Abstract

Emotion research is guided both by the view that emotions are points in a dimensional space, such as valence or approach–withdrawal, and by the view that emotions are discrete categories. We determined whether effective connectivity of amygdala with medial orbitofrontal cortex (MOFC) and lateral orbitofrontal cortex (LOFC) differentiates the perception of emotion faces in a manner consistent with the dimensional and/or categorical view. Greater effective connectivity from left MOFC to amygdala differentiated positive and neutral expressions from negatively valenced angry, disgust, and fear expressions. Greater effective connectivity from right LOFC to amygdala differentiated emotion expressions conducive to perceiver approach (happy, neutral, and fear) from angry expressions that elicit perceiver withdrawal. Finally, consistent with the categorical view, there were unique patterns of connectivity in response to fear, anger, and disgust, although not in response to happy expressions, which did not differ from neutral ones.

Keywords: Amygdala, OFC, Connectivity, Face, Emotion perception

INTRODUCTION

There is a long and ongoing controversy concerning how to best conceptualize emotions. Some take a categorical approach in which emotions are viewed as discrete categories represented by distinct patterns of behavior and physiological responses (Ekman, Dalgleish, & Power, 1999a, 1999b). Others take a dimensional approach in which emotions are viewed as points in a dimensional space defined by valence, arousal, and/or approach–withdrawal (Barrett, 2006; Russell & Barrett, 1999). This debate has implications not only for the nature of emotional experience, but also for the perception of emotion expressions. Efforts to resolve it by identifying unique physiological markers of different emotions have met with little success. It is clear that emotions do differ in the extent to which they activate approach and withdrawal tendencies and arousal (Davidson, Ekman, Saron, Senulis, & Friesen, 1990; Fontaine, Scherer, Roesch, & Ellsworth, 2007), but there is also some weak evidence for unique psycho-physiological signatures (Cacioppo, Berntson, Larsen, Poehlmann, & Ito, 2000; Lerner, Dahl, Hariri, & Taylor, 2007; Rainville, Bechara, Naqvi, & Damasio, 2006; Zajonc & McIntosh, 1992). A potential resolution to this controversy could be provided by an examination of brain activation elicited by different emotions to determine whether there is a unique pattern for each of the putative emotion categories, whether the neural response maps onto a dimensional space, or whether both are true (Barrett & Wager, 2006). The present study takes a step toward that goal, examining effective connectivity in amygdala and medial and lateral orbitofrontal cortex (MOFC, LOFC) when viewing faces with angry, disgust, fear, happy, and neutral expressions.

Although many studies have examined neural activation to facial expressions, our understanding of the mechanisms by which various expressions are differentiated in the brain remains limited. This is not surprising given the complexity of the neural mechanisms. Face perception in general is served by a network of several brain regions (Haxby, Hoffman, & Gobbini, 2002; Ishai, Schmidt, & Boesiger, 2005), and emotion perception in particular involves a complex network of subcortical and cortical structures (Adolphs, 2002). Indeed, a meta-analysis has implicated more than a dozen brain regions that are reliably activated in response to multiple emotions, including facial expressions (Phan, Wager, Taylor, & Liberzon, 2004).

The fact that multiple emotions activate the same brain regions may be construed as consistent with the dimensional approach, which argues that emotions are differentiated by valence or by the level of arousal or withdrawal they elicit. Further evidence to support this view is provided by some evidence for greater responsiveness of the right than left hemisphere to negative emotions and the reverse for positive ones. This effect may be also conceptualized as a right hemisphere advantage for high arousal emotions (for a review, see Adolphs, 2002). Also consistent with the dimensional approach is evidence that emotions associated with approach behavior (anger, happiness) elicit stronger right than left hemisphere activation than fear, which is associated with withdrawal (Davidson, 2004).

It should be noted that most of the above-mentioned support for the dimensional approach pertains to the experience of emotion, rather than the perception of emotion expressions. A meta-analysis of positron emission tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies by Murphy, Nimmo-Smith, and Lawrence (2003) found no significant hemisphere asymmetry when viewing either positive or negative emotion expressions or expressions associated with approach or withdrawal. However, they defined approach and withdrawal in terms of the likely behavior of the person expressing the emotion, which may not make sense when assessing the neural activation of the perceiver. Although experiencing anger may be associated with approach responses, perceiving anger speeds hand movements that mimic withdrawal responses. Similarly, whereas experiencing fear is likely to be associated with withdrawal responses, perceiving fear speeds hand movements that mimic approach responses (Marsh, Ambady, & Kleck, 2005; Zhang & Zebrowitz, 2007). One interpretation for the latter finding is that although fear expressions are unpleasant, they invite help and assistance. In the present study, we consider the neural response to approach vs. withdrawal emotion expressions defined in terms of both the expressor and the perceiver as well as the neural response to emotion expressions with positive vs. negative valence.

