Abstract

Background

Reduced atazanavir exposure has been demonstrated during pregnancy with standard atazanavir/ritonavir dosing. We studied an increased dose during the third trimester of pregnancy.

Methods

IMPAACT 1026s is a prospective, non-blinded pharmacokinetic study of HIV-infected pregnant women taking antiretrovirals for clinical indications, including two cohorts (with or without tenofovir) receiving atazanavir/ritonavir 300/100 mg once daily during the 2nd trimester (2nd trim), 400/100 mg during the 3rd trimester (3rd trim) and 300/100 mg postpartum (PP). Intensive steady-state 24-hour pharmacokinetic profiles were performed. Atazanavir concentrations were measured by HPLC. Pharmacokinetic targets were the 10th percentile atazanavir AUC (29.4 mcg*hr/mL) in non-pregnant adults on standard dose and 0.15 mcg/mL, minimum trough concentration.

Results

Atazanavir pharmacokinetic data were available for 37 women without tenofovir, 35 with tenofovir; Median (range) pharmacokinetic parameters are presented for 2nd, 3rd trim and PP and number who met target/total. * indicates p<0.05 compared to PP.

Atazanavir without tenofovir

AUC 30.5 (9.19–93.8), 45.7 (11–88.3), and 48.8 (9.9–112.2) mcg-hr/mL, and 8/14, 29/37 and 27/34 met target. C24h was 0.49 (0.09–4.09), 0.71 (0.14–2.09), and 0.90 (0.05–2.73) mcg/mL; 13/14, 36/37 and 29/34 met target.

Atazanavir with tenofovir

AUC 26.2 (6.8–60.9)*, 37.7 (0.72–88.2)*, and 58.6 (6–149) mcg-hr/mL, and 7/17, 23/32 and 27/29 met target. C24h was 0.44 (0.12–1.06)*, 0.57 (0.02–2.06)*, and 1.26 (0.09–5.43) mcg/mL; 7/17, 23/32 and 27/29 met target. Atazanavir/ritonavir was well tolerated with no unanticipated adverse events.

Conclusions

Atazanavir/ritonavir increased to 400/100mg provides adequate atazanavir exposure during the third trimester and should be considered during the second trimester.

Keywords: atazanavir, tenofovir, pharmacokinetics, pregnancy, HIV, mother to child transmission

INTRODUCTION

Current US Public Health Service guidelines on the management of HIV-infected women during pregnancy recommend use of a combination regimen consisting of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and either one protease inhibitor or one non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission and to maintain maternal health.1 Previous studies of the pharmacokinetics in pregnant women of several protease inhibitors, including indinavir, lopinavir, nelfinavir and saquinavir, have demonstrated reduced plasma protease inhibitor concentrations during pregnancy.2–6

Atazanavir plus low dose ritonavir administered once daily is one of the preferred protease inhibitor based regimens during pregnancy, often in combination with tenofovir and emtricitabine to make a complete once daily antiretroviral regimen.1 Three studies have evaluated atazanavir pharmacokinetics with the adult standard dose (300 mg with 100 mg ritonavir) during pregnancy. Atazanavir AUC was lower during pregnancy than in historic data from HIV-infected non-pregnant patients.7–9 Two of these studies reported a 25% reduction in atazanavir exposure during pregnancy compared to postpartum.8, 9 In non-pregnant adults, co-administration of tenofovir with atazanavir reduces atazanavir exposure by approximately 25%.10 A similar reduction was seen in the one pharmacokinetic study that included a group of pregnant women receiving both atazanavir and tenofovir, so that pregnant women receiving both drugs had a roughly 50% reduction in atazanavir exposure compared to postpartum women not receiving tenofovir.8 A recently published systematic review included the literature about pharmacokinetic, efficacy and safety of atazanavir in pregnancy.11

Reduced atazanavir concentrations during pregnancy may lead to less effective control of viral replication both during and after pregnancy, especially in treatment experienced women, as virologic response to atazanavir has been shown to inversely correlate with the ratio of the trough atazanavir concentration divided by the number of protease resistance mutations.12, 13

Use of an increased dose of atazanavir of 400 mg with 100 mg ritonavir without tenofovir during third trimester pregnancy has been investigated in one study.9 In this study, pregnant women receiving the increased dose without tenofovir had an atazanavir AUC equivalent to that seen in historic nonpregnant HIV-infected controls receiving standard-dose atazanavir without tenofovir. There are no data available describing the pharmacokinetics of an increased dose of atazanavir with ritonavir when used with tenofovir during pregnancy.

The goal of this study was to describe the pharmacokinetics of increased dose atazanavir (400 mg) in combination with ritonavir during the third trimester of pregnancy both with and without concomitant tenofovir use.

METHODS

International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials (IMPAACT) Network Protocol 1026s is an ongoing, multi-center, prospective study to evaluate the pharmacokinetics of antiretrovirals among pregnant HIV-infected women from USA, Thailand, Brazil and Argentina. [ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00042289].

Eligibility criteria for this atazanavir arm of P1026s were: HIV infected pregnant women receiving standard dose atazanavir/ritonavir of 300mg/100mg once daily, increasing to 400/100 mg after 30 weeks of pregnancy and returning to the previous dose after delivery. Exclusion criteria were: concurrent use of medications known to interfere with the absorption, metabolism or clearance of atazanavir or ritonavir, multiple gestation pregnancy, and clinical or laboratory toxicity that, in the opinion of the site investigator, would likely require a change in the medication regimen during the study. Local institutional review boards approved the protocol at all participating sites and signed informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to participation. Subjects continued to take their prescribed medications throughout the course of their pregnancies. The choice of additional antiretrovirals was determined by the subject’s physician, who prescribed all medications and remained responsible for her clinical management throughout the study. Both women and infants were followed for 6 months after delivery.

