Abstract

Few studies have compared hospitalisations before and after antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation in the same patients. We analysed the cost of hospitalisations among 3,906 adult patients in two South African hospitals, 30% of whom initiated ART. Hospitalisations were 50% and 40% more frequent and 1.5 and 2.6 times more costly at a CD4 cell count <100 cells/mm3 when compared to 200–350 cells/mm3 in the pre-ART and ART period, respectively. Mean inpatient cost per patient year was USD 117 (95% confidence interval, CI, 85–158) for patients on ART and USD 72 (95% CI, 56–89) for pre-ART patients. Raising ART eligibility thresholds could avoid the high cost of hospitalisation before and immediately after ART initiation.

Keywords: hospitalisation, in-patient, admission, resource-limited setting, pre-ART

INTRODUCTION

Worldwide, the introduction of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has resulted in a large decrease in hospital admissions amongst HIV-positive patients. Analyses from seven North American and European countries showed a decrease in frequency, average length of hospital stay, and cost per stay of between 32% and 77% in patients on ART compared to those not on ART[1–9]. The reduction in cost due to decreased need for inpatient care has been used to make the economic case for public-sector provision of ART in many high-income countries[10–18]. Initiating ART at low CD4 cell counts, however, has been strongly associated with high inpatient costs[3,4]. Data from low- and middle-income countries show that a significant number of HIV-infected patients on ART still require hospitalisation, especially those initiating at low CD4 counts [19–23].

Few studies have measured rates of hospitalisation in a single cohort both before and after ART initiation to evaluate the effect of treatment on hospital admissions[10,17,22,24,25]. South Africa, a middle-income country, started its public-sector ART programme in 2004. Though several studies have examined the programme’s cost and cost-effectiveness[19,20,22–30], only a handful have included a description of inpatient cost in patients on and off ART in the public sector[20,24,26,27]. None of these studies controlled for patients’ CD4 count, making it hard to compare studies across cohorts with different levels of disease severity.

To establish whether ART reduces hospitalisations while controlling for the patients’ CD4 counts, we compared hospitalisation rates and costs in a South African cohort of HIV-positive patients before and after ART initiation stratified by patients’ current CD4 count.

METHODS

We analysed data from an adult HIV cohort study[31–33] conducted from July 2003 to October 2010 at Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital, a large, urban, tertiary hospital in Soweto in Gauteng Province, and Tintswalo Hospital, a rural hospital in Mpumalanga Province. Patients were recruited after testing HIV positive in the same hospital and were provided with pre-ART HIV care (regular clinic visits for CD4 count monitoring and nurse-led care for opportunistic infections) and initiated on ART once diagnosed with WHO stage 4 disease or a CD4 count <200 cells/mm3[34,35]. Recruiting at HIV testing allowed us to include a sizable group of patients who were followed up until they became ART eligible and then were started on ART and continued to be followed up. Eligible patients for this analysis were ≥18 years old with at least one follow-up visit and one CD4 count after enrollment into the study. Participants were interviewed about their demographic and socioeconomic characteristics and medical history at baseline and about admission and discharge dates of hospitalisations and reasons for admission both at baseline and at follow-up visits four to seven months apart. CD4 counts were collected at enrollment and up to six-monthly thereafter.

Patient baseline characteristics were summarised using descriptive statistics. Hospital admissions occurring during pre-ART and ART periods were stratified by most recent CD4 count in the same six-month time period as the admission. For this we divided person-time for each subject into 6-month periods, starting at enrollment into the study for pre-ART person-time and the date of treatment initiation for person-time on ART. For each 6-month period a patient contributed one observation indicating whether hospitalisation occurred in this period, as well as a current CD4 cell count, which was the first CD4 cell count within that period of observation. For missing CD4 count data (30.2%), we created 25 randomly imputed datasets each for the pre-ART and the ART populations, with missing values modeled on existing data (hospitalisation, site, square root of available CD4 counts and time from either enrollment or ART initiation), and took the mean of the imputed CD4 counts for each missing observation[36]. We estimated incident rate ratios (IRR) of hospitalisation stratified by CD4 counts in the same six-month period.

We estimated the cost of hospitalisations from the health care provider perspective using cohort data on length of stay and the 2008 cost per patient-day equivalent (PDE) of the hospitals’ districts[37]. The cost per PDE is a proxy of cost per inpatient-day and is collected by all public-sector hospitals in South Africa, dividing total hospital expenditure during a financial year by the total number of hospital visits[38]. The cost per PDE for Baragwanath Hospital was USD 164.19, and the cost per PDE for Tintswalo Hospital was USD 176.29. All costs are presented in 2009 USD using the 2009 average currency conversion rate of 1 USD=7.11 ZAR.

