Abstract

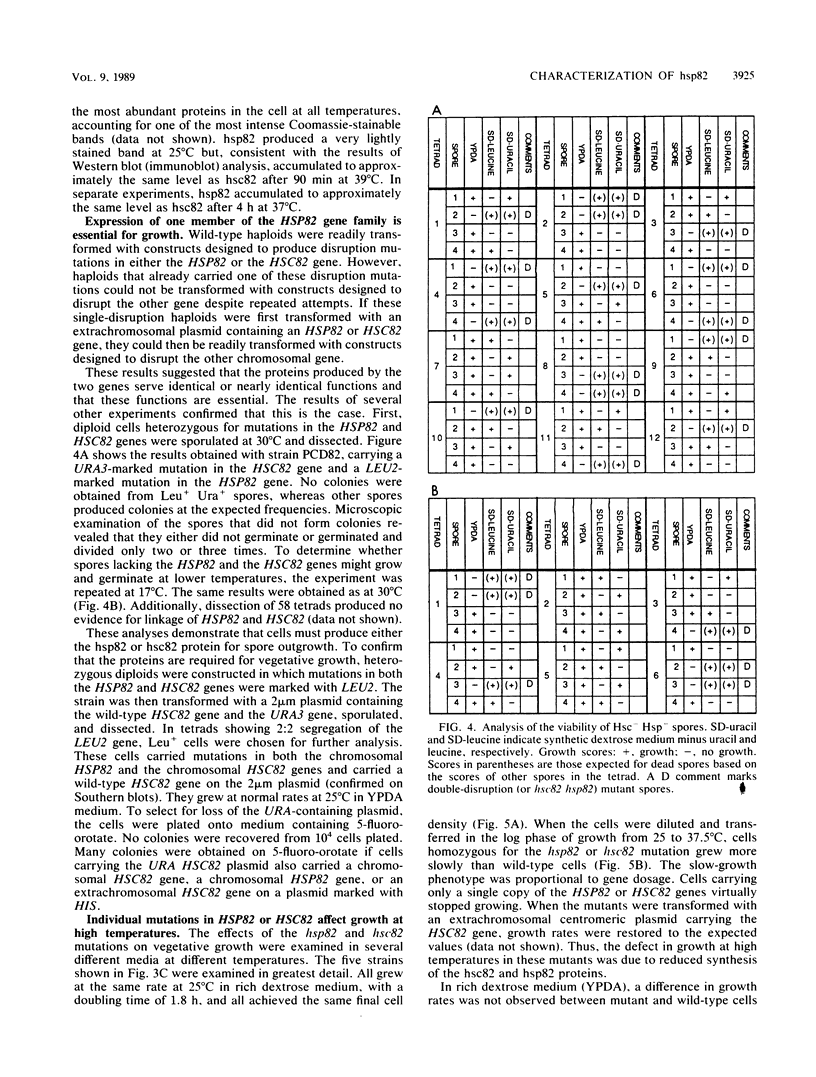

hsp82 is one of the most highly conserved and abundantly synthesized heat shock proteins of eucaryotic cells. The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains two closely related genes in the HSP82 gene family. HSC82 was expressed constitutively at a very high level and was moderately induced by high temperatures. HSP82 was expressed constitutively at a much lower level and was more strongly induced by heat. Site-directed disruption mutations were produced in both genes. Cells homozygous for both mutations did not grow at any temperature. Cells carrying other combinations of the HSP82 and HSC82 mutations grew well at 25 degrees C, but their ability to grow at higher temperatures varied with gene copy number. Thus, HSP82 and HSC82 constitute an essential gene family in yeast cells. Although the two proteins had different patterns of expression, they appeared to have equivalent functions; growth at higher temperatures required higher concentrations of either protein. Biochemical analysis of hsp82 from vertebrate cells suggests that the protein binds to a variety of other cellular proteins, keeping them inactive until they have reached their proper intracellular location or have received the proper activation signal. We speculate that the reason cells require higher concentrations of hsp82 or hsc82 for growth at higher temperatures is to maintain proper levels of complex formation with these other proteins.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Amin J., Ananthan J., Voellmy R. Key features of heat shock regulatory elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1988 Sep;8(9):3761–3769. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.9.3761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell J. C., Craig E. A. Ancient heat shock gene is dispensable. J Bacteriol. 1988 Jul;170(7):2977–2983. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.7.2977-2983.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackman R. K., Meselson M. Interspecific nucleotide sequence comparisons used to identify regulatory and structural features of the Drosophila hsp82 gene. J Mol Biol. 1986 Apr 20;188(4):499–515. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(86)80001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkovich K. A., Weiss R. L. Purification and characterization of arginase from Neurospora crassa. J Biol Chem. 1987 May 25;262(15):7081–7086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broach J. R., Strathern J. N., Hicks J. B. Transformation in yeast: development of a hybrid cloning vector and isolation of the CAN1 gene. Gene. 1979 Dec;8(1):121–133. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(79)90012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugge J. S., Erikson E., Erikson R. L. The specific interaction of the Rous sarcoma virus transforming protein, pp60src, with two cellular proteins. Cell. 1981 Aug;25(2):363–372. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chothia C., Janin J. Principles of protein-protein recognition. Nature. 1975 Aug 28;256(5520):705–708. doi: 10.1038/256705a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtneidge S. A., Bishop J. M. Transit of pp60v-src to the plasma membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Dec;79(23):7117–7121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.23.7117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig E. A., Jacobsen K. Mutations of the heat inducible 70 kilodalton genes of yeast confer temperature sensitive growth. Cell. 1984 Oct;38(3):841–849. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig E. A., Kramer J., Kosic-Smithers J. SSC1, a member of the 70-kDa heat shock protein multigene family of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is essential for growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Jun;84(12):4156–4160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.12.4156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis R. W., Thomas M., Cameron J., St John T. P., Scherer S., Padgett R. A. Rapid DNA isolations for enzymatic and hybridization analysis. Methods Enzymol. 1980;65(1):404–411. