Abstract

While numerous studies have established a link between alcohol use and partner violence in adulthood, little research has examined this relation during adolescence. The current study used multivariate growth models to examine relations between alcohol use and dating aggression across grades 8 through 12 controlling for shared risk factors (common causes) that predict both behaviors. Associations between trajectories of alcohol use and dating aggression were reduced substantially when common causes were controlled. Concurrent associations between the two behaviors were significant across nearly all grades but no evidence was found for prospective connections from prior alcohol use to subsequent dating aggression or vice versa. Findings suggest that prevention efforts should target common causes of alcohol use and dating aggression.

Whereas a large body of research has documented a consistent and robust link between alcohol use and adult intimate partner violence (for a review, see Foran & O’Leary, 2008) few studies have examined relations between alcohol use and dating aggression during adolescence. Both dating aggression and alcohol use initiate and then become increasingly prevalent during the middle and high school years and can have serious negative consequences for adolescent health and well-being (Ackard, Eisenberg & Neumark-Sztainer, 2007; Chassin, et. al, 2009). Moreover, patterns of relationship conflict that are established during this period may carry over into adulthood (Bouchey & Furman, 2003; Gidycz, Orchowski, King & Rich, 2008; Smith, White & Holland, 2003). Therefore, a better understanding of how the relation between alcohol use and dating aggression unfolds during adolescence may inform efforts to reduce or prevent these behaviors across the life-span. To this end, the current study provides an empirical examination of several different theoretical models of the association between alcohol use and dating aggression using data from a cohort-sequential study of adolescents in grades 8 through 12.

Empirical Studies of Associations between Alcohol Use and Dating Aggression

There is extensive empirical evidence documenting an association between alcohol use and partner aggression (Foran & O’Leary, 2008). For example, in their meta-analysis of studies examining adult intimate partner violence, Foran and O’Leary (2008) found a small to moderate effect size for the association between alcohol use and abuse and male-to-female violence and a small effect size for female-to-male violence. In a meta-analysis of studies examining youth dating violence, Rothman, Reyes, Johnson, and LaValley (2011) similarly found evidence of a significant positive relation between alcohol use and both male and female dating aggression. However, the majority of previous studies examining associations between alcohol use and youth dating aggression have used college-aged samples, and findings from the few cross-sectional and longitudinal studies that have examined associations between the two behaviors using middle-and high-school aged samples are mixed (for a review, see Rothman, et al., 2011).

Theoretical Models of Relations between Alcohol Use and Dating Aggression

Theoretical explanations for relations between alcohol use and partner violence include: (a) the proximal effects model, (b) the indirect effects model, and (c) the common cause or spurious effects model (Foran & O’Leary, 2008; Klosterman & Fals-Stewart, 2006; Leonard & Quigley, 1999). The proximal effects model posits that alcohol intoxication plays a causal role in increasing risk of dating abuse perpetration through its psychopharmacological effects on cognitive function. Specifically, intoxication can intensify feelings of excitement and curiosity, lead a person to overreact to perceived provocation, and decrease the saliency of cues that aggressive behavior will have negative consequences (i.e. threat inhibition), thereby increasing risk of confrontation and violence (Phil & Hoaken, 2002). This model implies that alcohol use increases risk of dating aggression exclusively during the time frame when alcohol is exerting a pharmacological effect.

The indirect effects model posits that the causal association between alcohol use and dating aggression is mediated by other variables such as relationship quality. For example, several researchers have suggested that elevated alcohol use by one or both romantic partners leads to relationship dissatisfaction and greater frequency of interpersonal conflict and, in turn, to increased risk of partner aggression (Fagan & Browne, 1994; Fischer, et al., 2005; Quigley & Leonard, 2000; White & Chen, 2000). In contrast to the proximal effects model, which implies that alcohol use and dating aggression will be concurrently associated, the indirect effects model implies that the causal influence of alcohol use on dating aggression should be studied over a longer time-window. That is, the indirect effects model suggests that elevated alcohol use during one time period may prospectively predict dating aggression measured at a subsequent time period.

Another version of the indirect effects model suggests that prior aggression, including dating aggression, may indirectly lead to subsequent alcohol use (White, Brick, & Hansell, 1993). Mechanisms explaining this pathway (from prior aggression to subsequent alcohol use) include the notions that: (i) involvement in aggression may lead to delinquent peer affiliations and, in turn, to substance use (e.g., Fite, Colder, Lochman & Wells, 2007) and (ii) involvement in aggression may lead to alcohol use as a means for coping with the negative social and emotional consequences of being abusive (White, et al., 1993).

Regardless of the specific mediating mechanism, each of the indirect relations reviewed above imply that elevated alcohol use during one time period may prospectively predict dating aggression at a subsequent time period or vice-versa. Indeed, some longitudinal studies of the developmental associations between substance use and non-dating aggression have found evidence of reciprocal pathways between the two behaviors (Huang, White, Kosterman, Catalano & Hawkins, 2001; White, Loeber, Stouthamer-Loeber, & Farrington, 1999).

A third conceptual model that has been posited to explain the link between alcohol use and dating aggression is the “common cause” model. This model suggests that alcohol use and dating aggression are linked because they share causal determinants. For example, several risk factors have been found to predict both alcohol use and dating or partner violence among adolescents and young adults including: peer aggression or antisocial behavior (e.g., Andrews, Foster, Capaldi & Hops, 2000; Fite, et al., 2007), emotional distress (e.g., Wolfe, Wekerle, Scott, Straatman, & Grasley, 2004; Tschann, Flores, Pasch & Van Oss, 2005), and aspects of the family environment including family conflict (e.g., Bray, Adams, Getz, & Baer, 2001; Ehrensaft et al., 2003). The notion that alcohol use and dating aggression share etiological origins is also consistent with several theories of adolescent health risk behavior (e.g., Problem Behavior theory, General Deviance theory, Primary Socialization theory), that suggest that alcohol use and dating aggression are both manifestations of an underlying propensity towards deviance. These theories identify numerous general causal determinants (e.g., social bonding, family environment) that can lead to involvement in a range of problem behaviors, including substance use and aggression (see Jessor, Donovan & Costa, 1991; Jessor & Jessor, 1977; Oetting & Donnermeyer, 1998; Osgood, Johnson, O’Malley, & Bachman, 1988).

Specifying the Relations between Dating Aggression and Alcohol Use over Time

Taken together, the theoretical models reviewed above suggest there may be any one of a number of pathways linking a set of repeated measures of dating abuse and alcohol use over time. To help clarify the nature of these pathways and map each pathway onto the statistical modeling framework used in the current study, we classify the theoretical linkages between dating aggression and alcohol use into two types: (i) time-specific relations and (ii) time-stable relations.

Time-specific relations comprise associations between levels of alcohol use at a particular time point and levels of dating aggression at a particular time point. Time-specific relations between repeated measures of alcohol use and dating aggression are implied by both the proximal effects and indirect effects models that suggest that levels of dating aggression and alcohol use at any specific time point may be concurrently or prospectively related.

In contrast, theories that view both alcohol use and dating aggression as forms of deviant behavior driven by common causes suggest that there may be an overall time-stable association between levels of alcohol use and levels of dating aggression over time. That is, it follows from these theories that overall levels of and changes in ones’ propensity towards deviance will influence levels of involvement in both alcohol use and dating aggression over time, resulting in time-stable correlations between the underlying trajectories for both behaviors. These correlations are referred to as time-stable because they represent the overall associations between levels of and changes in alcohol use and dating aggression across the time period assessed. It also follows from these theories that correlations between trajectories of alcohol use and dating aggression would be attenuated once the influence of shared risk factors is accounted for.

