Abstract

Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) is an emerging RNA virus with devastating economic and social consequences. Clinically, RVFV induces a gamut of symptoms ranging from febrile illness to retinitis, hepatic necrosis, hemorrhagic fever, and death. It is known that type I interferon (IFN) responses can be protective against severe pathology; however, it is unknown which innate immune receptor pathways are crucial for mounting this response. Using both in vitro assays and in vivo mucosal mouse challenge, we demonstrate here that RNA helicases are critical for IFN production by immune cells and that signaling through the helicase adaptor molecule MAVS (mitochondrial antiviral signaling) is protective against mortality and more subtle pathology during RVFV infection. In addition, we demonstrate that Toll-like-receptor-mediated signaling is not involved in IFN production, further emphasizing the importance of the RNA cellular helicases in type I IFN responses to RVFV.

INTRODUCTION

Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) is a negative-strand RNA virus of the genus Phlebovirus (family Bunyaviridae) (1). Recurrent outbreaks of Rift Valley fever virus have been documented throughout Africa, with first reports in Kenya in 1930 (2). Recently, the virus was established outside of continental Africa in Madagascar (3) and the Arabian Peninsula (4). RVFV is virulent in young livestock and induces spontaneous abortion in pregnant animals. In humans, infection results in febrile illness and a subset of patients experience retinitis, hepatitis, encephalitis, hemorrhagic fever, or death. High case fatality rates were reported for the 2006-2008 outbreaks in several countries for patients presenting with severe symptoms suggestive of RVFV (5).

Although it is unknown which host factors determine whether an RVFV-infected patient experiences mild or severe disease manifestations, it is known that type I interferon (IFN) responses can be protective. Administration of the type I IFN inducer poly(I·C) stabilized with polylysine and carboxymethyl cellulose was shown to protect rodents from mortality associated with RVFV infection (6). More directly, type I IFN has been shown to guard against pathology when recombinant or human-derived alpha IFN (IFN-α) was administered to rhesus macaques prior to, or shortly after, challenge with virulent RVFV (7). In addition, mice lacking type I IFN receptor (IFNAR) were more susceptible to clinical isolate and lab-attenuated strains of RVFV than wild-type (WT) mice (8).

The innate immune receptors that recognize RVFV and induce a signaling cascade leading to type I IFN production have not been well characterized. Major classes of innate pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) include C-type lectin receptors (CLRs), Toll-like receptors (TLRs), Nod-like receptors (NLRs), and retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLRs), also known as cellular RNA helicases. These classic PRRs recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and initiate signaling that can lead to an inflammatory or viral replication-interfering state within the host (9). Transmembrane-bound CLRs recognize carbohydrate patterns and can be utilized for viral entry or can regulate IFN responses during viral infection (10–12). The NLR family includes more than 20 proteins in humans. Recent work has demonstrated that NLR member NOD2 is capable of recognizing single-strand RNA (ssRNA) viral genomes and can initiate IFN signaling through the adaptor molecule MAVS (mitochondrial antiviral signaling; also known as IFN promoter stimulator 1 [IPS-1], CARD adaptor-inducing IFN-β [Cardif], and virus-induced signaling adaptor [VISA]) (13). In addition, many inflammasomes can be activated by viral nucleic acid (14–17).

Endosomal TLRs (TLR3, TLR7/8, TLR9) recognize nucleic acids and target recognition of intracellular pathogens, such as viruses (9). TLR3 recognizes viral genomic double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) or replication intermediates and the synthetic dsRNA ligand poly(I·C) (9). TLR7 and human TLR8 recognize viral ssRNA (18). In contrast, murine TLR8 does not recognize ssRNA motifs and was originally thought to be nonfunctional; however, subsequent work has shown that stimulation of murine TLR8 and downstream NF-κB activation can be achieved with immune response modifiers used in combination with poly(T) oligodeoxynucleotide (19). The potential role for TLR8 recognition of vaccinia virus and its DNA genome is under debate (20, 21). Because RVFV is a negative sense ssRNA virus, TLR3, TLR7, or TLR8 could likely contribute to recognition and antiviral signaling.

Intracellular cytoplasmic DExD/H box helicase family members, including RIG-I, melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5), and Laboratory of Genetics and Physiology 2 (LGP2) (22), can also sense viral PAMPs. RIG-I recognizes shorter blunt-end dsRNA intermediates (23) with a 5′-triphosphate moiety (24) that are detected during viral replication of negative strand RNA viruses. MDA5 induces IFN-β production in response to the synthetic dsRNA ligand poly(I·C) and to picornaviruses (25). It was generally assumed that MDA5 recognized longer dsRNA intermediates, although further analysis suggests that more complex structures, such as branched RNA, may be needed to initiate responses (26). Both RIG-I and MDA5 have two caspase activation and recruitment domains (CARD) (27) and signal through the adaptor molecule MAVS to induce NF-κB and IFN signaling (28). Although LGP2 lacks a CARD signaling motif, it has been shown to be required for RIG-I and MDA5 antiviral signaling (29) in contrast to a previous report suggesting that it may have function as a negative regulator (30).

Previous studies using RVFV clone 13 (a naturally attenuated strain lacking most of the NSs gene) demonstrated that short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting RIG-I abrogated IFN-β promoter activation in HEK (human embryonic kidney) 293T cells in response to isolated RVFV RNA, whereas shRNA targeting of MDA5 did not hinder IFN responses (31). In addition, treatment of isolated clone 13 RNA with shrimp alkaline phosphatase greatly reduced IFN-β stimulation (31), suggesting that the 5′-triphosphate moiety was responsible for activation through RIG-I. These studies were an important first look into innate recognition of RVFV; however, interpretation of these studies is limited as HEK cells lack expression of TLR family members that potentially could contribute to antiviral responses (32–34). It is likely that innate immune cells, such as dendritic cells and macrophages, will be the major sources of IFN during active RVFV infection, and these cells could potentially recognize and respond to RVFV using different receptor pathways than nonimmune cells. In the present study, we investigated the role of RLR and TLR signaling in the induction of IFN responses to RVFV, and the role that these innate pathways play in protection from mucosal challenge with RVFV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Mice deficient in TLR3, MyD88, and TRIF were generated by Shizuo Akira (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan). RIG-I knockout mice were provided by Michael Gale, Jr. (University of Washington). MDA5-deficient mice were provided by Marco Colonna (Washington University). MAVS-deficient mice were generated by Zhijian Chen (University of Texas Southwestern). Wild-type controls from the same generation were used in MAVS animal experiments, since this mouse strain is not fully backcrossed onto C57BL/6. Mice were maintained in filter-top microisolator cages in ventilated racks. Animal experiments were carried out under conditions approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Case Western Reserve University and Saint Louis University.

Cells, viruses, and reagents.

Attenuated RVFV strains rMP-12 and NSs del were a gift from Shinji Makino (University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX). RVFV rMP-12 strain (recovered from cells using reverse genetics and containing a XhoI site) was derived from the MP-12 strain, initially made by passaging patient isolate ZH548 12 times in the presence of 5-fluorouracil (35). The NSs del strain was derived from rMP-12 and lacks virulence factor NSs (36). These samples were handled under biosafety level 2 conditions unless previously inactivated. Samples containing virus were inactivated by cross-linking RNA with 2 J of UV light (Stratagene).

Immune cells were derived from the bone marrow of wild-type and knockout mice using standard protocols (37, 38). For generation of conventional dendritic cells (cDCs), bone marrow was isolated from femurs and tibias and was cultured in DC media composed of RPMI 1640 media with l-glutamine, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals), 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM penicillin-streptomycin, and 1/30 total volume addition of J558L supernatant that contains granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (39). Cells were supplemented on days 3 and 6 with a half volume of fresh medium and J558L supernatant. Semiadherent cells were harvested between days 8 to 10. More than 80% of the cDC population was CD11b+ and CD11c+ as determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis. To generate mixed plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) and cDCs, DC media was used with the addition of 1 μg of FLT-3 ligand fusion protein (Bioexpress)/ml. Cells were fed on days 3 and 6 and were collected for use between days 8 to 10. The percent pDC/cDC populations were evaluated by FACS analysis. Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were generated by culturing total bone marrow in high glucose Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 mM penicillin-streptomycin, 10 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM HEPES, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, with 20% L929 cell conditioned supernatant containing macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF). Cells were cultured for 5 days, after which the media and nonadherent cells were removed, and fresh media were added every other day until harvest between days 7 and 10. Typically, BMDMs were >95% positive for CD11b and F4/80 as determined by FACS analysis. Differentiated cells were counted, plated, and stimulated at 105 cells in 200 μl (total volume) per well in a 96-well plate. For infection studies with multiple MOI of virus, cells were stimulated with media only control, poly(I·C) (Imgenex), Pam3Cysk4 (InvivoGen), 5′ triphosphate RNA (InvivoGen), Gardiquimod (InvivoGen), R848 (InvivoGen), Sendai virus (Charles River Laboratories), or Rift Valley fever virus for 24 h. Combined supernatant and lysate samples were harvested for further analysis via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and plaque assay unless otherwise designated. For time course studies of IFN-α and viral production, cells were stimulated with RVFV NSs del at multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 for 2 h to allow for adsorption, after which the inoculum was removed and replaced with medium. Supernatant was harvested at 6, 12, and 24 h, and IFN-α levels were determined by ELISA. The viral load in the supernatant was determined via plaque assay.

FACS analysis of cell surface markers.

The purity of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells and macrophages was confirmed with flow cytometry. J558L-derived cDCs and FLT3L-derived mixed pDCs/cDCs were stained with fluorochrome-linked antibodies for CD11c and CD11b (eBioscience). The purity of macrophages was confirmed with F4/80 and CD11b antibodies (eBioscience). Cells were incubated on ice for 15 min with FBS to block Fc receptors and then with primary antibodies for 30 min on ice. Cells were fixed in 2% formaldehyde and were analyzed using a BD LSRII flow cytometer and FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc.).

Stimulation of transfected cell lines.

