Abstract

Objectives

We evaluated demographic, clinical and angiographic factors influencing the selection of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery versus percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in diabetic patients with multivessel coronary artery disease (CAD) in the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes (BARI 2D) trial.

Background

Factors guiding selection of mode of revascularization for patients with DM and multivessel CAD are not clearly defined.

Methods

In BARI 2D, the selected revascularization strategy, CABG or PCI, was based on physician discretion, declared independent of randomization to either immediate or deferred revascularization if clinically warranted. We analyzed factors favoring selection of CABG versus PCI in 1593 diabetic patients with multivessel CAD enrolled between 2001 and 2005.

Results

Selection of CABG over PCI was declared in 44% of patients and was driven by angiographic factors including: triple vessel disease (OR=4.43), left anterior descending (LAD) stenosis ≥70% (OR=2.86), proximal LAD stenosis ≥50% (OR=1.78), total occlusion (OR=2.35), and multiple class C lesions (OR=2.06), (all p< 0.005). Non-angiographic predictors of CABG included: age ≥ 65 years (OR=1.43, p=0.011), and non-US region (OR=2.89, p=0.017). Absence of prior PCI (OR=0.45, p<0.001), and the availability of drug-eluting stents (DES) conferred a lower probability of choosing CABG (OR=0.60, p=0.003).

Conclusions

The majority of diabetic patients with multivessel disease were selected for PCI rather than CABG. Preference for CABG over PCI was largely based on angiographic features related to the extent, location, and nature of CAD, as well as geographic, demographic and clinical factors.

Keywords: Revascularization selection, Diabetes, Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Coronary Artery Bypass Graft

INTRODUCTION

Patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) who comprise approximately 25% of the 1.5 million undergoing coronary revascularizations annually in the United States (US), experience worse outcomes after both coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) than those without DM. (1-4) Determination of the appropriate revascularization strategy for an individual patient is a complex issue that is of great importance, considering the growing number of patients with DM and coronary artery disease (CAD). In the original BARI trial, patients with medically treated DM and multivessel disease randomized to CABG versus PCI, limited to balloon angioplasty, had a significantly lower long-term mortality which prompted the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) to issue a Clinical Alert recommending CABG over angioplasty in this high-risk subset. (5,6) However, findings from the BARI Registry, in which selection of revascularization strategy was at the discretion of the treating physician, showed nearly identical 7-year survival with PCI or CABG in patients with diabetes, even when the data were adjusted for covariates. (7)

In the years since the BARI results were first reported, advances in PCI technology and adjunctive therapies have significantly improved clinical outcomes. In particular, the use of stents, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors and the direct thrombin inhibitor, bivalirudin have substantially lowered restenosis and acute ischemic and/or bleeding complication rates. (1,8-13) Furthermore, a growing appreciation for the critical role of intensive medical management and attention to cardiovascular risk factors has led to the widespread use of statins, beta-blockers, and ACE inhibitors. (14-16) These improvements in therapy have not changed ACC/AHA practice guidelines which recommend that, in general, patients with less extensive CAD be treated with PCI, while those with more extensive and severe disease be referred for CABG. (17,18) In addition, regional differences in the treatment of ischemic heart disease have been previously described. (19,20) Therefore, we evaluated demographic, clinical, geographic, and angiographic factors that influenced the selection of CABG versus PCI in patients with DM and multivessel CAD with stable symptoms enrolled in the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes (BARI 2D) trial.

METHODS

Study Design

BARI 2D is a randomized 2 × 2 factorial design trial designed to compare treatment strategies in patients with DM and CAD with stable symptoms: (i) immediate coronary revascularization plus intensive medical therapy versus intensive medical therapy alone with deferred revascularization, as needed, for treatment of CAD; and (ii) an insulin-providing strategy versus insulin-sensitizing strategy for treatment of DM. Following angiographic evaluation, and prior to randomization to immediate versus deferred revascularization, the mode of revascularization with either CABG or PCI was selected and declared by the clinical site study physicians. Patient preference was not recorded. A detailed description of the protocol has been published. (21) In brief, eligibility criteria required angiographically documented CAD involving at least one coronary artery (≥50% stenosis) suitable for treatment with either medical therapy alone or elective revascularization with CABG or PCI, and documented myocardial ischemia or at least one >70% stenosis with stable angina. Exclusion criteria included left main stenosis >=50%, any prior CABG or PCI in the past 12 months. A total of 2,368 participants enrolled from 49 clinical sites in the US, Brazil, Canada, Mexico, the Czech Republic, and Austria between January 1, 2001 and March 31, 2005 have been described. (22)

In the present analysis, we excluded patients with single vessel disease (n=611), those who had previously undergone CABG (n=152), and those with <80% complete baseline data or without clinical site evaluation of the baseline angiogram (n=35). Thus, the study population included 1593 patients with multivessel CAD from US (n=910) and non-US (n=683) sites.

