Abstract

Intracochlear scarring is a well-described sequela of cochlear implantation. We developed a mathematical model of passive cochlear mechanics to predict the impact that this might have upon residual acoustical hearing after implantation. The cochlea was modeled using lumped impedance terms for scala vestibuli (SV), scala tympani (ST), and the cochlear partition (CP). The damping of ST and CP was increased in the basal one half of the cochlea to simulate the effect of scar tissue. We found that increasing the damping of the ST predominantly reduced basilar membrane vibrations in the apex of the cochlea while increasing the damping of the CP predominantly reduced basilar membrane vibrations in the base of the cochlea. As long as intracochlear scarring continues to occur with cochlear implantation, there will be limitations on hearing preservation. Newer surgical techniques and electrode technologies that do not result in as much scar tissue formation will permit improved hearing preservation.

Keywords: Cochlear implant, Intracochlear scarring, Residual hearing, Passive cochlear model, Damping

1. Introduction

Since the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) initially approved the House 3M cochlear implant system in 1984, cochlear implants have been widely used and have permitted patients with profound hearing loss to have impressively good speech recognition. In the early days of cochlear implants, patients were not considered to be candidates unless hearing thresholds were 100 dB or greater. More recently, the criteria for candidacy have been lowered so that residual hearing becomes an important issue. After cochlear implantation, residual hearing is worsened or destroyed in the majority of the patients (Boggess et al., 1989; Gomaa et al., 2003; Rizer et al., 1988; Rubinstein et al., 1999). Thus, a common component of patient counseling prior to cochlear implantation is warning them that they likely will lose all hearing in the implanted ear and will be unable to use a hearing aid.

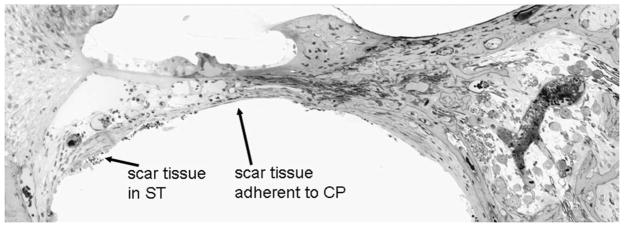

In order to preserve as many spiral ganglion cells as possible and to potentially use both a hearing aid and a cochlear implant in the same ear, the concept of hearing-preservation surgery has been raised. Efforts towards this goal essentially consist of atraumatic electrode insertion. This may include implanting directly through the round window or through an extension of the round window rather than making a large surgical cochleostomy, and the use of shorter, more delicate electrode arrays (Gantz and Turner, 2003; Skarzynski et al., 2002). Nonetheless, one very distinct histological change after cochlear implantation is the formation of scar tissue around the electrode (Alexiades et al., 2001; Araki et al., 2000; Miyamoto et al., 1997). Fig. 1 illustrates such fibrosis formed within the scala tympani. Although the degree of tissue encapsulation around the electrode varies among different subjects, in general the scar is more substantial in the base and is less well-developed at more apical regions (Nadol et al., 2001). This may be because the electrode becomes thinner towards its tip and does not reach the cochlear apex (Skinner et al., 2002).

Fig. 1.

An example of post-implantation intracochlear scarring. This is plastic-embedded cross-section of the basal turn of a cat cochlea after 1 year of implantation. The ST is scala tympani and CP is cochlear partition.

The basilar membrane is a tuned structure so that its maximum displacements at high frequencies occur near the base of the cochlea and those at low frequencies occur near the apex of the cochlea. The cochlear resonant frequency map is determined by its biophysical properties including stiffness, mass and damping (Choi et al., 2004; Von Bekesy, 1960). We hypothesize that the fibrous scar tissue found within scala tympani after cochlear implantation will change the passive mechanical properties of the basilar membrane and affect hearing preservation. We sought to assess this concern by creating a mathematical model of passive cochlear mechanics, in which the scar tissue acted to damp the traveling wave in the basal one half of the cochlea.

