Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine the effect of prolonged 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-1 (11β-HSD1) inhibition on basal and hormone-stimulated glucose metabolism in fasted conscious dogs. For 7 days prior to study, either an 11β-HSD1 inhibitor (HSD1-I; n = 6) or placebo (PBO; n = 6) was administered. After the basal period, a 4-h metabolic challenge followed, where glucagon (3×-basal), epinephrine (5×-basal), and insulin (2×-basal) concentrations were increased. Hepatic glucose fluxes did not differ between groups during the basal period. In response to the metabolic challenge, hepatic glucose production was stimulated in PBO, resulting in hyperglycemia such that exogenous glucose was required in HSD-I (P < 0.05) to match the glycemia between groups. Net hepatic glucose output and endogenous glucose production were decreased by 11β-HSD1 inhibition (P < 0.05) due to a reduction in net hepatic glycogenolysis (P < 0.05), with no effect on gluconeogenic flux compared with PBO. In addition, glucose utilization (P < 0.05) and the suppression of lipolysis were increased (P < 0.05) in HSD-I compared with PBO. These data suggest that inhibition of 11β-HSD1 may be of therapeutic value in the treatment of diseases characterized by insulin resistance and excessive hepatic glucose production.

Keywords: 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-1, cortisol, hepatic glucose production, glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis

cortisol is a steroid hormone with many physiological effects, including the regulation of carbohydrate, protein, and fat metabolism. At pathological concentrations, cortisol produces metabolic abnormalities similar to the metabolic syndrome, including obesity, insulin resistance, fasting hyperglycemia, hypertension, and dyslipidemia (2, 42, 56, 58). In vivo cortisol action can be modified by 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-1 (11β-HSD1), an enzyme that converts intracellular cortisone into active cortisol without necessarily modifying plasma cortisol concentrations (4, 6, 59). Liver (55, 57) and adipose (30, 33) 11β-HSD1 activity has been shown to be elevated in obese humans with type 2 diabetes mellitus and the metabolic syndrome, and an intracellular Cushings-like state may contribute to these abnormalities (28, 32). In mice, hepatic 11β-HSD1 overexpression can increase hepatic lipid flux, thereby causing dyslipidemia and insulin resistance (46), whereas overexpression in adipose tissue causes obesity, impaired glucose tolerance, and hypertension (35, 36). Conversely, when the enzyme is knocked out or acutely inhibited, mouse models of diabetes are protected against the manifestations of the metabolic syndrome (1, 31, 43). Together, these data demonstrate an overarching ability of dysregulated cortisol metabolism to generate a phenotype similar to that of type 2 diabetes and illustrate the potential therapeutic value of 11β-HSD1 inhibition in the treatment of insulin resistance.

Cortisol has potent effects on the glucoregulatory actions of hormones that regulate hepatic glucose production (HGP). For example, cortisol has been shown to impair insulin action and potentiate glucagon- and epinephrine-mediated increases in HGP (21, 22, 53). In addition, we recently showed that acute administration of an 11β-HSD1 inhibitor lowered HGP during combined insulin and glucagon deficiency in healthy dogs (16), suggesting that cortisol can also regulate glucose production independent of its interactions with these hormones. In that study, the reduction in HGP seen during 11β-HSD1 inhibition was accounted for by a reduction in the rate of glycogenolysis, whereas gluconeogenesis remained unchanged. Interestingly, however, both phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) and glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase) mRNA levels decreased, raising the possibility that gluconeogenesis would have been reduced had enough time for meaningful changes in the levels of those enzymes been allowed. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the effect of 7 days of 11β-HSD1 inhibition on basal glucose metabolism and on the metabolic responses to a hormonal challenge known to augment HGP by increasing gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis (23, 25).

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Animals and surgical procedures.

Studies were carried out in conscious 42-h-fasted dogs of either sex (20–23 kg). This length of fast in the canine does not induce hypoglycemia, raise the plasma levels of stress hormones, or exhaust liver glycogen (38, 39). In addition, after a 42-h fast approximately two-thirds of hepatic glucose production is accounted for by gluconeogenic flux (48), comparable with overnight-fasted humans. The surgical and animal care facilities met the standards published by the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, and diet and housing were provided as described previously (17). The protocol was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Approximately 16 days before the study, each dog underwent surgery for placement of ultrasonic flow probes (Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY) around the hepatic portal vein and the hepatic artery as well as insertion of silicone rubber catheters for sampling in the hepatic vein, hepatic portal vein, and a femoral artery, with portal vein infusion catheters inserted into splenic and jejunal veins, as described in detail elsewhere (17). The proximal ends of the flow probes and catheters were tucked into subcutaneous pockets. All dogs were determined to be healthy prior to experimentation, as indicated by 1) leukocyte count <18,000/mm3, 2) hematocrit >35%, and 3) good appetite (consuming ≥75% of the daily ration). On the morning when the animals were to be studied, hepatic catheters and flow probe leads were exteriorized from their subcutaneous pockets under local anesthesia. Intravenous (iv) catheters were also inserted into peripheral leg veins for infusion of hormones and substrates as necessary.

Treatment administration.

