Abstract

Summary: Understanding the mechanisms governing the regeneration capabilities of many organisms is a fundamental interest in biology and medicine. An ever-increasing number of manipulation and molecular experiments are attempting to discover a comprehensive model for regeneration, with the planarian flatworm being one of the most important model species. Despite much effort, no comprehensive, constructive, mechanistic models exist yet, and it is now clear that computational tools are needed to mine this huge dataset. However, until now, there is no database of regenerative experiments, and the current genotype–phenotype ontologies and databases are based on textual descriptions, which are not understandable by computers. To overcome these difficulties, we present here Planform (Planarian formalization), a manually curated database and software tool for planarian regenerative experiments, based on a mathematical graph formalism. The database contains more than a thousand experiments from the main publications in the planarian literature. The software tool provides the user with a graphical interface to easily interact with and mine the database. The presented system is a valuable resource for the regeneration community and, more importantly, will pave the way for the application of novel artificial intelligence tools to extract knowledge from this dataset.

Availability: The database and software tool are freely available at http://planform.daniel-lobo.com.

Contact: michael.levin@tufts.edu

1 INTRODUCTION

The main goal in regenerative biology is to find the control mechanisms that allow many organisms to regenerate missing appendages or organs, including the brain. Planarian worms are of special interest because, despite their complexity (they possess a brain, eyes, sensory and digestive systems, musculature, etc.), they exhibit an outstanding regenerative capacity: cutting a worm in many pieces results in a regenerated complete worm from each piece (Reddien and Sánchez Alvarado, 2004). However, despite the current outstanding efforts of surgical, pharmacological and molecular genetic experiments, no model exist that can explain more than one or two aspects of planarian regeneration (Lobo et al., 2012).

What is needed now for the discovery of constructive, mechanistic and predictive models of regeneration are automated computational tools and a centralized database that unambiguously stores experimental assays and outcomes in a formal structure, permitting efficient retrieval of the developmental knowledge acquired during >100 years of planarian experiments. Certainly, the goals of true Systems Biology require the ability to manipulate information about higher-order properties of pattern control in addition to gene- and protein-level data.

Ontologies have been proposed to standardize the vocabulary to describe phenotypes (Smith and Eppig, 2009) and are in use in valuable databases linking genomic and phenotype data (Groth et al., 2007). However, current phenotype ontologies are based in well-defined textual descriptions, which are not adequate for regeneration data and cannot be interpreted by automated algorithms.

Here, we present a novel database based on a mathematical graph formalism, which can describe unambiguously the geometric relations between morphological parts, and a computational tool to mine and extract knowledge from this vast amount of data from the regeneration field.

2 METHODS

2.1 Formalism for morphologies and manipulations

We have created a formalism based on graphs to encode the resultant morphologies and manipulations of regenerative experiments (Lobo et al., 2013). Mathematical graphs are ideal to encode relationships between individuals and have been previously used to encode morphologies (Lobo et al., 2011). The formalism divided a morphology into adjacent regions (graph nodes) connected to each other (graph edges). The geometrical characteristics of the regions (connection angles, distances, shapes, type, etc.) are stored as node and link labels. Importantly, the formalism permits automatic comparisons between morphologies: we implemented a metric to quantify the difference between two morphologies based on the graph edit distance algorithm.

The experiment manipulations are encoded in a tree structure. Nodes represent specific manipulations (cuts, irradiation and transplantations) where links define the order and relations between manipulations. This approach permits encode the majority of published planarian regenerative experiments.

2.2 Database implementation and curation

The centralized database of planarian experiments was implemented using the database engine SQLite (public domain). A database is contained in a single file, which includes both the schema and the data. This facilitates the access, extension and sharing of databases.

The database contains experiments from articles in the literature reporting the most fundamental discoveries in planarian pattern regeneration, including the regeneration along the anterior–posterior and medial–lateral axis under specific cuttings, amputations, transplantations, irradiation, drugs and RNA interference (RNAi) treatments. Future versions of the database and software tool will be expanded to include specific cell types, gene expression and patterning along the dorsal–ventral axis.

2.3 Software implementation

Planform was implemented in C++ and compiled as a native stand-alone desktop application for Microsoft Windows, Mac OS X and Linux. Planform can create, read and write planarian database files.

3 RESULTS

At the time of writing, the centralized database contains 1139 experiments manually curated from 74 publications from the scientific literature, and we are continually expanding it.

