Abstract

The major capsid protein of norovirus VP1 assembles to form an icosahedral viral particle. Despite evidence that the Norwalk virus (NV) minor structural protein VP2 is present in infectious virions, the available crystallographic and electron cryomicroscopy structures of NV have not revealed the location of VP2. In this study, we determined that VP1 associates with VP2 at the interior surface of the capsid, specifically with the shell (S) domain of VP1. We mapped the interaction site to amino acid 52 of VP1, an isoleucine located within a sequence motif IDPWI in the S domain that is highly conserved across norovirus genogroups. Mutation of this isoleucine abrogated VP2 incorporation into virus-like particles without affecting the ability for VP1 to dimerize and form particles. The highly basic nature of VP2 and its location interior to the viral particle are consistent with its potential role in assisting capsid assembly and genome encapsidation.

INTRODUCTION

Noroviruses are nonenveloped viruses with a single-stranded RNA genome of positive polarity and are the leading cause of acute gastroenteritis (1). Infection causes outbreaks of food-borne illness in the community and produces symptoms of vomiting and diarrhea. Noroviruses belong to the Caliciviridae family that is comprised of five genera: Norovirus, Sapovirus, Lagovirus, Vesivirus, and Nebovirus (2). The first two genera contain primarily human viruses, while the other genera represent animal viruses. The noroviruses are genetically diverse since they are divided into six genogroups based on the amino acid sequence of the major structural protein VP1. The noncultivable human noroviruses in genogroups I and II are epidemiologically important (3) and are further subdivided into at least 8 and 21 genotypes, respectively. Norwalk virus (NV) is a prototype member of the Norovirus genus and is designated GI.1, and GII noroviruses such as the GII.4 Houston virus (HoV) are increasingly prevalent in more recent outbreaks (4, 5).

The NV genome encodes three open reading frames (ORFs) and ORF1 encodes a large nonstructural polyprotein of 1,789 amino acids. This polyprotein is autocatalytically processed by the viral protease to yield six nonstructural proteins (p48 N-terminal protein, p41 NTPase, p22, VPg, protease, and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase [RdRp]) that are thought to function primarily for viral RNA replication. The structural proteins VP1 and VP2, which form the viral capsid, are translated from a subgenomic mRNA that is 3′ coterminal with the viral genome and codes for ORF2 and ORF3 (6–10). In NV, ORF2 overlaps ORF1 and ORF3 by 17 and 1 nucleotides, respectively.

The ability to express the norovirus capsid protein to a high levels in insect cells using the baculovirus system and the fact that VP1 proteins will self-assemble into particles that are morphologically and antigenically similar to infectious virions has enabled the structural characterization of the norovirus capsids by cryoelectron microscopy reconstruction and by X-ray crystallography (11–13). These structures are fundamentally similar among caliciviruses (14–16). Caliciviruses contain a T=3, icosahedral capsid composed of 180 molecules of VP1 organized into 90 dimers that form an ∼35-nm-diameter icosahedral shell. The VP1 protein consists of the internal N-terminal, shell (S) and protruding (P) domains. The S domain contains an eight-stranded antiparallel beta-barrel fold, separated by a flexible hinge that precedes the P domain where most residues involved in dimeric contacts reside (12). Expression of the S domain alone, however, still allows VP1 dimer formation and results in the production of smooth VLPs with smaller particle diameters (17). Sequence and structural variations in the P domain correlate with receptor binding, escape from neutralizing antibodies, and strain diversity. The major capsid protein VP1 engages ABO histo-blood group antigens, glycans which serve as initial attachment molecules for norovirus infection (18, 19).

VP2 is present in the infectious virions of feline calicivirus (FCV), NV, and likely in all caliciviruses (20, 21). In FCV, VP2 stabilizes the icosahedral capsid and is required for the production of infectious virus (22). Although found in norovirus virions purified from stools of NV-infected volunteers (20), VP2 is not essential for the formation of recombinant virus-like particles (VLPs) (17). However, the absence of VP2 decreases the stability and size homogeneity of the VLPs when they are produced in insect cells (23), and VP2 is thought to be involved in the viral assembly (20, 22). High-resolution X-ray crystallographic structures of three caliciviruses—NV VLPs (12, 24), San Miguel Sea lion virus (15, 25), and FCV (26)—have been solved, but the density of the minor capsid protein VP2 has not been detected. Lower-resolution cryoelectron microscopy structures of murine norovirus and rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus also left VP2 unresolved (16). The process of structural determination requiring the implicit use of icosahedral symmetry averaging combined with relatively few copies of VP2 per virion may account for the absence of VP2 in the structure. The lack of VP2 structural data has hindered further elucidation of the function this protein plays during the norovirus life cycle. In the present study, we took a biochemical approach to characterize where and how norovirus VP1 associates with the minor capsid VP2 to mediate particle assembly.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

Human embryonic kidney 293 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (CRL-1573) and maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Vero, CHO-K1, and Huh7 were also maintained similarly.

Construction of recombinant plasmids.

Norwalk (GenBank accession no. NC_001959) and Houston (GenBank no. EU310927) virus capsid genes VP1 and VP2 were amplified with KOD DNA polymerase (EMD Millipore) with flanking PacI and XhoI for NV and PacI and PspXI for HoV. PCR fragments were cloned into a mammalian expression vector pCG (27) (kindly provided by Roberto Cattaneo, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN) via PacI and SalI sites to generate pCG-NV-VP1, pCG-NV-VP2, and pCG-HoV-VP1. pCG-HoV-VP2-3×FLAG was similarly generated but with the addition of a 3× FLAG fused in-frame to the carboxyl terminus to facilitate detection with FLAG antibody. Construction of the NV shell domain (residues 1 to 225), the protruding domain (residues 226 to 530), and the amino-terminal truncation mutants of NV-VP1 also utilized flanking PacI and XhoI sites. The starting amino acid residue of each mutant precedes a guanine nucleotide when possible to favor eukaryotic translation under the Kozak rule (28). The introduction of amino acid changes was subsequently accomplished on pCG-NV-VP1 and pCG-HoV-VP1 using QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Agilent Technologies) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The annealing temperatures for the primers used ranged from 55 to 58°C, and the amplifications were ca. 13 to 18 cycles. To minimize structural interferences, which may lead to reduced protein folding, we substituted charged and polar residues to alanine, and apolar residues to serine. All constructs used in the present study were confirmed by sequencing.

Coimmunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis.

