G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are the largest and most diverse group of membrane receptors in eukaryotes and are targets of more than 25% of the medications currently on the market. Metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs), family C GPCRs, modulate synaptic transmission and neuronal excitability throughout the central nervous system and thus are promising targets for the treatment of various neurological and psychiatric disorders (1). Understanding the detailed activation mechanisms of mGluRs is therefore crucial to the development of new therapeutics. Although extensively studied over the last decade, the conformational changes involved in receptor activation are still a matter of debate (2). In PNAS, Doumazane et al. (3) describe how they have developed an innovative FRET-based approach to monitor these conformational changes upon ligand binding. Their assay not only helps to resolve controversy regarding the conformational changes involved in receptor activation but also facilitates our understanding of the mode of action of allosteric modulators. This approach therefore provides a powerful tool for drug screening.

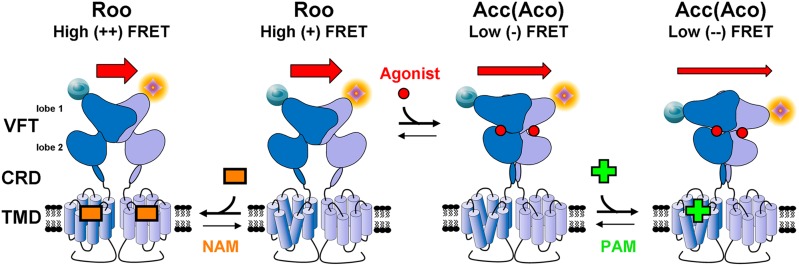

Family C GPCRs are obligate dimers; in the case of mGluRs, the two protomers are covalently connected via a disulfide bond (2, 4, 5). Each protomer contains a large extracellular domain (ECD) responsible for orthosteric ligand binding. The ECD is composed of a Venus flytrap (VFT) bilobate domain containing the ligand-binding site and a cysteine-rich domain that connects the VFT to the seven-helix transmembrane domain (TMD) (for review, see ref. 2) (Fig. 1). The binding of an agonist to the VFTs induces a series of conformational changes throughout the receptor, leading to the activation of intracellular effectors by the TMD and downstream signaling (2). How these domains work together to activate the coupled effectors remained poorly understood until 2000 and 2002, when the first crystal structures of the extracellular ligand-binding region of mGluR1 were solved (6, 7). The VFTs exist in two major states: an open state (o) and a closed state (c) (for review, see ref. 2). In the absence of agonist or in the presence of antagonist, both VFTs were thought to be open (oo), with the binding of one or two agonists inducing the closure of one (co) or two (cc) of the VFTs in the dimer, respectively. It has been proposed that the closure of at least one VFT induces a large change in the relative orientation of the two VFTs (2), which transitions the receptor dimer from a resting (R) to an active (A) orientation, thereby defining three major states, Roo, Aco, and Acc (2) (Fig. 1). In the putative R state, the distance between the two lobe 2s of the dimeric VFTs is greater than in the agonist-bound A state. In contrast, the N-terminal lobe 1s are farther apart in the active state (Fig. 1). However, publication of the structures of dimeric VFTs in the closed conformation in the presence of an antagonist and in the open state in the presence of an agonist (8, 9) contradicted this model.

Fig. 1.

Sensing conformational changes in mGlu receptors. Labeling of cell surface receptors at their N termini with fluorophores compatible with time-resolved FRET measurements allows detection of conformational changes of the ECDs associated with receptor activation. The closure of the VFTs after agonist binding causes the N termini to move away from each other, inducing a decrease of the FRET signal. Positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) stabilize the active closed conformation (Acc/Aco) whereas negative allosteric modulators (NAMs) stabilize the resting open state (Roo). CRD, cysteine-rich domain. Modified from ref. 2, Copyright 2011, with permission from Elsevier.

Doumazane et al. (3) used a combination of innovative technologies to specifically label the extracellular N termini of cell surface mGluR2 receptors with fluorophores compatible with time-resolved FRET (tr-FRET) measurements, which read out on the distance between the two fluorophores (10). According to the model described above, the N termini move away from each other in the active state (Fig. 1), suggesting that receptor activation would be associated with a decrease of the FRET signal. Consistent with this hypothesis, glutamate, as well as four other agonists, decreased the FRET efficiency, reflecting the proposed agonist-stabilized closure of the VFTs and associated reorientation of the dimeric VFTs. Using various biochemical and pharmacological tools, as well as mutagenesis analysis, the authors were able to correlate these conformational changes with receptor activation. Importantly, Doumazane et al. obtained similar results with both mGluR1 and mGluR3, clarifying what appear to be general activation mechanisms of mGluRs and highlighting the limits of crystallographic studies using isolated ECDs for the study of conformational changes associated with receptor activation (2, 8, 9).

The technology developed by Doumazane et al. (3) also allows for the identification of partial agonists. The application of two well-known mGluR agonists only partially decreased the intramolecular FRET efficiency, consistent with their pharmacological characterization as partial agonists. However, further investigation is needed to determine if the partial FRET decrease induced by partial agonists is the result of a partial closure of the VFTs or to a smaller population in the fully closed state because of a change in the dynamics. Indeed, the millisecond time scale of donor lifetime in tr-FRET may allow for integration of energy transfer from different conformational states (11).