HEK293XL cell lines stably expressing TLR7 and TLR8 were purchased from InvivoGen. A total of 40,000 cells were plated per well in a 96-well plate and transfected several hours later using PolyJet (Signagen). HEK293XL cells and HEK293XL cells stably transfected with TLR7 or TLR8 were transiently transfected with a luciferase reporter plasmid for IFN-β (promoter region) or NF-κB and constitutively active Renilla. The dominant-negative constructs RIG-I Dn (RIG-I helicase domain) and MyD88 Dn (TIR domain only) were transfected at the quantities described previously (30, 40). The total DNA in each well was adjusted to 140 ng with pcDNA 3.1. The cells were stimulated with media, RVFV, or control ligands Sendai (SV), Gardiquimod (InvivoGen), R848 (InvivoGen), or 400 ng of poly(I·C) (Amersham) transfected into cells with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol for 18 h. Luminescence was assessed using a Promega Glomax 96 microplate luminometer. Luciferase values were normalized to Renilla and a medium-only control.

Western blotting.

For Western blot analysis, 106 HEK293XL cells were transfected using the following conditions: (i) untransfected cells, (ii) pcDNA3.1, Renilla, and IFN-β reporter plasmid, (iii) Renilla, IFN-β reporter, and dominant-negative construct, or (iv) dominant-negative construct alone. The total amounts of DNA per transfection condition were equal. Cell lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer with 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific). Samples were boiled for 5 min in Laemmli buffer. Protein samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE using 4% bisacrylamide stacking and 15% bisacrylamide resolving gels. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane and were blotted with anti-Flag (Sigma) or anti-AU-1 (Novus) in 4% nonfat dried milk. Blots were stripped with Western blot stripping buffer (Thermo Scientific) and were reprobed with anti-β-actin antibody A-15 (Santa Cruz).

Experimental infection of mice.

For subcutaneous and intranasal challenges of mice, the animals were infected with 3.5 × 103 or 3.5 × 104 PFU of RVFV rMP-12. Intranasal challenges were performed by administering 10 μl of virus into the noses of anesthetized animals. Mortality was recorded throughout the experiment. Surviving mice were weighed daily (to 21 days), and all experiments were terminated on day 28.

To assess cytokine production, liver damage, and viral load throughout infection, a separate study was conducted in which mice were randomized based on sex and sacrificed on days 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 after intranasal infections or when humane sacrifice was deemed necessary. At the time of death, blood was collected using cardiac puncture, and serum was isolated and used for assays. Livers and lungs were harvested and homogenized in a 10% (wt/vol) solution of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Cytokine responses.

A cell-free sample from 105 cells per well was harvested and inactivated, and the cytokine levels were assessed using ELISA. Sandwich ELISA for murine IFN-α was performed as previously described (41). Serum samples from WT and knockout (KO) mice were analyzed for 32 cytokines simultaneously using a Milliplex array (Millipore). The following cytokines and chemokines were measured: Eotaxin (CCL11), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), GM-CSF, IFN-γ, interleukin-1α (IL-1α), IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12p40, IL-12p70, IL-13, IL-15, IL-17, IFN-γ-inducible protein (IP)-10 (CXCL10), keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC/CXCL1), LIF, lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced chemokine (LIX/CXCL5), MCP-1 (CCL2), M-CSF, mitogen-inducible gene (MIG/CXCL9), MIP-1α (CCL3), MIP-1β (CCL4), MIP-2 (CXCL2), RANTES (CCL5), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Samples that were out of range for LPS-induced chemokine (LIX/CXCL5) from multiplex analysis were determined by ELISA (R&D).

Plaque assay.

Vero E6 cells were plated in 6- or 12-well plates 1 day prior to infection. Viral dilutions were prepared in 1× αMEM (Sigma Chemicals) with sodium bicarbonate and 2% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals). After 1 h of adsorption, viral dilutions were carefully removed and replaced with a 1:1 dilution of 1% agarose (Promega) and 2× αMEM with 4% FBS. Infected cells were incubated for 3 days at 37°C, fixed with 10% formaldehyde in PBS, and stained with 1% crystal violet–20% ethanol solution. The plaques were counted, and the titer of the original sample was determined.

Liver function test.

Sera from WT and KO mice were assessed for alanine transaminase (ALT) levels for each mouse on the day of harvest using a color endpoint assay (Xpress Bio Life Science Products).

NanoString gene expression analysis.

BMDMs or cDCs were plated at 106 cells per well in six-well plates and then mock infected or infected with rMP-12 or NSs del at MOIs of 1, 2, or 5 as indicated. Total RNA was isolated at 6 h postinfection using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). A total of 100 ng of total RNA was hybridized to a custom mouse gene expression CodeSet (consisting of a panel of inflammatory cytokines and IFN-stimulated genes [ISGs]) and analyzed on an nCounter digital analyzer (NanoString Technologies). Counts were normalized to internal spike-in and endogenous housekeeping controls. The results from the NanoString experiment were normalized according to the manufacturer's protocol. A pseudocount was added to all values, such that the smallest value in the data set was equal to 1. All values were log transformed and, in the case of data obtained with cDCs, a heat map was generated using the ggplot package within the open source R software environment.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed using commercial software (GraphPad). ELISA and cultured macrophage and DC virus load were analyzed using a Student independent t test. Cytokine levels were assessed by multiplex and ALT levels were analyzed by using a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. Comparison of survival curves was performed using a log-rank test. P values are presented when statistical significance was observed (significance was set at P ≤ 0.05).

RESULTS

RVFV-induced activation of IFN-β is dependent on RIG-I.

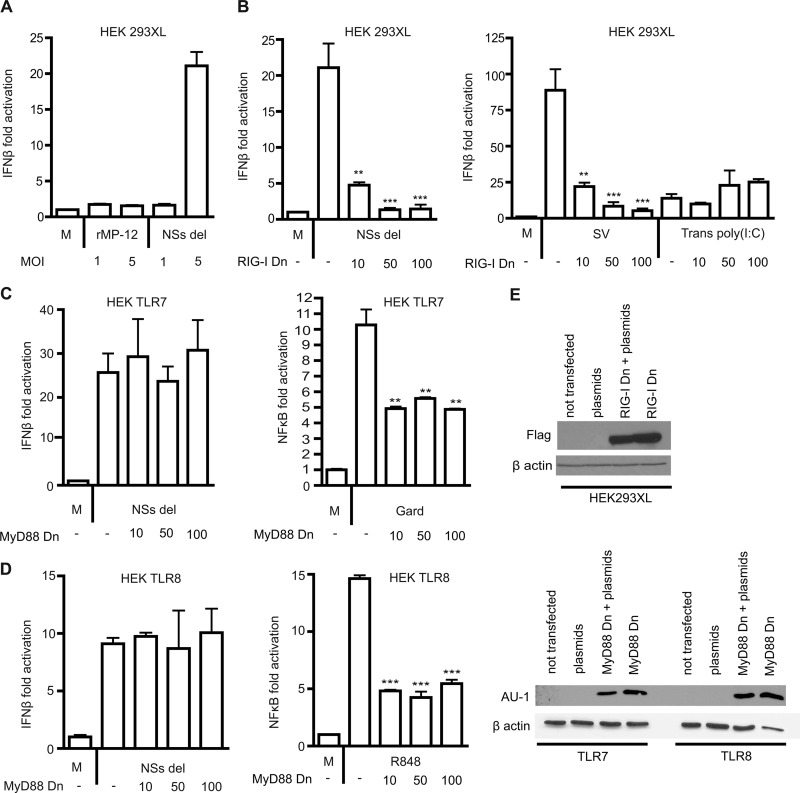

Previously, isolated RVFV RNA was shown to activate an IFN-β promoter in HEK293T cells and was dependent on RIG-I and not on MDA5 (31). To confirm whether whole RVFV particles can activate the IFN-β promoter during the course of infection, HEK293XL cells (transfected with a luciferase reporter construct for IFN-β) were stimulated with rMP-12 and NSs del strains at MOIs of 1 and 5. We observed negligible activation of the IFN-β luciferase reporter by rMP-12, in contrast to the NSs del strain, which produced strong induction of the IFN-β reporter (Fig. 1A). This was not unexpected, since rMP-12 expresses the virulence factor NSs which has been shown by others to specifically inhibit IFN-β transcription (42). To determine whether activation was RIG-I specific, HEK293XL cells were transiently cotransfected with the IFN-β reporter and increasing concentrations of an inhibitory plasmid RIG-I Dn (helicase domain only). We show that inhibition of RIG-I resulted in a dose dependent reduction in IFN-β activation after stimulation with NSs del. This effect was specific, since MDA5-driven IFN-β activation by transfected poly(I·C) was not affected by the addition of the RIG-I dominant-negative construct, whereas RIG-I-mediated IFN-β activation by Sendai virus was reduced (Fig. 1B) (43). Expression of the RIG-I Dn construct was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 1E).

Fig 1.

RVFV-induced IFN-β responses are dependent on cytoplasmic RIG-I and are independent of TLRs. (A) HEK293XL cells were transfected with a luciferase construct for the IFN-β promoter and stimulated with medium only (M) or RVFV rMP-12 or NSs del strains at an MOI of 1 or 5 for 18 h. (B) IFN-β activation in HEK293XL cells transfected with 0, 10, 50, or 100 ng of RIG-I dominant-negative construct (RIG-I Dn) and stimulated with medium (M) or NSs del at an MOI of 5 for 18 h. Cells were stimulated with control ligands Sendai virus (SV) and 400 ng of transfected poly(I·C) [Trans poly(I:C)] for 18 h with or without the addition of RIG-I dominant-negative construct. (C and D) HEK293XL cells were stably transfected with TLR7 (C) or TLR8 (D) and transiently transfected with MyD88 dominant-negative construct (MyD88 Dn) at 0, 10, 50, or 100 ng. The cells were transfected with IFN-β reporter construct and stimulated with medium (M) or NSs del strain at an MOI of 5. Controls were performed using the NF-κB luciferase reporter and the TLR7-specific ligand Gardiquimod (C) or the TLR7/8 ligand R848 (D) for 18 h. The data represent mean values ± the standard deviations based on triplicate wells from a representative experiment. Each experiment was performed at least three times. Significance: ***, P ≤ 0.001; **, P ≤ 0.01. (E) Western blot confirming the expression of RIG-I Dn in HEK293XL cells and of MyD88 Dn in TLR7 and TLR8 cells. The cells were either (i) not transfected, (ii) transfected with IFN-β luciferase reporter, Renilla, and pcDNA 3.1 (plasmids), (iii) transfected with the dominant-negative construct, reporter, and Renilla (MyD88 Dn + plasmids), or (iv) the dominant-negative construct alone (MyD88 Dn).

