Abstract

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) encodes one conventional protein kinase, UL97. During infection, UL97 phosphorylates the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein (pRb) on sites ordinarily phosphorylated by cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK), inactivating the ability of pRb to repress host genes required for cell cycle progression to S phase. UL97 is important for viral DNA synthesis in quiescent cells, but this function can be replaced by human papillomavirus type 16 E7, which targets pRb for degradation. However, viruses in which E7 replaces UL97 are still defective for virus production. UL97 is also required for efficient nuclear egress of viral nucleocapsids, which is associated with disruption of the nuclear lamina during infection, and phosphorylation of lamin A/C on serine 22, which antagonizes lamin polymerization. We investigated whether inactivation of pRb might overcome the requirement of UL97 for these roles, as pRb inactivation induces CDK1, and CDK1 phosphorylates lamin A/C on serine 22. We found that lamin A/C serine 22 phosphorylation during HCMV infection correlated with expression of UL97 and was considerably delayed in UL97-null mutants, even when E7 was expressed. E7 failed to restore gaps in the nuclear lamina seen in wild-type but not UL97-null virus infections. In electron microscopy analyses, a UL97-null virus expressing E7 was as impaired as a UL97-null mutant in cytoplasmic accumulation of viral nucleocapsids. Our results demonstrate that pRb inactivation is insufficient to restore efficient viral nuclear egress of HCMV in the absence of UL97 and instead argue further for a direct role of UL97 in this stage of the infectious cycle.

INTRODUCTION

Efforts to establish a definitive role for a given viral protein can be confounded when the protein acts at multiple stages of the infectious cycle. The only conventional protein kinase encoded by human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), UL97, represents an example of this challenge, particularly because it is a protein kinase. Phosphorylation is a crucial posttranslational modification influencing myriad processes in eukaryotic cells. Further complicating matters, only a subset of phosphorylation events mediated by a viral protein kinase are likely to be important for viral replication, and evidence of such relevance is often defined by downstream effects far removed from the initial conjugation of a phosphate group to an amino acid side chain. Thus, identification of physiologically important substrates is hardly trivial.

Studies of UL97 mutants and UL97 inhibitors have shown that UL97 is important for viral replication (1–3) and have led investigators to implicate this viral protein kinase in numerous stages of the infectious cycle, including viral DNA synthesis, encapsidation of viral DNA, egress of nucleocapsids from the nucleus (nuclear egress), and late events in assembly and morphogenesis (3–9). Although purified UL97 is sufficient to phosphorylate certain proteins in vitro (6, 10–13) and UL97 is necessary for wild-type patterns of phosphorylation of several proteins in infected cells (6, 8, 10, 12–15), both sufficiency and necessity have been demonstrated for only a few substrates (6, 9, 12, 13, 15). To our knowledge, of these, only the nuclear lamina component lamin A/C and the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein (pRb) have been shown to be phosphorylated in a UL97-dependent manner on the same sites in vitro and in infected cells (6, 15), which is necessary but still insufficient evidence for these proteins being physiological substrates of UL97 (14). In the case of pRb, the sites phosphorylated are known to inactivate pRb function, thus relieving repression of promoters regulated by E2F family transcription factors (15, 16). Moreover, pRb inactivation by UL97 is important for viral replication, as a virus (Δ97-E7) (6) in which UL97 is replaced by human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) E7, which inactivates pRb by binding it and targeting it for degradation (17–19), replicates much better than a UL97-null mutant in quiescent (serum-starved) cells (8). In these cells, E7 complements the loss of UL97 for induction of E2F-responsive cellular genes encoding S-phase proteins, such as nucleotide metabolism enzymes, and for efficient viral DNA synthesis during HCMV infection (8). Thus, the pRb-inactivating function of UL97 likely explains its role in viral DNA synthesis. However, Δ97-E7 replicates no better than a UL97-null mutant in asynchronously dividing (serum-fed) cells (8). Thus, these results do not address which stages of viral infection require activities of UL97 other than pRb inactivation in either dividing or quiescent cells.

Of the several possible stages of viral replication at which an activity of UL97 other than pRb inactivation might be required, one that we considered was nuclear egress. Nuclear egress defects correlate well with overall replication defects of UL97-null mutants in serum-fed cells (9). UL97 phosphorylates lamin A/C on residues, including serine 22 (6), whose phosphorylation during mitosis by CDK1/cyclin B has been shown to be crucial for disassembly of the nuclear lamina (20). Defects of Δ97 mutants in nuclear egress are associated with impaired phosphorylation on this residue in infected cells and a failure of the nuclear lamina to show the thinning, gaps, and morphological changes characteristic of wild-type HCMV infection (6, 21). Thus, a simple model is that UL97 phosphorylates lamin A/C to promote disruption of the nuclear lamina, permitting access of nucleocapsids to the inner nuclear membrane during nuclear egress. However, it is also plausible that pRb inactivation by UL97 could be sufficient to promote nuclear egress. Active pRb negatively regulates expression of CDK1, which, in complex with cyclin B, as noted above, phosphorylates lamin A/C on Ser22 to promote disassembly of the nuclear lamina during mitosis (20, 22–24). Indeed, CDK1 and cyclin B are upregulated during HCMV infection (25–27). Although we found that overall phosphorylation of lamin A/C could be reduced by transient treatment with a UL97 inhibitor but not with a CDK inhibitor (6), that experiment did not exclude a role for CDK1, especially for Ser22 phosphorylation.

In this study, we sought to clarify whether the requirement for UL97 in nuclear egress represents a downstream effect of UL97-mediated pRb inactivation or a direct requirement for UL97 in this process. We examined the kinetics of UL97 expression and lamin A/C Ser22 phosphorylation, as well as the effects of expression of the pRb-inactivating protein, HPV16 E7, on nuclear egress defects in UL97-null viruses. Our results indicate that a major block for replication of Δ97-E7 is nuclear egress and support a direct role for UL97 in this process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

MRC-5 human embryonic lung fibroblasts (CCL-171) and Hs27 human foreskin fibroblasts (Hs27 HFFs) were obtained from ATCC and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM; Cellgro, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma-Aldrich or Atlanta Biologicals) and 20 μg/ml gentamicin (Life Technologies) (complete medium). For serum starvation experiments, cells were seeded in complete medium, allowed to attach for at least 2 h (see below for times), washed twice in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline without magnesium or calcium (DPBS; Cellgro) or in DMEM containing 0.1% FBS and 20 μg/ml gentamicin (0.1% FBS-DMEM), and maintained in 0.1% FBS-DMEM for 72 h prior to and during infection. For dividing conditions, cells were seeded in complete medium, allowed to attach for at least 4 h prior to infection (see below for times), and infected in 0.1% FBS-DMEM for 2 h, after which inocula were removed, cells were rinsed with DPBS, and the medium was replaced with 5% FBS-DMEM. Hs27-19K cells were obtained from Hs27 HFF cells following retroviral transduction using a previously described vector, pLXSN-E1B19K, expressing the adenovirus type 5 E1B-19K protein (28), a generous gift of Wolfram Brune (University of Hamburg) and Igor Jurak (Harvard Medical School). Hs27-19K cells were used to cultivate Δ97-E7 viruses, as these cells produce higher yields of this virus (J. P. Kamil, unpublished observation). HCMV strain AD169rv and its derivative viruses, Δ97 and Δ97-E7, have been previously described (7, 15, 29). All HCMV infection experiments were performed at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 PFU/cell, except for the immunofluorescence (IF) experiments, which were performed at an MOI of 3 PFU/cell.

