Abstract

This study aimed to expand the current understanding of smoking maintenance mechanisms by examining how putative relapse risk factors relate to a single behavioral smoking choice using a novel laboratory smoking-choice task. After 12 hours of nicotine deprivation, participants were exposed to smoking cues and given the choice between smoking up to two cigarettes in a 15-minute window or waiting and receiving four cigarettes after a delay of 45 minutes. Greater nicotine dependence, higher impulsivity, and lower distress tolerance were hypothesized to predict earlier and more intensive smoking. Out of 35 participants (n=9 female), 26 chose to smoke with a median time to a first puff of 1.22 minutes (standard deviation=2.62 min, range=0.03–10.62 min). Survival analyses examined latency to first puff, and results indicated that greater pre-task craving and smoking more cigarettes per day were significantly related to smoking sooner in the task. Greater behavioral disinhibition predicted shorter smoking latency in the first two minutes of the task, but not at a delay of more than two minutes. Lower distress tolerance (reporting greater regulation efforts to alleviate distress) was related to more puffs smoked and greater nicotine dependence was related to more time spent smoking in the task. This novel laboratory smoking-choice paradigm may be a useful laboratory analog for the choices smokers make during cessation attempts and may help identify factors that influence smoking lapses.

Keywords: smoking, relapse, nicotine dependence, craving

Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable death and imposes a large public health burden, yet an estimated 46.6 million U.S. adults continue to smoke cigarettes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011). Although an estimated 45.3% (20.8 million) of current cigarette smokers attempt to quit for one day or more in any given year (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008), fewer than 5% of smokers who quit for 24 hours are still smoke-free three months or one year post-quit (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2002; Fiore et al., 2008). In order to improve smoking cessation rates, it is important to identify factors that drive returns to smoking and develop treatments targeting these key risk factors.

The current study examined the validity of a novel laboratory smoking choice task and assessed the contributions of putative risk factors for relapse on a real-time decision about smoking in this new task. Relapses to smoking likely begin with a single choice or smoking incident. This study attempts to model such choices under controlled laboratory conditions. Previous research has demonstrated that exposure to cues associated with cigarettes and smoking can elicit strong urges to smoke and other markers of smoking motivation, such as increased negative mood, withdrawal symptoms, heart rate, and skin conductance (Bailey, Goedeker, & Tiffany, 2010; Carter & Tiffany, 1999; Niaura et al., 1999; Payne, Smith, Adams, & Diefenbach, 2006).

There are many limitations to these extant laboratory-based cue-reactivity paradigms, however. The degree to which intermediate outcomes, such as urges to smoke, can effectively stand in for behavioral smoking responses is not clear. Cue-reactivity outcome measures, such as craving, are inconsistently related to an individual’s likelihood of relapse (e.g., Niaura et al., 1999; Payne et al., 2006) and reported smoking heaviness for the day or week following cue exposure (e.g., Carpenter et al., 2009). In addition, many studies do not simultaneously pair the stimulus cue with the opportunity to smoke (e.g., Carpenter et al., 2009; Droungas, Ehrman, Childress, O’Brien, 1995), so it is difficult to determine how reactivity to the stimulus might relate to later smoking behavior. Lastly, although a few studies incorporated the opportunity to smoke in the presence of the stimulus (e.g., Bailey et al., 2010), participants in these studies could only smoke when instructed. Because this smoking behavior is not self-directed, it likely does not model smoking choices well. In order to effectively do this (i.e., in a way that is likely to predict important clinical outcomes of smoking cessation attempts), the laboratory paradigm should include a self-directed behavioral smoking choice.

This study may expand the current understanding of smoking maintenance mechanisms by examining a new laboratory model of smoking behavior and evaluating how the putative risk factors of nicotine dependence, impulsivity, and low distress tolerance relate to a smoking choice. To succeed in quitting smoking, a smoker must decide to forgo the immediate gratification of smoking to achieve the long-term benefits associated with abstinence. This study models real smoking decisions in a laboratory-based choice between an immediate smoking opportunity and a larger, delayed reward. The utility of a single laboratory choice paradigm in predicting behavior over time has been well-established. Specifically, an individual’s inability to delay immediate gratification to obtain a larger reward later has been shown to predict important behavioral outcomes, such as later substance abuse (Wulfert, Block, Santa Ana, Rodriguez, & Colsman, 2002) and impaired academic performance and social functioning over a decade later (e.g., Mischel, Shoda, & Peake, 1988; Mischel, Shoda, & Rodriguez, 1989). Likewise, a single choice to delay immediate gratification from smoking might relate to broader behavioral outcomes such as smoking maintenance and cessation outcomes. Smoking behavior in a laboratory model that serves as a proxy for real smoking decisions should also relate to known risk factors for relapse. Dimensions of nicotine dependence, impulsivity, and distress tolerance that increase the likelihood of relapse might also relate to a smoker’s inability to delay gratification in this paradigm.

Nicotine dependence is a latent variable that is thought to drive smoking behavior, including smoking heaviness and smoking persistence (Bolt et al., 2009). Those high in nicotine dependence should be those who are most likely to smoke under conditions designed to elicit strong smoking motivation, such as during a period of nicotine deprivation. Individuals with higher levels of nicotine dependence may smoke more frequently to allay withdrawal or cravings, and, over time, this behavior may become more automatic. Consequently, greater nicotine dependence might predict an individual’s inability to refrain from smoking, particularly when experiencing withdrawal or craving. Individuals who report smoking more automatically, or report that smoking eases their distress, smoke more cigarettes per day and are at a greater risk for relapse than are other smokers (Piper et al., 2004, 2008b). Given this, greater nicotine dependence should predict decreased ability to refrain from smoking in a choice paradigm that induces smoking motivation.

Impulsivity is another variable likely to influence smoking choices in the lab and during cessation attempts. Smokers who are impulsive are likely to have particular difficulty engaging in the kind of self-regulation needed to refrain from smoking in the face of temptation, even when they are motivated to abstain. Individuals with high levels of impulsivity may be more reactive and have greater difficulty inhibiting their behavior in the presence of a rewarding stimulus compared to individuals with lower levels of impulsivity (Finn, 2002; Newman, 1987). In line with this theory, research has demonstrated that people who are more impulsive tend to smoke (Baker, Johnson, & Bickel, 2003; Mitchell, 1999), smoke more (Spinella, 2002), report greater craving when nicotine-deprived (VanderVeen, Cohen, Cukrowicz, & Trotter, 2008), and return to smoking more quickly after abstinence (Bickel, Odum, & Madden, 1999; Dallery & Raiff, 2007) than do people who are less impulsive.

Individuals who are more impulsive may act more quickly on immediate opportunities to smoke than would others, and this presents a particular vulnerability during cessation attempts because smokers must exert cognitive control to refrain from smoking when presented with smoking-related stimuli or experiencing cravings. Research has demonstrated that highly impulsive individuals engage in even more impulsive decision-making when deprived than when they are not deprived (Field, Santarcangelo, Sumnall, Goudie, & Cole, 2006; Mitchell, 2004). Specifically, smokers were more likely to choose smaller immediate gains over future delayed rewards when nicotine-deprived than after smoking (Mitchell, 2004; Field et al., 2006). Impulsivity predicts heightened craving and cessation failure (Doran, Spring, McChargue, Pergadia, & Richmond, 2004; Vanderveen et al., 2008), but to our knowledge, there is no available research examining the relation between this putative risk factor and an actual smoking choice.

According to the reformulated negative reinforcement model of drug motivation, reduction of negative affect is another powerful motive to smoke (Baker, Piper, McCarthy, Majeskie, & Fiore, 2004). Smokers who are less able to tolerate the negative internal states of withdrawal, such as craving or negative affect, will likely have a more difficult time refraining from smoking, even when they are motivated to abstain. Evidence suggests that smokers differentially experience and respond to this subjective withdrawal distress (e.g., Brown et al., 2009; Brown, Lejuez, Kahler, & Strong, 2002). Smokers with low distress tolerance (i.e., a decreased ability to persist towards a goal when experiencing affective, physical, or psychological distress) should be more sensitive and reactive to withdrawal and more likely to try to avoid this by smoking. Failure to inhibit this avoidance behavior may be a central process underlying substance use maintenance (Richards, Daughters, Bornovalova, Brown, & Lejuez, 2010). Therefore, a smoker’s perceived or actual ability to withstand aversive internal states is an important influence on smoking behavior (Leyro, Zvolensky, & Bernstein, 2010).