Angiographic characteristics were assessed at the clinical sites and by a core laboratory (Stanford University). For this analysis, site determined angiographic variables are reported since they were utilized to determine the mode of revascularization. However, myocardial jeopardy index (MJI) which reflects the percentage of jeopardized myocardium was determined by the core lab. (23) Because MJI does not account for territories previously revascularized by either CABG or PCI, patients with prior PCI (n=285) were excluded from the presentation of MJI data.

Statistical Methods

Demographic, clinical, and angiographic characteristics related to the choice of CABG versus PCI were compared, using the chi-square test for categorical variables and the Cochran-Armitage trend test for ordinal variables, for the overall cohort and stratified by region (US and non-US). We examined the choice of revascularization procedure by MJI, and compared the US versus the non-US clinical centers.

Multivariable analysis of the “CABG selection” outcome was performed using a non-linear mixed model that included a random-effect intercept term for each clinical site. (24) These models incorporate the multilevel nature of treatment selection, based both on physician judgment and patient-level characteristics, and account for the correlation between observations within a site. The odds ratio for a patient-level factor (e.g. age) in a mixed model is interpreted as the estimated effect of the factor on the decision to choose CABG within an individual site, while the odds ratio for a site-level factor such as geographic region is interpreted as the estimated odds of choosing CABG among sites in one region versus another region adjusting for population differences between sites. Variable selection was accomplished using standard logistic regression. (25) Forward stepwise variable-selection methods were used to construct separate multivariable models for: (1) demographic and clinical characteristics; (2) cardiovascular medications; (3) site angiographic measurements; and (4) core lab angiographic measurements. In addition to the variables listed in Tables 1-3, candidate variables included: angina status, history of hypercholesterolemia, renal dysfunction, COPD, pulmonary edema, history of malignancy, smoking status, BMI, HbA1c, presence of Q-waves, ST depression, ST elevation, inverted T-waves, or any major ECG abnormality, LVEF<50%, serum creatinine, as well as RCA and circumflex variables similar to the LAD variables presented in Table 3. Factors identified from these models were combined, and geographic region (non-US versus US) and time of randomization (before versus after April 25, 2003, when DES became available at US and non-US sites) were added to the model. Covariates with P>0.05 were subsequently removed using backward selection. Statistical interactions between geographic region and main effects variables were tested, and interaction terms with P<0.01 were retained. Each of the interaction terms involving geographic region and the other explanatory variables had a p-value > 0.01 when added to the multivariable model; as a result, the final model does not include any interaction terms. Finally, a mixed model with random intercepts was created using the selected variables. The model intra-class correlation (ICC), representing the proportion of the total unexplained variability in treatment selection accounted for by clinical site, is reported. (25) Estimates for odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals (CI), and p-values are presented, and p<0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v9.1 (Cary, NC).

Table 1.

Intended revascularization strategy by geographic region and time among patients with diabetes and multivessel coronary artery disease in the BARI 2D trial

| No. of Clinical Sites |

No. of Patients (n) |

Intended Procedure |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CABG | PCI | ||||

| Total | 49 | 1593 | 44% | 56% | |

|

| |||||

| By Region: | |||||

| US | 40 | 910 | 31% | 69% | <0.001† |

| Non-US | 9 | 683 | 61% | 39% | |

|

|

|||||

| Brazil (Sao Paulo) | 1 | 293 | 73% | 27% | <0.001‡ |

| Canada | 5 | 271 | 47% | 53% | |

| Mexico (Mexico City) | 1 | 62 | 76% | 24% | |

| Europe* | 2 | 57 | 56% | 44% | |

|

| |||||

| By date of randomization**: | |||||

| US/Canada on or before April 25, 2003 | 39 | 656 | 39% | 61% | 0.0025 |

| US/Canada after April 25, 2003 | 39 | 473 | 30% | 70% | |

Row percentages are presented.

Czech Republic and Austria

Comparison of US vs. non-US regions using chi-square test

Comparison across the 5 regions using chi-square test

Includes only sites that randomized patients before April 25, 2003

Drug eluting stent (DES) became available on April 25, 2003 in the US.

Table 3.

