Abstract

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) often expresses mutant KRAS together with tumor-associated mutations of the CDKN2A locus, which are associated with aggressive, therapy-resistant tumors. Here, we unravel specific requirements for the maintenance of NSCLC that carry this genotype. We establish that the ERK/RHOA/focal adhesion kinase (FAK) network is deregulated in high-grade lung tumors. Suppression of RHOA or FAK induces cell death selectively in mutant KRAS;INK4a/ARF deficient lung cancer cells. Furthermore, pharmacological inhibition of FAK caused tumor regression specifically in the high-grade lung cancer that developed in mutant Kras;Cdkn2a-null mice. Our findings provide the rationale for the rapid implementation of genotype-specific targeted therapies utilizing FAK inhibitors in cancer patients.

Keywords: KRAS, INK4a/ARF deficiency, lung cancer, genotype-specific vulnerabilities, FAK inhibitors, targeted cancer therapy

INTRODUCTION

Activating mutations of the proto-oncogene KRAS (mutant KRAS) promote tumorigenesis in several common human cancers such as non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (1). Mutant KRAS exerts its oncogenic activity through the regulation of several signaling networks. Among these, the most extensively characterized are the RAF/MEK/ERK and the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathways (1, 2).

In NSCLC, KRAS mutations occur frequently in combination with inactivating mutations or epigenetic silencing of the CDKN2A locus, which encodes two distinct but overlapping tumor suppressors: p19/ARF (p14 in humans, ARF hereafter) and p16/INK4a (INK4a hereafter). Both p19/ARF and p16/INK4a restrain inappropriate cellular proliferation induced by mutant KRAS by positively regulating p53 and retinoblastoma (Rb) tumor suppressors, respectively (3). Indeed, mutant KRAS in association with CDKN2A deficiency results in high-grade lung and pancreatic cancer in mouse models and has been associated with development of aggressive NSCLC in humans (4–7).

The genotype of cancer cells not only determines their phenotype, but also defines specific vulnerabilities that can be exploited in cancer therapy. Certain cancers are critically dependent on a single oncogenic activity, a phenomenon defined as oncogene addiction (8). For instance, continuous expression of mutant KRAS is required for the survival of NSCLC in both mouse cancer models and in human-derived cells (5, 9). However, attempts to develop direct inhibitors of mutant KRAS have been unsuccessful (10). Therefore, mutant KRAS is still a high-priority therapeutic target.

There has been a tremendous interest in identifying molecular targets that are required for the maintenance of mutant KRAS dependent cancers (11–13). Pharmacological inhibitors of MEK1/2, PI3K and/or mTORC1/2 lead to promising anti-tumor effects in preclinical lung cancer models (14, 15). In addition, several compounds targeting RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathways are currently under clinical investigation and hold promise for the treatment of RAS mutant tumors (16). On the other hand, it is still unknown whether PI3K and MEK1/2 inhibitors are effective therapies in lung cancer. Thus, it is of interest to develop alternative therapeutic strategies that target mutant KRAS tumors.

The goal of this work was the identification of vulnerabilities of mutant KRAS that can be harnessed for cancer therapy. For this purpose, we dissected the signaling pathways downstream of mutant KRAS in NSCLC developed in a genetically defined mouse model and in cellular systems. With this analysis we determined that the RHOA-FAK signaling axis is a critical vulnerability for high-grade lung tumors.

RESULTS

Deficiency of Cdkn2a leads to aberrant activation of RhoA in KrasG12D-induced NSCLC in vivo

To identify cellular networks required for the maintenance of high-grade lung cancer, we crossed tetracycline operator-regulated KrasG12D (tetO-KrasG12D) mice with Clara cell secretory protein-reverse tetracycline transactivator (CCSP-rtTA) mice (5) in a Cdkn2a null background (Ink4a/Arf −/−) (17). These mice express KrasG12D in the respiratory epithelium when exposed to doxycycline.

In agreement with previous findings (5), the induction of KrasG12D combined with Ink4a/Arf deficiency results in increased tumor burden as demonstrated by histological examination and tumor volume quantification of the lungs among KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf+/+, KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf +/− and KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/− mice (Supplementary Fig. S1A and S1B).

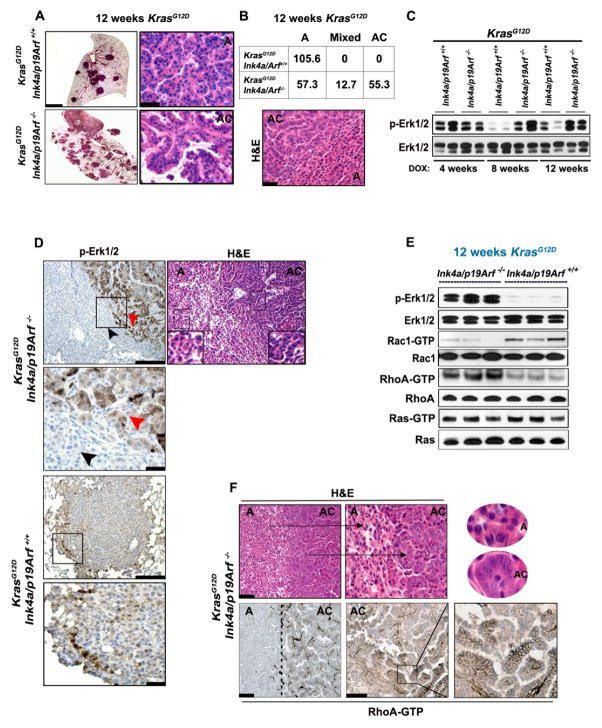

After 12 weeks of doxycycline exposure, about 50% of the lungs of K-rasG12D;Ink4a/Arf−/− mice were occupied by adenocarcinomas (high-grade tumors) consisting of cancer cells with atypical nuclei and cytoplasmic blebbing arranged in papillary structures. We did not detect any adenocarcinomas in the KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf+/+ lungs, which contained only well-differentiated adenomas with some areas occupied by cells with atypical nuclei (Fig. 1A and 1B). Furthermore, the KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf−/− tumors exhibited increased cell proliferation as demonstrated by the percentage of Ki-67 positive cells (Supplementary Fig. S1C and S1D) as well as up-regulation of Cyclin D1, a regulator of G1 to S phase transition (Supplementary Fig. S1E). Accordingly, mice lacking Ink4a/Arf display a remarkable reduction in median survival compared to KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf +/+ and KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf +/− mice (Supplementary Fig. S1F).

Figure 1. Deficiency of Cdkn2a leads to aberrant activation of RhoA in vivo.

