Abstract

Infections with human coronavirus EMC (HCoV-EMC) are associated with severe pneumonia. We demonstrate that HCoV-EMC resembles severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in productively infecting primary and continuous cells of the human airways and in preventing the induction of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3)-mediated antiviral alpha/beta interferon (IFN-α/β) responses. However, HCoV-EMC was markedly more sensitive to the antiviral state established by ectopic IFN. Thus, HCoV-EMC can utilize a broad range of human cell substrates and suppress IFN induction, but it does not reach the IFN resistance of SARS-CoV.

TEXT

In September 2012, a novel human coronavirus (HCoV) was isolated in association with two cases of an acute, rapidly deteriorating respiratory illness that is often connected with kidney failure (1–3). As of February 2013, 12 infections with a fatality rate of approximately 40% were reported (4, 5). The coronavirus, which was termed HCoV-EMC (EMC for Erasmus Medical Center), is phylogenetically related to the causative agent of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), SARS-CoV (3, 6). The alarming parallels both in terms of taxonomy and of pathogenesis sparked the fear that HCoV-EMC could cause an epidemic similar to SARS-CoV, which in 2003 had infected more than 8,000 people, killed 800, and caused worldwide economic damages in the range of 100 billion U.S. dollars (7).

SARS-CoV is capable of propagating in primary cells and continuous cell lines of the human airway epithelium (8, 9). Moreover, SARS-CoV efficiently suppresses antiviral innate immune responses, allowing it to spread rapidly in the host (10, 11). Here, we compared these phenotypic features of HCoV-EMC and SARS-CoV in order to obtain a first assessment of the pathogenic potential of the novel human coronavirus.

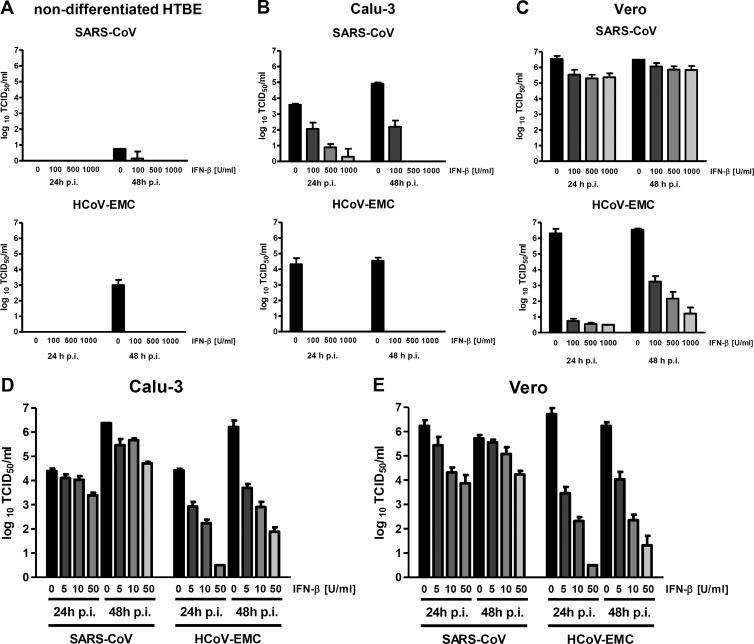

First, we tested the ability of HCoV-EMC to replicate in differentiated cultures of human tracheobronchial epithelial cells (HTBE), an established primary cell model of the human airway epithelium consisting of polarized and pseudostratified ciliated, secretory, and basal cells (12). These cells were grown on 12-mm Transwell permeable membrane supports (Costar) and were fed from the basolateral side with serum-free medium containing hormones and growth factors, whereas the apical side remained exposed to air (air-liquid interface conditions). The mucins that accumulated over time on the apical side of the cultures were removed by washing the cultures 10 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Then, the cultures were inoculated with either SARS-CoV or HCoV-EMC at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1 to enable multistep growth. Infection was conducted by incubating the apical sides of the cultures with 200 μl of viral dilutions in DMEM, and the inoculum was removed 1 h later (13, 14). The cultures were then maintained at 37°C under air-liquid interface conditions. To study the viral growth kinetics, progeny viruses were collected at 24, 48, and 72 h postinfection (p.i.) from both the apical and basolateral sides of the Transwell supports. Material from the apical side was harvested after incubating the cells with 300 μl of DMEM for 30 min. From the basolateral side, 100 μl of the maintenance medium was collected. Virus titers were determined by a 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) assay in Vero cells. Both coronaviruses were able to propagate in differentiated HTBE cultures and were released exclusively from the apical side (Fig. 1). While SARS-CoV replicated slightly faster in the beginning, HCoV-EMC reached a titer similar to the SARS-CoV titer at 72 h p.i. Thus, HCoV-EMC closely resembles SARS-CoV in the ability to replicate in differentiated primary cells of the human airway epithelium.