Whereas Murphy et al. (2003) failed to find evidence for hemispheric asymmetries in response to the valence of emotion expressions or the expressor’s approach/withdrawal tendencies, they did find unique patterns of activation to different emotion categories. Specifically, these authors found a different spatial distribution of neural activation in response to facial expressions of fear, disgust, and anger, with amygdala activation most reliable for fear, insula activation for disgust, and lateral OFC activation for anger. In addition, the activations elicited by happiness and sadness differed from each of these emotions but not from one another. Other evidence consistent with the categorical view has been provided by research documenting dissociations of deficits in emotion recognition, particularly fear and disgust (Calder et al., 2003; Lawrence, Murphy, Calder, & Yiend, 2004).

Based on the foregoing research, it is possible that hemispheric asymmetries in neural response do not map onto the dimensions of expression valence or approach/withdraw tendencies when one is perceiving facial expressions of emotion in the way that they do when one is experiencing emotion. However, it may also be that focusing exclusively on neural activation misses dimensional representations of emotion expressions. As already noted, emotion perception involves a complex network of subcortical and cortical structures, and the effective connectivity between brain regions may be as important as their level of activation when one is predicting the kind of face that perceivers are viewing (Fairhall & Ishai, 2007; Knight, 2007; Zebrowitz, Luevano, Bronstad, & Aharon, 2007). Tests of effective connectivity in response to different facial expressions of emotion are limited. Some research has provided indirect evidence that amygdala modulates the processing of facial expression in reward regions (Morris et al., 1998; Vuilleu-mier, Armony, Driver, & Dolan, 2003). Other research directly testing effective connectivity has focused only on fear expressions (de Marco, de Bonis, Vrignaud, Henry-Feugeas, & Peretti, 2006; Williams et al., 2006). Still other research has included multiple emotions, but performed contrasts that combine them, leaving unanswered the question of whether connectivity differs across emotions (Fairhall & Ishai, 2007; Iidaka et al., 2001; Stein et al., 2007).

The present research examined effective connectivity of amygdala with MOFC and LOFC to determine whether it differentiates the perception of faces with neutral, fear, angry, disgust, and happy expressions. We focus on these brain regions for several reasons. First, amygdala is a key structure for the experience and perception of emotion (Phelps, 2006). Second, OFC is considered pivotal in evaluating the emotional valence of stimuli for the purpose of guiding goal-related behavioral responses, such as approach and withdrawal (Barbas, Schoenbaum, Gottfried, Murray, & Ramus, 2007; Ochsner & Gross, 2005; Rolls, 1995). In addition, amygdala and OFC are strongly interconnected anatomically (Ghashghaei & Barbas, 2002; Wallis, 2007), and there is stronger effective connectivity between these regions when viewing fear and anger faces as contrasted with geometric forms (Stein et al., 2007). There also is evidence that OFC may modulate amygdala reactivity in the regulation of negative emotions (Banks, Eddy, Angstadt, Nathan, & Phan, 2007). Finally, different portions of OFC have been found to respond differentially to appetitive (rewards) or aversive (punishments) outcomes (O’Doherty, Kringelbach, Rolls, Hornak, & Andrews, 2001; O’Doherty et al., 2003), and emotional faces can instantiate these different types of outcomes. We focused on reciprocal paths between amygdala and MOFC and between amygdala and LOFC in the left and right hemispheres. We did not include paths between LOFC and MOFC because the connections between them are weak (Carmichael & Price, 1996).

If the neural response to emotion expressions is differentiated according to a valence dimension, then there should be commonalities in effective connectivity when one is viewing the negative expressions of fear, anger, and disgust, which should differ from connectivity when one is viewing more positive happy and neutral expressions. If the neural response is differentiated according to an approach–withdrawal dimension that captures the likely responses of the person expressing the emotion, then there should be commonalities in effective connectivity when one is viewing happy and angry expressions, which are associated with expressor approach, and this connectivity should differ from that shown to fear expressions, which are associated with expressor withdrawal. Alternatively, if the neural response to emotion expressions is differentiated according to an approach–withdrawal dimension that captures responses of the person perceiving the emotion, then there should be commonalities in effective connectivity when viewing happy, neutral, and fear expressions, all of which may elicit perceiver approach, and these should differ from angry expressions, which elicit perceiver withdrawal. Finally, there may be unique effective connectivity shown for each emotion, consistent with the categorical account.

METHOD

Participants

fMRI data were provided by 17 healthy, Caucasian participants (9 females), 21–36 years old (M=26.5). All were right-handed (self-reported), and were paid $80.

Stimuli

Grayscale faces (120) with direct gaze formed 12 equal a priori categories: babies, babyfaced, maturefaced, low attractive, high attractive, disfigured, elderly, female, angry, disgust, fear and happy. Except for the female and baby categories, all were adult males. Except for the emotion faces, all had neutral expressions with closed mouths. Faces were normalized: Mean luminance and contrast were equated; the eyes were at the same height; and the middle of the eyes was at the same location. A small fixation cross was super-imposed on the midpoint of the eyes. All the neutral expression faces had been used in a previous study (Zebrowitz, Fellous, Mignault, & Andreoletti, 2003).