Ethical approval was granted by review boards of the University of the Witwatersrand and Boston University.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Of 3,906 patients in our analysis, 140 (3.6%) initiated ART prior to enrollment into the study and 913 (23.4%) initiated ART after being enrolled. Overall patients were predominately female (76.6%) with a median age of 33 years (inter-quartile range, IQR, 28–39). Pre-ART patients had a median CD4 count of 269 cells/mm3 (IQR 136–442) at study enrollment, while ART patients had a median CD4 count of 154 cells/mm3 (IQR 91–239) at study enrollment which declined to a median CD4 count of 117 cells/mm3 (IQR 57–183) at treatment initiation. Median time in pre-ART care prior to initiation onto ART was 7.0 months (IQR 1.5–15.9). Patients on treatment were predominately (71%) treated with stavudine, lamivudine and efavirenz, the most common first-line regimen in South Africa until 2010.

Frequency of hospitalisations

Among the 3,906 patients, 534 hospitalisations occurred during a median follow-up of 13.1 months (IQR 6.3–28.2). 344 (64%) hospitalisations were in pre-ART patients, while 190 (36%) occurred after ART initiation (Table 1). Most patients had a single admission; however, 28 patients in the pre-ART period and 19 patients in the ART period had more than one admission, with a maximum of 5 and 4 admissions per patient in the pre-ART and ART period, respectively. The leading reasons for admission in patients not on ART were pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) (15.1%), Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (6.4%), and trauma (5.5%); in patients on ART they were pulmonary TB (15.2%), Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (7.9%), and headache of any kind (6.8%). The incidence of hospitalisations related to pulmonary TB was 0.74 and 1.0 per 100 patient years in the pre-ART and ART period, respectively; the incidence of admissions for extrapulmonary TB was 0.13 and 0.3 per 100 patient years, respectively. During the first 6 months on ART, the incidence of admissions for pulmonary TB was, at 2.8 per 100 patient years, almost 3 times as high, pointing at the possibility of immune constitution syndrome.

Table 1.

Hospitalisation rates and cost by current CD4 cell count and site (urban versus rural) in patients before and after ART initiation in a prospective cohort study in two sites in South Africa.

| CD4 cell count stratum | Total patient years (%) | Number of hospitalisations | Hospitalisation rate per 100 patient years (95% CI) | Crude IRR1 of hospitalisation by CD4 count (95% CI2) | Mean length of stay [days] (95% CI) | Mean cost per stay [2009 USD] (95% CI) | Mean inpatient cost per patient year in cohort [2009 USD] (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Both sites

| |||||||

|

Pre-ART3

| |||||||

| ≤100 cells/mm3 | 602.8 (8.6) | 60 | 10.0 (7.6–12.8) | 1.0 | 10.4 (7.4–13.4) | 1,759 (1,254–2,263) | 176 (95–290) |

| 101–200 cells/mm3 | 1,233.9 (17.6) | 78 | 6.3 (5.0–7.9) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 8.6 (5.9–11.2) | 1,453 (988–1,919) | 92 (49–152) |

| 201–350 cells/mm3 | 2,275.6 (32.5) | 109 | 4.8 (3.9–5.8) | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | 8.7 (6.7–10.6) | 1,452 (1,126–1,778) | 70 (44–103) |

| >350 cells/mm3 | 2,889.5 (41.3) | 97 | 3.4 (2.7–4.1) | 0.3 (0.2–0.5) | 7.8 (5.6–10.0) | 1,290 (934–1,645) | 44 (25–67) |

|

| |||||||

| All pre-ART patients | 7,001.7 | 344 | 4.9 (4.4–5.4) | - | 8.7 (7.5–9.9) | 1,460 (1,267–1,657) | 72 (56–89) |

|

| |||||||

|

On ART

| |||||||

| ≤100 cells/mm3 | 134.8 (5.3) | 27 | 20.0 (13.2–29.1) | 1.0 | 12.1 (6.6–17.5) | 2,043 (1,128–2,957) | 409 (149–860) |

| 101–200 cells/mm3 | 456.9 (17.4) | 44 | 9.6 (7.0–12.9) | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | 13.4 (8.0–18.7) | 2,241 (1,345–3,137) | 216 (94–405) |

| 201–350 cells/mm3 | 1024.8 (35.2) | 75 | 7.3 (5.8–9.2) | 0.4 (0.2–0.6) | 9.3 (7.4–11.2) | 1,559 (1,241–1,876) | 114 (72–173) |

| >350 cells/mm3 | 1123.7 (42.1) | 44 | 3.9 (2.8–5.3) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 6.9 (4.8–9.0) | 1,158 (805–1,511) | 45 (23–80) |

|

| |||||||

| All ART patients | 2740.2 | 190 | 6.9 (6.0–8.0) | - | 10.1 (8.4–11.8) | 1,693 (1,409–1,976) | 117 (85–158) |

|

| |||||||

|

Urban clinic

| |||||||

|

Pre-ART

| |||||||

| ≤100 cells/mm3 | 357.2 (6.9) | 40 | 11.2 (8.0–15.2) | 1.0 | 8.9 (4.9–13.0) | 1,465 (801–2,129) | 164 (64–324) |