Angiographic characteristics associated with the selection of CABG and PCI

|

All Patients (N=1592) |

US (n=910) |

Non-US (n=682) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Pts (n) |

Intended CABG |

Intended PCI |

P * | n | Intended CABG |

Intended PCI |

P * | n | Intended CABG |

Intended PCI |

P * | ||

|

CLINICAL SITE

MEASUREMENTS | |||||||||||||

| Vessel disease | Double | 746 | 25% | 75% | <.001 | 453 | 16% | 84% | <.001 | 293 | 40% | 60% | <.001 |

| Triple | 847 | 61% | 39% | 457 | 46% | 54% | 390 | 77% | 23% | ||||

| No. vessels ≥ 70% † | 0 | 44 | 11% | 89% | <.001 | 32 | 0% | 100% | <.001 | 12 | 42% | 58% | <.001 |

| 1 | 366 | 22% | 78% | 242 | 14% | 86% | 124 | 40% | 60% | ||||

| 2 | 713 | 39% | 61% | 408 | 28% | 72% | 305 | 53% | 47% | ||||

| 3 | 470 | 72% | 28% | 228 | 59% | 41% | 242 | 85% | 15% | ||||

| Proximal LAD ≥ 50% | No | 202 | 17% | 83% | <.001 | 130 | 11% | 89% | <.001 | 72 | 29% | 71% | <.001 |

| Yes | 1391 | 48% | 52% | 780 | 34% | 66% | 611 | 65% | 35% | ||||

| Any LAD ≥ 70% | No | 510 | 24% | 76% | <.001 | 334 | 16% | 84% | <.001 | 176 | 39% | 61% | <.001 |

| Yes | 1083 | 54% | 46% | 576 | 40% | 60% | 507 | 69% | 31% | ||||

| Maximum stenosis in any vessel (%) † |

50-69 | 44 | 11% | 89% | <.001 | 32 | 0% | 100% | <.001 | 12 | 42% | 58% | <.001 |

| 70-89 | 477 | 26% | 74% | 342 | 18% | 82% | 135 | 46% | 54% | ||||

| 90-99 | 495 | 43% | 57% | 258 | 32% | 68% | 237 | 56% | 44% | ||||

| 100 | 577 | 62% | 38% | 278 | 49% | 51% | 299 | 74% | 26% | ||||

| Any total occlusions | No | 1016 | 34% | 66% | <.001 | 632 | 23% | 77% | <.001 | 384 | 52% | 48% | <.001 |

| Yes | 577 | 62% | 38% | 278 | 49% | 51% | 299 | 74% | 26% | ||||

| Ejection fraction < 40% ‡ |

No | 1425 | 45% | 55% | 0.47 | 794 | 30% | 70% | <.01 | 631 | 63% | 37% | 0.54 |

| Yes | 82 | 49% | 51% | 64 | 47% | 53% | 18 | 56% | 44% | ||||

| CORE LAB MEASUREMENTS | |||||||||||||

| MJI (%) †§ | ≤ 25 | 158 | 18% | 82% | <.001 | 109 | 11% | 89% | <.001 | 49 | 35% | 65% | <.001 |

| 26-50 | 445 | 33% | 67% | 264 | 22% | 78% | 181 | 51% | 49% | ||||

| 51-75 | 467 | 58% | 42% | 241 | 46% | 54% | 226 | 71% | 29% | ||||

| 76-100 | 238 | 72% | 28% | 100 | 64% | 36% | 138 | 78% | 22% | ||||

| Proximal LAD ≥ 50% | No | 1378 | 41% | 59% | <.001 | 805 | 28% | 72% | <.001 | 573 | 60% | 40% | 0.03 |

| Yes | 214 | 62% | 38% | 104 | 52% | 48% | 110 | 71% | 29% | ||||

| Total number of lesions† |

≤ 3 | 313 | 25% | 75% | <.001 | 183 | 12% | 88% | <.001 | 130 | 43% | 57% | <.001 |

| 4 | 331 | 39% | 61% | 186 | 24% | 76% | 145 | 58% | 42% | ||||

| 5 | 300 | 46% | 54% | 173 | 32% | 68% | 127 | 65% | 35% | ||||

| 6 | 239 | 50% | 50% | 132 | 39% | 61% | 107 | 64% | 36% | ||||

| ≥ 7 | 409 | 59% | 41% | 235 | 47% | 53% | 174 | 75% | 25% | ||||

| No. lesions ≥ 50% † | ≤ 1 | 273 | 17% | 83% | <.001 | 191 | 8% | 92% | <.001 | 82 | 38% | 62% | <.001 |

| 2 | 401 | 33% | 67% | 224 | 25% | 75% | 177 | 44% | 66% | ||||

| 3 | 377 | 49% | 51% | 213 | 34% | 66% | 164 | 68% | 32% | ||||

| ≥ 4 | 541 | 62% | 38% | 281 | 49% | 51% | 260 | 77% | 23% | ||||

| No. class C lesions † | 0 | 698 | 28% | 72% | <.001 | 451 | 19% | 81% | <.001 | 247 | 45% | 55% | <.001 |