RVFV-induced activation of IFN-β is independent of endosomal TLRs.

In order to determine whether TLRs contribute to type I IFN promoter activation and production in response to RVFV, HEK293XL cells stably overexpressing TLR7 or TLR8 were transfected with the IFN-β luciferase reporter and then infected with rMP12 or NSs del strains. As observed in HEK293XL null cells (i.e., not transfected with TLRs), rMP-12 did not induce IFN-β promoter activation (data not shown). The NSs del strain induced IFN-β promoter activation in TLR7 (Fig. 1C) and TLR8 (Fig. 1D) infected cells, but at a similar level to the HEK293XL null cells. MyD88 is an adaptor molecule that can be utilized by all TLRs except for TLR3 during signaling (9). Activation of the IFN-β reporter was not affected by the addition of dominant-negative mutant MyD88 Dn (TIR domain only), suggesting that TLR7 and -8 do not contribute to IFN-β promoter activation by RVFV. As a control, the overexpression of MyD88 Dn did reduce the activation by Gardiquimod in TLR7 cells (Fig. 1C) and by R848 in TLR8 cells (Fig. 1D). The expression of the MyD88 Dn construct was demonstrated by Western blotting (Fig. 1E).

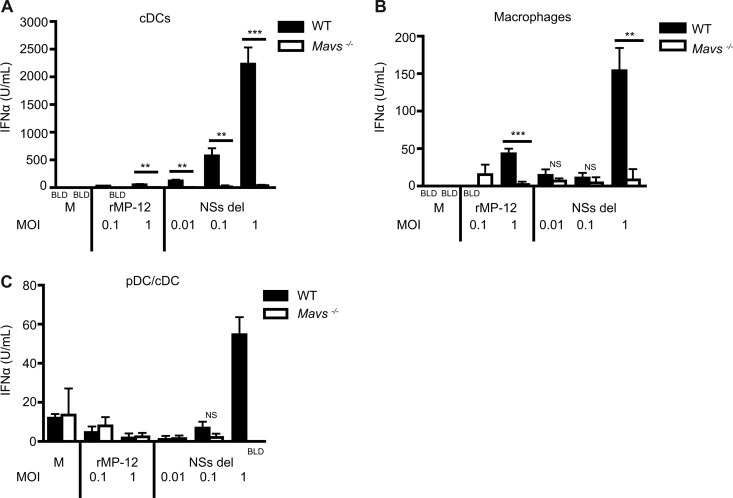

Induction of type I IFN is dependent on MAVS signaling in primary immune cells.

Data from our transfection studies suggest that RIG-I is an important mediator of type I IFN production in response to infectious RVFV. In order to determine which innate immune receptors contribute to type I IFN production in primary immune cells, bone marrow cells from WT mice and mice lacking specific innate immune receptor and adaptor proteins were differentiated into macrophages, cDCs, or FLT3L-derived mixed pDCs/cDCs. Cells were stimulated with RVFV strains rMP-12 and NSs del at a range of MOIs for 24 h. The absence of MAVS (common adaptor for RIG-I and MDA5) led to a significant reduction in RVFV-induced type I IFN production by cDCs (Fig. 2A) and macrophages (Fig. 2B). This decrease was most notable in response to NSs del strain but could also be observed with rMP-12 strain. The absence of MAVS signaling also reduced IFN-α levels to below the level of detection when mixed pDCs/cDCs were stimulated with NSs del at an MOI of 1 (Fig. 2C).

Fig 2.

IFN production in primary immune cells challenged with RVFV is dependent on MAVS. The dependence of type I IFN production on innate adaptor molecule MAVS was assessed in cDCs (A), macrophages (B), and FLT3L-derived mixed pDCs and cDCs (C). IFN-α levels were determined via ELISA from cell samples harvested at 24 h. The data represent mean values ± the standard deviations based on triplicate wells from a representative experiment. Each experiment was performed at least three times. Significance: ***, P ≤ 0.001; **, P ≤ 0.01; not significant (NS), P > 0.05. BLD, below the limit of detection.

Although most of the type I IFN response was dependent on RNA helicase signaling, this did not exclude the possibility that TLRs could contribute to minor amounts of IFN in response to RVFV. The role of MyD88 was assessed in cDCs and macrophages using cells derived from Myd88−/− mice that were stimulated with virus for 24 h. The absence of MyD88 did not impact robust type I IFN production in cDCs (Fig. 3A) or in macrophages (Fig. 3B) in response to RVFV rMP-12 or NSs del.

Fig 3.

IFN-α production not dependent on TLRs. The impact of TLR adaptor molecules MyD88 (A and B) and TRIF (C and D) or of TLR3 (E and F) on type I IFN production was determined in cDCs and macrophages. The IFN-α levels were determined via ELISA from a cell sample harvested at 24 h. The data represent mean values ± the standard deviations based on triplicate wells from a representative experiment. Each experiment was performed at least three times. NS (not significant), P > 0.05. BLD, below the limit of detection.

TLR3 can recognize dsRNA intermediates from viral replication and signal through adaptor molecule TRIF to lead to type I IFN production (18, 44). Recent evidence suggests that the amount of dsRNA intermediates generated by negative-strand RNA viruses is negligible compared to the dsRNA intermediates produced during positive-strand RNA viral replication (45). In addition, TRIF or MyD88 can serve as an adaptor for TLR4 signaling (18). TLR4 has been shown to be involved in the recognition of viral glycoproteins (46–48). BMDMs and cDCs were generated from TLR3 and corresponding adaptor TRIF-deficient mice and were infected with RVFV rMP-12 and NSs del for 24 h. Neither the adaptor molecule TRIF nor the TLR3 contributed significantly to type I IFN production in cDCs (Fig. 3C and E) or macrophages (Fig. 3D and F). These studies demonstrate that RVFV-induced type I IFN production is primarily dependent on RNA helicase adaptor MAVS in immune cells and that TLR signaling does not contribute to type I IFN responses.

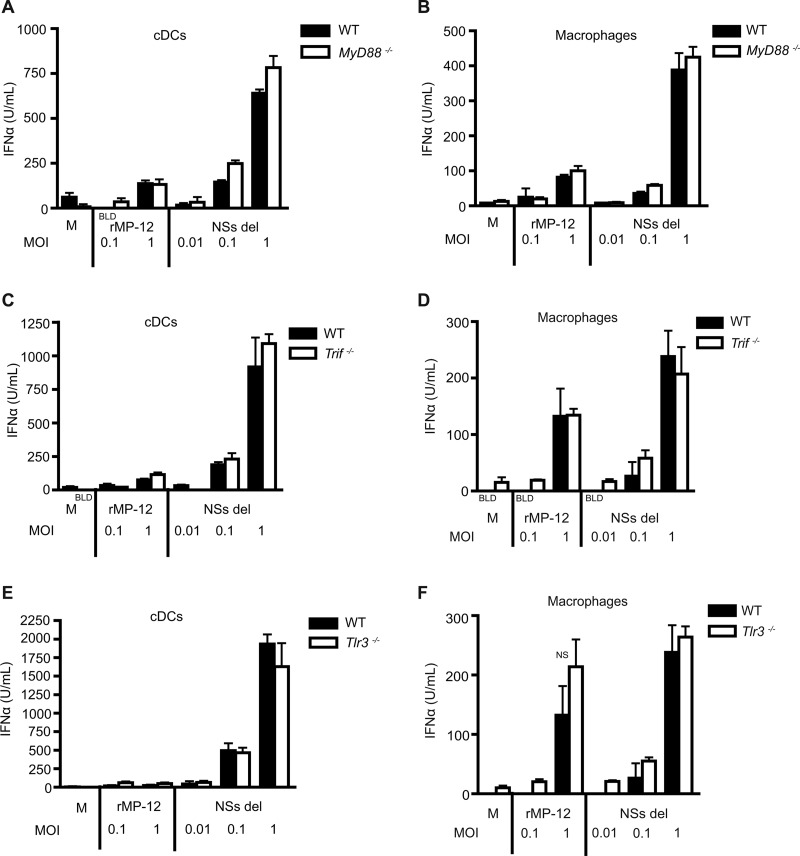

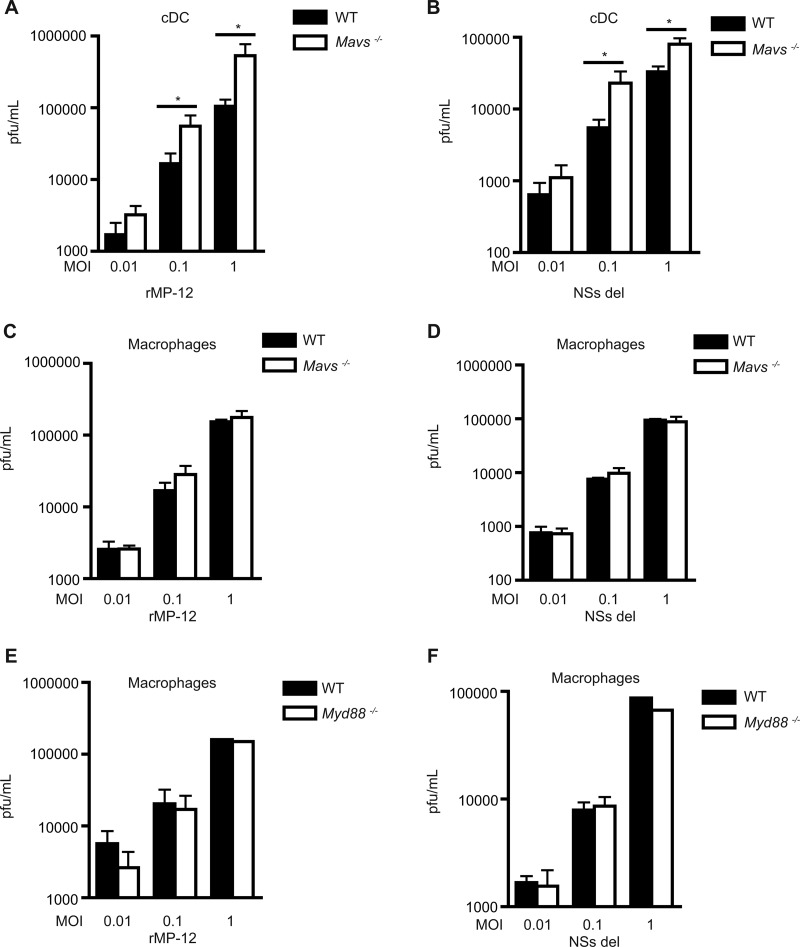

The absence of MAVS results in increased viral load in cDCs.