In support of this notion, research has shown that smokers with lower distress tolerance achieve shorter durations of abstinence (Brandon et al., 2003; Brown et al., 2002) and experience greater craving and increased lapse risk during a quit attempt (Abrantes et al., 2008; Brown et al., 2009), compared to those with greater distress tolerance. Furthermore, research suggests that distress tolerance is significantly lower for smokers when they were nicotine-deprived than when non-deprived (Bernstein, Trafton, Ilgen, & Zvolensky, 2008). Distress is likely to be especially motivating in the context of deprivation and therefore one’s perceived ability to tolerate distress is likely to be predictive of continued smoking behavior. Consequently, low distress tolerance should also relate to behavioral outcomes of a laboratory smoking-choice model if it is a valid proxy of real-world smoking decisions.

The aim of this study was to develop a valid paradigm for studying smoking choices that could be used in future, prospective studies of smokers trying to quit. We hypothesized that higher levels of nicotine dependence, greater impulsivity, and lower distress tolerance would predict smoking in the presence of a salient smoking cue and an immediate opportunity to smoke. Examining how these risk factors predict a single smoking choice may improve our understanding of smoking maintenance mechanisms and help identify targets for intervention.

Method

Participants

Participants were adult volunteers (N=35, n=9 women) recruited from mass media outlets in central New Jersey. To be eligible for the study, participants had to be at least 18 years of age, able to read and write English, and report smoking at least 10 cigarettes per day for at least 6 months. Potential participants were excluded on the basis of heart disease; severe or worsening angina; heart attack or heart surgery in the past three months; diagnosis or treatment of schizophrenia, psychosis, or bipolar disorder; plans to quit smoking in the next two months; current use of smoking cessation treatments; or being pregnant or breastfeeding. Participants also had to be willing and able to refrain from smoking for 12 hours before the study visit.

Procedure

All study procedures were approved by an Institutional Review Board. Interested volunteers were screened for eligibility over the telephone. Eligible participants scheduled an office visit and were instructed to refrain from smoking for 12 hours prior to the visit. At the visit, researchers described the study in detail and obtained written informed consent from participants. Research staff verified adherence to the deprivation manipulation by measuring reported time since the last cigarette and obtaining two samples of expired breath level of carbon monoxide (CO), a biochemical marker of smoke exposure. A mean expired breath CO level below 10 parts per million (ppm) verified at least 12 hours of abstinence for a daily smoker (Javors, Hatch, & Lamb, 2004). Participant compensation for stopping smoking for 12 hours was pro-rated based on CO level, such that participants received the full $30 bonus if their CO level was below 10 ppm, half the bonus ($15) if their CO level was 11–20 ppm, and none of the bonus ($0) if their CO level was above 20 ppm. Participants received $20 for the two-hour study visit and had the chance to earn up to $27.20 in bonus money based on performance on computer tasks. Participants who did not qualify were advised to quit, referred to smoking cessation resources in the area, and thanked for their time. Participants who were eligible for the experiment completed the measures described below. Additional measures administered that were not included in the subsequent analyses included: self-report assessments of positive and negative affect (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1998), expectancies for negative affect relief from smoking (modified subscale of the Smoking Consequences Questionnaire; SCQ; Copeland, Brandon, & Quinn, 1995), and feelings and beliefs about one’s last failed quit attempt; as well as an exploratory measure of impulsive choice.

Pre-Smoking Choice Task Measures

Brief Questionnaire of Smoking Urges

(QSU; Tiffany & Drobes, 1991). Craving was assessed using the 10-item version of the Questionnaire of Smoking Urges. Items are rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) where higher scores indicate greater craving. Sample items include “I have a desire for a cigarette right now,” “If it were possible, I would probably smoke now,” and “I could control things better right now if I could smoke.” Research supports an overall latent structure of general craving with two lower-order factors of strong desire/intention to smoke and anticipation of relief from negative affect (Cox, Tiffany, & Christen, 2001). The full 10-item version has shown high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas=.87–.89) across different populations of smokers (Cox et al., 2001).

Distress Tolerance Scale

(DTS; Simons & Gaher, 2005). This 15-item questionnaire measures the degree to which individuals believe the experience of negative affect is unbearable. Previous research supports a multidimensional structure consisting of a total score of distress tolerance and four subscales: willingness to tolerate emotional distress, subjective appraisal of distress, attention being absorbed by negative emotions, and regulation efforts to alleviate distress (Leyro et al., 2010). Items are rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). Total scores range from 15–75 with higher scores indicating greater distress tolerance (i.e., less reactivity to distress). The DTS shows good internal consistency (DTS total Cronbach’s alpha=.91, subscale alphas=.66–.83) and validity in cigarette smokers (Leyro et al., 2010).

Breath-Holding Challenge

This is a widely used and easily assessed behavioral correlate of distress tolerance (e.g., Brown et al., 2002; MacPherson, Stipelman, Duplinsky, Brown, & Lejuez, 2008). During this task, participants are instructed to take a deep breath and hold it for as long as they can. They are asked to raise their hand to notify the experimenter when they begin to feel uncomfortable. The participants are instructed to continue holding their breath beyond the point of initial discomfort for as long as possible. Distress tolerance is measured as the latency in seconds between the point at which the participant begins to feel uncomfortable and the point at which they exhale. Due to non-normality in the distribution of distressed breath holding duration that was not correctible via transformation, this variable was re-coded as binary using a median split (less than or equal to 6.5 seconds=0, greater than 6.5 seconds=1).

Delay Discounting

Delay discounting is the tendency to view rewards available at a later time as less valuable than those available sooner. This is a well-validated measure of impulsive decision-making and the rate of discounting delayed rewards has been predictive of smoking behavior in other studies (e.g., Dallery & Raiff, 2007). This is a measure of choice that parallels the smoking-choice task in important ways, but with monetary rewards. In this computer-based delay discounting task, participants were presented with a series of choices between a smaller monetary reward available immediately and a large amount available later (e.g., $10 today vs. $20 in one week). Up to 300 questions were administered to assess discounting of rewards of $20, $100, and $2500 at delays of 7, 30, and 180 days. Each series of delay discounting questions began with a randomly selected smaller, immediate reward in 2% increments of the larger, delayed reward (i.e., in multiples of $2 when the delayed reward was $100). The subsequent values of the smaller, immediate rewards in each series were calculated according to the algorithm described by Johnson and Bickel (2002). Briefly, each choice selected by the participant reset boundary levels representing the lower and upper limits of the participant’s indifference point, the amount of money to be received immediately that was preferred equally to the delayed amount. The questions in the series continued (up to 50 individual items) until the difference between the outer upper and lower limits was within 2% of the magnitude of the delayed reward (i.e., the questions ended for a $100 series when the upper and lower limits of the participant’s indifference point differed by only $2).

Participants’ delay discounting rates were calculated using the formula: k=(1/D)[(Vd/Vp)-1], where k reflects the rate at which delayed rewards are devalued for each day of delay, D is the delay in days, Vd is the value of the delayed reward in dollars, and Vp is the value of the immediately available, smaller reward in dollars (Johnson & Bickel, 2002). To enhance motivation and attention to the choices, participants were informed at the beginning of the task that one of their choices would be treated as real and they would receive the monetary reward at the delay specified. One choice was randomly selected as a bonus payment for each participant (up to $20).

