Abstract

Flagellar motility is a key factor for bacterial survival and growth in fluctuating environments. The polar flagellum of a marine bacterium, Vibrio alginolyticus, is driven by sodium ion influx and rotates approximately six times faster than the proton-driven motor of Escherichia coli. The basal body of the sodium motor has two unique ring structures, the T ring and the H ring. These structures are essential for proper assembly of the stator unit into the basal body and to stabilize the motor. FlgT, which is a flagellar protein specific for Vibrio sp., is required to form and stabilize both ring structures. Here, we report the crystal structure of FlgT at 2.0-Å resolution. FlgT is composed of three domains, the N-terminal domain (FlgT-N), the middle domain (FlgT-M), and the C-terminal domain (FlgT-C). FlgT-M is similar to the N-terminal domain of TolB, and FlgT-C resembles the N-terminal domain of FliI and the α/β subunits of F1-ATPase. To elucidate the role of each domain, we prepared domain deletion mutants of FlgT and analyzed their effects on the basal-body ring formation. The results suggest that FlgT-N contributes to the construction of the H-ring structure, and FlgT-M mediates the T-ring association on the LP ring. FlgT-C is not essential but stabilizes the H-ring structure. On the basis of these results, we propose an assembly mechanism for the basal-body rings and the stator units of the sodium-driven flagellar motor.

Keywords: X-ray crystallography, molecular motor

To find favorable conditions for survival and growth, bacteria swim by rotating their flagellum, a filamentous organelle for motility. The flagellum is a large macromolecular assembly composed of three major parts: the basal body, the hook, and the filament. The flagellar filament is driven by a rotary motor embedded in the cell membrane (1–4). The motor is powered by the electrochemical gradient of the coupling ion (H+ or Na+), which results in rotation of the filament like a screw. Whereas the proton motors of Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium spin up to 300 Hz, the sodium motor of Vibrio alginolyticus can rotate remarkably faster, up to 1,700 Hz (5).

The flagellar motor is made of the basal body, which includes the rotor, and a dozen stator units that surround the rotor. Each stator unit is a complex of two distinct membrane proteins, A and B, with an A4B2 stoichiometry. The stator is composed of PomA and PomB in the sodium driven motor of Vibrio sp., and MotA and MotB in the proton motors of E. coli and Salmonella, and they generate torque by conducting the coupling ion into the cytoplasm (6–11). Multiple stator complexes assemble around the rotor, although a single stator complex can generate torque (12–15).

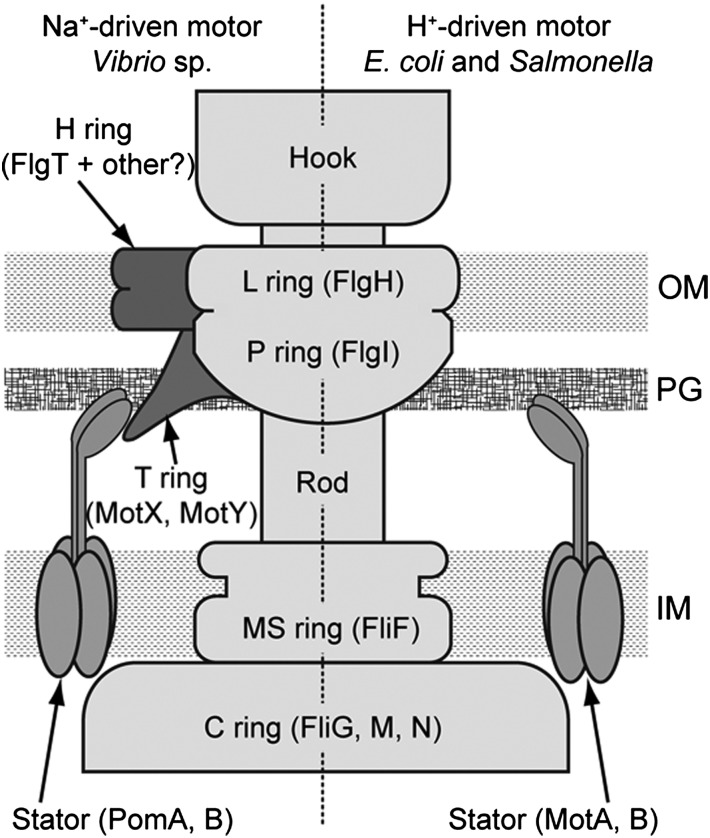

The basal body is a complex macromolecular assembly including several ring structures, such as the L, P, MS, and C rings, and a drive shaft, which is also called the rod (16). The L and P rings form a bushing for the rod, and the MS and C rings are a reversible rotor. The L and P rings are composed of FlgH and FlgI, respectively (17). The L ring is present in the outer membrane. The P ring is located in the periplasmic space below the L ring and interacts with the peptidoglycan layer. The MS ring consists of a single protein FliF and is embedded in the cytoplasmic membrane (18). The MS ring is a major component of the rotor and acts as an assembly base for other components. The C ring contains three component proteins, FliG, FliM, and FliN (16). The C ring is exposed in the cytoplasm and is essential for torque generation and switching the direction of rotation. The torque is believed to be generated by the interaction between FliG and the “A” subunit of the stator unit.