To assess the association of VP1 and VP2, 293 cells were seeded on six-well tissue culture plate without antibiotics and allowed to reach ∼90% confluence prior to transfection. Equal amounts of VP1 and VP2 plasmids were transfected into the cells by using jetPRIME (Polyplus Transfection) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Where necessary, pEGFP-N1 (Clontech) was used to maintain an equal amount of DNA in transfection. At 36 to 48 h posttransfection, cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% sodium deoxycholate, and 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Calbiochem), and the lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. Cell lysates were incubated with a mouse monoclonal antibody 8812 to the NV VP1 capsid protein (29, 30) and protein G-agarose (Roche). The complex was washed twice with RIPA buffer and boiled for 5 min prior to loading. In Western blots, proteins were fractionated on sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad) and blotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore). The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk powder in phosphate-buffered saline and 0.1% Tween 20. Antibodies used were against NV VP1 and VP2 (20), HoV VP1 (31), and FLAG (Sigma) to detect the 3× FLAG-tagged HoV-VP2, followed by peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Sigma). Proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare).

Purification of virus-like particles (VLPs).

Cells coexpressing VP2 together with either wild-type or I52 mutant VP1 were harvested in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 48 h posttransfection. Cells were freeze-thawed and centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 10 min to remove cellular debris. Lysates were passed through a 1.2-μm-pore-size filter and applied to a 30% sucrose cushion ultracentrifugation for 3 h in a Beckman SW28 rotor at 26,000 rpm (124,000 × g). The resulting pellet was then suspended in sterile water and sedimented through isopycnic CsCl gradient centrifugation (1.36 g/cm3) using a Beckman SW55 Ti rotor at 35,000 rpm (116,000 × g) for 24 h. The band containing the VLPs was collected for analysis either by diluting in sterile water and pelleting by centrifugation again for 2 h in a Beckman SW28 rotor at 26,000 rpm, or buffer-exchanged and concentrated using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters (Millipore).

Electron microscopic (EM) and structural studies.

The 1GC 400 copper Pelco grids (Ted Pella) were prepared with collodion (Parlodion) 2% in sterile amyl acetate (Electron Microscopy Sciences) suspended on a 10-cm dish filled with double-distilled H2O. The grids were coated with glow-discharged carbon. Samples were placed on a length of parafilm for staining. VLP samples were absorbed onto the grids for 5 min and stained for 15 s with either 1% (wt/vol) aqueous uranyl acetate (pH 5.0) or 1% (wt/vol) ammonium molybdate (pH 5.5). Excess stain was removed with the edge of a filter paper, and the grids were allowed to air dry. Micrographs were acquired under focus at a magnification of ×30,000 directly on a USB 1000 charge-coupled device camera connected to a JEOL543 transmission electron microscope operating at 80 kV. The VP1 protein structures and the vacuum electrostatic assignment of charges were analyzed with PyMOL (DeLano Scientific).

RESULTS

VP1-VP2 interaction results in increased capsid protein expression.

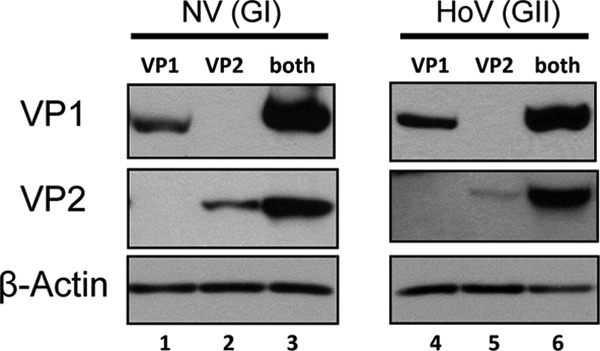

To better study the interaction of the norovirus capsid proteins in human cells, we constructed mammalian expression vectors for NV VP1 and VP2. VP1 and VP2 expressions were analyzed by Western blots after transfection of equal amounts of both VP1 and VP2 plasmids in mammalian cells. We initially observed an increased VP1 protein expression when the minor capsid protein VP2 was coexpressed compared to VP1 expressed alone (Fig. 1). The reverse was also true in that the presence of VP1 enhanced VP2 expression. Increased capsid protein expression when both VP1 and VP2 were present was also seen in HoV, a norovirus from genogroup II. These observations were consistently reproducible when the proteins were expressed in other mammalian cell lines (Huh7, Vero, and CHO) and in multiple independent experiments (data not shown). Furthermore, pulse-chase experiments of transient VP2 expression in 293 cells indicated the VP2 half-life is <1 h (unpublished data), consistent with the lower expression level seen in the absence of VP1. These results in mammalian cells confirmed previous studies in insect cells that showed coexpression of VP2 increased the yields and stability of VP1, which can result in increasing the half-life of VP1 >2-fold. Since their interactions may have contributed to the observed increase in protein expression when both VP1 and VP2 are present, we hypothesized that VP2 helped stabilize the major capsid protein by binding to critical regions on VP1.

Fig 1.

Norovirus VP1 and VP2 expression increases when both capsid proteins are present. Western blots of 293 cell lysates transfected with only VP1, VP2, or both VP1 and VP2 were analyzed with rabbit antisera specific for the protein as indicated to the left of each panel. HoV VP2 contained a 3× FLAG epitope and monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody was used for detection. β-Actin served as a loading control.

N-terminal truncations on VP1 affect VP2 association.

Previous studies of NV in the insect cell system also suggested that VP2 may be inside the viral capsid. The highly conserved S domain of VP1, encompassing residues 50 to 225, forms the contiguous icosahedral shell of the viral capsid and contributes significantly to the internal surface of the particle. The flexible N-terminal arm of VP1 (residues 1 to 49), which faces the interior of the particles, lacks a predominance of basic residues to implicate its involvement in interacting with the genomic RNA. Instead, we hypothesized that it may associate with VP2 (32). In contrast, the P domain (residues 226 to 530) is the most exposed and variable region on VP1 forming protrusions from the viral surface and therefore is not expected to interact with VP2. Previously, we showed that the first 20 N-terminal residues on VP1 are not important for VP2 association (33) or for VLP formation (17).

