Abstract

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) inhibits the interferon-mediated antiviral response. Type I interferons (IFNs) induce the expression of IFN-stimulated genes by activating phosphorylation of both signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) and STAT2, which form heterotrimers (interferon-stimulated gene factor 3 [ISGF3]) with interferon regulatory factor 9 (IRF9) and translocate to the nucleus. PRRSV Nsp1β blocks the nuclear translocation of the ISGF3 complex by an unknown mechanism. In this study, we discovered that Nsp1β induced the degradation of karyopherin-α1 (KPNA1, also called importin-α5), which is known to mediate the nuclear import of ISGF3. Overexpression of Nsp1β resulted in a reduction of KPNA1 levels in a dose-dependent manner, and treatment of the cells with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 restored KPNA1 levels. Furthermore, the presence of Nsp1β induced an elevation of KPNA1 ubiquitination and a shortening of its half-life. Our analysis of Nsp1β deletion constructs showed that the N-terminal domain of Nsp1β was involved in the ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation of KPNA1. A nucleotide substitution resulting in an amino acid change from valine to isoleucine at residue 19 of Nsp1β diminished its ability to induce KPNA1 degradation and to inhibit IFN-mediated signaling. Interestingly, infection of MARC-145 cells by PRRSV strains VR-2332 and VR-2385 also resulted in KPNA1 reduction, whereas infection by an avirulent strain, Ingelvac PRRS modified live virus (MLV), did not. MLV Nsp1β had no effect on KPNA1; however, a mutant with an amino acid change at residue 19 from isoleucine to valine induced KPNA1 degradation. These results indicate that Nsp1β blocks ISGF3 nuclear translocation by inducing KPNA1 degradation and that valine-19 in Nsp1β correlates with the inhibition.

INTRODUCTION

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the family Arteriviridae (1). PRRSV is a significant issue to the swine industry across the world, and the virus-caused economic loss in the United States alone is estimated to be $560 million per year (2). The PRRSV genome is a little over 15 kb in length and includes 10 open reading frames (ORFs) (3, 4). ORFs 1a and 1b comprise 80% of the viral genome and encode nonstructural proteins, whereas ORFs 2 to 7 encode structural proteins (5, 6). PRRSV propagation in vitro is mainly conducted in the epithelium-derived monkey kidney cell line MARC-145 (7) and in porcine pulmonary alveolar macrophages (PAMs). In its natural swine host, PRRSV targets mainly PAMs during its acute infection (8).

PRRSV appears to inhibit the synthesis of type I interferons (IFNs) in infected pigs (9, 10). IFNs could not be detected in the lungs of pigs in which PRRSV actively replicated. PRRSV infection of PAMs and MARC-145 cells in vitro leads to very low alpha interferon (IFN-α) expression (9, 11). The suppression of innate immunity can be an important contributing factor to the modulation of host immune responses. PRRSV infection in pigs leads to delayed production and low titers of neutralizing antibodies (12), as well as a weak cell-mediated immune response (13).

Type I IFNs, including IFN-α and IFN-β, are critical to innate immunity against viral infections and play an important role in the stimulation of the adaptive immune response (14, 15). The activation of IFN signaling leads to the induction of antiviral responses. The signaling of type I IFNs is initiated after they bind to their receptors on the cell surface (16–18). This receptor binding activates Janus kinases (JAK), which then phosphorylate both signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) and STAT2. The phosphorylated STAT1 and STAT2 proteins form heterodimers which interact with interferon regulatory factor 9 (IRF9) and subsequently form heterotrimers, also known as interferon-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3). Translocation of ISGF3 into the nucleus, followed by binding to consensus DNA sequences, leads to the expression of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs). PRRSV inhibits the IFN-activated JAK/STAT signal transduction and expression of ISGs in both MARC-145 and PAM cells (19). The nuclear translocation of ISGF3 is blocked in the PRRSV-infected cells, while the IFN-induced phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT2 is minimally affected. PRRSV Nsp1β is able to block the nuclear translocation of ISGF3 complexes, yet the mechanism is unknown (19).

In this study, we found that PRRSV Nsp1β induced degradation of karyopherin-α1 (KPNA1), the karyopherin for ISGF3 nuclear translocation. HEK293 cells with Nsp1β expression had lower levels of KPNA1 protein. Infection of MARC-145 cells by PRRSV strains VR-2332 and VR-2385 resulted in the reduction of KPNA1 protein, while an avirulent strain, Ingelvac PRRS modified live virus (MLV), did not. The addition of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 to the cells with Nsp1β expression restored the KPNA1 protein levels. The replacement of one nucleotide near the 5′ terminus of VR-2385 Nsp1β diminished the protein's ability to reduce KPNA1 and to inhibit IFN-activated JAK/STAT signaling. Conversely, the replacement of the nucleotide at the same position near the 5′ terminus of MLV Nsp1β caused a reduction of KPNA1. This discovery provides further insight into PRRSV interference with IFN-activated signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses. MARC-145 (7) and HEK293 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). PRRSV strains VR-2385 (20), VR-2332 (21), and MLV (22) were used to inoculate MARC-145 cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. Virus titers for the median (50%) tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) were determined in MARC-145 cells as described previously (23).

For interferon stimulation, recombinant human IFN-αA/D (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added to the cultured cells at a final concentration of 1,000 U/ml (unless stated differently in Results and the figure legends). The cells were harvested at the time points indicated in Results or the figure legends for further analysis.

MG132 (Sigma), a proteosome inhibitor, was used to treat cells at 10 μM final concentration for 6 h prior to the cells being harvested for further analysis. In order to determine the half-life of KPNA1, cycloheximide (Sigma) was added to cultured cells at a final concentration of 100 μg/ml to block protein translation. The cells were harvested at the time points indicated in Results or the figure legends for Western blotting.

Plasmids.

The pEGFP-C1-STAT1 plasmid for STAT1-green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression was obtained from Addgene (24). The pCAGGS-FLAG-KPNA1, -KPNA2, -KPNA3, and -KPNA4 plasmids were provided by M. L. Shaw (The Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY). The pCDNA3-Ubiquitin-Myc plasmid was provided by X. Zhu (The University of Maryland, College Park, MD). The cDNA sequences of Nsp1β were amplified from cDNA of strains VR-2385, VR-2332, and MLV with primers 85nsp1F2 and 85nsp1R2 (19) and were cloned separately into the pCAGEN-HA vector. Fragments of deletion constructs of VR-2385 Nsp1β were amplified with primers 85nsp1F2 and 85nsp1bR3 for fragment D1, 85nsp1F2 and 85nsp1bR4 for D2, 85nsp1bF3 and 85nsp1R2 for D3, and 85nsp1bF4 and 85nsp1R2 for D4 (Table 1). These were then cloned into the pCAGEN-FLAG vector. The mutation of G to A at nucleotide 55 in VR-2385 Nsp1β was done by sequential PCR. The first-round PCR was done with primers 85nsp1F2 and 2385nt55R (Table 1) for fragment 1 and with 2385nt55F and 85nsp1R2 for fragment 2. The second-round PCR was done with primers 85nsp1F2 and 85nsp1R2 for overlapping PCR on both fragment 1 and 2. The product of the overlapping PCR was cloned into the pCAGEN-HA vector. A mutation of A to G at nucleotide 55 of MLV Nsp1β was also performed, in which the primer 2385nt55R was replaced with 2332nsp1R and primer 2385nt55F with 2332nsp1R. The resulting recombinant plasmids were confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion and DNA sequencing.

Table 1.

