Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the impact of family planning promotion on incident pregnancy in a combined effort to address Prongs 1 and 2 of Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV.

Design

We conducted a factorial randomized controlled trial of two video-based interventions.

Methods

“Methods-focused” and “Motivational” messages promoted long-term contraceptive use among 1060 couples with HIV in Lusaka, Zambia.

Results

Among couples not using contraception prior to randomization (N=782), the video interventions had no impact on incident pregnancy. Among baseline contraceptive users, viewing the “Methods” video which focused on the IUD and contraceptive implant was associated with a significantly lower pregnancy incidence (HR=0.38; 95%CI:0.19–0.75) relative to those viewing control and/or motivational videos. The effect was strongest in concordant positive couples (HR=0.22; 95%CI:0.08–0.58) and couples with HIV+ women (HR=0.23; 95%CI:0.09–0.55).

Conclusions

The “Methods video” intervention was previously shown to increase uptake of longer-acting contraception and to prompt a shift from daily oral contraceptives to quarterly injectables and long-acting methods such as the IUD and implant. Follow-up confirms sustained intervention impact on pregnancy incidence among baseline contraceptive users, in particular couples with HIV positive women. Further work is needed to identify effective interventions to promote long-acting contraception among couples who have not yet adopted modern methods.

Keywords: Couples’ voluntary HIV counseling and testing, family planning, long-term contraception, randomized controlled trial, Zambia

INTRODUCTION

Total fertility rates (TFR) in Africa are among the world’s highest, and though knowledge of modern contraception is increasing, women in many countries do not have access to these methods 1–3. The United Nations has emphasized family planning as critical for economic recovery and development in Africa, and African countries are adopting family planning in order to advance maternal and child health, improve human rights, and moderate demographic trends. Some successes have been observed: the TFR in Rwanda decreased from 8.5 pre-genocide 4 to 5.0 in 2010 5. Until 2010, Zambia’s fertility was declining, with a TFR of 7.2 in 1980, 6.7 in 1990, and 6.0 in 2000 6. A TFR of 5.2, the lowest observed in Zambia, was recorded from 2003–2009. However, the TFR has increased in recent years to 6.1 in 2010 and 6.0 in 2011 7.

Barriers to family planning in sub-Saharan Africa include reduced contraception availability; lack of knowledge about available contraception methods (especially long-acting reversible methods such as the copper intrauterine device (IUD) and the contraceptive implant; fear of side-effects (especially among HIV positive women); and social, cultural and religious practices discouraging contraception use and encouraging childbearing 8–11. Additionally, many women are not decision makers within the family, and African men often control sexual and familial economic decision-making 12–14.

Long-acting reversible user-independent contraceptive (LARC) methods, including the IUD and the contraceptive implant, are not subject to user error or re-supply like oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) and injectables, making them more effective at preventing pregnancy and more cost-efficient over the long term 15. Barriers to IUD and implant use include client misconceptions about safety, lack of understanding about their mechanism of action, and lack of culturally-sensitive marketing to increase knowledge and allay concerns related to LARC methods 16,17. Few nurses in sub-Saharan Africa have the training to provide these contraception methods to patients 18. This leads to poor knowledge of LARC methods among patients because nurses are not inclined to discuss what they are not comfortable or able to provide 19. This cycle can be overcome by addressing supply-and-demand aspects concurrently by giving providers didactic training to improve knowledge and practical skills to ensure their comfort with insertions and removals, in tandem with medical education for clients 20,21.

In Zambia, policies adopted in 1989 emphasized the goal of reducing population growth by controlling fertility 22 through increasing family planning services, raising the age of marriage, improving the status of women, providing family planning education, and incorporating economic incentives for reduced fertility 23. The Zambian government endorses the complete range of contraceptive options with an emphasis on “method mix” and the capacity to provide all methods 24. Today, user-dependent methods like daily OCPs and progesterone-based injectables like depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA), which must be administered every 13 weeks, are the most common methods in Zambia 25. Overall contraceptive use is 23% among women of reproductive age, and 17% use a modern form of contraception 26. Less than 2% of women use a LARC method.

Despite social marketing efforts for family planning in Zambia and efforts by the Planned Parenthood Association of Zambia to include men in family planning services 27, spousal communication is often poor 28. Findings from a community-based contraceptive distribution program suggest that involving both partners enhances service delivery and that involving men directly is more productive than asking women to discuss and negotiate family planning issues with their spouses 29–31.

In areas of high HIV prevalence and total fertility, it is critical to find family planning interventions that are effective and feasible in reducing unintended pregnancies. We present the results of a randomized controlled trial evaluating whether a video-based family planning intervention with a particular focus on LARC methods (addressing Prong 2 of PMTCT) influenced time to pregnancy among HIV sero-discordant and concordant positive couples obtaining couples’ voluntary HIV counseling and testing (CVCT) services (Prong 1 of PMTCT) in Lusaka, Zambia.

METHODS

Study design

The study design and contraceptive uptake after two video interventions have been previously reported 32, as has the impact of the informed (IC) on knowledge of contraceptive methods and beliefs about efficacy and side effects 33. Briefly, a factorial randomized controlled trial was designed to evaluate two interventions to promote contraceptive use among sero-discordant and concordant positive couples identified from CVCT clinics in Lusaka, Zambia. Consecutively numbered envelopes were prepared in the US and shipped to Zambia, each containing a random assignment to “Methods”, “Motivation”, “Methods + Motivation”, or “Control” videos in a 1:1:1:1 ratio. Couples viewed the designated videos followed by a counselor-facilitated discussion. The “Methods” video presented information about contraceptive methods starting with the LARC methods, specifically IUD and implant, followed by DMPA, OCP, emergency contraception, and permanent methods (tubal ligation and vasectomy). The “Motivational” video modeled future planning behaviors in a dramatized format; the impact of this intervention on will writing, financial planning, and appointing guardians has been previously published 33. A “Control” video contained information on hand washing, bed-net use, and nutrition. Enrollment began in July 2002 and follow-up ended May 2006, prior to widespread availability of antiretrovirals in Lusaka. The study was approved by Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP)-registered Institutional Review Boards at Emory University and in Zambia. Written informed consent (IC) was obtained from all participating couples.

