Abstract

Objectives

A rapid, sensitive and robust ultra-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) method was developed for the quantification of four major polymyxin B components (polymyxin B1, polymyxin B2, polymyxin B3 and isoleucine-polymyxin B1) in serum and epithelial lining fluid (ELF) samples.

Methods

A Waters Acquity UPLC HSS C18 column was used with 0.1% formic acid in water/acetonitrile as mobile phases. Analysis was performed in a positive ionization mode with multiple-reactions monitoring scan type. Five percent trichloroacetic acid was used to precipitate proteins in biological samples and to increase the sensitivity of detection.

Results

Our results showed a linear concentration range of 0.0065–3.2 mg/L for all the major polymyxin B components in both serum and ELF, respectively; the interday variation was <10% and the accuracy was 88%–115%. The validated method was used to characterize the pharmacokinetics (serum and ELF) of polymyxin B in mice.

Conclusions

This is the first report, to date, examining the individual pharmacokinetics of various polymyxin B components in mice. Our results revealed no considerable differences in clearances among the components. The limited exposure of polymyxin B in ELF observed was consistent with the less favourable efficacy of polymyxin B reported for the treatment of pulmonary infections. This method can be used to further examine the pharmacokinetics of polymyxin B in a variety of clinical and experimental settings.

Keywords: polymyxin, UPLC-MS/MS, biological samples

Introduction

Polymyxin B is increasingly used as the last resort treatment for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections.1–3 Due to its unique chemical structure and mechanism of action, polymyxin B has broad-spectrum activity against many Gram-negative bacteria.4 Although it has been available for several decades, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data on polymyxin B remain limited.

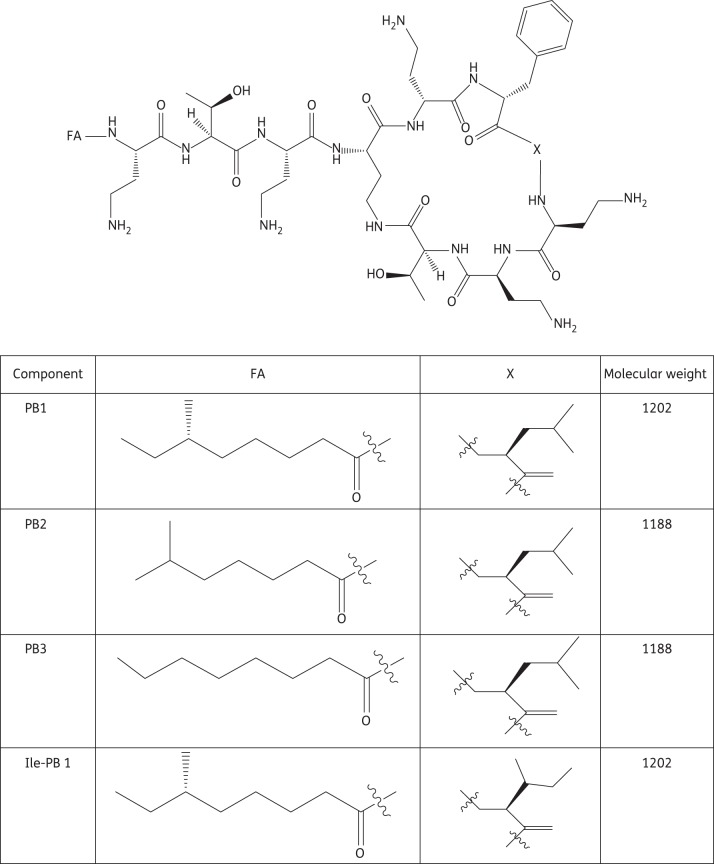

Polymyxin B [US Pharmacopeia (USP)] is commercially available as a mixture of several closely related polypeptides, obtained from cultures of various strains of Bacillus polymyxa and related species.5 The major components of polymyxin B (USP) are polymyxin B1, B2 and B3 and isoleucine-polymyxin B1 (PB1, PB2, PB3 and Ile-PB1, respectively) (Figure 1),6 the proportions of which have been reported to be 73.5%, 13.7%, 4.2% and 8.6%, respectively.7 Microbiological assays recommended by the FDA focus on the overall antimicrobial activity of the mixture, rather than on the quantity of each component.8 These methods generally lack specificity and the ability to distinguish various elements of this multicomponent drug.9,10 However, different components may not exhibit equivalent pharmacological activity and toxic propensity, which make it necessary to separate major polymyxin B components using a validated method.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of PB1, PB2, PB3 and Ile-PB1.