2. Methods

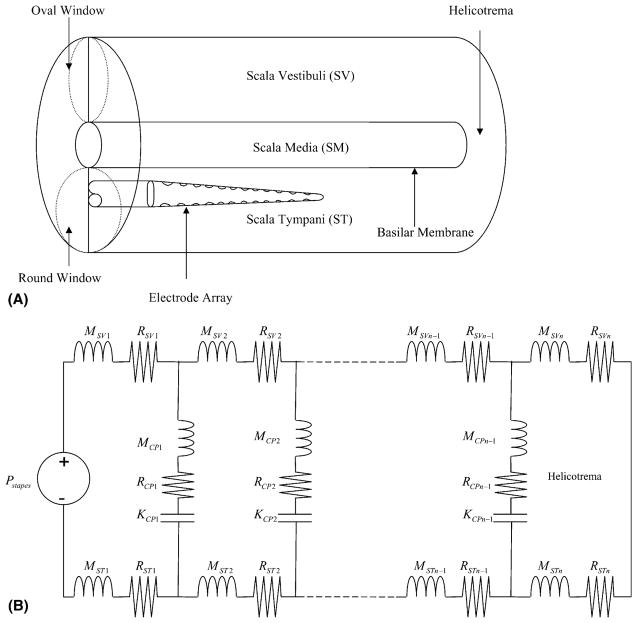

Our one-dimensional model was based on the long-wave model which includes terms for scala vestibuli (SV), cochlear partition (CP), and scala tympani (ST) (Fig. 2A) (Allen, 1980; Neely, 1993; Neely and Kim, 1986). Since patients eligible for cochlear implantation have severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss, we assumed that they had only passive cochlear mechanics. We did not include any active components such as outer hair cell electromotility or stereociliary motility to represent the cochlear amplifier (Brownell et al., 1985; Hudspeth, 1982). The cochlea was divided into 500 segments and modeled using electrical circuit components (Fig. 2B). Each segment had an impedance for SV, ST, and CP defined as ZSV(x), ZST(x), and ZCP(x), respectively. Sound pressure waves enter SV at the base of the cochlea via the stapes footplate attached to the oval window and travel up the cochlear duct. The traveling wave energy is transmitted across the CP, from SV to ST, based on the frequency map of the cochlear duct. At the apex of the cochlea, SV is connected to ST through the helicotrema, dissipating low frequency energy.

Fig. 2.

(A) A schematic diagram of the unrolled cochlear duct. For the purposes of our model, the electrode was considered to only cause scar tissue in the basal one-half of the cochlea. (B) A passive model of cochlear mechanics. K, M, and R are stiffness, mass, and damping, respectively. n is the number of the cochlear segments (n = 500). Pstapes(x) is the input pressure at the stapes attached to the oval window of the SV. The total impedance at a cochlear segment [Z(x)] is the sum of the impedances of SV, ST, and CP.

The fluid characteristics of SV and ST per unit area at a single cochlear segment were described by an impedance term composed of mass (M) and damping (R) elements as follows

| (1) |

where , and ω = 2πf is the angular frequency. The fluid mass M(x) at a single segment was computed as

| (2) |

where ρ was the fluid density (ρ = 1 g/cc), Dx was the length of each cochlear segment (Dx = 500), and AC(x) was the cross-sectional area of SV and ST. SV and ST at any cochlear segment were assumed to be equal in area (Neely and Kim, 1986). The damping parameter R(x) was fit so as to provide proper cochlear input impedance at low frequencies, and was constant over the length of the cochlea [R(x) = 100].

The impedance of the cochlear partition was modeled as lumped terms for stiffness (K), mass (M), and damping (R) as follows:

| (3) |

with ZCP at the helicotrema equal to zero.