Atazanavir pharmacokinetics were evaluated in women who enrolled during the second trimester of pregnancy between 20 and 26 weeks gestation and in all subjects between 30 and 36 weeks gestation and between 2 and 3 weeks after delivery. Atazanavir area under the concentration versus time curve (AUC0-24) was calculated for each woman and compared to the atazanavir AUC0-24 in non-pregnant adult populations.14 Each subject’s physician was notified of the subject’s plasma concentrations and AUC0-24 within two weeks of antepartum sampling. If the AUC0-24 was below the 10th percentile in non-pregnant adult populations (29.4 mcg*hr/mL), the physician was offered the option of discussing the results and possible dose modifications with a study team pharmacologist.

Clinical and laboratory monitoring

HIV-related laboratory testing was performed at each study visit if not available as part of recent routine clinical care. Plasma viral load assays were done locally and had lower limits of detection ranging from less than 20 copies/mL to less than 400 copies/mL. Maternal clinical data used in this analysis were: maternal age, ethnicity, weight, concomitant medications, CD4 and plasma viral load assay results. Maternal clinical and laboratory toxicities were assessed through clinical evaluations (history and physical examination) and laboratory assays (ALT, AST, creatinine, BUN, albumin, bilirubin, hemoglobin) on each pharmacokinetic sampling day, at delivery and at a 6 month postpartum visit. Infant data included birth weight, gestational age at birth, and HIV infection status. Infants received physical examinations and serum bilirubin determinations at 24–48 hours and 4–6 days after delivery. The study team reviewed toxicity reports on monthly conference calls, although the subject’s physician was responsible for toxicity management. The Division of AIDS (DAIDS)/NIAID Toxicity Table for Grading Severity of Adult Adverse Experiences (August, 1992) and the DAIDS Toxicity Tables for Grading Severity of Pediatric Adverse Experiences for Children ≤ 3 Months of Age and > 3 Months of Age (April 1994) were used to report adverse events for study subjects.15 All toxicities were followed through resolution.

Sample collection

Subjects were stable on their antiretroviral regimen for at least two weeks prior to pharmacokinetic sampling. Eight plasma samples were drawn at each of the second trimester, third trimester and at the postpartum pharmacokinetic evaluation visits, starting immediately before an oral atazanavir dose and at 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12 and 24 hours post-dose. Atazanavir/ritonavir was given as an observed dose after a light meal. Other information collected included the time of the two prior doses, the two most recent meals and maternal height and weight. A single maternal plasma sample and an umbilical cord sample after the cord was clamped were collected at delivery.

Drug assays

Plasma samples collected from women enrolled in the United States and Brazil were assayed at the Pediatric Clinical Pharmacology Laboratory at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), and samples collected from women enrolled in Thailand were assayed at the PHPT-IRD laboratory at the Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University. Both pharmacology laboratories measured atazanavir and ritonavir concentrations using validated reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) methods and participate in the AIDS Clinical Trial Group (ACTG), USA, Pharmacology Quality Control (Precision Testing) program, which performs standardized inter-laboratory testing twice a year16. At UCSD, the lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) was 0.047 mcg/mL for atazanavir and 0.094 mcg/mL for ritonavir17. The inter assay coefficient of variation (CV) was 8.8% at the lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) for atazanavir and 17% for ritonavir and ranged from 2.7% to 4.6% CV and 5.5% to 9.1% CV respectively for low, middle and high controls. Overall recovery from plasma was 102% for atazanavir and 117.3% for ritonavir. At the PHPT-IRD lab, the lower limit of quantitation was 0.05 mcg/mL for atazanavir and ritonavir. Average accuracy for atazanavir was 102–113% and precision (inter- and intra-assay) was <9% of the CV; and for ritonavir the average accuracy was 99–109% and precision (inter- and intra-assay) was <6% of the CV. Overall extraction recovery from plasma was 102% for atazanavir and 104% for ritonavir.

Pharmacokinetic analyses

The pre-dose concentration (Cpre-dose), maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), corresponding time (Tmax), minimum plasma concentration (Cmin), and 24 hour post-dose concentration (C24h) were determined by direct inspection. For concentrations below the assay limit of detection, a value of one-half of the detection limit (0.024 mcg/mL for atazanavir, 0.047 mcg/mL for ritonavir) was used in summary calculations. Presence of an absorption lag was defined as a 1-hour post-dose concentration lower than the pre-dose concentration. AUC0-24 during the dose interval (from time 0 to 24 hours post-dose) for atazanavir and ritonavir were estimated using the trapezoidal rule. Apparent clearance (CL/F) from plasma was calculated as dose divided by AUC0-24. The terminal slope of the curve (λz) was estimated from the last two measurable and declining concentrations between 8 and 24 hours post-dose. Half-life was calculated as 0.6963 divided by λz, and apparent volume of distribution (Vd/F) was determined by CL/F divided by λz. Both Vd/F and CL/F were also estimated using a one-compartment model with first-order absorption and elimination in the software program Phoenix™ WinNonlim® Version 6.2.1 (Pharsight, Sunnyvale, CA). Pharmacokinetic parameters derived from each approach were compared to assess potential limitations of each methodology.