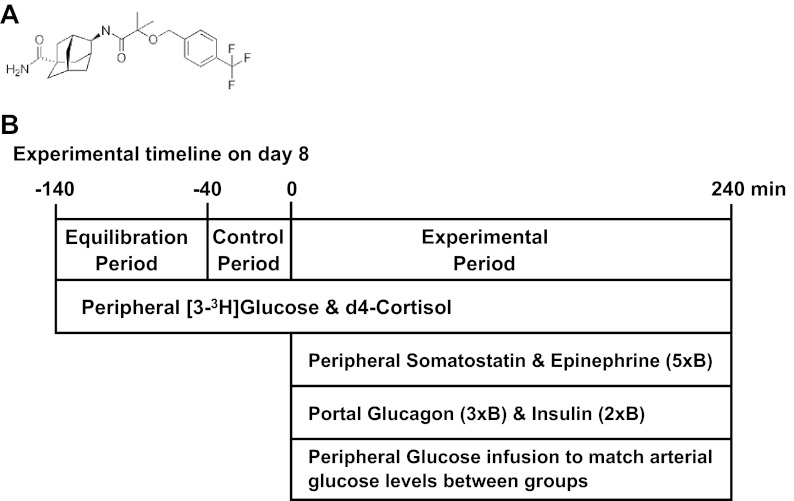

Each animal was randomly assigned to receive either 75 mg of a specific 11β-HSD1 inhibitor (HSD1-I), E-4-{2-methyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzyloxy]propionylamino}adamantane-1-carboxylic acid amide (compound 392, n = 6; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) (Fig. 1A), or placebo (PBO; n = 6) for each of 7 days prior to being studied. On the day of each study (day 8), animals received a final dose of the respective treatment prior to the start of the experiment.

Fig. 1.

Twelve dogs were dosed daily with either an 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-1 (11β-HSD1) inhibitor (compound 392) or placebo for 8 days, after which they were studied during the basal fasted state and during hormone infusion.

Experimental design.

Each experiment consisted of a 100-min tracer equilibration period (−140 to −40 min), a 40-min period for basal sample collection (−40 to 0 min), and a 240-min experimental period (0–240 min; Fig. 1B). At −140 min, primed, continuous iv infusions of both [9,11,12,12-2H4]cortisol (d4-cortisol; 12 μg/kg prime and 0.147 μg·kg−1·min−1 continuous rate; Isotope Laboratories, Andover, MA) and [3-3H]glucose (42 μCi prime and 0.35 μCi/min continuous rate; Isotope Laboratories) were started. At 0 min, a constant iv infusion of somatostatin (0.8 μg·kg−1·min−1; Bachem, Torrance, CA) was begun to suppress pancreatic insulin and glucagon secretion, and infusion of three-times basal intraportal glucagon (1.5 ng·kg−1·min−1; Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN) and five-times basal peripheral iv epinephrine (91 ng/kg/min; Sigma-Aldrich) was initiated. Also at 0 min, insulin (450 μU·kg−1·min−1; Eli Lilly) was infused intraportally to replicate the hyperinsulinemia that is associated with the hyperglycemia that occurs in insulin-resistant individuals or when glucagon and epinephrine levels are elevated (9, 60). Glucose was infused iv as needed to maintain glycemia at a similar level in each group.

Hematocrit, plasma glucose, [3-3H]glucose, insulin, glucagon, catecholamines, cortisol, d4-cortisol, d3-cortisol, adrenocorticotropic hormone and nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA), and blood alanine, glycine, serine, threonine, lactate, glutamine, glutamate, glycerol, and β-hydroxybutyrate concentrations were determined as described previously (16, 17). RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, real-time PCR, SDS-PAGE, and Western blotting procedures were performed by standard methods (20).

11β-HSD1-Inhibitor.

11β-HSD1 is primarily a reductase, whereas 11β-HSD type 2 (11β-HSD2) generally catalyzes the reverse dehydrogenase reaction (56, 58). Compound 392 is a very selective and potent competitive inhibitor of 11β-HSD1 compared with 11β-HSD2 across several species, including mouse (0.7 vs. 13,000 nM), rat (5.9 vs. 2,480 nM), dog (2.8 vs. 12,550 nM), monkey (1.8 vs. 32,840 nM), and human (1.6 vs. 24,120 nM) (IC50 for 11β-HSD1 vs. 11β-HSD2, respectively). Furthermore, it is not metabolized to any compounds with appreciable 11β-HSD1 or 11β-HSD2 inhibitory activity. Oral bioavailability in the dog following administration of a capsule containing 75 mg of compound 392 was 100%, with a Cmax of 3.75 μg/ml, a plasma half-life of 6.4 h, and an area under the curve of 44 μg·h−1·ml−1. Near-complete suppression of hepatic d3-cortisol production in the present study indicates near-complete inhibition of 11β-HSD1 activity in the liver (Fig. 2B). This is consistent with previous results in the monkey, where a single oral 10 mg/kg dose reduced hepatic 11β-HSD1 enzymatic activity to 2%.

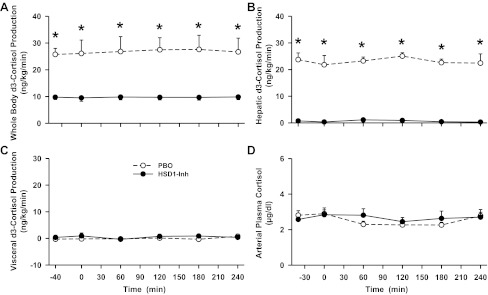

Fig. 2.