| 1 | 567 | 50% | 50% | 305 | 39% | 61% | 262 | 64% | 36% | ||||

| 2 | 221 | 63% | 37% | 109 | 50% | 50% | 112 | 77% | 23% | ||||

| 3+ | 106 | 76% | 24% | 44 | 59% | 41% | 62 | 89% | 11% | ||||

| Any non-discrete lesions |

No | 612 | 38% | 62% | <.001 | 358 | 25% | 75% | <.001 | 254 | 58% | 42% | 0.72 |

| Yes | 980 | 48% | 52% | 551 | 38% | 62% | 429 | 65% | 35% | ||||

Row percentages are presented. LAD indicates left anterior descending; MJI myocardial jeopardy index.

Chi-square p-values compare percentage of CABG-intended patients for groups defined by variables listed

Cochran-Armitage trend test P<0.05

Ejection fraction missing for 86 patients

Excludes patients with prior PCI (n=285)

RESULTS

Variation in Treatment Selection by Region and Time

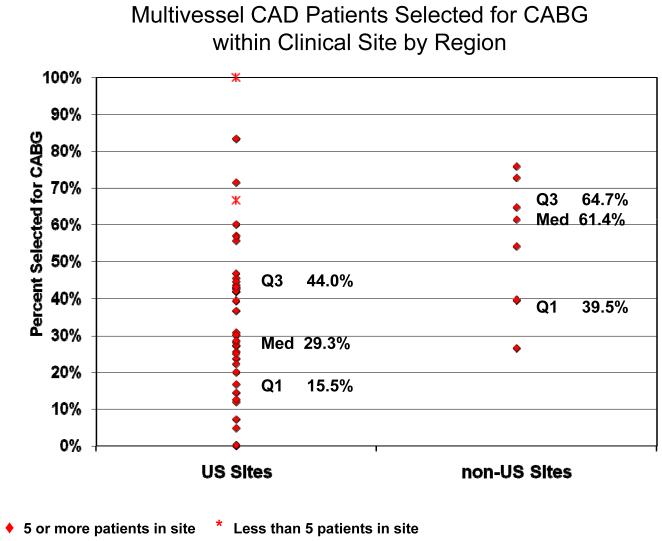

Among the 1593 diabetic patients with multivessel coronary disease, the decision to select CABG and PCI was declared in 44% (n=703) and 56% (n=890), respectively. Of 890 patients in whom PCI was declared, 434 (49%) were deemed suitable for CABG; of 703 patients intended for CABG, 79 (11%) were deemed suitable for PCI. The main reasons that investigators preferred CABG among CABG intended patients were the likelihood of success and safety, cited in 97% and 46% of patients, respectively, while the main reasons for preferring PCI among PCI intended patients were the likelihood of success and physician preference cited in 66% and 26% of patients. Selection of CABG rather than PCI was significantly lower in the US compared to non-US sites (31% vs. 61%, p<0.001). (Table 1) Outside of the US, selection of CABG ranged from 47% in Canada, 56% in Europe, 73% in Brazil, to 76% in Mexico (p<0.001 for trend). Substantial variability in the selection of revascularization strategy existed among participating sites within the US as well as outside of the US. (Figure 1) In both US and non-US regions, the decision to select CABG increased as disease burden increased, but within each MJI quartile, patients in the US were significantly less likely to be selected for CABG than those in other countries (p<0.001). (Figure 2) The date of randomization was also a factor that influenced the revascularization treatment decision. Among the 39 sites that enrolled patients prior to April 25, 2003, the availability of drug eluting stents was associated with an increased selection of PCI (p=0.0016). (Table 1).

Figure 1. Multivessel CAD Patients Selected for CABG within Clinical Site by Region.

Percentage of CABG-intended patients per site for US sites versus non-US sites. Q1 = first quartile; Q3 = third quartile; Med = median.

Figure 2. Likelihood of Intended CABG by Myocardial Jeopardy Index in US and non-US Sites.

Percentage of CABG-intended patients by myocardial jeopardy index (MJI) quartiles in US and non-US regions, among patients without prior PCI (n=1308). Note that for each quartile of MJI, non-US patients were more likely to be selected for CABG.

