Abstract

The xenocin operon of Xenorhabdus nematophila consists of xciA and ximB genes encoding a 64-kDa xenocin and 42-kDa immunity protein to kill competing microbes in the insect larva. The catalytic domain of xenocin has RNase activity and is responsible for its cytotoxicity. Under SOS conditions, xenocin is produced with immunity protein as a complex. Here, we show that xenocin and immunity protein complex are exported through the flagellar type III system of X. nematophila. Secretion of xenocin complex was abolished in an flhA strain but not in an fliC strain. The xenocin operon is not linked to the flagellar operon transcriptionally. The immunity protein is produced alone from a second, constitutive promoter and is targeted to the periplasm in a flagellum-independent manner. For stable expression of xenocin, coexpression of immunity protein was necessary. To examine the role of immunity protein in xenocin export, an enzymatically inactive protein was produced by site-directed mutagenesis in the active site of the catalytic domain. Toxicity was abolished in D535A and H538A variants of xenocin, which were expressed alone without an immunity domain and secreted in the culture supernatant through flagellar export. Secretion of xenocin through the flagellar pathway has important implications in the evolutionary success of X. nematophila.

INTRODUCTION

Xenorhabdus nematophila is a Gram-negative gammaproteobacterium that resides in the gut of the soil nematode Steinernema carpocapsae as a symbiont (1). The bacterium produces potent cytotoxins (2–5) and orally toxic proteins to kill larval stages of insect pests (6, 7). After the death of the larva, the bacterium secretes a variety of antibiotic molecules (8–10) to kill putrefying microbes for optimum growth of the nematode. In addition, a number of effector proteins are also released by the bacterium to communicate with and manipulate its hosts (11); however, secretion pathways of very few have been elucidated to date. We have described an insect-toxic outer membrane vesicle complex from the culture supernatant of X. nematophila containing multiple virulence factors (12), and an extracellular lipase, XlpA, was shown to be exported through the flagellum by this bacterial pathogen (13).

Bacteriocins are antimicrobial peptides produced by bacteria under environmental stress conditions, e.g., high population density and nutrient depletion (14). A cognate immunity protein (IP) is coinduced from an SOS-responsive promoter to protect the producer cell from the lethal effect of the bacteriocin (15). The bacteriocin and IP remain associated as a complex until the toxin enters the target cell (16, 17). In operons encoding nuclease bacteriocins, two different promoters regulate IP synthesis: an inducible SOS promoter and a constitutive promoter that allows constant production of IP to ensure inactivation of the incoming bacteriocins (15, 18).

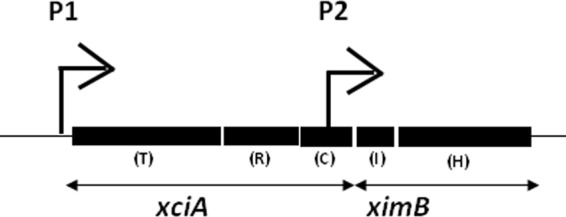

Earlier we described a gene pair constituting the xenocin operon of X. nematophila (19). The first locus, xciA (XNC1_3261), encoded a 64-kDa xenocin with RNase activity followed by ximB encoding the cognate immunity protein. The 42-kDa IP is constituted by a 10-kDa immunity domain in the N terminus and a C-terminal 32-kDa putative hemolysin domain (Fig. 1). The two genes were transcribed as a single mRNA by an SOS inducible promoter located upstream of the xciA gene. Additionally, ximB was transcribed alone from a constitutive promoter present in the 5′-untranslated sequence of the gene (19) (Fig. 1). Generally, bacteriocin-IP complexes are released from the producer cell with the help of a lysis or lysis-inducing protein located in the same operon in group A members (15) or through an ABC transporter in group B members (20). Since none of the genes mentioned above was present in the proximity of the xenocin operon, it was presumed that secretion of xenocin occurred though an atypical pathway.

Fig 1.

Schematic representation of xenocin operon xciA and ximB genes. P1, inducible promoter; P2, constitutive promoter; T, translocation domain; R, receptor binding domain; C, catalytic domain; I, immunity domain; H, hemolysin domain.

Bacteria have adopted a variety of mechanisms to translocate effector proteins across the cell envelop. The secretion systems have been classified as types I to VII (21). In addition to the well-established pathways, secretion of toxins also occurs commonly through membrane blebs in many pathogenic bacteria (22). There are two protein export machineries exclusive and inbuilt into bacterial organelle biogenesis system, the chaperon-usher system for translocation and assembly of pilin subunits (23) and flagellar biogenesis on the cell surface. In both the cases the nascent subunit proteins are exported through a dedicated system in a sequential manner for assembly of the mature organelle. The export of flagellar subunits directly from the cytoplasm to the cell surface resembles the contact-dependent type III secretion of Gram-negative bacteria. Some of the common features, e.g., homology in the sequence of the subunits and secretion of substrates without modification, reflects functional similarities between the two systems. The flagellar secretory system exports a number of effector proteins/virulence factors in addition to flagellar components out of the cell (13, 24–26). However, data regarding recognition and targeting of potential substrates to the flagellar secretory machinery are conflicting and not very well defined (27–29).

Screening of the X. nematophila genome for secretion systems revealed the total absence or redundancy of major protein secretory pathways in this insect pathogen and predicted that flagellar export apparatus and type Vb systems identified in the genome play a wider role in effector protein export (30). Thus, in the light of the clues obtained from genomic analysis of X. nematophila, this study was conducted to explore the involvement of the flagellar type III secretory system in xenocin export. Our results demonstrate that under SOS conditions, xenocin-IP is translocated as a complex through the flagellar pathway in X. nematophila.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and culture conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. X. nematophila 19061 and xciA, flhA, fliA, and fliC mutant strains of X. nematophila were maintained on LB medium containing appropriate antibiotics. Ampicillin was used at 50 μg/ml, kanamycin at 25 μg/ml, and chloramphenicol at 25 μg/ml as required. All of the Xenorhabdus strains were grown for 24 h at 30°C, and E. coli strains were grown for 14 to 16 h at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm for procedures requiring general growth. For secretion-related experiments, strains were grown without shaking in 2× LB medium at 30°C for 16 to 18 h. The plasmid pJQ200SK+ was maintained in E. coli DH5α, which was grown in LB medium with 5 μg/ml gentamicin. Escherichia coli S-17.1 was used to conjugally transfer the plasmids to X. nematophila. E. coli strain pLysS was used as the indicator strain for bactericidal activity. The plasmid vector pGEM-T Easy, from Promega (Madison, WI), was used for PCR cloning. pCR-XL-TOPO and pBCSK(+) were used for cloning and complementation studies. The data presented here are representative of experiments performed at least 2 to 3 times with all the strains.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in the study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEM-T Easy vector | 3.0-kb PCR cloning vector, Ampr | Promega |

| pBC SK(+) | 3.4-kb cloning vector, Cmr | Stratagene |

| pJQ200 SK+ | Gmr, sacB, Rp4 mob, R6K ori | 31 |

| pCR-XL-TOPO(+) | 3.5-kb PCR cloning vector, kanr | Invitrogen |

| pXAB | pBCSK(+) containing xciA and ximB loci with 5′-UTR containing promoter | This study |

| pXA | pBCSK(+) containing xciA loci with 5′-UTR containing promoter | This study |