Modified Conners’ Continuous Performance Task-II

(CPT-II: Conners, 2004; Conners, 1985). This is a computerized task designed to measure sustained attention and the ability to inhibit prepotent responses. In this task, the participant was instructed to press a key every time a letter appeared on a computer screen, except when the letter was an “X”. On each trial, a single letter was presented in the center of the screen for 250 ms, followed by a variable inter-trial interval of 1, 2, or 4 seconds. The version of the task administered in this study differed from the Conners’ CPT-II in that trials with varying inter-trial intervals were interspersed rather than blocked. To enhance participant motivation and effort on the task, participants were provided with feedback about their responses (in terms of accuracy) and were paid a bonus of up to $7.20 according to their performance ($0.02 per correct response on each of 360 trials). Responses were screened for inattention, whereby participant data was excluded when omission errors were greater than 5% in any block (7.6% of 210 blocks were excluded for this reason). Percent of commission errors and mean reaction time served as behavioral measures of disinhibition. This task has been well-validated as a measure of impulsivity and has been related to smoking cessation success (e.g., Krishnan-Sarin et al., 2007). The order of the Delay Discounting and CPT-II tasks was counterbalanced across participants.

Smoking Choice Task

The investigator brought two cigarettes from the participant’s preferred brand (assessed at screening), an ashtray, and a lighter into the smoking chamber. A poster of someone smoking was displayed in the chamber to serve as an additional smoking cue. The participants received the following instructions:

For part of this project, we want to understand what triggers the urge to smoke. We will now expose you to smoking cues and triggers. This is meant to be a situation where you feel the urge to smoke, and we want to see how long it takes until the urge to smoke overwhelms you. For this task, we will give you two cigarettes now. We want you to light this first cigarette as you normally would and hold it in the hand you normally smoke with. We will ask you to hold this lit cigarette until the urge to smoke overwhelms you. Wait as long as you can before you smoke, but when you feel the urge is overwhelming, then you may smoke as you normally would. We are going to ask you to sit here quietly, and we will be outside monitoring your safety. Again, the room is specially ventilated to allow smoking indoors. The smoke will escape directly through this vent to the outside of the building. You can smoke one or both cigarettes in the next 15 minutes. If you do not smoke during this period, we will give you 4 cigarettes to take with you at the end of the session, which will be in 45 minutes.

Subjects were instructed not to use cell phones or other distractions during this task. The investigator left the room and observed the participant using a webcam that recorded the participant’s behavior. After 15 minutes passed, the investigator returned to the room and removed the cigarettes and ashtray. Participants who did not smoke received the delayed reward at the end of the session 45 minutes later. The ratio of 2 cigarettes now versus 4 cigarettes later was selected because we found that larger delayed incentives limited the observed variance in our primary outcome measure of smoking latency. This ratio also closely mirrors the 1:2 ratio of immediate and delayed rewards in the classic Mischel delay of gratification paradigm (e.g., Mischel, Ebbesen, & Zeiss, 1972). Smoking behavior during the smoking choice task was coded by latency to a first puff, total number of puffs taken during the 15-minute smoking period, and duration of time spent smoking in the task. Two independent, trained coders rated videos of smoking behavior to assess each of these targets. Disagreements between raters were adjudicated by a third rater. Smoking latency was the primary outcome of interest because it most closely captures the ability to delay gratification. Smoking topography machines were not used because the smoking choice task was designed to preserve the validity of smoking behavior. Based on previous research, latency to smoke can be used as an index of drug-seeking behavior or smoking cue incentive salience (Berridge, 2007; Carter & Tiffany, 2001).

Post-Smoking Choice Task Measures

Smoking Choice Reactions

Immediately after the smoking choice task, participants completed a questionnaire assessing reasons for choosing to smoke or abstain and methods used to deal with urges to smoke during the task (i.e., “distracted myself”). The QSU-brief was then administered a second time, and change in urge intensity from pre- to post-task was calculated as a smoking outcome variable.

Smoking History Questionnaire (SHQ)

Smoking history and current use patterns were assessed using a 20-item questionnaire. The SHQ has been successfully used in previous studies as a measure of smoking history (Brown et al., 2002; Zvolensky, Lejuez, Kahler, & Brown, 2004). Duration of past abstinence and number of past quit attempts were examined as predictors of smoking latency in the lab task. The categorical variable of duration of longest past abstinence was re-coded using a median split (less than or equal to 2 weeks=0, greater than 2 weeks=1).

Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives

(WISDM-68: Piper et al., 2004). This is a 68-item self-report measure designed to assess nicotine dependence motives on 13 dimensions. Items are rated on a 7-point scale anchored at 1 (Not at all true of me) and 7 (Extremely true of me), with higher scores indicating greater nicotine dependence. Each subscale has shown high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas >.87) (Piper et al., 2004). Based on previous research, a total nicotine dependence score was calculated by averaging scores on the four primary subscales of the WISDM (automaticity, loss of control, craving, tolerance) (Piper et al., 2008a). This measure has shown positive relations with smoking variables including cigarettes smoked per day, CO level, and likelihood of relapse at the end of treatment (Piper et al. 2004; Piper et al. 2008b).

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11

(BIS-11: Patton, Stanford, & Barratt, 1995). This is a 30-item self-report questionnaire designed to assess behavioral impulsivity. Items are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (rarely/never) to 4 (almost always/always). Total scores on the BIS-11 range from 30 to 120 with scores over 72 indicating high impulsiveness (Stanford et al., 2009). The scale has shown good internal consistency (total scale Cronbach’s alpha=.83, subscale alphas=.59–.74) and good test-retest reliability (total scale Spearman’s rho=.83, subscales .61–.72) (Stanford et al., 2009). In previous studies, higher scores have been related to smoking behavior and earlier relapse (Doran et al., 2004; Mitchell, 1999).

The Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence

(FTND; Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerström, 1991). The FTND is a continuous measure of physical nicotine dependence. Items include questions such as “How soon after you wake up do you smoke?” Cumulative scores on the six-item questionnaire range from zero to 10, with higher scores indicating greater levels of nicotine dependence. The FTND has shown fair internal consistency (alpha =.61) (Heatherton et al., 1991), positive relations with smoking variables (e.g., salivary cotinine levels and withdrawal severity), and high degrees of test-retest reliability (Payne, Smith, McCracken, McSherry & Antony, 1994; Pomerleau, Carton, Lutzke, Flessland & Pomerleau, 1994).

Demographics

A brief demographic questionnaire was administered to characterize the sample in terms of age, sex, ethnicity, race, marital status, level of education, employment status, and household income.

Data Analysis

Discrete-time survival methods were used to analyze how the variation in risk of smoking over time was related to nicotine dependence, impulsivity, distress tolerance, and smoking history variables, while controlling for baseline number of cigarettes smoked per day and demographic variables, such as gender. Those who did not smoke during the observation period were censored and their survival time was set to the end of the data collection window (Curry, Marlatt, Peterson, & Lutton, 1988). Event status was coded as 1=smoked prior to termination time or 0=still abstinent at termination time. A predictor was retained in the model if it improved the overall goodness-of-fit of the model. The effects of the continuous predictors were displayed by plotting survival functions using Kaplan-Meier graphs and estimating the median lifetime, the time at which half the sample had experienced the event (puffing) and half had not (Willett & Singer, 1993).

In addition, the proportionality assumption was tested by including statistical interactions between the predictors of interest and time in the hazard model and then visually examining the Kaplan-Meier graphs (Willett & Singer, 1993). When a proportionality violation was detected (i.e., a predictor had a more pronounced effect on the risk ratio at a specific point in time compared to other points in time), the time interval was split to more accurately analyze the effect of the predictor on the risk ratio during specific epochs.

Lastly, multivariate linear regression models were used to analyze the relations between putative risk factors and continuous smoking outcome variables (e.g., number of puffs, total time spent smoking) while controlling for number of cigarettes per day and demographic variables. Non-significant predictors were eliminated from all models.