Whole body, liver, and visceral (gut) d3-cortisol production rates and arterial plasma cortisol levels in conscious dogs during the basal (−40 to 0 min) and experimental (0–240 min) periods treated with a placebo (PBO; ○) or an 11β-HSD1 inhibitor (HSD1-Inh; ●). Data are means ± SE; n = 6/group. *P < 0.05, HSD1-Inh vs. PBO.

Calculations and data analysis.

Net hepatic substrate balance (NHB) was calculated as LOADout − LOADin. The LOADout = FH × [H], and LOADin = (FA × [A]) + (FP × [P]), where A, P, and H refer to the arterial, portal vein, and hepatic vein substrate concentrations, respectively, and FA, FP, and FH refer to the arterial, portal vein, and hepatic vein (total liver) blood or plasma flow, respectively, as appropriate for the particular substrate. Net hepatic fractional substrate extraction was calculated as NHB/LOADin. Nonhepatic glucose uptake equaled the glucose infusion rate minus net hepatic glucose ouput, where the rate was corrected for changes in the size of the glucose pool, using a pool fraction of 0.65 ml/kg (12) and assuming that the volume of distribution for glucose equaled the volume of the extracellular fluid, or ∼22% of the dog's weight (54). For all glucose balance calculations, glucose concentrations were converted from plasma to blood values using correction factors (ratio of the blood to the plasma concentration) established previously in our laboratory (26, 45). Net visceral (gut) substrate balance (NVB) was calculated using the formula NVB = Loadout − Loadin, where Loadout = FP × [P] and Loadin = FP × [A], abbreviated as indicated above. Net hepatic and visceral fractional extraction were calculated as NHB ÷ hepatic Loadin and NVB ÷ visceral Loadin, respectively.

Glucose turnover, used to estimate endogenous glucose production and whole body glucose uptake, was measured using [3-3H]glucose based on the circulatory model described by Mari et al. (34). The use of isotopically labeled cortisol in the calculation of hepatic cortisol production has been described previously in detail (3, 8, 16). This approach takes advantage of the fact that d4-cortisol loses a deuterium when it is converted into d3-cortisone by 11β-HSD2. This, in turn, is converted into d3-cortisol by 11β-HSD1, thereby providing a measure of 11β-HSD1 activity. Hepatic and visceral d3-cortisol uptake were calculated as hepatic or visceral d3-cortisol Loadin, respectively, multiplied by hepatic or visceral d4-cortisol fractional extraction, as described previously. Hepatic d3-cortisol production was calculated as the difference between hepatic d3-cortisol uptake and net hepatic d3-cortisol balance. Visceral d3-cortisol production is the difference between visceral d3-cortisol uptake and net visceral d3-cortisol balance. Whole body d3-cortisol production was determined by dividing the d4-cortisol infusion rate by the ratio of arterial d4-cortisol to arterial d3-cortisol. Whole body total cortisol production was calculated by dividing the d4-cortisol infusion rate by the arterial plasma d4-cortisol enrichment (i.e., arterial d4-cortisol divided by unlabeled cortisol plus d3-cortisol plus d4-cortisol).

Net hepatic uptake rates of the gluconeogenic precursors alanine, lactate, glycerol, glycine, threonine, and serine were measured using the arteriovenous difference method. It was assumed that all of the gluconeogenic precursors taken up by the liver were completely converted into glucose 6-phosphate (G6P) (17, 18). Gluconeogenic flux to G6P was estimated by summing net hepatic gluconeogenic precursor uptake and dividing by two (to convert the data into glucose equivalents). Net hepatic gluconeogenic flux was calculated by subtracting glycolysis from gluconeogenic flux. Glycolysis was estimated by summing net hepatic lactate output (when it occurred) and glucose oxidation over the course of each experiment. In earlier studies, glucose oxidation was 0.2 ± 0.1 mg·kg−1·min−1 even when the concentrations of circulating insulin, glucose, and NEFA varied widely (40, 51). Because glucose oxidation did not change appreciably under conditions similar to the present study, it was assumed to be constant (0.2 mg·kg−1·min−1). Net hepatic glycogenolysis was determined by subtracting net hepatic gluconeogenic flux from net hepatic glucose output (18).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical comparisons were carried out with SigmaStat Software (San Jose, CA), using ANOVA for repeated measures with post hoc analysis. Statistical significance was accepted when P < 0.05. Data are expressed as means ± SE.

RESULTS

11β-HSD1 activity.

Whole body d3-cortisol production (via 11β-HSD1 activity) was reduced by two-thirds in HSD1-I compared with PBO (P < 0.05 between groups; Fig. 2A), whereas hepatic d3-cortisol production was completely eliminated between −40 and 240 min (23 ± 2 vs. 0 ± 0 ng·kg−1·min−1 in PBO vs. HSD1-I, P < 0.05; Fig. 2B). Visceral d3-cortisol production was undetectable in both groups (Fig. 2C), consistent with previous studies (4, 6, 16). Whole body total cortisol production rates were 233 ± 23 and 225 ± 8 ng·kg−1·min−1 in PBO and HSD1-I, respectively (between −40 and 240 min). Since circulating cortisol levels are tightly regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and net hepatic cortisol balance is relatively low, it is not surprising that the inhibitor had no effect upon arterial cortisol levels (Fig. 2D).