| pFlhBA | pCR-XL-TOPO containing flhBA operon | This study |

| ptac-pBCSK | pBCSK(+) vector containing tac promoter | This study |

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | supE44ΔlacU169 hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 Φ80dlacZ ΔM15 | Invitrogen |

| BL21(DE3)/pLysS | F− ompT hsdSB (rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3)/pLysS (Cmr) | Novagen |

| S.17–1 | Donor host for r6K ori conjugant | MTCC, India |

| pimm/Pimm | ximB with 5′UTR in pGEM-T Easy vector in DH5α | This study |

| X. nematophila strains and plasmids | ||

| ATCC 19061 | Wild type, phase I variant, Ampr | Laboratory stock |

| 19061 xciA | X. nematophila xciA::kan | This study |

| 19061 xciA+ | X. nematophila xciA containing pXAB or pXA | This study |

| 19061 flhA | X. nematophila flhA::cam | 13 |

| 19061 flhA+ | X. nematophila flhA::cam containing 4.16-kb flhBA in pCR-XL-TOPO(+) vector | This study |

| 19061 fliC | X. nematophila fliC::cam | 13 |

| 19061 fliA | X. nematophila fliA::cam | 13 |

| pPS1/PS1 | ptac-pBCSK containing 2.9 kb xciA and ximB genes in xciA-null mutant strain | This study |

| pPS2/PS2 | ptac-pBCSK containing 1.7 kb xciA in xciA-null mutant strain | This study |

| pPS3/PS3 | pPS2 with D535A mutation in xciA-null mutant strain | This study |

| pPS4/PS4 | pPS2 with H538A mutation in xciA-null mutant strain | This study |

Preparation of cytosolic and extracellular proteins from Xenorhabdus strains.

X. nematophila strains were grown at 30°C as static cultures until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reached 0.4 to 0.5 and induced with 0.25 μg/ml mitomycin C for 2 to 3 h for xenocin expression. After induction, samples were collected at different time points and centrifuged, and the supernatant was passed through a nonpyrogenic 0.22-μm-pore-size filter. Extracellular proteins were precipitated with 10% (wt/vol) ice-cold trichloroacetic acid at 4°C for 3 h and centrifuged, and the pellet was resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0. The cell pellet from 1 to 2 ml of culture was boiled for 5 min in sample loading dye and centrifuged, and the supernatant was loaded in the gel.

Cellular fractionation.

Different cellular fractions of X. nematophila containing cytoplasmic, outer membrane, and periplasmic proteins were prepared as described earlier (7) and were analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies of xenocin and immunity protein. All of the subcellular fractions were checked for the respective markers; alkaline phosphatase as a periplasmic marker, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (32) and GroES as cytoplasmic markers, and OpnP as an outer membrane marker were used to validate the fractions.

Preparation of flagella.

Flagella were isolated from cells grown in LB medium as described before (33) and induced with mitomycin C for 2 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and suspended in 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5), vortexed for 5 min, and centrifuged to remove the cells. The supernatant containing the flagella was filtered to remove floating cells. The supernatant was centrifuged at 75,000 rpm for 40 min. The pellet was washed repeatedly and resuspended in 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride.

Immunoprecipitation.

The protein fractions from wild-type X. nematophila were incubated with anti-IP serum for 1 h at room temperature, followed by addition of protein A-Sepharose beads for an hour at room temperature. The beads were centrifuged, washed thoroughly, boiled in SDS-PAGE sample buffer, and resolved by gel electrophoresis. Western blotting was performed with antibodies against xenocin and a nontarget protein, GroES.

Bacteriostatic activity of different cellular fractions.

Growth-inhibitory activity of the preparations was determined in indicator plates prepared by overlying 3 ml of soft nutrient agar, containing E. coli indicator cells, grown in M9 medium on LB agar plates. The cellular fractions were filter sterilized and applied on sterile filter paper discs placed on the surface. The plates were incubated at 37°C overnight, and the clearance zone was recorded.

RT-PCR of flagellar genes.

X. nematophila cultures were induced with mitomycin C as described above for 2.5 h. The culture was centrifuged and total RNA was isolated from the cells using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen) as described before (19). The RNA was treated with DNase and checked by PCR for DNA contamination. A 50-μl reaction mixture was set up with 800 ng of purified RNA using a Qiagen one-step reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) kit and primers shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The reaction was amplified for 25 cycles.

Construction of xciA-null strain of X. nematophila.

The 1.7-kb xciA gene was amplified by PCR using X. nematophila genomic DNA as the template and primers 1 and 3 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) as described before (19). The PCR-amplified fragment was cloned in the pGEM-T Easy vector, producing pxciA. Similarly, a 1.5-kb kanamycin cassette was amplified using plasmid pJH101 (34) as the template and cloned in pGEM-T Easy vector. The kanamycin cassette was excised and ligated at the unique BglII site in the pxciA-generating pPSA. The 3.2-kb fragment containing the disrupted xciA gene was excised from pPSA with BamHI and SalI and ligated to plasmid pJQ200SK+ at complementary sites. The resulting plasmid, pPSB, was electroporated into E. coli S-17.1, producing strain PSB. pPSB in E. coli S17.1 was conjugally transferred into X. nematophila as described earlier (35). The allelic replacement in Kmr Cms exconjugants was verified by PCR amplification and Southern analysis.

To complement the xciA mutant, a 3.7-kb DNA fragment containing both xciA and ximB genes with the native promoter was amplified using primers XciAB F (879 bp upstream of the start codon of the xciA locus) and primer 2 and was cloned in the pCR-XL-TOPO(+) vector, producing pAB. pAB DNA was digested with BamHI and PstI, and the released fragment was ligated in pBCSK(+) at complementary sites, producing pXAB construct, which was chemically transformed in the xciA mutant as described earlier (36). The xciA mutant was also complemented with the xciA gene alone. A 2.6-kb DNA fragment containing xciA with 5′-untranslated promoter sequence was amplified using primer XciAB F and primer 3 and cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector. The DNA was digested with BamHI and HindIII, and the fragment was subcloned in pBCSK(+) vector. The construct pXA was chemically transformed in the xciA mutant as described earlier (36).

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

Ten to 20 μg of total protein from different strains was loaded in the gel, and all the lanes in one gel contained the same amount of protein. The proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting. The blots were developed with polyclonal antibodies raised against the proteins. Xenocin and IP antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:4,000 and 1:5000, respectively, and the proteins were detected with nitroblue tetrazolium-5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate substrate.

Cloning of ximB with 5′ untranslated sequence and expression of immunity protein in E. coli DH5α cells.

ximB sequence with 300 bp of the 5′-untranslated region (UTR) containing its promoter was PCR amplified using primers ximB-UTR and ximB RP and cloned in pGEM-T Easy vector. The resulting plasmid pimm was transformed in E. coli DH5α cells and IP synthesis was examined in different cellular fractions of an overnight grown culture, without induction.

Construction of xenocin variants in a heterologous vector and expression in X. nematophila.