In order to simulate the effects of post-implantation cochlear fibrosis on basilar membrane motion, we increased the damping of ST or CP along the basal one-half of the cochlea. The damping of ST or CP in the basal half was increased proportionally for each cochlear section up to 1000 times normal. The damping factor of the apical one-half of the cochlea remained unchanged. There were no changes made in any other parameters. The parameter values used in our model are listed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Parameter values of the passive cochlear model. Parameter values were specified at three different locations (x = 1, x = n/2, n = x)

| Parameter | x = 1 | x = n/2 | x = n | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ac(x) | 5.52E_03 | 3.17E_03 | 4.27E_03 | cm2 |

| Kcp | 7.10E+09 | 6.71E+08 | 2.85E+06 | dyne/cm3 |

| Mcp | 0.1142 | 0.2857 | 1.0285 | g/cm2 |

| Rcp | 14805 | 11880 | 6750 | dyne s/cm3 |

These values were interpolated by fitting a quadratic polynomial to the log of the parameter values specified at these locations.

3. Results

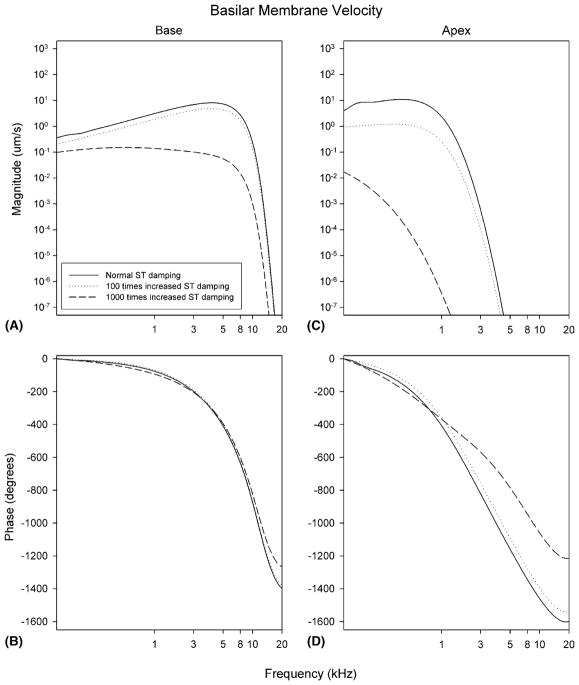

We broke down our analyses to determine the effect of increasing the damping of the ST and the CP independently. For all simulations, the damping of the basal one half of the cochlea was increased up to 1000 times normal while the damping of the apical one-half was left normal. Results from our computer simulation are presented as tuning curves for two different cochlear locations, one near the base and one near the apex. First, we studied the effect of an increase in the damping of ST. At the base, increasing the ST damping up to 100 times normal only slightly reduced the magnitude of basilar membrane velocity. Increasing the ST damping up to 1000 times normal caused larger reductions in the magnitude of basilar membrane velocity (Fig. 3A). At the apex, an increase in the ST damping of either 100 or 1000 times normal substantially decreased the magnitude of basilar membrane velocity (Fig. 3C). Thus, increasing ST damping affected basilar membrane velocity at the apex more than at the base. Similarly, changes in the normal phase response were more prominent at the apex than at the base (Fig. 3B and D).

Fig. 3.

Predicted changes in basilar membrane velocity after an increase in ST damping. Basilar membrane velocity is plotted at two different cochlear segments (the base and the apex) with normal, 100 times, and 1000 times increased ST damping. Note the large decrease in basilar membrane velocity at the apex of the cochlea.