Outcome of interest

The outcome of interest was time to pregnancy, operationalized as clinically confirmed pregnancy or a positive pregnancy test at a follow-up visit (follow-up visits were scheduled every three months, with the possibility of client-initiated interim visits as needed). Participants were censored at death, loss to follow-up/dropout, exit interview, or the defined end-date of the study.

Exposures of interest

The exposure of interest was the arm of trial. Covariates of interest included socio-demographics, sexual behavior and health descriptors, and women’s contraceptive history. Socio-demographic and health and contraceptive history variables, including household income, English language ability, occupation, religion, and fertility intentions were collected at baseline prior to the intervention 34. Time-varying variables, including contraceptive method uptake during follow-up, sero-conversion during follow-up, and method stopping/starting/switching, were collected at 3-month interval visits or at interim visits. The HIV stage variable was derived from laboratory staging (based on hematocrit and sedimentation rate) and clinical staging (based on variables from physical exam and past medical history) 35,36.

Couple eligibility and recruitment

Participants were recruited from among couples referred after CVCT at the Zambia Emory HIV Research Project (ZEHRP) in Lusaka, Zambia 36. Eligible participants were HIV sero-discordant or concordant positive couples cohabiting >12 months who had no indications of infertility or contraindications to contraception, were not pregnant at enrollment, and planned to stay in Lusaka at least one year post enrollment. Eligible women were 18–45 years of age, and eligible men were 18–65 years of age.

Data Analysis

Exclusionary criteria

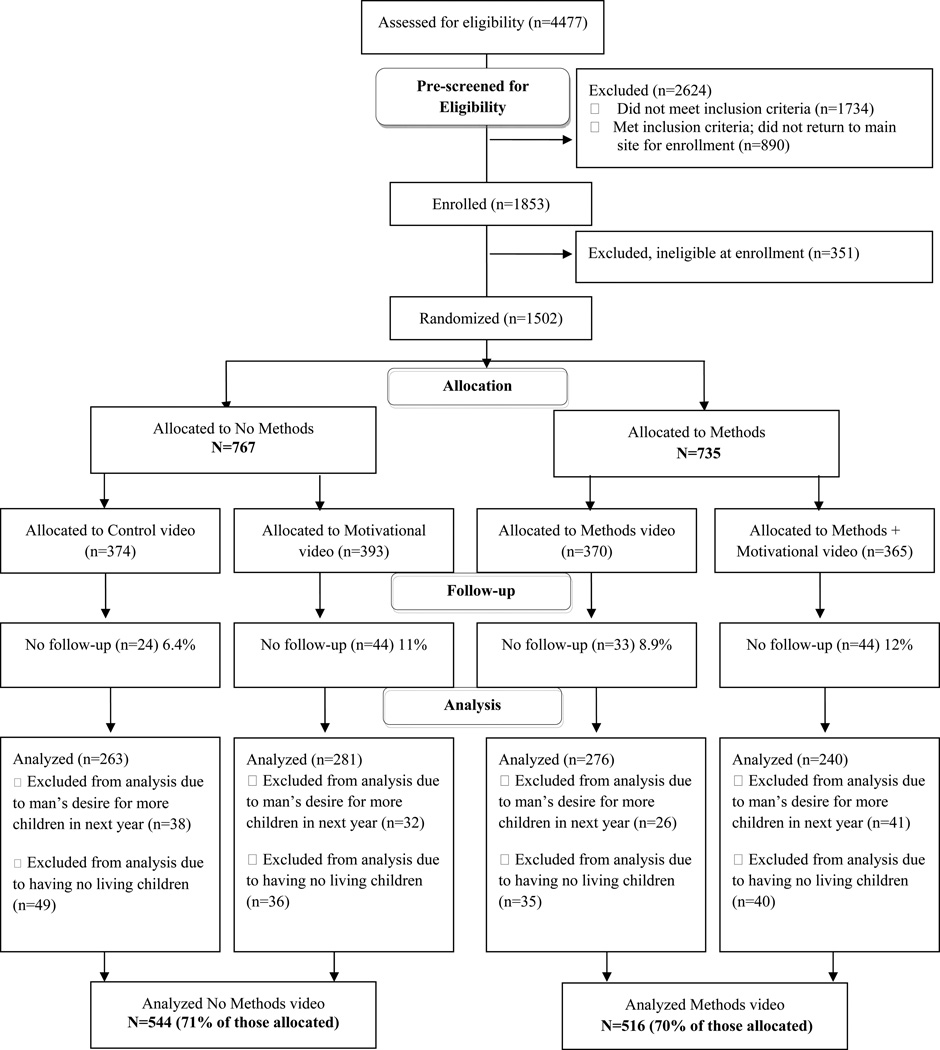

Couples with no children and couples in which the man wanted more children in the next year were not considered to be at risk for avoiding pregnancy and were excluded from this analysis 32. Analyses also excluded couples without at least one follow-up visit. Among randomized couples, the proportion analyzed was similar in the Methods (70%) and No Methods (71%) arms (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram (adapted from the CONSORT 2010 Flow Diagram)

Descriptive analyses

Counts and percentages of categorical participant demographics and means and standard deviations of continuous variables were calculated by intervention arm. Chi-square (or Fisher’s Exact) tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables evaluated significant differences between client demographics and intervention arm to explore potential failures of randomization due to chance. These differences were compared across study arms and stratified by baseline contraceptive use, which was determined to be an effect modifier.

Survival analyses

Predictors of contraceptive initiation or switching methods immediately following the intervention have been previously reported 32. Potential effect modification by couple serostatus and contraceptive use at baseline (prior to the intervention) were evaluated in Cox Proportional Hazards models of time to pregnancy. Baseline covariates that were associated with trial arm, risk factors for the outcome, and which were not intermediates on the exposure-outcome pathway were evaluated as potential confounders. The proportional hazards assumption for intervention arm was evaluated for all Cox models via graphical methods and statistical tests. Log-rank tests evaluated significant differences in Kaplan-Meier survival curves by trial arm.

