Synopsis

Detection of melanoma at an early stage is crucial to improving survival rates in melanoma. Accurate diagnosis by current techniques including dermatoscopy remains difficult, and new tools are needed to improve our diagnostic abilities. This article discusses recent advances in diagnostic techniques including confocal scanning laser microscopy, MelaFind, Siascopy, noninvasive genomic detection, as well as other future possibilities to aid in diagnosing melanoma. Advantages and barriers to implementation of the various technologies are discussed as well.

Tags: melanoma diagnosis, advances in melanoma diagnosis, new technologies for melanoma diagnosis, dermatoscopy, self skin exam, temporal analysis, total body photography, confocal scanning laser microscopy, Vivascope, multispectral imaging, MelaFind, SiaScope, optical coherence tomography, reflex transmission imaging, epidermal genetic information retrieval, noninvasive genomic detection, electrical impedance spectroscopy, x-ray fiber diffraction, tissue elastography, thermal imaging, melanoma sniffing dogs

Keywords: Melanoma detection, technology, imaging, biopsy, automated diagnosis

Introduction

According to estimates, there will be approximately 70,000 new cases of melanoma and 8800 deaths in 2011. The incidence of melanoma has been steadily increasing and has doubled in recent decades.1 For lesions with a depth of less than 1mm, surgical excision is usually curative and 5-year survival rate is 93–97%.2 By contrast, distant metastatic melanoma has an extremely poor prognosis and 5-year survival ranges from 10 – 20 % depending on location of the metastasis.2 Detection of melanoma at an early stage is critical for improving the survival rate. In addition to decreased survival of late versus early stage melanoma, the cost of treating a late stage melanoma is dramatically higher. Recent estimates show the total costs of in situ tumors to be around $4700 while a stage IV melanoma has a total cost of approximately $160,000.3 The cost of treating late stage melanoma is likely to rise with the implementation of newly approved treatments such as ipilimumab which costs about $120,000 for a full treatment.

Despite advances in diagnostic aides such as dermatoscopy, detection has remained a significant challenge and improved methods of accurately diagnosing melanoma are needed. Studies have shown that even for expert dermoscopists, accurately diagnosing melanoma, particularly in small diameter lesions, is very challenging with one study showing a biopsy sensitivity of 71% for melanomas of less than 6mm.4 To measure specificity, numerous studies have looked at biopsy ratios – i.e. the number of biopsies of benign lesions performed to make the diagnosis of one skin cancer -- and numbers vary widely. On the low end, a study from a specialized pigmented lesion clinic showed a biopsy ratio of approximately 5:1 (5 benign lesions per melanoma biopsied).5 A recent retrospective study involving eight practitioners at a single institution had a biopsy ratio of 15:1.6 On the high end, a study involving a single physician over a 14-year period showed a biopsy ratio of over 500:1 in patients with no history of melanoma.7 Given these challenges, new diagnostic aides that could help increase both sensitivity and specificity of biopsies would be of great benefit to patients and physicians. Such improvements have the potential to lead to increased diagnosis of early lesions which would improve survival and lower overall cost of treating melanoma. Additionally, improved diagnostic techniques would lead to fewer biopsies and decreased morbidity to patients.

Established methods

Physician and patient detection of malignant melanoma

Multiple studies have tried to assess who initially detects melanomas, with most finding the majority of melanomas are detected by the patient.8–10 Patient education including the ‘ABCDEs’ (asymmetry, border irregularity, color variegation, diameter of greater than 6 mm, and evolution) of melanoma will always be an important part of helping patients to diagnose melanoma.11, 12 In addition, regular self-skin examinations should be encouraged as they have been associated with detection of thinner melanomas and may reduce mortality.13–15 Self detection appears to be most successful in younger patients as increased age has been associated with increased Breslow thickness in patients who discovered melanoma by self examination.16 Physician-detected melanomas, particularly melanomas detected by dermatologists, tend to be thinner.8–10, 14, 17

Dermatoscopy

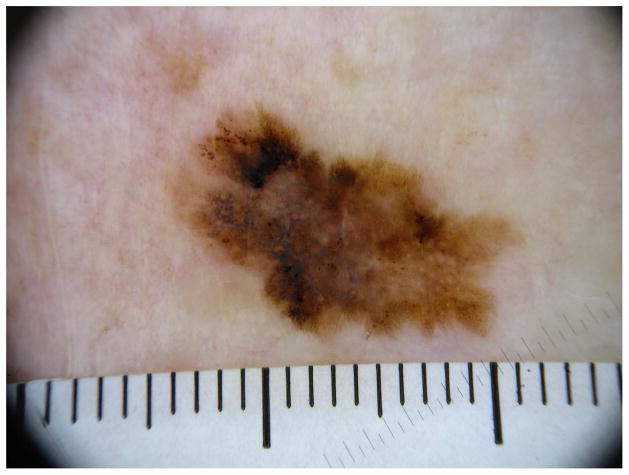

Dermatoscopy, covered in depth elsewhere in this issue, has been widely used by dermatologists to improve their abilities to accurately diagnose melanoma, and has been shown to improve early detection of melanoma,18 while reducing unnecessary biopsies.19, 20 A major drawback to dermatoscopy is that it is highly user-dependant and varies with experience.21 Despite the advantages of using dermatoscopy, only about 60% of dermatologists in the US are trained in its use, and less than half report using dermatoscopy daily.22 (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Dermatoscopic image of an invasive melanoma.