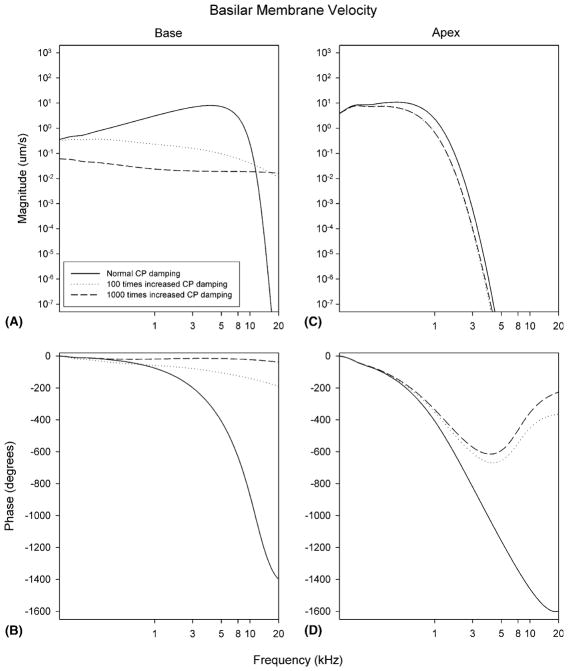

Next, we studied the effect of an increase in the damping of the CP. At the base, increasing the CP damping up to 100 or 1000 times normal significantly decreased the magnitude of basilar membrane velocity resulting in flatter responses (Fig. 4A). However, at the apex, the magnitude of basilar membrane velocity decreased only minimally (Fig. 4C). Thus, in contrast to the effect of increase ST damping, increasing CP damping affected basilar membrane velocity at the base more than at the apex. Corresponding changes in the normal phase response were more prominent at the base than at the apex (Fig. 4B and D).

Fig. 4.

Predicted changes in basilar membrane velocity after an increase in CP damping. Basilar membrane velocity is plotted at two different cochlear segments (the base and the apex) with normal, 100 times, and 1000 times increased CP damping. Note the large decrease in basilar membrane velocity at the base of the cochlea.

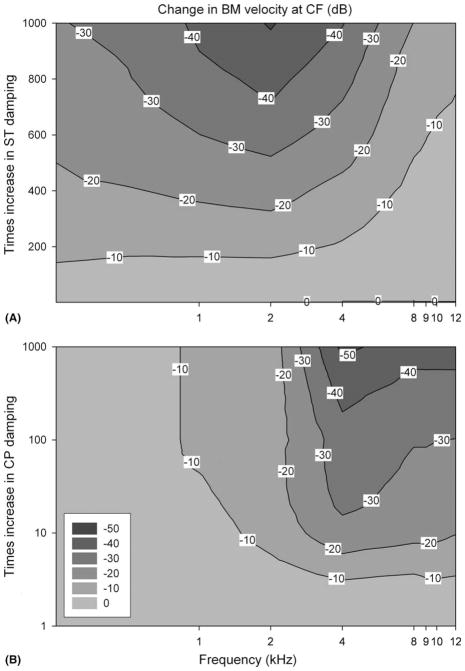

In order to study these effects on cochlear tuning for the multiple sites along the cochlear duct, we specifically looked at changes in basilar membrane velocity only at the characteristic frequency. These data were plotted using a contour plot (Fig. 5). The damping was ranged from 1 to 1000 times normal for either the ST or the CP. Increasing ST damping affected all frequencies, although it took more than a 100 times increase in ST damping before a 10 dB decrease in basilar membrane velocity was noted. In general, the lower frequencies tended to be more sensitive to changes in ST damping (Fig. 5A). In contrast, increasing CP damping only a minimally affected the low frequency region of the cochlea while dramatically decreasing the basilar membrane response to high frequencies (Fig. 5B). No matter what the CP damping multiplier, no shift >10 dB could be generated for low frequencies. However for high frequencies, even raising the damping of the CP 5–6 times normal caused a 10 dB decrease in basilar membrane velocity.

Fig. 5.

4. Discussion

This study suggests that preservation of residual acoustical hearing after implantation may be limited by changes in the biophysical properties of the cochlea caused by the electrode array and/or post-operative scarring. The results of our model predict that increasing the damping of the ST predominantly affects tuning in the apex of the cochlea while increasing the damping of the CP predominantly affects tuning in the base of the cochlea. Additionally, the type and magnitude of the damping increase can have differential effects across the length of the cochlear duct. Small increases in ST damping do not have much of an effect at any frequency while large increases in ST damping have profound effects across all frequencies. In contrast, even small increases in CP damping have profound effects on the base of the cochlea, while having minimal effects on the apex. These predictions have not yet been proven experimentally.