(A) H&E staining of lung tissue sections from the indicated genotype after 12 weeks of KrasG12D induction. Left panels: low magnification, scale bars: 1 mm, right panels: high magnification scale bar: 40 μm. (B) Upper panel: Tumor number and grade/mouse in KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/− and KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf +/+ lungs after 12 weeks of KrasG12D induction; The average of 3 representative lung tissue sections/mouse were analyzed (n=8/genotype). A: lung adenoma; AC: lung adenocarcinoma. Lower panel: Representative H&E image of a mixed KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/− tumor (exhibiting both low-and high-grade features). Scale bar: 40 μm. (C) Immunoblot of micro-dissected lung adenomas of KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf +/+ mice and adenocarcinomas of KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/−mice obtained after 4, 8 or 12 weeks of KrasG12D induction. Each lane represents a lysate from a single mouse. (D) p-Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) IHC staining of representative lung tumors of the indicated genotype after 12 weeks of exposure to doxycycline. An adjacent H&E stained section is shown to illustrate areas of adenocarcinomas (AC) and adenomas (A). Inserts indicate area selected for higher magnification shown below. Upper panels scale bar: 100 μm. Lower panels scale bar: 40 μm. Red and black arrowheads indicate adenocarcinomas and adenomas respectively. (E) Representative immunoblots showing Ras-GTP levels along with p-Erk-Rac1-RhoA activation levels. From top to bottom: p-Erk1/2 followed by GST-PAK1, GST-RBD and GST-RAF1 pulldown for Rac1-GTP, RhoA-GTP and Ras-GTP respectively, from micro-dissected lung tumors of the indicated genotypes. Each lane represents a lysate from a single mouse. (F) Upper panels: H&E staining of a lung tumor section to show areas of adenomas (A) and adenocarcinomas (AC) from KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/− mice. Ovals show higher magnification images of sections stained with H&E. Lower panels: RhoA-GTP IHC staining of lung (12 weeks KrasG12D) tumors. Dotted lines demarcate: A (adenomas) and AC (adenocarcinomas). Left panels: lower magnification; Scale bars: 100 μm, right panels: higher magnifications; Scale bars 40 μm. Inserts and arrows indicate areas magnified further on the right panels.

To gain insights into the cellular networks that regulate high-grade lung cancer, we assessed the activation status of the main KrasG12D-regulated signaling pathways in micro-dissected tumors. We determined that Erk1/2 phosphorylation (pErk1/2Thr202/Tyr204) declined in KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf+/+ lung tumors after 8 and 12 weeks of KrasG12D induction, while it remained sustained in KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/− lung adenocarcinomas (Fig. 1C). Moreover, immunohistochemistry (IHC) revealed that Erk1/2Thr202/Tyr204 staining was intense throughout the adenocarcinomas of KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/− mice (Fig. 1D, red arrowhead) compared to adjacent adenomas (Fig. 1D, black arrowhead) and to KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf +/+ tumors (Fig. 1D, lower panels). Interestingly, other investigators reported that p-Erk1/2 is deregulated in high-grade lung tumors induced by KrasG12D also in p53-null mice (18, 19). However, the functional significance of this event is still unknown.

The RHO family of small GTPases (which comprises RAC, CDC42 and RHO) has been implicated in mutant KRAS induced tumorigenesis. These proteins regulate the cytoskeleton, cell migration, proliferation and survival (20). RAC1 is required for mutant KRAS induced transformation in fibroblasts in vitro and for initiating tumorigenesis in a mouse model of lung cancer (21, 22). In addition, Erk1/2 and RhoA regulate common pathways such as cell migration and chemotaxis (23). Indeed, RHOA is also required for mutant K-RAS induced transformation in vitro (24). Finally, deregulation of RHOA occurs in a variety of cancer types (25, 26). Therefore, we interrogated the functional status of Rac1 and RhoA during induction of KrasG12D.

With GST pulldown experiments, we found that the active form of Rac1 (Rac1-GTP) declined over time in KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/− lung adenocarcinomas compared to KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf +/+ tumors (Fig. 1E and Supplementary Fig. S2A). In contrast, as in the case of p-Erk1/2, the active form of RhoA (RhoA-GTP) was elevated in KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/− adenocarcinomas compared to KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf +/+ adenomas at 12 weeks after KrasG12D induction (Fig. 1E and Supplementary Fig. S2B). We did not detect differences in Ras activity (Ras-GTP) between KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf +/+ adenomas and KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/− adenocarcinomas (Fig. 1E). This finding suggests that changes in total amount of Ras-GTP are not responsible for p-Erk1/2 deregulation.

In concordance to the GST pulldown experiments, IHC stainings confirmed that RhoA-GTP is present solely in high-grade lung tumors of KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/− mice (Fig. 1F and Supplementary Fig. S2C–S2E). Furthermore, we noted no differences in Rac1-GTP or RhoA-GTP in the respiratory epithelium of Ink4a/Arf +/+ or Ink4a/Arf −/− mice in the absence of KrasG12D (Supplementary Fig. S2F).

Our observation that Rac1 and RhoA activation are mutually exclusive in vivo confirms long-standing observations obtained in tissue culture systems (27, 28) and suggests that antagonistic regulation of Rac1-RhoA signaling is of biological significance. Consistent with these results, p27/Kip1, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, whose degradation is promoted by RhoA-GTP (29, 30) is undetectable in high-grade KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/− tumors (Supplementary Fig. S2G).

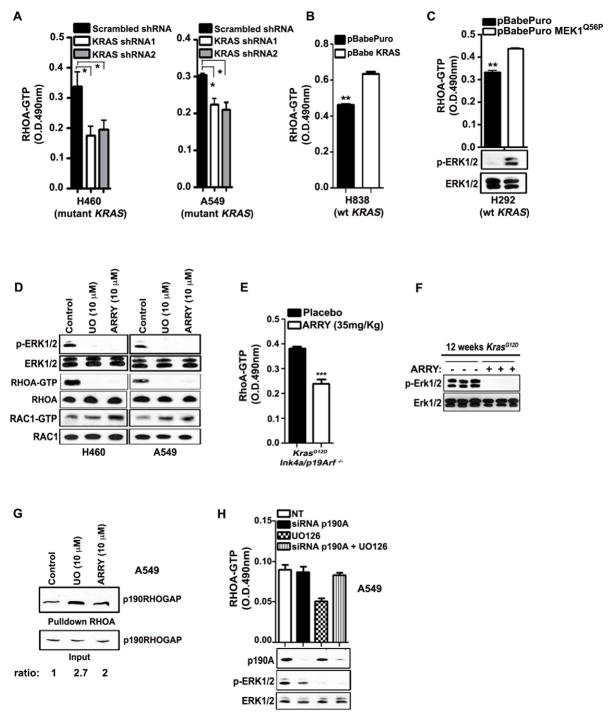

MEK1/2-ERK1/2 drive RHOA activation in INK4a/ARF deficient lung cancer in vitro and in vivo

Our findings suggest that Erk1/2 is a positive regulator of RhoA in KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf−/− -induced adenocarcinomas. To test this hypothesis, we performed gain and loss of function experiments. Quantitative G-LISA assays revealed that ablation of KRAS results in down-regulation of RHOA-GTP in H460 and A549 human NSCLC cells (mutant KRAS, INK4a/ARF deficient) (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. S3A), while its ectopic expression in H838 NSCLC cells (wild type KRAS, INK4a/ARF deficient) leads to the up-regulation of RHOA-GTP (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Fig. S3B). Moreover, ectopic expression of constitutively active MEK1 (MEK1Q56P), which is the main regulator of ERK1/2, in H292 NSCLC cells (wild type KRAS, INK4a/ARF deficient) up-regulates RHOA-GTP (Fig. 2C). Conversely, pharmacological inhibition of MEK1/2 with UO126 and ARRY-142886, lead to down-regulation of RHOA-GTP and consequent up-regulation of RAC1-GTP in H460 and A549 NSCLC cells (Fig. 2D and Supplementary Fig. S3C). In agreement with these findings, treatment of KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/− mice with ARRY-142886 resulted in down-regulation of RhoA-GTP also in mouse lung tumors (Fig. 2E and 2F).

