Abstract

Viruses must be able to resist host innate responses, especially the type I interferon (IFN) response. They do so by preventing the induction or activity of IFN and/or by resisting the antiviral effectors that it induces. Poxviruses are no exception, with many mechanisms identified whereby mammalian poxviruses, notably, vaccinia virus (VACV), but also cowpox and myxoma viruses, are able to evade host IFN responses. Similar mechanisms have not been described for avian poxviruses (avipoxviruses). Restricted for permissive replication to avian hosts, they have received less attention; moreover, the avian host responses are less well characterized. We show that the prototypic avipoxvirus, fowlpox virus (FWPV), is highly resistant to the antiviral effects of avian IFN. A gain-of-function genetic screen identified fpv014 to contribute to increased resistance to exogenous recombinant chicken alpha IFN (ChIFN1). fpv014 is a member of the large family of poxvirus (especially avipoxvirus) genes that encode proteins containing N-terminal ankyrin repeats (ANKs) and C-terminal F-box-like motifs. By binding the Skp1/cullin-1 complex, the F box in such proteins appears to target ligands bound by the ANKs for ubiquitination. Mass spectrometry and immunoblotting demonstrated that tandem affinity-purified, tagged fpv014 was complexed with chicken cullin-1 and Skp1. Prior infection with an fpv014-knockout mutant of FWPV still blocked transfected poly(I·C)-mediated induction of the beta IFN (ChIFN2) promoter as effectively as parental FWPV, but the mutant was more sensitive to exogenous ChIFN1. Therefore, unlike the related protein fpv012, fpv014 does not contribute to the FWPV block to induction of ChIFN2 but does confer resistance to an established antiviral state.

INTRODUCTION

The major mammalian innate host response to virus infection is the type I interferon (IFN) system; consequently, many viruses have evolved mechanisms to evade or subvert it (1, 2). The prototypic mammalian poxvirus, vaccinia virus (VACV), encodes a number of proteins that have been shown to modulate the IFN system in diverse ways (reviewed by Perdiguero and Esteban [3]). They include double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)-binding protein E3 (4), α subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF-2α) mimic K3 (5), soluble IFN receptor mimic B18 (6, 7), Stat phosphorylation inhibitor H1 (8), and NF-κB activation suppressor K1 (9).

The genomes of the avipoxviruses are larger than those of the mammalian poxviruses. Although the genomes of two avipoxviruses, Fowlpox virus (FWPV; type species of the Avipoxvirus genus) and Canarypox virus (CNPV), have been sequenced (10, 11), there are no obvious orthologs of the VACV IFN modulators (such as E3L, K3L, and B18R), with the exception of an ortholog of H1 (12). The lack of E3L and K3L is a feature not unique to avipoxviruses—they are also absent from the now only remaining extant human poxvirus, molluscum contagiosum virus (MOCV), which causes chronic infection (13). Avipoxviruses also lack members, several of which are immunomodulatory (14–20), of the family of proteins found in VACV that share a structural fold with host apoptosis-controlling Bcl-2 (17). Avipoxviruses do encode potential orthologs of immunoregulators less frequently found in mammalian poxviruses, such as the interleukin-10 (IL-10) analogue encoded by CNPV (11) and found in mammalian poxviruses other than VACV, e.g., Orf virus (21), and transforming growth factor β orthologs initially found in FWPV (10) and CNPV (11) and then subsequently in deerpox virus (22). Ligand-binding studies have also identified a binding protein for chicken gamma IFN (IFN-γ) distinct from IFN-γ-binding proteins encoded by mammalian poxviruses (23).

We show here that FWPV is highly resistant to chicken type I IFN (ChIFN) and considerably more so than the artificially chicken cell-adapted strain of VACV, modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA), and that the resistance is due to an FWPV-encoded protein(s). We have used a broad-scale genetic screen to search for modulators, encoded by the FWPV genome, involved in subverting the IFN response. This gain-of-function screen involved construction of a library of chimeric MVA viruses, each carrying 4- or 8-kbp segments of the FWPV genome, which were then screened to identify a gene(s) conferring enhanced resistance to chicken type I IFN. The screen identified a member of a large poxvirus gene family that is particularly extensive in avipoxviruses, members of which had not been previously associated with subverting the IFN response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Primary chicken embryo fibroblasts (CEFs) derived from specific-pathogen-free (SPF)-quality 10-day-old embryos and provided by the Institute for Animal Health (Compton, Berkshire, United Kingdom) were grown in medium 199 supplemented with 10% tryptone phosphate broth (TPB), 10% newborn bovine serum, nystatin, and penicillin-streptomycin. Immortalized chicken fibroblast DF-1 cells (24) sourced from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Autogen Bioclear) and penicillin-streptomycin.

Throughout this study we have used the previously described, attenuated FWPV strain FP9, as well as its pathogenic European progenitor, HP-1 (12). VACV VTN, a Western Reserve (WR) recombinant virus expressing the porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) nucleoprotein in the thymidine kinase (TK) locus (25), was a gift from P. Britton (Institute for Animal Health, Compton, Berkshire, United Kingdom). Parental VACV MVA (II/85) from laboratory stocks was originally provided by Anton Mayr (Ludwig-Maximilians University, Munich, Germany). Recombinant VACV MVA-LZ, derived by insertion of the empty β-galactosidase selection plasmid pSC11 at the TK locus and known originally as MVA-SC11 (26), was provided by S. Gilbert, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom. The avirulent A7 (27) strain of Semliki Forest virus (SFV) was donated by J. Fazakerley (University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom).

Plasmids.

The ChIFN2 promoter reporter (pChIFN2lucter [28]) and the constitutive β-galactosidase reporter plasmid (pJATlacZ [29]) have been previously described, as has pEFPlink2, which uses the elongation factor Iα promoter to direct high levels of expression of cloned cDNAs, as originally described by Marais et al. (30).

Transfection of cells with poly(I·C) and assay of luciferase reporters.

Chicken DF-1 cells in 12-well plates were transfected with the chicken IFN type 2 promoter reporter (pChIFN2lucter) and the constitutive reporter plasmid pJATlacZ. They were sometimes additionally transfected with mammalian expression vector pEFPlink2 driving the overexpression of viral proteins or were used empty as a control vector. Following recovery for 24 h, cells were either left uninfected or infected with either wild-type fowlpox virus (FP9) or knockout virus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10. Following infection for 4 h, cells, when appropriate, were transfected with poly(I·C) (10 μg/ml) using Polyfect (Qiagen) or Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) reagent, as described by Childs et al. (28), and incubated for 16 h. Luciferase assays were carried out and data were normalized using β-galactosidase measurements.

Chicken IFN-α.

Preliminary studies were undertaken using recombinant chicken IFN-α (ChIFN1 [31]; P. Staeheli, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany). Subsequently, the ChIFN1 gene was amplified from CEF DNA by PCR and cloned into pEFPlink2 using NcoI and XbaI sites. This plasmid was transfected into 293 cells (9-cm plate); the supernatant, collected after 48 h of incubation, was centrifuged to remove cell debris and was titrated by 50% plaque reduction assay (32) using SFV A7 (27) on CEFs.

Construction of FWPV chimeric MVA.

The approach adopted for construction of FWPV chimeric MVA, after considerable optimization of the individual steps, involved using splice-overlap-extension PCR (SOE-PCR) to assemble 10-kbp linear recombination templates from four constituent parts: (i) 8-kbp (or 4-kbp) PCR fragments of the FWPV genome (amplified using high-fidelity Taq polymerase), flanked to the left by (ii) MVA sequences (positions 20406 to 20894), to the proximal right by (iii) a VACV p7.5 promoter upstream of the Escherichia coli gpt gene, and to the distal right by (iv) MVA sequences (positions 20916 to 21472). Parts iii and iv were preassembled by SOE-PCR before assembly of the complete linear recombination template from the resulting three components. The templates were purified by agarose gel electrophoresis, where, to avoid UV damage to the long templates, crystal violet rather than ethidium bromide was used as the stain.

The assembled FWPV genomic DNA selection cassettes were transfected into DF-1 cells previously infected with an MVA recombinant, MVA-LZ (which carries the E. coli lacZ gene inserted into the MVA thymidine kinase locus under the control of the VACV p11 promoter to facilitate plaque identification by staining for β-galactosidase). Recovered viruses were bulk passaged three times in CEFs under mycophenolic acid selection (in the presence of xanthine and hypoxanthine) for the gpt gene. Viral genomic DNA was then extracted and analyzed by PCR to confirm recombination of the FWPV genomic insert and loss of parental virus. Internal primers for the overlapping FWPV fragments were used for recombinant-specific PCR, together with MVA flanking primers to detect the presence of residual parental virus (with the larger recombinant-specific product being outcompeted by any smaller parent virus-specific product). If parental MVA-LZ remained at this stage, the chimeras were subjected to plaque purification. Some chimeras made with 8-kbp FWPV inserts returned PCR products shorter than expected or no products at all. Such viruses were not further characterized but were labeled “unstable.”

Single FWPV gene recombinant MVAs, each carrying one gene from the FIR1 locus, were constructed by SOE-PCR using single-gene primers (012 forward, CATAATACAAGGCACTATGTCCTTATTTTCTTCCGAACCTACC; 012 reverse, GTATTCTGGAGGCTGCATCCTTATTAAACCCGGAAATGTG; 013 forward, CATAATACAAGGCACTATGTCCAACGCATTTTTACCGTATTG; 013 reverse, GTATTCTGGAGGCTGCATCCTGAAGAAGATCTCCCTTATTG; 014 forward, CATAATACAAGGCACTATGTCCCGTAACTCTTGTTTTCATTTTTC; and 014 reverse, GTATTCTGGAGGCTGCATCCACATCAGCAGTTTTATTTTTG).

