SUMMARY

Porphyromonas gingivalis, a black-pigmented, gram-negative anaerobe, is an important etiological agent of periodontal disease. Its ability to survive in the periodontal pocket and orchestrate the microbial/host activities that can lead to disease suggest that P. gingivalis possesses a complex regulatory network involving transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms. The vimA (virulence modulating) gene is part of the 6.15-kb bcp-recA-vimA-vimE-vimF-aroG locus and plays a role in oxidative stress resistance. In addition to the glycosylation and anchorage of several surface proteins including the gingipains, VimA can also modulate sialylation, acetyl coenzyme A transfer, lipid A and its associated proteins and may be involved in protein sorting and transport. In this review, we examine the multifunctional role of VimA and discuss its possible involvement in a major regulatory network important for survival and virulence regulation in P. gingivalis. It is postulated that the multifunction of VimA is modulated via a post-translational mechanism involving acetylation.

INTRODUCTION

The human oral cavity has always been a challenging environment for various bacterial taxa to inhabit. Although home to more the 600 species, only a subset of microbes, which now includes previously unrecognized and uncultivated species, are associated with disease (Dewhirst et al., 2010; Gross et al., 2010; Griffen et al., 2012). The ‘red’ complex, consisting of Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia and Treponema denticola, is well established to be associated with periodontal disease (Holt & Ebersole, 2000; Kumar et al., 2003; Dewhirst et al., 2010). Porphyromonas gingivalis, now designated as a ‘keystone’ species, even when present in low numbers, is able to manipulate the host immune system, so eliciting a major effect on the composition of the oral microbial community which significantly contributes and may be ultimately responsible for the pathology of periodontitis (Hajishengallis et al., 2011; Hajishengallis, 2011; Darveau et al., 2012; Hajishengallis & Lamont, 2012).

Porphyromonas gingivalis is known to possess several outer membrane structures, major outer membrane proteins and secreted proteins that have contributed to cell adherence, survival and virulence (Lamont & Jenkinson, 1998). To facilitate its ‘keystone’ species function, this organism requires a complex regulatory network. Integrated as part of this network are regulatory circuits using transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms that are guided by the external environment including microbial and host-induced cues. A variety of transcriptional regulatory mechanisms such as the two component system (Hasegawa et al., 2003; Nishikawa & Duncan, 2010), extracytoplasmic function sigma factor (Dou et al., 2010), and transposase-mediated regulation (Lewis et al., 2009), have been reported in P. gingivalis. However, a key element in modulating the pathogenic potential of P. gingivalis is the post-translational modification of several of the major surface components. For example, the major proteases, called gingipains, consist of arginine-specific (Arg-gingipain; Rgp) and lysine-specific (Lys-gingipain; Kgp) proteases that are both extracellular and cell-membrane-associated. The maturation pathway of the gingipains is linked to carbohydrate biosynthesis and is regulated by several proteins including the PorR, Por, Sov, Rfa, VimA, VimE and VimF (Vanterpool et al., 2004, 2005a, 2005b, 2006; Sato et al., 2009, 2010; Saiki & Konishi, 2010; Shoji et al., 2011).

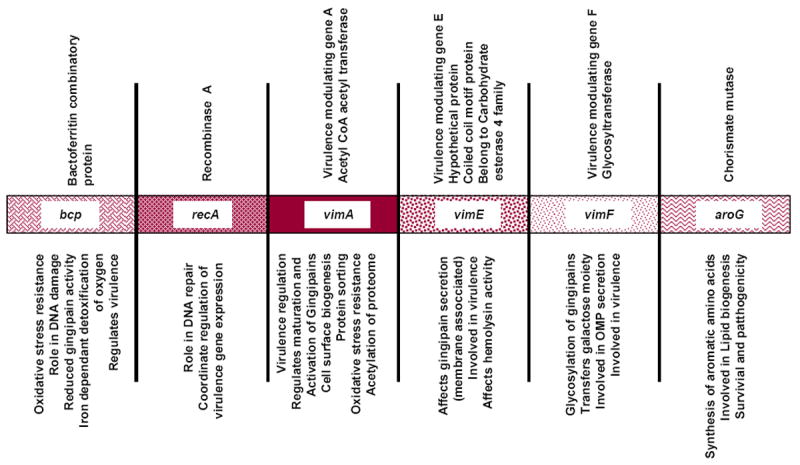

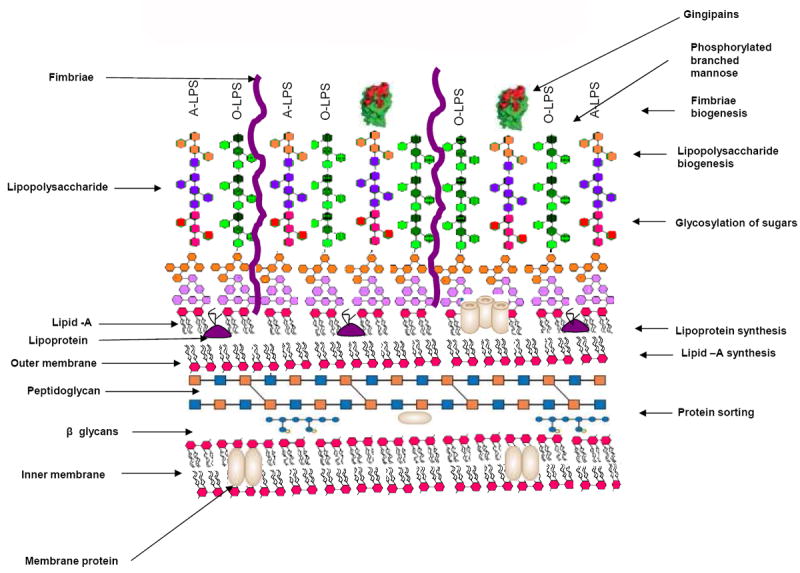

VimA is a 39-kDa protein that is encoded for by the vimA gene. This gene is part of the 6.15-kb bcp-recA-vimA-vimE-vimF-aroG locus (Fig. 1). A role for the vimA gene in oxidative stress resistance has been demonstrated in P. gingivalis, but the VimA protein is believed to be multifunctional (Fig. 2). In addition to the glycosylation and anchorage of several surface proteins including the gingipains, VimA can also modulate sialylation (Aruni et al., 2011), acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) transfer, lipid A and its associated proteins, and may be involved in protein sorting and transport (Aruni et al., 2012). In this review, we examine the multifunctional role of VimA and discuss its possible involvement in a major regulatory network important for survival and virulence regulation in P. gingivalis. It is postulated that the multifunction of VimA is modulated via a post-translational mechanism involving acetylation.

Figure 1. Genome architecture of bcp- aroG locus in P. gingivalis.

Genome architecture of bcp- aroG locus in Porphyromonas gingivalis showing the annotation of the genes (top panel) and their putative functions (bottom panel).