Figure 2. MEK1/2-ERK1/2-p190RHOGAP and INK4a/ARF deficiency drive RHOA activation in NSCLC.

(A, B) G-LISA assay showing RHOA-GTP levels in H460, A549 and H838 NSCLC cells transduced as indicated. O.D.: optical density. Mean and s.e.m. *P<0.05, **P<0.004; n=3. Wt: wild type. (C) G-LISA assay showing RHOA-GTP levels (upper panel) and immunoblot (lower panel) in H292 cells transduced with the indicated retroviral vectors. Mean and s.e.m. **P<0.003; n=3. (D) Immunoblot of H460 and A549 NSCLC cells treated with the indicated MEK1/2 inhibitors for 24h. UO: UO126, ARRY: ARRY-142886. RHOA-GTP and RAC1-GTP were determined by GST-RBD and GST-PAK1 pulldown respectively. (E) G-LISA assay showing RhoA-GTP levels of lung tumor lysates from KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/− mice (after 12 weeks of KrasG12D induction) treated with ARRY-142886. The inhibitor was given for 3 times (every 12 hours) and the mice were sacrificed 2 hours after the last treatment. Mean and s.e.m. ***P<0.001; n=3. (F) Immunoblot showing p-Erk1/2 inhibition upon treatment with ARRY-142886. Each lane represents a lysate from a single mouse. (G) GST-RBD pulldown for RHOA-GTP from panel (D), followed by immunoblot for p190RHOGAP in A549 cells treated as indicated. The ratio value between p190RHOGAP from pulldown and input is indicated. (H) G-LISA assay showing RHOA-GTP levels (upper panel) and immunoblot (lower panel) in A459 cells after siRNA for p190A and/or 10 μM UO126 treatment. P190A: p190RHOGAP.

Next, we determined the mechanisms underlying p-ERK1/2-dependent up-regulation of RHOA-GTP. It has been reported that p-ERK1/2 inhibits p190RHO GTPase-activating protein (p190RHOGAP), a specific GAP for RHOA, in fibronectin-stimulated cells in vitro (31). We determined whether this mechanism is functionally relevant in NSCLC induced by mutant KRAS. With pulldown assays we detected an increased association of endogenous RHOA-GTP with p190RHOGAP after inhibition of MEK1/2 (Fig. 2G). Remarkably, knockdown of p190RHOGAP completely abolished the effect of MEK1/2 inhibition on RHOA (Fig. 2H). These findings indicate that p-ERK1/2 blocks the ability of p190RHOGAP to interact with RHOA and strongly supports the conclusion that p-ERK1/2 is the major activator of RHOA in this context.

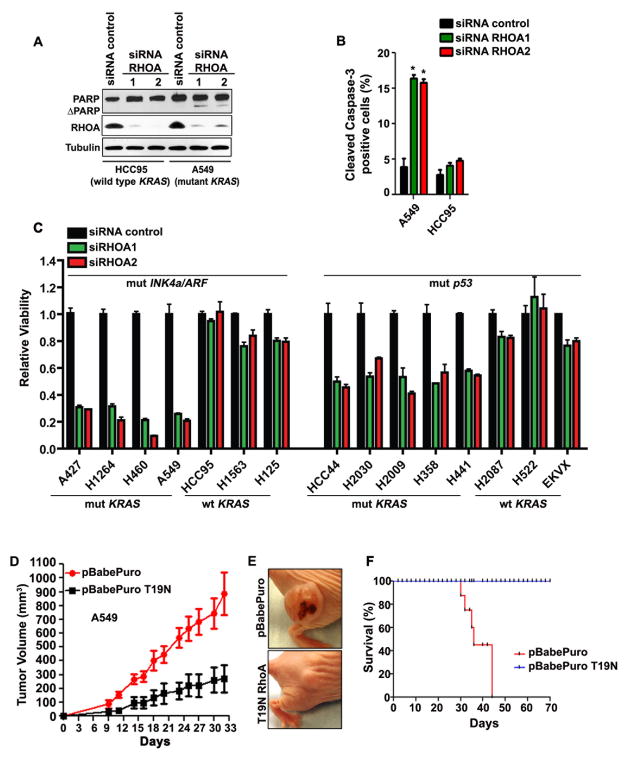

RHOA is a vulnerability of lung cancer cells expressing mutant KRAS

To assess the functional significance of sustained RHOA-GTP in lung adenocarcinomas, we determined the effect of RHOA silencing in cell lines derived from human NSCLC specimens. Remarkably, RHOA silencing with two unrelated siRNAs resulted in apoptosis as shown by increased levels of cleaved poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) and cleaved caspase-3 in A549 cells (mutant KRAS, INK4a/ARF deficient). This effect was virtually absent in HCC95 cells (wild type KRAS, INK4a/ARF deficient) suggesting that the apoptotic effect seen upon RNAi-mediated RHOA ablation reflects a specific requirement for mutant KRAS (Fig. 3A and 3B). To confirm this result, we silenced RHOA in a panel of lung cancer cell lines expressing either mutant or wild type KRAS in addition to INK4a/ARF deficiency. Indeed, we found that the presence of mutant KRAS in association with INK4a/ARF deficiency confers vulnerability to RHOA silencing (72 hours after transfection) (Fig. 3C and Supplementary Fig. S4A). RHOA silencing also results in loss of cell viability in NSCLC cells expressing mutant KRAS in association with mutations of p53, although the effect is less pronounced compared to mutant KRAS, INK4a/ARF deficient NSCLC cells (Fig. 3C and Supplementary Fig. S4A). Importantly, RHOA silencing produced similar results 120 hours after transfection (Supplementary Fig. S4B), suggesting that these effects are not due to differences in doubling time between cell lines. Taken all together, these results indicate that mutant KRAS in combination with INK4a/ARF deficiency trigger a requirement for RHOA-GTP on tumor cell viability.

Figure 3. RHOA is essential for the survival of human NSCLC.

(A) Immunoblot showing total (PARP) and cleaved PARP (ΔPARP) in HCC95 and A549 NSCLC cells 96h after transfection with the indicated siRNAs. (B) Percentage of cleaved caspase-3 positive cells after transfection with the indicated siRNAs. A total of 200 cells were scored/slide for at least 3 replicates. Mean and s.e.m. *P<0.01. (C) Histogram showing viability of the indicated NSCLC cells 72h after transfection with RHOA or control siRNAs. The mutation status of the cell lines is indicated. Mut: mutant. Wt: wild type. (D) Tumor volume of A549 cells transduced as indicated and implanted in nude mice. Mean and s.e.m., n=5. (E) Representative pictures of nude mice from panel (D), 30 days after initiation of the experiment. (F) Kaplan-Meier curve of A549 xenografts (shown in panel D) transduced as indicated; n=5.

Next, we employed human bronchial epithelial cells (HBEC3KT cells-immortalized by introducing hTERT and CDK4, which partially overcome the inhibitory effect of INK4a on cell cycle progression) to test the impact of mutant KRAS expression in this context. The constitutive expression of mutant KRAS results in increased RHOA-GTP that becomes significantly higher upon additional p53 knockdown (Supplementary Fig. S4C and S4D). In both cases, the expression of mutant KRAS results in a considerable induction of cell death upon RHOA silencing (Supplementary Fig. S4E). Thus, HBEC3KT cells confirm our in vivo observations with transgenic mice and suggest that their susceptibility is specifically dependent on a genotype-induced activation of the ERK1/2-RHOA pathway.

