Abstract

B cell abnormalities contribute to the development and progress of autoimmune disease. Traditionally, the role of B cells in autoimmune disease was thought to be predominantly limited to the production of autoantibodies. Nevertheless, in addition to autoantibody production, B cells have other functions potentially relevant to autoimmunity. Such functions include antigen presentation to and activation of T cells, expression of co-stimulatory molecules and cytokine production. Recently, the ability of B cells to negatively regulate cellular immune responses and inflammation has been described and the concept of regulatory B cells has emerged. A variety of cytokines produced by regulatory B cell subsets have been reported, with IL-10 being the most studied. In this review, this specific IL-10-producing subset of regulatory B cells has been labeled B10 cells to highlight that the regulatory function of these rare B cells is mediated by IL-10, and to distinguish them from other B cell subsets that regulate immune responses through different mechanisms. B10 cells are a functionally defined subset currently identified only by their competency to produce and secrete IL-10 following appropriate stimulation. Although B10 cells share surface markers with other previously defined B cell subsets, currently there is no cell surface or intracellular phenotypic marker or set of markers unique to B10 cells. The recent discovery of an effective way to expand B10 cells ex vivo opens new horizons in the potential therapeutic applications of this rare B cell subset. This review highlights the current knowledge on B10 cells and discusses their potential as novel therapeutic agents in autoimmunity.

Introduction

Traditionally, B cells have been thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of autoimmune disease through antigen (Ag)-specfic autoantibody production [1]. Nonetheless, the role of B cells in autoimmunity extends beyond the production of autoantibodies. B cells are now well established to have both positive and negative regulatory roles during immune responses.

B cells can positively regulate immune responses by producing Ag-specfic antibody and inducing optimal T cell activation [2,3]. B cells can serve as professional Ag-presenting cells, capable of presenting Ag 103-fold to 104-fold more efficiently than nonprofessional Ag-presenting cells [4]. B cell Ag presentation is required for optimal Ag-specific CD4+ T cell expansion, memory formation, and cytokine production [5-7]. B cells may also positively regulate CD8+ T cell responses in mouse models of autoimmune disease [8,9]. Furthermore, costimulatory molecules (such as CD80, CD86, and OX40L) expressed on the surface of B cells are required for optimal T cell activation [10,11]. The positive regulatory roles of B cells extend to multiple immune system components; the absence of B cells during mouse development results in significant quantitative and qualitative abnormalities within the immune system, including a remarkable decrease in thymocyte numbers and diversity [12], significant defects within spleen dendritic cell and T cell compartments [13-15], absence of Peyer's patch organogenesis and follicular dendritic cell networks [16,17], and absence of marginal zone and metallophilic macrophages with decreased chemokine expression [15,17]. B cells also positively regulate lymphoid tissue organization [18,19]. Finally, dendritic cell, macrophage, and TH cell development may all be influenced by B cells during the formation of immune responses [20].

B cells can also negatively regulate cellular immune responses through their production of immunomodulatory cytokines. B cell-negative regulation of immune responses has been demonstrated in a variety of mouse models of autoimmunity and inflammation [21-30]. Although the identification of B cell subsets with negative regulatory functions and the definition of their mechanisms of action are recent events, the important negative regulatory roles of B cells in immune responses are now broadly recognized [31,32]. A variety of regulatory B cell subsets have been described; IL-10-producing regulatory B cells (B10 cells) are the most widely studied regulatory B cell subset [30,31,33]. Comprehensive reviews summarizing the variety of regulatory B cell subsets have been published during recent years [31,32]. The present review will therefore focus exclusively on the IL-10 producing regulatory B cell subset. This specific subset of regulatory B cells has been labeled B10 cells to highlight that the regulatory function of these rare B cells is mediated by IL-10, and to distinguish them from other B cell subsets that regulate immune responses through different mechanisms [34]. This functional subset of B cells is defined solely by its IL-10-dependent regulatory properties and extends beyond the concept of transcription factor-defined cell lineages. This review highlights our current knowledge on B10 cells, with emphasis on their roles in autoimmune disease, and discusses their potential as a novel therapeutic approach in the treatment of autoimmunity.

Biology of B10 cells

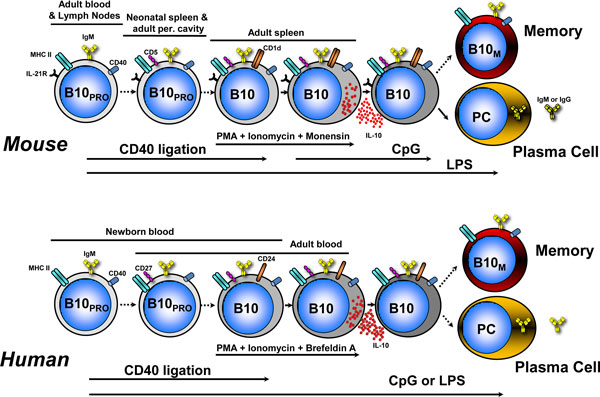

One of the most fundamental basic biology questions about B10 cells relates to the stimuli driving their development. Ag and B cell receptor (BCR) signaling are critical in early development, although additional stimuli such as CD40 ligation and Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands appear to be involved in the developmental process. Figure 1 illustrates our current understanding of B10 cell development in vivo both in mice and humans, where their development shows multiple similarities.

Figure 1.

Linear differentiation model of B10 cell development in vivo in mice and humans. B10 cells originate from a progenitor population (B10PRO). In mice, B10PRO cells are found in the CD1d−CD5− adult blood and lymph node B cell subsets and within the CD1d−CD5+ neonatal spleen and adult peritoneal cavity B cell subsets. CD40 stimulation induces B10PRO cells to become competent for IL-10 expression, while lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induces B10PRO cells to become competent for IL-10 expression and induces B10 cells to produce and secrete IL-10. CD1dhiCD5+ IL-10-competent B10 cells in the adult spleen are induced to express IL-10 following stimulation with phorbol esters (phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA)) and ionomycin or LPS plus PMA and ionomycin for 5 hours. Following a transient period of IL-10 expression, a small subset of B10 cells can differentiate into antibody-secreting plasma cells (PC). B10 cells also possibly differentiate into memory B10 cells (B10M). B10 cell development in humans appears to follow the differentiation scheme observed in mice. B10 cells and B10PRO cells have been identified in human newborn and adult blood. B10+B10PRO cells in adult human blood express CD27 and CD24. Whether human B10 cells further differentiate into PCs or B10M remains to be determined. Solid arrows, known associations; dashed arrows, speculated associations. MHC-II, major histocompatibility complex class II.

B10 cells are a functionally defined B cell subset. There are no unique phenotypic markers for B10 cells, and these cells are currently defined only by their competency to produce and secrete IL-10 following appropriate stimulation. B10 cells share surface markers with other previously defined B cell subsets both in mice and humans, such as marginal zone B cells, transitional B cells, B1a B cells, and memory B cells. However, no one marker or set of markers is unique to B10 cells. For identification of B10 cells, intracellular cytoplasmic IL-10 staining is used, following ex vivo stimulation with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or CpG oligonucleotides, phorbol esters (phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA)) and ionomycin for 5 hours [35]. B10 cells originate from a progenitor population (B10PRO cells). B10PRO cells develop into B10 cells after maturation through CD40 ligation or exposure to LPS or CpG. B10PRO cells can be identified indirectly following ex vivo stimulation with LPS or CpG in the presence of CD40 ligation for 48 hours with the addition of PMA and ionomycin for the last 5 hours. The IL-10+ B cells measured following this 48-hour stimulation include cells that would have been IL-10+ even with the shorter 5-hour stimulation (B10 cells), and thereby represent the sum of B10 plus B10PRO cells (B10+ B10PRO).

