Abstract

Purpose

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations are the leading cause of hospital admission and death among chronic bronchitis (CB) patients. This study estimated annual COPD exacerbation rates, related costs, and their predictors among patients treated for CB.

Methods

This was a retrospective study using claims data from the HealthCore Integrated Research Database (HIRDSM). The study sample included CB patients aged ≥ 40 years with at least one inpatient hospitalization or emergency department visit or at least two office visits with CB diagnosis from January 1, 2004 to May 31, 2011, at least two pharmacy fills for COPD medications during the follow-up year, and ≥2 years of continuous enrollment. COPD exacerbations were categorized as severe or moderate. Annual rates, costs, and predictors of exacerbations during follow-up were assessed.

Results

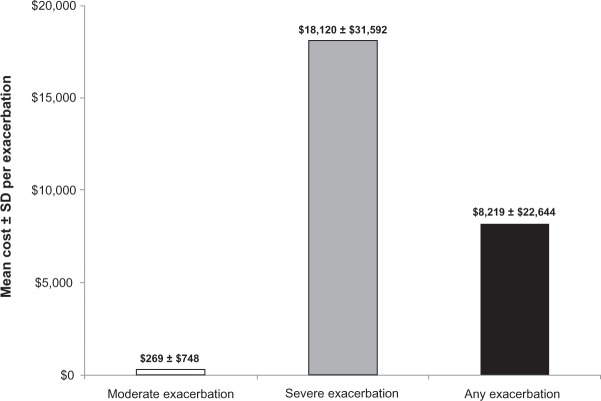

A total of 17,382 individuals treated for CB met the selection criteria (50.6% female; mean ± standard deviation age 66.7 ± 11.4 years). During the follow-up year, the mean ± standard deviation number of COPD maintenance medication fills was 7.6 ± 6.3; 42.6% had at least one exacerbation and 69.5% of patients with two or more exacerbations during the 1 year prior to the index date (baseline period) had any exacerbation during the follow-up year. The mean ± standard deviation cost per any exacerbation was $269 ± $748 for moderate and $18,120 ± $31,592 for severe exacerbation. The number of baseline exacerbations was a significant predictor of the number of exacerbations and exacerbation costs during follow-up.

Conclusion

Exacerbation rates remained high among CB patients despite treatment with COPD maintenance medications. New treatment strategies, designed to reduce COPD exacerbations and associated costs, should focus on patients with high prior-year exacerbations.

Keywords: chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, exacerbations, maintenance medications, managed care

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is estimated to affect approximately 24 million US adults.1 It comprises the majority of chronic lower respiratory disease, a condition that has risen to the third leading cause of death in the US.2 Chronic bronchitis (CB), characterized by presence of a chronic cough with sputum production for ≥3 months in each of 2 consecutive years, accounts for ≥70% of COPD cases – with emphysema being the other component.3 However, CB often overlaps with emphysema among patients in the real world.4 Exacerbations – defined as an event in the natural course of the disease characterized by a change in the patient’s baseline dyspnea, cough, and/or sputum that is beyond normal day-today variations, is acute in onset, and may warrant a change in regular medication in a patient with underlying COPD5–8 – are the most frequent cause of hospital admission and death among COPD patients.9,10 Hospital mortality of patients admitted for COPD exacerbations is high and their long-term outcomes are poor.11 COPD exacerbations contribute to poor health-related quality of life,12 and there is evidence that frequent exacerbations accelerate the progression of the disease. Patients with lower levels of lung function are more likely to experience more exacerbations, and frequent exacerbations may lead to reduced lung function.8

Appropriate maintenance medications exist for COPD and have been shown to lower the risk of exacerbations. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines recommend that an effective COPD management plan should include assessment and monitoring of the disease, reduction in risk factors, management of stable COPD, and management of exacerbations.13 The GOLD guidelines recommend maintenance pharmacotherapy whereby long-acting β2-agonists (LABA) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA) are preferred over short-acting β2-agonists (SABA) and short-acting muscarinic antagonists (SAMA). The GOLD guidelines further recommend that combined use of LABA and LAMA may be considered if symptoms are not improved with single agents. Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, or theophylline may also be added for severely ill patients.

Identifying real world information on COPD exacerbations from administrative claims data is possible using health care resource utilization and treatments that are indicative of an exacerbation.14 To the best of the authors’ knowledge, limited work has estimated the rate, costs, and predictors of COPD exacerbations among managed care CB patients treated with COPD maintenance medications. This study attempts to addresses this gap by focusing on the following two objectives: (1) to estimate real-world annual COPD exacerbation rates and related costs among CB patients from a large managed care population who were treated with maintenance medications, and (2) to examine predictors of subsequent exacerbations and costs during follow-up as a function of patient baseline characteristics.

Material and methods

This retrospective observational study utilized claims data from the HealthCore Integrated Research Database (HIRDSM; HealthCore Inc, Wilmington, DE). The HIRDSM consists of longitudinal medical, pharmacy, and enrollment claims data from 14 major commercial health plans across the US representing approximately 45 million commercially insured lives. All study materials were handled in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, and a limited dataset (as defined in the privacy regulations issued under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) was used for this analysis.

