Abstract

The primary cilium is a solitary, immotile microtubule-based extension present on nearly every mammalian cell. This organelle has established mechanosensory roles in several contexts including kidney, liver, and the embryonic node. Mechanical load deflects the cilium, triggering biochemical responses. Defects in cilium function have been associated with numerous human diseases. Recent research has implicated the primary cilium as a mechanosensor in bone. In this review, we discuss the cilium, the growing evidence for its mechanosensory role in bone, and areas of future study. This article is part of a Special Issue entitled “Osteocytes”.

Keywords: Bone, Mechanotransduction, Mechanosensation, Osteocytes, Primary cilia

Introduction

The primary cilium is a single, immotile organelle that extends from the cell surface of nearly every mammalian cell. Though cilia were observed in protozoa and described over 300 years ago by Dutch lens maker Antony van Leeuwenhoek [1], primary cilia were first observed in mammalian cells just over a century ago in 1898 by Swiss anatomist Karl Zimmermann [2]. After observing it in several cell types, including rabbit kidney cells and human pancreatic cells, Zimmermann hypothesized a sensory role for the primary cilium. For over a century, this hypothesis remained largely ignored and this poorly understood organelle was believed to be of little functional importance [3]. Recently, renewed interest in this organelle has led to numerous studies and insights into the primary cilium structure and function.

In this review, we discuss primary cilia in the context of bone. This review begins with a brief overview of ciliopathies and primary cilia biology. The remainder of this review discusses recent advances in primary cilia research in bone, focusing on (1) the proposed role of osteocyte primary cilia, (2) related signaling pathways, and (3) new research tools and techniques. We wrap up the review by exploring future areas of research and unanswered questions.

Ciliopathies

Defects in primary cilia structure and function have been implicated in many disorders. The set of conditions related to these defects are known as ciliopathies. Because of the ubiquity of the primary cilium, defects can result in multisystemic dysfunction. Hallmarks of ciliopathies include renal disease, retinal degeneration, and cerebral anomalies [4]. The role of primary cilia in renal disease has been extensively studied. Murcia et al. provided the first clue in linking primary cilia to polycystic kidney disease in 2000 [5]. Using the Oak Ridge Polycystic Kidney mouse model for polycystic kidney disease, the authors found mutations in the Tg737 gene led to left-right axis defects and primary cilia defects. The authors named the protein encoded by the Tg737 gene Polaris. In addition to Polaris, other ciliary proteins, such as Kif3a, have later been associated with polycystic kidney disease [6]. On the other end of the spectrum, proteins, such as Polycystin-1 and Polycystin-2, linked to polycystic kidney disease have later been found to localize to the cilium [7]. A less studied but still prevalent feature of ciliopathies is skeletal abnormalities. The most common skeletal abnormalities observed include congenital defects of the extremities, craniofacial defects, and ossification disorders. Table 1 lists human ciliopathies with observed skeletal manifestations.

Table 1.

Human ciliopathies with skeletal abnormalities.

| Ciliopathy | Skeletal Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Alström syndrome |

|

[105] |

| Asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy |

|

[106] |

| Bardet-Biedl syndrome |

|

[96,107] |

| Ellis-van Creveld syndrome |

|

[108] |

| Joubert syndrome |

|

[109] |

| Mainzer-Saldino syndrome |

|

[110,111] |

| Meckel-Gruber syndrome |

|

[112] |

| Nephronophthisis |

|

[113,114] |

| Oral-facial-digital syndrome |

|

[115,116] |

| Polycystic kidney disease |

|

[117] |

| Senior-Loken syndrome |

|

[118] |

| Simpson Golabi Behmel syndrome |

|

[119] |

Primary cilia biology

The primary cilium is a microtubule-based structure similar to that of motile cilia and flagella in eukaryotic cells (Figure 1). All three consist of an axoneme of nine microtubule doublets extending from the basal body into the extracellular space. The microtubule doublets serve as the basis for structure and rigidity. In contrast to the motile cilium and flagellum, the primary cilium lacks two central microtubules, resulting in a 9+0 arrangement. The primary cilium also lacks other axonemal components, including radial spokes, Dynein arms and Nexin links [8]. These missing components are thought to reinforce the axoneme and increase stiffness, providing a possible explanation for the one order of magnitude increase in flexural rigidity observed in motile cilia compared to primary cilia.

Figure 1.

Schematic showing structure of primary cilium. The structure is segmented into the axoneme and basal body. Kinesin-2 motors (blue) regulate anterograde IFT while Dynein motors (red) regulate retrograde IFT along the microtubules (green) in the axoneme.

The primary cilium is formed and maintained through a process called intraflagellar transport (IFT). IFT is bidirectional trafficking system that transports proteins along the ciliary axoneme. Because primary cilia do not have the machinery to form proteins, all ciliary proteins are formed elsewhere in the cell and transported to the cilium through IFT. Kinesin-2 is responsible for anterograde movement while Dynein serves as the retrograde motor. Kif3a and Polaris, two proteins previously discussed for their implications in polycystic kidney disease, play integral roles in IFT. The anterograde motor Kinesin-2 is formed by Kif3a and Kif3b proteins [9]. Polaris forms part of a multi-protein IFT complex used in carrying other proteins [10,11]. Not surprisingly, Polaris is also known as Ift88.

Though primary cilia are ubiquitous, found on nearly all human cell types except those of myeloid and lymphoid lineages [12,13], primary cilia are not a constant presence on these cells. Instead, the occurrence of primary cilia is cell cycle-dependent and a dynamic process of assembly and resorption. Assembly of the cilium occurs in the interphase with the most cilia found on non-proliferating G0–G1 cells [13,14]. The mother centriole converts to the basal body anchoring the cilium as IFT and Kinesin-2 extend its length. Resorption of the cilium occurs prior to mitosis and entry of the cell cycle.