Mouse B10 cell development

BCR specificity, affinity and signaling are the most important currently identified factors in B10 cell development. B10 cell regulation of inflammation and autoimmunity is Ag specific [23,30,36]. The importance of BCR diversity is demonstrated by the fact that B10+ B10PRO cells are reduced by approximately 90% in transgenic mice with a fixed BCR [37]. Signaling through the BCR appears critical during early development in vivo. CD19-deficient mice (where BCR signaling is decreased) have a 70 to 80% decrease in B10+B10PRO cells [30]. In contrast, B10 cells are expanded in human CD19 transgenic mice (where the overexpression of CD19 augments BCR signaling). The absence of CD22, which normally dampens CD19 and BCR signaling [38], also results in increased B10 cell numbers. Ectopic B cell expression of CD40L (CD154) in transgenic mice, which induces increased CD40 signaling [39], also increases B10 cell numbers. CD22−/− mice that also ectopically express CD40L show dramatically enhanced numbers of CD1dhiCD5+ B cells and B10 cells [40]. The induction of IL-10+ B cells with regulatory activity by T cell immunoglobulin domain and mucin domain protein 1 (TIM-1) ligation [41] further highlights the importance of BCR signaling in B10 cell development. BCR signaling and TIM-1 are closely related. BCR ligation induces TIM-1 expression on B cells [41,42], and TIM-1 ligation appears to enhance BCR signaling since it increases antibody production both in vitro and in vivo [43]. The importance of BCR-related signals is further highlighted by the observation that the stromal interaction molecules 1 (STIM1) and 2 (STIM2) are required for B cell IL-10 production [44]. Remarkably, B cells lacking both stromal interaction molecule proteins failed to produce IL-10 after BCR stimulation in the presence of PMA and ionomycin for 5 hours [44]. All of the above indicate that BCR-related signals are particularly important in B10 cell development.

Despite the requirement for BCR expression and function during mouse B10 cell development, B cell stimulation with mitogenic anti-IgM antibody alone does not induce cytoplasmic IL-10 expression. The combination of anti-IgM stimulation with CD40 ligation and LPS or CpG significantly reduces IL-10 competence [37]. BCR-generated signals thus inhibit the abilities of LPS or CpG and CD40 ligation to induce cytoplasmic IL-10 production. Whether BCR stimulation inhibits the induction of IL-10 competence by inducing B cells to mature or differentiate down a divergent pathway or diverts intracellular signaling is unknown. Another possibility is that the signals generated by mitogenic anti-IgM BCR cross-linking are too intense and that low-affinity Ag--BCR interactions drive B10PRO cell development in vivo.

A recent study revealed the importance of IL-21, major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) and CD40 during cognate interactions with CD4+ T cells in B10 cell development [36]. Ex vivo stimulation of purified spleen CD19+ B cells with IL-21 induced 2.7-fold to 3.2-fold higher B10 cell frequencies, and 4.4-fold to 5.3-fold more IL-10 secretion compared with stimulation with media alone. Remarkably, IL-21 induced B10 cells to produce IL-10 without the need for stimulation with phorbol esters and ionomycin. Interestingly, IL-21 induced a threefold increase in IL-10+ B cells within the splenic CD1dhiCD5+ B cell subset, but did not induce IL-10+ B cells within the CD1dloCD5-- B cell subset. Both B10 cells and non-B10 cells expressed IL-21R at similar levels, and ex vivo B10, B10pro and CD1dhiCD5+ B cell numbers were similar among IL-21R-deficient (IL-21R--/--), MHC-II-deficient (MHC-II--/--) and CD40-deficient (CD40--/--) mice. Nevertheless, IL-21R, MHC-II and CD40 appear to be required for B10 cell effector functions, at least in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) [36]. Regulatory B10 cell function therefore requires IL-21R signaling, as well as CD40 and MHC-II interactions, potentially explaining Ag-specific B10 cell effector function [37].

Although cognate interactions with CD4+ T cells are important for B10 cell effector functions [36], T cells do not appear to be required for B10 cell development. B10 cells are present in T cell-deficient nude mice, and their frequencies and numbers are approximately fivefold higher when compared with wildtype mice. This observation is strengthened by the fact that MHC class I and MHC-II molecules and CD1d expression are not required for B10 cell development [37]. The presence or absence of T cells in vitro also does not affect the frequency of B10 cells. Although increased B10 cell frequencies in T cell-deficient mice suggest that T cells might actually inhibit B10 cell development, it is equally possible that the immunodeficient state of these mice allows subclinical inflammation that induces B10 cell generation. The role of T cells in B10 cell development in vivo is thereby complex and, although T cells are not required for B10 cell development, cognate interactions between CD4+ T cells and B10 cells are required for B10 cell effector function.

B10 cells can be driven to produce IL-10 by TLR4 (LPS) or TLR9 (CpG oligonucleotides) ligands. Mouse B10PRO cells acquire the ability to function like B10 cells after in vitro maturation following stimulation with LPS, but not CpG, in the presence or absence of agonistic CD40 mAb [32]. TLR4 and TLR9 signaling through myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88) is necessary for the optimal maturation and IL-10 induction of B10pro and B10 cells following LPS stimulation and LPS or CpG stimulation, respectively [37]. Nevertheless, MyD88 expression is not an absolute requirement for B10 cell development in vivo, since B10 cells develop normally in MyD88--/-- mice [37]. Specifically, numbers of B cells with the capacity to produce IL-10 are equivalent in wildtype and MyD88--/-- mice when their maturation or IL-10 production are measured following CD40 ligation or PMA plus ionomycin stimulation, respectively, demonstrating that B10 PRO and B10 cells are present at normal frequencies in MyD88--/-- mice. Thereby, while TLR signaling is not required for B10 cell development, MyD88 expression is required for LPS to induce optimal B cell IL-10 expression and secretion in vitro.

The involvement of TLR signals in B10-cell IL-10 production was recently demonstrated [45]. IL-10 production by B cells, stimulated by contact with apoptotic cells, results from the engagement of TLR9 within the B cell after recognition of DNA-containing complexes on the surface of apoptotic cells by the BCR. An earlier study also highlights the effects of apoptotic cells on B cell IL-10 production, where apoptotic cells protected mice from developing collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) by the induction of IL-10-producing regulatory B cells [46]. Cell death products may therefore represent one of the physiologic triggers for B10 cell development by providing a combination of BCR and TLR signals. Additional non-TLR/non-BCR signals (such as alarmins) released from dying cells may be also involved but their identities remain to be determined.

Although certain transcription factors are involved at some point in B10 cell development, it is important to stress that there is no known transcription factor signature unique to B10 cells. Following a transient period of IL-10 transcription characterized by increased expression of the blimp1 and irf4 transcription factors along with decreased expression of pax5 and bcl6, a significant but small fraction of B10 cells can differentiate into antibody-secreting cells producing IgM and IgG polyreactive antibodies that are enriched for autoreactivity to single-stranded or double-stranded DNA and histones [47]. Whether B10 cells can produce and secrete IL-10 repeatedly remains to be determined.

Human B10 cell development

B10PRO cells and B10 cells have been recently identified in humans [48] and their responses to LPS, CpG and CD40 ligation appear to follow the general scheme of mouse B10 cell development (Figure 1). One notable difference in mouse versus human B10 cell development is the lack of response of mouse B10PRO cells to CpG compared with their human counterparts. Human B10PRO cells can be driven to develop ex vivo into B10 cells with LPS or CpG stimulation, or CD40 ligation. Interestingly, BCR ligation augmented human B cell IL-10 responses to CpG in one study [49]. This finding is in discordance with our findings in both humans [48] and mice [37], where BCR-generated signals inhibit the abilities of LPS or CpG and CD40 ligation to induce cytoplasmic IL-10 production. Whether human B10 cells develop into antibody-secreting cells or enter the memory pool (memory B10 cells, B10M) remains to be determined.