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)65051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devereux J., Haeberli P., Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984 Jan 11;12(1 Pt 1):387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty J. J., Puri R. K., Toft D. O. Polypeptide components of two 8 S forms of chicken oviduct progesterone receptor. J Biol Chem. 1984 Jun 25;259(12):8004–8009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragon E. A., Sias S. R., Kato E. A., Gabe J. D. The genome of Trypanosoma cruzi contains a constitutively expressed, tandemly arranged multicopy gene homologous to a major heat shock protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1987 Mar;7(3):1271–1275. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.3.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly F. W., Finkelstein D. B. Complete sequence of the heat shock-inducible HSP90 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1984 May 10;259(9):5745–5751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley D., Ozkaynak E., Varshavsky A. The yeast polyubiquitin gene is essential for resistance to high temperatures, starvation, and other stresses. Cell. 1987 Mar 27;48(6):1035–1046. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90711-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H., Fukuda Y., Murata K., Kimura A. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J Bacteriol. 1983 Jan;153(1):163–168. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.163-168.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joab I., Radanyi C., Renoir M., Buchou T., Catelli M. G., Binart N., Mester J., Baulieu E. E. Common non-hormone binding component in non-transformed chick oviduct receptors of four steroid hormones. 1984 Apr 26-May 2Nature. 308(5962):850–853. doi: 10.1038/308850a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy I. M., Burdon R. H., Leader D. P. Heat shock causes diverse changes in the phosphorylation of the ribosomal proteins of mammalian cells. FEBS Lett. 1984 Apr 24;169(2):267–273. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)80331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyasu S., Nishida E., Kadowaki T., Matsuzaki F., Iida K., Harada F., Kasuga M., Sakai H., Yahara I. Two mammalian heat shock proteins, HSP90 and HSP100, are actin-binding proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Nov;83(21):8054–8058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S., Lindquist S. Changing patterns of gene expression during sporulation in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Dec;81(23):7323–7327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.23.7323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist S., Craig E. A. The heat-shock proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 1988;22:631–677. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.22.120188.003215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsich L. A., Cutt J. R., Brugge J. S. Association of the transforming proteins of Rous, Fujinami, and Y73 avian sarcoma viruses with the same two cellular proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1982 Jul;2(7):875–880. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.7.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzarella R. A., Green M. ERp99, an abundant, conserved glycoprotein of the endoplasmic reticulum, is homologous to the 90-kDa heat shock protein (hsp90) and the 94-kDa glucose regulated protein (GRP94). J Biol Chem. 1987 Jun 25;262(18):8875–8883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasmyth K. A., Tatchell K. The structure of transposable yeast mating type loci. Cell. 1980 Mar;19(3):753–764. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(80)80051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidhardt F. C., VanBogelen R. A., Lau E. T. Molecular cloning and expression of a gene that controls the high-temperature regulon of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1983 Feb;153(2):597–603. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.2.597-603.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida E., Koyasu S., Sakai H., Yahara I. Calmodulin-regulated binding of the 90-kDa heat shock protein to actin filaments. J Biol Chem. 1986 Dec 5;261(34):16033–16036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham H. R. A regulatory upstream promoter element in the Drosophila hsp 70 heat-shock gene. Cell. 1982 Sep;30(2):517–528. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petko L., Lindquist S. Hsp26 is not required for growth at high temperatures, nor for thermotolerance, spore development, or germination. Cell. 1986 Jun 20;45(6):885–894. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90563-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebbe N. F., Ware J., Bertina R. M., Modrich P., Stafford D. W. Nucleotide sequence of a cDNA for a member of the human 90-kDa heat-shock protein family. Gene. 1987;53(2-3):235–245. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redeuilh G., Moncharmont B., Secco C., Baulieu E. E. Subunit composition of the molybdate-stabilized "8-9 S" nontransformed estradiol receptor purified from calf uterus. J Biol Chem. 1987 May 25;262(15):6969–6975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renoir J. M., Buchou T., Baulieu E. E. Involvement of a non-hormone-binding 90-kilodalton protein in the nontransformed 8S form of the rabbit uterus progesterone receptor. Biochemistry. 1986 Oct 21;25(21):6405–6413. doi: 10.1021/bi00369a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose D. W., Wettenhall R. E., Kudlicki W., Kramer G., Hardesty B. The 90-kilodalton peptide of the heme-regulated eIF-2 alpha kinase has sequence similarity with the 90-kilodalton heat shock protein. Biochemistry. 1987 Oct 20;26(21):6583–6587. doi: 10.1021/bi00395a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein R. J. One-step gene disruption in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:202–211. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez E. R., Housley P. R., Pratt W. B. The molybdate-stabilized glucocorticoid binding complex of L-cells contains a 98-100 kdalton steroid binding phosphoprotein and a 90 kdalton nonsteroid-binding phosphoprotein that is part of the murine heat-shock complex. J Steroid Biochem. 1986 Jan;24(1):9–18. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(86)90025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez E. R., Meshinchi S., Tienrungroj W., Schlesinger M. J., Toft D. O., Pratt W. B. Relationship of the 90-kDa murine heat shock protein to the untransformed and transformed states of the L cell glucocorticoid receptor. J Biol Chem. 1987 May 25;262(15):6986–6991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez E. R., Redmond T., Scherrer L. C., Bresnick E. H., Welsh M. J., Pratt W. B. Evidence that the 90-kilodalton heat shock protein is associated with tubulin-containing complexes in L cell cytosol and in intact PtK cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1988 Aug;2(8):756–760. doi: 10.1210/mend-2-8-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater M. R., Craig E. A. Transcriptional regulation of an hsp70 heat shock gene in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1987 May;7(5):1906–1916. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.5.1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanBogelen R. A., Acton M. A., Neidhardt F. C. Induction of the heat shock regulon does not produce thermotolerance in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 1987 Aug;1(6):525–531. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.6.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widelitz R. B., Magun B. E., Gerner E. W. Effects of cycloheximide on thermotolerance expression, heat shock protein synthesis, and heat shock protein mRNA accumulation in rat fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 Apr;6(4):1088–1094. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.4.1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H., Lis J. T. Germline transformation used to define key features of heat-shock response elements. Science. 1988 Mar 4;239(4844):1139–1142. doi: 10.1126/science.3125608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziemiecki A. Characterization of the monomeric and complex-associated forms of the gag-onc fusion proteins of three isolates of feline sarcoma virus: phosphorylation, kinase activity, acylation, and kinetics of complex formation. Virology. 1986 Jun;151(2):265–273. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]