On the other hand, an HPLC method with UV detection could achieve satisfactory resolution for >30 polymyxin B components.10 However, as a peptide, polymyxin B is not sensitive to UV detection. Thus, the lower limit of detection of the method is significantly higher than clinically relevant concentrations, severely limiting the clinical application of this method.

Finally, Cheng et al.11 developed a liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method to quantify PB1 and PB2 in rat plasma. Nevertheless, the method did not take into consideration different components with identical molecular weight, i.e. PB1 versus Ile-PB1 and PB2 versus PB3, which might affect the accuracy of this method and its application to in vivo studies. In that study, trichloroacetic acid was used to precipitate proteins in plasma samples, which increased the sensitivity of detecting the analytes under MS/MS.11 However, it was found that a high percentage of trichloroacetic acid compromised the separation of components with a similar structure and resulted in large variations in the recovery of samples. Besides, additional dilution and centrifugation steps were needed to prepare the samples if a high percentage of trichloroacetic acid was used.11

Although polymyxin B is often believed to distribute poorly in the lower respiratory tract, i.e. epithelial lining fluid (ELF), comprehensive clinical or experimental data are not available to support this viewpoint.12,13 This study sought to develop a sensitive ultra-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) method to quantify major polymyxin B components and to apply the method for the characterization of serum as well as pulmonary pharmacokinetics in mice.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Polymyxin B sulphate (USP) powder and trichloroacetic acid were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Purified standards of PB1, PB2, PB3 and Ile-PB1 were obtained by a preparative-scale liquid chromatography method and verified as detailed previously.14 Carbutamide was purchased from Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI, USA). LC-MS grade acetonitrile and water were obtained from Mallinckrodt Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ, USA). LC-MS grade formic acid was purchased from Fluka Analytical (Buchs, Switzerland).

Instrumentation and conditions

UPLC

Major polymyxin B components and carbutamide (internal standard) were resolved using Waters UPLC Acquity™ with the following conditions: column, Acquity UPLC HSS C18 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm internal diameter, 1.7 μm) from Waters (Milford, MA, USA); mobile phase A, 0.1% formic acid in water; mobile phase B, 100% acetonitrile; gradient, initial: 5% B, 0–3 min: 5%–15% B, 3–4.5 min: 15%–18% B, 4.5–5.5 min: 18%–80% B, 5.5–5.7 min: 80% B, 5.7–6 min: 80%–95% B, 6–6.5 min: 95% B, 6.5–6.6 min: 95%–5% B, 6.6–7 min: 5% B (equilibrium time); flow rate, 0.5 mL/min; column temperature, 45°C; autosampler temperature, 20°C; and injection volume, 0.01 mL.

MS/MS

An API 5500-Qtrap triple quadrupole mass spectrometer from Applied Biosystems/MDS SCIEX (Foster City, CA, USA) equipped with a TurboIonSpray™ source was operated in the positive-ion mode. Optimal settings were as follows: ion-spray voltage, 5.5 kV; ion source temperature, 400°C; gas 1, 20 psi; gas 2, 20 psi; curtain gas, 30 psi; and collision gas, medium.

The quantification was performed using a multiple-reactions monitoring (MRM) method with the transitions of m/z 402 → m/z 101 for PB1, m/z 397 → m/z 101 for PB2, m/z 398 → m/z 101 for PB3, m/z 402 → m/z 101 for Ile-PB1 and m/z 272 → m/z 74 for carbutamide (internal standard). Additional compound-dependent parameters in the MRM mode for the four components of polymyxin B are summarized in Table 1. Analyte concentrations were determined by the software Analyst 1.5.2.

Table 1.

Compound-dependent parameters for PB1, PB2, PB3, Ile-PB1 and carbutamide (internal standard)

| Analyte | Dwell time (ms) | DP (V) | CE (V) | CXP (V) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB1 | 100 | 21 | 23 | 8 |

| PB2 | 100 | 101 | 23 | 8 |

| PB3 | 100 | 11 | 23 | 8 |

| Ile-PB1 | 100 | 51 | 23 | 8 |

| Carbutamide | 100 | 120 | 15 | 12 |

DP, declustering potential; CE, collision energy; CXP, collision cell exit potential.

