Abstract

Virophages, e.g., Sputnik, Mavirus, and Organic Lake virophage (OLV), are unusual parasites of giant double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) viruses, yet little is known about their diversity. Here, we describe the global distribution, abundance, and genetic diversity of virophages based on analyzing and mapping comprehensive metagenomic databases. The results reveal a distinct abundance and worldwide distribution of virophages, involving almost all geographical zones and a variety of unique environments. These environments ranged from deep ocean to inland, iced to hydrothermal lakes, and human gut- to animal-associated habitats. Four complete virophage genomic sequences (Yellowstone Lake virophages [YSLVs]) were obtained, as was one nearly complete sequence (Ace Lake Mavirus [ALM]). The genomes obtained were 27,849 bp long with 26 predicted open reading frames (ORFs) (YSLV1), 23,184 bp with 21 ORFs (YSLV2), 27,050 bp with 23 ORFs (YSLV3), 28,306 bp with 34 ORFs (YSLV4), and 17,767 bp with 22 ORFs (ALM). The homologous counterparts of five genes, including putative FtsK-HerA family DNA packaging ATPase and genes encoding DNA helicase/primase, cysteine protease, major capsid protein (MCP), and minor capsid protein (mCP), were present in all virophages studied thus far. They also shared a conserved gene cluster comprising the two core genes of MCP and mCP. Comparative genomic and phylogenetic analyses showed that YSLVs, having a closer relationship to each other than to the other virophages, were more closely related to OLV than to Sputnik but distantly related to Mavirus and ALM. These findings indicate that virophages appear to be widespread and genetically diverse, with at least 3 major lineages.

INTRODUCTION

Virophages, a group of circular double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) viruses, are icosahedral in shape and approximately 50 to 100 nm in size (1–4). Virophages have three unique features (2). First, the nuclear phase is absent during the infection cycle of virophages. Second, the replication of virophages takes place in a viral factory of the giant host DNA viruses. Third, they depend on enzymes from host viruses instead of host cells. Accordingly, virophages are considered to be parasites of giant DNA viruses, e.g., mimiviruses and phycodnaviruses (1–3). Giant DNA viruses possess huge genome sizes (up to ≈1,259 kb), some of which are even larger than those of certain bacteria (5–7). The infection and propagation of virophages lead to a significant decrease in host virus particles and, consequently, an increase in host cell survival (1–3). Additionally, exchanges of genes may occur between virophages and giant DNA viruses (1–3, 8, 9). Therefore, virophages are potential mediators of lateral gene transfer between large DNA viruses (8, 9).

Thus far, four virophages have been identified in distinct locations (Table 1). The first reported virophage, Sputnik, was isolated from an Acanthamoeba species infected with the large mamavirus in a water-cooling tower in Paris, France (2). The second virophage, Mavirus, was observed in a marine phagotrophic flagellate (Cafeteria roenbergensis) in the presence of the host virus, Cafeteria roenbergensis virus, originating from the coastal waters of Texas (1, 10). The third virophage, Organic Lake virophage (OLV), discovered in a hypersaline meromictic lake in Antarctica, is thought to parasitize large DNA viruses infecting microalgae (3, 11). At the time of this report, a fourth virophage, Sputnik 2, together with its host virus, Lentille, has been detected in the contact lens solution of a patient with keratitis in France (12). The fact that virophages exist in a wide range of virus and eukaryotic hosts, as well as in a variety of unique habitats, implies the possibility that they are more widely distributed and diverse than previously thought.

Table 1.

Features of virophages

| Virophage | Location | Host |

Genome |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus | Eukaryote | Size (bp) | No. of ORFs | C+G content (%) | ||

| Sputnik | A cooling tower in Paris, France | Acanthamoeba polyphaga mimivirus | A. polyphaga | 18,343 | 21 | 27.0 |

| Mavirus | Coastal waters of Texas | Cafeteria roenbergensis virus | Marine phagotrophic flagellate (C. roenbergensis) | 19,063 | 20 | 30.3 |

| OLV | Organic Lake, a hypersaline meromictic lake in Antarctica | Large DNA viruses | Prasinophytes (phototrophic algae) | 26,421 | 26 | 39.1 |

| Sputnik 2 | Contact lens fluid of a patient with keratitis, France | Lentille virus | A. polyphaga | 18,338 | 20 | 28.5 |

| YSLV1 | Yellowstone Lake | Phycodna- or mimiviruses? | Microalgae? | 27,849 | 26 | 33.4 |

| YSLV2 | Yellowstone Lake | Phycodna- or mimiviruses? | Microalgae? | 23,184 | 21 | 33.6 |

| YSLV3 | Yellowstone Lake | Phycodna- or mimiviruses? | Microalgae? | 27,050 | 23 | 34.9 |

| YSLV4 | Yellowstone Lake | Phycodna- or mimiviruses? | Microalgae? | 28,306 | 34 | 37.2 |

| ALM | Ace Lake in Antarctica | mimiviruses? | Phagotrophic protozoan? | 17,767 | 22 | 26.7 |

To obtain greater insight into the unusual diversity of the global distribution and abundance of virophages, in this study, metagenomic databases on the Community cyberinfrastructure for Advanced Microbial Ecology Research and Analysis (CAMERA) 2.0 Portal (https://portal.camera.calit2.net/) (13) were analyzed comprehensively. Four complete genomic sequences of virophages and one nearly complete sequence were assembled based on the metagenomic DNA sequences of Yellowstone Lake, Wyoming, and Ace Lake, Antarctica. Comparative genomics and phylogenetic analyses were performed in order to better understand the genomic sequence features, phylogeny, and evolution of virophages.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Analysis of metagenomic databases.

The gene sequences of the three known virophages, Sputnik, Mavirus, and OLV (Sputnik 2 was excluded in the analysis since it was a new strain of Sputnik), were downloaded from the NCBI genome database and blasted against the NCBI nr database. The genomic sequence of another Sputnik, strain 3, was also available in GenBank; however, because Sputnik 2 and Sputnik 3 actually have the same sequence, Sputnik 3 was also not included in the analysis. Genes showing blastp hits to virophages only or no hits (E-value<10−5) were considered virophage-specific marker genes and were used to evaluate the global distribution and abundance of virophages. The genes were searched (tblastx, E-value<10−5) against databases of all metagenomic pyrosequencing reads and all Sanger reads on the CAMERA 2.0 Portal. The screened virophage-related sequences were further confirmed based on a blast similarity search against the NCBI nr databases. Mapping of the global distribution pattern of virophages was visualized through MapInfo Professional (version 11.0; Pitney Bowes Software, Inc.). The abundance of virophages is presented as the ratio of the number of virophage-like sequences in a given metagenomic data set and the total number of sequences in that respective data set, normalized to 1,000,000.

Analysis of virophage conserved genes.

All gene sequences of virophages Sputnik, Mavirus, and OLV were compared to the NCBI nr database using both blastp and PSI-BLAST searches (14, 15). Homologous genes shared among these three virophages were considered to be conserved. Their sequence similarities were also proofed based on multiple sequence alignment using MUSCLE (16) on Geneious Pro (version 5.5.7; Biomatters Ltd.).

Assembling of genomic sequences of new virophages.

Major capsid protein (MCP), the homolog of MV18 (Mavirus), V20 (Sputnik), and OLV09 (OLV), was searched (tblastx, E-value<10−5) against all metagenomic pyrosequencing read databases and all Sanger read databases on the CAMERA 2.0 Portal. Sequences significantly similar to these three MCPs were screened, downloaded, and treated as virophage MCP-related sequences. Subsequently, they were assembled to obtain MCP-related contigs. Each contig served as a reference sequence to which all reads from the corresponding metagenomic database were assembled. Once an extended sequence with a relatively longer size and higher coverage was obtained after assembly, it was used as the next reference to assemble all reads from metagenomic databases. This procedure was repeated until the assembled sequence stopped extending. If there was a repeat region of approximately 100 bp at both ends of the sequence obtained, it was eventually self-assembled to a circular DNA sequence. All sequence assemblies were performed using Geneious Pro. The sequence assembly parameters used in this study were a minimum overlap of 25 bp with >90% sequence identity, as well as 50% maximum mismatches per read.