We hypothesized that RVFV-infected cells lacking robust type I IFN responses would have an increased viral burden compared to cells with competent IFN production. The total viral load (from supernatant and lysate) was assessed in WT and Mavs−/− macrophages or cDCs by using a plaque assay after 24 h of infection. As expected, in correlation with reduced IFN responses after infection, cDCs from Mavs−/− mice showed a significantly increased viral burden when infected with RVFV rMP-12 (Fig. 4A) or NSs del (Fig. 4B) compared to cDCs derived from WT mice. Interestingly, macrophages from Mavs−/− mice did not show a significant difference in viral load after infection with either RVFV rMP-12 (Fig. 4C) or NSs del (Fig. 4D) compared to WT cells. Macrophages derived from Myd88−/− mice also did not have a significant difference in total viral load of rMP-12 or NSs del compared to WT (Fig. 4E and F).

Fig 4.

MAVS-dependent signaling controls viral load in cDCs. Bone marrow-derived cDCs and macrophages from WT and Mavs−/− mice were infected with rMP-12 (A, C, and E) and NSs del (B, D, and F) at various MOIs. The total viral load was determined by plaque assay after 24 h of infection in cDCs (A and B) and macrophages (C, D, E, and F). (A to D) The data represent mean values ± the standard deviations based on triplicate wells from a representative experiment. Each experiment was performed at least three times. (E and F) The mean PFU is shown for an MOI of 1. The mean PFU ± the standard deviation is shown for MOIs of 0.01 and 0.1 (n = 2). Significance: *, P ≤ 0.05.

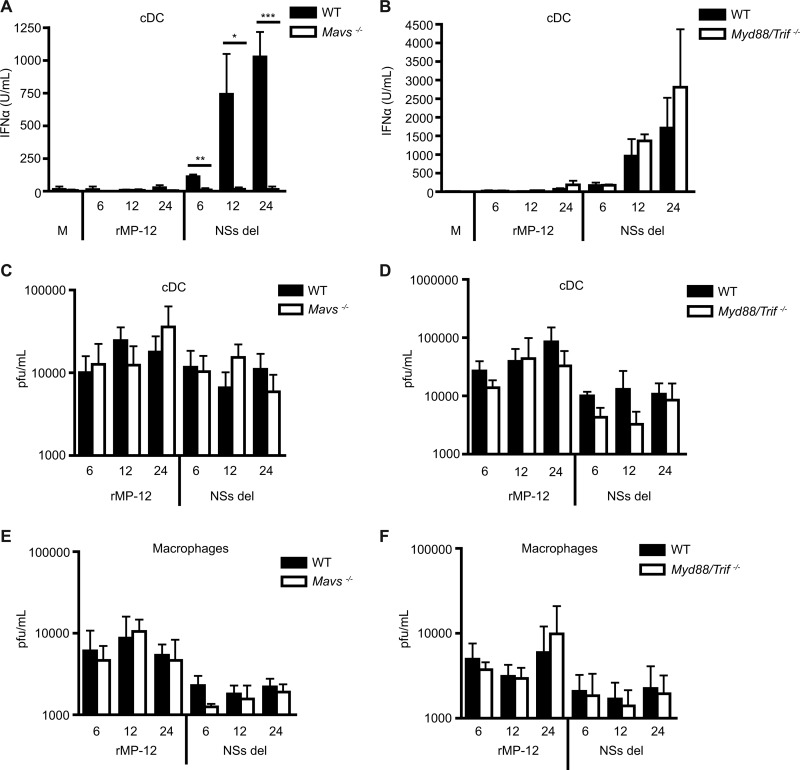

Although our findings show that MAVS is crucial for type I IFN response to RVFV at 24 h, we sought to determine whether other receptors, including TLRs, could have an impact on IFN production earlier during infection. cDCs were generated from WT and Mavs−/− or Myd88/Trif−/− mice (lacking all TLR signaling) and were stimulated with rMP-12 and NSs del at an MOI of 1. IFN responses were assessed at 6, 12, or 24 h. A significant decrease in IFN-α production in response to NSs del virus by cDCs from Mavs−/− compared to WT mice was detected at all of the measured time points (Fig. 5A). The absence of TLR signaling in cDCs did not impact IFN-α production at early or late time points in response to rMP-12 (when detectable) or NSs del compared to WT cells (Fig. 5B). We examined the degree to which cDCs and macrophages could amplify RVFV over time. Cells were infected with rMP-12 or NSs del at an MOI of 1, and virus was removed after 2 h of adsorption to ensure viral load measured in the supernatant at early time points was due to productive infection versus lack of entry. Supernatants were collected after 6, 12, or 24 h of infection, and the virus titers were determined. Viral release was minimal in cDCs and macrophages, with no detectable difference between WT and Mavs−/− (Fig. 5C and E) or Myd88/Trif−/− cDCs and macrophages (Fig. 5D and F).

Fig 5.

Time course of IFN responses to RVFV. Bone marrow-derived cDCs or macrophages from wild-type mice or MAVS- or MyD88/TRIF-deficient mice were infected with rMP-12 or NSs del at an MOI of 1 for 6, 12, or 24 h. The IFN-α responses of cDCs from wild-type mice (A and B) MAVS (A)- or MyD88/TRIF (B)-deficient mice were measured by ELISA. The virus titer was determined in supernatant collected from infected cDCs (C and D) or macrophages (E and F) by plaque assay. The mean levels of IFN-α ± the standard deviations from three experiments are shown. Significance: ***, P ≤ 0.001; **, P ≤ 0.01; *, P ≤ 0.05.

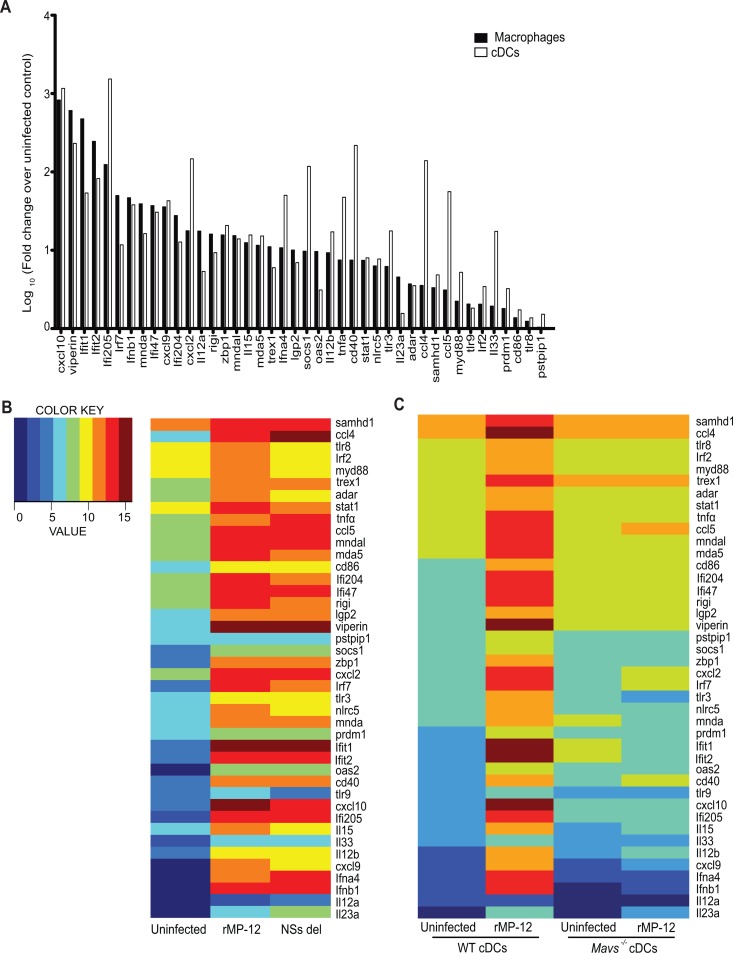

Having established that MAVS is a central regulator of the type I IFN response to RVFV infection in macrophages and cDCs, we next used a multiplex gene expression analysis platform (Nanostring nCounter) to examine the role of MAVS in transcriptional regulation of a panel of type I IFN-inducible genes in RVFV-infected cells. BMDMs and cDCs from WT mice infected with the rMP-12 strain showed upregulated expression of a panel of 42 genes that included Ifnb, Ifna4, and IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) such as Adar (adenosine deaminase, RNA-specific), Ddx58 (RIG-I), Dhx58 (Lgp2), Rsad2 (Viperin), Stat1, Mndal (myeloid nuclear differentiation antigen-like), and Ifi204 (Fig. 6A). Gene expression profiles in WT cDCs were compared after infection with rMP-12 or NSs del virus and were normalized to mock-infected controls. Gene expression in cDCs showed similar patterns of regulation in cells infected with either viral strain (Fig. 6B). We also assessed the requirement for RNA helicase signaling by comparing gene expression between WT and Mavs−/− cells (Fig. 6C). In most cases, the induction of these genes in response to RVFV was dependent on MAVS. These observations suggest that MAVS is a central regulator of the transcriptional response to RVFV infection in DCs.

Fig 6.

MAVS-dependent gene expression induced by RVFV. (A) Multiplexed NanoString analysis was performed on BMDMs and cDCs 6 h after infection with rMP-12 at an MOI of 1. The data are shown as the log10 fold change in infected cells compared to uninfected cells. (B) Normalized mRNA levels for a panel of innate genes in WT cDCs infected for 6 h with rMP-12 or NSs del at an MOI of 2. (C) Innate gene responses of WT and Mavs−/− cDCs 6 h after infection with rMP-12 at an MOI of 5. The data are shown as log-transformed normalized counts.