We also conducted a post hoc analysis evaluating the differences in the distribution of man’s and woman’s fertility intentions by couple serostatus via Chi-square tests. Data analysis was conducted with SAS 9.3 (Cary, North Carolina, US).

RESULTS

Participant flow

After exclusions for ineligibility (n=2975), 1502 couples were randomized to one of the four intervention arms. One hundred and forty-five couples were excluded from the analysis due to having no follow-up visits, 137 couples were excluded due to the man’s desire for more children in the next year, and 160 couples were excluded due to having no living children. The final analysis included 1060 couples (Figure 1).

Randomization

We looked for failures of randomization that might arise by chance by trial arm (Methods video versus No Methods video arms) stratified by woman’s use of a baseline contraceptive method, which was an effect measure modifier. Women who were not using a method at baseline in the “Methods video” arm were less likely to understand English relative to the “No Methods” arm (Table 1). Also among women not using a method at baseline, women in the “Methods video” arms were less likely to have knowledge about the IUD. Among women who were using a method at baseline, those in the “Methods video” arms were more likely to have knowledge of tubal ligation (Table 2). These variables were evaluated as potential confounders in multivariate models stratified by baseline method use.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, health, and fertility characteristics stratified by arm of trial and use of contraception prior to the intervention

| Woman partner not using a method at baseline | Woman partner using a method at baseline | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 782) |

No Method video (N = 384) |

Method video (N = 398) |

Total (N = 278) |

No Method video (N = 160) |

Method video (N = 118) |

|||||||

| n/mean | %/SD | n/mean | %/SD | n/mean | %/SD | n/mean | %/SD | n/mean | %/SD | n/mean | %/SD | |

| Pregnant during follow-up | 92 | 12% | 42 | 11% | 50 | 13% | 45 | 16% | 34 | 21%# | 11 | 9%# |

| Average follow-up time (days)* | 501.7 | 320.2 | 496.1 | 309.3 | 507.2 | 330.6 | 520.2 | 314.1 | 494.2 | 305.2 | 555.5 | 323.8 |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Age of Woman (years)* | 28.8 | 5.6 | 28.9 | 5.6 | 28.7 | 5.6 | 28.6 | 5.4 | 28.1 | 5.4 | 29.4 | 5.5 |

| Age of Man (years)* | 35.0 | 6.5 | 35.2 | 6.3 | 34.9 | 6.7 | 34.9 | 6.8 | 34.7 | 6.7 | 35.2 | 6.8 |

| Number of living children* | 2.2 | 1.4 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 1.5 |

| Monthly household income (per 10,000 Kwacha)* | 33.8 | 55.0 | 36.1 | 63.3 | 31.6 | 45.6 | 35.2 | 43.7 | 35.3 | 48.0 | 35.0 | 37.5 |

| Years cohabitating* | 7.7 | 5.1 | 7.7 | 4.9 | 7.8 | 5.3 | 8.5 | 5.3 | 8.1 | 5.0 | 9.1 | 5.7 |

| Woman understands English | ||||||||||||

| Easily | 201 | 26% | 110 | 29% | 91 | 23% | 68 | 25% | 39 | 25% | 29 | 25% |

| With difficulty/not at all | 579 | 74% | 274 | 71% | 305 | 77% | 209 | 75% | 120 | 75% | 89 | 75% |

| Man understands English | ||||||||||||

| Easily | 481 | 62% | 239 | 62% | 242 | 61% | 174 | 63% | 99 | 62% | 75 | 64% |

| With difficulty/not at all | 300 | 38% | 144 | 38% | 156 | 39% | 103 | 37% | 60 | 38% | 43 | 36% |

| Woman understands Nyanja | ||||||||||||

| Easily | 704 | 90% | 344 | 90% | 360 | 91% | 246 | 89% | 141 | 89% | 105 | 89% |

| With difficulty/not at all | 76 | 10% | 39 | 10% | 37 | 9% | 31 | 11% | 18 | 11% | 13 | 11% |

| Man understands Nyanja | ||||||||||||

| Easily | 674 | 86% | 331 | 86% | 343 | 86% | 249 | 90% | 143 | 90% | 106 | 90% |

| With difficulty/not at all | 107 | 14% | 52 | 14% | 55 | 14% | 28 | 10% | 16 | 10% | 12 | 10% |

| Health and fertility characteristics | ||||||||||||

| HIV serostatus at baseline | ||||||||||||

| Serodiscordant (Woman is positive) | 127 | 16% | 54 | 14% | 73 | 18% | 45 | 16% | 29 | 18% | 16 | 14% |

| Serodiscordant (Man is positive) | 108 | 14% | 54 | 14% | 54 | 14% | 59 | 21% | 38 | 24% | 21 | 18% |

| Concordant positive | 547 | 70% | 276 | 72% | 271 | 68% | 174 | 63% | 93 | 58% | 81 | 69% |

| Woman fertility intentions | ||||||||||||

| Wants more children in the next year | 31 | 4% | 15 | 4% | 16 | 4% | 7 | 3% | 5 | 3% | 2 | 2% |

| Wants more children, but not in the next year | 202 | 26% | 94 | 24% | 108 | 27% | 80 | 29% | 49 | 31% | 31 | 26% |

| Does not want more children | 534 | 68% | 268 | 70% | 266 | 67% | 185 | 67% | 102 | 64% | 83 | 70% |

| Don't know | 14 | 2% | 7 | 2% | 7 | 2% | 5 | 2% | 3 | 2% | 2 | 2% |

| Man fertility intentions | ||||||||||||

| Wants more children, but not in the next year | 296 | 38% | 139 | 36% | 157 | 39% | 99 | 36% | 63 | 40% | 36 | 31% |

| Does not want more children | 450 | 58% | 225 | 59% | 225 | 57% | 160 | 58% | 84 | 53% | 76 | 64% |

| Don't know | 36 | 5% | 20 | 5% | 16 | 4% | 18 | 6% | 12 | 8% | 6 | 5% |

Data shown as means and SDs

Cells may not add up to totals due to missing values

p < 0.0001

Table 2.

