Abstract

Mitochondrial diseases are a genetically and clinically diverse group of disorders that arise as a result of dysfunction of the mitochondria. Mitochondrial disorders can be caused by alterations in nuclear DNA and/or mitochondrial DNA. Although some mitochondrial syndromes have been described clearly in the literature many others present as challenging clinical cases with multisystemic involvement at variable ages of onset. Given the clinical variability and genetic heterogeneity of these conditions, patients and their families often experience a lengthy and complicated diagnostic process. The diagnostic journey may be characterized by heightened levels of uncertainty due to the delayed diagnosis and the absence of a clear prognosis, among other factors. Uncertainty surrounding issues of family planning and genetic testing may also affect the patient. The role of the genetic counselor is particularly important to help explain these complexities and support the patient and family’s ability to achieve effective coping strategies in dealing with increased levels of uncertainty.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13311-012-0173-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Mitochondrial disease, Genetic, Counseling, Pediatric, Inheritance, Uncertainty

Introduction

Mitochondrial diseases are a genetically and clinically diverse group of disorders that arise as a result of dysfunction of the mitochondria, which are responsible for making most of a cell’s energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate. The biochemical intricacy of oxidative phosphorylation, respiratory chain function, and the contribution of both the nuclear and mitochondrial genomes lead to this complexity [1].

Some of the commonly observed symptoms associated with mitochondrial disease can be classified into discrete clinical syndromes; however, the presentation and severity of these conditions may vary widely. Patients can present at any age, with almost any affected body system, and symptom severity can also vary widely. These factors can hinder the recognition and diagnosis of mitochondrial disease and clinicians are often left with more questions than answers for families. Genetic counseling is challenging owing to uncertainties about prognosis and recurrence risk.

Mitochondrial disorders can be caused by alterations in nuclear DNA (nDNA) and/or mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). The mtDNA and nDNA have a symbiotic relationship that is essential for normal functioning of the electron transport chain and mitochondria. Historically, patients with clinically suspected mitochondrial disease would be confirmed through respiratory chain dysfunction and/or biochemical abnormalities, and yet many did not have a known molecular etiology. Genetic testing technology is advancing rapidly and our ability to determine a molecular etiology in mitochondrial disease has improved. In nDNA alterations, in particular, this has enabled clinicians to offer more targeted genetic counseling to families. In this new era of genomic medicine we have an increased ability to detect genetic alterations, yet predicting pathogenicity and prognosis often remains elusive for families. Uncertainties about associated medical issues, cognitive limitations, and life span often persist, even after a molecular diagnosis [2]. Uncertainty has emerged as a vital element in how families adapt and cope with a new diagnosis [3]. The uncertainty associated with mitochondrial disease makes genetic counseling especially challenging, yet important, in this population.

Family History Risk Assessment

Collection of detailed family history information is important across many disciplines of medicine, not just in a genetics clinic. Family history is a useful diagnostic and risk assessment tool. In mitochondrial disease, where symptoms can vary widely, even within families, a comprehensive pedigree can enable connection of seemingly unrelated symptoms. The identification of specific inheritance patterns can help guide diagnostic testing. In families where there is a clear indication of maternal transmission of disease, mtDNA analysis is more likely to yield an informative result than nDNA analysis. Conversely, when a clear Mendelian pattern of inheritance is identified, nDNA testing may be more informative. Inheritance pattern recognition is important for clinicians evaluating patients with known, or suspected, mitochondrial disease. The key inheritance patterns in mitochondrial disease are outlined in the following sections through case examples to allow for clinical application of these concepts.