List of primers used in this study

| Primera | Sequence (5′ to 3′)b |

|---|---|

| 85nsp1bR3 | GCCTCGAGTCAACTCTCCTTAACGGAGAAG |

| 85nsp1bR4 | GCCTCGAGTCAAAACAAGCTCCACCAGCAG |

| 85nsp1bF3 | GCGAATTCGACATGTCTAAGTTCGCC |

| 85nsp1bF4 | GCGAATTCAACTTGCTCCCACTGGAAG |

| 2385nt55F | GCCGAGGGGAAAATCTCCTGGGCC |

| 2385nt55R | GGCCCAGGAGATTTTCCCCTCGGC |

| KPNA1F1 | TTGACCTTAACCAGCAGCAG |

| KPNA1R2 | TCCACAAGAGGACTCGACTG |

| 2332nt55F | GCCGAAAGGAAAGTCTCCTGGGCC |

| 2332nt55R | GGCCCAGGAGACTTTCCTTTCGGC |

F, forward primer; R, reverse primer. “85” before a primer name indicates that the primer is based on sequences of PRRSV strain VR-2385.

Italicized letters indicate restriction enzyme cleavage sites for XhoI or EcoRI for directional cloning.

Western blot analysis.

Protein samples were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and analyzed by Western blotting as described previously (25, 26). The separated proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with antibodies against phosphorylated STAT1 at tyrosine-701 (pSTAT1) (Millipore, Billerica, MA), KPNA1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), ubiquitin (Santa Cruz), hemagglutinin (HA; Rockland Immunochemicals, Inc., Gilbertsville, PA), FLAG (Sigma), STAT2 (Santa Cruz), and β-tubulin (Sigma). The antibodies bound on the membrane were detected using secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Rockland) and were revealed using a chemiluminescence substrate. The chemiluminescence signal was recorded digitally by using a ChemiDoc XRS imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Digital signal acquisition and analysis were conducted using the Quantity One program, version 4.6 (Bio-Rad).

IP.

Immunoprecipitation (IP) was conducted as previously described (19, 27), with some modifications. HEK293 cells were lysed with a lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 0.5% Igepal CA-630, 10% glycerol, 1 mM sodium vanadate) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and incubated with FLAG antibody (Sigma), followed by incubation with protein G-agarose (KPL, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). The final pellet from IP was subjected to elusion with Laemmli sample buffer or 100 mM glycine solution, pH 3.0. The IP samples were subjected to Western blotting with antibodies against pSTAT1, ubiquitin, FLAG, and HA. IP with HA antibody and then Western blotting with FLAG antibody were also conducted. To detect ubiquitinated KPNA1, ubiquitin aldehyde (Boston Biochem, Inc., Cambridge, MA), a specific inhibitor of ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases, was included in the lysis buffer at a final concentration of 2.53 μM.

RNA isolation and real-time PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from HEK293 and MARC-145 cells with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription and real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) were conducted as previously described (28, 29). The real-time PCR primers for KPNA1 are KPNA1F1 and KPNA1R1 (Table 1). Primers for ISG15 and ISG56 were reported previously (19). Transcripts of ribosomal protein L32 (RPL32) were also amplified and used to normalize the total input RNA. The transcript levels were quantified by the 2−ΔΔCT threshold cycle method (30) and are shown as fold changes relative to the levels of the mock-treated control.

IFA and confocal fluorescence microscopy.

Cells were seeded onto coverslips, incubated overnight, and transfected. Immunofluorescence assay (IFA) with monoclonal antibodies against HA or FLAG was done as described previously (31). The coverslips were mounted onto slides using Fluoromount-G clear mounting medium containing 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL). Confocal fluorescence microscopy was done as described previously (32).

Statistical analysis.

Differences in indicators between treatment groups, such as cellular RNA levels for infection by different virus strains, were assessed using the Student t test. A two-tailed P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

PRRSV Nsp1β reduces STAT1/KPNA1 complex after interferon stimulation.

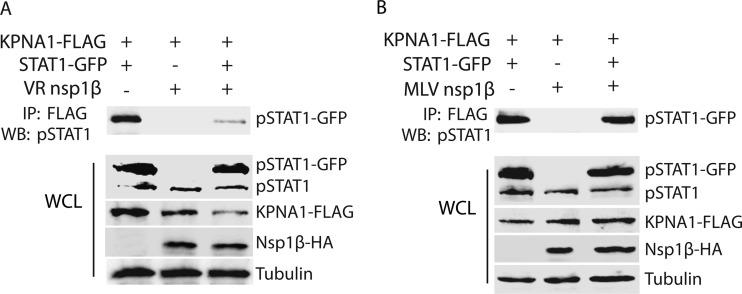

The Nsp1β of PRRSV VR-2385 was shown to block the IFN-activated nuclear translocation of ISGF3 (19). Here, the mechanism of inhibition was further examined. STAT1 nuclear translocation mainly involves KPNA1, which functions as an adaptor protein to bind karyopherin-β in transferring proteins from the cytoplasm into the nucleus. Initially, we tested whether the interaction of STAT1 and KPNA1 was affected in cells with Nsp1β expression. HEK293 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding VR-2385 Nsp1β-HA, KPNA1-FLAG, and STAT1-GFP. IFN-α was added to the cells to activate the JAK/STAT signaling pathway 48 h after the transfection. The cells were then harvested for immunoprecipitation with FLAG antibody. Next, Western blotting was conducted with antibodies against tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT1 (pSTAT1). The blotting results revealed that there was significantly less pSTAT1/KPNA1 complex in cells with Nsp1β expression than in cells with empty vector (Fig. 1A). Western blotting of whole-cell lysates showed similar levels of pSTAT1 in the cells with or without Nsp1β expression, whereas the KPNA1 levels in cells with Nsp1β were lower than the KPNA1 levels in control cells (Fig. 1A).

Fig 1.

PRRSV strain VR-2385 Nsp1β reduces the complexes of phosphorylated STAT1 interacting with karyopherin-α1 (KPNA1). HEK293 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing KPNA1-FLAG, STAT1-GFP, and Nsp1β-HA. At 48 h posttransfection, the cells were treated with IFN-α for 1.25 h before being lysed for further analysis. (A) VR-2385 Nsp1β reduces complexes of phosphorylated STAT1 and KPNA1. Immunoprecipitation (IP) was done with FLAG antibody, and Western blotting was performed with antibody against phosphorylated STAT1 at tyrosine-701 (pSTAT1). (Bottom) Western blotting results for whole-cell lysate (WCL) using antibodies against pSTAT1, FLAG, HA, and tubulin. (B) Ingelvac PRRS modified live virus (MLV) Nsp1β has minimal effect on the interaction of pSTAT1 and KPNA1. IP was done with FLAG antibody, and Western blotting was conducted with antibody against pSTAT1. (Bottom) Western blotting results for WCL of HEK293 cells with MLV Nsp1β expression using antibodies against pSTAT1, FLAG, HA, and tubulin.

MLV Nsp1β did not appear to block IFN-activated STAT1/STAT2 nuclear translocation (19) and was included as a control to test whether it would have any effect on the interaction between STAT1 and KPNA1. IP and Western blotting showed that the pSTAT1 levels in cells with MLV Nsp1β were similar to the pSTAT1 levels in control cells (Fig. 1B). Western blotting of whole-cell lysates showed that the cells with MLV Nsp1β had levels of pSTAT1 and KPNA1 that were similar to the levels in control cells. These results indicate that VR-2385 Nsp1β reduced pSTAT1/KPNA1 complexes in cells after IFN stimulation, whereas MLV Nsp1β did not.

VR-2385 Nsp1β reduces KPNA1, and the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is involved in KPNA1 reduction.