Temporal analysis of the skin

In addition to dermatoscopy alone, temporal analysis of the skin is also commonly used. Individual lesions can be followed serially with dermatoscopy and/or photography. Total body photography can be used to monitor for new or changing lesions, particularly in patients with a large number of nevi or high-risk patients. Temporal analysis has been shown to increase the sensitivity of melanoma detection when compared to dermatoscopy alone.23 A perceived benefit of total body photography would be to decrease the biopsy rate. This has been demonstrated in some studies,24 although others have failed to show any noticeable change in number of biopsies performed.25 Total body photography appears to be most useful in older patients as one study showed that in patients younger than 50 years, less than 1% of new lesions identified by photography turned out to be melanoma, whereas in patients older than 50 years 30% of new lesions were melanomas on biopsy.26

Total body photography has the limitation of being time consuming and laborious. Also, costs can run as high as $500 per person and aren’t typically covered by insurance. Imaging technologies including MoleMax (Derma Medical Systems, Vienna, Austria) and FotoFinder (FotoFinder Systems, Inc., Columbia, Maryland, USA) are computerized systems used to help the clinician to more rapidly and efficiently perform total body cutatneous photography and dermatoscopy of individual lesions. MoleMax has software available to analyze pigmented lesions and provide a scoring system based on established criteria to aid clinicians in evaluating concerning lesions. The FotoFinder system also has software that aids in the detection of new nevi by comparing baseline photos to those taken at a follow up visit as well as software that rates the likelihood that a pigmented lesion is a melanoma. However, there are no large peer-reviewed studies that have validated the accuracy of these systems.

Recent advances

CSLM

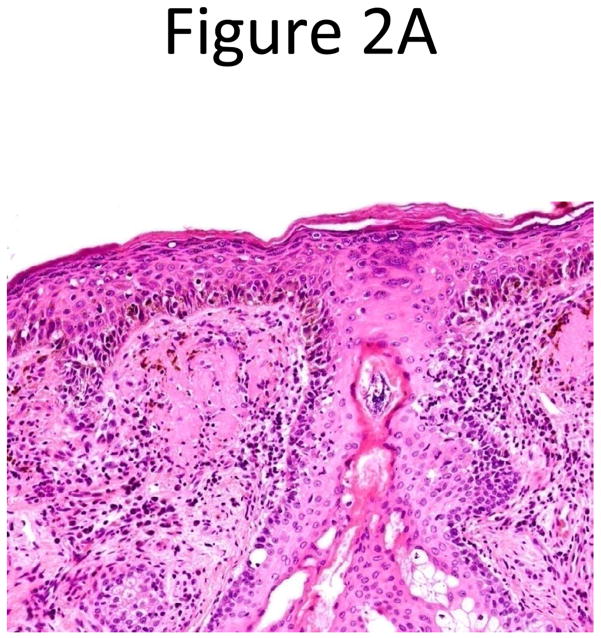

Confocal scanning laser microscopy (CSLM) is a non-invasive imaging technology that provides in vivo images of the epidermis and papillary dermis in real time. There are currently two forms of CSLM that are used: reflectance mode which is primarily used in clinical practice and fluorescence mode used primarily in research. Reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) relies on the inherent reflective properties of tissue structures, whereas fluorescence CSLM relies on fluorescent dyes to provide contrast for images.27 The contrast seen in RCM images is due to the naturally occurring variations in refractive index of organelles and other structures within the skin. Melanin granules have a high refractive index which causes more light to be reflected back to the confocal microscope. Thus areas of higher melanin concentration will appear as bright areas on a confocal image (Figure 2). When used by those properly trained in confocal use, lesions can be evaluated based on characteristics such as cellular atypia, uniformity of pigment distribution, loss of keratinocyte borders, and rate of blood flow to help distinguish malignant from benign lesions. One of the unique features of CSLM is its ability to detect amelanotic melanoma because of the presence of melanosomes and rare melanin granules.28

Figure 2.

Histopathology (A) and confocal microscopy (B) from an in situ melanoma. Images courtesy of Harold Rabinovitz, MD.

CSLM works by intensely focusing a low-power laser beam on a specific point in the skin. Light from that point is then reflected from structures within the skin and passes through a pinhole-sized aperture to a detection apparatus. The reflected light is transformed into an electrical signal to create a 3 dimensional image from the scanned horizontal sections.29 Imaging depth is related to the wavelength of light used, with longer wavelengths allowing deeper imaging. RCM uses a near-infrared 830 nm laser which provides an imaging depth of 250–300 μm in normal skin, allowing visualization to the level of the superficial dermis.27 The images provide 1–2μm of lateral resolution and 3–5μm of axial resolution.30 This resolution is comparable to standard pathology which is typically based on 5μm thin sections. CSLM has potential to provide a ‘virtual biopsy’ of concerning skin lesions. Advantages of CSLM are that, like dermatoscopy, it is non-invasive and allows rapid imaging of multiple lesions, and can be used to follow lesions over time. CSLM is also similar to dermatoscopy in that it requires the reader’s interpretation and is thus user dependant. Training required to accurately use CSLM has been reported to be less than that of dermatoscopy with subjects showing ability to correctly diagnose images of lesions from a test set after only 30 minutes of instruction in one study.31

CSLM has demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing melanoma from benign pigmented lesions. One study involving a test set of 27 melanomas and 90 benign nevi with images evaluated by 5 independent observers showed a sensitivity of 88.15% and specificity of 97.6%.31 A retrospective study of 3709 unselected CSLM melanocytic tumor images coming from 50 benign nevi and 20 melanomas showed sensitivity and specificity of 97.5% and 99% respectively.32 In comparison with standard dermatoscopy, another prospective study showed sensitivity and specificity of CSLM to be 97.3% and 83% respectively compared to a sensitivity and specificity of 89.2% and 84.1% for dermatoscopy.33 This study, however, involved only a single observer and evaluated 37 melanomas and 88 nevi.

