Abstract

Purpose

Esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) is a highly aggressive disease with poor long-term survival. Despite growing knowledge of its biology, no molecular biomarkers are currently used in routine clinical practice to determine prognosis or aid clinical decision making. Hence, this study set out to identify and validate a small, clinically applicable immunohistochemistry (IHC) panel for prognostication in patients with EAC.

Patients and Methods

We recently identified eight molecular prognostic biomarkers using two different genomic platforms. IHC scores of these biomarkers from a UK multicenter cohort (N = 374) were used in univariate Cox regression analysis to determine the smallest biomarker panel with the greatest prognostic power with potential therapeutic relevance. This new panel was validated in two independent cohorts of patients with EAC who had undergone curative esophagectomy from the United States and Europe (N = 666).

Results

Three of the eight previously identified prognostic molecular biomarkers (epidermal growth factor receptor [EGFR], tripartite motif-containing 44 [TRIM44], and sirtuin 2 [SIRT2]) had the strongest correlation with long-term survival in patients with EAC. Applying these three biomarkers as an IHC panel to the validation cohort segregated patients into two different prognostic groups (P < .01). Adjusting for known survival covariates, including clinical staging criteria, the IHC panel remained an independent predictor, with incremental adverse overall survival (OS) for each positive biomarker (hazard ratio, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.40 per biomarker; P = .02).

Conclusion

We identified and validated a clinically applicable IHC biomarker panel, consisting of EGFR, TRIM44, and SIRT2, that is independently associated with OS and provides additional prognostic information to current survival predictors such as stage.

INTRODUCTION

Esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) is a highly lethal cancer with a rapidly increasing incidence in the Western world.1 Despite advances in clinical care, the prognosis for EAC remains dismal, with less than 20% of patients surviving 5 years.2 Currently, standard staging algorithms based on tumor depth (T stage), presence and number of regional nodes with metastatic disease (N stage), and presence or absence of distant metastasis (M stage) are used to predict survival for these patients.3 This approach does not take into account the biology or molecular features of each individual tumor, which may explain the widely varying 5-year overall survival (OS), ranging from 11% to 41%, within groups of patients who otherwise seem similar by these standard staging algorithms.4 It is increasingly evident that tremendous heterogeneity between patients exists in the biology underlying EAC; hence, the ideal staging system would take into account the biology and molecular features of each individual tumor and correlate prognosis with patient-specific tumor biomarkers.5,6 Importantly, advancing knowledge of the molecular characteristics of the tumor would also enable the application of targeted therapies to improve selective killing of cancer cells.7–9

Our group has previously described two independent methods to identify molecular prognostic markers in EAC using gene expression analysis and array-comparative genomic hybridization arrays.10,11 These two independent studies identified eight biologically relevant molecular targets (tripartite motif-containing 44 [TRIM44], sirtuin 2 [SIRT2], epidermal growth factor receptor [EGFR], 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate synthase 2 [PAPSS2], nei-like 2 [NEIL2], Wilms tumor 1 [WT1], myotubularin-related protein 9 [MTMR9], deoxycytidine kinase [DCK]) that could be screened via immunohistochemistry (IHC) to help prognostication in patients with EAC. However, testing for multiple biomarkers via IHC would decrease clinical applicability, and also, not all identified targets seem to have equal prognostic or therapeutic value. Therefore, to facilitate clinical utility, we aimed to create a small optimized panel of IHC markers selected from these eight potential molecular targets that could be used to segregate patients into different prognostic groups.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Population for Generation and Validation of Best Prognostic Targets

Our original study cohort from six tertiary centers (OCCAMS [Oesophageal Cancer Clinical and Molecular Stratification Study] group) in the United Kingdom used to identify the eight molecular prognostic markers in EAC has previously been described.10,11 Briefly, this cohort consisted of 374 patients with esophageal and gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinomas who underwent potentially curative surgery at one of the six OCCAMS centers.

For independent validation of the refined IHC biomarker panel, two independent retrospective cohorts of patients with EAC (where paraffin material was available) from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC; Pittsburgh, PA) and the Erasmus Medical Center, University Medical Center Rotterdam (EMC; Rotterdam, the Netherlands), were used. After approval by the relevant institutional review boards, the clinical data from both centers were combined into a single database and reviewed for consistency. All patients had pathologically confirmed adenocarcinoma of the esophagus or gastroesophageal junction (GEJ), underwent esophagectomy with curative intent, and underwent follow-up at their respective centers. In total, 363 patients from UPMC (1996 to 2009) and 314 patients from EMC (1995 to 2006) were included as a combined validation cohort (N = 677). Patients who died within 1 month of surgery were deemed to have postoperative mortality and were excluded from further analysis. In total, 666 patients were included in the analysis.

Clinical characteristics of patients from both validation centers are listed in Table 1. As expected, most patients who underwent surgery in both centers were men. However, there were some notable differences in clinical characteristics between the two centers. Patients from Pittsburgh were slightly older (age 67.0 v 64.7 years; P < .01) and had a shorter follow-up time (24.5 v 24.2 months; P = .04). More patients in the Pittsburgh cohort had had an R0 resection (94.4% v 70.1%; P < .01), accompanied by a lower rate of recurrence (36.8% v 64.0%; P < .01). More patients from the Pittsburgh cohort also had earlier T stage, and correspondingly fewer patients from Pittsburgh received neoadjuvant chemotherapy compared with patients from Rotterdam (2.5% v 14.8%; P < .01).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients in Validation Cohorts

| Characteristic | Pittsburgh (n = 356) |

Rotterdam (n = 310) |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Age at surgery, years | < .01 | ||||