Unsolved questions on B10 cell development

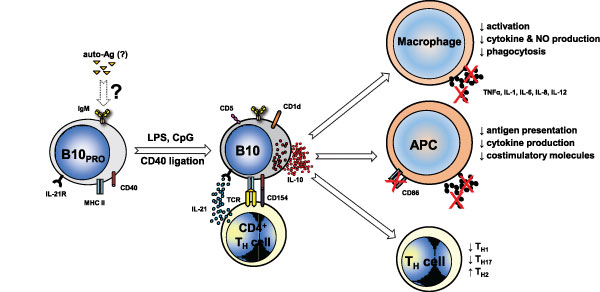

The most critical unsolved issue relates to the nature of antigenic stimuli driving B10 cell development. The identification of B10-cell BCR specificity is imperative since it will provide new insights into their early development. The autoreactive nature of mouse B10-cell BCRs [47] suggests that autoantigens may be driving early B10 cell development and that B10 cells may represent one of the ways enabling the immune system to peripherally tolerate autoantigens. B cells responding to autoantigens in an IL-10-dependent regulatory way can potentially limit inflammatory responses and limit autoimmune phenomena (see later section on B10 cell regulatory effects and Figure 2). Cell death products, by providing simultaneously both antigenic and nonantigenic stimuli, may represent one of the physiologic triggers for B10 cell development. The clearance of antigenic products of dying cells by noncomplement-fixing IgM polyreactive/autoreactive antibodies (such as those made by mouse B10 cells) in an IL-10-rich environment would be beneficial since it could potentially limit inflammatory responses to self-Ags. Additional unidentified antigenic and nonantigenic stimuli are probably involved in B10 cell development. The identification of such stimuli will provide additional insights ito B cell development that may prove invaluable for the future manipulation of B10 cells for treating autoimmune disease. Another important question is whether B10 cells enter the B cell memory pool during their development. This question is suggested by human studies demonstrating that B10PRO cells and B10 cells share phenotypic features with memory B cells (see later section on Human B10 cell phenotype).

Figure 2.

B10 cell regulatory effects in autoimmune disease. In this model, unidentified autoantigens (auto-Ags) drive early development of B10PRO cells. Following exposure to CD40 ligation and/or Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands (lipopolysaccharide (LPS), CpG), B10PRO cells mature into B10 cells that can actively secrete IL-10 and regulate both innate and adaptive immune responses. IL-21R signaling along with major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) and CD40 cognate interactions with CD4+ T cells, although not needed for B10 cell development, are necessary for B10 cell effector functions and result in antigen-specific responses. B10 cells regulate macrophage function by decreasing their activation, phagocytosis and cytokine and nitric oxide (NO) production. In antigen-presenting cells (APCs), B10-cell-negative regulation of antigen presentation, expression of co-stimulatory molecules (such as CD86) and proinflammatory cytokine production limits T cell activation. In CD4+ T helper (TH) cells, B10 cells skew responses towards a TH2 phenotype and away from TH1 and TH17 responses. The negative regulatory effects of B10 cells thereby limit inflammatory responses and subsequent tissue damage. Arrows with solid outline, known associations; arrows with dashed outline, speculated associations.

Mouse B10 cell phenotype

Although a variety of cell surface markers have been proposed [31,32], there is no known surface phenotype unique to B10 cells and, currently, the only way to identify these cells is functionally by intracellular IL-10 staining [35]. Only a small portion of B cells (that is, ~1 to 3% of splenic B cells in wildtype C57BL/6 mice) produce IL-10 following PMA and ionomycin stimulation, implying that not all B cells are competent to produce IL-10. Intracellular cytokine staining combined with flow cytometric phenotyping shows that mouse spleen B10 cells are enriched within the small CD1dhiCD5+ B cell subset, where they represent 15 to 20% of the cells in C57BL/6 mice. This phenotypically unique CD1dhiCD5+ subset shares overlapping cell surface markers with a variety of phenotypically defined B cell subsets such as CD5+ B-1a B cells, CD1dhiCD23−IgMhiCD1dhi marginal zone B cells, and CD1dhiCD23+IgMhiCD1dhi T2 marginal zone precursor B cells, which all undoubtedly contain both B10PRO cells and B10 cells [23,26,30,50]. Mouse B10 cells are predominantly IgDlowIgMhi, and <10% co-express IgG or IgA, but they can differentiate into antibody-secreting cells secreting polyreactive or Ag-specific IgM and IgG [47]. IL-10+ B cells were recently shown to be enriched in the TIM-1+ compartment and TIM-1+ B cells are enriched in the CD1dhiCD5+ compartment [41]. However, IL-10+ B cells are also present in the TIM-1-- compartment and TIM-1+ B cells are present in the non-CD1dhiCD5+ compartment. Intracellular cytoplasmic IL-10 staining thereby remains the only current way to visualize the entire subset of IL-10-competent B cells. Nonetheless, the isolation of CD1dhiCD5+ B cells or other phenotypically defined B cell subsets where B10 cells are enriched currently provides the best current means for isolating a viable B cell population that is significantly enriched for B10 cells and can be used for adoptive transfer experiments and functional studies in mice.

Human B10 cell phenotype

The IL-10-producing B cell subset characterized in humans normally represents <1% of peripheral blood B cells [48]. Peripheral blood B10 cells and B10PRO cells are highly enriched in the CD24hiCD27+ B cell subset, with approximately 60% also expressing CD38. Similar total numbers of IL-10+ B cells have been described in the CD24hiCD38hi and CD24intCD38int B cell subsets [51]. A separate study showed that B10 cells did not fall within any of the previously defined B cell subsets, but they were enriched in the CD27+ and the CD38hi compartments [49]. Human B10 cells also highly express CD48 and CD148 [48]. CD48 is a B cell activation marker [52] and CD148 is considered a marker for human memory B cells [53]. CD27 expression is another well-characterized marker for memory B cells, although some memory B cells may be CD27-- [54-56]. The CD27+ B cell subset can also expand during the course of autoimmunity and has been proposed as a marker for disease activity [54,56]. The CD24hiCD148+ phenotype of B10 cells and B10PRO cells may thereby indicate their selection into the memory B cell pool during development, or they may represent a distinct B cell subset that shares common cell surface markers with memory B cells. Consistent with a memory phenotype, the proliferative capacity of human blood B10 cells in response to mitogen stimulation is higher than that for other B cells [48], as is seen for mouse B10 cells [37]. Human transitional B cells are rare (2 to 3% of B cells) in adult human blood and are generally CD10+CD24hiCD38hi cells that are also CD27-negative [55,56]; since CD10 expression is a well-accepted marker for most cells within the transitional B cell pool [57], its absence on B10 cells suggests that these cells are not recent emigrants from the bone marrow. In summary, human B10 cells share phenotypic characteristics with other previously defined B cell subsets, and, currently, there is no known surface phenotype unique to B10 cells.

B10 cell regulatory effects

B10 cells exert a variety of IL-10-dependent regulatory effects potentially involved in autoimmune disease. The anti-inflammatory effects of IL-10 are mediated by multiple mechanisms involving both the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system. In innate cells, these mechanisms include downregulation of proinflammatory cytokine production [58] and decreased expression of MHC-II and co-stimulatory molecules [59] resulting in decreased T cell activation. B10 cells negatively regulate the ability of dendritic cells to present Ag [60]. In CD4+ T cells, IL-10 suppresses TH1 [50] and enhances TH2 polarization [41,59]. B10 cells suppress IFNγ and TNFα responses in vitro [60] and INFγ responses in vivo [36] by Ag-specific CD4+ T cells. Co-culture of mouse CD1dhiCD5+ B cells with CFSE-labeled naive CD4+ T cells suppresses TH17 cell differentiation [61] and IL-10 is known to suppress TH17 responses [62]. The suppression of TH17 responses by B10 cells in vivo was demonstrated recently [36]. IL-10 production by human B10 cells inhibits Ag-specific CD4+CD25-- T cell proliferation [49] and regulates monocyte activation and cytokine production [48]in vitro.