Results

Table 1 presents a summary of sample characteristics. Among the 35 study participants, 26 participants smoked during the task (n=8 female), while 9 participants abstained (n=1 female) and received the later reward. Hours of nicotine deprivation prior to the task did not differ significantly between those who smoked (M=13.80, SD=1.56) and those who waited in the choice task (M=15.38, SD=3.61), t(9.05)=1.27, p=.235, Cohen’s d=−.74.

Table 1.

Demographics for the Final Sample of Participants (N=35)

| Variable | n | % | ||

| Female participants | 9 | 25.7% | ||

| Hispanic (n=34) | 2 | 5.7% | ||

| Race | ||||

| White | 25 | 71.4% | ||

| African American | 7 | 20.0% | ||

| American Indian or Native American | 1 | 2.9% | ||

| Other | 2 | 5.7% | ||

| Education | ||||

| 0–11 grades completed | 1 | 2.9% | ||

| Grade 12 or GED | 17 | 48.6% | ||

| College 1–3 years | 14 | 40.0% | ||

| College 4 or more years | 3 | 8.6% | ||

| Employment | ||||

| Employed for wages | 15 | 42.9% | ||

| Self-employed | 3 | 8.6% | ||

| Unemployed less than 1 year | 4 | 11.8% | ||

| Unemployed more than 1 year | 6 | 17.6% | ||

| Homemaker | 1 | 2.9% | ||

| Student | 8 | 23.5% | ||

| Retired | 3 | 8.8% | ||

| Disabled | 4 | 11.8% | ||

| Variable | n | % | ||

| Income | ||||

| Less than $10,000 | 9 | 25.7% | ||

| $10,000–$19,999 | 9 | 25.7% | ||

| $20,000–$24,999 | 2 | 5.7% | ||

| $25,000–$34,999 | 4 | 11.4% | ||

| $35,000–$49,999 | 3 | 8.6% | ||

| $50,000–74,999 | 4 | 11.4% | ||

| $75,000 or more | 4 | 11.4% | ||

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 3 | 8.6% | ||

| Divorced | 2 | 5.7% | ||

| Widowed | 3 | 8.6% | ||

| Separated | 1 | 2.9% | ||

| Never married | 19 | 54.3% | ||

| Not married but living with partner | 7 | 20.0% | ||

| M | SD | Min | Max | |

| Age | 36.31 | 15.15 | 18 | 68 |

| Cigarettes per day | 17.14 | 6.80 | 10 | 30 |

| No. of years smoked | 18.80 | 13.83 | 2 | 52 |

| No. of past quit attempts | 3.06 | 2.46 | 0 | 10 |

| FTND total | 4.06 | 2.02 | 0 | 8 |

| Hours since last cig | 14.21 | 2.31 | 12 | 23 |

| Expired CO reading (ppm) | 6.60 | 2.78 | 0 | 14 |

Descriptive statistics regarding the candidate predictors of smoking behavior are shown in Table 2. Of those who smoked in the task, median time to a first puff was 1.22 minutes (SE=2.62min, range=0.03–10.62min), the number of total puffs varied from 6 to 49 (M =17.96, SD=11.19), and total time spent smoking ranged from 3.05 to 10.87 minutes (M=6.33, SD=1.87). Participants who chose to smoke in the task had significantly higher pre-task craving, t(33)=2.84, p=.008, Cohen’s d=1.12), and smoked more cigarettes per day on average (M=18.58, SD=6.42) than those who waited for the delayed reward (M=13.00, SD=6.48), t(33)=2.24, p=.032, Cohen’s d=0.89). Using a liberal alpha level for this exploratory work, the results also indicated that those who smoked in the task reported greater need to regulate distress (lower tolerance for distress), t(32.978)=1.80, p=.081, Cohen’s d=−0.43, compared to those who abstained.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Putative Smoking Vulnerability Factors, by Smoking Choice

| Variable | Smoked (n=26) Mean (SD) |

Abstained (n=9) Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Task Craving | 48.50 (13.36)* | 33.33 (15.22) |

| Nicotine Dependence | ||

| WISDM primary dependence score | 4.46 (1.18) | 3.72 (1.10) |

| Impulsivity | ||

| Delay Discounting rate (k) | 0.52 (1.00) | 0.50 (1.00) |

| BIS total score | 64.08 (10.21) | 68.22 (7.71) |

| CPT percent commission errors | 3.23 (2.06) | 2.84 (1.94) |

| CPT correct trial reaction time (msec) | 441.40 (70.72) | 432.30 (53.58) |

| Distress Tolerance | ||

| DTS total score | 54.35 (10.91) | 57.89 (7.99) |

| DTS tolerance subscale | 10.77 (3.36) | 12.00 (1.32) |

| DTS appraisal subscale | 22.50 (3.80) | 23.33 (3.50) |

| DTS absorption subscale | 11.08 (2.78) | 11.22 (2.68) |

| DTS regulation subscale | 10.00 (3.26)+ | 11.33 (1.12) |

| Distressed breath holding duration (sec) | 13.62 (14.90) | 20.97 (20.52) |

p<.10.

p<.05

Gender differences in the candidate predictors of smoking behavior were examined. Given the limited power in these analyses, effect size estimates of gender differences are reported only for effects that were small or greater by conventional standards (Cohen, 1992). On average, men reported lower pre-task craving (M=42.88, SD=15.64) compared to women (M=49.56, SD=13.42, Cohen’s d=−0.45). On measures of distress tolerance, men had lower self-reported distress tolerance (M=54.50, SD=10.60) compared to women (M=57.44, SD=9.38, Cohen’s d=−0.29) but higher physical distress tolerance as measured by breath-holding duration (men, M=16.85 seconds, SD=16.02; women, M=11.64, SD=18.31, Cohen’s d=0.32). On measures of impulsivity, men had lower discounting rates (discounted delayed rewards less steeply) (M=.44, SD=.88) compared to women (M=.74, SD=1.28, Cohen’s d=−0.31).

Descriptive statistics regarding the reported reasons for smoking or abstaining in the task are shown in Table 3. The most commonly selected reasons for choosing to smoke in the task included strong urges/craving to smoke, being bored, and wanting to smoke as much as possible before someday quitting. Smokers who chose to abstain in the task frequently indicated that cigarettes are expensive and free cigarettes would help or that they wanted to challenge themselves in the task.

Table 3.

Reported Reasons for Smoking or Abstaining in the Choice Task

| Variable | Smoked (n=26) N (%) |

Abstained (n=9) N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Urge to smoke was strong | 21 (80.8 %) | 0 |

| Bored | 6 (23.1%) | 0 |

| Smoke as much as possible before quitting | 5 (19.2%) | 0 |

| Cigs are expensive/free cigs would help | 3 (11.5%) | 4 (44.4%) |

| Wanted to challenge myself | 2 (7.7%) | 5 (55.6%) |

| No urge/craving | 2 (7.7%) | 0 |

| Did not need cigs | 0 | 2 (22.2%) |

| Felt pressured/embarrassed | 0 | 0 |

Latency to First Puff (N=35)