Statistical analyses

Target enrollment was at least 25 women with evaluable third trimester atazanavir pharmacokinetics in each atazanavir group (with or without tenofovir). Enrollment in the second trimester was optional but enrollment was extended so that at least 12 evaluable second trimester subjects were enrolled in each group. To prevent ongoing enrollment of subjects receiving inadequate dosing, enrollment was to be stopped early if six study subjects had third trimester atazanavir AUC0-24 below the estimated 10th percentile for the non-pregnant historical controls (29.4 mcg*hr/mL). The statistical rationale for this early stopping criterion has been previously described.4

Ninety percent confidence limits of the geometric mean ratio of atazanavir pharmacokinetic parameters in the pregnant versus non-pregnant conditions were calculated. If the confidence limits exclude 1.0, this would indicate that the pharmacokinetic exposure parameter is significantly lower (or higher) in one condition than in the other, with one-sided p-value <0.05 (two-sided p-value < 0.10). Wilcoxon signed-rank test was also used to assess the difference of pharmacokinetic parameters in the 2nd trimester, 3rd trimester and post-partum. Wilcoxon sum-rank test was used to compare the difference between subjects not receiving tenofovir and those receiving tenofovir during the second trimester, third trimester, at delivery, in cord blood and postpartum. Descriptive statistics were calculated for pharmacokinetic parameters of interest during each study period.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics and outcomes

Seventy -two women were enrolled between July 2009 and Jan 2012, of whom 37 did not receive concomitant tenofovir. Pharmacokinetic sampling was completed during the second trimester in 31, during the third trimester in 69, and at two weeks postpartum in 68. The clinical characteristics of the subjects and their pregnancy outcomes are presented in Table 1. Grade three or four toxicities were noted in 25 subjects, including hyperbilirubinemia in 14, and elevated liver enzyme in one. Only the hyperbilirubinemia was considered to be related to atazanavir/ritonavir use. Plasma viral load at delivery was undetectable in 64 (90%) of 71 subjects. Fifty three infants are uninfected; infection status was indeterminate or pending for 19 infants. Bilirubin grade 3 or 4 levels were noted in 3 infants within the first two weeks of life (from 6.4 to 15 mg/dL). Eight neonates had jaundice that required phototherapy for 1 to 2 days, and all of them resolved without sequelae.

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics

| Characteristic | N (%) | Median (range) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 72 | 29.8 (16–44) |

| Gestational age at second trimester study visit (weeks) | 31 | 24.4 (20–27) |

| Gestational age at third trimester study visit (weeks) | 69 | 34 (31– 37) |

| Maternal weight at delivery (kg) | 58 | 73 (50.8– 134.4) |

| Weeks after delivery at postpartum study visit | 68 | 2.57 (1.7–5.7) |

| Maternal weight 2 weeks postpartum (kg) | 68 | 68.5 (41– 169) |

| CD4+ at delivery (cells/µL) | 70 | 567 (54 –1248) |

| Country | ||

| USA | 41(57) | |

| Thailand | 17(23.6) | |

| Brazil | 13 (18) | |

| Argentina | 1(1.4) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Black Non-Hispanic | 19(26.4) | |

| Hispanic | 32 (44.4) | |

| White Non-Hispanic | 3 (4.2) | |

| Asian, Pacific Islander | 17 (23.6) | |

| More than one race | 1 (1.4) | |

| Concomitant medications | ||

| Zidovudine + lamivudine | 20 | |

| Lamivudine + abacavir | 6 | |

| Emtricitabine | 41 | |

| Other* | 5 | |

| Third trimester plasma HIV-1 RNA concentration (copies/mL) | 69 | 48 (<20–12,900) |

| Undetectable (< 400)□ | 61(88.4) | |

| Detectable (≥400) | 8 (11.6) | |

| Delivery plasma HIV-1 RNA concentration (copies/mL) | 71 | 48 (<20– 12,900) |

| Undetectable (<400)□ | 64(90.1) | |

| Detectable (≥400) | 7(9.9) | |

| Postpartum plasma HIV-1 RNA concentration (copies/mL) | 67 | 48 (<20–12,900) |

| Undetectable (<400)§ | 60 (89.5) | |

| Detectable (≥400) | 7(10.5) | |

| Pregnancy outcome | ||

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 72 | 38.4 (32.4–41) |

| Infant birth weight (grams) | 72 | 3,065 (1,470–4,085) |

Other concomitant medications included: stavudine, raltegravir, lopinavir/ritonavir