Prediction and annotation of ORFs.

The prediction and annotation of virophage open reading frames (ORFs) followed the procedures described in the literature (17, 18). Each predicted ORF encompassed a start codon of ATG, minimum size of 135 bp, standard genetic code, and a stop codon. The blastp, tblastx, and PSI-BLAST programs were used for sequence similarity comparisons of the predicted ORFs to NCBI nr databases (14, 15). A local database that contained the translated protein sequences of all predicted ORFs in Sputnik, Mavirus, and OLV, as well as the five new virophages described in this study, was also included in the blast search. ORFs were searched for characteristic sequence signatures using the InterProScan program (19).

Phylogenetic analysis.

Amino acid sequences were aligned using MUSCLE (16), and the phylogenetic trees were reconstructed by using PhyML (version 3.0, Méthodes et Algorithmes pour la Bioinformatique, LIRMM, CNRS—Université de Montpellier; http://www.atgc-montpellier.fr/phyml/) (20).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The genomic sequences of the four Yellowstone Lake virophages (YSLVs) and Ace Lake Mavirus (ALM) have been deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers KC556924 (YSLV1), KC556925 (YSLV2), KC556926 (YSLV3), KC556922 (YSLV4), and KC556923 (ALM).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Diversity of global distribution and abundance of virophages.

The blast similarity search (E-value<10−5) indicated that a total of 44 ORFs turned out to be virophage-specific marker genes, comprising 16 ORFs of Sputnik, 13 of Mavirus, and 15 of OLV (Table 2). These genes were used as query sequences and searched against all metagenomic data deposited in the CAMERA database. The CAMERA database is a web-based analysis portal that allows for depositing, locating, analyzing, visualizing, and sharing microbial data obtained from various environments, such as marine, soil, freshwater, wastewater, hot springs, animal hosts, and other habitats (13). Therefore, the general tendency of the global distribution and abundance of virophages can be predicted according to the virophage-related sequence information of blast hits provided by the CAMERA 2.0 Portal. The search found 1,766 pyrosequencing reads and 204 Sanger reads related to Sputnik, 203 pyrosequencing reads and 253 Sanger reads akin to Mavirus, and more than 50,000 pyrosequencing reads and Sanger reads similar to OLV (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The redundant reads were incorporated and removed. Finally, 23,599 virophage-related sequences were obtained. Among them, 148 were Mavirus hits, 812 were Sputnik hits, and 22,639 were OLV hits, accounting for 95% of the total sequences associated with virophages (23,599). It appeared that OLV and its relatives were more abundant than Sputnik and Mavirus virophages in the environments.

Table 2.

Virophage-specific genes

| Virophage | Genes |

|---|---|

| Sputnik | V01, V02, V03, V04, V05, V07, V08, V09, V14, V15, V16, V17, V18, V19, V20, V21 |

| Mavirus | MV04, MV05, MV07, MV08, MV09, MV10, MV11, MV12, MV14, MV15, MV16, MV17, MV18 |

| OLV | OLV01, OLV02, OLV03, OLV04, OLV05, OLV06, OLV07, OLV08, OLV09, OLV10, OLV11, OLV15, OLV21, OLV24, OLV26 |

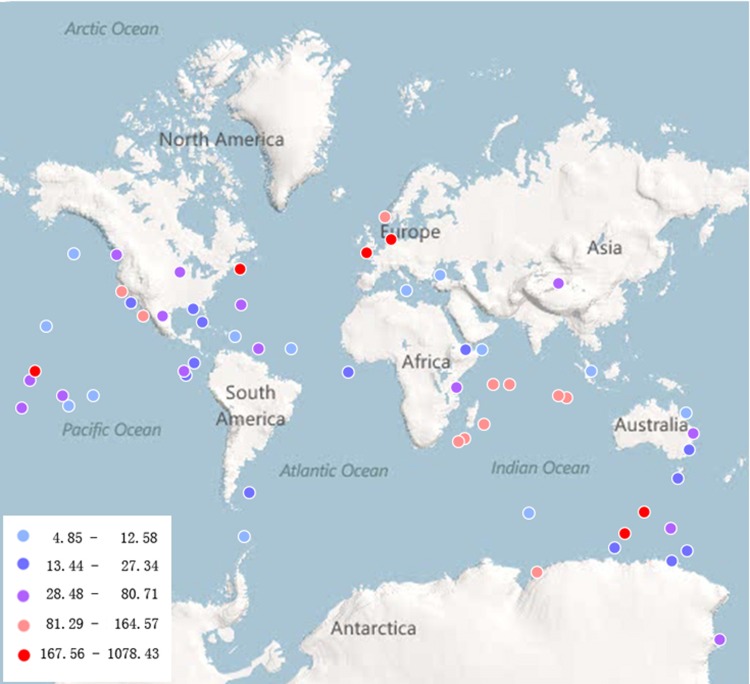

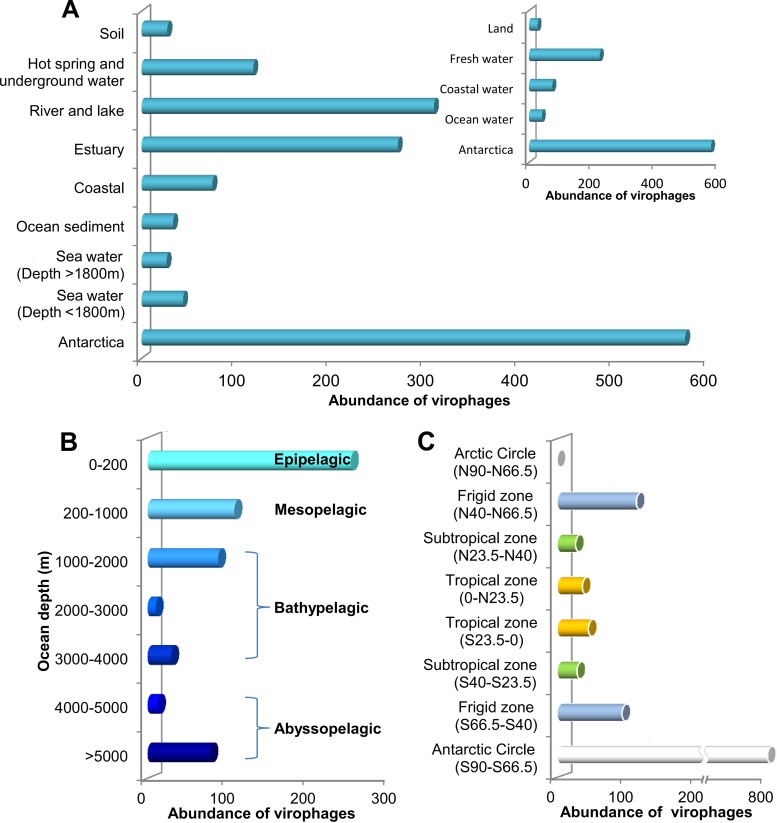

As depicted in Figure 1, virophages were distributed widely throughout the world, including almost all geographical zones. The habitats of virophages were also localized in a variety of environments, ranging from the deep ocean to inland (Fig. 2). The abundance of virophages tended to increase from the ocean to land environments, was the highest in freshwater habitats, and was relatively greater in ocean sediment than in deep seawater (Fig. 2A). As for vertical distribution, in general, virophage abundance decreased with the increase in ocean depth (Fig. 2B). The epipelagic zone seemed to be enriched with virophages. This was probably because this illuminated zone at the surface of the sea is colonized by the most living organisms in the sea. Interestingly, although there is a large difference between the conditions of the abyssopelagic and the mesopelagic zones, it seemed that the numbers of virophage-related sequences observed in these two zones were quite similar (Fig. 2B). Whether real virophage enrichment was present in the abyssopelagic zone or whether it was a result of the virophage-infected host viruses and/or host cells settling to the deep sea remains to be studied further. In terms of geographical zones, the frigid zones turned out to have the greatest abundance of virophages, followed by the tropical zones (Fig. 2C). Obvious limitations and biases of the data deposited in CAMERA exist, and caution should be taken during attempts to interpret the global distribution and abundance of virophages. However, these findings open a new window into further exploration and survey of the diversity of unique virophages worldwide.