Construction of knockout and knock-in recombinant FWPV.

To construct knockout FWPV, SOE-PCR (using high-fidelity Taq polymerase) was used to assemble linear recombination templates from three constituent parts: approximately 350-bp PCR fragments of the FWPV genome from either side, fragments i and ii, of the center of the target gene, disrupted in the middle (fragment iii) by a VACV p7.5 promoter upstream of the E. coli gpt gene. The templates were purified by agarose gel electrophoresis and transfected into CEFs previously infected with FWPV FP9. Recovered viruses were bulk passaged three times in CEFs under mycophenolic acid selection (in the presence of xanthine and hypoxanthine) for the gpt gene and then plaque purified. Viral genomic DNA was then extracted and analyzed by PCR to confirm disruption of the target gene and loss of parental virus. Primers used were 5′-CGAACGTAGATTCCTACACTC and 5′-TGATAAATTACAACTATTAAC for fpv012 5′-ATTATGAAAACCACGAAAGTC and 5′-AACGTCTATCAGAACCTAAAG for fpv014.

To construct knock-in viruses expressing full-length or C-terminally deleted tandem affinity-purified (TAP)-tagged fpv014, transient dominant plasmids pUC13-FL014TAP and pUC13-CtDel014TAP were constructed in two steps. First, the 400-bp 3′ flanking sequence of fpv014 was amplified by PCR and cloned into the poxvirus transient dominant TAP vector pUC13TAP (from G. Smith), such that the 3′ flanking sequence was downstream of the TAP tag, generating the intermediate plasmid pUC13TAP014-3′. Subsequently, full-length (FL) or C-terminally deleted (CtDel) fpv014 (minus the stop codon) and 400 bp of upstream sequence were amplified by PCR and cloned into pUC13TAP014-3′ so that the fpv014 open reading frame (ORF) was fused in frame with the TAP tag. Constructs were sequenced to ensure that no errors had been introduced.

Recombinant TAP-tagged fpv014 viruses were generated by transfection of the constructs into CEFs infected with a mutant FWPV FP9 strain from which the parental fpv014 was previously deleted by the transient dominant selection method (33). The knock-in mutants were then isolated by the transient dominant selection method under mycophenolic acid selection (in the presence of xanthine and hypoxanthine) for the gpt gene. Recombinant viruses were checked by PCR for the presence of the FL or CtDel fpv014 genes (data not shown).

Plaque reduction assays.

CEFs were pretreated for 16 to 18 h with ChIFN1 diluted in growth medium with 2% newborn bovine serum (Gibco). The medium was aspirated, and cells were infected with about 50 PFU per well. After 90 min incubation, excess virus was aspirated and solid overlay containing 1% agarose was added to the cells. Plaques were fixed with 10% formaldehyde and stained with 20% crystal violet in 20% ethanol at 30 h (SFV), 3 days (VACV), or 4 days (MVA and FWPV) postinfection, counted, and expressed as a percentage of the mean number (n = 3) of plaques formed in mock-treated wells. LacZ-positive viruses were visualized by addition of solid overlay containing X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactopyranoside; 0.4 mg ml−1).

RNA extraction and processing of samples.

RNA was extracted from cells using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. On-column DNA digestion was performed using RNase-free DNase (Qiagen) to remove contaminating genomic DNA. RNA samples were quantified using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) and checked for quality using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). All RNA samples had an RNA integrity number (RIN) of ≥9.6.

RT-PCR and qRT PCR.

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using Mesa Green quantitative PCR (qPCR) MasterMix Plus for SYBR Assay I dTTP (Eurogentec) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A final volume of 10 μl per reaction mixture was used with 1 μl cDNA diluted 1:10 in nuclease-free H2O as the template. Primers were used at a final concentration of 300 nM. qPCR was performed on an ABI-7900HT Fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) using the following program: 95°C for 5 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 57°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 20 s; 95°C for 15 s; and 60°C for 15 s.

The qRT-PCR primer pairs (GGCACTGTCAAGGCTGAGAA and TGCATCTGCCCATTTGATGT for the chicken GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) gene, TGCTCTCCAGGGGTGCGTTACC and TAGCGCCGTGTTCCAACAGCG for fpv014, GTGTTCACGCCAAAGTAG and AGTAGGTTCTTCGTCAGATG for fpv100, ACCTCAAACAACCTCATC and GTTAATACTTGTGACTGCTG for fpv168) were validated by generating standard curves using PCR products corresponding to each gene. A 10-fold dilution series was made for each PCR product, and 1 μl was used with the Mesa Green qPCR MasterMix. Threshold cycle (CT) values were analyzed using SDS v2.3 software (Applied Biosystems). The slopes of the standard curves were used to identify the amplification efficiencies (E) of the qRT-PCR primer pairs, using the equation 10(−1/slope) − 1. Only qRT-PCR primer pairs with efficiencies of 90 to 110% were used further. The linear correlation coefficient (R2) was used to assess the linearity of the standard curve. Standard curves with R2 values of >0.985 were used.

Data were analyzed using SDS v2.3 and RQ Manager v1.2 software (Applied Biosystems). All target gene expression levels were calculated relative to the expression levels of the reference gene, the GAPDH gene, which were shown to remain constant over 24 h in uninfected and FP9-infected cells, and the target gene expression level in control CEFs, using the comparative CT method (also referred to as the 2−ΔΔCT method).

Tandem affinity purification.

FPV014 was cloned into a TAP-tagging vector (a kind gift of B. Ferguson) comprising a pcDNA4-TO (Invitrogen) backbone and a C-terminal Strep-FLAG-TAP tag (34). C-terminal TAP (CTAP)-tagged 014 was transfected into DF1-TR cells, and the resulting transformants were selected using blasticidin S and zeocin, generating a CTAP014-inducible cell line. Twenty T175 flasks of CTAP014 were grown, and expression of 014 was induced in 10 of them by the addition of doxycycline. Twenty-four hours following induction, cell lysates were made and sequential immunoprecipitations was carried out, first, with Strep-Tactin beads (IBA) and, second, with FLAG beads (Sigma). Final elutions were concentrated using a 3,000-molecular-weight-cutoff ultrafiltration device (Millipore), and samples were run on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel and stained using Coomassie blue. Protein bands that appeared in the induced and not the uninduced sample were excised and submitted for tandem mass spectrometry at the CISBIO mass spectrometry core facility (Imperial College London, managed by Paul Hitchen).

RESULTS

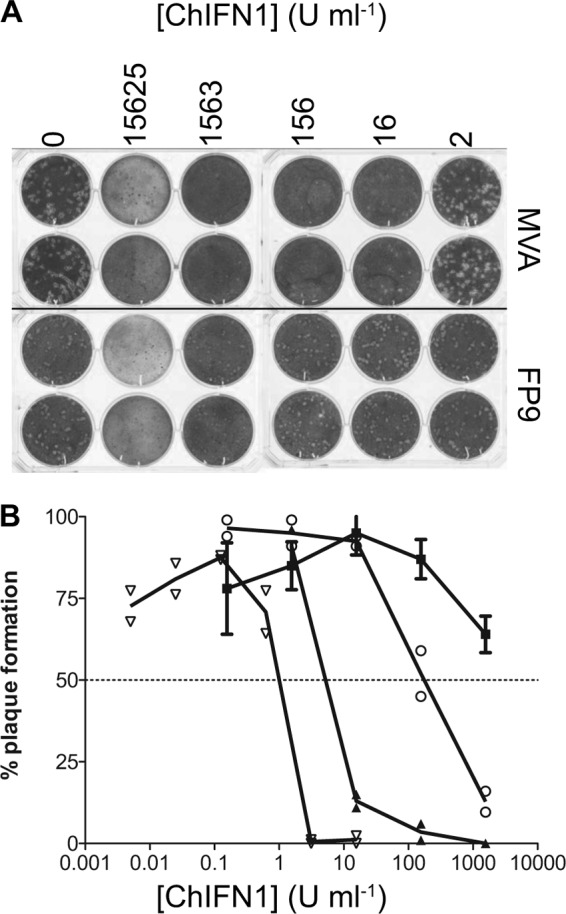

Fowlpox virus is resistant to the antiviral effects of chicken type I IFN.

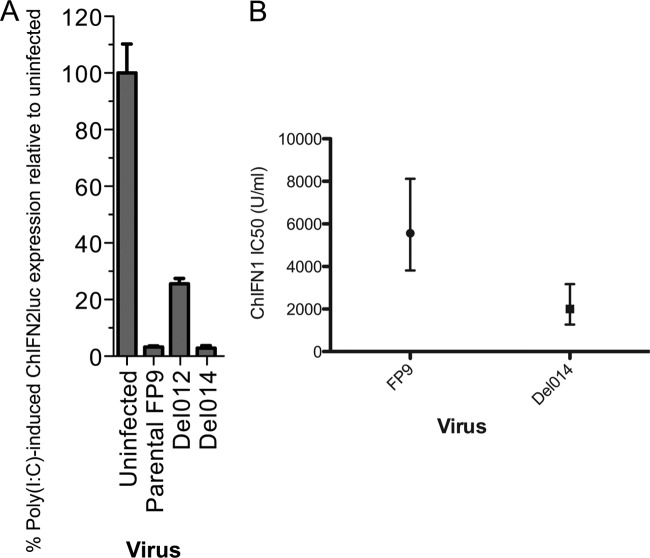

The sensitivity of FWPV FP9 replication to exogenous ChIFN was measured by plaque reduction on primary chicken embryo fibroblasts (CEFs) in the presence of recombinant ChIFN1. In our preliminary studies in CEFs, the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) for the control virus, Semliki Forest virus (SFV) A7 (27), was by definition 1 U ml−1, while that for VACV WR (VTN) was 176 U ml−1 (Fig. 1). VACV MVA, which was derived by extensive CEF passages (more than 500), during which it underwent considerable deletion of genomic sequences relative to its parental strain, chorioallantois vaccinia virus Ankara (35–37), had an IC50 of only 7 U ml−1. FP9, however, proved far more resistant (Fig. 1), such that the number of plaques was reduced by only 36% at the highest concentration of ChIFN used (1,563 U ml−1). The ChIFN used in this preliminary study caused some cytotoxicity at high concentrations (Fig. 1A), so the IC50 for FP9 could initially be estimated only upon extrapolation by nonlinear regression, yielding a tentative figure of 2,570 U ml−1.