Preparation of standards and quality control (QC) samples

Standard stock solutions of PB1, PB2, PB3 and Ile-PB1 were prepared by dissolving the required amount of the reference standards in water. A mixture stock solution was prepared by mixing equal amounts of each component. The working solutions for the standard curve were obtained by serial diluting the prepared mixture stock solution with water. A standard solution of the internal standard was prepared by dissolving carbutamide in acetonitrile at a final concentration of 0.05 mg/L.

The serum/ELF samples for the calibration curve were prepared by spiking 0.02 mL of the above working solutions into 0.18 mL of blank serum/ELF samples to yield the concentrations of 0.00625, 0.0125, 0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1.6 and 3.2 mg/L for each component. The QC samples were prepared at low, medium and high concentrations (0.0125, 0.4 and 1.6 mg/L) and were stored at −80°C until analysis.

Sample preparation

The serum and ELF samples (0.2 mL) were spiked with 0.02 mL of the internal standard. To precipitate the proteins, 0.2 mL of 5% trichloroacetic acid was added, followed by 1 min of vortexing. After centrifugation at 18 000 g for 15 min, the supernatant was transferred to a new tube and evaporated to dryness under a stream of nitrogen. The residue was reconstituted in 0.1 mL of mobile phase (0.1% formic acid in water:acetonitrile = 50 : 50) and centrifuged at 18 000 g for 15 min. Ten microlitres of supernatant was injected into the UPLC-MS/MS for quantitative analysis. The concentration of drug in ELF (CELF) was corrected using the equation: CELF = CBALF × ureaserum/ureaBALF, where CBALF is the concentration of drug in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), and ureaBALF and ureaserum are the concentrations of urea in BALF and serum, respectively. The concentrations of urea in plasma and BALF samples were analysed using a commercially available assay kit (Quantichrom™ Urea Assay Kit, BioAssay System, Hayward, CA, USA) and measured on a Synergy2 microplate reader (BioTek Instrument, Winooski, VT, USA).

Method validation

Calibration curve and lower limit of quantification (LLOQ)

Calibration curves were prepared according to the method described above. The linearity of each calibration curve was determined by plotting the peak area ratio of various polymyxin B components to the internal standard in mouse serum/ELF samples versus concentrations. A least-square linear regression method (1/x2 weighting) was used to determine the slope, intercept and correlation coefficient of the linear regression equation. The LLOQ was defined as the lowest standard on the calibration curve with a peak response ≥10 times that of the blank response, precision of 15% and accuracy of 85%–115%.

Precision and accuracy

The intraday and interday precision and accuracy of the method were determined with five replicates of QC samples, at three different concentrations on the same day and on three consecutive days, respectively.

Extraction recovery and matrix effect

Extraction recoveries of various polymyxin B components were determined by comparing the peak areas obtained from blank serum/ELF samples spiked with the analytes before and after extraction. The matrix effect was determined by comparing the peak area of blank serum/ELF samples spiked with analytes and the internal standard with those of the standard solutions dried and reconstituted with the mobile phase.

Stability

Short-term (25°C for 6 h), post-processing (20°C for 12 h), long-term (−80°C for 30 days) and three freeze–thaw cycle stabilities were determined.

Pharmacokinetic study

The animal protocol used in this study was approved by the University of Houston Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All the animals were cared for in accordance with the National Research Council recommendations. Twenty-four Swiss Webster female mice (20–23 g, Harlan Laboratory, Indianapolis, IN, USA) were intravenously administered 3 mg/kg polymyxin B (USP) solution through the tail vein. At each timepoint (0.1, 0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 6 h), four mice were sacrificed for blood and ELF sample collection. The blood samples were clotted on crushed ice and the serum was obtained by centrifugation. The ELF samples were obtained by bronchoalveolar lavage and polymyxin B concentrations in ELF samples were corrected by urea content as described above. All the serum and ELF samples were stored at −80°C until analysis. The concentration of each component given was assayed by the validated UPLC-MS/MS method. Naive data averaging was used to determine the drug exposures in serum and ELF. Pharmacokinetic parameters and drug exposure in ELF were calculated by WinNonlin 3.3 (Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, CA, USA) using a one-compartment model (for serum concentrations) and non-compartment method (for ELF concentrations), respectively.

