Abstract

During visual exploration, saccadic eye movements scan the scene for objects of interest. During attempted fixation, the eyes are relatively still but often produce microsaccades. Saccadic rates during exploration are higher than those of microsaccades during fixation, reinforcing the classic view that exploration and fixation are two distinct oculomotor behaviors. An alternative model is that fixation and exploration are not dichotomous, but are instead two extremes of a functional continuum. Here, we measured the eye movements of human observers as they either fixed their gaze on a small spot or scanned natural scenes of varying sizes. As scene size diminished, so did saccade rates, until they were continuous with microsaccadic rates during fixation. Other saccadic properties varied as function of image size as well, forming a continuum with microsaccadic parameters during fixation. This saccadic continuum extended to nonrestrictive, ecological viewing conditions that allowed all types of saccades and fixation positions. Eye movement simulations moreover showed that a single model of oculomotor behavior can explain the saccadic continuum from exploration to fixation, for images of all sizes. These findings challenge the view that exploration and fixation are dichotomous, suggesting instead that visual fixation is functionally equivalent to visual exploration on a spatially focused scale.

Keywords: free-viewing, fixational eye movements, miniature eye movements, fixational saccades, natural images

Classic and current vision studies distinguish between visual exploration, characterized by the alternation of saccades and brief fixation periods, and attempted visual fixation, where subjects maintain relative gaze stability despite continuous but minute fixational eye movements (i.e., microsaccades, slow drift, and oculomotor tremor) (1–7). The theoretical separation between exploratory gaze shifts and attempted fixation dates back to the discovery of fixational eye movements in the early 1900s (2–4), and remains central to contemporary discourse in visual, cognitive, and oculomotor research (8). However, mounting evidence in support of a common generator for both exploratory saccades and fixational microsaccades (refs. 9–12 but see ref. 13) brings into question whether such a dichotomy is justified. Instead, it may be that saccades and microsaccades form an oculomotor continuum along the entire spectrum of exploratory scales, with classical exploratory saccades at one end and classical fixational microsaccades at the other end. In that case, it might be baseless to distinguish between fixational and exploratory behaviors. Recent studies have identified abnormal dynamics of saccades and microsaccades as potential diagnostic markers of neurological disease (14–16); thus, the frame of reference proposed here may have important clinical implications concerning the role of the affected brain centers in the patients’ oculomotor behavior.

To establish such a framework, one must first reconcile any known discrepancy between the dynamics of saccades during exploration and those of microsaccades during fixation. Saccades occur at an approximate rate of three per second during exploration, whereas microsaccades occur about once a second during fixation (5, 8, 17). This difference, unexplained by current models of visual and oculomotor function, is in conflict with the physiological and behavioral evidence supporting a common generator for saccades and microsaccades (8–10, 12, 18), and reinforces the traditional view that exploration and fixation are two distinct oculomotor behaviors (3, 7).

One solution to this paradox could be that exploration and fixation are not opposing behaviors, but form a functional continuum in which saccades scan visual scenes of any and all sizes, no matter how small. That is, fixation may serve to scan minute regions of visual space, just as classical exploration serves to scan larger visual regions. If this idea is correct, saccadic rates should not only decrease as the size of the field of exploration decreases, but also fall on a continuum with classical exploratory saccades at one end and classical fixational saccades (i.e., microsaccades) at the other end. Other saccadic properties should vary as function of image size as well, forming a continuum with microsaccadic parameters during fixation.

Results

We tracked the eye movements of human participants while they fixated a small dot or freely explored natural images and blank scenes of varying sizes (see Materials and Methods for details).

Experiment 1.

