Abstract

The disruptive behavior disorders are among the most prevalent youth psychiatric disorders, and they predict numerous problematic outcomes in adulthood. This study examined multiple domains of risk during early childhood and early adolescence as longitudinal predictors of disruptive behavior disorder diagnoses among adolescent males. Early adolescent risks in the domains of sociodemographic factors, the caregiving context, and youth attributes were examined as mediators of associations between early childhood risks and disruptive behavior disorder diagnoses. Participants were 309 males from a longitudinal study of low-income mothers and their sons. Caregiving and youth risk during early adolescence each predicted the likelihood of receiving a disruptive behavior disorder diagnosis. Furthermore, sociodemographic and caregiving risk during early childhood were indirectly associated with disruptive behavior disorder diagnoses via their association with early adolescent risk. The findings suggest that preventive interventions targeting risk across domains may reduce the prevalence of disruptive behavior disorders.

Keywords: Risk factors, disruptive behavior disorders, adolescence, parenting, longitudinal

Youth diagnosed with disruptive behavior disorders (DBDs), including conduct disorder (CD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), frequently go on to face serious challenges across several important life domains including family functioning, mental health, education, and employment [1]. For example, CD diagnoses were associated with high school dropout in the National Comorbidity Survey [2]. Also, adolescent CD and ODD were the only youth disorders that predicted every adult mental disorder that was assessed at age 26 in the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study [3]. Given the wide range of negative outcomes associated with youth DBDs, identifying and remediating risks for CD and ODD should be a high priority for developmental scientists and prevention researchers.

Risk factors for disruptive behaviors include sociodemographic characteristics, problems within the caregiving context, and child attributes [4], and risk within each of these domains can be reliably identified in early childhood [5, 6]. When information is available on numerous risk factors, one approach is to tabulate cumulative risk indexes and compare the accumulation of risk across domains [7, 8]. The accumulation of risk is associated with multiple negative outcomes ranging from lower intellectual development and achievement to multiple types of problem behavior [9-11]. However, the accumulation of risk early in life has not been prospectively examined as a precursor to psychiatric diagnosis during adolescence. Accordingly, the present study examined multiple domains of risk salient for the development of DBDs, including sociodemographic factors, the caregiving context, and child attributes, during early childhood as predictors of adolescent DBDs. Furthermore, the long-term nature of the current study allowed us to investigate whether the accumulation of risk within the same domains during early adolescence accounted for indirect associations between risk during early childhood and DBD diagnoses later in adolescence.

Risk Factors for Disruptive Behavior Disorders

Child attributes such as difficult temperament, aspects of the caregiving context (e.g., harsh parenting), and sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., neighborhood deprivation) are several of the most consistently supported risk factors for disruptive behavior problems [4, 12-14]. Longitudinal studies have generally examined risk factors associated with continuous indictors of disruptive behavior (e.g., conduct problems, externalizing behaviors). Fewer studies have investigated child and family risk factors as predictors of DBD diagnoses.

The small body of longitudinal research predicting DBD diagnoses generally shows that a broad array of risk factors predicts DBDs. For example, low family socioeconomic status, parental substance abuse, and child oppositional behaviors predicted CD diagnoses in a sample of clinically-referred boys who were followed from middle childhood into adolescence [15]. Similarly, in the Caring for Children in the Community Study, youth in a high risk latent class characterized by parental mental illness, parental criminality, parent-child conflict, and inter-parental conflict had the highest rates of DBD diagnoses (including CD, ODD, and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder [ADHD]). However, the authors of this analysis aptly noted that the risk factors and diagnoses were assessed concurrently [16]. Studies have yet to examine a wide array of risk factors from the first few years of life as predictors of DBD diagnoses in adolescence. Although risk factors for DBD diagnoses and predictors of continuous measures of conduct problems are similar [4], investigating precursors of clinically-elevated levels of disruptive behaviors is important because DBD diagnoses are especially predictive of poor adjustment later in adolescence and into adulthood [2, 3]. Moreover, examining multiple risk domains in a single analysis permits consideration of the relative impact of each of these domains on later risk for DBDs which is critical to informing early prevention and intervention.

Cumulative Risk Approaches

When examining a broad array of risk factors that may be associated with problem behaviors, one approach is to create a cumulative risk index. Cumulative risk research consistently shows that the presence of a single risk rarely predicts problematic outcomes, whereas the accumulation of multiple risks is especially problematic [11, 17]. For example, an analysis of the 1970 British Cohort Study demonstrated links between an early childhood cumulative risk index that included a broad range of factors such as single parenthood, large family size, and children's poor visual-motor skills and later conduct problems and criminal convictions [18]. Even though examining individual risk factors as separate or additive predictors of outcomes is sometimes more informative [19], cumulative risk models often provide the most parsimonious approach when investigating a large number of risks across domains within a longitudinal analysis [10, 20].

A related approach is to create multiple risk indexes that each capture the level of risk within a specific domain. For example, Deater-Deckard and colleagues [8] assessed risk within child, sociocultural, parenting, and peer domains and showed that cumulative risk within each domain predicted externalizing problems during middle childhood. It is likely that facing multiple risks across multiple domains would be especially predictive of later clinically-elevated psychopathology. Thus, the present study utilized a cumulative risk approach to investigate risk during early childhood within three domains that are frequently associated with conduct problems and DBD diagnoses—sociodemographic characteristics, the caregiving context, and child attributes. Sociodemographic characteristics linked to conduct problems include maternal age at first birth, single parenthood, and household overcrowding, and these factors are often the focus of cumulative risk research [21]. Important aspects of the early family caregiving context that lead to later disruptive behaviors include rejecting parenting and harsh discipline as well as low levels of sensitivity and nurturance [21, 22]. Finally, child attributes early in life including fearlessness and difficulty with emotional-self regulation also play an important role in the development of serious behavior problems [23, 24]. We hypothesized that the accumulation of risk during early childhood in each of these domains would predict the subsequent development of DBDs.

