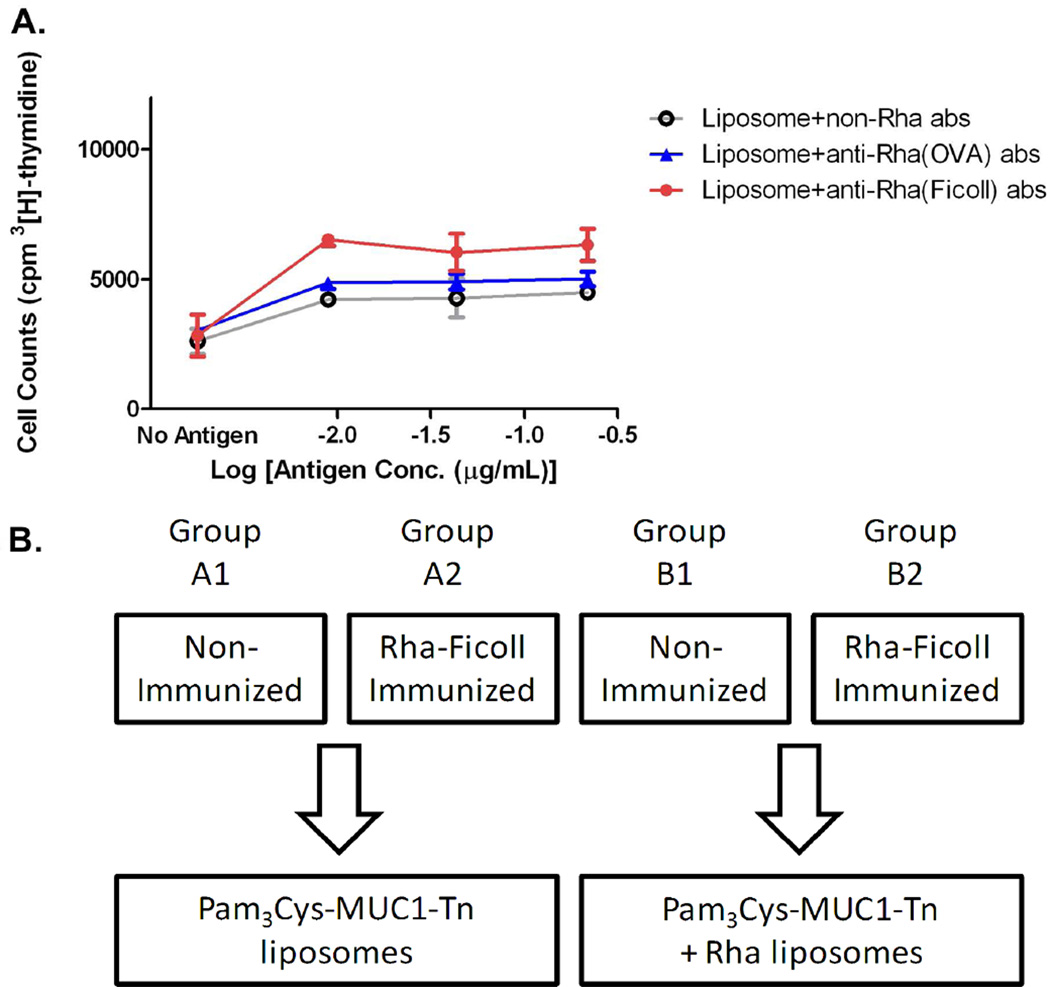

Figure 4.

A) T-cell proliferation measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation in T-cells from mice spleensprimed with MUC1-Tn 10 and challenged with Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn 11 + Rha liposomes in the presence of anti-Rha antibodies (abs) or control abs [anti Rha(OVA) and anti Rha(Ficoll) abs are the antibodies isolated from the serum of Rha-OVA and Rha-Ficoll immunized mice respectively]. B) Stepwise immunization plan. Groups A1, A2, B1 and B2 each represents four groups of female BALB/c mice. Stage I: groups A2 and B2 were immunized with Rha-Ficoll/Alum where as groups A1 and B1 were non-immunized. Stage II: Vaccination; groups A1 and A2 vaccinated and boosted with Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn liposomes where as groups B1 and B2 were vaccinated with Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn + Rha liposomes.