46 subjects were < 50 copies per milliliter

49 subjects were < 50 copies per milliliter

49 subjects were < 50 copies per milliliter

Atazanavir and ritonavir exposure

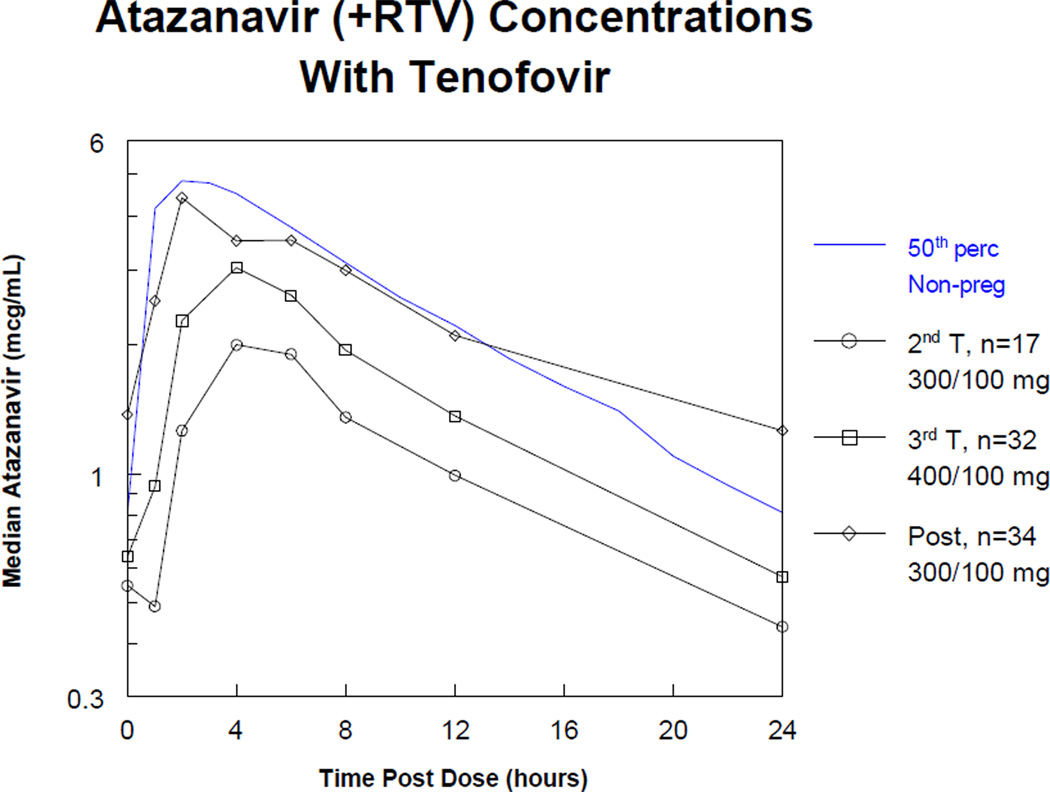

Atazanavir and ritonavir pharmacokinetic parameters during pregnancy and postpartum are presented in Table 2 and Table 3. The percentage of subjects with lags in atazanavir absorption ranged from 6.9% to 52.9%, and were greatest during the second trimester. Atazanavir concentrations increased with the higher atazanavir/ritonavir dose from the second to the third trimester. Despite a reduction back to the standard dose immediately after delivery, atazanavir concentrations were highest at the postpartum visit (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Atazanavir without tenofovir subjects: Median (interquartile range) atazanavir and ritonavir non-compartmental pharmacokinetic parameters

| Second Trimester n=14 |

Third Trimester n=37 |

Postpartum n=34 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atazanavir | AUC0-24 (mcg*hr/mL) | 30.6 (19.9–39.0) | 45.7 (30.8 – 57.3) | 48.8 (34.9 – 67.5) |

| Cpre-dose (mcg/mL) | 0.53 (0.26–0.90) | 0.77 (0.45 – 1.04) | 0.73 (0.12 – 1.24) | |

| Cmax (mcg/mL) | 3.11 (1.95–4.06) | 4.51 (3.28 – 5.84) | 4.52 (2.31 – 5.61) | |

| Tmax (hr) | 4(2–4)* | 4 (2 – 4) | 2 (2 – 4) | |

| C24h (mcg/mL) | 0.49 (0.26–0.78) | 0.71 (0.47 – 1.0) | 0.90 (0.39 – 1.33) | |

| Cmin (mcg/mL) | 0.45 (0.25–0.71) | 0.66 (0.41 – 0.96) | 0.50 (0.11 – 1.18) | |

| CL/F (L/hr) | 9.8 (7.7–15.1)* | 8.8 (7.0 – 13.0)† | 6.2 (4.4 – 8.7) | |

| Vd/F (L) | 171.6 (112.3–244.2) | 182.5 (107.2 – 235.2) | 121.4 (89.4 – 168.4) | |

| t½ (hr) | 10.5 (8.9–12.4) | 12.1 (9.9 – 15.0)† | 14.2 (10.2 – 17.9) | |

| Absorption lag, n (%) | 4 (28.6%) | 7 (18.9%) | 3 (8.8%) | |

| AUC0-24 below the target, n (%) | 6 (42.8%) | 8 (21.6 %) | 7 (20.5 %) | |

| Ritonavir | AUC0-24 (mcg*hr/mL) | 4.6 (3.3–7.8)* | 6.13 (4.8 – 7.6)† | 13.5 (9.9 – 16.2) |

| Cpre-dose (mcg/mL) | 0.05 (0.05–0.05) | 0.05 (0.04 – 0.05) | 0.07 (0.05 – 0.13) | |

| Cmax (mcg/mL) | 0.62 (0.4–1.1)* | 0.76 (0.51 – 0.99)† | 1.62 (0.94 – 2.09) | |

| Tmax (hr) | 4 (2–5.5) | 4 (2 – 4) | 2 (2 – 4) | |

| C24h (mcg/mL) | 0.05 (0.05–0.12) | 0.05 (0.04 – 0.06)† | 0.07 (0.05 – 0.12) | |

| ○ Cmin (mcg/mL) | 0.05 (0.05–0.05) | 0.05 (0.04– 0.05)† | 0.05 (0.05– 0.09) | |

| CL/F (L/hr) | 22 (13–30.4)* | 16.3 (13.2 – 20.8)† | 7.4 (6.2 – 10.2) | |

| Vd/F (L) | 126.1 (74.3–263.2) | 109.3(78.4 – 208.9) | 57.3 (41.89 – 100) | |

| t½ (hr) | 4.5 (3.2–8.0) | 4.8 (3.7 – 6.9) | 5.8 (4.7 – 7.6) |

P < 0.05, second trimester compared with postpartum.

< 0.05, third trimester compared with postpartum.