Early and Later Risk Across Domains

The findings of Murray and colleagues [18], reviewed above, suggest that the accumulation of risk factors early in life may be especially predictive of later disruptive behaviors. However, Murray and colleagues also noted that future research should “identify the most important moderators and mediators of early risk in determining antisocial outcomes” (p. 1206). Fitting with this research direction, recent empirical evidence shows that early cumulative risk is associated with negative outcomes via contextual mediators. For example, in recent shorter-term longitudinal studies lower levels of parenting quality accounted for the indirect association between cumulative risk early in life and young children's maladjustment [21, 25]. On the other hand, another longitudinal study showed that cumulative risk in early childhood directly predicted behavior problems in adolescence even after accounting for cumulative risk in middle childhood [9]. To help clarify the existing findings, we examined whether risk during early adolescence mediated associations between the accumulation of risks across multiple domains during early childhood and subsequent DBD diagnoses. Our study was unique in that we focused on DBD diagnoses and multiple domains of risk in early childhood and early adolescence. This approach allowed us to examine specific theory-based indirect paths from risk early in life to subsequent DBD diagnoses.

Risk indexes tapping the same domains (i.e., sociodemographic factors, the caregiving context, and youth attributes) during early adolescence may be an especially important set of potential mediators to consider in longitudinal analyses predicting DBDs during mid-adolescence. Within the domain of youth attributes, cognitive functioning, social information processing patterns, and dispositional traits play important roles in predicting disruptive behavior [26-28]. Existing theory and research suggest that these youth attributes may account for the association between risks encountered early in life and involvement in subsequent disruptive behaviors [29]. In addition, numerous aspects of the caregiving context, including parental knowledge of the young adolescent's whereabouts, parent-youth conflict, and physical discipline are especially salient predictors of disruptive behavior during the early adolescent developmental period [30-32]. Existing research indicates that aberrant caregiving during adolescence mediates the assocation between earlier risk and subsequent disruptive behaviors [33]. In terms of sociodemographic factors, it is important to determine whether consistency in sociodemographic risk from early childhood to early adolescence accounts for an elevated risk for later disruptive behavior disorders.

Extensive multi-method data were available for the present analyses to create risk indexes in early adolescence. Fitting with the cumulative risk perspective, highly elevated risk within a domain was hypothesized to predict the presence of a DBD diagnosis. For example, no risks or a low number of risks within the domain of youth attributes during early adolescence (e.g., high levels of “daring” dispositional traits paired with high levels of prosociality, moderate to high intelligence, and low negative emotionality) were expected to predict a low likelihood of receiving a DBD diagnosis relative to the accumulation of risk (e.g., high levels of “daring” paired with low intelligence and low prosociality). Furthermore, it was expected that high levels of risk within domains during early adolescence would mediate associations between risk in each of the early childhood domains and later DBD diagnoses. Continuity in risk within domains may be especially likely to provide evidence of statistical mediation. For example, early adolescent caregiving risk may be especially likely to mediate the association between early childhood caregiving risk and DBD diagnoses.

Goals of the Present Study

The present study focused on a sample of at-risk males and their families who were initially assessed during the toddler period and followed through adolescence. Sons and their mothers were the focus of the study due to the higher prevalence of DBDs among males [34, 35] and because mothers are frequently the sole caregiver in at-risk, low-income families [36]. Moreover, we focused on low-income families because youth from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds are at elevated risk for DBDs [15]. We considered multiple domains of risk during early childhood and early adolescence as predictors of adolescent DBDs. Components of each domain's risk index were selected based on theory and empirical evidence linking the risk factors to serious conduct problems and DBD diagnoses. For example, young maternal age at first birth and low parental knowledge were selected as components of the early childhood sociodemographic and early adolescent caregiving risk indexes, respectively, based on existing empirical evidence linking these individual risk factors to serious behavior problems [30, 37].

We examined whether risk in three early childhood domains (sociodemographic characteristics, the caregiving context, and child attributes) independently predicted DBD diagnoses over one decade later. We also investigated whether early risk factors were indirect predictors of adolescent DBDs via their association with elevated risk during early adolescence. Given that the early adolescent risks were more proximal to the assessment of DBDs, we hypothesized that risk during early adolescence would mediate the association between risk during early childhood and DBD diagnoses during adolescence. Furthermore, because CD and ODD are the two disorders included in the disruptive behavior disorders category [38], we combined diagnoses of CD and ODD for our primary analyses predicting DBD diagnostic status. However, we also conducted follow-up analyses to investigate whether the same direct and indirect associations would be found when predicting CD and ODD diagnoses in separate analyses.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study were enrolled in the Pitt Mother and Child Project (PMCP), an ongoing longitudinal study of low-income families [6]. In 1991 and 1992, 310 infant boys and their mothers were recruited from Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Nutrition Supplement Clinics in Allegheny County, PA when the boys were between 6 and 17 months old. The research protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh's Institutional Review Board, and participating primary caregivers provided informed consent.

At the time of recruitment, 53% of the target children in the sample were European-American, 36% were African-American, 5% were biracial, and 6% were of other races. Two-thirds of mothers in the sample had 12 years of education or less. The mean per capita income was $241 per month, and the mean Hollingshead SES score at the study's outset was 24.5, indicative of a impoverished to working class sample. Retention rates have generally been high throughout the study, with some data available on 89% of the sample at ages 10, 11, or 12, and data available for 89% of the sample at age 15 and 81% of the sample at age 17. The high retention rate can be attributed to a number of factors, including: reimbursing families for their participation, obtaining contact information for other family members and friends who would know the family's whereabouts in the event that the family moved, sending birthday cards and newsletters to maintain rapport and current address information, and employing a research assistant who has led participant contact and scheduling efforts for nearly the entire duration of the PMCP. In addition, the Pittsburgh area has a relatively low rate of residential mobility compared to other metropolitan areas in the United States. The present study included the 309 boys with data available for at least one variable used in the analyses.

Procedure

Target children and their mothers were seen for two- to three-hour visits at ages 1.5, 2, 3.5, 5, 5.5, 6, 8, 10, 11, 12, 15, and 17 years old. Data were collected in the laboratory (ages 1.5, 2, 3.5, 6, 11) and/or at home (ages 2, 5, 5.5, 8, 10, 12, 15, 17). At all points, children were assessed with their “primary caregiver,” who in most cases were their mothers. Participating families were reimbursed for their time at each assessment.