Anti-Rha Antibody Generation

Four groups of five female BALB/c mice each (groups A1, A2, B1 and B2) (6–8 weeks old) were used for this vaccination study. Groups A2 and B2 were immunized (day 0) and boosted (days 14, 28, 42 and 56) with 100 µL equivolume emulsion of Rha-Ficoll (prepared in PBS) and alum adjuvant. Groups A1 and B1 served as the control groups and were deprived of the Rha-Ficoll/Alum immunization (Figure 4B). The mice were bled on day 66 and the ELISA performed by screening the sera from the different groups against Rha-BSA showed that the anti-Rha antibody titers in groups A2 and B2 were 25-fold higher than the control groups (Figure 5A). Thus immunization with Rha-Ficoll confirmed the generation of anti-Rha antibodies in the experimental groups of mice.

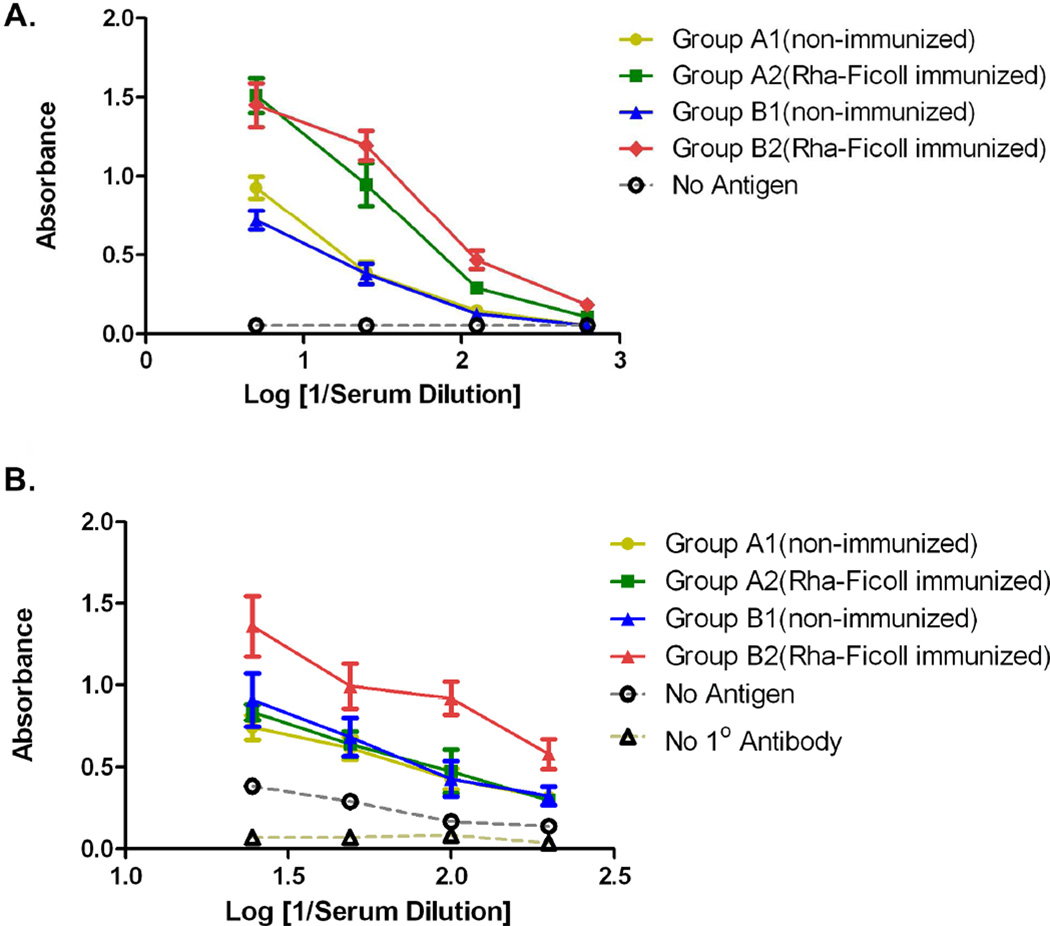

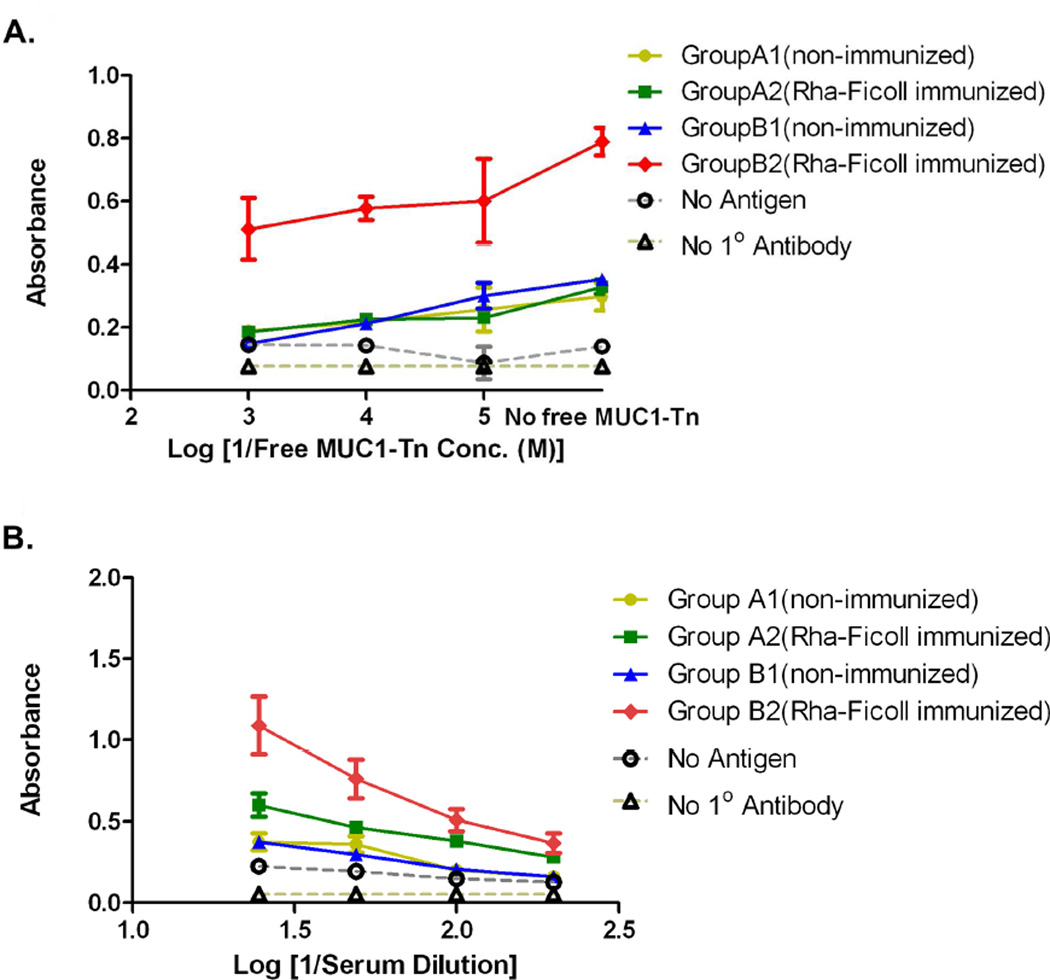

Figure 5.

A) Group average of anti-Rha antibody titers after 4th boost with Rha-Ficoll/Alum. B) Group average of anti-MUC1-Tn antibody titers after 1st boost with Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn liposomes or Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn + Rha liposomes.