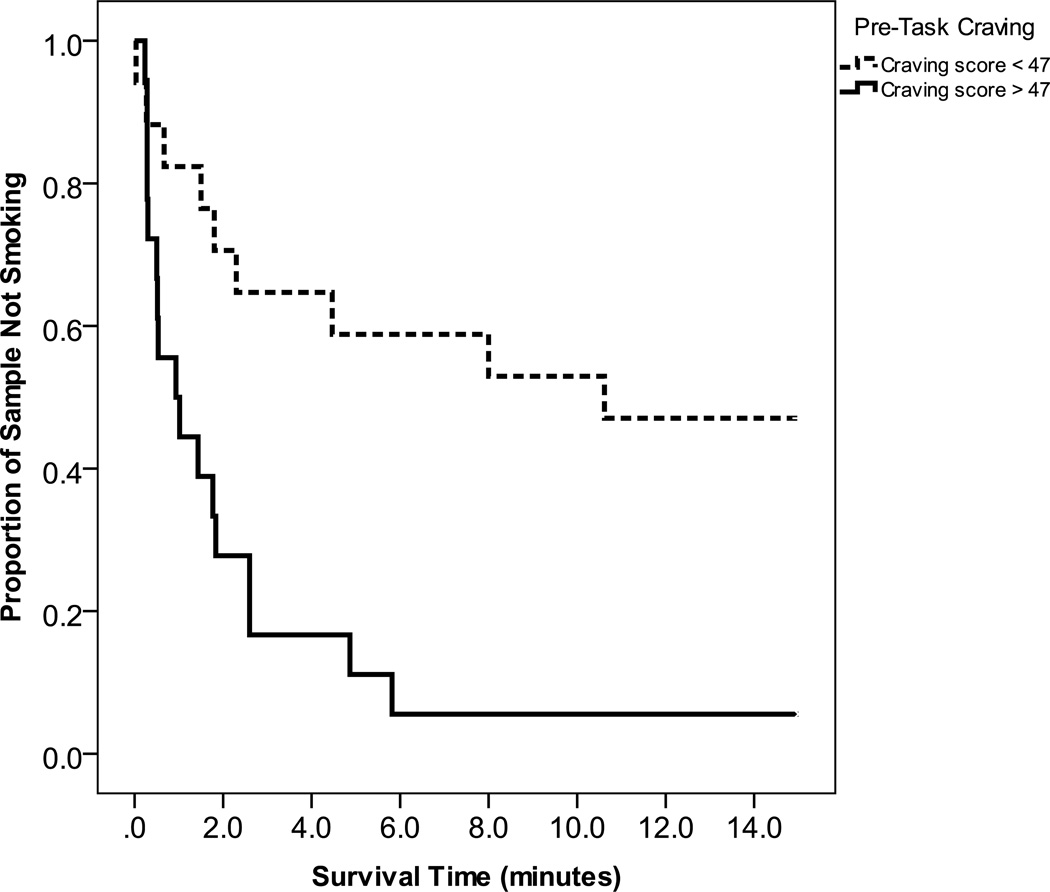

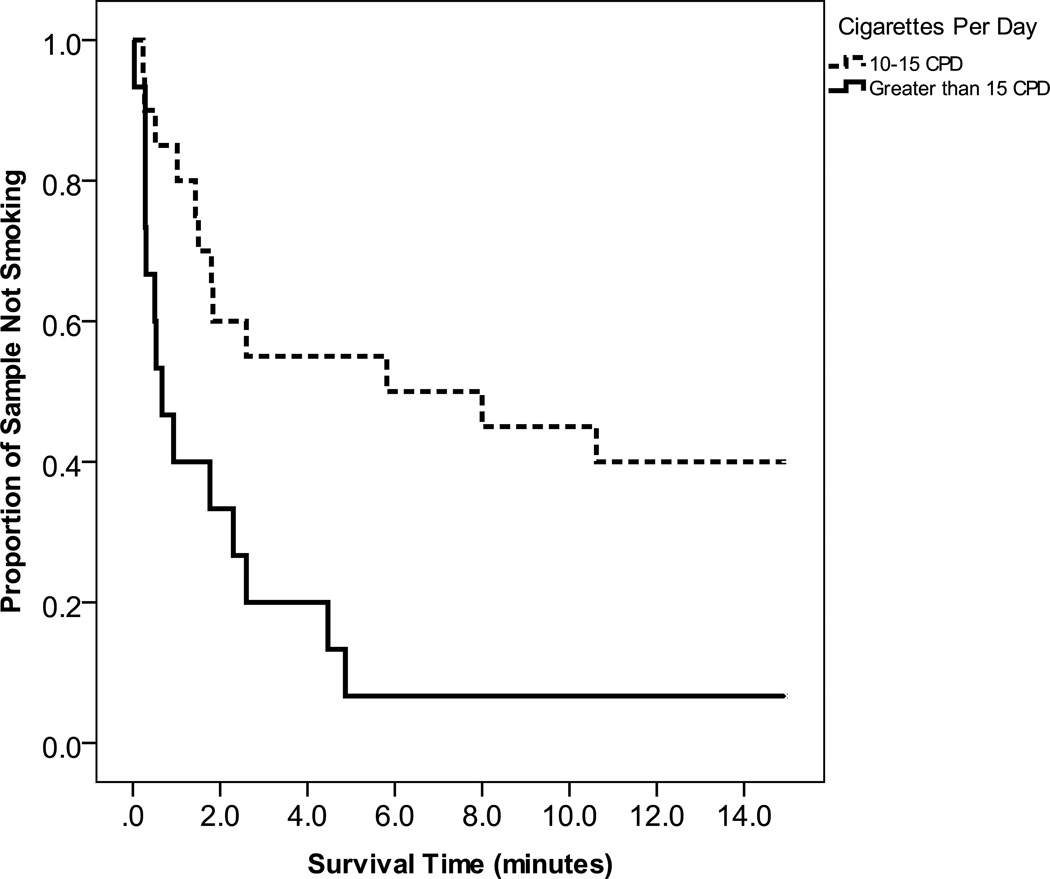

A Cox regression analysis predicting latency to first puff indicated that smoking was significantly more like among those with greater pre-task craving (β=.04, p=.017; 95% CI Odds Ratio 1.01–1.07), and who smoked more cigarettes per day (β=.08, p=.004; 95% CI Odds Ratio 1.02–1.15). The median latency to first puff was significantly shorter for smokers reporting pre-task craving above the median (0.93 minutes) compared to those with pre-task craving below the median (10.62 minutes) (see Figure 1 for Kaplan-Meier survival graphs). Participants who reported smoking more than 15 cigarettes per day on average had a shorter median latency to first puff (0.66 minutes) compared to those who smoked 10–15 cigarettes per day (5.82 minutes) (see Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Survival curves for number of minutes to first puff for those with high vs. low pre-task craving.

Figure 2.

Survival curves for number of minutes to first puff for those with high vs. low baseline smoking heaviness.