For the present study, primary caregiver reports and observations during the early childhood assessment waves (1.5, 2, and 3.5 years) provided data for the early childhood risk indexes. In accord with recent definitions of the onset of adolescence [39], primary caregiver and youth reports from assessments at ages 10, 11, and 12 years provided data for the early adolescent risk indexes. Structured interviews during the age 15 and 17 assessment waves were used to determine the presence or absence of a DBD diagnosis.

Measures

Early childhood externalizing problems

Externalizing problems during early childhood (ages 2 and 3.5 years) were included as a predictor of early adolescent risk and DBDs in the longitudinal models to account for stability in behavior problems. Externalizing problems were assessed with the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) for Ages 2-3 [40]. Externalizing raw scores at age 2 and age 3.5 were converted to z-scores, and we used the average of the z-scores in the analyses.

Cumulative risk indexes

All risk indexes were created by dichotomizing risk factors that have been associated with disruptive behavior problems. For each risk factor, families received a score of ‘1’ for each indicator if present or a score of ‘0’ if absent. For continuous measures, criteria were established so that that approximately 25% of the sample would meet criteria for each risk indicator, an approach that is in accordance with similar cumulative risk research [41].

A summary of the early childhood risk indexes is presented in Table 1. The early childhood sociodemographic risk index was generated from six indicators: (1) very low income, (2) low maternal education, (3) teen parent status, (4) household overcrowding, (5) single parenthood, and (6) neighborhood dangerousness. The early childhood caregiving risk index was generated from five indicators: (1) rejecting parenting, (2) low maternal nurturance, (3) inter-parental conflict, (4) harsh discipline attitudes, and (5) high levels of parenting hassles. The early childhood child attributes risk index was generated from five indicators, four of which were coded from observations of the child: (1) temperamental difficultness, (2) observed irritability, (3) fearlessness, (4) observed noncompliance, and (5) poor emotion regulation strategies. A summary of the early adolescent risk indexes is presented in Table 2. The early adolescence sociodemographic risk index was generated from five indicators: (1) very low income, (2) low maternal education, (3) household overcrowding, (4) single parenthood, and (5) neighborhood dangerousness. The early adolescence caregiving risk index included the following indicators: (1) low parental knowledge, (2) parent-child conflict, (3) inter-parental conflict, (4) parent-reported physical discipline, and (5) observed harsh parenting. The early adolescence youth attributes risk index included the following indicators: (1) low IQ, (2) high negative emotionality, (3) low prosociality, (4) high levels of “daring” traits, and (5) maladaptive social information processing.

Table 1.

Early Childhood Cumulative Risk Indicators, Sources, and Percentage Meeting Criteria

| Indicator | Criteria | Source and Child Age | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | |||

| Very low income | Bottom quartile for at least ½ timepoints | Demographic interview at 1.5, 2, and 3.5 years | 28.5 |

| Low maternal education | Less than high school degree | Demographic interview at 1.5 | 13.0 |

| Young maternal age at first birth | 18 or younger | Demographic interview at 1.5 | 27.9 |

| Overcrowding | More people than rooms or more than 3 children | Demographic interview at 1.5, 2, and 3.5 | 32.0 |

| Single parent | Single parent for at least ½ timepoints | Demographic interview at 1.5, 2, and 3.5 | 40.8 |

| Neighborhood dangerousness | Highest quartile on dangerousness items | Neighborhood questionnaire [32] at 2 | 25.8 |

| Caregiving | |||

| Rejecting parenting | Highest quartile based on global and molecular codes | Early Parenting Coding System [6] at 1.5 and 2 | 24.9 |

| Low nurturance | Bottom quartile on Responsivity and Acceptance scales | Home Observation for the Measurement of the Environment (HOME) [57] at 2 | 29.1 |

| Inter-parental conflict | Highest quartile | Conflict Tactics Scale [58] at 3.5 | 25.8 |

| Physical Discipline attitudes | Highest quartile | Adolescent Parenting Inventory [59] at 2 | 24.4 |

| Parenting Hassles | Highest quartile | Parenting daily hassles [60] at 1.5, 2, and 3.5 | 25.2 |

| Child Attributes | |||

| Parent-reported Difficultness | Highest quartile | Infant Characteristics Questionnaire [61] at 1.5 and 2 | 27.2 |

| Irritability | Highest quartile | Observation of stressful and non-stressful tasks [62] at 1.5 | 25.7 |

| Fearlessness | Lowest quartile on behavior inhibition | Observational gorilla task [6] at 2 | 25.1 |

| Poor regulation strategies | Highest quartile on focus on delay | Observational cookie task [24] at 3.5 | 31.5 |

| Noncompliance | Highest quartile | Observational clean-up task [62] at 1.5, 2, and 3.5 | 25.2 |

Table 2.

Early Adolescence Cumulative Risk Indicators, Sources, and Percentage Meeting Criteria

| Indicator | Criteria | Source and Child Age | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | |||

| Very low income | Bottom quartile for at least ½ timepoints | Demographic interview at 10, 11, and 12 years | 25.7 |

| Low maternal education | Less than high school degree | Demographic interview at 10 years | 9.1 |

| Overcrowding | More people than rooms or more than 3 children | Demographic interview at 10, 11, and 12 years | 26.9 |

| Single parent | Single parent for at least ½ timepoints | Demographic interview at 10, 11, and 12 years | 45.5 |

| Neighborhood dangerousness | Highest quartile on Dangerousness scale | Me and My Neighborhood [63] at 11 | 25.8 |

| Caregiving | |||

| Low parental knowledge | Lowest quartile | Interview with youth [63] at 12 years | 23.7 |

| Parent-child conflict | Lowest quartile | Adult-child relationship questionnaire [32] at 10, 11, and 12 | 25.0 |

| Inter-parental conflict | Highest quartile | Conflict Tactics Scale [57] at 10, 11, and 12 | 25.7 |

| Physical Discipline | Highest quartile | Interview with parent [31] at 10, 11, and 12 | 32.5 |

| Harsh Parenting | Highest quartile | 8 observed items from the Home Observation for the Measurement of the Environment (HOME) [56] at 10, 11, and 12 | 27.5 |

| Youth Attributes | |||

| Low intelligence | Lowest quartile | Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-III verbal and performance subscales [64], age 11 | 26.5 |

| Daring | Highest quartile | The Child and Adolescent Dispositions Scale (CADS) [27], age 12 | 25.6 |

| Negative emotionality | Highest quartile | CADS, age 12 | 25.1 |

| Prosociality | Lowest quartile | CADS, age 12 | 25.1 |

| Social information processing (SIP) | Highest quartile for hostile attribution and maladaptive response generation | SIP interview [65], age 10 and 11 | 25.4 |