To examine whether RHOA is required for the establishment of NSCLC, we conducted xenograft experiments using A549 cells, which are representative of the NSCLC cells we used in vitro. We transduced the A549 cells with a retrovirus expressing RHOA-T19N, a dominant negative mutant of RHOA. Indeed, we found that RHOA-T19N significantly decreases the amount of RHOA-GTP in A549 cells before implantation in mice and in tumors excised at the study endpoint (Supplementary Fig. S4F). We detected a greater than 4-fold decrease in tumor formation of xenografts expressing RHOA-T19N (Fig. 3D and 3E), which correlated with a dramatic difference in survival (Fig. 3F). We conclude that activation of RHOA is critical in promoting the growth of NSCLC.

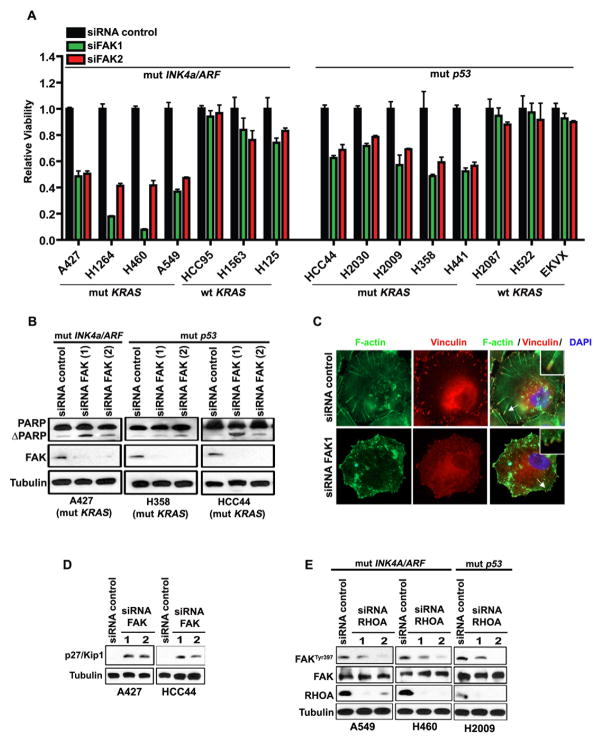

FAK is the primary target of RHOA in mutant KRAS, INK4a/ARF or p53 deficient NSCLC

To date, there are no pharmacological drugs that target RHOA-GTP available for use in pre-clinical trials. Thus, we silenced the main direct and indirect downstream targets of RHOA such as ROCK1, LIMK2, FAK, Villin 1, Cortactin, Kinectin and DIAPH1 (30, 32, 33) to identify ‘druggable’ therapeutic targets. We found that only the silencing of FAK causes significant loss of cell viability that at least in part recapitulates the effects on cell viability of RHOA silencing (Supplementary Fig. S5A and S5B). Indeed, siRNA-mediated FAK knockdown leads to significant apoptosis (72h post-siRNA transfection) in mutant KRAS;INK4a/ARF deficient NSCLC cells (Fig. 4A and 4B). Moreover, FAK silencing triggered apoptosis also in mutant KRAS, p53 deficient cells (Fig. 4A and 4B). Finally, assessment of cell viability at 120h post-transfection with siRNAs against FAK, revealed a more dramatic and selective cell loss (Supplementary Fig. S5C). As predicted by our previous findings regarding RHOA activation (Supplementary Fig. S4C–S4E), ectopic expression of mutant KRAS in HBEC3KT cells increased FAK activation and cell death upon FAK silencing, an effect that was amplified by the knockdown of p53 (Supplementary Fig. S5D and S5E).

Figure 4. FAK is a crucial target of RHOA in mutant KRAS;INK4a/ARF deficient NSCLC.

(A) Histogram showing viability of NSCLC cell lines 72h after transfection with siRNAs against FAK. The mutation status of the cell lines is indicated. (B) Immunoblot showing total (PARP) and cleaved PARP (ΔPARP) in A427, H358 and HCC44 NSCLC cells 72h after transfection with 2 non-overlapping siRNAs against FAK; mut: mutant. (C) siRNA control or siRNA against FAK followed by immunofluorescence staining with phalloidin (green) and vinculin (red) to detect actin stress fibers and focal adhesions respectively, in A549 cells. DAPI was used to visualize nuclei. (D) Immunoblot showing p27/Kip1 up-regulation 72h post-siRNA transfection against FAK in A427 and HCC44 NSCLC cells. (E) Immunoblot of A549, H460 and H2009 NSCLC cells treated as indicated. Mut: mutant.

FAK plays a pivotal role in focal adhesion regulation and turnover in addition to the control of cell adhesion and cancer cell survival (34–37). Moreover, it has been demonstrated that, in some cell types, FAK also contributes to actin remodelling by regulating RHOA (38). Indeed, ablation of FAK in NSCLC cells was accompanied by disruption of focal adhesions, reduced actin stress fiber formation and remarkable up-regulation of the p27/Kip1 tumor suppressor (Fig. 4C and 4D).

Next, we confirmed that FAK is a physiological target of RHOA in NSCLC cells. Silencing of RHOA induces a dramatic down-regulation of p-FAKTyr397 in A549, H460 and H2009 cells (Fig. 4E). Conversely, forced expression of a constitutively active RHOA mutant (RHOA-Q63L) leads to increased p-FAKTyr397 (Supplementary Fig. S5F and S5G).

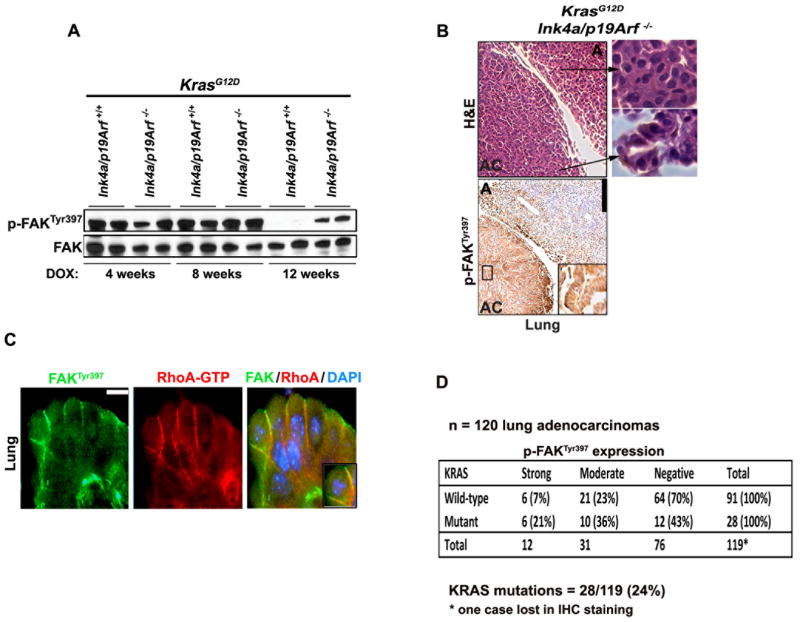

FAK and RHOA are co-activated in primary NSCLC specimens that express mutant KRAS in association with INK4a/ARF or p53 mutations

We predicted that similar to RHOA-GTP, also FAK activation would be sustained in high-grade lung cancer in vivo. Indeed, immunoblot analysis performed on micro-dissected lung tumors showed that p-FAKTyr397 declined to almost undetectable levels after 12 weeks of doxycycline exposure in KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf +/+ lung adenomas, while it remained easily detectable in KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/− adenocarcinomas (Fig. 5A). We found no differences in FAK activationbetween Ink4a/Arf +/+ or Ink4a/Arf−/− mouse lungs in the absence of KrasG12D (Supplementary Fig. S6A).