Developmental Considerations

From a developmental perspective, adolescence is a particularly compelling period in which to examine associations between alcohol use and dating aggression. First, like other antisocial behaviors, both alcohol use and dating aggression initiate and then tend to increase across early and middle adolescence. Studies that identify common causes of alcohol use and dating aggression that originate in childhood or early adolescence may guide primary prevention efforts that reduce involvement in these behaviors during adulthood.

Second, a developmental approach suggests that the nature of the association between alcohol use and dating aggression may evolve over the course of adolescence. Romantic relationship processes such as levels of romantic involvement, relationship content, concepts of relationships and perceptions of their social functions all undergo marked changes with increasing age (Collins, Welsch, & Furman, 2009). In addition, capacities for dealing with conflict and disagreement in romantic relationships evolve over the life-span. As these processes and capacities develop over time relations between alcohol use and dating aggression may also change. For example, some studies have found that the overlap between substance use and violence is stronger during early adolescence than in late adolescence (White, et al., 1999). One potential explanation for this finding is that, during early adolescence, substance use and aggression comprise part of a general problem behavior syndrome whereas, during late adolescence, individuals begin to specialize in specific types of deviant behavior (Fagan, Weis, & Cheng, 1998; White, et al., 1999). It is also possible that the types of mechanisms relating alcohol use and dating aggression may change over time. For example, indirect effects models that suggest that alcohol misuse may increase risk for partner aggression by deleteriously affecting relationship quality, may be more likely to apply to late adolescent or young adult relationships, which are characterized by greater levels of commitment and interdependence, than to relationships among younger teens.

The Current Study

The current study used a multivariate growth modeling approach to examine both time-specific and time-stable relations between repeated measures of dating aggression and alcohol use using data from a multi-wave longitudinal study of adolescent boys and girls that spans grades 8 through 12. Following from theories that view alcohol use and dating aggression as manifestations of an underlying propensity towards deviant behavior, we examined the correlations between the underlying growth processes governing trajectories of alcohol use and dating aggression over time. In addition, based on the common-cause model, we examined associations between the two behaviors both before and after controlling for baseline psychosocial risk factors that have been identified as contributors to both alcohol use and dating aggression including: family conflict, social bonding, emotional distress and peer aggression. Based on the proximal and indirect effects models, we also simultaneously examined concurrent and bidirectional prospective linkages between the repeated measures for each behavior. Finally, we examined whether the pathways relating alcohol use and dating aggression differed for boys and girls using a multiple group approach.

Method

Participants

The sample for this research was drawn from a multi-wave cohort sequential study of adolescent health risk behaviors that spanned middle and high school (Ennett, et al., 2006). The current study uses four waves of data starting when participants were in the 8th, 9th and 10th grades (wave one) and ending when participants were in the 10th, llth and 12th grades (wave four). The average age of 8th-grade participants was 13 years; across all waves of the study ages ranged between 11 and 19 years. There was a six-month time interval between the first three waves of data collection and a one-year time interval between waves three and four. Participants were enrolled in two public school systems located in two predominantly rural counties with higher proportions of African Americans than in the general United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2001).

At each assessment all enrolled students in the targeted grades who were able to complete the survey in English and who were not in special education programs or out of school due to long-term suspension were eligible for the study. Parents had the opportunity to refuse consent for their child’s participation by returning a written form or by calling a toll-free telephone number. Adolescent assent was obtained from teens whose parents had consented immediately prior to the survey administration. Trained data collectors administered the questionnaires in student classrooms on at least two occasions to reduce the effect of absenteeism on response rates. To maintain confidentiality, teachers remained at their desks while students completed questionnaires and the students placed questionnaires in envelopes before returning them to the data collectors. The Institutional Review Board for the School of Public Health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill approved the data collection protocols.

At wave one, 6% of parents refused consent, 6% of adolescents declined to participate and 8% were absent on the days when data were collected for a total of 2636 students completing a survey at wave one. The response rate, calculated as the proportion of adolescents who completed a survey out of those eligible for the survey at wave 1 was 79%. For this study, analyses excluded adolescents who; (1) did not report their age or who reported being out of the typical age range of 12–19 for the grades studied (n=50, 2%), (2) did not report their dating status or reported never dating across all four assessments (n=247, 9%) or (3) were missing data on the alcohol use or dating aggression measures across all waves of the study (n=67, 3%), yielding a sample size of 2272. Nearly all of the adolescents in the sample contributed to at least two waves of data collection (n=2127, 94%), with 75% participating in 3 or more waves (n=1722).

The sample included 1239 males (47%) and 1397 females (53%). By youth self-report, the sample was 46% White, 46% Black and 8% other race or ethnicity. Approximately 29% of participants reported that the highest education attained by either parent was high school or less across all waves of the study. At baseline, the prevalence of any physical dating aggression in the past three months was 18%, which is within the range reported by other studies of teen dating violence (Foshee & Matthew, 2007). Baseline prevalence of any alcohol use in the past three months was 28%, past three month prevalence of heavy alcohol use was 19%, and lifetime alcohol use prevalence was 62%. The prevalence rates for alcohol use in our study are similar to those found in national studies of teen alcohol use (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman & Schulenberg, 2009).

Measures

Measures included the two outcomes of interest, alcohol use and dating aggression as well as psychosocial covariates and demographic control variables. The alcohol and dating aggression measures were collected at all waves, allowing construction of time-varying measures. Measures of the psychosocial covariates (family conflict, emotional distress, social bonding and peer aggression) were analyzed as time-invariant and were drawn from the baseline assessment to be consistent with the common cause model (which views these variables as precursors to alcohol use and dating aggression). Demographic control variables (race, sex and parent education) were also time invariant.

Alcohol use

Alcohol use was measured as a composite of frequency, quantity and heavy use. For all measures, alcoholic beverages were defined as including beer, wine, wine coolers and liquor and a “drink” was defined as a glass of wine, a can of beer, a bottle or can of wine cooler, a shot glass of liquor or a mixed drink. The frequency item assessed the number of days that the adolescent had one or more drinks of alcohol in the past three months with six response categories ranging from 0 days to 20 days or more. The quantity item assessed how many drinks the adolescent usually consumed on a typical drinking occasion in the past three months with 6 response categories ranging from less than one drink to five or more drinks. Heavy alcohol use was assessed by four items asking adolescents how many times they had: 3 or 4 drinks in a row, 5 or more drinks in a row, gotten drunk or very high from drinking alcohol, or been hung over. Response categories that ranged from 0=no times to 5=10 or more times in the past 3 months. Scores on the heavy use items were averaged and then the frequency, quantity and heavy use measures were standardized and summed to create a composite measure of alcohol use at each wave (Cronbach’s alpha=.92 across all waves).

Physical Dating Aggression

Dating aggression was measured at all waves using a short version of the Safe Dates Physical Perpetration Scale (Foshee, et al., 1996). Adolescents were asked, “During the past 3 months, how many times did you do each of the following things to someone you were dating or on a date with? Don’t count it if you did it in self-defense or play.” Six behavioral items were listed: “slapped or scratched them,” “physically twisted their arm or bent back their fingers,” “pushed, grabbed, shoved, or kicked them,” “hit them with your fists or with something else hard,” “beat them up,” and “assaulted them with a knife or a gun.” Each item had five response categories ranging from 0 to 10 times or more in the past three months. Scores on these items were summed to create a physical dating aggression scale measure at each wave (Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .87 to .96).