This technology also reveals allosteric modulation between the ECDs and the TMDs. Although the orthosteric binding sites are located between the two lobes of each VFT, many allosteric modulators of class C GPCRs bind in the TMD (for review, see ref. 12). Both negative allosteric modulators, which act as noncompetitive inhibitors and often display inverse agonist activity, and positive allosteric modulators, which enhance the potency and efficacy of agonists, have been identified for mGluRs (12). Doumazane et al. (3) demonstrate that positive allosteric modulators stabilized the active closed conformation of the VFTs, and negative allosteric modulators inhibited the decrease in intramolecular FRET associated with agonist-induced receptor activation. Allosteric modulators offer numerous potential advantages for drug discovery; they often display higher subtype selectivity than orthosteric ligands. Moreover, because some allosteric modulators only exert their effects when the endogenous agonist is present, they can display fewer side effects, fine-tuning—temporally and spatially—the effect of endogenous ligands. The sensor developed by Doumazane et al. (3) is sensitive to the effects of allosteric modulators and thus can also be used to screen for such compounds.

Another exciting property of this FRET sensor is its ability to detect conformational changes within the ECDs induced by intracellular interacting proteins, such as G proteins. Consistent with the well-known ability of nucleotide-free G proteins to stabilize the high-agonist affinity state of GPCRs (13), Doumazane et al. (3) show that overexpressing a Go dominant-negative mutant with a low affinity for GDP enhanced the potency of agonists in the FRET assay. Future work including the use of other signaling molecules, such as Arrestins, may help to decipher mechanisms involved in functional selectivity. Functional selectivity, also called ligand bias, has been shown at many GPCRs (14). GPCRs can activate multiple signaling pathways, and drug action at

The FRET sensor developed by Doumazane et al. is a powerful tool providing key information on the structural dynamics of mGluRs.

some is responsible for therapeutic effects and others for side effects. Developing functionally selective ligands capable of activating only the signaling pathway of interest could lead to better therapeutics (14). A recent study reported functional selectivity at the mGlu1a receptor (15). Emery et al. (15) identified unbiased ligands, ligands biased toward G-protein activation, as well as ligands biased toward arrestin recruitment. Interestingly, ligand bias at mGlu1a appeared to involve different agonist interactions in the ligand-binding pocket, consistent with the stabilization of different conformations of the VFTs. The sensor developed by Doumazane et al. (3) could be used to investigate how the biased ligands identified at mGlu1a differentially affect the closure of the VFTs as well as their relative reorientation.

A limitation of the current sensor is that it is only capable of measuring one relative distance between two probes inserted at the N termini of the dimeric receptors and thus cannot differentiate distinct conformations in which the probes might still be similar differences apart. Ligand bias indeed suggests the existence of multiple distinct conformations, able to preferentially activate distinct effectors. Recent biophysical and biochemical studies are consistent with the existence of multiple conformational states for specific class A GPCRs (16, 17). The labeling of several residues within the TMD has allowed measurement of relative distance changes between the different helices of the TMD upon ligand application, which has begun to provide a more nuanced 3D mapping of conformational changes. Although the FRET sensor developed by Doumazane et al. (3) is a powerful tool providing key information on the structural dynamics of mGluRs, more information will be needed to decipher conformational heterogeneity associated with functional selectivity. Inserting FRET probes at other positions in the ECDs, or even TMDs, could be a next step in this direction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DA022413 and MH054137.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Niswender CM, Conn PJ. Metabotropic glutamate receptors: Physiology, pharmacology, and disease. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:295–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.011008.145533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rondard P, Goudet C, Kniazeff J, Pin JP, Prézeau L. The complexity of their activation mechanism opens new possibilities for the modulation of mGlu and GABAB class C G protein-coupled receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60(1):82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doumazane E, et al. Illuminating the activation mechanisms and allosteric properties of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:E1416–E1425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215615110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brock C, et al. Activation of a dimeric metabotropic glutamate receptor by intersubunit rearrangement. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(45):33000–33008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702542200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maurel D, et al. Cell-surface protein-protein interaction analysis with time-resolved FRET and snap-tag technologies: Application to GPCR oligomerization. Nat Methods. 2008;5(6):561–567. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kunishima N, et al. Structural basis of glutamate recognition by a dimeric metabotropic glutamate receptor. Nature. 2000;407(6807):971–977. doi: 10.1038/35039564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsuchiya D, Kunishima N, Kamiya N, Jingami H, Morikawa K. Structural views of the ligand-binding cores of a metabotropic glutamate receptor complexed with an antagonist and both glutamate and Gd3+ Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(5):2660–2665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052708599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muto T, Tsuchiya D, Morikawa K, Jingami H. Structures of the extracellular regions of the group II/III metabotropic glutamate receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(10):3759–3764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611577104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dobrovetsky E, et al., Structural Genomics Consortium (SGC), PDB Protein Data Bank entry 3LMK, 10.2210/pdb3lmk/pdb.

- 10.Selvin PR. Principles and biophysical applications of lanthanide-based probes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2002;31:275–302. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.101101.140927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selvin PR, Hearst JE. Luminescence energy transfer using a terbium chelate: Improvements on fluorescence energy transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91(21):10024–10028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wood MR, Hopkins CR, Brogan JT, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. “Molecular switches” on mGluR allosteric ligands that modulate modes of pharmacology. Biochemistry. 2011;50(13):2403–2410. doi: 10.1021/bi200129s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao XJ, et al. The effect of ligand efficacy on the formation and stability of a GPCR-G protein complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(23):9501–9506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811437106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mailman RB, Murthy V. Ligand functional selectivity advances our understanding of drug mechanisms and drug discovery. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(1):345–346. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emery AC, et al. Ligand bias at metabotropic glutamate 1a receptors: Molecular determinants that distinguish β-arrestin-mediated from G protein-mediated signaling. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;82(2):291–301. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.078444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nygaard R, et al. The dynamic process of β(2)-adrenergic receptor activation. Cell. 2013;152(3):532–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahmeh R, et al. Structural insights into biased G protein-coupled receptor signaling revealed by fluorescence spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(17):6733–6738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201093109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]