Abstract

Background

Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs), characterized by impaired social interactions and deficits in verbal and nonverbal communication, are thought to affect 1 in 88 children in the United States. There is much support for the role of growth factors in the etiology of autism. Recent research has shown that epithelial growth factor (EGF) is decreased in young autistic children (2–4 years of age). This study was designed to determine plasma levels of EGF in an older group of autistic children (mean age 10.6 years) and to correlate these EGF levels with putative biomarkers HGF, uPA, uPAR, GAD2, MPO GABA, and HMGB1, as well as symptom severity of 19 different symptoms.

Subjects and methods

Plasma from 38 autistic children, 11 children with pervasive developmental disorder (PDD-NOS) and 40 neurotypical, age and gender similar controls was assessed for EGF concentration using ELISAs. Severity of 19 symptoms (awareness, expressive language, receptive language, (conversational) pragmatic language, focus/attention, hyperactivity, impulsivity, perseveration, fine motor skills, gross motor skills, hypotonia (low muscle tone), tiptoeing, rocking/pacing, stimming, obsessions/fixations, eye contact, sound sensitivity, light sensitivity, and tactile sensitivity) was assessed and then compared to EGF concentrations.

Results

In this study, we found EGF levels in autistic children and those with PDD-NOS to be significantly lower when compared with neurotypical controls. EGF levels correlated with HMGB1 levels but not the other tested putative biomarkers, and EGF correlated negatively with hyperactivity, gross motor skills, and tiptoeing but not other symptoms.

Conclusions

These results suggest an association between decreased plasma EGF levels and selected symptom severity. We also found a strong correlation between plasma EGF and HMGB1, suggesting inflammation is associated with decreased EGF.

Keywords: EGF, HMGB1, GABA, autism, PDD, symptom severity

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) comprise a complex and heterogeneous group of pathological conditions characterized by impaired social interactions, deficits in verbal and nonverbal communication, and a limited interest in the surrounding environment associated with stereotyped and repetitive behaviors.1

Growth factors regulate the processes of neuronal growth, differentiation, and proliferation, as well as regulating neuronal survival, neuronal migration, and the formation or elimination of synapses.2 They have also been found to be immune modulators.3–6 Studies indicate that there is immune dysfunction in the nervous system7–11 in children with autism and this abnormal function may be associated with dysregulation of growth factor activity.

In the central nervous system (CNS), epithelial growth factor (EGF) plays an important role in controlling proliferation and differentiation of nervous tissue during neurogenesis.12 It also promotes wound healing.14

Studies have shown a possible association between EGF and autism. An increased frequency of EGF single nucleotide polymorphisms has been reported in children with autism.16 Lower plasma EGF levels have been found in adults with autism,15 but in one report where EGF was measured in serum in 27 autistic children and 28 age-matched normal controls, children with autism had increased levels of EGF.13 Another report recently found decreased EGF levels in the plasma of 49 children 2 to 4 years of age with ASD.27

High mobility group box-1 (HMGB1) has been shown to be a key mediator of inflammatory diseases. It is a nuclear protein that triggers inflammation, binds to lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and IL-1, and initiates and synergizes with a Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4-mediated pro-inflammatory response.17 After proinflammatory stimulation, such as that by LPS, TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8, HMGB1 is actively released from activated monocytes and macrophages. Regulation of HMGB1 secretion is important for control of HMGB1-mediated inflammation and is dependent on various processes such as phosphorylation by calcium-dependent protein kinase C,18 as well as acetylation and methylation.19 In a recent study, HMGB1 and TLR4 were involved in the generation and recurrence of seizures in experimental animals.20,21

This study was designed to determine plasma levels of EGF in an older group of children with autism (mean age 10.6 years), as well as children classified as PDD-NOS, and correlate these EGF levels with putative biomarkers HGF, uPA, uPAR, GAD2, GABA, and HMGB1. We also compared EGF levels with symptom severity of 19 different symptoms.

Materials and Methods

ELISA was used to measure plasma EGF, HMGB1, GABA and other putative biomarkers (ELISA kits, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN and USCN Life Sciences, Wuhan, China).