Figure 5. RHOA-GTP and p-FAKTyr397 are co-activated in high-grade mouse lung tumors.

(A) Immunoblot for p-FAKTyr397 on micro-dissected mouse tumors of the indicated genotype obtained after 4, 8 or 12 weeks of KrasG12D induction. Each lane represents a lysate from a single mouse. (B) Upper panels: H&E staining of a lung tumor section to show areas of adenomas (A) and adenocarcinomas (AC). Lower panels: p-FAKTyr397 IHC staining of representative lung tumors of the indicated genotype. A: adenomas. AC: adenocarcinomas. Inserts and arrows indicate high magnification images. Scale bar: 100 μm. (C) Immunofluorescence for RhoA-GTP and p-FAKTyr397 showing their co-localization in lung tumors. Scale bar: 10 μm. (D) IHC for p-FAKY397 on human specimens was scored as 0 = negative; 1 = moderate less than 50% of tumor cells; 2 = strong, greater than 50% of tumor cells. KRAS (exon 1, codons 12 and 13; and exon 2, codon 61) were studied using DNA extracted from micro-dissected FFPE tumor cells. The data were analyzed by contingency table using Fisher’s exact test in order to determine association between wild type or mutated KRAS for p-FAK activation values; *P<0.014.

IHC staining confirmed that p-FAKTyr397 is present solely in high-grade lung adenocarcinomas of KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/− mice (Fig. 5B and Supplementary Fig. S6B). Finally, RhoA-GTP strongly co-localizes with p-FAKTyr397 in mouse lung adenocarcinomas (Fig. 5C and Supplementary Fig. S6C).

To assess whether our results are relevant to human NSCLC, we used 120 primary human NSCLC specimens and assessed the mutation status of KRAS together with FAK activation. This analysis revealed an association between mutant KRAS and p-FAKTyr397 (Fig. 5D). In addition, we evaluated the activation status of RHOA/FAK and the mutation status of INK4a/ARF and p53 in an independent cohort of 20 consecutive primary human NSCLC specimens expressing mutant KRAS (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. S6D, S6E). We found that tumors carrying either INK4a/ARF, p53 tumor-associated mutations or INK4a/ARF hemizygous deletions evidenced high levels of activated RHOA and FAK (11/20 tumors; Table 1, ID number 1–11), while tumors that do not show strong co-activation of RHOA/FAK, carry wild type INK4a/ARF or p53 (8/20 tumors; Table 1, ID number 13–20). We found only one specimen that did not conform to this pattern (Table 1, ID number 12). Although there’s a significant association between activation of RHOA/FAK and deficiency of the INK4a/ARF or p53 locus, the small sample number does not allow the establishment of firm correlations. The observation that hemizygous deletions of INK4a/ARF occur mainly in specimens that show co-activation of RHOA and FAK suggests that these samples may harbor additional mutations inactivating the INK4a/ARF or p53 tumor suppressive networks. Moreover, it appears that FAK is active regardless of INK4a/ARF or p53 status in a minority of NSCLCs. This observation suggests that in these cases FAK activation may occur through RHOA-independent mechanisms. This could be explained by the fact that several signals, other than RHOA, positively regulate FAK (36).

TABLE 1. RHOA-FAK activation status associations in NSCLC.

Immunohistochemistry, sequencing and copy number results of 20 human NSCLC specimens carrying KRAS mutations.

| ID | FAKTyr397 | RHOA-GTP | K-RAS mutation | INK4a/ARF | P53 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2 | K-RASG13D | Mut | Wt |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | K-RASG12V | Mut | Wt |

| 3 | 2 | 2 | K-RASG12C | Wt | Mut |

| 4 | 2 | 2 | K-RASG12C | Wt | Mut |

| 5 | 2 | 2 | K-RASG12V | Wt | Mut |

| 6 | 2 | 2 | K-RASG12C | Wt | Mut |

| 7 | 2 | 2 | K-RASG12C | Het | Wt |

| 8 | 2 | 2 | K-RASG12C | Het | Wt |

| 9 | 2 | 2 | K-RASG12D | Het | Wt |

| 10 | 2 | 2 | K-RASG12C | Het | Wt |

| 11 | 2 | 2 | K-RASG12C | Het | Wt |

| 12 | 2 | 2 | K-RASG12C | Wt | Wt |

| 13 | 2 | 1 | K-RASG12D | Wt | Wt |

| 14 | 2 | 0 | K-RASG12C | Wt | Wt |

| 15 | 2 | 0 | K-RASG12C | Wt | Wt |

| 16 | 2 | 0 | K-RASG12C | Wt | Wt |

| 17 | 2 | 0 | K-RASG12C | Wt | Wt |

| 18 | 2 | 0 | K-RASG12D | Wt | Wt |

| 19 | 2 | 0 | K-RASG12C | Wt | Wt |

| 20 | 2 | 0 | K-RASG12C | Wt | Wt |

IHC for p-FAKTyr397 and RHOA-GTP was scored as 0 = negative; 1 = moderate less than 50% of tumor cells; 2 = strong, greater than 50% of tumor cells. The data were analyzed by contingency (2×2) table using Fisher’s exact test (two-sided) for categorical variables in order to determine associations between wild type or mutated/deleted INK4a/ARF and p53 for RHOA activation values,

P<0.001. KRAS mutations were identified by Sequenom iPLEX analysis. The exons and intron-exon boundaries of INK4a/ARF and p53 were sequenced from PCR-amplified tumor DNA. In these samples we did not detect INK4a/ARF promoter methylation by EpiTyper analysis.

Wt= wild type; Mut= mutant. See also Supplementary methods.

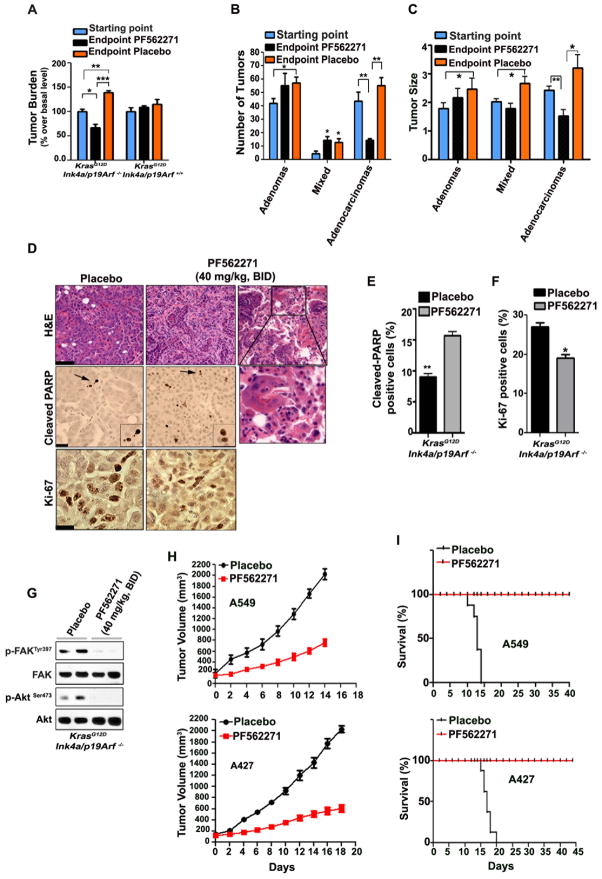

Pharmacological inhibition of FAK leads to lung adenocarcinoma regression in KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/− mice