Fig 1.

Virus multiplication in differentiated cultures of human tracheobronchial epithelial cells. Differentiated HTBE cultures grown on Transwell permeable membrane supports under air-liquid interface conditions were apically inoculated with SARS-CoV strain FFM-1 (34) or the HCoV-EMC isolate (3) at an MOI of 0.1. Virus yields from the apical and basolateral sides were determined at 24, 48, and 72 h p.i. by a TCID50 assay. Mean values plus standard deviations (error bars) of 3 replicate experiments are shown.

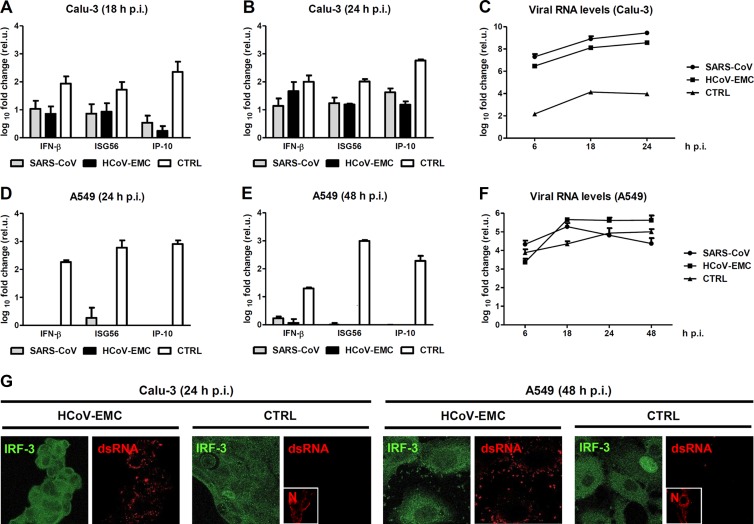

An important hallmark of virulence is the extent to which viruses are able to cope with the antiviral type I interferon (alpha/beta interferon [IFN-α/β]) system, a major part of the innate immune response (15). Type I IFNs are the first cytokines upregulated after infection, stimulating the expression of more than 300 antiviral and immunomodulatory genes (16). Although SARS-CoV infection is impeded to some extent by exogenously added IFN (17–19), the massively increased IFN sensitivity of an nsp3 macrodomain mutant (20) and the resistance to the IFN-stimulated antiviral kinase protein kinase R (PKR) (21) suggest the presence of active mechanisms to dampen the antiviral effect of IFN. We compared the IFN sensitivity of HCoV-EMC and SARS-CoV in a dose-response experiment. As test systems, we used two established continuous cell line models for SARS-CoV (22, 23), namely, Calu-3 (derived from human bronchial epithelium) and Vero (derived from the kidney of an African green monkey), and primary nondifferentiated HTBE cells for comparison. These cells were pretreated overnight with different amounts of human IFN-β and infected with the coronaviruses at an MOI of 0.01, and virus yields were determined by a TCID50 assay. In agreement with previous studies (8, 9), we noted that SARS-CoV was unable to grow in the nondifferentiated primary HTBE cells (Fig. 2A, top panel). Interestingly, HCoV-EMC could be propagated in these cells, albeit at a reduced rate compared to differentiated HTBE cells (Fig. 2A, bottom panel). The addition of IFN-β clearly had an antiviral effect, reducing HCoV-EMC titers from 10E3/ml to undetectable levels. On Calu-3 cells, both viruses replicated with similar efficiency (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, HCoV-EMC displayed a much more pronounced IFN sensitivity. At 24 h postinfection, 100 units of human IFN-β per ml decreased the titer of HCoV-EMC by 4 orders of magnitude, whereas the titer of SARS-CoV was reduced by only 1.5 orders of magnitude. A similar pattern was observed in Vero cells, in which IFN reduced SARS-CoV titers by a maximum of 1 order of magnitude after 24 h of infection, whereas 100 U/ml IFN-β were sufficient to suppress HCoV-EMC by 5 orders of magnitude (Fig. 2C). These surprising differences in IFN sensitivity prompted us to test smaller amounts of IFN. Indeed, even 5 U/ml IFN-β had a pronounced effect on HCoV-EMC both on Calu-3 cells and on Vero cells, whereas SARS-CoV was much less affected (Fig. 2D and E). Even if the viruses were allowed to replicate for another 24 h, low doses of IFN substantially reduced titers of HCoV-EMC, and higher doses were more effective. Collectively, these results indicate that (i) HCoV-EMC is capable of multiplying in human primary cells and continuous cell lines derived from the target organs (lung and kidney), and (ii) HCoV-EMC is much more sensitive to the antiviral action of type I IFNs than SARS-CoV is.