| Median | 67.0 | 64.7 | |||

| Range | 23-91 | 33-90 | |||

| Follow-up time, months | .04 | ||||

| Median | 24.5 | 24.2 | |||

| Range | 0.49-156.50 | 1.08-191.41 | |||

| Sex | .28 | ||||

| Male | 297 | 83.4 | 268 | 86.5 | |

| Female | 59 | 16.6 | 42 | 13.5 | |

| Recurrence | 131 | 36.8 | 183 | 64.0 | < .01 |

| Radicality | < .01 | ||||

| R0 | 335 | 94.4 | 216 | 70.1 | |

| R1 | 20 | 5.6 | 92 | 29.9 | |

| Histology grade (differentiation) | .20 | ||||

| Well | 30 | 8.5 | 15 | 4.9 | |

| Moderate | 150 | 42.4 | 132 | 43.4 | |

| Poor | 174 | 49.2 | 157 | 51.6 | |

| Pathologic T stage | < .01 | ||||

| T1 | 155 | 43.5 | 45 | 14.6 | |

| T2 | 37 | 10.4 | 54 | 17.5 | |

| T3 | 159 | 44.7 | 207 | 67.0 | |

| T4 | 5 | 1.4 | 3 | 1.0 | |

| Pathologic N stage | < .01 | ||||

| N0 | 152 | 42.8 | 102 | 33.0 | |

| N1 | 203 | 57.2 | 207 | 67.0 | |

| Pathologic M stage | < .01 | ||||

| M0 | 342 | 96.1 | 250 | 80.9 | |

| M1 | 14 | 3.9 | 59 | 19.1 | |

| Chemotherapy | < .01 | ||||

| Yes | 9 | 2.5 | 46 | 14.8 | |

| No | 347 | 97.5 | 264 | 85.2 | |

| Alive | 161 | 45.2 | 90 | 29.0 | < .01 |

NOTE. Sums of numbers may not add up to total number of patients in cohort because of missing data.

Generation and Validation of Biomarker Panel for Prognostication in Patients With EAC

To generate a new IHC biomarker panel from the previously identified eight molecular prognostic targets, a Cox proportional hazards model was used to evaluate the hazard ratio (HR) for each molecular target to rank its prognostic importance. Molecular targets with the highest HRs were selected and brought forward for validation in the cohorts of patients with EAC.

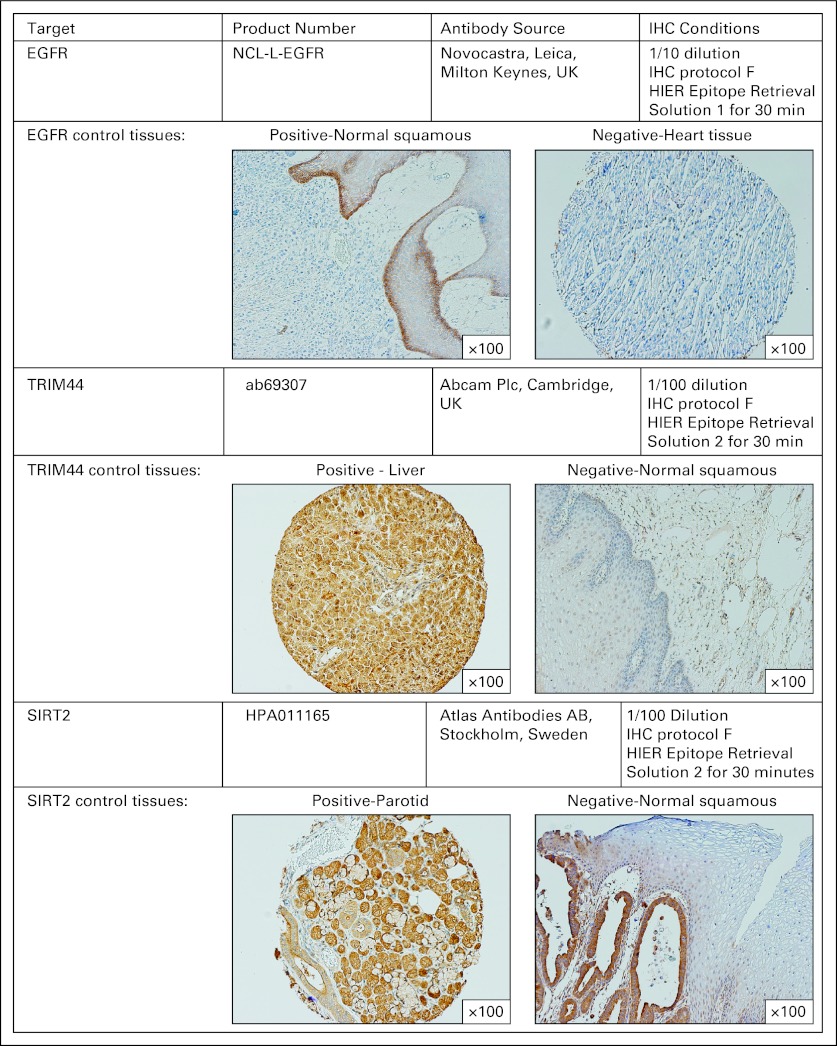

For validation of the three selected molecular targets as a prognostic IHC panel, archival slides from each tumor specimen from UPMC and EMC were reviewed by an expert pathologist, who marked out areas representative of the tumor, accounting for tumor heterogeneity. Cores (0.6 mm) from three areas were then removed from paraffin blocks, and tumor microarrays were constructed. IHC was performed on a Bond system (Leica Microsystems, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom) according to manufacturer recommendations. Antibody sources, conditions used for IHC, and scoring criteria are detailed in Appendix Figure A (online only).

Clinical End Points and Statistical Analysis

The primary clinical end point in the validation study was OS, defined as time from surgery to death resulting from any cause. Death beyond 5 years was censored. To compare differences in demographic and clinical factors between the two validation cohorts, t test or Mann-Whitney test was used for continuous variables, and χ2 test was used for categorical variables. Kaplan-Meier curves were plotted to compare 5-year survival by the number of dysregulated molecular targets in the IHC panel. A multivariate Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the independent association between the IHC panel and prognosis after adjusting for demographic and clinical factors. A P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 19.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Generation of Revised Prognostic Biomarker Panel

Using univariate Cox regression, IHC scores for each of the eight molecular prognostic targets were analyzed together for the first time in the original OCCAMS cohort (N = 374). A significantly increased HR for death was identified with dysregulation of EGFR, TRIM44, and SIRT2 (Appendix Table A1, online only). Dysregulation of PAPSS2, NEIL2, and MTMR9 were associated with a nonsignificant increased HR for death, whereas WT1 and DCK were associated with a nonsignificant decreased HR for death. The biomarkers that were statistically significantly associated with differential HR for death (TRIMM44, SIRT2, and EGFR) were then selected for inclusion in a combined biomarker panel for validation.