A heterologous ptac-pBCSK vector was produced by ligating the tac promoter at the XbaI and BamHI site of pBCSK(+) (Stratagene). The tac promoter was obtained from pGEX-4T1 (GE Health Care Life Sciences) vector by PCR amplification, using TacF and TacR primers. The DNAs encoding different protein variants (see Fig. 8A) were amplified by PCR using primers shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material, cloned at BamHI and HindIII sites of ptac-pBCSK vector, and transformed in E. coli DH5α cells. The plasmid DNAs pPS1 to pPS4 were prepared from E. coli and transformed into a chemically competent xciA mutant strain of X. nematophila (Table 1). All of the strains were grown as static cultures in 2× LB medium at 30°C, and log-phase cells (OD600 of 0.4 to 0.5) were induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 2 h. Samples were taken and processed as described above and analyzed by Western blotting.

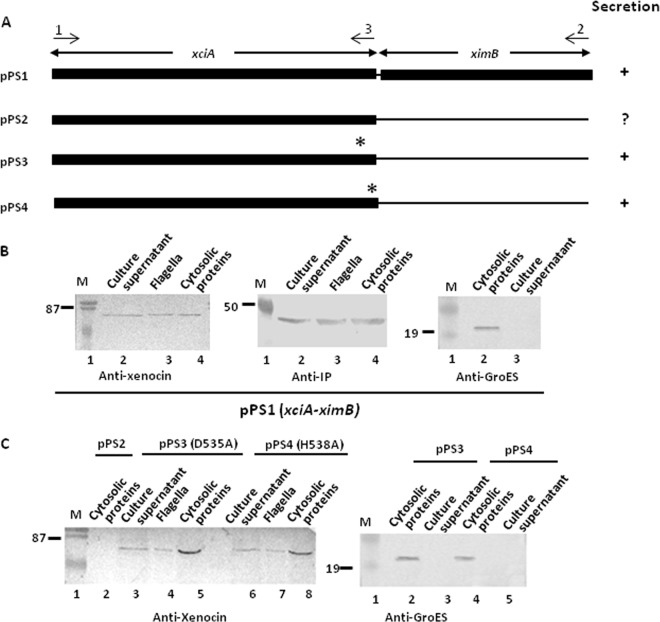

Fig 8.

(A) Schematic representation of xciA-ximB constructs. Filled boxes represent the DNA sequences present in the constructs. An asterisk denotes the altered amino acid. Arrows and numbers above them indicate the positions of the primers. For secretion analysis, different DNA constructs were tested in the xciA mutant by Western blotting. Strains were induced with IPTG for 2 to 3 h, cells were separated, and flagella were prepared. Proteins in the culture supernatant were precipitated with 10% TCA. All of the cell pellets and supernatant fractions were probed with anti-GroES antibodies as controls for cell lysis. Lane M, low-range, prestained molecular mass markers (in kDa). (B) Xenocin operon. (C) Xenocin variants D535A and H538A.

Mutation of active-site residues of xenocin.

A homology model was generated based on the structure of bacteriocin E3 of E. coli (37) using http://www.fundp.ac.be/urbm/bioinfo/esypred/. Six key residues (D535, H538, E542, H551, K564, and R570) in the active site of RNase (xenocin) were altered to alanine by site-directed mutagenesis to produce nontoxic xenocin. For mutagenesis, the 1.7-kb xciA DNA was used as the template with primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), and the altered DNAs were expressed in E. coli cells. These strains were tested for growth, and the variant proteins were analyzed by CD spectra. The nontoxic variants D535A and H538A of xciA were able to grow like the vector control, and the wild-type genes were subcloned in ptac-pBCSK vector and transformed in the xciA knockout strain of X. nematophila. The proteins were induced by 1 mM IPTG for 2 h as described above and examined by Western blotting.

RESULTS

Detection of xenocin and IP in cellular fractions after induction of X. nematophila.

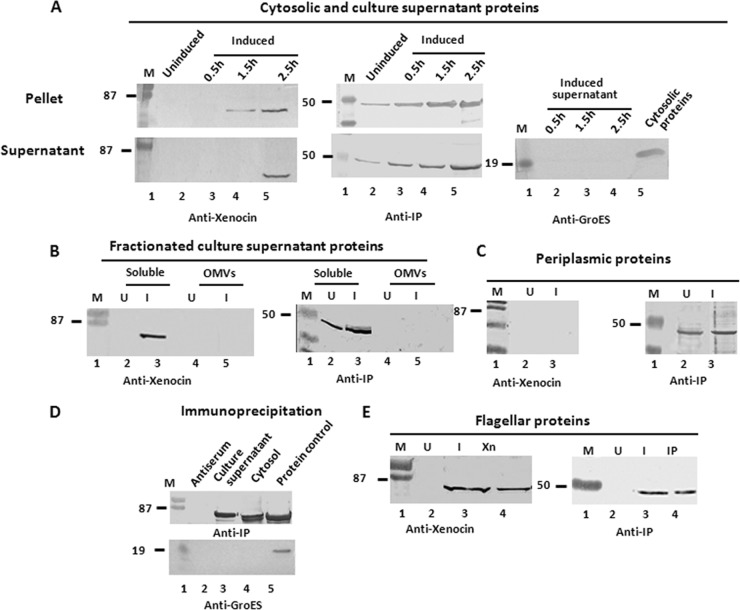

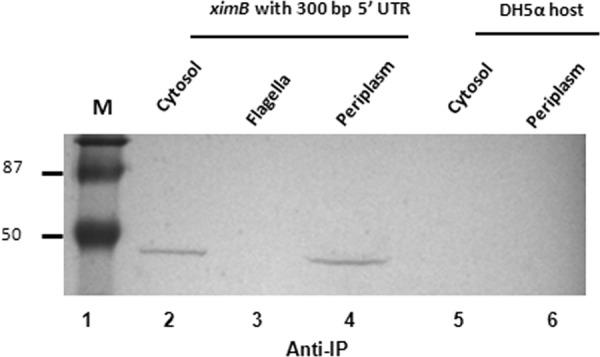

To determine the secretion pathway of the xenocin-IP complex, different cellular and extracellular fractions were examined. Induction of SOS response in the wild-type X. nematophila cells with mitomycin C resulted in synthesis and release of both xenocin and immunity proteins in the soluble fraction (obtained after ultracentrifugation of the culture supernatant), while GroES, a cytosolic protein marker, was not detected (Fig. 2A). The OD600 and CFU/ml in the induced culture was not very different (0.40 and 3 × 107, respectively) from those of the uninduced culture (0.42 and 5 × 107, respectively) after 2.5 h; in addition, release of an intracellular enzyme, glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, in the culture supernatant was negligible relative to intracellular levels (2.1 U/mg protein). This suggested that xenocin was exported by a specific pathway and not by cell lysis. Neither xenocin nor immunity protein was detected in the outer membrane or outer membrane vesicles (Fig. 2B). The IP was present alone in the periplasmic fraction of both induced and uninduced cells. No xenocin was detected in the periplasm under either condition (Fig. 2C). The presence of IP in the periplasm of uninduced cells indicated that it is produced constitutively and released in the culture supernatant by a yet-unknown mechanism. We have shown earlier (19) that the xenocin operon had two promoters: the SOS-inducible P1, upstream of the xciA gene, produced a bicistronic transcript, and P2, upstream of ximB, constitutively produced a smaller RNA (Fig. 1). To demonstrate specific targeting of constitutively produced IP to the periplasm, a plasmid containing the ximB locus with its constitutive, upstream promoter sequence in the pGEM-T Easy vector was produced and transformed in E. coli DH5α cells. Examination of proteins localized in different cellular fractions showed the presence of IP in the cytosol and periplasm but not in the flagella of transformed cells grown overnight. No protein was detected in the untransformed host cells (Fig. 3). Immunoprecipitation of the cytoplasmic and culture supernatant proteins of wild-type X. nematophila with antibody against IP demonstrated that xenocin and IP were present as a complex in both fractions (Fig. 2D).