Sample selection

Eligible patients met all of the following criteria: (1) at least one inpatient hospitalization or emergency department visit or at least two physician office visits with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnosis code of 491.xx between January 1, 2004 and May 31, 2011; (2) at least two pharmacy fills for COPD medication(s) (LAMA, LABA, ICS, fixed dose LABA plus ICS inhaler, SABA, or SAMA), with at least one fill being a COPD maintenance medication (ie, LAMA, LABA, ICS, or fixed dose LABA plus ICS inhaler) during the follow-up period; and (3) continuous medical and pharmacy health insurance enrollment during 2 calendar years (one before and one after the index date). The index date was defined as the first record of prescription fill for a COPD medication within 18 months of the most recent CB diagnosis. This index date definition was chosen to capture the most recent treatment patterns among eligible study patients. The 1-year period prior to the index date was defined as the “baseline year” and was used to measure patient baseline characteristics, whereas the 1-year period after the index date was defined as the “follow-up year” and was used to measure follow-up exacerbation rates and costs. Patients were excluded from the study if they met any of the following criteria: (1) were younger than 40 years of age on the index date; (2) had at least one medical claim for a potential COPD confounding condition at baseline (asthma, cystic fibrosis, respiratory tract cancer, tuberculosis, interstitial lung diseases, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, or a malignant neoplasm of the thymus, heart, or mediastinum); and (3) were long-term oral corticosteroid (OCS) users defined as having a supply of ≥ 182 days any time during the study period.15

In addition to the overall sample, a subgroup of patients with history of frequent exacerbations – including patients who met all study criteria and had two or more exacerbations of any type (please see outcomes assessment section for definition of exacerbations) during the baseline year – were identified in this study for descriptive subgroup analysis.

Study measures

Baseline characteristics included patient demographic and health plan characteristics and COPD-related major comorbidities. Comorbidity burden was measured using the Deyo–Charlson Comorbidity Index (DCI) - COPD diagnosis was excluded from the calculation of this score.16 Percentages of patients with COPD medication class use on the index date were described. The number of fills for various COPD maintenance medications during the follow-up year was described. In addition, the number fills for rescue COPD medications (SABA and SAMA) were used as a proxy to approximate CB severity and were described.

Outcomes assessment

The total number of exacerbation events (annual exacerbation rate) and total annual exacerbation-related direct costs (exacerbation costs) occurring within the follow-up year were the outcomes used in this study. Exacerbation events were classified as moderate, severe, or any (either moderate or severe). A moderate exacerbation was identified by either an emergency department visit with a primary COPD diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnosis codes: 491.xx, 492.xx, 496.xx)15,17 or a fill of an OCS15,17,18 within 7 days of the date of a physician office visit with COPD diagnosis. A severe exacerbation was identified by a hospital admission with a primary COPD diagnosis.17,19

The following rules were applied to measure COPD exacerbation events: (1) exacerbations were measured for ≤14 days from the date of a qualifying event;20 (2) a maximum of one exacerbation of the most severe type was recorded during any 14-day window; and (3) a new 14-day window was triggered by an exacerbation of any type occurring after the end date of the previous exacerbation time window. Exacerbation costs were summed during the 14-day window defined above and included all direct costs of inpatient hospitalizations with a primary COPD diagnosis, emergency department visits with a primary COPD diagnosis, and costs of physician office visits with COPD diagnosis that were followed with an OCS fill within 7 days (including costs of an OCS fill).

Statistical analysis

Key baseline patient characteristics were summarized using mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous outcomes, and counts and percentages for categorical variables. The percentage of patients with at least one COPD exacerbation and the number of unique exacerbations were described among the overall sample and among the subgroup with at least two exacerbations during their baseline year. Total estimated exacerbation costs per patient and per exacerbation were also calculated among the overall sample and among the subgroup with at least two exacerbations during their baseline year. Costs were adjusted to mid-2011 figures using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index.21 A Poisson regression model was fitted to model total per-patient exacerbation rates during follow-up as a function of baseline exacerbations, controlling for pertinent confounders including baseline demographic, health plan, and clinical characteristics. In addition, a generalized linear model with a log–link function (gamma distribution) was fitted to model total per-patient exacerbation costs during the follow-up year as a function of baseline exacerbations, controlling for baseline demographic, health plan, and clinical characteristics. Exponentiated regression estimates (ie, rate ratio [RR]), standard error, and 95% confidence interval limits were reported for the Poisson and generalized linear models. All statistical analyses were conducted in SAS® version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Study population