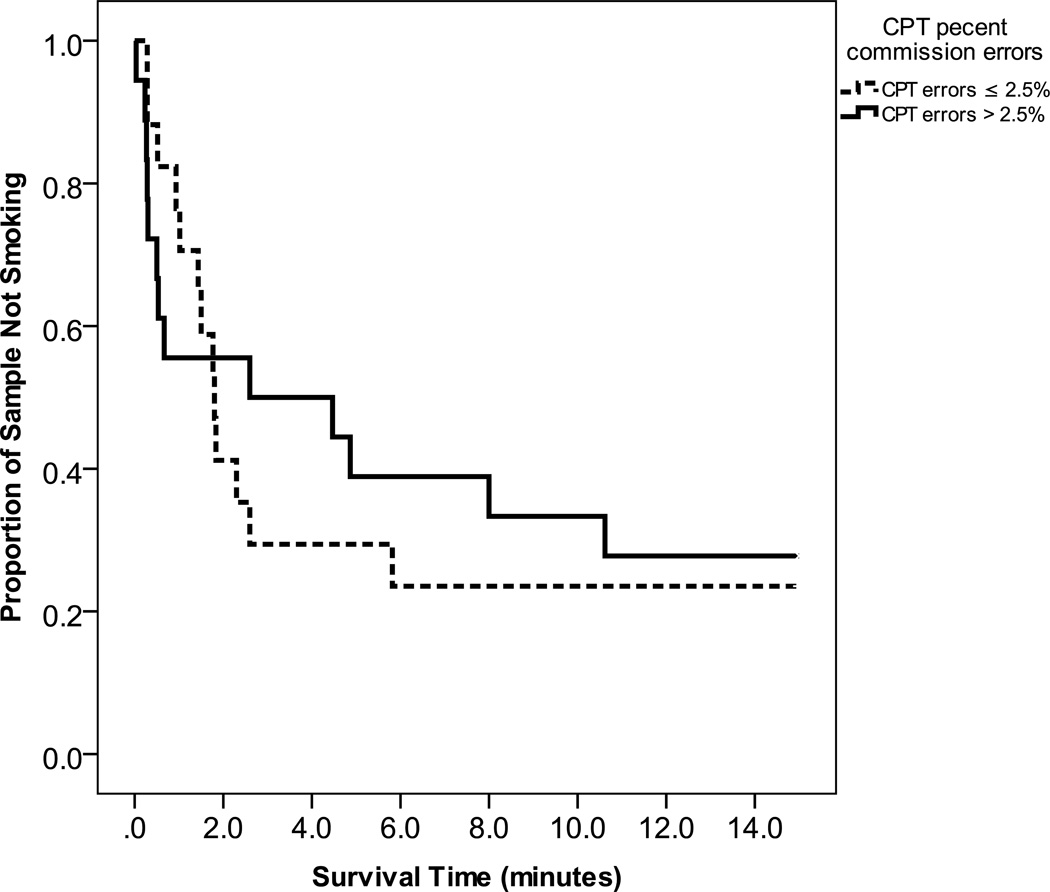

A violation of the proportionality assumption was detected in the relation between percent commission errors on the CPT and time (see Figure 3). Consequently, the effect of this predictor was analyzed in two separate epochs. Greater behavioral disinhibition on the CPT predicted a significant increase in the odds of smoking in the first two minutes of the choice task (β=.44, p=.025; 95% CI Odds Ratio 1.06–2.28), but not in the remaining 13 minutes, (β=.11, p=.461; 95% CI Odds Ratio 0.83–1.50).

Figure 3.

Survival curves for number of minutes to first puff for those with high vs. low commission error rates on the CPT.

Other smoking history variables and putative risk factors for relapse were not significantly related to latency to first puff and were removed from the model. Median survival times were estimated for the remaining predictors to provide initial descriptive information about the magnitude of effects (Table 4).

Table 4.

Median Survival Time Estimates

| Variable | Median Survival Time (min.) |

SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 2.30 | 1.891 | 0.00–6.00 |

| Female | 1.76 | 1.242 | 0.00–4.20 |

| Smoking History | |||

| Maximum abstinence > 2 weeks | 1.50 | 0.57 | 0.38–2.62 |

| Maximum abstinence ≤ 2 weeks | 4.46 | 2.40 | 0.00–9.18 |

| No. past quit attempts ≤ 2 | 1.83 | 0.55 | 0.76–2.90 |

| No. past quit attempts > 2 | 1.80 | 0.83 | 0.18–3.42 |

| Nicotine Dependence | |||

| WISDM average > 4.213 | 1.02 | 0.53 | 0.00–2.06 |

| WISDM average ≤ 4.213 | 4.86 | 3.91 | 0.00–12.53 |

| Impulsivity | |||

| BIS total > 67 | 1.80 | 0.07 | 1.66–1.94 |

| BIS total ≤ 67 | 2.30 | 1.09 | 0.17–4.42 |

| Delay Discounting average k > 0.062 | 1.80 | 0.80 | 0.23–3.36 |

| Delay Discounting average k ≤ 0.062 | 1.83 | 0.84 | 0.17–3.50 |

| CPT % commission (first 2 minutes) > 2.5 | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.24–0.33 |

| CPT % commission (first 2 minutes) ≤ 2.5 | 1.02 | 0.40 | 0.24–1.79 |

| CPT reaction time (msec) < 430 | 1.80 | 1.42 | 0.00–4.58 |

| CPT reaction time (msec) > 430 | 1.83 | 0.56 | 0.72–2.94 |

| Distress Tolerance | |||

| aDTS total ≤ 56 | 1.50 | 0.62 | 0.29–2.71 |

| aDTS total > 56 | 2.30 | 0.84 | 0.64–3.96 |

| DTS regulation ≤ 10 | 1.02 | 0.62 | 0.00–2.22 |

| DTS regulation > 10 | 5.82 | 5.73 | 0.00–17.04 |

| Distressed Breath Holding < 6.5 sec | 1.43 | 0.76 | 0.00–2.91 |

| Distressed Breath Holding > 6.5 sec | 2.60 | 1.53 | 0.00–5.60 |

Note. SE=standard error; CI= confidence interval.

Survival times were estimated based on a median split for the DTS total score and four subscales. For three of the subscales, the results were identical to the DTS total score, so this information is presented once for economy.

Total Number of Puffs (n=26)

A linear regression predicting total number of puffs indicated that lower scores on the regulation subscale of distress tolerance (signifying lower tolerance and greater regulation efforts to alleviate distress) predicted more puffs taken (β=−.44, t(24)= − 2.46, p=.022, R2=.201). No other candidate predictors were significantly related to the number of puffs taken. Total number of puffs did not differ by gender in this sample (men, M=18.11, SD=11.18; women M=17.62, SD=12.00), t(24)=0.10, n.s., Cohen’d d=0.04.

Time Spent Smoking (n=26)

A linear regression model predicting time spent smoking in the task indicated that higher nicotine dependence scores (on the core subscales of the WISDM-68) predicted greater smoking duration in the task (β=−.64, t(24)=2.12, p=.044, R2=.159). No other candidate predictors were significantly related to total time spent smoking. Time spent smoking in the task did not differ by gender (men, M=6.33 minutes, SD=1.86; women, M=6.32 minutes, SD=2.04), t(24)=0.01, n.s., Cohen’s d=0.005.

Change in Craving (N=35)

Post-task craving was examined in a regression model controlling for initial craving level. Smoking during the task was associated with a significant decrease in craving from pre- to post-task, t(24.052)=5.56, p<.001, Cohen’s d=−1.74. None of the other predictors (nicotine dependence, impulsivity, distress tolerance, or smoking history variables) had independent relations with craving change.

Discussion

This study examined risk factors for smoking in a novel, laboratory-based smoking choice task designed to serve as a proxy for the kinds of choices smokers may face during attempts to quit smoking. Preliminary results support the validity of the smoking-choice paradigm. For nicotine-deprived smokers, the choice between two cigarettes now and four later yielded variable smoking responses in the laboratory. Furthermore, choosing to smoke rather than abstain in the task was meaningfully related to pre-task craving and smoking heaviness. This supports the notion that the conditions of this laboratory smoking-choice task produced strong momentary motivation to smoke. These results suggest that the smoking-choice paradigm may serve as a useful analog for smoking behavior and may facilitate the identification of proximal determinants of relapse that could be targeted in future interventions.

In the current sample, two of the hypothesized risk factors for relapse had large effects on latency to smoke during the smoking choice task. Specifically, greater craving and smoking heaviness predicted shorter smoking latencies. This is consistent with research identifying craving and smoking heaviness as risk factors related to early relapse (e.g., Killen & Fortmann, 1997). Experiencing greater craving before being exposed to the potent smoking trigger used in this task (lighting and holding one’s preferred brand of cigarettes while surrounded by smoking accessories and images) was related to shorter latencies to taking a first puff from the cigarette. This is consistent with other evidence showing that evoked craving predicts smoking behavior (e.g., Carpenter et al., 2009) and suggests that drug motivational processes are relevant to the real-time smoking choices made by smokers in this paradigm. In addition, the fact that heavier smokers waited a significantly shorter period of time before puffing in this challenging task further supports the claim that behavior during this task is related to drug motivational processes associated with smoking heaviness.

The tendency to experience craving in the presence of smoking cues and to smoke heavily may reflect underlying nicotine dependence processes. The results of this study provide further evidence to support the relation between nicotine dependence and smoking behavior. Specifically, greater self-reported nicotine dependence (as assessed by dimensions of automaticity, loss of control, craving, and tolerance) predicted spending more time smoking in the task. This supports the notion that smoking heaviness is an observable outcome linked to latent nicotine dependence processes (Piper et al., 2008a). The results suggest that nicotine dependence processes may govern real-time smoking behavior in this smoking-choice task.