Fig 1.

Geographic distribution and corresponding abundance of virophages. Colored dots indicate distinct abundances of virophages in metagenomic data sets obtained from a specific area of latitude and longitude (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Abundance was normalized to 1,000,000.

Fig 2.

Abundance of virophages in different environments (A), ocean depths (B), and latitudes (C). Abundance was normalized to 1,000,000.

In addition, unexpectedly, a small number of virophage-related sequences was detected in nonaquatic environments, e.g., 65 sequences from the human gut, 11 from animal-associated habitats, 7 from soils, 4 from glacier metagenomes, and 1 from air in the East Coast of Singapore. Thus far, little is known with regard to such unusual diversity (21). Taken together, comparative analyses of metagenomic databases revealed the global distribution and distinct abundance of virophage-related sequences, which suggested that virophages are common entities on Earth. Large-scale sampling and analyses are necessary to obtain a complete picture of the diversity of virophages.

Four complete genomes of Yellowstone Lake virophages and one nearly complete genome of Ace Lake Mavirus.

Major capsid protein is generally considered to be a conserved protein among viruses, and it is widely used to reconstruct phylogenetic trees. It was also conserved in virophages, based on blast sequence similarity searches and sequence alignment. In our study, four complete virophage genomes and one nearly complete virophage genome were obtained from two metagenomic databases named Yellowstone Lake: Genetic and Gene Diversity in a Freshwater Lake and Antarctica Aquatic Microbial Metagenome, which were downloaded from the CAMERA 2.0 Portal. These virophages were tentatively named YSLV1, YSLV2, YSLV3, YSLV4, and ALM. Detailed results of the metagenome assembly, i.e., genome coverage, the number of reads recruited to each genome, and the size of the data sets from which the metagenomes originated, are shown in Table 3; see also Figures S1 and S2 in the supplemental material.

Table 3.

Data on metagenomic assemblies of the five new virophages

| Name | No. of reads recruited to each genome | No. of identical sites | Pairwise identity (%) | Genome coverage |

Size of dataset (Gb) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Minimum | Maximum | |||||

| YSLV1 | 5,544 | 22,271 | 98.0 | 67.9 | 16 | 127 | 11.1 |

| YSLV2 | 834 | 21,453 | 97.7 | 13.1 | 3 | 27 | 11.1 |

| YSLV3 | 1,098 | 25,529 | 98.2 | 15.1 | 3 | 35 | 11.1 |

| YSLV4 | 1,119 | 25,732 | 97.2 | 14.5 | 4 | 32 | 11.1 |

| ALM | 494 | 13,654 | 95.4 | 14.4 | 4 | 26 | 32.4 |

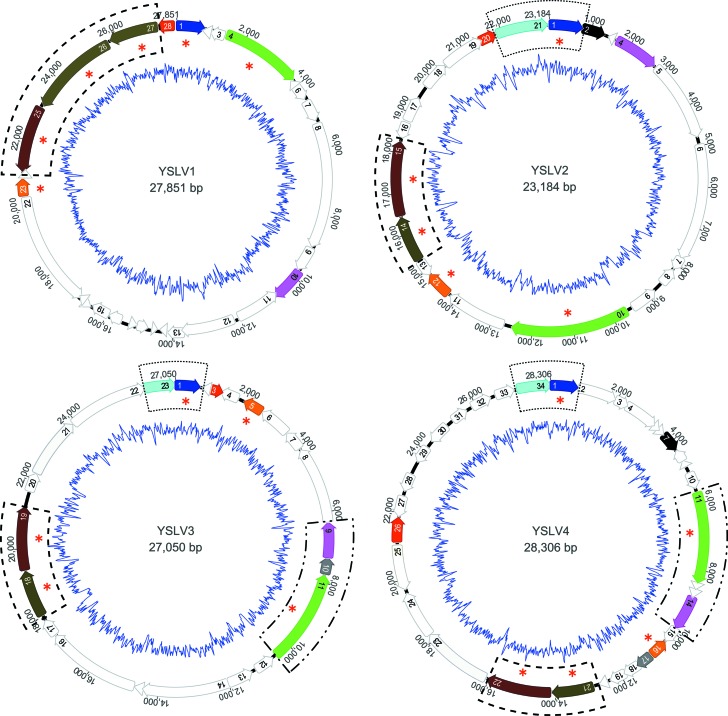

They were all dsDNA viruses, with G+C contents of 33.4% (YSLV1), 33.6% (YSLV2), 34.9% (YSLV3), 37.2% (YSLV4), and 26.7% (ALM) (Table 1). Their genomes were 27,849 bp in length with 26 predicted ORFs (YSLV1), 23,184 bp with 21 predicted ORFs (YSLV2), 27,050 bp with 23 predicted ORFs (YSLV3), 28,306 bp with 34 predicted ORFs (YSLV4), and 17,767 bp with 22 predicted ORFs (ALM) (Table 1 and Fig. 3 and 4). The YSLVs and OLV were generally alike in genome size, number of ORFs, and G+C content (Table 1).

Fig 3.

Circular maps of the complete genomes of Yellowstone Lake virophages. Homologous genes are indicated in the same color, the five conserved genes are labeled with red asterisks, and the inner circles represent G+C content plots. The dashed-line boxes represent the conserved gene cluster in all eight virophages, the dotted-line boxes represent the gene cluster shared by YSLVs 2, 3, and 4 and OLV, and the dash-dot-dot–line boxes represent the gene cluster present in YSLVs 3 and 4.

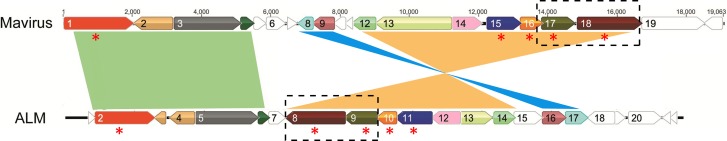

Fig 4.

Linear genomic map of ALM and Mavirus. Homologous genes are shown in the same color, while syntenic regions are presented in green, light blue, and orange. The five virophage conserved genes are labeled with red asterisks, and the conserved gene cluster is marked with dashed-line boxes.

Among 126 predicted ORFs from these five new virophages, 59 showed significant similarity to 33 of 67 ORFs of three known virophages, 11 showed similarity to the nucleocytoplasmic large DNA viruses (NCLDs) of eukaryotes (including phycodnaviruses, Marseilleviruses, and mimiviruses), and 3 showed similarity to sequences of unicellular eukaryotic organisms (marine choanoflagellate Monosiga brevicollis and ciliated protozoan Tetrahymena thermophila); 67 ORFs had no sequence hits to current NCBI databases (Table 4). Given that the virus and eukaryotic hosts of the virophages obtained in this study may be the NCLDs and the protists mentioned above (or their associated relatives), it is conceivable that horizontal gene transfer and/or gene recombination occurred between ancestor virophages and their viruses, as well as cellular hosts. Such gene replacement traces have been observed in virophages (Sputnik, Mavirus, and OLV) and their hosts (1–3). In addition, significant sequence similarity (E-value<10−5) was not detected between virophages and any viruses infecting multicellular organisms, which suggested that virophages diverged early and subsequently underwent a strict and unique evolution with their viruses and unicellular eukaryotic hosts.