Fig 1.

Sensitivity of viruses to recombinant ChIFN1. Plaque reduction assays were performed using CEFs infected with Semliki Forest virus, FWPV FP9, or VACV VTN or MVA in the presence of recombinant ChIFN1. (A) Photograph of crystal violet-stained CEFs showing titration of ChIFN1 inhibition of FP9 and MVA plaque formation. (B) Graph showing plaque production as a function of ChIFN1 concentration. The dotted line indicates the 50% reduction endpoint. Plaque formation is expressed as a percentage of plaques formed in mock-treated wells (mean of n = 3). Each point represents an individual well, except for FP9, where points are the mean (4 wells from 2 independent experiments) ± 1 SD. Symbols: squares, FP9; circles, VACV VTN; closed triangles, MVA II/85; open inverted triangles, SFV A7 (27).

Identification of FWPV chimeric MVA with enhanced resistance to ChIFN1.

The observation that MVA is almost 400-fold more sensitive to the antiviral effects of ChIFN1 than FP9 (Fig. 1) presented the possibility of a gain-of-function genetic screen of the FWPV genome, using MVA as a recipient, to attempt to identify the gene(s) involved in the enhanced resistance of FP9 to ChIFN1.

A panel of 63 MVA-FWPV chimeras was generated, as described in Materials and Methods, together spanning much of the FP9 genome in 4- or 8-kbp inserts (Fig. 2A) inserted close to deletion II of MVA (35) in an intergenic region midway between the end of MVA023L and the start of MVA021L. The design strategy foresaw a tiling path of 8-kbp fragments overlapping by 4 kbp; but not all chimeras were isolated, and some (which we define as unstable) proved to have inserts smaller than expected, as determined by PCR analysis, possibly due to competition between equivalent VACV and FWPV proteins. The library was evaluated to cover 85% of the FWPV ORFs (with 64% of the ORFs in one or more viruses).

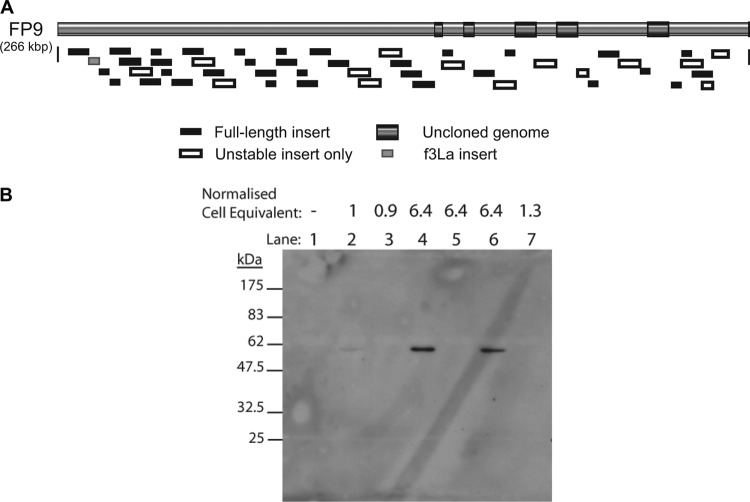

Fig 2.

Characterization of the FWPV chimeric MVA library. (A) Distribution on the FWPV FP9 genome of fragments inserted in the chimeric MVA library. The integrity of FWPV inserts was examined by PCR, using internal primers from the overlapping fragments with primers flanking the insertion site. Inserts that were shorter than expected were labeled “unstable.” Where duplicate viruses containing a particular fragment were recovered, the fragment is classified here as a full-length insert if at least one derived recombinant virus was of the anticipated size. Regions of the FP9 genome that were not present in the recombinant MVA library are highlighted as “uncloned genome.” The drawing is to scale. (B) Expression of fpv191 by MVA chimeras MVA-f50a and MVA-f50c. Lysates of uninfected or infected CEFs were subject to 10% SDS-PAGE and then immunoblotted using primary monoclonal antibody DE9 (38) at 1 in 200 and secondary goat anti-mouse IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) at 1 in 25,000. Lane 1, uninfected CEFs; lane 2, FP9-infected CEFs; lane 3, MVA-LZ-infected CEFs; lane 4, MVA-f50a-infected CEFs; lane 5, MVA-f50b-infected CEFs; lane 6, MVA-f50c-infected CEFs; lane 7, MVA-fC2b-infected CEFs. The amount of cell lysate loaded is expressed relative to that for the FP9-infected lysate (lane 2).

Although poxvirus promoters from VACV have been shown to function in cells infected by FWPV and vice versa, the ability of an MVA chimera to express an FWPV protein from its cognate promoter in the inserted FWPV genomic DNA was demonstrated by Western blotting with monoclonal antibody (MAb) DE9 and extracts from cells infected with chimeras. MAb DE9 recognizes the 63-kDa FWPV equivalent of VACV p4c, encoded by fpv191 (38), located in fragment 50 of the chimeric library. Three independent chimeras (MVA-f50a, -b, and -c) were isolated following separate transfections with fragment 50. Chimeras MVA-f50a and MVA-f50c but not unstable chimera MVA-f50b or control chimera MVA-fC2b showed strong expression of fpv191 (Fig. 2B).

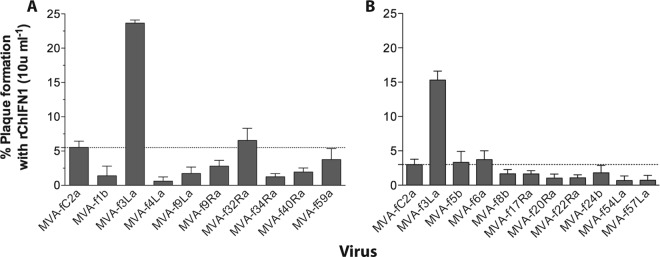

A total of 28 of the chimeras (none of which were classified as unstable) were screened by plaque reduction assay for enhanced resistance to low titers of ChIFN1 (10 to 16 U ml−1). Data from the screening of 18 such chimeras are shown in Fig. 3. Chimera MVA-f3La was readily identified as having significantly higher resistance than the control and other chimeras, whether screened as third-bulk-passage (Fig. 3A) or plaque-purified (Fig. 3B) virus. Only one other chimera, MVA-f6b, demonstrated resistance to ChIFN1 significantly higher than that of the control (but less than that of MVA-f3La; data not shown). It carried an 8-kbp locus that we named fowlpox virus IFN regulator 2 (FIR2), comprising positions 23791 to 32167 of the FWPV FP9 sequence with GenBank accession number AJ581527 (12) and spanning ORFs fpv022 to fpv026 inclusive, all of which are transcribed from right to left. Chimera MVA-f3La carried only a 4-kbp segment of the FWPV genome (positions 11900 to 16043 of the FP9 sequence), spanning three ORFs (fpv012 to fpv014 inclusive, all of which are transcribed from right to left). We named this genomic locus FIR1.

Fig 3.

Screening of FWPV chimeric MVA for enhanced resistance to ChIFN1. CEFs were pretreated in triplicate with ChIFN1 (10 U ml−1) or mock treated with DMEM–2% FBS for 18 h. The medium was aspirated, and cells were infected with chimeric viruses at 100 to 300 (A) or 50 to 200 (B) PFU/well. Virus was aspirated after 90 min, and semisolid overlay was added. A second overlay containing X-Gal was added at 3 days postinfection. Plaque formation for each virus in ChIFN1-treated wells is expressed as the mean (n = 3, ± SEM) percentage relative to that for mock-treated wells. Separate experiments are shown in panels A and B. The screen shown in panel A used third-bulk-passage, mycophenolic acid-selected MVA-f3La (subsequently found to contain residual MVA-LZ), but that shown in panel B used fourth-passage, plaque-purified MVA-f3La (found to be free of parental MVA-LZ). rChIFN1, recombinant ChIFN1.

Identification of an FWPV gene contributing to virus resistance to ChIFN1.