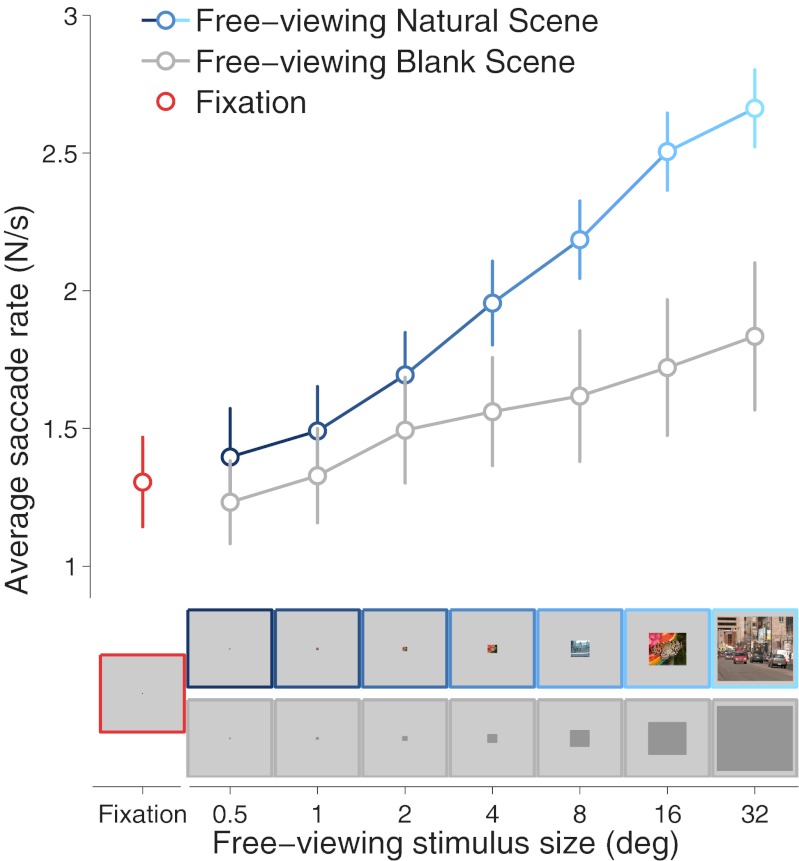

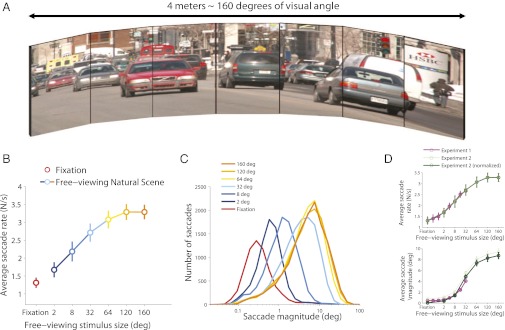

Saccadic rates diminished with decreasing image size, both for natural scenes (r = 0.99) and for blank scenes (r = 0.99) (Fig. 1). The rates of microsaccades produced during visual fixation were equivalent to the rates of saccades produced during the visual exploration of the smallest (natural, P = 0.24, and blank, P = 0.57) scenes, signaling a continuum of saccade production from exploration to fixation (Fig. 1). Blank scenes resulted in reduced saccadic rates at all image sizes (analysis of covariance, P = 0.000001), as expected from previous results (8). The saccadic continuum from exploration to fixation was consistent across individual subjects. No previous study has linked the diminishing rates of saccades generated during the exploration of shrinking images to those of microsaccades during fixation (19, 20).

Fig. 1.

A saccadic continuum from exploration to fixation. (Upper) Average saccade rates for the different experimental conditions. Error bars represent SEM across subjects. (Lower) Examples of Natural Scene and Blank Scene stimuli, proportionally scaled down from the sizes presented in the experiment.