Case Example 1

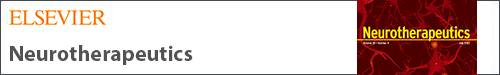

A 4-year-old male presents to a neuro-ophthalmology clinic with new onset decreased visual acuity. He has a history of myopathy and sensorineural hearing loss. Dilated eye examination reveals bilateral optic nerve pallor and the visual evoked potentials are delayed, indicating a conduction defect in the optic nerve. Family history is reviewed and reveals other family members with decreased visual acuity (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Case example 1 pedigree. The patient’s father has a history of decreased visual acuity and an ataxic gait, and he is an only child. The paternal grandmother is deceased, but was reported to have had decreased visual acuity. The remainder of the family history is unremarkable

Autosomal Dominant Inheritance

This family history is typical of an autosomal dominant (AD) inheritance pattern. AD conditions are those that only require 1 mutant gene (allele) to manifest disease. One will often note equally affected males and females, multiple affected generations, and male-to-male transmission. For an individual affected by an AD condition, each offspring has a 50 % recurrence risk. Decreased visual acuity, sensorineural deafness, myopathy, and ataxia all seen in one family could be due to a number of different mitochondrial and neurogenetic conditions. The identification of the inheritance pattern in this example can help narrow molecular testing options.

Optic atrophy, type 1 (OPA1) is an autosomal dominant condition caused by alterations in the OPA1 gene. As with many mitochondrial conditions, there is much inter- and intrafamilial variability in symptoms. Historically, OPA1 was believed to only cause optic atrophy; however, recent analysis suggests that it is often associated with subclinical multisystem neurologic disease [4]. For the parents of this patient, there is a 50 % recurrence risk for OPA1. If a disease-causing mutation is identified in OPA1, targeted testing and reproductive testing options are available to any family members at risk. Counseling difficulties emerge in the ability to predict the likelihood of future offspring only developing ‘pure’ OPA1 or the risk for the development of other neurological sequelae.

Case Example 2

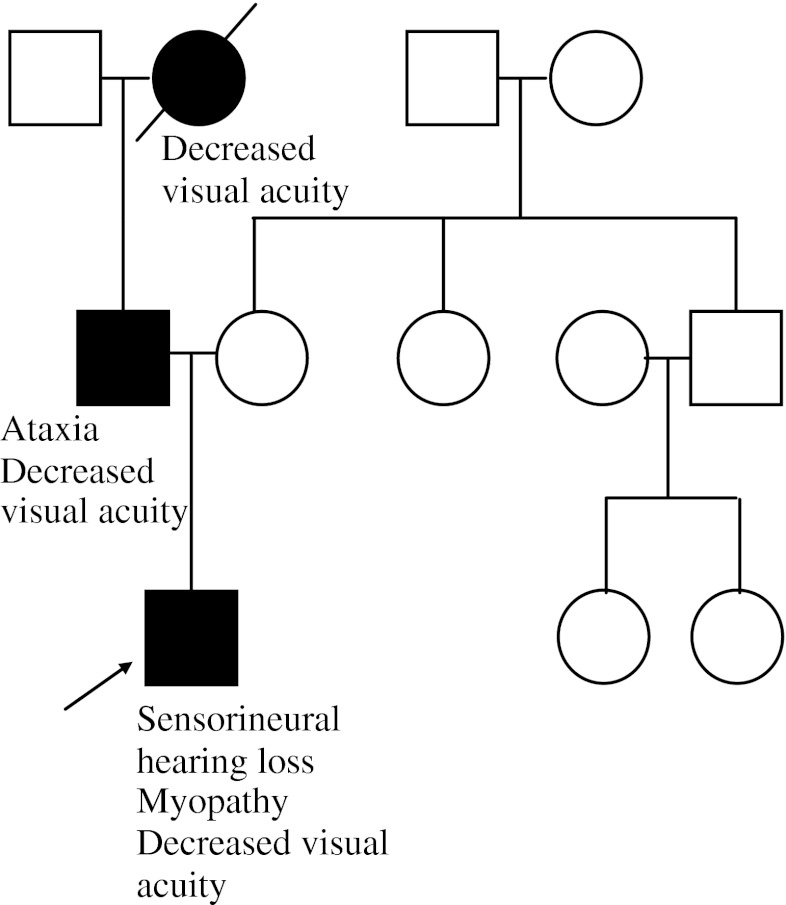

A 3-year-old female is referred to a neurology clinic for concern of psychomotor regression. She was previously walking, and is now unable to walk independently. Additionally, she has developed a movement disorder. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain reveals bilateral basal ganglia and brain stem lesions. The family reveals that they previously had a son, who had died; he was diagnosed with Leigh’s disease (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Case example 2 pedigree. The patient’s parents are first cousins. The patient had a 4-year-old brother, who is now deceased and who had been diagnosed with Leigh’s disease. The remainder of the family history is unremarkable