AUC0-24 = area under the plasma concentration-time curve;

Cpre-dose = pre-dose concentration;

Cmax = maximum concentration;

Tmax = time post-dose of maximum concentration;

C24h = 24-hour post-dose concentration;

Cmin = minimum concentration;

Tmin = time post-dose of minimum concentration;

CL/F = oral clearance;

Vd/F = apparent volume of distribution;

t½ = half-life

Table 3.

Atazanavir with tenofovir subjects: Median (interquartile range) atazanavir and ritonavir non-compartmental pharmacokinetic parameters

| Second Trimester n=17 |

Third Trimester n= 32 |

Postpartum n=34 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atazanavir | AUC0-24 (mcg*hr/mL) | 26.2 (19.9 – 38.4)* | 37.7 (25.7 – 44.4)† | 58.7 (41.4 – 80.5) |

| Cpre-dose (mcg/mL) | 0.55 (0.28 – 0.72) | 0.64 (0.43 – 0.92) | 1.37 (0.59 – 2.22) | |

| Cmax (mcg/mL) | 2.73 (1.65 – 4.02)* | 3.56 (2.28 – 4.32)† | 5.43 (3.81 – 6.80) | |

| Tmax (hr) | 4 (2 – 6)* | 4 (3.5 – 4.0)† | 2 (2 – 4) | |

| C24h (mcg/mL) | 0.44 (0.28 – 0.59)* | 0.57 (0.39 – 0.81)† | 1.26 (0.69 – 1.95) | |

| Cmin (mcg/mL) | 0.33 (0.22 – 0.58)* | 0.46 (0.31 – 0.71)† | 1.05 (0.48 – 1.61) | |

| CL/F (L/hr) | 11.5 (7.8 – 15.1)* | 10.6 (8.9 – 14.4)† | 5.1 (3.7 – 7.3) | |

| Vd/F (L) | 178.8 (96.4 – 229.4) | 178.5 (125.8 – 245.4) | 115.4 (87.1 – 173.8) | |

| t½ (hr) | 9.5 (8.6 – 11.5) | 9.8 (8.4 – 17.6) | 14.7 (10.4 – 22) | |

| Absorption lag, n(%) | 9 (52.9%) | 7 (21.9%) | 2 (6.9%) | |

| AUC0-24 below the target, n (%) | 10 (58.8 %) | 9 (28.1 %) | 2 (6.8 %) | |

| Ritonavir | AUC0-24 (mcg*hr/mL) | 5.6 (4.6 – 7.8)* | 5.6 (4.0 – 7.2) | 12.3 (8.8 – 16.3) |

| Cpre-dose (mcg/mL) | 0.05 (0.05 – 0.08)* | 0.05 (0.05 – 0.09) | 0.1 (0.05 – 0.2) | |

| Cmax (mcg/mL) | 0.66 (0.53 – 0.93)* | 0.60 (0.40 – 0.84) | 1.36 (1.01 – 2.08) | |

| Tmax (hr) | 4 (2 – 6)* | 4 (2 – 6) | 4 (2 – 4) | |

| C24h (mcg/mL) | 0.05 (0.05 – 0.09)* | 0.05 (0.05 – 0.05) | 0.11 (0.05 – 0.17) | |

| Cmin (mcg/mL) | 0.05 (0.5 – 0.06)* | 0.05 (0.05 – 0.05) | 0.05 (0.05 – 0.13) | |

| CL/F (L/hr) | 17.7 (12.8 – 21.8)* | 16.9 (13.9 – 24.7) | 8.2 (6.1 – 11.4) | |

| Vd/F (L) | 134.3 (71.9 – 168.6) | 167.2 (102.9 – 221.3) | 66.3 (48.1 – 94.6) | |

| t½ (hr) | 5.2 (4.0 – 6.9) | 6.0 (4 – 8.5) | 6.1 (5.2 – 7.9) |

P < 0.05, second trimester compared with postpartum.

P < 0.05, third trimester compared with postpartum.

AUC0-24 = area under the plasma concentration-time curve;

Cpre-dose = pre-dose concentration;

Cmax = maximum concentration;

Tmax = time post-dose of maximum concentration;

C24h = 24-hour post-dose concentration;

Cmin = minimum concentration;

Tmin = time post-dose of minimum concentration;

CL/F = oral clearance;

Vd/F = apparent volume of distribution;

t½ = half-life

FIGURE 1.

Median Atazanavir concentration–time curves for atazanavir without tenofovir subjects (top graph) and atazanavir with tenofovir subjects (lower graph), during second trimester, third trimester and postpartum The solid line represents the expected (50th percentile) concentration–time profile in non-pregnant adults.