Proposed mechanosensory roles of primary cilia in osteocytes in vivo

It was not until a century after Zimmermann’s observations that the primary cilium’s role as a mechanosensor was established. Roth et al. demonstrated that the primary cilia of kidney cells bend in response to fluid flow [15]. Schwartz et al. then modeled this bending and proposed a sensory role as flow sensors in kidney cells [8]. Praetorius and Spring later supported this hypothesis with experimental evidence, demonstrating that cilia were mechanically sensitive to flow and served as part of a calcium signaling system [16]. Though evidence for the mechanosensory role of primary cilia is limited in bone compared to the kidney, primary cilia in osteocytes have been implicated in mechanosensing in vivo.

Bone Formation

Using Cre-lox technology to develop conditional knockout mice of Kif3a, two studies have shown decreased bone formation in mice with the Kif3a deletion. A conditional knockout of Kif3a is necessary because global knockouts are embryonically lethal 10 days postcoitum [17]. Temiyasathit et al. generated mice with an osteoblast- and osteocyte-specific knockout of Kif3a by breeding Colα1(I)2.3-Cre and Kif3afl/fl mice [18]. Abnormalities in skeletal morphology were not observed in embryos or mature mice with the conditional knockout. The authors then applied cyclic axial compressive loading to the forelimb of adult conditional knockout and control animals, resulting in significant increases in bone formation for both conditional knockout and control mice. Interestingly, the increases in loading-induced bone formation for the conditional knockout mice were significantly decreased compared to control mice, suggesting a mechanosensory role for primary cilia in bone.

Qui et al. also generated mice with an osteoblast- and osteocyte-specific knockout of Kif3a but used Osteocalcin-Cre and Kif3afl/null mice [19]. Osteocalcin is expressed in late-stage osteoblasts and osteocytes while Colα1(I)2.3 is expressed in earlier stage osteoblasts and osteocytes [20,21]. The null Kif3a allele increased the efficiency of the Kif3a deletion. In this study, the authors observed osteopenia in peri-adolescent conditional knockout mice compared to control mice. The authors also found decreased mRNA expression of osteogenic genes in tibiae of conditional knockout mice. Isolated and immortalized osteoblasts from the conditional knockout mice showed increased cell proliferation and impaired osteoblastic differentiation. In addition, these osteoblasts had decreased basal cytosolic calcium levels and impaired intracellular calcium responses to fluid flow shear stress. Collectively, these findings demonstrate a role for primary cilia in skeletal development.

Differentiation and proliferation

Recent studies suggest that in addition to bone turnover primary cilia play a role in cell differentiation and proliferation. Leucht et al. utilized Col1α1-Cre and Kif3afl/fl mice to generate conditional knockout of Kif3a in osteoblasts and investigate the role of primary cilia in bone repair [22,23]. No skeletal abnormalities or aberrations in skeletal patterning were detected in embryos, pups or adult mice. A mono-cortical tibial defect model was used in adult mice. Mice with conditional deletion of Kif3a had equivalent bone formation at the defect compared to control mice. In another experiment, an implant device was placed in the defect and micromotion was manually applied to the implant. The authors found increased Collagen type I expression in areas around the implant. The Collagen type I driven Cre then allowed for deletion of Kif3a in peri-implant cells. In the conditional knockout mice, there was almost no evidence of cell proliferation around the implant compared to control mice. Because other areas of the skeleton in the conditional knockout mice had evidence of cell proliferation, the authors concluded that the cells with dysfunctional cilia were able to proliferate but were insensitive to the implant micromotion. Further analysis of the peri-implant cells showed deletion of Kif3a led to a significantly reduced osteogenic response with a lack of peri-implant bone formation compared to the control. Taken together, the data suggest mechanical stimuli are early activators of the fracture healing response and primary cilia play an important role in sensing these stimuli.

In another important step in understanding the response to mechanical stimuli, Hoey et al. hypothesized a role for the primary cilium in the recruitment and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells [24]. The authors collected media from osteocytes after 24 hours of dynamic fluid flow and used this media to culture mesenchymal stem cells and osteoblasts. Mesenchymal stem cells cultured in the mechanically stimulated osteocyte conditioned media had increased expression of osteogenic genes when compared to statically cultured conditioned media while no significant changes in osteogenic gene expression in osteoblasts were observed. The authors then performed a siRNA-mediated knockdown of Ift88, reducing both protein expression and the number of ciliated cells [25]. Conditioned media from mechanically stimulated osteocytes treated with Ift88 siRNA led to no significant changes in osteogenic gene expression when compared to statically cultured conditioned media. However, osteogenic gene expression changes still occurred with the control, osteocytes treated with scrambled siRNA. Collectively, these results demonstrate a paracrine signaling mechanism between mechanically stimulated osteocytes and mesenchymal stem cells. The results further demonstrate that this signaling mechanism is mediated by primary cilia.

Of the four studies discussed in this section, three target Kif3a while one targets Ift88. Though deletion of Kif3a, a necessary component of IFT, has been linked to disruption of cilia formation and function [6,17], it has also been linked to non-ciliary functions. Corbit et al. used three separate methods of disrupting cilia formation to investigate the relationship between primary cilia and Wnt signaling [26]. One method entailed generating Kif3a−/− embryos. Constitutive phosphorylation of Dishevelled was measured by western blot analysis. The phosphorylation of Dishevelled led to a stabilization and accumulation of β-catenin. This abnormal accumulation overactivated the Wnt pathway. Interestingly, the other two methods of disrupting cilia, Ift88 and Ofd1 knockouts, did not affect Dishevelled phosphorylation. Ofd1 encodes a basal body protein required for cilia formation and defects in this gene lead to oral-facial-digital syndrome (Table 1) [27]. Taking these findings into account, it is unclear if results based on a Kif3a conditional knockout can be attributed to primary cilia. The recent availability of Ift88fl/fl animals will help address this issue and provide for a more precise investigation of the role of primary cilia in vivo [28,29].