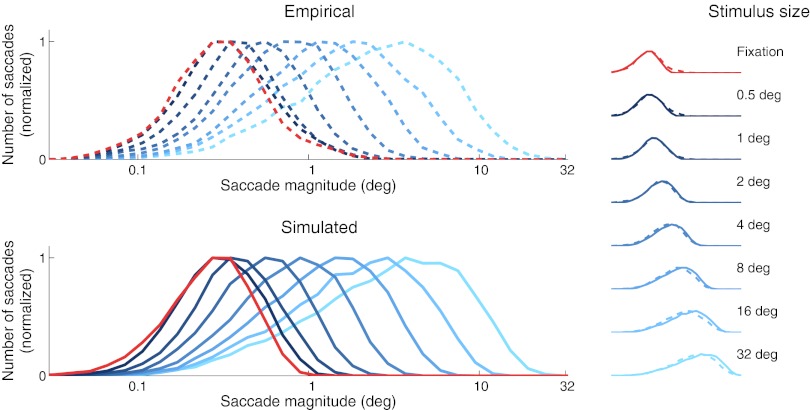

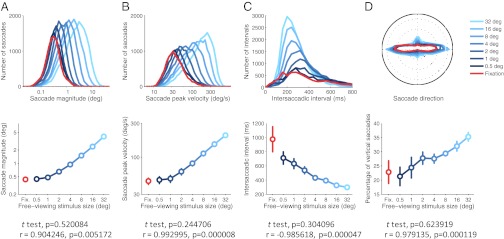

The saccadic continuum was not limited to rate, but extended to other saccadic properties such as magnitude, velocity, direction, and intersaccadic interval. That is, as visual scenes decreased in size, saccades became smaller, slower, and sparser (Fig. 2A, B, and C, respectively) and took on trajectories that were more horizontal in direction (Fig. 2D). The distributions of these parameters did not change in shape abruptly, but shifted continuously as the images shrunk (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The saccadic continuum from exploration to fixation extends to saccade magnitude, peak velocity, intersaccadic interval, and direction. (A–D) Saccadic parameters in relation to scene size. (Upper) Distributions of saccadic parameters do not change in shape with decreasing image sizes, but merely shift continuously. Data from the Natural Scene condition (plots) and Blank Scene condition were equivalent. (Lower) Average saccadic parameters during fixation were indistinguishable from those during free-viewing of the smallest scene (t test P values indicated below each plot). Free-viewing regression slopes were significantly different from zero for each saccadic parameter (correlation coefficients and P values for the regression of the parameter and the logarithm of stimulus size indicated below each plot). Error bars represent SEM across subjects.

Statistical testing rejected the possibility of a bimodal distribution of saccades and microsaccades underlying the saccadic continuum apparent in Figs. 1 and 2, for all image sizes (Hartigan dip test P > 0.05) (21) (Fig. 2A). To further test the hypothesis of a bimodal distribution underlying microsaccade and saccade generation, we implemented a model of oculomotor behavior derived from known human oculomotor function (22, 23). We generated random scanpaths within each image size (see Materials and Methods for details) and obtained simulated saccade magnitude distributions. Fig. 3 compares the simulated and empirical saccade magnitude distributions. The model provides a good fit of our data (R-squared = 0.9) and captures the main characteristics of the empirical saccadic magnitude distributions for images of all sizes. Thus, the eye movement simulation results indicate that a single model of oculomotor behavior can explain a saccadic continuum from exploration to fixation, for images of all sizes.

Fig. 3.

Empirical and simulated saccade magnitude distributions. Dashed lines show the empirical distributions (same data as in Fig. 2A) and solid lines the simulated ones. Distributions are normalized by the maximum value to facilitate direct comparison.

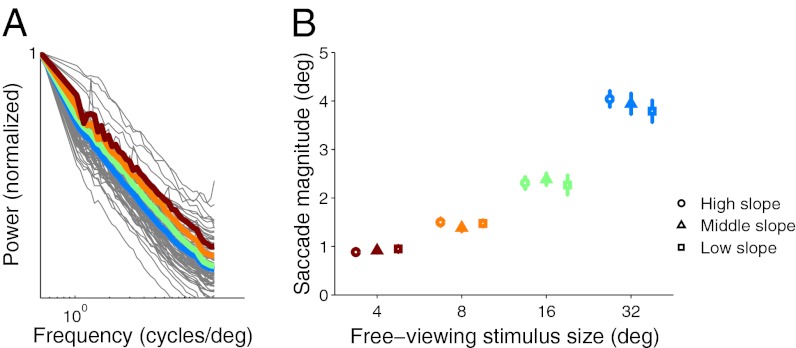

The shift in saccadic magnitudes was not due to differences in the spatial frequencies available as the natural scenes decreased in size. That is, the reduction in saccadic magnitudes with natural scenes of diminishing size is a function of exploration area, and not of spatial frequency content (Fig. 4; repeated measures ANOVA, P = 0.9).