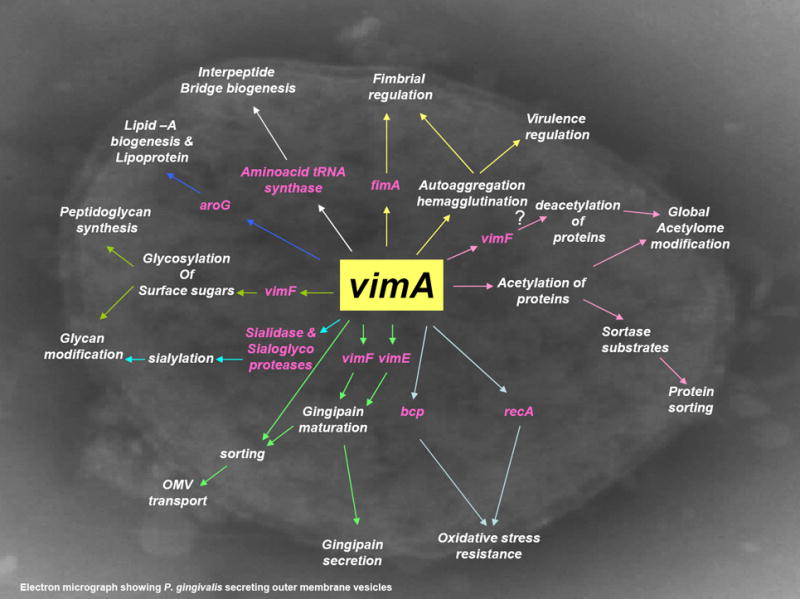

Figure 2. Functions of VimA in surface biogenesis.

Multifunction of VimA in various cell surface modifications. Right panel shows the VimA functions and the left panel shows various surface structures.

vimA IS INVOLVED IN OXIDATIVE STRESS RESISTANCE

There are multiple complex systems that defend and protect P. gingivalis against oxidative damage generated in the inflammatory environment of the periodontal pocket (reviewed in Henry et al., 2012). Components of these systems, which include antioxidant enzymes (Mydel et al., 2006), DNA binding proteins (Meuric et al., 2008), the hemin layer (McKenzie et al., 2012) and enzymatic removal of reactive oxygen species-induced deleterious products, are coordinately regulated (Henry et al., 2008). Multiple transcriptional modulators (including OxyR, RprY and extracytoplasmic function sigma factors) that sense oxidative-stress-generating agents and induce the appropriate response in P. gingivalis have been described (Henry et al., 2008; Lewis et al., 2009; Dou et al., 2010; McKenzie et al., 2012). Collectively, these data suggest that P. gingivalis may have a redundant mechanism(s) to defend against oxidative stress.

Inactivation of the vimA gene in P. gingivalis generated a non-polar isogenic mutant (Abaibou et al., 2001) that showed increased sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide (Vanterpool et al., 2006). This mutant, designated P. gingivalis FLL92, also displayed a non-black-pigmented phenotype and had reduced gingipain activity (Vanterpool et al., 2005b). The involvement of the gingipains in heme acquisition and binding (Okamoto et al., 1998) and the ability of the heme layer to act as an ‘oxidative sink’ to neutralize reactive oxygen intermediates (Smalley et al., 2000, 2004) would be consistent with the sensitivity of P. gingivalis FLL92 to hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress.

This model system has uncovered other mechanisms that may be involved in oxidative stress resistance in P. gingivalis. In the chromosomal DNA of P. gingivalis FLL92 there was an elevated level of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine (8-oxoG) after exposure to hydrogen peroxide (Johnson et al., 2004). The ability to repair these lesions used a novel non-base excision repair mechanism that was upregulated in P. gingivalis FLL92 compared with the wild-type strain (Henry et al., 2008). A gene expression profile using DNA microarray analysis revealed that about 5.7% and 3.45% of the P. gingivalis genome displayed altered expression in response to hydrogen peroxide exposure at 10 and 15 min, respectively in FLL92 compared with the wild-type W83 strain. The P. gingivalis FLL92 isogenic mutant in response to hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress showed upregulation of several genes including some with unknown function and others known to be involved in oxidative stress resistance in other pathogenic bacteria. In particular, after 15 min of exposure to hydrogen peroxide the P. gingivalis vimA mutant had high upregulation (between 9.6 and 11.9-fold) transposase-encoding genes (PG0051, PG0194, PG0812, PG813, PG0944 and PG2169). Increase in transposase activity in response to oxidative stress has previously been reported in P. gingivalis (Diaz et al., 2006). However, we find them to be upregulated only during prolonged exposure (15 min) to oxidative stress and not modulated after 10 min exposure. While the significance of this is unclear, this could be an inherent strategy of P. gingivalis to induce genomic rearrangement that may lead to survival under unstable hostile environmental conditions (Diaz et al., 2006).

In silico analysis of the metabolome of the vimA-defective mutant during oxidative stress indicated an increase in pyruvate synthesis and glycine catabolism that can result in the production of more endogenous CO2. The use of alternative energy substrates such as fumarate and formate was noted (unpublished results). Hence during oxidative stress, P. gingivalis may resort to a metabolic state where the oxidative reactions are reduced and there is a shift to reduction reactions that bring about increase in cellular CO2.

The interaction of VimA with other proteins may also facilitate oxidative stress resistance in P. gingivalis. Pull-down experiments using the recombinant VimA protein showed the ability of this protein to interact with the sialidase protein (Vanterpool et al., 2006). Furthermore, in a vimA mutant, sialidase activity was reduced (Vanterpool et al., 2006). An isogenic mutant defective in the sialidase gene showed increased sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide (Aruni et al., 2011). Release of free monomeric sialic acid when it is cleaved from the sugar chain can detoxify hydrogen peroxide (Iijima et al., 2004a). This reaction reduces the hydrogen peroxide and sialic acid (N-acetylneuraminic acid) into H2O and non-toxic carboxylic acid (Iijima et al., 2004b). The ability of the P. gingivalis sialidase to cleave multiple substrates that could result in the release of sialic acid would be consistent with the increased sensitivity of the sialidase-defective isogenic mutants to hydrogen peroxide compared with the wild-type strain. The VimA-dependent regulation of the sialidase activity in P. gingivalis is unclear and may include both transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms. The sialidase gene was not expressed in the vimA-defective mutant (Aruni et al., 2011).

vimA IS INVOLVED IN CELL SURFACE BIOGENESIS

The cell surface components play an important role in establishing the organism in the host and are involved in adhesion, invasion and colonization. In P. gingivalis, surface components like capsule, fimbria, outer membrane proteins, peptidoglycan and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), contribute to virulence (Lamont & Jenkinson, 1998). Autoaggregation is an important phenomenon in virulence and correlates with the absence of capsule and the presence of fimbriae (Davey & Duncan, 2006). Although non-virulent, it was noted that the P. gingivalis vimA mutant FLL92 showed enhanced autoaggregation (Osbourne et al., 2010). Major differences in the capsule and fimbriae were noted between the wild-type and this vimA-defective mutant. The wild-type showed a well-defined capsule in contrast to a less defined, irregular and fuzzy capsule in FLL92. Also, the FLL92 strain showed distinct fine structures resembling fimbriae that were not present in the wild-type strain (Osbourne et al., 2010). This could be the result of changes in the phenotypic expression of fimbrial protein. This was confirmed using Western blot analysis with anti-FimA antibody on the outer membrane and total protein fractions of W83 and FLL92. The immunoreactive band corresponding to the FimA (between 41 and 43 kDa) was missing in the wild-type W83 strain but was present in the FLL92 outer membrane fraction (Osbourne et al., 2010). Immunogold electron microcopy also identified appendage-like structures in FLL92 that were reactive to the FimA antibody. To confirm that vimA plays a role only at the post-translational level of fimbrial expression, a reverse transcription PCR was performed; the fimA gene was similarly expressed in both the wild-type and the vimA-defective isogenic mutant FLL92 (Osbourne et al., 2010).