Autosomal Recessive Inheritance

This family history is consistent with an autosomal recessive (AR) inheritance pattern. AR conditions are those conditions that require 2 mutated alleles to manifest disease. Most of the time, carriers (those with only 1 mutated allele) do not manifest disease, or may only have mild symptoms. Family history will often be unremarkable, unless there is an affected sibling or consanguinity present, and there is an equal risk for both males and females to be affected. In this case example, the affected sibling and consanguineous union make an AR etiology very likely. Two carriers of an AR condition have a 25 % chance of having an affected offspring, a 50 % chance of having a carrier offspring, and a 25 % chance of having an unaffected, noncarrier offspring with each pregnancy. Many of the childhood onset mitochondrial diseases are caused by mutations in AR nuclear genes, such as SURF1. Leigh’s disease is an early-onset progressive neurodegenerative disorder with characteristic brain MRI findings, including focal, bilateral symmetric lesions, particularly in the basal ganglia, thalamus, and brainstem [5]. Leigh’s disease can be caused by a number of different nDNA and mtDNA mutations. Identifying the AR inheritance in this family history can help to direct the nDNA testing. SURF1 mutations have been identified in a number of individuals with Leigh’s or Leigh’s-like disease, and/or complex IV deficiency [6]. While AR conditions are evident with the presence of consanguinity and/or affected sibling(s), it remains important to consider this inheritance pattern in many childhood-onset mitochondrial diseases in the absence of a suspicious family history.

Case Example 3

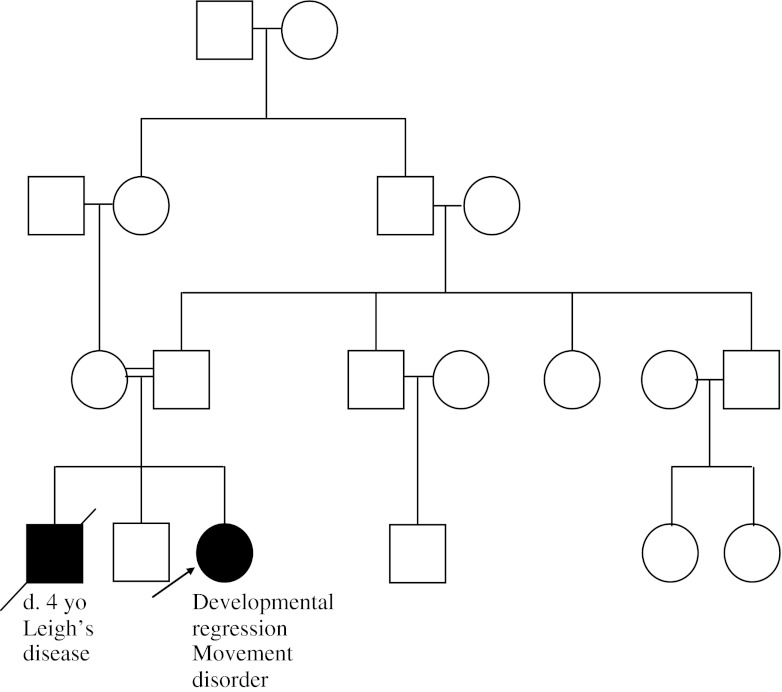

A 7-year-old male has been followed in a neurology clinic for several years owing to a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by seizures, ataxia, and psychomotor regression. He has remained undiagnosed despite extensive testing. At a recent visit, the family notes that his 5-year-old sister seems to have low muscle tone and exercise intolerance, but normal cognition and development (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Case example 3 pedigree. The patient’s sister has hypotonia and lactic acidosis. The maternal uncle died at 3 years of age from complications of “cerebral palsy”. The suspected obligate carrier females are noted with a dot in the center. The remainder of the family history is unremarkable