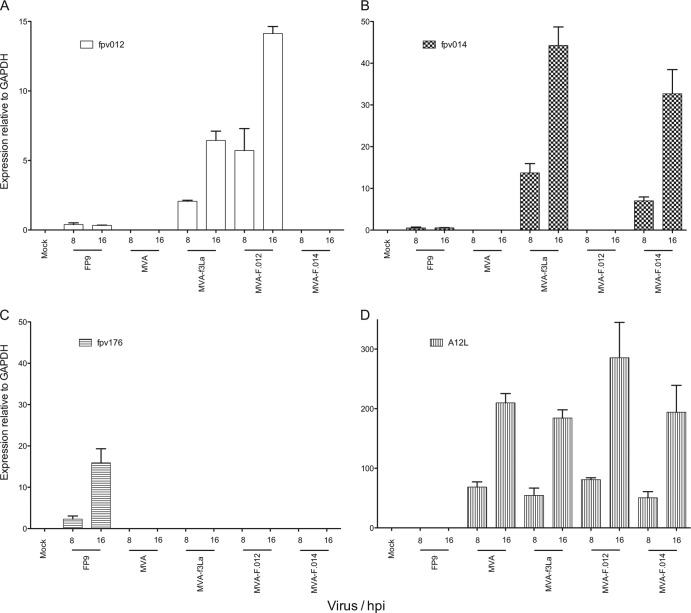

First, expression of FWPV genes fpv012 and fpv014 in CEFs infected with MVA-f3La but not with control MVA-fC2a was demonstrated by qRT-PCR; in fact, both FWPV genes were expressed at higher levels from the chimera than from donor FP9 (Fig. 4). Then, recombinant MVAs, each carrying just a single gene from the FIR1 locus, were constructed by SOE-PCR. Expression of fpv014, as determined by qRT-PCR, was lower in MVA-F.014 (13- and 60-fold relative to that in FP9 at 8 and 16 h postinfection [hpi], respectively) than in MVA-f3La (26- and 81-fold, respectively), while fpv012 expression was higher in MVA-F.012 (15- and 43-fold, respectively) than in MVA-f3La (5- and 20-fold, respectively) (Fig. 4).

Fig 4.

qRT-PCR analysis of the expression of FWPV insert-specific genes by first- and second-stage FWPV chimeric MVA. Expression of mRNA specific for fpv012 and fpv014 in FP9-infected and control (MVA-fC2a) or FWPV chimeric MVA-infected CEFs was assayed by qRT-PCR and normalized against that for chicken GAPDH. MVA-f3La is a first-stage chimera carrying the FIR1 locus; MVA-F.012 and MVAF.014 are second-round recombinants carrying only fpv012 and fpv014, respectively. Expression of mRNA specific for MVA A12L and the FWPV equivalent of A12L (fpv176) in FP9- and chimeric MVA-infected CEFs as vector-specific controls was assayed by qRT-PCR and normalized against that for chicken GAPDH. (A) fpv012; (B) fpv014; (C) fpv176 bars; (D) A12L. The mean and standard deviation at 8 and 16 h postinfection (hpi) are plotted from three independent experiments. Note the differences in the y-axis scales.

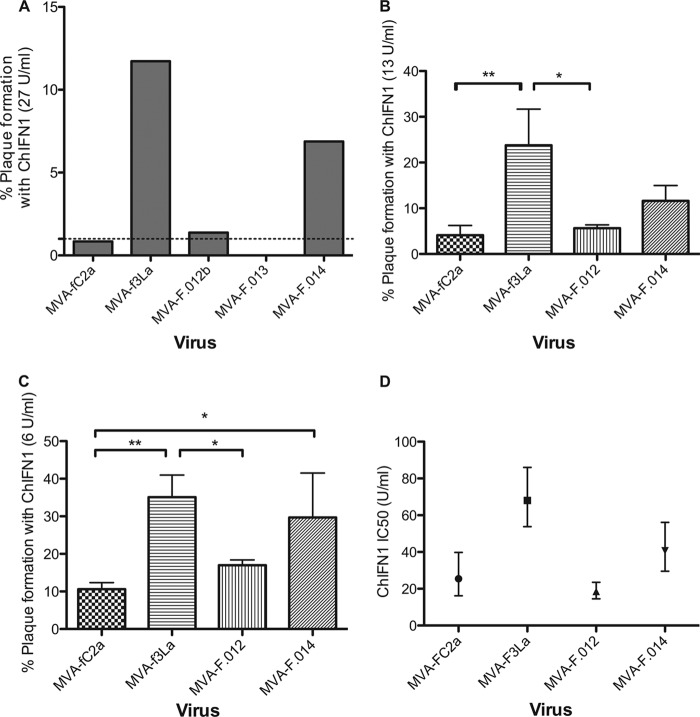

The single-gene recombinant MVAs were similarly screened for enhanced resistance to ChIFN1 by plaque reduction assay. Preliminary experiments (for example, see the results in Fig. 5A) showed that fpv013 did not contribute to enhanced ChIFN1 resistance. Subsequent experiments demonstrated that plaque formation by MVA-f3La, under different concentrations of ChIFN1, was significantly higher than that by the control MVA-fC2a and the recombinant (MVA-F.012) expressing only fpv012 but not the recombinant (MVA-F.014) expressing only fpv014 (Fig. 5B and C). MVA-F.014 consistently formed plaques at a considerably higher efficiency than MVA-fC2a and MVA-F.012, but the results did not reach statistical significance. The IC50 of ChIFN1 for each of the viruses was therefore derived in a further experiment. The IC50 for MVA-f3La (68 U ml−1) was significantly higher than the IC50s for MVA-fC2a (25 U ml−1) and MVA-F.012 (18 U ml−1). Although the IC50 for MVA-F.014 (41 U ml−1) was not significantly higher than that for MVA-fC2a, it was significantly higher than that for MVA-F.012 (Fig. 5D). It is therefore only fpv014 that consistently shows a contribution toward the resistance to ChIFN1 observed in MVA-f3La.

Fig 5.

Screening and characterization of second-round chimeric MVA to identify the FIR1 gene responsible for enhanced resistance to ChIFN1. CEF cells (in 9-cm2 dishes) were incubated with 1 ml DMEM–2% FBS with or without ChIFN1 at 27 (A), 13 (B), or 6 (C) U ml−1 for 18 h. The medium was aspirated, and cells were infected at 90 to 180 PFU/well. All viruses except control MVA-fC2a were plaque purified. MVA-f3La is a first-stage chimera carrying the FIR1 locus; MVA-F.012, MVA-F.013, and MVAF.014 are second-round recombinants carrying only fpv012, fpv013, and fpv014, respectively. Except in panel A, which is an example of several experiments, the numbers of plaques formed in the ChIFN1-treated wells were expressed as a percentage of the mean (n = 3) number of plaques formed in mock-treated wells. (D) Plaque reduction assays were performed on FWPV chimeric MVA over a range of ChIFN concentrations from 5 to 200 U ml−1. IC50 values for ChIFN1 with each of the viruses were derived in Prism software (GraphPad) using nonlinear fits of the log-converted ChIFN1 concentrations against the percentage of normalized plaque responses. IC50 values are plotted with 95% confidence intervals. P values were determined by two-way analysis of variance: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Expression of fpv014 by FWPV.

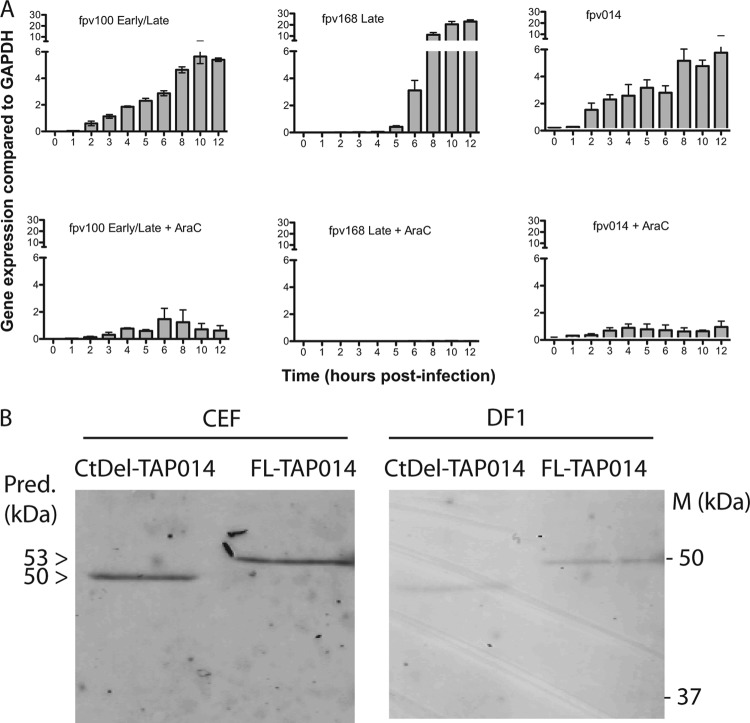

Analysis of fpv014 mRNA expression by qRT-PCR revealed that its levels and kinetics in CEFs infected with parental FWPV FP9 are comparable to those of fpv100 (Fig. 6A), with expression being clearly detectable at 2 h (in contrast to that of late gene fpv168) and increasing to 8 h in an AraC-sensitive manner (though, in contrast to the highly expressed late gene fpv168, low-level expression was still detectable in the presence of AraC). Gene fpv100 is an ortholog of VACV E4L (VACWR060), which encodes RNA polymerase subunit RPO30 and shows group E1.1 expression kinetics (39).

Fig 6.