All reagents and specimens were equilibrated to room temperature before the assay was performed. A 1:51 dilution of the patient samples was prepared by mixing 10 μL of the patient’s plasma with 0.5 mL of plasma diluent. One hundred microliters of calibrators (20–200 Eu/ml antibodies), positive and negative control plasma, plasma diluent alone, and diluted patient samples were added to the appropriate microwells of a microculture plate (each well contained affinity purified polyclonal IgG to HGF or GABA). Wells were incubated for 60 minutes (±5 minutes) at room temperature, then washed 4 times with wash buffer. One hundred microliters of prediluter antihuman IgG conjugated with HRP was added to all microwells, incubated for 30 minutes (±5 minutes) at room temperature, then washed 4 times with wash buffer. One hundred microliters of enzyme substrate was added to each microwell. After approximately 30 minutes at room temperature, the reaction was stopped by adding 50 μL of 1 M sulfuric acid, then the wells were read at 405 nm with an ELISA reader (BioRad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

Serums

All experimental and control serums were treated in an identical fashion, that is, frozen at −70°C immediately after collection and cell/serum separation, then stored at −70°C until thawed for use in ELISAs.

Subjects

Plasma from 38 autistic children, 11 children with pervasive developmental disorder (PDD-NOS) and 40 neurotypical, age and gender similar controls was assessed for EGF plasma concentration using ELISAs.

It should be noted that the diagnostic criteria used in this study (children with autism and pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified [PDD-NOS]) are defined by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) criteria. In 2012, the separate diagnostic labels of autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, and PDD-NOS were replaced by one umbrella term, autism spectrum disorder.

Plasma from consecutive individuals with diagnosed autism (n = 38; 32 male; mean age 10.6 years), pervasive developmental disorder (PDD) (n = 11; 8 male; mean age 10.9 years) and controls (n = 40; 36 male; mean age 9.5 years) were all obtained from patients presenting at the Health Research Institute/Pfeiffer Treatment Center, a comprehensive treatment and research center, specializing in the care of with neurological disorders, including autism. Neurotypical control serums, were obtained from the Autism Genetic Resource Exchange (AGRE), a repository of biomaterials and phenotypic and genotypic data to aid research on autism spectrum disorders. The autistic individuals met the DSM-IV criteria, and many were diagnosed using The Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) before presenting for treatment at the Pfeiffer Treatment Center.

Patient consent was obtained from all patients involved in this study, and this study was approved by the institutional review board of the Health Research Institute/Pfeiffer Treatment Center.

Severity of disease

An autism symptom severity questionnaire was used to evaluate symptoms. The questionnaire (Pfeiffer Questionnaire) asked parents or caregivers to assess the severity of the following symptoms: awareness, expressive language, receptive language, (conversational) pragmatic language, focus, attention, hyperactivity, impulsivity, perseveration, fine motor skills, gross motor skills, hypotonia (low muscle tone), tiptoeing, rocking/pacing, stimming, obsessions/fixations, eye contact, sound sensitivity, light sensitivity, and tactile sensitivity. The symptoms were rated by parents/guardians on a scale of 0 to 5 (5 being the highest severity) for each of these behaviors.

Statistics

Inferential statistics were derived from unpaired t test and odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. ANOVA was used to assess variance between groups. Pearson moment correlation test was used to establish degree of correlation between groups.