Family planning characteristics stratified by arm of trial and use of contraception prior to the intervention

| Woman partner not using a method at baseline | Woman partner using a method at baseline | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 782) |

No Method video (N = 384) |

Method video (N = 398) |

Total (N = 278) |

No Method video (N = 160) |

Method video (N = 118) |

|||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | N | % | |

| Who decides when/if you should have children (reported by woman) | ||||||||||||

| Woman respondent | 28 | 4% | 15 | 4% | 13 | 3% | 9 | 3% | 6 | 4% | 3 | 3% |

| Man partner | 224 | 29% | 106 | 28% | 118 | 30% | 78 | 28% | 45 | 28% | 33 | 28% |

| Couple decides together | 370 | 47% | 182 | 47% | 188 | 47% | 144 | 52% | 80 | 50% | 64 | 54% |

| Extended family | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| No one decides/plans | 156 | 20% | 78 | 20% | 78 | 20% | 46 | 17% | 28 | 18% | 18 | 15% |

| No opinion | 3 | 0% | 3 | 1% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Who decides when/if you should have children (reported by man) | ||||||||||||

| Man respondent | 157 | 20% | 76 | 20% | 81 | 20% | 58 | 21% | 29 | 18% | 29 | 25% |

| Woman partner | 14 | 2% | 5 | 1% | 9 | 2% | 1 | 0% | 1 | 1% | 0 | 0% |

| Couple decides together | 603 | 77% | 298 | 78% | 305 | 77% | 215 | 78% | 128 | 81% | 87 | 74% |

| Extended family | 2 | 0% | 1 | 0% | 1 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| No one decides/plans | 6 | 1% | 4 | 1% | 2 | 1% | 3 | 1% | 1 | 1% | 2 | 2% |

| No opinion | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Woman knowledge (spontaneous or prompted) about | ||||||||||||

| OCPs | 782 | 100% | 384 | 100% | 398 | 100% | 278 | 100% | 160 | 100% | 118 | 100% |

| Injection | 778 | 99% | 383 | 100% | 395 | 99% | 278 | 100% | 160 | 100% | 118 | 100% |

| Norplant implant | 671 | 86% | 336 | 88% | 335 | 84% | 259 | 93% | 151 | 94% | 108 | 92% |

| IUD | 681 | 87% | 347 | 90%# | 334 | 84%# | 252 | 91% | 145 | 91% | 107 | 91% |

| Emergency contraception | 130 | 17% | 64 | 17% | 66 | 17% | 38 | 14% | 20 | 13% | 18 | 15% |

| Tubal ligation | 618 | 79% | 310 | 81% | 308 | 77% | 232 | 83% | 125 | 78%# | 107 | 91%# |

| Vasectomy | 263 | 34% | 130 | 34% | 133 | 33% | 114 | 41% | 64 | 40% | 50 | 42% |

| Contraception methods ever used (past or currently) by woman or partner | ||||||||||||

| OCPs | 462 | 59% | 228 | 59% | 234 | 59% | 239 | 86% | 138 | 86% | 101 | 86% |

| Injection | 217 | 28% | 101 | 26% | 116 | 29% | 144 | 52% | 79 | 49% | 65 | 55% |

| Norplant implant | 5 | 1% | 3 | 1% | 2 | 1% | 10 | 4% | 3 | 2% | 7 | 6% |

| IUD | 9 | 1% | 5 | 1% | 4 | 1% | 10 | 4% | 6 | 4% | 4 | 3% |

| Emergency contraception | 3 | 0% | 2 | 1% | 1 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Woman has worries, concerns, or fears about (if applicable) | ||||||||||||

| OCPs | 664 | 85% | 326 | 85% | 338 | 85% | 264 | 95% | 152 | 95% | 112 | 95% |

| Injection | 529 | 68% | 279 | 73% | 263 | 66% | 223 | 80% | 131 | 82% | 92 | 78% |

| Norplant implant | 282 | 36% | 144 | 38% | 138 | 35% | 106 | 38% | 62 | 39% | 44 | 37% |

| IUD | 284 | 36% | 150 | 39% | 134 | 34% | 120 | 43% | 69 | 43% | 51 | 43% |

| Emergency contraception | 47 | 6% | 20 | 5% | 27 | 7% | 15 | 5% | 9 | 6% | 6 | 5% |

| Tubal ligation | 267 | 34% | 140 | 36% | 127 | 32% | 115 | 41% | 63 | 39% | 52 | 44% |

| Vasectomy | 99 | 13% | 45 | 12% | 54 | 14% | 43 | 15% | 27 | 17% | 16 | 14% |

| FP method chosen immediately after intervention at baseline | ||||||||||||

| Tubal ligation | 11 | 1% | 7 | 2% | 4 | 1% | 2 | 1% | 2 | 1%# | 0 | 0%# |

| Injectables | 339 | 43% | 161 | 42% | 178 | 45% | 48 | 17% | 33 | 21%# | 15 | 13%# |

| IUD | 32 | 4% | 8 | 2% | 24 | 6% | 5 | 2% | 0 | 0%# | 5 | 4%# |

| Norplant implant | 111 | 14% | 57 | 15% | 54 | 14% | 28 | 10% | 15 | 9%# | 13 | 11%# |

| OCPs | 274 | 35% | 142 | 37% | 132 | 33% | 2 | 1% | 0 | 0%# | 2 | 2%# |

| Continue current use | 15 | 2% | 9 | 2% | 6 | 2% | 193 | 69% | 110 | 69%# | 83 | 70%# |

Data shown as means and SDs

OCP = oral contraceptive pills; IUD = intrauterine device

Cells may not add up to totals due to missing values

p = 0.02

Descriptive analyses

A total of 137 pregnancies occurred during follow-up, and average follow-up time was 506.6 days. Women were 29 (SD=6) years old on average, and men were on average 35 (SD=7) years of age. Couples had an average of 2 (SD=1) living children, and Nyanja literacy was high and similar among baseline method users and non-users. Most participants were of concordant positive serostatus (70% of baseline method non-users and 63% of baseline method users). Roughly two-thirds of women and 58% of men did not want more children, regardless of baseline contraceptive use. Men were more likely to want more children, but not in the next year relative to women for both couples not using a contraceptive method at baseline (38% men vs. 26% women) and baseline method users (36% men vs. 29% women) (Table 1).