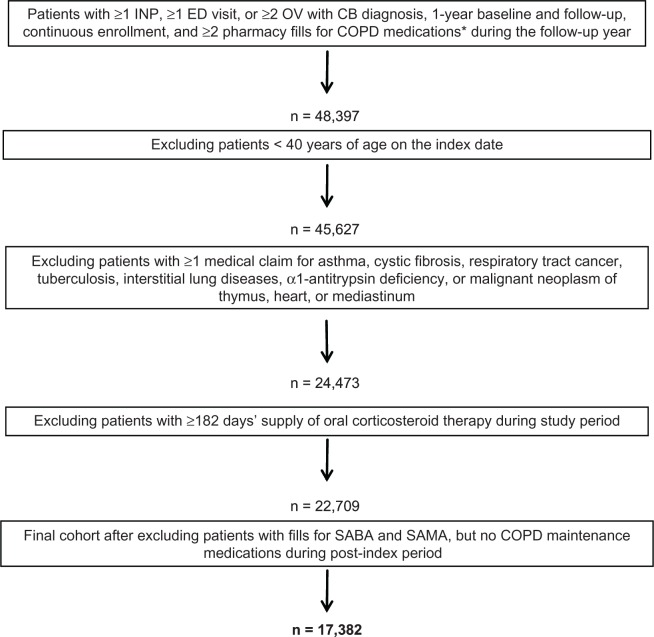

As described in Figure 1, of the 48,397 patients who met the study inclusion criteria of CB diagnosis, treatment with COPD maintenance medication during the follow-up year, and continuous enrollment criteria, 2770 (5.7%) were excluded because they were <40 years on the index date; 21,154 (43.7%) were excluded because they had at least one exclusionary condition (asthma accounted for the majority of these exclusions 20,081 [80.8%]); 1764 (3.6%) were excluded because they were long-term OCS users; and 5327 (11.0%) were excluded because they had fills for only SABA/SAMA with no fills for COPD maintenance medications during the follow-up year. The overall sample that met all study criteria and analyzed in this study was 17,382.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient attrition.

Note: *Medications include: inhaled corticosteroids, long-acting β2-agonists, SABA, and SAMA.

Abbreviations: CB, chronic bronchitis; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED, emergency department; INP, inpatient hospitalization; OV, physician office visit; SABA, short-acting β2-agonist; SAMA, short-acting muscarinic antagonist.

Baseline characteristics

As presented in Table 1, 50.6% of the study sample were women and 53.6% were ≥65 years of age. The mean ± SD age was 66.7 ± 11.4 years among the overall study sample. The mean ± SD DCI score was 1.3 ± 1.7 during the baseline year. Among the comorbid conditions examined in this study, hypertension (56.0%), cardiovascular disease (39.9%), acute bronchitis and bronchiolitis (22.1%), diabetes mellitus (21.2%), and acute sinusitis (9.6%) were the most common.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics during the baseline year

| Characteristic | Patients (n = 17,382) |

|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 8801 (50.6%) |

| Age groups, n (%) | |

| 40–54 years | 2632 (15.1%) |

| 55–64 years | 5431 (31.3%) |

| ≥65 years | 9319 (53.6%) |

| Age, mean ± SD | 66.7 ± 11.4 |

| US geographic region | |

| Northeast | 3707 (21.3%) |

| Midwest | 5321 (30.6%) |

| South | 5776 (33.2%) |

| West | 2526 (14.5%) |

| Unknown | 52 (0.3%) |

| Health plan type | |

| PPO | 11,035 (63.5%) |

| HMO | 3852 (22.2%) |

| Other | 2495 (14.4%) |

| Baseline comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Acute bronchitis and bronchiolitis | 3843 (22.1%) |

| Acute sinusitis | 1660 (9.6%) |

| Acute upper respiratory infection | 1386 (8.0%) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 1290 (7.4%) |

| Chronic sinusitis | 748 (4.3%) |

| Other respiratory infections | 661 (3.8%) |

| Insomnia | 528 (3.0%) |

| Acute laryngitis and tracheitis | 106 (0.6%) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 6936 (39.9%) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 4578 (26.3%) |

| Congestive heart failure | 2760 (15.9%) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1894 (10.9%) |

| Stroke or transient ischemic attack | 1495 (8.6%) |

| Myocardial infarction | 871 (5.0%) |

| Rheumatologic disease, n (%) | 390 (2.2%) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 3689 (21.2%) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 9732 (56.0%) |

| Anxiety, n (%) | 1345 (7.7%) |

| Depression, n (%) | 1301 (7.5%) |

| Malignancy, n (%) | 1597 (9.2%) |

| Baseline DCI score*, mean ± SD | 1.3 ± 1.7 |

Note:

Calculation excluded chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Abbreviations: DCI, Deyo–Charlson Comorbidity Index; HMO, health maintenance organization; PPO, preferred provider organization; SD, standard deviation.