To clarify the effect of the vimA mutation on glycosylation of outer-membrane proteins, a lectin assay was performed and the results showed that outer membrane proteins with galactose (β1,3)N-acetylgalactosamine, N-acetyl-α-d-galactosamine, galactose (β1,4)N-acetylglucosamine, N-acetyl-d-galactosamine and sialic acid (N-acetyl neuraminic acid) were affected by the vimA mutation (Osbourne et al., 2010). Ultrastructural studies on the peptidoglycan sacculi of the P. gingivalis vimA mutant showed a distinct difference with uneven surface variations in comparison to that of W83, suggesting a role of vimA in peptidoglycan synthesis (unpublished results). The peptidoglycan sacculus is a rigid exoskeleton structure, which is involved in maintaining cytoplasmic pressure. One likely conclusion from these studies could infer a variation in the structure of the sacculi caused by faulty peptide cross-linkages in the vimA mutant. The cross-linked peptide bridges found in the cell wall typically include alanine (Barnard & Holt, 1985). Alanine tRNA synthetase is involved in alanine transport and formation of peptide cross-linkages. Using the P. gingivalis recombinant VimA protein produced in Escherichia coli, an interaction with alanine tRNA synthetase was demonstrated (Vanterpool et al., 2006). This was confirmed using the VimA chimera where it was also shown to interact with isoleucyl tRNA synthetase in addition to 20 other proteins (Aruni et al., 2012). The direct effect of VimA on the functional role of these proteins is unclear. Of the 21 VimA interacting proteins, a majority were cytoplasmic and membrane-bound, seven were found to be involved in cell surface biogenesis, and all had an N-terminal cleavage signal with C-terminal cell wall sorting motif (Aruni et al., 2012). Among these proteins, five were related to LPS synthesis (Aruni et al., 2012). Further, we have also shown that a defect in vimA causes alteration in lipid A biogenesis and membrane lipoproteins (Aruni et al., 2012). Analysis of the polysaccharide component of LPS after removal of lipid-A showed shorter lengths in the vimA-defective mutant (Vanterpool et al., 2006). Hence, collectively, we could conclude that vimA is involved in cell surface biogenesis.

vimA MODULATES GINGIPAIN ACTIVITY

The proteolytic cleavage of multiple substrates by the P. gingivalis cysteine proteases called gingipains is considered to be important for its survival and to play a significant role in virulence (Eley & Cox, 2003;Vanterpool et al., 2005b). More specifically, these proteases are involved in several processes known to be important for bacterial growth and can compromise cellular integrity and host cell functions by several mechanisms triggered for example, by inactivation of cytokines, platelet aggregation and apoptosis (Lamont & Jenkinson, 1998; Kadowaki et al., 2000; Sheets et al., 2008). Activation of gingipains is associated with several vim genes that are involved in post-translational modification of the gingipains (Abaibou et al., 2001; Vanterpool et al., 2004, 2005a, 2005b, 2006; Osbourne et al., 2010; Aruni et al., 2011, 2012). Glycosylation, which is involved in the addition of carbohydrate moieties to the gingipains, is one of the important post-translational modifications in gingipain biogenesis (Curtis et al., 1999, 2001; Gallagher et al., 2003; Vanterpool et al., 2005b).

Among the vim genes, vimA is a key player in modulating the phenotypic expression of the gingipains. Inactivation of the vimA gene resulted in isogenic mutants that showed decreased gingipain activity during the exponential growth phase (Vanterpool et al., 2005b). These activities, however, increased to approximately 60% during stationary phase in the wild-type strain. Throughout all the growth phases, Rgp and Kgp activities were mostly soluble, in contrast to those of the wild-type strain. Expression of the gingipain genes was unchanged in the vimA-defective mutants compared with the parent strains (Vanterpool et al., 2005b). The gingipain proenzyme species were observed in these mutants providing some of the first evidence for post-translational regulation of protease activity in P. gingivalis (Olango et al., 2003; Vanterpool et al., 2005b). Variation in the glycosylation profile of the gingipains was noted including no immunoreactivity to monoclonal antibody 1B5 (mAb1B5) known to recognize the phosphorylated branched mannan (Vanterpool et al., 2006; Rangarajan et al., 2008). In addition, using methanolysis and gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy analysis to evaluate the monosaccharide composition of the inactive RgpB proenzyme from the P. gingivalis vimA-defective mutant (FLL92), showed that the N-Ac-glucosamine and N-Ac-galactosamine moieties were not detectable in comparison to the active forms of the gingipain (unpublished results).

The vim genes play a coordinated role in the glycosylation of the gingipains (Sheets et al., 2008). Inactivation of the vimE and vimF genes that are downstream of vimA and located on the same operon resulted in isogenic mutants that showed no gingipain activity (Vanterpool et al., 2006). Expression of the gingipain genes was also unchanged in these isogenic mutants compared with the parent strain (Vanterpool et al., 2004, 2005a, 2005b, 2006). The gingipain proenzyme species were also observed in these mutants (Olango et al., 2003; Vanterpool et al., 2005b). However, in contrast to the vimA-defective mutant, which only had the RgpB gingipain cell associated, the vimE-defective and vimF-defective mutants had both cell and extracellular associated inactive forms of the gingipains (Olango et al., 2003; Vanterpool et al., 2005b, 2006). Throughout all the growth phases, no activation of the gingipains was observed. Again, variation in the glycosylation profile of the gingipains including the missing phosphorylated branched mannan was noted (Vanterpool et al., 2006; Rangarajan et al., 2008). Collectively, these observations suggest that the vimE and vimF genes that encode for a putative carbohydrate esterase and glycosyltransferase, respectively (Vanterpool et al., 2005a, 2005b), are essential for the post-translational modification required for gingipain activation.