Basal period.

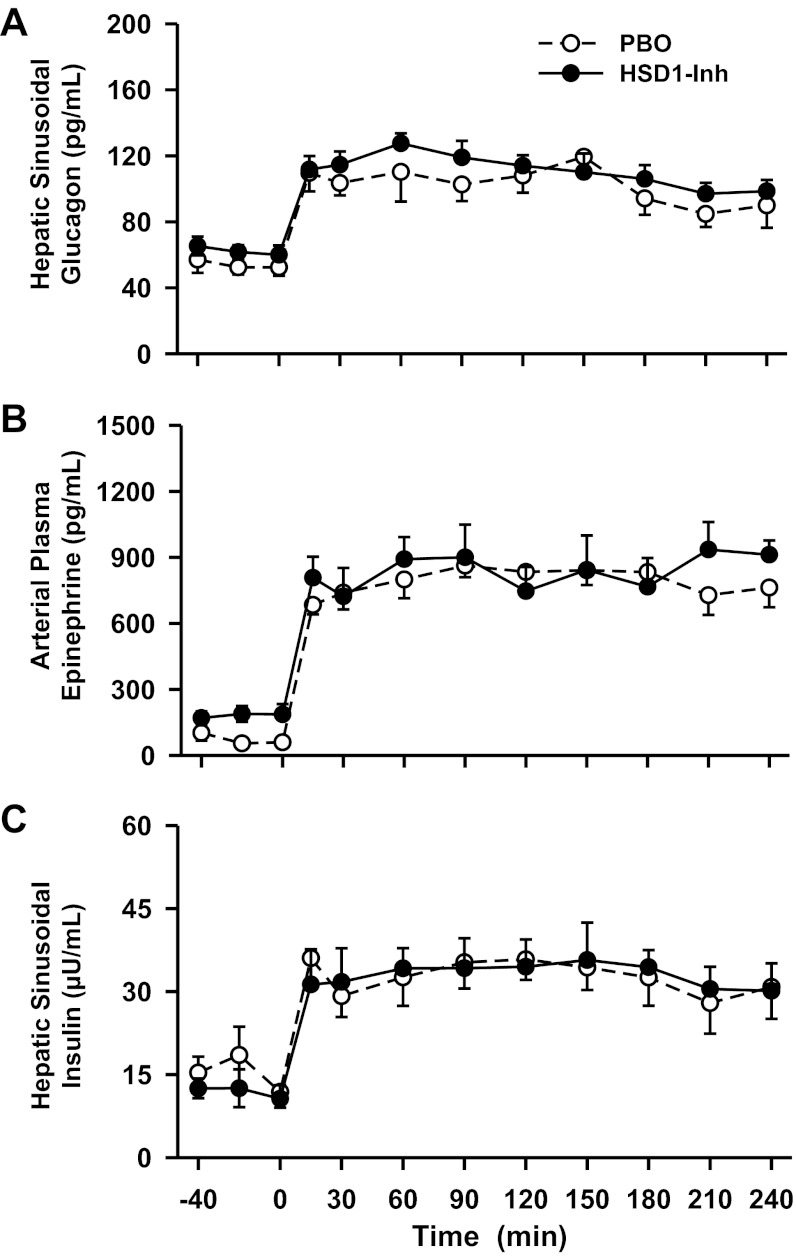

Despite prolonged suppression of intracellular cortisol production (Fig. 2), hepatic sinusoidal glucagon and insulin levels and arterial plasma epinephrine (Fig. 3) did not differ during the basal period. However, there was a tendency for basal insulin levels to be lower and glucagon and epinephrine levels to be increased with 11β-HSD1 inhibition. Subtle (statistically insignificant but biologically important) differences in the concentrations of these hormones may explain partially why plasma glucose levels, liver glucose production, net hepatic glycogenolysis, hepatic gluconeogenic flux, and glucose utilization did not differ between groups during the basal period (Figs. 4–6). In addition, arterial glycerol, NEFA, lactate, and alanine levels and net hepatic β-hydroxybutyrate output, an index of fatty acid oxidation in the liver, did not differ between groups during the basal period (Fig. 7 and Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Hepatic sinusoidal glucagon and insulin and arterial epinephrine levels in conscious dogs during the basal (−40 to 0 min) and experimental (0–240 min) periods treated with a PBO (○) or an HSD1-Inh (●). Data are means ± SE; n = 6/group.