A number of studies suggest that IL-10-producing B cells are important for the generation and/or maintenance of the regulatory T cell (TREG) pool [46,63-72]. However, a recent study [73] and our previously published data [23] do not support this view. The reason for this discrepancy is unclear but may be related to the different models of inflammation and conditions used to study the relationship of B10 cells and TREGS. These two studies suggesting that B10 cells are not involved in the generation and maintenance of the TREG pool are both in models of EAE [23,73]. In contrast, only one study suggests that B10 cells are important for the generation and/or maintenance of the TREG pool specifically in EAE [63]. The results of a different study clarify the picture in EAE further by showing that a subset of regulatory B cells control TREG numbers through IL-10-independent mechanisms [34]. Human B10 cell IL-10 production will therefore probably also have pleiotropic regulatory effects on the immune system, as occurs in mice. The potential regulatory effects of B10 cells in autoimmune disease limiting inflammatory responses and subsequent tissue damage are summarized in Figure 2.

B10 cells in human autoimmune disease

Studies of B10 cells and human autoimmune disease are limited but of outmost importance since they provide valuable insights relevant to the potential future therapeutic application of B10 cells in humans. Peripheral blood B10 cells and B10PRO cells are present in patients with autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, primary Sjögren's syndrome, autoimmune bullous diseases, and multiple sclerosis. Interestingly, B10+B10PRO cell frequencies are expanded in some but not all cases, while mean B10+ B10PRO cell frequencies are significantly higher in patients with autoimmune disease compared with age-matched healthy controls [48]. A different study examined cytoplasmic IL-10 production by B cells from systemic lupus erythematosus patients and normal controls [74]. Blood mononuclear cells were cultured for 24 hours in the presence or absence of PMA, ionomycin, or LPS; significantly more systemic lupus erythematosus CD5+ B cells produced cytoplasmic IL-10 than did controls. A different study also demonstrated spontaneous B cell IL-10 production that is higher in untreated rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, and systemic lupus erythematosus patients than in controls [75].

By contrast, the concept of functional impairment of B10 cells in autoimmune disease was recently introduced by demonstrating functional impairment of CD24hiCD38hi regulatory B cells in human systemic lupus erythematosus [51]. Cultures of peripheral blood mononuclear cells were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 mAb for 72 hours, followed by the measurement of IFNγ and TNFα CD4+ T cell responses. When CD24hiCD38hi B cells were removed from the culture, higher frequencies of CD4+IFNγ+ and CD4+TNFα+ T cells were noted in healthy individuals but not in systemic lupus erythematosus patients; this effect was partially IL-10 dependent. In addition, CD24hiCD38hi B cells isolated from the peripheral blood of systemic lupus erythematosus patients were refractory to CD40 ligation and produced less IL-10 compared with their healthy counterparts. The results of this study are rather intriguing but these findings need to be validated in view of the complexity of the culture system used and the non-uniformity of the CD24hiCD38hi B cell subset with regards to its IL-10-dependent regulatory properties. In conclusion, B10 cells are present in the peripheral blood of autoimmune disease patients, where they appear to be expanded, whereas the functional capacity of human B10 cells in autoimmunity needs to be further defined.

B10 cells in mouse models of autoimmune disease

The important regulatory effects of B10 cells in vivo and their therapeutic potential in autoimmunity have been demonstrated in a variety of mouse models of human autoimmune disease.

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

EAE is an established model of multiple sclerosis induced by immunization with myelin peptides (such as myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein) leading to demyelination mediated by auto-Ag-specific CD4+ T cells [76,77]. B cells were shown over a decade ago to have regulatory properties during the induction of EAE, with genetically B cell-deficient mice developing a severe nonremitting form of the disease [21]. However, these B cell regulatory effects were recently shown not to be IL-10 dependent [34]. Nonetheless, other studies highlight the importance of B cell-derived IL-10 in EAE. Specifically, EAE severity during the late phase of disease increases in B cell-deficient μMT mice that do not fully recover from their disease when compared with wildtype mice, and the adoptive transfer of wildtype B cells but not IL-10--/-- B cells normalizes EAE severity in μMT mice [22]. Disease recovery is dependent on the presence of autoantigen-reactive B cells, and B cells isolated from mice with disease produced IL-10 in response to autoantigen stimulation. In the absence of Ag-specific B cell IL-10 production, the proinflammatory TH1-mediated immune responses persist and mice do not recover from the disease.

The EAE model demonstrates the complexity of regulatory mechanisms mediated by different cell subsets during different stages of the disease. When B cells from wildtype mice are depleted by CD20 mAb treatment 7 days before EAE induction, there is an increased influx or expansion of encephalitogenic T cells within the central nervous system and exacerbation of disease symptoms [23]. This effect is related to B10 cell depletion since similar effects are observed with selective B10 depletion by means of CD22 mAb [60]. The adoptive transfer of Ag-specific (myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-sensitized) B10 cells into wildtype mice also reduces EAE initiation dramatically. The protective effect is IL-10 dependent since the adoptive transfer of CD1dhiCD5+ B cells purified from IL-10−/− mice does not affect EAE severity. B10 cell effector functions in EAE require IL-21 along with cognate interactions with CD4+ T cells since the adoptive transfer of CD1dhiCD5+ B cells into CD19--/-- mice from IL-21R--/--, MHC-II--/-- or CD40--/-- mice prior to the induction of EAE does not alter disease course [36]. Once disease is established, adoptive transfer of B10 cells does not suppress ongoing EAE. B10 cells thereby appear to normally regulate acute autoimmune responses in EAE. In contrast to the role of B10 cells in early disease, TREG depletion enhances late-phase disease. Therefore, in EAE, depending on the stage of the disease, different regulatory mechanisms are involved in limiting inflammatory responses, with B10 cells regulating disease initiation and TREGS being involved predominantly in the regulation of late-phase disease.

Inflammatory bowel disease

IL-10-producing B cells regulate intestinal inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease [26]. Early studies showed that B cells and their autoantibody products suppress colitis in T cell receptor alpha chain-deficient mice that spontaneously develop chronic colitis, while B cells are not required for disease initiation [78]. B cells with upregulated CD1d expression in the gut-associated lymphoid tissues of mice with intestinal inflammation were subsequently demonstrated to be regulatory [25]. This IL-10-producing B cell subset appears during chronic inflammation in T cell receptor alpha chain-deficient mice and suppresses the progression of intestinal inflammation by downregulating inflammatory cascades associated with IL-1 upregulation and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (stat3) activation rather than by altering polarized TH cell responses. The adoptive transfer of these mesenteric lymph node B cells also suppresses inflammatory bowel disease through a mechanism that correlates with an increase in TREG subsets [67]. Oral administration of dextran sulfate sodium solution to mice is widely used as a model of human ulcerative colitis. Dextran sulfate sodium-induced intestinal injury is more severe in CD19--/-- mice (where B10 cells are absent) than in wildtype mice [79], and these inflammatory responses are negatively regulated by CD1dhiCD5+ B cells producing IL-10. B10 cells therefore emerge during chronic inflammation in mouse models of inflammatory bowel disease, where they suppress the progression of inflammatory responses and ameliorate disease manifestations.

Collagen-induced arthritis

CIA is a model for human rheumatoid arthritis that develops in susceptible mouse strains immunized with heterologous type II collagen emulsified in complete Freund's adjuvant [80,81]. CIA and rheumatoid arthritis share in common an association with a limited number of MHC-II haplotypes that determine disease susceptibility [82,83]. B cells are important for initiating inflammation and arthritis since mature B cell depletion significantly reduces disease severity prior to CIA induction but does not inhibit established disease [84]. Several studies on CIA demonstrate the negative regulatory effects and therapeutic potential of B10 cells.