| 101–200 cells/mm3 | 827.1 (16.0) | 57 | 6.9 (5.2–8.9) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 6.4 (5.2–7.5) | 1,049 (861–1,236) | 72 (45–110) |

| 201–350 cells/mm3 | 1,695.6 (32.6) | 88 | 5.2 (4.2–6.4) | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | 7.6 (5.8–9.5) | 1,256 (950–1,562) | 65 (40–100) |

| >350 cells/mm3 | 2,314.6 (44.6) | 90 | 3.9 (3.1–7.8) | 0.3 (0.3–0.5) | 7.6 (5.3–9.9) | 1,253 (876–1,631) | 49 (27–127) |

|

| |||||||

| All pre-ART patients | 5,194.5 | 275 | 5.3 (4.7–5.9) | - | 7.6 (6.4–8.7) | 1,242 (1,057–1,428) | 66 (50–84) |

|

| |||||||

|

On ART

| |||||||

| ≤100 cells/mm3 | 96.1 (4.4) | 16 | 16.6 (9.5–27.0) | 1.0 | 12.0 (3.6–20.4) | 1,970 (595–3,345) | 328 (57–903) |

| 101–200 cells/mm3 | 355.0 (16.1) | 34 | 9.6 (6.6–13.4) | 0.6 (0.3–1.0) | 12.3 (6.1–18.4) | 2,014 (1,001–3,027) | 193 (66–406) |

| 201–350 cells/mm3 | 833.7 (37.8) | 53 | 6.4 (4.8–8.3) | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | 9.3 (6.8–11.8) | 1,524 (1,110–1,938) | 97 (53–161) |

| >350 cells/mm3 | 918.5 (41.7) | 34 | 3.7 (2.6–5.2) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 6.4 (3.9–8.9) | 1,053 (648–1,457) | 39 (17–76) |

|

| |||||||

|

| |||||||

| All ART patients | 2203.3 | 137 | 6.2 (5.2–7.4) | - | 9.6 (7.5–11.7) | 1,581 (1,239–1,923) | 98 (64–142) |

|

| |||||||

|

Rural clinic

| |||||||

|

Pre-ART

| |||||||

| ≤100 cells/mm3 | 245.6 (13.6) | 20 | 8.1 (5.0–12.6) | 1.0 | 13.3 (9.1–17.5) | 2.,345 (1,608–3,081) | 191 (80–388) |

| 101–200 cells/mm3 | 406.7 (22.5) | 21 | 5.2 (3.2–7.9) | 0.6 (0.3–1.4) | 14.5 (5.1–23.9) | 2,552 (894–4,210) | 132 (29–333) |

| 201–350 cells/mm3 | 580.0 (32.1) | 21 | 3.6 (2.2–5.5) | 0.4 (0.2–0.9) | 12.9 (6.6–19.2) | 2,275 (1,171–3,379) | 82 (26–186) |

| >350 cells/mm3 | 574.9 (31.8) | 7 | 1.2 (0.5–2.5) | 0.1 (0.06–0.4) | 10.0 (4.4–15.6) | 1,763 (776–2,750) | 21 (4–69) |

|

| |||||||

| All pre-ART patients | 1,807.1 | 69 | 3.8 (3.0–4.8) | - | 13.2 (9.7–16.7) | 2,328 (1,716–2,939) | 89 (51–141) |

|

| |||||||

|

On ART

| |||||||

| ≤100 cells/mm3 | 38.7 (7.2) | 11 | 28.4 (14.2–50.9) | 1.0 | 12.2 (4.7–19.7) | 2,148 (826–3,469) | 611 (117–1766) |

| 101–200 cells/mm3 | 101.9 (19.0) | 10 | 9.8 (4.7–18.0) | 0.3 (0.1–0.9) | 17.1 (4.4–19.8) | 3,015 (783–5,246) | 296 (37–944) |

| 201–350 cells/mm3 | 191.1 (35.6) | 22 | 11.5 (7.2–17.4) | 0.4 (0.2–0.9) | 9.3 (6.7–12.0) | 1,643 (1,174–2,111) | 189 (85–367) |

| >350 cells/mm3 | 205.2 (38.2) | 10 | 4.9 (2.3–9.0) | 0.2 (0.06–0.4) | 8.6 (3.9–13.2) | 1,516 (692–2,340) | 74 (16–211) |

|

| |||||||

| All ART patients | 536.9 | 53 | 9.9 (7.4–12.9) | - | 11.2 (8.4–14.1) | 1,982 (1,473–2,492) | 196 (109–321) |

incident rate ratios

confidence interval

antiretroviral therapy

As current CD4 count increased, the rate of hospitalisation decreased. Hospitalisation rates were highest for patients with CD4 counts ≤100 cells/mm3. Patients with a CD4 count of >350 cells/mm3 had a reduction in the rate of hospitalisation compared with patients with a CD4 count of <100 cells/mm3 of 70% pre-ART, and of 80% under ART (pre-ART IRR 0.3, 95%CI: 0.2–0.5; ART IRR 0.2, 95% CI: 0.1–0.3). Hospitalisation rates were higher for ART patients than pre-ART patients in all CD4 strata, with most of this difference being driven by the rural cohort, a much smaller population. When removing events unlikely to be HIV related (trauma and accidents; 43 events in the pre-ART period and 6 in the ART period), events in patients initiating ART with a CD4 cell count above 200 cells/mm3, and all events in the first 3 months after ART initiation, the average rates of hospitalisation in the pre-ART and ART cohorts did not change, and the effect was still significant (Table 2A–2C).