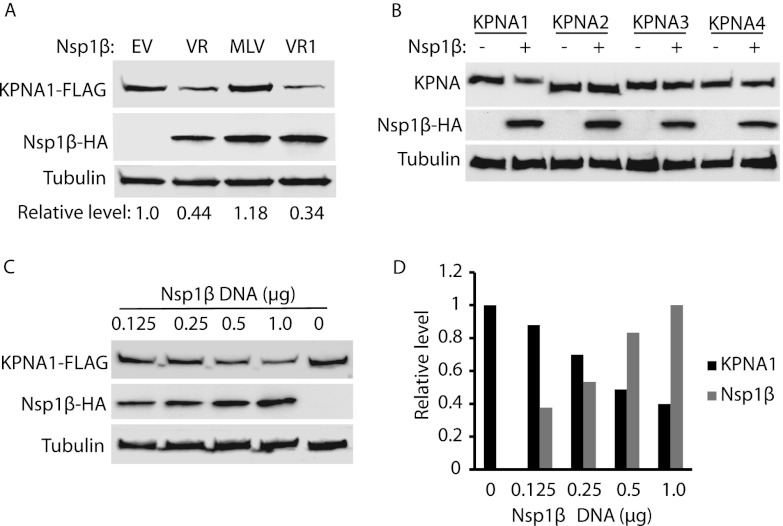

We noticed that cells with VR-2385 Nsp1β expression had lower KPNA1 levels (Fig. 1A, WCL). To confirm this, we tested whether Nsp1β caused a reduction in KPNA1. HEK293 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing Nsp1β of VR-2385, VR-2332, and MLV. Western blotting showed that the KPNA1 levels in cells with Nsp1β of VR-2385 or VR-2332 were reduced but that KPNA1 levels in cells with MLV Nsp1β changed minimally in comparison to the levels in cells with empty vector (Fig. 2A). The relative KPNA1 levels were 0.44-, 1.18-, and 0.34-fold for cells with Nsp1βs of VR-2385, MLV, and VR-2332, respectively. VR-2385 Nsp1β was also tested to determine its effect on other KPNAs to exclude the possibility of a nonspecific effect on KPNA1. HEK293 cells were cotransfected with Nsp1β and a plasmid expressing KPNA1, KPNA2, KPNA3, or KPNA4. Compared to the results for cells with the empty-vector control, Nsp1β reduced KPNA1 considerably but had minimal effects on the other three KPNAs (Fig. 2B). The results confirmed that Nsp1β specifically reduced KPNA1 levels.

Fig 2.

Nsp1β reduces KPNA1 expression. (A) KPNA1 levels are reduced in HEK293 cells with expression of Nsp1βs of VR-2385 and VR-2332. The cells were transfected with plasmids of KPNA1-FLAG and Nsp1β-HA. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were harvested for Western blotting (WB) with antibodies against FLAG, HA, and tubulin. Fold changes of KPNA1 levels are shown below the images. EV, empty vector; VR, VR-2385; VR1, VR-2332. (B) Nsp1β has minimal effect on KPNA2, KPNA3, and KPNA4. HEK293 cells were cotransfected with VR-2385 Nsp1β-HA and KPNA1-FLAG, KPNA2-FLAG, KPNA3-FLAG, or KPNA4-FLAG plasmid. Western blotting was done with antibodies against FLAG, HA, and tubulin. (C) Dose-dependent reduction of KPNA1 by VR-2385 Nsp1β. HEK293 cells were transfected with KPNA1-FLAG and incremental amounts of Nsp1β-HA plasmid. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were harvested for Western blotting. (D) Densitometry analysis of experimental results shown in panel C to show relative KPNA1 and Nsp1β levels after normalization with tubulin. Fold changes of KPNA1 and Nsp1β levels in comparison with the results for empty vector and 1-μg Nsp1β, respectively, were calculated. The incremental amounts of Nsp1β-HA plasmid DNA are shown on the x axis.

Furthermore, when incremental amounts of VR-2385 Nsp1β plasmid DNA were used in transfections, the KPNA1 protein levels were reduced in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2C). Densitometry analysis showed that, in comparison with the results for the empty-vector control, the KPNA1 levels were reduced from 0.88- to 0.4-fold in the cells transfected with 0.125 to 1 μg of Nsp1β plasmid DNA (Fig. 2D). The Nsp1β level increased along with the incremental amount of the plasmid DNA used in the transfection. The results suggested that the Nsp1β-mediated reduction of KPNA1 was specific.

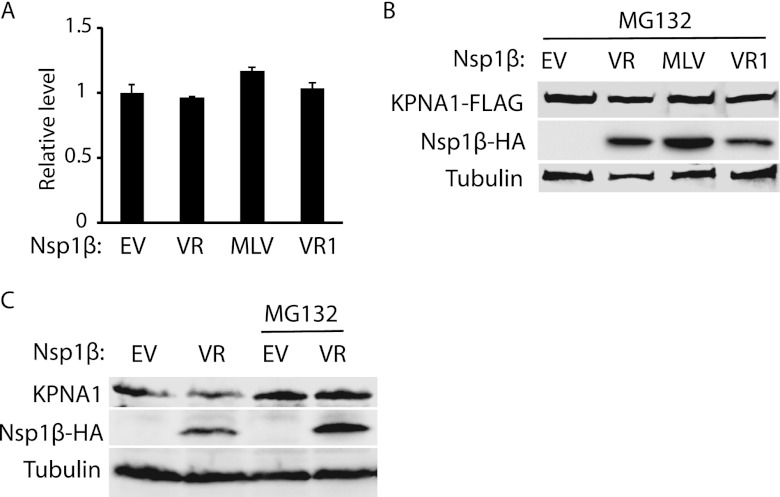

We reasoned that the KPNA1 reduction could be due to a decrease of transcription and/or translation and accelerated protein degradation. To determine the mRNA levels of KPNA1 in the cells with Nsp1β expression, we conducted RT-qPCR. The mRNA levels of endogenous KPNA1 in cells with and without Nsp1β expression were similar (Fig. 3A). The results indicated that the reduction of KPNA1 protein was not due to a change in its mRNA level. Next, we tested whether the KPNA1 reduction was due to degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasomal pathway. MG132, a proteasome inhibitor, was added to the cells 24 h after Nsp1β transfection. The cells were harvested 6 h later for Western blotting. MG132 treatment of cells with the expression of VR-2385 or VR-2332 Nsp1β resulted in the restoration of KPNA1 to levels similar to the levels in the cells with empty vector (Fig. 3B).

Fig 3.

Nsp1β reduces KPNA1 expression via the proteasome pathway. (A) KPNA1 mRNA level is not affected by Nsp1β expression. HEK293 cells were transfected with VR-2385 Nsp1β plasmid. At 24 h after transfection, the cells were harvested for RNA isolation and RT-qPCR. Error bars represent standard deviations of the results of three repeated experiments. EV, empty vector; VR, VR-2385; VR1, VR-2332. (B) The Nsp1β-induced KPNA1 reduction is inhibited by MG132 treatment. HEK293 cells were cotransfected with Nsp1β-HA and KPNA1-FLAG plasmids. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were treated with MG132 and harvested for Western blotting with antibodies against FLAG, HA, and tubulin. (C) VR-2385 Nsp1β reduces endogenous KPNA1 level, while MG132 treatment diminishes the inhibition. HEK293 cells were transfected with Nsp1β-HA plasmid. Western blotting was done with antibodies against KPNA1, HA, and tubulin.

Overexpression of KPNA1 was used in the experiments described above. Endogenous KPNA1 was also detected to exclude the possibility that overexpression of Nsp1β affected the expression of exogenous KPNA1. In the presence of Nsp1β, the endogenous KPNA1 level was considerably reduced in comparison with the level in cells treated with the empty-vector control (Fig. 3C). In addition, MG132 treatment of cells with Nsp1β expression restored KPNA1 to a level similar to that in cells with the empty-vector control (Fig. 3C). These results indicated that the KPNA1 reduction in the cells with VR-2385 Nsp1β was due to degradation by the ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal pathway.

VR-2385 Nsp1β increases KPNA1 ubiquitination and shortens its half-life.

Since MG132 treatment restored KPNA1 levels, we reasoned that the KPNA1 ubiquitination levels in the cells with Nsp1β expression would increase. HEK293 cells were transfected with KPNA1-FLAG, ubiquitin-Myc, and VR-2385 Nsp1β-HA plasmids. The cells were lysed for IP with antibody against FLAG. Western blotting with ubiquitin antibody was then performed to detect ubiquitinated KPNA1. The blotting results showed that ubiquitinated KPNA1 in the cells with Nsp1β appeared as a smear, as expected, and that its density was 4.18-fold greater than in the cells transfected with empty vector (Fig. 4A). As Laemmli sample buffer was used as the elusion buffer in IP, the heavy and light chains of immunoglobulins were disassociated and appeared as strong bands in Western blotting, which blocked the view of weaker signals. To further confirm the KPNA1 ubiquitination in the cells with Nsp1β expression, MG132 treatment was conducted to block KPNA1 degradation, and a mild elusion buffer, a glycine solution at pH 3, was used in IP to reduce the elusion of IgG molecules binding to protein G-agarose beads. Blotting with ubiquitin antibody showed stronger signals in the lane with Nsp1β than in the lane with the empty vector (Fig. 4B), indicating that there was more ubiquitinated KPNA1 in the cells with Nsp1β expression. The IgG heavy and light chains were still visible but did not obstruct the view of the other bands. In addition, whole-cell lysate was used in the blotting, which showed that the total ubiquitination levels in the cells with Nsp1β expression were similar to the levels in control cells (Fig. 4B). The results indicate that Nsp1β did not induce elevation of total ubiquitination in the cells.