Fig 2.

Secretion analysis of xenocin and IP in wild-type X. nematophila by Western blotting. (A) The cells were induced with 0.25 μg/ml mitomycin C for 2 to 3 h, and total secreted proteins were separated from the cell pellet and precipitated with 10% TCA. The cell pellet and culture supernatant fractions were analyzed using antibodies against xenocin, IP, and GroES. (B) Total culture supernatant proteins were fractionated, and xenocin and IP were detected in different fractions with their respective antibodies. OMV, outer membrane vesicles. (C) Xenocin and IP were detected in the periplasmic fraction with their respective antibodies. (D) Cytosolic and culture supernatant proteins from induced culture of X. nematophila were immunoprecipitated with antiserum against IP and protein A-Sepharose beads, followed by SDS-PAGE and blotting with anti-xenocin antibodies or anti-GroES as a nontarget control. (E) Flagella were prepared from cells grown in LB broth, induced, and incubated under stationary conditions. Xn, purified xenocin; IP, purified IP; U, uninduced; I, induced. Lane M, low-range, prestained molecular mass markers (in kDa; Bio-Rad).

Fig 3.

Export of constitutively expressed immunity protein. E. coli DH5α cells containing the ximB locus with an 5′-upstream promoter sequence in pGEM-T Easy vector was grown overnight. Cytosolic, periplasmic, and flagellar proteins were prepared without induction. The fractions were analyzed with antibody against IP. Lane M, low-range, prestained molecular mass markers (in kDa).

Bioinformatic analysis of xenocin polypeptide sequence showed neither a leader sequence nor any motifs involved in protein export (38, 39). To get an idea of the probable export pathway, we proceeded to determine the N-terminal sequence of the processed protein, purified from the culture supernatant of recombinant M15 E. coli by ammonium sulfate precipitation, followed by SP Sepharose column chromatography. However, attempts to purify xenocin protein repeatedly failed due to copurification of FliC protein of E. coli (identified by its N-terminal sequence). This suggested an association of xenocin with the flagella as a possible route of export. Hence, to examine the involvement of the flagellar system in xenocin export, flagella were prepared from wild-type X. nematophila cells after induction with mitomycin C. Protein analysis by Western blotting identified both xenocin and IP in the flagella from induced cells only (Fig. 2E); none of the proteins were detected in the flagella of uninduced cells (Fig. 2E). The association of xenocin and IP with flagella is not due to cosedimentation during high-speed centrifugation of flagella, as immunogold labeling of Xenorhabdus cell or isolated flagella with xenocin antibody showed negligible binding by transmission electron microscopy (unpublished results), suggesting the presence of the proteins within the flagellar fiber. Antibacterial activity was also detected in the flagellar preparation from induced cells; none of the proteins or bioactivity was observed in the flagella from uninduced cells, demonstrating close association of xenocin complex with the flagella of X. nematophila.

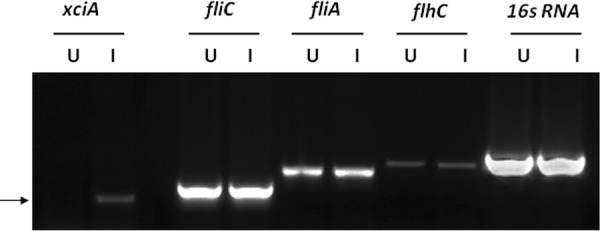

Flagellar genes are not regulated by mitomycin C.

To examine the effect of mitomycin C on the flagellar operon, total RNA from mitomycin-induced X. nematophila cells was subjected to semiquantitative RT-PCR, and relative abundances of flhC, fliA, fliC, and xciA genes were measured. The results showed that mitomycin C specifically upregulated xciA transcription only, and none of the flagellar genes were affected in that time period, demonstrating independent control of the two gene clusters (Fig. 4).

Fig 4.

RT-PCR analysis of flagellar genes after induction with mitomycin C. Total RNA was prepared from X. nematophila cells after induction, and mRNA levels were analyzed. U, uninduced; I, induced. Arrow shows the xciA amplicon.

Analysis of protein secretion by xciA mutant.

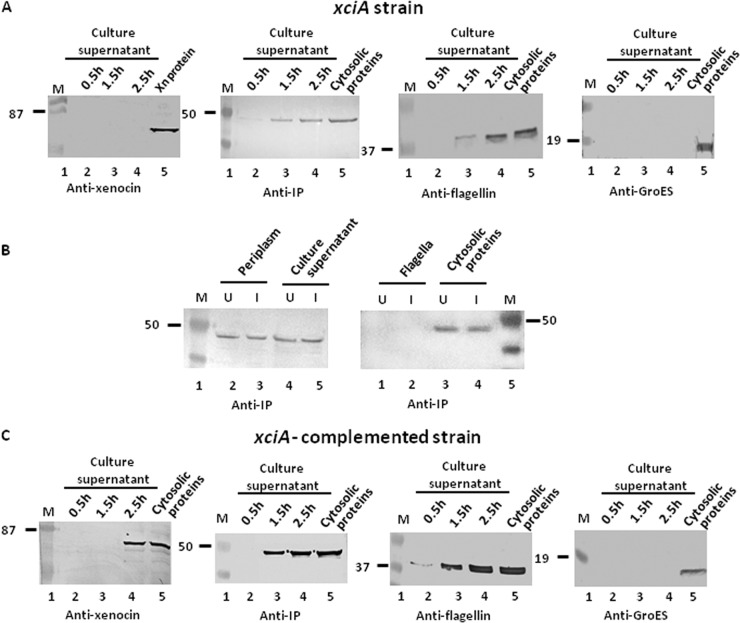

To ascertain that xenocin is indeed responsible for the observed antibacterial activity and is secreted through the flagellar system, the xciA gene was insertionally inactivated by allelic exchange. After induction of the SOS response with mitomycin C for 2.5 h, the OD600 and CFU/ml counts in the culture (0.46 and 4.5 × 107, respectively) were similar to those of uninduced culture (0.53 and 5.2 × 107, respectively). The cells produced no xenocin in the culture supernatant (Fig. 5A). However, IP was produced alone, with or without induction, and was detected in the cytosol, periplasmic fraction, and culture supernatant, similar to the wild-type strain (Fig. 5B). In the uninduced cells, IP was synthesized from the constitutive promoter P2 (not affected by polar effect due to disruption of xciA) and targeted to the periplasm and the culture supernatant (Fig. 5B). After induction, amounts of IP in the fractions described above were similar to those of uninduced conditions (Fig. 5B), indicating no additional synthesis from the inducible promoter, P1. Unlike the case for the wild-type strain, IP was not detected in the flagella under any condition, with or without induction, in the xciA null mutant strain (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that (i) due to disruption of the xciA gene, no IP was produced from the inducible P1 promoter; and (ii) for localization of IP in the flagellum, either a P1 mRNA or a xenocin-IP complex is required. The IP synthesized constitutively from P2 is expressed but not targeted to the flagella (Fig. 3). Similarly, consistent with the absence of xenocin and IP from the flagellar preparation, no antibacterial activity was observed after induction with mitomycin C (Table 2). Complementation of the mutant with xciA-ximB sequence restored xenocin protein expression in the culture supernatant (Fig. 5C) and bactericidal activity in the flagella (Table 2). However, complementation with xciA alone was toxic for the cell. The cell density was very low compared to that of the noncomplemented strain after 20 h of growth, and no xenocin could be detected in the induced cells (data not shown). Early detection of only IP in the culture supernatant at 1.5 h, ahead of xenocin, appears to be due to constitutive synthesis of the protein in both the xciA mutant and the complemented strains.