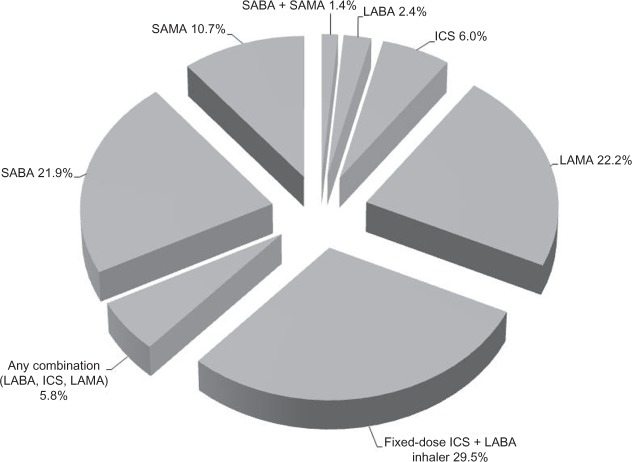

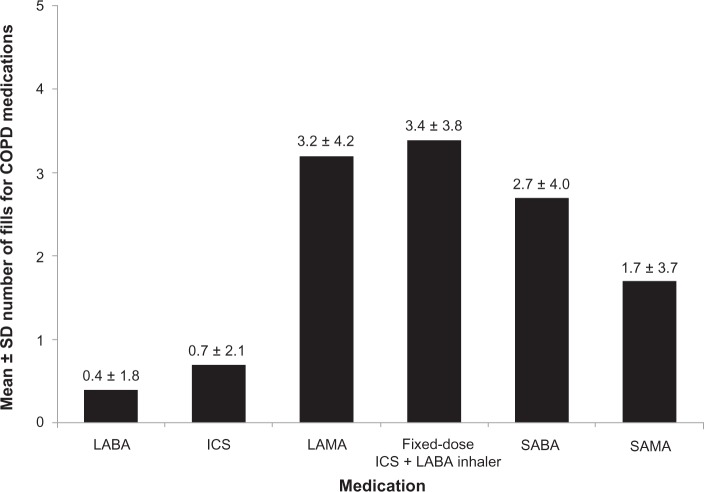

As depicted in Figure 2, 22.2% of the study sample was indexed on LAMA, 29.5% on fixed dose ICS plus LABA inhaler, 6.0% on ICS, 2.4% on LABA, and 5.8% on any combination of these maintenance medications. The remaining patients were indexed on SABA (21.9%), SAMA (10.7%), or both (1.4%), keeping in mind that these patients had to have at least one maintenance medication during the follow-up year per the study criteria. As described in Figure 3, fixed dose ICS plus LABA inhaler and LAMA were the most frequently filled COPD maintenance medications (mean ± SD 3.4 ± 3.8 and 3.2 ± 4.2, respectively), compared with ICS and LABA (mean ± SD 0.7 ± 2.1 and 0.4 ± 1.8, respectively); overall, the mean ± SD number of COPD maintenance medication fills was 7.6 ± 6.3 during the follow-up year. On the other hand, the mean ± SD number of fills for SABA and SAMA was 2.7 ± 4.0 and 1.7 ± 3.7, respectively.

Figure 2.

Distribution of study population by COPD medication class on index date among overall patients.

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting β2-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; SABA, short-acting β2-agonist; SAMA, short-acting muscarinic antagonist.

Figure 3.

Mean ± SD number of fills for COPD medications (maintenance and rescue) during the follow-up year among overall patients.

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting β2-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; SABA, short-acting β2-agonist; SAMA, short-acting muscarinic antagonist; SD, standard deviation.

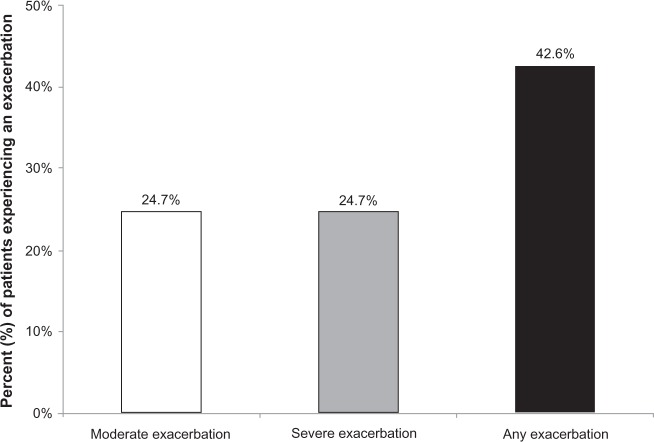

Exacerbation rates

During the follow-up year, 42.6% of the overall study sample had at least one exacerbation (24.7% at least one moderate; 24.7% at least one severe exacerbation) (Figure 4). The mean ± SD annual number of any exacerbation per patient during follow-up was 0.7 ± 1.1 for the overall sample and 1.6 ± 1.0 among patients with at least one exacerbation. About 16% of the study sample had at least two exacerbations (any type) during the follow-up year, with mean ± SD number of exacerbations of 2.6 ± 1.1 per patient (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Exacerbations during the follow-up year among overall patients.

Note: Any exacerbation = either moderate or severe exacerbation.

Table 2.