Fig 4.

VR-2385 Nsp1β increases KPNA1 ubiquitination. (A) KPNA1 ubiquitination in HEK293 cells with Nsp1β expression is higher than that in cells with empty vector. The cells cotransfected with KPNA1-FLAG, VR-2385 Nsp1β-HA, and ubiquitin-Myc plasmids were lysed for IP. Western blotting with ubiquitin antibody (WB: Ub) was done after IP. Fold changes of ubiquitin levels in comparison with the results for the cells without Nsp1β after normalization with the KPNA1 level are shown below the images. (B) Nsp1β expression leads to elevation of KPNA1 ubiquitination, while ubiquitination levels of total proteins in whole-cell lysate (WCL) of HEK293 cells in the presence or absence of Nsp1β are similar. HEK293 cells were cotransfected with KPNA1-FLAG, VR-2385 Nsp1β-HA, and ubiquitin-Myc plasmids and treated with MG132. (Left) Western blotting of IP samples with antibodies against ubiquitin and FLAG. The bands of immunoglobulin G heavy chain (IgG-H) and light chain (IgG-L) from IP elusion are indicated on the left. (Right) Western blotting of WCL with antibodies against ubiquitin and tubulin. (C) KPNA1 half-life is shortened in the presence of Nsp1β expression. HEK293 cells cotransfected with KPNA1-FLAG and VR-2385 Nsp1β plasmids were treated with cycloheximide and harvested at indicated times (h). Empty vector (EV) of Nsp1β plasmid was included as a control. KPNA1, Nsp1β, and tubulin were detected by Western blotting. (D) Densitometry analysis showing fold changes of KPNA1 levels in comparison with the levels at 1 h after cycloheximide (CHX) addition, normalized with tubulin. The KPNA1 half-life in the presence of Nsp1β was shortened from approximately 21 h to 6 h. Error bars represent standard deviations of the results for repeated experiments.

As Nsp1β increased KPNA1 ubiquitination, we speculated that the half-life of KPNA1 would be shortened. HEK293 cells were transfected with KPNA1-FLAG and VR-2385 Nsp1β. The cells were treated with a translation inhibitor, cycloheximide, at a final concentration of 100 μg per ml 24 h after the transfection. The cells were then harvested at the time points specified below for Western blotting. In the presence of Nsp1β, the KPNA1 levels decreased at a higher rate than in cells with the empty vector (Fig. 4C). The KPNA1 level 6 h after the cycloheximide treatment was reduced 0.5-fold in the cells with Nsp1β expression, while it remained at 0.9-fold in cells with the empty vector (Fig. 4D). The expression of Nsp1β induced a shortening of the KPNA1 half-life from approximately 21 h to 6 h. The blotting results also showed that the Nsp1β half-life was approximately 17 h. This result is consistent with our data showing increased ubiquitination of KPNA1 in the cells with Nsp1β expression.

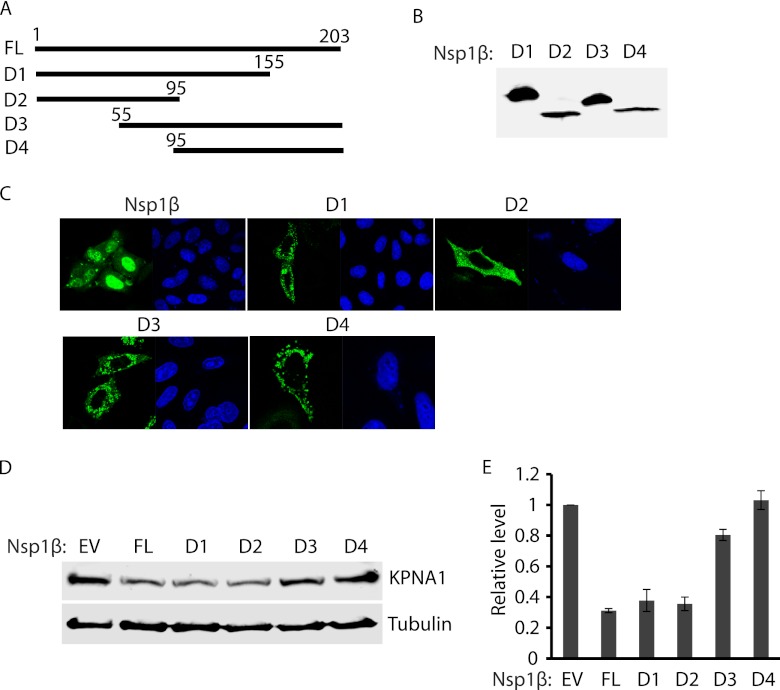

The N-terminal domain of Nsp1β appears to be responsible for the induced degradation of KPNA1.

To map the domain of Nsp1β involved in inducing the degradation of KPNA1, deletion constructs of VR-2385 Nsp1β were prepared. Four fragments of Nsp1β were cloned into the pCAGEN-FLAG vector (Fig. 5A). Overexpression of Nsp1β truncation constructs in HEK293 cells was confirmed by Western blotting with FLAG antibody (Fig. 5B). IFA was also conducted to determine the subcellular location of the truncated Nsp1βs, as full-length Nsp1β was shown to mainly distribute in the nucleus 10 h after virus infection (33). IFA showed that all four truncated Nsp1βs were distributed in the cytoplasm, while most of the full-length Nsp1β was located in the nucleus (Fig. 5C). All the truncated Nsp1βs with the exception of D2 had punctate distribution, while D2 displayed more homogenous dissemination.

Fig 5.

The N-terminal domain of Nsp1β appears to be associated with the KPNA1 degradation. (A) Schematic illustration of full-length (FL) and truncated constructs (D1 to D4) of VR-2385 Nsp1β. The names of the fragments are indicated on the left. The numbers above the lines indicate starting and ending amino acid positions of Nsp1β for the constructs. (B) Overexpression of Nsp1β deletion constructs in HEK293 cells detected by Western blotting with antibody against FLAG. (C) Immunofluorescence assay showing expression of Nsp1β deletion constructs in HeLa cells. In each panel, the left image shows the expression of Nsp1β or the deletion construct and the right image shows nuclear DNA stained with DAPI. (D) Endogenous KPNA1 levels in HEK293 cells with expression of Nsp1β deletion constructs. The cells were transfected with full-length Nsp1β and truncation constructs. Western blotting was done with antibodies against KPNA1 and tubulin. (E) Densitometry analysis showing fold changes of KPNA1 levels in comparison with the levels in cells with empty-vector control after normalization with tubulin. Error bars represent standard deviations of the results for repeated experiments.

Endogenous KPNA1 was detected in HEK293 cells with expression of the Nsp1β deletion constructs. Western blotting results showed that the cells with Nsp1β D1 (amino acids 1 to 155) and Nsp1β D2 (amino acids 1 to 95) had considerably lower KPNA1 levels than the cells transfected with empty vector (Fig. 5D). Densitometry analysis showed that the cells with Nsp1β D1 and Nsp1β D2 had KPNA1 levels at 0.31- and 0.4-fold, respectively, compared to the KPNA1 levels in cells with empty vector (Fig. 5E). The KPNA1 levels in the cells with Nsp1β D3 (amino acids 55 to 203) and Nsp1β D4 (amino acids 95 to 203) were 0.8- and 1.1-fold, respectively, in comparison to the levels in cells with the empty-vector control. Full-length Nsp1β was included as a control and, as expected, resulted in lower KPNA1 levels. The results indicate that the amino-terminal domain (amino acids 1 to 55) of Nsp1β was correlated with the degradation of KPNA1.