Activation of arthritogenic splenocytes with Ag and agonistic anti-CD40 mAb induces a B cell population that produces high levels of IL-10 and low levels of IFNγ [85]. The adoptive transfer of these B cells into DBA/1--T cell receptor--β-Tg mice, immunized with bovine collagen (type II collagen) emulsified in complete Freund's adjuvant, inhibits TH1 responses, prevents arthritis development, and is effective in ameliorating established disease. The adoptive transfer of CD21hiCD23+IgM+ B cells from DBA/1 mice in the remission phase prevents CIA and reduces disease severity through IL-10 secretion [86]; a significant but less dramatic therapeutic effect on CIA progression is seen when cells from naïve mice are adoptively transferred. In addition, the adoptive transfer of ex vivo expanded CD1dhiCD5+ B cells in collagen-immunized mice delays arthritis onset and reduces disease severity, accompanied by a substantial reduction in the number of TH17 cells [61]. Co-culture of CD1dhiCD5+ B cells with naive CD4+ T cells suppresses TH17 cell differentiation in vitro, and co-culture of CD1dhiCD5+ B cells with TH17 cells results in decreased proliferation responses in vitro. Furthermore, the adoptive transfer of TH17 cells triggers CIA in IL-17--/-- DBA mice; however, when TH17 cells are co-transferred with CD1dhiCD5+ B cells, the onset of CIA is significantly delayed. Finally, in a different study, administration of apoptotic thymocytes along with ovalbumin peptide and complete Freund's adjuvant to mice carrying an ovalbumin-specific rearranged T cell receptor transgene (DO11.10 mice) up to 1 month before the onset of CIA resulted in an increase in ovalbumin-specific IL-10 secretion and is protective for severe joint inflammation and bone destruction [46]. Activated spleen B cells responded directly to apoptotic cell treatment in vitro by increasing secretion of IL-10, and inhibition of IL-10 in vivo reversed the beneficial effects of apoptotic cell treatment [46].

Systemic lupus erythematosus

B cell-negative regulatory effects are important in NZB/W mice, a spontaneous lupus model, since mature B cell depletion initiated in 4-week-old NZB/W F1 mice hastens disease onset, which parallels depletion of B10 cells [87]. B10 cells are phenotypically similar in NZB/W F1 and C57BL/6 mice, but are expanded significantly in young NZB/W F1 mice [87]. In wildtype NZB/W mice, the CD1dhiCD5+B220+ B cell subset, which is enriched in B10 cells, is increased 2.5-fold during the disease course, whereas CD19--/-- NZB/W mice lack this CD1dhiCD5+ regulatory B cell subset [88]. Finally, the potential therapeutic effect of B10 cells in lupus is highlighted by the prolonged survival of CD19--/-- NZB/W recipients following the adoptive transfer of splenic CD1dhiCD5+ B cells from wildtype NZB/W mice [88]. Studies in the NZB/W spontaneous lupus model therefore suggest that B10 cells have protective and potentially therapeutic effects.

In the MRL.Fas(lpr) mouse lupus model, B cell-derived IL-10 does not regulate spontaneous autoimmunity [89]. B cell-specific deletion of IL-10 in MRL.Fas(lpr) mice indicates that B cell-derived IL-10 is ineffective in suppressing the spontaneous activation of self-reactive B cells and T cells during lupus. The severity of organ disease and survival rates in mice harboring IL-10-deficient B cells were unaltered. MRL.Fas(lpr) IL-10 reporter mice illustrate that B cells comprise only a small fraction of the pool of IL-10-competent cells. In contrast to previously published studies from our laboratory and elsewhere, putative regulatory B cell phenotypic subsets, such as CD1dhiCD5+ and CD21hiCD23hi B cells, were not enriched in IL-10 transcription. This observation suggests fundamental differences in the pathogenesis and immune dysregulation in the NZB/W lupus model compared with the MRL.Fas(lpr) model.

Type 1 diabetes

Studies on B10 cells and mouse models of diabetes are limited to the nonobese diabetic (NOD) mouse, a spontaneous model of type 1 diabetes in which autoimmune destruction of the insulin-producing pancreatic β cells is primarily T cell mediated [90]. Although B cells clearly have a pathogenic role in disease initiation [91], B cells activated in vitro can maintain tolerance and transfer protection from type 1 diabetes in NOD mice [92,93]. The adoptive transfer of BCR-stimulated B cells into NOD mice starting at 5 to 6 weeks of age both delays the onset and reduces the incidence of type 1 diabetes, while treatment at 9 weeks of age delays disease onset. Protection from type 1 diabetes requires B cell IL-10 production since the adoptive transfer-activated NOD-IL-10--/-- B cells do not confer protection from type 1 diabetes or the severe insulitis in NOD recipients. The therapeutic effect of adoptively transferred activated NOD B cells correlates with TH2 polarization. The limited data above suggest that B10 cells may be protective in preventing establishment of type 1 diabetes in NOD mice.

Therapeutic potential of B10 cells

Harvesting the anti-inflammatory properties of B10 cells can provide a new approach to the treatment of autoimmunity. Manipulation of this subset for treating autoimmune disease is possible by either selective depletion of mature B cells while sparing B10/B10PRO cells or the selective expansion of B10 cells. Since there are no identified surface molecules specific for non-B10/B10PRO cells, it is currently impossible to selectively target and deplete mature B cells while sparing B10/B10PRO cells. B10 cell expansion appears to be a more viable approach since some of the stimuli driving their development have been identified. B10 cells can be expanded for therapeutic purposes either in vivo or ex vivo. Expansion of B10 cells in vivo by means of agonistic CD40 antibody has shown benefit in CIA [85]. However, expanding B10 cells in vivo carries additional risks since the currently identified stimuli driving B10 cell development are rather nonspecific and, if administered systemically, will trigger responses in a variety of immune cells. For example, the systemic administration of agonistic CD40 antibodies in humans has been associated with serious adverse effects such as cytokine release syndrome [94]. In summary, selective depletion of mature B cells while sparing B10/B10PRO cells is not currently possible, and in vivo B10 cell expansion by nonspecific agents such as agonistic CD40 antibody is potentially associated with serious off-target effects.

Expanding B10 cells ex vivo appears more preferable than in vivo B10 cell expansion by nonspecific agents because it offers a potential therapy without the risk of undesirable nonspecific off-target effects. However, ex vivo B10 cell expansion introduces new challenges related to the method of expansion, to the magnitude of expansion and to the time it takes to generate B10 numbers that will be sufficient for therapeutic use. The method of ex vivo B10 cell expansion can be the source of safety concerns when it comes to human applications. Large numbers of regulatory B cells have been successfully generated in mice by means of genetic manipulation of immature B cells through lentiviral transfection [95]. These cells were effective in treating EAE. However, although this method can efficiently generate large numbers of regulatory B cells ex vivo, concerns remain about administering infusions of lentivirus-infected B cells to humans (with retroviral and infectious potential). Safety concerns thereby limit the use of infectious agents in manipulating human cells, which could render this approach inappropriate for use in humans.

The magnitude of ex vivo B10 cell expansion is very important since the number of cells infused during adoptive transfer experiments is critical. In humans, the most convenient potential source of B10/B10PRO cells prior to ex vivo expansion is obviously peripheral blood. Since B10/B10PRO cells are rare in peripheral blood and there are limitations on the volume that can be drawn at any given time, a method of expanding B10 cells by several million-fold is needed. Furthermore, since this method will be used for treatment of active disease, the time it will take to expand these cells ex vivo is also of great significance; ideally, this process should not take more than 1 or 2 weeks. There is accumulating hope that such an approach will soon be available for human cells since mouse B10 cell ex vivo expansion can be accomplished within 9 days by means of combined CD154, B-lymphocyte stimulator, IL-4 and IL-21 stimulation [36]. After the 9-day culture period, B10 cell numbers are increased 4,000,000-fold, with 38% of the B cells actively producing IL-10. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting based on CD5 expression increases the B10 cell purity to75%, thus providing not only large numbers of B10 cells but also a B cell population predominantly consisting of B10 cells. These ex vivo expanded B10 cells are very effective in limiting inflammatory responses in EAE. This approach appears promising since it provides an effective way of generating large numbers of B10 cells without the use of infectious agents. The development of a similar system for expanding human B10 cells is of outmost importance.