The current study focused on five face categories: angry, disgust, fear, happy, and maturefaced, which served as the neutral face category. Each category included faces of 10 Caucasian men. The emotion faces were taken from standard posed photographs (Ekman & Friesen, 1976). The neutral faces were drawn from a longitudinal study of representative samples of individuals born in Berkeley, CA or attending school in Oakland, CA (Zebrowitz, Olson, & Hoffman, 1993).

Procedure

MRI scanning was conducted at MGH/MIT/HST/Martinos Center. Stimuli were presented by E-Prime using a back-projected device and a set of mirrors mounted on the head coil. Participants passively viewed the faces with instructions to maintain central fixation throughout the task and to press a button whenever they saw a big fixation cross. The latter task was included to maintain their alertness. The experimental protocol conformed to all regulatory standards, and it was approved by the IRBs at the MGH/MIT/HST/Martinos Center and at Brandeis University. All participants signed an informed consent form.

Experimental paradigm

The faces were presented in a six-run block design. Within each run, a block of faces was alternated with a block of fixation points, lasting 20 s. Each block of faces included 10 faces from the same category. The faces and the fixation crosses were presented for 200 ms each, followed by a blank gray screen for 1800 ms. All 120 faces were shown within each run, with the sequence of face category presentations counterbalanced across runs (Dale, 1999).

Imaging protocol

We used a head coil Siemens 3 T scanner. Scanning included T2*-weighted functional images followed by (1) T1-weighted structural images for coregistration purposes, and (2) two T1, 128 sagittal images (1×1×1.33 mm) for anatomy. Functional images included 25 contiguous axial oblique (AC–PC line) 6 mm slices (TR=2000 ms; TE=30 ms; FOV=40×20 cm; 30 slices; voxel resolution=3.1×3.1×4.8 mm).

fMRI image analysis

FMRI data processing was carried out using FEAT (FMRI Expert Analysis Tool) version 5.43, part of FSL (FMRIB’s Software Library, www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl). The following pre-statistics processing was applied: motion correction using MCFLIRT (Jenkinson, Bannister, Brady, & Smith, 2002); non-brain removal using BET (Smith, 2002); spatial smoothing using a Gaussian kernel of FWHM 5 mm; grand-mean intensity normalization of the entire 4D dataset by a single multiplicative factor; high-pass filtering (Gaussian least-square straight line fitting, with sigma=50.0s). Time-series statistical analysis was carried out using FILM with local autocorrelation correction (Woolrich, Ripley, Brady, & Smith, 2001) We set up five contrasts: disgust vs. baseline, angry vs. baseline, happy vs. baseline, fear vs. baseline, and neutral vs. baseline. First, statistical mapping was performed at the individual level using GLM within FEAT. After analysis at the individual level, the results were normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI)-152 template using FSL’s FLIRT. Mixed-effects group analyses were then performed for each contrast using FSL’s FLAME (FMRIB’s Local Analysis of Mixed Effects). Group-level statistical maps were thresholded using clusters determined by Z>2.3, and a (corrected) cluster significance threshold of p=.1.

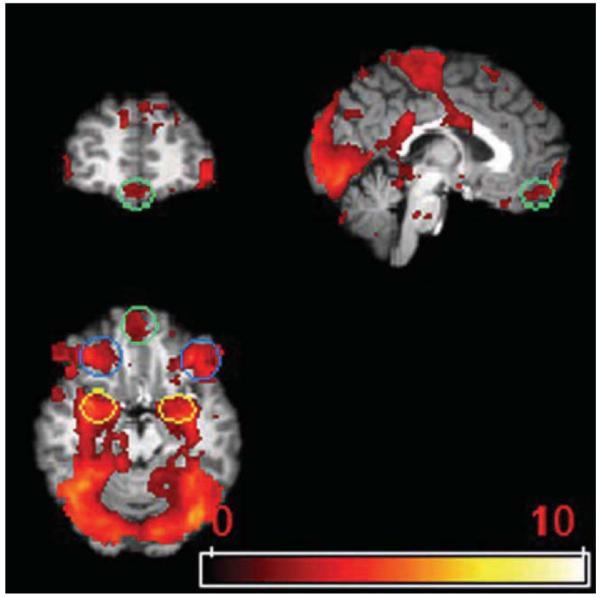

fMRI data extraction from regions of interest (ROIs)

ROI analyses focused on amygdala, MOFC and LOFC. Amygdala was defined based on an anatomical amygdala (http://hendrix.ei.dtu.dk/services/jerne/ninf/voi/index-alphabetic.html). LOFC was defined as the orbital part of the middle and the inferior frontal gyrus. MOFC was defined as the gyrus rectus. With a lenient threshold Z>1.67 (p<.05, no corrections), we detected activations to each of the four emotional face categories as well as the neutral face category in amygdala, MOFC and LOFC. We defined functional ROIs of amygdala, MOFC and LOFC by intersecting the mixed-effect group activated map with anatomical ROIs defined above (Figure 1). Average BOLD signal changes corresponding to the five contrasts of each emotion expression with baseline were then extracted from amygdala, MOFC and LOFC. The average BOLD signal changes were averaged across both runs and subjects by using PEATE software (www.jonas kaplan.com/peate/peate-tk.html).