Psychosocial Covariates

Peer aggression was measured using six items that assessed how many times in the past three months the respondent had pushed, slapped or kicked someone, physically twisted someone’s arm or bent back their fingers, hit someone with their fist or something else hard, beat someone up or assaulted someone with a knife or gun. Adolescents were specifically asked to exclude acts that they had perpetrated against a date. The scores on these items were averaged to create a composite scale of adolescent physical aggression towards peers at baseline (Cronbach’s alpha=.87).

Family conflict was assessed by three items from Bloom’s (1985) self-report measure of family functioning. Adolescents were asked how strongly they agreed or disagreed with the following three items when thinking about their family life in the past three months: we fight a lot in our family; family members sometimes get so angry they throw things; and family members sometimes hit each other. The scores on these items were averaged to create a measure of baseline exposure to family conflict (Cronbach’s alpha=.87).

Emotional distress was measured as a composite of three subscales assessing anger, anxiety and depression in the past three months. Anger was assessed by three items drawn from the revised Multiple Affective Adjective Checklist (MAACL-R) that asked adolescents how often they felt mad, angry or furious in the past three months (Zuckerman & Lubin, 1985). Anxiety was measured using a shortened version of the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety scale (Reynolds & Richmond, 1979) and depression was measured using three items from the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (Angold, Costello, & Messer, 1995). Both anxiety and depression were assessed by presenting adolescents with a list of statements describing how they may have felt in the past 3 months. Seven symptoms of anxiety (e.g., I felt sick to my stomach) and three symptoms of depression (e.g., I did everything wrong) were listed. Cronbach’s alphas were satisfactory for each of the individual subscales (α =.88 for anger, α =.88 for anxiety, α = .92 for depression) and subscale scores were significantly correlated (p<.001 for all correlations). A composite measure of emotional distress was created by standardizing and averaging subscale scores.

Social Control theory guided our conceptualization of weak conventional social bonds as a shared risk factor for dating violence and alcohol use (Hirschi, 1969). According to this theory, social bonds play a key role in deterring antisocial behavior by encouraging conformity to conventional values and beliefs. Degree of social bonding was measured as a composite of three subscales: teen’s endorsement of conventional beliefs, commitment to prosocial values, and degree of religiosity. Endorsement of conventional beliefs was measured by asking adolescents how strongly they agreed or disagreed with the following three statements: it is good to be honest; people should not cheat on tests; and, in general, police deserve respect. Commitment to prosocial values was measured by assessing how important or unimportant adolescents felt about four items: finishing high school; going to college; having a happy family life; and having a close group of friends. Degree of religiosity was assessed by three items: frequency of religious service attendance; the importance of religion to the respondent; and the extent to which religious beliefs influence the respondent’s actions. Cronbach’s alphas for each of the individual scales were acceptable (α=.73 for prosocial values, α= .74 for conventional beliefs, α= .76 for religiosity), and subscale scores were significantly correlated (p<.001 for all correlations). A composite measure of baseline social bonding was created by standardizing and averaging subscale scores.

Demographics

Sex was coded such that the reference group was female. Race and ethnicity was based on the adolescent’s modal response across all waves of assessment and dummy coded to include White (reference group), Black, and other race or ethnicity (including Latinos). Parent education ranged from less than high school (0) to graduate school or more (3) and was measured as the highest education attained by either parent across all waves. Grade-level was used as the time-metric and ranged from fall semester grade 8 through fall semester grade 12.

Analytic Approach

The overarching goal of this study was to examine several different models of the interrelations between dating aggression and alcohol use over time. To fully explore each of the theoretical associations between the two behaviors within the same analytic framework we estimated a series of multivariate latent curve models, including an autoregressive latent curve model (for a detailed description of latent curve models, see Bollen & Curran, 2006). Multivariate latent curve models presuppose that the repeated measures for the outcomes of interest (dating aggression and alcohol use in this case) are each governed by separate developmental processes. These developmental processes are modeled by using the observed repeated measures to estimate a single underlying growth trajectory (or latent curve) for each person across all time points. Underlying latent factors (also referred to as “growth factors”) form the trajectory model and represent the intercept, linear, and potentially non-linear (e.g., quadratic) components of the trajectory.

Using a multivariate growth modeling approach, associations between the developmental processes for each behavior may be modeled at two different levels. First, the latent growth factors (i.e., intercepts, slopes, quadratic factors) for each outcome may be allowed to correlate. These correlations represent the shared time-stable associations between the behaviors over time. Second, time-specific associations may be estimated between the repeated measures for each behavior. For example, repeated measures for each behavior may be allowed to correlate within-time (cross-sectional associations). In addition, using a special type of multivariate growth model called an autoregressive latent trajectory (ALT) model, cross-lagged parameters may be estimated between the repeated measures for each outcome. In the context of the current study, time-stable associations between developmental trajectories of alcohol use and dating aggression are implied by the common-cause model. Time-specific cross-sectional and cross-lagged associations are implied by the proximal and indirect effects models.

Modeling Process

Analyses for this study proceeded in several phases. First, to take advantage of the cohort sequential design of this study, data were reorganized such that the grade level of the child was used as the primary metric of time rather than wave of assessment. This allowed for trajectories to be continuously modeled across grades eight through twelve. Information was available across eight discrete data points: grade 8 fall (n=778), grade 8 spring (n=663), grade 9 fall (n=1317), grade 9 spring (n=667), grade 10 fall (n= 1814), grade 10 spring (n=586), grade 11 fall (n=1037) and grade 12 fall (n=426). We examined potential cohort differences in growth patterns using the multiple-group method proposed by Duncan and Duncan (1994) and found no evidence of cohort differences in the latent trajectories for either of our outcomes. We also examined potential biases in our models due to the fact that data were collected from students nested within schools. We found negligible design effects (DEFF) and non-significant intraclass correlations (ICC) for both outcomes across all waves (for both outcomes the average ICC was <.01 and the average DEFF was < 2.00). Furthermore, adjusting for nesting had no effect on the latent curve factor means or variances for either outcome. As such, the models reported below do not account for this nested structure, but are likely not biased by this omission.

In the first phase of analysis, flat, linear, quadratic and completely non-linear “free-loading” models were estimated and compared to identify the functional form of the latent growth curve that best fit the repeated measures for alcohol use and for dating aggression (Bollen & Curran, 2006). Within each functional form, chi-square difference tests of nested models were performed to identify the optimal model structure. The best-fitting model was selected based on the criteria of parsimony, component and overall fit.

In the second phase of analysis we examined the associations between the underlying growth processes for alcohol use and dating aggression using a multivariate latent curve model. The multivariate growth model linked the latent curves for alcohol use and dating aggression through the estimation of covariances between the latent factors for each outcome. Demographic and baseline psychosocial variables (common causes) were incorporated into the model by regressing each covariate on each of the latent growth factors for each outcome. Covariance parameter estimates were compared across the unconditional and conditional models to assess whether and how the addition of the covariates affected the strength of the associations between alcohol use and dating aggression. In the third phase of analysis, we examined cross-lagged relations between the two behaviors using an autoregressive latent trajectory (ALT) modeling approach and following the guidelines set forth by Bollen and Curran (2004). Finally, a multiple group approach was used to examine whether there were sex differences in the pathways relating alcohol use to dating violence.