Conclusion

The phenotypic and functional characterization of B10 cells is an important advance for the regulatory B cell field. Numerous additional functionally defined subsets of regulatory B cells will probably be identified in the future. B10 cells share phenotypic markers with a variety of previously defined subsets, but their only unique phenotypic marker is intracellular IL-10 production. Although certain transcription factors are involved at different points in B10 cell development, there is currently no transcription factor signature unique to B10 cells. BCR-related signals are most critical in B10 cell development and the finding of B10-cell BCR auto-reactivity suggests that autoantigens may be of particular importance. The recent discovery of an in vitro method to efficiently expand mouse B10 cells provides an invaluable tool for studying the basic biology of B10 cells as well as manipulating them for therapeutic purposes. The development of a similar method for human cells will open new opportunities for studying the basic biology of human B10 cells and a promising novel approach in treating human autoimmune disease, potentially without undesirable off-target effects.

Abbreviations

Ag: antigen; B10 cells: IL-10-producing regulatory B cells; BCR: B cell receptor; CIA: collagen-induced arthritis; EAE: experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis; IFN: interferon; IL: interleukin; LPS: lipolysaccharide; mAb: monoclonal antibody; MHC: major histocompatibility complex; MyD88: myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88; NOD: nonobese diabetic; PMA: phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate; TH: T-helper; TIM-1: T cell immunoglobulin domain and mucin domain protein 1; TLR: Toll-like receptor; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; TREG: regulatory T cell.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Declarations

This article has been published as part of Arthritis Research & Therapy Volume 15 Supplement 1, 2013: B cells in autoimmune diseases: Part 2. The supplement was proposed by the journal and content was developed in consultation with the Editors-in-Chief. Articles have been independently prepared by the authors and have undergone the journal's standard peer review process. Publication of the supplement was supported by Medimmune.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank colleagues and collaborators for their contributions. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI56363 and AI057157), the Lymphoma Research Foundation and the Arthritis Foundation (Clinical to Research Transition Award, project number 5577).