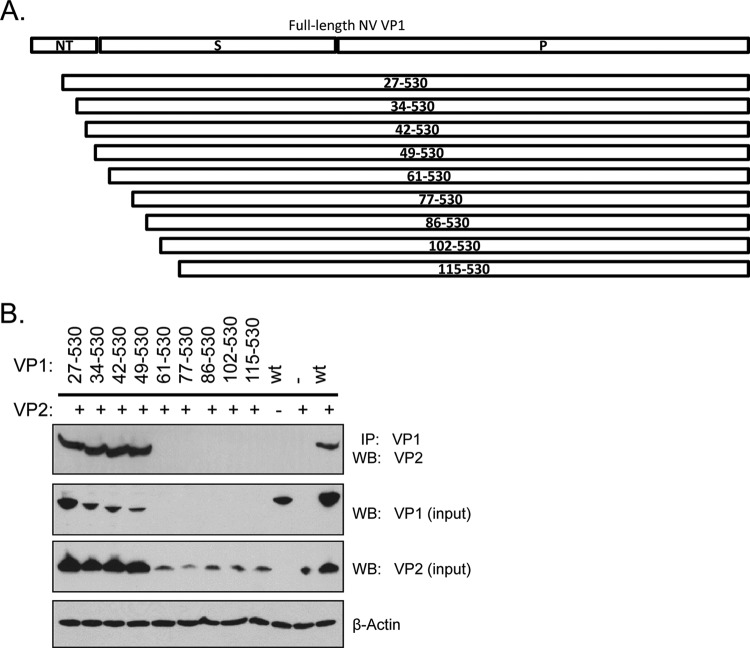

To examine the possible involvement of the N-terminal arm of VP1 in interacting with VP2, we generated a series of amino-terminal truncated VP1 mutants by selectively deleting up to 114 residues and assessed their abilities to interact with the minor capsid protein VP2 by coimmunoprecipitation (Fig. 2A). We observed that the truncated VP1 mutant lacking the first 48 residues (mutant 49-530) maintained interaction with VP2, but VP1 missing 60 residues or more at the N terminus expressed poorly and did not coprecipitate VP2 (Fig. 2B). In addition, a decrease in VP2 expression correlated with the drastic drop in VP1 expression on the Western blot. Since we expected that deletions greater than 61 residues would have begun to disrupt the β-strands intrinsic to the VP1 eight-strand fold, we generated an additional VP1 mutant lacking the first 54 residues. This mutant expressed approximately half the amount of mutant 49-530 but had negligible interaction with VP2 (data not shown). Furthermore, coimmunoprecipitation of full-length (wild-type) VP1 and VP2 was unperturbed by NaCl concentrations between 150 and 450 nM and various pHs ranging from 6.75 to 8.0 in the wash buffer. Taken together, these studies suggested that the first 48 amino acids from the N terminus of VP1 are not required for VP2 interactions and that the region between amino acids 49 to 60 affected VP2 association by influencing both VP1 and VP2 expression.

Fig 2.

Norwalk virus VP1 region encompassing residues 49 to 61 regulates capsid protein expression. (A) Schematic diagram of NV VP1 N-terminal truncation mutants generated. (B) Full-length unmodified (wt) or truncation mutant VP1 proteins (indicated by residue numbers) were coexpressed with VP2 and cell lysates subjected to coimmunoprecipitation. VP1 proteins were immunoprecipitated (IP) and associated VP2 resolved on a Western blot (WB). The presence of each protein in the lysates prior to immunoprecipitation is indicated to the right of each panel (input). NT, N-terminal arm; S, shell domain; P, protruding domain. Numbers denote VP1 amino acid residues.

VP2 interacts with the interior of the capsid shell.