Results

Analysis method optimization

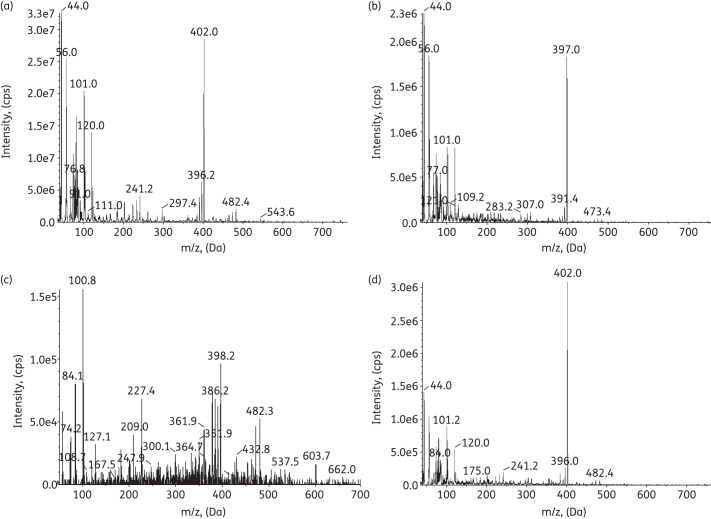

The chromatography was optimized by employing a gradient elution that started at a very low acetonitrile percentage (5%) for up to 3 min to achieve a good separation for all the components. After 4.5 min, the acetonitrile percentage was increased to 80% to obtain sharp and symmetrical peaks. The positive mode was selected for optimal sensitivity for all the components. The assay was much more sensitive monitoring triply charged molecules compared with doubly charged counterparts (10-fold increase) (data not shown). The MRM scan type was used to monitor both pseudomolecular and fragments ions, which made the method more specific. The components were identified by the elution sequence and confirmed by pseudomolecular weight and secondary quadrupole mass (MS2) full scan. The MS2 full-scan mass chromatograms of PB1, PB2, PB3 and Ile-PB1 are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

MS2 full scans for PB1 (a), PB2 (b), PB3 (c) and Ile-PB1 (d).

Method validation

Assay specificity and linearity

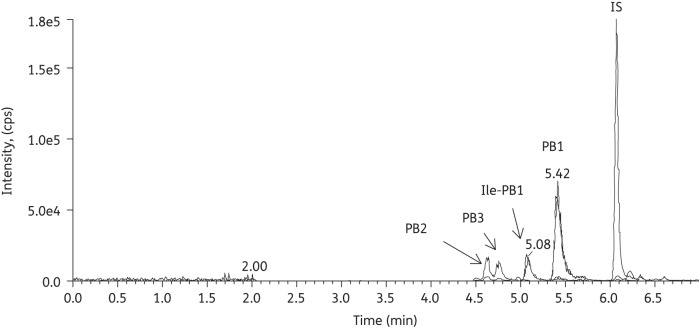

All of the method validation was conducted in blank mouse serum; no interferences from endogenous compounds were observed (data not shown). A representative chromatogram of a serum sample obtained after the intravenous administration of polymyxin B sulphate (USP) is shown in Figure 3. Polymyxin B components with identical molecular weight (e.g. PB1 and Ile-PB1) were separated in the chromatography. The linear ranges of all the analytes were 0.00625–3.2 mg/L in both serum and ELF samples.

Figure 3.

Chromatograms of PB1, PB2, PB3, Ile-PB1 and carbutamide [internal standard (IS)] in a mouse serum sample.

Accuracy and precision

The intraday and interday accuracy and precision for all the polymyxin B components in serum and ELF samples were well within the 15% acceptable range.

Extraction recovery and matrix effect

The mean extraction recoveries of QC samples at three concentration levels were 95.6%–115.6% in mouse serum and 89.6%–105.9% in ELF. The results demonstrated that using 5% trichloroacetic acid to precipitate proteins in serum and ELF samples was satisfactory.

With regard to the matrix effect, all the calculated values were between 91.0% and 119.2%. No significant matrix effect for PB1, PB2, PB3, Ile-PB1 and the internal standard was observed, indicating that no coeluting substance influenced the ionization of the analytes and internal standard.

Stability

The concentrations of PB1, PB2, PB3 and Ile-PB1 measured in the stability study were all between 85% and 115% of the initial values, indicating that all the analytes in mouse serum and ELF samples were stable for 6 h at 25°C, 30 days at −80°C and three freeze–thaw cycles before pre-treatment. In addition, all the analytes were stable for 12 h in the autosampler after pre-treatment.