Molecular mechanisms implicated in osteocyte primary cilia function

Pkd1

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease affects one in approximately 500 people, making it the most single gene disorder [30]. The two genes affected in this disease are Pkd1 and Pkd2, encoding Polycystin-1 and Polycystin-2, respectively (Figure 2). Recent studies have shown that conditional deletion of Pkd1 from osteoblasts and osteocytes led to decreases in loading-induced bone formation. In 2010, Xiao et al. investigated the role of Pkd1 in bone using Osteocalcin-Cre and Pkd1fl/m1Bei mice to generate mice with inactivated Pkd1 in late-stage osteoblasts and osteocytes [31]. Mice with this conditional inactivation had significantly decreased bone mineral density, bone volume fraction, and cortical thickness at 16 weeks. Ex vivo, the authors showed the conditional inactivation in osteoblasts led to increased proliferation rates as well as impaired osteoblastic differentiation. In 2011, Xiao et al. continued their investigation of Pkd1 more specifically in osteocytes by using a Dmp1 driven Cre with the same Pkd1 mouse [32–34]. The authors observed similar osteopenic skeletal phenotypes as with the conditional inactivation mice in their previous paper. Forelimbs of adult mice were loaded in axial compression, significantly reducing loading-induced bone formation and gene expression in mice with the conditional inactivation. However, this osteopenic phenotype was attenuated with age. The authors isolated osteoblasts from the mice for an ex vivo study of flow-induced calcium responses. The flow-induced increase in calcium was abrogated in cells with inactivation of Pkd1.

Figure 2.

Proposed Pkd1 cilia-mediated pathway. Polycystin-1 (green) and polycystin-2 (blue) form the Polcystin complex. This complex is thought to respond to flow by allowing an extracellular calcium influx.

In an effort to link Pkd1 and primary cilia, Qiu et al. generated a mouse with a double heterozygous knockout of Pkd1 and Kif3a [34]. A single heterozygous knockout of Pkd1 led to an osteopenic phenotype while a single heterozygous knockout of Kif3a resulted in no measured skeletal abnormalities. Further, the osteopenic phenotype was no longer observed in the double heterozygous knockout of Pkd1 and Kif3a. Based on these results, the authors proposed Kif3a deficiency rescued the Pkd1 deficiency and restoring osteogenesis. The authors hypothesized the role of the hedgehog signaling pathway in this rescue effect. Gli2 expression was significantly increased in single heterozygous Kif3a mice while Gli2 expression was significantly decreased in single heterozygous Pkd1 mice. The reduction in Gli2 expression was reversed in the double heterozygous mice. The group’s most recent study, discussed in a previous section, generated Kif3a deficient mice using Osteocalcin-Cre and Kif3afl/null mice [19]. Both studies used a mouse with a null allele and a floxed or normal allele of Kif3a. Similar effects in gene expression may be expected with similar genotypes. However, gene expression in bone and osteoblasts from Kif3afl/null mice in the most recent study were inconsistent with that of the single heterozygous Kif3a mice, Kif3a+/Δ.

Adenylyl cyclases

Adenylyl cyclases (AC) are enzymes that convert ATP to cyclic AMP, a ubiquitous second messenger [35,36]. Some isoforms of AC have previously been shown to localize to primary cilia in neuronal, renal and liver cells [37–40]. Kwon et al. showed that Adenylyl cyclase 6 (AC6) localized to primary cilia in osteocytes and osteoblasts [36]. In osteocytes, the authors measured a transient decrease in cyclic AMP after 2 minutes of oscillatory fluid flow. The authors then used Ift88-targeting siRNA in osteocytes to demonstrate that primary cilia are required for the flow-induced decrease in cyclic AMP. Using AC6-targeting siRNA, the authors showed that the flow-induced decrease in cyclic AMP was also mediated by AC6. From these data, Kwon et al. identify a potential molecular mechanism for primary cilia mechanotransduction in bone. A recent study by Lee et al. further implicates AC6 in bone mechanotransduction [41]. In an in vivo study, the authors used AC6 global knockout mice. No skeletal phenotype was measured in knockout mice. With exposure to axial compressive ulnar loading, deletion of AC6 led to significantly decreased loading-induced bone formation. Together these studies suggest a cilia-mediated role for AC6 in bone (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Proposed adenylyl cyclase cilia-mediated pathway. The flow-induced calcium influx inhibits adenylyl cyclase 6 (blue, AC6), which in turn leads to a decrease in cyclic AMP (green, cAMP) and a decrease in activated protein kinase A (purple, PKA).

Recently, Qiu et al. investigated the link between adenylyl cyclases and Pkd1 [42]. The authors used a shRNA knockdown of Pkd1 in osteoblasts and measured increased cell proliferation as well as impaired osteoblastic differentiation in Pkd1 deficient cells. These cells also had decreased basal cytosolic calcium levels in contrast to increased basal cytosolic cyclic AMP levels. Downstream of adenylyl cyclases and cyclic AMP is protein kinase A (PKA), which is activated by cyclic AMP [43]. Using a PKA inhibitor, H89, the changes in cell proliferation were fully restored while the impairment of osteoblastic differentiation was partially restored. Collectively, these data show Pkd1 downregulation affects osteoblast function through a cyclic AMP/PKA signaling pathway, suggesting an integration of the Pkd1 and adenylyl cyclase mechanisms.

Inversin

Wnt signaling plays a prominent role in regulating development and disease through the canonical β-catenin and non-canonical pathways [44]. Inversin is thought to function as a flow-regulated molecular switch between these pathways in the kidney (Figure 4) [30,45,46]. Cilia-mediated mechanotransduction has previously been suggested as a potential mechanism regulating Inversin expression and the switch between Wnt pathways [47]. Preliminary studies from our lab have shown that fluid flow increases Inversin expression in mesenchymal stem cells. Upregulation of Wnt5a expression with flow is consistent with previous work in mesenchymal stem cells that demonstrated the significance of non-canonical Wnt signaling in mechanically-induced osteogenic differentiation [48]. Taken together, Inversin may have a similar switch-like function in bone through a cilia-mediated mechanism.

Figure 4.