Roughly half of women reported that the couple decided together whether or not to have more children, and roughly 30% reported that the men decided, regardless of baseline method use. In contrast, the majority of men reported that the couple decided together (77% of baseline non-users and 78% for baseline method users). Among all women, 99% chose to use a modern contraceptive method after the intervention, and this was not different by trial arm (Table 2).

Among women who were not using a method at baseline, most (98%) chose to use a modern contraceptive method immediately after receiving the intervention, with 43% selecting injectables, 35% selecting OCPs, 14% selecting Norplant implant, 4% choosing the IUD, and 1% choosing tubal ligation. The proportion who chose the IUD was higher in the Methods video arm (6%, N=24 vs 2%, N=8; Chi-square=7.76, p=0.005).

Among the 278 women using a modern contraceptive method prior to the intervention, the distribution of methods used was: 174 (63%) OCPs, 91 (33%) injectables, 5 (2%) IUD, 8 (3%) Norplant implant. This distribution did not differ by trial arm (Chi-square p-value=0.261, data not shown). After viewing their assigned intervention videos and being offered the full range of contraceptive methods, 193 (69%) continued their previous method and 85 switched to another method including 2 (1%) tubal ligation, 48 (17%) injectables, 5 (2%) IUD, 28 (10%) Norplant implant, and 2 (1%) OCP. All five of the baseline method users who switched to the IUD had viewed the “Methods” video. The distribution of methods chosen was significantly different between those viewing the “Methods video” versus those not receiving the “Methods video” (p=0.018) (Table 2).

Knowledge of OCPs, injectables, and to a lesser extent, Norplant implant and IUD, was high among all women, as these methods were presented in the IC signed by all participating couples 33. Relative to women using a method prior to the intervention, women who were not using a method had significantly less knowledge (either spontaneous or prompted) about Norplant implant (Chi-square p-value=0.0013), IUD and vasectomy (Chi-square p-value= 0.0246). Women who were not using a method prior to the intervention reported lower historical use of OCPs (Chi-square p-value < 0.0001) and injectables (Chi-square p-value < 0.0001) relative to women who were method users at entry into the study. Conversely, women using a method at baseline had significantly increased worries, concerns, or fears about OCPs (Chi-square p-value < 0.0001) and injectables (Chi-square p-value=0.0002) relative to women not using a method at baseline (Table 2).

Survival analyses

Effect measure modification by both couple serostatus (concordant positive, discordant man positive, and discordant woman positive) and use of a contraceptive method at entry in the study (prior to the intervention) were observed (p-value <0.0001). No confounders (failures of randomization occurring by chance) were significant in multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards models among all couples, stratified by serostatus, or stratified by use of a contraceptive method at entry; therefore, unadjusted models are presented. The Proportional Hazards assumption was met for all models.

Results from the Cox Proportional Hazards Models showed that among couples in which the woman partner was not using a method at entry, there was no significant effect of the intervention on pregnancy incidence, even after stratifying by couple serostatus. Among couples in which the woman was already using a contraceptive method at the time of the intervention, those who viewed the “Methods” video had a significantly increased time to pregnancy relative to those who did not (11/118 vs. 34/160; hazard ratio (HR)=0.38; 95% CI: 0.19–0.75). The effect size was highest in concordant positive couples who viewed the “Methods” video versus concordant positive couples who did not view the “Methods” video (HR=0.22; 95%CI: 0.08–0.58), and couples in which the woman was HIV positive at baseline who viewed the “Methods” video versus couples in which the woman was HIV positive who did not view the “Methods” video (HR=0.23; 95%CI: 0.09–0.55) (data not shown).