Fig 2.

Cell tropism and IFN sensitivity. Multiplication and type I IFN sensitivity of HCoV-EMC in comparison to SARS-CoV were studied by applying high or low doses of IFN. (A to C) Cultures of primary nondifferentiated HTBE cells (A), the human bronchial epithelial cell line Calu-3 (B), and the primate kidney cell line Vero (C) were pretreated with 0, 100, 500, or 1,000 units per ml of recombinant human IFN-β (Betaferon; Schering). After 18 h of incubation, cells were infected with SARS-CoV (top panel) or HCoV-EMC (bottom panel) at an MOI of 0.01. Viral titers in the supernatants were determined at 24 h and 48 h p.i., using the TCID50 assay in Vero cells. (D and E) Application of low doses of IFN. IFN sensitivity of the viruses was tested in Calu-3 (D) and Vero (E) cells, using 5, 10, and 50 units per ml of recombinant human IFN-β. Mean values plus standard deviations (error bars) of 3 replicate experiments are shown.

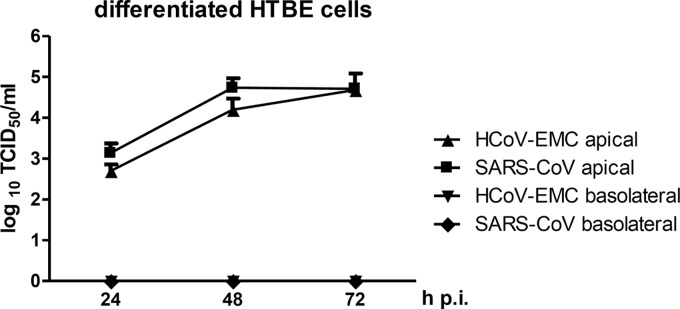

SARS-CoV not only counteracts the IFN-stimulated antiviral state but also downmodulates the initial production of IFN and other innate immune cytokines (24, 25). To compare the antiviral cytokine induction by HCoV-EMC, we performed real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis for two sensitive markers of the IFN response, IFN-β and ISG56 (interferon-stimulated gene 56) (26). In addition, IP-10 (IFN-γ-induced protein 10) (also named CXCL10 [chemokine {C-X-C motif} ligand 10]) was included as a marker of antiviral chemokines. In the first series of experiments, we infected Calu-3 cells with the two coronaviruses at an MOI of 1 (to obtain nearly simultaneous infection of all cells), or as positive control with the strong IFN inducer Rift Valley fever virus mutant RVFVΔNSs::Ren (27). Eighteen hours postinfection, total cell RNA was isolated and tested for innate immunity induction as described previously (20, 26). As expected, SARS-CoV infection did not substantially upregulate IFN-β, ISG56, or IP-10 (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, HCoV-EMC displayed a similar phenotype, as neither innate immune marker was induced above 10-fold. We made similar observations for the 24-h time point of infection (Fig. 3B). It must be mentioned, however, that at this later time point of infection, HCoV-EMC caused a cytopathic effect in Calu-3 cells (data not shown). Of note, production of genomic RNA, the main IFN-inducing element of viruses, is much higher for SARS-CoV and HCoV-EMC than for the IFN-inducing mutant virus used as a control (Fig. 3C). We therefore extended our analyses to A549 cells (a cell line of human alveolar adenocarcinoma), an established system for sensitive measurement of IFN responses (26, 28). Also in these cells, only the positive control, but none of the coronaviruses induced a strong IFN response (Fig. 3D), even at 48 h postinfection (Fig. 3E), and levels of viral RNAs were comparable for all three viruses (Fig. 3F). The A549 system has the disadvantage that SARS-CoV and HCoV-EMC cannot produce infectious particles (data not shown). However, the production of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), a major viral IFN elicitor (29), by HCoV-EMC (see below) implies that an active downregulation of the IFN response is taking place. Infection experiments with nondifferentiated HTBE cells and with the human embryonic kidney cell line 293 confirmed the absence of IFN induction by replicating HCoV-EMC (data not shown).