Fig 5.

Secretion analysis of xciA and xciA-complemented mutant strains by Western blotting. (A and B) xciA cells were induced with mitomycin C for 2.5 h, and samples were taken at different time points. The cell pellets were separated from the supernatant and precipitated with TCA, and the proteins were analyzed. (C) Protein fractions from xciA+ cells were isolated as described in the text and analyzed. Xn protein, purified xenocin. Cytosolic proteins refers to proteins at 2.5 h of induction of the respective strains. Lane M, low-range, prestained molecular mass markers (in kDa).

Table 2.

Exogenous antibacterial activity and proteins in flagellar preparation from different strains

| Strain | Characteristic of flagella from induced cellsa |

|

|---|---|---|

| Activity | Presence of xenocin/IP | |

| X. nematophila wild type | + | +/+ |

| xciA mutant | − | −/− |

| xciA mutant complemented with xciA-ximB | + | +/+ |

Induced with mitomycin C.

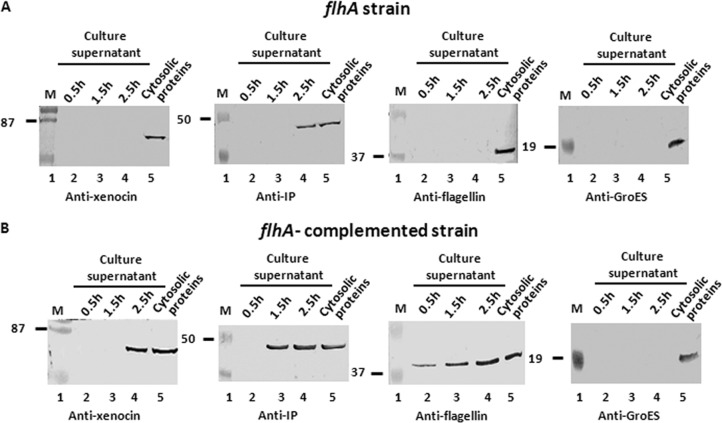

Secretion of xenocin requires FlhA.

To confirm secretion of xenocin-IP complex through the flagellar type III system of X. nematophila, an flhA mutant strain (13) lacking FlhA, a membrane component of the basal body necessary for export of flagellar subunits, was employed. Induction of SOS response in this strain with mitomycin C did not affect cell density, and OD600 and CFU/ml counts in the culture were 0.41 and 3.1 × 107, respectively, similar to those of uninduced culture (0.44 and 3.2 × 107, respectively) after 2.5 h. The cellular protein profile of the mutant showed the presence of both xenocin and IP in the cytoplasmic fraction of the induced cells (Fig. 6A), but no xenocin was detected in the culture supernatant (Fig. 6A). However, IP alone was detected in the culture supernatant of the flhA mutant, suggesting that IP can be exported through a route other than that of the flagellum (Fig. 6A). The major flagellar subunit FliC was produced in the cells normally but was not exported. Unlike the case in E. coli and Salmonella, FliC expression in Xenorhabdus occurs in the absence of flhA, as reported earlier (13), leading to normal levels of FliC synthesis in the flhA strain. Complementation of the flhA mutant with flhA-flhB sequence restored secretion of both xenocin complex and FliC proteins, as expected (Fig. 6B).

Fig 6.

Secretion analysis of flhA and flhA-complemented mutant strains by Western blotting. The samples were taken after induction as described in the text, and proteins in the culture supernatant were separated from the cells. The proteins were precipitated with TCA and analyzed. Cytosolic proteins indicates proteins at 2.5 h of induction of the respective strains. Lane M, low-range, prestained molecular mass markers (in kDa).

Analysis of fliA and fliC mutants for xenocin-IP complex secretion.

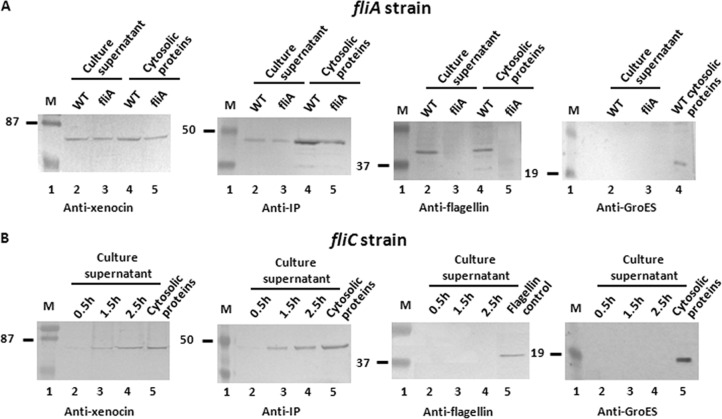

To determine if the xenocin operon was coregulated by FliA (σ28), a transcription factor that regulates class III flagellar genes, an fliA mutant strain of X. nematophila was used. There was no difference between the synthesis and secretion of xenocin complex in the fliA mutant strain and those in the wild-type cells (Fig. 7A), indicating that xenocin complex was transcribed independently and secreted through the flagella, unlike the fliA-regulated class III flagellar component, FliC, which was not produced in this strain. The growth rate of the fliC mutant strain was found to be lower than that of the wild-type strain. Xenocin-immunity protein complex was produced and secreted normally after mitomycin C induction in the absence of flagellar filament as shown in Fig. 7B, indicating that absence of flagellar filament does not affect xenocin export.

Fig 7.

Secretion analysis of fliA and fliC mutants by Western blotting. (A) Wild-type and fliA mutant cultures were induced with mitomycin C and samples taken after 2.5 h. Proteins in the culture supernatant were precipitated and analyzed. WT, wild type. (B) Cytosolic and culture supernatant proteins of the fliC mutant strain were induced with mitomycin C, and samples were taken at different time points and processed as described in the text. Cytosolic proteins were analyzed at 2.5 h; flagellin control indicates purified flagellin. Lane M, low-range, prestained molecular mass markers (in kDa).

Secretion of xenocin variants in X. nematophila.