MAVS is protective against mucosal challenge with RVFV in mice.

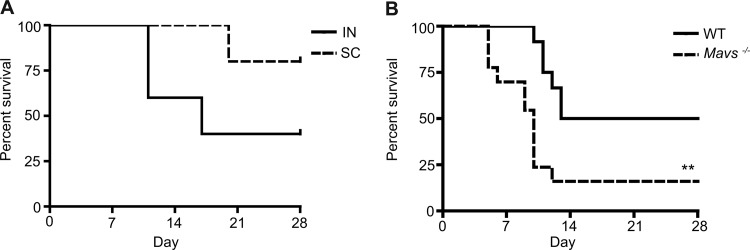

RVFV can infect humans and animals in a natural setting through multiple mechanisms, such as bites from mosquitoes harboring the virus or through mucosal exposure to aerosols and droplets (49). Infectious droplet and/or aerosol exposure can occur during the slaughter or processing of infected livestock or the handling of aborted fetuses when pregnant animals become infected (49). In order to compare the impact of route of infection on mortality, mice were challenged either intranasally or subcutaneously to mimic these natural routes of exposure. C57BL/6 mice (7 to 9 weeks of age) were infected via subcutaneous injection or intranasal droplet with different doses of rMP-12. All mice infected via either route with 3.5 × 103 PFU of virus survived challenge. Mice infected with 3.5 × 104 PFU of virus intranasally experienced higher mortality compared to mice infected subcutaneously with the same dose of rMP-12 (Fig. 7A). Therefore, during subsequent in vivo challenges, 3.5 × 104 PFU of virus was administered via the intranasal route.

Fig 7.

Survival following RVFV infection is dependent on the route of infection and MAVS. (A) Mice were infected either subcutaneously or intranasally and were monitored daily for death or severe morbidity (five mice per group). (B) WT (n = 12) or Mavs−/− (n = 13) mice were challenged intranasally and monitored daily for 28 days. All infections were performed with 3.5 × 104 PFU of rMP-12. Significance: **, P ≤ 0.01.

Our in vitro studies have demonstrated a clear role for MAVS and RIG-I in RVFV-induced type I IFN responses; however, the role of these molecules in clinical infection is unclear. To determine the role of MAVS in susceptibility to RVFV infection in vivo, intranasal inoculation with rMP-12 was performed using WT and Mavs−/− mice, and survival was monitored for 28 days. After mucosal challenge, mice lacking MAVS experienced significantly more mortality over time compared to WT mice (Fig. 7B).

In order to determine whether MAVS had an impact on early innate immune responses and morbidity, intranasally infected WT and Mavs−/− mice were sacrificed in groups every other day out to 10 days. Spontaneous death in Mavs−/− mice began occurring on day 5 of infection, whereas Mavs+/+ mice began to succumb to infection on day 8. All euthanized mice underwent necropsy and were photographed. Mavs−/− mice sacrificed on day 8 had a pale ischemic liver and necrotic bowel compared to uninfected control mice (data not shown). We also noted that mice requiring humane sacrifice deteriorated quickly, transitioning from apparently healthy to moribund within a matter of hours. No neurological symptoms in infected mice were observed during the course of infection.

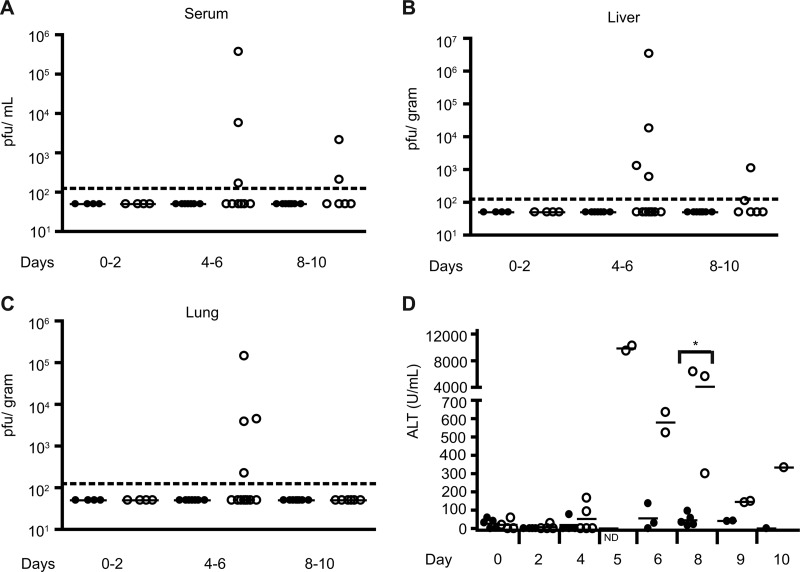

Wild-type mice infected intranasally with RVFV rMP-12 had undetectable viral loads in the serum, liver, and lungs at early (day 0 to 2), middle (day 4 to 6), and late (day 8 to 10) time points during the study (Fig. 8A to C). In contrast, a subset of Mavs−/− mice exhibited elevated viral loads in serum (Fig. 8A) during the middle (days 4 to 6) to late (days 8 to 10) stages of infection; however, the majority of the mice had undetectable viral loads. The mean serum viral loads for the positive mice were 1.3 × 105 PFU/ml in the middle period and 1.2 × 103 PFU/ml in the late period.

Fig 8.

Increased viral burden and organ damage in Mavs−/− mice compared to WT mice after mucosal RVFV exposure. The viral burden was determined by plaque assay in serum (A), liver (B), and lung (C) in Mavs−/− mice (○) compared to WT mice (●) during intranasal infection with 3.5 × 104 PFU of rMP-12/ml. The dotted line signifies the lower limit of detection. (D) Serum ALT levels in Mavs−/− mice (○) compared to WT mice (●). Significance: *, P ≤ 0.05. ND, not determined.

Mavs−/− mice also exhibited higher viral loads compared to WT mice in the liver (Fig. 8B) during the middle to late periods of infection. The mean liver titer during the middle period of infection in MAVS-deficient mice was 8.5 × 105 PFU/g. During the late period of infection, the mean virus titer was 6 × 102 PFU/g. In correlation with elevated viral loads in the liver, Mavs−/− mice exhibited elevated ALT levels, a marker for liver damage, compared to WT mice with levels peaking during the middle period of infection (days 4 to 6) (Fig. 8D).

Viral load was higher in the lungs of Mavs−/− mice compared to WT mice during the middle period of infection, with a mean titer of 3.8 × 104 PFU/g in viremic mice (Fig. 8C). Similar to WT mice, the MAVS-deficient mice showed undetectable levels of virus in the lungs during the late period of infection.

Despite a deficiency in type I IFN and ISG production observed in vitro, Mavs−/− mice exhibited a robust inflammatory response throughout infection, as measured in serum collected throughout infection (Table 1). In mice humanely sacrificed on day 5, cytokines with the overall highest induction in Mavs−/− mice included IL-6, G-CSF, and MIG (data not shown). Cytokines IL-6, IL-10, MCP-1, and MIG were significantly increased in Mavs−/− mice compared to wild-type on day 8 of infection (Table 1). Other cytokines that had a notable (>4-fold) induction in Mavs−/− compared to WT mice included GM-CSF, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-12p70, IL-17, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and TNF-α. Cytokines with <4-fold induction between WT and Mavs−/− on day 8, when wild-type mice began to succumb to infection, included Eotaxin, G-CSF, IL-1α, IL-5, IL-7, IL-9, IL-13, IL-15, IP-10, KC, LIF, LIX, M-CSF, MIP-2, RANTES, and VEGF. The levels of IL-3 and IL-12p40 were below the limit of detection in serum samples from both mouse groups on day 8 (data not shown). Interestingly, of the 32 cytokines and chemokines tested, CXCL5 (LIX) was the only protein measured that was higher in WT mice and decreased in Mavs−/− mice on all days measured (data not shown). LIX protein levels tended to decrease in WT and Mavs−/− mice over time compared to uninfected mice.

Table 1.

Serum cytokine responses at peak of rMP-12 RVFV infection

| Cytokine or chemokine | Avg level (pg/ml) ± SDa: |

Δ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT mice | Mavs−/− mice | ||

| MIP-1β | 4 ± 8 | 264 ± 229 | 66.0 |

| IL-2 | 3 ± 6 | 164 ± 260 | 54.7 |

| MIP-1α | 39 ± 62 | 1,369 ± 1,673 | 35.1 |

| MCP-1 | 25 ± 34 | 687 ± 539* | 27.5 |

| IL-17 | 3 ± 6 | 63 ± 90 | 21.0 |

| GM-CSF | 21 ± 36 | 368 ± 567 | 17.5 |

| IL-10 | 18 ± 15 | 305 ± 296* | 16.9 |

| IL-1β | 5 ± 12 | 80 ± 91 | 16.0 |

| IL-12p70 | 16 ± 24 | 253 ± 422 | 15.8 |

| MIG | 909 ± 912 | 11,091 ± 12,506* | 12.2 |

| TNF-α | 3 ± 7 | 30 ± 26 | 10.0 |

| IL-4 | 4 ± 9 | 37 ± 65 | 9.3 |

| IFN-γ | 21 ± 31 | 193 ± 322 | 9.2 |

| IL-6 | 31 ± 38 | 240 ± 227* | 7.7 |

| G-CSF | 720 ± 760 | 2,775 ± 3,542 | 3.9 |

| M-CSF | 7 ± 9 | 26 ± 20 | 3.7 |

| IL-13 | 413 ± 125 | 1,457 ± 754 | 3.5 |

| IL-5 | 35 ± 20 | 91 ± 115 | 2.6 |

| IL-7 | 13 ± 12 | 19 ± 6 | 1.5 |

| IL-9 | 931 ± 528 | 1,401 ± 944 | 1.5 |

| MIP-2 | 76 ± 92 | 108 ± 30 | 1.4 |

| Eotaxin | 882 ± 333 | 1,125 ± 287 | 1.3 |

| RANTES | 43 ± 29 | 55 ± 33 | 1.3 |

| IP-10 | 938 ± 1,064 | 1,141 ± 412 | 1.2 |

| IL-1α | 508 ± 332 | 536 ± 323 | 1.1 |

| VEGF | 7 ± 9 | 8 ± 13 | 1.1 |

| IL-15 | 237 ± 295 | 244 ± 139 | 1.0 |

| LIF | 18 ± 25 | 17 ± 5 | 0.9 |

| KC | 93 ± 82 | 85 ± 54 | 0.9 |

| LIX | 13,676 ± 13,160 | 9,369 ± 4,434 | 0.7 |

The average cytokine levels were measured in serum samples from infected animals in Mavs−/−mice compared to wild-type mice on day 8. Δ, fold change in Mavs−/− cytokine levels compared to WT cytokine levels;

, P < 0.05.