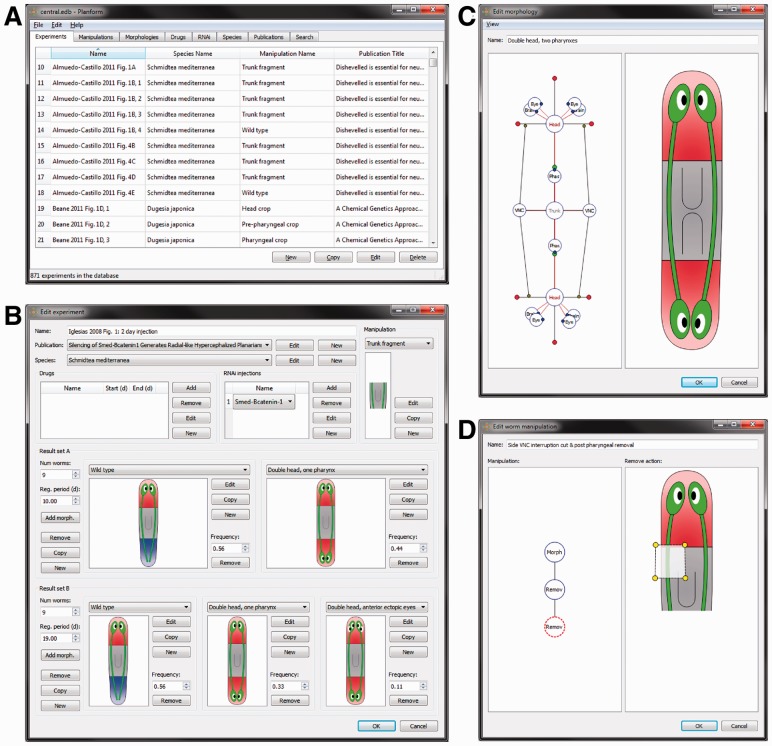

Figure 1 shows screenshots of Planform. The main window lists all the experiments, manipulation, morphologies, drugs, RNAi, species and publications stored in the database (Fig. 1A). A form is used to introduce the characteristics of an experiment (publication, drugs, manipulation, resultant morphologies, etc.); these characteristics can be selected from the database if they are similar to previously introduced experiments, or defined anew (Fig. 1B). An experiment can define several different morphological outcomes, depending on the penetrance of the treatment and the elapsed regeneration time. To facilitate the interpretation of the formalism by the user, Planform draws cartoon representations of the formal morphologies and manipulations in real time, so that the user can immediately see a schematic of the phenotype being described. To introduce new morphologies (Fig. 1C) and manipulations (Fig. 1D), the tool presents an interactive graphical representation, which permits one to drag vertices and parameters, as well as to create and delete regions/organs, and perform other edits. The user can introduce a new morphology or manipulation by starting from scratch or by copying and editing an existing one.

Fig. 1.

Screenshots of the graphical software tool, Planform, used to introduce and query experiments in the database. (A) Main window, listing the experiments stored in the database. (B) Experiment form, including its details, procedure, manipulation, and resultant morphologies. (C) Interface to specify a morphology, based on an interactive graph representation and an automatically-generated cartoon. (D) Interface to specify a manipulation, defined as a hierarchy of elemental actions

Importantly, Planform includes a search module that permits a scientist to query for experiments, worm manipulations, regenerated morphologies, etc. stored in the database. A query is defined by the type of entity to search (experiments, manipulations, morphologies, drugs, RNAi, species or publications), a characteristic to search for (name, publication title or year, drug or RNAi names or number of specific organs or regions), a comparator operator (contains, equal, less or greater) and a free text with which to compare the operator. In this way, any scientist can easily find specific results contained in the database according to a familiar criterion.

4 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The continued expansion of experimental results in pattern formation necessitates the development of computational tools to help derive insight from data. Planform is the first database specialized on regenerative experiments, which centralize in a clear and mathematical manner the current knowledge of planarian regeneration. It uses a novel formalization ontology based on graph representations of morphologies and manipulations, which are amenable to automated computational analysis. This represents the beginnings of an expert system that can encapsulate the field’s sum total of functional knowledge about worm patterning and its experimental manipulation. We also implemented a software tool to facilitate the query, input and search of information in the centralized database of planarian experiments. While this system is meant to facilitate the understanding of planarian regeneration, it is important to keep in mind that the fundamental principles are generally applicable to many model systems and all aspects of developmental biology.

The database centralizing the planarian experimental knowledge combined with the software tool Planform together represent an invaluable new kind of bioinformatics tool—a first step towards expert systems that store and process the combined knowledge of the developmental and regenerative research communities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Emma Marshall for beta-testing help and Junji Morokuma, Wendy S. Beane, Tim Andersen, Jeffrey W. Habig and the Levin Lab members for valuable suggestions.

Funding: National Science Foundation (EF-1124651), National Institutes of Health (GM078484), US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (#W81XWH-10-2-0058) and G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Groth P, et al. PhenomicDB: a new cross-species genotype/phenotype resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D696–D699. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo D, et al. Graph grammars with string-regulated rewriting. Theor. Comp. Sci. 2011;412:6101–6111. [Google Scholar]

- Lobo D, et al. Modeling planarian regeneration: a primer for reverse-engineering the worm. PLoS Comp. Biol. 2012;8:e1002481. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo D, et al. Towards a bioinformatics of patterning: a computational approach to understanding regulative morphogenesis. Biology Open. 2013;2:156–169. doi: 10.1242/bio.20123400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddien P, Sánchez Alvarado A. Fundamentals of planarian regeneration. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2004;20:725–757. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.095114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CL, Eppig JT. The mammalian phenotype ontology: enabling robust annotation and comparative analysis. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2009;1:390–399. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]