CSLM has been tested with diagnostic image analysis for fully automated diagnosis and such a system could be a possibility in the future to hopefully improve diagnostic accuracy and decrease user dependence.34–36 CSLM is also limited by its cost. A commercially available unit costs approximately $50,000. While the upfront cost of the device is high, the supplies to image individual lesions cost only about $1 per lesion allowing imaging of multiple lesions with minimal increased cost to the patient per lesion.

Advances in CSLM technology continue to make it a more useful diagnostic tool. Newer devices use a single optical fiber to both illuminate and detect the laser light in place of the pinhole aperture detector found in earlier CSLM devices. This improvement in technology has led to miniaturization of the confocal scanner into a flexible and more user-friendly handheld device. Multiple CSLM units are available and have FDA 510(k) clearance including the VivaScope 1500 and the handheld VivaScope 3000 (Lucid, Inc., Rochester, New York, USA).

Multispectral imaging

SIAscope (Spectrophotometric Intracutaneous Analysis, made by Biocompatibles, Farnham, Surrey, UK) emits radiation ranging from 400 nm to 1000 nm and provides the user with 8 narrow-band spectrally filtered images which demonstrate the vascular composition and pigment network of a lesion. This multispectral imaging technology has FDA 510(k) clearance and uses a hand-held imager to provide microarchitectural information for concerning lesions. The SIAscope measures levels of three chromophores (melanin, blood, and collagen) contained in the epidermis and papillary dermis. It is also able to show if melanin is confined to the epidermis, or whether it has penetrated into the deeper dermis. The clinician then interprets these images to determine whether or not a biopsy is necessary. In a study of 384 lesions, siascopy was found to have a sensistivity of 82.7 % and specificity of 80.1%.37 However, a larger study showed that siascopy had similar sensitivity and specificity to dermatoscopy performed by experienced dermatologists and thus didn’t provide sufficient benefit in diagnosing melanoma to warrant its use.38 One of the major criticisms of siascopy is that it uses features in its diagnostic classification that are common to benign lesions such as seborrheic keratoses and hemangiomas which causes many benign lesions to be classified as suspicious.39 A recent study sought to develop a scoring system to correctly classify lesions and allow use of siascopy in a primary care setting.39 The scoring system is still early in its development and needs further improvement and validation, but such a system could provide primary care physicians a useful tool to screen a larger population of patients with referral to a dermatologist for suspicious lesions.