Results

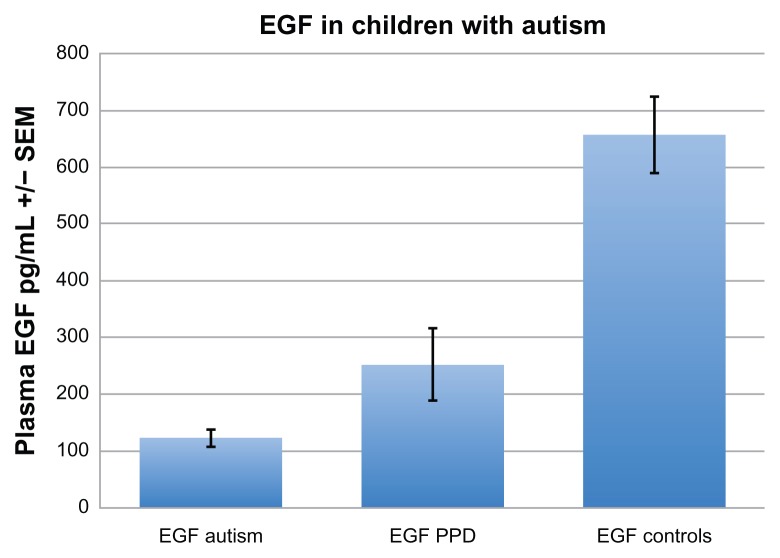

In this study, we found that plasma levels of EGF in children with autism (m = 122 ± 94 pg/mL) and those with PDD-NOS (m = 252 ± 212 pg/mL) were significantly lower when compared with neurotypical controls (m = 656 ± 419 pg/mL) (ANOVA, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Plasma levels of EGF in children with autism (m = 122 ± 94 pg/mL), and those with PDD-NOS (m = 252 ± 212 pg/mL), established using ELISAs, were significantly lower when compared to neurotypical controls (m = 656 ± 419 pg/mL).

Note: ANOVA, P < 0.0001.