X-linked Inheritance

The family history in this case example is suspicious for an X-linked inheritance pattern. X-linked inheritance is caused by a mutated X chromosome. Females only require 1 working copy of the X chromosome in each cell in their body and randomly inactivate the other copy of the X chromosome. This is a protective mechanism in females; one of the key characteristics of X-linked inheritance is a family history with only males affected (or males affected more severely than females), and with no male-to-male transmission. The concept of dominant and recessive X-linked inheritance can be blurry owing to X-inactivation. Many diseases that were previously described as X-linked recessive disorders can have females that present with milder symptoms. Additionally, family members may have inaccurate diagnoses that are misleading. In this example, it is possible that the maternal uncle with “cerebral palsy” actually has the same diagnosis as the example patient. The milder presentation of the male patient’s sister with hypotonia, exercise intolerance, and lactic acidosis can be seen in X-linked conditions. There are not many known X-linked mitochondrial diseases, but the NDUFA1 gene is on the X chromosome and is known to be associated with complex I deficiency and a progressive neurodegenerative presentation [7]. Female carriers were previously thought to be asymptomatic, but there are recent reports of mild symptoms, such as hypotonia and lactic acidosis [8]. This may be due to skewed X-inactivation in some carrier females. In this family the less severely affected female and two possible associated neurodegenerative conditions in maternally-related males helped to identify the X-linked inheritance pattern. There is a 50 % recurrence risk in this family, but it would be expected that males would have a more severe presentation and female carriers may have no symptoms or only mild symptoms. In X-linked conditions where female carriers are asymptomatic, the recurrence risk in any pregnancy is 25 % (50 % chance that the mother passes on the mutation and 50 % chance that the offspring is male).

Case Example 4

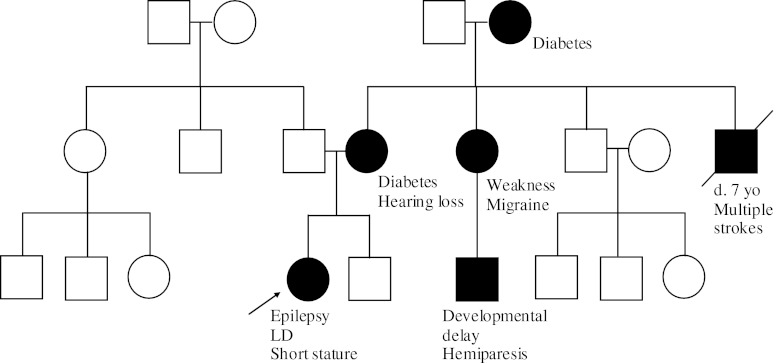

A 9-year-old female presents to the emergency room with new-onset seizures. She has a history of learning disability and short stature. She is afebrile and there is no suspected trauma. While the patient is sent for a brain MRI, the family history is collected and reviewed (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Case example 4 pedigree. The patient’s mother has a history of hearing loss and diabetes. A maternal uncle died suddenly of a stroke and complications that followed in childhood. The maternal grandmother also has difficult-to-control diabetes. A maternal aunt has muscle weakness and migraines, and her son has developmental delay and hemiparesis. The paternal medical history is unremarkable

Maternal Inheritance

This family history is consistent with a maternal inheritance pattern, which is typically seen in mtDNA mutations. Mitochondrial diseases, caused by alterations in the mtDNA, are always maternally inherited as ova contain mitochondria, whereas any mitochondria contributed by the sperm are destroyed shortly after fertilization. Mitochondrial encephalomyopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes most commonly presents with stroke-like episodes, encephalopathy with seizures or dementia, and myopathy during childhood [9]. However, there can be much intrafamilial phenotypic variability. Some individuals may only have hearing loss or diabetes mellitus. Identifying the pattern of symptoms in this example family is essential for appropriate diagnostic testing and counseling for other at-risk individuals. In individuals with a mild presentation, the common point mutation (m.3243A>G) may not be detectable in blood leukocytes. Urine sediment is an often an informative tissue in this population and is much less invasive than a muscle biopsy.