There is structural diversity of the basal body in each species (19) (Fig. 1). The basal body of Vibrio sp. has extra ring structures, the T ring and the H ring. The T ring, which is made up of MotX and MotY and is located just beneath the P ring, is essential for incorporating the stator unit into the basal body and stabilizing it (20). The N-terminal domain of MotY (MotY-N) directly interacts with MotX and the basal body (21), and MotX has been suggested to interact with PomB (22). Thus, the stator unit of the sodium-driven motor assembles around the rotor through the interaction between PomB and the T ring (20, 21). PomB has a putative peptidoglycan-binding motif in its periplasmic region and, therefore, the stator unit is thought to be anchored to the peptidoglycan layer. The structure of the C-terminal domain of MotY shows remarkable similarity to OmpA/MotB-like proteins, suggesting that the T ring is also fixed to the peptidoglycan layer (21). Thus, the stator units of the sodium-driven motor are more firmly fixed to the peptidoglycan layer and the bushing, allowing rapid rotation of the motor.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the bacterial flagellar motor. The left half shows the Na+-driven motor (Vibrio sp.), and the right half the H+-driven motor (E. coli and Salmonella). The name of the component protein is shown in parentheses. IM, inner membrane; OM, outer membrane; PG, peptidoglycan layer.

The H ring surrounds the LP ring and is thought to stabilize the basal body structure by reinforcing the bushing (23, 24). Recently FlgT was found to be an essential component of the H-ring formation (23). FlgT is a soluble periplasmic protein of 354 amino acid residues (excluding the signal peptide 23 residues). ΔflgT mutant cells lose both the T and the H rings, indicating that FlgT is involved in the formation of these rings; however, its actual role is still obscure.

To elucidate the role of FlgT on the assembly and function of the sodium driven motor, we determined the crystal structure of FlgT from V. alginolyticus at 2.0-Å resolution. The crystal structure along with our biochemical and electron microscopic analyses provide insights into the assembly process of the flagellar motor.

Results

Structure of FlgT.

We crystallized mature FlgT (Ser-24 through Leu-377) tagged with a C-terminal hexahistidine and determined its structure at 2.0-Å resolution. The final atomic model contains all FlgT residues with two histidine residues of the hexahistidine tag. FlgT comprises three distinct domains: FlgT-N (Ser-24 through Tyr-109), FlgT-M (Lys-121 through Cys-287), and FlgT-C (Pro-292 through Leu-377) (Fig. 2). FlgT-N adopts a two-layer α/β sandwich architecture composed of a four-stranded antiparallel β-sheets (β1, β2, β3, and β4) and two α-helices, α1 and α2 (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Structure of FlgT. (A) Cα ribbon drawing of FlgT. The FlgT-N, FlgT-M, and FlgT-C domains are shown in cyan, green, and red, respectively. (B) Cα backbone trace of FlgT shown in rainbow colors from the N terminus (blue) to the C terminus (red). The Cys-115 and Cys-287 residues, which form an intramolecular disulfide bond, are displayed in ball model. (C) Comparison of the FlgT-M domain (green) with the N-terminal domain of TolB (orange) (PDB ID code: 1CRZ). (D) Comparison of the FlgT-C domain (cyan) with the N-terminal domain of the F1-β subunit (magenta) (PDB ID code: 1SKY, chain E).

FlgT-M is the largest domain and consists of five β-strands (β5, β6, β7, β8, and β9), four α-helices (α3, α4, α5, and α6), and one short 310 helix (Fig. 2 A and C). The strands form a central mixed β-sheet: β5, β6, and β7 are parallel, and β7, β8, and β9 are antiparallel. The central β-sheet is flanked on one side by α3, α5 and α6, and on the other side by α4. The folding topology of FlgT-M resembles that of the N-terminal domain of TolB, which is one of the core proteins of the Tol-Pal system (PDB ID code 1CRZ; ref. 25), but the size of FlgT-M is much larger than that of the TolB domain (Fig. 2C).