Proposed Inversin cilia-mediated pathway. Fluid flow upregulates Inversin (blue, Inv). Inversin forms a complex with cytoplasmic Dishevelled (green, Dsh), increasing its ubiquitination and essentially inhibiting the canonical Wnt pathway.

Development of new techniques and tools

Identifying primary cilia-specific proteins

Until recently isolating primary cilia was problematic. Techniques had been developed for sensory cilia but were unsuccessful for isolating with primary cilia in large part due to length [49,50]. Primary cilia, generally 10 μm in length or less, are considerably shorter than sensory cilia [25,51,52]. Previous studies indirectly identified ciliary proteins using comparative genomics and proteomics between ciliated and non-ciliated organisms [53–56]. Recently, Huang et al. developed two methods to isolate primary cilia with mechanical agitation [57,58]. The authors removed up to 70% of primary cilia from a monolayer of cholangiocytes. A chemical method was also developed by Raychowdhury and colleagues using high concentrations of calcium, which is thought to separate cilia [59,60]. An advantage of a mechanical isolation method is avoiding the potential effect of a chemical method on cellular processes [60].

New primary cilia-specific proteins have been identified using a combination of these primary cilia isolation techniques and proteomics. Ishikawa et al. isolated primary cilia from mouse kidney collecting duct cells using the chemical calcium-shock method described above [61]. The authors compared the resulting protein profile to that of cells treated with nocodazole and incubated at a cold temperature to prevent cilia formation. Using subtractive proteomics, the authors identified 195 candidate ciliary proteins, 45 of which were not previously identified as ciliary proteins. This study is an important step in identifying primary cilia-specific proteins. It remains unclear how this protein profile changes with disease and other manipulations. Identifying these changes may lead to new therapeutic targets for ciliopathies and other diseases where cilia have been implicated.

Modeling primary cilia mechanics

Using the small-rotation Euler-Bernoulli formulation, Schwartz et al. were the first to model primary cilia bending [8]. Exposing rat kangaroo kidney cells to flow, the authors estimated the flexural rigidity of the cilium to be on the order of 10−23 N·m2. With Stokes equations, Liu et al. developed a model with a more accurate description of the fluid flow around the cilium [50]. The authors approximated flow-induced shear force along the apical membrane and drag force along the cilium of rabbit kidney cells, finding that these forces are significantly lower than the force threshold to induce a calcium response in these cells. Rydholm et al. then developed a finite element model describing the relationship between flow-induced bending, shear stress and the release of intracellular calcium [62]. The authors applied flow to canine kidney cells and measuring an increase in calcium release after a 20s time delay. These authors attributed the delay in calcium signaling to the time required to reach maximal membrane stress. All three models are reviewed in depth by Hoey et al. [63].

Downs et al. sought to address shortcomings of the above studies and modeled primary cilia deflection using a large rotation formulation accounting for the rotation at the base of the cilium, the initial configuration of the cilium, and a more sophisticated computational model of the fluid flow profile [64]. Taking these parameters into account, the authors estimated flexural rigidity for mouse kidney cells to be on the order of 10−22 N·m2, an order of magnitude higher than calculated by Schwartz et al. [8].

These advances in modeling primary cilia mechanics have shed light on the dynamics of this organelle. Besschetnova et al. showed primary cilia length in mammalian epithelial and kidney cells changes in response to flow [65]. Rich and Clark showed chondrocyte cilia length changes in response to osmotic challenges [66]. Together these studies suggest that the primary cilium mechanosensory capacity is dynamic, adapting to its environment.

Outlook of primary cilia research in bone

Recent research has established a mechanosensory role for primary cilia in several contexts including kidney, liver, and the embryonic node. In bone however its role remains understudied considering its potential role as a mechanosensing organelle. We highlight several unanswered questions below.

With advances in identifying ciliary proteins and modeling primary cilia mechanics, primary cilia can be investigated at the molecular level with increasing detail and precision. Coupling these techniques with biochemical assays will enhance our understanding of cilia dynamics and the integration of mechanical stimuli and molecular mechanisms. Fluorescent indicators, for example, allow for simultaneously monitoring the dynamics of cilium bending and biochemical processes in real time and in living cells. Wheeler et al. used fluo-4, a fluorescent calcium-indicator dye, to capture spatiotemporal pattern of calcium signaling in the cytosol and flagellum of Chlamydomonas [67]. This spatiotemporal pattern has proven difficult to capture in primary cilia due to the small volume of the organelle. Fluorescent biosensors may be able to address this issue because they may be targeted to the cilium. Calcium and cyclic AMP are two second messengers with well-developed biosensors [68,69]. DiPilato and Zhang developed a cyclic AMP biosensor targeted to the plasma membrane by incorporating a targeting sequence at the N-terminus of the biosensor and measured cyclic AMP dynamics in human embryonic kidney cells [35]. Using the same strategy, biosensors can be specifically designed for the primary cilium by incorporating cilia targeting sequences. Several candidate sequences have already been identified [70–73] and the identification of new ciliary proteins may bring more candidate sequences to light.

Not only may fluorescent indicators allow us to simultaneously investigate mechanical stimuli and downstream molecular mechanisms, but also the dynamics of multiple signaling pathways. As discussed above, Qiu et al. suggested a link between Pkd1 and adenylyl cyclase pathways [42]. In addition to the changes in cyclic AMP, Qiu et al. showed that intracellular calcium basal levels and signaling changed with knockdown of Pkd1. Several isoforms of adenylyl cyclase are inhibited by calcium [74], including AC6 linked to primary cilia by Kwon et al. [36]. Nauli et al. further demonstrated that Polycystin-1 is required for flow-induced calcium signaling [75]. These studies demonstrate the complex nature of these pathways with cross-talk through calcium and cyclic AMP. With targeted biosensors for both cyclic AMP and calcium, future studies might capture the coupling of these second messengers, distinguishing signaling in the cytosol and in the ciliary microdomain.