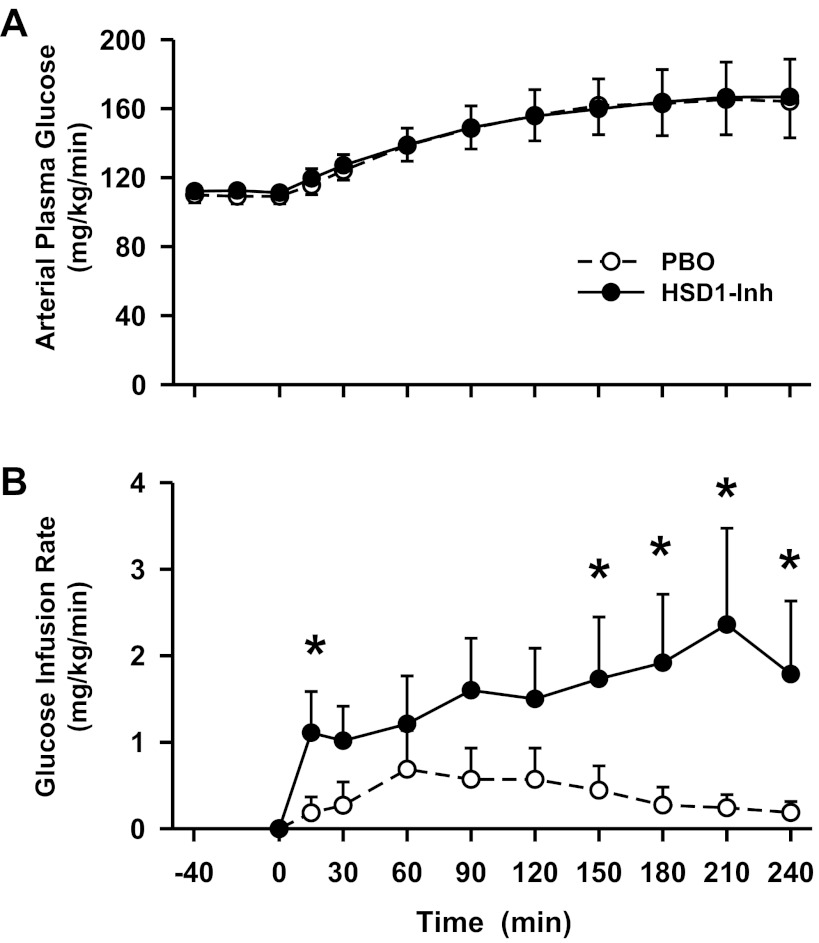

Fig. 4.

Arterial plasma glucose level and glucose infusion rates in conscious dogs during the basal (−40 to 0 min) and experimental (0–240 min) periods treated with a PBO (○) or an HSD1-Inh (●). Data are means ± SE; n = 6/group. *P < 0.05, HSD1-Inh vs. PBO.

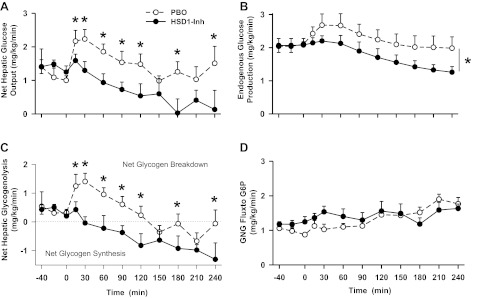

Fig. 5.

Net hepatic glucose output, endogenous glucose production, net hepatic glycogenolysis, and gluconeogenic flux rates in conscious dogs during the basal (−40 to 0 min) and experimental (0–240 min) periods treated with a PBO (○) or an HSD1-Inh (●). Data are means ± SE; n = 6/group. *P < 0.05, HSD1-Inh vs. PBO.