Table 2A.

Hospitalisation rates and cost by current CD4 cell count with non-HIV related events removed

| CD4 cell count stratum | Total patient years (%) | Number of hospitalisations | Hospitalisation rate per 100 patient years | Mean length of stay [days] (95% CI) | Mean cost per stay [2009 USD] (95% CI) | Mean inpatient cost per patient year in cohort [2009 USD] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Both sites

| ||||||

|

Pre-ART1

| ||||||

| ≤100 cells/mm3 | 591.9 (8.6) | 59 | 9.9 (7.6–12.9) | 9.8 (6.6–13.0) | 1,749 (1,236–2,263) | 138 (94–292) |

| 101–200 cells/mm3 | 1,216.6 (17.8) | 76 | 6.2 (4.9–7.8) | 8.1 (5.3–10.9) | 1,485 (1,009–1,961) | 113 (49–153) |

| 201–350 cells/mm3 | 2,215.2 (32.3) | 99 | 4.5 (3.6–5.4) | 7.8 (5.7–9.9) | 1,443 (1,090–1,795) | 58 (39–97) |

| >350 cells/mm3 | 2,825.4 (41.3) | 92 | 3.2 (2.6–4.9) | 6.4 (4.3–8.4) | 1,207 (869–1,544) | 39 (23–76) |

|

| ||||||

| All pre-ART patients | 6,849.1 | 326 | 4.7 (4.3–5.3) | 7.8 (6.6–9.0) | 1,442 (1,240–1,643) | 68 (53–87) |

|

| ||||||

|

On ART

| ||||||

| ≤100 cells/mm3 | 133.9 (5.0) | 26 | 19.4 (12.7–28.5) | 12.3 (6.7–18.0) | 2,089 (1,143–3,036) | 406 (145–865) |

| 101–200 cells/mm3 | 452.4 (16.8) | 44 | 9.7 (7.1–13.1) | 13.4 (8.0–18.7) | 2,241 (1,345–3,137) | 218 (95–411) |

| 201–350 cells/mm3 | 1001.3 (37.3) | 70 | 7.0 (5.4–8.8) | 9.5 (7.4–11.5) | 1,586 (1,249–1,923) | 111 (67–169) |

| >350 cells/mm3 | 1097.6 (40.9) | 42 | 3.8 (2.8–5.2) | 7.0 (4.8–9.2) | 1,173 (804–1,542) | 45 (23–80) |

|

| ||||||

| All ART patients | 2,685.2 | 182 | 6.8 (5.8–7.8) | 10.2 (8.5–12.0) | 1,721 (1,426–2,016) | 117 (83–157) |

antiretroviral therapy

Table 2C.

Hospitalisation rates and cost by current CD4 cell count in patients before and after ART initiation after removing events during the first three months after ART initiation

| CD4 cell count stratum | Total patient years (%) | Number of hospitalisations | Hospitalisation rate per 100 patient years (95% CI) | Mean length of stay [days] (95% CI) | Mean cost per stay [2009 USD] (95% CI) | Mean inpatient cost per patient year in cohort [2009 USD] (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Both sites

| ||||||

|

Pre-ART

| ||||||

| ≤100 cells/mm3 | 603 (9) | 60 | 10.0 (7.6–12.8) | 10.4 (7.4–13.4) | 1,759 (1,254–2,263) | 176 (95–290) |

| 101–200 cells/mm3 | 1,234 (18) | 78 | 6.3 (5.0–7.9) | 8.6 (5.9–11.2) | 1,453 (988–1,919) | 92 (49–152) |

| 201–350 cells/mm3 | 2,276 (33) | 109 | 4.8 (3.9–5.8) | 8.7 (6.7–10.6) | 1,452 (1,126–1,778) | 70 (44–103) |

| >350 cells/mm3 | 2,890 (41) | 97 | 3.4 (2.7–4.1) | 7.8 (5.6–10.0) | 1,290 (934–1,645) | 44 (25–67) |

|

| ||||||

| All pre-ART patients | 7,001.7 | 344 | 4.9 (4.4–5.4) | 8.7 (7.5–9.9) | 1,460 (1,267–1,657) | 72 (56–89) |

|

| ||||||

|

On ART

| ||||||

| ≤100 cells/mm3 | 137.8 (5) | 21 | 15.2 (9.4–23.3) | 11.5 (5.2–17.8) | 1,914 (879–2,948) | 292 (83–687) |