Figure 1.

Regions of interest. Yellow circle, amygdala; green circle, MOFC; blue circle, LOFC.

Structural equation modeling (SEM)

In the application of SEM to neural activation, connections between brain areas are based on known neuroanatomy, and the covariances of activity among regions are used to calculate path coefficients that represent the directional influence of each path (McIntosh & Gonzalez-Lima, 1994). In the present study, we used SEM to construct path models that capture directional relationships among BOLD signal changes in the three ROIs for each emotion expression, and we determined whether the directional paths differed between emotions. To execute SEM, a null model is compared with an alternative model (LISREL software version 8.80, Student Edition, Joreskog & Sorbom, 2006). In the null model, there are no differences between the path coefficients for the emotion expressions being compared. Rather, all path coefficients are constrained to be equal. In the alternative model, the constraints are removed. Since the null model is nested in the alternative model, it is possible to use the difference between the χ2 of the two models and the difference between degrees of freedom of the two models to test whether the models are significantly different (Bollen, 1989a,1989b)

Entering average signal changes extracted from the three functional ROIs (amygdala, MOFC and LOFC) in each hemisphere as the variables, we compared null and alternative models for 10 pairs of emotion expressions: neutral vs. happy, neutral vs. angry, neutral vs. fear, neutral vs. disgust, happy vs. angry, happy vs. fear, happy vs. disgust, angry vs. fear, angry vs. disgust, fear vs. disgust. The models were estimated within each hemisphere across the entire group of subjects, and we rejected the null model if the χ2 p-value was less than .05. When the null and alternative models differed significantly, we next determined where the differences lay by testing which path in the alternative model contributed to this overall difference.

RESULTS

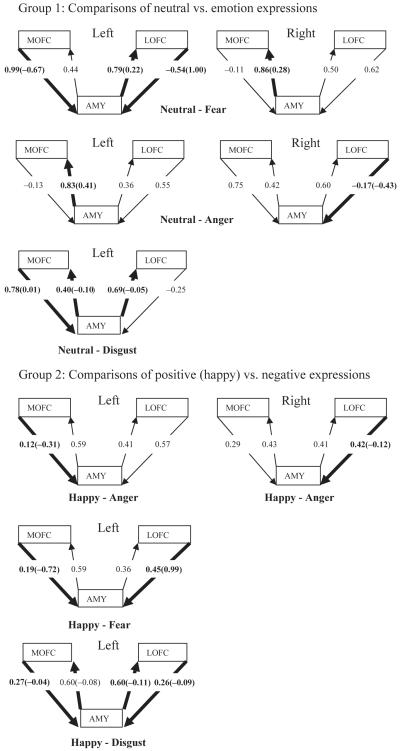

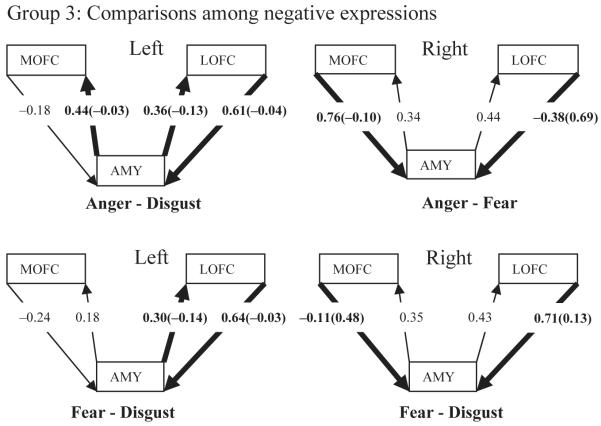

Figure 2 shows all SEM paths in the comparisons for which the null model was rejected. The comparisons for each hemisphere are organized into three groups: neutral expressions vs. each of the emotion expressions; positive (happy) expressions vs. each of the negative expressions; negative expressions vs. each other. Below we summarize the paths that differentiated each pair of emotion expressions in the three groups of comparisons.

Figure 2.

Path diagrams from the SEM models involving the amygdala (AMY), lateral orbitofrontal cortex (LOFC), and medial orbitofrontal cortex (MOFC). Models for the left hemisphere are on the left and those for the right hemisphere are on the right. Only those models that differed significantly from the null model are shown. Within these models, the paths that differed significantly for the two emotions are given in bold. These paths have two standardized path coefficients. The one without parentheses applies to the first emotion named for that model; the one with parentheses applies to the second emotion named. When there is only one standardized path coefficient it applies to both emotions in that model.

Group 1: Connectivity differences between neutral and emotion expressions

Neutral vs. fear

The null model was rejected for both hemispheres, Δχ2(4)=22.72, p<.001 and Δχ2(4)=12.04, p<.05, for the left and right hemispheres, respectively. The paths that differed significantly are summarized below.

Left hemisphere:

Right hemisphere:

Neutral vs. angry

The null model was rejected for both hemispheres, Δχ2(4)=18.52, p<.001 and Δχ2(4)=9.5, p<.05 for the left and right hemispheres, respectively. The paths that differed significantly are summarized below.