Patient Characteristics Associated with the Selection of CABG

Demographic and clinical factors associated with revascularization selection for the entire group and stratified by region are presented in Table 2. Overall, the recommendation for CABG was more common in patients who were white or Hispanic and had not undergone a prior PCI. In the US, patients who were male, age 65 years and older, and without a history of cerebrovascular events were more likely to be selected for CABG. Outside the US, less formal education, prior MI, and history of hypertension were associated with the selection of CABG.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics associated with the selection of CABG and PCI

|

All Patients (N=1593) |

US (n=910) |

Non-US (n=683) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Pts (n) |

Intended CABG |

Intended PCI |

P | n | Intended CABG |

Intended PCI |

P | n | Intended CABG |

Intended PCI |

P | ||

| DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE | |||||||||||||

| Sex | Men | 1149 | 46% | 54% | 0.002 | 640 | 34% | 66% | 0.002 | 509 | 62% | 38% | 0.70 |

| Women | 444 | 38% | 62% | 270 | 24% | 76% | 174 | 60% | 40% | ||||

| Age ≥ 65 years | No | 949 | 42% | 58% | 0.05 | 514 | 27% | 73% | 0.003 | 435 | 60% | 40% | 0.29 |

| Yes | 644 | 47% | 53% | 396 | 36% | 64% | 248 | 64% | 36% | ||||

| Race | White (NH) | 1055 | 47% | 53% | <.001 | 533 | 33% | 67% | 0.04 | 522 | 61% | 39% | 0.003 |

| Black (NH) | 251 | 31% | 69% | 208 | 24% | 76% | 43 | 67% | 33% | ||||

| Hispanic | 198 | 48% | 52% | 134 | 36% | 64% | 64 | 75% | 25% | ||||

| Other | 89 | 36% | 64% | 35 | 26% | 74% | 54 | 43% | 57% | ||||

| ≥ HS education | No | 620 | 55% | 45% | <.001 | 224 | 31% | 69% | 0.90 | 396 | 68% | 32% | <.001 |

| Yes | 968 | 37% | 63% | 682 | 31% | 69% | 286 | 52% | 48% | ||||

| Health insurance | Public | 1156 | 49% | 51% | <.001 | 519 | 33% | 67% | 0.26 | 637 | 61% | 39% | – |

| Private | 368 | 32% | 68% | 330 | 28% | 72% | 38 | 68% | 32% | ||||

| None/Self-pay | 67 | 27% | 73% | 60 | 28% | 72% | 7 | 14% | 86% | ||||

| CLINICAL PROFILE | |||||||||||||

| History of MI | No | 1066 | 41% | 59% | 0.001 | 641 | 30% | 70% | 0.35 | 425 | 59% | 41% | 0.02 |

| Yes | 501 | 50% | 50% | 255 | 33% | 67% | 246 | 67% | 33% | ||||

| Prior PCI | No | 1308 | 47% | 53% | <.001 | 714 | 34% | 66% | <.001 | 594 | 63% | 37% | 0.006 |

| Yes | 285 | 29% | 71% | 196 | 20% | 80% | 89 | 48% | 52% | ||||

| CHF | No | 1500 | 45% | 55% | 0.12 | 834 | 31% | 69% | 0.66 | 666 | 62% | 38% | 0.37 |

| Yes | 86 | 36% | 64% | 72 | 33% | 67% | 14 | 50% | 50% | ||||

| Angina class | No angina | 309 | 42% | 58% | 0.09 | 177 | 29% | 71% | 0.50 | 132 | 59% | 41% | 0.16 |

| Atypical | 329 | 42% | 58% | 220 | 35% | 65% | 109 | 57% | 43% | ||||

| Stable 1/2 | 684 | 46% | 54% | 336 | 32% | 68% | 348 | 61% | 39% | ||||

| Stable 3/4 | 139 | 50% | 50% | 69 | 29% | 71% | 70 | 70% | 30% | ||||

| Unstable | 132 | 36% | 64% | 108 | 26% | 74% | 24 | 79% | 21% | ||||

| Hypertension | No | 271 | 41% | 59% | 0.25 | 139 | 31% | 69% | 0.97 | 132 | 52% | 48% | 0.007 |

| Yes | 1301 | 45% | 55% | 766 | 31% | 69% | 535 | 64% | 36% | ||||

| Stroke/ TIA | No | 1426 | 45% | 55% | 0.008 | 794 | 32% | 68% | 0.02 | 632 | 61% | 39% | 0.65 |

| Yes | 160 | 34% | 66% | 112 | 21% | 79% | 48 | 65% | 35% | ||||

| Diabetes duration (Years) * |

< 5 | 499 | 43% | 57% | 0.5 | 278 | 27% | 73% | 0.07 | 221 | 62% | 38% | 0.99 |

| 5-10 | 395 | 45% | 55% | 209 | 31% | 69% | 186 | 61% | 39% | ||||

| > 10 | 695 | 45% | 55% | 420 | 34% | 66% | 275 | 61% | 39% | ||||

| Insulin use | No | 1171 | 47% | 53% | <.001 | 617 | 33% | 67% | 0.06 | 554 | 62% | 38% | 0.64 |

| Yes | 422 | 37% | 63% | 293 | 27% | 73% | 129 | 60% | 40% | ||||

Row percentages are presented.