The results of this study also provided new information about the relation between impulsivity and real-time smoking behavior. The results indicated that greater behavioral disinhibition, as measured by commission error rate on a behavioral task, had a large effect on smoking risk in the first two minutes of the smoking choice task. Interestingly, this form of impulsivity (having difficulty inhibiting prepotent responses) was only related to latency to puff at the beginning of the task, when the smoking trigger and opportunity were introduced. This may have implications for smoking cessation attempts and suggests that individuals who show high levels of behavioral disinhibition may have a more difficult time inhibiting the immediate impulse to smoke if presented with a salient smoking cue or opportunity than would less impulsive smokers. The speed of responding to stimuli (reaction time) was not related to smoking latency or other dimensions of smoking behavior (e.g., number of puffs) in this task. As such, disinhibition may be the dimension of impulsivity that is most relevant to the processes governing smoking behavior in this novel smoking choice paradigm.

Impulsive decision making did not have a meaningful effect on smoking latency or other dimensions of smoking behavior in the current task, contrary to expectations. Although the current task is an explicit choice paradigm pitting a smaller reward available sooner against a larger, delayed reward (with a minimal delay), the choices exhibited by smokers in this task were not significantly associated with similar choices regarding monetary rewards. Inspection of the data in this sample indicated that some of the average discounting values were extremely high (yielding values greater than one that suggest respondents viewed rewards delayed as little as one day as worthless or that respondents were not carefully considering the options before responding). Participants’ pattern of responding across tasks was carefully examined, and the pattern of results did not change when excluding those suspected of inattention (n=3). Previous research has demonstrated that smokers are more impulsive and have steeper discounting rates when deprived from nicotine, versus non-deprived (Mitchell, 2004; Field et al., 2006). As such, it is possible that the extremely steep discounting rates observed in some of the subjects in this study reflect real and intense responses to the 12 hours of nicotine deprivation experienced by smokers (as confirmed by CO testing) prior to the study. It is also possible, however, that low distress tolerance or insufficient motivation led some respondents to disengage from the task and to provide invalid data. These possibilities can be explored in future research that incorporates additional manipulation and validity checks in study procedures and assessments. The lack of association between responses to cigarette and monetary rewards may also reflect differences in the processing of these types of rewards. Research has shown that smokers discount money and cigarettes at different rates and that the difference in the processing of cigarette versus monetary rewards is greater in the context of 24-hour nicotine deprivation (Mitchell, 2004). It may be that the lack of association between monetary discounting rates and smoking behavior reflects a divergence in the decision-making processes tapped by the two tasks in the context of deprivation and craving.

Results also indicated that a greater need to regulate distress (lower tolerance for distress) differentiated those who smoked and abstained and predicted greater smoking heaviness in the task. The smoking-choice task in this study was designed to elicit strong motivation to smoke and competing motivation to abstain to obtain the reward of four cigarettes at the end of the session. As such, the task likely induces response conflict and some degree of frustration. To successfully achieve the goal of obtaining four (instead of two) cigarettes, subjects needed to tolerate the craving and frustration induced by the smoking-choice task. The observed marginal association between a self-reported tendency to attempt to regulate (i.e., minimize or eliminate) negative emotions and actual smoking in the choice task supports the negative reinforcement model of drug motivation (Baker et al., 2004) that asserts that smokers who associate smoking with relief from affective distress are those most prone to heavy smoking and relapse. This is consistent with previous research indicating a significant relation between low distress tolerance on the regulation subscale and number of cigarettes smoked daily (Leyro et al., 2010).

There are several limitations to this current study. Due to the preliminary, exploratory nature of this study, the analyses were not corrected for family-wise error. In addition, the size of the sample was small. The statistical significance of the results should therefore be interpreted with caution; however, the results are informative in providing initial validity information about the laboratory smoking-choice task. The study did not assess the predictive validity of real-time behavior in the smoking-choice task, so the relation to future relapse during a cessation attempt is currently unknown. The results also failed to show relations between smoking during the task and proxies for cessation success such as longest duration of past quit attempt, perhaps due to the small size of the sample or undetected outliers. Additionally, study participants were not currently seeking treatment, so these results might not generalize to smokers currently motivated to quit or those who cannot maintain 12 hours of abstinence. In a population of smokers interested in quitting, consideration would need to be made for the timing of this task relative to the quit day because the incentive value of cigarettes or a smoking opportunity may change with the proximity to a quit attempt. The deprivation manipulation strengthens our interpretation of the potential validity of this task in predicting how smokers will respond to exposure to smoking cues and opportunities when deprived during a quit attempt, but we cannot rule out the possibility that the task will perform differently among people hoping to remain abstinent than among subjects who plan to smoke after the laboratory session.

Furthermore, there are some limitations that should be noted for the selected study measures. We controlled for the known effect of gender on breath-holding duration, but not physical health status. While we are fairly confident in the 12 hour nicotine deprivation manipulation as verified by self-report and expired breath CO concentration, asking subjects to abstain in the laboratory or clinic would allow for greater assurance that this manipulation worked as intended.

Although efforts were made to advertise for study volunteers broadly in the community, the participants were mostly men (74.3%) and many (23.5%) were current students, so the results might not generalize to other, community-based samples. Examination of how participants heard about the study did not reveal any systematic gender difference in recruitment method. More women (n=16) than men (n=9) canceled or did not show for their scheduled appointment, although the reason for this is unknown. Recent literature suggests that women are less likely to quit smoking than men (e.g., Japuntich et al., 2011), so it is possible that women were less likely to achieve the required 12-hour abstinence prior to the appointment. It will be important for future studies to replicate our findings in a sample with a greater proportion of women. Due to the limited power in this pilot sample, we were unable to examine significant gender differences in predictors or outcomes and gender by risk factor interactions.

The current study provided initial validity data regarding a novel, behavioral smoking challenge. This laboratory model of a self-directed smoking choice addresses some of the limitations of previous laboratory cue-reactivity models (as described in Perkins, 2012), and may be a promising new approach to investigate the relation between relapse risk factors and smoking behavior. Results supported the hypotheses that some dimensions of dependence (including self-reported nicotine dependence dimensions, the tendency to experience craving when nicotine-deprived, and smoking heavily), impulsivity (behavioral disinhibition), and distress intolerance (feeling the need to regulate distressing emotions) were associated with real-time smoking behavior during a standardized choice task. Future research is needed to assess the predictive validity of the smoking-choice task and to identify the specific dimensions of dependence, impulsivity, and distress tolerance that are most closely related to real-time smoking in the face of smoking triggers and opportunities. Additional research is also needed to determine whether these risk factors have additive or interactive effects on real-time smoking, as well. Understanding how these vulnerability factors influence real smoking behavior might identify mechanisms of relapse that can be targets for future intervention studies.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Award Number RC1DA028129 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Danielle McCarthy, Ph.D., PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None of the authors have financial, personal, or other disclosures related to this article or study.

All authors contributed in a significant way to the manuscript and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Krysten W. Bold, Department of Psychology, Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey

Haewon Yoon, Department of Psychology, Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey

Gretchen B. Chapman, Department of Psychology, Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey

Danielle E. McCarthy, Department of Psychology and Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, & Aging Research, Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey

References

- Abrantes AM, Strong DR, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Carpenter LL, Price LH, Brown RA. The role of negative affect in risk for early lapse among low distress tolerance smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:1394–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey SR, Goedeker KC, Tiffany ST. The impact of cigarette deprivation and cigarette availability on cue-reactivity in smokers. Addiction. 2010;105:364–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02760.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker F, Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Delay discounting in current and never-before cigarette smokers: Similarities and differences across commodity, sign, and magnitude. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:382–392. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein A, Trafton J, Ilgen M, Zvolensky MJ. An evaluation of the role of smoking context on a biobehavioral index of distress tolerance. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:1409–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC. The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: The case for incentive salience. Psychopharmacology. 2007;191:391–431. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0578-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Odum AL, Madden GJ. Impulsivity and cigarette smoking: Delay discounting in current, never, and ex-smokers. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:447–454. doi: 10.1007/pl00005490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolt DM, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Japuntich SJ, Fiore MC, Smith SS, Baker TB. The Wisconsin predicting patients' relapse questionnaire. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11:481–492. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon TH, Herzog TA, Juliano LM, Irvin JE, Lazev AB, Simmons VN. Pretreatment task persistence predicts smoking cessation outcome. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:448–456. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR. Distress tolerance and duration of past smoking cessation attempts. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:180–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Strong DR, Kahler CW, Zvolensky MJ, Carpenter LL, Price LH. A prospective examination of distress tolerance and early smoking lapse in adult self-quitters. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2009;11:493–502. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter MJ, Saladin ME, DeSantis S, Gray KM, LaRowe SD, Upadhyaya HP. Laboratory-based, cue-elicited craving and cue reactivity as predictors of naturally occurring smoking behavior. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:536–541. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BL, Tiffany ST. Meta-analysis of cue–reactivity in addiction research. Addiction. 1999;94:327–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BL, Tiffany ST. The cue-availability paradigm: The effects of cigarette availability on cue reactivity in smokers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;9:183–190. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.9.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults-United States 2000. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2002;51:642–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults and trends in smoking cessation-United States 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008;58:1227–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco use: Targeting the nation’s leading killer. Chronic Disease at a Glance Reports. 2011:2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112(1):155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK. The computerized continuous performance test. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21:891–892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK. Conners’ Continuous Performance Test II (CPTII) for Windows Technical Guide and Software Manual. New York: Multi-Health Systems, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland AL, Brandon TH, Quinn EP. The Smoking Consequences Questionnaire—Adult: Measurement of smoking outcome expectancies of experienced smokers. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:484–494. [Google Scholar]

- Cox LS, Tiffany ST, Christen AG. Evaluation of the brief Questionnaire of Smoking Urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2001;3:7–16. doi: 10.1080/14622200020032051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford JR, Henry JD. The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): Construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2004;43:245–265. doi: 10.1348/0144665031752934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry S, Marlatt GA, Peterson AV, Lutton J. Survival analysis and assessment of relapse rates. In: Donevan DM, Marlatt GA, editors. Assessment of addictive behaviors. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1988. pp. 454–473. [Google Scholar]

- Dallery J, Raiff BR. Delay discounting predicts cigarette smoking in a laboratory model of abstinence reinforcement. Psychopharmacology. 2007;190:485–496. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0627-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran N, Spring B, McChargue D, Pergadia M, Richmond M. Impulsivity and smoking relapse. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6:641–647. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001727939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droungas A, Ehrman RM, Childress AR, O'Brien CP. Effect of smoking cues and cigarette availability on craving and smoking behavior. Addictive Behaviors. 1995;20:657–673. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00029-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, Santarcangelo M, Sumnall H, Goudie A, Cole J. Delay discounting and the behavioral economics of cigarette purchases in smokers: The effects of nicotine deprivation. Psychopharmacology. 2006;186:255–263. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0385-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR. Motivation, working memory, and decision making: A cognitive-motivational theory of personality vulnerability to alcoholism. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews. 2002;1:183–205. doi: 10.1177/1534582302001003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz NL, Curry SJ, Wewers ME. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service; 2008. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence 2008 Update. [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Japuntich SJ, Leventhal AM, Piper ME, Bolt DM, Roberts LJ, Baker TB. Smoker characteristics and smoking cessation milestones. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;40(3):286–294. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javors MA, Hatch JP, Lamb RJ. Cut-off levels for breath carbon monoxide as a marker for cigarette smoking. Addiction. 2004;100:159–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Within-subject comparison of real and hypothetical money rewards in delay discounting. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2002;77:129–146. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.77-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen JD, Fortmann SP. Craving is associated with smoking relapse: Findings from three prospective studies. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1997;5:137–142. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.5.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan-Sarin S, Reynolds B, Duhig AM, Smith A, Liss T, McFetridge A, Potenza MN. Behavioral impulsivity predicts treatment outcome in a smoking cessation program for adolescent smokers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:79–82. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyro TM, Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A. Distress tolerance and psychopathological symptoms and disorders: A review of the empirical literature among adults. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:576–600. doi: 10.1037/a0019712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson L, Stipelman BA, Duplinsky M, Brown RA, Lejuez CW. Distress tolerance and pre-smoking treatment attrition: Examination of moderating relationships. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:1385–1393. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SH. Measures of impulsivity in cigarette smokers and non-smokers. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:455–464. doi: 10.1007/pl00005491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SH. Effects of short-term nicotine deprivation on decision-making: Delay, uncertainty, and effort discounting. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2004;6:819–828. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331296002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mischel W, Ebbesen EB, Zeiss AR. Cognitive and attentional mechanism in delay of gratification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1972;21:204–218. doi: 10.1037/h0032198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mischel W, Shoda Y, Peake PK. The nature of adolescent competencies predicted by preschool delay of gratification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:687–696. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.4.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mischel W, Shoda Y, Rodriguez ML. Delay of gratification in children. Science. 1989;244:933–937. doi: 10.1126/science.2658056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman JP. Reaction to punishment in extraverts and psychopaths: Implications for the impulsive behavior of disinhibited individuals. Journal of Research on Personality. 1987;21:464–480. [Google Scholar]

- Niaura R, Abrams DB, Shadel WG, Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, Sirota AD. Cue exposure treatment for smoking relapse prevention: A controlled clinical trial. Addiction. 1999;94:685–695. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9456856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1995;6:768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne TJ, Smith PO, Adams SG, Diefenbach L. Pretreatment cue reactivity predicts end-of-treatment smoking. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:702–710. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne TJ, Smith PO, McCracken LM, McSherry WC, Antony MM. Assessing nicotine dependence: A comparison of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire (FTQ) with the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) in a clinical sample. Addictive Behaviors. 1994;19:307–317. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA. Subjective reactivity to smoking cues as a predictor of quitting success. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2012;14:383–387. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper ME, Bolt DM, Kim S, Japuntich SJ, Smith SS, Niederdeppe J, Baker TB. Refining the tobacco dependence phenotype using the Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008a;117:747–761. doi: 10.1037/a0013298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Bolt DM, Smith SS, Lerman C, Benowitz N, Baker TB. Assessing dimensions of nicotine dependence: An evaluation of the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale (NDSS) and the Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM) Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2008b;10:1009–1020. doi: 10.1080/14622200802097563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper ME, Piasecki TM, Federman EB, Bolt DM, Smith SS, Fiore MC, Baker TB. A multiple motives approach to tobacco dependence: The Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM 68) Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:139–154. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau CS, Carton SM, Lutzke ML, Flessland KA, Pomerleau OF. Reliability of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire and the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence. Addictive Behaviors. 1994;19:33–39. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JM, Daughters SB, Bornovalova MA, Brown RA, Lejuez CW. Substance use disorders. In: Zvolensky M, Bernstien A, Vujanovic A, editors. Distress tolerance. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM. The Distress Tolerance Scale: Development and validation of a self-report measure. Motivation and Emotion. 2005;29:83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Spinella M. Correlations between orbitofrontal dysfunction and tobacco smoking. Addiction Biology. 2002;7:381–384. doi: 10.1080/1355621021000005964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanford MS, Mathias CW, Dougherty DM, Lake S, Anderson NE, Patton JH. Fifty years of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale: An update and review. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;47:385–395. [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST, Drobes DJ. The development and initial validation of a questionnaire on smoking urges. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1467–1476. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderVeen JW, Cohen LM, Cukrowicz KC, Trotter DRM. The role of impulsivity on smoking maintenance. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2008;10:1397–1404. doi: 10.1080/14622200802239330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;47:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett JB, Singer JD. Investigating onset, cessation, relapse, and recovery: Why you should, and how you can use discrete-time survival analysis to examine event occurrence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:952–965. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulfert E, Block JA, Santa Ana E, Rodriguez ML, Colsman M. Delay of gratification: Impulsive choices and problem behaviors in early and late adolescence. Journal of Personality. 2002;70:533–552. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.05013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Brown RA. Panic attack history and smoking cessation: An initial examination. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:825–830. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]