There are multiple VimA-dependent mechanisms that can modulate gingipain activity in P. gingivalis (Vanterpool et al., 2005b, 2006; Aruni et al., 2012). VimA was shown to interact with proteins such as the HtrA, RegT and sialidases that in other bacteria have been shown to be involved in post-translational regulation of proteases (Vanterpool et al., 2006). Inactivation of the gene encoding these proteins in P. gingivalis resulted in reduced gingipain activity (Roy et al., 2006; Vanterpool et al., 2010; Aruni et al., 2012). In the sialidase-defective mutant, for example, because the level of expression of the gingipain genes was unaltered, it is likely that the sialidase gene is involved in the post-translational regulation of the gingipains. The breakdown of sialic acid residues and sialoconjugates by sialidases contributes to a wide range of important biological functions and conformational stabilization of glycoproteins (Angata & Varki, 2002). Analysis of the monosaccharide composition of the gingipains indicates the presence of at least nine different sugars, including high levels of sialic acid (Rangarajan et al., 2005; Sakai et al., 2007). The level of sialylation and its role in gingipain maturation/activation are unclear and are under further investigation.

VimA IS LIKELY INVOLVED IN PROTEIN SORTING

Covalent attachment of extracellular proteins to the cell wall peptidoglycan is a fundamental feature of cell surface biogenesis in gram-positive bacteria. These cell-wall-anchored surface proteins are known to carry LPXTG, a sortase recognition motif (Schneewind et al., 1995) and use transpeptidase enzymes called sortases to covalently connect their substrates to a target molecule (reviewed in Marraffini et al., 2006). A similar mechanism involving the use of these sortases, as observed in gram-positive bacteria, is less clear in gram-negative bacteria. Although protein secretion mediated through various secretory systems, such as contact-dependent secretion and Type I to Type VI secretory systems in gram-negative bacteria are highly conserved (Thanassi & Hultgren, 2000), the sorting of proteins from the cytoplasm by means of a consensus protein sorting signal is now starting to emerge (Mazmanian et al., 2001). Preferentially observed in bacteria from sediments, soils and biofilms, proteins with several key characteristic sorting signals were contained in a short C-terminal (CTERM) homology domain (Haft et al., 2006). This domain, designated PEP-CTERM, includes a near-invariant motif Pro-Glu-Pro (PEP) that is considered a possible recognition or processing site, followed by a predicted transmembrane helix and a cluster rich in basic amino acids. These target proteins are usually destined to transit cellular membranes during their biosynthesis and undergo additional posttranslational modifications such as glycosylation (Haft et al., 2012).

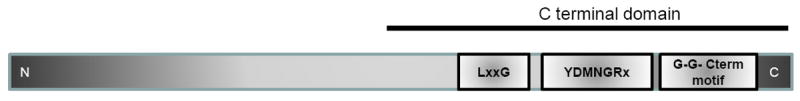

Porphyromonas gingivalis may have multiple protein sorting/secretion systems. In contrast with the P. gingivalis wild-type strain, studies in our laboratory indicate that several proteins were aberrantly expressed or missing from the outer membrane and extracellular fractions of the vimA-defective isogenic mutant (Osbourne et al., 2012). Several of the missing extracellular proteins in P. gingivalis FLL92 carried an N-terminal signal peptide, a common C-terminal motif with a common consensus Gly-Gly CTERM pattern and a polar tail consisting of aromatic amino acid residues. Both the C-terminal motif with its common consensus Gly-Gly CTERM pattern and polar tail are known to have protein sorting characteristics in other organisms (Ton-That et al., 2004; Haft & Varghese, 2011). Other protein pull-down assays using the His-tagged chimeric VimA showed several proteins that contained conserved LXXTG or LPXTG motifs(Aruni et al., 2012). These predicted putative sorting motifs were present in all the membrane or extracellular proteins that interacted with VimA. Hence, the unique C-terminal domain (CTD) with a glycine-rich region and a general sorting signal motif-like region (LxxxG) could be a general mechanism of VimA-mediated protein sorting.

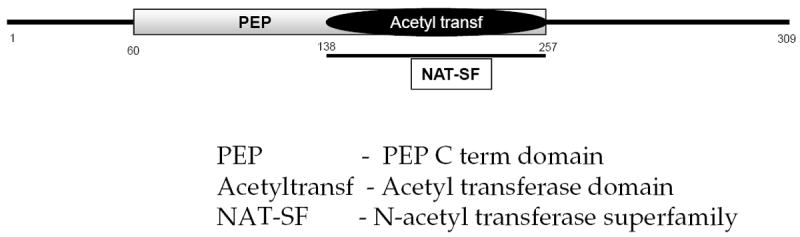

Interestingly, studies from other groups demonstrated that in P. gingivalis, a group of surface proteins, including RgpB, with a common CTD was shown to be exported by a novel secretion system (the Por secretory system; PorSS) to the surface, where they are covalently attached (Sato et al., 2010; Shoji et al., 2011). It was proposed that the CTD acts as a site of recognition by a P. gingivalis processing enzyme(s), possibly a novel sortase-like enzyme that cleaves the CTD sequence and attaches the C-terminal carbonyl to a sugar amine of a novel anionic LPS, which can be modulated by its level of acylation (Pallen et al., 2001; Dramsi et al., 2008; Haurat et al., 2011). The identity of a specific sortase-like enzyme or recognition motif was not identified. Interrogation of these proteins including RgpB that are transported through the PorSS, showed the same Gly-Gly CTERM pattern and the conserved YDMGRX and LXXG motif that we previously identified (Fig. 3; and see Supplementary material Fig. S1). Hence, it is likely that VimA may play a role in this transport/secretion system. This is further supported by the demonstration that mutations in the vimA gene and the other genes that are part of the PorSS had a similar phenotype (Nguyen et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2011). A recently proposed mechanism for protein sorting into the outer membrane vesicles of P. gingivalis showed a critical role for LPS and its level of acylation in this process (Haurat et al., 2011). Only a few of the most abundant proteins identified from the outer membrane vesicles were similar to those that interacted with the VimA chimera and had a general sorting signal motif-like region. It is unclear if they carry any specific sorting signals or use a similar putative VimA-dependent mechanism. In gram-positive bacteria, multiple sortase systems have been described (Dramsi et al., 2008). However, in gram-negative bacteria there is a gap in such information, and this gap requires further exploration. Sortase homologs have only recently been identified in gram-negative bacteria (Pallen et al., 2001), while a pattern of sorting through PEP- CTERM/exosortase was identified in some gram-negative bacteria (Haft et al., 2006), in silico analysis of VimA also showed a DUF482/CH1444 domain that is a part of the PEP-CTERM system (Fig. 4; and see Supplementary material Fig. S2) (Haft et al., 2006; Osbourne et al., 2010). It is likely that in P. gingivalis there may be multiple systems, some of which may have novel characteristics.

Figure 3. Common C- terminal domain architecture of VimA interacting proteins and reported CTD proteins.

Common C- terminal domain (CTD) architecture of VimA interacting proteins and CTD proteins showing three consensus conserved LxxG, YDMNGRx, G-G-Cterm motifs.

Figure 4. Domain architecture of VimA.