Characterization of expression of fpv014 in FWPV. (A) Analysis of the kinetics of expression of mRNA specific for fpv014 in wild-type FWPV was performed by qRT-PCR, using as controls FWPV genes fpv100 (ortholog of VACV E4L; RNA polymerase subunit RPO30) and fpv168 (ortholog of VACV A4L). Expression in the absence and presence of poxviral DNA replication inhibitor AraC was normalized against that for chicken GAPDH. Means and standard deviations are plotted from three independent experiments. (B) Expression of TAP-tagged fpv014, either FL or CtDel, inserted back into the native locus in FWPV FP9 under the control of its cognate promoter, detected by immunoblotting of SDS-polyacrylamide gels with anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma) and anti-mouse secondary antibody (LI-COR) per the manufacturers' protocols. The immunoblots were imaged using a LI-COR Odyssey infrared imaging system. Samples were obtained at 24 h postinfection at an MOI of 3. Molecular mass markers (M) are shown, as are the predicted (Pred.) masses of FL (53 kDa) and CtDel (50 kDa) TAP-tagged fpv014.

Antibodies for fpv014 are still unavailable, but a TAP-tagged version of the gene for fpv014 was inserted back into the native locus under the control of the cognate promoter, and its expression was demonstrated by Western blotting of lysates with anti-FLAG antibodies (Fig. 6B).

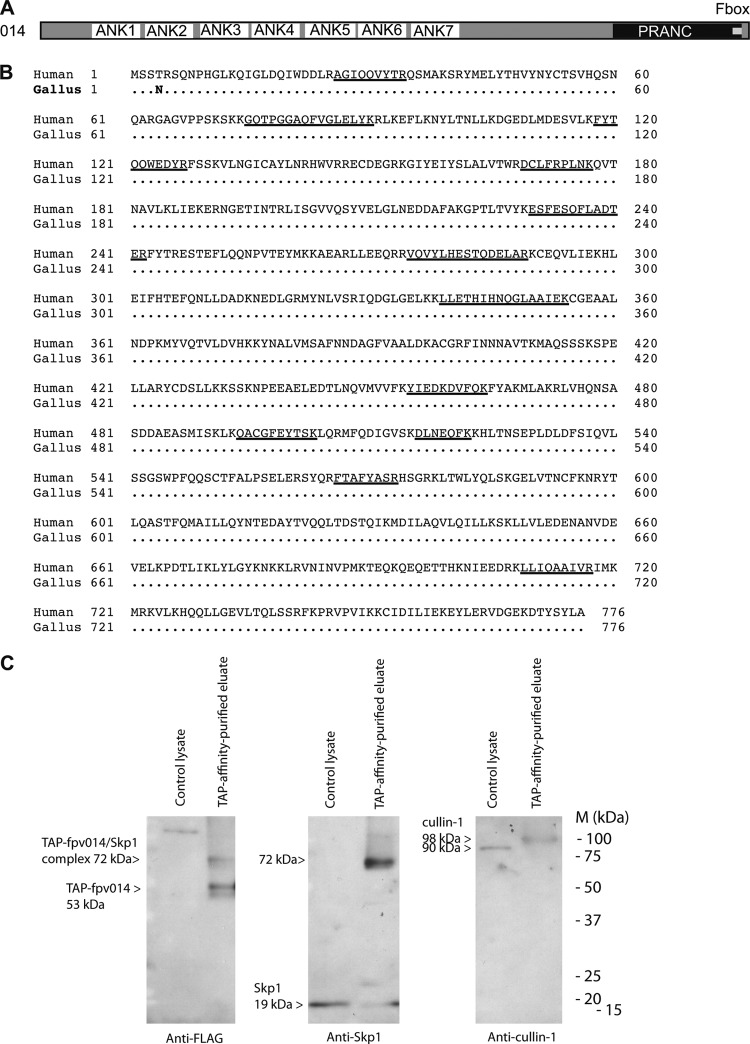

Characterization of an fpv014-knockout mutant of FWPV.

In an accompanying paper (27), a library of single-gene-knockout FWPVs was screened to identify genes involved in blocking the induction of chicken IFN-β (ChIFN2 [31]). Another gene in the FIR1 locus, fpv012, was shown to contribute toward blocking the induction of ChIFN2 mediated by transfection of the dsRNA analog poly(I·C). Conversely, even though fpv014 contributed to the enhanced resistance to the established antiviral state observed for chimeric MVA-f3La carrying the FIR1 locus, it did not contribute toward blocking the transfected poly(I·C)-mediated induction of ChIFN2 in immortalized chicken fibroblast cell line DF-1 cells (Fig. 7A), nor did fpv014, unlike fpv012, inhibit the transfected poly(I·C)-mediated induction of ChIFN2 when expressed ectopically from a eukaryotic promoter (data not shown). As fpv014 conferred enhanced resistance to MVA chimeras, then its loss from FWPV FP9 should result in decreased resistance of the knockout virus. The IC50 of ChIFN1 for the fpv014-knockout virus was therefore derived in comparison with that for parental strain FP9 (Fig. 7B) using ChIFN1 that did not cause the cytotoxicity seen in the preliminary study (Fig. 1A), so that the IC50 did not have to be calculated by extrapolation. At 2,008 U ml−1, the IC50 for the fpv014-knockout virus proved to be significantly different from that for parental FP9 (5,564 U ml−1).

Fig 7.

Characterization of an fpv014-knockout mutant of FWPV. (A) Like parental FWPV FP9, but unlike one defective in fpv012 (Del012), an FP9 mutant defective in fpv014 (Del014) retains the full ability to block poly(I·C)-mediated induction of the ChIFN2 promoter. Chicken DF1 cells were transfected with the ChIFN2 promoter reporter (pChIFN2lucter) and the constitutive lacZ reporter plasmid pJATlacZ. Following recovery for 24 h, cells were either left uninfected or infected with parental FWPV FP9 or single-gene mutants of FP9 at an MOI of 10. Following infection for 4 h, cells were either left untreated or transfected with poly(I·C) (10 μg ml−1) and incubated for 16 h. Luciferase assays were carried out, and data were normalized using β-galactosidase measurements. The result for each sample was compared to that for the uninfected, poly(I·C)-treated control to calculate percent induction. Results show the mean (n = 3) + SD. (B) Plaque reduction assays were performed on parental and fpv014-knockout (Del014) FWPV FP9 over a range of ChIFN1 concentrations from 1 to 10,000 U ml−1. IC50 values for ChIFN1 with each of the viruses were derived in Prism software (Graphpad) using nonlinear fits of the log-converted ChIFN1 concentrations against the percentage of normalized plaque responses. IC50 values are plotted with 95% confidence intervals.

IFN modulator fpv014 is a member of the ANK/PRANC poxvirus gene family.

The inhibitor of IFN responses identified by this study, fpv014, is encoded by a member of the largest poxvirus gene family. These proteins have an N-terminal domain (InterPro IPR020683) containing multiple copies (7 in the case of fpv014) of the ankyrin repeat (ANK; InterPro IPR002110). Most of them, including fpv014 (Fig. 8A), have been described by Mercer and colleagues (40) as ANK/PRANC proteins, with multiple ANKs and a C-terminal F-box-like motif in a PRANC (pox protein repeats of ankyrin—C-terminal; InterPro IPR018272) domain.

Fig 8.

fpv014 is an ANK/PRANC protein that associates with Skp1 and cullin-1. (A) Domain structure of fpv014 showing N-terminal ankyrin repeats (ANKs) as well as the C-terminal F-box motif and the larger, encompassing PRANC domain. The structure is to scale. (B) Chicken cullin-1 amino acid sequence (GenBank accession number XP_418878) aligned (dots indicate identical residues) with that of human cullin-1 (GenBank accession number NP_003583), showing peptides (underlined) identified by mass spectrometric sequence analysis of proteins copurified with TAP-tagged fpv014. (C) Immunoblot detection of Skp1 and cullin-1 co-affinity purified with TAP-tagged fpv014. DF1 control cell lysate (Control lysate) or the final eluate of TAP affinity-purified lysate from a DF-1 cell line inducibly expressing TAP-tagged fpv014 (TAP-affinity-purified eluate) were subject to nonreducing 15% SDS-PAGE and then immunoblotted using mouse anti-FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich), mouse anti-Skp1, or mouse anti-cullin-1 (BD Transduction Laboratories) at 1 in 1,000, followed by goat anti-mouse IgG (Sigma) at 1 in 25,000. Molecular mass markers (M) are shown, as are the predicted masses of TAP-tagged fpv014 (53 kDa), ChSkp1 (19 kDa), and chicken cullin-1 (90 kDa).

fpv014 interacts with proteins of the SCF complex.