Validation of Revised Prognostic Biomarker Panel

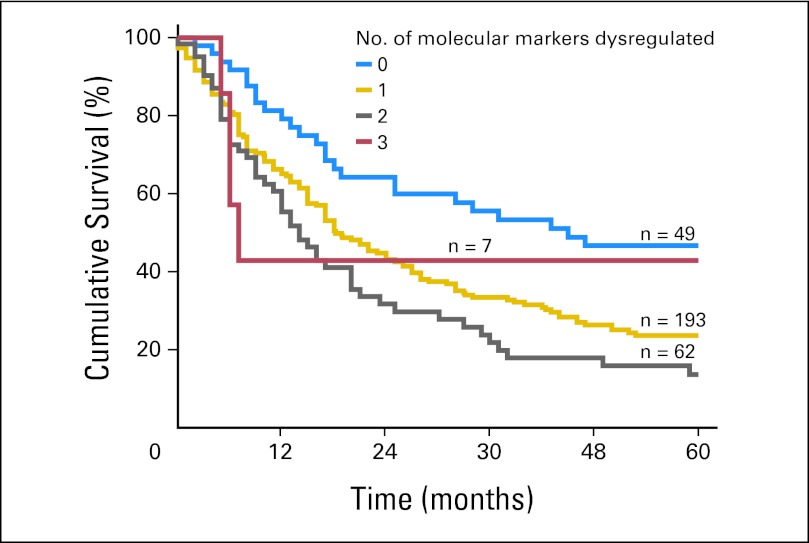

Validation of the new biomarker panel comprising TRIMM44, SIRT2, and EGFR began with internal validation using the OCCAMS study group (Appendix Fig A, online only). Among the OCCAMS study patients, median survival times for those with zero, one, two, and three dysregulated molecular markers were 45.0, 18.2, 14.0, and 7.0 months, respectively (P ≤ .01). For every one additional dysregulated molecular marker, the HR increased by 1.44 (95% CI, 1.18 to 1.75). After adjusting for age, sex, T stage, N stage, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and tumor differentiation (grade), the HR for death for each additional marker increased by 1.34 (95% CI, 1.09 to 1.66).