Several unanswered questions remain regarding the osteocyte primary cilium microenvironment. Wasserman et al. estimated the pericellular space between the osteocyte body and lacunar wall to be 1 μm or less from fresh frozen bone. Primary cilia from cultured osteocytes are 2–9 μm in length [25,52]. The orientation of primary cilia remains unclear in this tight pericellular space in vivo. Further, it is unclear if this tight space allows for primary cilia bending observed in vitro [8,16,25,64]. Rich and Clark showed primary cilia are deeply invaginated in the chondrocytes [66]. They hypothesized this section of the cilium, the ciliary pocket, is as important as the projected section of the cilium to the cilium’s mechanosensory role. Imaging the osteocyte cilium in situ may resolve these questions about the cilium’s microenvironment but imaging has remained a challenge due to the fragility and small size of the organelle. Combining a transgenic animal with fluorescent cilia and serial section microscopy may address this challenge.

An area that has received surprisingly little attention is the clinical context and translation of primary cilia in bone. Table 1 is a partial list of ciliopathies with skeletal abnormalities. With the research in the skeletal implications of primary cilia still in its infancy, few studies have looked specifically for skeletal abnormalities in ciliopathy patients. The study by Ramirez et al. is a rare example [76]. The authors recognized that though previous clinical reports had suggested orthopaedic manifestations of Bardet-Biedl syndrome, patients with this syndrome had not had methodical orthopaedic evaluations. The evaluations resulted in several skeletal manifestations that may be used to distinguish Bardet-Biedl syndrome from other syndromes with overlapping features. In addition to more clinical examinations of ciliopathy patients, cells from these patients may be analyzed to determine any changes in cilium mechanics and downstream signaling. Cilia from these cells might also be isolated to determine changes in protein profiles with disease. Leveraging results from in vitro, animal and patient studies, new targets may be identified for clinical therapies.

In conclusion, this discussion highlighted the emerging role of the osteocyte primary cilia. The review began at the organism level with in vivo cilia data from both humans and animal models. It then focused in on mechanisms at the molecular level that have involved primary cilia and new tools that have furthered study at this level. Lastly, essential questions remaining in osteocyte primary cilia function were raised. Without question this is an exciting time for primary cilia research with critical insights yet to come.

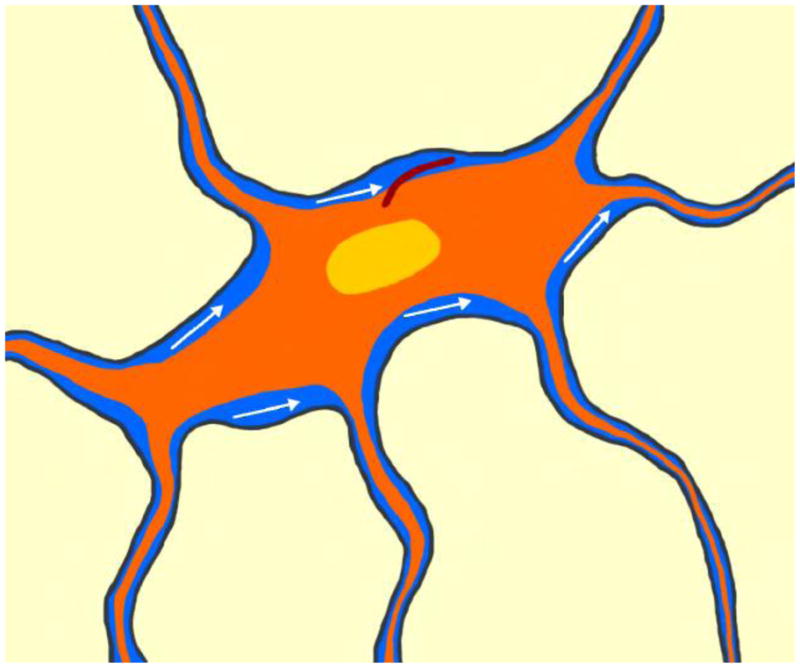

Figure 5.