Western blotting.

Western blotting was performed as previously described (7, 8). Briefly, MRC-5 cells were seeded at 3.5 × 105 cells per well in 6-well cluster plates (Falcon) and allowed to attach for 4 h in complete medium. Cells were then rinsed with DBPS, and medium was replaced with 0.1% FBS-DMEM (serum starvation medium). After incubation in serum starvation medium for 72 h, cells were mock infected or infected with the indicated viruses. At various time points postinfection, cells were lysed in 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer (30) containing 1× Halt phosphatase and protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific Pierce) and 5% β-mercaptoethanol, heated for 5 min at 95°C, and resolved on denaturing SDS-PAGE gels (7, 8). Proteins were electrophoretically transferred to Protran BA85 nitrocellulose membranes (Whatman) using a Criterion blotter (Bio-Rad) and blocked in phosphate-buffered saline (3.2 mM Na2HPO4, 0.5 mM KH2PO4, 1.3 mM KCl, 135 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) (PBS) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST) and 5% powdered milk (PM-PBST). Antibodies specific for lamin A/C Ser22 (rabbit polyclonal; Cell Signaling Technology), total lamin A/C (goat polyclonal N-18; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), retinoblastoma protein (pRb) (mouse monoclonal clone 4H1; Cell Signaling Technology), pRb phosphorylated at serine positions 807 and 811 (rabbit polyclonal; Cell Signaling Technology), beta-tubulin (rabbit monoclonal; Epitomics), beta-actin (mouse monoclonal; Li-Cor), UL97 (7), UL44 (mouse monoclonal; Virusys), IE1-72 (mouse monoclonal 1B12; a generous gift of Tom Shenk, Princeton University), and pp150 (mouse monoclonal 36-14; a generous gift of Bill Britt, University of Alabama at Birmingham) were diluted into PM-PBST and used to probe membranes for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were then washed at least three times, for 10 min per wash, in PBST and probed with anti-rabbit, anti-goat, or anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Southern Biotechnology, Inc.) diluted 1:5,000 in PBST, washed again, as above, and imaged by chemiluminescence (Supersignal Pico; Thermo Scientific Pierce), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

qPCR.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using a previously described method (31). Details are provided in supplemental materials and methods posted at https://coen.med.harvard.edu.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

For serum-starved conditions, MRC-5 cells were seeded at 7 × 104 cells/well on glass coverslips in 24-well plates and allowed to attach for 6 h prior to serum starvation for 72 h. For dividing conditions, MRC-5 and HFF cells were seeded at 7 × 104 cells/well on glass coverslips in 24-well plates and allowed to attach for 6 h before infection. Cells were infected with wild-type AD169rv (WT), Δ97, or Δ97-E7 viruses in triplicate at an MOI of 3 for 2 h. The inocula were prepared in 0.1% FBS DMEM, and titers were confirmed by back titration. At 96 h postinfection, cells were rinsed with DPBS once and fixed with 3.6% formaldehyde (Sigma) in DPBS for 10 min. Cells were washed three times with DPBS and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in DPBS for 15 min. Cells were washed three times with DPBS and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in DPBS for 1 h. Primary antibodies were diluted in 1% BSA and incubated with fixed cells overnight at 4°C. Lamin A/C goat polyclonal antibody N-18 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used at 1:10, and cytomegalovirus (CMV) ICP36 mouse monoclonal antibody that recognizes UL44 (Virusys) was used at 1:100. Cells were washed once with 0.1% Tween 20 for 5 min and then washed twice with DPBS for 5 min. Secondary antibodies were diluted in 1% BSA and incubated with cells for 1 h. Alexa Fluor 568 donkey anti-goat IgG (Invitrogen) and Alexa Fluor 488 chicken anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes) were used at 1:1,000. Cells were incubated with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 5 min and then washed once with 0.1% Tween 20 for 5 min and twice with DPBS for 5 min. Coverslips were mounted on microscope slides with ProLong Antifade (Invitrogen Molecular Probes). Mounted slides were allowed to cure overnight and were then sealed. Fluorescence microscopy was performed in the Nikon Imaging Center at Harvard Medical School using a Yokogawa CSU10 spinning disk confocal system on a Nikon Ti inverted microscope equipped with a 60× Plan Apo differential interference contrast oil immersion 1.4 objective lens. Laser confocal images were acquired with a Hamamatsu ORCA-AG cooled charged-coupled-device (CCD) camera controlled with Metamorph/Universal Imaging software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Serial optical sections with a 0.25-μm z-step size were collected and used to create three-dimensional (3-D) reconstruction images. The reconstructions were used to determine the number of cells with gaps, where a discontinuity in fluorescence along the perimeter of a nucleus constituted a gap. Statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism Version 5.0d software. For each cell/serum condition, the number of infected cells counted for each experimental group was between 55 and 187. Two Fisher's exact tests were performed to compare each mutant to WT virus, and they were evaluated with an α level of 0.0253 (adjusted for the dual comparisons). All P values were less than or equal to 0.0089.

Electron microscopy.

Transmission electron microscopy (EM) was performed in the Harvard Cell Biology EM Core Facility. For serum-starved conditions, MRC-5 cells were seeded at 3 × 105 cells/well in a 6-well plate and allowed to attach for 4 to 5 h prior to serum starvation. For dividing conditions, MRC-5 and HFF cells were seeded at 3 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates and allowed to attach for 4 to 5 h before infection. Cells were infected with WT, Δ97, or Δ97-E7 viruses in duplicate at an MOI of 1 for 2 h. Inocula were prepared in 0.1% FBS DMEM, and titers were confirmed by back titration. HFF and MRC-5 cells were fixed at 72 hours postinfection (hpi) and 96 hpi, respectively, in 1.25% paraformaldehyde–2.5% glutaraldehyde–0.03% picric acid in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). Cells were then washed in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide–1.5% potassium ferrocyanide for 1 h, washed three times in water, incubated in 1% aqueous uranyl acetate for 1 h, washed twice in water, and subsequently dehydrated in grades of ethanol of 70% and 95% (10 min each) and 100% (twice, 10 min per wash). Cells were removed from the dish into propylene oxide, pelleted, and incubated overnight in a 1:1 mixture of propylene oxide and TAAB Epon (Marivac Canada). The following day, the samples were embedded in TAAB Epon and polymerized at 60°C for 48 h. Ultrathin sections (about 60 nm) were cut on a Reichert Ultracut S Microtome, picked up onto copper grids stained with lead citrate, and examined with a TecnaiG2 Spirit BioTWIN. Images were recorded with an AMT 2k CCD camera. For each of the nine conditions, 10 or 11 sections that each contained a whole cell were randomly selected and fully photographed in parts with no overlap at a magnification of ×11,000. Viral particles in the nucleus, perinuclear space, or cytoplasm or outside the cell (extracellular) were counted using the Adobe Photoshop CS4 count tool. Statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.0d software. For cellular location (nuclear, perinuclear, cytoplasmic, or extracellular), capsid counts for the three viruses (n = 10 or 11 cells) were analyzed by a Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's tests to compare each mutant to WT virus while correcting for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

A heterologous pRb inactivator complements loss of UL97 in both dermal and lung fibroblasts.