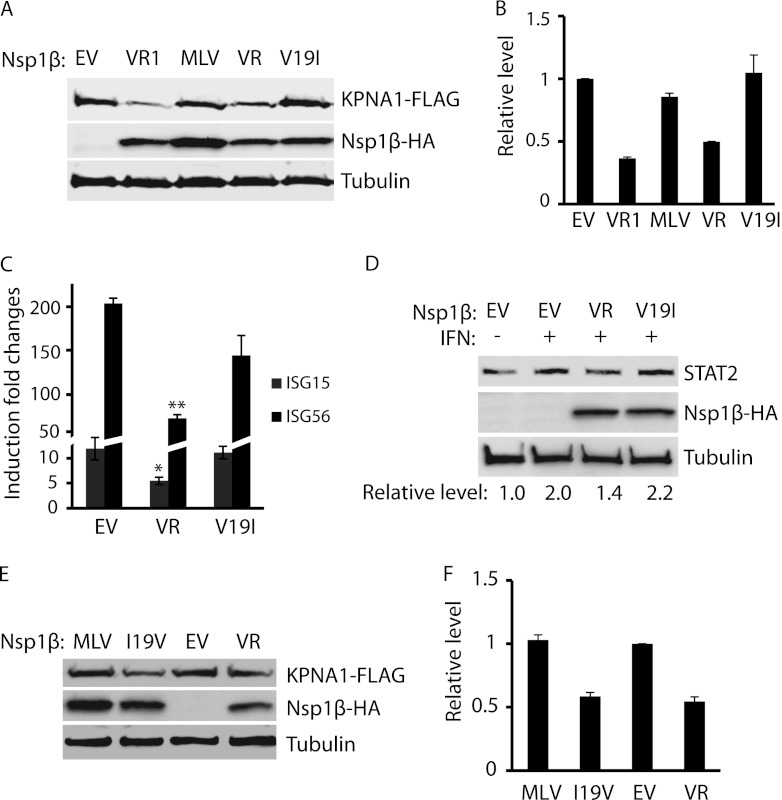

The amino acid valine at residue 19 of Nsp1β appears to be correlated with the induction of KPNA1 degradation.

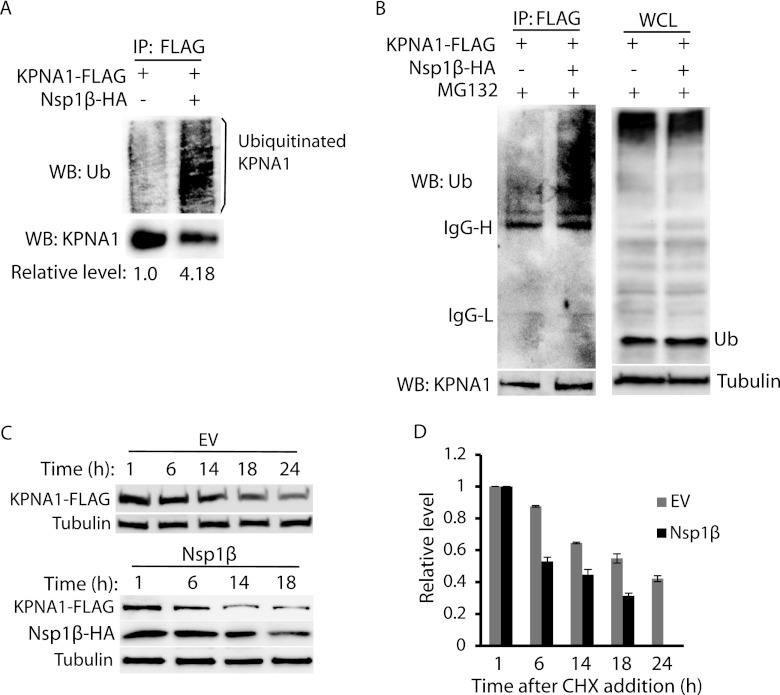

The results from the Nsp1β deletion constructs showed that the amino-terminal domain was correlated with the degradation of KPNA1. Sequence comparison indicated that two nucleotides differed between the Nsp1βs of VR-2332 and MLV, nucleotides 55 and 452. The two different nucleotides result in two different amino acids, valine at residue 19 and serine at residue 151 for VR-2332 Nsp1β and isoleucine and phenylalanine for MLV Nsp1β. VR-2385 Nsp1β has the same residues as VR-2332 at these two positions. We reasoned that valine-19 in the VR-2385 Nsp1β might correlate with the reduction of KPNA1, as it is in the N-terminal domain. Mutagenesis of the VR-2385 Nsp1β plasmid was conducted to create a point mutation at nucleotide 55 from G to A, resulting in an amino acid change from valine to isoleucine. DNA sequencing confirmed the nucleotide change from G to A in the mutant Nsp1β plasmid.

Western blotting showed that the KPNA1 levels in the cells with the mutant Nsp1β of VR-2385 were similar to those found in cells with the empty-vector control (Fig. 6A). Densitometry analysis showed that the KPNA1 levels in the cells with the Nsp1βs of VR-2332, MLV, and VR-2385 and the mutant Nsp1β of VR-2385 were 0.37-, 0.88-, 0.49-, and 1.18-fold compared to the levels in cells with the empty-vector control (Fig. 6B). The results demonstrated that the mutant Nsp1β with a substitution at nucleotide 55 had no effect on KPNA1 expression, whereas the wild-type Nsp1β reduced the KPNA1 level. This indicates that amino acid valine-19 in VR-2385 Nsp1β was correlated with KPNA1 degradation in the cells with Nsp1β expression.

Fig 6.

The presence of valine-19 in Nsp1β appears to correlate with the KPNA1 reduction. (A) The mutant VR-2385 Nsp1β with isoleucine-19 has no effect on KPNA1 levels. HEK293 cells were cotransfected with KPNA1-FLAG and Nsp1β-HA plasmids. Western blotting was conducted with antibodies against FLAG, HA, and tubulin. VR1, VR-2332; VR, VR-2385; V19I, mutant VR-2385 Nsp1β with a mutation of valine-19 to isoleucine. (B) Densitometry analysis showing fold changes of KPNA1 levels after normalization with tubulin in comparison with the levels in cells with the empty-vector control. (C) The mutant VR-2385 Nsp1β with isoleucine-19 loses inhibitory effect on IFN-induced expression of ISG15 and ISG56. HEK293 cells were transfected with wild-type (VR) or Nsp1β mutant (V19I) plasmids. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were treated with IFN-α at 300 U/ml and, 10 h later, harvested for RNA isolation and RT-qPCR. Fold changes of mRNA levels in comparison with the levels in cells without IFN-α treatment are shown. Significant differences in ISG15 and ISG56 mRNA levels between cells with wild-type Nsp1β and those with mutant or empty vector (EV) are indicated as follows: *, P < 0.05, and **, P < 0.01. Error bars represent standard deviations of the results for repeated experiments. (D) The mutant VR-2385 Nsp1β loses inhibitory effect on IFN-induced elevation of STAT2 protein. Fold changes of STAT2 levels in comparison with the levels in cells with empty-vector control are shown below the images. (E) The mutant MLV Nsp1β with valine-19 acquires inhibitory effect on KPNA1 levels. HEK293 cells were cotransfected with KPNA1-FLAG and wild-type (MLV) or mutant Nsp1β (I19V) plasmids. Empty vector and VR-2385 Nsp1β plasmid were included for control. (F) Densitometry analysis showing fold changes of KPNA1 levels after normalization with tubulin in comparison with the levels in cells with the empty-vector control. Error bars represent standard deviations of the results for repeated experiments.