There is a great deal of intersubject variability associated with post-implant cochlear trauma. The types of scarring found include a loose, areolar connective tissue, a dense, fibrotic capsule with little evidence of inflammation (i.e. Fig. 1), a dense, highly reactive matrix with neovasculature, and evidence of acute and/or chronic inflammation, or new bone formation that can come to completely surround the carrier (Ketten et al., 1998; Skinner et al., 2002). Thus, the damping due to the peri-implant reaction could vary tremendously among patients. Additionally, there are likely to be gradual changes in the scarring along the length of the cochlea rather than the abrupt change we simulated. Of course, if ST or CP damping is increased infinitely with severe scarring or bone deposition, the total impedance of CP will be infinite, resulting in no basilar membrane motion and a total loss of residual hearing.

Our simulation provides only rough estimates of cochlear damping secondary to scar formation, and does not take into account other side effects of cochlear implantation on auditory function. This includes damage to the osseous spiral lamina such as fracture, or even dislocation, that induces degeneration of spiral ganglion cells (Nadol et al., 2001). Injury to the spiral ligament and stria vascularis can occur, even to the point where it dissects off the inside of the otic capsule (Richter et al., 2002). Also, there can also be migration of electrodes across the cochlear partition into SV (Ketten et al., 1998; Skinner et al., 2002). Finally, it should be noted that for simplicity, our model is based on the unproven premise that intracochlear scar tissue causes an increase in damping. We believe this to be a reasonable assumption. However, our model does not consider other changes in cochlear biomechanics that may also occur, such as an increase in CP stiffness (Wenzel et al., 2004) and a decrease in ST fluid mass (de Boer, 1996).

The basilar membrane velocity shifts predicted by our model approximate the threshold shifts found in clinical studies that measured residual acoustical hearing after cochlear implantation. It has been reported that 64% of 219 patients with cochlear implants have a reduction of less than 10 dB in residual hearing after cochlear implantation (Clark, 1995). Similar reductions of 9 dB HL (Skarzynski et al., 2002) and 12 dB HL (Hodges et al., 1997) have been reported by other groups. While these changes in hearing thresholds after cochlear implantation are not necessarily related to post-implant fibrosis within scala tympani, these data can be used to place an upper boundary on the increase in damping that occurs after implantation within the measured frequency range. Assuming there is a 10 dB threshold shift and basilar membrane velocity is linearly related to hearing thresholds, our model predicts that there may be up to 150 times the normal damping of scala tympani. However, in order to preserve high frequency hearing, there can not be more than 5 times the normal damping of the cochlear partition.

5. Summary and conclusion

The present study investigated whether scar tissue formation caused by the insertion of the cochlear implant electrode might generate changes in the biophysical properties of the cochlea that would result in changes in residual hearing after cochlear implantation. A passive cochlea model was developed using lumped impedances for scala vestibuli (SV), scala tympani (ST), and the cochlear partition (CP). Computer simulation showed that basilar membrane velocity at the apex of the cochlea was most reduced by increasing the damping of the ST while basilar membrane velocity at the base of the cochlea was most reduced by increasing the damping of the CP. Our model predicts that scar tissue formation around the implant electrode can lead to decreases in residual hearing.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Pat Leake for providing Fig. 1, and for her useful comments on the manuscript. The authors would like to thank Mark E. Chertoff, William E. Brownell, Ross Tonini, and Danny Chelius for their valuable feedback on the original manuscript. Furthermore, we would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful criticism and comments on the manuscript. This project was funded by NIH-NIDCD Grant DC006671 and a grant from the National Organization for Hearing Research Foundation (to JSO).

References

- Alexiades G, Roland JT, Jr, Fishman AJ, Shapiro W, Waltzmann SB, Cohen NL. Cochlear reimplantation: surgical techniques and functional results. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1608–1613. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200109000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JB. Cochlear micromechanics – a physical model of transduction. J Acoust Soc Am. 1980;68:1660–1670. doi: 10.1121/1.385198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki S, Kawano A, Seldon HL, Shepherd RK, Funasaka S, Clark GM. Effect of intracochlear factors on spiral ganglion cells and auditory brain stem response after long-term electrical stimulation in deafened kittens. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:425–433. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(00)70060-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggess WJ, Baker JE, Balkany TJ. Loss of residual hearing after cochlear implantation. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:1002–1005. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198210000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell WE, Bader CR, Bertrand D, de Ribaupierre Y. Evoked mechanical responses of isolated cochlear outer hair cells. Science. 1985;227:194–196. doi: 10.1126/science.3966153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C-H, Spector AA, Oghalai JS. A cochlear model designed to test the effect of modulating outer hair cell biophysical properties on basilar membrane mechanics. Twenty-Seventh Annual MidWinter Research Meeting of the Association of Research in Otolaryngology; Florida. 2004. p. 346. [Google Scholar]