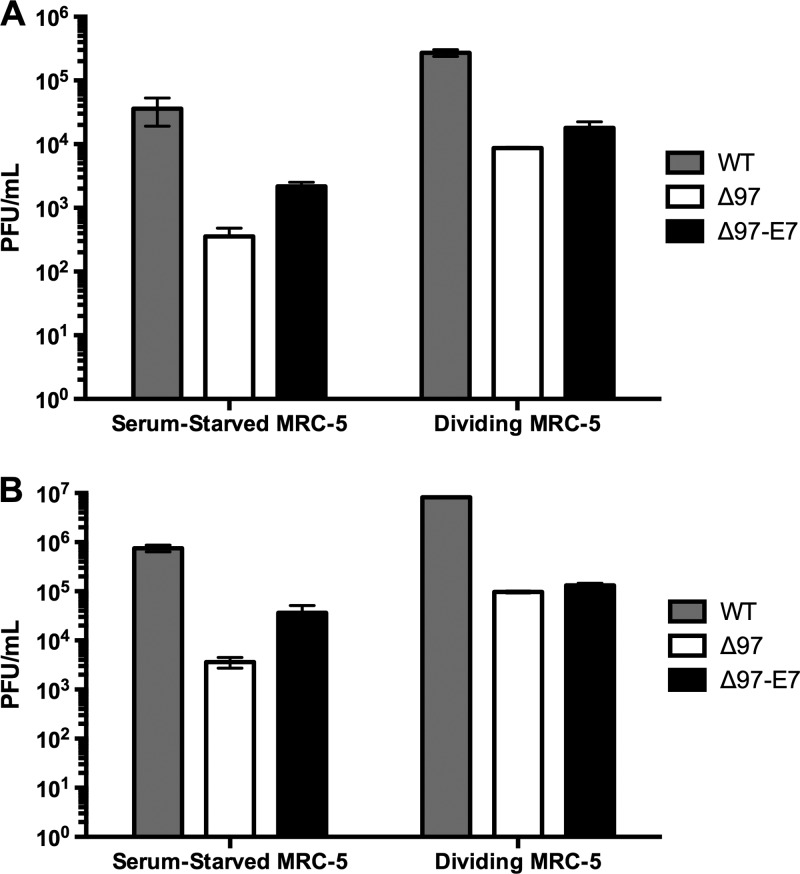

We previously found that a heterologous pRb-inactivating protein, HPV16 E7, could substantially reverse the ≥100-fold replication defect of a UL97-null HCMV deletion mutant (Δ97) in quiescent, serum-starved human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) but had little or no effect on the smaller replication defect in serum-fed, asynchronously dividing HFFs (8). Since inhibitors of UL97 kinase activity have been reported to show different effects on HCMV replication depending on whether assays are performed in lung or dermal fibroblasts (32), we sought to assess the ability of E7 to complement Δ97 replication defects in serum-starved or dividing lung fibroblasts. Under serum-starved conditions, we found that Δ97 exhibited 100- to 200-fold replication defects in MRC-5 lung fibroblasts relative to wild-type AD169rv (two independent experiments are shown in Fig. 1). These defects are similar to what we previously observed in serum-starved HFFs (8). However, we found that the severity of the replication defect in serum-starved HFFs depended on the serum lot (J. P. Kamil and D. M. Coen, data not shown). In an experiment performed in parallel with the one illustrated in Fig. 1A, we found less pronounced defects of Δ97 in serum-starved HFFs (∼60-fold; see Fig. S1A at https://coen.med.harvard.edu), which is consistent with a report indicating a greater effect of a UL97 inhibitor on HCMV replication in lung embryo fibroblasts, such as MRC-5, than in dermal fibroblasts, such as HFFs (32). As was the case in HFFs (see reference 8 and Fig. S1A at the URL mentioned above), expression of E7 substantially reversed the replication defect of Δ97 under serum starvation conditions in MRC-5 cells (∼10-fold in both experiments whose results are shown in Fig. 1), as well as the DNA synthesis defect (∼7.5-fold; see Fig. S2 at https://coen.med.harvard.edu). In serum-fed, asynchronously dividing MRC-5 cells, consistent with our findings in HFFs (see reference 8 and Fig. S1B at https://coen.med.harvard.edu), Δ97 exhibited a smaller defect in virus production relative to WT than in serum-starved cells, and expression of E7 did not complement the loss of UL97 more than ∼2-fold, if at all (Fig. 1). From these experiments, we conclude that the pattern of Δ97 replication defects and complementation by E7-expressing virus, in serum-starved cells versus under serum-fed, dividing-cell conditions, were similar in MRC-5 lung fibroblasts and HFFs. Notably, for both dividing and serum-starved MRC-5, as was true for HFFs (see reference 8 and Fig. S1 at the URL mentioned above), a residual defect in virus production was not reversed by expression of E7 (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Replication of HCMV WT, Δ97, and Δ97-E7 viruses in MRC-5 cells under different growth conditions. Serum-starved (maintained in medium containing 0.1% FBS 72 h prior to infection) or dividing (maintained in medium containing 10% FBS) MRC-5 lung fibroblasts were infected with wild-type HCMV (WT), UL97-null HCMV (Δ97), or UL97-null HCMV expressing HPV16 E7 (Δ97-E7) at an MOI of 1 in two independent experiments (A and B). One experiment was performed in parallel with the immunofluorescence (IF) experiments (A) and one in parallel with the EM experiments (B). Titers (PFU/ml) were determined in triplicate at 120 h postinfection. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

Lamin A/C phosphorylation correlates with UL97 expression.