Fig 3.

Cytokine responses and IRF-3 activation. (A to C) Real-time RT-PCR analyses for cytokine induction (26) and viral RNA production (35–37). The human bronchial epithelium cell line Calu-3 was infected with SARS-CoV, HCoV-EMC, or the recombinant Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) mutant RVFVΔNSs::Ren (control [CTRL]) at an MOI of 1. Total cell RNA was assayed at the indicated time points for changes in the levels of RNAs for IFN-β, ISG56, and IP-10 (A and B) or viral RNAs (C). rel.u., relative units. (D to F) A parallel experiment measuring cytokine induction and viral RNA detection in the human lung adenocarcinoma cell line A549 at the indicated time points p.i. Mean values plus standard deviations (error bars) of 3 replicate experiments are shown. (G) Activation of IRF-3. Calu-3 cells (left panels) or A549 cells (right panels) were infected with the indicated viruses at an MOI of 1, fixed, and stained for endogenous IRF-3 (24), viral dsRNA (29), and RVFV N protein as described previously (38). Note that for reasons of antibody compatibility, the RVFV N signals shown in the small insets are from different coverslips which were infected in parallel. In all IRF-3 images, the contrast was enhanced using the autocontrast feature of Adobe Photoshop.

Interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3) is the key transcription factor for IFN-β, ISG56, IP-10, and other antiviral genes (30). IRF-3 is normally located in the cytoplasm but transported to the nucleus upon infection. We have previously shown that SARS-CoV inhibits IRF-3 by retaining it in the cytoplasm (24). The immunofluorescence analysis shown in Fig. 3G (green channel) demonstrates that, even after a long period of infection with HCoV-EMC, IRF-3 remains located in the cytoplasm. As mentioned above, the demonstration of virally produced dsRNA in the cytoplasm again argues for the presence of an active IFN suppression strategy by HCoV-EMC (Fig. 3G, red channel). Thus, apparently, HCoV-EMC shares with SARS-CoV the ability to dampen human innate immune responses by avoiding the activation of IRF-3 and the upregulation of the IFN response.

In summary, our results demonstrate that the novel coronavirus HCoV-EMC has a human cell type range similar to or even broader than that of SARS-CoV. We found robust virus replication in differentiated and nondifferentiated primary airway epithelial cells, in the lung-derived cell line Calu3, and in the kidney cell lines Vero and 293, whereas the lung cell line A549 is abortively infected. In line with this, it was recently reported that, unlike SARS-CoV, HCoV-EMC can also infect cells of bat or pig origin (31). With respect to the innate immune suppression capacity, we found that HCoV-EMC is similar to SARS-CoV in the ability to inhibit IRF-3 and prevent an antiviral IFN response, but the novel coronavirus is much more sensitive to the antiviral action of IFN. This apparent difference from SARS-CoV raises hopes that the current isolate of HCoV-EMC will not spread at the same speed and scale as SARS-CoV did. Given that there is a range of human genetic disorders which lead to the impairment of the IFN response (32), it would be interesting to know the IFN status of the HCoV-EMC-positive individuals who were afflicted with severe respiratory symptoms (2, 4). In any case, treatment with IFN-β, which is an approved drug against a variety of viral, malignant, and autoimmune diseases (33), appears to be a promising therapeutic option against HCoV-EMC. Future investigations on the IFN-related differences between the related coronaviruses HCoV-EMC and SARS-CoV may allow shed light on the virulence determinants of emerging coronaviruses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to Ron A. Fouchier for providing the HCoV-EMC isolate.