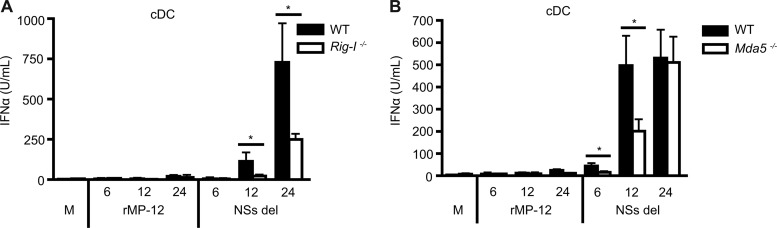

RIG-I and MDA5 mediate type I IFN response through MAVS adaptor molecule.

After demonstrating a clear role for MAVS in vitro and in vivo, we further delineated which upstream receptors were recognizing RVFV and signaling through this adaptor molecule. IFN-α responses of cDCs generated from WT and Rig-I−/− and Mda5−/− mice were measured after infection with rMP-12 or NSs del for 6, 12, or 24 h. Negligible IFN-α was induced by rMP-12 in cDCs from WT, Rig-I −/−, and Mda5−/− mice at all time points. A significant reduction in IFN-α production was observed in NSs del-infected cDCs from Rig−/− mice compared to WT mice at 12 and 24 h (Fig. 9A). cDCs from Mda5−/− mice also showed significantly reduced levels of IFN-α at 6 and 12 h compared to cDCs from WT mice. However, by 24 h the IFN-α responses from Mda5−/− cells were comparable to those of the WT mice (Fig. 9B).

Fig 9.

Type I IFN production is mediated through both RIG-I and MDA5. cDCs from wild-type or mice deficient in RIG-I (A) or MDA5 (B) were infected with rMP-12 or NSs del at an MOI of 1 for 6, 12, or 24 h. IFN-α levels in supernatants were measured by ELISA. All results are means ± the standard deviations (n = 3). Significance: *, P ≤ 0.05.

DISCUSSION

The data presented here demonstrate for the first time that the RNA helicase adaptor MAVS is required for type I IFN production in primary immune cells and is protective against mortality and morbidity during live RVFV mucosal challenge. We show that RIG-I is the predominant helicase responsible for type I IFN responses, although MDA5 may also play a role at the earliest time points of viral entry. Our studies demonstrate that TLRs do not play a role in RVFV induced type I IFN production, either in a human cell line or in murine immune cells. This is an important finding, since viruses can potentially enter the endosome after binding to a receptor on the cell surface, and thus genomic material could then be sensed by endogenous TLRs during infection (28). Viral nucleic acid can also be taken up into the endosome during autophagy (28), which would provide another potential mechanism for endosomal receptor sensing.

Using in vitro reporter assays, we demonstrate that intact RIG-I signaling is necessary for IFN-β promoter activation by RVFV. HEK293 cells are a useful model system for TLR activation since the basal expression of most TLRs is negligible. Cells stably transfected with TLR7 or TLR8 that have potential for the recognition of single-stranded viral genomic RNA did not have enhanced IFN-β signaling compared to basal HEK293 cells, indicating that the endosomal TLRs do not contribute substantively to IFN induction by RVFV. The addition of a dominant-negative construct targeting MyD88 (a common adaptor molecule for these receptors) did not impact IFN-β promoter activation, indicating that TLR7 or TLR8 activation and signaling via MyD88 is dispensable for RVFV-induced IFN-β.

Initial studies performed in HEK293 cells to determine key PRRs were confirmed using primary immune cells from WT and genetically deficient mice. These studies reveal for the first time important innate receptor recognition utilization by macrophages and DCs during RVFV infection. RNA cellular helicases were confirmed to be key receptors used by primary immune cells for recognition of RVFV, leading to the induction of type I IFN throughout infection. We were surprised at the overall low level of IFN produced by FLT3L-induced DCs compared to GM-CSF-induced cDCs or L929-derived macrophages, since pDCs have been thought to be the main producers of type I IFN in response to viral infection (50). Although pDCs are known to express RLRs, literature suggests that pDCs rely mainly on the TLR system for viral sensing (51, 52). FLT3L induces a mixed population of cDCs and pDCs; however, these cDCs may be functionally different from cDCs induced by GM-CSF since these populations are known to contain DC subsets that express different PRRs (53).

The RNA helicase adaptor molecule MAVS was necessary for control of total viral load in conventional DCs at 24 h for higher MOIs. It is likely that viral load was suppressed by IFN generated through MAVS signaling. In contrast, lack of MAVS signaling or MyD88-dependent TLR signaling did not alter viral replication in macrophages under these same conditions. This was an unexpected finding, since MAVS was shown to be necessary for type I IFN production in primary immune cells, including macrophages, and type I IFN is known to hinder replication of other viruses. There are several reasons why this discrepancy could occur. For example, our studies have shown that cDCs produce higher levels of type I IFN compared to macrophages, and a more robust IFN response may be needed to have an effect on RVFV replication. It is also possible that macrophages are utilizing other antiviral defenses besides type I IFN, such as the generation of reactive oxygen species or nitric oxide (NO), phagocytosis, or other inflammatory pathways. For example, multiplexed analysis of gene regulation in rMP-12-infected macrophages revealed that Nos2 (nitric oxide synthase 2) was upregulated 44-fold compared to uninfected cells. In comparison, GM-CSF-derived cDCs showed only 5-fold upregulation after infection (data not shown). Another explanation may be that the potential for viral entry may differ between macrophages and cDCs due to differential expression of surface receptors. Recently, DC-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3 grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN) was determined to be a receptor used in RVFV cell entry (54). However, not all cells that are infected with RVFV express DC-SIGN, suggesting there may be other critical receptors for viral entry.

Time course studies demonstrate that both macrophages and cDCs allow for very minimal viral amplification since similar viral burdens in the cell supernatant were observed over time. In these experiments, virus was removed after 2 h adsorption so that only virus released from productively infected cells could be assessed in the supernatant. The shorter adsorption time and analysis of only virus present in the supernatant versus the total viral load of cells may be why a difference in WT and Mavs−/− cDC viral burden could no longer be observed at 24 h for these studies.

We utilized two strains of attenuated RVFV for our in vitro studies. The NSs del strain offers insight into which receptors can be activated by the virus, since virulent and rMP-12 strains of RVFV would normally suppress type I IFN responses due to the ability of NSs protein to specifically inhibit this pathway (42, 55–57). It is important to note that some type I IFN was generated in response to the rMP-12 strain in primary immune cells, indicating that the inhibition of the host response is not complete.

Our studies are the first to demonstrate that MAVS is protective against mortality during in vivo RVFV infection. We observed increased amounts of type I IFN protein and ISG mRNA in cells from WT compared to Mavs−/− mice, confirming the critical role for type I IFN in RVFV infection. It had previously been established that Ifnar−/− mice have more rapid mortality with virulent RVFV strain ZH548 compared to WT mice. Also, Ifnar−/− mice succumbed to infection with MP-12 and clone 13 strain infections compared to no mortality observed with WT mice inoculated with those strains (8). We show that MAVS-deficient mice have increased viral burden and more liver damage, as assessed by the ALT level after in vivo challenge. It is interesting that even the WT mouse requiring humane sacrifice on day 8 had a lower ALT level compared to nonmoribund Mavs−/− mice sacrificed at this time. High mortality in Mavs−/− mice after intranasal challenge with rMP-12 was expected because of the deficit seen in the IFN production of immune cells from these mice in vitro and supports previously published studies showing high mortality in Ifnar−/− mice (8). Although this group reported a lack of virulence in WT mice infected intraperitoneally with MP-12, we observed >50% mortality with intranasal administration of rMP-12 in WT mice (Fig. 7A). We have observed that the route of infection largely impacts virulence, with significantly less virulence observed with subcutaneous challenge than with intranasal challenge (Fig. 7A). This may be due to a difference in which cells and organs first come into contact with the virus based on the route of virus introduction, leading to different profiles or magnitudes of host inflammatory responses. Further studies, beyond the scope of the present study, may also show a differential susceptibility in animal models challenged with virulent RVFV depending on the route of exposure. This could have potential implications for human RVFV infections, wherein a range of clinical severity and symptoms have been observed, and where risk factors for infection include both mosquito and mucosal routes of exposure (49, 58).

Interestingly, in vivo, a variety of inflammatory cytokine responses were not hindered in the absence of MAVS signaling. Many of the Mavs−/− mice that were humanely sacrificed due to moribund appearance exhibited a cytokine storm. The inflammatory proteins abundant in overwhelming amounts on day 5 in two mice requiring humane sacrifice included IL-6, G-CSF, and MIG (data not shown). IL-6 is known to be fever inducing and has been shown to be associated with other hemorrhagic fever virus infections (59, 60). G-CSF has many functions, including reducing cellular apoptosis and quelling inflammation associated with neurodegenerative diseases (61). G-CSF has also been shown to promote the accumulation of Ly6G+ granulocytes during influenza virus or Sendai virus infection to aid in viral clearance and maintain survival (62). MIG (CXCL9) has been shown to reduce coronavirus-induced liver and brain pathology (63). The cytokines IL-10 and MCP-1 were shown to be significantly different between WT and MAVS-deficient mice. IL-10 is known to be an immunomodulator and can inhibit antigen presentation and the production of inflammatory cytokines (64). IL-10 has been shown to decrease inflammation and liver damage without altering viral load in a model of murine cytomegalovirus infection (65). MCP-1 alters the migration of monocytes and macrophages that are important for combating viral infection (66).