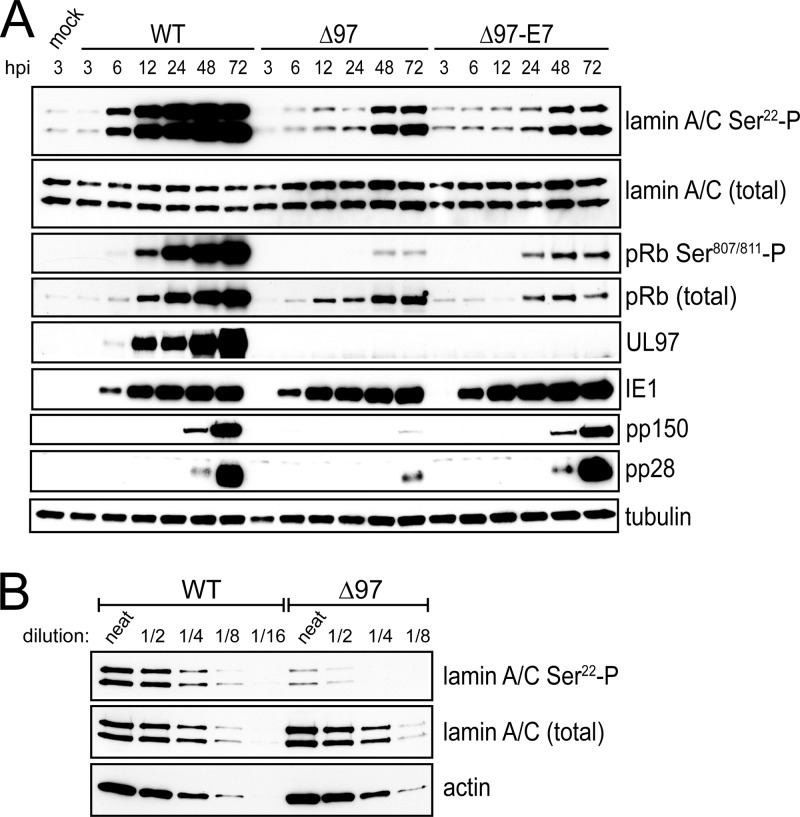

We asked whether at least part of the remaining defect in virus production by the E7-expressing virus was due to a defect in nuclear egress. An important step in nuclear egress is disruption of the nuclear lamina, which, during HCMV infection, requires UL97 (6, 9, 21). In particular, UL97 is required for WT levels of phosphorylation of the nuclear lamina component lamin A/C on serine 22 (Ser22) (6). In dividing, uninfected cells, this residue is crucial for lamina dissolution following CDK1/cyclin B phosphorylation during mitosis (6, 20). Ser22 can be phosphorylated by purified UL97 in vitro (6, 20), suggesting that UL97 directly phosphorylates it during infection to mediate disruption of the nuclear lamina. However, an alternative hypothesis is that UL97-dependent Ser22 phosphorylation during infection is due to UL97 phosphorylation of pRb, which induces the expression of CDK1 (22–24). To address these hypotheses, we analyzed mock-infected MRC-5 cells and cells infected with WT, Δ97, and Δ97-E7 by Western blotting with various antibodies, including an antibody that recognizes Ser22-phosphorylated lamin A/C. To increase the sensitivity of our assays, the cells in these experiments were serum starved for 72 h prior to infection to decrease levels of CDK activity and thus levels of phosphorylated Ser22. Indeed, mock-infected MRC-5 cells showed low levels of Ser22 phosphorylation (Fig. 2A). Upon infection with WT HCMV, no increase in phosphorylation of Ser22 was detected at 3 hpi, but a marked increase was observed by 6 hpi with further increases through 72 hpi when the experiment was terminated (Fig. 2A). Similarly, UL97 expression was not detected at 3 hpi but was detected by 6 hpi and increased through the end of the experiment. Thus, UL97 expression correlated with increases in phosphorylation of Ser22. Levels of lamin A/C were consistent throughout the experiment (Fig. 2A). In cells infected with either Δ97 or Δ97-E7, meaningful increases in Ser22 phosphorylation were not observed until 48 hpi, more than 40 h later than in WT-infected cells (Fig. 2A). Starting at 48 hpi, we detected UL97-independent phosphorylation of lamin A/C, but even at these times, WT-infected cells displayed higher levels of lamin A/C Ser22 phosphorylation than UL97-null viruses. Comparing a dilution series of lysates prepared at 12 hpi, there was at least 4-fold more Ser22-phosphorylated lamin A/C in WT-infected cells than in Δ97-infected cells (Fig. 2B). This result confirms and extends our previous findings, in which iTraq quantitative mass spectrometry found 2- to 4-fold-higher levels of Ser22 phosphorylation in lamin A/C isolated from WT-infected cells than from UL97 mutant-infected cells at 72 hpi (6). The quantitative differences between our present and previous results likely reflect UL97-independent induction of Ser22 phosphorylation at late times.

Fig 2.

Kinetics of lamin A/C phosphorylation during infection. (A) Serum-starved MRC-5 cells were infected with the indicated viruses, and lysates collected at the indicated time points were analyzed by Western blotting for reactivity to a phosphospecific antibody that recognizes lamin A/C when phosphorylated at serine 22 (lamin A/C Ser22-P). The blots were also probed using antibodies to lamin A/C (lamin A/C total), pRb phosphorylated at serines 807 and 811 (pRb Ser807/811-P), pRb (pRb total), UL97, the 72-kDa viral immediate early protein-1 (IE1), two viral late proteins (pp150 and pp28), and beta-tubulin (tubulin) as a loading control. (B) Fold differences in levels of lamin A/C phosphorylated at Ser22 in 12 hpi lysates of WT and Δ97 were estimated by comparing the signal intensities from Ser22 phosphospecific antibody (lamin A/C Ser22-P) immunoreactivity on Western blots with those of undiluted (neat) lysates alongside the indicated dilutions. Membranes were also probed with antibodies to lamin A/C (lamin A/C total) and beta-actin (actin) as loading controls. The lamin A/C Ser22-P signal intensity of undiluted (neat) Δ97 lysate was weaker than that of a 4-fold dilution (1/4) of WT lysate but slightly stronger than that of an 8-fold dilution (1/8) of WT lysate.

As noted above, Δ97-E7 infection did not appear to increase phosphorylation of lamin A/C at Ser22 above that seen in Δ97-infected cells (Fig. 2A). However, as expected, Δ97-E7 infection resulted in a dramatic reduction in pRb levels, as monitored using an antibody to pRb (pRb total), compared to those in Δ97- or WT-infected cells (Fig. 2A). Importantly, as previously observed (8, 15, 16), in WT-infected cells there was a substantial increase in levels of phosphorylated pRb (Fig. 2A) relative to those in mock-infected cells, Δ97-infected cells, and Δ97-E7-infected cells, here monitored using an antibody specific for pRb dually phosphorylated at Ser807 and Ser811 (pRb Ser807/811-P). Moreover, the time course of phosphorylation of pRb, which is an established substrate of UL97 (15, 16), in WT-infected cells correlated with that of lamin A/C, consistent with both these proteins being direct substrates of UL97 (Fig. 2A). Also, there was substantially higher expression of the late viral proteins pp150 and pp28 in cells infected with WT or Δ97-E7 than in cells infected with Δ97 (Fig. 2A), consistent with the DNA synthesis phenotypes of these viruses (see reference 8 and Fig. S2 at https://coen.med.harvard.edu). Thus, phosphorylation of lamin A/C at Ser22 depends on UL97, especially at early times, and correlates with the kinetics of UL97 expression, while HPV16 E7 does not rescue the loss of UL97 for phosphorylation of lamin A/C in HCMV-infected cells. These results are consistent with direct phosphorylation of lamin A/C on Ser22 by UL97 in infected cells.

Virus-induced alterations in the nuclear lamina are not restored by expression of E7.

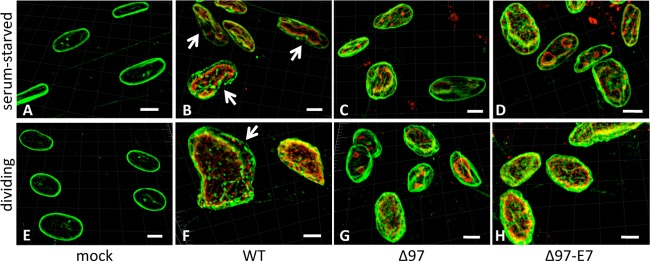

We have previously found that phosphorylation of lamin A/C on Ser22 is associated with disruption of the nuclear lamina in HCMV-infected cells and that both depend on UL97 (6). However, that did not demonstrate that phosphorylation on Ser22 is necessary and sufficient for disruption of nuclear lamina in HCMV-infected cells or that inactivation of pRb by UL97 might suffice for that disruption. Therefore, we investigated whether heterologous pRb inactivation by HPV16 E7 can replace UL97 for this disruption. To this end, we mock infected or infected quiescent or dividing MRC-5 cells with WT, Δ97, or Δ97-E7 virus. At 96 hpi, we stained the cells with anti-lamin A/C antibodies and analyzed the stained cells using spinning disk confocal microscopy. To confirm infection and highlight the nuclei, we costained with antibody against UL44, a viral DNA polymerase subunit that localizes to the periphery of viral replication compartments (the sites of viral DNA synthesis) within the nucleus (6, 33, 34). As a control, we also analyzed infections of dividing HFFs, to compare our results with those in our previous study (9). For this experiment and the electron microscopy experiment below, we present our data with HFF cells, which confirm our earlier findings (6, 9), in the form of supplemental figures (see Fig. S3 and S4 at https://coen.med.harvard.edu).