Additional Contributing Factors

Mitochondrial disorders that are due to nDNA alterations follow Mendelian inheritance patterns (AD, AR, XL), as outlined in case examples 1, 2, and 3. Recurrence risk counseling in these families is typically straightforward; however, phenotypic variability can lead to some ambiguity in prognosis. As in case example 4, the difficulty in accurately predicting the clinical consequences and inheritance of mtDNA abnormalities is much more complex owing to several complicating factors, including heteroplasmy, and the bottleneck and threshold effects. Heteroplasmy describes a mixture of mitochondria within 1 cell, with some containing mutant DNA and some containing normal DNA. As technology improves, there is increased ability to detect low-level heteroplasmy through blood, urine sediment, and tissue analysis. As with many genetic conditions, even after determining the underlying genotype, predicting clinical consequences is more challenging. While a mother with mtDNA alterations transmits mutant mtDNA to all of her offspring, the degree of heteroplasmy can vary from egg to egg because of the random bottleneck effect determined at an early stage during oogenesis. The “bottleneck effect” describes the restriction in the number of mitochondrial genomes during early oogenesis, thus creating a random sampling effect. This explains why a mother with a very mild presentation (possibly even asymptomatic) could have one offspring with very severe disease and another offspring with no disease symptoms at all.

The threshold effect describes the minimum amount of energy required by a cell, tissue, or organ to function properly. This threshold can vary over the course of development, during times of physiological stress (illness), and from tissue to tissue. Some tissues require more energy (i.e., brain and muscle) than others (i.e., skin) and therefore have a lower energy threshold and tolerance for mutant mitochondria. In most genetic conditions the identification of the underlying molecular defect enables one to offer targeted reproductive testing options. This becomes much more complex with mtDNA alterations. While some empiric studies of particular mtDNA mutations exist to give an approximate indication of recurrence [10], these are not targeted to a particular individual and may be misleading. In prenatal testing, the mtDNA sampled through amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling may not accurately reflect mutant load in most tissues at birth [11].

While most mtDNA point mutations are maternally inherited, most mtDNA deletions are de novo, occurring either in the mother’s oocyte or during embryogenesis. The 3 overlapping phenotypes associated with mtDNA deletions are Kearns–Sayre syndrome, Pearson syndrome, and progressive external ophthalmoplegia. Some mtDNA deletions will not be detectable in blood, thereby necessitating further tissue analysis through muscle biopsy. Clinical characterization and diagnosis is essential for determining whether a muscle biopsy is needed. Determining if a mtDNA deletion is maternally inherited or de novo is essential for proper genetic counseling and medical management of family members.

A genetic counselor is poised to explain the aforementioned complexities of mitochondrial disease prognosis, inheritance, and reproductive testing options in a tailored, family-centered approach. There are many psychosocial issues that may arise, including guilt, blame, and maladaptive coping in the face of uncertainty. While many of these issues are not exclusive to mitochondrial disorders, the genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity make the process of genetic counseling quite challenging in this population. The following sections summarize the main challenges encountered by providers working with patients (and families) with suspected (or confirmed) mitochondrial disease. Although these factors are described from the perspective of the genetic counselor, they are not unique to this subgroup of clinicians.

Heterogeneity of Clinical Diagnosis

The clinical heterogeneity of mitochondrial disease presents a major challenge for providers at the diagnostic stage and complicates the management of the condition. Although several mitochondrial syndromes present with well-recognized features, most patients with abnormalities of the mitochondrial respiratory chain initially develop nonspecific multisystemic symptoms that may delay diagnosis and proper management. Whereas the former group includes patients with mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes, Leber hereditary optic neuropathy, or Leigh syndrome (subacute necrotizing encephalopathy), the latter may include patients with exercise intolerance, developmental delay, or regression, among other nonspecific clinical features. Given the variable nature of the clinical findings, these patients may come to the attention of physicians specializing in different areas of medicine [12, 13]. Although clinical variability is not a pathognomonic feature of mitochondrial disease, it is certainly a hallmark of this group of conditions. Although several attempts have been made to improve the accurate diagnosis of these ambiguous presentations of mitochondrial disease [14], much work is still needed.