| 101–200 cells/mm3 | 468.1 (17) | 25 | 5.3 (3.5–7.9) | 10.2 (4.6–15.8) | 1,694 (768–2,320) | 90 (27–183) |

| 201–350 cells/mm3 | 1,048.5 (38) | 60 | 5.7 (4.4–7.4) | 9.7 (7.3–12.0) | 1,617 (1,230–2,004) | 93 (54–148) |

| >350 cells/mm3 | 1,134 (41) | 39 | 3.4 (2.4–4.7) | 6.3 (4.6–8.0) | 1,055 (763–1,347) | 36 (18–63) |

|

| ||||||

| All ART patients | 2,788.4 | 145 | 5.2 (4.4–6.1) | 9.1 (7.5–10.8) | 1,522 (1,248–1,796) | 79 (55–110) |

Cost of hospitalisations

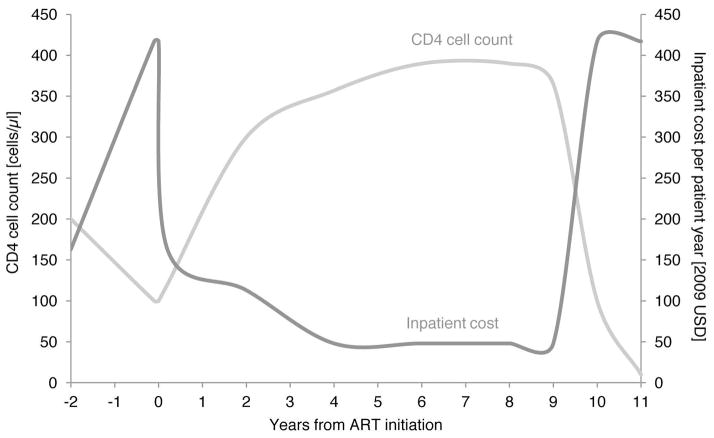

Mean length of stay (LOS) per hospitalisation was 8.7 days (95% confidence interval, CI, 7.5–9.9) for pre-ART patients and 10.1 days (8.4–11.8) for ART patients and decreased with increasing CD4 count in both populations (Table 1). Mean LOS was slightly higher amongst ART vs. pre-ART patients in all CD4 strata except at >350 cells/mm3 and was higher in the rural clinic, regardless of ART status. As a result, the inpatient cost per patient year was higher for ART patients in every stratum, and higher in the rural than in the urban site in almost all strata, partly due to the higher rural cost per PDE. The resulting mean inpatient cost per patient year for ART patients was 63% higher than for pre-ART patients (USD 117 vs. 72). Regardless of treatment status, hospital stays were longest and most costly in patients with a CD4 count <100 cells/mm3, with mean inpatient cost per patient year being 4 times higher at <100 cells/mm3 than at >350 cells/mm3 in the pre-ART period, and 9 times higher in the ART period. Figure 1A shows inpatient cost as a function of CD4 count over the lifetime of a representative patient, extrapolated from the mean inpatient cost per CD4 cell count stratum found in our analysis.

Figure 1.

Figure 1A. Schematic of development of CD4 cell count and inpatient cost per patient year before and after ART initiation.

ART indicates antiretroviral therapy; USD, US dollars. CD4 cell count development is modelled for a hypothetical individual, based on a summary of South African cohort studies[38]; inpatient cost is based on the mean inpatient cost per patient year by CD4 cell count stratum in this study.

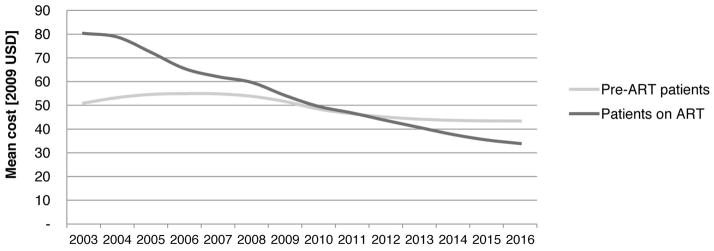

Figure 1B. Mean inpatient cost per patient year pre-ART and on ART in the national ART programme

Impact on the average inpatient cost per patient in the national treatment programme

We parameterised a previously published model of the cost of the South African national ART programme[40,41] with the results of this analysis. Between financial years 2012/13 and 2016/17, the total inpatient cost of patients on ART is projected to increase from USD 85 million per year to USD 121 million (5% of total programme cost) as a result of a planned increase in patient numbers from the current 1.7 million to 3.6 million in 2017. The mean inpatient cost per patient year on ART, however, will decrease by 9% from USD 37 to USD 34 as a result of a maturation of the cohort on ART and redistribution into higher CD4 counts. From 2010/11 onwards, the average annual inpatient cost of patients on ART is lower than that of patients not on ART (Figure 1B).