All analyses for this study were conducted using M-Plus version 5.1 (Muthén and Muthén, 2007). The repeated measures for alcohol use and dating aggression were logged and all models were fit using the maximum likelihood robust estimator to adjust for non-normality in outcome distributions. Nested models were compared using the Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square difference test (Satorra, 2000). Multiparameter Wald tests were used to evaluate whether correlations between the two behaviors varied by sex or over time. Overall model fit was assessed using the comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and its 90% confidence interval (for a review of these fit indices see Bollen & Curran, 2006). The RMSEA score was subtracted from 1 to put it on the same metric as the other fit indices. Good model fit was indicated where levels on these indices were greater than 0.95.

Results

Table 1 provides the means, standard deviations and correlations among the repeated measures of alcohol use and dating aggression by grade-level. The two behaviors were moderately correlated both within and across grade levels, with the strongest inter-behavior correlations occurring in the spring of grade 8 (r=.40, p<.001) and the spring of grade 10 (r=.35, p<.001). Observed means for dating aggression generally increased over time up until the spring of grade 10 and then decreased thereafter. Observed means for alcohol use increased across each grade level, but increases were smaller in the later grade levels.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations and Correlations for Repeated Measures of Alcohol Use and Dating Violence by Grade Level

| Outcome | Grade | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | 15. | 16. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Alcohol use | 8 | -- | |||||||||||||||

| 2. Alcohol use | 8.5 | .53 | -- | ||||||||||||||

| 3. Alcohol use | 9 | .43 | .40 | -- | |||||||||||||

| 4. Alcohol use | 9.5 | na | na | .55 | -- | ||||||||||||

| 5. Alcohol use | 10 | .40 | .43 | .45 | .48 | -- | |||||||||||

| 6. Alcohol use | 10.5 | na | na | na | na | .50 | -- | ||||||||||

| 7. Alcohol use | 11 | na | na | 0.37 | 0.51 | .50 | .49 | -- | |||||||||

| 8. Alcohol use | 12 | na | na | na | na | .38 | .44 | .45 | -- | ||||||||

| 9. Dating violence | 8 | .33 | .19 | .11 | na | .08 | na | na | na | -- | |||||||

| 10. Dating violence | 8.5 | .65 | .42 | .14 | na | .11 | na | na | na | .44 | -- | ||||||

| 11. Dating violence | 9 | .17 | .19 | .26 | .10 | .08 | na | .11 | na | .32 | .51 | -- | |||||

| 12. Dating violence | 9.5 | na | na | .25 | .26 | .24 | na | .24 | na | na | na | .51 | -- | ||||

| 13. Dating violence | 10 | .11 | .15 | .13 | .13 | .16 | .12 | .17 | −.04 | .31 | .39 | .31 | .41 | -- | |||

| 14. Dating violence | 10.5 | na | na | na | na | .12 | .36 | .22 | .15 | na | na | na | na | .43 | -- | ||

| 15. Dating violence | 11 | na | na | .19 | .13 | .08 | .14 | .12 | .11 | na | na | .43 | 0.49 | .40 | .45 | -- | |

| 16. Dating violence | 12 | na | na | na | na | −.04 | −.01 | −.06 | .05 | na | na | na | na | .35 | .45 | .40 | -- |

| M | 0.29 | 0.34 | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.57 | 0.64 | 0.67 | 0.71 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.21 | |

| SD | 0.60 | 0.66 | 0.77 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.52 | 0.63 | 0.59 | 0.66 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.51 |

Note: NA=Not available due to cohort sequential design. All correlations were significant at p<.05 except for coefficients that are italicized.

Univariate Latent Curve Models for Dating Aggression and Alcohol Use

Dating aggression

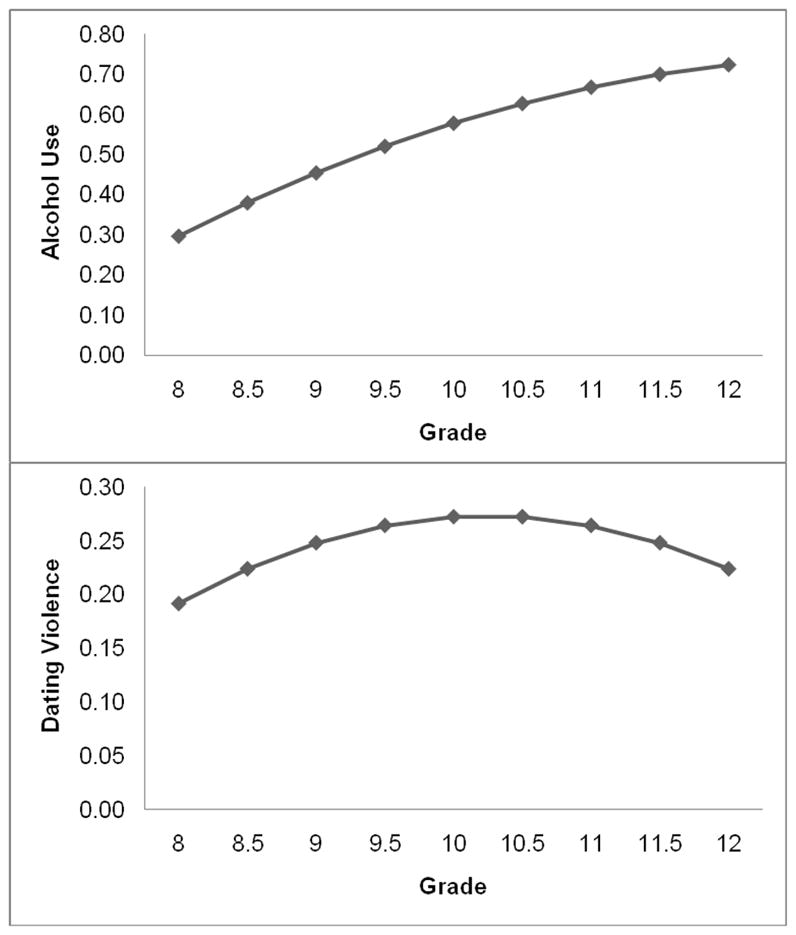

Consistent with previous research using this sample, the best fitting model for dating aggression was a quadratic model with slope and quadratic factor variances constrained to zero and heteroscedastic residual variance over time (Reyes, Foshee, Bauer, & Ennett, 2011). This model fit the data well (χ2 (32)=64.41, p=.001; CFI=.96; TLI=.96; 1-RMSEA=.98). The estimated means of the latent factors indicate that the model-implied mean trajectory for the sample was characterized by an initial perpetration score of 0.19 units (p<.001), a significant positive linear growth component (b=0.07, p<.001), and a significant negative quadratic component (b=−0.02, p<.001). Estimates of residual variance in the repeated measures of dating aggression (i.e., variability in alcohol use not explained by the latent growth factors) were significant across all grade levels. The bottom graph of Figure 1 graphically depicts the model-implied mean curve, which peaks in grade 10 and then decreases through grade 12.