Table 4.

ORFs and their homologs predicted in YSLVs and ALM

| Virophage, ORF | Position |

Lengtha |

Best blastp hit in GenBank nr database and/or virus data set |

NCBI conserved domain (identifier, E-value, alignment length in aa, alignment position [start–end]) | Interproscan matches (identifier, E-value[s], alignment position[s] [start–end]) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | End | nt | aa | ORF, protein encoded, or mass | Species | Accession no. | E-value | % aa identity | Alignment length in aa (position start–end) | |||

| YSLV1 | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 771 | 771 | 256 | Hypothetical protein OLV4 | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05765 | 2.01E−79 | 51 | 246 (1–246) | AAA domain (pfam13401, 4.46E−04, 124, 57–158) | P loop-containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases (SSF52540, 2.0E−6, 49–226) |

| 2 | 968 | 768 | 201 | 66 | ||||||||

| 3 | 1387 | 1049 | 339 | 112 | ||||||||

| 4 | 1475 | 3775 | 2,301 | 766 | Putative DNA primase/polymerase | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05784 | 7.79E−26 | 23.9 | 626 (50–675) | P loop-containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases (SSF52540, 6.5E−13, 486–663) | |

| 5 | 3959 | 3825 | 135 | 44 | SP (1–17), TM (4–22) | |||||||

| 6 | 4037 | 4429 | 393 | 130 | ||||||||

| 7 | 4563 | 5129 | 567 | 188 | VP11 | Micromonas pusilla reovirus | YP_654554 | 5.95E−15 | 24 | 146 (4–149) | TM (39–59 69-91) | |

| 8 | 5275 | 8955 | 3,681 | 1,226 | ATHOOK (PR00929, 6.8E−6, 6.8E−6, 6.8E−6, 345–355, 380–391, 417–427) | |||||||

| 9 | 9051 | 9728 | 678 | 225 | Hypothetical protein MV06 | Mavirus | YP_004300284 | 0.004 | 34 | 84 (48–131) | N-terminal catalytic domain of GIY-YIG intron endonuclease I-TevI, I-BmoI, I-BanI, I-BthII, and similar proteins (cd10437, 3.38E−03, 90, 48–129) | Alpha/beta-hydrolases (SSF53474, 1.1E−8, 159–273) |

| 10 | 9816 | 10742 | 927 | 308 | Hypothetical protein OLV11 | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05772 | 2.83E−56 | 37.3 | 299 (7–305) | ||

| 11 | 11999 | 10743 | 1,257 | 418 | ||||||||

| 12 | 12201 | 13709 | 1,509 | 502 | ||||||||

| 13 | 13740 | 14087 | 348 | 115 | ||||||||

| 14 | 14199 | 14354 | 156 | 51 | ||||||||

| 15 | 14586 | 14335 | 252 | 83 | ||||||||

| 16 | 15090 | 14758 | 333 | 110 | ||||||||

| 17 | 15260 | 15084 | 177 | 58 | ||||||||

| 18 | 15567 | 15905 | 339 | 112 | ||||||||

| 19 | 15974 | 16462 | 489 | 162 | ||||||||

| 20 | 16755 | 16588 | 168 | 55 | SP (1–25) | |||||||

| 21 | 16765 | 16935 | 171 | 56 | ||||||||

| 22 | 20302 | 16940 | 3,363 | 1120 | Unnamed protein product | Paenibacillus sp. JDR-2 | YP_003010191 | 4.00E−56 | 25 | 834 (114–947) | ||

| Hypothetical protein | Cyanophage NATL2A-133 | 8.00E−34 | 31 | 355 (380–734) | ||||||||

| 23 | 20395 | 20967 | 573 | 190 | Hypothetical protein OLV7 | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05768 | 8.35E−21 | 31.6 | 168 (22–189) | ||

| 24 | 20939 | 21115 | 177 | 58 | SP (1–31), TM (5–25) | |||||||

| 25 | 22991 | 21120 | 1,872 | 623 | Major capsid protein | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05770 | 1.00E−32 | 27 | 579 (1–579) | ||

| 26 | 25733 | 23133 | 2,601 | 866 | Putative minor capsid protein | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05769 | 4.00E−15 | 29 | 205 (643–847) | Putative isomerase YbhE (SSF101908, 1.6E−10, 119–433) | |

| 27 | 27321 | 25888 | 1,434 | 477 | Putative minor capsid protein | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05769 | 2.00E−15 | 34 | 125 (332–456) | ||

| 28 | 27741 | 27427 | 315 | 104 | Tlr 6Fp protein | Tetrahymena thermophila | AF451864_6 | 5.28E−10 | 32.5 | 80 (25–104) | ||

| Hypothetical protein MAR_433 | Marseillevirus | YP_003407157 | 7.00E−13 | 35 | 78 (9–86) | |||||||

| YSLV2 | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 765 | 765 | 254 | Hypothetical protein OLV4 | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05765 | 1.30E−48 | 40.8 | 242 (3–244) | ||

| 2 | 807 | 1322 | 516 | 171 | Hypothetical protein PRSM4_062 | Prochlorococcus phage P-RSM4 | YP_004323191 | 1.85E−08 | 40 | 70 (12–81) | ||

| 3 | 1570 | 1319 | 252 | 83 | ||||||||

| 4 | 1691 | 2725 | 1,035 | 344 | Hypothetical protein OLV11 | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05772 | 2.32E−40 | 33.9 | 297 (19–315) | ||

| 5 | 2839 | 4758 | 1,920 | 639 | Putative ATP-dependent RNA helicase | Acanthamoeba polyphaga mimivirus | YP_003987051 | 2.63E−32 | 29.8 | 444 (179–622) | DEAD-like helicases superfamily (smart00487, 4.48E−10, 177, 174–350) | Helicase_C (PF00271, 2.4E−6, 551–606) |

| SNF2 family N-terminal domain (pfam00176, 1.19E−09, 238, 182–419) | DEAD-like helicases superfamily (SM00487, 0.0013, 175–378) | |||||||||||

| Helicase superfamily C-terminal domain (cd00079, 1.52E−04, 145, 461–605) | P loop-containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases (SSF52540, 8.7E−23, 2.3E−20, 137–378, 385–636) | |||||||||||

| 6 | 4992 | 7772 | 2,781 | 926 | C terminus: hypothetical protein 162275902 | Organic Lake phycodnavirus 2 | ADX06405 | 6.07E−07 | 50 | 66 (834–899) | Methyltransferase domain (pfam13659, 2.52E−07, 111, 151–261) | S-Adenosyl-l-methionine-dependent methyltransferases (SSF53335, 3.3E−10, 156–307) |

| 7 | 7862 | 8086 | 225 | 74 | TM (34–52) | |||||||

| 8 | 8538 | 8164 | 375 | 124 | ||||||||

| 9 | 9182 | 8628 | 555 | 184 | ||||||||

| 10 | 9656 | 12484 | 2,829 | 942 | Helicase | Acanthamoeba castellanii mamavirus | AEQ60154 | 4.43E−44 | 30.5 | 465 (295–759) | Origin of replication binding protein (pfam02399, 7.47E−08, 148, 353–500) | P loop-containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases (SSF52540, 2.5E−8, 276–521) |

| 11 | 12724 | 14148 | 1,425 | 474 | DEAD-like helicases superfamily (smart00487, 2.98E−06, 179, 341–519) | |||||||

| 12 | 14260 | 14847 | 588 | 195 | Hypothetical protein OLV7 | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05768 | 1.07E−15 | 29.7 | 161 (32–192) | SP (1–30), TM (15–35, 41–56, 77–97) | |