Domain architecture of VimA showing conserved acetyl transferase domain, N-acetyl transferase superfamily domain between positions 138 and 257, and a PEP-Cterm domain between amino acid positions 60 and 138.

vimA IS INVOLVED IN PROTEIN ACETYLATION

Post-translational modification of proteins serves as a means for cells to react quickly to changes in the environment. Acetylation and deacetylation in pathogenic bacteria like Salmonella enterica (Starai & Escalante-Semerena, 2004) and Bacillus spp. (Gardner et al., 2006) have previously been found to play an important role in such regulations. Among the various post-translational modifications, acetylation modifications were identified as a major post-translational modification equal to phosphorylation (Smith & Workman, 2009). It is important to note that involvement of protein acetylation has already been reported in a stress-induced transcription network in E. coli (Lima et al., 2011), and a novel feedback inhibition regulating energy production in E. coli was reported for protein acetylation/deacetylation involving the transfer of CoA (Starai et al., 2005). Hence, acetylome modulation could be considered part of a universal switch to regulate important functions of prokaryotes.

There is growing evidence to suggest that VimA is an acetyl-CoA transferase and that it may be involved in protein acetylation. Domain architecture shows a conserved acetyltransferase domain and an N-acetyl tranfserase superfamily domain (Fig. 4; and see Supplementary material Fig. S2). The conserved nature of the vimA gene was noted among various bacteria (Aruni et al., 2011). Orthologs of vimA were found in many anaerobic bacteria such as Clostridium botulinium, Rhodobacter sphaeroides and Parabacteroides distasonis. Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis of the protein sequence also show its molecular relatedness to exopolysaccharide synthesis family proteins among other bacteria and homologous to the acetyl-CoA transferases of other oral bacteria such as Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Rhodobacter shpaeroides (Aruni et al., 2012). A comparison with other P. gingivalis acetyl-CoA transferases, showed VimA to be closely related to the lipid biosynthesis transferase (PG2222) and transpeptidases (PG0794). It showed molecular relatedness with CoA transferase (PG1013) and acetyl transferase (PG1358). Protein modeling showed the conserved α/β/α domain structure of acetyl-CoA N-acetyl transferase superfamily (Osbourne et al., 2010; Aruni et al., 2012).

The VimA acetyltransferase function was demonstrated with its ability to transfer acetyl-CoA to isoleucine (Aruni et al., 2012). The alteration in this transfer resulted in a reduction in branched-chain amino acids of approximately 40% in the P. gingivalis vimA-defective mutants. In addition, VimA was also shown to regulate the levels of acetyl-CoA in P. gingivalis (Aruni et al., 2012). In P. gingivalis, several outer membrane proteins are lipid modified (Yoshimura et al., 2009). One of the common lipid modifications seen on the outer membrane proteins of prokaryotes is a process involving the addition of an acyl group (Eichler & Adams, 2005). In a 3H–labelled palmitic acid assay, the extracellular fraction of the P. gingivalis wild-type strain showed more acylated proteins than the P. gingivalis vimA mutant FLL92 (Osbourne et al., 2010). Collectively, these observations have attributed a role for VimA in the acetylation process in P. gingivalis. Furthermore, variation in the acetylation profile is observed in the vimA-defective mutants compared with the wild-type (unpublished results).

A picture is now emerging that could show a role for acetylation/deacetylation in gingipain biogenesis and protein secretion/localization in P. gingivalis. The outer membrane protein LptO (PG0027) involved in O-deacetylation of LPS has been demonstrated to coordinate secretion/attachment of A-LPS and CTD proteins in P. gingivalis (Chen et al., 2011). In our preliminary studies using monoclonal antibodies in Western blot analysis against N-acetylated lysine, more acetylated proteins were observed in the extracellular and membrane fractions of the wild-type compared with the vimA-defective mutant (unpublished results). In other studies we have shown a common putative sorting motif in the VimA interacting proteins (Aruni et al., 2012), other membrane proteins that are missing in the vimA-defective mutant (Osbourne et al., 2012) and other CTD proteins (Seers et al., 2006; Nguyen et al., 2007; Slakeski et al., 2011). Together, these observations may suggest a common secretion system and raise questions on a mechanism for VimA-dependent acetylation and LptO-dependent deacetylation in the process. This requires further study.

vimA IS INVOLVED IN VIRULENCE REGULATION

Collectively, the P. gingivalis VimA protein has been shown to affect gingipain maturation, sialidase activity, autoaggregation, hemolysis, hemagglutination, LPS synthesis, capsular synthesis and fimbrial expression, and plays a role in the glycosylation and anchorage of several surface proteins (Abaibou et al., 2001; Olango et al., 2003; Vanterpool et al., 2006; Osbourne et al., 2010; Aruni et al., 2011, 2012; Osbourne et al., 2012). These phenotypic traits can be correlated with the virulence of P. gingivalis (Kilian, 1998). Hence, their decreased expression in the vimA-defective mutant is manifested in its increased sensitivity to oxidative stress resistance and reduced ability to invade or induce apoptosis of host epithelial and endothelial cells (Olango et al., 2003). This is also consistent with the reduced virulence of the vimA-defective mutant of P. gingivalis compared with the parent strain in a mouse model (Abaibou et al., 2001).

The multiple phenotypic properties of the vimA-defective mutant can result from a cascade of events suggesting that the vimA gene product is part of a complex regulatory network using both direct and indirect transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms. For example, carbohydrate biosynthesis is linked to the maturation pathway of the gingipains. A VimA-dependent alteration in the addition of the appropriate carbohydrate moieties to the gingipains results in a mutant with decreased gingipain activity, hemolysis and hemagglutination and increased sensitivity to oxidative stress (Vanterpool et al., 2005b, 2006). Similarly, a defect in LPS biosynthesis in P. gingivalis can influence the attachment of the gingipains to the cell surface, and autoaggregation (Osbourne et al., 2010; Yamaguchi et al., 2010). Several genes, including vimA, have shown the importance of the O side chain polysaccharide (O-LPS) and anionic polysaccharide (A-LPS) in these processes (Shoji et al., 2002; Vanterpool et al., 2004, 2005a, 2010; Sato et al., 2009; Yamaguchi et al., 2010). Analysis of cell surface LPSs isolated from the parent W83 strain and isogenic mutants grown under the same conditions showed that the LPS of the vimA-defective mutant was truncated compared with that of the wild type (Vanterpool et al., 2006). Removal of the lipid A from the LPS resulted in a polysaccharide profile of the vimA-defective mutant in which the LPS was shorter than that of the parent strain, also suggesting that in the absence of VimA, polysaccharide modification could result in the loss of surface-associated gingipain proteinases and strong autoaggregation. VimA was found to mediate acetyl-CoA transfer to isoleucine that can result in a reduction in branched-chain amino acids and lipid A content in P. gingivalis (Aruni et al., 2012). The metabolic pathway of isoleucine degradation is known to provide the substrate (acetyl-CoA) that is important in lipid biosynthesis (Mahmud et al., 2005). The lower level of acetyl-CoA observed in the mutants could help to explain the VimA-dependent effect on lipid A biosynthesis that is possible via fatty acid chain elongation (Bugg & Brandish, 1994; Tatar et al., 2007). It is noteworthy that some of the proteins (PG1346, PG1347 and PG1348) that are predicted to play a role in lipid biosynthesis interacted with the purified VimA (Aruni et al., 2012). Together, the alterations in this pathway(s) could lead to the incorrect localization or targeting of proteins, resulting in reduced gingipain activity, hemolysis and hemagglutination. Because the gingipains are involved in hemin acquisition and uptake (Sheets et al., 2008), increased sensitivity to oxidative stress is expected as observed in the vimA-deficient mutant.