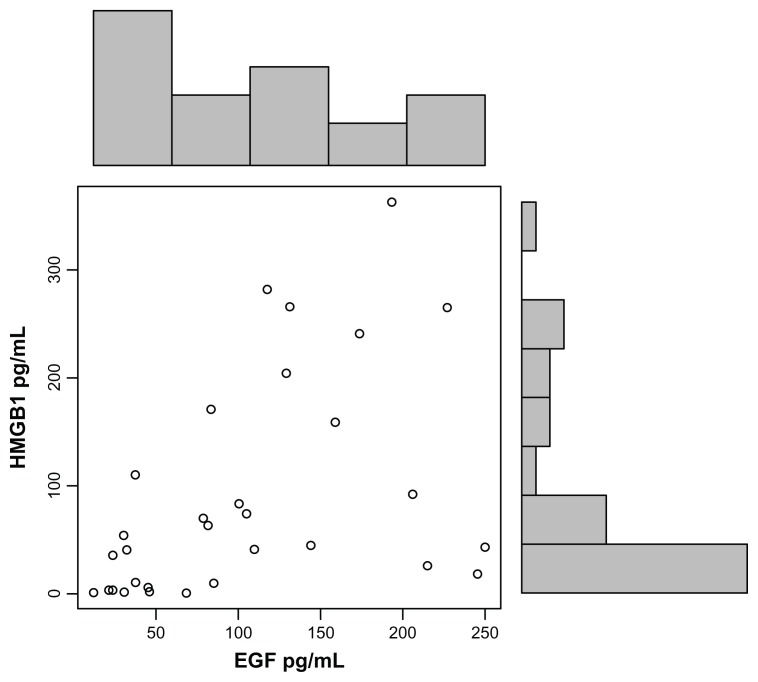

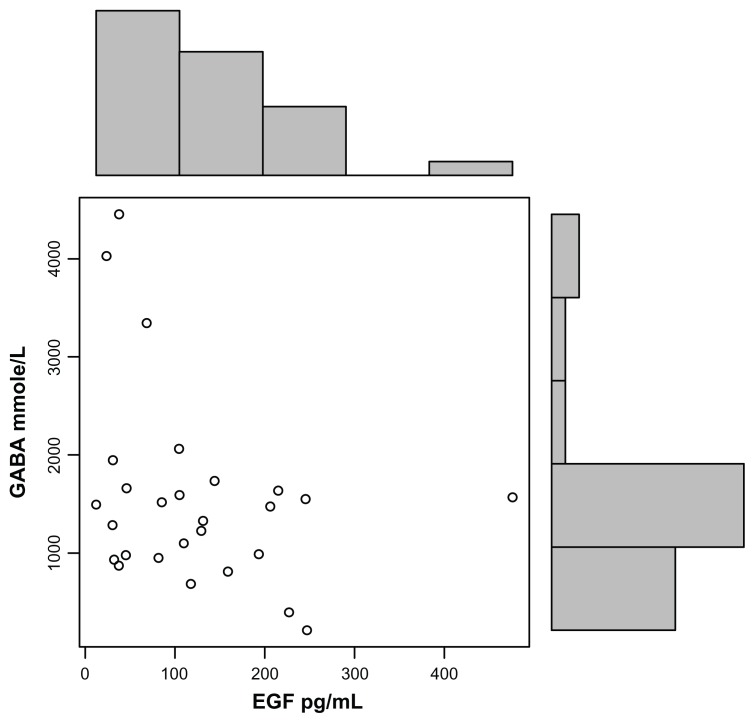

EGF levels correlated with HMGB1 levels (r = 0.5; P = 0.009) (Fig. 2) and GABA (r −0.3; P = 0.06) (Fig. 3), but not the other tested putative biomarkers, and EGF correlated negatively with hyperactivity (r = −0.32; P = 0.04), gross motor skills (r = −0.37; P = 0.02) and tip toeing (r = −0.37; P = 0.02), but not the other symptoms.

Figure 2.

Plasma EGF concentrations, established using ELISAs, correlate with HMGB1 in autistic children (r = 0.5; P = 0.009).

Note: Each data point (o) represents EGF and HMGB1 plasma values of an individual child with autism.

Figure 3.

High plasma EGF concentrations, established using ELISAs, correlate with low GABA in autistic children (r = −0.3; P = 0.06).

Note: Each data point (o) represents EGF and GABA plasma values of an individual child with autism.

Discussion

EGF is involved in growth and differentiation of cells of the CNS and the gastrointestinal tract. The growth factor has been found to cause proliferation, differentiation, and migration of neural progenitor cells and is associated with the differentiation of these cells into astrocytes and neurons.22 EGF appears to be necessary for normal development of intestinal mucosa. Mice deficient in EGF receptor suffer from symptoms similar to necrotizing enterocolitis,23 and EGF promotes wound healing in animal models of ulcerative colitis.24 Recently, EGF has been shown to have antiinflammatory effects on the immature human intestine.25

Increased serum levels of HMGB1 protein have been found in patients with autistic disorder.26 We have also found significantly increased plasma HMGB1 in our autistic group (P = 0.02; unpublished data).

In this study, we have found significantly decreased EGF plasma levels, which correlate with increased HMGB1 levels, as well as increased hyperactivity symptoms, in autistic children. We also found that children with PDD had significantly lower EGF when compared with controls. These levels were not, however, as low as the EGF plasma levels. Because PDD-NOS individuals were diagnosed (DSM-IV) with symptoms less severe than symptoms of children with autism, this suggests a relationship between decreased EGF and severity of disease.

We previously reported that autistic children (mean age of approximately 10 years) with severe gastrointestinal (GI) disease had significantly decreased levels of HGF.26 The same autistic group had significantly increased plasma levels of GABA and HGF levels correlated with increased GABA levels, but these concentrations did not correlate significantly with any symptom severity (unpublished data). Since the results of this report suggest that EGF correlates with hyperactivity related symptoms, and HGF does not correlate with symptoms, it is reasonable to suggest that EGF is more important than HGF as a putative biomarker.

GABA is the most abundant inhibitory neurotransmitter in the mammalian brain, where it is widely distributed.29 HGF has been shown to modulate GABAergic activity28 and enhance NMDA currents in the hippocampus.30 uPAR encodes an urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) which is required for the proper processing of the HGF.28 GABA is released by interneurons, which contain the GABA synthesizing enzymes glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 (GAD2) and GAD67. These enzymes convert glutamate into GABA.31 We found a correlation between decreased EGF and increased GABA in children with autism. However, we did not find any correlation between EGF levels and any of these GABA modulatory molecules. This suggests that EGF deficiency may not be associated with HGF or glutamate processing to GABA formation in children with autism.