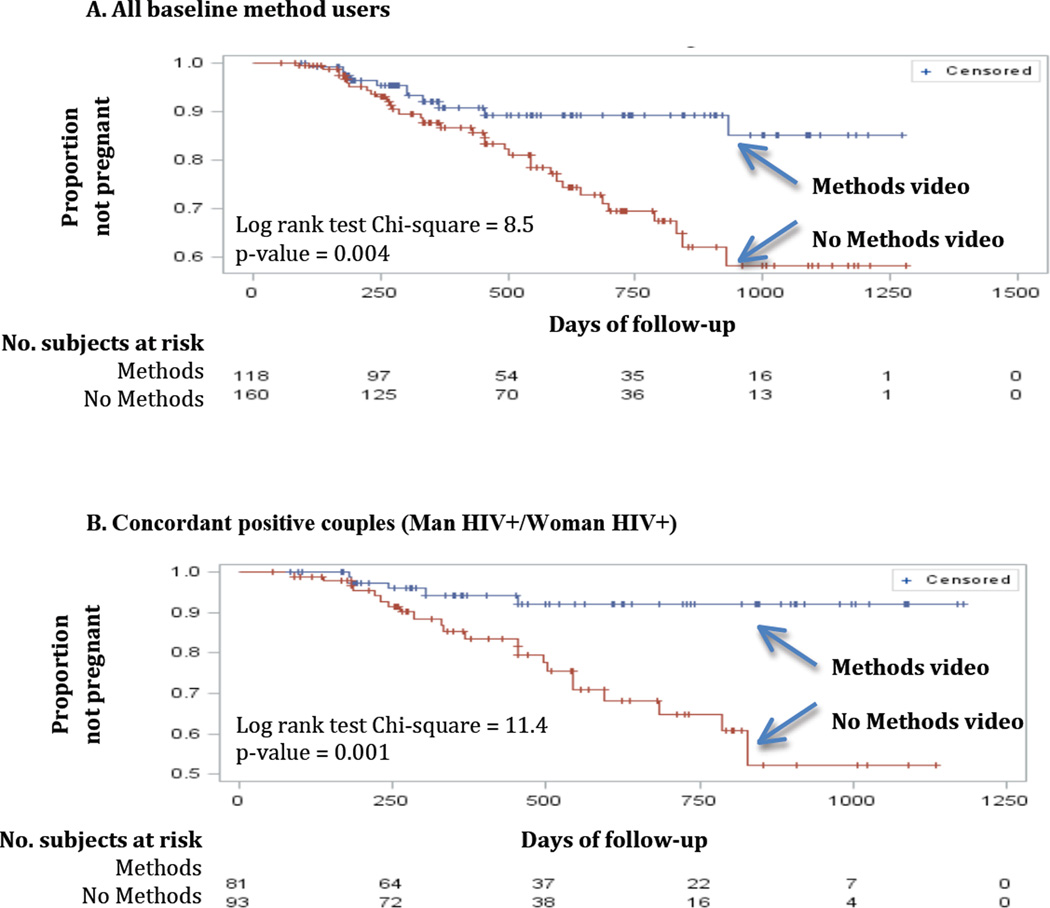

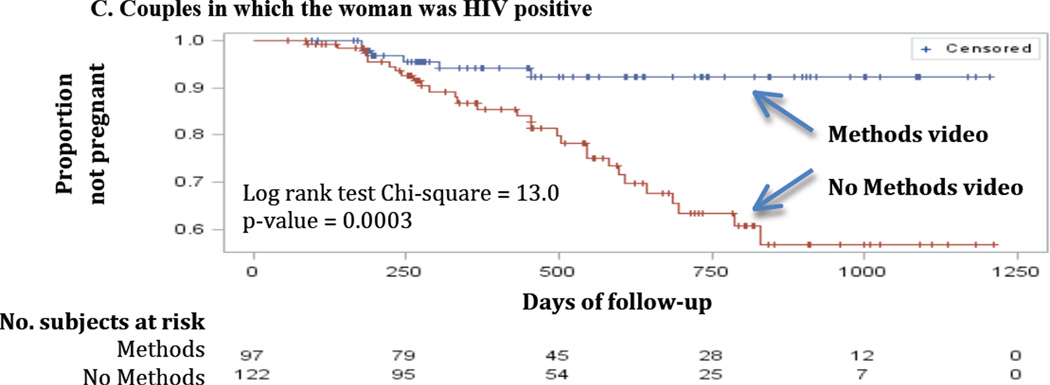

Log-rank tests from Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated for each unadjusted model that also showed a significant intervention effect among couples who were using modern contraception at the time of study entry (Figure 2). Among couples of all serostatus combinations, pregnancy incidence was significantly lower in those who had viewed the “Methods” video (Figure 2A; Log Rank Chi-square=8.45, p-value=0.0036). Again, the association was strongest for concordant positive couples (Figure 2B; Log Rank Chi-square=11.38, p-value=0.0007) and for couples with HIV positive women (Figure 2C; Log Rank Chi-square=13.02 p-value=0.0003).

Figure 2.

Product-limit survival estimates among couples in which the woman partner was using a method at baseline

Post hoc analyses

Given that the intervention was successful among concordant positive couples, we evaluated the fertility intentions of concordant positive versus discordant couples in a post hoc analysis. Men in concordant positive relationships were more likely to not desire more children relative to men in discordant relationships (62% vs. 49%; Chi-square=17.77, p-value=0.0001). There was no significant difference in the distribution of women’s fertility intentions between concordant positive couples and discordant couples (Chi-square=1.75, p-value=0.627), in which 68% and 67% of women did not desire more children, respectively (data not shown).

No harms or adverse events were associated with participation in this study.

DISCUSSION

This randomized controlled trial demonstrated the ability of the video-based “Methods video” intervention to decrease incident pregnancy among a cohort of HIV sero-discordant and concordant positive couples who had previously participated in CVCT and were offered the full range of contraceptive methods. Among couples who were using a contraceptive method prior to the intervention, viewing the Methods video was associated with a substantially reduced pregnancy incidence during followup. In this group, the Methods video intervention had its greatest impact among couples with HIV+ women. The lack of impact in couples who were not contracepting prior to the video-based intervention suggests that repetition and sustained messaging may be needed to increase comfort with all modern contraceptives, and with unfamiliar LARC methods in particular.

In our previous publication of the baseline data, a multivariate regression analysis showed that couples who viewed the “Methods” video were were more likely to adopt injectables (Risk Ratio (RR)=1.55, 95%CI: 1.03–2.34) relative to OCPs, and couples viewing both Methods and Motivational videos were more likely to adopt injectables RR=1.65, 95%CI: 1.07–2.55) and IUD, Norplant implant or tubal ligation (RR=2.06, 95%CI: 1.17–3.44) relative to OCPs. The “Motivational” video alone did not have a significant impact on contraceptive initiation 32, though it was associated with a substantially higher proportion of couples writing wills and naming guardians 32,37.

Although virtually all (99%) participating couples initiated some type of modern contraception after entering the study, the “Methods video” intervention was not associated with lower pregnancy incidence among women using only condoms or no contraception prior to the intervention, regardless of serostatus. More research is needed to determine the barriers women and couples face when deciding to adopt modern contraception, particularly LARC. In a longitudinal study in Rwanda among 684 cohabiting couples recruited to participate in an HIV testing and counseling program, the greatest increase in condom use occurred in couples where the men were being targeted with a specialized message after having received a generic message two years prior 38. Similarly, the CDC Curriculum for Outreach Workers for use in training outreach workers and HIV educators highlights the importance of repetition when delivering HIV prevention messages using the "risk, recognition, response" framework 39.

The “Methods video” intervention was most successful among concordant positive couples and couples in which the woman was positive. Post-hoc analyses showed that fertility goals differed by gender and by couple HIV status: women were less likely than men to want more children, and men in concordant HIV+ unions were less likely to want more children than men in discordant couples. This reinforces the importance of involving men and women jointly in fertility decisions and highlights the importance of having these discussions in the context of known couple HIV status.

Potential limitations to our study include limited generalizability since those who participated may be different from the target population by having an increased desire/receptivity for CVCT and/or family planning (self-selection bias). We expect the results of this study to make inference to the target population of HIV concordant HIV-positive and discordant couples in urban Zambia, a group that will expand given the April 2012 release of WHO Guidelines strongly endorsing CVCT as an HIV prevention strategy. We have previously published that the IC explained all methods and thus increased knowledge of all methods prior to the intervention 32. The IC also clarified that all methods would be offered to all participants, and this may have attenuated the difference between control and intervention groups. For example, there was high uptake of contraceptive methods – including Norplant – even in the “Control” video arm: this highlights the importance of simply providing basic information about, and access to, the full range of contraceptive options. We acknowledge that provider bias may have also affected contraceptive method choice, despite training of project nurses in the provision of all contraceptives and in research methods.