FlgT-C is made up of seven β-strands (β10, β11, β12, β13, β14, β15, and β16) and one 310 helical segment (Fig. 2A). Six of the seven strands (β10, β11, β12, β14, β15, and β16) are arranged in a core β-barrel structure. β12 protrudes from the core and forms a β-hairpin with β13. Interestingly, FlgT-C shows remarkable structural similarity to the N-terminal domain of the F1-β subunit and that of FliI. Corresponding Cα atoms (51 of 79 atoms) of the N-terminal domain of the F1-β subunit (PDB ID code 1SKY) can be superimposed FlgT-C with a rmsd of 1.06 Å (Fig. 2D). Moreover, the β-hairpin of FlgT-C sticks out from the identical position where the extended loop of the F1-β N-terminal domain projects out. The β-hairpin is wound around FlgT-N and is fixed on it by forming hydrogen bonds with β1 (Fig. 2B). The conformation of the β-hairpin is further stabilized by a pi-pi stacking between Phe-56 and Trp-321, and a T-stacking between Trp-25 and Phe-326.

The loops connecting FlgT-N and FlgT-M (the NM loop) and FlgT-M and FlgT-C (the MC loop) adopt a stretched conformation (Fig. 2A). These two loops cross each other, and are linked by a disulfide bridge between Cys-115 and Cys-287 (Figs. 2B and 3A), and by a hydrogen bond between the side-chain oxygen atom of Gln-119 and the main-chain nitrogen atom of Thr-290 (Fig. 2B). The C-terminal end of the NM-loop is fixed on FlgT-C by Tyr-109, which sticks into the hydrophobic pocket composed of Pro-292, Met-304, Leu-306, Val-312, and Leu-318 (Fig. 2B and Fig. S1). These interactions seem to stabilize the relative arrangement of the three domains, because no direct interaction is observed between FlgT-N and FlgT-M. C115S, C287S, and C115S/C287S mutants, however, show no phenotype, which suggests that the S-S cross bridge is not essential for FlgT function (Fig. S2). The remaining interactions, such as hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interaction, are probably sufficient to keep the domain arrangement.

Fig. 3.

Motilities of cells expressing the domain deletion mutant variants of FlgT. (A) Primary structure of FlgT and its mutant variants used in this study. The region shown in blue (Met-1 to Ala-23) is the secretion signal sequence. FlgT-N (Ser-24 to Tyr-109), FlgT-M (Lys-121 to Cys-287), and FlgT-C (Pro-292 to Leu-377) are shown in cyan, green, and pink, respectively. (B) Motility assay of cells expressing the mutant variants of FlgT. Fresh colonies of ΔflgT (TH6) cells harboring the plasmids [1, pSU41; 2, pTH104 (FlgT-NMC); 3, pTH105 (FlgT-NMC+His6); 4, pLSK9 (FlgT-NM); 5, pLSK9-his (FlgT-NM+His6); 6, pLSK10 (FlgT-MC); 7, pLSK10-his (FlgT-MC+His6); 8, pLSK11 (FlgT-NC); 9, pLSK11-his (FlgT-NC+His6); the asterisk represents the attached hexahistidine tag] were inoculated onto 0.25% agar VPG500 plates containing kanamycin and were then incubated at 30 °C for 4 h. (C) Protein expression profiles. Whole-cell extracts and periplasmic fractions of ΔflgT cells harboring the plasmids noted above were prepared as reported (40) and were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting using an anti-FlgT antibody.

FlgT-N and FlgT-M Are Required for Efficient Flagellar Formation.

FlgT is known to be involved in both flagellation and motility in Vibrio sp. Many ΔflgT cells were nonflagellated (approximately 70%), and only approximately 10% of the flagellated cells were able to swim (23). Electron microscopic observation of the basal body of ΔflgT cells indicated that the T ring is hardly formed on the basal body in ΔflgT cells, suggesting that FlgT is required for the stable binding of MotX and MotY to the basal body (23). To investigate the role of each domain of FlgT, we analyzed the flagellation and motility of ΔflgT cells (TH6) expressing a series of domain deletion mutant variants of FlgT with the N-terminal secretion signal sequence; FlgT-NM (1–287), FlgT-MC (1–27 and 121–377), and FlgT-NC (1–115 and 287–377) (Fig. 3A). Cys-115 and Cys-287 of FlgT-NC were replaced with Ala. The cells were cultured for 3 h, and flagellation of the cells was observed under a high-intensity dark-field microscope (Table 1). The ratio of flagellated cells of the FlgT-NM mutant (approximately 70%) was at the same level as cells expressing full-length FlgT, suggesting that FlgT-C is not important for flagellar formation. In contrast, FlgT-N and FlgT-M significantly contribute to flagellation, because the number of flagellated cells of FlgT-MC and FlgT-NC were much less than those of the full-length FlgT control cells. Only 54% of FlgT-MC mutant cells and 44% of FlgT-NC mutant cells were flagellated. Considering the fact that 30% of ΔflgT cells or those containing only the vector plasmid were flagellated, which is consistent with a previous report (23), FlgT-NC still has a function for flagellation to some extent.