To identify ligands for fpv014, its gene was cloned into a C-terminal TAP-tagging vector placing its expression under the control of the tetracycline operator element. Stable transformants containing the TAP-tagged constructs were established in a derivative (S. M. Laidlaw, unpublished data) of the immortalized DF-1 chicken fibroblast cell line expressing a tetracycline-dependent transactivator. Tandem affinity purification was then conducted on lysates from noninduced and doxycycline-induced cells. Tandem mass spectrometry of coprecipitated bands purified by SDS-PAGE demonstrated that fpv014 is complexed with chicken cullin-1 (Fig. 8B). In this regard, fpv014 behaves like several other members of the ANK/PRANC family from poxviruses that infect mammals, namely, cowpox virus, ectromelia virus, myxoma virus, Orf virus, and vaccinia MVA (41–46), indicating that fpv014 also functions via the SCF (Skp1, cullin-1, F-box) ubiquitin ligase complex. The PRANC proteins interact indirectly with cullin-1 via Skp1 as an adaptor. Skp1 was not identified in any of the bands excised for mass spectrometry, so the affinity-purified TAP-tagged fpv014 eluate and fpv014-nonexpressing control cell lysate were analyzed by Western blotting. Nonreducing conditions were used for SDS-PAGE, as the samples had been prepared for compatibility with subsequent mass spectrometry. Under these nonreducing conditions, TAP-tagged fpv014, detected in the purified eluates from expressing cell lines (but not in control lysates) by antibody recognizing the FLAG epitope in the TAP tag, migrated as two pairs of bands (with the upper band of each pair being predominant; Fig. 8C). The lower pair migrated just above the 50-kDa marker, consistent with the expected size (53 kDa) of TAP-tagged fpv014. The upper pair migrated just below the 75-kDa marker, consistent with a 72-kDa complex between TAP-tagged fpv014 and Skp1 (19 kDa). Immunoblotting detected Skp1 in the control lysates at the expected size of 19 kDa (Fig. 8C). In the purified eluates from TAP-fpv014-expressing cells, some Skp1 was evident at 19 kDa, but most of it comigrated (at 72 kDa) with the slower-migrating pair of TAP-tagged fpv014 bands (Fig. 8C). Immunoblotting also detected cullin-1 in the control lysates at the expected size of 90 kDa (Fig. 8C). The cullin-1 in the purified eluates from TAP-fpv014-expressing cells, however, migrated slightly slower than in the control lysates (consistent with the 98-kDa ubiquitinated form of cullin-1 observed to interact with the myxoma virus PRANC protein MNF [41]). Even though this cullin-1 copurified with TAP-tagged fpv014 in the eluate, it was not observed in a complex with TAP-tagged fpv014 (predicted mass, 143 kDa or 162 kDa with the addition of Skp1) on the immunoblot, whether due to SDS sensitivity of the complex or to the inability of the antibody to bind complexed cullin-1. We have been unable to source an antibody for another member of the complex, RBX/Roc1, that functions appropriately with chicken cell extracts.

DISCUSSION

Vaccinia virus (VACV), the type species of the orthopoxviruses and the most extensively studied poxvirus, has been shown to encode a considerable number of proteins that, though nonessential for replication in vitro, contribute to virulence and/or the ability of the virus to replicate in vivo. Such proteins generally modulate the innate immune system of the host and are generically known as immunomodulators. Initially, many of these proteins were identified by their sequence similarity with host immune effectors, probably derived by lateral gene transfer. Examples include soluble binding proteins for IFNs and interleukins (6, 7, 47, 48). Similar proteins are encoded by members of other genera of mammalian poxviruses (49, 50). Later, such proteins were identified by functional or ligand-binding studies (51, 52), and more recently, they have been identified by structural (but not primary sequence) similarity to host effectors (14, 16).

Such approaches have not proved particularly successful for identifying immunomodulators encoded by avipoxviruses (10, 12, 23). Despite the apparent absence from FWPV of IFN modulators equivalent to those found in VACV and of other candidate IFN modulators readily identified by their sequence homology with known host components or targets of the IFN system, our data show that FWPV effectively subverts the antiviral effects of avian IFN, even in an established antiviral state. Indeed, FWPV can even rescue coinfecting IFN-sensitive viruses such as SFV (unpublished data), indicating that at least some of the mechanisms can operate in trans.

A two-stage genetic screening strategy was employed in an attempt to identify FWPV genes involved in resisting the antiviral effectors of the type I IFN system. The first-stage screen identified a locus comprising just 3 genes (fpv012, fpv013, and fpv014), and the second stage identified fpv014. The first-stage chimera, MVA-f3La, carrying 3 genes, appeared to be more resistant than the one carrying the only gene that contributed to ChIFN1 resistance (fpv014), but qRT-PCR analysis later revealed that fpv014 expression levels were lower in the single-gene chimera than in the 3-gene chimera, suggesting that the levels of fpv14 expression account for the difference in the levels of resistance observed. It is notable that the fold change in IC50s of the MVA chimeras upon introduction of fpv014 is comparable in scale (but opposite in direction) to the fold change in the IC50 of FWPV FP9 upon deletion of fpv014, reinforcing the view that the MVA screen offers a valid representation of the role of FWPV IFN modulators in their normal context.

Both fpv014 and fpv012 are members of an extensive gene family encoding ANK proteins, which are found throughout the evolutionary tree in more than 40,000 proteins from viruses and bacteria to higher plants and animals. They mediate protein-protein interactions and so are found in proteins with all manner of functions, roles, and localization (53). With the curious exception of MOCV, all mammalian poxviruses encode ANK proteins, with the actual number varying from 4 to 31 members (54, 55), but the higher numbers often represent partial pseudogenes and the actual number of orthologous groups in mammalian poxviruses is estimated as being from 5 in parapoxviruses to 15 in orthopoxviruses (55). The family appears to have expanded considerably in the avipoxviruses, with 31 members in a pathogenic FWPV isolate (10) and 51 in a pathogenic 1948 isolate of CNPV (11). The number of orthologous groups cannot yet be estimated for the avipoxviruses, because so far, only the genome sequences of FWPV and CNPV have been published, but the known ANK genes represent 11% and 15% of the total gene complement of these viruses, respectively. About 70% of them have F boxes, suggesting that they are likely to be intact, in contrast to only 36% in the only mammalian poxvirus that encodes more than 20 ANKs, horsepox virus (55, 56). Extensive passage (more than 430 times) of pathogenic FWPV HP-1 through CEF culture by Mayr and Malicki with concomitant attenuation (57) led to the loss or disruption of 12 FWPV ANK genes in FP9, but the only change to fpv014 resulted in a conservative Asp-to-Glu substitution at residue 225 of fpv014 (12). Given the high level of resistance of FP9 to ChIFN1, we have no reason to expect that fpv014 of HP-1 should be any more effective than that of FP9. Apart from FWPV, the only other member of the Avipoxvirus genus for which the genome sequence has been published is CNPV, which is considerably diverged from FWPV, displays significant differences in gene complement (10, 11), and is found in a different major clade of the genus (58). Comparisons between ANK proteins can be problematic, but Sonnberg et al. (55) reported the most likely CNPV ortholog of fpv014 to be cnpv019 (48% amino acid identity). These orthologs are not in syntenic positions, and we have not yet assessed whether cnpv019 can contribute to enhanced ChIFN1 resistance in the MVA model.

The combination of N-terminal ANK and C-terminal F-box/PRANC domains found in fpv014 is essentially restricted to poxviruses, though ANK/PRANC genes have now been found in Nasonia parasitic wasps and were apparently transferred to them horizontally via endosymbiotic Wolbachia rickettsial bacteria (59). The PRANC domains of a number of mammalian poxvirus ANK proteins have been shown to mediate interaction with core components of the ubiquitin ligase complex (41, 42, 45, 46, 60). It was postulated (40, 43) that such interactions would target for ubiquitination ligands captured by the N-terminal ANK domains. However, the identities of cellular ligands captured by the ANK domain have been established for only an extremely small minority of poxvirus ANK proteins (61). Thus, Akt appears to be the target for myxoma virus MT-5 (62), while NF-κB is bound by variola virus G1R (63) and its cowpox virus (CPXV) ortholog CPXV006 (64), as well as by CPXV CP77/CPXV025 (42).

Despite considerable effort, we have been unable to identify a cellular ligand for the N-terminal ANK domain of fpv014. Although it was not our main goal, we were able to demonstrate tandem affinity copurification of chicken cullin-1 (by mass spectrometry and immunoblotting) and chicken Skp1 (by immunoblotting only) with TAP-tagged fpv014. This indicated that fpv014 interacts with the avian ubiquitin ligase complex (presumably via the F box) in the same way that PRANC proteins of mammalian poxviruses have been shown to interact with the mammalian complexes. The immunoblotting was performed after nonreducing SDS-PAGE not to look for complexes but so that the samples would be suitable for subsequent mass spectrometry. The observation that most of the copurified Skp1 comigrated with a substantial proportion of the TAP-tagged fpv014 was, therefore, somewhat serendipitous. However, it suggests that fpv014 and chicken Skp1 can form an SDS-stable complex. Unfortunately, we were not able to further investigate whether the complex was reductant sensitive. We are not aware of reports of similar F-box protein–Skp1 gel complexes (though such complexes have been observed elsewhere [65, 66]), nor is it apparent to us that others in the field have looked directly for such a complex or have been in a position to observe it. The cullin-1 that copurified with TAP-tagged fpv014, however, does not appear to form a comigrating complex with it on the immunoblot. Because the interaction of cullin-1 with F-box proteins is indirect, via Skp1, it is perhaps not surprising that an fpv014–cullin-1 complex should be less stable than an fpv014-Skp1 complex. Although the cullin-1 that copurified with TAP-tagged fpv014 did not form a complex with the fpv014 on the immunoblot, it migrated more slowly than the cullin-1 in the control lysate. There is a precedent for this observation, in that two similarly sized bands copurified with green fluorescent-tagged myxoma virus MNF protein. The predominant slower form immunoblotted with an unspecified antiubiquitin antibody (41). There is no indication at this stage whether fpv014 stabilized the modified form of cullin-1 in the cell or whether it was solely (or predominantly) the modified form that copurified with TAP-tagged fpv014. We have not been able to investigate whether the cullin-1 that copurified with TAP-tagged fpv014 was ubiquitinated, but we are aware that the size difference observed between it and the cullin-1 from control lysates could equally correspond to the well-reported addition of the ubiquitin-like NEDD8 adduct rather than ubiquitin itself (67–69).