Proposed microenvironment for the osteocyte and its primary cilium. With loading, interstitial fluid flow (blue) may bend the the primary cilium (brown) projecting from the osteocyte’s (orange) surface.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants (AR45156 and AR59038), a New York State Stem Cell Grant (N089-210), and a NSF Graduate Research Fellowship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.van Leeuwenhoek A, Hoole S. The select works of Antony Van Leeuwenhoek, containing his microscopical discoveries in many of the works of nature. Vol. 1800. G. Sidney; p. 348. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimmermann KW. Beitrage zur Kenntniss einiger Drusen und Epithelien. Archiv fur Mikroskopische Anatomie. 1898;52:552–706. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Federman M, Nichols G. Bone cell cilia: vestigial or functional organelles? Calcified tissue research. 1974;17:81–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02547216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waters AM, Beales PL. Ciliopathies: an expanding disease spectrum. Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany) 2011;26:1039–56. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1731-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murcia NS, Richards WG, Yoder BK, Mucenski ML, Dunlap JR, Woychik RP. The Oak Ridge Polycystic Kidney (orpk) disease gene is required for left-right axis determination. Development (Cambridge, England) 2000;127:2347–55. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.11.2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin F, Hiesberger T, Cordes K, Sinclair AM, Goldstein LSB, Somlo S, et al. Kidney-specific inactivation of the KIF3A subunit of kinesin-II inhibits renal ciliogenesis and produces polycystic kidney disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:5286–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0836980100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoder BK. The Polycystic Kidney Disease Proteins, Polycystin-1, Polycystin-2, Polaris, and Cystin, Are Co-Localized in Renal Cilia. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2002;13:2508–2516. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000029587.47950.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz EEA, Leonard ML, Bizios R, Bowser SS. Analysis and modeling of the primary cilium bending response to fluid shear. The American journal of physiology. 1997;272:F132–8. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.272.1.F132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Praetorius Ha, Spring KR. A physiological view of the primary cilium. Annual review of physiology. 2005;67:515–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.040403.101353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lucker BF, Miller MS, Dziedzic Sa, Blackmarr PT, Cole DG. Direct interactions of intraflagellar transport complex B proteins IFT88, IFT52, and IFT46. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:21508–18. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.106997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi T, Dynlacht BD. Regulating the transition from centriole to basal body. The Journal of cell biology. 2011;193:435–44. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201101005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wheatley DN. Primary cilia in normal and pathological tissues. Pathobiology: journal of immunopathology, molecular and cellular biology. 1995;63:222–38. doi: 10.1159/000163955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wheatley DN, Wanga M, Strugnell GE. Expression of primary cilia in mammalian cells. Cell biology international. 1996;20:73–81. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1996.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quarmby LM, Parker JDK. Cilia and the cell cycle? The Journal of cell biology. 2005;169:707–10. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200503053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roth KE, Rieder CL, Bowser SS. Flexible-substratum technique for viewing cells from the side: some in vivo properties of primary (9+0) cilia in cultured kidney epithelia. Journal of cell science. 1988;89 (Pt 4):457–66. doi: 10.1242/jcs.89.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Praetorius Ha, Spring KR. Bending the MDCK Cell Primary Cilium Increases Intracellular Calcium. Journal of Membrane Biology. 2001;184:71–79. doi: 10.1007/s00232-001-0075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marszalek JR, Ruiz-Lozano P, Roberts E, Chien KR, Goldstein LS. Situs inversus and embryonic ciliary morphogenesis defects in mouse mutants lacking the KIF3A subunit of kinesin-II. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:5043–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Temiyasathit S, Tang WJ, Leucht P, Anderson CT, Monica SD, Castillo AB, et al. Mechanosensing by the Primary Cilium: Deletion of Kif3A Reduces Bone Formation Due to Loading. PloS one. 2012;(7):e33368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qiu N, Xiao Z, Cao L, Buechel MM, David V, Roan E, et al. Disruption of Kif3a in osteoblasts results in defective bone formation and osteopenia. Journal of cell science. 2012 doi: 10.1242/jcs.095893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonewald LF. The amazing osteocyte. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2011;26:229–38. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robling AG, Castillo AB, Turner CH. Biomechanical and molecular regulation of bone remodeling. Annual review of biomedical engineering. 2006;8:455–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.8.061505.095721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leucht P, Monica SD, Temiyasathit S, Lenton K, Manu A, Longaker M, et al. Primary cilia act as mechanosensors during bone healing around an implant. Journal of orthopaedic research: official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society. n.d doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dacquin R, Starbuck M, Schinke T, Karsenty G. Mouse alpha1(I)-collagen promoter is the best known promoter to drive efficient Cre recombinase expression in osteoblast. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2002;224:245–51. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoey Da, Kelly DJ, Jacobs CR. A role for the primary cilium in paracrine signaling between mechanically stimulated osteocytes and mesenchymal stem cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2011;412:182–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.07.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malone AMD, Anderson CT, Tummala P, Kwon RY, Johnston TR, Stearns T, et al. Primary cilia mediate mechanosensing in bone cells by a calcium-independent mechanism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:13325–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700636104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corbit KC, Shyer AE, Dowdle WE, Gaulden J, Singla V, Chen M-H, et al. Kif3a constrains beta-catenin-dependent Wnt signalling through dual ciliary and non-ciliary mechanisms. Nature cell biology. 2008;10:70–6. doi: 10.1038/ncb1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrante MI, Zullo A, Barra A, Bimonte S, Messaddeq N, Studer M, et al. Oral-facial-digital type I protein is required for primary cilia formation and left-right axis specification. Nature genetics. 2006;38:112–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Connor AK, Kesterson Ra, Yoder BK. Generating conditional mutants to analyze ciliary functions: the use of Cre-lox technology to disrupt cilia in specific organs. 1. Elsevier; 2009. pp. 305–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haycraft CJ, Zhang Q, Song B, Jackson WS, Detloff PJ, Serra R, et al. Intraflagellar transport is essential for endochondral bone formation. Development (Cambridge, England) 2007;134:307–16. doi: 10.1242/dev.02732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simons M, Walz G. Polycystic kidney disease: cell division without a c(l)ue? Kidney international. 