Work in the authors' laboratories is supported by grants 01 KI 0705 and the Deutsches Zentrum für Infektionsforschung (DZIF) from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF), grant 47/2012 MR by the Forschungsförderung gem. §2 Abs. 3 Kooperationsvertrag Universitätsklinikum Giessen und Marburg, the Leibniz Graduate School for Emerging Viral Diseases (EIDIS), and the European Union 7th Framework Programme [FP7/2007-2013] under grant agreement 278433-PREDEMICS.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 28 February 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Bermingham A, Chand M, Brown C, Aarons E, Tong C, Langrish C, Hoschler K, Brown K, Galiano M, Myers R, Pebody R, Green H, Boddington N, Gopal R, Price N, Newsholme W, Drosten C, Fouchier R, Zambon M. 2012. Severe respiratory illness caused by a novel coronavirus, in a patient transferred to the United Kingdom from the Middle East, September 2012. Euro Surveill. 17(40):pii=20290. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20290 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Danielsson N, on behalf of the ECDC Internal Response Team, Catchpole M. 2012. Novel coronavirus associated with severe respiratory disease: case definition and public health measures. Euro Surveill. 17(39):pii=20282. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20282 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3. Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. 2012. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 367:1814–1820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Butler D. 2012. Clusters of coronavirus cases put scientists on alert. Nature 492:166–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Health Protection Agency 15 February 2013, posting date Third case of novel coronavirus infection identified in family cluster. Health Protection Agency, London, United Kingdom: http://www.hpa.org.uk/webw/HPAweb&HPAwebStandard/HPAweb_C/1317138119464 [Google Scholar]