The inability to express the sialidase gene in the vimA-defective mutant could highlight the transcriptional effect of VimA on gene expression in P. gingivalis. A unifying theme that could therefore satisfy both transcriptional and post-translational VimA-dependent mechanisms may include acetylation. There is a gap in our understanding about the impact of protein acetylation on bacterial gene expression or physiology. In E. coli there is evidence that an acetylation of the RNA polymerase subunit can play crucial roles in the transcription regulation of a periplasmic stress-responsive promoter when those cells were grown in an environment that induces protein acetylation (Lima et al., 2011). A similar VimA-dependent mechanism in P. gingivalis is unclear and is the subject of further investigation. Outer-membrane proteins including the gingipains that are glycosylated with acetylated carbohydrates moieties were affected by the vimA mutation. These observations could implicate VimA-dependent acetylation in gingipain biogenesis and could explain the truncated A-LPS species. Finally, there is evidence of a role for acetylation in protein sorting and transport in gram-negative bacteria (Craig et al., 2011). The missing or aberrantly expressed proteins in the vimA-defective mutants and their interaction with the purified VimA protein raise questions on a role for acetylation in protein sorting and transport in P. gingivalis. This awaits further confirmation in the laboratory.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

The VimA protein is conserved in many bacterial species and multifunction in P. gingivalis (Fig. 5). It is functionally characterized as an acetyl-CoA transferase in P. gingivalis and is involved in the acetylation process via acetyl-CoA, one of the keystone molecules of central metabolism. Acetylation is now emerging as a significant player with a broad impact on bacterial physiology/pathogenesis and could be as important as other post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation. Collectively, our observations have supported a role for the VimA protein in virulence modulation in P. gingivalis via its impact on the organism’s acetylome. In addition to enhancing the ability of bacteria to subvert the innate immune system (Moynihan & Clarke, 2011), acetylation is also known to be important in bacterial antimicrobial resistance (Strahilevitz et al., 2009). It is noteworthy that the vimA-defective mutant has reduced virulence and is more sensitive to globomycin and vancomycin (Osbourne et al., 2010). Taken together, VimA function should be an important target for therapeutic intervention. A comprehensive understanding of the VimA-dependent post-translational regulatory mechanism(s) awaits further investigation.

Figure 5. Operon function of vimA showing modulation of other related genes.

vimA regulates fimA and fimbrial expression (Osbourne et al., 2010). amino acid tRNA synthase, alanine tRNA synthase and isoleucine tRNA synthase are involved in transport of amino acids and formation of interpeptide bridges of peptidoglycans (Osbourne et al., 2010; Aruni et al., 2011a). vimA interacts with vimF in glycosylation of surface sugars and peptidoglycan synthesis. In association with vimA, vimE and vimF are involved in gingipain maturation and secretion (Vanterpool et al., 2005a, 2005b). vimA modulates glycan modification and sialidase activity (Aruni et al., 2011b). vimA is involved in acetylation of proteins, lipid biogenesis and mediates protein sorting (Aruni et al., 2011a; Osbourne et al., 2012). vimA is involved in autoaggregation and hemagglutination and thereby in virulence modulation (Vanterpool et al., 2004, 2006; Osbourne et al., 2010).

Supplementary Material

Figure S1 Common C- terminal domain architecture of VimA interacting proteins and reported C-terminal domain (CTD) proteins. Multiple sequence alignment of CTD proteins and the VimA-interacting proteins showing three consensus conserved LxxG, YDMNGRx, G-G-Cterm motifs.

Figure S2 Multiple sequence alignment of VimA with related proteins from other organisms.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Loma Linda University and Public Health Services Grants DE13664, DE019730, DE019730 04S1, DE022508, DE022724 from NIDCR (to H.M.F).