Table 1.

Fractions of flagellated and motile cells

| Strain and FlgT | Flagellation, % (n) | Motility, % (n) |

| TH6 | 31 (111) | 8 (224) |

| None (vector) | 29 (115) | 7 (185) |

| NMC* | 67 (141) | 48 (295) |

| NM* | 69 (121) | 37 (290) |

| MC* | 54 (114) | 26 (262) |

| NC* | 44 (101) | 6 (211) |

ΔflgT (TH6) cells harboring the plasmids [none (vector), pSU41; NMC*, pTH105 (FlgT-NMC+His6); NM*, pLSK9-his (FlgT-NM+His6); MC*, pLSK10-his (FlgT-MC+His6); NC*, pLSK11-his (FlgT-NC+His6); the asterisk represents the attached hexahistidine tag] were observed by using high-intensity dark-field microscopy.

FlgT-M Is Important for Cell Motility.

We next examined the swarming motility of the mutant cells in semisolid agar plates. FlgT-NM and FlgT-MC complemented the ΔflgT mutant, but FlgT-NC did not (Fig. 3B). After 9 h of incubation, the swarm ring of the FlgT-NC mutant slightly expanded with the same ring size of the ΔflgT mutant or the vector control cells, suggesting that the FlgT-NC mutant behaves as the ΔflgT mutant regarding motility (Fig. S3). We also counted the motile fraction of FlgT mutant cells in liquid medium by high-intensity dark-field microscopy (Table 1). After 3 h of culture, 50% of ΔflgT cells expressing FlgT recovered their swimming activity, whereas only 8% of ΔflgT cells were motile. FlgT-NM and FlgT-MC recovered the swimming activity of the ΔflgT mutant approximately 80% and 54% of the full-length FlgT, respectively. The swimming cell fraction of the FlgT-NC mutant, however, was the same level as the ΔflgT mutant. These observations indicate that FlgT-M is important for cell motility.

Basal Body Structure of the FlgT Mutant.

The flagellar basal body of Vibrio sp. has extra ring structures, the H and the T rings. These rings are lost from the basal body of ΔflgT cells, thus FlgT is thought to be involved in the formation of these rings (23). To elucidate the effect of domain deletion on the basal body ring structure, we purified basal bodies from ΔflgT cells expressing FlgT mutant proteins and observed them by electron microscopy (Fig. 4). The basal body of the FlgT-NM mutant looks almost identical to that of Vibrio wild-type cells. Both the H and the T rings are formed (Fig. 4 A and B), although the H ring seems to be slightly distorted from the wild type. This observation is consistent with the fact that FlgT-NM readily complements the ΔflgT mutant. In contrast, the basal body of the FlgT-NC mutant has neither the H ring nor the T ring and resembles that of the ΔflgT mutant (Fig. 4 D and E). The number of flagellated cells, however, was slightly increased in the FlgT-NC mutant (Table 1). Thus, FlgT-NC may very weakly interact with the basal body. Probably FlgT-NC comes off the basal body during the purification process. The basal body of the FlgT-MC mutant shows an interesting feature. Most of the H ring is lost, but the T ring is formed (Fig. 4C). This observation means that the stator unit can assemble firmly around the rotor. Thereby, FlgT-MC recovered the motility of the ΔflgT mutant.

Fig. 4.

Electron microscopic images of hook-basal bodies purified from V. alginolyticus. (A–E) Hook-basal bodies were isolated from TH7 (ΔflgT flhG) cells harboring the plasmids, pTH105 (FlgT-NMC+His6, positive control) (A), pLSK9-his (FlgT-NM+His6) (B), pLSK10-his (FlgT-MC+His6) (C), pLSK11-his (FlgT-NC+His6) (D), and pSU41 (vector control) (E). The asterisk represents the attached hexahistidine tag. The hook-basal bodies were negatively stained with 2% phosphotungstic acid (pH 7.4). (Scale bar: 50 nm.) (F) Schematic representation of the hook-basal body of V. alginolyticus.

From these lines of evidence, FlgT-N and FlgT-M are thought to be involved in the H-ring and the T-ring formation, respectively. FlgT-M is also required for the stable association of FlgT with the basal body. FlgT-C is not essential for FlgT function, but it may be a part of the H ring and/or may stabilize the H ring.