As the substitution at nucleotide 55 diminished the ability of Nsp1β to induce KPNA1 degradation, we reasoned that the mutant Nsp1β would be different from wild-type Nsp1β in the JAK/STAT signaling pathway. HEK293 cells were transfected with wild-type and mutant Nsp1β plasmids of VR-2385. IFN-α was added to the cells 48 h after the transfection. The cells were harvested 10 h after the IFN stimulation for RNA isolation and RT-qPCR to determine the transcript levels of ISG15 and ISG56. The results showed that the cells with expression of the mutant Nsp1β had transcript levels of ISG15 and ISG56 similar to the levels in cells with empty vector (Fig. 6C). The cells with wild-type Nsp1β had significantly lower levels of ISG15 and ISG56 transcripts, as expected. Western blotting showed that after IFN treatment, the STAT2 protein level was considerably lower in cells with Nsp1β expression than in cells with empty vector. Conversely, the cells with mutant Nsp1β had STAT2 levels similar to the levels in cells with the empty-vector control (Fig. 6D).

To confirm the effect of valine-19 on Nsp1β, we conducted mutagenesis of MLV Nsp1β to mutate isoleucine-19 to valine. As expected, the mutant MLV Nsp1β reduced KPNA1 levels (Fig. 6E). Densitometry analysis showed that the KPNA1 level in the cells with mutant MLV Nsp1β was 0.5-fold in comparison to the levels in cells with the wild-type Nsp1β (Fig. 6F). These results demonstrated that valine-19 was correlated with Nsp1β's reduction of KPNA1 and inhibition of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway.

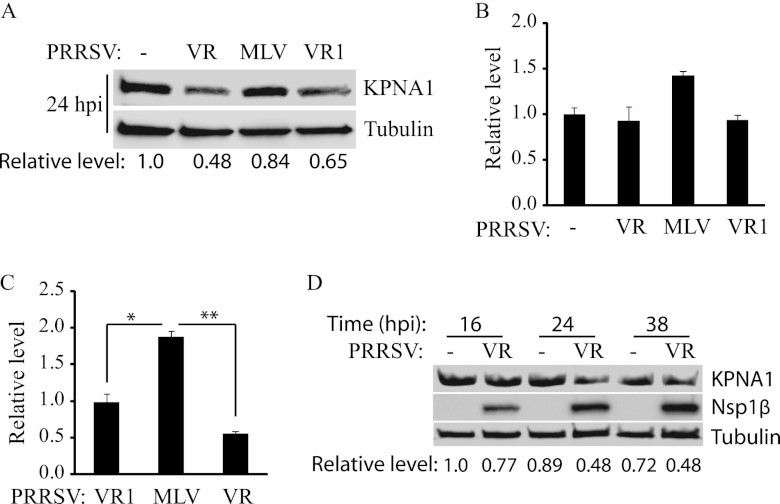

PRRSV infection reduces endogenous KPNA1.

The results described above showed that Nsp1βs of both VR-2385 and VR-2332 reduced KPNA1 levels. We reasoned that endogenous KPNA1 protein in MARC-145 cells would decrease after PRRSV infection. MARC-145 cells were infected with PRRSV strain VR-2385, MLV, or VR-2332 and were harvested 24 h postinfection (h.p.i.) for Western blotting. Compared to the levels in mock-infected cells, KPNA1 levels in cells infected with VR-2385 and VR-2332 were reduced to 0.48- and 0.65-fold, respectively, while the protein remained at 0.84-fold in the cells infected with MLV (Fig. 7A). To test whether the KPNA1 mRNA level in MARC-145 cells changed after PRRSV infection, RT-qPCR was conducted. The results showed that KPNA1 transcripts in the cells with PRRSV infection had no significant difference from those in control cells (Fig. 7B). PRRSV genomic RNA was also detected in the cells with PRRSV infection. The cells infected with MLV produced significantly more copies of viral RNA than cells infected with the other two strains (Fig. 7C). As expected, MLV replicated faster than the other two strains in MARC-145 cells.

Fig 7.

Reduction of endogenous KPNA1 levels by infection with PRRSV strains VR-2385 and VR-2332. (A) Endogenous KPNA1 protein levels in MARC-145 cells after PRRSV infection. MARC-145 cells were infected with PRRSV strain VR-2385, MLV, or VR-2332 and harvested 24 h.p.i. for Western blotting. Lysate of mock-infected cells was included as a control. Fold changes of KPNA1 protein levels are shown below the images. VR, VR-2385; VR1, VR-2332. (B) KPNA1 mRNA levels in MARC-145 cells after PRRSV infection. RT-qPCR was done to quantify KPNA1 mRNA at 24 h.p.i. Fold changes in comparison with the levels in mock-infected cells are shown. Error bars represent standard deviations of the results for repeated experiments. (C) PRRSV RNA in MARC-145 cells detected by RT-qPCR. Fold changes in comparison with the amounts of mRNA in VR-2332-infected cells are shown. Significant differences between viral RNA levels are indicated as follows: *, P < 0.05, and **, P < 0.01. Error bars represent standard deviations of the results for repeated experiments. (D) Kinetics of endogenous KPNA1 levels in MARC-145 cells after VR-2385 infection. The cells were harvested at the indicated times (h) after infection. Fold changes of KPNA1 levels are shown below the images.

To test the kinetics of KPNA1 expression after PRRSV infection, we infected MARC-145 cells with VR-2385 and harvested the cells at 16, 24, and 38 h.p.i. Compared to the levels in mock-infected cells, the KPNA1 levels in the virus-infected cells were reduced at 16 h.p.i. and were considerably decreased at 24 and 38 h.p.i. (Fig. 7D). The Nsp1β expression increased with extension of infection time. Densitometry analysis showed that the KPNA1 levels at 16, 24, and 38 h.p.i. were 0.77-, 0.48-, and 0.48-fold, respectively, compared to the levels in mock-infected cells at 16 h.p.i. The results showed that KPNA1 was reduced in the PRRSV-infected cells, which is consistent with our data from Nsp1β overexpression.

DISCUSSION

Previous data show that PRRSV inhibits the ability of type I IFNs to induce an antiviral response in MARC-145 and PAM cells and that Nsp1β is involved in the inhibition (19). In this study, the mechanism for Nsp1β-mediated inhibition of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway was examined. The increased degradation of KPNA1 appears to be the reason, and valine-19 in Nsp1β is correlated with the change in KPNA1 levels. Several lines of evidence were provided in this study to support the conclusion. First, Nsp1β leads to lower levels of exogenous overexpressed KPNA1. The interaction of pSTAT1 with KPNA1 after IFN stimulation was examined. The cells with Nsp1β expression had smaller amounts of pSTAT1/KPNA1 complexes. The total levels of pSTAT1 remained unchanged, while the total KPNA1 levels were reduced in the cells with Nsp1β expression. MLV Nsp1β did not affect the KPNA1 level or KPNA1 interaction with pSTAT1, which is consistent with the previous data showing that MLV Nsp1β does not inhibit pSTAT1 nuclear translocation (19).

KPNA1 degradation appeared to be due to the ubiquitin-mediated proteasome pathway. Nsp1β induced KPNA1 degradation in a dose-dependent manner. The mechanism for the KPNA1 reduction was explored at the mRNA and protein levels. The KPNA1 transcript levels changed minimally in the cells with Nsp1β expression. Blocking the ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation pathway with MG132 resulted in the restoration of KPNA1 levels in the cells with Nsp1β. These results indicated that the proteasome pathway was involved in the Nsp1β-induced degradation of KPNA1. IP results showed that ubiquitination of KPNA1 in cells with Nsp1β expression was significantly increased. Moreover, the KPNA1 half-life was reduced from 21 h to 6 h, which further substantiates the observation of KPNA1 degradation. Since Nsp1β reduced KPNA1, we wondered whether it would interact with KPNA1 or not. IP with FLAG antibody to pull down KPNA1-FLAG and then Western blotting with HA antibody failed to detect Nsp1β-HA (results not shown). Conversely, IP with HA antibody and Western blotting with FLAG antibody did not detect KPNA1-FLAG either. The results indicated that KPNA1 and Nsp1β had undetectable or no interaction.