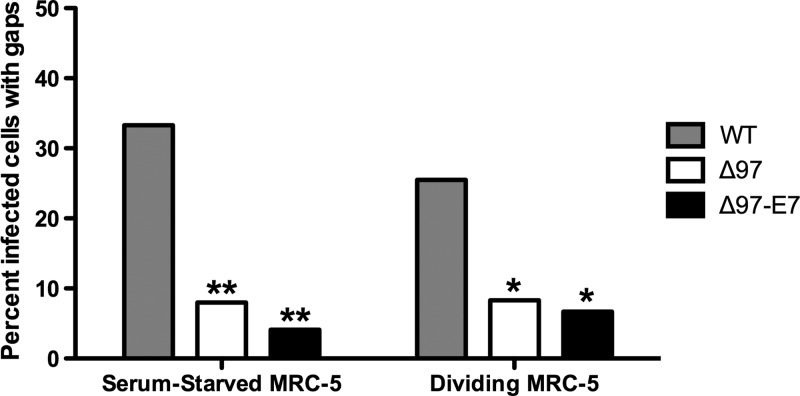

Examples of results with MRC-5 cells are shown in Fig. 3. As observed with dividing HFF cells (see reference 6 and Fig. S3 at https://coen.med.harvard.edu), confocal images of mock-infected MRC-5 cells revealed oval and relatively uniform lamin A/C staining patterns (Fig. 3A and E). In strong contrast, as seen previously and concurrently with HFF cells (see reference 6 and Fig. S3 at the URL mentioned above), WT-infected MRC-5 cells exhibited deformed and less uniform patterns of lamin A/C staining, with areas of thinning and visible gaps in roughly one-quarter to one-third of the cells (Fig. 3B and F and Fig. 4). In cells infected with either Δ97 or Δ97-E7, lamin A/C staining was more akin to that in mock-infected cells, being less deformed and more uniform (Fig. 3C, D, G, and H). We examined numerous cells for each infection condition and found that gaps were 3- to 9-fold less frequent in cells infected with either Δ97 or Δ97-E7 than in cells infected with WT, and these differences were statistically significant (Fig. 4).

Fig 3.

Gaps in nuclear lamina. MRC-5 cells were mock infected (A and E) or infected with WT HCMV (B and F), mutant Δ97 (C and G), or mutant Δ97-E7 (D and H) at an MOI of 3 under serum-starved (A to D) or dividing (E to H) conditions. At 96 hpi, cells were stained for UL44 (red) and lamin A/C (green). Serial optical sections were acquired by confocal microscopy, and 3-D reconstruction images are shown. Gaps in lamin A/C staining in WT-infected cells in panels B and F are shown by the white arrows. White bars indicate the distance in the images that corresponds to 40 μm.

Fig 4.

Quantification of gaps in the nuclear lamina. Serial optical sections from the experiment illustrated in Fig. 3 were collected and used to create three-dimensional reconstruction images to determine the number of cells containing gaps for each combination of cell conditions (serum-starved or dividing) and viruses (WT, Δ97, and Δ97-E7). Differences between a mutant and WT virus were analyzed by Fisher's exact test. Significant differences (P = 0.0041 and 0.0089, comparing WT virus to Δ97 and Δ97-E7, respectively, in dividing cells) are indicated with single asterisks, and highly significant differences (P < 0.0001, comparing WT virus to either of the two mutant viruses in serum-starved cells) are indicated with double asterisks.

In most WT-infected cells, anti-UL44 antibody stained the periphery of large replication compartments (Fig. 3B and F), consistent with efficient viral DNA synthesis. Interestingly, in some cells infected with any of the viruses (examples can be seen in Fig. 3C, D, and G), anti-UL44 antibody stained relatively small replication compartments, consistent with less-efficient DNA synthesis. However, large compartments were present in the vast majority of serum-starved or dividing cells infected with WT virus or Δ97-E7 but not in the majority of serum-starved cells infected with Δ97, consistent with the DNA synthesis defect of this mutant (see Table S1 at https://coen.med.harvard.edu).

From these experiments, we conclude that expression of a pRb-inactivating protein does not complement a UL97-null mutant for disruptions of the nuclear lamina.

Expression of HPV16 E7 fails to rescue the nuclear egress defect of UL97-null HCMV.