Disruptive behavior disorders

During the age 15 and 17 home visits, primary caregivers and their sons were administered the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Aged Children (K-SADS) by interviewers who were trained research assistants and clinical psychology graduate students. The K-SADS is a well-established semi-structured interview developed at the University of Pittsburgh that assesses DSM-IV child psychiatric symptoms over the last year [42]. At each assessment, a trained interviewer privately interviewed the primary caregiver and then the adolescent about symptoms of both internalizing (i.e., depression) and externalizing diagnoses (i.e., CD) and made a clinical judgment about the presence or absence of each symptom. These interviewers participated in an intensive training program led by experts in the K-SADS at the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic of the University of Pittsburgh or were trained by doctoral-level clinical psychology students who had attended this training and had extensive experience with the K-SADS. All interviewers were observed multiple times by experienced examiners until they were deemed proficient at administering the interview. Every case in which a child approached or met diagnostic criteria was discussed at interviewing team meetings, which included the interviewers and the fourth author, who is a licensed clinical psychologist with over 20 years of experience using the K-SADS.

Based on DSM-IV diagnostic criteria, 26.1% (n = 69) of the 264 participants who completed the K-SADS interview met criteria for ODD and/or CD at age 15 and/or 17. The total included 48 youth (18.2%) who met criteria for ODD and 52 youth (19.7%) who met criteria for CD at age 15 and/or 17. As expected given the low-income background of the present sample, the percentage of males meeting criteria for these disorders was higher than recent estimates of the lifetime prevalence of CD (12%) and ODD (11.2%) among males in the United States [34, 35]. Furthermore, many youth had comorbid diagnoses, and these youth were not excluded from the present analyses. For example, 43.5% of youth who met criteria for a DBD also met criteria for ADHD at age 15 and/or 17. Youth and parents with clinically-elevated scores on the K-SADS or other clinically-oriented measures administered during the course of the PMCP received information on mental health services with sliding-scale fees to accommodate the needs of low-income families.

Analysis Plan

Analyses proceeded in several steps. First, descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were explored. Next, a longitudinal logistic path model was created to examine the three domains of early childhood risk as direct predictors of DBD diagnostic status (presence versus absence of an ODD and/or CD diagnosis during adolescence). Then, a second path model was created to examine longitudinal relations among early childhood risk domains, the early adolescent risk domains, and DBD diagnostic status. Models were examined with Mplus version 6.12 [43]. Because the outcome variable (DBD diagnostic status) was dichotomous, we used the Weighted Least Squares Means and Variances (WLSMV) estimator. The WLSMV estimator was the best choice for these analyses because it is appropriate for categorical outcomes and provides useful model fit indexes and indirect effects [44, 45].

Model fit was considered adequate if the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) values met established guidelines for good to fair fit (i.e., RMSEA < .06 and CFI > .95) [46]. All direct paths were also examined for statistical significance. Then, the hypothesized indirect paths were tested for statistical significance in Mplus. Finally, separate models were run predicting either CD or ODD diagnostic status to examine whether a similar pattern of findings emerged when predicting each DBD diagnosis in separate models. All path models controlled for externalizing problems during early childhood.

Results

Table 3 presents the means, standard deviations, and ranges for early externalizing problems and each risk index. For each risk index, we utilized a sum score reflecting the number of risk criteria met. All risk indexes were relatively normally distributed with minimal skew, which supports examining them as continuous variables in the path models. Furthermore, each risk index except the early childhood child attributes index had a range that included the minimum possible score of zero risks present through the maximum possible score of all risks (either five or six risks) present. None of the participants met criteria for all five risks for the early childhood child attributes index.

Table 3.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Range of Scores

| Variable | N | Range | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Childhood | ||||

| Externalizing Problems | 308 | -2.16 to 2.56 | -.02 | .90 |

| Sociodemographic Risk | 309 | 0 to 6 | 1.64 | 1.42 |

| Caregiving Risk | 297 | 0 to 5 | 1.26 | 1.20 |

| Child Risk | 294 | 0 to 4 | 1.24 | 1.03 |

| Early Adolescence | ||||

| Sociodemographic Risk | 268 | 0 to 5 | 1.29 | 1.11 |

| Caregiving Risk | 252 | 0 to 5 | 1.29 | 1.29 |

| Youth Risk | 215 | 0 to 5 | 1.25 | 1.11 |

Table 4 presents bivariate correlations. Correlations between the risk indexes ranged from non-significant to relatively strong in magnitude. Early externalizing problems were significantly and modestly correlated with all risk domains except sociodemographic risk during early adolescence and youth attributes during early adolescence. All predictors were correlated with DBD diagnostic status except for the correlations between each of the sociodemographic risk indexes and DBD diagnostic status; these bivariate correlations were marginally significant (p < .10).

Table 4.

Bivariate Correlations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Early Externalizing Problems | |||||||

| 2. Sociodemographic Risk (Early Childhood) | .19** | ||||||

| 3. Caregiving Risk (Early Childhood) | .33** | .32** | |||||

| 4. Child Risk (Early Childhood) | .25** | .05 | .13* | ||||

| 5. Sociodemographic Risk (Early Adolescence) | .09 | .56** | .23** | -.01 | |||

| 6. Caregiving Risk (Early Adolescence) | .32** | .20** | .41** | .17** | .31** | ||

| 7. Youth Risk (Early Adolescence) | .12a | .37** | .21** | .09 | .30** | .39** | |

| 8. DBD Diagnostic Status | .18** | .12a | .18** | .15* | .11a | .33** | 29** |

Note. DBD = Disruptive Behavior Disorders

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Path Models Predicting DBD Diagnostic Status

The initial path model (Model 1) was created to examine the risk domains during early childhood as predictors of DBD diagnostic status. This model included the three early childhood risk indexes and early childhood externalizing problems as direct predictors of the dichotomous DBD diagnosis variable. It did not include the early adolescent risk indexes. In Model 1, the child attributes risk index (β = .14; p < .10) and early childhood externalizing problems (β = .15; p < .10) were marginally significant predictors of DBD diagnoses in this multivariate model. The other early childhood risk indexes were non-significant predictors of DBD diagnostic status (p > .10).