Discussion

FlgT consists of three distinct domains, FlgT-N, FlgT-M, and FlgT-C. FlgT-M and FlgT-C show structural similarities with the N-terminal domain of TolB and the N-terminal domain of F1-β subunit, respectively. To clarify the role of each domain, we prepared domain deletion mutants, analyzed the motility and flagellation of those mutants, and observed the structures of their basal bodies. Now the role of each domain is revealed.

FlgT-N is essential for the H-ring formation. FlgT-N is composed of only 83 amino acid residues, which is smaller than the N-terminal domain of MotY, a T-ring component. The size of FlgT-N is too small to fill the density corresponding to the whole H ring. Moreover, most of the H ring seems to be embedded in the outer membrane covering the L ring, but FlgT is a soluble periplasmic protein. Therefore, some other components should be present in the H ring, at least, in the outer-membrane region. These facts suggest that FlgT-N is a scaffold for the H-ring formation. It is also possible that FlgT-N is a periplasmic component of the H ring.

FlgT-M is important for the stable T-ring formation, which is essential for the stator assembly of Vibrio. The amounts of MotX and MotY in the basal body fraction of mutant cells expressing FlgT-NM or FlgT-MC were almost the same as those in cells expressing the full-length FlgT (Fig. 5). In addition, electron microscopic observations revealed that the basal bodies of FlgT-NM and FlgT-MC have the T ring (Fig. 4). Thus, FlgT-M is directly involved in the T-ring formation. It is known that a small number of ΔflgT mutant cells can swim, whereas ΔmotY mutant cells cannot. Moreover, a small amount of MotY and MotX is contained in the basal body from the ΔflgT mutant (23). These facts indicate that MotY is able to associate with the basal body without FlgT, although the interaction between MotY and the basal body is unstable. FlgT-M is thought to stabilize this interaction and helps MotX and MotY to form a rigid T-ring structure. Probably, the T ring is fixed only when it is attached to the basal body with the help of FlgT-M. Another role of FlgT-M is suggested by the electron microscopic study. Electron micrographs of the basal body of the FlgT-NC mutant seem very similar to that of ΔflgT mutant (Fig. 4), suggesting that FlgT is assembled around the basal body mainly through FlgT-M.

Fig. 5.

Characterization of domain deletion mutant variants of FlgT. TH7(ΔflgT flhG) cells harboring the plasmids [1, pTH105 (FlgT-NMC+His6); 2, pLSK9-his (FlgT-NM+His6); 3, pLSK10-his (FlgT-MC+His6); or 4, pLSK11-his (FlgT-NC+His6)] were grown, and their hook-basal bodies (HBB) were isolated according to Materials and Methods. The protein samples were subjected to SDS/PAGE, followed by immunoblotting using (A) anti-FlgT, (B) anti-FliF, (C) anti-MotX, and (D) anti-MotY antibodies. The asterisk represents the attached hexahistidine tag.

Compared with FlgT-N or FlgT-M, the role of FlgT-C is relatively minor. FlgT-NM recovered the motility to a level ∼80% of the wild type (Table 1), suggesting that FlgT-C does not significantly contribute to the motility. Considering the distortion of the H ring of the FlgT-NM mutant (Fig. 4B), FlgT-C may be a part of the H ring or may stabilize the H-ring structure. The structure of FlgT-C resembles that of the N-terminal domain of the F1 α/β-subunit or FliI (Fig. 2D). These proteins form a ring structure through the tight interaction between the tandemly arranged β-barrel domains by forming intersubunit β-sheets. The FlgT molecules assembled around the basal body might be stabilized by similar interaction through FlgT-C.

The T and H rings are unique components of the Vibrio motor. These extra components are thought to be required for fixing the stator units withstanding approximately 50,000 rpm rotation. By considering the results of this study with those in previous studies, we propose a model for the basal body ring formation of the Na+-driven motor (Fig. 6). FlgT assembles around the LP ring through FlgT-M and is stabilized by FlgT-C. FlgT-N forms a part of the periplasmic region of the H ring and acts as a scaffold for the construction of the outer part of the H ring. Unknown H-ring components assemble around the LP ring to form the complete H ring. FlgO and FlgP might be potential candidates as the outer part of the H ring because they are outer membrane proteins (26). The MotX–MotY complex then associates with the basal body through MotY-N to form the T ring. The T ring is stabilized and fixed with the help of FlgT-M. This fact may imply that FlgT acts as a connection center between the LP ring, the T ring, and the outer membrane part of the H ring. Finally, the stator units composed of PomA and PomB target to the T ring and assemble around the rotor.

Fig. 6.