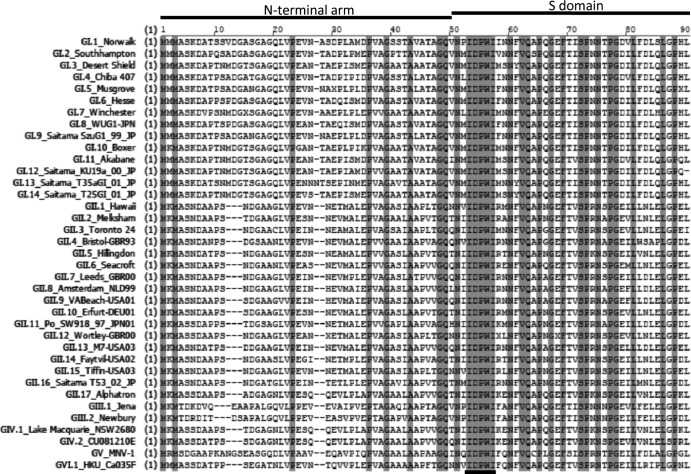

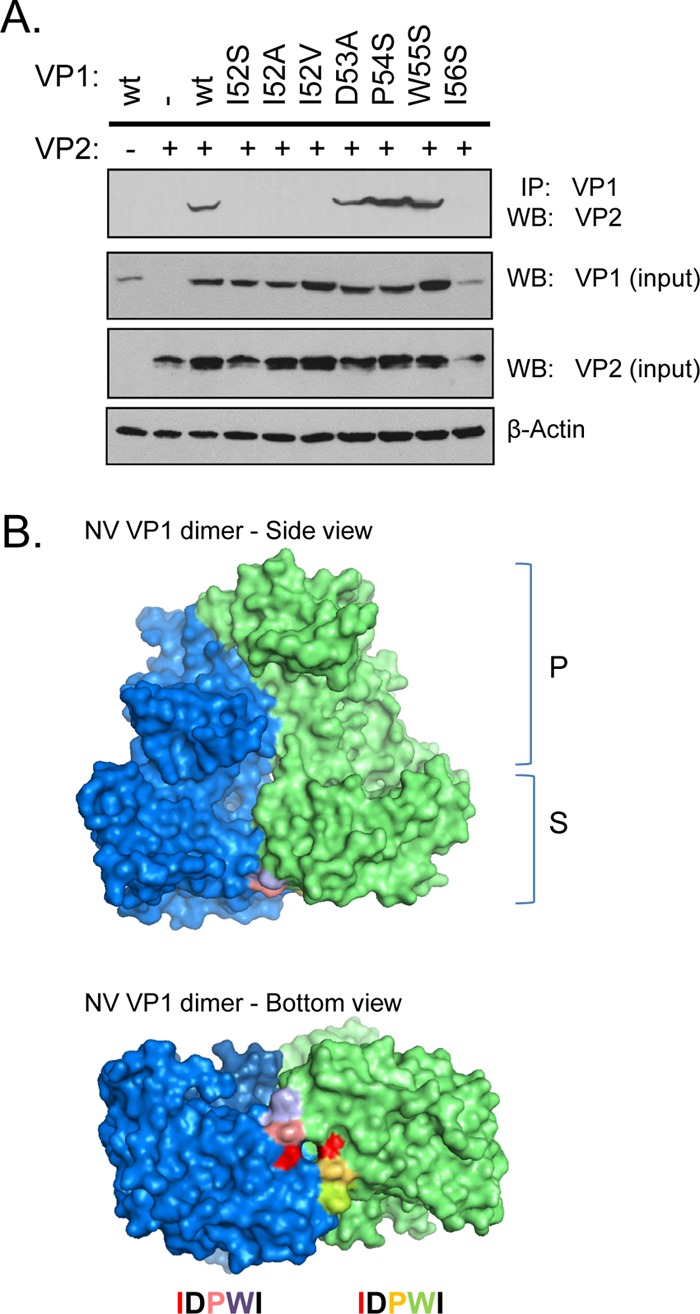

To further examine whether the region encompassing amino acids 49 to 60 consisted of any residues that are invariant among norovirus VP1, we performed amino acid sequence alignment of VP1 proteins from 14 GI, 17 GII, two GIII (bovine norovirus), two GIV (human and feline noroviruses), one GV (murine norovirus), and one GVI (canine norovirus) strains for which partial or full S domain sequences were available (Fig. 3). Strikingly, there were five consecutive identical residues at residues 52 to 56 of NV near the junction of the N-terminal and the S domain. This relatively long stretch of identical residues is not seen anywhere else nearby. These residues are Ile-52, Asp-53, Pro-54, Trp-55, and Ile-56, which partially overlap a short beta-sheet motif leading into the eight-stranded antiparallel beta sandwich core of the S domain. Since these residues lie within the critical region involved in VP2 interaction, we mutated residues in this motif in the context of a full-length VP1 and tested the ability of single mutants to interact with VP2. Mutations on VP1 at Asp-53, Pro-54, and Trp-55 expressed well and maintained interactions with VP2 (Fig. 4A). However, mutants Ile-52 and Ile-56 failed to coimmunoprecipitate VP2 despite being expressed. To further characterize the role of residue 52 in the interaction, different mutations were made at this position. Mutation to alanine, the smallest aliphatic amino acid, impaired association with VP2. On the other hand, valine, differing from isoleucine only because of the absence of the delta methyl group, also impaired association with VP2.

Fig 3.

Residues IDPWI (underlined) on VP1 are highly conserved among the shell domains of different noroviruses. Amino acid alignment of the N-terminal region of VP1 for which sequences were available from strains GI.1 to GI.14, GII.1 to GII.17, and representative strains from GIII through GVI. Identical residues are shaded gray.

Fig 4.

Isoleucine 52 on the Norwalk virus VP1 interacts with VP2 and maps to the shell domain. (A) Western blot of VP2 coimmunoprecipitated with different full-length VP1 proteins mutated at the indicated residues. (B) Mapping of the surface-exposed residues onto the structure of a VP1 dimer (each monomer shown in blue and green). The centrally located isoleucine 52 is in red. Black residues are buried and hence not visible on the structure.

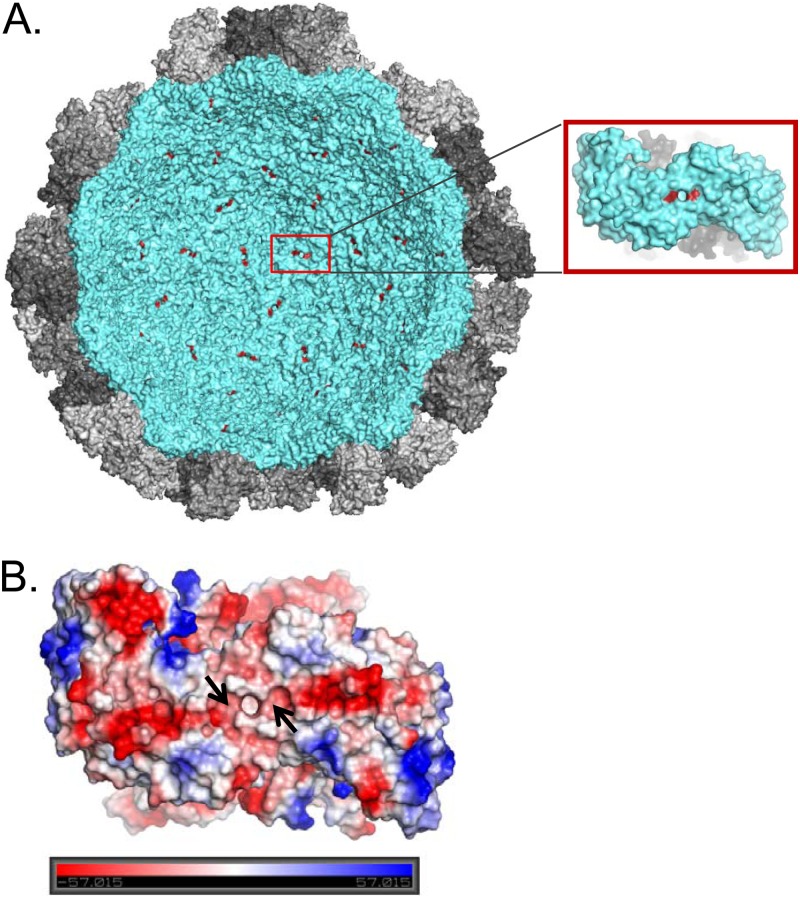

To visualize the location of these conserved IDPWI residues, we mapped their positions onto the atomic structure of the NV VP1 dimer (Fig. 4B). Asp-53 and Ile-56 are buried and therefore were uninformative (black color). Ile-52, Pro-54, and Trp-55 are surface exposed on the VP1 dimer. All three surface-exposed residues are located on the S domain facing the interior of the capsid shell. Since coimmunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated that only the mutation at Ile-52 affected VP2 association, the surface of residue Ile-52 (shown in red) was available for binding to VP2 but failed to do so when mutated. Taken together, these data indicate that Ile-52 located on the S domain is important for NV VP1 to interact with VP2.

The S domain of VP1 is sufficient to enhance VP2 expression.