| 13 | 15207 | 14911 | 297 | 98 | ||||||||

| 14 | 15192 | 16394 | 1,203 | 400 | Putative minor capsid protein | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05769 | 3.00E−19 | 24.9 | 393 (1–393) | ||

| 15 | 16489 | 18243 | 1,755 | 584 | Putative capsid protein V20 | Sputnik virophage | YP_002122381 | 2.15E−37 | 26.1 | 554 (10–563) | ||

| 16 | 18726 | 18424 | 303 | 100 | SP (1–19), TM (4–22) | |||||||

| 17 | 18826 | 19386 | 561 | 186 | ||||||||

| 18 | 19764 | 20378 | 615 | 204 | Hypothetical protein MV08 | Mavirus | YP_004300286 | 0.46 | 32 | 96 (88–183) | ||

| 19 | 20460 | 21449 | 990 | 329 | ||||||||

| 20 | 21536 | 21841 | 306 | 101 | Hypothetical protein | Paramecium bursaria chlorella virus 1 | NP_048469 | 3.43E−11 | 33.8 | 80 (7–86) | ||

| 21 | 21902 | 23116 | 1215 | 404 | N terminus: hypothetical protein OLV5 | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05766 | 1.24E−08 | 24.6 | 197 (25–221) | ||

| YSLV3 | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 765 | 765 | 254 | Hypothetical protein OLV4 | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05765 | 7.58E−54 | 40 | 248 (4–251) | ||

| 2 | 950 | 762 | 189 | 62 | ||||||||

| 3 | 976 | 1308 | 333 | 110 | ||||||||

| 4 | 1772 | 1311 | 462 | 153 | SP (1–18) | |||||||

| 5 | 2528 | 2010 | 519 | 172 | Hypothetical protein OLV7 | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05768 | 4.81E−14 | 30.5 | 164 (5–168) | ||

| 6 | 3442 | 2606 | 837 | 278 | Hypothetical protein OLV12 | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05773 | 6.04E−27 | 55.7 | 113 (135–247) | ||

| 7 | 4020 | 3523 | 498 | 165 | Hypothetical protein HMPREF9628_01282 | Eubacteriaceae bacterium CM5 | ZP_09316646 | 2.85E−13 | 32.2 | 158 (7–164) | Site-specific DNA methylase (COG0338, 1.22E−16, 160, 5–164) | |

| Putative modification methylase DpnIIA | Clostridium phage phiSM101 | YP_699979 | 3.00E−11 | 32 | 160 (5–164) | DNA adenine methylase (TIGR00571, 6.15E−11, 154, 5–158) | S-Adenosyl-l-methionine-dependent methyltransferases (SSF53335, 5.6E−21, 5–165) | |||||

| 8 | 6254 | 3954 | 2,301 | 766 | D12 class N6 adenine-specific DNA methyltransferase (pfam02086, 2.44E−07, 152, 13–164) | |||||||

| 9 | 7249 | 6317 | 933 | 310 | Hypothetical protein OLV11 | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05772 | 1.35E−48 | 39.4 | 285 (16–300) | ||

| 10 | 7715 | 7311 | 405 | 134 | ||||||||

| 11 | 10417 | 7820 | 2,598 | 865 | D5-ATPase-helicase, partial | Moumouvirus ochan | AEY99298 | 1.27E−33 | 29.8 | 426 (287–712) | Phage/plasmid primase, P4 family, C-terminal domain (TIGR01613, 1.40E−22, 293, 495–787) | D5_N (PF08706, 1.4E−11, 390–542) |

| D5 N terminus-like (pfam08706, 2.13E−06, 89, 434–522) | PriCT_2 (PF08707, 1.2E−4, 279–345) | |||||||||||

| 12 | 11103 | 10600 | 504 | 167 | Hypothetical protein | Mavirus | YP_004300284 | 5.79E−02 | 47.2 | 51 (24–74) | Phage-associated DNA primase (COG3378, 1.08E−22, 379, 394–772) | |

| 13 | 11975 | 11307 | 669 | 222 | ||||||||

| 14 | 12033 | 14423 | 2,391 | 796 | ||||||||

| 15 | 14450 | 14650 | 201 | 66 | SP (1–25), TM (5–25) | |||||||

| 16 | 14726 | 17311 | 2,586 | 861 | ||||||||

| 17 | 17402 | 17722 | 321 | 106 | ||||||||

| 18 | 18065 | 19318 | 1,254 | 417 | Putative minor capsid protein | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05769 | 4.26E−12 | 25.2 | 386 (26–411) | ||

| 19 | 19412 | 21148 | 1,737 | 578 | Putative capsid protein V20 | Sputnik virophage | YP_002122381 | 4.79E−39 | 26.8 | 544 (9–552) | ||

| 20 | 21761 | 22132 | 372 | 123 | ||||||||

| 21 | 22204 | 23868 | 1,665 | 554 | C terminus: hypothetical protein OLV10 | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05771 | 0.13 | 27 | 133 (421–553) | ||

| 22 | 23942 | 26155 | 2,214 | 737 | ||||||||

| 23 | 26196 | 27023 | 828 | 275 | Hypothetical protein OLV5 | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05766 | 1.98E−13 | 27.6 | 190 (26–215) | ||

| YSLV4 | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 768 | 768 | 255 | Hypothetical protein OLV4 | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05765 | 3.10E−67 | 44 | 248 (1–248) | ||

| 2 | 831 | 1922 | 1092 | 363 | ||||||||

| 3 | 1982 | 2317 | 336 | 111 | ||||||||

| 4 | 2341 | 3300 | 960 | 319 | Ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase small subunit | Phaeocystis globosa virus 12T | AET72957 | 3.39E−136 | 60.5 | 317 (3–319) | Ribonucleotide reductase, R2/beta subunit, ferritin-like diiron-binding domain (cd01049, 9.46E−102, 274, 13–286) | Ribonuc_red_sm (PF00268, 1.0E−98, 7–283) |

| Ferritin-like (SSF47240, 3.1E−105, 1–303) | ||||||||||||

| 5 | 3337 | 3489 | 153 | 50 | SP (1–43), TM (25–45) | |||||||

| 6 | 3496 | 3687 | 192 | 63 | SP (1–21), TM (5–25) | |||||||

| 7 | 3730 | 4248 | 519 | 172 | Hypothetical protein PRSM4_062 | Prochlorococcus phage P-RSM4 | YP_004323191 | 7.07E−09 | 43.4 | 76 (12–87) | N6_MTASE (PS00092, −1.0, 76–82) | |

| 8 | 4638 | 4339 | 300 | 99 | ||||||||

| 9 | 4820 | 4680 | 141 | 46 | ||||||||

| 10 | 5196 | 5525 | 330 | 109 | ||||||||

| 11 | 5700 | 8342 | 2,643 | 880 | C terminus: D5-like helicase-primase | Marseillevirus | YP_003407183 | 9.04E−20 | 28.2 | 218 (474–691) | VirE (PF05272, 4.4E−5, 554–695) | |

| PriCT_2 (PF08707, 1.1E−4, 300–375) | ||||||||||||

| 12 | 8402 | 8551 | 150 | 49 | TM (14–32) | |||||||

| 13 | 8602 | 8802 | 201 | 66 | ||||||||

| 14 | 8836 | 9816 | 981 | 326 | Hypothetical protein OLV11 | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05772 | 7.68E−59 | 42.1 | 296 (11–306) | ||

| 15 | 9862 | 10302 | 441 | 146 | ||||||||

| 16 | 10874 | 10299 | 576 | 191 | Hypothetical protein OLV7 | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05768 | 8.06E−27 | 37.2 | 147 (37–183) | ||