A plausible model for the basal body ring formation of the Na+-driven motor. The H ring is constructed by FlgT and/or other components, then MotX and MotY assemble to the basal body with the help of FlgT-M and form the T ring. The stator units assemble around the rotor through the T ring, resulting in the formation of a functional motor. Without FlgT, no H ring is constructed. MotX and MotY may occasionally attach to the basal body to form the T ring; however, the ring is unstable and easy to break up. As a result, the stator unit is not properly incorporated into the motor. FlgT and MotY are shown as space-filling models colored cyan for FlgT-N, green for FlgT-M, magenta for FlgT-C, violet for MotY-N, and yellow for MotY-C.

The structural similarity between FlgT-M and the N-terminal domain of TolB (Fig. 2C) supports an evolutionary relationship between the flagellar motor system and the Tol-Pal system. The Tol-Pal system is required for outer membrane integrity, cell division, and resistance to antibiotics in Gram-negative bacteria. The Tol-Pal system consists of three cytoplasmic membrane proteins, TolA, TolQ, and TolR, and two periplasmic proteins, TolB and Pal. The N-terminal domain of TolB interacts with the periplasmic domain of TolA and forms an ion-conducting complex with TolQ/R (27–29). TolQ/R have sequence homology with PomA/B, and both conduct the coupling ion for their function (30, 31). The C-terminal domains of MotY and PomB show structural and functional similarities with Pal (21, 32). Although the function of these two systems is quite different, there might be common mechanisms for their assembly and/or function.

Material and Methods

Bacterial Strain, Plasmids, and Growth Conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1. V. alginolyticus was cultured in VC medium [0.5% (wt/vol) bactotryptone, 0.5% (wt/vol) yeast extract, 0.4% (wt/vol) K2HPO4, 3% (wt/vol) NaCl, and 0.2% (wt/vol) glucose] or in VPG500 medium [1% (wt/vol) bactotryptone, 0.4% (wt/vol) K2HPO4, 500 mM NaCl, and 0.5% (wt/vol) glycerol] at 30 °C. E. coli was cultured in LB broth [1% (wt/vol) bactotryptone, 0.5% (wt/vol) yeast extract, and 0.5% (wt/vol) NaCl] or in Le Master medium for Se-Met FlgT-His6 [Solution-A: 0.5 g of alanine, 0.58 g of arginine, 0.4 g of aspartic acid, 0.033 g of L-cysteine, 0.75 g of glutamic acid (Na), 0.333 g of glutamine, 0.54 g of glycine, 0.06 g of histidine, 0.23 g of isoleucine, 0.23 g of leucine, 0.42 g of lysine-HCl, 0.133 g of phenylalanine, 0.1 g of proline, 2.083 g of L-serine, 0.23 g of threonine, 0.17 g of tyrosine, 0.23 g of valine, 0.5 g of adenine, 0.67 g of guanosine, 0.17 g of thymine, 0.5 g of uracil, 1.5 g of sodium acetate, 1.5 g of succinic acid, 0.75 g of ammonium Cl, 0.85 g of sodium hydroxide, and 10.5 g of dibasic K2HPO4 were suspended in 500 mL of water, then autoclaved. Solution-B: 5.0 g of D-glucose, 0.125 g of MgSO4-7H2O, 2.1 mg of FeSO4, 4 μL of H2SO4, and 2.5 mg of thiamine were solubilized in 25 mL of water, then filtered. Four hundred eighty milliliters of Solution-A, 24 mL of Solution-B, and 25 mg of Se-methionine were mixed] (33). Chloramphenicol was added to a final concentration of 25 μg/mL for E. coli. Kanamycin was added to a final concentration of 100 μg/mL for V. alginolyticus and 50 μg/mL for E. coli. Ampicillin was added to a final concentration of 50 μg/mL for E. coli.

Purification and Crystallization of FlgT.

Details of the expression and purification of FlgT-His6 were described (23). B834(DE3)/pLysS cells were used for expression of Se-Met labeled FlgT-His6. Crystallization of FlgT was performed by the sitting-drop vapor-diffusion technique. Crystals suitable for X-ray studies were grown from drops prepared by mixing 1 μL protein solution (2.7 mg⋅mL−1) containing 20 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 7.8 and 300 mM NaCl with 1 μL of reservoir solution containing 0.1 M N-cyclohexyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid-NaOH at pH 9.5, 21–23% (vol/vol) PEG 3350 at 293 K. Monoclinic P21 crystals of FlgT with unit cell dimensions a = 46.1 Å, b = 34.1 Å, c = 112.2 Å and β = 101.6° appeared within one week and grew to typical dimensions of 0.05 × 0.2 × 0.5 mm. Osmium derivative crystals were prepared by soaking the crystals in a reservoir solution containing K2OsCl6 at 50% saturation for 4 h. SeMet-labeled crystals were grown in the same conditions used for the native crystals.