DISCUSSION

Our study shows that, as in high-income countries[3,4], hospitalisations in HIV-infected adults in South Africa are more frequent, longer, and more costly at lower CD4 counts. We found this to be true regardless of ART status. Patients on ART were hospitalised more often and for longer durations than pre-ART patients. This difference can be explained in part by a higher risk of immune constitution syndrome (IRIS) in patients initiating ART at lower CD4 counts, especially in a population with high TB co-infection rates[21,42]. The incidence of hospitalisations related to pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis, the opportunistic infections most frequently associated with IRIS in South Africa[21,42], was higher in the ART than in the pre-ART cohort, and highest in the 6 months immediately after ART initiation. Likewise, the difference in hospitalisation frequency and cost between the pre-ART and ART populations was driven by the rural population and could at least in part be due to a bias of physicians towards patients on ART who they have already invested in and whose prognosis is far better.

Similar to our analysis, three of four studies of the cost of inpatient care for public-sector patients on ART in South Africa showed an increase in inpatient care cost for patients on ART, with a median inpatient cost per stay in 2009 USD of USD 1,769 (range 1,319 –2,080)[19,20,27]. Our mean cost per stay of patients on ART of USD 1,642 is comparable. A study of a private South African medical aid programme showed a dramatically increased inpatient cost in the 6 months around ART initiation, when CD4 cell counts are at their lowest[22]. When comparing our mean annual per patient inpatient cost of USD 110 to the median cost of outpatient care in 2009 USD for patients on ART in South Africa from a number of published studies, USD 1,233 (range 1,078 to 1,287)[23,28–30], inpatient care adds about 10% to the total annual per patient cost of a patient on ART. It thus accounts for a small but not trivial share of the total cost of caring for HIV/AIDS patients in South Africa.

A potential limitation of our study is the assumption that the published cost per patient-day equivalent is a good proxy for the inpatient costs of HIV-positive patients, which could lead to an over- or underestimation of real inpatient cost. However, a recent in-depth study of the inpatient cost of patients on ART in a different hospital in Johannesburg has shown that cost per PDE is very similar to total per day cost as evaluated in a bottom-up cost analysis using the detailed review of inpatient files[19]. Secondly, since our study cohort had a higher median CD4 count at ART initiation than most public-sector clinics in South Africa, the cost of inpatient care for patients on ART was lower than is likely in routine care. Lastly, while diagnoses were available for all admissions included in this study, their accuracy was somewhat limited by the experience and expertise of the attending health care workers as well as their access to diagnostic modalities, especially in the rural cohort.

Conclusion

Our findings provide evidence to support earlier initiation of ART in low- and middle-income countries. We saw a decrease in hospital admission rates by 50%, and of cost by 250%, when comparing CD4 200–350 to ≤100 in the pre-ART period. Currently, allowing patients’ CD4 counts to drop to very low levels before initiating them on ART burdens the health system threefold: firstly through the high cost of inpatient care immediately before and after ART initiation, then with the cost of life-long ART, and finally with the high cost of end-of-life care once limited treatment options are exhausted. One of the benefits of initiating patients on ART at higher CD4 counts could be avoiding the first of these costs. In the absence of sufficient drug options to avoid the third, terminal cost, and in a situation of decreasing international funding for ART programmes in low- and middle-income countries, avoiding the depletion of patients’ CD4 cells and the associated high likelihood of expensive inpatient care is one of the few options available to national ART programmes to reduce the costs of HIV care.

Table 2B.

Hospitalisation rates and cost by current CD4 cell count in patients before and after ART initiation after removing events in patients initiating ART at CD4 cell counts > 200 mm3

| CD4 cell count stratum | Total patient years (%) | Number of hospitalisations | Hospitalisation rate per 100 patient years (95% CI) | Mean length of stay [days] (95% CI) | Mean cost per stay [2009 USD] (95% CI) | Mean inpatient cost per patient year in cohort [2009 USD] (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Both sites

| ||||||

|

Pre-ART

| ||||||

| ≤100 cells/mm3 | 602.8 (8.6) | 60 | 10.0 (7.6–12.8) | 10.4 (7.4–13.4) | 1,759 (1,254–2,263) | 176 (95–290) |

| 101–200 cells/mm3 | 1,233.9 (17.6) | 78 | 6.3 (5.0–7.9) | 8.6 (5.9–11.2) | 1,453 (988–1,919) | 92 (49–152) |

| 201–350 cells/mm3 | 2,275.6 (32.5) | 109 | 4.8 (3.9–5.8) | 8.7 (6.7–10.6) | 1,452 (1,126–1,778) | 70 (44–103) |

| >350 cells/mm3 | 2,889.5 (41.3) | 97 | 3.4 (2.7–4.1) | 7.8 (5.6–10.0) | 1,290 (934–1,645) | 44 (25–67) |

|

| ||||||

| All pre-ART patients | 7,001.7 | 344 | 4.9 (4.4–5.4) | 8.7 (7.5–9.9) | 1,460 (1,267–1,657) | 72 (56–89) |