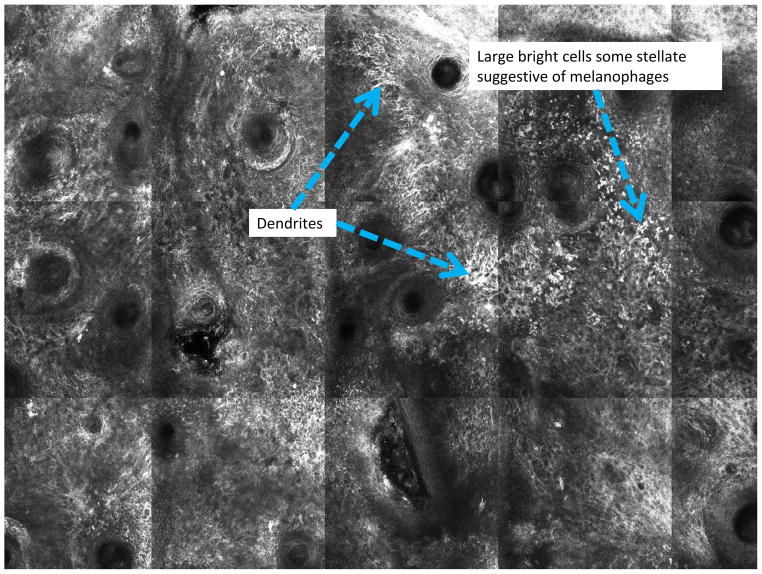

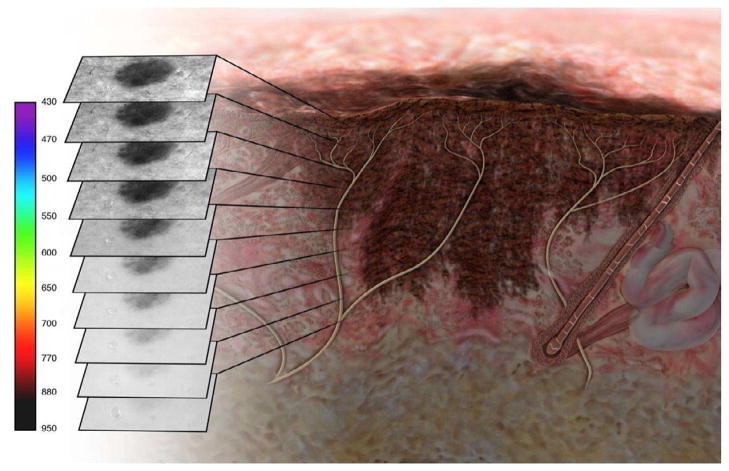

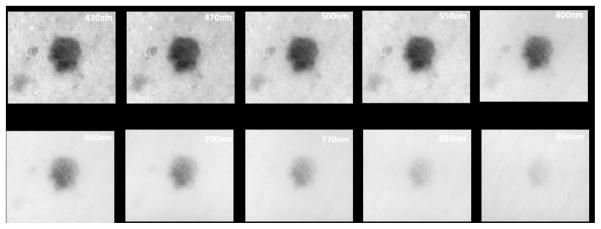

As most imaging modalities require user interpretation and are thus prone to varying levels of accuracy based on user experience, attempts have been made to create automated imaging systems to improve diagnostic accuracy. MelaFind (MELA Sciences, Inc., Irvington, New York, USA) is a hand-held imager that evaluates lesions with multispectral images in 10 different spectral bands, from blue (430nm) to near infrared (950nm). The images are processed with proprietary software which generates a 10 digital image sequences in less than 3 seconds. The software determines the border of the lesion and analyzes the lesion for asymmetry, color variation, perimeter changes, texture changes, and wavelet maxima40(Figure 3). The MelaFind device then provides the user with a recommendation of whether or not to perform a biopsy base upon this analysis. The algorithm for determining biopsy recommendation comes from a database of approximately 9,000 biopsied lesions from 7,000 patients consisting of in vivo skin lesion images and corresponding histopathological results.

Figure 3.

Figure 3A: A representative schematic of multispectral image analysis of a pigmented lesion showing 10 images from multiple depths within the skin.

Figure 3B: Actual images from multispectral image analysis showing a digitally detected margin from most superficial (430nm) to deepest (950nm)

A recent large multicenter study evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of MelaFind and found it to have a sensitivity of 98.4% and a specificity superior to that of expert dermatologists using dermatoscopy.41 In the study, MelaFind had a biopsy ratio of 10.8:1 for melanomas, and a ratio of 7.6:1 if borderline lesions (high-grade dysplastic nevus, atypical melanocytic hyperplasia, and atypical melanocyte proliferation) were also included.41 Such a biopsy ratio is better than most ratios from reported literature. An earlier study evaluated the ability of MelaFind to diagnose melanoma in small pigmented lesions (less than 6mm) and showed a sensitivity of 98% for melanoma.4 This study also showed sensitivity superior to expert dermatologists with similar levels of specificity.

MelaFind was approved for use in Europe in September, 2011 and recently received clearance for use in the United States at the time of this writing. In contrast to other devices which only have FDA 510(k) clearance, MelaFind has FDA premarket approval. MelaFind differs from other diagnostic modalities in that it provides the user with a recommendation as to whether or not to biopsy, whereas many other technologies completely rely on user interpretation for decision to biopsy. As such, MELA Sciences has strict quality controls in place and would need to maintain ownership of the device to assure that devices are properly updated and maintained. MelaFind is expected to be made available to dermatologists with doctors paying a one-time fee of $7500 to lease the device and receive training. Pricing per procedure is estimated to be $150 per patient visit. MELA Sciences is not asking insurers to cover the device, so the visit fee will come as an out of pocket expense to the patient. Given that the price per use is less than the cost of biopsy and histopathology, MelaFind could provide a cost effective means of reducing numbers of biopsies while improving diagnostic accuracy.

Other imaging technologies

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a well-established tool in ophthalmology. It is commonly used as a diagnostic aide for uveal melanoma42 and has shown usefulness in dermatology as well. OCT is analogous to ultrasound imaging, except that it uses light rather than sound waves. OCT uses a lowcoherence length light source to evaluate lesion architecture up to 1 mm in depth.43 One study showed that OCT allows for in vivo correlation between dermatoscopic parameters and histophathologic analysis in melanocytic lesions.44 Resolution in OCT is insufficient to show morphology of single cells, but does allow for evaluation of architectural changes.45 OCT is further limited as it has shown inability to properly image lesions that are raised or hyperkeratotic. The resolution in OCT lies between ultrasound and CSLM and at this point is best suited for measuring depth of invasion rather that diagnosing melanoma.

Reflex transmission imaging (RTI) is a form of high-resolution ultrasound that can be combined with white light digital photography to classify pigmented lesions. In one study, RTI was found to discriminate between melanoma, seborrheic keratoses, and nevi based on quantitative methods involving various sonographical parameters.46 When parameters were set to yield 100% sensitivity for distinguishing melanoma from seborrheic keratoses and benign pigmented lesions, RTI provided a 79% specificity for differentiation of seborrheic keratoses from melanoma, and a specificity of 55% for differentiating benign pigmented lesions from melanoma.46 RTI has yet to be validated in prospective studies, but results from initial studies warrants further investigation into its clinical applications.