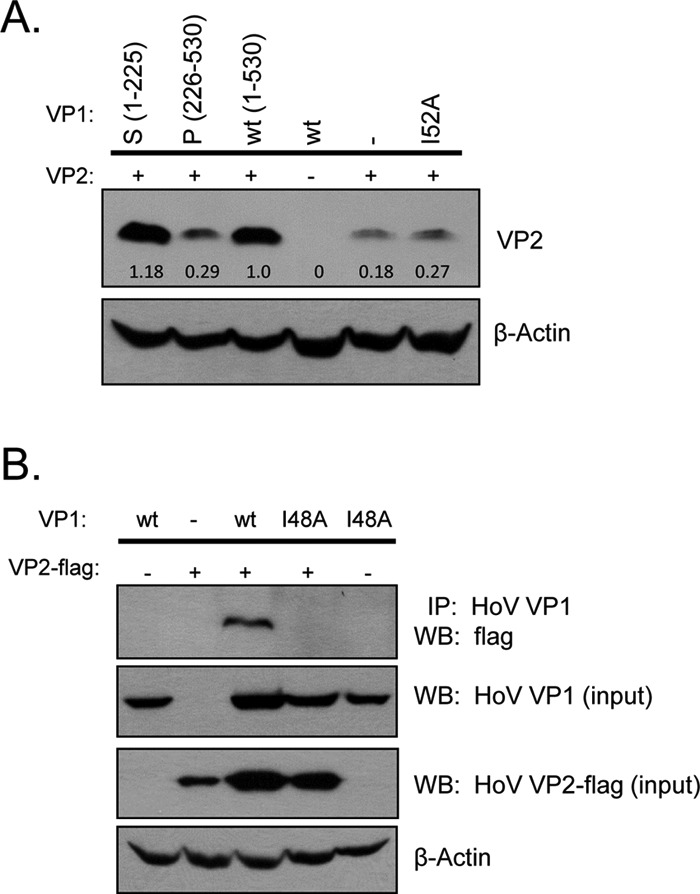

We sought to determine whether VP2 expression is affected by the presence of the S domain alone. When we coexpressed VP2 with the S domain (residues 1 to 225), the P domain (residues 226 to 530), full-length VP1 (wild type), or full-length VP1 mutated at Ile-52, we observed a reproducible increase in the expression of VP2 in the presence of the S domain on Western blot similar to that seen in the presence of the full-length VP1 (Fig. 5A). On the other hand, the P domain had no major effect on VP2 expression; the same level was seen as VP2 expressed alone. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments between the P domain and VP2 did not reveal any interaction (data not shown). Furthermore, VP1 containing a single mutation at Ile-52 failed to enhance VP2 expression, which may be due to its inability to associate with VP2. These data do not formally prove a role for direct binding of the S domain to VP2 but strongly suggest that the S domain alone is sufficient to interact with VP2.

Fig 5.

Norovirus shell domain with the conserved isoleucine is important for VP2 interaction in NV and HoV. (A) Western blot of VP2 from total cell lysates coexpressed with different NV VP1 proteins (the S domain, the P domain, full-length VP1 [wt], or full-length VP1 mutated at isoleucine 52 [I52A]). Numbers denote band quantitation using ImageJ. β-Actin served as a loading control. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation of HoV full-length VP1 (wt) or I48A mutant with FLAG-tagged VP2 in 293 cells. Coimmunoprecipitated complex was resolved with anti-FLAG antibody. Western blot of the input VP1 uses rabbit polyclonal specific for HoV VP1, and β-actin blot serves as loading control.

Conserved isoleucine is critical for VP1-VP2 interaction in GII HOV.

We next asked whether this isoleucine residue is critical for VP2 association in another norovirus from another genogroup. In HoV (GII genogroup), residues IDPWI correspond to amino acid positions 48 to 52. Isoleucine 52 on NV is therefore equivalent to HoV VP1 at position 48. HoV VP1 with a single Ile-48 mutation was then generated and coexpressed with HoV VP2. Coimmunoprecipitation experiment showed that this mutant also failed to interact with HoV VP2 (Fig. 5B). When mapped onto the unpublished crystal structure of HoV VP1, this Ile-48 was also surface exposed in the S domain interior similar to that seen on NV VP1. This highly conserved isoleucine residue, therefore, plays an important role in the ability of norovirus GI and GII VP1 proteins to interact with VP2.

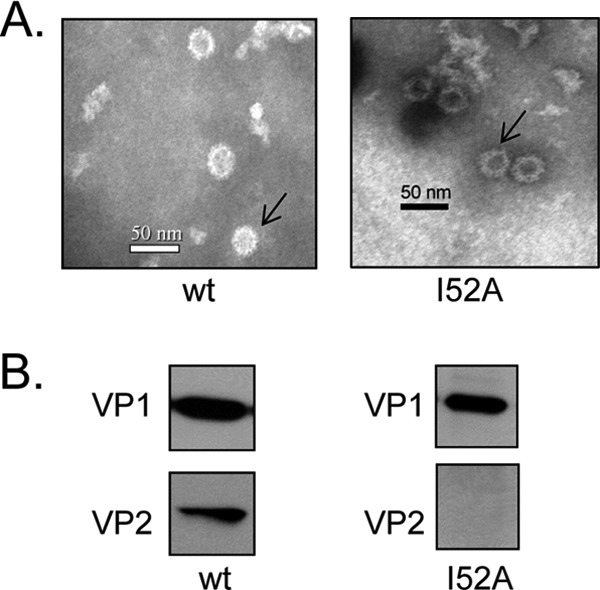

Mutated VP1 does not affect VLP formation, but these VLPs fail to incorporate VP2.

In the NV capsid structure, both P and S domains participate in dimeric interactions. Even in the absence of the P domain, the S domain alone can assemble into icosahedral shells, indicating that S domain dimeric interactions are crucial for the NV capsid. Since Ile-52 residue is located close to the S domain dimeric contact region, we sought to determine whether an Ile-52 mutation affected VP1 dimerization and consequently disrupted VP2 association in this manner. We assessed the ability for VP1 to dimerize by coexpressing VP2 with either wild type or the Ile-52 mutant VP1 in 293 cells and subjected the cell extracts to sucrose and CsCl gradient centrifugation. Protein bands were observed at CsCl density of 1.31 g/ml suggestive of empty VLPs (11, 34). Notably, this density is less than that of infectious virions purified from stool containing encapsidated viral nucleic acid (35, 36). Under EM, VLPs were seen from both wild-type and mutant VP1 with approximately 35 to 40 nm in diameter (Fig. 6A). These particles were morphologically similar to those produced in insect cells using recombinant baculovirus (11) or in mammalian cells using Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV) replicons (37). Therefore, we concluded that the Ile-52 mutant retained the ability to dimerize and subsequently participated in particle assembly.

Fig 6.