Data shown here (Fig. 7 and unpublished data) demonstrate that fpv014 does not inhibit transfected poly(I·C)-mediated induction of the ChIFN2 promoter. There are currently no clues as to the cellular target(s) of fpv014, and gaps in our understanding of the chicken type I IFN system render its identification even more complicated. Although the chicken system is largely equivalent to that of mammals, the as yet incomplete (and incompletely annotated) chicken genome sequence revealed significant differences between the mammalian and chicken systems. The absence of the RIG-I gene from the chicken but not from all avian species (70) and the retention of mda-5 (71, 72) have already been reported, and their possible implications have been considered. Other key components remain unaccounted for. For instance, two major transcription factors implicated in type I IFN mRNA expression in mammals are constitutively expressed IRF-3 and IFN-inducible IRF-7 (73), but the gene encoding only one of them (chicken IRF-3 [GenBank accession number NP_990703]) is found in the chicken, although it is actually most closely related to mammalian IRF-7. Genes encoding IRF-9 and STAT-2 have also not yet been identified in the chicken (S. Goodbourn and C. Ross, unpublished data). The biological consequences of these differences remain unclear, but they, combined with a relative dearth of reagents for the chicken system, are likely to complicate elucidation of the mode of action of the FWPV IFN modulators, as well as understanding of the interaction of avian innate systems with avian pathogens, not least with important zoonotic agents such as avian influenza virus H5N1 and West Nile virus. However, this new avian virus IFN modulator, together with another (fpv012, which blocks dsRNA-mediated induction of the ChIFN2 promoter) reported in the accompanying paper (27), will provide useful reagents for probing the specific nature of the avian innate defenses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Peter Staeheli (University of Freiburg) for initial provision of recombinant avian type I IFN, John Fazakerley (University of Edinburgh) for supplying SFV A7 (27), Sarah Gilbert (University of Oxford) for MVA-LZ, and Paul Britton (Institute for Animal Health) for VACV VTN. We also acknowledge Geoffrey Smith (University of Cambridge) for pUC13TAP.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) with funding to M.A.S. (grants BBS/B/00115/2, BB/E009956/1, and BB/G018545/1) and S.G. (grants BBS/B/00344 and BB/G018332/1).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 20 February 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Randall RE, Goodbourn S. 2008. Interferons and viruses: an interplay between induction, signalling, antiviral responses and virus countermeasures. J. Gen. Virol. 89:1–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roy CR, Mocarski ES. 2007. Pathogen subversion of cell-intrinsic innate immunity. Nat. Immunol. 8:1179–1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Perdiguero B, Esteban M. 2009. The interferon system and vaccinia virus evasion mechanisms. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 29:581–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chang HW, Watson JC, Jacobs BL. 1992. The E3L gene of vaccinia virus encodes an inhibitor of the interferon-induced, double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:4825–4829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sharp TV, Witzel JE, Jagus R. 1997. Homologous regions of the alpha subunit of eukaryotic translational initiation factor 2 (eIF2alpha) and the vaccinia virus K3L gene product interact with the same domain within the dsRNA-activated protein kinase (PKR). Eur. J. Biochem. 250:85–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Colamonici OR, Domanski P, Sweitzer SM, Larner A, Buller RM. 1995. Vaccinia virus B18R gene encodes a type I interferon-binding protein that blocks interferon alpha transmembrane signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 270:15974–15978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Symons JA, Alcami A, Smith GL. 1995. Vaccinia virus encodes a soluble type I interferon receptor of novel structure and broad species specificity. Cell 81:551–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Najarro P, Traktman P, Lewis JA. 2001. Vaccinia virus blocks gamma interferon signal transduction: viral VH1 phosphatase reverses Stat1 activation. J. Virol. 75:3185–3196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shisler JL, Jin XL. 2004. The vaccinia virus K1L gene product inhibits host NF-kappaB activation by preventing IkappaBalpha degradation. J. Virol. 78:3553–3560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Afonso CL, Tulman ER, Lu Z, Zsak L, Kutish GF, Rock DL. 2000. The genome of fowlpox virus. J. Virol. 74:3815–3831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tulman ER, Afonso CL, Lu Z, Zsak L, Kutish GF, Rock DL. 2004. The genome of canarypox virus. J. Virol. 78:353–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Laidlaw SM, Skinner MA. 2004. Comparison of the genome sequence of FP9, an attenuated, tissue culture-adapted European strain of fowlpox virus, with those of virulent American and European viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 85:305–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Senkevich TG, Koonin EV, Bugert JJ, Darai G, Moss B. 1997. The genome of molluscum contagiosum virus: analysis and comparison with other poxviruses. Virology 233:19–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aoyagi M, Zhai D, Jin C, Aleshin AE, Stec B, Reed JC, Liddington RC. 2007. Vaccinia virus N1L protein resembles a B cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) family protein. Protein Sci. 16:118–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Benfield CT, Mansur D, McCoy LE, Ferguson BJ, Bahar M, Oldring AP, Grimes JM, Stuart DI, Graham SC, Smith GL. 2011. Mapping the i{kappa}B kinase beta (ikk{beta})-binding interface of the B14 protein, a vaccinia virus inhibitor of IKK{beta}-mediated activation of nuclear factor kappaB. J. Biol. Chem. 286:20727–20735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cooray S, Bahar MW, Abrescia NG, McVey CE, Bartlett NW, Chen RA, Stuart DI, Grimes JM, Smith GL. 2007. Functional and structural studies of the vaccinia virus virulence factor N1 reveal a Bcl-2-like anti-apoptotic protein. J. Gen. Virol. 88:1656–1666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gonzalez JM, Esteban M. 2010. A poxvirus Bcl-2-like gene family involved in regulation of host immune response: sequence similarity and evolutionary history. Virol. J. 7:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Graham SC, Bahar MW, Cooray S, Chen RA, Whalen DM, Abrescia NG, Alderton D, Owens RJ, Stuart DI, Smith GL, Grimes JM. 2008. Vaccinia virus proteins A52 and B14 share a Bcl-2-like fold but have evolved to inhibit NF-kappaB rather than apoptosis. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000128 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jacobs N, Bartlett NW, Clark RH, Smith GL. 2008. Vaccinia virus lacking the Bcl-2-like protein N1 induces a stronger natural killer cell response to infection. J. Gen. Virol. 89:2877–2881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kalverda AP, Thompson GS, Vogel A, Schroder M, Bowie AG, Khan AR, Homans SW. 2009. Poxvirus K7 protein adopts a Bcl-2 fold: biochemical mapping of its interactions with human DEAD box RNA helicase DDX3. J. Mol. Biol. 385:843–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fleming SB, McCaughan CA, Andrews AE, Nash AD, Mercer AA. 1997. A homolog of interleukin-10 is encoded by the poxvirus orf virus. J. Virol. 71:4857–4861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Afonso CL, Delhon G, Tulman ER, Lu Z, Zsak A, Becerra VM, Zsak L, Kutish GF, Rock DL. 2005. Genome of deerpox virus. J. Virol. 79:966–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Puehler F, Schwarz H, Waidner B, Kalinowski J, Kaspers B, Bereswill S, Staeheli P. 2003. An interferon-gamma-binding protein of novel structure encoded by the fowlpox virus. J. Biol. Chem. 278:6905–6911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Himly M, Foster DN, Bottoli I, Iacovoni JS, Vogt PK. 1998. The DF-1 chicken fibroblast cell line: transformation induced by diverse oncogenes and cell death resulting from infection by avian leukosis viruses. Virology 248:295–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pulford DJ, Britton P. 1991. Expression and cellular localisation of porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus N and M proteins by recombinant vaccinia viruses. Virus Res. 18:203–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Potter P, Tourdot S, Blanchard T, Smith GL, Gould KG. 2001. Differential processing and presentation of the H-2D (b)-restricted epitope from two different strains of influenza virus nucleoprotein. J. Gen. Virol. 82:1069–1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Laidlaw SM, Robey R, Davies M, Giotis ES, Ross C, Buttigieg K, Goodbourn S, Skinner MA. 2013. Genetic screen of a mutant poxvirus library identifies an ankyrin repeat protein involved in blocking induction of avian type I interferon. J. Virol. 87:5041–5052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Childs K, Stock N, Ross C, Andrejeva J, Hilton L, Skinner M, Randall R, Goodbourn S. 2007. mda-5, but not RIG-I, is a common target for paramyxovirus V proteins. Virology 359:190–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Masson N, Ellis M, Goodbourn S, Lee KA. 1992. Cyclic AMP response element-binding protein and the catalytic subunit of protein kinase A are present in F9 embryonal carcinoma cells but are unable to activate the somatostatin promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:1096–1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marais R, Light Y, Paterson HF, Marshall CJ. 1995. Ras recruits Raf-1 to the plasma membrane for activation by tyrosine phosphorylation. EMBO J. 14:3136–3145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sick C, Schultz U, Munster U, Meier J, Kaspers B, Staeheli P. 1998. Promoter structures and differential responses to viral and nonviral inducers of chicken type I interferon genes. J. Biol. Chem. 273:9749–9754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pestka S, Meager A. 1997. Interferon standardization and designations. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 17(Suppl. 1):S9–S14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Falkner FG, Moss B. 1990. Transient dominant selection of recombinant vaccinia viruses. J. Virol. 