Pharmacokinetic application

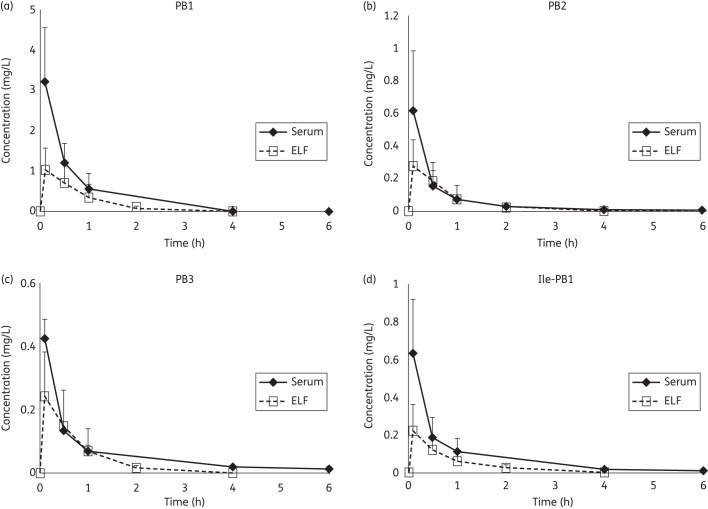

The validated method was employed to study the pharmacokinetics and penetration to ELF of polymyxin B (USP) in Swiss Webster mice. The concentration–time profiles for various polymyxin B components in serum and ELF after an intravenous administration are shown in Figure 4. The best-fit pharmacokinetic parameter estimates of all the analytes are presented in Table 2. The pharmacokinetics of PB1, PB2, PB3 and Ile-PB1 appeared to be similar. After an intravenous injection, PB1, PB2, PB3 and Ile-PB1 reached maximum ELF concentrations (Cmax) of 1.02 ± 0.54, 0.28 ± 0.16, 0.25 ± 0.13 and 0.23 ± 0.13 mg/L, respectively, at 6 min. The ratio of AUCELF/AUCserum was 0.60, 0.82, 0.87 and 0.67 for PB1, PB2, PB3 and Ile-PB1, respectively.

Figure 4.

Serum and ELF concentrations of PB1, PB2, PB3 and Ile-PB1 after an intravenous administration of 3 mg/kg polymyxin B (USP) (n = 4). Drug concentrations in ELF could only be detected for up to 4 h post-dose.

Table 2.

Best-fit pharmacokinetic parameters of PB1, PB2, PB3 and Ile-PB1 after intravenous administration of 3 mg/kg polymyxin (USP) (n = 4)

| Analyte | AUCserum (mg · h/L) | t½ (h) | CL (mL/h/kg) | Vss (mL/kg) | AUCELF (mg · h/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB1 | 2.7 | 0.4 | 1156.7 | 604.8 | 1.6 |

| PB2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 974.1 | 350.8 | 0.2 |

| PB3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 978.5 | 449.9 | 0.2 |

| Ile-PB1 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 1125.5 | 506.0 | 0.4 |

AUCserum and AUCELF, area under the concentration–time curve (AUC)0–∞ in serum and ELF, respectively; t½, elimination half-life; CL, clearance; Vss, volume of distribution at steady-state.

Discussion

To date, there is a very limited understanding of the properties of individual polymyxin B components. Most pre-clinical and clinical studies evaluated polymyxin B in agglomerates, based on an implicit assumption that all the polymyxin B components have identical pharmacological properties. However, it is possible that one component is more toxic than the others or one component may have a greater antimicrobial activity than the others. Polymyxin B (USP) is commercially available as a chemically undefined mixture. We have previously investigated the in vitro potency of various polymyxin B components.14 Investigations on the nephrotoxicity of individual polymyxin B component are ongoing in our laboratory. Since polymyxin B may need to play an important role in combating multidrug-resistant Gram-negative organisms in the future, examining each polymyxin B component individually would enhance the interpretation of the pharmacokinetic data. A rapid, sensitive and robust UPLC-MS/MS method was developed and validated for the quantification of four major polymyxin B components in serum and ELF. To our knowledge, this is the first analytical method to separate and quantify the four major polymyxin B components individually in the clinically relevant concentration ranges. The separation of the four major components was rapid using a gradient UPLC method (7 min), as compared with the conventional HPLC method (60 min).10 The assay was much more sensitive monitoring triply charged molecules compared with doubly charged counterparts.11 In addition, the four major polymyxin B components were confirmed by pseudomolecular and MS2 fragments. The LLOQ reported for the four major components of polymyxin B were the lowest to date.