| 17 | 10991 | 11410 | 420 | 139 | ||||||||

| 18 | 11412 | 11855 | 444 | 147 | ||||||||

| 19 | 11880 | 12311 | 432 | 143 | ||||||||

| 20 | 12462 | 12662 | 201 | 66 | ||||||||

| 21 | 12890 | 14074 | 1,185 | 394 | Putative minor capsid protein | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05769 | 3.20E−40 | 31.2 | 359 (27–385) | ||

| 22 | 14173 | 16026 | 1,854 | 617 | Major capsid protein | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05770 | 6.10E−48 | 28 | 569 (2–570) | ||

| 23 | 16143 | 18170 | 2,028 | 675 | ||||||||

| 24 | 18232 | 19557 | 1,326 | 441 | ||||||||

| 25 | 21005 | 19740 | 1,266 | 421 | C terminus: hypothetical protein OLV12 | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05773 | 8.69E−38 | 42.2 | 201 (209–409) | Alpha/beta-hydrolases (SSF53474, 1.3E−9, 238–360) | |

| N terminus: hypothetical protein OLV12 | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05773 | 2.19E−19 | 36 | 194 (14–207) | |||||||

| 26 | 21151 | 21834 | 684 | 227 | C terminus: hypothetical protein OLV2 | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05763 | 9.46E−10 | 41.1 | 91 (137–227) | ||

| 27 | 22466 | 21915 | 552 | 183 | ||||||||

| 28 | 23048 | 22686 | 363 | 120 | ||||||||

| 29 | 24066 | 23677 | 390 | 129 | ||||||||

| 30 | 24923 | 24360 | 564 | 187 | ||||||||

| 31 | 25230 | 25613 | 384 | 127 | ||||||||

| 32 | 25909 | 26466 | 558 | 185 | N-Acetyltransferase GCN5 | Clostridium phytofermentans ISDg | YP_001560895 | 1.03E−04 | 27.7 | 82 (67–148) | Acetyltransferase family (pfam00583, 1.11E−09, 85, 62–146) | Acetyltransf_1 (PF00583, 2.5E−10, 67–146) |

| 33 | 26677 | 27198 | 522 | 173 | Acyl-coenzyme A N-acyltransferases (Nat) (SSF55729, 1.2E−12, 48–168) | |||||||

| 34 | 27327 | 28304 | 978 | 325 | Hypothetical protein OLV5 | Organic Lake virophage | ADX05766 | 3.04E−25 | 28.4 | 305 (14–318) | ||

| ALM | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 706 | 840 | 135 | 44 | ||||||||

| 2 | 890 | 2551 | 1,662 | 553 | Hypothetical protein | Monosiga brevicollis MX1 | XP_001743771 | 5.06E−37 | 28.9 | 363 (8–370) | Phage/plasmid primase, P4 family, C-terminal domain (TIGR01613, 1.80E−05, 246, 163–408) | Winged helix DNA-binding domain (SSF46785, 7.9E−6, 366–441) |

| Highly derived D5-like helicase-primase | Marseillevirus | YP_003406787 | 5.51E−16 | 26.4 | 283 (144–426) | P loop-containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases (SSF52540, 2.2E−6, 126–294) | ||||||

| 3 | 2868 | 2593 | 276 | 91 | Putative RVE superfamily integrase | Mavirus | YP_004300280 | 3.63E−08 | 39.4 | 91 (1–91) | Chromo (chromatin organization modifier) domain (pfam00385, 8.54E−03, 21, 56–76) | Chromatin organization modifier domain (SM00298, 8.0E−10, 35–90) |

| 4 | 3689 | 3033 | 657 | 218 | Putative RVE superfamily integrase | Mavirus | YP_004300280 | 2.21E−36 | 41.1 | 192 (1–192) | Integrase core domain (pfam00665, 4.94E−07, 114, 46–159) | Rve (PF00665, 8.4E−16, 48–157) RNase H-like |

| (SSF53098, 1.6E−18, 38–209) | ||||||||||||

| 5 | 3773 | 5533 | 1,761 | 586 | Putative protein-primed B-family DNA polymerase | Mavirus | YP_004300281 | 8.21E−88 | 35 | 536 (47–582) | DNA polymerase type B, organellar and viral (pfam03175, 1.34E−03, 224, 291–514) | DNA/RNA polymerases (SSF56672, 1.2E−19, 290–569) |

| 6 | 5578 | 5850 | 273 | 90 | Hypothetical protein MV04 | Mavirus | YP_004300282 | 5.9 | 31 | 45 (2–46) | ||

| 7 | 5884 | 6315 | 432 | 143 | ||||||||

| 8 | 8027 | 6366 | 1,662 | 553 | Putative major capsid protein MV18 | Mavirus | YP_004300296 | 1.18E−76 | 31.3 | 522 (3–524) | ||

| 9 | 8947 | 8057 | 891 | 296 | Hypothetical protein MV17 | Mavirus | YP_004300295 | 1.85E−65 | 42.1 | 291 (1–291) | ||

| 10 | 9511 | 8984 | 528 | 175 | Putative cysteine protease MV16 | Mavirus | YP_004300294 | 1.25E−54 | 52.2 | 175 (1–175) | ||

| 11 | 10541 | 9537 | 1,005 | 334 | Putative FtsK-HerA family ATPase MV15 | Mavirus | YP_004300293 | 7.25E−80 | 50 | 266 (69–334) | AAA_17 (PF13207, 1.1E−6, 95–228) | |

| 12 | 11354 | 10566 | 789 | 262 | Hypothetical protein MV14 | Mavirus | YP_004300292 | 5.20E−55 | 43.6 | 259 (1–259) | ||

| 13 | 11406 | 12266 | 861 | 286 | N terminus: hypothetical protein MV13 | Mavirus | YP_004300291 | 9.03E−06 | 29.5 | 129 (1–129) | ||

| 14 | 12160 | 12930 | 771 | 256 | Hypothetical protein MV12 | Mavirus | YP_004300290 | 1.88E−69 | 52.6 | 196 (57–252) | TM (34–52) | |

| 15 | 12956 | 13714 | 759 | 252 | ||||||||

| 16 | 13774 | 14406 | 633 | 210 | Hypothetical protein MV09 | Mavirus | YP_004300287 | 0.21 | 29 | 97 (103–199) | ||

| 17 | 14430 | 15020 | 591 | 196 | Hypothetical protein MV08 | Mavirus | YP_004300286 | 1.02E−12 | 48.3 | 84 (112–195) | ||

| 18 | 15794 | 15060 | 735 | 244 | Hypothetical protein MV13 | Mavirus | YP_004300291 | 7.52E−13 | 29.1 | 198 (29–226) | Lipase (class3) (cd00519, 3.78E−08, 123, 96–218) | Lipase_3 (PF01764, 2.1E−4, 132–162) |

| 19 | 15806 | 16093 | 288 | 95 | Alpha/beta-hydrolases (SSF53474, 5.1E−10, 95–178) | |||||||

| 20 | 16261 | 17145 | 885 | 294 | ||||||||

| 21 | 17400 | 17224 | 177 | 58 | ||||||||

| 22 | 17579 | 17445 | 135 | 44 | ||||||||

aa, amino acids.

Conserved genes of virophages.

Based on a blastp and PSI-BLAST search against NCBI nr databases and a local database comprising all ORFs of eight virophages (five in this study and three published), five genes were found to be present in all eight virophages (Table 5). They were putative FtsK-HerA family DNA packaging ATPase and genes encoding putative DNA helicase/primase (HEL/PRIM), putative cysteine protease (PRSC), putative MCP, and putative minor capsid protein (mCP). These four genes had blastp hits to virophage genes only (E-value<10−1), with the exception of HEL/PRIM (Table 4). Sequence alignment of these four proteins also revealed unambiguous similarity of amino acids (data not shown). Hence, it is reasonable to define them as virophage conserved core genes. The HEL/PRIM homolog was predicted according to either functional domains or sequence similarity, since significant sequence similarity was undetectable among some virophage species (Table 4).