64:3108–3111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gloeckner CJ, Boldt K, Schumacher A, Roepman R, Ueffing M. 2007. A novel tandem affinity purification strategy for the efficient isolation and characterisation of native protein complexes. Proteomics 7:4228–4234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Meisinger-Henschel C, Schmidt M, Lukassen S, Linke B, Krause L, Konietzny S, Goesmann A, Howley P, Chaplin P, Suter M, Hausmann J. 2007. Genomic sequence of chorioallantois vaccinia virus Ankara, the ancestor of modified vaccinia virus Ankara. J. Gen. Virol. 88:3249–3259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Meyer H, Sutter G, Mayr A. 1991. Mapping of deletions in the genome of the highly attenuated vaccinia virus MVA and their influence on virulence. J. Gen. Virol. 72(Pt 5):1031–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mayr A, Stickl H, Muller HK, Danner K, Singer H. 1978. The smallpox vaccination strain MVA: marker, genetic structure, experience gained with the parenteral vaccination and behavior in organisms with a debilitated defence mechanism (author's transl). Zentralbl. Bakteriol. B 167:375–390 (In German.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Boulanger D, Green P, Jones B, Henriquet G, Hunt LG, Laidlaw SM, Monaghan P, Skinner MA. 2002. Identification and characterization of three immunodominant structural proteins of fowlpox virus. J. Virol. 76:9844–9855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yang Z, Bruno DP, Martens CA, Porcella SF, Moss B. 2010. Simultaneous high-resolution analysis of vaccinia virus and host cell transcriptomes by deep RNA sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:11513–11518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mercer AA, Fleming SB, Ueda N. 2005. F-box-like domains are present in most poxvirus ankyrin repeat proteins. Virus Genes 31:127–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Blanie S, Gelfi J, Bertagnoli S, Camus-Bouclainville C. 2010. MNF, an ankyrin repeat protein of myxoma virus, is part of a native cellular SCF complex during viral infection. Virol. J. 7:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chang SJ, Hsiao JC, Sonnberg S, Chiang CT, Yang MH, Tzou DL, Mercer AA, Chang W. 2009. Poxvirus host range protein CP77 contains an F-box-like domain that is necessary to suppress NF-kappaB activation by tumor necrosis factor alpha but is independent of its host range function. J. Virol. 83:4140–4152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Johnston JB, Wang G, Barrett JW, Nazarian SH, Colwill K, Moran M, McFadden G. 2005. Myxoma virus M-T5 protects infected cells from the stress of cell cycle arrest through its interaction with host cell cullin-1. J. Virol. 79:10750–10763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sonnberg S, Seet BT, Pawson T, Fleming SB, Mercer AA. 2008. Poxvirus ankyrin repeat proteins are a unique class of F-box proteins that associate with cellular SCF1 ubiquitin ligase complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:10955–10960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sperling KM, Schwantes A, Schnierle BS, Sutter G. 2008. The highly conserved orthopoxvirus 68k ankyrin-like protein is part of a cellular SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. Virology 374:234–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. van Buuren N, Couturier B, Xiong Y, Barry M. 2008. Ectromelia virus encodes a novel family of F-box proteins that interact with the SCF complex. J. Virol. 82:9917–9927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Alcami A, Smith GL. 1995. Vaccinia, cowpox, and camelpox viruses encode soluble gamma interferon receptors with novel broad species specificity. J. Virol. 69:4633–4639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Alcami A, Smith GL. 1992. A soluble receptor for interleukin-1 beta encoded by vaccinia virus: a novel mechanism of virus modulation of the host response to infection. Cell 71:153–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schreiber M, McFadden G. 1994. The myxoma virus TNF-receptor homologue (T2) inhibits tumor necrosis factor-alpha in a species-specific fashion. Virology 204:692–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Upton C, Mossman K, McFadden G. 1992. Encoding of a homolog of the IFN-gamma receptor by myxoma virus. Science 258:1369–1372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lalani AS, Graham K, Mossman K, Rajarathnam K, Clark-Lewis I, Kelvin D, McFadden G. 1997. The purified myxoma virus gamma interferon receptor homolog M-T7 interacts with the heparin-binding domains of chemokines. J. Virol. 71:4356–4363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Smith CA, Smith TD, Smolak PJ, Friend D, Hagen H, Gerhart M, Park L, Pickup DJ, Torrance D, Mohler K, Schooley K, Goodwin RG. 1997. Poxvirus genomes encode a secreted, soluble protein that preferentially inhibits beta chemokine activity yet lacks sequence homology to known chemokine receptors. Virology 236:316–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bork P. 1993. Hundreds of ankyrin-like repeats in functionally diverse proteins: mobile modules that cross phyla horizontally? Proteins 17:363–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shchelkunov SN. 2010. Interaction of orthopoxviruses with the cellular ubiquitin-ligase system. Virus Genes 41:309–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sonnberg S, Fleming SB, Mercer AA. 2011. Phylogenetic analysis of the large family of poxvirus ankyrin-repeat proteins reveals orthologue groups within and across chordopoxvirus genera. J. Gen. Virol. 92:2596–2607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tulman ER, Delhon G, Afonso CL, Lu Z, Zsak L, Sandybaev NT, Kerembekova UZ, Zaitsev VL, Kutish GF, Rock DL. 2006. Genome of horsepox virus. J. Virol. 80:9244–9258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mayr A, Malicki K. 1966. Attenuierung von virulentem Hühnerpockenvirus in Zellkulturen und Eigenschaften des attenuierten Virus. Zentralbl. Veterinärmed. B 13:1–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jarmin S, Manvell R, Gough RE, Laidlaw SM, Skinner MA. 2006. Avipoxvirus phylogenetics: identification of a PCR length polymorphism that discriminates between the two major clades. J. Gen. Virol. 87:2191–2201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Werren JH, Richards S, Desjardins CA, Niehuis O, Gadau J, Colbourne JK, Beukeboom LW, Desplan C, Elsik CG, Grimmelikhuijzen CJ, Kitts P, Lynch JA, Murphy T, Oliveira DC, Smith CD, van de Zande L, Worley KC, Zdobnov EM, Aerts M, Albert S, Anaya VH, Anzola JM, Barchuk AR, Behura SK, Bera AN, Berenbaum MR, Bertossa RC, Bitondi MM, Bordenstein SR, Bork P, Bornberg-Bauer E, Brunain M, Cazzamali G, Chaboub L, Chacko J, Chavez D, Childers CP, Choi JH, Clark ME, Claudianos C, Clinton RA, Cree AG, Cristino AS, Dang PM, Darby AC, de Graaf DC, Devreese B, Dinh HH, Edwards R, Elango N, et al. 2010. Functional and evolutionary insights from the genomes of three parasitoid Nasonia species. Science 327:343–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Werden SJ, Lanchbury J, Shattuck D, Neff C, Dufford M, McFadden G. 2009. The myxoma virus m-t5 ankyrin repeat host range protein is a novel adaptor that coordinately links the cellular signaling pathways mediated by Akt and Skp1 in virus-infected cells. J. Virol. 83:12068–12083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Barry M, van Buuren N, Burles K, Mottet K, Wang Q, Teale A. 2010. Poxvirus exploitation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Viruses 2:2356–2380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Werden SJ, Barrett JW, Wang G, Stanford MM, McFadden G. 2007. M-T5, the ankyrin repeat, host range protein of myxoma virus, activates Akt and can be functionally replaced by cellular PIKE-A. J. Virol. 81:2340–2348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Mohamed MR, Rahman MM, Lanchbury JS, Shattuck D, Neff C, Dufford M, van Buuren N, Fagan K, Barry M, Smith S, Damon I, McFadden G. 2009. Proteomic screening of variola virus reveals a unique NF-kappaB inhibitor that is highly conserved among pathogenic orthopoxviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:9045–9050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mohamed MR, Rahman MM, Rice A, Moyer RW, Werden SJ, McFadden G. 2009. Cowpox virus expresses a novel ankyrin repeat NF-kappaB inhibitor that controls inflammatory cell influx into virus-infected tissues and is critical for virus pathogenesis. J. Virol. 83:9223–9236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lampl N, Budai-Hadrian O, Davydov O, Joss TV, Harrop SJ, Curmi PM, Roberts TH, Fluhr R. 2010. Arabidopsis AtSerpin1, crystal structure and in vivo interaction with its target protease RESPONSIVE TO DESICCATION-21 (RD21). J. Biol. Chem. 285:13550–13560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zolkiewska A, Moss J. 1993. Integrin alpha 7 as substrate for a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored ADP-ribosyltransferase on the surface of skeletal muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 268:25273–25276 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bornstein G, Ganoth D, Hershko A. 2006. Regulation of neddylation and deneddylation of cullin1 in SCFSkp2 ubiquitin ligase by F-box protein and substrate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:11515–11520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Morimoto M, Nishida T, Nagayama Y, Yasuda H. 2003. Nedd8-modification of Cul1 is promoted by Roc1 as a Nedd8-E3 ligase and regulates its stability. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 301:392–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wu JT, Lin HC, Hu YC, Chien CT. 2005. Neddylation and deneddylation regulate Cul1 and Cul3 protein accumulation. Nat. Cell Biol. 7:1014–1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Barber MR, Aldridge JR, Jr, Webster RG, Magor KE. 2010. Association of RIG-I with innate immunity of ducks to influenza. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:5913–5918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Karpala AJ, Stewart C, McKay J, Lowenthal JW, Bean AG. 2011. Characterization of chicken Mda5 activity: regulation of IFN-beta in the absence of RIG-I functionality. J. Immunol. 186:5397–5405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Liniger M, Summerfield A, Zimmer G, McCullough KC, Ruggli N. 2012. Chicken cells sense influenza A virus infection through MDA5 and CARDIF signaling involving LGP2. J. Virol. 86:705–717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Sato M, Suemori H, Hata N, Asagiri M, Ogasawara K, Nakao K, Nakaya T, Katsuki M, Noguchi S, Tanaka N, Taniguchi T. 2000. Distinct and essential roles of transcription factors IRF-3 and IRF-7 in response to viruses for IFN-alpha/beta gene induction. Immunity 13:539–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]