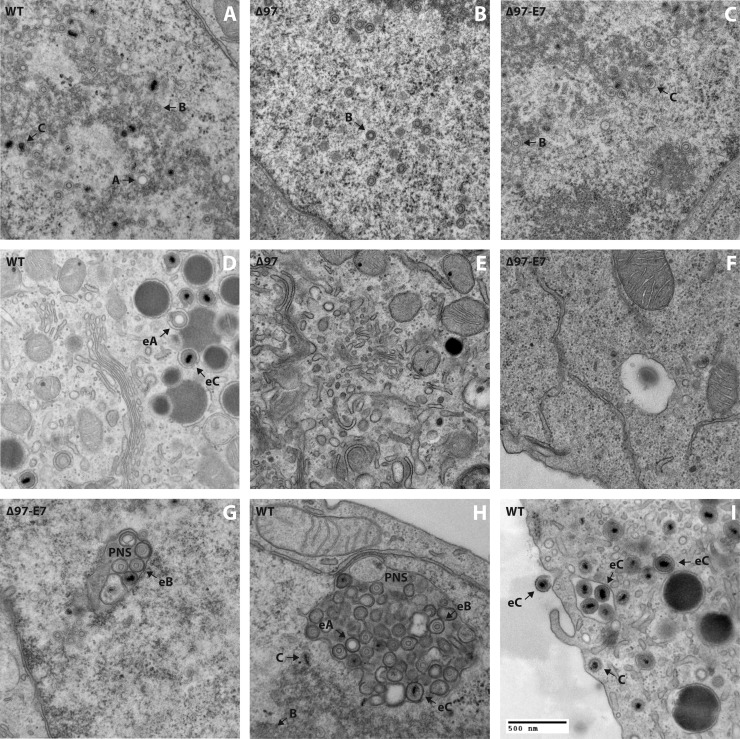

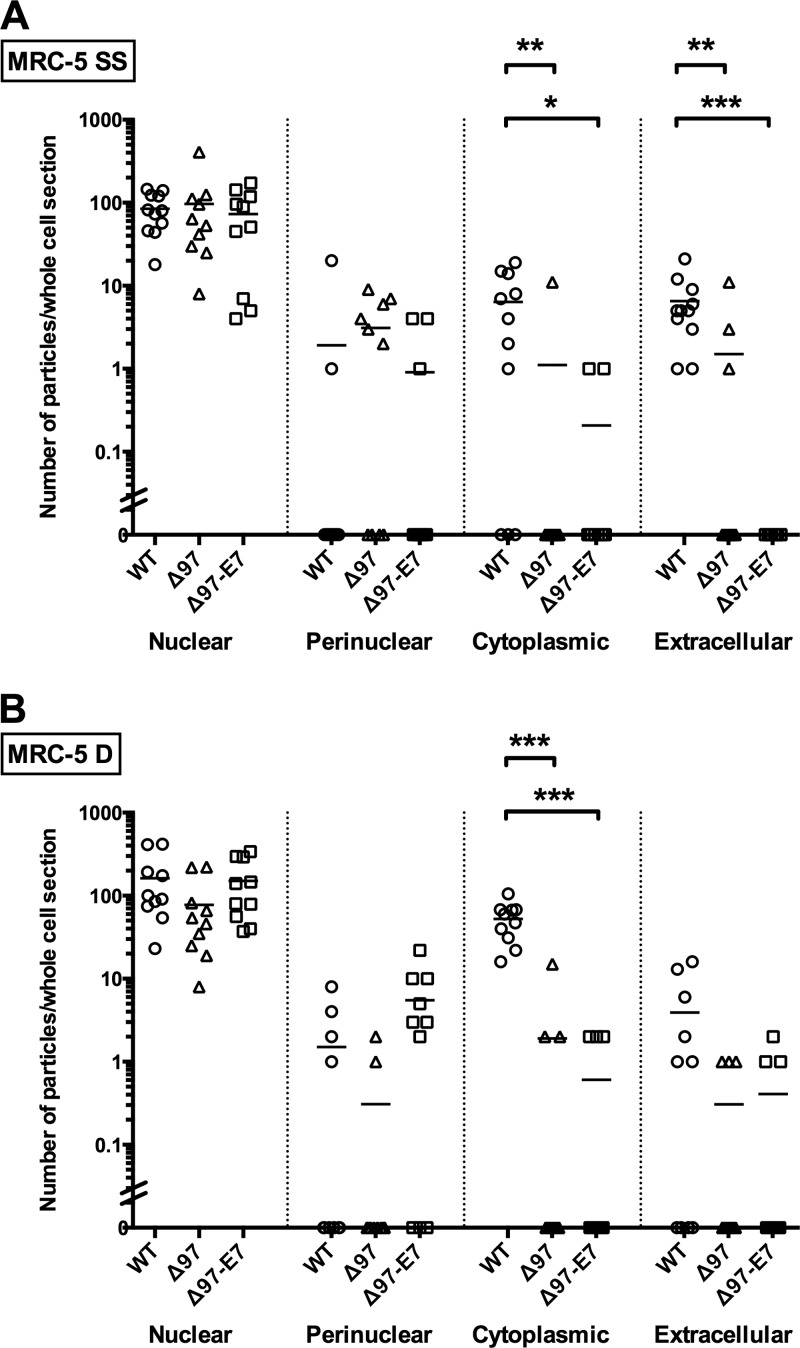

To directly assess whether E7 expression can restore efficient nuclear egress to a UL97-null mutant, we conducted transmission electron microscopy (EM) analysis of serum-fed, dividing versus serum-starved, quiescent MRC-5 cells infected with WT, Δ97, or Δ97-E7 virus (examples of images are shown in Fig. 5). We also included infections in dividing HFFs since we had previously done EM analyses of nuclear egress using those conditions (9). We randomly selected sections in which we could visualize cells “in their entirety,” meaning that each section included the nucleus and cytoplasm, and analyzed 10 or 11 of these whole-cell sections for each virus-cell condition. In each whole-cell section, virus particles were scored as being in the nucleus (Fig. 5A to C), in the perinuclear space (seen only occasionally [Fig. 5G and H]), in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5D to F), or outside the cell (Fig. 5I) and counted (Fig. 6 shows MRC-5 results; see Fig. S4 for HFF results at https://coen.med.harvard.edu).

Fig 5.

Electron microscopy analysis. Dividing MRC-5 cells (A to F and I), dividing HFF cells (G), or serum-starved MRC-5 cells (H) were infected (MOI = 1) with WT (A, D, H, I), Δ97 (B, E), or Δ97-E7 (C, F, G) and processed for electron microscopy at 72 hpi (dividing cells) or 96 hpi (serum-starved cells). (A to C) Images of the nuclei of infected cells; (D to F) images of the cytoplasm of infected cells; (G and H) images of particles in the space between the inner and outer nuclear membranes (perinuclear space [PNS]); (I) image that includes an extracellular particle and a bar indicating the distance in the images that corresponds to 500 nm. In panels A to D and G to I, arrows point to nonenveloped capsid forms (marked by letters A, B, and C) and enveloped capsid forms (eA, eB, or eC).

Fig 6.

Viral particle distributions. Ten or eleven thin sections representing whole serum-starved (SS) MRC-5 cells (A) or dividing MRC-5 cells (MRC-5 D) (B) from the experiment illustrated in Fig. 5, infected with each of the three viruses, as indicated, were analyzed for the number of viral particles that were nuclear, perinuclear, cytoplasmic, and extracellular. The mean number of particles in each condition is indicated with a horizontal line. For each location, the data were analyzed by a Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's tests to compare each mutant to WT virus while correcting for multiple comparisons. Significant differences are shown by asterisks above brackets: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Under all conditions, WT, Δ97, and Δ97-E7 infections showed roughly similar levels of nucleocapsids in the nucleus (Fig. 5A to C), i.e., ∼80 to ∼160 nucleocapsids per whole-cell section on average (Fig. 6; see Fig. S4 at the URL mentioned above). Viral particles were found in the cytoplasm and outside nearly all WT-infected cells examined (Fig. 6; see Fig. S4 at the URL mentioned above). In contrast, no cytoplasmic or extracellular particles were found in most cells infected with Δ97 or Δ97-E7 (Fig. 6; see Fig. S4 at the URL mentioned above). Moreover, the mean numbers of particles found in the cytoplasm of mutant-infected cells were significantly reduced relative to those in WT-infected cells in both serum-starved (6-fold for Δ97 and 30-fold for Δ97-E7) and dividing cells (30-fold for Δ97 and 90-fold for Δ97-E7) (Fig. 6), as observed for dividing HFF cells previously (9) and concurrently (see Fig. S4 at the URL mentioned above). Additionally, the numbers of particles found outside serum-starved MRC-5 cells infected with both mutant viruses were significantly lower than those infected with WT (4-fold for Δ97 and >60-fold for Δ97-E7) (Fig. 6). Significant reductions in extracellular particles were also observed in dividing HFF cells infected by the mutant viruses (see Fig. S4 at the URL mentioned above). There were few, if any, meaningful differences in the numbers of cytoplasmic and extracellular particles following infection with Δ97 or Δ97-E7 in either serum-starved or dividing MRC-5 cells (Fig. 6). If anything, there were more such particles in cells infected with Δ97 than in cells infected with Δ97-E7. Therefore, expression of a heterologous pRb inactivator, HPV16 E7, failed to rescue nuclear egress during UL97-null mutant infection either of serum-starved, quiescent or of serum-fed, dividing MRC-5 cells.

DISCUSSION

Phosphorylation is a crucial posttranslational modification in eukaryotes, affecting a wide and varied array of processes. It is, therefore, not surprising that HCMV mutants that are null for the virus's sole conventional protein kinase, UL97, show defects in multiple processes during infection (3–6, 8, 9, 15, 16, 35). We sought to address whether two of these processes—DNA synthesis and nuclear egress—involve distinct UL97 protein kinase substrates. In particular, we asked whether phosphorylation and inactivation of pRb by UL97, which is important for viral DNA synthesis (8), is also important for nuclear egress. This question arose because inactivation of pRb is known to induce CDK1, which ordinarily phosphorylates lamin A/C on Ser22 to promote disassembly of the nuclear lamina during mitosis. Phosphorylation of lamin A/C and disruption of the nuclear lamina also occur during herpesvirus nuclear egress. Although we had previously shown UL97-dependent phosphorylation of lamin A/C on Ser22 both in vitro and during infection (6), the role of UL97 in nuclear egress might merely represent an indirect effect of pRb inactivation by UL97. However, in this study, we found that the kinetics of lamin A/C Ser22 phosphorylation during WT HCMV infection correlate with UL97 expression, consistent with a direct role of UL97, and are severely delayed in UL97 mutants, even in mutant Δ97-E7, which expresses the pRb-inactivating protein, HPV16 E7. Similarly, disruptions of the nuclear lamina that occur during WT infection and nuclear egress are markedly reduced in UL97 mutants, even in mutant Δ97-E7. Thus, a major block in the replication of the E7-expressing UL97-null mutant is nuclear egress.