Table 5.

Gene homologues present in virophages

| Gene product | ORF(s) (size in aaa) in indicated virophage |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YSLV1 | YSLV2 | YSLV3 | YSLV4 | OLV | Sputnik | ALM | Mavirus | |

| Putative FtsK-HerA family ATPase | 01 (256) | 01 (254) | 01 (254) | 01 (255) | 04 (256) | 03 (245) | 11 (334) | 15 (310) |

| Putative DNA helicase/primase/polymerase | 04 (766) | 10 (942) | 11 (865) | 11 (880) | 25 (777) | 13 (779) | 02 (553) | 01 (652) |

| Putative GIY-YIG endonuclease | 09 (225) | 12 (167) | 24 (129) | 14 (114) | 06 (165) | |||

| Hypothetical protein | 10 (308) | 04 (344) | 09 (310) | 14 (326) | 11 (298) | |||

| Putative cysteine protease | 23 (190) | 12 (195) | 05 (172) | 16 (191) | 07 (190) | 09 (175) | 10 (175) | 16 (189) |

| Putative major capsid protein | 25 (623) | 15 (584) | 19 (578) | 22 (617) | 09 (576) | 20 (595) | 08 (553) | 18 (606) |

| Putative minor capsid protein | 27 (477), 26 (866) | 14 (400) | 18 (417) | 21 (394) | 08 (389) | 18 (167), 19 (218) | 09 (296) | 17 (303) |

| Hypothetical protein | 28 (104) | 20 (101) | 03 (110) | 26 (227) | 02 (123) | |||

| Hypothetical protein | 02 (171) | 07 (172) | ||||||

| Hypothetical protein | 09 (184) | 07 (143) | ||||||

| Hypothetical protein | 18 (204) | 17 (196) | 08 (122) | |||||

| Hypothetical protein | 21 (404) | 23 (275) | 34 (325) | 05 (290) | 21 (438) | |||

| Hypothetical protein | 06 (278) | 25 (421) | 12 (347) | |||||

| Hypothetical protein | 10 (134) | 17 (139) | ||||||

| Hypothetical protein | 21 (554) | 10 (236) | 12 (262) | 14 (271) | ||||

| Putative rve superfamily integrase | 03 (91), 04 (218) | 02 (358) | ||||||

| Putative protein-primed B-family DNA polymerase | 05 (586) | 03 (617) | ||||||

| Hypothetical protein | 06 (90) | 04 (112) | ||||||

| Hypothetical protein | 13 (286), 18 (244) | 13 (712) | ||||||

| Hypothetical protein | 14 (256) | 12 (211) | ||||||

| Hypothetical protein | 16 (210) | 09 (190) | ||||||

nt, nucleotides; aa, amino acids.

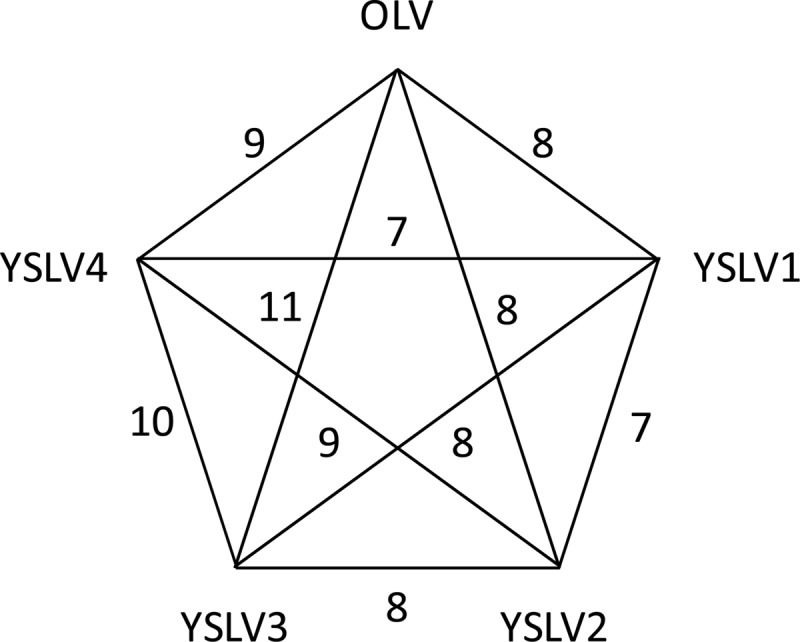

Besides these five conserved genes, the four YSLVs shared two other homologous genes with unknown functions, which were present in the OLV as well, but not in Sputnik, Mavirus, or ALM (Table 5 and Fig. 5). Interestingly, in all four YSLVs, homolog counterparts of the conserved genes of ATPase, PRSC, and mCP always showed the highest sequence similarity to that in OLV (Table 4); their second and third matches were strictly in the order of Sputnik and Mavirus. In most cases, their blast E-values were >10−5 for Mavirus hits but <10−10 for Sputnik hits. Taken together, these results suggested that the YSLVs were more closely related to OLV than to Sputnik and that they were distantly related to Mavirus.

Fig 5.

Numbers of homologous genes shared among OLV and YSLVs.

The evolutionary relationship between Mavirus and ALM was evident, as they shared 13 homologous genes (Table 4 and Fig. 4). Among them, five were virophage conserved genes, three encoded putative GIY-YIG endonuclease, putative rve (integrase core domain) superfamily integrase, and putative protein-primed B-family DNA polymerase, and five were functionally unknown. Furthermore, three syntenic regions existed between Mavirus and ALM (Fig. 4); however, two of these regions ran in opposite directions in the two virophages (Fig. 4).

Conserved gene clusters.

In this study, a gene cluster (or order) was considered to be several adjacent genes whose arrangement was conserved in some virophages; if present in all eight virophages, it was defined as a conserved gene cluster. As shown in Figures 3 and 4, a conserved gene cluster, comprised of the two conserved genes MCP and mCP, was present in all eight virophages. YSLVs 2, 3, and 4 and OLV shared a gene cluster consisting of the core gene ATPase and an ORF of unknown function. Furthermore, a gene cluster of the conserved PRIM/HEL gene and an ORF with unknown function was detected in YSLVs 3 and 4, and Mavirus and ALM had three gene clusters in common.

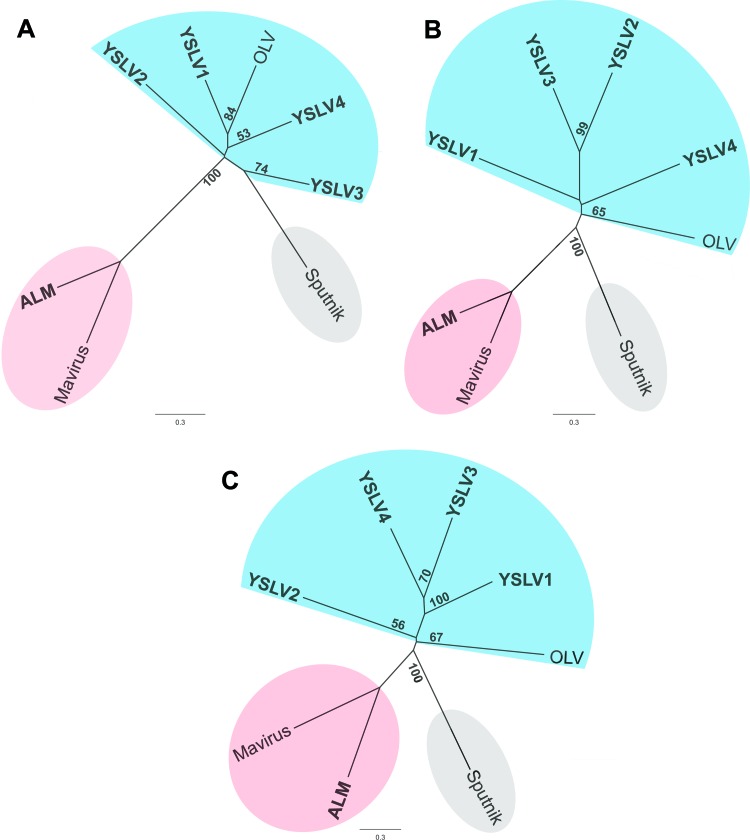

Phylogeny and evolution.