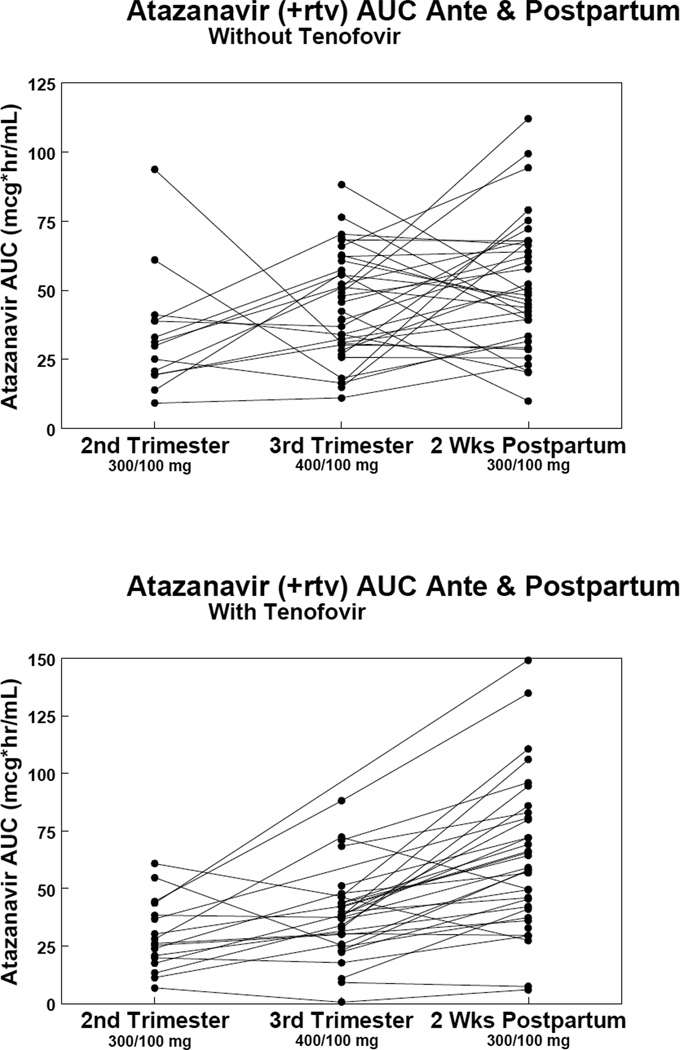

The target atazanavir AUC0-24 during pregnancy was at least 29.4 mcg*hr/mL, the estimated 10th percentile AUC0-24 based on available data when the study started from non-pregnant adults. 14 Third trimester AUC0-24 was below target in 8 (21.6%) of 37 and in 9 (28.1%) of 32 women without and with tenofovir, respectively (Table 2 and 3). Changes in atazanavir AUC0-24 from second to third trimester and postpartum in women with and without tenofovir are presented in Figure 2. In women receiving tenofovir, atazanavir AUC0-24 was not significantly different during the second and third trimester when compared with women not taking tenofovir (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Changes in area under the concentration–time curves (AUC) for atazanavir without tenofovir subjects (top graph) and atazanavir with tenofovir subjects (lower graph) during the second trimester, third trimester, and postpartum.

Atazanavir concentration 24 hours post dose fell below 0.15 mcg/mL, the atazanavir trough concentration target for treatment naive adults in therapeutic drug monitoring programs, in 1 (2.7%) of 37 third trimester subjects who did not receive tenofovir and 1 (3.1%) of 32 third trimester subjects who also received tenofovir.

The one-compartment analysis yielded similar atazanavir pharmacokinetic parameters to the non-compartmental analysis. The one-compartment median (range) second trimester, third trimester and postpartum CL/F values in women not on tenofovir were 9.52 L/hr (<0.01 – 38.5 L/hr), 8.46 L/hr (3.6 – 412 L/hr), and 4.89 L/hr (0.03 – 15.4 L/hr), respectively. The corresponding Vd/F estimated values were 90.7 L (46.7 – 294.1 L), 82.4 L (38.6 – 388.7 L), and 58.7 L (31.6 – 182 L). For women taking tenofovir, the CL/F values for second trimester, third trimester and postpartum were 15.8 L/hr (5.1 – 111 L/hr), 13.5 L/hr (4.8 – 106 L/hr), and 5.1 L/hr(2.1 – 51.1 L/hr), respectively. The corresponding Vd/F estimated values were 123 L (43.9 – 1011 L), 116 L (31.1 – 1484 L), and 72.5 L (30.9 – 887 L).

Maternal plasma and umbilical cord samples were collected at delivery for 64 subjects. Three pairs were below the assay detection limit in both the maternal and umbilical cord samples. The median (range) maternal atazanavir concentrations were 1.67 mcg/mL (0.02 – 1.92 mcg/mL) and 1.06 mcg/mL (0.08 – 3.38 mcg/mL), in those without and with tenofovir, respectively (p=0.052). The median (range) cord blood atazanavir concentrations were 0.20 mcg/mL (0.02 – 5,63 mcg/mL) and 0.16 mcg/mL ( 0.02 – 1.33 mcg/mL) in those without and with tenofovir, respectively (p=0.466). The median (range) cord blood/maternal sample concentration ratio were 0.14 (0.05 – 0.84) and 0.16 (0.03 – 4.08) in those without and with tenofovir, respectively (p=0.409).

DISCUSSION

Three previous studies have described atazanavir pharmacokinetics in pregnant women. Ripamonti et al showed no significant difference in atazanavir AUC and Cmin in 17 pregnant women receiving standard dose atazanavir and ritonavir without tenofovir during the third trimester and postpartum.7 However, mean AUC during both pregnancy and postpartum were 30–34% lower than that seen in nonpregnant historical controls.9 Conradie et al studied third trimester women receiving atazanavir/ritonavir without tenofovir where 20 received standard dosing (300/100 once daily) and 21 received an increased dose (400/100 once daily). The mean third trimester AUC for atazanavir/ritonavir 300/100 mg was 43% lower than postpartum and 21% lower than nonpregnant historical controls. Mean third trimester AUC with the increased dose (400/100) was 23% lower than postpartum but similar to that in the nonpregnant historical controls.9