Annual exacerbation numbers and total costs during the follow-up year*

| Overall sample (n = 17,382) | Patients with at least two exacerbations during the baseline year (n = 1392) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of exacerbations | ||

| Moderate exacerbations | ||

| Patients with at least one exacerbation (%) | 4287 (24.7%) | 614 (44.1%) |

| Exacerbations among patients with at least one exacerbation, mean ± SD | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 1.7 ± 1.0 |

| Exacerbations among all patients, mean ± SD | 0.3 ± 0.7 | 0.8 ± 1.1 |

| Severe exacerbations | ||

| Patients with at least one exacerbation (%) | 4290 (24.7%) | 612 (44.0%) |

| Exacerbations among patients with at least one exacerbation, mean ± SD | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 1.80 ± 1.31 |

| Exacerbations among all patients, mean ± SD | 0.4 ± 0.8 | 0.8 ± 1.3 |

| Any exacerbation (at least one exacerbation) | ||

| Patients with at least one exacerbation | 7402 (42.6%) | 967 (69.5%) |

| Exacerbations among patients with at least one exacerbation, mean ± SD | 1.6 ± 1.0 | 2.2 ± 1.5 |

| Exacerbations among all patients, mean ± SD | 0.7 ± 1.1 | 1.6 ± 1.6 |

| Any exacerbation (at least two exacerbations) | ||

| Patients with at least two exacerbations (%) | 2849 (16.4%) | 572 (41.1%) |

| Exacerbations among patients with at least two exacerbations, mean ± SD | 2.6 ± 1.1 | 3.1 ± 1.4 |

| Exacerbation costs | ||

| Moderate exacerbations | ||

| Patients with at least one exacerbation, mean ± SD | $405 ± $1169 | $518 ± $1525 |

| All patients, mean ± SD | $124 ± $640 | $277 ± $1096 |

| Severe exacerbations | ||

| Patients with at least one exacerbation, mean ± SD | $25,364 ± $43,493 | $29,948 ± $44,601 |

| All patients, mean ± SD | $6260 ± $24,215 | $13,096 ± $33,054 |

| Any exacerbation | ||

| Patients with at least one exacerbation, mean ± SD | $14,991 ± $35,437 | $19,251 ± $38,525 |

| All patients, mean ± SD | $6384 ± $24,283 | $13,373 ± $33,307 |

Notes:

Costs in mid-2011 US dollars, adjusted for inflation using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index in the 12-month follow-up period.

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Among the subgroup of patients with at least two exacerbations during their baseline year (n = 1392), 69.5% had at least one exacerbation (44.1% moderate; 44.0% severe exacerbations) during the follow-up year. The mean ± SD annual number of any exacerbation per patient during follow-up was 1.6 ± 1.6 (0.8 ± 1.1 for moderate; 0.8 ± 1.3 for severe exacerbations). The corresponding mean ± SD number of exacerbations per patient among patients with at least one exacerbation in this subgroup during their follow-up year was 2.2 ± 1.5 (1.7 ± 1.0 for moderate; 1.80 ± 1.31 for severe exacerbations). Moreover, 41.1% of this subgroup had at least two exacerbations (any type) during the follow-up year, with mean ± SD number of exacerbations of 3.1 ± 1.4 per patient (Table 2).

The Poisson regression model (Table 3) showed that the number of exacerbations during the baseline year was the strongest predictor of exacerbation rates during the follow-up year (each additional exacerbation during the baseline year was associated with about 29.6% higher exacerbations during follow-up [RR = 1.2963, P < 0.0001]). Other significant predictors of exacerbations include baseline DCI score (a one unit increase in DCI score was associated with about 4.0% higher exacerbations during follow-up [RR = 1.0402, P < 0.0001]); age (a 10-year increase in age was associated with about a 3.5% increase in exacerbations during follow-up [RR = 1.0035, P < 0.0001]); and residence in the Midwest region was associated with about 15% increase in exacerbations during follow-up (RR = 1.1472, P < 0.0001), while residence in the West region was associated with about 17.5% fewer exacerbations during follow-up (RR = 0.8250, P < 0.0001) than the South region. Also, each additional fixed dose ICS plus LABA inhaler fill during follow-up was associated with about 1.4% fewer exacerbations (RR = 0.9864, P < 0.0001) and each additional ICS was associated with about 2.7% fewer exacerbations (RR = 0.9726, P < 0.0001) during follow-up. On the other hand, each additional SABA fill was associated with about 3.5% increase in exacerbations (RR = 1.0354, P < 0.0001) and each additional SAMA fill was associated with about 2.5% increase in exacerbations during follow-up (RR = 1.0248, P < 0.0001).

Table 3.

Poisson regression results for the number of exacerbations (any type) during the follow-up year (n = 17,382)*

| Covariates | RR | SE | 95% Cl | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.4121 | 0.0240 | 0.3676–0.4620 | <0.0001 |

| US geographic region | ||||

| Midwest | 1.1472 | 0.0260 | 1.0974–1.1993 | <0.0001 |

| Northeast | 0.9710 | 0.0266 | 0.9203–1.0245 | 0.2817 |

| West | 0.8250 | 0.0273 | 0.7732–0.8803 | <0.0001 |

| South (reference) | ||||

| Health plan type | ||||

| HMO | 1.0001 | 0.0230 | 0.9561–1.0462 | 0.9961 |

| Other | 1.0138 | 0.0313 | 0.9543–1.0771 | 0.6564 |

| PPO (reference) | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1.0188 | 0.0187 | 0.9828–1.0561 | 0.3098 |