Upcoming technologies

Noninvasive genomic detection

Epidermal genetic information retrieval (EGIR; DermTech International, La Jolla, California, USA) uses an adhesive tape placed on suspicious lesions to sample cells from the stratum corneum noninvasively. RNA isolated from cells is amplified using real-time PCR and then hydbridized with Affymetrix human genome U133 plus 2.0 GeneChip. Gene expression is then analyzed. Using this technology, 312 genes that are differentially expressed between melanoma, nevi, and normal skin were identified.47 Subsequent analysis has reduced the number or genes needed to be analyzed to differentiate melanoma from nevi to 17.47 The 17 genes used in the analysis are known to be involved in functions such as melanocyte development, pigmentation signaling, hair and skin development, melanoma progression, cell death, cellular development, and cancer. Using this 17-gene classifier, EGIR was able to accurately differentiate between in situ and invasive melanomas from nevi with 100% sensitivity and 88% specificity.47

EGIR has many potential advantages. It is non-invasive and samples can be easily obtained in the office setting. Multiple lesions can be quickly sampled preventing initial need for biopsies, and in studies to date, EGIR has shown high sensitivity and specificity. The major disadvantage is that it requires the tape sample to be sent to a distant laboratory, and results would not be available the same day as they would be with other imaging technologies. Patients would be required to return at a later date for a biopsy if indicated by the test results which could raise the possibility of patients being lost to follow-up.

As the RNA analyzed with EGIR is isolated from cells found in the stratum corneum, it is interesting that diagnosis of melanoma can be made by tape stripping considering the fact that melanocytes generally reside deeper, at the dermal-epidermal junction. It is unclear if the RNA sampled comes directly from the melanocytes, is due to the effect of melanocytes on surrounding keratinocytes through cell-cell crosstalk, or is a result of pagetoid spread of melanocytes into the epidermis. Regardless of the mechanism, EGIR has great potential and represents a novel technique in diagnosing melanoma, although initial studies are limited in sample size.

Electrical impedance spectroscopy

Electrical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) is an investigational technology which has shown promise in its ability to assist in diagnosing melanoma. EIS uses an impedance spectrometer probe to measure opposition to flow of alternating currents from one pole to another across a lesion at various frequencies. The probe consists of many microscopic pins designed to penetrate the stratum corneum and pass a low voltage current to allow measurement of electrical impedance of the tissue. EIS works on the premise that cancer cells have electrochemical properties that are distinct from those of healthy cells.48 EIS has demonstrated the ability to distinguish different stages of breast cancer cell lines.49 In vitro studies using cultured mouse melanoma cells show reduced membrane capacitance typical of other types of cancer cells, supporting the possibility the EIS could be useful in melanoma detection.50

Two recent in vivo studies evaluated EIS using an automated algorithm to distinguish between melanoma and benign lesions. One study evaluated 62 malignant melanomas and 148 various benign lesions and showed a sensitivity to melanoma of 95 % and specificity of 49%.51 These numbers were similar to a previous study that showed a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 64%.52 While EIS is a promising new technology, it does have limitations and improvements still need to be made. Despite the fact that EIS uses an automated algorithm, it is still somewhat user dependant in accurately providing a diagnosis. The procedure for evaluating a lesion involves soaking the skin in saline solution for 60 seconds prior to impedance measurement to facilitate better contact between the skin and electrode system. One EIS measurement takes approximately 20 seconds, and measuring an entire lesion typically takes less than 5 minutes. It is also necessary to measure EIS in peri-lesional skin for calibration to compensate for inter-subject variation due to factors such as age, gender, body location, and seasonal variation.51 In most cases, EIS is more time-consuming than a skin biopsy and other diagnostic modalities, and is also more technically challenging. Despite these limitations, its ability to noninvasively analyze a lesion and accurately recommend need for biopsy make it an intriguing technology for further study.

Fiber diffraction

The alpha keratins in hair and nail proteins produce a characteristic X-ray fiber diffraction pattern in all mammals, regardless of age or species.53 Recent studies have shown that some cancers, including melanoma, cause detectable alterations in the molecular patterns of macromolecules in hair, nails, and skin. A recent blinded retrospective study looking at multiple forms of cancer was able to detect changes in X-ray fiber diffraction from skin samples in all 28 patients diagnosed with melanoma.54 The diffraction pattern for all melanoma patients had a single additional ring in the same location which was not appreciated in any other of the 238 patients consisting of controls as well as patients with other cancers or systemic diseases.54 There is currently no biological mechanism to explain the changes in diffraction patterns, but results have been consistent and specific to the type of malignancy, and have not resulted in any false negatives. Large prospective studies are still needed to clarify sensitivity and specificity, and this technique would only indicate the presence of melanoma somewhere in the patient but would not identify specific lesions of concern. However fiber diffraction is certainly an intriguing possibility for melanoma detection or screening, particularly in high risk patients.

Tissue elastography

Real-time tissue elastography is a technology under very early investigation which is based on the principle that softer, normal tissue deforms more easily than harder, malignant tissue.55 Lesions are evaluated by manually applying light pressure with an ultrasound transducer with simultaneous imaging by ultrasound. A recent report showed that tissue elastography was able to correctly identify cutaneous melanoma in two patients.56 Similar to other evaluative methods, tissue elastrography is highly operator dependant. Tissue elastography has been shown to be a useful diagnostic tool in detection of breast and prostate cancer.57 With further refinement, tissue elastography could someday be an affordable, noninvasive diagnostic tool for diagnosing melanoma.