Our findings suggest that KrasG12D promotes the progression of lung adenomas into adenocarcinomas through a mechanism that involves sustained activation of the Erk1/2-RhoA-FAK signaling axis in Ink4a/Arf deficient cancer cells. Thus, we predicted that inhibition of FAK would lead to significant anti-tumor effects specifically in lung adenocarcinomas and not in adenomas. We evaluated the pre-clinical efficacy of PF562271, an ATP-competitive inhibitor, in KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/− and KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf +/+-induced lung tumors. This inhibitor is well tolerated and displayed antitumor activity in a phase I clinical trial (39). We determined that PF562271 inhibits FAK phosphorylation in vivo in a dose-dependent manner. We selected 40 mg/kg daily as a non-toxic dose that effectively inhibits p-FAKTyr397 (Supplementary Fig. S7A).

Remarkably, treatment with PF562271 resulted in significant tumor regression in KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/− mice while it had anti-proliferative effects in KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf +/+ mice (Fig. 6A). Detailed histological evaluation determined that the treatment with PF562271 significantly suppressed the number and size of KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/− lung adenocarcinomas compared to the placebo-treated mice (Fig. 6B and 6C). Lung adenocarcinomas treated with PF562271 were distinguished by the presence of foamy macrophages and enrichment of reparative connective tissue (Fig. 6D upper panels). In addition, FAK inhibition caused localized induction of apoptosis and reduced cellular proliferation (Fig. 6D lower panels and 6E–6F).

Figure 6. Pre-clinical efficacy of PF562271 inhibitor in advanced NSCLC.

(A) Quantification of lung tumor burden in KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/− and KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf +/+ mice treated with PF562271 inhibitor (presented as a percentage change over basal level). The treatment started after 10 weeks of KrasG12D induction (in order to obtain high-grade tumors) and continued for 12 days. Mean and s.e.m; n=10/group. *P<0.05, **P<0.004, ***P<0.001. (B–C) Tumor number, size and grade of individual lung tumors from KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/− mice treated with PF562271 inhibitor as in panel A; n=10/group. Mean and s.e.m. *P<0.03, **P<0.003. (D) Upper panels: histological evaluation of excised lungs after treatment with placebo (left panel) or PF562271 inhibitor for 12 days (two representative images to show the enrichment in reparative connective tissue-middle panel or macrophages infiltration-right panel, during adenocarcinoma regression). The inset indicates area magnified below. H&E: Hematoxylin/Eosin staining; Scale bar: 40 μm. Lower panels: representative images showing increased localized apoptosis (cleaved PARP) and decreased Ki-67 (proliferation marker) positive cells in the lungs of mice sacrificed 2h after treatment with PF562271 inhibitor; Arrows indicate magnified image shown in the inset. Scale bars: 30 μm. (E) The histogram reports the percentage of cleaved-PARP positive cells of the indicated treatment groups assessed at the study endpoint. A total of 200 cells were scored/slide for at least 3 replicates. Mean ± s.e.m. **P<0.0016. (F) The histogram reports the percentage of Ki-67 positive cells of the indicated treatment groups. Mean ± s.e.m. *P<0.029. A total of 200 cells were scored/slide for at least 3 replicates. (G) Immunoblot showing effective p-FAKTyr397 and p-AktSer473 inhibition with PF562271 inhibitor 2h after treatment. Each lane represents a lung lysate from a single mouse. (H) Tumor volume of A549 and A427 xenografts treated as indicated. The treatment with PF562271 inhibitor (40mg/kg) was started when the tumors reached ~150mm3 and was given every day for a total of 12 days. The mice were sacrificed when the tumors reached 2000 mm3. Mean and s.e.m.; n=8. (I) Kaplan-Meier curves of A549 and A427 xenografts treated as in panel (H); n=8.

FAK is a positive regulator of Akt (33). Indeed, we found that PF562271 not only efficiently inhibits FAKTyr397 in vivo but also results in striking down-regulation of p-AktSer473 (Fig. 6G). The anti-tumor effects observed with PF562271 were confirmed with FAK14 inhibitor (Supplementary Fig. S7B–S7G). FAK14 is structurally unrelated to PF562271 and inhibits the autophosphorylation of FAK at Tyr397 (40).

Finally, we performed studies with A427 and A549 NSCLC cells in order to determine the impact of the PF562271 inhibitor on the survival of athymic nude mice mice carrying xenografts of human cells. Notably, we detected a significant increase in the survival rate of PF562271-treated mice compared to placebo-treated mice (Fig. 6H and 6I). We obtained similar results with the FAK14 inhibitor (Supplementary Fig. S7H–S7I). Thus, we conclude that pharmacological inhibition of FAK is a potent therapeutic strategy for advanced KRAS-induced lung tumors.

DISCUSSION

The identification of patients that may benefit from treatment with targeted cancer therapies is still a significant challenge. In this study, we show that NSCLCs characterized by mutant KRAS and loss of either INK4a/ARF or p53 are highly sensitive to inhibition of the RHOA-FAK signaling axis. The data imply that pharmacological inhibitors of FAK are effective, genotype-specific anticancer agents. Our findings are of clinical significance because these genotypes are associated with aggressive cancers, which are refractory to conventional therapy.

Recently, several groups reported strategies to induce antitumor responses in high-grade mouse lung cancer (11, 13, 41). To the best of our knowledge our study is the first example of an effective genotype-specific mono-therapy for high-grade mutant KRAS tumors.

Consistent with the known roles of FAK in the regulation of the cytoskeleton, we determined that its inhibition results in: the reduction of F-actin stress fibers, disruption of focal adhesions, induction of the p27/Kip1 tumor suppressor and decreased p-AKTSer473. These events occurred in conjunction with induction of apoptosis; therefore, we propose that multiple cooperative functions of FAK contribute to its requirement for the maintenance of high-grade lung cancer. In addition, our studies demonstrate that FAK is the main effector of RHOA. However, it is still possible that other downstream targets of RHOA may contribute to its tumor-promoting ability. Future studies will be necessary to determine the mechanisms of cell death that contribute to this antitumor response.

Pharmacological inhibition of MEK1/2 leads to compensatory upregulation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (42), which in turn promotes cancer cell survival. On the contrary, we have demonstrated that pharmacological inhibition of FAK in vivo down-regulates p-Akt. Thus, inhibition of FAK does not trigger the emergence of PI3K/AKT dependent compensatory mechanisms. Collectively, these data demonstrate that the inhibition of an ultimate effector-arm of mutant KRAS, in this case RHOA/FAK, has detrimental antitumor effects.