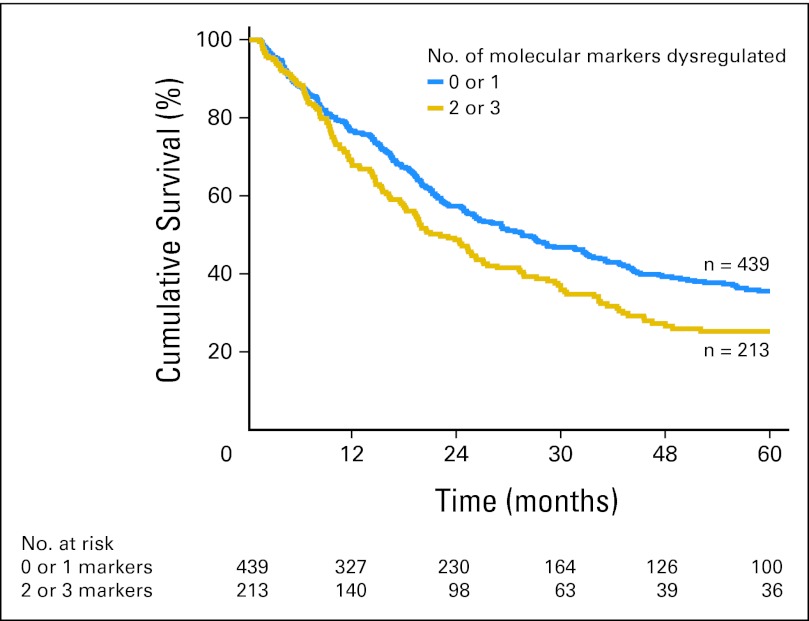

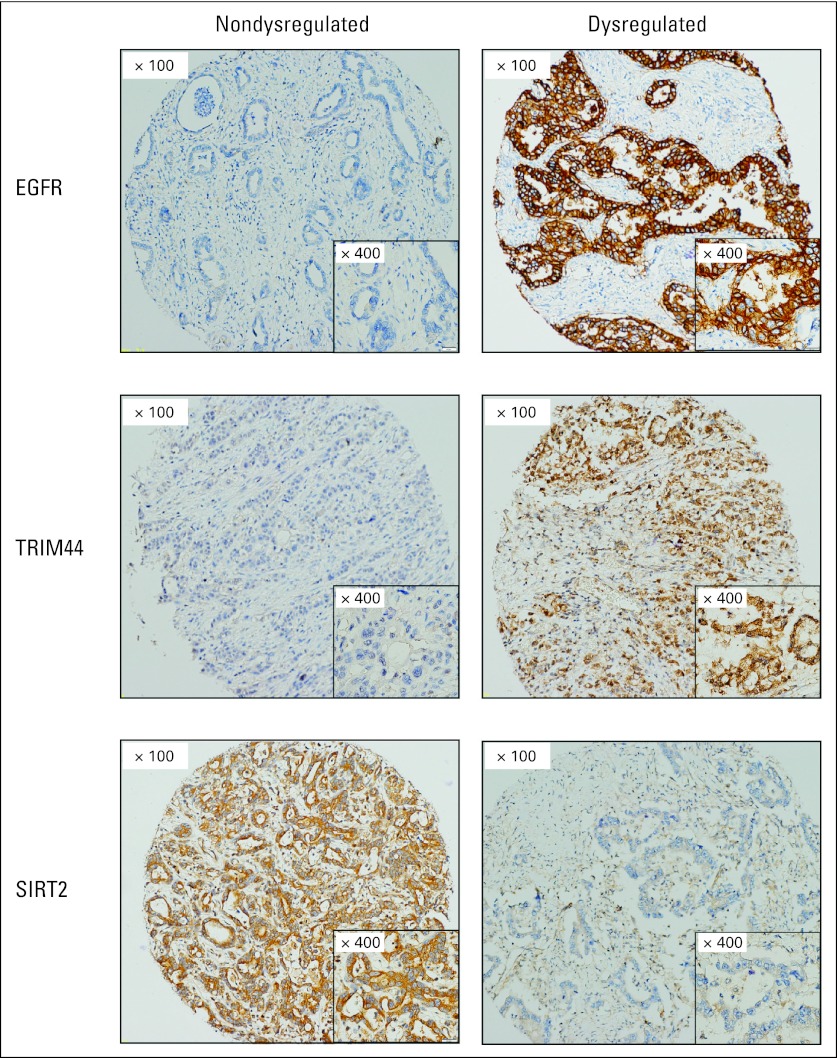

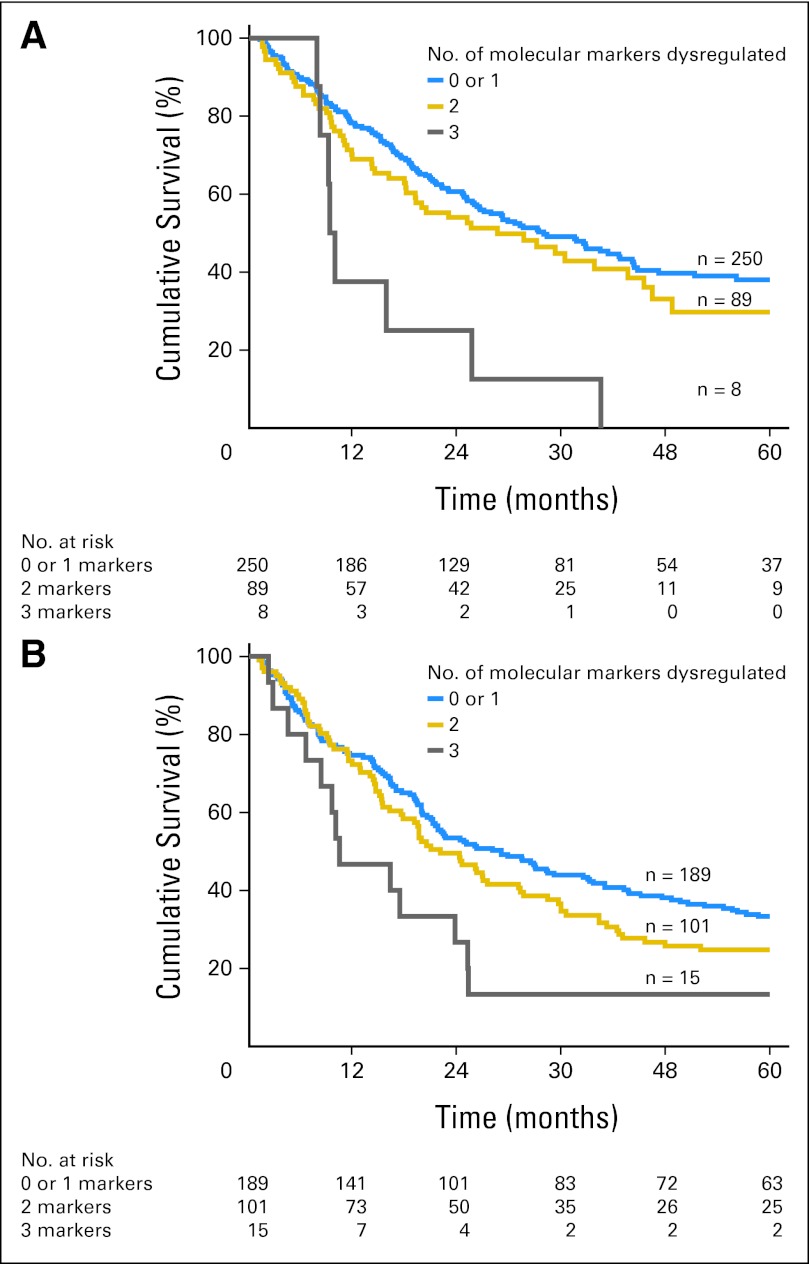

External validation of the IHC panel was then performed in the cohort of patients from UPMC and EMC (Table 2). When patients in the validation cohorts were grouped according to the total number of dysregulated markers, there was no difference in the OS of patients with zero or one dysregulated marker (median survival, 38.8 v 29.8 months, respectively; P = .48). These two groups of patients were therefore combined into one prognostic group. The number of patients with three dysregulated markers was small; therefore, these patients were also combined with patients with two dysregulated markers to facilitate clinical utility. Patients with two or three dysregulated markers had a much poorer prognosis compared with patients with zero or one dysregulated marker (median survival, 22.0 v 31.4 months, respectively; P < .01; Fig 1). The relative HRs with dysregulation for each marker are listed in Appendix Table A2 (online only). Representative examples of dysregulated and nondysregulated IHC expression of TRIMM44, SIRT2, and EGFR performed on the validation cohorts from Pittsburgh and Rotterdam are shown in Figure 2. The results of the IHC panel for each of the individual validation cohorts are shown in Appendix Figures A and A3B (online only).

Table 2.

IHC Panel Gene Dysregulation Frequency in Validation Cohorts

| Marker | Pittsburgh |

Rotterdam |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| No. of dysregulated molecular markers | < .01 | ||||

| 0 | 47 | 13.5 | 20 | 6.6 | |

| 1 | 203 | 58.5 | 169 | 55.4 | |

| 2 | 89 | 25.6 | 101 | 33.1 | |

| 3 | 8 | 2.3 | 15 | 4.9 | |

| TRIM44 | < .01 | ||||

| Nondysregulated | 133 | 38.0 | 80 | 26.2 | |

| Dysregulated | 217 | 62.0 | 225 | 73.8 | |

| EGFR | < .01 | ||||

| Nondysregulated | 323 | 91.5 | 240 | 77.4 | |

| Dysregulated | 30 | 8.5 | 70 | 22.6 | |

| SIRT2 | .07 | ||||

| Nondysregulated | 187 | 53.0 | 186 | 60.0 | |

| Dysregulated | 166 | 47.0 | 124 | 40.0 | |

Abbreviations: EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; IHC, immunohistochemistry; SIRT2, sirtuin 2; TRIM44, tripartite motif-containing 44.

Fig 1.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) panel is highly prognostic. Application of the IHC panel to all validation cohort patients segregated patients into two main prognostic groups (P < .01).

Fig 2.

Representative examples of dysregulated and nondysregulated immunohistochemistry expression of EGFR, SIRT2, and TRIM44 on tissue microarrays. Overexpression of EGFR and TRIM44 constitutes dysregulation, whereas loss of SIRT2 constitutes dysregulation, based on their effect on prognosis and known biologic roles. EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; SIRT2, sirtuin 2; TRIM44, tripartite motif-containing 44.