We conclude that UL97 phosphorylation of pRb plays little if any role during nuclear egress. Rather, our results, combined with those of previous studies (6, 9, 21, 36, 37), favor the notion that UL97 directly phosphorylates lamin A/C, promoting the disruption of nuclear lamina. Such disruption, in turn, would permit nucleocapsids to gain access to the inner nuclear membrane for subsequent steps of nuclear egress. However, we cannot rule out roles for phosphorylation of lamin A/C other than disrupting nuclear lamina in promoting nuclear egress. Such potential other roles are brought to mind by the recent finding of a protein kinase-requiring cellular process akin to herpesvirus nuclear egress, in which the Drosophila homolog of lamin A/C forms granules with ribonucleoprotein complexes that localize to the inner nuclear membrane (38). Additionally, we cannot exclude the possibility that UL97 has roles in nuclear egress other than phosphorylation of lamin A/C. We are currently investigating these possibilities.

Although UL97 is clearly required for increases in lamin A/C Ser22 phosphorylation during the first 48 h of WT infection, we observed UL97-independent increases in lamin A/C Ser22 phosphorylation at later times (48 to 72 hpi) during infection. The most likely explanation for this phosphorylation is HCMV-induced CDK1 activity. Levels of CDK1 and cyclin B are known to increase during HCMV infection (25–27). Regardless, the UL97-independent phosphorylation of lamin A/C may help explain why UL97 is not absolutely essential for nuclear egress. One might speculate that because nuclear egress is such an important stage during HCMV replication, HCMV may have evolved more than one mechanism (perhaps even somewhat redundant mechanisms) to induce disruption of nuclear lamin polymers. Identification of the viral gene products responsible for these late, UL97-independent increases in lamin A/C phosphorylation should provide further insights into viral nuclear egress.

Our results, combined with previous work (2, 3, 8, 9), indicate that UL97 is required for efficient viral DNA synthesis in quiescent cells and for efficient nuclear egress in both quiescent and dividing cells. These two stages are crucial for production of infectious HCMV. Do the effects of UL97 mutations on DNA synthesis and nuclear egress account for the effects of these mutations on the yield of infectious virus? Before addressing this question, we note that in most whole-cell sections infected with mutant viruses, we found no cytoplasmic or extracellular particles, so that average values for nuclear egress defects reflect particles counted from very few cells. Additionally, we observed considerable variability in counts of these particles from one whole-cell section to another, which might indicate that UL97 mutations could have greater effects on nuclear egress in some cells and smaller effects in others.

Nevertheless, with these caveats in mind, we have previously found that, on average, the nuclear egress defect of Δ97 appears to largely account for the defect in virus yield in dividing HFF cells (9), and we have confirmed this result here. In dividing MRC-5 cells, we found that Δ97 exhibits an ∼30-fold defect in nuclear egress on average. In a yield assay performed in parallel with the EM nuclear egress study, we found an ∼80-fold defect in production of infectious virus. (An independent assay showed an ∼30-fold defect in production of infectious virus). Thus, the nuclear egress defect appears to account for all but a few-fold of the yield defect. It seems plausible that the modest viral DNA synthesis defects in dividing cells exhibited by Δ97 (9; J. P. Kamil, data not shown) account for the remaining defect in production of infectious virus in these cells. Consistent with this notion, the nuclear egress defect of Δ97-E7 appears to fully account for its yield defect in dividing MRC-5 cells, while this virus exhibits little if any DNA synthesis defect in these cells (data not shown).

In quiescent MRC-5 cells, we found that Δ97 exhibited an ∼7.5-fold defect in viral DNA synthesis and an ∼6-fold defect, on average, in nuclear egress. Aside from the caveats mentioned above, we do not know whether these two effects would be simply multiplicative in their impact on viral yield. Assuming that they would be, these effects do not appear to account for the 100- to 200-fold defect of this mutant in virus yield, especially as the 200-fold defect was observed in an experiment conducted in parallel with the EM experiment assessing nuclear egress. This raises the possibility that there are UL97-dependent steps of viral replication other than DNA synthesis and nuclear egress that are important for production of infectious virus in quiescent MRC-5 cells. Possible candidates for such steps include late events in virus assembly and morphogenesis (4, 5, 35). Interestingly, Δ97-E7 replicated to 6- to 10-fold-higher titers than Δ97 in quiescent MRC-5 cells, consistent with rescue of the ∼10-fold viral DNA synthesis defect of Δ97 by E7. However, the residual defect in yield of Δ97-E7 in quiescent MRC-5 cells (∼20-fold) can be fully explained by its nuclear egress defect (on average ∼30-fold). This further raises the possibility that pRb phosphorylation by UL97 is important for steps other than DNA synthesis, which are in turn important for production of infectious virus in quiescent MRC-5 cells. Indeed, Prichard et al. have proposed that pRb phosphorylation by UL97 is important to counteract the formation of nuclear aggresomes that are hypothesized to interfere with virus production (16). E7-expressing, UL97-null viruses should be valuable for exploring these possibilities. Regardless, our results raise the possibility that UL97 phosphorylation of just two substrates—pRb and lamin A/C—may account for most of the contribution of this enzyme in promoting the production of infectious HCMV strain AD169 in fibroblasts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Wolfram Brune for plasmid pLXSN-19K, to Tom Shenk for antibody to IE1-72, to Bill Britt for monoclonal antibody to pp150, and to Jim Alwine for alerting us to the antibody that recognizes lamin A/C phosphorylated on serine 22. We gratefully acknowledge that immunofluorescence microscopy data were acquired and analyzed in the Nikon Imaging Center at Harvard Medical School.