Fig. 4.

Spatial frequency content does not explain decreased saccade magnitudes for natural scenes of diminishing sizes. (A) Each gray line represents the spatial frequency spectrum (rotational average) of each natural scene at the largest size (32°). Color lines indicate the average of the spectrum of all of the images at four different sizes (32°, 16°, 8°, and 4°). The effect of stimulus size on the slope of the spectra is noticeable. The slope variability at the highest stimulus size (32°) encompasses the average slopes from stimuli sizes 4–32°. (B) Images were sorted by spectrum slope (high, middle, and low) and then divided in three groups of 28 images each. Saccade magnitude changes with stimulus size at all spatial frequencies, but it does not change with spatial frequency for any image size. The smallest image sizes (2°, 1°, and 0.5°) were not included in this analysis due to the difficulty of calculating the corresponding spectra. Error bars represent SEM across subjects.

Experiment 2.

Here, a different set of subjects viewed a large visual display that permitted the presentation of greater sized images than previously tested (i.e., up to 160 degrees wide, thus virtually encompassing a subject’s visual field in its entirety) (Fig. 5A). Viewing conditions were moreover unrestricted in that participants could move their eyes and heads naturally as they explored the images (whereas in experiment 1 their heads were held in place with a forehead/chin rest; see Materials and Methods for details). As in experiment 1, saccade rates and magnitudes increased continuously with image size, reaching a ceiling (i.e., saturation) effect for images larger than 100 degrees (Fig. 5 B and C). Indeed, saccade rates and magnitudes were equivalent for the two largest image sizes tested (paired t test, P = 0.99 and P = 0.07, respectively), indicating that further unrestricted viewing conditions should not alter the present results.

Fig. 5.

The saccadic continuum extends to nonrestrictive viewing conditions. (A) Seven adjacent monitors formed a very wide screen display, encompassing nearly all of a subject’s visual field. (B) Saccadic rate continuum from exploration to fixation. Error bars represent SEM across subjects. (C) Saccadic magnitude continuum from exploration to fixation. (D) Comparison of saccadic rates (Upper) and magnitudes (Lower) in experiments 1 and 2. Different sets of subjects participated in experiments 1 and 2. Some methodological aspects moreover differed between the two experiments, such as the type of display (see Materials and Methods for details). Thus, to compare the shape of the curves from the two experiments, we normalized the data from experiment 2 using experiment 1 as reference (i.e., we subtracted a constant value from all of the data points from experiment 2, so that the average saccadic rates or magnitudes corresponding to the four common image sizes tested in the two experiments were equivalent). Both experiments produced the same saccadic continuum from fixation to exploration, although experiment 2 had an expanded range.

Although the results of both experiments were equivalent for the range of image sizes where they overlapped (Fig. 5D), experiment 2 provided an expanded and less restricted measure of saccadic dynamics than experiment 1. Thus, the results of experiment 2 confirm that the saccadic continuum from fixation to exploration applies to images of all sizes, even the very largest ones, in nonrestrictive viewing conditions allowing all types of saccades and fixation positions.

Discussion

Our results suggest that the human oculomotor system engages in continuous exploration while observing objects of all dimensions, with the size of the area of exploration determining saccadic parameters such as rate and magnitude. Simply put, when we observe small things (i.e., minute scenes, object features, fixation targets), our oculomotor system scans them with small and infrequent saccades, whereas if we look at big things our oculomotor system scans them with larger, more frequent saccades. The smaller the scene to be scanned, the smaller and less frequent saccades (and microsaccades) will be. In other words, saccadic and microsaccadic rates and magnitudes vary along a continuum as a function of the size of the scene to be scanned.

This theoretical framework may moreover explain decreases in microsaccade rates during high-acuity tasks (24), if accompanied by a de facto reduction in the area of active exploration during performance.