The amino-terminal half of Nsp1β contains the functional domain responsible for the KPNA1 degradation. Analysis of the four truncation constructs showed that the N-terminal domain (amino acids 1 to 55) of Nsp1β was correlated with the KPNA1 level change. The deletion constructs D1 and D2 contain the N-terminal domain. Their expression resulted in KPNA1 reduction to a level similar to that induced by the full-length Nsp1β. The deletion constructs D3 and D4 do not have the N-terminal domain, and their expression had minimal effects on KPNA1 levels. Interestingly, all four truncated Nsp1βs had cytoplasmic distribution, while the full-length Nsp1β mainly locates in the nucleus. The results indicate that the cytoplasmic distribution of the full-length Nsp1β was involved in the KPNA1 reduction, as D1 and D2 reduced KPNA1 to levels similar to the level induced by the full-length Nsp1β. The cytoplasmic distribution of the four truncated Nsp1βs also indicates that the nuclear localization signal of Nsp1β was disrupted in the short fragments. Crystallization of Nsp1β showed that amino acids 1 to 48 comprise a nuclease domain, amino acids 49 to 84 the linker domain, amino acids 85 to 181 a papain-like cysteine protease (PCP) domain, and amino acids 182 to 203 the C-terminal extension (34). Our results showed that the N-terminal nuclease domain of Nsp1β correlates with the KPNA1 degradation, indicating that the domain has additional functions. A recent report also showed that the nuclease domain of Nsp1β correlates with inhibition of type I IFN induction (35).

Valine-19 of Nsp1β is associated with the KPNA1 degradation. A mutation at nucleotide 55 from G to A diminished VR-2385 Nsp1β's ability to inhibit the JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Both VR-2385 and VR-2332 reduced KPNA1, while MLV did not. There were only two nucleotides that differed between the VR-2332 and MLV Nsp1βs, which were potentially associated with the KPNA1 reduction. Nucleotide 55 was selected for mutagenesis because the amino-terminal domain (amino acids 1 to 55) was found to correlate with KPNA1 reduction. Interestingly, the amino acid change from valine to isoleucine in VR-2385 Nsp1β abolished its ability to reduce KPNA1. Expression of this mutant VR-2385 Nsp1β in HEK293 cells had little effect on IFN-activated JAK/STAT signaling. Conversely, the amino acid change from isoleucine to valine in MLV Nsp1β caused reduction of KPNA1. These results indicate that valine-19 is important for the Nsp1β-induced degradation of KPNA1. The mutation from valine to isoleucine might affect the interaction of Nsp1β and an unknown protein that leads to the ubiquitination of KPNA1. A lysine and a serine are the residues immediately upstream and downstream from valine-19. Common posttranslational modifications, including methylation, ubiquitination, and phosphorylation, often occur on these two amino acids in many proteins. Thus, they might play a bigger role in the interaction of Nsp1β and the unknown protein. The presence of valine or isoleucine between these two amino acids might lead to different conformations in the Nsp1β domain. Sequence alignment revealed that residue 19 of Nsp1βs is either valine or isoleucine, which are highly conserved across the strains in type 2 PRRSV (data not shown). The stretch of residues around valine-19 has also been shown by a recent report to be involved in inhibition of type I IFN induction (35). Residues 16 to 20 of Nsp1β were mutated to alanine in an infectious cDNA clone, and the mutant virus recovered was able to induce higher levels of type I IFN transcripts in infected macrophages. However, the nuclease or protease activity of Nsp1β seems to be unrelated to its ability to enhance KPNA1 ubiquitination, because Nsp1βs of VR-2332 and MLV have only two different amino acids that do not affect nuclease or protease activity (34, 36). Nsp1β is the second of the nonstructural proteins encoded by PRRSV ORF1a and has drawn attention due to its ability to inhibit interferon induction and IFN-activated JAK/STAT signaling (19, 33, 35, 37, 38), interact with cellular poly(C) binding protein (39), and suppress tumor necrosis factor alpha promoter activation (40).

PRRSV infection leads to a reduction of endogenous KPNA1. KPNA1 levels were reduced in the cells infected with VR-2385 and VR-2332, but MLV replication did not reduce KPNA1 levels. The KPNA1 reduction was not due to KPNA1 mRNA changes, as cells infected with different strains had similar levels of KPNA1 mRNA transcripts. Kinetic studies of KPNA1 levels confirmed the KPNA1 reduction in the virus-infected cells. The results indicate that Nsp1β may play a role in the inhibition of IFN-activated signaling in the virus-infected cells.

KPNA mediates the nuclear import of many cytoplasmic proteins (41, 42). KPNA1 is essential to the nuclear transport of phosphorylated STAT1 (43). Therefore, KPNAs have been targeted by some viruses to interfere with IFN-activated JAK/STAT signaling. For example, Ebola virus VP24 binds KPNA1 and blocks pSTAT1 nuclear translocation (27, 44). VP24 interacts with KPNA1 in the region overlapping with pSTAT1. The ORF6 product of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus disrupts nuclear import of pSTAT1 by tethering KPNA2 to the endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi membrane (45).

The E3 ubiquitin ligase for KPNA1 degradation is not known, although RAG1 ubiquitin ligase was reported to interact with KPNA1 (46). RAG1 is also a recombinase involved in DNA rearrangement of immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor genes in B and T lymphocytes. KPNA1 is a putative substrate of RAG1 (46), but degradation of KPNA1 was not demonstrated. In addition, RAG1 distribution could be limited to the immune cells. Thus, RAG1 is not likely to be the Nsp1β-targeted E3 ligase for KPNA1 ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. Our IP did not detect interaction between Nsp1β and KPNA1, which excluded the possibility of Nsp1β as an E3 ligase. Further work is needed to identify the E3 ligase for the Nsp1β-mediated KPNA1 degradation.

In conclusion, the mechanism of PRRSV Nsp1β inhibition of JAK/STAT signaling was discovered in this study. Nsp1β induced degradation of either overexpressed or endogenous KPNA1. PRRSV infection of MARC-145 cells led to lower KPNA1 levels. The presence of valine-19 in the N-terminal domain of Nsp1β was found to correlate with the KPNA1 degradation. This is the first report that a viral protein targets cellular importin for degradation. Our study provides further insight into PRRSV interference with the IFN-mediated antiviral response.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank K. S. Faaberg at the National Animal Disease Center, Ames, IA, M. L. Shaw at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY, and X. Zhu at University of Maryland, College Park, MD, for some of the reagents used in this study.