Determining Independent Prognostic Value of Three-Biomarker IHC Panel

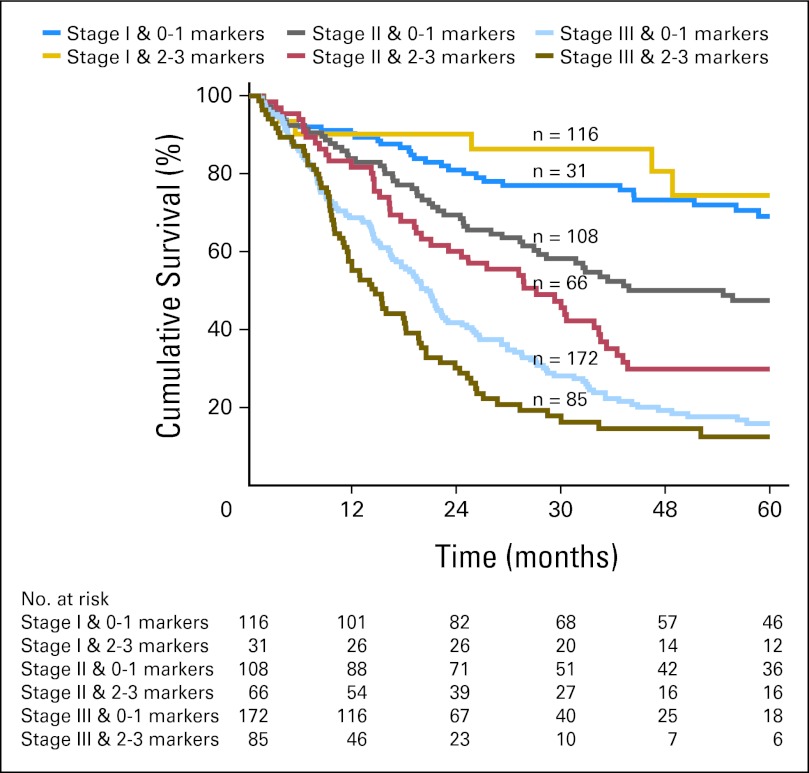

Having demonstrated that the three-biomarker panel had significant and additive predictive value for long-term survival, multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to determine whether the IHC panel provided additional prognostic information independent of clinicopathologic features known to affect prognosis. Adjusting for center, pathologic T stage, N stage, age, sex, resection margin status, tumor differentiation, and treatment with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the results of the IHC panel remained significant in the multivariate Cox regression model (Table 3). As summarized in Table 3, the HR for death increased by 1.20 (95% CI, 1.03 to 1.40) for each increase in the IHC panel. The prognostic value of combined pathologic stage and increasing number of molecular markers was then assessed. Stratifying patients with both stage and number of molecular markers showed a clear separation into distinct prognostic groups in the validation cohorts (P < .001; Fig 3). The breakdown of all patients into various stages of disease and number of molecular markers dysregulated is summarized in Appendix Table A3 (online only). Patients with stage I disease could not be further stratified with the IHC panel, but patients with stage II or III disease could be prognosticated based on the number of markers dysregulated. Patients with stage II disease had an increased HR for death of 1.40 (95% CI, 1.08 to 1.8) for each increase in the IHC panel. Similarly, patients with stage III disease had an increased risk of death for every increase in number of dysregulated markers (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.08 to 1.57).

Table 3.

Univariate and Multivariate Survival Analyses in Combined Validation Cohorts

| Characteristic | Univariate |

Multivariate |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| N stage | ||||||

| N0 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| N1 | 3.19 | 2.53 to 4.02 | < .01 | 1.81 | 1.38 to 2.39 | < .01 |

| T stage | ||||||

| T1 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| T2 | 1.45 | 0.99 to 2.11 | .06 | 1.02 | 0.68 to 1.55 | .92 |

| T3 | 3.60 | 2.77 to 4.68 | < .01 | 1.93 | 1.39 to 2.68 | < .01 |

| T4 | 9.04 | 4.31 to 18.94 | < .01 | 6.93 | 2.94 to 16.36 | < .01 |

| Age (per year increase) | 1.01 | 1.00 to 1.02 | .03 | 1.02 | 1.01 to 1.03 | < .01 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Male | 1.15 | 0.87 to 1.52 | .31 | 1.03 | 0.77 to 1.37 | .85 |

| Radicality | ||||||

| R0 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| R1 | 2.75 | 2.19 to 3.46 | < .01 | 1.65 | 1.26 to 2.15 | < .01 |

| Histology grade (differentiation) | ||||||

| Well | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Moderate | 3.01 | 1.59 to 5.71 | < .01 | 1.74 | 0.90 to 3.36 | .10 |

| Poor | 5.67 | 3.01 to 10.68 | < .01 | 2.81 | 1.45 to 5.43 | < .01 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Yes | 0.64 | 0.43 to 0.94 | .02 | 0.63 | 0.41 to 0.96 | .03 |

| Study center | ||||||

| Pittsburgh | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Rotterdam | 1.22 | 1.00 to 1.48 | .05 | 0.94 | 0.75 to 1.19 | .62 |

| IHC panel (per score increase) | 1.30 | 1.12 to 1.50 | < .01 | 1.20 | 1.03 to 1.40 | .02 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; IHC, immunohistochemistry; Ref, reference.

Fig 3.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) panel adds to current staging criteria in patient prognostication. Combination of stage and the IHC panel separated patients into distinct prognostic groups (P < .01).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that an IHC panel consisting of three molecular markers generated and validated among 1,040 patients with EAC can be used to aid prognosis prediction in those with EAC. Furthermore, this IHC panel is independent of clinical features known to influence prognosis and can serve as an adjunct to current staging systems.

Reducing mortality from advanced EAC remains the greatest challenge in the field.12,13 To achieve this aim, accurate prognostication, development of better surgical care and chemoradiotherapeutic regimes, and identification of novel therapeutics are key areas to address.5,6, 12,14–16

Previous studies have attempted to better determine prognosis for patients with EAC using nomograms based on clinical features.17–19 There have also been a large number of studies correlating molecular markers, identified by either a candidate gene or gene expression microarray approach, to prognosis in this disease.5,20,21 However, none of these molecular panels have reached clinical utility, largely because these biomarkers or prognostic signatures have been generated in underpowered cohorts. To best determine prognosis, we envisioned that a combination of clinical features and well-validated prognostic markers would be required to stratify patients with EAC into clinically meaningful prognostic subgroups. Importantly, the molecular markers used would have to be independent of clinical features and ideally would account for the biology of these tumors rather than being purely molecular passengers. This strategy formed the basis of our study to identify an independently prognostic IHC signature to be used in conjunction with current staging modalities.