Vaccination with Rha and non-Rha-displaying MUC1-Tn Liposomes

Two separate liposomal formulations were prepared. The first contained DPPC, cholesterol and Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn 11 (2 nmol) (Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn liposomes) and the second contained DPPC, cholesterol, Rha-TEG-cholesterol 3 and Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn 11 (2 nmol) (Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn + Rha liposomes). In both formulations the total lipid concentration was 30 mmol. The vaccination was performed on day 77. Groups A1 and A2 were given 100 µL subcutaneous injections of the Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn liposomes (2 nmol of peptide per mouse) and groups B1 and B2 were given 100 µL subcutaneous injections of the Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn + Rha liposome (2 nmol peptide per mouse). The mice were boosted on day 91 with either the Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn liposome (groups A1 and A2, 2 nmol peptide per mouse) or the Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn + Rha liposome (groups B1 and B2). The mice were bled on day 101 and the sera evaluated for anti-MUC1-Tn and anti-Tn antibodies (Figure 5B).

Anti-MUC1-Tn antibody titers were determined by screening the sera against the MUC1-Tn conjugate 10 (Figure 5B). The data showed that groups A1, A2 and B1 had similar absorbance at 1/25, 1/50. 1/100 and 1/200 serum dilutions. This proved that prior immunization with Rha-Ficoll does not affect the response to a non-Rha conjugated vaccine (groups A1 and A2). In addition the Rha epitopes on the vaccine do not alter the inherent immunogenicity of the MUC1-Tn epitopes on the vaccine (groups A1 and B1). The anti-MUC1-Tn titers for group B2 showed an 8-fold increase compared to groups A1, A2 and B1 which was mediated by the anti-Rha antibody-dependent antigen-uptake. Group B2 had an anti-MUC1-Tn titer of approximately 1/300, where titer is defined as the highest dilution giving a signal >0.1 above background. The anti-MUC1-Tn antibodies from each group were isotyped (Figure S4, Supporting Information) which showed that group B2 showed an increase in IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgM isotypes relative to the other 3 groups. The specificity of the antibodies towards MUC1-Tn antigen was determined by a competitive binding experiment (Figure 6A). Serum from every group at 1/100 dilution was incubated with the MUC1-Tn conjugate 10 at concentrations of 0, 10−5, 10−4, and 10−3 M in 0.01 M PBS prior to addition in the ELISA plates coated with the conjugate 10. The absorbances decreased uniformly with increasing concentrations of free MUC1-Tn in the serum dilutions for each group. As an example, the absorbances at 620 nm for the serum dilution of group B2 at free MUC1-Tn concentrations of 0, 10−5, 10−4 and 10−3 M were 0.790, 0.601, 0.577 and 0.512 respectively. These results confirmed the specificity of the anti-MUC1-Tn antibodies towards the respective antigen.

Figure 6.

A) Competitive binding of anti-MUC1-Tn antibodies with bound MUC1-Tn in presence of free MUC1-Tn 10. B) Group average of anti-Tn antibody titer after 1st boost with Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn liposomes or Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn + Rha liposomes.

The antibody titer generated solely against the TACA was determined by screening serum dilutions from every group against a Tn-BSA conjugate (Figure 6B).21 Here also we observed a >8-fold increase in the anti-Tn antibody titers for group B2 in comparison to groups A1, A2 and B1 which was again attributed to the better uptake of the antigen in presence of the anti-Rha antibodies by an antibody-dependant antigen-uptake mechanism. An interesting finding of this study was that the anti-MUC1-Tn antibody titers were higher than the corresponding anti-Tn antibody titers for the same serum dilutions for every group, assuming similar levels of antigen on the plate. As an example, for the group B2 the absorbances at 620 nm for the anti-MUC1-Tn and the anti-Tn measurements at 1/100 serum dilutions were 0.922 and 0.509 respectively. This observation demonstrated that the Rha-displaying MUC1-Tn vaccine successfully generated antibodies against both the MUC1 peptide and the TACA.