References

- Lipsky PE. Systemic lupus erythematosus: an autoimmune disease of B cell hyperactivity. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:764–766. doi: 10.1038/ni0901-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBien TW, Tedder TF. B-lymphocytes: how they develop and function. Blood. 2008;112:1570–1579. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-078071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo DJ, Hamaguchi Y, Ueda Y, Yang K, Uchida J, Haas KM, Kelsoe G, Tedder TF. Maintenance of long-lived plasma cells and serological memory despite mature and memory B cell depletion during CD20 immunotherapy in mice. J Immunol. 2008;180:361–371. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Wu Y, Ramarathinam L, Guo Y, Huszar D, Trounstine M, Zhao M. Gene-targeted B-deficient mice reveal a critical role for B cells in the CD4 T cell response. Int Immunol. 1995;7:1353–1362. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.8.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton PJ, Harbertson J, Bradley LM. A critical role for B cells in the development of memory CD4 cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:5558–5565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford A, Macleod M, Schumacher T, Corlett L, Gray D. Primary T cell expansion and differentiation in vivo requires antigen presentation by B cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:3498–3506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouaziz JD, Yanaba K, Venturi GM, Wang Y, Tisch RM, Poe JC, Tedder TF. Therapeutic B cell depletion impairs adaptive and autoreactive CD4+ T cell activation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20882–20887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709205105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homann D, Tishon A, Berger DP, Weigle WO, von Herrath MG, Oldstone MB. Evidence for an underlying CD4 helper and CD8 T cell defect in B cell-deficient mice: failure to clear persistent virus infection after adoptive immunotherapy with virus-specific memory cells from μMT/μMT mice. J Virol. 1998;72:9208–9216. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9208-9216.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann CC, Ramakrishna C, Kornacki M, Stohlman SA. Impaired T cell immunity in B cell-deficient mice following viral central nervous system infection. J Immunol. 2001;167:1575–1583. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill SK, Cao Y, Hamel KM, Doodes PD, Hutas G, Finnegan A. Expression of CD80/86 on B cells is essential for autoreactive T cell activation and the development of arthritis. J Immunol. 2007;179:5109–5116. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton PJ, Bautista B, Biederman E, Bradley ES, Harbertson J, Kondrack RM, Padrick RC, Bradley LM. Costimulation via OX40L expressed by B cells is sufficient to determine the extent of primary CD4 cell expansion and Th2 cytokine secretion in vivo. J Exp Med. 2003;197:875–883. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joao C, Ogle BM, Gay-Rabinstein C, Platt JL, Cascalho M. B cell-dependent TCR diversification. J Immunol. 2004;172:4709–4716. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AbuAttieh M, Rebrovich M, Wettstein PJ, Vuk-Pavlovic Z, Limper AH, Platt JL, Cascalho M. Fitness of cell-mediated immunity independent of repertoire diversity. J Immunol. 2007;178:2950–2960. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulin V, Andris F, Thielemans K, Maliszewski C, Urbain J, Moser M. B lymphocytes regulate dendritic cell (DC) function in vivo: increased interleukin 12 production by DCs from B cell-deficient mice results in T helper cell type 1 deviation. J Exp Med. 2000;192:475–482. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo VN, Cornall RJ, Cyster JG. Splenic T zone development is B cell dependent. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1649–1660. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.11.1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golovkina TV, Shlomchik M, Hannum L, Chervonsky A. Organogenic role of B lymphocytes in mucosal immunity. Science. 1999;286:1965–1968. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley MT, Reilly CR, Lo D. Influence of lymphocytes on the presence and organization of dendritic cell subsets in the spleen. J Immunol. 1999;163:4894–4900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumanov A, Kuprash D, Lagarkova M, Grivennikov S, Abe K, Shakhov A, Drutskaya L, Stewart C, Chervonsky A, Nedospasov S. Distinct role of surface lymphotoxin expressed by B cells in the organization of secondary lymphoid tissues. Immunity. 2002;17:239–250. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00397-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez M, Mackay F, Browning JL, Kosco-Vilbois MH, Noelle RJ. The sequential role for lymphotoxin and B cells in the development of splenic follicles. J Exp Med. 1998;187:997–1007. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Liu Z, Rozo CT, Hamed HA, Alem F, Urban JF Jr, Gause WC. The role of B cells in the development of CD4 effector T cells during a polarized Th2 immune response. J Immunol. 2007;179:3821–3830. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf SD, Dittel BN, Hardardottir F, Janeway CA Jr. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis induction in genetically B cell-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2271–2278. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillatreau S, Sweenie CH, McGeachy MJ, Gray D, Anderton SM. B cells regulate autoimmunity by provision of IL-10. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:944–950. doi: 10.1038/ni833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita T, Yanaba K, Bouaziz J-D, Fujimoto M, Tedder TF. Regulatory B cells inhibit EAE initiation in mice while other B cells promote disease progression. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3420–3430. doi: 10.1172/JCI36030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillatreau S, Gray D, Anderton SM. Not always the bad guys: B cells as regulators of autoimmune pathology. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:391–397. doi: 10.1038/nri2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi A, Mizoguchi E, Takedatsu H, Blumberg RS, Bhan AK. Chronic intestinal inflammatory condition generates IL-10-producing regulatory B cell subset characterized by CD1d upregulation. Immunity. 2002;16:219–230. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00274-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi A, Bhan AK. A case for regulatory B cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:705–710. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauri C, Ehrenstein MR. The 'short' history of regulatory B cells. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund FE. Cytokine-producing B lymphocytes -- key regulators of immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:332–338. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouaziz J-D, Yanaba K, Tedder TF. Regulatory B cells as inhibitors of immune responses and inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2008;224:201–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanaba K, Bouaziz J-D, Haas KM, Poe JC, Fujimoto M, Tedder TF. A regulatory B cell subset with a unique CD1dhiCD5+ phenotype controls T cell-dependent inflammatory responses. Immunity. 2008;28:639–650. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauri C, Bosma A. Immune regulatory function of B cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:221–241. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo DJ, Matsushita T, Tedder TF. B10 cells and regulatory B cells balance immune responses during inflammation, autoimmunity, and cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1183:38–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistoia V. Production of cytokines by human B cells in health and disease. Immunol Today. 1997;18:343–350. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(97)01080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray A, Basu S, Williams CB, Salzman NH, Dittel BN. A novel IL-10-independent regulatory role for B cells in suppressing autoimmunity by maintenance of regulatory T cells via GITR ligand. J Immunol. 2012;188:3188–3198. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita T, Tedder TF. Identifying regulatory B cells (B10 cells) that produce IL-10. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;677:99–111. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-869-0_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizaki A, Miyagaki T, Dilillo DJ, Matsushita T, Horikawa M, Kountikov EI, Spolski R, Poe JC, Leonard WJ, Tedder TF. Regulatory B cells control T cell autoimmunity through IL-21-dependent cognate interactions. Nature. 2012;491:264–268. doi: 10.1038/nature11501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanaba K, Bouaziz JD, Matsushita T, Tsubata T, Tedder TF. The development and function of regulatory B cells expressing IL-10 (B10 cells) requires antigen receptor diversity and TLR signals. J Immunol. 2009;182:7459–7472. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedder TF, Poe JC, Haas KM. CD22: a multi-functional receptor that regulates B lymphocyte survival and signal transduction. Adv Immunol. 2005;88:1–50. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(05)88001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi T, Aiba Y, Nomura T, Matsuda J, Mochida K, Suzuki M, Kikutani H, Honjo T, Nishioka K, Tsubata T. Cutting edge: ectopic expression of CD40 ligand on B cells induces lupus-like autoimmune disease. J Immunol. 2002;168:9–12. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poe JC, Smith S-H, Haas KM, Yanaba K, Tsubata T, Matsushita T, Tedder TF. Amplified B lymphocyte CD40 signaling drives regulatory B10 cell expansion in mice. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22464. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Q, Yeung M, Camirand G, Zeng Q, Akiba H, Yagita H, Chalasani G, Sayegh MH, Najafian N, Rothstein DM. Regulatory B cells are identified by expression of TIM-1 and can be induced through TIM-1 ligation to promote tolerance in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3645–3656. doi: 10.1172/JCI46274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong SH, Barlow JL, Nabarro S, Fallon PG, McKenzie AN. Tim-1 is induced on germinal centre B cells through B cell receptor signalling but is not essential for the germinal centre response. Immunology. 2010;131:77–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Usui Y, Takeda K, Harada N, Yagita H, Okumura K, Akiba H. TIM-1 signaling in B cells regulates antibody production. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;406:223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, Fujii Y, Baba A, Hikida M, Kurosaki T, Baba Y. The calcium sensors STIM1 and STIM2 control B cell regulatory function through interleukin-10 production. Immunity. 2011;34:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles K, Heaney J, Sibinska Z, Salter D, Savill J, Gray D, Gray M. A tolerogenic role for Toll-like receptor 9 is revealed by B cell interaction with DNA complexes expressed on apoptotic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:887–892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109173109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray M, Miles K, Salter D, Gray D, Savill J. Apoptotic cells protect mice from autoimmune inflammation by the induction of regulatory B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:14080–14085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700326104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maseda D, Smith SH, DiLillo DJ, Bryant JM, Candando KM, Weaver CT, Tedder TF. Regulatory B10 cells differentiate into antibody-secreting cells after transient IL-10 production in vivo. J Immunol. 2012;188:1036–1048. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata Y, Matsushita T, Horikawa M, DiLillo DJ, Yanaba K, Venturi GM, Szabolcs PM, Bernstein SH, Magro CM, Williams AD, Hall RP, St Clair EW, Tedder TF. Characterization of a rare IL-10-competent B cell subset in humans that parallels mouse regulatory B10 cells. Blood. 2011;117:530–541. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-294249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouaziz JD, Calbo S, Maho-Vaillant M, Saussine A, Bagot M, Bensussan A, Musette P. IL-10 produced by activated human B cells regulates CD4(+) T cell activation in vitro. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:2686–2691. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra P, Santamaria P. To 'B' regulated: B cells as members of the regulatory workforce. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair PA, Norena LY, Flores-Borja F, Rawlings DJ, Isenberg DA, Ehrenstein MR, Mauri C. CD19+CD24hiCD38hi B cells exhibit regulatory capacity in healthy individuals but are functionally impaired in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Immunity. 