Given these circumstances, the diagnostic process is often viewed as a complex journey from the patients’ perspective that is often characterized by dynamic emotions, and affected by the patients’ support systems and providers. In fact, a study conducted in the UK in which 14 parents were asked to discuss their experience searching for a diagnosis for their child showed that their perception of the process could be divided into two distinct categories: the emotional experience and the sociological experience. [15] Whereas the former included the active effort of coming to terms with the health status of their child and making meaning of the situation, among other factors, the latter comprised their interactions with members of the healthcare team and their access to support systems. Interestingly, the feeling of frustration was noted in all aspects of their journeys as they encountered obstacles in their search for a diagnosis [15]. These findings may be particularly relevant to families with suspected mitochondrial disease who may undergo extensive, and often invasive, evaluation by several specialties of medicine prior to obtaining a formal diagnosis.

In addition to the emotional and social stressors imposed on the patient throughout the diagnostic process, receiving a diagnosis of mitochondrial disease continues to leave many questions unanswered for the patient and the providers. Although much effort has been placed on maximizing diagnostic capabilities, less work has focused on understanding the psychosocial outcomes experienced by patients as they receive and cope with this new diagnosis. A qualitative study exploring the parental perceptions of the importance for achieving diagnostic certainty outlines that most parents were motivated to find a diagnosis that would lead them to more precise prognosis and intervention options [16]. However, given the variable nature of mitochondrial disease and the lack of formal treatment guidelines, a clinical diagnosis may not fulfill these expectations.

This heightened level of uncertainty, even in the presence of a confirmed clinical diagnosis, is not unique to mitochondrial disease, and is a hallmark of many variable genetic conditions. Studies exploring this phenomenon in parents of children with chromosome abnormalities, show that, owing to the lack of prognostic information and the variability in the clinical spectrum, the sense of perceived uncertainty is maintained even after a clinical diagnosis has been made [2, 17].

Moreover, several studies have focused on the construct of uncertainty as a precursor of other undesirable psychosocial outcomes, such as anxiety, depression, and helplessness [18, 19]. However, it is important to note that positive outcomes of living with uncertainty have also been reported. In such cases, parents reported that being uncertain about the course of the disease in their children allowed them to be more hopeful for a positive outcome [20, 21].

Although our current knowledge of how this construct specifically affects psychosocial outcomes in patients with mitochondrial disease remains unclear, findings in other populations may be particularly informative and may help providers tailor their interventions within the context of mitochondrial disease. Given their expertise in psychosocial interventions, genetic counselors may be instrumental in tailoring the counseling approach based on the patient’s level of perceived uncertainty, thus facilitating effective coping strategies [3].

Implications of Genetic Testing

Owing to the genetic complexities of mitochondrial disease, confirming a diagnosis by molecular testing may be extremely helpful from a management and preventive standpoint. As Graham [1] outlines, confirming a diagnosis of mitochondrial disease may ensure proper management and surveillance, identify relatives at risk, and allow more accurate recurrence risk information.

As shown in the case examples, identifying a causative mutation may provide additional information regarding the pattern of inheritance for the clinical phenotype. This, in turn, allows the healthcare team to provide a more accurate assessment of recurrence risk and it contributes to identifying at-risk family members. Although from a provider perspective achieving a molecular diagnosis is key, little is known about how this added knowledge impacts patients and their families.