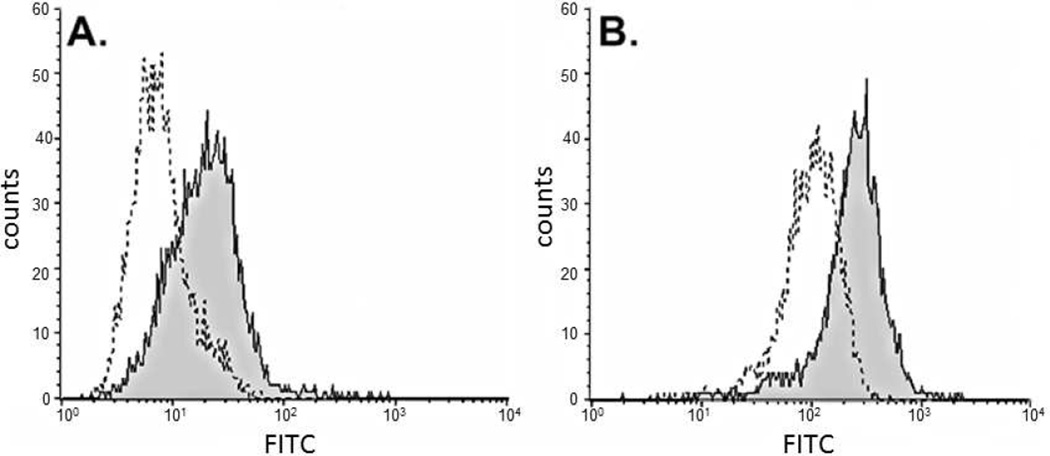

The ability of the anti-MUC1-Tn antibodies in the vaccinated mice serum to bind to MUC1-Tn on human tumor cells was demonstrated with U266 human leukemia cells. These cells express MUC1 on their surface as shown by binding with mouse anti-human MUC1 antibodies (CD 227) (Figure 7A). Serum from group B2 mice also recognized the MUC1 on the tumor cells with similar efficiency as the CD 227 antibodies relative to non-immunized mouse serum (Figure 7B). This demonstrates that the antibodies generated against the glycopeptide recognize the MUC1 protein in its native environment.

Figure 7.

Binding of anti-MUC1-Tn antibodies to human leukemia U266 cells. (A) 2nd antibody alone, ------; with mouse anti-human MUC1 antibodies, ____. (B) with 1/5 dilution of non-immunized mouse serum, ------; with 1/5 dilution of group B2 mice serum, ____

Conclusion

In conclusion a fully synthetic two component vaccine containing the lipopeptide adjuvant Pam3Cys appended to a 20-amino acid MUC1 peptide containing the TACA GalNAc-O-Thr (Tn) was synthesized and was successfully formulated into liposomes along with an Rha cholesterol conjugate. The resulting liposomes were homogenous in size and were stable at 4 °C for two days. Binding studies with both anti-Rha and mouse anti-human MUC1 antibodies revealed that the Rha and the MUC1 glycopeptide epitopes were surface displayed on the liposomes. A Rha-Ficoll conjugate was synthesized for the generation of anti-Rha antibodies in mice. The in vitro proliferation of MUC1-Tn primed mice spleen T-cells showed increased proliferation to Rha-liposomes in the presence of antibodies from Rha-Ficoll immunized mice relative to nonimmune mice. Vaccination studies with Rha- and non-Rha-displaying MUC1-Tn liposomes in mice either non-immunized or immunized with Rha-Ficoll illustrated that anti-MUC1-Tn and anti-Tn antibodies were >8-fold higher in the groups of mice previously immunized with Rha-Ficoll and later vaccinated with the Pam3Cys-MUC1-Tn + Rha liposomes. The anti-MUC1-Tn antibodies in the serum of the vaccinated mice recognized the aberrant MUC1 on human leukemia U266 cells. Overall this vaccine successfully triggered both T cell and humoral immunity enhanced by anti-Rha antibody dependant antigen uptake. Because this vaccine uses separate rhamnose and antigenic epitope components, the vaccine can easily be targeted to different antigens or epitopes by changing the peptide without having to change the other components.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by an Interdisciplinary Research Initiation grant from The University of Toledo and a grant from the National Institutes of Health (grant number GM094734) to S.J.S and K.A.W. SEM data was obtained on instrumentation acquired through National Science Foundation grant number 0840474.