R. Wang, Y. Nan, and Y. Yu were partially supported by the China Scholarship Council. Partial funding for this study was provided by The National Pork Board.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 28 February 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Faaberg KS, Balasuriya UB, Brinton MA, Gorbalenya AE, Leung FC-C, Nauwynck H, Snijder EJ, Stadejek T, Yang H, Yoo D. 2011. Family Arteriviridae. In King AMQ, Lefkowitz E, Adams MJ, Carstens EB. (ed), Virus taxonomy. Ninth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier Academic Press, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 2. Neumann EJ, Kliebenstein JB, Johnson CD, Mabry JW, Bush EJ, Seitzinger AH, Green AL, Zimmerman JJ. 2005. Assessment of the economic impact of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome on swine production in the United States. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 227:385–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Conzelmann KK, Visser N, Van Woensel P, Thiel HJ. 1993. Molecular characterization of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus, a member of the arterivirus group. Virology 193:329–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meulenberg JJ, de Meijer EJ, Moormann RJ. 1993. Subgenomic RNAs of Lelystad virus contain a conserved leader-body junction sequence. J. Gen. Virol. 74(Pt 8):1697–1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mardassi H, Mounir S, Dea S. 1995. Molecular analysis of the ORFs 3 to 7 of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus, Quebec reference strain. Arch. Virol. 140:1405–1418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meulenberg JJ, Petersen-Den Besten A, De Kluyver EP, Moormann RJ, Schaaper WMM, Wensvoort G. 1995. Characterization of proteins encoded by ORFs 2 to 7 of Lelystad virus. Virology 206:155–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim HS, Kwang J, Yoon IJ, Joo HS, Frey ML. 1993. Enhanced replication of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus in a homogeneous subpopulation of MA-104 cell line. Arch. Virol. 133:477–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rossow KD, Collins JE, Goyal SM, Nelson EA, Christopher Hennings J, Benfield DA. 1995. Pathogenesis of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection in gnotobiotic pigs. Vet. Pathol. 32:361–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Albina E, Carrat C, Charley B. 1998. Interferon-alpha response to swine arterivirus (PoAV), the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 18:485–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Buddaert W, Van Reeth K, Pensaert M. 1998. In vivo and in vitro interferon (IFN) studies with the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV). Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 440:461–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miller LC, Laegreid WW, Bono JL, Chitko-McKown CG, Fox JM. 2004. Interferon type I response in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus-infected MARC-145 cells. Arch. Virol. 149:2453–2463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Labarque GG, Nauwynck HJ, Van Reeth K, Pensaert MB. 2000. Effect of cellular changes and onset of humoral immunity on the replication of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in the lungs of pigs. J. Gen. Virol. 81:1327–1334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xiao Z, Batista L, Dee S, Halbur P, Murtaugh MP. 2004. The level of virus-specific T-cell and macrophage recruitment in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection in pigs is independent of virus load. J. Virol. 78:5923–5933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gonzalez-Navajas JM, Lee J, David M, Raz E. 2012. Immunomodulatory functions of type I interferons. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 12:125–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Takaoka A, Yanai H. 2006. Interferon signalling network in innate defence. Cell. Microbiol. 8:907–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Darnell JE, Jr, Kerr IM, Stark GR. 1994. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science 264:1415–1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schindler C, Darnell JE., Jr 1995. Transcriptional responses to polypeptide ligands: the JAK-STAT pathway. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64:621–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stark GR, Kerr IM, Williams BR, Silverman RH, Schreiber RD. 1998. How cells respond to interferons. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67:227–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Patel D, Nan Y, Shen M, Ritthipichai K, Zhu X, Zhang YJ. 2010. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus inhibits type I interferon signaling by blocking STAT1/STAT2 nuclear translocation. J. Virol. 84:11045–11055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Meng XJ, Paul PS, Halbur PG. 1994. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequencing of the 3′-terminal genomic RNA of the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J. Gen. Virol. 75(Pt 7):1795–1801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Collins JE, Benfield DA, Christianson WT, Harris L, Hennings JC, Shaw DP, Goyal SM, McCullough S, Morrison RB, Joo HS, Gorcyca D, Chladek D. 1992. Isolation of swine infertility and respiratory syndrome virus (isolate ATCC VR-2332) in North America and experimental reproduction of the disease in gnotobiotic pigs. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 4:117–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yuan S, Nelsen CJ, Murtaugh MP, Schmitt BJ, Faaberg KS. 1999. Recombination between North American strains of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Virus Res. 61:87–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang YJ, Stein DA, Fan SM, Wang KY, Kroeker AD, Meng XJ, Iversen PL, Matson DO. 2006. Suppression of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus replication by morpholino antisense oligomers. Vet. Microbiol. 117:117–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Timofeeva OA, Plisov S, Evseev AA, Peng S, Jose-Kampfner M, Lovvorn HN, Dome JS, Perantoni AO. 2006. Serine-phosphorylated STAT1 is a prosurvival factor in Wilms' tumor pathogenesis. Oncogene 25:7555–7564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nan Y, Wang R, Shen M, Faaberg KS, Samal SK, Zhang YJ. 2012. Induction of type I interferons by a novel porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus isolate. Virology 432:261–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang YJ, Wang KY, Stein DA, Patel D, Watkins R, Moulton HM, Iversen PL, Matson DO. 2007. Inhibition of replication and transcription activator and latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus by morpholino oligomers. Antiviral Res. 73:12–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reid SP, Leung LW, Hartman AL, Martinez O, Shaw ML, Carbonnelle C, Volchkov VE, Nichol ST, Basler CF. 2006. Ebola virus VP24 binds karyopherin α1 and blocks STAT1 nuclear accumulation. J. Virol. 80:5156–5167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Patel D, Opriessnig T, Stein DA, Halbur PG, Meng XJ, Iversen PL, Zhang YJ. 2008. Peptide-conjugated morpholino oligomers inhibit porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus replication. Antiviral Res. 77:95–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Patel D, Stein DA, Zhang YJ. 2009. Morpholino oligomer-mediated protection of porcine pulmonary alveolar macrophages from arterivirus-induced cell death. Antivir. Ther. 14:899–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-delta delta C(T)) method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang Y, Sharma RD, Paul PS. 1998. Monoclonal antibodies against conformationally dependent epitopes on porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Vet. Microbiol. 63:125–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kannan H, Fan S, Patel D, Bossis I, Zhang YJ. 2009. The hepatitis E virus open reading frame 3 product interacts with microtubules and interferes with their dynamics. J. Virol. 83:6375–6382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen Z, Lawson S, Sun Z, Zhou X, Guan X, Christopher-Hennings J, Nelson EA, Fang Y. 2010. Identification of two auto-cleavage products of nonstructural protein 1 (nsp1) in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infected cells: nsp1 function as interferon antagonist. Virology 398:87–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Xue F, Sun Y, Yan L, Zhao C, Chen J, Bartlam M, Li X, Lou Z, Rao Z. 2010. The crystal structure of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nonstructural protein Nsp1β reveals a novel metal-dependent nuclease. J. Virol. 84:6461–6471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Beura LK, Subramaniam S, Vu HL, Kwon B, Pattnaik AK, Osorio FA. 2012. Identification of amino acid residues important for anti-IFN activity of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus non-structural protein 1. Virology 433:431–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kroese MV, Zevenhoven-Dobbe JC, Bos-de Ruijter JN, Peeters BP, Meulenberg JJ, Cornelissen LA, Snijder EJ. 2008. The nsp1alpha and nsp1 papain-like autoproteinases are essential for porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus RNA synthesis. J. Gen. Virol. 89:494–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Beura LK, Sarkar SN, Kwon B, Subramaniam S, Jones C, Pattnaik AK, Osorio FA. 2010. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nonstructural protein 1β modulates host innate immune response by antagonizing IRF3 activation. J. Virol. 84:1574–1584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kim O, Sun Y, Lai FW, Song C, Yoo D. 2010. Modulation of type I interferon induction by porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus and degradation of CREB-binding protein by non-structural protein 1 in MARC-145 and HeLa cells. Virology 402:315–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Beura LK, Dinh PX, Osorio FA, Pattnaik AK. 2011. Cellular poly(C) binding proteins 1 and 2 interact with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nonstructural protein 1beta and support viral replication. J. Virol. 85:12939–12949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Subramaniam S, Kwon B, Beura LK, Kuszynski CA, Pattnaik AK, Osorio FA. 2010. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus non-structural protein 1 suppresses tumor necrosis factor-alpha promoter activation by inhibiting NF-kappaB and Sp1. Virology 406:270–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chook YM, Blobel G. 2001. Karyopherins and nuclear import. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11:703–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stewart M. 2007. Molecular mechanism of the nuclear protein import cycle. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8:195–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sekimoto T, Imamoto N, Nakajima K, Hirano T, Yoneda Y. 1997. Extracellular signal-dependent nuclear import of Stat1 is mediated by nuclear pore-targeting complex formation with NPI-1, but not Rch1. EMBO J. 16:7067–7077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Reid SP, Valmas C, Martinez O, Sanchez FM, Basler CF. 2007. Ebola virus VP24 proteins inhibit the interaction of NPI-1 subfamily karyopherin α proteins with activated STAT1. J. Virol. 81:13469–13477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Frieman M, Yount B, Heise M, Kopecky-Bromberg SA, Palese P, Baric RS. 2007. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus ORF6 antagonizes STAT1 function by sequestering nuclear import factors on the rough endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi membrane. J. Virol. 81:9812–9824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Simkus C, Makiya M, Jones JM. 2009. Karyopherin alpha 1 is a putative substrate of the RAG1 ubiquitin ligase. Mol. Immunol. 46:1319–1325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]