The finding that saccadic magnitudes decrease with scene size is easier to explain, and altogether less surprising, than the parallel decrement in saccadic rates. Why should diminishing image sizes lead to progressively lower rates of saccades? Several mutually compatible saccadic and microsaccadic properties may account for this rate reduction: (i) saccadic latencies to recently attended locations are longer than latencies to locations not yet attended. This phenomenon, known as inhibition of return (25), reportedly affects microsaccade dynamics (26). Because the exploration of a small area is more likely to result in a saccade to a previously visited target, smaller image sizes may result in longer saccadic latencies, and thus lower saccadic rates. (ii) Very small saccades have longer latencies than large saccades (27). Because very small saccades are more prevalent in small than in large images, decreasing image sizes may result in longer average saccadic latencies, and thus lower saccade rates. (iii) Lack of visual content may explain why saccadic (and microsaccadic) rates are lower during the exploration of a blank scene than during that of a natural scene (8) (Fig. 1). Because limiting the area of exploration reduces the amount of visual content, decreasing image sizes may result in progressively lower saccadic rates. Also, the fovea, the high-resolution portion of the central visual field, is fixed in size irrespective of task. Thus, sampling small spatial areas with our high-acuity fovea does not require as many eye movements as exploring larger areas of visual space.

The hypothesis that lack of visual content is responsible for the reduction of saccadic rates during the exploration of blank versus natural scenes is consistent with the observation of higher saccadic rates during the attempted fixation of large versus small targets (28, 29). Because a large fixation target has no visual content within the local area of fixation/exploration, one should expect lower saccade rates in such a scenario.

Critical structures in the brainstem involved with generation of saccades are also related to microsaccade generation. Van Gisbergen and coworkers showed that the activity of excitatory burst neurons in the pontine reticular formation encodes microsaccades and saccades (30). No studies to date have conducted recordings from inhibitory burst neurons in connection with microsaccades, however (31). Omnipause neurons in the raphe stop firing during both saccades and microsaccades (32, 33), and population activity in the superior colliculus map generates microsaccades and saccades in equivalent fashion (9, 34). The hypothesis of a fixation–exploration continuum reconciles the dynamics of oculomotor behavior with the proposal of a common microsaccade–saccade generator (9–11), and it moreover elucidates previously unexplained results concerning the precise relationship between saccades and microsaccades, such as the finding that subjects can make voluntary saccades that are as small as fixational microsaccades (12). Thus, our results eliminate the remaining barrier to consolidating saccades and microsaccades as a single type of eye movement.

Saccadic eye movements are known to play multiple roles in vision—that is, they foveate high-interest targets, correct gaze errors, and search and integrate general information about the environment to stitch together the perception of a scene (7, 35). Likewise, many microsaccade functions have been proposed (31), including the prevention of visual fading and the restoration of faded visual targets (36–38), the control of fixation position (3, 39), and improved visual performance in high-acuity tasks (24, 40). Our results point to a similarity in function for microsaccades and saccades, and suggest that all of the saccadic roles may be common to microsaccades, including the scanning and exploration of visual objects and scenes traditionally ascribed to (large) saccades. We note that even forming a continuum, saccades and microsaccades may have additional task-dependent roles in specific situations. For instance, saccades and large microsaccades counteract visual fading with higher efficacy than the smallest microsaccades (38).

Previous speculations about the scanning behavior of microsaccades during fixation lacked empirical support. The technical limitations that stood in the way of obtaining such evidence included the lack of a system to monitor eye position “without attachments to the eye” and the inability to have participants “inspect visual scenes as they normally do in everyday life” (ref. 12, p. 814). The present experiments overcome such obstacles to show that microsaccades during attempted fixation and saccades during free exploration share equivalent dynamics, even in unrestricted viewing conditions, where the area of exploration occupies the visual field in its entirety, and observers are able to move their heads, eyes, and gaze position at will.

To sum up, the present results unify classically disparate fixation and exploration behaviors as the scanning of the visual world along a common continuum of scale, in which previously unexplained differences between the dynamics of microsaccades and saccades are elucidated by the differing magnitudes of the objects and scenes viewed. Future research should determine whether information acquisition by microsaccades during fixation is comparable to that of saccades during exploration (i.e., free-viewing) of very small objects.