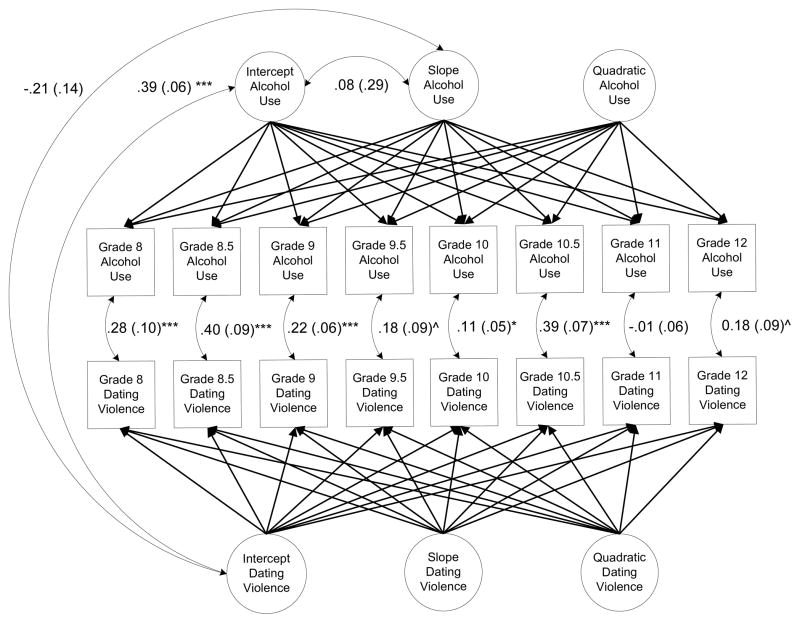

Figure 1.

Mean trajectories for alcohol use and dating violence perpetration across grades 8 through 12. Top: Alcohol use; Bottom: Dating violence perpetration.

Alcohol use

The best fitting model for alcohol use was a quadratic model with the variance of the quadratic factor constrained to zero and heteroscedastic residual variance over time. Model fit was very good (χ2 (18)=38.36, p=.004; CFI=.97; TLI=.97; 1-RMSEA=.98). The estimated means for the latent factors indicate that the model-implied mean trajectory for the sample was characterized by an initial alcohol use score of 0.30 (p<.001), a significant positive linear growth component (b=0.17, p<.001), and a significant negative quadratic component (b=−0.02, p<.01). Estimates of residual variance in the repeated measures of alcohol use were significantly different from zero across all grade levels. The top graph of Figure 1 presents the model-implied mean trajectory for alcohol use and shows that levels of alcohol use tended to increase over time with the magnitude of change decreasing at later grades.

Multivariate Growth Model

To assess associations between the growth processes governing alcohol use and dating aggression a multivariate growth model was specified in which correlations were estimated between the latent growth factors for each outcome (see Figure 2). Specifically, a cross-behavior correlation was estimated between the intercept factors for each behavior and between the intercept factor for dating aggression and the slope factor for alcohol use. A within-behavior correlation was estimated between the intercept and slope factors for alcohol use. Because the univariate models found negligible variance in the dating aggression slope factor and in the quadratic factors for both outcomes, correlations were not estimated with these latent factors. Residual variances were allowed to correlate across behaviors and vary over time.

Figure 2.

Unconditional multivariate latent curve model of adolescent alcohol use and dating violence perpetration. Model X2=97.92 (68), p=.01; CFI=0.98; TLI=0.98; 1-RMSEA (90% CI)=0.99 (0.98, 0.99). Quadratic factor variances and the slope factor variance for dating violence were constrained to zero. Parameter estimates are standardized so that values denote correlations between latent factors and repeated measures for alcohol use and dating violence. Latent factor means, residual variances and fixed factor loadings are not shown.

^ p<.10; * p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001

The unconditional multivariate growth model fit the data well (χ2(116)=186, p<.001; CFI=.96; TLI=.95; 1-RMSEA=.98) and is presented in Figure 2. The latent intercept factors for alcohol use and dating aggression were strongly positively correlated (r=.39, p<.001), suggesting that, on average, individuals who reported higher levels of alcohol use also reported higher levels of dating aggression across grades eight through twelve. Correlations between the dating aggression latent intercept factor and the alcohol use slope factor (r=−0.21, p=.13) and between the alcohol use intercept and slope factors (r=.08, p=.78) were not statistically significant, indicating that higher initial (i.e., grade 8) levels dating aggression and alcohol use were not significantly associated with faster or slower increases in alcohol use over time. Within time-point associations (i.e., residual correlations) between the repeated measures for each behavior were positive and statistically significant across nearly all grade levels (grade 11 was the only exception). We also note that constraining the within time-point correlations to be equal over time led to a significant decrement in model fit (Wald test: 31.54 (7), p<.001), suggesting that the strength of these correlations varied significantly across grade levels.

Multivariate Growth Model with Demographic and Psychosocial Covariates

Each demographic (race, sex, and parent education) and baseline psychosocial (family conflict, social bonding, peer aggression and emotional distress) covariate was regressed on all of the latent curve factors for alcohol use and dating aggression. Two models were estimated, one with only the demographic controls (Model 1) and one with both the demographic and psychosocial controls (Model 2). Correlations between the latent intercepts for alcohol use and dating aggression and within time-point concurrent associations were examined for each model. In addition, the amount of variance explained in the latent intercepts for alcohol use and dating aggression was examined for each model using an r-square measure.

Fit statistics, intercept r-squares and standardized parameter estimates, which denote the estimated correlations between the trajectories for alcohol use and dating aggression and between the repeated measures at each grade level, are presented in Table 2 for each of the conditional multivariate growth models. Consistent with the common cause model, inclusion of the psychosocial covariates led to a substantial decrease in the strength of the correlation between the dating aggression and alcohol use intercepts from r=.41 (p<.001) to r=.24 (p<.01). Inclusion of the demographic controls explained a small but significant amount of variability in the dating aggression intercepts (r-square=.09, p<.001), but did not explain a significant amount of variance in the alcohol use intercepts (r-square=.02, p=.25). In contrast, inclusion of the psychosocial covariates led to a substantial increase in the amount of variance explained in both the dating aggression (r-square increment=.32) and alcohol use (r-square increment=.24) intercepts. Consistent with the proximal effects model, which implies a time-specific concurrent association between the two behaviors, within-time (i.e., residual) correlations between the repeated measures for alcohol use and dating aggression persisted across nearly all grade levels even after both sets of covariates were incorporated (grade 11 was again the only exception).

Table 2.

Multivariate Growth Model Parameter Estimates (Robust Standard Errors)

| Parameter or Pathway | Model 1: Demographic Controls | Model 2: Demographic and Psychosocial Controls |

|---|---|---|

| Latent growth factor correlations | ||

| DV intercept with AL intercept | 0.41 (.07)*** | 0.24 (.08)** |

| DV intercept with AL slope | −0.08 (.15) | 0.04 (.16) |

| AL intercept with AL slope | 0.06 (.31) | 0.18 (.38) |

| Residual correlations | ||

| Grade 8 | 0.29 (.10)*** | 0.20 (.09)* |

| Grade 8.5 | 0.41 (.08)*** | 0.42 (.08)*** |

| Grade 9 | 0.22 (.06)*** | 0.18 (.06)** |

| Grade 9.5 | 0.18 (.09)* | 0.18 (.09)* |

| Grade 10 | 0.11 (.05)* | 0.11 (.04)* |

| Grade 10.5 | 0.36 (.07)*** | 0.36 (.06)*** |

| Grade 11 | 0.02 (.06) | 0.03 (.06) |

| Grade 12 | 0.20 (.09)* | 0.21 (.09)* |

| Intercept factor r-square | ||

| Alcohol use | 0.02 (.01) | 0.25 (.05)*** |

| Dating violence | 0.09 (.03)*** | 0.41 (.06)*** |

Note: AL=Alcohol Use, DV=Dating Violence. Each covariate was regressed on all of the latent curve factors for each behavior. Demographic covariates were sex, race and parent education; psychosocial covariates were family conflict, peer violence, social bonding and emotional distress. The intercept factor r-square denotes the amount of variance explained in the latent intercepts for each behavior by the covariates in the model.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Specific covariate effects on trajectories of alcohol use and dating violence