Wild-type NV VP1 and I52 mutant dimerized and assembled into VLPs, but the latter did not incorporate VP2. (A) Electron micrographs and Western blots of VLPs produced from capsid proteins expressed in 293 cells and purified VLPs negatively stained and visualized by EM. Arrows indicate representative VLPs. (B) Purified VLPs were analyzed on Western blot using specific antibodies. Overexposure revealed no additional bands.

Particles generated from these mammalian cells were cell associated similar to that reported with the VEEV system using BHK cells (37). No VLPs were observed in the culture medium. We observed fewer VLPs generated from the Ile-52 mutant VP1 expression compared to those expressed from the wild-type VP1 even though both samples were prepared and purified using identical conditions. To determine whether particles from mutant VP1 incorporated VP2 molecules, we analyzed the purified VLPs by Western blotting with rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific to either VP1 or VP2 and found that the VLPs generated from wild-type VP1 had VP2 incorporated (Fig. 6B). In contrast, no VP2 protein was detected in VLPs from the Ile-52 mutant. Moreover, overexposure of the Western blot did not reveal any VP2 band. We wanted to show that coexpression of the S domain and VP2 do form VLPs with incorporated VP2. However, we were unable to generate intact shell VLPs, possibly due to the low expression of the S domain or insufficient dimerization in the absence of the P domain. These findings implicate Ile-52 on VP1 as crucial for the association with VP2.

The VP2 interacting footprint exhibits possible charge complementarity.

To visualize how VP2 might associate with VP1, the half-shell spherical surface representation of the viral particle was generated using the available crystal structure information (Fig. 7A). Pairs of Ile-52 (labeled in red) from each VP1 dimer are prominently visible on the S domain (cyan) inside the particle and outline the 3- and 5-fold axes from within. The atomic distance of the intradimeric Ile-52 is ∼7.5 Å, while the interdimeric Ile-52 distance is ∼40 Å. Since VP2 is a highly basic protein and hence positively charged, we sought to determine whether the location of the Ile-52 pockets on VP1 is associated with a patch that exhibits complementary surface charge. Vacuum electrostatic analysis of the interior of the shell domain dimer revealed a surface-exposed belt consisting of locally negative charges (red regions) spanning across VP1 dimer and over the pocket where Ile-52 residues are located (Fig. 7B). It is unclear whether VP1-VP2 interaction is specific to any dimeric pairs among 90 VP1 dimers. However, these contact points may collectively allow VP2 to initially stabilize several VP1 dimers conducive for VP1 multimerization. Taken together, these results suggest that the overall capsid structure may benefit from VP2 “stitching” the VP1 molecules during the initiation of virion assembly.

Fig 7.

Interaction footprint mapped in the interior of the NV particle. (A) Surface representation of the cross-section of the NV particle highlighting the shell domain (cyan) and the protruding domain (gray). Inset, VP1 dimer with isoleucine 52 in red. (B) The electrostatic potential of the dimeric VP1 shell domain. Negatively (red) and positively (blue) charged areas are contoured at ±57 kT/e. Arrows indicate the positions of isoleucine 52.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we addressed the longstanding questions of where the norovirus minor capsid protein VP2 is located in the capsid and how it interacts with the major capsid protein VP1. Our data strongly suggest that VP2 resides in the interior of the capsid shell and the first isoleucine (Ile-52) in the IDPWI motif of the N-terminal arm of VP1, which is exceptionally conserved among noroviruses, is critical for the VP1-VP2 interaction. The Ile-52 residue is positioned at the center of a negatively charged belt across the surface of the S domain. The location of VP2 association with VP1, as ascertained from our study, is consistent with the long-held notion that the basic VP2 is involved in the packaging of the negatively charged viral genomic RNA. The VP1 capsid interior lacks an abundance of basic residues needed to bind RNA as seen for other T=3 icosahedral viruses such as tombusvirus and nodavirus (38, 39). In contrast, in noroviruses the basic VP2 may serve a similar function as the internal basic residues in these other viruses to mediate both the capsid assembly and the genome encapsidation.

Our first observation was that NV VP1 expression in mammalian cells is enhanced in the presence of VP2. This is consistent with an earlier study showing that NV VP1 expressed in insect cells has a half-life of 24 h in the presence of VP2, over twice as long as when VP1 is expressed alone (23). That study also demonstrated that VLPs made from coexpressed VP1 and VP2 are not only more resistant to pancreatin treatment but also more stable than those made solely from VP1. Viral proteins such as the measles virus hemagglutinin-fusion glycoproteins and Sindbis virus structural proteins E1-E2 are known to enhance the expression of one another due to their interactions (R. Cattaneo and C. Navaratnarajah, unpublished data). Such enhanced stability may result from structural rigidity induced by oligomerization, shielding of flexible or loop regions inside a hydrophobic core created from protein-protein interactions, and subsequent protection from protease cleavage. In addition, capsid stability often benefits from hydrophobic effects and buried electrostatic interactions (hydrogen bonds and charge-charge attractive interactions) since stability of viral capsid proteins can be perturbed by single amino acid changes.

The next observation from our studies is that Ile-52 of VP1 is critical for VP2 interaction based on the results that various mutations of this residue abrogate VP1-VP2 interaction. A relevant question is whether Ile-52 makes direct contact with VP2 or the abrogation of VP2 interaction is an indirect effect. Analysis of the capsid structure shows that Ile-52 is surrounded by several hydrophobic residues and thus any mutation at this position has the potential to alter the local structure and result in abrogation of the VP2 interaction. However, our finding that the I52V mutation, which is likely to maintain several of the key contacts, also affects VP2 interaction, and further that the I52A mutation allows formation of the intact shell suggests that Ile-52 directly interacts with VP2. However, the possibility that Ile-52 indirectly affects VP2 interaction cannot be unequivocally eliminated.

The T=3 icosahedral capsid consists of 90 Ile-52 pairs. The lack of any detectable density in the cryo-EM and X-ray structures of caliciviruses suggests that VP2 does not interact with all of the icosahedrally equivalent Ile-52 pairs. Although the precise number of VP2 molecules that are incorporated into caliciviruses is currently unclear, various studies consistently have suggested only a few copies of VP2 per virion. Previous estimates of the numbers of VP2 molecules per particle have ranged from 1.5 to 8 (20, 21, 40). These estimates were derived from comparative quantitation of purified [35S]methionine-radiolabeled NV VLPs or FCV virions using PhosphorImager analysis. The studies on FCV also showed that a low level of VP2 expression relative to VP1 is exquisitely regulated by a termination/reinitiation mechanism from subgenomic RNA and suggested that VP2 expression is linked to particle production (40). Taken together, these observations indicate that VP2 could be involved in initiating capsid assembly and enhancing capsid stability.