This project was supported by NIH grants R01 AI026077 (N.I.R., J.P.K., M.S., J.M.P., and D.M.C), P20 GM103433 (D.W. and J.P.K.), R01 HL32854 (A.L. and D.E.G.), and R01 HL116327 and by an innovation award from the Harvard Medical School-Portugal Program in Translational Research and Information Grant (A.L. and D.E.G.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 20 February 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Prichard MN, Gao N, Jairath S, Mulamba G, Krosky P, Coen DM, Parker BO, Pari GS. 1999. A recombinant human cytomegalovirus with a large deletion in UL97 has a severe replication deficiency. J. Virol. 73:5663–5670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Biron KK, Harvey RJ, Chamberlain SC, Good SS, Smith AA, III, Davis MG, Talarico CL, Miller WH, Ferris R, Dornsife RE, Stanat SC, Drach JC, Townsend LB, Koszalka GW. 2002. Potent and selective inhibition of human cytomegalovirus replication by 1263W94, a benzimidazole L-riboside with a unique mode of action. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2365–2372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wolf DG, Courcelle CT, Prichard MN, Mocarski ES. 2001. Distinct and separate roles for herpesvirus-conserved UL97 kinase in cytomegalovirus DNA synthesis and encapsidation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:1895–1900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Azzeh M, Honigman A, Taraboulos A, Rouvinski A, Wolf DG. 2006. Structural changes in human cytomegalovirus cytoplasmic assembly sites in the absence of UL97 kinase activity. Virology 354:69–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goldberg MD, Honigman A, Weinstein J, Chou S, Taraboulos A, Rouvinski A, Shinder V, Wolf DG. 2011. Human cytomegalovirus UL97 kinase and nonkinase functions mediate viral cytoplasmic secondary envelopment. J. Virol. 85:3375–3384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hamirally S, Kamil JP, Ndassa-Colday YM, Lin AJ, Jahng WJ, Baek MC, Noton S, Silva LA, Simpson-Holley M, Knipe DM, Golan DE, Marto JA, Coen DM. 2009. Viral mimicry of Cdc2/cyclin-dependent kinase 1 mediates disruption of nuclear lamina during human cytomegalovirus nuclear egress. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000275 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kamil JP, Coen DM. 2007. Human cytomegalovirus protein kinase UL97 forms a complex with the tegument phosphoprotein pp65. J. Virol. 81:10659–10668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kamil JP, Hume AJ, Jurak I, Munger K, Kalejta RF, Coen DM. 2009. Human papillomavirus 16 E7 inactivator of retinoblastoma family proteins complements human cytomegalovirus lacking UL97 protein kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:16823–16828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Krosky PM, Baek MC, Coen DM. 2003. The human cytomegalovirus UL97 protein kinase, an antiviral drug target, is required at the stage of nuclear egress. J. Virol. 77:905–914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baek MC, Krosky PM, Pearson A, Coen DM. 2004. Phosphorylation of the RNA polymerase II carboxyl-terminal domain in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells and in vitro by the viral UL97 protein kinase. Virology 324:184–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Krosky PM, Baek MC, Jahng WJ, Barrera I, Harvey RJ, Biron KK, Coen DM, Sethna PB. 2003. The human cytomegalovirus UL44 protein is a substrate for the UL97 protein kinase. J. Virol. 77:7720–7727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Silva LA, Strang BL, Lin EW, Kamil JP, Coen DM. 2011. Sites and roles of phosphorylation of the human cytomegalovirus DNA polymerase subunit UL44. Virology 417:268–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tran K, Kamil JP, Coen DM, Spector DH. 2010. Inactivation and disassembly of the anaphase-promoting complex during human cytomegalovirus infection is associated with degradation of the APC5 and APC4 subunits and does not require UL97-mediated phosphorylation of Cdh1. J. Virol. 84:10832–10843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moreno S, Nurse P. 1990. Substrates for p34cdc2: in vivo veritas? Cell 61:549–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hume AJ, Finkel JS, Kamil JP, Coen DM, Culbertson MR, Kalejta RF. 2008. Phosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein by viral protein with cyclin-dependent kinase function. Science 320:797–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Prichard MN, Sztul E, Daily SL, Perry AL, Frederick SL, Gill RB, Hartline CB, Streblow DN, Varnum SM, Smith RD, Kern ER. 2008. Human cytomegalovirus UL97 kinase activity is required for the hyperphosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein and inhibits the formation of nuclear aggresomes. J. Virol. 82:5054–5067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boyer SN, Wazer DE, Band V. 1996. E7 protein of human papilloma virus-16 induces degradation of retinoblastoma protein through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Cancer Res. 56:4620–4624 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dyson N, Howley PM, Munger K, Harlow E. 1989. The human papilloma virus-16 E7 oncoprotein is able to bind to the retinoblastoma gene product. Science 243:934–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van Zeijl M, Fairhurst J, Baum EZ, Sun L, Jones TR. 1997. The human cytomegalovirus UL97 protein is phosphorylated and a component of virions. Virology 231:72–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heald R, McKeon F. 1990. Mutations of phosphorylation sites in lamin A that prevent nuclear lamina disassembly in mitosis. Cell 61:579–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Milbradt J, Webel R, Auerochs S, Sticht H, Marschall M. 2010. Novel mode of phosphorylation-triggered reorganization of the nuclear lamina during nuclear egress of human cytomegalovirus. J. Biol. Chem. 285:13979–13989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dalton S. 1992. Cell cycle regulation of the human cdc2 gene. EMBO J. 11:1797–1804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Furukawa Y, Terui Y, Sakoe K, Ohta M, Saito M. 1994. The role of cellular transcription factor E2F in the regulation of cdc2 mRNA expression and cell cycle control of human hematopoietic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 269:26249–26258 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tommasi S, Pfeifer GP. 1995. In vivo structure of the human cdc2 promoter: release of a p130-E2F-4 complex from sequences immediately upstream of the transcription initiation site coincides with induction of cdc2 expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:6901–6913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Salvant BS, Fortunato EA, Spector DH. 1998. Cell cycle dysregulation by human cytomegalovirus: influence of the cell cycle phase at the time of infection and effects on cyclin transcription. J. Virol. 72:3729–3741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jault FM, Jault JM, Ruchti F, Fortunato EA, Clark C, Corbeil J, Richman DD, Spector DH. 1995. Cytomegalovirus infection induces high levels of cyclins, phosphorylated Rb, and p53, leading to cell cycle arrest. J. Virol. 69:6697–6704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hertel L, Mocarski ES. 2004. Global analysis of host cell gene expression late during cytomegalovirus infection reveals extensive dysregulation of cell cycle gene expression and induction of pseudomitosis independent of US28 function. J. Virol. 78:11988–12011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jurak I, Brune W. 2006. Induction of apoptosis limits cytomegalovirus cross-species infection. EMBO J. 25:2634–2642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hobom U, Brune W, Messerle M, Hahn G, Koszinowski UH. 2000. Fast screening procedures for random transposon libraries of cloned herpesvirus genomes: mutational analysis of human cytomegalovirus envelope glycoprotein genes. J. Virol. 74:7720–7729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Harlow E, Lane D. 1999. Using antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nogalski MT, Chan G, Stevenson EV, Gray S, Yurochko AD. 2011. Human cytomegalovirus-regulated paxillin in monocytes links cellular pathogenic motility to the process of viral entry. J. Virol. 85:1360–1369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chou S, Van Wechel LC, Marousek GI. 2006. Effect of cell culture conditions on the anticytomegalovirus activity of maribavir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2557–2559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Strang BL, Boulant S, Chang L, Knipe DM, Kirchhausen T, Coen DM. 2012. Human cytomegalovirus UL44 concentrates at the periphery of replication compartments, the site of viral DNA synthesis. J. Virol. 86:2089–2095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Strang BL, Boulant S, Kirchhausen T, Coen DM. 2012. Host cell nucleolin is required to maintain the architecture of human cytomegalovirus replication compartments. mBio 31:e00301–11 doi:10.1128/mBio.00301-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Prichard MN, Britt WJ, Daily SL, Hartline CB, Kern ER. 2005. Human cytomegalovirus UL97 kinase is required for the normal intranuclear distribution of pp65 and virion morphogenesis. J. Virol. 79:15494–15502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marschall M, Marzi A, aus dem Siepen P, Jochmann R, Kalmer M, Auerochs S, Lischka P, Leis M, Stamminger T. 2005. Cellular p32 recruits cytomegalovirus kinase pUL97 to redistribute the nuclear lamina. J. Biol. Chem. 280:33357–33367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kuny CV, Chinchilla K, Culbertson MR, Kalejta RF. 2010. Cyclin-dependent kinase-like function is shared by the beta- and gamma- subset of the conserved herpesvirus protein kinases. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001092 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Speese SD, Ashley J, Jokhi V, Nunnari J, Barria R, Li Y, Ataman B, Koon A, Chang YT, Li Q, Moore MJ, Budnik V. 2012. Nuclear envelope budding enables large ribonucleoprotein particle export during synaptic Wnt signaling. Cell 149:832–846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]