Materials and Methods

Experiment 1.

Ten subjects (three females) with normal or corrected-to-normal vision participated in four experimental sessions of ∼60 min each, under the approval of the Barrow Neurological Institute’s institutional review board (IRB). Written informed consent was obtained from each subject.

Subjects rested their heads on a chin-rest, 57 cm from a Barco Reference Calibrator V monitor, 75 Hz refresh rate. Eye position was acquired in both eyes at 500 samples/s (EyeLink 1000, SR Research). Saccade identification was as in refs. 8 and 41.

We tested one fixation and 14 exploration (i.e., free-viewing) experimental conditions. Half of the free-viewing conditions presented a natural image and the other half a 60% gray rectangle (Fig. 1), on a 50% gray background. The width of the image/rectangle was 32°, 16°, 8°, 4°, 2°, 1°, or 0.5° (the heights were three-fourths of the widths). In the fixation condition, subjects fixated a central red dot (0.1° wide). In the free-viewing conditions, subjects were instructed to move their eyes freely within the image (eye movements exceeding the image area were recorded). Each 30-s trial was preceded by an instructions screen indicating the task to be performed.

We presented each free-viewing condition 12 times and the fixation condition 24 times (192 trials total, pseudorandomly interleaved). Each natural image trial included a different image from the McGill Calibrated Color Image Database (42).

Experiment 2.

Six subjects (two females, no overlap with subjects in experiment 1) with normal or corrected-to-normal vision participated in one experimental session of ∼60 min, under the approval of the Barrow Neurological Institute’s IRB. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject.

Subjects sat ∼57 cm from a large display composed of seven contiguous monitors, each of which was 108 cm tall and 57 cm wide. The angle between adjacent monitors was 5°. This setup allowed the presentation of greater image sizes than in experiment 1 (i.e., up to 160 degrees wide, thus virtually encompassing a subject’s visual field in its entirety) (Fig. 5A).

To conduct this experiment in unconstrained viewing conditions, we measured the participants’ eye-in-head movements, in both eyes, with a helmet-mounted system at 500 samples/s (EyeLink II, SR Research). Once calibration was complete, participants could move their eyes and heads naturally as they explored the images. Saccade identification was as in experiment 1.

The very large sizes of the images presented precluded the tracking of head movements (EyeLink II’s head tracking capabilities are limited to ±30°), but this limitation did not affect the precise measurement of eye-in-head movements or the subsequent accurate calculations of saccade rates and magnitudes. We also note that the results and conclusions from experiment 2 do not rely on, or make claims about, the subjects’ gaze positions with respect to the image.

We tested one fixation and six exploration (i.e., free-viewing) experimental conditions. In the fixation condition, subjects fixated a central red dot (0.1° wide). In the free-viewing conditions, we presented a natural image and subjects moved their eyes and heads freely to explore the scene. The width of the image was 160°, 120°, 64°, 32°, 8°, or 2° (the heights were three-fourths of the widths for the images ≤64°, and 94° for the images of 160° and 120°). The subjects were instructed solely to explore the images at will (whereas in experiment 1, participants’ instructions required them to move their eyes freely within the image). Each 30-s trial was preceded by an instructions screen indicating the task to be performed.

We presented each condition nine times (63 trials total, pseudorandomly interleaved). Natural images were taken from the McGill Calibrated Color Image Database (42).

Modeling of Oculomotor Behavior.

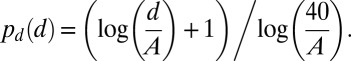

We implemented a model of oculomotor behavior that allowed us to obtain simulated saccade magnitude distributions by creating a sequence of 20,000 randomly generated saccades for each image size. In each step of the simulation we added a new saccade to the sequence, taking as starting point the end point of the previous saccade and selecting a new random end point. The probability distribution of saccadic end points was derived from known properties of human oculomotor behavior, as follows:

First, points near the center of the image were chosen with higher likelihood than points farther from the center, following from a robust phenomenon known as central bias (23). Thus, the probability of an end point varied linearly with the distance to the center of the image, being maximal at center and zero at the edges. A margin of error of 0.5° around each image accounted for inaccurate fixation at the edge of the image.