Several mechanisms may explain how a substoichiometric proportion of a small minor structural protein plays a role during initiation of capsid assembly. Based on structural and mass spectroscopy studies, it is proposed that capsid assembly in NV and likely in other noroviruses proceeds by the formation of pentamers of VP1 dimers (41, 42). Although we note that it is not necessary for VP2 to interact with all of the dimers in the capsid, VP2 may bind to Ile-52, provide stability to VP1 dimers, and promote nucleation whereby assembly proceeds in a cascade until a fully closed capsid is formed. Furthermore, it is possible that Ile-52 may be part of the crucial center of a hydrophobic patch between VP1 and VP2 that helps to reinforce and direct the curvature of the capsid facilitated by the “bent” conformation of the A/B dimer or may allow an increase in the speed of the curvature formation during viral capsid assembly. This idea is supported by the fact that insect cell-derived VLPs produced in the absence of VP2 are heterogeneous in size, indicating the lack of curvature control (23). Close examination of the capsid interior indicates that the Ile-52 pair is surrounded by a stretch of negatively charged residues. By nonspecifically interacting with this region of the capsid, the highly basic VP2 (with a predicted isoelectric point of ≥ 9.5) may counteract the electrostatic repulsion between the RNA and capsid and help stabilize the encapsidated genome. Further studies are required to analyze the VP2-RNA interactions.

Recently, Subba-Reddy et al. (43) showed that VP1 directly interacts with the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) through its S domain and exhibits a concentration-dependent regulatory activity on RNA translation and RNA synthesis. These studies suggest that after virus entry into cells and capsid disassembly, released VP1 enhances RdRp activity, and the VP1 stimulatory effect continues during the replication cycle concomitant with increased production of VP1. VP1 concentration ultimately reaches a threshold for oligomerization, signaling the gradual reduction in viral replication and the beginning of assembly and genome encapsidation. More interestingly, several regions in the S domain of VP1 are implicated in RdRp interactions and these regions overlap the VP1-VP2 interaction footprint described here in our study. It is tantalizing to speculate that VP2 acts as a molecular switch whereby RdRp interacting with VP1 dictates primarily the replication phase, while VP2 interacting with VP1 promotes oligomerization and stability that results in the initiation of the assembly phase during norovirus replication.

Given that VP2 does not interact with VP1 at all of the icosahedrally equivalent positions, it is indeed challenging to determine precisely how VP2 is oriented inside the capsid. Although several studies had indicated the presence of VP2 in the calicivirus capsid, the location of VP2 in the context of the capsid has been unclear. Our biochemical studies presented here provide novel insights into various aspects of VP1-VP2 interactions with implications in capsid assembly and genome encapsidation. VP2 in caliciviruses exhibits enormous sequence diversity with several large deletions and insertions. Despite secondary structure predictions indicating that VP2 is predominantly α-helical, it is currently unclear whether VP2 possesses any structurally ordered core that is amenable for analysis by structural techniques or if it behaves as an intrinsically disordered protein. Future studies using biochemical and structural techniques are required to address the structural aspects of VP2 along with its possible interactions with RNA. Such studies perhaps culminating in the determination of 3-dimensional structure of VP2 will be enormously useful in further understanding VP2 function. A better understanding of the assembly/disassembly mechanisms could contribute to the development of strategies that aim to disrupt viral capsid formation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by NIH grants T32 AJ07471 (S.V.) and PO1 AI057788 (M.K.E.) and by grant Q1279 (B.V.V.P.) from the Welch Foundation.