Strengths of this study include its randomized design in which two educational interventions were evaluated concurrently, in comparison to most studies of family planning interventions which are observational or quasi-experimental.

In sub-Saharan Africa with high fertility and a high prevalence of HIV/STI in heterosexual populations, there is a simultaneous need to prevent unplanned pregnancy and HIV transmission. CVCT and family planning service target audiences overlap broadly and can benefit from, and in fact prefer, joint services 40–45. Governments and funding agencies agree that HIV/STI and family planning services should be integrated 46,47. Preventing maternal-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV through prevention of unplanned pregnancies is less expensive than PMTCT with antiretrovirals 48–51.

This study evaluated how a family planning intervention offered within the context of CVCT may reinforce HIV and unplanned pregnancy prevention and address client and provider-level obstacles. This successful integration of CVCT and family planning services, a key goal of the US Global Health Initiative and the PEPFAR program, can provide a paradigm for other countries in Africa and beyond.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge and thank the study participants, staff, interns, and Project Management Group members of the Zambia-Emory HIV Research Project in Lusaka, Zambia. We also thank Michelle Kautzman MD MPH, Laurie Fuller RN MPH, Fong Liu MD MPH, Erin Shutes MPH, Lisa Jones RN MPH, and Tyronza Sharkey MPH for their contributions to study implementation.

source of funding:

This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Child Health and Development [NICHD RO1 HD40125]; National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH R01 66767]; the AIDS International Training and Research Program Fogarty International Center [D43 TW001042]; the Emory Center for AIDS Research [P30 AI050409]; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [NIAID R01 AI51231]; and the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest, including relevant financial interests, activities, relationships, and affiliations.

Meetings at which parts of the data were presented:

Wall KM, Bellington V, Haddad L, Htee Khu N, Vwalika C, Kilembe W, Chomba E, Stephenson R, Kleinbaum D, Nizam A, Brill I, Tichacek A, Allen S. Effect of an intervention to promote contraceptive uptake on incident pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial among HIV positive couples in Zambia. Abstract submission number 247684. AIDS Vaccine 2012. Boston, MA, Sept 2012.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wawer MJ, McNamara R, McGinn T, Lauro D. Family planning operations research in Africa: reviewing a decade of experience. Stud Fam Plann. 1991 Sep-Oct;22(5):279–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caldwell JC, Caldwell P. High fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. Sci. Am. 1990 May;262(5):118–125. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0590-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agyei WK, Migadde M. Demographic and sociocultural factors influencing contraceptive use in Uganda. J Biosoc Sci. 1995 Jan;27(1):47–60. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000006994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernard R. Manual and global inventory of four indicators of population and health. Field Epidemiology and Liaison Office, Epidemiology in Human Reproduction. 1994. Jun 12, AF 06 94. [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Office of Public Affairs. The World Factbook. Rwanda: 2010. [Accessed December 2011]. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2127rank.html?countryName=Rwanda&countryCode=rw®ionCode=af&rank=23#rw. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Central Statistical Office Zambia. Fertility levels, patterns, and trends. Fertility. 2011:99–111. [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Office of Public Affairs. Zambia total fertility rate (TFR) 2010 https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2127.html.

- 8.Carael M. Child-spacing, ecology, and nutrition in the Kivu province of Zaire. In: Page H, Lesthaeghe R, editors. Child-spacing in Tropical Africa -- Traditions and Change. London: Academic Press; 1981. pp. 275–286. [Google Scholar]

- 9.May JF, Mukamanzi M, Vekemans M. Family planning in Rwanda: status and prospects. Stud Fam Plann. 1990 Jan-Feb;21(1):20–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King R, Estey J, Allen S, et al. A family planning intervention to reduce vertical transmission of HIV in Rwanda. Aids. 1995 Jul;9(Suppl 1):S45–S51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.King R, Khana K, Nakayiwa S, et al. 'Pregnancy comes accidentally--like it did with me': reproductive decisions among women on ART and their partners in rural Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:530. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Straten A, King R, Grinstead O, Serufilira A, Allen S. Couple communication, sexual coercion and HIV risk reduction in Kigali, Rwanda. Aids. 1995;9(8):935–944. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199508000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armstrong A. Maintainance payments for child support in souther Africa: using law to promote family planning. Studies in Family Planning. 1992;23(4):217–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bizimungu C. Instruction Ministerielle No 779 du 3 Mars 1988 relative a la promotion du programme de sante familiale dans les etablissements de sante du Rwanda. Imbonezamuryango. 1992;25:20–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trussell J, Lalla AM, Doan QV, Reyes E, Pinto L, Gricar J. Cost effectiveness of contraceptives in the United States. Contraception. 2009 Jan;79(1):5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stanwood NL, Garrett JM, Konrad TR. Obstetrician-gynecologists and the intrauterine device: a survey of attitudes and practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Feb;99(2):275–280. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01726-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ortiz ME, Croxatto HB. Copper-T intrauterine device and levonorgestrel intrauterine system: biological bases of their mechanism of action. Contraception. 2007 Jun;75(6 Suppl):S16–S30. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neukom J, Chilambwe J, Mkandawire J, Mbewe RK, Hubacher D. Dedicated providers of long-acting reversible contraception: new approach in Zambia. Contraception. 2011 May;83(5):447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grabbe K, Stephenson R, Vwalika B, et al. Knowledge, use, and concerns about contraceptive methods among sero-discordant couples in Rwanda and Zambia. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009 Sep;18(9):1449–1456. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Postlethwaite D, Shaber R, Mancuso V, Flores J, Armstrong MA. Intrauterine contraception: evaluation of clinician practice patterns in Kaiser Permanente Northern California. Contraception. 2007 Mar;75(3):177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hubacher D, Vilchez R, Gmach R, et al. The impact of clinician education on IUD uptake, knowledge and attitudes: results of a randomized trial. Contraception. 2006 Jun;73(6):628–633. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Population policies gain momentum among African countries. Afr Popul Newsl. 1992;(62):5–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goliber TJ. Africa's expanding population: old problems, new policies. Popul Bull. 1989 Nov;44(3):5–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simmons R, Hall P, Diaz J, Diaz M, Fajans P, Satia J. The strategic approach to contraceptive introduction. Stud Fam Plann. 1997 Jun;28(2):79–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bwembya M, Mbewe R. Zambia: national long-term forecasting and quantification for family planning commodities, 2009–2015. Arlington, VA: USAID; 2009. Deliver Project, Task order 1; [Google Scholar]