2006;70:854–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiao Z, Zhang S, Cao L, Qiu N, David V, Quarles LD. Conditional disruption of Pkd1 in osteoblasts results in osteopenia due to direct impairment of bone formation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:1177–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.050906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu Y, Xie Y, Zhang S, Dusevich V, Bonewald LF, Feng JQ. DMP1-targeted Cre Expression in Odontoblasts and Osteocytes. Journal of Dental Research. 2007;86:320–325. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fen JQ, Zhang J, Dallas SL, Lu Y, Chen S, Tan X, et al. Dentin matrix protein 1, a target molecule for Cbfa1 in bone, is a unique bone marker gene. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2002;17:1822–31. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.10.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiao Z, Dallas M, Qiu N, Nicolella D, Cao L, Johnson M, et al. Conditional deletion of Pkd1 in osteocytes disrupts skeletal mechanosensing in mice. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2011;25:2418–32. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-180299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DiPilato LM, Zhang J. The role of membrane microdomains in shaping beta2-adrenergic receptor-mediated cAMP dynamics. Molecular bioSystems. 2009;5:832–7. doi: 10.1039/b823243a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kwon RY, Temiyasathit S, Tummala P, Quah CC, Jacobs CR. Primary cilium-dependent mechanosensing is mediated by adenylyl cyclase 6 and cyclic AMP in bone cells. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2010;24:2859–68. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-148007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masyuk AI, Masyuk TV, Splinter PL, Huang BQ, Stroope AJ, LaRusso NF. Cholangiocyte cilia detect changes in luminal fluid flow and transmit them into intracellular Ca2+ and cAMP signaling. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:911–20. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bishop GA, Berbari NF, Lewis J, Mykytyn K. Type III adenylyl cyclase localizes to primary cilia throughout the adult mouse brain. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2007;505:562–71. doi: 10.1002/cne.21510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masyuk AI, Gradilone Sa, Banales JM, Huang BQ, Masyuk TV, Lee S-O, et al. Cholangiocyte primary cilia are chemosensory organelles that detect biliary nucleotides via P2Y12 purinergic receptors. American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2008;295:G725–34. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90265.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raychowdhury MK, Ramos AJ, Zhang P, McLaughin M, Dai X-Q, Chen X-Z, et al. Vasopressin receptor-mediated functional signaling pathway in primary cilia of renal epithelial cells. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology. 2009;296:F87–97. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90509.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee KL, Hoey DA, Spasic M, Tang T, Hammond HK, Jacobs CR. Adenylyl Cyclase 6 Mediates Loading-Induced Bone Adaptation In Vivo. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. n.d doi: 10.1096/fj.13-240432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qiu N, Zhou H, Xiao Z. Downregulation of PKD1 by shRNA results in defective osteogenic differentiation via cAMP/PKA pathway in human MG-63 cells. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2012;113:967–76. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iwami G, Kawabe J-i, Ebina T, Cannon PJ, Homcy CJ, Ishikawa Y. Regulation of adenylyl cyclase by protein kinase. A The Journal of biological chemistry. 1995;270:12481–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baksh D, Tuan RS. Canonical and non-canonical wnts differentially affect the development potential of primary isolate of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Journal of cellular physiology. 2007:817–826. doi: 10.1002/JCP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simons M, Gloy J, Ganner A, Bullerkotte A, Bashkurov M, Krönig C, et al. Inversin, the gene product mutated in nephronophthisis type II, functions as a molecular switch between Wnt signaling pathways. Nature genetics. 2005;37:537–43. doi: 10.1038/ng1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Otto Ea, Schermer B, Obara T, O’Toole JF, Hiller KS, Mueller AM, et al. Mutations in INVS encoding inversin cause nephronophthisis type 2, linking renal cystic disease to the function of primary cilia and left-right axis determination. Nature genetics. 2003;34:413–20. doi: 10.1038/ng1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Germino GG. Linking cilia to Wnts. Nature genetics. 2005;37:455–7. doi: 10.1038/ng0505-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arnsdorf EJ, Tummala P, Jacobs CR. Non-canonical Wnt signaling and N-cadherin related beta-catenin signaling play a role in mechanically induced osteogenic cell fate. PloS one. 2009;4:e5388. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mayer U, Küller A, Daiber PC, Neudorf I, Warnken U, Schnölzer M, et al. The proteome of rat olfactory sensory cilia. Proteomics. 2009;9:322–34. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Q, Tan G, Levenkova N, Li T, Pugh EN, Rux JJ, et al. The proteome of the mouse photoreceptor sensory cilium complex. Molecular & cellular proteomics: MCP. 2007;6:1299–317. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700054-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mitchell KaP, Szabo G, Otero ADS. Methods for the isolation of sensory and primary cilia--an overview. 1. Elsevier; 2009. pp. 87–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiao Z, Zhang S, Mahlios J, Zhou G, Magenheimer BS, Guo D, et al. Cilia-like structures and polycystin-1 in osteoblasts/osteocytes and associated abnormalities in skeletogenesis and Runx2 expression. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:30884–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604772200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pazour GJ. Comparative genomics: prediction of the ciliary and basal body proteome. Current biology: CB. 2004;14:R575–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pazour GJ, Agrin N, Leszyk J, Witman GB. Proteomic analysis of a eukaryotic cilium. The Journal of cell biology. 2005;170:103–13. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200504008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li JB, Gerdes JM, Haycraft CJ, Fan Y, Teslovich TM, May-Simera H, et al. Comparative genomics identifies a flagellar and basal body proteome that includes the BBS5 human disease gene. Cell. 2004;117:541–52. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00450-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Avidor-reiss T, Maer AAM, Koundakjian E, Polyanovsky A, Keil T, Subramaniam S, et al. Decoding cilia function: defining specialized genes required for compartmentalized cilia biogenesis. Cell. 2004;117:527–539. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00412-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang B, Masyuk T, LaRusso N. Isolation of primary cilia for morphological analysis. 1. Elsevier; 2009. pp. 103–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang BQ, Masyuk TV, Muff Ma, Tietz PS, Masyuk AI, Larusso NF. Isolation and characterization of cholangiocyte primary cilia. American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2006;291:G500–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00064.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raychowdhury MK, McLaughlin M, Ramos AJ, Montalbetti N, Bouley R, Ausiello Da, et al. Characterization of single channel currents from primary cilia of renal epithelial cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:34718–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507793200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Washburn KB. Comparison of Mechanical Agitation and Calcium Shock Methods for Preparation of a Membrane Fraction Enriched in Olfactory Cilia. Chemical Senses. 2002;27:635–642. doi: 10.1093/chemse/27.7.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ishikawa H, Thompson J, Yates JR, Marshall WF. Proteomic analysis of Mammalian primary cilia. Current biology: CB. 2012;22:414–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rydholm S, Zwartz G, Kowalewski JM, Kamali-Zare P, Frisk T, Brismar H. Mechanical Properties of Primary Cilia Regulate the Response to Fluid Flow. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology. 