| Male (reference) | ||||

| Age | 1.0035 | 0.0009 | 1.0017–1.0052 | <0.0001 |

| DCI score | 1.0402 | 0.0053 | 1.0298–1.0507 | <0.0001 |

| Fills for COPD maintenance medications | ||||

| LAMA | 0.9956 | 0.0023 | 0.9912–1.0001 | 0.0561 |

| Fixed-dose ICS + LABA inhaler | 0.9864 | 0.0025 | 0.9815–0.9914 | <0.0001 |

| LABA | 0.9953 | 0.0051 | 0.9853–1.0053 | 0.3526 |

| ICS | 0.9726 | 0.0044 | 0.9639–0.9813 | <0.0001 |

| Fills for COPD rescue medications during the follow-up year | ||||

| SABA | 1.0354 | 0.0019 | 1.0316–1.0392 | <0.0001 |

| SAMA | 1.0248 | 0.0020 | 1.0208–1.0288 | <0.0001 |

| Number of exacerbations during baseline year | 1.2963 | 0.0087 | 1.2794–1.3134 | <0.0001 |

Note:

Poisson distribution with log–link function.

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DCI, Deyo–Charlson Comorbidity Index; HMO, health maintenance organization; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting β2-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; PPO, preferred provider organization; SABA, short-acting β2-agonist; SAMA, short-acting muscarinic antagonist; CI, confidence interval; RR, rate ratio; SE, standard error.

Exacerbation-related costs

The mean ± SD cost per exacerbation among overall patients was $8219 ± $22,644 ($269 ± $748 per moderate; $18,120 ± $31,592 per severe exacerbation) during the follow-up year (Figure 5). Among the overall sample, exacerbations during the follow-up year resulted in mean ± SD total per-patient per-year exacerbation cost of $6384 ± $24,283 ($124 ± $640 for moderate; $6260 ± $24,215 for severe exacerbation). Among patients who experienced at least one exacerbation at follow-up, mean ± SD total exacerbation costs were $14,991 ± $35,437 ($405 ± $1169 for moderate; $25,364 ± $43,493 for severe exacerbation) per patient per year (Table 2).

Figure 5.

Mean ± SD cost per exacerbation during the follow-up year among overall patients.

Notes: Costs are in mid-2011 US dollars, adjusted for inflation using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index; any exacerbation included either moderate or severe exacerbation.

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Among the subgroup of patients with least two exacerbations at baseline, the mean ± SD total exacerbation cost per patient per year was $13,373 ± $33,307 ($277 ± $1096 for moderate; $13,096 ± $33,054 for severe exacerbation). Among patients who had at least one exacerbation at follow-up in this subgroup, the mean ± SD total per-patient per-year exacerbation cost was $19,251 ± $38,525 ($518 ± $1525 for moderate; $29,948 ± $44,601 for severe exacerbation).

In the generalized linear model analysis (Table 4), each additional exacerbation during the baseline year was associated with about 9.1% higher exacerbation costs during the follow-up year (RR = 1.0908, P = 0.0002). Other significant predictors of exacerbation costs were baseline DCI score (a one unit increase in DCI score was associated with about 15.5% higher exacerbations costs during the follow-up year [RR = 1.1555, P < 0.0001]); other health insurance (which was associated with about 32.2% higher exacerbation costs during the follow-up year than preferred provider organization insurance [RR = 1.3216, P < 0.0005]); fixed dose ICS plus LABA fills (each additional fill was associated with about 1.7% fewer exacerbation costs during the follow-up year [RR = 0.9827, P = 0.0221]); and SAMA fills during the follow-up year (each additional fill was associated with about 2.1% higher exacerbation costs during the follow-up year [RR = 1.0214, P < 0.0023]).

Table 4.

Generalized linear model regression results for the cost of exacerbations (any type) during the follow-up year (n = 17,382)*

| Covariates | RR | SE | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 9576.28 | 1474.23 | 7082.02–12,949.00 | <0.0001 |

| US geographic region | ||||

| Midwest | 0.8969 | 0.0522 | 0.8002–1.0053 | 0.0617 |

| Northeast | 0.8584 | 0.0603 | 0.7480–0.9851 | 0.0298 |

| West | 0.9121 | 0.0747 | 0.7769–1.0708 | 0.2610 |

| South (reference) | ||||

| Health plan type | ||||

| HMO | 0.9857 | 0.0588 | 0.8769–1.1081 | 0.8096 |

| Other | 1.3216 | 0.1060 | 1.1293–1.5465 | 0.0005 |

| PPO (reference) | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 0.9703 | 0.0458 | 0.8845–1.0643 | 0.5223 |

| Male (reference) | ||||

| Age | 1.0041 | 0.0023 | 0.9996–1.0087 | 0.0756 |

| DCI | 1.1555 | 0.0168 | 1.1231–1.1889 | <0.0001 |

| Fills for COPD maintenance medications during the follow-up year | ||||

| LAMA | 0.9934 | 0.0067 | 0.9805–1.0066 | 0.3275 |

| Fixed-dose ICS + LABA inhaler | 0.9827 | 0.0075 | 0.9681–0.9975 | 0.0221 |

| LABA | 0.9773 | 0.0137 | 0.9507–1.0046 | 0.1023 |

| ICS | 0.9790 | 0.0133 | 0.9533–1.0054 | 0.1176 |

| Fills for COPD rescue medications during the follow-up year | ||||

| SABA | 0.9948 | 0.0058 | 0.9836–1.0062 | 0.3715 |

| SAMA | 1.0214 | 0.0071 | 1.0076–1.0354 | 0.0023 |

| Number of exacerbations during baseline year | 1.0908 | 0.0252 | 1.0425–1.1415 | 0.0002 |

Note:

Gamma distribution with log–link function.