- 26.Central Statistical Office, Zambia, Central Board of Health, Zambia, ORC Macro. Zambia demographic and health survey, 2001–2002. Calverton, MD: Central Statistical Office, Central Board of Health, and ORC Macro; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Rossem R, Meekers D. The reach and impact of social marketing and reproductive health communication campaigns in Zambia. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:352. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biddlecom AE, Fapohunda BM. Covert contraceptive use: prevalence, motivations, and consequences. Stud Fam Plann. 1998 Dec;29(4):360–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baylies C. The impact of HIV on family size preference in Zambia. Reprod Health Matters. 2000 May;8(15):77–86. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(00)90008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Secrecy and silence: why women hide contraceptive use. Popul Briefs. 1998 Sep;4(3):3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaona FA, Katsivo MN, Ondolo H, et al. Factors that determine utilization of modern contraceptives in East, Central and southern Africa. Afr J Health Sci. 1996 Nov;3(4):133–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stephenson R, Vwalika B, Greenberg L, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial to Promote Long-Term Contraceptive Use Among HIV-Serodiscordant and Concordant Positive Couples in Zambia. J Womens Health. 2011 Apr;20(4):567–574. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stephenson R, Grabbe K, Vwalika B, et al. The influence of informed consent content on study participants' contraceptive knowledge and concerns. Stud Fam Plann. 2010 Sep;41(3):217–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2010.00245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stephenson R, Barker J, Cramer R, et al. The demographic profile of sero-discordant couples enrolled in clinical research in Rwanda and Zambia. AIDS Care. 2008 Mar;20(3):395–405. doi: 10.1080/09540120701593497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lifson AR, Allen S, Wolf W, et al. Classification of HIV infection and disease in women from Rwanda. Evaluation of the World Health Organization HIV staging system and recommended modifications. Annals of internal medicine. 1995 Feb 15;122(4):262–270. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-4-199502150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peters PJ, Zulu I, Kancheya NG, et al. Modified Kigali combined staging predicts risk of mortality in HIV-infected adults in Lusaka, Zambia. AIDS research and human retroviruses. 2008 Jul;24(7):919–924. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stephenson R, Mendenhall E, Muzizi L, et al. The influence of motivational messages on future planning behaviors among HIV concordant positive and discordant couples in Lusaka, Zambia. AIDS Care. 2008 Feb;20(2):150–160. doi: 10.1080/09540120701534681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roth DL, Stewart KE, Clay OJ, van Der Straten A, Karita E, Allen S. Sexual practices of HIV discordant and concordant couples in Rwanda: effects of a testing and counselling programme for men. Int J STD AIDS. 2001 Mar;12(3):181–188. doi: 10.1258/0956462011916992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Appendix B - Sample Curriculum for Outreach Workers. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 1994. Simple Screening Instruments for Outreach for Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse and Infectious Diseases. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 11; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stover J. Reducing the costs of effective AIDS control programmes through appropriate targeting of interventions. Paper presented at: International AIDS Conference; Vancouver. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peterman TA, Todd KA, Mupanduki I. Opportunities for targeting publicly funded human immunodeficiency virus counseling and testing. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes & Human Retrovirology. 1996;12(1):69–74. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199605010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sweeney PA, Onorato IM, Allen DM, Byers RH. Sentinel surveillance of human immunodeficiency virus infection in women seeking reproductive health services in the United States, 1988–1989. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1992;79(4):503–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kell PD, Barton SE, Boag FC. Incorporating patients' views in planning services for women with HIV infection. Genitourinary Medicine. 1992;68(4):233–234. doi: 10.1136/sti.68.4.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCarthy GA, Cockell AP, Kell PD, Beevor AS, Boag FC. A women-only clinic for HIV, genitourinary medicine and substance misuse. Genitourinary Medicine. 1992;68(6):386–389. doi: 10.1136/sti.68.6.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carlin EM, Russell JM, Sibley K, Boag FC. Evaluating a designated family planning clinic within a genitourinary medicine clinic. Genitourinary Medicine. 1995;71(2):106–108. doi: 10.1136/sti.71.2.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cates W, Jr., Abdool Karim Q, El-Sadr W, et al. Global development. Family planning and the Millennium Development Goals. Science. 2010 Sep 24;329(5999):1603. doi: 10.1126/science.1197080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cates W, Jr., Stone K. Family Planning, sexually transmitted disease, and contraceptive choice: a literature update Part II. Family Planning Perspectives. 1992;24(3):122–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reynolds HW, Janowitz B, Wilcher R, Cates W. Contraception to prevent HIV-positive births: current contribution and potential cost savings in PEPFAR countries. Sex Transm Infect. 2008 Oct;84(Suppl 2):ii49–ii53. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.030049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leslie J, Munyambanza E, Adamchak S, Grey T, Kirota K. Without Strong Integration of Family Planning into PMTCT Services Clients Remain with a High Unmet Need for Effective Family Planning. International Conference on Family Planning: Research and Best Practices; November 15–18, 2009; Kampala, Uganda. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakakeeto ON, umaranayake L. The global strategy to eliminate HIV infection in infants and young children: a seven-country assessment of costs and feasibility. Aids. 2009 May 15;23(8):987–995. doi: 10.1097/qad.0b013e32832a17e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Petruney T, Harlan SV, Lanham M, Robinson ET. Increasing support for contraception as HIV prevention: stakeholder mapping to identify influential individuals and their perceptions. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10781. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]