Data Collection and Structure Determination.

X-ray diffraction data were collected at the synchrotron beamlines BL38B1, BL32XU, and BL41XU in SPring-8 with the approval of the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (proposal nos. 2010B1013 and 2010B1901). Crystals were soaked in a cryo-protectant solution containing 10% (vol/vol) 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD) and 90% (vol/vol) of the reservoir solution for a few seconds and then were immediately transferred into liquid nitrogen for freezing. The X-ray diffraction data were collected under helium gas flow at 40 K for Os-derivative crystals and under nitrogen gas flow at 95 K for other crystals. The statistics of the diffraction data are summarized in Table S2. The diffraction data were processed with MOSFLM (34) and were scaled with SCALA (35). Phase calculation was performed by using Phenix (36). The best electron density map was calculated by combining the single-wavelength anomalous diffraction phase of the Se-Met derivative and that of the Os derivative, followed by density modification with DM (35). The atomic model was constructed with COOT (37) and refined against the Se-Met derivative data to 2.0 Å with CNS (38). During the refinement process, iterative manual modification was performed by using “omit map.” The refinement R factor and the free R factor were converged to 20.6% and 23.4%, respectively. The Ramachandran plot indicated that 92.2% and 8.0% residues were located in the most favorable and allowed region, respectively. Structural refinement statistics are summarized in Table S3.

Motility Assay.

A 1-μL aliquot of an overnight culture was spotted onto a VPG500 semisolid agar plate [1% (wt/vol) bactotryptone, 0.4% (wt/vol) K2HPO4, 500 mM NaCl, 0.5% (wt/vol) glycerol, and 0.25% (wt/vol) bactoagar] and incubated at 30 °C for the desired time.

Immunoblotting.

Antisera against MotX (MotXB0080), MotY (MotYB0079), FlgT (VA15390B0472), and FliF (FliFB0424) were prepared as described (23, 39). HRP-linked goat anti-rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz) was used as the secondary antibody.

Isolation of Flagellar Basal Bodies.

The isolation of the flagellar basal bodies was carried out as described (20, 23).

Electron Microscopy.