Cochran-Armitage trend test P<0.05; HS = high school

Angiographic characteristics associated with the selection of revascularization strategy were consistent across US and non-US regions. (Table 3) Patients with more severe and extensive CAD, as indicated by triple vs. double vessel disease and extent of jeopardized myocardium, were more likely to be selected for CABG (both p<0.001). Other angiographic features related to the selection of CABG over PCI included: number of vessels with ≥70% stenosis; LAD stenosis≥50%; number of lesions ≥50% stenosis; and total number of lesions, irrespective of severity (all p<0.001). In addition, the choice of CABG was more common in patients with complex lesions, particularly total occlusions, class C lesions, and non-discrete lesions (all p<0.001). An ejection fraction <40% was related to the selection of CABG among patients in the US (p<0.01).

Independent Predictors of the Selection of CABG

The multivariable mixed model analysis indicated that after adjusting for patient characteristics, the odds of selecting CABG was higher among participants enrolled outside of the US compared to those enrolled in the US (OR=2.89, 95% CI: 1.22-6.83, p=0.017). (Figure 3) Selection of CABG versus PCI within clinical sites was driven largely by angiographic characteristics related to severity of CAD including presence of: triple vessel disease (OR=4.43, 95% CI: 3.35-5.85, p<0.001), proximal LAD stenosis ≥50% (OR=1.78, 95% CI: 1.20-2.64, p=0.005), any LAD stenosis ≥70% (OR=2.86, 95% CI: 2.11-3.88, p<0.001), total occlusion (OR=2.35, 95% CI: 1.76-3.13, p<0.001), and 2 or more class C lesions (OR=2.06, 95% CI: 1.44-2.95, ≤0.001). Age ≥ 65 years was also significantly associated with a preference for CABG (OR=1.43, 95% CI: 1.09-1.88, P=0.011). Conversely, CABG was less likely to be selected in patients who had previously undergone PCI (OR=0.45, 95% CI: 0.31-0.64, p<0.001) and those randomized after April 25, 2003 (OR=0.60, 95% CI: 0.43-0.83, p=0.003). The “intra-site” correlation estimated from the mixed model was ICC=0.25 (p<.001) indicating that the decision to select CABG versus PCI is strongly correlated with clinical site, although substantial within-site variability exists.

Figure 3. Adjusted Odds Ratio of CABG Selection.

Plot of independent predictors of the selection of CABG over PCI in diabetic patients with stable multivessel coronary disease. The red rectangles depict adjusted odds ratios; the horizontal lines depict the 95% confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

In this analysis of the predictors of the selection of revascularization strategy in patients from BARI 2D with DM, multivessel CAD and stable symptoms, we found that the choice of CABG rather than PCI was: 1) based largely on angiographic features related to a greater extent, severity and complexity of CAD; 2) more likely in patients >65 years of age and less likely in those who had undergone a prior PCI; 3) more likely in non-US than US centers, with significant site-specific preferences within the US and; 4) less likely following the introduction of drug eluting stents.

The multivariable analysis indicated that the angiographic findings that resulted in the selection of CABG, including chronic total occlusions, triple vessel disease, significant LAD disease, presence of type C lesions and extent of myocardial jeopardy reflect existing technical limitations and evidence-based long-term outcomes of PCI under specific anatomic circumstances. (1,4-7, 26) Among demographic and clinical factors, only older age (directly) and prior PCI (inversely) were associated with the selection of revascularization strategy. Older age was associated with a greater probability of selecting CABG. This finding may be due partially to the trial design. Since study inclusion criteria requires a minimum 5-year expected survival and stable presenting clinical status, elderly patients in the BARI 2D trial were, in general, likely to be in better health than elderly patients seen in routine practice.

Substantial regional and temporal variations in the selection of mode of revascularization were detected. Practice patterns in the US were notable for greater likelihood of PCI as 54% of diabetic patients with triple vessel disease were selected for PCI. The preference for surgical revascularization outside of the US was demonstrated at every level of myocardial disease burden and this regional discrepancy remained significant after adjusting for differences in clinical profiles and severity of CAD. The temporal shift towards a preference for PCI in BARI 2D following the availability of drug eluting stents is consistent with the very rapid implementation of this technology that occurred for both approved and off-label indications. There are several possible explanations for the regional variation in selection of CABG versus PCI. First, key high-level factors associated with the public healthcare systems in Brazil, Canada, Mexico, and Europe may result in a preference for surgical revascularization in these regions. Conversely, the greater use of PCI in the US may reflect an underlying philosophy that physicians and patients favor the less invasive strategy whenever technically and clinically feasible.