Trichloroacetic acid was used to precipitate proteins in serum and ELF samples, which increased the sensitivity of detecting the analytes under MS/MS. Since higher concentrations of trichloroacetic acid could cause the assay to be inaccurate, 5% trichloroacetic acid was chosen to precipitate the proteins in our samples, which was found to achieve satisfactory resolution and sensitivity in various biological matrices (i.e. serum and ELF samples). This sensitive method allowed further application to in vivo (pharmacokinetic) studies, regardless of the modelling approach used (e.g. naive pooling, compartmental analysis or population analysis).

This is the first report to date examining the pharmacokinetics of various polymyxin B major components in mice. There were no major differences in the pharmacokinetics among the four components. The limited exposure of polymyxin B in ELF observed was consistent with the less favourable efficacy of polymyxin B reported for the treatment of pulmonary infections.15,16 Further validation of this method in other biological matrices is ongoing to fully characterize the biodistribution of polymyxin B.

Conclusions

A rapid, sensitive and robust UPLC-MS/MS method was developed and validated to quantify four major polymyxin B components in biological samples. The application of this analytical method to characterize the concentration–time profiles in serum and ELF showed no significant differences in the pharmacokinetics among the four components and the limited exposure of polymyxin B in ELF.

Funding

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R15AI089671-01).

Transparency declarations

V. H. T. has received unrestricted research grants from AstraZeneca, Achaogen, Merck and Ortho-McNeil; he has also received speaking honoraria from AstraZeneca and Merck. All other authors: none to declare.

References

- 1.Tam VH, Schilling AN, Vo G, et al. Pharmacodynamics of polymyxin B against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:3624–30. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.9.3624-3630.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gales AC, Jones RN, Sader HS. Global assessment of the antimicrobial activity of polymyxin B against 54 731 clinical isolates of Gram-negative bacilli: report from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance programme (2001–2004) Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:315–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pastewski AA, Caruso P, Parris AR, et al. Parenteral polymyxin B use in patients with multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteremia and urinary tract infections: a retrospective case series. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:1177–87. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bratu S, Quale J, Cebular S, et al. Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Brooklyn, New York: molecular epidemiology and in vitro activity of polymyxin B. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;24:196–201. doi: 10.1007/s10096-005-1294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shoji J, Hinoo H, Wakisaka Y, et al. Isolation of two new polymyxin group antibiotics. (Studies on antibiotics from the genus Bacillus. XX) J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1977;30:1029–34. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.30.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orwa JA, Govaerts C, Busson R, et al. Isolation and structural characterization of polymyxin B components. J Chromatogr A. 2001;912:369–73. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)00585-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He J, Ledesma KR, Lam WY, et al. Variability of polymyxin B major components in commercial formulations. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;35:308–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simon HJ, Yin EJ. Microbioassay of antimicrobial agents. Appl Microbiol. 1970;19:573–9. doi: 10.1128/am.19.4.573-579.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He J, Figueroa DA, Lim TP, et al. Stability of polymyxin B sulfate diluted in 0.9% sodium chloride injection and stored at 4 or 25°C. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2010;67:1191–4. doi: 10.2146/ajhp090472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orwa JA, Van Gerven A, Roets E, et al. Liquid chromatography of polymyxin B sulphate. J Chromatogr A. 2000;870:237–43. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(99)00936-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng C, Liu S, Xiao D, et al. LC-MS/MS method development and validation for the determination of polymyxins and vancomycin in rat plasma. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2010;878:2831–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2010.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan Z, Tam VH. Polymyxin B: a new strategy for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative organisms. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;17:661–8. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.5.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiem S, Schentag JJ. Interpretation of antibiotic concentration ratios measured in epithelial lining fluid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:24–36. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00133-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tam VH, Cao H, Ledesma KR, et al. In vitro potency of various polymyxin B components. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:4490–1. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00119-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furtado GH, d'Azevedo PA, Santos AF, et al. Intravenous polymyxin B for the treatment of nosocomial pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007;30:315–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holloway KP, Rouphael NG, Wells JB, et al. Polymyxin B and doxycycline use in patients with multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections in the intensive care unit. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1939–45. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]