Parameter estimates and standard errors from Model 2 (which included all demographic and psychosocial covariates) are presented in Table 3. Where a covariate was significantly associated with one or more latent growth factors for a particular outcome we used the model parameter estimates to calculate predicted trajectories of dating violence and alcohol use at different levels of the covariate. Findings suggest that gender was not associated with alcohol use but was significantly associated with dating aggression such that boys reported significantly lower levels of perpetration than girls across all grade-levels (b=−.19, SE=.03). Black race was related to both outcomes but in the opposite direction; Blacks reported significantly higher levels of dating aggression than Whites (b=.12, SE=.03) across all grade levels, whereas Blacks reported lower initial (Grade 8) levels (intercept effect b=−.09, SE=.04) as well as slower initial increases in alcohol use over time (slope effect b=−0.15, SE=.05) compared to Whites. Higher levels of family conflict and peer aggression were associated with higher levels of both dating aggression and alcohol use across all grades. Social bonding was significantly negatively associated with levels of dating aggression across all grade-levels and with levels of alcohol use across early and middle adolescence, but effects weakened during late adolescence (quadratic effect b=0.03, SE=.01). Emotional distress was not associated with dating aggression, but was significantly associated with steeper initial increases in alcohol use (slope effect; b=0.08, SE=.04).

Table 3.

Regression of Latent Growth Factors on Demographic and Psychosocial Covariates

| Latent Growth Factor | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Parameter | Intercept b (se) | Slope b (se) | Quadratic b (se) |

| Effects on Dating Violence | |||

| Male | −0.19 (.03)*** | −0.01 (.04) | −0.003 (.01) |

| Black | 0.12 (.03)*** | 0.02 (.04) | −0.003 (.01) |

| Other race | −0.02 (.06) | 0.04 (.07) | −0.012 (.02) |

| Parent education | 0.01 (.02) | 0.003 (.02) | −0.002 (.004) |

| Family conflict | 0.04 (.02)* | 0.02 (.02) | −0.004 (.01) |

| Social bonding | −0.10 (.03)** | −0.03 (.04) | 0.01 (.01) |

| Emotional distress | 0.03 (.03) | 0.07 (.04) | −0.02 (.01) |

| Peer aggression | 0.36 (.07)*** | −0.10 (.08) | 0.01 (.02) |

| Effects on Alcohol Use | |||

| Male | −0.06 (.04) | −0.03 (.05) | 0.02 (.01) |

| Black ( vs. white) | −0.09 (.04)* | −0.15 (.05)** | 0.02 (.01) |

| Other race (vs. white) | −0.10 (.07) | −0.04 (.09) | −0.01 (.02) |

| Parent education | 0.03 (.02) | −0.02 (.02) | 0.01 (.01) |

| Family conflict | 0.04 (.02)* | 0.01 (.02) | −0.002 (.01) |

| Social bonding | −0.16 (.03)*** | −0.07 (.04) | 0.03 (.01)*** |

| Emotional distress | 0.06 (.03) | 0.08 (.04)* | −0.02 (.01) |

| Peer aggression | 0.32 (.06)*** | −0.14 (.07)* | 0.03 (.02) |

Note: Parameter estimates are from a multivariate latent growth model of dating violence and alcohol use across grades 8 through 12. Each demographic and psychosocial covariate was regressed on the intercept, slope and quadratic latent growth factors for both outcomes.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Autoregressive Latent Trajectory (ALT) Model

An initial ALT model was specified by modifying the unconditional multivariate growth model described above as follows: (1) the grade 8 repeated measures for dating aggression and alcohol use were specified as predetermined (i.e., exogenous) and allowed to covary with the latent growth factors to avoid bias introduced by the problem of “infinite regress” (Bollen & Curran, 2004), (2) the alcohol use slope factor variance and covariances, which were estimated at or near their boundary levels in previous models, were constrained to zero, and (3) autoregressive paths were estimated between the repeated measures of each outcome. The initial ALT model fit the data well (χ2(55)=73, p=.02; CFI=.98; TLI=.97; 1-RMSEA=.98), however, only one of the parameter estimates for the autoregressive paths between repeated measures was statistically significant. Next, we added prospective cross-lagged pathways from alcohol use to dating aggression, which did not lead to a significant improvement in model fit (χ2(6)=9.33, p=.16). Finally, we added cross-lagged pathways from dating aggression to alcohol use, which again did not lead to a significant improvement in model fit (χ2(6)=9.84, p=.16). Parameter estimates for cross-lagged pathways were generally positive, but not statistically significant. Contrary to expectations based on indirect effects models, these results suggest that, after controlling for time-stable and within-time concurrent associations between the two behaviors, alcohol use did not prospectively predict dating aggression six months later or vice-versa.

Gender differences in relations between alcohol use and dating violence

We next used a multiple group structural equation modeling approach to examine whether there were gender differences in the pathways relating the repeated measures of alcohol use and dating violence. We first estimated a fully cross-lagged ALT model that allowed for all parameter estimates to vary across groups (i.e., for males and females). We then systematically imposed equality constraints on parameter estimates corresponding to each of the following sets of pathways relating alcohol use and dating violence: (1) prospective cross-lagged pathways (including exogenous lagged pathways), (2) autoregressive pathways (including exogenous autoregressive pathways), (3) the latent intercept factor correlation, and (4) residual correlations. Multiparameter Wald tests were used to determine whether imposing equality constraints led to a significant decrement in model fit.

Findings suggest that there were not significant gender differences in cross-lagged pathway estimates, (Wald test: 22.95 (14), p=.06), autoregressive pathway estimates (Wald test: 18.82 (14), p=.17), or in the latent intercept growth factor correlation (Wald test: .06 (1); p=.80). Residual correlations were found to differ significantly across groups (Wald test: 15.96 (7), p=.03). Post-hoc probing of each of the individual grade-specific correlation suggest that correlations between alcohol use and dating violence were similar for males and females across grades 8 through 10, but differed significantly in grades 11 (Wald test: 4.40 (1), p=.04) and 12 (Wald test: 8.44 (1), p=.004). Specifically, grade 11 correlations between alcohol use and dating violence were positive for males (r=.14, p=.13) and negative for females (r=−.10, p=.16), though correlations were not significant for either group. Grade 12 correlations were positive and significant for males (r=.44, p<.001) but not females (r=.01, p=.95).

Discussion

The finding that overall levels of alcohol use and dating aggression are linked (as evidenced by the significant correlation between the latent intercept factors for each behavior) during adolescence is consistent with theories that view aggression and substance use as manifestations of an underlying tendency towards deviance (Jessor, et. al, 1991; Osgood, et al., 1988). It follows from these theories that individuals with a greater (or lesser) propensity towards deviant behavior would tend to report greater (or lesser) levels of involvement in both alcohol use and dating aggression across all of the grade levels we assessed. We also found that the association between the latent trajectory intercepts was substantially reduced when baseline psychosocial risk factors posited to be common causes of both behaviors were included in the model (from r=.42 in the demographics only model to r=.24 in the psychosocial covariates model). This result is also consistent with the aforementioned theories and with the common cause model of the relation between alcohol use and dating aggression, which posits that associations between the two behaviors are driven by shared causal determinants.