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DCI, Deyo–Charlson Comorbidity Index; HMO, health maintenance organization; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting β2-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; PPO, preferred provider organization; SABA, short-acting β2-agonist; SAMA, short-acting muscarinic antagonist; CI, confidence interval; RR, rate ratio; SE, standard error.

Discussion

Within this population of relatively well-treated CB patients almost half (42.6%) experienced at least one exacerbation during the follow-up year, and these exacerbations were associated with a high cost, particularly for severe exacerbations which required hospitalization. Moreover, exacerbation rate was even higher (69.5%) during the follow-up year among patients who experienced at least two exacerbations during the baseline year.

The exacerbation rates found in this study (42.6% among overall CB patients) are within the rates found in previous studies, which ranged between 36.0% and 71.0%.15,17,18,20,22 However, moderate exacerbation rates found in this study (24.7%) are lower than the rates found in a previous study, which estimated a moderate exacerbation rate to be 49.6%.15 It should be noted that the current study did not include antibiotic use as a qualifying event for moderate exacerbations, given the controversial effectiveness of antibiotics in the management of COPD exacerbations,23 which could inaccurately inflate moderate exacerbation estimates. Also, similar to other database studies, the current study did not capture mild exacerbations treated with over the counter medications or other moderate or severe exacerbations for which patients did not seek medical care. However, the finding in the current study that the number of prior-year exacerbations predicted annual exacerbation rates and exacerbation-related costs during follow-up was consistent with the literature.24,25 This finding indicates that the effects of preventing a single first exacerbation may also have downstream preventative effects for subsequent exacerbations.

Because few studies have estimated annual exacerbation costs using current study methodology, it is a bit difficult to contextualize the estimated mean ± SD costs per exacerbation results ($269 ± $748 per moderate and $18,120 ± $31,592 per severe exacerbation).

Understanding the actual rate of exacerbations using real-world data can be informative in the discussion of strategies to prevent COPD exacerbations. Although few studies have estimated the rate of COPD exacerbations using real-world data, current evidence is viewed to be mixed.19 The findings of the current study are robust for the following reasons. Firstly, the data used in this study were real-world data derived from a large rich administrative data environment, which is representative of the US commercially insured population. Secondly, this study required patients to be treated with COPD maintenance medications during the follow-up year, and the estimates it generated could be used in program applications that tailor to treated CB patients. Thirdly, this study is less vulnerable to overestimation of exacerbation rates because it assumed a 14-day window per each exacerbation.

This study has some inherent limitations. Firstly, this study focused on treated CB patients and therefore the results might not be generalizable to patients with emphysema (and no CB). Also, the findings are not generalizable to untreated CB populations – it should be noted that evidence shows that a majority of COPD patients are not treated.26 Furthermore, this study used number of fills as a proxy measure of CB treatment and did not include measures of adherence/persistence. Although this study focused on COPD maintenance medications, it did not include phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor medications for the management of COPD – mainly roflumilast, which has been incorporated into the most recent GOLD guidelines and was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration on February 28, 2011 to reduce the risk of COPD exacerbations in patients with severe COPD associated with CB and a history of exacerbations. At the time this study was conducted, an insufficient number of patients in the HIRDSM were prescribed roflumilast to be included in the study analysis. The authors recommend that future studies should include roflumilast-treated patients to assess the real-world rate of COPD exacerbations. Similarly, estimates of exacerbations from this study, particularly for moderate exacerbations might be lower than those from studies that include antibiotics use as a marker of exacerbation. Finally, the authors would like to note the following study limitations inherent to administrative claims databases. Coding accuracy is a potential limitation in this study. Additionally, due to the lack of adequately validated severity measures applicable to administrative claims data, this study only used the number of SABA/SAMA fills during baseline as a proxy to approximate CB severity. Additionally, although CB medication pharmacy fills were used as a proxy of treatment, no data were available on whether patients used their filled medications. The multivariate regression models fitted in this study controlled for specific clinical and demographic covariates, and the results remained consistent; however, other unmeasured patient or physician characteristics could be influencing the specific regression estimates. Finally, this study was limited to claims data analysis and did not include any clinical data to validate study outcomes.