Our previous study of atazanavir /ritonavir analyzed complete pharmacokinetic profiles in 38 women taking atazanavir/ritonavir300mg/100 mg once daily during pregnancy and postpartum, of whom 20 were also receiving tenofovir. Median atazanavir AUC0-24 and Cmin were reduced by 30–34% during the third trimester compared with postpartum in women not receiving tenofovir. In non-pregnant adults, co-administration of tenofovir with atazanavir reduces atazanavir exposure by approximately 25%.10 We observed a similar effect in pregnancy, so that median atazanavir AUC in pregnant women receiving tenofovir was roughly 50% less than in postpartum women not receiving tenofovir. Trough atazanavir concentrations during the third trimester were below 0.15mcg/mL in 1 (6%) of 18 women third trimester subjects who did not receive tenofovir, and 3 (15%) of 20 third trimester subjects who also received tenofovir.8

This current study reports atazanavir/ritonavir pharmacokinetic profiles with standard doses (atazanavir 300mg/ritonavir 100 mg) once daily in the second trimester and at two weeks postpartum, and an increased dose (atazanavir 400mg/ritonavir 100 mg) once daily during the third trimester. Separate groups of pregnant women who were and were not receiving tenofovir were enrolled. Overall exposure was lowest during the second trimester. With the increased dose in the third trimester, median atazanavir AUC was similar to that seen in nonpregnant historical controls taking the standard dose. Although there were trends to reduced atazanavir exposure with tenofovir use during 2nd and 3rd trimester, the differences were not as great as in our first study and are mostly not significant. This is consistent with an intensive sampling follow up study that showed no effect of tenofovir on atazanavir exposure.18, 19

A striking finding of our study is that atazanavir exposure with the increased dose of 400 mg during the third trimester of pregnancy was still lower than that seen in the same women receiving the standard does of 300/100 mg at two weeks postpartum in both groups of women (those receiving and not receiving tenofovir).

In our study the atazavavir levels postpartum were higher than in nonpregnant adults and higher than with 400 mg during third trimester, similar to what was previously described by Conradie et al.9 The higher postpartum atazanavir AUC (but not statistically significant) we obtained in women with tenofovir compared with those without seems to be related to non adherence (five women in the non-tenofovir arm were below detection at the postpartum visit plus another three had atazanavir concentrations 0.068 – 0.076, while the third trimester pre-dose sample in those three women was 10 times higher. So, four women in the tenofovir arm possibly had poor adherence while eight women in the non-tenofovir arm likely did. If we exclude the values from these women, then the postpartum concentrations in both groups are much more similar.

The clinical significance of the decreased atazanavir exposure with standard dosing during pregnancy is uncertain. However, the risk of virologic breakthrough with low protease inhibitor trough concentrations is a concern, especially for treatment-experienced individuals. In our previous study of atazanavir standard dose during pregnancy, 7 (20%) of 35 subjects had detectable viral loads at delivery while in the present study it occurred in only 7 (9.9%) of 71 subjects.8

In the contrast to the previous findings from Conradie et al, we did not observe an excess of patients presenting with grade 3 or 4 bilirubin with the use of the increased atazanavir dose in the third trimester.9 The occurrence of Grade 3 or 4 bilirubin levels in pregnant women receiving the increased dose in the current study was comparable to that seen in pregnant women receiving standard dose atazanavir/ritonavir (300/100 mg) in our previous published study.8

While no dangerous or unusual elevations of infant bilirubin were observed in study infants, the use of phototherapy in 8 (11%) of 72 study infants appears elevated compared to its use in 2.3% of a large population of California infants at least 37 weeks gestation.20 While this apparent increase in the use of phototherapy could be related to inhibition of bilirubin metabolism from in utero atazanavir exposure, as has been suggested in previous studies9, 21, it could also be explained by the inclusion of infants with gestational ages as low as 32 weeks in our study population. In addition, the decision to initiate phototherapy was made by each subject’s clinical care provider according to local practice and data have shown considerable variability in the criteria for initiating phototherapy.20

Until more is known about the relationship between atazanavir plasma concentrations and virologic response, a reasonable goal of atazanavir therapy during pregnancy is to achieve unbound plasma concentrations in pregnant women equivalent to those seen in non-pregnant adults. While unbound concentrations increase in pregnancy, total atazanavir and ritonavir exposure during pregnancy are reduced by 30–34 %, likely due to a combination of increased clearance and decreased absorption. These physiologic factors may be addressed by increasing the administered dose of atazanavir/ritonavir.

Since this study was performed in varied populations, including U.S, Thai, Brazilian and Argentine women, extrapolation to other populations may be possible. Differences in CYP3A5 activity that are racial and may cause higher atazanavir exposure has been described in Thai individuals.22 Our study population of 44% Hispanic, 26% black, 24% Asian and 4% white, was well balanced to avoid a genetic effect at the pharmacokinetic data.

A limitation is that the pharmacokinetic evaluations within the two weeks postpartum may not reflect atazanavir /ritonavir pharmacokinetics in non-pregnant/non-postpartum women. Likewise, the changes in atazanavir /ritonavir pharmacokinetics during pregnancy are probably a continuous and dynamic process that cannot be fully characterized by only two evaluation time points during pregnancy. Despite these limitations, this study provides important information about atazanavir /ritonavir exposure to guide therapy during pregnancy.