Recent findings that immune cells synthesize GABA and have the machinery for GABA catabolism, and that antigen-presenting cells (APCs) express functional GABA receptors and respond electrophysiologically to GABA, suggest that the immune system harbors all of the necessary constituents for GABA signaling and GABA itself may function as a paracrine or autocrine factor.32 Our data suggest higher inflammation (HMGB1) and higher GABA plasma levels in autistic children. It is possible that inflammatory cells, resulting from increased inflammation, are involved in the increased synthesis of GABA. Since decreased EGF has been associated with inflammatory conditions such as colitis23,24 and has been shown to have antiinflammatory effects,25 it is reasonable to suggest that low EGF could be associated with high inflammation in children with autism. Therefore, we suggest that increased GABA may be the result of decreased EGF, which results, in turn, in increased inflammation in children with autism.

We did not find a significant difference in plasma EGF levels between autistic children with GI disease and children without GI disease (unpublished data). This suggests that decreased EGF may be associated with increased inflammation but not necessarily with increased inflammation often associated with GI disease in children with autism.

We also found that decreased EGF is associated with hyperactivity, the tendency for tiptoeing and decreased gross motor skills in children with autism. Because of this, we suggest that EGF may play a significant role in the etiology of abnormal behavior in at least a subpopulation of autistic children.

In summary, our data support recent findings that EGF plasma levels in children with autism are significantly decreased.27 We suggest that decreased EGF is associated with increased plasma GABA levels, possibly through increased inflammation, but not with GABA modulatory biomarkers related to HGF (uPAR, uPA) or GAD. We also suggest that EGF may play a significant role in the etiology of abnormal behavior in children with autism.

Abbreviations

- EGF

Epidermalgrowthfactor

- HGF

hepatocytegrowthfactor

- GABA

Gamma-Aminobutyric acid

- GAD

glutamic acid decarboxylase

- uPA

urokinase plasminogen activator

- uPAR, PAUR

urokinase plasminogen activator receptor

- ELISA

enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- c-Met

MET or MNNG HOS Transforming gene

- PDD

pervasive developmental disorder

Footnotes

Author Contributions

AR carried out the immunoassays, participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. AR conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination. AR drafted and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

Author(s) disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

Disclosures and Ethics

As a requirement of publication the author has provided signed confirmation of compliance with ethical and legal obligations including but not limited to compliance with ICMJE authorship and competing interests guidelines, that the article is neither under consideration for publication nor published elsewhere, of their compliance with legal and ethical guidelines concerning human and animal research participants (if applicable), and that permission has been obtained for reproduction of any copyrighted material. This article was subject to blind, independent, expert peer review. The reviewers reported no competing interests.