We gratefully thank Jae-Mun Choi and Sreejesh Shanker for help with PyMOL and Budi Utama for excellent instructions on EM.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 13 February 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, Tauxe RV, Widdowson MA, Roy SL, Jones JL, Griffin PM. 2011. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—major pathogens. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17:7–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Clarke IN, Estes MK, Green KY, Hansman GS, Knowles NJ, Koopmans MK, Matson DO, Meyers G, Neill JD, Radford A, Smith AW, Studdert MJ, Thiel Vinjé H-JJ. 2012. Caliciviridae, p 977–986 In King AM, Carstens EB, Lefkowitz EJ. (ed), Virus taxonomy: classification and nomenclature of viruses: ninth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier, San Diego, CA [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zheng DP, Ando T, Fankhauser RL, Beard RS, Glass RI, Monroe SS. 2006. Norovirus classification and proposed strain nomenclature. Virology 346:312–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Siebenga JJ, Vennema H, Zheng DP, Vinje J, Lee BE, Pang XL, Ho EC, Lim W, Choudekar A, Broor S, Halperin T, Rasool NB, Hewitt J, Greening GE, Jin M, Duan ZJ, Lucero Y, O'Ryan M, Hoehne M, Schreier E, Ratcliff RM, White PA, Iritani N, Reuter G, Koopmans M. 2009. Norovirus illness is a global problem: emergence and spread of norovirus GII.4 variants, 2001-2007. J. Infect. Dis. 200:802–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lindesmith LC, Donaldson EF, Lobue AD, Cannon JL, Zheng DP, Vinje J, Baric RS. 2008. Mechanisms of GII.4 norovirus persistence in human populations. PLoS Med. 5:e31 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Herbert TP, Brierley I, Brown TD. 1996. Detection of the ORF3 polypeptide of feline calicivirus in infected cells and evidence for its expression from a single, functionally bicistronic, subgenomic mRNA. J. Gen. Virol. 77(Pt 1):123–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Neill JD, Mengeling WL. 1988. Further characterization of the virus-specific RNAs in feline calicivirus infected cells. Virus Res. 11:59–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boga JA, Marin MS, Casais R, Prieto M, Parra F. 1992. In vitro translation of a subgenomic mRNA from purified virions of the Spanish field isolate AST/89 of rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV). Virus Res. 26:33–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Parra F, Boga JA, Marin MS, Casais R. 1993. The amino-terminal sequence of VP60 from rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus supports its putative subgenomic origin. Virus Res. 27:219–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jiang X, Wang M, Wang K, Estes MK. 1993. Sequence and genomic organization of Norwalk virus. Virology 195:51–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jiang X, Wang M, Graham DY, Estes MK. 1992. Expression, self-assembly, and antigenicity of the Norwalk virus capsid protein. J. Virol. 66:6527–6532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Prasad BV, Hardy ME, Dokland T, Bella J, Rossmann MG, Estes MK. 1999. X-ray crystallographic structure of the Norwalk virus capsid. Science 286:287–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Prasad BV, Rothnagel R, Jiang X, Estes MK. 1994. Three-dimensional structure of baculovirus-expressed Norwalk virus capsids. J. Virol. 68:5117–5125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Prasad BV, Matson DO, Smith AW. 1994. Three-dimensional structure of calicivirus. J. Mol. Biol. 240:256–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen R, Neill JD, Estes MK, Prasad BV. 2006. X-ray structure of a native calicivirus: structural insights into antigenic diversity and host specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:8048–8053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Katpally U, Voss NR, Cavazza T, Taube S, Rubin JR, Young VL, Stuckey J, Ward VK, Virgin HW, Wobus CE, Smith TJ. 2010. High-resolution cryo-electron microscopy structures of murine norovirus 1 and rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus reveal marked flexibility in the receptor binding domains. J. Virol. 84:5836–5841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bertolotti-Ciarlet A, White LJ, Chen R, Prasad BV, Estes MK. 2002. Structural requirements for the assembly of Norwalk virus-like particles. J. Virol. 76:4044–4055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hutson AM, Atmar RL, Marcus DM, Estes MK. 2003. Norwalk virus-like particle hemagglutination by binding to H histo-blood group antigens. J. Virol. 77:405–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Choi JM, Hutson AM, Estes MK, Prasad BV. 2008. Atomic resolution structural characterization of recognition of histo-blood group antigens by Norwalk virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:9175–9180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Glass PJ, White LJ, Ball JM, Leparc-Goffart I, Hardy ME, Estes MK. 2000. Norwalk virus open reading frame 3 encodes a minor structural protein. J. Virol. 74:6581–6591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sosnovtsev SV, Green KY. 2000. Identification and genomic mapping of the ORF3 and VPg proteins in feline calicivirus virions. Virology 277:193–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sosnovtsev SV, Belliot G, Chang KO, Onwudiwe O, Green KY. 2005. Feline calicivirus VP2 is essential for the production of infectious virions. J. Virol. 79:4012–4024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bertolotti-Ciarlet A, Crawford SE, Hutson AM, Estes MK. 2003. The 3′ end of Norwalk virus mRNA contains determinants that regulate the expression and stability of the viral capsid protein VP1: a novel function for the VP2 protein. J. Virol. 77:11603–11615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Prasad BV, Hardy ME, Estes MK. 2000. Structural studies of recombinant Norwalk capsids. J. Infect. Dis. 181(Suppl 2):S317–S321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen R, Neill JD, Prasad BV. 2003. Crystallization and preliminary crystallographic analysis of San Miguel sea lion virus: an animal calicivirus. J. Struct. Biol. 141:143–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ossiboff RJ, Zhou Y, Lightfoot PJ, Prasad BV, Parker JS. 2010. Conformational changes in the capsid of a calicivirus upon interaction with its functional receptor. J. Virol. 84:5550–5564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cathomen T, Buchholz CJ, Spielhofer P, Cattaneo R. 1995. Preferential initiation at the second AUG of the measles virus F mRNA: a role for the long untranslated region. Virology 214:628–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kozak M. 1987. An analysis of 5′-noncoding sequences from 699 vertebrate messenger RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 15:8125–8148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hardy ME, Tanaka TN, Kitamoto N, White LJ, Ball JM, Jiang X, Estes MK. 1996. Antigenic mapping of the recombinant Norwalk virus capsid protein using monoclonal antibodies. Virology 217:252–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. White LJ, Ball JM, Hardy ME, Tanaka TN, Kitamoto N, Estes MK. 1996. Attachment and entry of recombinant Norwalk virus capsids to cultured human and animal cell lines. J. Virol. 70:6589–6597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Parker TD, Kitamoto N, Tanaka T, Hutson AM, Estes MK. 2005. Identification of genogroup I and genogroup II broadly reactive epitopes on the norovirus capsid. J. Virol. 79:7402–7409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chen R, Neill JD, Noel JS, Hutson AM, Glass RI, Estes MK, Prasad BV. 2004. Inter- and intragenus structural variations in caliciviruses and their functional implications. J. Virol. 78:6469–6479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Glass PJ, Zeng CQ, Estes MK. 2003. Two nonoverlapping domains on the Norwalk virus open reading frame 3 (ORF3) protein are involved in the formation of the phosphorylated 35k protein and in ORF3-capsid protein interactions. J. Virol. 77:3569–3577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Asanaka M, Atmar RL, Ruvolo V, Crawford SE, Neill FH, Estes MK. 2005. Replication and packaging of Norwalk virus RNA in cultured mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:10327–10332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jiang X, Graham DY, Wang KN, Estes MK. 1990. Norwalk virus genome cloning and characterization. Science 250:1580–1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kapikian AZ, Gerin JL, Wyatt RG, Thornhill TS, Chanock RM. 1973. Density in cesium chloride of the 27 nm “8FIIa” particle associated with acute infectious nonbacterial gastroenteritis: determination by ultra-centrifugation and immune electron microscopy. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 142:874–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Baric RS, Yount B, Lindesmith L, Harrington PR, Greene SR, Tseng FC, Davis N, Johnston RE, Klapper DG, Moe CL. 2002. Expression and self-assembly of Norwalk virus capsid protein from Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus replicons. J. Virol. 76:3023–3030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fisher AJ, Johnson JE. 1993. Ordered duplex RNA controls capsid architecture in an icosahedral animal virus. Nature 361:176–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Reade R, Kakani K, Rochon D. 2010. A highly basic KGKKGK sequence in the RNA-binding domain of the cucumber necrosis virus coat protein is associated with encapsidation of full-length CNV RNA during infection. Virology 403:181–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Luttermann C, Meyers G. 2007. A bipartite sequence motif induces translation reinitiation in feline calicivirus RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 282:7056–7065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Prasad BV, Hardy ME, Jiang X, Estes MK. 1996. Structure of Norwalk virus. Arch. Virol. 1996(Suppl 12):237–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shoemaker GK, van Duijn E, Crawford SE, Uetrecht C, Baclayon M, Roos WH, Wuite GJ, Estes MK, Prasad BV, Heck AJ. 2010. Norwalk virus assembly and stability monitored by mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 9:1742–1751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Subba-Reddy CV, Yunus MA, Goodfellow IG, Kao CC. 2012. Norovirus RNA synthesis is modulated by an interaction between the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and the major capsid protein, VP1. J. Virol. 86:10138–10149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]