It has been reported that p19/ARF and p53 restrain the progression of lung adenomas into adenocarcinomas and that their loss leads to the up-regulation of MEK1/2 signaling through multiple mechanisms including genomic amplification of mutant KRAS, inactivation of negative feedback mechanisms or emergence of co-operative oncogenes (18, 19). We did not detect differences in the overall Ras activity (Ras-GTP) between KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf +/+ adenomas and KrasG12D;Ink4a/Arf −/− adenocarcinomas. Thus, we propose that in this mouse model, mechanisms other than increased Ras-GTP signaling are responsible for the deregulation of p-Erk1/2.

Several questions remain to be answered regarding the role of FAK in lung cancer. As demonstrated by our IHC data, a subset of mutant KRAS NSCLCs displays upregulation of p-FAK in absence of INK4a/ARF or p53 mutations/deletions. Thus, it is of interest to determine the mechanisms of regulation of FAK in this setting. Furthermore, larger cohorts of patients will be needed to firmly establish that a correlation exist between mutant KRAS, INK4a/ARF and/or p53 deficiency and activation of RHOA-FAK in human primary NSCLCs.

In view of the fact that NSCLCs are often comprised of heterogeneous populations of neoplastic cells, a possible mechanism of emergence of resistance to FAK inhibitors could be fuelled by the persistence of neoplastic clones primarily driven by low-level oncogenic signals that are still able to develop high-grade tumors. Although this targeted therapy will have a significant benefit in cancer treatment, the elimination of less-advanced tumors is still an unmet need that must be resolved.

We conclude that the RHOA-FAK signaling axis is a novel, critical synthetic lethal partner of mutant KRAS in NSCLCs that are INK4a/ARF or p53 deficient. We propose that this information would serve as a biomarker for the selection of patients undergoing personalized cancer treatment protocols involving FAK inhibitors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse studies

The PF562271 inhibitor (Pfizer) was reconstituted in 50% DMSO and 50% PEG300 and additionally diluted with saline to a final concentration of 40 mg/kg before administration to the mice twice daily for a total of 12 days by oral gavage. The FAK14 inhibitor (Tocris) was reconstituted in H2O and administered to the mice by intra-peritoneal injection, once daily for a total of 10 days at the dosage of 20 mg/kg for the transgenic mice and 30 mg/kg for athymic nude mice. ARRY-142886 (AZD6244) (Selleck) was reconstituted in 0.5% methyl cellulose (Fluka) and 0.4% polysorbate (Tween 80; Fluka) and administered at 35mg/kg by oral gavage. Xenograft experiments using A549 or A427 NSCLC cells were done by subcutaneous inoculation of 2×106 cells into 6-week-old female athymic nude mice (nu/nu). For all in vivo experiments we used age-matched littermates. The body weight of the mice remained stable during treatment with PF562271 and reduced by <5% during treatment with FAK14. Tumor burden was assessed by digital quantification of the area occupied by tumors compared to unaffected tissue using NIH ImageJ (v1.42q) software. All studies were done according to the guidelines of the University of Texas Southwestern Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. See also Supplementary Methods.

Cell culture and reagents

Human NSCLC cell lines H125, H441, H2087, H522, EKVX, H2030, H1264, HCC95, HCC44, H2009, H358, H460, H1563, A549 and HBEC3KT cells (HBEC3 cells immortalized by introducing Cdk4 and hTERT) together with the variants HBEC3KT-shp53, HBEC3KT-KRAS and HBEC3KT-shp53+KRAS, were kindly provided by Dr. John Minna (UT Southwestern Medical Center) (43–45). All NSCLC cell lines have been tested and authenticated by DNA fingerprinting using the PowerPlex 1.2 kit (Promega) and confirmed to be the same as the DNA fingerprint library maintained by ATCC and the Minna/Gazdar lab (the primary source of the lines). See also Supplementary Methods.

RNA interference

siRNA (siGenome) against RHOA, FAK, p190RHOGAP or non-targeting siRNA control were purchased from Dharmacon (Thermo Scientific). See also Supplementary Methods.

RhoA and Rac1 Activity Assay

Cells were lysed in cold MLB buffer (125 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 750 mM NaCl, 5% NP-40, 50 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EDTA, protease inhibitors cocktail tablet, PMSF). See also Supplementary Methods.

PCR amplification and sequencing

The exonic regions of interest (NCBI Human Genome Build 36.1) were broken into amplicons of 350 bp or less, and specific primers were designed using Primer 3, to cover the exonic regions plus at least 50 bp of intronic sequences on both sides of intron-exon junctions. See also Supplementary Methods.

Mutation detection

Mutations were detected using an automated detection pipeline at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer center Bioinformatics Core. Bi-directional reads and mapping tables (to link read names to sample identifiers, gene names, read direction, and amplicon) were subjected to a QC filter which excludes reads that have an average phred score of < 10 for bases 100–200. See also Supplementary Methods.

Supplementary Material

SIGNIFICANCE.

Targeted therapies are only effective for a small fraction of cancer patients. We report that FAK inhibitors exert potent anti-tumor effects in NSCLC that express mutant KRAS in association with INK4a/ARF deficiency. These results reveal a novel genotype-specific vulnerability of cancer cells that can be exploited for therapeutic purposes.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: NIH K08 CA 112325, R01CA137195, American Cancer Society Institutional Research Grant # 02-196, the Concern Foundation, the Gibson Foundation, Leukemia Texas Inc (PPS). Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas-RP101496 (GK). Department of Defense (MTD). American Heart Association (GR). Department of Defense-W81XWH-07-1-0306 and Specialized Program of Research Excellence in Lung Cancer-P50CA70907 (IIW).