Left hemisphere:

Right hemisphere:

Neutral vs. happy

The null model could not be rejected for either hemisphere, Δχ2(4)=7.2, p>.05 and Δχ2(4)=7.09, p>.05, for the left and right hemispheres, respectively.

Neutral vs. disgust

The null model was rejected for the left hemisphere, Δχ2(4)=42.14, p<.001, but not for the right hemisphere, Δχ2(4)=7.74, p>.05. The paths that differed significantly are summarized below.

Left hemisphere:

Group 2: Connectivity differences between positive and negative emotion expressions

Happy vs. angry

The null model was rejected for both hemispheres, Δχ2(4)=9.55, p<.05 and Δχ2(4)=19.77, p<.001 for the left and right hemispheres, respectively. The paths that differed significantly are summarized below.

Left hemisphere:

Right hemisphere:

Happy vs. fear

The null model was rejected for the left hemisphere, Δχ2(4)=15.41, p<.01, but not for the right hemisphere, Δχ2(4)=6.17, p>.05. The paths that differed significantly are summarized below.

Left hemisphere:

Happy vs. disgust

The null model was rejected for the left hemisphere, Δχ2(4)=43.11, p<.001, but not for the right hemisphere, Δχ2(4)=8.8, p>.05. The paths that differed significantly are summarized below.

Left hemisphere:

Group 3: Connectivity differences between negative emotion expressions

Angry vs. fear

The null model was rejected for the right hemisphere, Δχ2(4)=20.35, p<.001, but not for the left hemisphere, Δχ2(4)=0.94, p>.05. The paths that differed significantly are summarized below.

Right hemisphere:

Angry vs. disgust

The null model was rejected for the left hemisphere, Δχ2(4)=29.38, p<.001, but not for the right hemisphere, Δχ2(4)=4.66, p>.05. The paths that differed significantly are summarized below.

Left hemisphere:

Fear vs. disgust

The null model was rejected for both hemispheres, Δχ2(4)=29.42, p<.001 and Δχ2(4)= 15.94, p<.01, for the left and right hemispheres, respectively. The paths that differed significantly are summarized below.

Left hemisphere:

Right hemisphere:

DISCUSSION

Our results provide the first evidence that faces varying in emotion expression elicit meaningful differences in amygdala–OFC effective connectivity, and the connectivity patterns we document provide support for both dimensional and categorical conceptualizations of emotion. It is noteworthy that this neural evidence for both categorical and dimensional representations of emotion expressions is consistent with a principal components analysis of physical similarities among emotion expressions that predicted both categorical recognition and dimensional ratings (Calder, Burton, Miller, Young, & Akamatsu, 2001).

Consistent with the view that emotions can viewed as points in a dimensional space defined by valence (Barrett, 2006; Fontaine et al., 2007; Russell & Barrett, 1999), greater effective connectivity from left MOFC to amygdala differentiated positive and neutral expressions from negatively valenced angry, disgust, and fear expressions. In addition, connectivity from the left MOFC to the amygdala did not differ when viewing emotion expressions with similar valence: angry vs. fear, angry vs. disgust, fear vs. disgust, and neutral vs. happy. Insofar as MOFC is activated by reward anticipation (Liu et al., 2007; O’Doherty et al., 2001), these results suggest that higher connectivity from left MOFC to amygdala signals a more positively valenced outcome, and they are consistent with evidence that positively valenced emotions are associated with greater left than right hemisphere activation (for a review, see Adolphs, 2002). The results also suggest that effective connectivity is more sensitive to hemispheric asymmetry in response to expression valence than are patterns of neural activation, which failed to show effects in the meta-analysis by Murphy et al. (2003).

Whereas connectivity in the left hemisphere reflected expression valence, right hemisphere connectivity appeared to reflect the dimension of perceiver ‘approach/withdrawal’. Specifically, greater effective connectivity from right LOFC to amygdala differentiated emotion expressions that may elicit approach responses in the perceiver (happy, neutral, and fear) from angry expressions that elicit perceiver withdrawal (Marsh et al., 2005; Zhang & Zebrowitz, 2007). Although one might expect disgust expressions to also elicit perceiver withdrawal, there is no clear behavioral evidence for this, and connectivity from right LOFC to amygdala did not differ for disgust vs. happy or angry expressions, although it was higher for fear than disgust. It should be noted that the right lateralization for approach/withdrawal revealed in these connectivity results is consistent with evidence that the right frontal lobe appears to be important in motor activation (Heilman, 1997). As for expression valence, our results may indicate that effective connectivity is more sensitive to the dimension of approach/withdrawal than are patterns of neural activation. However, the failure of Murphy et al. (2003) to find significant differences in the lateralization of neural activation to approach/withdrawal emotions had organized the emotions according to expressor approach/withdrawal, where we too found no consistent lateralization or other differences in effective connectivity. Thus, it is also possible that an inspection of neural activation patterns that are organized by perceiver approach/withdrawal tendencies would show significant lateralization.