RLRs upstream of MAVS are important for type I IFN production in response to RVFV infection. As expected, the absence of RIG-I significantly reduced IFN-α production by cDCs when infected with NSs del, strengthening our findings from in vitro studies using HEK cells in which RIG-I Dn negatively impacted activation of the IFN-β promoter. In bone marrow-derived cDCs, MDA5 also appeared to influence early IFN-α production in response to RVFV, which likely accounts for the residual responses seen in the Rig-I−/− cells at 24 h. Rig-I and Mda5 genes were similarly activated during rMP-12 and NSs del infection of WT cDCs. RIG-I and MDA5 recognize different viral nucleic acid patterns; RIG-I recognizes the 5′ triphosphate end of ssRNA generated by viral polymerases, whereas MDA5 recognizes dsRNA and has been shown to be critical for recognizing members of the picornavirus family (43). Despite recognizing distinct substrates, both RIG-I and MDA5 have also been shown to contribute to recognition of West Nile virus and dengue virus (67, 68). Here, we also demonstrate a redundant role for these molecules in the induction of type I IFN responses by RVFV.

Although these studies have identified the initial receptor dependence in IFN production in mice, receptor preference in human cells should be verified. In a clinical setting, RVFV-infected patients exhibit a wide range of symptoms, from minor febrile illness to much more severe manifestations such as hemorrhagic fever and death. It is unknown why such a range of variability exists between patients. It is likely that genetic factors may contribute to this diversity. Studies with rats have confirmed that resistance against severe RVFV-induced pathology can be inherited as a dominant gene (69) and that subtle differences between rats of the same strain from different facilities can alter disease outcomes (70, 71). Ultimately, polymorphisms in crucial innate immune receptors in human populations could be identified and screened in conjunction with monitoring the gamut of patient disease progression. Polymorphisms in receptors that bolster early and robust type I IFN responses could hold the key to unlocking the source of diversity between severe and mild clinical outcomes in patients infected with Rift Valley fever virus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Krupen Patel for maintaining the mouse colonies used in this study, Susan Heavey for technical assistance, and Kim Brustoski for scientific discussions. We are grateful to Shizuo Akira (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan) for TLR- and adaptor-deficient mice. The J558L cells were kindly provided by the laboratory of Clifford Harding (Case Western Reserve University). We thank Shinji Makino and Tetsuro Ikegami (University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX) for providing attenuated RVFV strains and C. J. Peters (University of Texas Medical Branch) for scientific advice.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R21AI083693 (A.G.H.), R21AI079617 (A.G.H), and U54AI057160 to the Midwest Regional Center of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Disease Research (A.G.H). M.E.E. was supported in part by NIH training grant T32AI089474.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 13 February 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Pepin M, Bouloy M, Bird BH, Kemp A, Paweska J. 2010. Rift Valley fever virus (Bunyaviridae: Phlebovirus): an update on pathogenesis, molecular epidemiology, vectors, diagnostics, and prevention. Vet. Res. 41:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Daubney RHJ, Garnham PC. 1931. An undescribed virus disease of sheep, cattle, and man from East Africa. J. Pathol. Bacteriol. 34:545–579 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carroll SA, Reynes JM, Khristova ML, Andriamandimby SF, Rollin PE, Nichol ST. 2011. Genetic evidence for Rift Valley fever outbreaks in Madagascar resulting from virus introductions from the East African mainland rather than enzootic maintenance. J. Virol. 85:6162–6167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shoemaker T, Boulianne C, Vincent MJ, Pezzanite L, Al-Qahtani MM, Al-Mazrou Y, Khan AS, Rollin PE, Swanepoel R, Ksiazek TG, Nichol ST. 2002. Genetic analysis of viruses associated with emergence of Rift Valley fever in Saudi Arabia and Yemen, 2000-01. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:1415–1420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Anyamba A, Linthicum KJ, Small J, Britch SC, Pak E, de La Rocque S, Formenty P, Hightower AW, Breiman RF, Chretien JP, Tucker CJ, Schnabel D, Sang R, Haagsma K, Latham M, Lewandowski HB, Magdi SO, Mohamed MA, Nguku PM, Reynes JM, Swanepoel R. 2010. Prediction, assessment of the Rift Valley fever activity in East and Southern Africa 2006-2008 and possible vector control strategies. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 83:43–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peters CJ, Reynolds JA, Slone TW, Jones DE, Stephen EL. 1986. Prophylaxis of Rift Valley fever with antiviral drugs, immune serum, an interferon inducer, and a macrophage activator. Antivir. Res. 6:285–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morrill JC, Jennings GB, Cosgriff TM, Gibbs PH, Peters CJ. 1989. Prevention of Rift Valley fever in rhesus monkeys with interferon-alpha. Rev. Infect. Dis. 11(Suppl 4):S815–S825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bouloy M, Janzen C, Vialat P, Khun H, Pavlovic J, Huerre M, Haller O. 2001. Genetic evidence for an interferon-antagonistic function of rift valley fever virus nonstructural protein NSs. J. Virol. 75:1371–1377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kawai T, Akira S. 2008. Toll-like receptor and RIG-I-like receptor signaling. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1143:1–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Davis CW, Nguyen HY, Hanna SL, Sanchez MD, Doms RW, Pierson TC. 2006. West Nile virus discriminates between DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR for cellular attachment and infection. J. Virol. 80:1290–1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Klimstra WB, Nangle EM, Smith MS, Yurochko AD, Ryman KD. 2003. DC-SIGN and L-SIGN can act as attachment receptors for alphaviruses and distinguish between mosquito cell- and mammalian cell-derived viruses. J. Virol. 77:12022–12032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meyer-Wentrup F, Benitez-Ribas D, Tacken PJ, Punt CJ, Figdor CG, de Vries IJ, Adema GJ. 2008. Targeting DCIR on human plasmacytoid dendritic cells results in antigen presentation and inhibits IFN-α production. Blood 111:4245–4253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sabbah A, Chang TH, Harnack R, Frohlich V, Tominaga K, Dube PH, Xiang Y, Bose S. 2009. Activation of innate immune antiviral responses by Nod2. Nat. Immunol. 10:1073–U49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Allen IC, Scull MA, Moore CB, Holl EK, McElvania-TeKippe E, Taxman DJ, Guthrie EH, Pickles RJ, Ting JPY. 2009. The NLRP3 inflammasome mediates in vivo innate immunity to influenza A virus through recognition of viral RNA. Immunity 30:556–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ichinohe T, Lee HK, Ogura Y, Flavell R, Iwasaki A. 2009. Inflammasome recognition of influenza virus is essential for adaptive immune responses. J. Exp. Med. 206:79–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rathinam VAK, Jiang ZZ, Waggoner SN, Sharma S, Cole LE, Waggoner L, Vanaja SK, Monks BG, Ganesan S, Latz E, Hornung V, Vogel SN, Szomolanyi-Tsuda E, Fitzgerald KA. 2010. The AIM2 inflammasome is essential for host defense against cytosolic bacteria and DNA viruses. Nat. Immunol. 11:395–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Segovia J, Sabbah A, Mgbemena V, Tsai SY, Chang TH, Berton MT, Morris IR, Allen IC, Ting JPY, Bose S. 2012. TLR2/MyD88/NF-κB pathway, reactive oxygen species, potassium efflux activates NLRP3/ASC inflammasome during respiratory syncytial virus infection. PLoS One 7:e29695 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. West AP, Koblansky AA, Ghosh S. 2006. Recognition and signaling by Toll-like receptors. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22:409–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gorden KK, Qiu XX, Binsfeld CC, Vasilakos JP, Alkan SS. 2006. Cutting edge: activation of murine TLR8 by a combination of imidazoquinoline immune response modifiers and polyT oligodeoxynucleotides. J. Immunol. 177:6584–6587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bauer S, Bathke B, Lauterbach H, Patzold J, Kassub R, Luber CA, Schlatter B, Hamm S, Chaplin P, Suter M, Hochrein H. 2010. A major role for TLR8 in the recognition of vaccinia viral DNA by murine pDC? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:E139–E139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Martinez J, Huang XP, Yang YP. 2010. Toll-like receptor 8-mediated activation of murine plasmacytoid dendritic cells by vaccinia viral DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:6442–6447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Loo YM, Fornek J, Crochet N, Bajwa G, Perwitasari O, Martinez-Sobrido L, Akira S, Gill MA, Garcia-Sastre A, Katze MG, Gale M., Jr 2008. Distinct RIG-I and MDA5 signaling by RNA viruses in innate immunity. J. Virol. 82:335–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schlee M, Roth A, Hornung V, Hagmann CA, Wimmenauer V, Barchet W, Coch C, Janke M, Mihailovic A, Wardle G, Juranek S, Kato H, Kawai T, Poeck H, Fitzgerald KA, Takeuchi O, Akira S, Tuschl T, Latz E, Ludwig J, Hartmann G. 2009. Recognition of 5′ triphosphate by RIG-I helicase requires short blunt double-stranded RNA as contained in panhandle of negative-strand virus. Immunity 31:25–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hornung V, Ellegast J, Kim S, Brzozka K, Jung A, Kato H, Poeck H, Akira S, Conzelmann KK, Schlee M, Endres S, Hartmann G. 2006. 5′-Triphosphate RNA is the ligand for RIG-I. Science 314:994–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gitlin L, Barchet W, Gilfillan S, Cella M, Beutler B, Flavell RA, Diamond MS, Colonna M. 2006. Essential role of mda-5 in type I IFN responses to polyriboinosinic:polyribocytidylic acid and encephalomyocarditis picornavirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:8459–8464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pichlmair A, Schulz O, Tan CP, Rehwinkel J, Kato H, Takeuchi O, Akira S, Way M, Schiavo G, Reis e Sousa C. 2009. Activation of MDA5 requires higher-order RNA structures generated during virus infection. J. Virol. 83:10761–10769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Komuro A, Bamming D, Horvath CM. 2008. Negative regulation of cytoplasmic RNA-mediated antiviral signaling. Cytokine 43:350–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xagorari A, Chlichlia K. 2008. Toll-like receptors and viruses: induction of innate antiviral immune responses. Open Microbiol. J. 2:49–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Satoh T, Kato H, Kumagai Y, Yoneyama M, Sato S, Matsushita K, Tsujimura T, Fujita T, Akira S, Takeuchi O. 2010. LGP2 is a positive regulator of RIG-I- and MDA5-mediated antiviral responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:1512–1517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rothenfusser S, Goutagny N, DiPerna G, Gong M, Monks BG, Schoenemeyer A, Yamamoto M, Akira S, Fitzgerald KA. 2005. The RNA helicase Lgp2 inhibits TLR-independent sensing of viral replication by retinoic acid-inducible gene-I. J. Immunol. 