Our current study evaluated complete 24-hour pharmacokinetic profiles with an empiric dose increase during third trimester of pregnancy in all subjects, regardless of prior treatment status. A dose of atazanavir 400 mg/ritonavir 100 mg once daily during the third trimester showed comparable exposure and tolerability to the standard dose (atazanavir 300 mg/ritonavir 100 mg once daily) in non-pregnant adults. These data suggest that a higher atazanavir /ritonavir dose should be used in third trimester pregnant women, and also to be considered during the second trimester, and that postpartum atazanavir/ritonavir dosing can be reduced to standard dosing before two weeks after delivery.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Overall support for the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group (IMPAACT) was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) [U01 AI068632], the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) [AI068632]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. This work was supported by the Statistical and Data Management Center at Harvard School of Public Health, under the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases cooperative agreement #5 U01 AI41110 with the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group (PACTG) and #1 U01 AI068616 with the IMPAACT Group. Support of the sites was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) the NICHD International and Domestic Pediatric and Maternal HIV Clinical Trials Network funded by NICHD (contract number N01-DK-9-001/HHSN267200800001C). We thank the subjects who enrolled in this trial. In addition to the authors, members of the IMPAACT 1026 protocol team include:

Francesca Aweeka, Pharm.D, Emily Barr, CPNP, CNM, MSN, Michael Basar, BA, Kenneth D. Braun, Jr, BA, Jennifer Bryant, Kathleen A. Medvik, BS, MT.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 12th Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV therapy. Miami, FL 2011.

Conflicts of Interest:

No competing financial interests exist.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mirochnick M, Barnett E, Clark DF, McNamara E, Cabral H. Stability of chloroquine in an extemporaneously prepared suspension stored at three temperatures. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:827–828. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199409000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martinez-Rebollar M, Lonca M, Perez I, et al. Pharmacokinetic study of saquinavir 500 mg plus ritonavir (1000/100 mg twice a day) in HIV-positive pregnant women. Ther Drug Monit. 33:772–777. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e318236376d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unadkat JD, Wara DW, Hughes MD, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of indinavir in human immunodeficiency virus-infected pregnant women. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:783–786. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00420-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stek AM, Mirochnick M, Capparelli E, et al. Reduced lopinavir exposure during pregnancy. AIDS. 2006;20:1931–1939. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000247114.43714.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mirochnick M, Best BM, Stek AM, et al. Lopinavir exposure with an increased dose during pregnancy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49:485–491. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318186edd0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Read JS, Best BM, Stek AM, et al. Pharmacokinetics of new 625 mg nelfinavir formulation during pregnancy and postpartum. HIV medicine. 2008;9:875–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00640.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ripamonti D, Cattaneo D, Maggiolo F, et al. Atazanavir plus low-dose ritonavir in pregnancy: pharmacokinetics and placental transfer. AIDS. 2007;21:2409–2415. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32825a69d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mirochnick M, Best BM, Stek AM, et al. Atazanavir pharmacokinetics with and without tenofovir during pregnancy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56:412–419. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31820fd093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conradie F, Zorrilla C, Josipovic D, et al. Safety and exposure of once-daily ritonavir-boosted atazanavir in HIV-infected pregnant women. HIV Med. 2011;12:570–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2011.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taburet AM, Piketty C, Chazallon C, et al. Interactions between atazanavir-ritonavir and tenofovir in heavily pretreated human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:2091–2096. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.6.2091-2096.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eley T, Bertz R, Hardy H, Burger D. Atazanavir pharmacokinetics, efficacy and safety in pregnancy: a systematic review. Antivir Ther. 2012 doi: 10.3851/IMP2473. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barrios A, Rendon AL, Gallego O, et al. Predictors of virological response to atazanavir in protease inhibitor-experienced patients. HIV Clin Trials. 2004;5:201–205. doi: 10.1310/3HL3-HHBD-WKLR-XELL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pellegrin I, Breilh D, Ragnaud JM, et al. Virological responses to atazanavir-ritonavir-based regimens: resistance-substitutions score and pharmacokinetic parameters (Reyaphar study) Antivir Ther. 2006;11:421–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reyataz package insert. Princeton NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Co.; 2012. Mar, [Accessed on August 11, 2012]. Avaliable at http://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_reyataz.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirochnick M, Michaels M, Clarke D, Brena A, Regan AM, Pelton S. Pharmacokinetics of dapsone in children. J Pediatr. 1993;122:806–809. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(06)80033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holland DT, DiFrancesco R, Stone J, Hamzeh F, Connor JD, Morse GD. Quality assurance program for clinical measurement of antiretrovirals: AIDS clinical trials group proficiency testing program for pediatric and adult pharmacology laboratories. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:824–831. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.3.824-831.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Droste JA, Verweij-Van Wissen CP, Burger DM. Simultaneous determination of the HIV drugs indinavir, amprenavir, saquinavir, ritonavir, lopinavir, nelfinavir, the nelfinavir hydroxymetabolite M8, and nevirapine in human plasma by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. Ther Drug Monit. 2003;25:393–399. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200306000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Hentig N, Dauer B, Haberl A, et al. Tenofovir comedication does not impair the steady-state pharmacokinetics of ritonavir-boosted atazanavir in HIV-1-infected adults. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:935–940. doi: 10.1007/s00228-007-0344-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foissac F, Blanche S, Dollfus C, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of atazanavir/ritonavir in HIV-1-infected children and adolescents. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 72:940–947. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atkinson LR, Escobar GJ, Takayama JI, Newman TB. Phototherapy use in jaundiced newborns in a large managed care organization: do clinicians adhere to the guideline? Pediatrics. 2003;111:e555–e561. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.5.e555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mandelbrot L, Mazy F, Floch-Tudal C, et al. Atazanavir in pregnancy: impact on neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;157:18–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avihingsanon A, van der Lugt J, Kerr SJ, et al. A low dose of ritonavir-boosted atazanavir provides adequate pharmacokinetic parameters in HIV-1-infected Thai adults. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;85:402–408. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]