In situations similar to case example 4, for example, obtaining a more clear understanding of the inheritance mechanism may not necessarily reduce the level of uncertainty in patients and their families. In fact, findings extrapolated from research conducted in other populations affected by genetic disorders show that the risk and benefit ratio of genetic testing from the perspective of the patient remains a poorly explored area. In a systematic review of the literature addressing the benefits and harms of undergoing genetic testing, Rew et al. [22] identified three major benefits posed by undergoing genetic testing. These include a more accurate calculation of reproductive risk, earlier access to treatments, and increased quality of life for the patient. However, they also mention that receiving results of genetic testing may cause patients to develop adverse psychosocial reactions. The study outlines the importance of an informed consent process preceding the genetic test, but fails to provide guidance for a systemic approach to deal with the possible adverse outcomes of the results. The role of genetic counselors and other professionals in the team may be extremely important in anticipating these negative outcomes and facilitating an open dialogue to identify the personal motivations driving the pursuit of genetic testing. Moreover, genetic counselors may be well suited to engage in a clear discussion with the patient, addressing the realistic expectations of this diagnostic tool.

Reproductive Planning

In addition to providing support throughout the diagnostic process and the management stages of the disease, genetic counselors play a crucial role in facilitating discussion around reproductive planning and recurrence risk of disease. As is exemplified by the cases described above, this discussion may be particularly challenging for families with a suspected mitochondrial disease. Without a confirmed molecular diagnosis, the risk of recurrence varies greatly depending on the inheritance pattern of the underlying molecular abnormality.

However, when a pathogenic mutation has been identified in a parent seeking preconception or prenatal genetic counseling, the main question becomes whether the mutation is located in the nuclear or mitochondrial genome. For mutations located in the nuclear genome, techniques such as chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis may be available at different stages of the pregnancy to evaluate whether the fetus has inherited the abnormality. Pre-implantation genetic testing for these mutations is also available.

However, when a pathogenic mutation is identified in the mtDNA of an affected mother, the possibilities for pursuing preconception and prenatal diagnosis in the offspring are greatly hampered. The nuances of mtDNA replication and inheritance contribute an additional layer of complexity to this discussion. The use of technology such as pre-implantation genetic diagnosis in this patient population still remains highly controversial and raises many ethical concerns [23]. One of the main concerns with the use of this technology in this population derives from the fact that mutant load cannot be predicted in all the tissues of the resulting embryo. In other words, the provider cannot guarantee that the resulting embryo will be completely asymptomatic, even after undergoing this procedure. Conversely, the reciprocal argument is also a considerable ethical dilemma. Given that not much is known about how mutant levels correlate with disease severity for specific mutations and within tissues, it becomes ethically challenging to determine which embryos will be implanted based on this assessment.

Another technique under research will involve the use of donor cytoplasm in cases where the biological mother is a known carrier or at risk for carrying a mtDNA mutation. This procedure would potentially eliminate the chances of passing on a mtDNA mutation from an affected mother to her offspring. The procedure involves the transfer of the maternal nDNA into a donor egg from which the nuclear DNA has been removed. The newly combined egg can then be fertilized and implanted into the womb. Although this technique is very promising, not much is known about the parental attitudes towards undergoing this procedure. However, in order to shed some light on this issue, the North American Mitochondrial Disease Consortium has directed specific efforts to explore general attitudes to the use of oocyte nuclear transfer specifically in the context of mitochondrial disease.

Conclusion

The clinical and genetic complexities of mitochondrial disease present major challenges for providers, patients, and their families. As many aspects of this heterogeneous group of diseases remain unknown, the uncertainty surrounding the diagnostic paradigm and the ongoing counseling for affected patients remains a challenge for providers. The findings reviewed by this article outline the importance of providing a holistic approach to the care of patients with suspected or confirmed mitochondrial disease.

With the rapid advancement of molecular technologies, such as whole exome sequencing, the prospect of identifying new genes that may contribute to mitochondrial function is very promising. Nevertheless, more immediate work is needed to achieve a better understanding of how patients and families deal with the uncertainty brought by this diagnosis and how well providers are able facilitate coping strategies during the difficult diagnostic journey. Moreover, additional work needs to be conducted in order to better understand how this information is communicated to and understood by the families, and how it may affect their lives, health behaviors, and reproductive planning.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(PDF 367 kb)

Acknowledgments

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

Contributor Information

Jodie M. Vento, Email: jodie.vento@chp.edu

Belen Pappa, Email: mpappa@childrensnational.org.