To determine the minimum essential sequence necessary for secretion through the flagella, DNA sequences encoding xenocin variants were cloned and expressed in the xciA strain of X. nematophila under an IPTG-inducible promoter. The results show that xenocin and IP were produced in the cytosol and exported to the flagella and outside the pPS1 plasmid, containing only the coding sequences of the proteins (Fig. 8B). This implied that the 5′-UTR of the xciA gene is not necessary for targeting the complex to flagellar export. To examine the role of IP in export of the complex, pPS2 containing the xciA sequence without ximB was tested. The wild-type xenocin, when expressed in the absence of IP, was less abundant, suggesting that IP is required for xenocin stability in the cytoplasm. Since the cells harboring the plasmid eventually lysed, flagellar localization could not be examined (Fig. 8C). It is puzzling as to why the constitutively produced IP could not neutralize the toxicity of xenocin. We suspect that the amount of constitutively produced IP is not enough to inactivate xenocin produced from a multicopy plasmid, as it has been observed earlier that more than a 3 times molar excess of IP was required to neutralize xenocin under in vitro conditions (19). Alternatively, the constitutively produced IP, in isolation, may not be readily accessible for complex formation, or it may be chemically/structurally distinct from the inducible IP, not amenable to complex formation. Further work will be needed to answer these interesting questions.

To neutralize xenocin toxicity, we produced enzymatically inactive protein by introducing point mutations in the active site. Growth profiles of the E. coli strains containing xenocin variants D535A and H538A (pPS3 and pPS4) were similar to that of the vector control and showed minimal inhibition in growth compared to the wild-type protein (data not shown). Far-UV circular dichroism spectra of the nontoxic variant indicated that the secondary structure of the latter was not disturbed (data not shown). The plasmids pPS3 and pPS4, when transformed in the xciA mutant, allowed variant xenocin expression in the absence of IP without causing cell lysis when induced with mitomycin C, in contrast to cells containing the wild-type xciA variant. Analysis of expression by Western blotting with anti-xenocin antibody showed the presence of variant xenocin in the cytoplasmic fractions, flagella, and the culture supernatant (Fig. 8C). The level of expression of xenocin alone was lower than that when it was produced as a complex with IP, which could be due to the higher proteolytic susceptibility of the unprotected protein. The individual domains of xenocin, e.g., translocation, translocation-receptor binding, and catalytic domains, were not expressed very stably in the cytosol, hence their export could not be evaluated with a reasonable degree of confidence (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Previously, we have described an antibacterial protein xenocin of X. nematophila that has activity against several bacterial species colonizing the larval gut (19). Bacteriocins need to be transported out of the cell to be functionally active, which occurs by a well-established mechanism of cell lysis orchestrated by a lysis-inducing gene (15). In this study, we demonstrate that the xenocin-IP complex of X. nematophila is released in the extracellular medium through the flagellar type III pathway, which has not been reported before for a bacteriocin.

In bacterial cultures, as the nutrients are depleted due to overcrowding, bacteriocins are induced and released by cell lysis to eliminate the competitor strains. As a consequence, most of the producer population is killed, leaving a small number to withstand the unfavorable conditions (15). In X. nematophila, since antimicrobials are produced in a nutrient-rich insect carcass to control putrefying competitors (40, 41), it may be counterproductive to reduce its own population, considering the requirement of high population density for efficient nematode reproduction (42–44). This might have driven xenocin export by an alternate route without lysing the cell, as it would be beneficial for the evolutionary success of the symbiotic relationship. In a similar case in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, effector toxins were delivered directly in the target cells by a type VI secretion system, thereby minimizing the fitness cost associated with self-targeting, and further, to prevent self-intoxication, the cognate immunity proteins were localized in the periplasm (45). In X. nematophila, we do not know if xenocin is delivered directly to the target cell; however, its direct export outside without cell lysis/self-targeting would surely help in sustaining mutualism, which is vital to its survival in nature.

Our study reveals a unique feature of the immunity protein export in X. nematophila. Synthesis of IP alone, constitutively from the second promoter, P2, and with xenocin from the inducible promoter P1 is in agreement with our earlier observation of two transcripts of 1.2 and 2.9 kb (19). The results of this study show that IP produced from different promoters is exported through different routes. This has never been reported before and raises important questions about, e.g., the specific role of the constitutively produced IP in the periplasm in light of the C-terminal hemolysin domain in the protein (19). The 5′-UTR or the coding sequence of IP appears to contain a signal for targeting it only to the periplasm, as it is never seen alone in the flagella. The nature of the signal sequence/motif and mode of subsequent release of IP in the medium are not known and will be addressed in the future. The presence of IP in the periplasm has been reported for strains producing bacteriocins that act on the murein layer, e.g., colicin M and pesticin, and require an IP to neutralize the incoming bacteriocins (46–49). Since bacteriocins displaying nuclease activity, like xenocin, contain tightly bound IP both in the intracellular and released form (37, 47), presence of free IP in the periplasm is unexpected, and its function entails further investigation. The results suggest that function of the inducible IP is to neutralize lethal activity of xenocin by forming a complex until it is exported out of the producer cell and to protect it from proteolytic degradation. It does not appear to be involved in translocation of the complex, as the nontoxic xenocin variants were exported through the flagellum alone. Under the circumstances, the constitutively produced IP that is present in the cell could not have substituted for inducible IP in xenocin export, because if it were so, the wild-type xenocin (when expressed alone) would be stable and harmless to the cell (Fig. 8C). Based on the observations described above, it can be concluded that xenocin alone has the necessary information for export.

In the absence of a dedicated lysis-inducing system in the proximity of the xenocin operon, we searched for genes implicated in bacteriocin secretion in the genome of X. nematophila (http://www.xenorhabdus.org; RefSeq NC_014228.1) with no significant results. No secretion signal could be identified in the N terminus of xenocin. This is in contrast to the export of the flagellin protein FliC in E. coli and Salmonella, the N terminus of which contains the signal for export through flagella (50–52). Similarly, in Campylobacter jejuni, targeting of FlaA and FlaB was mediated by their amino termini (53), while in Y. enterocolitica the signal for export of YopQ through the type III system was reported to be in the mRNA (54), reflecting the lack of consensus in the recognition motif of substrates. Primary sequence comparison of xenocin to other effector proteins secreted through the flagellar route, e.g., a lipase of X. nematophila (13), phospholipase of Yersinia enterocolitica (26), and flagellar subunits FliC and FliD, did not reveal any common, conserved motif. Thus, it is evident that characteristics of recognition and targeting signals of substrates to the flagellar and type III secretory machinery are yet to be established (27).

It is intriguing that an ∼100-kDa protein complex travels through the narrow 20- to 30-Å-diameter channel of the flagellar filament (55). Flagellar subunits, including the major 55-kDa FliC, are synthesized in the cytoplasm and translocated to the distal end of the growing flagella through a 2- to 3-nm channel (56); it is suggested that the flagellin transits partially unfolded through this channel to its tip, where it refolds before inserting into the growing filament (57, 58). A 41-kDa lipase encoded by xlpA, contiguous to the xciA locus, is also exported through the flagella in X. nematophila (13); however, since it is transcribed divergently by an FliA-dependent promoter, their cotranslocation seems unlikely. Incidentally, Photorhabdus luminescens, another closely related, insect-pathogenic bacterium carried by entomopathogenic nematodes, contains a bacteriocin cluster adjacent to the flagellar operon (59) and could be a substrate for export via flagella. Several pathogenic bacteria are known to export effector proteins and virulence factors through the flagellar type III apparatus (60), but molecular details of translocation have not been elucidated.