Three virophage core genes, encoding ATPase, PRSC, and MCP, were used to reconstruct the phylogenetic tree. As shown in Figure 6, three phylogenetic affiliation groups were observed. YSLVs and OLV seemed to form a group of closely related virophages, and Mavirus and ALM were apparently derived from a common ancestor, whereas Sputnik was an orphaned group. Such phylogenetic clustering of virophages was in agreement with the findings of the physical features of genomic DNA molecules, conserved genes, and gene orders as mentioned above. In addition, the phylogenetic trees of MCP and PRSC suggested that YSLVs were much closer to each other than to OLV (Fig. 6). This observation was consistent with the local tblastx results (search against a local database containing all ORFs of the eight virophages) that the best MCP hits of YSLVs were always themselves. Although it was impossible to shed light on the evolutionary relationship between these four YSLVs based on the current data, YSLVs 3 and 4 appeared to be the closest relatives. They were sister lineages on the MCP tree supported by a 70% bootstrap value (Fig. 6), shared the largest number of homologous genes (10) (Fig. 5), and had the highest number of gene clusters (three) (Fig. 3).

Fig 6.

Unrooted phylogenetic trees of DNA packaging ATPases (A), cysteine proteases (B), and major capsid proteins (C) of virophages. The five new virophages are shown in boldface. The numbers at the branches represent bootstrap values.

Habitat diversity of virophages.

Though they were more closely related to each other than to any other dsDNA viruses known so far, the habitats of these virophages were extremely diverse. Mavirus was from the coastal waters of Texas (1). Its closest relative ALM, however, was discovered in a hypersaline meromictic lake, Ace Lake (68°28′49″S, 78°11′19″E), in Antarctica. This lake is covered with ice for as long as 11 months to an entire year, with an average temperature of approximately 0°C (22). OLV was also found in the neighboring Organic Lake in Antarctica (3). In contrast, YSLVs, close to OLV, were found in a freshwater lake (Yellowstone Lake) with a temperature ranging from 12 to 73°C in Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming (23). Hence, these results indicated that virophages have adapted to habitats with a wide range of temperature variations.

In conclusion, the distinct abundance and global distribution of virophages, including almost all geographical zones as well as a variety of environments (ranging from the deep ocean to inland and iced to hydrothermal lakes), indicated that virophages appear to be widespread and genetically diverse, with at least three major lineages. Moreover, the overall low sequence similarity between the shared homologous genes in virophages and their distant phylogenetic relationships suggested that the genetic diversity of virophages is far beyond what we know thus far.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by The Program for Professor of Special Appointment (Eastern Scholar) grant 20101222 from Shanghai Institutions of Higher Learning, Shanghai Talent Development Fund grant 2011010 from Shanghai Municipal Human Resources and Social Security Bureau, and Science and Technology Development Program grant 10540503000 from Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Commission, China.

We thank two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 13 February 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.03398-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fischer MG, Suttle CA. 2011. A virophage at the origin of large DNA transposons. Science 332:231–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. La Scola B, Desnues C, Pagnier I, Robert C, Barrassi L, Fournous G, Merchat M, Suzan-Monti M, Forterre P, Koonin E, Raoult D. 2008. The virophage as a unique parasite of the giant mimivirus. Nature 455:100–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yau S, Lauro FM, DeMaere MZ, Brown MV, Thomas T, Raftery MJ, Andrews-Pfannkoch C, Lewis M, Hoffman JM, Gibson JA, Cavicchioli R. 2011. Virophage control of Antarctic algal host-virus dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:6163–6168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sun S, La Scola B, Bowman VD, Ryan CM, Whitelegge JP, Raoult D, Rossmann MG. 2010. Structural studies of the Sputnik virophage. J. Virol. 84:894–897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arslan D, Legendre M, Seltzer V, Abergel C, Claverie JM. 2011. Distant Mimivirus relative with a larger genome highlights the fundamental features of Megaviridae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:17486–17491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Raoult D, Audic S, Robert C, Abergel C, Renesto P, Ogata H, La Scola B, Suzan M, Claverie JM. 2004. The 1.2-megabase genome sequence of Mimivirus. Science 306:1344–1350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Van Etten JL, Lane LC, Dunigan DD. 2010. DNA viruses: the really big ones (giruses). Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 64:83–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Claverie JM, Abergel C. 2009. Mimivirus and its virophage. Annu. Rev. Genet. 43:49–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Raoult D, Boyer M. 2010. Amoebae as genitors and reservoirs of giant viruses. Intervirology 53:321–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fischer MG, Allen MJ, Wilson WH, Suttle CA. 2010. Giant virus with a remarkable complement of genes infects marine zooplankton. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:19508–19513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dunigan DD, Fitzgerald LA, Van Etten JL. 2006. Phycodnaviruses: a peek at genetic diversity. Virus Res. 117:119–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Desnues C, La Scola B, Yutin N, Fournous G, Robert C, Azza S, Jardot P, Monteil S, Campocasso A, Koonin EV, Raoult D. 2012. Provirophages and transpovirons as the diverse mobilome of giant viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:18078–18083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sun S, Chen J, Li W, Altintas I, Lin A, Peltier S, Stocks K, Allen EE, Ellisman M, Grethe J, Wooley J. 2011. Community cyberinfrastructure for Advanced Microbial Ecology Research and Analysis: the CAMERA resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:D546–D551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Altschul SF, Wootton JC, Gertz EM, Agarwala R, Morgulis A, Schaffer AA, Yu YK. 2005. Protein database searches using compositionally adjusted substitution matrices. FEBS J. 272:5101–5109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics 5:113 doi:10.1186/1471-2105-5-113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang Y, Bininda-Emonds OR, van Oers MM, Vlak JM, Jehle JA. 2011. The genome of Oryctes rhinoceros nudivirus provides novel insight into the evolution of nuclear arthropod-specific large circular double-stranded DNA viruses. Virus Genes 42:444–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang Y, Kleespies RG, Huger AM, Jehle JA. 2007. The genome of Gryllus bimaculatus nudivirus indicates an ancient diversification of baculovirus-related nonoccluded nudiviruses of insects. J. Virol. 81:5395–5406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Quevillon E, Silventoinen V, Pillai S, Harte N, Mulder N, Apweiler R, Lopez R. 2005. InterProScan: protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:W116–W120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guindon S, Lethiec F, Duroux P, Gascuel O. 2005. PHYML Online—a web server for fast maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic inference. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:W557–W559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Parola P, Renvoise A, Botelho-Nevers E, La Scola B, Desnues C, Raoult D. 2012. Acanthamoeba polyphaga mimivirus virophage seroconversion in travelers returning from Laos. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 18:1500–1502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Coolen MJL, Hopmans EC, Rijpstra WIC, Muyzer G, Schouten S, Volkman JK, Sinninghe Damsté JS. 2004. Evolution of the methane cycle in Ace Lake (Antarctica) during the Holocene: response of methanogens and methanotrophs to environmental change. Org. Geochem. 35:1151–1167 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Clingenpeel S, Macur RE, Kan J, Inskeep WP, Lovalvo D, Varley J, Mathur E, Nealson K, Gorby Y, Jiang H, LaFracois T, McDermott TR. 2011. Yellowstone Lake: high-energy geochemistry and rich bacterial diversity. Environ. Microbiol. 13:2172–2185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.