- 6. van Boheemen S, de Graaf M, Lauber C, Bestebroer TM, Raj VS, Zaki AM, Osterhaus AD, Haagmans BL, Gorbalenya AE, Snijder EJ, Fouchier RA. 2012. Genomic characterization of a newly discovered coronavirus associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome in humans. mBio 3(6):e00473–12 doi:10.1128/mBio.00473–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Peiris JS, Yuen KY, Osterhaus AD, Stohr K. 2003. The severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 349:2431–2441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jia HP, Look DC, Shi L, Hickey M, Pewe L, Netland J, Farzan M, Wohlford-Lenane C, Perlman S, McCray PB., Jr 2005. ACE2 receptor expression and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection depend on differentiation of human airway epithelia. J. Virol. 79:14614–14621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sims AC, Baric RS, Yount B, Burkett SE, Collins PL, Pickles RJ. 2005. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection of human ciliated airway epithelia: role of ciliated cells in viral spread in the conducting airways of the lungs. J. Virol. 79:15511–15524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thiel V, Weber F. 2008. Interferon and cytokine responses to SARS-coronavirus infection. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 19:121–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Perlman S, Netland J. 2009. Coronaviruses post-SARS: update on replication and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7:439–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gray TE, Guzman K, Davis CW, Abdullah LH, Nettesheim P. 1996. Mucociliary differentiation of serially passaged normal human tracheobronchial epithelial cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 14:104–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Matrosovich MN, Matrosovich TY, Gray T, Roberts NA, Klenk HD. 2004. Human and avian influenza viruses target different cell types in cultures of human airway epithelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:4620–4624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matrosovich M, Matrosovich T, Uhlendorff J, Garten W, Klenk HD. 2007. Avian-virus-like receptor specificity of the hemagglutinin impedes influenza virus replication in cultures of human airway epithelium. Virology 361:384–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Randall RE, Goodbourn S. 2008. Interferons and viruses: an interplay between induction, signalling, antiviral responses and virus countermeasures. J. Gen. Virol. 89:1–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sadler AJ, Williams BR. 2008. Interferon-inducible antiviral effectors. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8:559–568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cinatl J, Morgenstern B, Bauer G, Chandra P, Rabenau H, Doerr HW. 2003. Treatment of SARS with human interferons. Lancet 362:293–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Haagmans BL, Kuiken T, Martina BE, Fouchier RA, Rimmelzwaan GF, Van Amerongen G, Van Riel D, De Jong T, Itamura S, Chan KH, Tashiro M, Osterhaus AD. 2004. Pegylated interferon-alpha protects type 1 pneumocytes against SARS coronavirus infection in macaques. Nat. Med. 10:290–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Spiegel M, Pichlmair A, Mühlberger E, Haller O, Weber F. 2004. The antiviral effect of interferon-beta against SARS-coronavirus is not mediated by MxA. J. Clin. Virol. 30:211–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kuri T, Eriksson KK, Putics A, Zust R, Snijder EJ, Davidson AD, Siddell SG, Thiel V, Ziebuhr J, Weber F. 2011. The ADP-ribose-1″-monophosphatase domains of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and human coronavirus 229E mediate resistance to antiviral interferon responses. J. Gen. Virol. 92:1899–1905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krahling V, Stein DA, Spiegel M, Weber F, Muhlberger E. 2009. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus triggers apoptosis via protein kinase R but is resistant to its antiviral activity. J. Virol. 83:2298–2309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ng ML, Tan SH, See EE, Ooi EE, Ling AE. 2003. Proliferative growth of SARS coronavirus in Vero E6 cells. J. Gen. Virol. 84:3291–3303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tseng CT, Tseng J, Perrone L, Worthy M, Popov V, Peters CJ. 2005. Apical entry and release of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus in polarized Calu-3 lung epithelial cells. J. Virol. 79:9470–9479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Spiegel M, Pichlmair A, Martinez-Sobrido L, Cros J, Garcia-Sastre A, Haller O, Weber F. 2005. Inhibition of beta interferon induction by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus suggests a two-step model for activation of interferon regulatory factor 3. J. Virol. 79:2079–2086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Spiegel M, Weber F. 2006. Inhibition of cytokine gene expression and induction of chemokine genes in non-lymphatic cells infected with SARS coronavirus. Virol. J. 3:17 doi:10.1186/1743-422X-3-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Overby AK, Popov VL, Niedrig M, Weber F. 2010. Tick-borne encephalitis virus delays interferon induction and hides its double-stranded RNA in intracellular membrane vesicles. J. Virol. 84:8470–8483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Habjan M, Penski N, Spiegel M, Weber F. 2008. T7 RNA polymerase-dependent and -independent systems for cDNA-based rescue of Rift Valley fever virus. J. Gen. Virol. 89:2157–2166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kochs G, Garcia-Sastre A, Martinez-Sobrido L. 2007. Multiple anti-interferon actions of the influenza A virus NS1 protein. J. Virol. 81:7011–7021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Weber F, Wagner V, Rasmussen SB, Hartmann R, Paludan SR. 2006. Double-stranded RNA is produced by positive-strand RNA viruses and DNA viruses but not in detectable amounts by negative-strand RNA viruses. J. Virol. 80:5059–5064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hiscott J. 2007. Triggering the innate antiviral response through IRF-3 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 282:15325–15329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Muller MA, Raj VS, Muth D, Meyer B, Kallies S, Smits SL, Wollny R, Bestebroer TM, Specht S, Suliman T, Zimmermann K, Binger T, Eckerle I, Tschapka M, Zaki AM, Osterhaus ADME, Fouchier RA, Haagmans BL, Drosten C. 2012. Human coronavirus EMC does not require the SARS-coronavirus receptor and maintains broad replicative capability in mammalian cell lines. mBio 3(6):e00515–12 doi:10.1128/mBio.00515–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Boisson-Dupuis S, Kong XF, Okada S, Cypowyj S, Puel A, Abel L, Casanova JL. 2012. Inborn errors of human STAT1: allelic heterogeneity governs the diversity of immunological and infectious phenotypes. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 24:364–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pestka S. 2007. The interferons: 50 years after their discovery, there is much more to learn. J. Biol. Chem. 282:20047–20051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Drosten C, Gunther S, Preiser W, van der Werf S, Brodt HR, Becker S, Rabenau H, Panning M, Kolesnikova L, Fouchier RA, Berger A, Burguiere AM, Cinatl J, Eickmann M, Escriou N, Grywna K, Kramme S, Manuguerra JC, Muller S, Rickerts V, Sturmer M, Vieth S, Klenk HD, Osterhaus AD, Schmitz H, Doerr HW. 2003. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:1967–1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bird BH, Bawiec DA, Ksiazek TG, Shoemaker TR, Nichol ST. 2007. Highly sensitive and broadly reactive quantitative reverse transcription-PCR assay for high-throughput detection of Rift Valley fever virus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:3506–3513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Corman VM, Eckerle I, Bleicker T, Zaki A, Landt O, Eschbach-Bludau M, van Boheemen S, Gopal R, Ballhause M, Bestebroer TM, Muth D, Muller MA, Drexler JF, Zambon M, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RM, Drosten C. 2012. Detection of a novel human coronavirus by real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. Euro Surveill. 17(39):pii=20285. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Weidmann M, Zanotto PM, Weber F, Spiegel M, Brodt HR, Hufert FT. 2004. High-efficiency detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome virus genetic material. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2771–2773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kuri T, Zhang X, Habjan M, Martinez-Sobrido L, Garcia-Sastre A, Yuan Z, Weber F. 2009. Interferon priming enables cells to partially overturn the SARS-coronavirus-induced block in innate immune activation. J. Gen. Virol. 90:2686–2694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]