Impact of Original BARI Results

Because the original BARI trial pre-dated the use of stents or any device other than a balloon, its finding regarding the superiority of CABG over conventional balloon angioplasty in diabetic patients with multivessel CAD may have limited applicability in contemporary practice. McGuire and colleagues reported that 2 years after the Clinical Alert was issued, BARI results did not impact practice patterns in the US, which varied markedly throughout the country. (27) This is not surprising given the findings of nearly identical long-term survival in diabetic patients receiving PTCA versus CABG by physician selection in the original BARI Registry. (7) Remarkably, there has been little change in the angiographic predictors that drive a selection of CABG rather than PCI in patients with multivessel CAD, from the era when only balloon angioplasty was available. Data from the BARI registry, gathered between 1988 and 1991, indicated that just as in BARI 2D, the selection of CABG rather than PCI was driven by triple vs. double vessel disease, the number of significant lesions, and the presence of a proximal LAD lesion, type C lesion(s) or diffuse disease. (7)

Study Limitations

Several issues may limit the application of our findings. First, practice patterns in sites participating in BARI 2D may not reflect general practice. Specifically, study investigators and patients from Brazil, Mexico, Czech Republic, and Austria were each from a single center, and it is not clear that selection criteria at these sites represent those of their respective countries or regions. However, since treatment selection was at the discretion of local physicians, practice patterns in all participating sites likely reflect the community standards of their respective centers. Second, study enrollment occurred as the first generation of DES was introduced, which decreased the percentage of patients selected for CABG. Newer generations of DES may have already resulted in more patients being selected for PCI. Third, a factor that did not predict selection of CABG rather than PCI in this model, such as an LVEF<40% may have resulted from the relatively low number of patients with that finding enrolled in BARI 2D. Despite these limitations, the data presented were prospectively gathered on more than 1500 patients across a broad spectrum of clinical sites and analyzed by an independent data center. Furthermore, this analysis of the selection of revascularization strategy will be critical to the analysis of the primary study results and subsequent comparisons of those patients undergoing CABG versus PCI.

CONCLUSION

Among patients with diabetes and multivessel CAD with stable symptoms in the BARI 2D trial, the decision to select CABG over PCI was driven largely by angiographic features associated with extent, location, and nature of CAD. Geographic region also played an important role, as a greater preference for surgical revascularization was demonstrated in countries outside of the US irrespective of other factors. Moreover, treatment selection varied substantially across geographic regions and across clinical sites within regions, reflecting a lack of consensus regarding optimal therapy in contemporary practice. Finally, the introduction of the first generation drug eluting stent decreased the likelihood of the selection of CABG.

Acknowledgments

The Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes (BARI 2D) is funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (U01 HL061744, U01 HL061746, U01 HL061748, U01 HL063804). BARI 2D receives significant supplemental funding from GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb Medical Imaging, Inc., Astellas Pharma US, Inc., Merck & Co., Inc, Abbott Laboratories, Inc., and Pfizer, Inc. and generous support from Abbott Laboratories Ltd., MediSense Products, Bayer Diagnostics, Becton, Dickinson and Company, J. R. Carlson Laboratories, Inc., Centocor, Inc.,,Eli Lilly and Company, LipoScience, Inc., Merck Sante, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Novo Nordisk, Inc

ABBREVIATION LIST

- CABG

coronary artery bypass graft

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- BARI 2D

Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes

- US

United States

- DES

drug-eluting stents

- MJI

myocardial jeopardy index

- CI

confidence interval

- OR

Odds ratio

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts: Dr. Feit is a major shareholder of Eli Lilly and Novartis

CLINICAL TRIAL INFO Trial name: Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation in Type 2 Diabetes (BARI 2D)

Registry URL: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00006305

Registry number NCT00006305

REFERENCES

- 1.Barsness GW, Peterson ED, Ohman EM, et al. Relationship between diabetes mellitus and long-term survival after coronary bypass and angioplasty. Circulation. 1997 Oct 21;96(8):2551–2556. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.8.2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alderman EL, Corley SD, Fisher LD, et al. Five-year angiographic follow-up of factors associated with progression of coronary artery disease in the Coronary Artery Surgery Study (CASS). CASS Participating Investigators and Staff. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22(4):1141–1154. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90429-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thourani VH, Weintraub WS, Stein B, et al. Influence of diabetes mellitus on early and late outcome after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67(4):1045–1052. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kip KE, Faxon DP, Detre KM, et al. Coronary angioplasty in diabetic patients. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty Registry. Circulation. 1996 Oct 15;94(8):1818–1825. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.8.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation (BARI) Investigators Comparison of coronary bypass surgery with angioplasty in patients with multivessel disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(4):217–225. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607253350401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Heart L, and Blood Institute [Accessed July 27, 2006];Bypass over angioplasty for patients with diabetes. Available at: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/databases/alerts/bypass_diabetes.html.