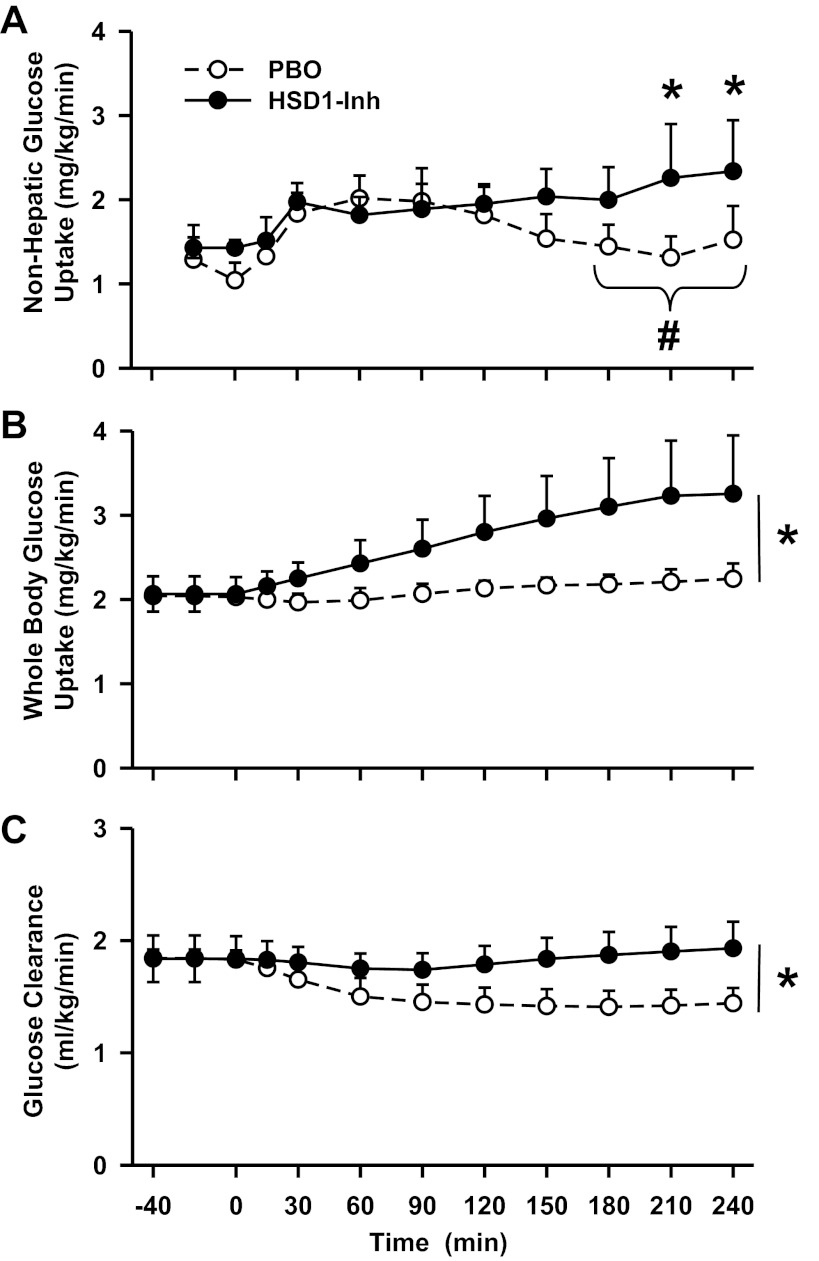

Fig. 6.

Nonhepatic and whole body glucose uptake and arterial glucose clearance rates in conscious dogs during the basal (−40 to 0 min) and experimental (0–240 min) periods treated with a PBO (○) or an HSD1-Inh (●). Data are means ± SE; n = 6/group. *P < 0.05, HSD1-Inh vs. PBO; #P < 0.05, HSD1-Inh vs. PBO area under the curve.

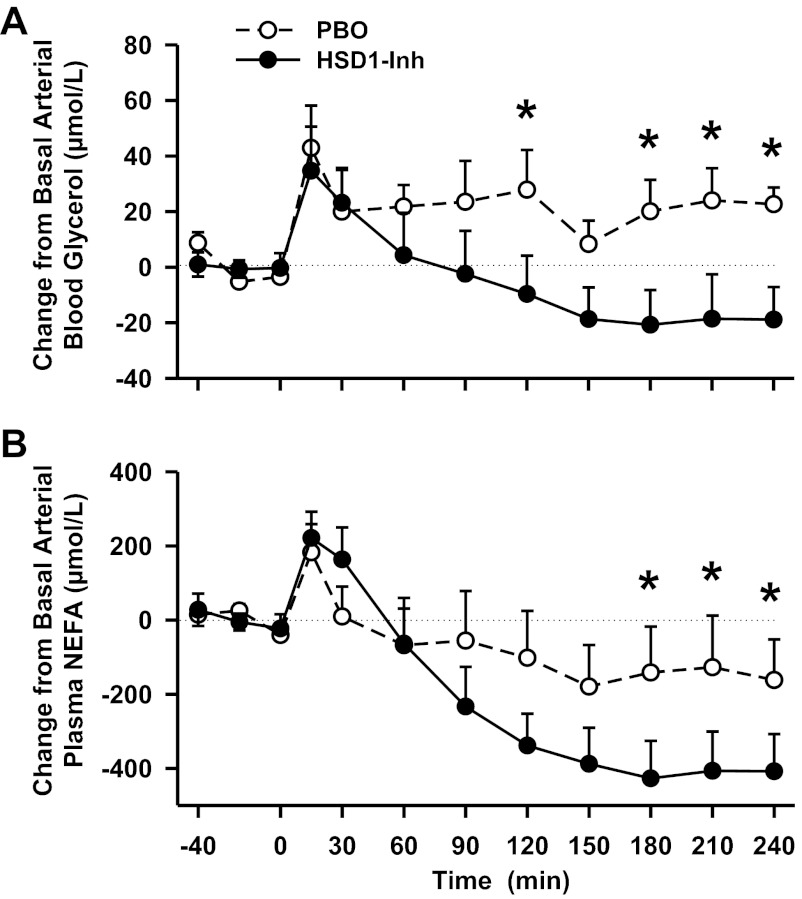

Fig. 7.

Change from basal arterial blood glycerol and plasma nonesterified free fatty acid (NEFA) levels in conscious dogs during the basal (−40 to 0 min) and experimental (0–240 min) periods treated with a PBO (○) or an HSD1-Inh (●). Data are means ± SE; n = 6/group. *P < 0.05, HSD1-Inh vs. PBO. Average basal glycerol levels were 77 ± 5 and 97 ± 9 μmol/l, and basal NEFA levels were 695 ± 65 and 779 ± 87 μmol/l in PBO and HSD1-Inh, respectively.

Table 1.