- Clark GM. Cochlear implants: future research directions. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1995;(Suppl 166):22–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer E. Mechanics of the cochlea: modeling efforts. In: Dallos P, Popper AN, Fay RR, editors. The Cochlea. Vol. 8. Springer; New York: 1996. pp. 258–317. [Google Scholar]

- Gantz BJ, Turner CW. Combining acoustic and electrical hearing. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1726–1730. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200310000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomaa NA, Rubinstein JT, Lowder MW, Tyler RS, Gantz BJ. Residual speech perception and cochlear implant performance in postlingually deafened adults. Ear Hear. 2003;24:539–544. doi: 10.1097/01.AUD.0000100208.26628.2D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges AV, Schloffman J, Balkany T. Conservation of residual hearing with cochlear implantation. Am J Otol. 1997;18:179–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudspeth AJ. Extracellular current flow and the site of transduction by vertebrate hair cells. J Neurosci. 1982;2:1–10. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-01-00001.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketten DR, Skinner MW, Wang G, Vannier MW, Gates GA, Neely JG. In vivo measures of cochlear length and insertion depth of nucleus cochlear implant electrode arrays. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1998;(Suppl 175):1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto RT, Svirsky MA, Myres WA, Kirk KI, Schulte J. Cochlear implant reimplantation. Am J Otol. 1997;18:S60–S61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadol JB, Jr, Shiao JY, Burgess BJ, Ketten DR, Eddington DK, Gantz BJ, Kos I, Montandon P, Coker NJ, Roland JT, Jr, Shallop JK. Histopathology of cochlear implants in humans. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110:883–891. doi: 10.1177/000348940111000914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely ST. A model of cochlear mechanics with outer hair cell motility. J Acoust Soc Am. 1993;94:137–146. doi: 10.1121/1.407091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely ST, Kim DO. A model for active elements in cochlear biomechanics. J Acoust Soc Am. 1986;79:1472–1480. doi: 10.1121/1.393674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter B, Aschendorff A, Lohnstein P, Husstedt H, Nagursky H, Laszig R. Clarion 1.2 standard electrode array with partial space-filling positioner: radiological and histological evaluation in human temporal bones. J Laryngol Otol. 2002;116:507–513. doi: 10.1258/002221502760132584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizer FM, Arkis PN, Lippy WH, Schuring AG. A postoperative audiometric evaluation of cochlear implant patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;98:203–206. doi: 10.1177/019459988809800304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein JT, Parkinson WS, Tyler RS, Gantz BJ. Residual speech recognition and cochlear implant performance: effects of implantation criteria. Am J Otol. 1999;20:445–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skarzynski H, Lorens A, D’Haese P, Walkowiak A, Piotrowska A, Sliwa L, Anderson I. Preservation of residual hearing in children and post-lingually deafened adults after cochlear implantation: an initial study. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2002;64:247–253. doi: 10.1159/000064134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner MW, Ketten DR, Holden LK, Harding GW, Smith PG, Gates GA, Neely JG, Kletzker GR, Brunsden B, Blocker B. CT-derived estimation of cochlear morphology and electrode array position in relation to word recognition in Nucleus-22 recipients. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2002;3:332–350. doi: 10.1007/s101620020013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Bekesy G. Experiments in Hearing. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel GI, Pikkula B, Choi CH, Anvari B, Oghalai JS. Laser irradiation of the guinea pig basilar membrane. Lasers Surg Med. 2004;35:174–180. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]