The isolated flagellar basal body was negatively stained with 2% (wt/vol) phosphotungstic acid at pH 7.4 and was observed with a JEM-2010 electron microscope (JEOL).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Hirata and K. Hasegawa at SPring-8 for technical help with use of beamlines. This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan Grants 18074006 and 23115008 (to K.I.); Japan Science and Technology Corporation Grants 23247024 (to M.H.) and 24657087 (to S.K.); and a grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (to H.T.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 3W1E).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1222655110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Berg HC. The rotary motor of bacterial flagella. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:19–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terashima H, Kojima S, Homma M. Flagellar motility in bacteria structure and function of flagellar motor. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2008;270:39–85. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(08)01402-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minamino T, Imada K, Namba K. Molecular motors of the bacterial flagella. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18(6):693–701. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kojima S, Blair DF. The bacterial flagellar motor: Structure and function of a complex molecular machine. Int Rev Cytol. 2004;233:93–134. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(04)33003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yorimitsu T, Homma M. Na+-driven flagellar motor of Vibrio. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1505(1):82–93. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00279-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato K, Homma M. Functional reconstitution of the Na+-driven polar flagellar motor component of Vibrio alginolyticus. J Biol Chem. 2000a;275(8):5718–5722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sato K, Homma M. Multimeric structure of PomA, a component of the Na+-driven polar flagellar motor of Vibrio alginolyticus. J Biol Chem. 2000b;275(26):20223–20228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002236200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kojima S, Blair DF. Solubilization and purification of the MotA/MotB complex of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2004;43(1):26–34. doi: 10.1021/bi035405l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asai Y, Kawagishi I, Sockett RE, Homma M. Hybrid motor with H+- and Na+-driven components can rotate Vibrio polar flagella by using sodium ions. J Bacteriol. 1999;181(20):6332–6338. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6332-6338.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blair DF, Berg HC. The MotA protein of E. coli is a proton-conducting component of the flagellar motor. Cell. 1990;60(3):439–449. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90595-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stolz B, Berg HC. Evidence for interactions between MotA and MotB, torque-generating elements of the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173(21):7033–7037. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.21.7033-7037.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan S, Dapice M, Reese TS. Effects of mot gene expression on the structure of the flagellar motor. J Mol Biol. 1988;202(3):575–584. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sowa Y, et al. Direct observation of steps in rotation of the bacterial flagellar motor. Nature. 2005;437(7060):916–919. doi: 10.1038/nature04003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leake MC, et al. Stoichiometry and turnover in single, functioning membrane protein complexes. Nature. 2006;443(7109):355–358. doi: 10.1038/nature05135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reid SW, et al. The maximum number of torque-generating units in the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli is at least 11. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(21):8066–8071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509932103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Francis NR, Sosinsky GE, Thomas D, DeRosier DJ. Isolation, characterization and structure of bacterial flagellar motors containing the switch complex. J Mol Biol. 1994;235(4):1261–1270. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones CJ, Homma M, Macnab RM. Identification of proteins of the outer (L and P) rings of the flagellar basal body of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169(4):1489–1492. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.4.1489-1492.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Homma M, Aizawa S-I, Dean GE, Macnab RM. Identification of the M-ring protein of the flagellar motor of Salmonella typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84(21):7483–7487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen S, et al. Structural diversity of bacterial flagellar motors. EMBO J. 2011;30(14):2972–2981. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terashima H, Fukuoka H, Yakushi T, Kojima S, Homma M. The Vibrio motor proteins, MotX and MotY, are associated with the basal body of Na-driven flagella and required for stator formation. Mol Microbiol. 2006;62(4):1170–1180. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kojima S, et al. Insights into the stator assembly of the Vibrio flagellar motor from the crystal structure of MotY. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(22):7696–7701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800308105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okabe M, Yakushi T, Homma M. Interactions of MotX with MotY and with the PomA/PomB sodium ion channel complex of the Vibrio alginolyticus polar flagellum. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(27):25659–25664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500263200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terashima H, Koike M, Kojima S, Homma M. The flagellar basal body-associated protein FlgT is essential for a novel ring structure in the sodium-driven Vibrio motor. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(21):5609–5615. doi: 10.1128/JB.00720-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez RM, Jude BA, Kirn TJ, Skorupski K, Taylor RK. Role of FlgT in anchoring the flagellum of Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(8):2085–2092. doi: 10.1128/JB.01562-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abergel C, et al. Structure of the Escherichia coli TolB protein determined by MAD methods at 1.95 A resolution. Structure. 1999;7(10):1291–1300. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)80062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez RM, Dharmasena MN, Kirn TJ, Taylor RK. Characterization of two outer membrane proteins, FlgO and FlgP, that influence Vibrio cholerae motility. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(18):5669–5679. doi: 10.1128/JB.00632-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dubuisson JF, Vianney A, Lazzaroni JC. Mutational analysis of the TolA C-terminal domain of Escherichia coli and genetic evidence for an interaction between TolA and TolB. J Bacteriol. 2002;184(16):4620–4625. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.16.4620-4625.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walburger A, Lazdunski C, Corda Y. The Tol/Pal system function requires an interaction between the C-terminal domain of TolA and the N-terminal domain of TolB. Mol Microbiol. 2002;44(3):695–708. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cascales E, Gavioli M, Sturgis JN, Lloubès R. Proton motive force drives the interaction of the inner membrane TolA and outer membrane pal proteins in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2000;38(4):904–915. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cascales E, Lloubès R, Sturgis JN. The TolQ-TolR proteins energize TolA and share homologies with the flagellar motor proteins MotA-MotB. Mol Microbiol. 2001;42(3):795–807. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goemaere EL, Cascales E, Lloubès R. Mutational analyses define helix organization and key residues of a bacterial membrane energy-transducing complex. J Mol Biol. 2007;366(5):1424–1436. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kojima S, et al. Stator assembly and activation mechanism of the flagellar motor by the periplasmic region of MotB. Mol Microbiol. 2009;73(4):710–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.LeMaster DM, Richards FM. 1H-15N heteronuclear NMR studies of Escherichia coli thioredoxin in samples isotopically labeled by residue type. Biochemistry. 1985;24(25):7263–7268. doi: 10.1021/bi00346a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leslie AGW. CCP4+ESF-EACMB. Newslett Protein Crystallogr. 1992;26:27–33. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67(Pt 4):235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: Building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58(Pt 11):1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60(Pt 12 Pt 1):2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brünger AT, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54(Pt 5):905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yagasaki J, Okabe M, Kurebayashi R, Yakushi T, Homma M. Roles of the intramolecular disulfide bridge in MotX and MotY, the specific proteins for sodium-driven motors in Vibrio spp. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(14):5308–5314. doi: 10.1128/JB.00187-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li N, Kojima S, Homma M. Characterization of the periplasmic region of PomB, a Na+-driven flagellar stator protein in Vibrio alginolyticus. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(15):3773–3784. doi: 10.1128/JB.00113-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.