We are grateful to Michael A. White for critically reading the manuscript. We are grateful to John D. Minna, Michael Peyton and Jill Larsen for providing reagents (UT Southwestern Medical Center). We thank Marina Asher (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center) for technical assistance in paraffin staining and Masaya Takahashi (UT Southwestern Medical Center) for advice on MRI imaging.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. RAS oncogenes: the first 30 years. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:459–65. doi: 10.1038/nrc1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manning BD, Cantley LC. AKT/PKB signaling: navigating downstream. Cell. 2007;129:1261–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherr CJ. The INK4a/ARF network in tumour suppression. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:731–7. doi: 10.1038/35096061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ding L, Getz G, Wheeler DA, Mardis ER, McLellan MD, Cibulskis K, et al. Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2008;455:1069–75. doi: 10.1038/nature07423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher GH, Wellen SL, Klimstra D, Lenczowski JM, Tichelaar JW, Lizak MJ, et al. Induction and apoptotic regression of lung adenocarcinomas by regulation of a K-Ras transgene in the presence and absence of tumor suppressor genes. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3249–62. doi: 10.1101/gad.947701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hezel AF, Kimmelman AC, Stanger BZ, Bardeesy N, Depinho RA. Genetics and biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1218–49. doi: 10.1101/gad.1415606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warshaw AL, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Pancreatic carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:455–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202133260706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma SV, Settleman J. Oncogene addiction: setting the stage for molecularly targeted cancer therapy. Genes Dev. 2007;21:3214–31. doi: 10.1101/gad.1609907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh A, Greninger P, Rhodes D, Koopman L, Violette S, Bardeesy N, et al. A gene expression signature associated with “K-Ras addiction” reveals regulators of EMT and tumor cell survival. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:489–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gysin S, Salt M, Young A, McCormick F. Therapeutic strategies for targeting ras proteins. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:359–72. doi: 10.1177/1947601911412376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Raedt T, Walton Z, Yecies JL, Li D, Chen Y, Malone CF, et al. Exploiting cancer cell vulnerabilities to develop a combination therapy for ras-driven tumors. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:400–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar MS, Hancock DC, Molina-Arcas M, Steckel M, East P, Diefenbacher M, et al. The GATA2 transcriptional network is requisite for RAS oncogene-driven non-small cell lung cancer. Cell. 2012;149:642–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xue W, Meylan E, Oliver TG, Feldser DM, Winslow MM, Bronson R, et al. Response and Resistance to NF-kappaB Inhibitors in Mouse Models of Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:236–47. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Konstantinidou G, Bey EA, Rabellino A, Schuster K, Maira MS, Gazdar AF, et al. Dual phosphoinositide 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin blockade is an effective radiosensitizing strategy for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer harboring K-RAS mutations. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7644–52. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engelman JA, Chen L, Tan X, Crosby K, Guimaraes AR, Upadhyay R, et al. Effective use of PI3K and MEK inhibitors to treat mutant Kras G12D and PIK3CA H1047R murine lung cancers. Nat Med. 2008;14:1351–6. doi: 10.1038/nm.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fremin C, Meloche S. From basic research to clinical development of MEK1/2 inhibitors for cancer therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2010;3:8. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-3-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Serrano M, Lee H, Chin L, Cordon-Cardo C, Beach D, DePinho RA. Role of the INK4a locus in tumor suppression and cell mortality. Cell. 1996;85:27–37. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldser DM, Kostova KK, Winslow MM, Taylor SE, Cashman C, Whittaker CA, et al. Stage-specific sensitivity to p53 restoration during lung cancer progression. Nature. 2010;468:572–5. doi: 10.1038/nature09535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Junttila MR, Karnezis AN, Garcia D, Madriles F, Kortlever RM, Rostker F, et al. Selective activation of p53-mediated tumour suppression in high-grade tumours. Nature. 2010;468:567–71. doi: 10.1038/nature09526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heasman SJ, Ridley AJ. Mammalian Rho GTPases: new insights into their functions from in vivo studies. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:690–701. doi: 10.1038/nrm2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kissil JL, Walmsley MJ, Hanlon L, Haigis KM, Bender Kim CF, Sweet-Cordero A, et al. Requirement for Rac1 in a K-ras induced lung cancer in the mouse. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8089–94. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qiu RG, Chen J, Kirn D, McCormick F, Symons M. An essential role for Rac in Ras transformation. Nature. 1995;374:457–9. doi: 10.1038/374457a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brahmbhatt AA, Klemke RL. ERK and RhoA differentially regulate pseudopodia growth and retraction during chemotaxis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13016–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211873200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khosravi-Far R, Solski PA, Clark GJ, Kinch MS, Der CJ. Activation of Rac1, RhoA, and mitogen-activated protein kinases is required for Ras transformation. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6443–53. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamai T, Tsujii T, Arai K, Takagi K, Asami H, Ito Y, et al. Significant association of Rho/ROCK pathway with invasion and metastasis of bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2632–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xue W, Krasnitz A, Lucito R, Sordella R, Vanaelst L, Cordon-Cardo C, et al. DLC1 is a chromosome 8p tumor suppressor whose loss promotes hepatocellular carcinoma. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1439–44. doi: 10.1101/gad.1672608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sander EE, ten Klooster JP, van Delft S, van der Kammen RA, Collard JG. Rac downregulates Rho activity: reciprocal balance between both GTPases determines cellular morphology and migratory behavior. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1009–22. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.5.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wildenberg GA, Dohn MR, Carnahan RH, Davis MA, Lobdell NA, Settleman J, et al. p120-catenin and p190RhoGAP regulate cell-cell adhesion by coordinating antagonism between Rac and Rho. Cell. 2006;127:1027–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu W, Bellone CJ, Baldassare JJ. RhoA stimulates p27(Kip) degradation through its regulation of cyclin E/CDK2 activity. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3396–401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mammoto A, Huang S, Moore K, Oh P, Ingber DE. Role of RhoA, mDia, and ROCK in cell shape-dependent control of the Skp2-p27kip1 pathway and the G1/S transition. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:26323–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402725200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pullikuth AK, Catling AD. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase promotes Rho-dependent focal adhesion formation by suppressing p190A RhoGAP. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:3233–48. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01178-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riento K, Ridley AJ. Rocks: multifunctional kinases in cell behaviour. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:446–56. doi: 10.1038/nrm1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Del Re DP, Miyamoto S, Brown JH. Focal adhesion kinase as a RhoA-activable signaling scaffold mediating Akt activation and cardiomyocyte protection. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:35622–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804036200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McLean GW, Komiyama NH, Serrels B, Asano H, Reynolds L, Conti F, et al. Specific deletion of focal adhesion kinase suppresses tumor formation and blocks malignant progression. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2998–3003. doi: 10.1101/gad.316304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitra SK, Hanson DA, Schlaepfer DD. Focal adhesion kinase: in command and control of cell motility. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrm1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLean GW, Carragher NO, Avizienyte E, Evans J, Brunton VG, Frame MC. The role of focal-adhesion kinase in cancer - a new therapeutic opportunity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:505–15. doi: 10.1038/nrc1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bryant P, Zheng Q, Pumiglia K. Focal adhesion kinase controls cellular levels of p27/Kip1 and p21/Cip1 through Skp2-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:4201–13. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01612-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen BH, Tzen JT, Bresnick AR, Chen HC. Roles of Rho-associated kinase and myosin light chain kinase in morphological and migratory defects of focal adhesion kinase-null cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33857–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Infante JR, Camidge DR, Mileshkin LR, Chen EX, Hicks RJ, Rischin D, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic phase I dose-escalation trial of PF-00562271, an inhibitor of focal adhesion kinase, in advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1527–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.9346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Golubovskaya VM, Nyberg C, Zheng M, Kweh F, Magis A, Ostrov D, et al. A small molecule inhibitor, 1,2,4,5-benzenetetraamine tetrahydrochloride, targeting the y397 site of focal adhesion kinase decreases tumor growth. J Med Chem. 2008;51:7405–16. doi: 10.1021/jm800483v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen Z, Cheng K, Walton Z, Wang Y, Ebi H, Shimamura T, et al. A murine lung cancer co-clinical trial identifies genetic modifiers of therapeutic response. Nature. 2012;483:613–7. doi: 10.1038/nature10937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Turke AB, Song Y, Costa C, Cook R, Arteaga CL, Asara JM, et al. MEK inhibition leads to PI3K/AKT activation by relieving a negative feedback on ERBB receptors. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3228–37. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Phelps RM, Johnson BE, Ihde DC, Gazdar AF, Carbone DP, McClintock PR, et al. NCI-Navy Medical Oncology Branch cell line data base. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 1996;24:32–91. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240630505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramirez RD, Sheridan S, Girard L, Sato M, Kim Y, Pollack J, et al. Immortalization of human bronchial epithelial cells in the absence of viral oncoproteins. Cancer Res. 2004;64:9027–34. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sato M, Vaughan MB, Girard L, Peyton M, Lee W, Shames DS, et al. Multiple oncogenic changes (K-RAS(V12), p53 knockdown, mutant EGFRs, p16 bypass, telomerase) are not sufficient to confer a full malignant phenotype on human bronchial epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2116–28. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.