Thus, despite the facts that (i) IP is synthesized and exported alone via the periplasm, (ii) the constitutively produced IP, though present, is unable to protect the cell, and (iii) IP apparently is not required for xenocin export through the flagellum, the existence and export of xenocin alone, not in complex with IP, is suicidal for the producer cell. While the combined evidence, e.g., transcription of xciA and ximB as a single transcript and detection of xenocin and IP together in the cytosol by immunoprecipitation and in the flagella only after mitomycin C induction, strongly argue for transport of xenocin-IP together. At this stage, it is not clear if the proteins travel by themselves or if they are assisted by another protein/chaperone, which is common in type III secretory systems (61).

In conclusion, the physiological significance of bacteriocin export through the flagellar route and not by cell lysis could be that it enables X. nematophila to maintain high population density, and it may provide a growth advantage over competing species. Also, secretion through flagella would ensure its effective dissemination in the environment through cellular motility. Another function that may benefit X. nematophila that needs to be explored is whether the flagella can directly deliver xenocin to the target species, as reported for EtpA of enterotoxigenic E. coli (62). Thus, in the absence of a dedicated (nonflagellar) type III secretory system (13), the flagellar pathway could be employed for efficient, targeted killing of competing microbes by X. nematophila.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jitendra Singh for his participation in the early stages of the study.

This work was supported by in-house funding from ICGEB, New Delhi, India.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 18 January 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.01532-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Snyder H, Stock PS, Kim SK, Flores-Lara Y, Forst S. 2007. New insights into the colonization and release processes of Xenorhabdus nematophila and the morphology and ultrastructure of the bacterial receptacle of its nematode host, Steinernema carpocapsae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73: 5338–5346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Banerjee J, Singh J, Joshi MC, Ghosh S, Banerjee N. 2006. The cytotoxic fimbrial structural subunit of Xenorhabdus nematophila is a pore-forming toxin. J. Bacteriol. 188: 7957–7962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brillard J, Riberio C, Boemore N, Brhelin M, Givaudan A. 2001. Two distinct hemolytic activities in Xenorhabdus nematophila are active against immunocompetent insect cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67: 2515–2525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Khandelwal P, Bhatnagar R, Choudhury D, Banerjee N. 2004. Characterization of a cytotoxic pilin subunit of Xenorhabdus nematophila. J. Bacteriol. 314: 943–949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vigneux F, Zumbihl R, Jubelin G, Ribeiro C, Poncet J, Baghdiguian S, Givaudan A, Brehelin M. 2007. The xaxAB genes encoding a new apoptotic toxin from the insect pathogen Xenorhabdus nematophila are present in plant and human pathogens. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 9571–9580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Forst S, Dowds B, Boemore N, Stackebrandt E. 1997. Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus spp.: bugs that kill bugs. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 51: 47–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Joshi MC, Sharma A, Kant S, Birah A, Gupta GP, Khan SR, Bhatnagar R, Banerjee N. 2008. An insecticidal GroEL protein with chitin binding activity from Xenorhabdus nematophila. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 28287–28296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McInerney BV, Gregson RP, Lacey MJ, Akhurst RJ, Lyons GR, Rhodes SH, Smith DR, Engelhardt LM, White AH. 1991. Biologically active metabolites from Xenorhabdus spp., part 1. Dithiolopyrrolone derivatives with antibiotic activity. J. Nat. Prod. 54: 774–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McInerney BV, Taylor WC, Lacey MJ, Akhurst RJ, Gregson RP. 1991. Biologically active metabolites from Xenorhabdus spp., part 2. Benzopyran-1-one derivatives with gastroprotective activity. J. Nat. Prod. 54: 785–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thaler JO, Baghdiguian S, Boemare N. 1995. Purification and characterization of xenorhabdicin, a phage tail-like bacteriocin, from the lysogenic strain F1 of Xenorhabdus nematophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61: 2049–2052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Herbert EE, Goodrich-Blair H. 2007. Friend and foe: the two faces of Xenorhabdus nematophila. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5: 634–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Khandelwal P, Banerjee-Bhatnagar N. 2003. Insecticidal activity associated with the outer membrane vesicles of Xenorhabdus nematophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 4: 2032–2037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Park D, Forst S. 2006. Co-regulation of motility, exoenzyme and antibiotic production by the EnvZ-OmpR-FlhDC-FliA pathway in Xenorhabdus nematophila. Mol. Microbiol. 61: 1397–1412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ozeki H, Stocker BA, DeMargerie H. 1959. Production of colicin by single bacteria. Nature 184: 337–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cascales E, Buchanan SK, Duché D, Kleanthous C, Lloubès R, Postle K, Riley M, Slatin S, Cavard D. 2007. Colicin biology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 71: 158–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Housden NG, Loftus SR, Moore GR, James R, Kleanthous C. 2005. Cell entry mechanism of enzymatic bacterial colicins: porin recruitment and the thermodynamics of receptor binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102: 13849–13854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zakharov SD, Zhalnina MV, Sharma O, Cramer WA. 2006. The colicin E3 outer membrane translocon: immunity protein release allows interaction of the cytotoxic domain with OmpF porin. Biochemistry 45: 10199–10207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Masaki H, Ohta T. 1985. Colicin E3 and its immunity genes. J. Mol. Biol. 182: 217–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Singh J, Banerjee N. 2008. Transcriptional analysis and functional characterization of a gene pair encoding iron-regulated xenocin and immunity proteins of Xenorhabdus nematophila. J. Bacteriol. 190: 3877–3885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Havarstein LS, Diep DB, Nes IF. 1995. A family of bacteriocin ABC transporters carry out proteolytic processing of their substrates concomitant with export. Mol. Microbiol. 16: 229–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Economou A, Christie PJ, Fernandez RC, Palmer T, Plano GV, Pugsley AP. 2006. Secretion by numbers: protein traffic in prokaryotes. Mol. Microbiol. 62: 308–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Beveridge TJ. 1999. Structures of gram-negative cell walls and their derived membrane vesicles. J. Bacteriol. 181: 4725–4733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sauer FG, Futterer K, Pinkner JS, Dodson KW, Hultgren SJ, Waksman G. 1999. Structural basis of chaperone function and pilus biogenesis. Science 285: 1058–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Konkel ME, Klena JD, Rivera-Amill V, Monteville MR, Biswas D, Raphael B, Mickelson J. 2004. Secretion of virulence proteins from Campylobacter jejuni is dependent on a functional flagellar export apparatus. J. Bacteriol. 186: 3296–3303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Larson CL, Christensen JE, Pacheco SA, Minnich SA, Konkel ME. 2008. Campylobacter jejuni secretes proteins via the flagellar type III secretion system that contributes to host cell invasion and gastroenteritis, p 315–332 In Nachamkin I, Szymanski CM, Blaser MJ. (ed), Campylobacter, 3rd ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 26. Young GM, Schmiel DH, Miller VL. 1999. A new pathway for the secretion of virulence factors by bacteria: the flagellar export apparatus functions as a protein secretion system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96: 6456–6461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Galan JE, Wolf-Watz H. 2006. Protein delivery into eukaryotic cells by type III secretion machines. Nature 444: 567–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Macnab RM. 2003. How bacteria assemble flagella. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57: 77–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Majander K, Anton L, Antikainen J, Lång H, Brummer M, Korhonen TK, Westerlund-Wikström B. 2005. Extracellular secretion of polypeptides using a modified Escherichia coli flagellar secretion apparatus. Nat. Biotechnol. 23: 475–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chaston JM, Suen G, Tucker SL, Andersen AW, Bhasin A, Bode E, Bode HB, Brachmann AO, Cowles CE, Cowles KN, Darby C, de Léon L, Drace K, Du Z, Givaudan A, Herbert Tran EE, Jewell KA, Knack JJ, Krasomil-Osterfeld KC, Kukor R, Lanois A, Latreille P, Leimgruber NK, Lipke CM, Liu R, Lu X, Martens EC, Marri PR, Médigue C, Menard ML, Miller NM, Morales-Soto N, Norton S, Ogier JC, Orchard SS, Park D, Park Y, Qurollo BA, Sugar DR, Richards GR, Rouy Z, Slominski B, Slominski K, Snyder H, Tjaden BC, van der Hoeven R, Welch RD, Wheeler C, Xiang B, Barbazuk B, Gaudriault S, Goodner B, Slater SC, Forst S, Goldman BS, Goodrich-Blair H. 2011. The entomopathogenic bacterial endosymbionts Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus: convergent lifestyles from divergent genomes. PLoS One 6: e27909 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Quandt J, Hynes MF. 1993. Versatile suicide vectors, which allow direct selection for gene replacement in Gram negative bacteria. Gene 127:15–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ferdinand W. 1964. The isolation and specific activity of rabbit muscle glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase. Biochem. J. 92: 578–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Alberti L, Harshey RM. 1990. Differentiation of Serratia marcescens 274 into swimmer and swarmer cells. J. Bacteriol. 172: 4322–4328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Banai M, Gonda MA, Ranhand JM, LeBlanc DJ. 1985. Streptococcus faecalis R plasmid pJH1 contains a pAM alpha 1 delta 1-like replicon. J. Bacteriol. 164: 626–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chandra H, Khandelwal P, Khattri A, Banerjee N. 2008. Type 1 fimbriae of insecticidal bacterium Xenorhabdus nematophila is necessary for growth and colonization of its symbiotic host nematode Steinernema carpocapsiae. Environ. Microbiol. 10: 1285–1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Xu J, Lohrke S, Hurlbert IM, Hurlbert RE. 1989. Transformation of Xenorhabdus nematophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55: 806–812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Soelaiman S, Jakes K, Wu N, Li C, Shoham M. 2001. Crystal structure of colicin E3: implications for cell entry and ribosome inactivation. Mol. Cell 8: 1053–1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Berks BC, Sargent F, Palmer T. 2000. The Tat protein export pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 35: 260–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dirix G, Monsieurs P, Marchal K, Vanderleyden J, Michiels J. 2004. Screening genomes of Gram-positive bacteria for double-glycine-motif-containing peptides. Microbiology 150: 1121–1126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Thaler JO, Boyer-Giglio MH, Boemare N. 1997. New antimicrobial barriers produced by Xenorhabdus spp and Photorhabdus spp to secure the monoxenic development of entomopathogenic nematodes. Symbiosis 22: 205–215 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Forst S, Nealson K. 1996. Molecular biology of the symbiotic-pathogenic bacteria Xenorhabdus spp. and Photorhabdus spp. Microbiol. Rev. 60: 21–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sicard M, Brugirard-Ricaud K, Pages S, Lanois A, Boemare NE, Brehelin M, Givaudan A. 2004. Stages of infection during the tripartite interaction between Xenorhabdus nematophila, its nematode vector, and insect hosts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70: 6473–6480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sicard M, Le Brun N, Pages S, Godelle B, Boemare N, Moulia C. 2003. Effect of native Xenorhabdus on the fitness of their Steinernema hosts: contrasting types of interaction. Parasitol. Res. 91: 520–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mitani DK, Kaya HK, Goodrich-Blair H. 2004. Comparative study of the entomopathogenic nematode, Steinernema carpocapsae, reared on mutant and wild-type Xenorhabdus nematophila. Biol. Control 29: 382–391 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Russell AB, Hood RD, Bui NK, LeRoux M, Vollmer W, Mougous JD. 2011. Type VI secretion delivers bacteriolytic effectors to target cells. Nature 475: 343–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Olschläger T, Turba A, Braun V. 1991. Binding of the immunity protein inactivates colicin M. Mol. Microbiol. 5: 1105–1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. James R, Lazdunski C, Pattus F. 1992. Bacteriocins, microcins and lantibiotics. NATO ASI series H. Cell biology, vol 65 Springer Verlag, Berlin, Germany: [Google Scholar]