- 7.Feit F, Brooks MM, Sopko G, et al. Long-Term Clinical Outcome in the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation Registry: Comparison With the Randomized Trial. Circulation. 2000;101(24):2795–2802. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.24.2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holmes DR, Jr., Leon MB, Moses JW, et al. Analysis of 1-year clinical outcomes in the SIRIUS trial: a randomized trial of a sirolimus-eluting stent versus a standard stent in patients at high risk for coronary restenosis. Circulation. 2004 Feb 10;109(5):634–640. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000112572.57794.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moses JW, Leon MB, Popma JJ, et al. Sirolimus-eluting stents versus standard stents in patients with stenosis in a native coronary artery. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(14):1315–1323. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moussa I, Leon MB, Baim DS, et al. Impact of sirolimus-eluting stents on outcome in diabetic patients: a SIRIUS (SIRolImUS-coated Bx Velocity balloon-expandable stent in the treatment of patients with de novo coronary artery lesions) substudy. Circulation. 2004;109(19):2273–2278. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000129767.45513.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone GW, Ellis SG, Cox DA, et al. One-year clinical results with the slow-release, polymer-based, paclitaxel-eluting TAXUS stent: the TAXUS-IV trial. Circulation. 2004;109(16):1942–1947. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127110.49192.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatt DL, Marso SP, Lincoff AM, et al. Abciximab reduces mortality in diabetics following percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(4):922–928. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00650-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feit F, Manoukian SV, Ebrahimi R, et al. Safety and efficacy of bivalirudin monotherapy in patients with diabetes mellitus and acute coronary syndromes: a report from the ACUITY trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1645–52. 51. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.11.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins R, Armitage J, Parish S, et al. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol-lowering with simvastatin in 5963 people with diabetes: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9374):2005–2016. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13636-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonas M, Reicher-Reiss H, Boyko V, et al. Usefulness of beta-blocker therapy in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease. Bezafibrate Infarction Prevention (BIP) Study Group. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77(15):1273–1277. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Investigators HOPEHS Effects of ramipril on cardiovascular and microvascular outcomes in people with diabetes mellitus: results of the HOPE study and MICRO-HOPE substudy. Lancet. 2000;355(9200):253–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith SC, Jr., Dove JT, Jacobs AK, et al. ACC/AHA Guidelines for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (Revision of the 1993 PTCA Guidelines)--Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1993 Guidelines for Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty) Endorsed by the Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions. Circulation. 2001;103(24):3019–3041. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.24.3019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eagle KA, Guyton RA, Davidoff R, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for coronary artery bypass graft surgery: A report of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association task force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to revise the 1991 Guidelines for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery) J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34(4):1262–1347. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00389-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pilote L, Califf RM, Sapp S, et al. Regional variation across the United States in the management of acute myocardial infarction. GUSTO-1 Investigators. Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(9):565–572. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508313330907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van de Werf F, Topol EJ, Lee KL, et al. Variations in patient management and outcomes for acute myocardial infarction in the United States and other countries. Results from the GUSTO trial. Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries. Jama. 1995;273(20):1586–1591. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.20.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brooks MM, Frye RL, Genuth S, et al. Hypotheses, design, and methods for the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes (BARI 2D) Trial. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97(12A):9G–19G. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The BARI 2D Study Group Baseline characteristics of patients with diabetes and coronary artery disease enrolled in the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes (BARI 2D) trial. Am Heart J. 2008;156:528–536. e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alderman EL, Stadius M. The angiographic definitions of the bypass angioplasty revascularization investigation. CORON. ARTERY DIS. 1992;3(12):1189. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldstein H. Multilevel statistical models. John Wiley; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd Edition John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith SC, Jr., Faxon D, Cascio W, et al. Prevention Conference VI: Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease: Writing Group VI: revascularization in diabetic patients. Circulation. 2002;105(18):e165–169. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013957.30622.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGuire DK, Anstrom KJ, Peterson ED. Influence of the Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Diabetic Clinical Alert on practice patterns: results from the National Cardiovascular Network Database. Circulation. 2003;107(14):1864–1870. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000064901.21619.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]