Finally, consistent with the view that emotions are discrete categories represented by distinct patterns of behavior and physiological responses (Ekman et al., 1999a,b; Lerner et al., 2007; Rainville et al., 2006), there were unique patterns of connectivity in response to fear, angry, and disgust expressions although not in response to happy expressions, which did not differ from neutral ones. Angry, an expression that elicits withdrawal in the perceiver, showed weaker connectivity from right LOFC to amygdala when compared with happy, fear, or neutral expressions. Since angry was differentiated from disgust by stronger left hemisphere connectivity from amygdala to MOFC and LOFC as well as from left LOFC to amygdala, these four paths taken together differentiate angry from all other emotion expressions. Fear showed stronger connectivity from left LOFC to amygdala when compared with all other expressions except angry. Since fear was differentiated from angry by stronger right hemisphere connectivity from LOFC to amygdala and weaker connectivity from MOFC to amygdala, these three paths taken together differentiate fear from all other expressions. Disgust showed weaker connectivity from left amygdala to LOFC when compared with all other expressions. This result coupled with the relatively low levels of connectivity for disgust expressions for all the paths we examined is consistent with other evidence that the insula may play a more central role than the amygdala for processing disgust (Heberlein & Adolphs, 2007; Kipps, Duggins, McCusker, & Calder, 2007; Sambataro et al., 2006). Although happy expressions were differentiated from disgust, angry, and fear by greater connectivity from left MOFC to amygdala, this path did not differ for happy vs. neutral expressions and neither did any other path in our analyses. This latter finding certainly should not be taken to mean that happy expressions are not a discrete category, since they may well engage unique connectivity involving other brain regions previously found to be central to processing happy faces, such as the prefrontal cortex or cingulate gyrus (Dolan et al., 1996; Kesler/West et al., 2001; Phillips et al., 1998). In sum, our connectivity results for each discrete emotion expression complement the Murphy et al. (2003) meta-analysis, which showed unique patterns of neural activation to fear, angry, and disgust expressions, but not to happy expressions, which did not differ from sad ones.

Some limitations of the present research should be noted. First, we focused on only three of the many brain regions involved in the neural response to emotion faces (Adolphs, 2002; Phan et al., 2004). Amygdala, MOFC, and LOFC are key structures, but additional research is needed to elucidate effective connectivity among all the relevant regions. Doing so for all possible connections among all regions is a prodigious task, particularly if one takes account of temporal effects that allow for recursive connections. This undertaking will require the development of theoretically grounded hypotheses regarding regions with known anatomical connections using models such as that proposed by Adolphs (2002).

The absence of temporal data is a second limitation in our research. Such data are needed to elucidate how effective connectivity influences the level of neural activation in the regions that are linked. For example, the question remains as to whether effective connectivity from OFC to amygdala has an excitatory or inhibitory effect on amygdala activation and whether the effect is the same across the emotion expressions that elicited similar connectivity. These questions could be answered by combining EEG or MEG data with fMRI.

A third limitation of the present research is that because SEM is performed across subjects, it does not take individual differences into account. In addition to determining how much individual variation there is, it would be interesting to identify the sources of that variation. Given that connectivity differentiated emotions according to the likely approach/withdrawal behavior of the perceiver, it would be interesting to see if it is moderated by variations in the behavioral inhibition system (BIS), which is associated with avoiding punishing events, and the behavioral activation system (BAS), which is associated with approaching rewarding events (Carver & White, 1994). It would also be interesting to examine sex differences in effective connectivity when one is viewing emotion expressions, since this might help to resolve an interesting paradox. Whereas women are more accurate decoders of emotion expression than men (Hall & Matsumoto, 2004), men but not women showed differential neural activation to different emotion expressions (Kesler/West et al., 2001).

CONCLUSIONS

The present findings provide an important step in the effort to understand how emotion expressions are represented in the brain, and they highlight the advantages of considering effective connectivity, which differentiates emotions on the dimensions of valence and perceiver approach/withdrawal, as well as into unique categories. Our results also highlight the utility of conceptualizing emotions not only in terms of the approach/withdrawal tendencies of the expressor, but also in terms of those of the perceiver when examining neural activation to emotion expressions. A full understanding of how emotion expressions are represented in the brain will ultimately require more ecologically valid stimuli together with an examination of connectivity between other ROIs involved in emotion perception as well as temporal data that can elucidate how effective connectivity influences the level of neural activation in the regions that are linked.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health Grants (grant numbers MH066836 and K02MH72603) to L.A.Z.