Even after accounting for time-stable associations between trajectories of alcohol use and dating aggression and after adjusting for demographic and psychosocial covariates, within time-point correlations between alcohol use and dating aggression were of moderate size and were statistically significant across nearly all grade levels, with the highest correlations occurring in the spring of grades 8 (r=.42) and 10 (r=.36). This finding is consistent with expectations based on the proximal effects model, which posits that alcohol intoxication increases risk of dating aggression through its acute psychopharmacological effects. That is, based on the proximal effects model one would expect to see concurrent (i.e., within time-point) associations between the behaviors, reflecting the effects of higher levels of alcohol use (a marker for intoxication) in that time period on levels of dating aggression in that same time period. However, we caution that this study was not designed to directly test the proximal effects model because the temporal precedence of alcohol use in episodes of dating aggression could not be determined. Therefore, although we posit that the concurrent associations between alcohol use and dating aggression within each grade level may be reflective of a proximal effect of alcohol use on dating aggression, the associations could also be attributed to the indirect effects of alcohol use on dating aggression (or vice-versa) or to third variables (e.g., other shared risk factors) that were not controlled for in the analysis.

We also briefly note that our results suggest that within time-point correlations varied over time. Although were weren’t able to statistically test for a linear trend in the strength of concurrent associations over time, an examination of the overall pattern of the size and significance of the correlations suggests that associations tended to be stronger in earlier grades and in the spring semesters of grades 8 and 10. This trend has been reported previously in research using this sample that examined time-varying associations between heavy alcohol use and dating aggression and may be explained by developmental changes in teens’ aggressive inhibitions or their self-regulatory capacities that make it generally less likely that the psychopharmacological effects of alcohol use will lead to aggressive behavior in late adolescence (Reyes, 2011).

This study did not find evidence of cross-lagged prospective effects from alcohol use to dating aggression or vice versa, using a six-month window between the first three waves of data collections and a one-year window between waves three and four. Cross-lagged effects were examined based on indirect effects models that suggest that the causal relation between alcohol use and dating aggression is bidirectional and is mediated by other psychosocial variables (such as relationship quality), thereby implying that elevated alcohol use at one time point may prospectively predict dating aggression at another time-point and vice-versa. We posit two alternative explanations for the lack of cross-lagged effects that are related to our study design and the developmental nature of romantic relationships during adolescence. First, the six-month gap between assessments may have been too long a time-window for studying the indirect effects of alcohol use on dating aggression (and vice-versa), particularly given that adolescent dating relationships are known to be sporadic and short-term (Furman & Shaffer, 2003).

Second, indirect effects models of the pathway between alcohol use and dating aggression may simply not apply in adolescent populations. Florsheim and Moore (2008) note that the relation between substance use and interpersonal processes may differ for adolescent couples as compared to adult couples. In particular, adolescent dating couples may be less likely than adult couples to view substance use (including alcohol use) as a problem, possibly because they have yet to experience serious negative consequences of long-term misuse. In addition, because adolescent relationships are generally characterized by lower levels of commitment, interdependence and stability than adult relationships, the association between individual-level problems (such as alcohol use) and couple-level problems (such as disagreements and conflict) may generally be weaker for adolescent couples than for adult couples (Florsheim & Moore, 2008).

We note that, based on this reasoning, one might expect that indirect relations between alcohol use and dating aggression would become more apparent later in adolescence (when relationships tend to become more committed and interdependent). The current study found no evidence of a developmental (i.e., time) trend in the strength or significance of the cross-lagged associations between alcohol use and dating violence across the grade-levels assessed, however, only two time-points were assessed during late adolescence (Grades 11 and 12), limiting our ability to detect the potential emergence of cross-lagged effects during this period.

Finally, we note that, overall, time-stable and time-specific proximal associations between alcohol use and dating aggression did not differ for boys and girls, suggesting that efforts to prevent or reduce alcohol-related dating violence should address perpetration by both genders. We also found that, during late adolescence (Grades 11 and 12), proximal (within-time) associations between alcohol use and dating aggression were stronger for boys than for girls. However, we view these findings with caution given that significant gender differences were detected at only two time-points (Grades 11 and 12) and only a limited number of time points were assessed in late adolescence.

Limitations and future directions

There are several important limitations of the current study that should be acknowledged. First, observational design of the study precludes our ability to make any causal statements about the associations that were examined. Second, the sample used in the current study was drawn from schools located in predominantly rural areas in the south. Future research should examine whether findings are generalizable to non-school-based samples, high risk samples (e.g., teens exposed to domestic violence) or to other locales. Third, we did not assess and therefore were unable to examine the influence of all of the potential common causes of dating aggression and alcohol use (e.g., genetic influences, neuropsychological dysfunction, emotional dysregulation and child maltreatment). Fourth, we did not control for other substance use behaviors (e.g., marijuana use, hard drug use) which are highly correlated with alcohol use and may confound the relations we examined. Fifth, as noted previously, the current study assessed a limited number of time points in late adolescence, precluding our ability to view changes in associations across the transition to young adulthood. Relatedly, the current study did not assess relationship characteristics that may be important to consider in modeling developmental associations between alcohol use and dating aggression including dating frequency, relationship duration, commitment and interdependence.

Sixth, as noted earlier, the current study was not designed to directly test the proximal effects model because the temporal precedence of alcohol use in episodes of dating aggression could not be determined. To better establish temporal ordering, future studies of adolescent alcohol use and dating aggression should take advantage of innovative new methods, including ecological momentary assessment methods, which enable the assessment of proximal associations between the two behaviors over short time-periods (e.g., Fals-Stewart, 2003). These types of studies can examine the day-to-day relations between alcohol use and dating aggression and can be sensitive to appropriate time windows for determining the timing of effects. For example, these types of studies can assess whether the odds of dating aggression are higher on days of alcohol use compared to days of abstinence (as predicted by the proximal effects model), and also can potentially assess whether the effects of elevated alcohol use on dating aggression carry over into subsequent days (as predicted by indirect effects models).

Seventh, whereas this study focused on examining the linkages between alcohol use and dating aggression over time, theories and research suggest that relations between alcohol use and dating aggression may depend on individual and contextual factors (Klosterman & Fals-Stewart, 2006). For example, alcohol may be more likely to precipitate dating aggression among individuals who have aggressive propensities or in contexts or situations that facilitate or encourage aggressive behavior. Similarly, associations between the two behaviors may vary depending on the nature of the dating relationship in which the teen is engaged (e.g., steady versus casual, sexually intimate versus celibate). Future studies should therefore examine individual, relationship, and contextual factors that may contribute to moderate relations between the two behaviors during adolescence. Finally, some research suggests that the relation between alcohol use and partner violence is non-linear such that alcohol use must reach some threshold of quantity or frequency in order to increase risk of partner violence (O’Leary & Shumaker, 2003). This finding suggests that a fruitful avenue of future research may be to examine different patterns of adolescent alcohol use (e.g., chronic binge-drinking) and their associations with dating aggression.

Conclusions

This study makes an original and important contribution to the dating aggression literature. As far as we know, it is the first study to explicitly examine the interrelations between repeated measures of adolescent dating aggression and alcohol use over time, and findings provide novel information about how these behaviors are related during this developmental stage. In addition, by modeling all of the theoretical pathways (i.e., both time-stable and time-specific) relating the repeated measures of the two behaviors simultaneously, our analytic approach provided for a conservative statistical test of study hypotheses, strengthening our confidence in the findings (Curran & Bollen, 2001).

The results of this study support the argument that alcohol use and dating aggression are linked in part because they share common risk factors. From a prevention science perspective this finding underscores the importance of early interventions that target causal determinants of multiple risk behaviors. Results imply that early interventions that prevent or reduce family conflict, peer aggression, and increase social bonding may lead to decreased levels of both alcohol use and dating aggression during adolescence. Findings also support the notion that alcohol use and dating aggression share a unique time-specific relation even after controlling for shared precursors. This relation may reflect the acute effects of alcohol intoxication on dating abuse perpetration; however more research is needed to understand the causal mechanisms underlying this association in order to inform the design of effective preventive interventions.