Hormone and substrate concentrations and net hepatic balances

| Control Period, min |

Hormone Infusion Period, min |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | −40 | −20 | 0 | 15 | 30 | 60 | 90 | 120 | 150 | 180 | 210 | 240 |

| Arterial norepinephrine levels, pg/ml | ||||||||||||

| PBO | 125 ± 22 | 112 ± 16 | 113 ± 14 | 84 ± 16 | 87 ± 15 | 78 ± 17 | 91 ± 11 | 111 ± 25 | 86 ± 16 | 102 ± 15 | 108 ± 21 | 122 ± 21 |

| HSD1-Inh | 115 ± 13 | 155 ± 33 | 125 ± 11 | 78 ± 15 | 109 ± 31 | 97 ± 20 | 86 ± 17 | 96 ± 17 | 122 ± 31 | 114 ± 24 | 120 ± 22 | 140 ± 36 |

| Arterial blood lactate, μmol/l | ||||||||||||

| PBO | 388 ± 71 | 353 ± 49 | 325 ± 17 | 404 ± 32 | 635 ± 85 | 1,019 ± 158 | 1,371 ± 195 | 1,752 ± 215 | 1,900 ± 280 | 1,839 ± 356 | 2,153 ± 312 | 2,022 ± 315 |

| HSD1-Inh | 365 ± 28 | 392 ± 66 | 511 ± 175 | 554 ± 68 | 769 ± 150 | 1,253 ± 372 | 1,568 ± 322 | 1,761 ± 360 | 1,792 ± 355 | 1,777 ± 361 | 1,726 ± 359 | 1,656 ± 326 |

| Net hepatic lactate uptake, μmol·kg−1·min−1 | ||||||||||||

| PBO | 5.5 ± 0.6 | 4.9 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 5.5 ± 1.2 | 5.0 ± 1.1 | 5.6 ± 0.8 | 5.8 ± 1.1 | 8.2 ± 1.2 | 8.1 ± 1.0 | 9.2 ± 1.2 | 12.4 ± 1.1 | 11.4 ± 1.2 |

| HSD1-Inh | 6.1 ± 0.5 | 5.3 ± 0.8 | 5.9 ± 1.1 | 7.5 ± 1.0 | 8.3 ± 1.4 | 6.5 ± 2.4 | 6.7 ± 2.1 | 8.3 ± 2.5 | 7.6 ± 2.9 | 5.1 ± 1.7 | 8.6 ± 1.7 | 9.4 ± 1.4 |

| Net hepatic glycerol uptake, μmol·kg−1·min−1 | ||||||||||||

| PBO | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.3 |

| HSD1-Inh | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

| Arterial blood alanine, μmol/l | ||||||||||||

| PBO | 270 ± 22 | 262 ± 15 | 273 ± 16 | 270 ± 11 | 259 ± 13 | 290 ± 21 | 318 ± 25 | 344 ± 25 | 375 ± 24 | 381 ± 30 | 399 ± 34 | 402 ± 37 |

| HSD1-Inh | 300 ± 25 | 294 ± 27 | 335 ± 41 | 344 ± 39 | 331 ± 39 | 369 ± 56 | 400 ± 66 | 417 ± 63 | 431 ± 62 | 433 ± 61 | 430 ± 61 | 419 ± 59 |

| Net hepatic alanine uptake, μmol·kg−1·min−1 | ||||||||||||

| PBO | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 3.7 ± 0.3 |

| HSD1-Inh | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 4.1 ± 0.2 | 4.6 ± 0.4 | 4.1 ± 0.3 |

| Arterial blood β-hydroxybutyrate, μmol/l | ||||||||||||

| PBO | 52 ± 7 | 55 ± 10 | 47 ± 6 | 58 ± 8 | 43 ± 7 | 36 ± 7 | 33 ± 8 | 29 ± 7 | 28 ± 4 | 33 ± 9 | 25 ± 2 | 25 ± 3 |

| HSD1-Inh | 46 ± 9 | 44 ± 10 | 47 ± 12 | 53 ± 14 | 46 ± 11 | 40 ± 12 | 28 ± 8 | 23 ± 5 | 25 ± 8 | 25 ± 8 | 23 ± 6 | 25 ± 1 |

| Net hepatic β-hydroxybutyrate output, μmol·kg−1·min−1 | ||||||||||||

| PBO | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 |

| HSD1-Inh | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.3 |

Data are means ± SE. PBO, placebo; HSD1-Inh, 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-1 inhibitor.

Hormone challenge period.

During the metabolic challenge (0–240 min), the hepatic sinusoidal glucagon and arterial epinephrine levels were clamped at three- and fivefold basal, respectively, and were similar between groups (Fig. 3). As expected, arterial norepinephrine levels remained basal throughout the study in both groups (Table 1). In response to the metabolic hormone challenge, the arterial glucose levels rose from 109 to 165 mg/dl in PBO (Fig. 4A). Glucose was infused to match the plasma glucose levels between groups, and this rate was greater in HSD1-I than in PBO (2.07 ± 0.97 vs. 0.21 ± 0.14 mg·kg−1·min−1, respectively, during the last hour, P < 0.05; Fig. 4B). Hepatic insulin levels were clamped at twofold basal to replicate the hyperinsulinemia that is associated with the hyperglycemia that occurs with insulin resistance and stress (9, 60).

The hormone infusion protocol was associated with transient increases in net hepatic glucose output (Fig. 5A) and endogenous glucose production (Fig. 5B) in PBO. In contrast, 11β-HSD1 inhibition diminished these effects (P < 0.05) by reducing net hepatic glycogenolysis (P < 0.05; Fig. 5C). Hepatic gluconeogenic flux increased modestly in both groups (Fig. 5D) but was not affected by 11β-HSD1 inhibition.