REFERENCES

- Adolphs R. Recognizing emotion from facial expressions: Psychological and neurological mechanisms. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews. 2002;1(1):21–62. doi: 10.1177/1534582302001001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks SJ, Eddy KT, Angstadt M, Nathan PJ, Phan KL. Amygdala–frontal connectivity during emotion regulation. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2007;2(4):303–312. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsm029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbas H, Schoenbaum G, Gottfried JA, Murray EA, Ramus SJ. Linking affect to action: Critical contributions of the orbitofrontal cortex. Blackwell; Malden, MA: 2007. Specialized elements of orbitofrontal cortex in primates; pp. 10–32. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF. Are emotions natural kinds? Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2006;1(1):28–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF, Wager TD. The structure of emotion: Evidence from neuroimaging studies. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15(2):79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. A new incremental fit index for general structural equation models. Sociological Methods Research. 1989a;17:303–316. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. Wiley; New York: 1989b. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Berntson GG, Larsen JT, Poehlmann KM, Ito TA. The psychophysiology of emotion. In: Lewis M, Haviland-Jones JM, editors. Handbook of emotions. 2nd ed Guilford Press; New York: 2000. pp. 173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Calder AJ, Burton AM, Miller P, Young AW, Akamatsu S. A principal component analysis of facial expressions. Vision Research. 2001;41(9):1179–1208. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(01)00002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calder AJ, Keane J, Manly T, Sprengelmeyer R, Scott S, Nimmo-Smith I, et al. Facial expression recognition across the adult life span. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41(2):195–202. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael ST, Price JL. Connectional networks within the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex of macaque monkeys. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1996;371:179–207. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960722)371:2<179::AID-CNE1>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67(2):319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Dale AM. Optimal stimulus sequences for event-related fMRI. Human Brain Mapping. 1999;8:109–114. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1999)8:2/3<109::AID-HBM7>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson R. What does the prefrontal cortext “do” in affect: Perspectives on frontal EEG asymmetry research. Biological Psychology. 2004;67:219–233. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, Ekman P, Saron CD, Senulis JA, Friesen WV. Approach–withdrawal and cerebral asymmetry: Emotional expression and brain physiology I. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58(2):330–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Marco G, de Bonis M, Vrignaud P, Henry-Feugeas MC, Peretti I. Changes in effective connectivity during incidental and intentional perception of fearful faces. NeuroImage. 2006;30(3):1030–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan RJ, Fletcher P, Morris J, Kapur N, Deakin JFW, Frith CD. Neural activation during covert processing of positive emotional facial expressions. Neuroimage. 1996;4:194–200. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P, Dalgleish T, Power MJ. Basic emotions. In: Dalgleish T, Power MJ, editors. Handbook of cognition and emotion. Wiley; New York: 1999a. pp. 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P, Dalgleish T, Power MJ. Facial expressions. In: Dalgleish T, Power MJ, editors. Handbook of cognition and emotion. Wiley; New York: 1999b. pp. 301–320. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P, Friesen W. Pictures of facial affect. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Fairhall SL, Ishai A. Effective connectivity within the distributed cortical network for face perception. Cerebral Cortex. 2007;17(10):2400–2406. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine JRJ, Scherer KR, Roesch EB, Ellsworth PC. The world of emotions is not two-dimensional. Psychological Science. 2007;18(12):1050–1057. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghashghaei HT, Barbas H. Pathways for emotion: Interactions of prefrontal and anterior temporal pathways in the amygdala of the rhesus monkey. Neuroscience. 2002;115(4):1261–1279. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00446-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JA, Matsumoto D. Gender differences in judgments of multiple emotions from facial expressions. Emotion. 2004;4(2):201–206. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.4.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby JV, Hoffman EA, Gobbini MI. Human neural systems for face recognition and social communication. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51(1):59–67. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01330-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heberlein AS, Adolphs R. Neurobiology of emotion recognition: Current evidence for shared substrates. In: Harmon-Jones E, Winkielman P, editors. Social neuroscience: Integrating biological and psychological explanations of social behavior. Guilford Press; New York: 2007. pp. 31–55. [Google Scholar]

- Heilman KM. The neurobiology of emotional experience. Journal of Neuropsychiatry. 1997;9:439–448. doi: 10.1176/jnp.9.3.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iidaka T, Omori M, Murata T, Kosaka H, Yone-kura Y, Tomohisa O, et al. Neural interaction of the amygdala with the prefrontal and temporal cortices in the processing of facial expressions as revealed by fMRI. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2001;13(8):1035–1047. doi: 10.1162/089892901753294338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishai A, Schmidt CF, Boesiger P. Face perception is mediated by a distributed cortical network. Brain Research Bulletin. 2005;67(1):87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2005.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage. 2002;17(2):825–841. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)91132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joreskog KG, Sorbom D. LISREL 8.80 for Windows [Computer Software] Scientific Software International, Inc; Lincolnwood, IL: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kesler/West ML, Andersen AH, Smith CD, Avison MJ, Davis CE, Kryscio RJ, Blonder LX. Neural substrates of facial emotion processing using fMRI. Cognitive Brain Research. 2001;11:213–226. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(00)00073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipps CM, Duggins AJ, McCusker EA, Calder AJ. Disgust and happiness recognition correlate with anteroventral insula and amygdala volume respectively in preclinical Huntington’s disease. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2007;19(7):1206–1217. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.7.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight RT. Neural networks debunk phrenology. Science. 2007;316(5831):1578–1579. doi: 10.1126/science.1144677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence AD, Murphy FC, Calder AJ, Yiend J. Dissociating fear and disgust: Implications for the structure of emotions. In: Yiend J, editor. Cognition, emotion and psychopathology: Theoretical, empirical and clinical directions. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2004. pp. 149–171. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner JS, Dahl RE, Hariri AR, Taylor SE. Facial expressions of emotion reveal neuroendocrine and cardiovascular stress responses. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61(2):253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Powell DK, Wang H, Gold BT, Corbly CR, Joseph JE. Functional dissociation in frontal and striatal areas for processing of positive and negative reward information. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(17):4587–4597. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5227-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh AA, Ambady N, Kleck RE. The effects of fear and anger facial expressions on approach and avoidance related behaviors. Emotion. 2005;5:119–124. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh AR, Gonzalez-Lima F. Structural equation modeling and its application to network analysis in functional brain imaging. Human Brain Mapping. 1994;2:2–22. [Google Scholar]