Conclusion

This study found that in real-world practice, CB patients treated with COPD maintenance medications continue to have considerable COPD exacerbations, and these exacerbations (particularly those which require hospitalization) are associated with a high cost. Prior-year exacerbation rate was a significant predictor of both annual exacerbation rates and costs during the follow-up year. These findings highlight the need for new treatment strategies to improve CB management and reduce exacerbations among CB patients. Special attention should be given to patients who experience frequent exacerbations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rebecca Cobb for programming efforts and Cheryl Jones for preparing a first draft of this manuscript. Assistance with preparation of the manuscript for submission by Morgan Hill of Prescott Medical Communications Group (Chicago, Illinois) was made possible by funding from Forest Research Institute.

Footnotes

Disclosure

This research project was funded by Forest Research Institute. AA and HT are employees of HealthCore, Inc, an independent outcomes research organization. SXS is an employee of Forest Research Institute. CTS is an employee of Pharmerit, LLC, an independent outcomes research organization. The other authors (AA, HT, CTS) report no conflicts of interest in this work. The funding sponsor had no role in acquisition or analysis of data. Parts of these data were presented as a poster at the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research 17th Annual Meeting; 2012 June 2–6; Washington, DC, USA.

References

- 1.Minino AM, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD.Deaths: Preliminary Data for 2008 Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr59/nvsr59_02.pdfAccessed January 17, 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD.Deaths: Preliminary Data for 2010 Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr60/nvsr60_04.pdfAccessed January 17, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Heart Lung, and Blood Institute Morbidity and Mortality: 2009 Chart Book on Cardiovascular, Lung, and Blood Diseases Bethesda, MD: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 2009Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/docs/2009_ChartBook.pdfAccessed January 17, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osborne ML, Vollmer WM, Buist AS. Periodicity of asthma, emphysema, and chronic bronchitis in a northwest health maintenance organization. Chest. 1996;110(6):1458–1462. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.6.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez-Roisin R. Toward a consensus definition for COPD exacerbations. Chest. 2000;117(5 Suppl 2):398S–401S. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5_suppl_2.398s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burge S, Wedzicha JA. COPD exacerbations: definitions and classifications. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2003;41:46s–53s. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00078002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White AJ, Gompertz S, Stockley RA. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 6: the aetiology of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2003;58(1):73–80. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agusti AG, et al. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, GOLD Executive Summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012 Aug 9; doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0596PP. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donaldson GC, Wedzicha JA. COPD exacerbations. 1: epidemiology. Thorax. 2006;61(2):164–168. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.041806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Celli BR, MacNee W, ATS/ERS Task Force Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(6):932–946. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00014304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seemungal TA, Donaldson GC, Bhowmik A, Jeffries DJ, Wedzicha JA. Time course and recovery of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(5):1608–1613. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9908022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donaldson GC, Seemungal TA, Bhowmik A, Wedzicha JA. Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2002;57(10):847–852. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.10.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD [webpage on the Internet] Bethesda, MD: Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; 2011Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/guidelines-global-strategy-for-diagnosis-management.htmlAccessed November 13, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seemungal TA, Hurst JR, Wedzicha JA. Exacerbation rate, health status and mortality in COPD – a review of potential interventions. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2009;4:203–223. doi: 10.2147/copd.s3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blias L, Forget A, Ramachandran S. Relative effectiveness of budesonide/formoterol and fluticasone propionate/salmeterol in a 1-year, population-based, matched cohort study of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): effect on COPD-related exacerbations, emergency department visits and hospitalizations, medication utilization, and treatment adherence. Clin Ther. 2010;32(7):1320–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mapel DW, Schum M, Lydick E, Marton JP. A new method for examining the cost savings of reducing COPD exacerbations. Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28(9):733–749. doi: 10.2165/11535600-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu AP, Yang H, Wu EQ, Setyawan J, Mocarski M, Blum S. Incremental third-party costs associated with COPD exacerbations: a retrospective claims analysis. J Med Econ. 2011;14(3):315–323. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2011.576295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pauwels R, Calverley P, Buist AS, et al. COPD exacerbations: the importance of a standard definition. Respir Med. 2004;98(2):99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mapel DW, Dutro MP, Marton JP, Woodruff K, Make B. Identifying and characterizing COPD patients in US managed care. A retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of administrative claims data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:43. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Measuring price change for medical care in the CPI [webpage on the Internet] Washington, DC: US Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2012[updated February 12, 2012]. Available from: http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpifact4.htmAccessed November 13, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akazawa M, Stearns SC, Biddle AK. Assessing treatment effects of inhaled corticosteroids on medical expenses and exacerbations among COPD patients: longitudinal analysis of managed care claims. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(6):2164–2182. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00879.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wedzicha JA. Antibiotics at COPD exacerbations: the debate continues. Thorax. 2008;63(11):940–942. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.103416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seemungal TA, Donaldson GC, Paul EA, Bestall JC, Jeffries DJ, Wedzicha JA. Effect of exacerbation on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(5 Pt 1):1418–1422. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.5.9709032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, et al. ECLIPSE Investigators Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(12):1128–1138. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Make B, Dutro MP, Paulose-Ram R, Marton JP, Mapel DW. Undertreatment of COPD: a retrospective analysis of US managed care and Medicare patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:1–9. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S27032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]