The primary goal of this study was to identify a panel of biomarkers that could be readily implemented into clinical practice and provide improved prognostication for patients with EAC. This alone is of value to patients and their providers because it will facilitate more accurate discussions about long-term survival when compared with the discussions using current clinicopathologic features alone. The ultimate goal, however, would be to use these molecular biomarkers to guide therapeutic interventions. Unlike other cancer types, such as breast, colorectal, and non–small-cell lung cancers, where targeted therapies are already in clinical use,22 targeted therapy for EAC is still in its infancy. Biomarker targets with prognostic significance and biologic importance in tumor development would be the ideal clinical panel. On the basis of our own work and that of other investigators, the three biomarkers in our panel may both provide prognostic information and identify patients who might benefit from targeted therapy. For example, EGFR is currently being evaluated as a potential target for therapy in this disease.23,24 SIRT2 is a gene with known tumor suppressor and oncogenic functions. Our data strongly suggest SIRT2 to be a tumor suppressor in EAC. A recent report highlighted SIRT2 as a tumor suppressor in hepatocellular carcinoma and breast cancer by regulating mitosis and genome integrity.25 Importantly, the authors reported that SIRT2 deficiency resulted in Aurora-A and -B overexpression, hence promoting tumor growth. Inhibitors targeting Aurora-A and -B are being evaluated in clinical trials with promising results.26–28 The next step would be to evaluate if SIRT2-deficient EAC would respond clinically to targeted therapy with Aurora inhibitors. Lastly, TRIM44 belongs to a large family of TRIM proteins, and recent scientific advances have identified this class of proteins to have potential for pharmacologic inhibition in cancer.29,30 Although TRIM44 has previously unknown functions, recent data from our laboratory have demonstrated that EAC and breast tumors with high TRIM44 levels are highly susceptible to mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition in vitro and in vivo. Hence, high TRIM44 expression could serve as a biomarker for effective mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition.31

A major strength of our study is the use of a simple IHC panel consisting of three molecular markers as a tool to help prognostication in patients with EAC. These three molecular targets were identified as the most-prognostic targets of the eight targets identified in our previous reports.10,11 Consistently, the combined panel of these three markers could be used to predict prognosis in patients with EAC independently of current staging algorithms. Existing pathology services could easily adopt the IHC panel as a routine test to determine the status of these three molecular prognostic targets. The determination of whether a tumor is dysregulated for these markers is also straightforward and can be done in the same setting when a pathologist reviews the slides for staging. This is in contrast to using other more sophisticated platforms that are often not available or appropriately optimized in many clinical settings. A prime example of a molecular target being used in the clinic because of ease of detection with IHC is HER2/NEU. HER2/NEU is a molecular target screened in breast cancer with IHC and fluorescent in situ hybridization; patients with tumors overexpressing HER2/NEU have been shown to benefit from treatment with trastuzumab.32 Because our biomarkers were optimized in IHC using paraffin-embedded tissues, we were able to capitalize on the large stores of EAC specimens in pathology repositories at two high-volume centers to perform our validation. This provided a large number of patients from each center and made the validation process significantly more robust; importantly, this allowed for multivariate Cox regression to dissect the role of various known prognostic factors. In addition, the fact that the biomarker panel worked in both cohorts of patients provided evidence that this IHC biomarker panel was generally applicable to patients with EAC independent of differences in clinical practice. Lastly, the IHC panel could potentially be applied to preoperative biopsies for prognostication in patients preoperatively. This would circumvent problems arising from use of other techniques where the availability of sufficient tissue for extraction of DNA, RNA, or proteins can be problematic.

As with all studies, there are limitations to this one, including its retrospective design. However, we rationalized that for a prospective study to successfully validate any molecular signature, it would have to be robust and easily applicable. This led us to streamline our panel of eight molecular prognostic targets, identified from our previous studies, to three of our most-promising targets for further work. In addition, we wanted to evaluate whether our IHC panel could provide prognostication in patients from different centers with different patient populations, treatment regimens, and surgical approaches. A prospective trial to evaluate our three-gene IHC panel, similar to the MINDACT (Microarray in Node Negative and 1 to 3 Positive Lymph Node Disease may Avoid ChemoTherapy) trial for the MammaPrint (Agendia, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), will be the next step.33 The second limitation of this study is that the IHC panel cannot supersede TNM staging and should be used in conjunction with TNM preoperatively to inform clinical decisions. Our IHC panel hence provides a useful and objective adjunct to current staging criteria that incorporates the heterogeneity existing in the biology of EAC. We have shown that combining TNM staging criteria with our IHC panel allows segregation of patients with stages II and III disease into distinct prognostic groups. There is minimal effect in applying the IHC panel in stage I patients because these patients are diagnosed early and are likely to have a good prognosis regardless (5-year survival, 69.1%). Patients with no abnormal markers in the Cambridge cohort had a better prognosis compared with those with one marker dysregulated. This was not the case in the validation cohorts largely because of the small number of patients in these subgroups, and among individuals with dysregulation of one molecular marker, there were differences in early disease stage between the geographic cohorts. The third limitation to this study is that although IHC is easily applicable to standard clinical pathology laboratories, the scoring of each target using IHC is subjective; however, this problem can be minimized with standard staining-intensity pictures to allow for accurate classification of the staining pattern.

In conclusion, our study confirms that a simple IHC panel of three molecular biomarkers can provide prognostic information in patients with EAC independently of clinical prognostic variables and is applicable to patient cohorts from different continents. These data support the notion that distinct molecular features govern the clinical phenotypes of this disease. Using the IHC panel as an adjunct to current staging systems could be of particular relevance in the preoperative setting where staging data are less accurate or in selected populations of patients for whom the optimal therapeutic approach could be influenced by molecular prognostic information. Identification of patients in a poor prognosis group would not necessarily dictate withdrawal of chemotherapy or the choice of curative surgery; however, this study has also identified novel molecular targets that should be investigated to determine whether they can offer more-tailored therapeutic options to patients with EAC.