- Morris JS, Friston KJ, Buchel C, Frith CD, Young AW, Calder AJ, et al. A neuromodulatory role for the human amygdala in processing emotional facial expressions. Brain: A Journal of Neurology. 1998;121(1):47–57. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy FC, Nimmo-Smith I, Lawrence AD. Functional neuroanatomy of emotions: A meta-analysis. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2003;3(3):207–233. doi: 10.3758/cabn.3.3.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Gross JJ. The cognitive control of emotion. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2005;9(5):242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty J, Kringelbach ML, Rolls ET, Hornak J, Andrews C. Abstract reward and punishment representations in the human orbitofrontal cortex. Nature Neuroscience. 2001;4(1):95–102. doi: 10.1038/82959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty J, Winston J, Critchley H, Perrett D, Burt DM, Dolan RJ. Beauty in a smile: The role of medial orbitofrontal cortex in facial attractiveness. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41(2):147–155. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan KL, Wager TD, Taylor SF, Liberzon I. Functional neuroimaging studies of human emotions. CNS Spectrums. 2004;9(4):258–266. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900009196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps EA. Emotion and cognition: Insights from studies of the human amygdala. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;57:27–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips ML, Bullmore ET, Howard R, Woodruff PWR, Wright IC, Williams SCR, et al. Investigation of facial recognition memory and happy and sad facial expression perception: An fMRI study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging Section. 1998;83:127–138. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(98)00036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainville P, Bechara A, Naqvi N, Damasio AR. Basic emotions are associated with distinct patterns of cardiorespiratory activity. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2006;61(1):5–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET. A theory of emotion and consciousness, and its application to understanding the neural basis of emotion. In: Gazzaniga MS, editor. The cognitive neurosciences. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1995. pp. 1091–1106. [Google Scholar]

- Russell JA, Barrett LF. Core affect, prototypical emotional episodes, and other things called emotion: Dissecting the elephant. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76(5):805–819. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.5.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambataro F, Dimalta S, Di Giorgio A, Taurisano P, Blasi G, Scarabino T, et al. Preferential responses in amygdala and insula during presentation of facial contempt and disgust. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;24(8):2355–2362. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Human Brain Mapping. 2002;17(3):143–155. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein JL, Wiedholz LM, Bassett DS, Weinberger DR, Zink CF, Mattay VS, et al. A validated network of effective amygdala connectivity. NeuroImage. 2007;36(3):736–745. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuilleumier P, Armony JL, Driver J, Dolan RJ. Distinct spatial frequency sensitivities for processing faces and emotional expressions. Nature Neuroscience. 2003;6(6):624–631. doi: 10.1038/nn1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis JD. Orbitofrontal cortex and its contribution to decision-making. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2007;30:31–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams LM, Das P, Liddell BJ, Kemp AH, Rennie CJ, Gordon E. Mode of functional connectivity in amygdala pathways dissociates level of awareness for signals of fear. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26(36):9264–9271. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1016-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolrich MW, Ripley BD, Brady M, Smith SM. Temporal autocorrelation in univariate linear modeling of FMRI data. Neuroimage. 2001;14(6):1370–1386. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajonc RB, McIntosh DN. Emotions research: Some promising questions and some questionable promises. Psychological Science. 1992;3(1):70–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zebrowitz LA, Fellous JM, Mignault A, Andreoletti C. Trait impressions as overgeneralized responses to adaptively significant facial qualities: Evidence from connectionist modeling. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2003;7(3):194–215. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0703_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrowitz LA, Luevano VX, Bronstad PM, Aharon I. Neural activation to babyfaced men matches activation to babies. Social Neuroscience. 2007 doi: 10.1080/17470910701676236. Epub ahead of print 12 October 2007. DOI:10.1080/17470910701676236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrowitz LA, Olson K, Hoffman K. Stability of babyfaceness and attractiveness across the life span. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1993;64:453–466. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zebrowitz LA. Mapping the behavioral affordances of face stimuli. Poster presented at the 30th European Conference on Visual Perception; Arezzo, Italy. Aug, 2007. [Google Scholar]