|

| ||||||

|

On ART

| ||||||

| ≤100 cells/mm3 | 132.3 (5) | 27 | 20.4 (13.5–29.8) | 12.1 (6.6–17.5) | 2,042 (1,128–2,957) | 417 (152–881) |

| 101–200 cells/mm3 | 441.6 (18) | 41 | 9.3 (6.7–12.6) | 14.0 (8.3–19.7) | 2,343 (1,387–3,300) | 218 (93–416) |

| 201–350 cells/mm3 | 945.2 (40) | 70 | 7.4 (5.8–9.4) | 9.6 (7.6–11.6) | 1,611 (1,279–1,943) | 119 (74–183) |

| >350 cells/mm3 | 910.3 (37) | 35 | 3.8 (2.7–5.3) | 6.0 (4.4–7.6) | 1,006 (728–1,284) | 39 (20–68) |

|

| ||||||

| All ART patients | 2,429.5 | 173 | 7.1 (6.2–8.2) | 10.3 (8.5–12.1) | 1,730 (1,427–2,032) | 123 (88–167) |

Acknowledgments

Source of Support: Funding for this study was provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under an award to Boston University (674-A-00-09-00018-00). Patient care was funded by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), through USAID (674-A-00-05-00003-00). MPF was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) (K01AI083097). TM received research training funded by a Fogarty International Center grant (U2RTW007370/3). NM is partially funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01HL090312). The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NIH, NIAID, USAID, PEPFAR, the University of the Witwatersrand, Boston University, or Johns Hopkins University.

GMR and ATB designed the study, analysed and interpreted data and wrote the first draft of the paper. MPF and SR contributed to data analysis and interpretation. TM and NT contributed to data acquisition and analysis. LM contributed to data acquisition and interpretation. NM helped design the study and contributed to data interpretation. All authors helped draft and revise the article. We thank the patients attending the study clinics for the readiness to share their data.

Footnotes

Meetings at which parts of the data were presented: 15th International Workshop on HIV Observational Databases 2011, Prague, 24 March 2011 (Abstract no. 15_29) (closed meeting without publication)