Footnotes

Associated Content

Supporting Information. Experimentals for comparison of anti-Rha antibodies generated against Rha-Ficoll versus Rha-OVA and the T-cell proliferation study to test the T cell response in BALB/c mice against the MUC1-Tn glycopeptide. Copies of 1H, 13C, 1H gcosy NMR spectras and HRMS data of compounds 2, 3, 5, 6, 13 and 14, MALDI-TOF spectra of 9, 10 and 11 and ESIMS of 15. DLS measurement graphs for batch 1 and 2 liposomes and buffer. Figures of anti-Rha and anti-MUC1-Tn antibody isotype titers and T-cell proliferation in BALB/c mice with MUC1-Tn peptide in presence and absence of dendritic cells. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Livingston PO, Wong GY, Adluri S. Improved survival in stage III melanoma patients with GM2 antibodies: A randomized trial of adjuvant vaccination with GM2 ganglioside. J. Clin. Oncol. 1994;12:1036–1044. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.5.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solvin SF, Keding SJ, Raghupati G. Carbohydrate vaccines as immuno-therapy for cancer. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2005;83:418–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raghupati G, Damani P, Srivastava G, Srivastava O, Sucheck SJ, Ichikawa Y, Livingson PO. Synthesis of sialyl Lewisa (sLea, CA19-9) and construction of an immunogenic sLea vaccine. Can. Immunol. Immunother. 2009;58:1397–1405. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0654-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emens LA, Reilly RT, Jaffee EM. Breast cancer vaccines: Maximizing cancer treatment by tapping into host immunity. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer. 2005;12:1–17. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dziadek S, Kowalczyk D, Kunz H. Synthetic vaccines consisting of tumor-associated MUC1 glycopeptide antigens and bovine serum albumin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:7624–7630. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raghupati G, Koide F, Livingston PO, Cho YS, Endo A, Wan Q, Spassove MK, Keding SJ, Allen J, Ouerfelli O, Wilson RM, Danishefsky SJ. Preparation and evaluation of unimolecular pentavalent and hexavalent antigenic constructs targeting prostate and breast cancer: A synthetic route to anticancer vaccine candidates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:2715–2725. doi: 10.1021/ja057244+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffmann-Roder A, Johannes M. Synthesis of a MUC1-glycopeptide–BSA conjugate vaccine bearing the 3′-deoxy-3′-fluoro-Thomsen–Friedenreich antigen. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:9903–9905. doi: 10.1039/c1cc13184b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lakshminarayanana V, Thompson P, Wolfert MA, Buskas T, Bradley JM, Pathangey LB, Madsen CS, Cohen PA, Gendler SJ, Boons G-J. Immune recognition of tumor-associated mucin MUC1 is achieved by a fully synthetic aberrantly glycosylated MUC1 tripartite vaccine. Proc. Natl. Acad. SciU.SA. 2012;109:261–266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115166109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patton S, Gendler SJ, Spicer AP. The epithelial mucin, MUC1, of milk, mammary gland and other tissues. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1241:407–423. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(95)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Springer GF. T and Tn, general carcinoma autoantigens. Science. 1984;224:1198–1206. doi: 10.1126/science.6729450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanisch FG, Stadie TR, Deutzmann F, Peter-Katalanic J. MUC1 glycoforms in breast cancer. Cell line T47D as a model for carcinoma-associated alterations of O-glycosylation. EurJBiochem. 1996;236:318–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan SO, Vlad AM, Islam K, Gariepy J, Finn OJ. Tumor-associated MUC1 glycopeptide epitopes are not subject to self-tolerance and improve responses to MUC1 peptide epitopes in MUC1 transgenic mice. Biol. Chem. 2009;390:611–618. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryan SO, Turner MS, Gariepy J, Finn OJ. Tumor antigen epitopes interpreted by the immune system as self or abnormal-self differentially affect cancer vaccine responses. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5788–5796. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galili U, LaTemple DC. Natural anti-Gal antibody as a universal augmenter of autologous tumor vaccine immunogenicity. Immunol. Today. 1997;18:281–285. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)80024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdel-Motal UM, Wigglesworth K, Galili U. Mechanism for increased immunogenicity of vaccines that form in vivo immune complexes with the natural anti-Gal antibody. Vaccine. 2009;27:3072–3082. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdel-Motal U, Guay HM, Wigglesworth K, Welsh RM, Galili UJ. Immunogenicity of influenza virus vaccine is increased by anti-Gal-mediated targeting to antigen-presenting cells. J. Virology. 2007;81:9131–9141. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00647-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdel-Motal U, Wang S, Lu S, Wigglesworth K, Galili U. Increased immunogenicity of human immunodeficiency virus gp120 engineered to express Galα1-3Galβ1-4GlcNAc-R epitopes. J. Virology. 2006;80:6943–6951. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00310-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huflejt ME, Vuskovic M, Vasiliu D, Xu H, Obukhova P, Shilova N, Tuzikov A, Galanina O, Arun B, Lu K, Bovin N. Anti-carbohydrate antibodies of normal sera: Findings, surprises and challenges. Mol. Immunol. 2009;46:3037–3049. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oyelaran O, McShane LM, Dodd L, Gildersleeve JC. Profiling human serum antibodies with a carbohydrate antigen microarray. J. Proteome Res. 2009;8:4301–4310. doi: 10.1021/pr900515y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen W, Gu L, Zhang W, Motari E, Cai L, Styslinger TJ, Wang PG. l-Rhamnose antigen: A promising alternative to α-Gal for cancer immunotherapies. ACS Chem. Biol. 2011;6:185–191. doi: 10.1021/cb100318z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarkar S, Lombardo SA, Herner DN, Talan RS, Wall KA, Sucheck SJ. Synthesis of a single-molecule l-rhamnose-containing three-component vaccine and evaluation of antigenicity in the presence of anti-l-rhamnose antibodies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:17236–17246. doi: 10.1021/ja107029z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ignatitus R, Mahnke K, Riveria M, Hong K, Isdell F, Steinman RM, Pope M, Stamatatos L. Presentation of proteins encapsulated in sterically stabilized liposomes by dendritic cells initiates CD8+ T-cell responses in vivo. Blood. 2000;96:3505–3513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foged C, Arigita C, Sundblad A, Jiskoot W, Storm G, Frokjaer S. Interaction of dendritic cells with antigen-containing liposomes: Effect of bilayer composition. Vaccine. 2004;22:1903–1913. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mallick AI, Sinha H, Chaudhuri P, Nadeem A, Khan SA, Dar KA, Owasis M. Liposomised recombinant ribosomal L7/L12 protein protects BALB/c mice against Brucella abortus 544 infection. Vaccine. 2007;25:3692–3704. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jerome V, Graser A, Muller R, Kontermann RE, Konur A. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes responding to low dose TRP2 antigen are induced against B16 melanoma by Lliposome-encapsulated TRP2 peptide and CpG DNA adjuvant. J. Immunother. 2006;29:294–305. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000199195.97845.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arika S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signaling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armarego WLC, Christina CLL. Purification of Laboratory Chemicals. 5th Ed. New York: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2003. pp. 80–388. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bardonnet P-L, Faivre V, Pirot F, Boullanger P, Falson F. Cholesteryl oligoethyleneglycol glycosides: Fluidizing effect of their embedment into phospholipid bilayers. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;329:1186–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masuda T, Akita H, Niikura K, Nishio T, Ukawa M, Enoto K, Danev R, Nagayama K, Ijiro K, Harashima H. Envelope-type lipid nanoparticles incorporating a short PEG-lipid conjugate for improved control of intracellular trafficking and transgene transcription. Biomaterials. 2009;30:4806–4814. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeng W, Ghosh S, Lau YF, Brown LE, Jackson DC. Highly immunogenic and totally synthetic lipopeptides as self-adjuvanting immunocontraceptive vaccines. J. Immunol. 2002;169:4905–4912. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buskas T, Ingale S, Boons G-J. Towards a fully synthetic carbohydrate-based anticancer vaccine: Synthesis and immunological evaluation of a lipidated glycopeptide containing the tumor-associated Tn antigen. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:5985–5988. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Metzger JW, Wiesmuller K-H, Jung G. Synthesis of Nα-Fmoc protected derivatives of S-(2,3-dihydroxypropyl)-cysteine and their application in peptide synthesis. Int. J. Peptide Protein Res. 1991;38:545–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1991.tb01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Høeg-Jensen T, Jakobsen MH, Holm A. A new method for rapid solution synthesis of shorter peptides by use of (benzotriazolyloxy)tripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate (PyBOP) Tet. Lett. 1991;32:6387–6390. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pettit GR, Lippert JW, III, Taylor SR, Tan R, Williams MD. Synthesis of phakellistatin 11: A Micronesia (Chuuk) marine sponge cyclooctapeptide. J. Nat. Prod. 2001;64:883–891. doi: 10.1021/np0100441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reichel F, Ashton P, Boons G-J. Synthetic carbohydrate-based vaccines: Synthesis of an L-glycero-D-manno-heptose antigen-T-epitope-lipopeptide conjugate. Chem. Commun. 1997;21:2087–2088. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamada T, Peng CG, Matsuda S, Addepalli H, Jayaprakash KN, Alam MR, Mills K, Maier MA, Charisse K, Sekine M, Manoharan M, Rajeev KG. versatile site-specific conjugation of small molecules to siRNA using click chemistry. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:1198–1211. doi: 10.1021/jo101761g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oslon F, Hunt CA, Szoka FC, Vail WJ, Papahadjopoulos D. Studies on the biosynthesis of sulfolipids in the diatom Nitzschia alba. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1979;557:9–23. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(79)90230-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brewer JM, Tetley L, Richmond J, Liew FY, Alexander J. Lipid vesicle size determines the Th1 or Th2 response to entrapped antigen. J. Immunol. 1998;161:4000–4007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharon R, McMaster PRB, Kask AM, Owens JD, Paul WE. DNP [2,4-dinitrophenyl]-Lys-Ficoll, a T-independent antigen which elicits both IgM and IgG anti-DNP antibody-secreting cells. J. Immunol. 1975;114:1585–1589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inman JK. Thymus-independent antigens. Preparation of covalent, hapten-Ficoll conjugates. J. Immunol. 1975;114:704–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Norberg O, Deng L, Yan M, Ramström O. Photo-click immobilization of carbohydrates on polymeric surfaces—A quick method to functionalize surfaces for biomolecular recognition studies. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009;20:2364–2370. doi: 10.1021/bc9003519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu J, Zhu X, Kang ET, Neoh KG. Design and synthesis of star polymers with hetero-arms by the combination of controlled radical polymerizations and click chemistry. Polymer. 2007;48:6992–6999. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen L, Li J, Luo C, Liu H, Xu W, Chen G, Liew OW, Zhu W, Puah CM, Shen X, Jiang H. Binding interaction of quercetin-3-β-galactoside and its synthetic derivatives with SARS-CoV 3CLpro: Structure-activity relationship studies reveal salient pharmacophore features. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;14:8295–8306. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ni J, Singh S, Wang L-X. Synthesis of maleimide-activated carbohydrates as chemoselective tags for site-specific glycosylation of peptides and proteins. Bioconjugate Chem. 2003;14:232–238. doi: 10.1021/bc025617f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sundaram PV, Venkatesh R. Retardation of thermal and urea induced inactivation of α-chymotrypsin by modification with carbohydrate polymers. Protein Eng. 1998;11:699–705. doi: 10.1093/protein/11.8.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dalpathado DS, Jiang H, Kater MA, Desaire H. Reductive amination of carbohydrates using NaBH(OAc)3. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2005;381:1130–1137. doi: 10.1007/s00216-004-3028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gavin A, Barns N, Dijstelbloem H, Hogarth M. Identification of the mouse IgG3 receptor: Implications for antibody effector function at the interface between innate and adaptive immunity. J. Immunol. 1998;160:20–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D'Ambrosio D, Hippenst KL, Minskoff SA, Mellman I, Pani G, Siminovitch KA, Cambier JC. Recruitment and activation of PTP1C in negative regulation of antigen receptor signaling by FcγRIIB1. Science. 1995;268:293–297. doi: 10.1126/science.7716523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.