Acknowledgments

Support for this dissertation research was provided by an individual National Research Service Award Pre-doctoral Fellowship awarded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (F31AA017015), and by an institutional National Research Service Award Pre-Doctoral Fellowship awarded by the National Institute on Child and Human Development (T32 HD07376) to the Carolina Consortium on Human Development at the Center for Developmental Science.

References

- Ackard DM, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Long-term impact of adolescent dating aggression on the behavioral and psychological health of male and female youth. Journal of Pediatrics. 2007;151(5):476–481. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Foster SL, Capaldi D, Hops H. Adolescent and family predictors of physical aggression, communication and satisfaction in young adult couples: A prospective analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(2):195–208. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Messer SC. Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1995;5:237–249. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom BL. A factor analysis of self-report measures of family functioning. Family Process. 1985;24(2):225–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1985.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Curran PJ. Autoregressive latent trajectory (ALT) models: a synthesis of two traditions. Sociological Methods and Research. 2004;32:336–383. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Curran PJ. Latent Curve Models: A Structural Equations Perspective. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchey HA, Furman W. Dating and romantic relationships in adolescence. In: Adams GR, Berzonsky M, editors. The Blackwell Handbook of Adolescence. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers; 2003. pp. 313–329. [Google Scholar]

- Bray JH, Adams GJ, Getz JG, Baer PE. Developmental, family, and ethnic influences on adolescent alcohol usage: a growth curve approach. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15(2):301–314. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Hussong A, Beltran I. Adolescent substance use. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley & Sons; 2009. pp. 723–764. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Welsh DP, Furman W. Adolescent romantic relationships. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:631–652. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Bollen KA. The Best of Both Worlds: Combining Autoregressive and Latent Curve Models. In: Collins LM, Sayer AG, editors. New Methods for the Analysis of Change. Washington, D C: American Psychological Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan SC, Duncan TE. Modeling incomplete longitudinal substance use data using latent variable growth curve methodology. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1994;29(4):313–338. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2904_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes E, Chen H, Johnson JG. Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: a 20-year prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(4):741–753. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Hussong A, Faris R, Foshee VA, Cai L, DuRant RH. The peer context of adolescent substance use: Findings from social network analysis. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16(2):159–186. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J, Browne A. Violence between spouses and intimates: Physical aggression between women and men in intimate relationships. In: Reiss AJ, Roth JA, editors. Understanding and preventing violence. Vol. 3. Washington, DC: National Research Council, National Academy of Sciences; 1994. pp. 115–292. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J, Weis JG, Cheng YT. Delinquency and substance use among inner city students. New York: New York City Criminal Justice Agency; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W. The occurrence of partner physical aggression on days of alcohol consumption: A longitudinal diary study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:41–52. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer JL, Fitzpatrick J, Cleveland B, Lee JM, McKnight A, Miller B. Binge drinking in the context of romantic relationships. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:1496–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fite PJ, Colder CR, Lochman JE, Wells KC. Pathways from proactive and reactive aggression to substance use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21(3):355–364. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florsheim P, Moore DR. Observing differences between healthy and unhealthy adolescent romantic relationships: Substance abuse and interpersonal process. Journal of Adolescence. 2008;31:795–814. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, O’Leary KD. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Linder GF, Bauman KE, Langwick SA, Arriaga XB, Heath JL, McMahon PM, Bangdiwala S. The Safe Dates project: theoretical basis, evaluation design, and selected baseline findings. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1996;12(5):39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Matthew RA. Adolescent dating abuse perpetration: A review of findings, methological limitations, and suggestions for future research. In: Flannery DJ, Vazjoni AT, Waldman ID, editors. The Cambridge Handbook of Violence Behavior and Aggression. New York: Cambridge; 2007. pp. 431–449. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Shaffer L. The role of romantic relationships in adolescent development. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, Orchowski LM, King CR, Rich CL. Sexual victimization and health-risk behaviors-A prospective analysis of college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23(6):744–763. doi: 10.1177/0886260507313944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T. Causes of delinquency. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, White HR, Kosterman R, Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. Developmental associations between alcohol and interpersonal aggression during adolescence. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2001;38(1):64–83. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Donovan JE, Costa FM. Beyond adolescence: Problem behavior and young adult development. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychosocial development-A longitudinal study of youth. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Silverman JE. Secondary school students (NIH Publication No. 09–7402) Vol. 1. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2009. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2008. [Google Scholar]

- Klosterman KC, Fals-Stewart W. Intimate partner violence and alcohol use: Exploring the role of drinking in partner violence and its implications for intervention. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2006;11:587–597. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Quigley BM. Drinking and marital aggression in newlyweds: An event-based analysis of drinking and the occurrence of husband marital aggression. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60(4):537–545. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Muthén LK. Mplus (Version 5.1) [Computer software] Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Oetting ER, Donnermeyer JF. Primary socialization theory: The etiology of drug use and deviance. I. Substance Use and Misuse. 1998;33(4):995–1026. doi: 10.3109/10826089809056252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Schumacker JA. The association between alcohol use and intimate partner violence: Linear effect, threshold effect, or both? Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1575–1585. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osgood DW, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Backman JG. The generality of deviance in late adolescence and early adulthood. American Sociological Reviews. 1988;53:80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Phil RO, Hoaken PNS. Biological bases of addiction and aggression in close relationships. In: Wekerle C, Wall AM, editors. The violence and addition equation: Theoretical and clinical issues in substance abuse and relationship violence. New York: Brunner-Routledge; 2002. pp. 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Quigley BM, Leonard KE. Alcohol and the continuation of early marital aggression. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24(7):1003–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes HLM, Foshee VA, Bauer DJ, Ennett ST. The role of heavy alcohol use in the developmental process of desistance in dating aggression during adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39(2):239–250. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9456-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. Factor structure and construct validity of “what I think and feel”: The Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1979;43(3):281–283. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4303_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman EF, Reyes LM, Johnson RM, LaValley M. Does the alcohol make them do it? Dating violence perpetration and drinking among youth. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2011;34:103–19. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxr027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A. Scaled and adjusted restricted tests in multi-sample analysis of moment structures. In: Heijmans RDH, Pollock DSG, Satorra A, editors. Innovations in multivariate statistical analysis. A Festschrift for Heinz Neudecker. London: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2000. pp. 233–247. [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, White JW, Holland LJ. A longitudinal perspective on dating aggression among adolescents and college-age women. American Journal Public Health. 2003;93(7):1104–1109. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.7.1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschann JM, Flores E, Pasch LA, Marin BV. Emotional distress, alcohol use, and peer violence among Mexican-American and European-American adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37(1):11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. US Government Printing Office. Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Brick J, Hansell S. A longitudinal investigation of alcohol use and aggression in adolescence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;11:62–77. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1993.s11.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Chen P. Problem drinking and intimate partner violence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(2):205–214. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Farrington DP. Developmental associations between substance use and violence. Developmental Psychopathology. 1999;11:785–803. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe D, Wekerle C, Scott K, Straatman A, Grasley C. Predicting abuse in adolescent dating relationships over 1 year: The role of child maltreatment and trauma. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:406–415. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M, Lubin B. Manual for the Multiple Affect Adjective Check List -Revised. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1985. [Google Scholar]