Thermal imaging

Like many other cancers, melanoma lesions have higher metabolic activity than normal healthy tissue. This property could be exploited using dynamic thermal imaging to examine lesions with infrared imaging. Early results show that there are detectable temperature differences between melanoma and healthy tissue. This technique is currently technically challenging as the skin must be cooled to accentuate temperature differences and sophisticated motion tracking is needed to compensate for movement of the patient while acquiring thermal images.58

Melanoma sniffing dogs

A recent study in lung cancer detection has shown promise in the ability of dogs to detect cancer in patients. In this study, dogs examined 220 exhalation samples from a combination of patients with and without lung cancer. The dogs were able to correctly identify 71% of the samples coming from those with lung cancer, and correctly identified 93% of the samples that were cancer free.59 A similar study also showed promise with detection of breast cancer from exhalation samples.60 There have been isolated case reports of dogs identifying skin cancers in patients. In one case, a dog continually showed interest in a mole belonging to its owner, and even tried to bite off the mole, which eventually led the owner to seek medical advice. The mole was excised and found to be invasive melanoma.61 A similar case was reported in a patient with a lesion later found to be a basal cell carcinoma.62 The experiences in lung and breast cancer suggest trained canines may hold promise as aides in the dermatology office for the detection of melanoma, although clinical trials will be needed to see if the evidence goes beyond anecdotal.

Conclusion

Despite recent advances in diagnosis and treatment of malignant melanoma, it still remains a potentially devastating disease if not diagnosed early and treated properly. With an incidence continuing to increase, advances in diagnostic techniques are necessary as diagnosing melanoma is difficult and current methods still miss too many cases, especially in small diameter lesions. Also, biopsying benign lesions can lead to increased morbidity to patients and increased cost to the healthcare system. Many available technologies are underutilized with more promising technologies on the way.

There are significant barriers to implementation which must be overcome. These include the time, training, and experience needed to properly use many of these technologies, and costs associated with developing and adopting new technologies. Also, none of these modalities currently are reimbursed by insurance carriers. Ideally, new technologies would 1) have increased sensitivity and specificity in comparison with current methods, 2) be able to be used in a time-efficient manor such that the time needed to use the diagnostic aide is equivalent to or less than the time it takes to perform a biopsy, 3) have some reimbursement by insurance if proven to decrease the number benign biopsies performed to encourage their wide-spread use, and 4) be accessible to a wide range of patients and physicians, including non-dermatologists as a significant proportion of melanomas are diagnosed by PCPs and other physicians. With proper implementation of these technologies, hopefully we can reach our ultimate goal of reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with melanoma.

Table 1.

Comparison of Technologies in Melanoma Diagnosis

| Technology | Sensitivity | Specificity | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confocal scanning laser microscopy | 88–98%31–33 | 83–98%31–33 | Provides a ‘virtual biopsy’ of concerning lesions. Low incremental cost per lesion after initial investment | Accuracy is user dependant; imaging depth only 300 μm; imaging system is expensive |

| MelaFind | 98%41 | 10%41* | Provides automated diagnosis minimizing user dependance | Cost of imaging is $150 which must be covered by the patient |

| SiaScope | 83–91%37 | 80–91%37, 38 | Provides high resolution images of melanin, hemoglobin, and collagen content in the epidermis and papillary dermis | Accuracy is user dependant; diagnostic features may classify many benign lesions as malignant |

| Epidermal genetic information retrieval | 100%47 | 88%47 | Minimal special equipment or investment required upfront | Samples must be sent to distant laboratory delaying diagnosis |

| Electrical impedance spectroscopy | 91–95%51, 52 | 49–64%51, 52 | Provides automated diagnosis | Can be technically challenging; can take up to 5 minutes per lesion for evaluation |

Lesions evaluated in this study were enriched by pre-selection from a general population. Lesions were already scheduled for a biopsy due to high concern for melanoma resulting in a lower specificity in comparison to other studies performed in lesions that were not preselected.

Key Points.

The incidence of melanoma is continuing to increase

Current methods commonly fail to diagnose melanoma at an early stage

Use of dermatoscopy has improved our diagnostic capabilities, but is highly user dependant and commonly misses the diagnosis

Recent advances have lead to new diagnostic technologies such as confocal scanning laser microscopy, MelaFind, Siascopy, noninvasive genomic detection, and many others

Systems such as MelaFind are being created to provide an automated diagnosis to improve diagnostic accuracy and decrease need for biopsy of benign lesions

Several barriers to implementation exist including cost, time needed to become competent in use of new technologies, and lack of insurance reimbursement for use of new modalities

Proper implementation of new technologies will hopefully lead to earlier diagnosis of melanoma, decreased mortality and morbidity, fewer biopsies of benign lesions, and decreased cost to the health care system.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources:

Dr. Ferris: NIH/NCRR grant number 5 UL1 RR024153-04

Dr. Harris: none

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

Dr. Ferris: Served as an investigator and consultant for MELA Sciences and as an investigator for DermTech International