Appendix

Scoring Criteria

Scoring for each of the selected targets was based on intensity of staining in tumor epithelial cells. For each marker, a core was scored on a scale of 0 (no staining) to 3 (strong staining) if at least 10% of tumor epithelial cells stained positive. For sirtuin 2 (SIRT2) and tripartite motif-containing 44 (TRIM44), positive staining was cytoplasmic, and for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), positive staining was membranous. All targets were assessed in three cores by two independent scorers blinded to clinical outcome. For scoring of SIRT2, the final intraobserver score was calculated as the average of the assigned intensity score for all three cores. For EGFR and TRIM44, the intraobserver score was assigned based on the maximum intensity score assigned within the three cores for each individual patient. The rationale for this was that we noted that staining of the three targets on whole paraffin sections of EAC demonstrated that TRIM44 and EGFR could have heterogenous staining, whereas decreased expression or loss of SIRT2 staining tended to be homogenous. It also simplified scoring from a clinical perspective because the maximum intensity of staining for EGFR and TRIM44 on whole-tissue sections should be used to determine the status of the staining.

The determination of whether a marker was dysregulated was based on the known biology of the molecular targets based on our previous study. SIRT2 is a known tumor suppressor, and EGFR and TRIM44 have been shown to confer an oncogenic effect when overexpressed. Hence, a score of 0 or 1 was considered dysregulated, whereas a score of 2 or 3 was considered nondysregulated in the case of SIRT2. Conversely, a score of 0 or 1 was considered nondysregulated, whereas a score of 2 or 3 was considered dysregulated in the case of EGFR and TRIM44. The final scores were then checked by an expert GI pathologist for 12.5% of all cores (one of eight) for each validation target to confirm that the consensus score was accurate.

Fig A1.

Antibody sources and conditions used for immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Fig A2.

Internal validation of TRIM44, SIRT2, and EGFR as a combined IHC panel for prognostication in patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma in the original Oesophageal Cancer Clinical and Molecular Stratification Study cohort.

Fig A3.

Application of the immunohistochemistry panel to all patients resulted in segregation of patients into three prognostic groups in both the (A) Pittsburgh (P < .01) and (B) Rotterdam cohorts (P = .02).

Table A1.

HRs of Each Molecular Marker Derived From Univariate Cox Regression Analysis in Original OCCAMS Cohort

| Marker | HR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRIM44 | 1.31 | 1.01 to 1.70 | .04 |

| SIRT2 | 1.31 | 1.03 to 1.67 | .03 |

| EGFR | 1.52 | 1.03 to 2.26 | .04 |

| PAPSS2 | 1.24 | 0.96 to 1.61 | .10 |

| NEIL2 | 1.12 | 0.87 to 1.43 | .39 |

| WT1 | 0.71 | 0.39 to 1.30 | .27 |

| MTMR9 | 1.14 | 0.87 to 1.51 | .34 |

| DCK | 0.98 | 0.75 to 1.28 | .86 |

Abbreviations: DCK, deoxycytidine kinase; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; HR, hazard ratio; MTMR9, myotubularin-related protein 9; NEIL2, nei-like 2; OCCAMS, Oesophageal CancerClinical and Molecular Stratification Study; PAPSS2, 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate synthase 2; SIRT2, sirtuin 2; TRIM44, tripartite motif-containing 44; WT1, Wilms tumor 1.

Table A2.

HRs of Each Dysregulated Molecular Marker in Validation Cohorts

| Intensity Score | HR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRIM44 | |||

| 0 | Ref | ||

| 1 | 1.46 | 0.89 to 2.44 | .14 |

| 2 | 1.59 | 0.96 to 2.63 | .07 |

| 3 | 1.94 | 1.09 to 3.44 | .02 |

| SIRT2 | |||

| 3 | Ref | ||

| 2 | 1.69 | 1.10 to 2.60 | .02 |

| 1 | 1.81 | 1.24 to 2.64 | < .01 |

| 0 | 1.37 | 0.96 to 1.97 | .08 |

| EGFR | |||

| 0 | Ref | ||

| 1 | 0.83 | 0.66 to 1.04 | .10 |

| 2 | 1.41 | 1.05 to 1.91 | .02 |

| 3 | 0.94 | 0.58 to 1.52 | .80 |

Abbreviations: EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; HR, hazard ratio; Ref, reference; SIRT2, sirtuin 2; TRIM44, tripartite motif-containing 44.

Table A3.

Prognostic Effect of IHC Panel in Patients With Different Disease Stages* in All Three Cohorts

| No. of MMs Dysregulated | Univariate |

Multivariate† |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Stage I (n = 175) | ||||||

| 0 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| 1 | 0.60 | 0.25 to 1.47 | .27 | 0.70 | 0.28 to 1.73 | .44 |

| 2 | 0.51 | 0.17 to 1.58 | .24 | 0.53 | 0.17 to 1.66 | .27 |

| 3 | 1.23 | 0.15 to 10.22 | .85 | 2.95 | 0.31 to 27.67 | .34 |

| Per 1 MM | 0.81 | 0.46 to 1.42 | .45 | 0.83 | 0.48 to 1.46 | .52 |

| Stage II (n = 288) | ||||||

| 0 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| 1 | 1.51 | 0.90 to 2.56 | .12 | 1.73 | 0.92 to 3.25 | .09 |

| 2 | 1.90 | 1.10 to 3.30 | .02 | 2.01 | 1.03 to 3.93 | .04 |

| 3 | 2.71 | 1.00 to 7.35 | .05 | 4.67 | 1.53 to 14.30 | < .01 |

| Per 1 MM | 1.35 | 1.08 to 1.68 | < .01 | 1.40 | 1.08 to 1.83 | .01 |

| Stage III (n = 441) | ||||||

| 0 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| 1 | 1.73 | 1.15 to 2.60 | < .01 | 1.59 | 1.01 to 2.50 | .04 |

| 2 | 1.99 | 1.29 to 3.09 | < .01 | 1.62 | 1.00 to 2.64 | .05 |

| 3 | 4.61 | 2.30 to 9.22 | < .01 | 4.68 | 2.22 to 9.87 | < .01 |

| Per 1 MM | 1.39 | 1.18 to 1.64 | < .01 | 1.30 | 1.08 to 1.57 | < .01 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; IHC, immunohistochemistry; MM, molecular marker; Ref, reference.

According to American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual (sixth ed).

Adjusted for age, sex, study center, N stage, T stage, radicality, tumor grade, and chemotherapy.