Next, the early adolescent risk indexes were examined as mediators of the association between early childhood risk indexes and DBD diagnoses in adolescence (Model 2). Paths were included from each early childhood risk index and early childhood externalizing problems to each early adolescence risk index to test our hypothesis that each type of risk in early childhood would be uniquely associated with risk in early adolescence. Paths were also included from each early adolescence risk index to the dichotomous DBD variable to test our hypothesis that each early adolescence risk index would predict DBDs and serve as mediators of relations between the early childhood risk indexes and the presence of a DBD. Lastly, direct paths were included from each early childhood risk index and early childhood externalizing problems to DBD diagnostic status to examine whether early risk also directly predicted the likelihood of meeting criteria for a DBD.

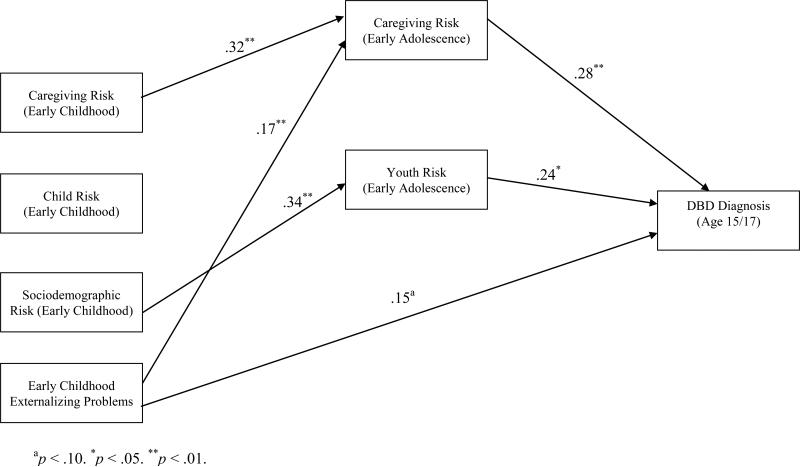

Because the path models described above (Models 1 and 2) contained all possible direct paths, they were fully saturated models with zero degrees of freedom, precluding the use of traditional fit indexes. In addition, several of the paths in Model 2 were not significant, including the three direct paths from early childhood risk indexes to adolescent DBD diagnostic status. Therefore, this model was revised by deleting the direct paths from the early childhood risk indexes to DBD diagnostic status. The direct path from sociodemographic risk during early adolescence to DBD diagnostic status was also non-significant. Therefore, the early adolescent sociodemographic risk variable was removed for the revised model. The revised model (Model 3) is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Model of the relations among early childhood risk, early adolescent risk, and disruptive behavior diagnoses.

Model 3 demonstrated excellent model fit, χ2 (3) = 2.02 (p > .05), RMSEA = .000, and CFI = 1.00. Based on the significant path coefficients (see Figure 1), Model 3 supported caregiving and youth risk during early adolescence as predictors of the presence of a DBD. In addition, the direct path from caregiving risk during early childhood to caregiving risk during early adolescence was statistically significant, as was the path from sociodemographic risk during early childhood to youth attributes during early adolescence. Predictors in the model explained 24% of the variance in DBD diagnoses.

Next, we evaluated the individual indirect effects of the early childhood variables on DBD diagnostic status. Sociodemographic risk during early childhood had a significant indirect relation with adolescent DBD diagnosis through risk in the domain of youth attributes during early adolescence (z = 2.15, p < .05). Furthermore, caregiving risk during early childhood was a significant indirect predictor of DBD diagnostic status, with caregiving risk during early adolescence accounting for this association (z = 2.69, p < .01). Last, the indirect path from early childhood externalizing problems to DBD diagnostic status via caregiving risk during early adolescence was statistically significant (z = 2.05, p < .05). Indirect effects were not supported for the child attributes risk index. Thus, Model 3 supported indirect relations between two of the early childhood risk indexes and DBD diagnoses.

Path Models Predicting CD or ODD Diagnostic Status

Finally, we examined the identical path model as presented in Model 3 (see Figure 1), but with either CD diagnostic status (Model 4) or ODD diagnostic status (Model 5) as the outcome. Model 4 demonstrated excellent model fit, χ2 (3) = 1.20 (p > .05), RMSEA = .000, and CFI = 1.00. Furthermore, the same paths that were significant in Model 3 were significant in Model 4. Also, the indirect effect involving pathways from caregiving risk during early childhood to caregiving risk during early adolescence and subsequent CD diagnostic status was statistically significant (z = 2.39, p < .05). The indirect pathway including sociodemographic risk during early childhood, youth risk during early adolescence, and CD diagnostic status was marginally significant (z = 1.92, p < .06).

Model 5, the path model with ODD diagnostic status as the outcome, demonstrated good model fit, χ2 (3) = 3.61 (p > .05), RMSEA = .026, and CFI = .997. All direct paths that were significant in Model 3 were significant in Model 5, except the path from youth risk during adolescence to ODD diagnostic status. This path was marginally significant in Model 5 (p < .06). The indirect effect involving pathways from caregiving risk during early childhood to caregiving risk during early adolescence and subsequent ODD diagnostic status was statistically significant (z = 3.21, p < .05). However, as in Model 4, the indirect pathway including sociodemographic risk during early childhood, youth risk during early adolescence, and ODD diagnostic status was marginally significant (z = 1.71, p < .10).

Discussion

This study provided support for multiple domains of risk as predictors of DBDs in adolescence, and predictors explained nearly one quarter of the variance in youth DBDs. The findings suggest that both the caregiving context and youth attributes during early adolescence play an important direct role in increasing risk for DBDs. Although the caregiving context and youth attributes have both received extensive support as predictors of DBDs in previous research [4], the present study was unique because it included a comprehensive index of risk for each domain. These multi-method risk indexes included aspects of the caregiving context such as low parental knowledge and youth attributes such as low IQ scores that have been shown to predict DBDs when investigated as individual risk factors.