- 48. Groß P, Braun V. 1996. Colicin M is inactivated during import by its immunity protein. Mol. Gen. Genet. 251: 388–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pilsl H, Killmann H, Hantke K, Braun V. 1996. Periplasmic location of the pesticin immunity protein suggests inactivation of pesticin in the periplasm. J. Bacteriol. 178: 2431–2435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dobó J, Varga J, Sajó R, Végh BM, Gál P, Závodszky P, Vonderviszt F. 2010. Application of a short, disordered N-terminal flagellin segment, a fully functional flagellar type III export signal, to expression of secreted proteins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76: 891–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hirano T, Minamino T, Namba K, Macnab RM. 2003. Substrate specificity classes and the recognition signal for Salmonella type III flagellar export. J. Bacteriol. 185: 2485–2492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kuwajima G, Kawagishi I, Homma M, Asaka J, Kondo E, Macnab RM. 1989. Export of an N-terminal fragment of Escherichia coli flagellin by a flagellum-specific pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86: 4953–4957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Neal-McKinney JM, Christensen JE, Konkel ME. 2010. Amino-terminal residues dictate the export efficiency of the Campylobacter jejuni filament proteins via the flagellum. Mol. Microbiol. 76: 918–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Anderson DM, Schneewind O. 1997. A mRNA signal for the type III secretion of Yop proteins by Yersinia enterocolitica. Science 278: 1140–1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yonekura K, Maki-Yonekura S, Namba K. 2003. Complete atomic model of the bacterial flagellar filament by electron cryomicroscopy. Nature 424: 643–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Morgan DG, Owen C, Melanson LA, DeRosier DJ. 1995. Structure of bacterial flagellar filaments at 11 Å resolution: packing of the α-helices. J. Mol. Biol. 249: 88–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Samatey FA, Imada K, Nagashima S, Vonderviszt F, Kumasaka T, Yamamoto M, Namba K. 2001. Structure of the bacterial flagellar protofilament and implications for a switch for supercoiling. Nature 410: 331–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yonekura K, Maki S, Morgan DG, DeRosier DJ, Vonderviszt F, Imada K, Namba K. 2000. Bacterial flagellar cap as the rotary promoter of flagellin self-assembly. Science 290: 2148–2152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sharma S, Waterfield N, Bowen D, Rocheleau T, Holland L, James R, French-Constant R. 2002. The lumicins: novel bacteriocins from Photorhabdus luminescens with similarity to the uropathogenic-specific protein (USP) from uropathogenic Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 214: 241–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Moraes TF, Spreter T, Strynadka NC. 2008. Piecing together the type III injectisome of bacterial pathogens. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 18: 258–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Page AL, Parsot C. 2002. Chaperones of the type III secretion pathway: jacks of all trades. Mol. Microbiol. 46: 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Roy K, Hilliard GM, Hamilton DJ, Luo J, Ostmann MM, Fleckenstein JM. 2009. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli EtpA mediates adhesion between flagella and host cells. Nature 457: 594–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.