Dr. Harris: No conflicts of interest to declare

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, et al. Cancer statistics, 2011: the impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 61:212–236. doi: 10.3322/caac.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199–6206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexandrescu DT. Melanoma costs: a dynamic model comparing estimated overall costs of various clinical stages. Dermatology online journal. 2009;15:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman RJ, Gutkowicz-Krusin D, Farber MJ, et al. The diagnostic performance of expert dermoscopists vs a computer-vision system on small-diameter melanomas. Archives of dermatology. 2008;144:476–482. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.4.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carli P, Nardini P, Crocetti E, et al. Frequency and characteristics of melanomas missed at a pigmented lesion clinic: a registry-based study. Melanoma research. 2004;14:403–407. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200410000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson RL, Yentzer BA, Isom SP, et al. How good are US dermatologists at discriminating skin cancers? A number-needed-to-treat analysis. The Journal of dermatological treatment. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2010.512951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen MH, Cohen BJ, Shotkin JD, et al. Surgical prophylaxis of malignant melanoma. Annals of surgery. 1991;213:308–314. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199104000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brady MS, Oliveria SA, Christos PJ, et al. Patterns of detection in patients with cutaneous melanoma. Cancer. 2000;89:342–347. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000715)89:2<342::aid-cncr19>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epstein DS, Lange JR, Gruber SB, et al. Is physician detection associated with thinner melanomas? Jama. 1999;281:640–643. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.7.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kantor J, Kantor DE. Routine dermatologist-performed full-body skin examination and early melanoma detection. Archives of dermatology. 2009;145:873–876. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbasi NR, Shaw HM, Rigel DS, et al. Early diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma: revisiting the ABCD criteria. Jama. 2004;292:2771–2776. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.22.2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rigel DS, Friedman RJ, Kopf AW, et al. ABCDE--an evolving concept in the early detection of melanoma. Archives of dermatology. 2005;141:1032–1034. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.8.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berwick M, Begg CB, Fine JA, et al. Screening for cutaneous melanoma by skin self-examination. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1996;88:17–23. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carli P, De Giorgi V, Palli D, et al. Dermatologist detection and skin self-examination are associated with thinner melanomas: results from a survey of the Italian Multidisciplinary Group on Melanoma. Archives of dermatology. 2003;139:607–612. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.5.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pollitt RA, Geller AC, Brooks DR, et al. Efficacy of skin self-examination practices for early melanoma detection. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:3018–3023. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trolle L, Henrik-Nielsen R, Gniadecki R. Ability to self-detect malignant melanoma decreases with age. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:499–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher NM, Schaffer JV, Berwick M, et al. Breslow depth of cutaneous melanoma: impact of factors related to surveillance of the skin, including prior skin biopsies and family history of melanoma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2005;53:393–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Troya-Martin M, Blazquez-Sanchez N, Fernandez-Canedo I, et al. [Dermoscopic study of cutaneous malignant melanoma: descriptive analysis of 45 cases] Actas dermo-sifiliograficas. 2008;99:44–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carli P, de Giorgi V, Chiarugi A, et al. Addition of dermoscopy to conventional naked-eye examination in melanoma screening: a randomized study. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2004;50:683–689. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carli P, De Giorgi V, Crocetti E, et al. Improvement of malignant/benign ratio in excised melanocytic lesions in the ‘dermoscopy era’: a retrospective study 1997–2001. The British journal of dermatology. 2004;150:687–692. doi: 10.1111/j.0007-0963.2004.05860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piccolo D, Ferrari A, Peris K, et al. Dermoscopic diagnosis by a trained clinician vs. a clinician with minimal dermoscopy training vs. computer-aided diagnosis of 341 pigmented skin lesions: a comparative study. The British journal of dermatology. 2002;147:481–486. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noor O, 2nd, Nanda A, Rao BK. A dermoscopy survey to assess who is using it and why it is or is not being used. International journal of dermatology. 2009;48:951–952. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haenssle HA, Krueger U, Vente C, et al. Results from an observational trial: digital epiluminescence microscopy follow-up of atypical nevi increases the sensitivity and the chance of success of conventional dermoscopy in detecting melanoma. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2006;126:980–985. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Menzies SW, Emery J, Staples M, et al. Impact of dermoscopy and short-term sequential digital dermoscopy imaging for the management of pigmented lesions in primary care: a sequential intervention trial. The British journal of dermatology. 2009;161:1270–1277. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Risser J, Pressley Z, Veledar E, et al. The impact of total body photography on biopsy rate in patients from a pigmented lesion clinic. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2007;57:428–434. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Banky JP, Kelly JW, English DR, et al. Incidence of new and changed nevi and melanomas detected using baseline images and dermoscopy in patients at high risk for melanoma. Archives of dermatology. 2005;141:998–1006. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.8.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyer LE, Otberg N, Sterry W, et al. In vivo confocal scanning laser microscopy: comparison of the reflectance and fluorescence mode by imaging human skin. Journal of biomedical optics. 2006;11:044012. doi: 10.1117/1.2337294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Busam KJ, Hester K, Charles C, et al. Detection of clinically amelanotic malignant melanoma and assessment of its margins by in vivo confocal scanning laser microscopy. Archives of dermatology. 2001;137:923–929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ono I, Sakemoto A, Ogino J, et al. The real-time, three-dimensional analyses of benign and malignant skin tumors by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Journal of dermatological science. 2006;43:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajadhyaksha M, Gonzalez S, Zavislan JM, et al. In vivo confocal scanning laser microscopy of human skin II: advances in instrumentation and comparison with histology. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 1999;113:293–303. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerger A, Koller S, Kern T, et al. Diagnostic applicability of in vivo confocal laser scanning microscopy in melanocytic skin tumors. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2005;124:493–498. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerger A, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Langsenlehner U, et al. In vivo confocal laser scanning microscopy of melanocytic skin tumours: diagnostic applicability using unselected tumour images. The British journal of dermatology. 2008;158:329–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langley RG, Walsh N, Sutherland AE, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of in vivo confocal scanning laser microscopy compared to dermoscopy of benign and malignant melanocytic lesions: a prospective study. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland) 2007;215:365–372. doi: 10.1159/000109087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerger A, Wiltgen M, Langsenlehner U, et al. Diagnostic image analysis of malignant melanoma in in vivo confocal laser-scanning microscopy: a preliminary study. Skin Res Technol. 2008;14:359–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0846.2008.00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koller S, Wiltgen M, Ahlgrimm-Siess V, et al. In vivo reflectance confocal microscopy: automated diagnostic image analysis of melanocytic skin tumours. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 25:554–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiltgen M, Bloice M, Koller S, et al. Analytical and quantitative cytology and histology/the International Academy of Cytology [and] Vol. 33. American Society of Cytology; Computer-aided diagnosis of melanocytic skin tumors by use of confocal laser scanning microscopy images; pp. 85–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moncrieff M, Cotton S, Claridge E, et al. Spectrophotometric intracutaneous analysis: a new technique for imaging pigmented skin lesions. The British journal of dermatology. 2002;146:448–457. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haniffa MA, Lloyd JJ, Lawrence CM. The use of a spectrophotometric intracutaneous analysis device in the real-time diagnosis of melanoma in the setting of a melanoma screening clinic. The British journal of dermatology. 2007;156:1350–1352. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emery JD, Hunter J, Hall PN, et al. Accuracy of SIAscopy for pigmented skin lesions encountered in primary care: development and validation of a new diagnostic algorithm. BMC dermatology. 10:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-5945-10-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gutkowicz-Krusin D, Elbaum M, Jacobs A, et al. Precision of automatic measurements of pigmented skin lesion parameters with a MelaFind(TM) multispectral digital dermoscope. Melanoma research. 2000;10:563–570. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200012000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monheit G, Cognetta AB, Ferris L, et al. The performance of MelaFind: a prospective multicenter study. Archives of dermatology. 147:188–194. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kivela T. Diagnosis of uveal melanoma. Developments in ophthalmology. 49:1–15. doi: 10.1159/000330613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vogt M, Knuttel A, Hoffmann K, et al. Comparison of high frequency ultrasound and optical coherence tomography as modalities for high resolution and non invasive skin imaging. Biomedizinische Technik. 2003;48:116–121. doi: 10.1515/bmte.2003.48.5.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Giorgi V, Stante M, Massi D, et al. Possible histopathologic correlates of dermoscopic features in pigmented melanocytic lesions identified by means of optical coherence tomography. Experimental dermatology. 2005;14:56–59. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2005.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Welzel J. Optical coherence tomography in dermatology: a review. Skin Res Technol. 2001;7:1–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0846.2001.007001001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rallan D, Bush NL, Bamber JC, et al. Quantitative discrimination of pigmented lesions using three-dimensional high-resolution ultrasound reflex transmission imaging. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2007;127:189–195. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wachsman W, Morhenn V, Palmer T, et al. Noninvasive genomic detection of melanoma. The British journal of dermatology. 164:797–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10239.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cone CD., Jr The role of the surface electrical transmembrane potential in normal and malignant mitogenesis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1974;238:420–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1974.tb26808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Han A, Yang L, Frazier AB. Quantification of the heterogeneity in breast cancer cell lines using whole-cell impedance spectroscopy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:139–143. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alqabandi JA, Abdel-Motal UM, Youcef-Toumi K. Extracting cancer cell line electrochemical parameters at the single cell level using a microfabricated device. Biotechnology journal. 2009;4:216–223. doi: 10.1002/biot.200800321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aberg P, Birgersson U, Elsner P, et al. Electrical impedance spectroscopy and the diagnostic accuracy for malignant melanoma. Experimental dermatology. 20:648–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Har-Shai Y, Glickman YA, Siller G, et al. Electrical impedance scanning for melanoma diagnosis: a validation study. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2005;116:782–790. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000176258.52201.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Astbury WTSA. X-Ray Studies of the Structure of Hair, Wool, and Related Fibres. I. General. Trans R Soc Lond. 1931;230:75–101. [Google Scholar]