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- Abaibou H, Chen Z, Olango GJ, Liu Y, Edwards J, Fletcher HM. vimA gene downstream of recA is involved in virulence modulation in Porphyromonas gingivalis W83. Infect Immun. 2001;69:325–335. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.325-335.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angata T, Varki A. Chemical diversity in the sialic acids and related alpha-keto acids: an evolutionary perspective. Chem Rev. 2002;102:439–469. doi: 10.1021/cr000407m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruni W, Vanterpool E, Osbourne D, et al. Sialidase and sialoglycoproteases can modulate virulence in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 2011;79:2779–2791. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00106-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruni AW, Lee J, Osbourne D, et al. VimA-dependent modulation of acetyl-CoA levels and lipid A biosynthesis can alter virulence in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 2012;80:550–564. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06062-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard MR, Holt SC. Isolation and characterization of the peptidoglycans from selected gram-positive and gram-negative periodontal pathogens. Can J Microbiol. 1985;31:154–160. doi: 10.1139/m85-030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugg TD, Brandish PE. From peptidoglycan to glycoproteins: common features of lipid-linked oligosaccharide biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;119:255–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YY, Peng B, Yang Q, et al. The outer membrane protein LptO is essential for the O-deacylation of LPS and the co-ordinated secretion and attachment of A-LPS and CTD proteins in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Mol Microbiol. 2011;79:1380–1401. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig JW, Cherry MA, Brady SF. Long-chain N-acyl amino acid synthases are linked to the putative PEP-CTERM/exosortase protein-sorting system in Gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:5707–5715. doi: 10.1128/JB.05426-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MA, Duse-Opoku J, Rangarajan M. Cysteine proteases of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2001;12:192–216. doi: 10.1177/10454411010120030101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MA, Thickett A, Slaney JM, et al. Variable carbohydrate modifications to the catalytic chains of the RgpA and RgpB proteases of Porphyromonas gingivalis W50. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3816–3823. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.3816-3823.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darveau RP, Hajishengallis G, Curtis MA. Porphyromonas gingivalis as a potential community activist for disease. J Dent Res. 2012;91:816–820. doi: 10.1177/0022034512453589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey ME, Duncan MJ. Enhanced biofilm formation and loss of capsule synthesis: deletion of a putative glycosyltransferase in Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:5510–5523. doi: 10.1128/JB.01685-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewhirst FE, Chen T, Izard J, et al. The human oral microbiome. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:5002–5017. doi: 10.1128/JB.00542-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz PI, Slakeski N, Reynolds EC, Morona R, Rogers AH, Kolenbrander PE. Role of oxyR in the oral anaerobe Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:2454–2462. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.7.2454-2462.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou Y, Osbourne D, McKenzie R, Fletcher HM. Involvement of extracytoplasmic function sigma factors in virulence regulation in Porphyromonas gingivalis W83. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010;312:24–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02093.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dramsi S, Magnet S, Davison S, Arthur M. Covalent attachment of proteins to peptidoglycan. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:307–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler J, Adams MW. Posttranslational protein modification in Archaea. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2005;69:393–425. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.3.393-425.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eley BM, Cox SW. Proteolytic and hydrolytic enzymes from putative periodontal pathogens: characterization, molecular genetics, effects on host defenses and tissues and detection in gingival crevice fluid. Periodontol 2000. 2003;31:105–124. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2003.03107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher A, duse-Opoku J, Rangarajan M, Slaney JM, Curtis MA. Glycosylation of the Arg-gingipains of Porphyromonas gingivalis and comparison with glycoconjugate structure and synthesis in other bacteria. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2003;4:427–441. doi: 10.2174/1389203033486974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner JG, Grundy FJ, Henkin TM, Escalante-Semerena JC. Control of acetyl-coenzyme A synthetase (AcsA) activity by acetylation/deacetylation without NAD+ involvement in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:5460–5468. doi: 10.1128/JB.00215-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffen AL, Beall CJ, Campbell JH, et al. Distinct and complex bacterial profiles in human periodontitis and health revealed by 16S pyrosequencing. ISME J. 2012;6:1176–1185. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross EL, Leys EJ, Gasparovich SR, et al. Bacterial 16S sequence analysis of severe caries in young permanent teeth. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:4121–4128. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01232-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haft DH, Paulsen IT, Ward N, Selengut JD. Exopolysaccharide-associated protein sorting in environmental organisms: the PEP-CTERM/EpsH system. Application of a novel phylogenetic profiling heuristic. BMC Biol. 2006;4:29. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-4-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haft DH, Payne SH, Selengut JD. Archaeosortases and exosortases are widely distributed systems linking membrane transit with posttranslational modification. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:36–48. doi: 10.1128/JB.06026-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haft DH, Varghese N. GlyGly-CTERM and rhombosortase: a C-terminal protein processing signal in a many-to-one pairing with a rhomboid family intramembrane serine protease. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28886. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G. Immune evasion strategies of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Oral Biosci. 2011;53:233–240. doi: 10.2330/joralbiosci.53.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Lamont RJ. Beyond the red complex and into more complexity: the polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis (PSD) model of periodontal disease etiology. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2012;27:409–419. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2012.00663.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Liang S, Payne MA, et al. Low-abundance biofilm species orchestrates inflammatory periodontal disease through the commensal microbiota and complement. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:497–506. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa Y, Nishiyama S, Nishikawa K, et al. A novel type of two-component regulatory system affecting gingipains in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Microbiol Immunol. 2003;47:849–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2003.tb03451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haurat MF, duse-Opoku J, Rangarajan M, et al. Selective sorting of cargo proteins into bacterial membrane vesicles. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:1269–1276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.185744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry LG, McKenzie RM, Robles A, Fletcher HM. Oxidative stress resistance in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Future Microbiol. 2012;7:497–512. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry LG, Sandberg L, Zhang K, Fletcher HM. DNA repair of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine lesions in Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:7985–7993. doi: 10.1128/JB.00919-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt SC, Ebersole JL. Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, and Tannerella forsythia: the “red complex”, a prototype polybacterial pathogenic consortium in periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2000;38:72–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima R, Takahashi H, Namme R, Ikegami S, Yamazaki M. Novel biological function of sialic acid (N-acetylneuraminic acid) as a hydrogen peroxide scavenger. FEBS Lett. 2004a;561:163–166. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima R, Takahashi H, Namme R, Ikegami S, Yamazaki M. Novel biological function of sialic acid (N-acetylneuraminic acid) as a hydrogen peroxide scavenger. FEBS Lett. 2004;561:163–166. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson NA, McKenzie R, McLean L, Sowers LC, Fletcher HM. 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine is removed by a nucleotide excision repair-like mechanism in Porphyromonas gingivalis W83. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:7697–7703. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.22.7697-7703.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadowaki T, Nakayama K, Okamoto K, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis proteinases as virulence determinants in progression of periodontal diseases. J Biochem. 2000;128:153–159. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilian M. Clonal basis of bacterial virulence. In: Guggenheim B, Shapiro S, editors. Oral Biology at the Turn of the Century. S Basel, Switzerland: Karger AG; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar PS, Griffen AL, Barton JA, Paster BJ, Moeschberger ML, Leys EJ. New bacterial species associated with chronic periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2003;82:338–344. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont RJ, Jenkinson HF. Life below the gum line: pathogenic mechanisms of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1244–1263. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1244-1263.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JP, Iyer D, Anaya-Bergman C. Adaptation of Porphyromonas gingivalis to microaerophilic conditions involves increased consumption of formate and reduced utilization of lactate. Microbiology. 2009;155:3758–3774. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.027953-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima BP, Antelmann H, Gronau K, et al. Involvement of protein acetylation in glucose-induced transcription of a stress-responsive promoter. Mol Microbiol. 2011;81:1190–1204. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07742.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud T, Wenzel SC, Wan E, et al. A biosynthetic pathway to isovaleryl-CoA in myxobacteria: the involvement of the mevalonate pathway. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:322–330. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marraffini LA, Dedent AC, Schneewind O. Sortases and the art of anchoring proteins to the envelopes of gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:192–221. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.70.1.192-221.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazmanian SK, Ton-That H, Schneewind O. Sortase-catalysed anchoring of surface proteins to the cell wall of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:1049–1057. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie RM, Johnson NN, Aruni W, Dou Y, Masinde G, Fletcher HM. Differential response of Porphyromonas gingivalis to varying levels and duration of hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress. Microbiology. 