Potential Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Beck EJ, Mandalia S, Griffith R, et al. Use and cost of hospital and community service provision for children with HIV infection at an English HIV referral centre. Pharmacoeconomics. 2000;17:53–69. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200017010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baum SE, Morris JT, Gibbons RV, et al. Reduction in human immunodeficiency virus patient hospitalizations and nontraumatic mortality after adoption of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Military Medicine. 1999;164:609–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mouton Y, Alfandari S, Valette M, et al. Impact of protease inhibitors on AIDS-defining events and hospitalizations in 10 French AIDS reference centres. Federation National des Centres de Lutte contre le SIDA. AIDS. 1997;11:F101–5. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199712000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krentz HB, Auld MC, Gill MJ. The high cost of medical care for patients who present late (CD4 <200 cells/microL) with HIV infection. HIV Med. 2004;5:93–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2004.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nykamp D, Barnett CW, Lago M, et al. Cost of medication therapy in ambulatory HIV-infected patients. Ann Pharmacother. 1997;31:303–7. doi: 10.1177/106002809703100306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krentz HB, Auld MC, Gill MJ. The changing direct costs of medical care for patients with HIV/AIDS, 1995–2001. CMAJ. 2003;169:106–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garattini L, Tediosi F, Di Cintio E, et al. Resource utilization and hospital cost of HIV/AIDS care in Italy in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Care. 2001;13:733–41. doi: 10.1080/09540120120076896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stoll M, Claes C, Schulte E, Graf von der Schulenburg JM, Schmidt RE. Direct costs for the treatment of HIV-infection in a German cohort after the introduction of HAART. Eur J Med Res. 2002;7:463–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kyriopoulos JE, Geitona MA, Paparizos VA, et al. The impact of new antiretroic therapeutic schemes on the cost for AIDS treatment in Greece. J Med Syst. 2001;25:73–80. doi: 10.1023/a:1005640500643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sendi PP, Craig BA, Meier G, Pfluger D, Gafni A, Opravil M, et al. Cost effectiveness of highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 1999;13:1115–22. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199906180-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freedberg KA, Losina E, Weinstein MC, et al. The cost effectiveness of combination antiretroviral therapy for HIV disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:824–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schackman BR, Goldie SJ, Weinstein MC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of earlier initiation of antiretroviral therapy for uninsured HIV-infected adults. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1456–63. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.9.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck E, Mandalia S, Gaudreault M, et al. The cost-effectiveness of highly active antiretroviral therapy, Canada 1991–2001. AIDS. 2004;18:2411–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miners A, Sabin C, Trueman P, et al. Assessing the cost-effectiveness of highly active antiretroviral therapy for adults with HIV in England. HIV Medicine. 2001;2:52–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1293.2001.00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Pen C, Rozenbaum W, Downs A, et al. Une analyse cout-efficacité du changement des schémas thérapeutiques dans le VIH depuis 1996. Therapie. 2002;57:27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kowalik E, Jakubczyk M, Niewada M, et al. The cost-effectiveness of antiretroviral regimens containing protease inhibitors (PIS) or nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI) in the treatment of HIV-infected individuals in Poland [abstract] Value in Health. 2002;5:569. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lacey L, Youle M, Trueman PM, et al. A prospective evaluation of the cost effectiveness of adding lamivudine to zidovudine-containing antiretroviral treatment regimens in HIV infection. European perspective. Pharmacoeconomics. 1999;15(Suppl 1):39–53. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199915001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinto JL, Lopez Lavid C, Badia X, et al. Análisis coste-efectividad del tratamiento antirretroviral de gran actividad en pacientes infectados por el VIH asintomáticos. Med Clin (Barc) 2000;114(Suppl 3):62–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Long L, Fox M, Rosen S. Cost of hospitalization for those presenting at an HIV treatment center in South Africa [THPE0859]. Presented at: XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010; Vienna. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith de Cherif TK, Schoeman JH, Cleary S, et al. Early severe morbidity and resource utilization in South African adults on antiretroviral therapy. BMC Inf Dis. 2009;9:205. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murdoch DM, Venter WD, Feldman C, et al. Incidence and risk factors for the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV patients in South Africa: a prospective study. AIDS. 2008;22:601–10. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f4a607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leisegang R, Cleary S, Hislop M, et al. Early and late direct costs in a Southern African antiretroviral treatment programme: A retrospective cohort analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6(12):e1000189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stearns BK, Evans DK, Lutung P, et al. Primary estimates of the costs of ART care at 5 AHF clinics in sub-Saharan Africa [MOPE0706]. Presented at: XVIIth International AIDS Conference; 2008; Mexico City. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harling G, Wood R. The evolving cost of HIV in South Africa. JAIDS. 2007;45:348–54. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180691115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marseille E, Kahn JG, Pietter C, et al. The Cost-Effectiveness of Home-Based Provision of Antiretroviral Therapy in Rural Uganda. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2009;7(4):229–243. doi: 10.2165/11318740-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cleary S, McIntyre D, Boulle A. The cost-effectiveness of antiretroviral treatment. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation. 2006;4:20. doi: 10.1186/1478-7547-4-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas LS, Manning A, Holmes CB, et al. Comparative Costs of Inpatient Care for HIV-Infected and Uninfected Children and Adults in Soweto, South Africa. JAIDS. 2007;46:410–6. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318156ec90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martinson N, Mohapi L, Bakos D, et al. Costs of providing care for HIV-infected adults in an urban HIV clinic in Soweto, South Africa. JAIDS. 2009;50:327–30. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181958546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Long L, Rosen S, Sanne I. Stable outcomes and costs in South African patients’ second year on antiretroviral treatment [abstract]. Presented at: International AIDS Economics Network Symposium; 2008; Cuernavaca. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosen S, Long L, Sanne I. The outcomes and outpatient costs of different models of antiretroviral treatment delivery in South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:1005–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chhagan V, Luiz J, Mohapi L, et al. The socioeconomic impact of antiretroviral treatment on individuals in Soweto, South Africa. Health Sociol Rev. 2008;17:95–105. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Golub J, Pronyk P, Mohapi L, Thsabangu N, Moshabela M, Struthers H, et al. Isoniazide preventive therapy, HAART and tuberculosis risk in HIV-infected adults in South Africa: a prospective cohort. AIDS. 2009;23:631–6. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328327964f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanrahan CF, Golub JE, Mohapi L, et al. Body mass index and risk of tuberculosis and death. AIDS. 2010;24:1501–8. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833a2a4a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Department of Health, Republic of South Africa. National Antiretroviral Treatment Guidelines. Pretoria: Jacana Publishers; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization. Towards universal access: scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector. Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schafer JL. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 37.The District Health Barometer 2008/09. Available at: www.hst.org.za/publications/district-health-barometer-200809.

- 38.National Department of Health. National Indicator Dataset for South Africa. Pretoria: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Havlir DV, Getahun H, Sanne I, et al. Opportunities and Challenges for HIV Care in Overlapping HIV and TB Epidemics. JAMA. 2008;300:423–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meyer-Rath G, Pillay Y, Blecher M, et al. Total cost and potential cost savings of the national antiretroviral treatment (ART) programme in South Africa 2010 to 2017 [WEAE0201]. Presented at: XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010; Vienna. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meyer-Rath G, Pillay Y, Blecher M, et al. The impact of a new reference price list mechanism for drugs on the total cost of the national antiretroviral treatment programme in South Africa 2011 to 2017 [621]. Presented at: South African AIDS Conference; 2011; Durban. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meintjes G, Rabie H, Wilkinson RJ, et al. Tuberculosis-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome and unmasking of tuberculosis by antiretroviral therapy. Clin Chest Med. 2009;30:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]