2010 doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00657.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hoey Da, Downs ME, Jacobs CR. The mechanics of the primary cilium: an intricate structure with complex function. Journal of biomechanics. 2012;45:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Downs ME, Nguyen AM, Herzog Fa, Hoey Da, Jacobs CR. An experimental and computational analysis of primary cilia deflection under fluid flow. Computer methods in biomechanics and biomedical engineering. 2012:37–41. doi: 10.1080/10255842.2011.653784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Besschetnova TY, Kolpakova-Hart E, Guan Y, Zhou J, Olsen BR, Shah JV. Identification of signaling pathways regulating primary cilium length and flow-mediated adaptation. Current biology: CB. 2010;20:182–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.11.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rich DR, Clark AL. Chondrocyte Primary Cilia Shorten in Response to Osmotic Challenge and are Sites for Endocytosis. Osteoarthritis and cartilage/OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wheeler GL, Joint I, Brownlee C. Rapid spatiotemporal patterning of cytosolic Ca2+ underlies flagellar excision in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. The Plant journal: for cell and molecular biology. 2008;53:401–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.DiPilato LM, Cheng X, Zhang J. Fluorescent indicators of cAMP and Epac activation reveal differential dynamics of cAMP signaling within discrete subcellular compartments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:16513–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405973101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Truong K, Sawano a, Mizuno H, Hama H, Tong KI, Mal TK, et al. FRET-based in vivo Ca2+ imaging by a new calmodulin-GFP fusion molecule. Nature structural biology. 2001;8:1069–73. doi: 10.1038/nsb728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tao B, Bu S, Yang Z, Siroky B, Kappes JC, Kispert A, et al. Cystin localizes to primary cilia via membrane microdomains and a targeting motif. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2009;20:2570–80. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009020188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Berbari NF, Johnson AD, Lewis JS, Askwith CC, Mykytyn K. Identification of Ciliary Localization Sequences within the Third Intracellular Loop of G Protein-coupled Receptors. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2008;19:1540–1547. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mazelova J, Astuto-Gribble L, Inoue H, Tam BM, Schonteich E, Prekeris R, et al. Ciliary targeting motif VxPx directs assembly of a trafficking module through Arf4. The EMBO journal. 2009;28:183–92. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Follit Ja, Li L, Vucica Y, Pazour GJ. The cytoplasmic tail of fibrocystin contains a ciliary targeting sequence. The Journal of cell biology. 2010;188:21–8. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200910096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guillou JL, Nakata H, Cooper DM. Inhibition by calcium of mammalian adenylyl cyclases. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:35539–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.50.35539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nauli SM, Alenghat FJ, Luo Y, Williams E, Vassilev P, Li X, et al. Polycystins 1 and 2 mediate mechanosensation in the primary cilium of kidney cells. Nature genetics. 2003;33:129–37. doi: 10.1038/ng1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ramirez N, Marrero L, Carlo S, Cornier AS. Orthopaedic manifestations of Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 2004;24:92–6. doi: 10.1097/00004694-200401000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Marshall JD, Bronson RT, Collin GB, Nordstrom AD, Maffei P, Paisey RB, et al. New Alström syndrome phenotypes based on the evaluation of 182 cases. Archives of internal medicine. 2005;165:675–83. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.6.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Beales PL, Bland E, Tobin JL, Bacchelli C, Tuysuz B, Hill J, et al. IFT80, which encodes a conserved intraflagellar transport protein, is mutated in Jeune asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy. Nature genetics. 2007;39:727–9. doi: 10.1038/ng2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tobin JL, Di Franco M, Eichers E, May-Simera H, Garcia M, Yan J, et al. Inhibition of neural crest migration underlies craniofacial dysmorphology and Hirschsprung’s disease in Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:6714–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707057105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ruiz-Perez VL, Ide SE, Strom TM, Lorenz B, Wilson D, Woods K, et al. Mutations in a new gene in Ellis-van Creveld syndrome and Weyers acrodental dysostosis. Nature genetics. 2000;24:283–6. doi: 10.1038/73508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Delous M, Baala L, Salomon R, Laclef C, Vierkotten J, Tory K, et al. The ciliary gene RPGRIP1L is mutated in cerebello-oculo-renal syndrome (Joubert syndrome type B) and Meckel syndrome. Nature genetics. 2007;39:875–81. doi: 10.1038/ng2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Perrault I, Saunier S, Hanein S, Filhol E, Bizet AA, Collins F, et al. Mainzer-Saldino Syndrome Is a Ciliopathy Caused by IFT140 Mutations. American journal of human genetics. 2012;90:864–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mortellaro C, Bello L, Pucci A, Lucchina AG, Migliario M. Saldino-Mainzer syndrome: nephronophthisis, retinitis pigmentosa, and cone-shaped epiphyses. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2010;21:1554–6. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181ec69bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chen C-P. Meckel syndrome: genetics, perinatal findings, and differential diagnosis. Taiwanese journal of obstetrics & gynecology. 2007;46:9–14. doi: 10.1016/S1028-4559(08)60100-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Popović-Rolović M, Calić-Perisíc N, Bunjevacki G, Negovanović D. Juvenile nephronophthisis associated with retinal pigmentary dystrophy, cerebellar ataxia, and skeletal abnormalities. Archives of disease in childhood. 1976;51:801–3. doi: 10.1136/adc.51.10.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Robins DG, French TA, Chakera TM. Juvenile nephronophthisis associated with skeletal abnormalities and hepatic fibrosis. Archives of disease in childhood. 1976;51:799–801. doi: 10.1136/adc.51.10.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Feather SA, Winyard PJ, Dodd S, Woolf AS. Oral-facial-digital syndrome type 1 is another dominant polycystic kidney disease: clinical, radiological and histopathological features of a new kindred. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation: official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 1997;12:1354–61. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.7.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.GORLIN RJ, PSAUME J. Orodigitofacial dysostosis--a new syndrome. A study of 22 cases. The Journal of pediatrics. 1962;61:520–30. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(62)80143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Turco AE, Padovani EM, Chiaffoni GP, Peissel B, Rossetti S, Marcolongo A, et al. Molecular genetic diagnosis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in a newborn with bilateral cystic kidneys detected prenatally and multiple skeletal malformations. Journal of Medical Genetics. 1993;30:419–422. doi: 10.1136/jmg.30.5.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lauweryns B, Leys A, Van Haesendonck E, Missotten L. Senior-Løken syndrome with marbelized fundus and unusual skeletal abnormalities. A case report Graefe’s archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv für klinische und experimentelle. Ophthalmologie. 1993;231:242–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00918849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Behmel a, Plöchl E, Rosenkranz W. A new X-linked dysplasia gigantism syndrome: identical with the Simpson dysplasia syndrome? Human genetics. 1984;67:409–13. doi: 10.1007/BF00291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]