2010;32:129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama S, Staunton D, Fisher R, Amiot M, Fortin JJ, Thorley-Lawson DA. Expression of the Blast-1 activation/adhesion molecule and its identification as CD48. J Immunol. 1991;146:2192–2200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangye SG, Liu Y-J, Aversa G, Phillips JH, de Vries JE. Identification of functional human splenic memory B cells by expression of CD148 and CD27. J Exp Med. 1988;188:1691–1703. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.9.1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz I, Wei C, Lee FE-H, Anolik J. Phenotypic and functional heterogeneity of human memory B cells. Sem Immunol. 2008;20:67–82. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein U, Rajewsky K, Kuppers R. Human immunoglobulin (lg)M+IgD+ peripheral blood B cells expressing the CD27 cell surface antigen carry somatically mutated variable region genes: CD27 as a general marker for somatically mutated (memory) B cells. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1679–1689. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.9.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agematsu K, Hokibara S, Nagumo H, Komiyama A. CD27: a memory B cell marker. Immunol Today. 2000;21:204–206. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(00)01605-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardemann H, Yurasov S, Schaefer A, Young JW, Meffre E, Nussenzweig MC. Predominant autoantibody production by early human B cell precursors. Science. 2003;301:1374–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1086907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraiva M, O'Garra A. The regulation of IL-10 production by immune cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:170–181. doi: 10.1038/nri2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asadullah K, Sterry W, Volk HD. Interleukin-10 therapy -- review of a new approach. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55:241–269. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.2.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita T, Horikawa M, Iwata Y, Tedder TF. Regulatory B cells (B10 cells) and regulatory T cells have independent roles in controlling EAE initiation and late-phase immunopathogenesis. J Immunol. 2010;185:2240–2252. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M, Deng J, Liu Y, Ko KH, Wang X, Jiao Z, Wang S, Hua Z, Sun L, Srivastava G, Lau CS, Cao X, Lu L. IL-10-producing regulatory B10 cells ameliorate collagen-induced arthritis via suppressing Th17 cell generation. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:2375–2385. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Yang J, Ouyang X, Liu W, Li H, Bromberg J, Chen SH, Mayer L, Unkeless JC, Xiong H. Interleukin 10 suppresses Th17 cytokines secreted by macrophages and T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1807–1813. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann MK, Maresz K, Shriver LP, Tan Y, Dittel BN. B cell regulation of CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells and IL-10 via B7 is essential for recovery from experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2007;178:3447–3456. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter NA, Vasconcellos R, Rosser EC, Tulone C, Munoz-Suano A, Kamanaka M, Ehrenstein MR, Flavell RA, Mauri C. Mice lacking endogenous IL-10-producing regulatory B cells develop exacerbated disease and present with an increased frequency of Th1/Th17 but a decrease in regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2011;186:5569–5579. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayi A, Kohler E, Toller IM, Flavell RA, Muller W, Roers A, Muller A. TLR-2- activated B cells suppress Helicobacter-induced preneoplastic gastric immunopathology by inducing T regulatory-1 cells. J Immunol. 2011;186:878–890. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair PA, Chavez-Rueda KA, Evans JG, Shlomchik MJ, Eddaoudi A, Isenberg DA, Ehrenstein MR, Mauri C. Selective targeting of B cells with agonistic anti-CD40 is an efficacious strategy for the generation of induced regulatory T2-like B cells and for the suppression of lupus in MRL/lpr mice. J Immunol. 2009;182:3492–3502. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei B, Velazquez P, Turovskaya O, Spricher K, Aranda R, Kronenberg M, Birnbaumer L, Braun J. Mesenteric B cells centrally inhibit CD4+ T cell colitis through interaction with regulatory T cell subsets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2010–2015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409449102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amu S, Saunders SP, Kronenberg M, Mangan NE, Atzberger A, Fallon PG. Regulatory B cells prevent and reverse allergic airway inflammation via FoxP3-positive T regulatory cells in a murine model. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:1114–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadmor T, Zhang Y, Cho HM, Podack ER, Rosenblatt JD. The absence of B lymphocytes reduces the number and function of T-regulatory cells and enhances the anti-tumor response in a murine tumor model. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60:609–619. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-0972-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun JB, Flach CF, Czerkinsky C, Holmgren J. B lymphocytes promote expansion of regulatory T cells in oral tolerance: powerful induction by antigen coupled to cholera toxin B subunit. J Immunol. 2008;181:8278–8287. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangan NE, Fallon RE, Smith P, van Rooijen N, McKenzie AN, Fallon PG. Helminth infection protects mice from anaphylaxis via IL-10-producing B cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:6346–6356. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.10.6346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahangarani RR, Janssens W, VanderElst L, Carlier V, VandenDriessche T, Chuah M, Weynand B, Vanoirbeek JA, Jacquemin M, Saint-Remy JM. In vivo induction of type 1-like regulatory T cells using genetically modified B cells confers long-term IL-10-dependent antigen-specific unresponsiveness. J Immunol. 2009;183:8232–8243. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehlig K, Shen P, Lampropoulou V, Roch T, Malissen B, O'Connor R, Ries S, Hilgenberg E, Anderton SM, Fillatreau S. Activation of CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells proceeds normally in the absence of B cells during EAE. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:1164–1173. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amel Kashipaz MR, Huggins ML, Lanyon P, Robins A, Powell RJ, Todd I. Assessment of Be1 and Be2 cells in systemic lupus erythematosus indicates elevated interleukin-10 producing CD5+ B cells. Lupus. 2003;12:356–363. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu338oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorente L, Richaud-Patin Y, Fior R, Alcocer-Varela J, Wijdenes J, Fourrier BM, Galanaud P, Emilie D. In vivo production of interleukin-10 by non-T cells in rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren's syndrome, and systemic lupus erythematosus. A potential mechanism of B lymphocyte hyperactivity and autoimmunity. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:1647–1655. doi: 10.1002/art.1780371114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettinelli CB, McFarlin DE. Adoptive transfer of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in SJL/J mice after in vitro activation of lymph node cells by myelin basic protein: requirement for Lyt 1+ 2-- T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1981;127:1420–1423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KC, Ulvestad E, Hickey WF. Immunology of multiple sclerosis. Clin Neurosci. 1994;2:229–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi A, Mizoguchi E, Smith RN, Preffer FI, Bhan AK. Suppressive role of B cells in chronic colitis of T cell receptor α mutant mice. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1749–1756. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.10.1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanaba K, Yoshizaki A, Asano Y, Kadono T, Tedder TF, Sato S. IL-10-producing regulatory B10 cells inhibit intestinal injury in a mouse model. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:735–743. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trentham DE, Townes AS, Kang AH. Autoimmunity to type II collagen an experimental model of arthritis. J Exp Med. 1977;146:857–868. doi: 10.1084/jem.146.3.857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay JS, Dallman MJ, Dayan AD, Martin A, Mosedale B. Immunisation against heterologous type II collagen induces arthritis in mice. Nature. 1980;283:666–668. doi: 10.1038/283666a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wordsworth BP, Lanchbury JS, Sakkas LI, Welsh KI, Panayi GS, Bell JI. HLA-DR4 subtype frequencies in rheumatoid arthritis indicate that DRB1 is the major susceptibility locus within the HLA class II region. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:10049–10053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.10049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunsberg U, Gustafsson K, Jansson L, Michaelsson E, Ahrlund-Richter L, Pettersson S, Mattsson R, Holmdahl R. Expression of a transgenic class II Ab gene confers susceptibility to collagen-induced arthritis. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:1698–1702. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanaba K, Hamaguchi Y, Venturi GM, Steeber DA, St.Clair EW, Tedder TF. B cell depletion delays collagen-induced arthritis in mice: arthritis induction requires synergy between humoral and cell-mediated immunity. J Immunol. 2007;179:1369–1380. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauri C, Gray D, Mushtaq N, Londei M. Prevention of arthritis by interleukin 10-producing B cells. J Exp Med. 2003;197:489–501. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JG, Chavez-Rueda KA, Eddaoudi A, Meyer-Bahlburg A, Rawlings DJ, Ehrenste in MR, Mauri C. Novel suppressive function of transitional 2B cells in experimental arthritis. J Immunol. 2007;178:7868–7878. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas KM, Watanabe R, Matsushita T, Nakashima H, Ishiura N, Okochi H, Fujimoto M, Tedder TF. Protective and pathogenic roles for B cells during systemic autoimmunity in NZB/W F1 mice. J Immunol. 2010;184:4789–4800. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe R, Ishiura N, Nakashima H, Kuwano Y, Okochi H, Tamaki K, Sato S, Tedder TF, Fujimoto M. Regulatory B cells (B10 cells) have a suppressive role in murine lupus: CD19 and B10 cell deficiency exacerbates systemic autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2010;184:4801–4809. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teichmann LL, Kashgarian M, Weaver CT, Roers A, Muller W, Shlomchik MJ. B cell -derived IL-10 does not regulate spontaneous systemic autoimmunity in MRL.Fas(lpr) mice. J Immunol. 2012;188:678–685. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MS, Bluestone JA. The NOD mouse: a model of immune dysregulation. Ann u Rev Immunol. 2005;23:447–485. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiu Y, Wong CP, Hamaguchi Y, Wang Y, Pop S, Tisch RM, Tedder TF. B lymphocytes depletion by CD20 monoclonal antibody prevents diabetes in NOD mice despite isotype-specific differences in FcγR effector functions. J Immunol. 2008;180:2863–2875. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain S, Delovitch TL. Intravenous transfusion of BCR-activated B cells protects NOD mice from type 1 diabetes in an IL-10-dependent manner. J Immunol. 2007;179:7225–7232. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J, Zekzer D, Hanssen L, Lu Y, Olcott A, Kaufman DL. Lipopolysaccharide-activated B cells down-regulate Th1 immunity and prevent autoimmune diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 2001;167:1081–1089. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.2.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonderheide RH, Flaherty KT, Khalil M, Stumacher MS, Bajor DL, Hutnick NA, Sullivan P, Mahany JJ, Gallagher M, Kramer A, Green SJ, O'Dwyer PJ, Running KL, Huhn RD, Antonia SJ. Clinical activity and immune modulation in cancer patients treated with CP-870,893, a novel CD40 agonist monoclonal antibody. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:876–883. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderon-Gomez E, Lampropoulou V, Shen P, Neves P, Roch T, Stervbo U, Rutz S, Kuhl AA, Heppner FL, Loddenkemper C, Anderton SM, Kanellopoulos JM, Charneau P, Fillatreau S. Reprogrammed quiescent B cells provide an effective cellular therapy against chronic experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:1696–1708. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]