References

- 1.Graham BH. Diagnostic challenges of mitochondrial disorders: complexities of two genomes. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;837:35–46. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-504-6_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart JL, Mishel MH. Uncertainty in childhood illness: A synthesis of the parent and child literature. Sch Inq Nurs Pract. 2000;14:299–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipinski S, Lipinski MJ, Biesecker LG, Biesecker BB. Uncertainty and perceived personal control among parents of children with rare chromosome conditions: The role of genetic counseling. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2006;142C:232–240. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker MR, Fisher KM, Whittaker RG, Griffiths PG, Yu-Wai-Man P, Chinnery PF. Subclinical multisystem neurologic disease in “pure” OPA1 autosomal dominant optic atrophy. Neurology. 2011;77:1309–1312. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318230a15a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finsterer J. Leigh and Leigh-like syndrome in children and adults. Ped Neurology. 2008;39:223–235. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee IC, El-Hattab AW, Wang J, et al. SURF1-associated leigh syndrome: A case series and novel mutations. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:1192–1200. doi: 10.1002/humu.22095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potluri P, Davila A, Ruiz-Pesini E, Mishmar D, O'Hearn S, Hancock S, et al. A novel NDUFA1 mutation leads to a progressive mitochondrial complex I-specific neurodegenerative disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2009;96:189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayr JA, Bodamer O, Haack TB, Zimmermann FA, Madignier F, Prokisch H, et al. Heterozygous mutation in the X chromosomal NDUFA1 gene in a girl with complex I deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. 2011;103:358–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sproule DM, Kaufmann P. Mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes: basic concepts, clinical phenotype, and therapeutic management of MELAS syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1142:133–158. doi: 10.1196/annals.1444.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chinnery PF, Howell N, Lightowlers RN, Turnbull DM. MELAS and MERRF. The relationship between maternal mutation load and the frequency of clinically affected offspring. Brain. 1998;121:1889–1894. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.10.1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thorburn DR, Hans-Henrik DM. Mitochondrial disorders: Genetics, counseling, prenatal diagnosis and reproductive options. Am J Med Genet. 2001;106:102–114. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haas RH, Parikh S, Falk MJ, et al. Mitochondrial disease: a practical approach for primary care physicians. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1326–1333. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haas RH, Parikh S, Falk MJ, Saneto RP, Wolf NI, Darin N, et al. The in-depth evaluation of suspected mitochondrial disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;94:16–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernier FP, Boneh A, Dennet X, Chow CW, Cleary MA, Thorburn DR. Diagnostic criteria for respiratory chain disorders in adults and children. Neurology. 2002;59:1406–1411. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000033795.17156.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis C, Skirton H, Jones R. Living without a diagnosis: the parental experience. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2010;14:807–815. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2010.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graungaard AH, Skov L. Why do we need a diagnosis? A qualitative study of parents’ experiences, coping and needs, when the newborn child is severely disabled. Child Care Health Dev. 2006;33:296–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenthal ET, Biesecker LG, Biesecker BB. Parental attitudes toward a diagnosis in children with unidentified multiple congenital anomaly syndromes. Am J Med Genet. 2001;103:106–114. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jessup DJ, Stein RK. Uncertainty and its relationship to the psychological and social correlates of chronic illness in children. Soc Sci Med. 1985;12:993–999. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(85)90255-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grootenhius MA, Last BF. Predictors of parental emotional adjustment to childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 1997;6:115–128. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199706)6:2<115::AID-PON252>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clarke-Steffen L. A model of the family transition to living with childhood cancer. Cancer Pract. 1993;1:285–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen MH. The unknown and the unknowable- Managing sustained uncertainty. West J Nurs Res. 1993;15:77–96. doi: 10.1177/019394599301500106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rew L, Kaur M, McMillan A, Mackert M, Bonevac D. Systematic review of psychological benefits and harms of genetic testing. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2010;31:631–645. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2010.510618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bredenoord AL, Dondorp W, Pennings G, De Die-Smulders CE, De Wert G. PGD to reduce reproductive risk: the case of mitochondrial DNA disorders. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:2392–2401. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 367 kb)