2012;158:2465–2479. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.056416-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuric V, Gracieux P, Tamanai-Shacoori Z, Perez-Chaparro J, Bonnaure-Mallet M. Expression patterns of genes induced by oxidative stress in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2008;23:308–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2007.00429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan PJ, Clarke AJ. O-Acetylated peptidoglycan: controlling the activity of bacterial autolysins and lytic enzymes of innate immune systems. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43:1655–1659. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mydel P, Takahashi Y, Yumoto H, et al. Roles of the host oxidative immune response and bacterial antioxidant rubrerythrin during Porphyromonas gingivalis infection. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e76. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen KA, Travis J, Potempa J. Does the importance of the C-terminal residues in the maturation of RgpB from Porphyromonas gingivalis reveal a novel mechanism for protein export in a subgroup of Gram-negative bacteria? J Bacteriol. 2007;189:833–843. doi: 10.1128/JB.01530-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa K, Duncan MJ. Histidine kinase-mediated production and autoassembly of Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbriae. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:1975–1987. doi: 10.1128/JB.01474-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto K, Nakayama K, Kadowaki T, Abe N, Ratnayake DB, Yamamoto K. Involvement of a lysine-specific cysteine proteinase in hemoglobin adsorption and heme accumulation by Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21225–21231. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olango GJ, Roy F, Sheets SM, Young MK, Fletcher HM. Gingipain RgpB is excreted as a proenzyme in the vimA-defective mutant Porphyromonas gingivalis FLL92. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3740–3747. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.7.3740-3747.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osbourne DO, Aruni W, Roy F, et al. The role of vimA in cell surface biogenesis in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Microbiology. 2010;156:2180–2193. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.038331-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osbourne D, Wilson Aruni A, Dou Y, Perry C, Boskovic DS, Roy F, Fletcher HM. VimA dependent modulation of secretome in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2012;27:420–435. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2012.00661.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallen MJ, Lam AC, Antonio M, Dunbar K. An embarrassment of sortases – a richness of substrates? Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:97–102. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)01956-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangarajan M, Aduse-Opoku J, Paramonov N, et al. Identification of a second lipopolysaccharide in Porphyromonas gingivalis W50. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:2920–2932. doi: 10.1128/JB.01868-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangarajan M, Hashim A, duse-Opoku J, Paramonov N, Hounsell EF, Curtis MA. Expression of Arg-Gingipain RgpB is required for correct glycosylation and stability of monomeric Arg-gingipain RgpA from Porphyromonas gingivalis W50. Infect Immun. 2005;73:4864–4878. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.8.4864-4878.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy F, Vanterpool E, Fletcher HM. HtrA in Porphyromonas gingivalis can regulate growth and gingipain activity under stressful environmental conditions. Microbiology. 2006;152:3391–3398. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.29147-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saiki K, Konishi K. The role of Sov protein in the secretion of gingipain protease virulence factors of Porphyromonas gingivalis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010;302:166–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai E, Naito M, Sato K, et al. Construction of recombinant hemagglutinin derived from the gingipain-encoding gene of Porphyromonas gingivalis, identification of its target protein on erythrocytes, and inhibition of hemagglutination by an interdomain regional peptide. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:3977–3986. doi: 10.1128/JB.01691-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Kido N, Murakami Y, Hoover CI, Nakayama K, Yoshimura F. Lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis-related genes are required for colony pigmentation of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Microbiology. 2009;155:1282–1293. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.025163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Naito M, Yukitake H, et al. A protein secretion system linked to bacteroidete gliding motility and pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:276–281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912010107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneewind O, Fowler A, Faull KF. Structure of the cell wall anchor of surface proteins in Staphylococcus aureus. Science. 1995;268:103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.7701329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seers CA, Slakeski N, Veith PD, et al. The RgpB C-terminal domain has a role in attachment of RgpB to the outer membrane and belongs to a novel C-terminal-domain family found in Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:6376–6386. doi: 10.1128/JB.00731-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets SM, Robles-Price AG, McKenzie RM, Casiano CA, Fletcher HM. Gingipain-dependent interactions with the host are important for survival of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Front Biosci. 2008;13:3215–3238. doi: 10.2741/2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji M, Ratnayake DB, Shi Y, et al. Construction and characterization of a nonpigmented mutant of Porphyromonas gingivalis: cell surface polysaccharide as an anchorage for gingipains. Microbiology. 2002;148:1183–1191. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-4-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji M, Sato K, Yukitake H, et al. Por secretion system-dependent secretion and glycosylation of Porphyromonas gingivalis hemin-binding protein 35. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slakeski N, Seers CA, Ng K, et al. C-terminal domain residues important for secretion and attachment of RgpB in Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:132–142. doi: 10.1128/JB.00773-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalley JW, Birss AJ, Silver J. The periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis harnesses the chemistry of the mu-oxo bishaem of iron protoporphyrin IX to protect against hydrogen peroxide. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;183:159–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb08951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalley JW, Thomas MF, Birss AJ, Withnall R, Silver J. A combination of both arginine- and lysine-specific gingipain activity of Porphyromonas gingivalis is necessary for the generation of the micro-oxo bishaem-containing pigment from haemoglobin. Biochem J. 2004;379:833–840. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KT, Workman JL. Introducing the acetylome. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:917–919. doi: 10.1038/nbt1009-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starai VJ, Escalante-Semerena JC. Identification of the protein acetyltransferase (Pat) enzyme that acetylates acetyl-CoA synthetase in Salmonella enterica. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:1005–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starai VJ, Gardner JG, Escalante-Semerena JC. Residue Leu-641 of Acetyl-CoA synthetase is critical for the acetylation of residue Lys-609 by the Protein acetyltransferase enzyme of Salmonella enterica. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26200–26205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504863200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahilevitz J, Jacoby GA, Hooper DC, Robicsek A. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance: a multifaceted threat. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:664–689. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00016-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatar LD, Marolda CL, Polischuk AN, van Leeuwen D, Valvano MA. An Escherichia coli undecaprenyl-pyrophosphate phosphatase implicated in undecaprenyl phosphate recycling. Microbiology. 2007;153:2518–2529. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/006312-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanassi DG, Hultgren SJ. Multiple pathways allow protein secretion across the bacterial outer membrane. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:420–430. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00111-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ton-That H, Marraffini LA, Schneewind O. Protein sorting to the cell wall envelope of Gram-positive bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1694:269–278. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanterpool E, Aruni AW, Roy F, Fletcher HM. regT can modulate gingipain activity and response to oxidative stress in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Microbiology. 2010;156:3065–3072. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.038315-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanterpool E, Roy F, Fletcher HM. The vimE gene downstream of vimA is independently expressed and is involved in modulating proteolytic activity in Porphyromonas gingivalis W83. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5555–5564. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.5555-5564.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanterpool E, Roy F, Fletcher HM. Inactivation of vimF, a putative glycosyltransferase gene downstream of vimE, alters glycosylation and activation of the gingipains in Porphyromonas gingivalis W83. Infect Immun. 2005a;73:3971–3982. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.3971-3982.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanterpool E, Roy F, Sandberg L, Fletcher HM. Altered gingipain maturation in vimA- and vimE-defective isogenic mutants of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 2005b;73:1357–1366. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1357-1366.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanterpool E, Roy F, Zhan W, Sheets SM, Sandberg L, Fletcher HM. VimA is part of the maturation pathway for the major gingipains of Porphyromonas gingivalis W83. Microbiology. 2006;152:3383–3389. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.29146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi M, Sato K, Yukitake H, Noiri Y, Ebisu S, Nakayama K. A Porphyromonas gingivalis mutant defective in a putative glycosyltransferase exhibits defective biosynthesis of the polysaccharide portions of lipopolysaccharide, decreased gingipain activities, strong autoaggregation, and increased biofilm formation. Infect Immun. 2010;78:3801–3812. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00071-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura F, Murakami Y, Nishikawa K, Hasegawa Y, Kawaminami S. Surface components of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Periodontal Res. 2009;44:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2008.01135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Common C- terminal domain architecture of VimA interacting proteins and reported C-terminal domain (CTD) proteins. Multiple sequence alignment of CTD proteins and the VimA-interacting proteins showing three consensus conserved LxxG, YDMNGRx, G-G-Cterm motifs.

Figure S2 Multiple sequence alignment of VimA with related proteins from other organisms.