Funding

The author would like to acknowledge the financial support from the Autism Research Institute and the resources provided by the Autism Genetic Resource Exchange (AGRE) Consortium and the participating AGRE families. The Autism Genetic Resource Exchange is a program of Autism Speaks and is supported, in part, by grant 1U24MH081810 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Clara M. Lajonc.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DMS-IV-TR) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nickl-Jockschat T, Michel TM. The role of neurotrophic factors in autism. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:478–90. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heck DE, Laskin DL, Gardner CR, Laskin JD. Epidermal growth factor suppresses nitric oxide and hydrogen peroxide production by keratinocytes. Potential role for nitric oxide in the regulation of wound healing. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21277–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okunishi K, Dohi M, Nakagome K, et al. A novel role of hepatocyte growth factor as an immune regulator through suppressing dendritic cell function. J Immunol. 2005;175:4745–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vega JA, García-Suárez O, Hannestad J, Pérez-Pérez M, Germanà A. Neurotrophins and the immune system. J Anat. 2003;203:1–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2003.00203.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabakman R, Lecht S, Sephanova S, Arien-Zakay H, Lazarovici P. Interactions between the cells of the immune and nervous system: neurotrophins as neuroprotection mediators in CNS injury. Prog Brain Res. 2004;146:387–401. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(03)46024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vargas DL, Nascimbene C, Krishnan C, Zimmerman AW, Pardo CA. Neuroglial activation and neuroinflammation in the brain of patients with autism. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:67–81. doi: 10.1002/ana.20315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li X, Chauhan A, Sheikh AM, et al. Elevated immune response in the brain of autistic patients. J Neuroimmunol. 2009;207:111–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashwood P, Krakowiak P, Hertz-Picciotto I, Hansen R, Pessah I, Van de Water J. Elevated plasma cytokines in autism spectrum disorders provide evidence of immune dysfunction and are associated with impaired behavioral outcome. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:40–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enstrom AM, Onore CE, Van de Water JA, Ashwood P. Differential monocyte responses to TLR ligands in children with autism spectrum disorders. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xian CJ, Zhou XF. Roles of transforming growth factor-α and related molecules in the nervous system. Mol Neurobiol. 1999;20:157–83. doi: 10.1007/BF02742440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Işeri E, Güney E, Ceylan MF, et al. Increased serum levels of epidermal growth factor in children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41(2):237–41. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pastore S, Mascia F. Novel acquisitions on the immunoprotective roles of the EGF receptor in the skin. Expert Rev Dermatol. 2008;3:525–7. doi: 10.1586/17469872.3.5.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toyoda T, Nakamura K, Yamada K, et al. SNP analyses of growth factor genes EGF, TGFβ-1, and HGF reveal haplotypic association of EGF with autism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;360:715–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki K, Hashimoto K, Iwata Y, et al. Decreased serum levels of epidermal growth factor in adult subjects with high-functioning autism. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:267–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Youn JH, Oh YJ, Kim ES, Choi JE, Shin JS. High mobility group box 1 protein binding to lipopolysaccharide facilitates transfer of lipopolysaccharide to CD14 and enhances lipopolysaccharide-mediated TNF-alpha production in human monocytes. J Immunol. 2008;180:5067–74. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.5067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oh YJ, Youn JH, Ji Y, Lee SE, Lim KJ, Choi JE, Shin JS. HMGB1 is phosphorylated by classical protein kinase C and is secreted by a calcium-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2009;182:5800–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rauvala H, Rouhiainen A. Physiological and pathophysiological outcomes of the interactions of HMGB1 with cell surface receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799:164–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maroso M, Balosso S, Ravizza T, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 and high-mobility group box-1 are involved in ictogenesis and can be targeted to reduce seizures. Nat Med. 2010;16:413–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vezzani A, French J, Bartfai T, Baram TZ. The role of inflammation in epilepsy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:31–40. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craig CG, Tropepe V, Morshead CM, Reynolds BA, Weiss S, Van Der Kooy D. In vivo growth factor expansion of endogenous subependymal neural precursor cell populations in the adult mouse brain. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2649–58. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02649.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miettinen PJ, Berger JE, Meneses J, et al. Epithelial im-maturity and multiorgan failure in mice lacking epidermal growth factor receptor. Nature. 1993;376:337–41. doi: 10.1038/376337a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farrell RJ. Epidermal growth factor for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:395–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe030075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ménard D, Tremblay E, Ferretti E, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of epidermal growth factor on the immature human intestine. Physiol Genomics. 2012;44(4):268–80. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00101.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russo AJ, Krigsman A, Jepson B, Wakefield A. Decreased serum hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) in autistic children with severe gastrointestinal disease. Biomark Insights. 2009;4:181–90. doi: 10.4137/bmi.s3656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Onore C, Van de Water J, Ashwood P. Decreased levels of EGF in plasma of children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res Treat. 2012;2012:205–362. doi: 10.1155/2012/205362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bae MH, Bissonette GB, Mars WM, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) modulates GABAergic inhibition and seizure susceptibility. Exp Neurol. 2010;221:129–35. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zachmann M, Tocci P, Nyhan WL. The occurrence of gamma-aminobutyric acid in human tissues other than brain. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:1355–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akimoto M, Baba A, Ikeda-Matsuo Y, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor as an enhancer of nmda currents and synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2004;128:155–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ascoli GA, Alonso-Nanclares L, Anderson SA, et al. Petilla terminology: nomenclature of features of GABAergic interneurons of the cerebral cortex. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:557–68. doi: 10.1038/nrn2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhat R, Axtell R, Mitra A, et al. Inhibitory role for GABA in autoimmune inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(6):2580–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915139107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]