Second, small saccades have a higher likelihood of occurrence than large saccades (22, 23). Further, neural activity maps in the superior colliculus are responsible, at least in part, for both saccadic and microsaccadic targeting (34). In our simulations, a given end point’s probability of selection decreased with the distance to the starting point of the saccade (d), according to the superior colliculus retinal magnification function (from ref. 43):

|

Third, gaze position errors of minute magnitudes are less likely to trigger correcting saccades (15). Thus, we used a second function to reduce the probability of the very smallest saccades:

The values of the two free parameters (A and B above) that fit best the empirical distributions determined the best fit of our model. We used the same A = 0.3 and B = 0.15 values to fit the distributions for all image sizes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrew Danielson, Behrooz Kousari, Peter Wettenstein, and Gabriel Arnn for technical assistance and Hector Rieiro, Dr. Xoana G. Troncoso, Dr. Leandro Di Stasi, and Dr. Michael B. McCamy for their comments. This work was supported by the Barrow Neurological Foundation (to S.L.M. and S.M.-C.) and National Science Foundation Awards 0852636 and 1153786 (to S.M.-C.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Yarbus AL. Movements of the Eyes. New York: Plenum; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dodge R. An experimental study of visual fixation. The Psychological Review: Monograph Supplements. 1907;8(4):i–95. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ditchburn RW, Ginsborg BL. Involuntary eye movements during fixation. J Physiol. 1953;119(1):1–17. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1953.sp004824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ratliff F, Riggs LA. Involuntary motions of the eye during monocular fixation. J Exp Psychol. 1950;40(6):687–701. doi: 10.1037/h0057754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rolfs M. Microsaccades: Small steps on a long way. Vision Res. 2009;49(20):2415–2441. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barlow HB. Eye movements during fixation. J Physiol. 1952;116(3):290–306. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yarbus AL. Eye Movements and Vision. New York: Plenum; 1967. Eye movements during fixation on stationary objects, in; pp. 103–128. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otero-Millan J, Troncoso XG, Macknik SL, Serrano-Pedraza I, Martinez-Conde S. Saccades and microsaccades during visual fixation, exploration, and search: Foundations for a common saccadic generator. J Vis. 2008;8(14):21.1–18. doi: 10.1167/8.14.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hafed ZM, Goffart L, Krauzlis RJ. A neural mechanism for microsaccade generation in the primate superior colliculus. Science. 2009;323(5916):940–943. doi: 10.1126/science.1166112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Otero-Millan J, Macknik SL, Serra A, Leigh RJ, Martinez-Conde S. Triggering mechanisms in microsaccade and saccade generation: A novel proposal. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1233:107–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rolfs M, Kliegl R, Engbert R. Toward a model of microsaccade generation: The case of microsaccadic inhibition. J Vis. 2008;8(11):5.1–23. doi: 10.1167/8.11.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinman RM, Haddad GM, Skavenski AA, Wyman D. Miniature eye movement. Science. 1973;181(4102):810–819. doi: 10.1126/science.181.4102.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mergenthaler K, Engbert R. Microsaccades are different from saccades in scene perception. Exp Brain Res. 2010;203(4):753–757. doi: 10.1007/s00221-010-2272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen AL, et al. The disturbance of gaze in progressive supranuclear palsy: Implications for pathogenesis. Front Neurol. 2010;1:147. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2010.00147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Otero-Millan J, et al. Distinctive features of saccadic intrusions and microsaccades in progressive supranuclear palsy. J Neurosci. 2011;31(12):4379–4387. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2600-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058535. Otero-Millan J, Schneider R, Leigh RJ, Macknik SL, Martinez-Conde S (2013) Saccades during attempted fixation in parkinsonian disorders and recessive ataxia: From microsaccades to square-wave jerks. PLoS ONE 8(3):e58535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez-Conde S, Macknik SL, Troncoso XG, Hubel DH. Microsaccades: A neurophysiological analysis. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32(9):463–475. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rolfs M, Laubrock J, Kliegl R. Shortening and prolongation of saccade latencies following microsaccades. Exp Brain Res. 2006;169(3):369–376. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Wartburg R, et al. Size matters: Saccades during scene perception. Perception. 2007;36(3):355–365. doi: 10.1068/p5552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enoch JM. Effect of the size of a complex display upon visual search. J Opt Soc Am. 1959;49(3):280–286. doi: 10.1364/josa.49.000280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartigan JA. The dip test of unimodality. Ann Stat. 1985;13(1):70–84. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brockmann D, Geisel T. The ecology of gaze shifts. Neurocomputing. 2000;2(1):643–650. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tatler BW. The central fixation bias in scene viewing: Selecting an optimal viewing position independently of motor biases and image feature distributions. J Vis. 2007;7(14):4.1–17. doi: 10.1167/7.14.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ko HK, Poletti M, Rucci M. Microsaccades precisely relocate gaze in a high visual acuity task. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(12):1549–1553. doi: 10.1038/nn.2663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein RM. Inhibition of return. Trends Cogn Sci. 2000;4(4):138–147. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01452-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galfano G, Betta E, Turatto M. Inhibition of return in microsaccades. Exp Brain Res. 2004;159(3):400–404. doi: 10.1007/s00221-004-2111-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalesnykas RP, Hallett PE. Retinal eccentricity and the latency of eye saccades. Vision Res. 1994;34(4):517–531. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)90165-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thaler L, Schütz AC, Goodale MA, Gegenfurtner KR. What is the best fixation target? The effect of target shape on stability of fixational eye movements. Vision Res. 2013;76:31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCamy MB, Najafian Jazi A, Otero-Millan J, Macknik SL, Martinez-Conde S. The effects of fixation target size and luminance on microsaccades and square-wave jerks. PeerJ. 2013;1(1):e9. doi: 10.7717/peerj.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Gisbergen JAM, Robinson DA. Control of Gaze by Brain Stem Neurons. New York: Elsevier/North-Holland; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez-Conde S, Otero-Millan J, Macknik SL. The impact of microsaccades on vision: Towards a unified theory of saccadic function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(2):83–96. doi: 10.1038/nrn3405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brien DC, Corneil BD, Fecteau JH, Bell AH, Munoz DP. The behavioural and neurophysiological modulation of microsaccades in monkeys. J Eye Mov Res. 2009;3(2):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Horn MR, Cullen KE. Coding of microsaccades in three-dimensional space by premotor saccadic neurons. J Neurosci. 2012;32(6):1974–1980. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5054-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hafed ZM, Krauzlis RJ. Similarity of superior colliculus involvement in microsaccade and saccade generation. J Neurophysiol. 2012;107(7):1904–1916. doi: 10.1152/jn.01125.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leigh RJ, Zee DS. The Neurology of Eye Movements. New York: Oxford Univ Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martinez-Conde S, Macknik SL, Troncoso XG, Dyar TA. Microsaccades counteract visual fading during fixation. Neuron. 2006;49(2):297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Troncoso XG, Macknik SL, Martinez-Conde S. Microsaccades counteract perceptual filling-in. J Vis. 2008;8(14):15.1–9. doi: 10.1167/8.14.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCamy MB, et al. Microsaccadic efficacy and contribution to foveal and peripheral vision. J Neurosci. 2012;32(27):9194–9204. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0515-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Engbert R, Kliegl R. Microsaccades keep the eyes’ balance during fixation. Psychol Sci. 2004;15(6):431–436. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Donner K, Hemilä S. Modelling the effect of microsaccades on retinal responses to stationary contrast patterns. Vision Res. 2007;47(9):1166–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Engbert R, Kliegl R. Microsaccades uncover the orientation of covert attention. Vision Res. 2003;43(9):1035–1045. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(03)00084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olmos A, Kingdom FAA. A biologically inspired algorithm for the recovery of shading and reflectance images. Perception. 2004;33(12):1463–1473. doi: 10.1068/p5321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Optican LM. A field theory of saccade generation: temporal-to-spatial transform in the superior colliculus. Vision Res. 1995;35(23–24):3313–3320. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(95)00129-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]