Importantly, findings were largely consistent in separate models that examined CD diagnostic status or ODD diagnostic status as the outcome, thus supporting our decision to aggregate CD and ODD diagnoses for the primary analyses. Nonetheless, subtle yet potentially important differences existed across models. Most notably, risk in the domain of youth attributes during early adolescence predicted diagnostic status in the overall DBD model and the CD model, but this predictor was marginally significant in the model predicting ODD diagnostic status. This pattern of findings may reflect the youth attributes index's emphasis on adolescent dispositions and cognitive factors that have been theorized to be especially predictive of serious conduct problems and CD diagnoses rather than ODD [47].

Indirect Pathways

A number of theoretically-informative indirect pathways from risks during early childhood to DBD diagnostic status were supported. Broadly, sociodemographic risk, caregiving risk, and externalizing problems during early childhood were each indirectly associated with DBD diagnoses during adolescence via specific risk domains during early adolescence. More specifically, three key pathways from early childhood risk to DBD diagnoses in adolescence received support. First, sociodemographic risk during early childhood was associated with DBDs via increased risk in the domain of youth attributes during adolescence. This finding fits with the extensive body of literature linking cumulative risk to child behavioral, cognitive, and social maladjustment [10, 11]. Importantly, sociodemographic risk during early adolescence did not directly predict DBD diagnostic status. Therefore, the early ecological context may be especially important to consider when developing interventions to promote healthy youth functioning as a means to prevent later DBDs.

The second indirect pathway involved continuity in caregiving risk from early childhood to early adolescence in risk for DBDs; caregiving risk in early adolescence accounted for the indirect pathway from caregiving risk in early childhood and later DBD diagnoses. Indicators of problematic caregiving in early childhood (e.g., harsh parenting) and early adolescence (e.g., low parental knowledge) are key aspects of cascade models leading to delinquency in adolescence [33]. The present findings provide further evidence for the importance of caregiving risk at these developmental stages, but it is also important to note that our measurement approach may have contributed somewhat to the magnitude of this indirect pathway. Specifically, parent reports were utilized for several components of each caregiving risk index, and for one element of the risk domain (inter-parental conflict) the same measure was utilized across development.

The third indirect pathway included early externalizing problems and caregiving risk during early adolescence. This pathway supports early-emerging behavior problems as key precursors to later psychopathology and suggests that impairments in the family caregiving context brought about by these early-emerging problems have an important role in linking early behavior problems to subsequent diagnoses. The pathway also provides support for child-effects models [48] whereby child behavior plays a role in influencing parenting and the family context. Finding support for this pathway in the present study is also notable because these child effects emerged while accounting for the robust continuity in caregiving risk.

Other indirect pathways were not supported in the model. Most notably, continuity in risk within the domain of child attributes did not receive support as an indirect pathway leading to DBDs. One possible explanation may be due to the early childhood index's heavy use of observational measures of child behaviors. In addition, there was relatively limited similarity between many of the early childhood attributes (e.g., noncompliance) and the attributes assessed during early adolescence (e.g., IQ) when compared to the measures used for the caregiving indexes. Though our multi-method approach assessing developmentally-salient youth characteristics was a strength of the study, this discontinuity in risk factors may have attenuated the relationship between these two indexes. Another indirect pathway that did not receive support was the pathway from sociodemographic risk to DBDs via risk in the caregiving context during early adolescence. This null finding is notable because previous research demonstrated indirect links between cumulative sociodemographic risk and externalizing problems during early childhood that were fully mediated by parenting [21].

The present findings also differ from previous research where early cumulative risk was a direct predictor of later behavior problems even while accounting for cumulative risk during middle childhood [9]. Because the present study does not provide support for cumulative risk during early childhood as a direct predictor of later behavior problems in multivariate models, it is important to consider important methodological differences between the present study and previous findings. First, the present study focused on clinical diagnoses of DBDs as the outcome rather than rating scale measures of conduct problems. Using DBD diagnostic status as the outcome may be less statistically powerful but more clinically-informative. Second, risk in early adolescence was investigated as a mediator of the association between early risk and later DBDs, allowing us to examine more proximal risk-related predictors of DBD diagnostic status. Lastly, when examining cumulative risk in early childhood and early adolescence, we computed multiple indexes to evaluate separate domains of risk. Each of these aspects of the present study likely contributes to early childhood cumulative risk's role as an indirect predictor of later problems rather than a direct predictor. Furthermore, it is important to note that DBD diagnoses were made over one decade after the early childhood variables were assessed, which set an especially high standard for uncovering direct associations between early risk and later DBDs, especially when controlling for risk during early adolescence.

Study Limitations

An important limitation is that this longitudinal study focused exclusively on males who were recruited from WIC nutrition supplement centers serving low-income families in a single urban area in the United States. Although the prevalence of DBDs is higher among males than females [34, 35], understanding risk for DBDs among females has received increased attention [49]. It will be important for future longitudinal research to consider whether specific domains and pathways are more salient for males’ versus females’ risk for DBDs. Furthermore, an adverse sociodemographic context is an established precursor to serious disruptive behaviors [33], but future research should examine whether the current findings generalize to more diverse sociodemographic and geographic contexts.

In addition, the study focused on cumulative risk indexes rather than individual risk factors. Although cumulative risk indexes offer a powerful and parsimonious approach when aggregating data from a longitudinal study [10, 20], investigating individual risk factors may have provided a more nuanced picture of risk for DBDs. Furthermore, the study did not include all possible risk factors. For example, physiological, neurobiological, and genetic factors have received increased attention as predictors of disruptive behavior [50-53], but measures tapping these domains were not available for the early childhood and early adolescent waves of the present study. Moreover, these unmeasured factors (e.g., genetic variation) may underlie some of these findings. For example, child attributes, caregiving and DBDs could all be correlated via shared heritability. As this was an observational study focused on the development of DBDs, rather than their treatment, and data on behavioral treatment and/or medication usage were not routinely collected, we were unable to account for the contribution of these factors on later development of DBD diagnoses.

Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice

The current study supports the idea that early risks, particularly in the sociodemographic and caregiving domains, may set in motion a cascade of problems during childhood and adolescence that increase the likelihood of DBD diagnoses among adolescent males. Therefore, reducing risks in these domains early in life is a worthy goal for prevention research. Fitting with this perspective, a recent evaluation of the multi-site Fast Track program showed reduced prevalence of CD diagnoses, but only among participants with the highest level of initial risk [54].

The importance of both sociodemographic risks and the caregiving context also fits with the goals of the Family Check-Up (FCU), a family-focused program to prevent conduct problems and substance use. A recent multi-site trial of the FCU for parents of toddlers showed reductions in child conduct problems by targeting multiple aspects of the family context, including positive parenting and maternal depression [55]. Future evaluations of prevention programs such as the FCU or Fast Track should examine reductions in levels of sociodemographic and caregiving risk early in life as program outcomes because they may portend later improvements in youths’ and caregivers’ functioning and decreased likelihood of meeting criteria for a DBD diagnosis in adolescence. Examining reductions in risk within or across domains using a multi-domain cumulative risk approach could be a particularly novel and informative way to assess the impact of effective prevention programs. Furthermore, practitioners working with young children and their families may want to consider the family's socioeconomic concerns and potential remedies to these concerns (e.g., obtaining housing in a safer community) [56] in addition to utilizing traditional treatment approaches that target parenting practices and child behavior problems.

Summary

This study examined multiple domains of risk during early childhood and early adolescence as longitudinal predictors of DBD diagnoses among adolescent males. Early adolescent risks were examined as mediators of associations between early childhood risks and DBD diagnoses in a moderately large sample of males from an ongoing 15-year study of low-income mothers and their sons. Risk indexes were created from multi-method assessments during early childhood and early adolescence, and DBDs were assessed via structured interview in mid-adolescence. Caregiving and youth risk during early adolescence each predicted the likelihood of receiving a DBD diagnosis. In addition, sociodemographic and caregiving risk during early childhood were indirectly associated with DBD diagnoses via their association with early adolescent risk. The findings suggest that preventive interventions that target risk across domains beginning early in life are likely to help reduce the prevalence of DBDs.

References

- 1.Jaffee SR, Belsky J, Harrington H, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. When parents have a history of conduct disorder: How is the caregiving environment affected? J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115:309–319. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Foster CL, Saunders WB, Stang PE. Social consequences of psychiatric disorders, I: Educational attainment. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1026–1032. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Poulton R. Prior juvenile diagosis in adults with mental disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:709–717. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loeber R, Burke JD, Pardini DA. Development and etiology of disruptive and delinquent behavior. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2009;5:291–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw DS, Gross H. What have we learned about early childhood and the development of delinquency. In: Liberman A, editor. The long view of crime. A synthesis of longitudinal research Springer; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaw DS, Gilliom M, Ingoldsby EM, Nagin DN. Trajectories leading to school-age conduct problems. Dev Psychol. 2003;39:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atzaba-Poria N, Pike A, Deater-Deckard K. Do risk factors for problem behaviour act in a cumulative manner? An examination of ethnic minority and majority children through an ecological perspective. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:707–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Multiple risk factors in the development of externalizing behavior problems: Group and individual differences. Dev Psychopathol. 1998;10:469–493. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Appleyard K, Egeland B, van Dulmen M, Sroufe LA. When more is not better: The role of cumulative risk in child behavior outcomes. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46:235–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sameroff AJ, Seifer R, Baldwin A, Baldwin C. Stability of intelligence from preschool to adolescence: The influence of social and family risk factors. Child Dev. 1993;64:80–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rutter M. Protective factors in children's responses to disadvantage. In: Kent M, Rolf J, editors. Primary prevention in psychopathology. University Press of New England; Hanover, NH: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell SB, Shaw DS, Gilliom M. Early externalizing behavior problems: Toddlers and preschoolers at risk for later maladjustment. Dev Psychopathol. 2000;12:467–488. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frick PJ, Morris AS. Temperament and developmental pathways to conduct problems. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2004;33:54–68. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barker ED, Maughan B. Differentiating early-onset persistent versus childhood-limited conduct problem youth. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:900–908. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loeber R, Green SM, Keenan K, Lahey BB. Which boys will fare worse? Early predictors of the onset of conduct disorder in a six-year longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:499–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Copeland W, Shanahan L, Costello EJ, Angold A. Configurations of common childhood psychosocial risk factors. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50:451–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02005.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sameroff AJ. Environmental risk factors in infancy. Pediatrics. 1998;102:1287–1292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray J, Irving B, Farrington DP, Colman I, Bloxsam CAJ. Very early predictors of conduct problems and crime: Results from a national cohort study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51:1198–1207. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aro T, Poikkeus A, Eklund K, Tolvanen A, Laasko M, Viholainen H, et al. Effects of multidomain risk accumulation on cognitive, academic, and behavioral outcomes. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2009;38:883–898. doi: 10.1080/15374410903258942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ackerman BP, Brown ED, Izard CE. The relations between persistent poverty and contextual risk and children's behavior in elementary school. Dev Psychol. 2004;40:367–377. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trentacosta CJ, Hyde LW, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Gardner F, Wilson M. The relations among cumulative risk, parenting, and behavior problems during early childhood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49:1211–1219. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trentacosta CJ, Shaw DS. Maternal predictors of rejecting parenting and early adolescent antisocial behavior. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2008;36:247–259. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9174-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barker ED, Oliver BR, Viding E, Salekin RT, Maughan B. The impact of prenatal maternal risk, fearless temperament and early parenting on adolescent callous-unemotional traits: a 14-year longitudinal investigation. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52:878–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trentacosta CJ, Shaw DS. Emotional self-regulation, peer rejection, and antisocial behavior: Developmental associations from early childhood to early adolescence. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2009;30:356–365. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burchinal M, Vernon-Feagans L, Cox M. Cumulative social risk, parenting, and infant development in rural low-income communities. Parent Sci Pract. 2008;8:41–69. doi: 10.1080/15295190701830672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dodge KA, Pettit GS. A biopsychosocial model of the development of chronic conduct problems in adolescents. Dev Psychol. 2003;39:349–371. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lahey BB, Rathouz PJ, Applegate B, Tackett JL, Waldman ID. Psychometric characteristics of a self-report veresion of the Child and Adolescent Dispositions Scale. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2010;39:351–361. doi: 10.1080/15374411003691784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raine A, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Lynam D. Neurcognitive impairments in boys on the life-course persistent antisocial path. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114:38–49. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS, Valente E. Social information-processing patterns partially mediate the effect of early physical abuse on later conduct problems. J Abnorm Psychol. 1995;104:632–643. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.4.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lahey BB, Van Hulle CA, D'Onofrio BM, Rodgers JL, Waldman ID. Is parental knowledge of their adolescent offspring's whereabouts and peer associations spuriously associated with offspring delinquency? J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2008;36:807–823. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9214-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lansford JE, Criss MM, Laird RD, Shaw DS, Petit GS, Bates JE, et al. Reciprocal relations between parents’ physical discipline and children's externalizing behavior during middle childhood and adolescence. Dev Psychopathol. 2011;23:225–238. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trentacosta CJ, Criss MM, Shaw DS, Lacourse E, Hyde LW, Dishion TJ. Antecedents and outcomes of joint trajectories of mother-son conflict and warmth during middle childhood and adolescence. Child Dev. 2011;82:1676–1690. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01626.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dodge KA, Greenberg MT, Malone PS. Testing an idealized dynamic cascade model of the development of serious violence in adolescence. Child Dev. 2008;79:1907–1927. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nock MK, Kazdin AE, Hiripi E, Kessler RC. Prevalence, subtypes, and correlates of DSM-IV conduct disorder in the National Comorbity Survey Replication. Psychol Med. 2006;36:699–710. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nock MK, Kazdin AE, Hiripi E, Kessler RC. Lifetime prevalence, correlates, and persistence of oppositional defiant disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48:703–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Serbin LA, Stack DM, De Genna N, Grunzeweig N, Temcheff CE, Schwartzmann AE, et al. When aggressive girls become mothers: Problems in parenting, health, and development across two generations. In: Putallaz M, Bierman K, editors. Aggression, antisocial behavior, and violence among girls. Guilford; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagin DS, Pogarsky G, Farrington DP. Adolescent mothers and the criminal behavior of their children. Law Soc Rev. 1997;31:137–162. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frick PJ, Nigg JT. Current issues in the diagnosis of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, and Conduct Disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:77–107. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.United Nations Children's Fund . Adolescence: An Age of Opportunity. United Nations Children's Fund; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist 2/3 and 1992 profile. University of Vermont; Burlington, VT: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 41.NICHD Early Child Care Research Network Trajectories of physical aggression from toddlerhood to middle childhood. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2004;69:vii–129. doi: 10.1111/j.0037-976x.2004.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muthen L, Muthen B. Mplus 6.12 (Statistical Program) 2010.