Footnotes

Written on behalf of the Oesophageal Cancer Clinical and Molecular Stratification Study Group.

Supported by Grant No. MC-A040-5PP10 from the Medical Research Council (R.C.F.); by Award No. K07CA151613 from the National Cancer Institute and by the Singapore National Research Foundation (NRF) under its NRF–Ministry of Health (MOH) overseas scholarship, administered by the Singapore MOH National Medical Research Council (K.S.N.); and by the Cambridge Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre and the National Institute for Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Medical Research Council, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, or Singapore Ministry of Health National Medical Research Council.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: None Stock Ownership: James D. Luketich, Johnson and Johnson Honoraria: None Research Funding: James D. Luketich, Accuray, Precision Therapeutics, Torax Medical Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Chin-Ann J. Ong, Richard H. Hardwick, Rebecca C. Fitzgerald

Provision of study materials or patients: Richard H. Hardwick

Collection and assembly of data: Chin-Ann J. Ong, Joel Shapiro, Katie S. Nason, Jon M. Davison, Caryn Ross-Innes, Winand N.M. Dinjens, Katharina Biermann, Nicholas Shannon, Susannah Worster, Laura K.E. Schulz, James D. Luketich, Bas P.L. Wijnhoven

Data analysis and interpretation: Chin-Ann J. Ong, Joel Shapiro, Katie S. Nason, Jon M. Davison, Xinxue Liu, Maria O'Donovan, James D. Luketich

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Pohl H, Sirovich B, Welch HG. Esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence: Are we reaching the peak? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1468–1470. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al. New York, NY: Springer; 2010. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (ed 7) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johansson J, DeMeester TR, Hagen JA, et al. En bloc vs transhiatal esophagectomy for stage T3 N1 adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus. Arch Surg. 2004;139:627–631. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.6.627. discussion 631-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ong CA, Lao-Sirieix P, Fitzgerald RC. Biomarkers in Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma: Predictors of progression and prognosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5669–5681. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i45.5669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lagarde SM, ten Kate FJ, Richel DJ, et al. Molecular prognostic factors in adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:977–991. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9262-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Syrigos KN, Zalonis A, Kotteas E, et al. Targeted therapy for oesophageal cancer: An overview. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27:273–288. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9117-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villanacci V, Rossi E, Grisanti S, et al. Targeted therapy with trastuzumab in dysplasia and adenocarcinoma arising in Barrett's esophagus: A translational approach. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2008;54:347–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keld RR, Ang YS. Targeting key signalling pathways in oesophageal adenocarcinoma: A reality for personalised medicine? World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2781–2790. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i23.2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goh XY, Rees JR, Paterson AL, et al. Integrative analysis of array-comparative genomic hybridisation and matched gene expression profiling data reveals novel genes with prognostic significance in oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Gut. 2011;60:1317–1326. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.234179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peters CJ, Rees JR, Hardwick RH, et al. A 4-gene signature predicts survival of patients with resected adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, junction, and gastric cardia. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1995.e15–2004.e15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reid BJ, Li X, Galipeau PC, et al. Barrett's oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma: Time for a new synthesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:87–101. doi: 10.1038/nrc2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thallinger CMR, Raderer M, Hejna M. Esophageal cancer: A critical evaluation of systemic second-line therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4709–4714. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.7599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sjoquist KM, Burmeister BH, Smithers BM, et al. Survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for resectable oesophageal carcinoma: An updated meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:681–692. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70142-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leigh Y, Goldacre M, McCulloch P. Surgical specialty, surgical unit volume and mortality after oesophageal cancer surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:820–825. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mukherjee K, Chakravarthy AB, Goff LW, et al. Esophageal adenocarcinoma: Treatment modalities in the era of targeted therapy. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3304–3314. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1187-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lagarde SM, Reitsma JB, Ten Kate FJ, et al. Predicting individual survival after potentially curative esophagectomy for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus or gastroesophageal junction. Ann Surg. 2008;248:1006–1013. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318190a0a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lagarde SM, Reitsma JB, de Castro SM, et al. Prognostic nomogram for patients undergoing oesophagectomy for adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus or gastro-oesophageal junction. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1361–1368. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaur P, Sepesi B, Hofstetter WL, et al. A clinical nomogram predicting pathologic lymph node involvement in esophageal cancer patients. Ann Surg. 2010;252:611–617. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f56419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McManus DT, Olaru A, Meltzer SJ. Biomarkers of esophageal adenocarcinoma and Barrett's esophagus. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1561–1569. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim SM, Park YY, Park ES, et al. Prognostic biomarkers for esophageal adenocarcinoma identified by analysis of tumor transcriptome. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e15074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martini M, Vecchione L, Siena S, et al. Targeted therapies: How personal should we go? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:87–97. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okines A, Cunningham D, Chau I. Targeting the human EGFR family in esophagogastric cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:492–503. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dragovich T, Campen C. Anti-EGFR-targeted therapy for esophageal and gastric cancers: An evolving concept. J Oncol. doi: 10.1155/2009/804108. [epub ahead of print on July 14, 2009] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim HS, Vassilopoulos A, Wang RH, et al. SIRT2 maintains genome integrity and suppresses tumorigenesis through regulating APC/C activity. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:487–499. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lapenna S, Giordano A. Cell cycle kinases as therapeutic targets for cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:547–566. doi: 10.1038/nrd2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katayama H, Sen S. Aurora kinase inhibitors as anticancer molecules. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799:829–839. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diamond JR, Bastos BR, Hansen RJ, et al. Phase I safety, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic study of ENMD-2076, a novel angiogenic and Aurora kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:849–860. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hatakeyama S. TRIM proteins and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:792–804. doi: 10.1038/nrc3139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urano T, Usui T, Takeda S, et al. TRIM44 interacts with and stabilizes terf, a TRIM ubiquitin E3 ligase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;383:263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ong CAJ, Shannon NB, Lao-Sirieix P, et al. OC-017 TRIM44: From prognosis to therapy in oesophageal adenocarcinoma and breast cancer. Gut. 2012;61(suppl 2):A8. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perez EA, Reinholz MM, Hillman DW, et al. HER2 and chromosome 17 effect on patient outcome in the N9831 adjuvant trastuzumab trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4307–4315. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cardoso F, Van't Veer L, Rutgers E, et al. Clinical application of the 70-gene profile: The MINDACT trial. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:729–735. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.3222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]