175:5260–5268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Habjan M, Andersson I, Klingstrom J, Schumann M, Martin A, Zimmermann P, Wagner V, Pichlmair A, Schneider U, Muhlberger E, Mirazimi A, Weber F. 2008. Processing of genome 5′ termini as a strategy of negative-strand RNA viruses to avoid RIG-I-dependent interferon induction. PLoS One 3:e2032 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. 2001. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-κB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature 413:732–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Funami K, Matsumoto M, Oshiumi H, Akazawa T, Yamamoto A, Seya T. 2004. The cytoplasmic ‘linker region’ in Toll-like receptor 3 controls receptor localization and signaling. Int. Immunol. 16:1143–1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang J, Shao Y, Bennett TA, Shankar RA, Wightman PD, Reddy LG. 2006. The functional effects of physical interactions among Toll-like receptors 7, 8, and 9. J. Biol. Chem. 281:37427–37434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Caplen H, Peters CJ, Bishop DH. 1985. Mutagen-directed attenuation of Rift Valley fever virus as a method for vaccine development. J. Gen. Virol. 66(Pt 10):2271–2277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ikegami T, Won S, Peters CJ, Makino S. 2006. Rescue of infectious rift valley fever virus entirely from cDNA, analysis of virus lacking the NSs gene, and expression of a foreign gene. J. Virol. 80:2933–2940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu YC, Gray RC, Hardy GAD, Kuchtey J, Abbott DW, Emancipator SN, Harding CV. 2010. CpG-B oligodeoxynucleotides inhibit TLR-dependent and -independent induction of type I IFN in dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 184:3367–3376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pecora ND, Fulton SA, Reba SM, Drage MG, Simmons DP, Urankar-Nagy NJ, Boom WH, Harding CV. 2009. Mycobacterium bovis BCG decreases MHC-II expression in vivo on murine lung macrophages and dendritic cells during aerosol infection. Cell. Immunol. 254:94–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Qu Y, Ramachandra L, Mohr S, Franchi L, Harding CV, Nunez G, Dubyak GR. 2009. P2X7 receptor-stimulated secretion of MHC class II-containing exosomes requires the ASC/NLRP3 inflammasome but is independent of caspase-1. J. Immunol. 182:5052–5062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fitzgerald KA, Palsson-McDermott EM, Bowie AG, Jefferies CA, Mansell AS, Brady G, Brint E, Dunne A, Gray P, Harte MT, McMurray D, Smith DE, Sims JE, Bird TA, O'Neill LA. 2001. Mal (MyD88-adapter-like) is required for Toll-like receptor-4 signal transduction. Nature 413:78–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ablasser A, Poeck H, Anz D, Berger M, Schlee M, Kim S, Bourquin C, Goutagny N, Jiang Z, Fitzgerald KA, Rothenfusser S, Endres S, Hartmann G, Hornung V. 2009. Selection of molecular structure and delivery of RNA oligonucleotides to activate TLR7 versus TLR8 and to induce high amounts of IL-12p70 in primary human monocytes. J. Immunol. 182:6824–6833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Le May N, Mansuroglu Z, Leger P, Josse T, Blot G, Billecocq A, Flick R, Jacob Y, Bonnefoy E, Bouloy M. 2008. A SAP30 complex inhibits IFN-β expression in Rift Valley fever virus-infected cells. PLoS Pathog. 4:e13 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0040013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kato H, Takeuchi O, Sato S, Yoneyama M, Yamamoto M, Matsui K, Uematsu S, Jung A, Kawai T, Ishii KJ, Yamaguchi O, Otsu K, Tsujimura T, Koh CS, Reis e Sousa C, Matsuura Y, Fujita T, Akira S. 2006. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature 441:101–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Medzhitov R. 2001. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 1:135–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Weber F, Wagner V, Rasmussen SB, Hartmann R, Paludan SR. 2006. Double-stranded RNA is produced by positive-strand RNA viruses and DNA viruses but not in detectable amounts by negative-strand RNA viruses. J. Virol. 80:5059–5064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kurt-Jones EA, Popova L, Kwinn L, Haynes LM, Jones LP, Tripp RA, Walsh EE, Freeman MW, Golenbock DT, Anderson LJ, Finberg RW. 2000. Pattern recognition receptors TLR4 and CD14 mediate response to respiratory syncytial virus. Nat. Immunol. 1:398–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lagos D, Vart RJ, Gratrix F, Westrop SJ, Emuss V, Wong PP, Robey R, Imami N, Bower M, Gotch F, Boshoff C. 2008. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates innate immunity to Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus. Cell Host Microbe 4:470–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Okumura A, Pitha PM, Yoshimura A, Harty RN. 2010. Interaction between Ebola virus glycoprotein and host Toll-like receptor 4 leads to induction of proinflammatory cytokines and SOCS1. J. Virol. 84:27–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. LaBeaud AD, Muchiri EM, Ndzovu M, Mwanje MT, Muiruri S, Peters CJ, King CH. 2008. Interepidemic Rift Valley fever virus seropositivity, northeastern Kenya. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:1240–1246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Colonna M, Krug A, Cella M. 2002. Interferon-producing cells: on the front line in immune responses against pathogens. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14:373–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kato H, Sato S, Yoneyama M, Yamamoto M, Uematsu S, Matsui K, Tsujimura T, Takeda K, Fujita T, Takeuchi O, Akira S. 2005. Cell type-specific involvement of RIG-I in antiviral response. Immunity 23:19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Luber CA, Cox J, Lauterbach H, Fancke B, Selbach M, Tschopp J, Akira S, Wiegand M, Hochrein H, O'Keeffe M, Mann M. 2010. Quantitative proteomics reveals subset-specific viral recognition in dendritic cells. Immunity 32:279–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hoshino K, Kaisho T. 2008. Nucleic acid sensing Toll-like receptors in dendritic cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 20:408–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lozach PY, Kuhbacher A, Meier R, Mancini R, Bitto D, Bouloy M, Helenius A. 2011. DC-SIGN as a receptor for phleboviruses. Cell Host Microbe 10:75–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Habjan M, Pichlmair A, Elliott RM, Overby AK, Glatter T, Gstaiger M, Superti-Furga G, Unger H, Weber F. 2009. NSs protein of Rift Valley fever virus induces the specific degradation of the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase. J. Virol. 83:4365–4375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ikegami T, Narayanan K, Won S, Kamitani W, Peters CJ, Makino S. 2009. Rift Valley fever virus NSs protein promotes posttranscriptional downregulation of protein kinase PKR and inhibits eIF2α phosphorylation. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000287 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Le May N, Dubaele S, Proietti De Santis L, Billecocq A, Bouloy M, Egly JM. 2004. TFIIH transcription factor, a target for the Rift Valley hemorrhagic fever virus. Cell 116:541–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. LaBeaud AD, Muiruri S, Sutherland LJ, Dahir S, Gildengorin G, Morrill J, Muchiri EM, Peters CJ, King CH. 2011. Postepidemic analysis of Rift Valley fever virus transmission in northeastern Kenya: a village cohort study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 5:e1265 doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Geisbert TW, Jahrling PB. 2004. Exotic emerging viral diseases: progress and challenges. Nat. Med. 10:S110–S121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Outinen TK, Makela SM, Ala-Houhala IO, Huhtala HSA, Hurme M, Paakkala AS, Porsti IH, Syrjanen JT, Mustonen JT. 2010. The severity of Puumala hantavirus induced nephropathia epidemica can be better evaluated using plasma interleukin-6 than C-reactive protein determinations. BMC Infect. Dis. 10:132–139 doi:10.1186/1471-2334-10-132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pollari E, Savchenko E, Jaronen M, Kanninen K, Malm T, Wojciechowski S, Ahtoniemi T, Goldsteins G, Giniatullina R, Giniatullin R, Koistinaho J, Magga J. 2011. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor attenuates inflammation in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neuroinflamm. 8:74–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hermesh T, Moran TM, Jain D, Lopez CB. 2012. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor protects mice during respiratory virus infections. PLoS One 7:e37334 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0037334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Muse M, Kane JAC, Carr DJJ, Farber JM, Lane TE. 2008. Insertion of the CXC chemokine ligand 9 (CXCL9) into the mouse hepatitis virus genome results in protection from viral-induced encephalitis and hepatitis. Virology 382:132–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mosser DM, Zhang X. 2008. Interleukin-10: new perspectives on an old cytokine. Immunol. Rev. 226:205–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tang-Feldman YJ, Lochhead GR, Lochhead SR, Yu C, Pomeroy C. 2011. Interleukin-10 repletion suppresses proinflammatory cytokines and decreases liver pathology without altering viral replication in murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV)-infected IL-10 knockout mice. Inflamm. Res. 60:233–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Deshmane SL, Kremlev S, Amini S, Sawaya BE. 2009. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1): an overview. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 29:313–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Fredericksen BL, Keller BC, Fornek J, Katze MG, Gale M. 2008. Establishment and maintenance of the innate antiviral response to west nile virus involves both RIG-I and MDA5 signaling through IPS-1. J. Virol. 82:609–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Nasirudeen AMA, Wong HH, Thien PL, Xu SL, Lam KP, Liu DX. 2011. RIG-I, MDA5, and TLR3 synergistically play an important role in restriction of dengue virus infection. PLoS Negl. Trop. D 5:e926 doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Peters CJ, J AG. 1981. Pathogenesis of Rift Valley fever. Contrib. Epidemiol. Biostat. 3:21–41 [Google Scholar]

- 70. Anderson GW, Jr, Slone TW, Jr, Peters CJ. 1987. Pathogenesis of Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) in inbred rats. Microb. Pathog. 2:283–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ritter M, Bouloy M, Vialat P, Janzen C, Haller O, Frese M. 2000. Resistance to Rift Valley fever virus in Rattus norvegicus: genetic variability within certain ‘inbred’ strains. J. Gen. Virol. 81:2683–2688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]