- 54.James VJ. Fiber diffraction of skin and nails provides an accurate diagnosis of malignancies. International journal of cancer. 2009;125:133–138. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ophir J, Cespedes I, Ponnekanti H, et al. Elastography: a quantitative method for imaging the elasticity of biological tissues. Ultrasonic imaging. 1991;13:111–134. doi: 10.1177/016173469101300201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hinz T, Wenzel J, Schmid-Wendtner MH. Real-time tissue elastography: a helpful tool in the diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma? Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 65:424–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ginat DT, Destounis SV, Barr RG, et al. US elastography of breast and prostate lesions. Radiographics. 2009;29:2007–2016. doi: 10.1148/rg.297095058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Herman C, Cetingul MP. Quantitative visualization and detection of skin cancer using dynamic thermal imaging. J Vis Exp. doi: 10.3791/2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ehmann R, Boedeker E, Friedrich U, et al. Canine scent detection in the diagnosis of lung cancer: Revisiting a puzzling phenomenon. Eur Respir J. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00051711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McCulloch M, Jezierski T, Broffman M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of canine scent detection in early- and late-stage lung and breast cancers. Integr Cancer Ther. 2006;5:30–39. doi: 10.1177/1534735405285096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Williams H, Pembroke A. Sniffer dogs in the melanoma clinic? Lancet. 1989;1:734. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Church J, Williams H. Another sniffer dog for the clinic? Lancet. 2001;358:930. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]