- 44.King KM, Chassin L. Adolescent stressors, psychopathology, and young adult substance dependence: A prospective study. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69:629–638. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muthen BO, du Toit SHC. Robust inference using weighted least squares and quadratic estimating equations in latent variable modeling with categorical and continuous outcomes. 1997 Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lahey BB, Waldman ID. A developmental propensity model of the origins of conduct problems during childhood and adolescence. In: Lahey B, Moffitt T, Caspi A, editors. The causes of conduct disorder and serious juvenile delinquency. Guilford; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bell RQ. A reinterpretation of the direction of effects in studies of socialization. Psychol Rev. 1968;75:81–95. doi: 10.1037/h0025583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keenan K, Wroblewski K, Hipwell A, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Age of onset, symptom threshold, and expansion of the nosology of conduct disorder for girls. J Abnorm Psychol. 2010;119:689–698. doi: 10.1037/a0019346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Goozen SHM, Fairchild G, Snoek H, Harold GT. The evidence for a neurobiological model of childhood antisocial behavior. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:149–182. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burt SA, Neiderhiser JM. Aggressive versus nonaggressive antisocial behavior: Distinctive etiological moderation by age. Dev Psychol. 2009;45:1164–1176. doi: 10.1037/a0016130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Frick PJ, Viding E. Antisocial behavior from a developmental psychopathology perspective. Dev Psychopathol. 2009;21:1111–1131. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Calkins SD, Graziano PA, Keane SP. Cardiac vagal regulation differentiates among children at risk for behavior problems. Biol Psychol. 2007;74:144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group The effects of the Fast Track preventive intervention on the development of conduct disorder. Child Dev. 2011;82:331–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01558.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shaw DS, Connell A, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN, Gardner F. Improvements in maternal depression as a mediator of intervention effects on early childhood problem behavior. Dev Psychopathol. 2009;21:417–439. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Moving to opportunity: An experimental study of neighborhood effects on mental health. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1576–1582. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Caldwell BM, Bradley RH. Home observation for measurement of the environment. University of Arkansas at Little Rock; Little Rock, AR: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Straus MA. Family violence in American families: Incidence rates, causes, and trends. In: Knudsen D, Miller J, editors. Abused and battered. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bavolek SJ. The development of the adolescent parenting inventory: Identification of high risk adolescents prior to parenthood. Utah State University; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Crnic KA, Greenberg MT. Minor parenting stresses with young children. Child Dev. 1990;61:1628–1637. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bates JE, Freeland CA, Lounsbury ML. Measurement of infant difficultness. Child Dev. 1979;50:794–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gross HE, Shaw DS, Burwell RA, Nagin DS. Transactional processes in child disruptive behavior and maternal depression: A longitudinal study from early childhood to adolescence. Dev Psychopathol. 2009;21:139–156. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Trentacosta CJ, Hyde LW, Shaw DS, Cheong J. Adolescent dispositions for antisocial behavior in context: The roles of neighborhood dangerousness and parental knowledge. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118:564–575. doi: 10.1037/a0016394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. Third Edition The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schultz D, Shaw DS. Boys’ maladaptive social information processing, family emotional climate, and pathways to early conduct problems. Social Dev. 2003;12:440–460. [Google Scholar]