11β-HSD1 inhibition also affected the regulation of nonhepatic glucose metabolism. Although the hormone infusion challenge only transiently increased nonhepatic glucose uptake in PBO and had little to no effect on whole body glucose utilization, both parameters were increased in HSD1-I compared with PBO (P < 0.05; Fig. 6, A and B). The area under the curve for nonhepatic glucose uptake over the final hour was 141 ± 30 vs. 81 ± 14 mg·kg−1·60 min−1, in HSD1-I and PBO, respectively (P < 0.05). Arterial glucose clearance was reduced in PBO, probably due to the effects of epinephrine on muscle glucose uptake, whereas 11β-HSD1 inhibition prevented that reduction (P < 0.05; Fig. 6C). The effect of the inhibitor on glucose utilization may have also been due in part to greater suppression of lipolysis, since arterial glycerol and NEFA levels (Fig. 7) were reduced by ∼40% in HSD1-I compared with PBO (P < 0.05). Epinephrine is a potent simulator of skeletal muscle glycogen degradation and glycolysis. Thus, arterial lactate levels and net hepatic lactate uptake increased in both groups. Arterial β-hydroxybutyrate, alanine, and lactate levels and net hepatic balance of these substrates were not affected significantly by 11β-HSD1 inhibition (Table 1).

Previously, we showed that acute 11β-HSD1 inhibition decreased the gluconeogenic mRNA levels of both PEPCK and G6Pase as well as the PEPCK protein level (16). However, in the current study, neither PEPCK (1.0 ± 0.1 and 0.9 ± 0.2 in PBO and HSD1-I, respectively, arbitrary units), G6Pase (1.0 ± 0.2 and 1.2 ± 0.1, respectively), nor pyruvate carboxylase (1.0 ± 0.2 and 0.8 ± 0.2, respectively) liver mRNA levels differed between groups at the end of the study. Likewise, PEPCK (1.0 ± 0.2 and 1.2 ± 0.1 in PBO and HSD1-I, respectively) and pyruvate carboxylase (1.0 ± 0.1 and 1.0 ± 0.2, respectively) protein levels did not differ.

DISCUSSION

11β-HSD1 increases intracellular cortisol concentrations, which can have deleterious effects on substrate metabolism in tissues where it is expressed, such as the liver and adipose tissues (2, 42, 56, 58). Although most individuals with diabetes do not exhibit elevated circulating cortisol concentrations, an intracellular Cushings-like state may contribute to glucose dysregulation (28, 32). In the present study, we show that inhibition of 11β-HSD1 during a metabolic hormone challenge inhibits hepatic glucose production (by reducing glycogenolysis) and increases whole body glucose utilization and the suppression of lipolysis.

Splanchnic (gut and liver) and whole body rates of 11β-HSD1-mediated cortisol production were determined to verify the effect of the 11β-HSD1 inhibitor. In agreement with previous findings (4, 6, 16), release of cortisol by the gut was undetectable in both groups, suggesting that 11β-HSD1 activity in visceral adipose tissue is negligible. Whereas the inhibitor eliminated hepatic cortisol production, cortisol produced by the liver in the control group was almost as great as whole body 11β-HSD1 cortisol production, indicating that the liver is the primary site of nonadrenal cortisol production. Consistent with our previous report (16), arterial cortisol levels were similar between groups. This is reflective of low (∼10%) liver cortisol production relative to the rest of the body and the fact that splanchnic cortisol uptake accounts for the majority of splanchnic production (6). Since intracellular cortisol concentrations and action are determined by the balance between adrenally derived and 11β-HSD1-facilitated cortisol production, tissues with high 11β-HSD1 activity, like the liver, could be expected to display more pronounced effects of 11β-HSD1 inhibition, whereas glucocorticoid-sensitive tissues lacking 11β-HSD1 expression would not.

Hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes is characterized by reduced glucose utilization and elevated HGP due to increased gluconeogenesis and/or glycogenolysis (5, 7, 44). To determine whether the effects of 11β-HSD1 inhibition would be apparent during conditions in which these processes were elevated, glucagon and epinephrine were infused. These hormones cause insulin resistance; glycogenolysis is stimulated, gluconeogenesis is amplified due to increased substrate supply and lipolysis, and glucose clearance is reduced (9, 25, 60). Consequent hyperglycemia leads to hyperinsulinemia, but the anti-insulin effects of cortisol, glucagon, and catecholamines mitigate insulin's effects. Since cortisol both antagonizes the effects of insulin and augments the actions of glucagon and epinephrine (21, 22, 53), we hypothesized that intrahepatic reduction of cortisol would improve liver glucose metabolism when circulating glucagon, epinephrine, and insulin levels were elevated.

In the absence of 11β-HSD1 inhibition, the hormonal challenge led to predictable increases in HGP and arterial plasma glucose levels, which were accounted for by increases in glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis. Meanwhile, peripheral glucose utilization did not increase in the control group despite hyperglycemic and hyperinsulinemic conditions, an effect that was most likely due to the inhibitory effect of epinephrine on insulin-stimulated muscle glucose uptake (10). In contrast, whole body and hepatic responses to the hormonal challenge were altered significantly during 11β-HSD1 inhibition. In particular, stimulation of hepatic glucose production was prevented and glucose utilization increased, thereby making exogenous glucose infusion necessary to match glycemic levels between groups.

Although cortisol can increase hepatic gluconeogenesis, acute inhibition of 11β-HSD1 (16) or intrahepatic glucocorticoid receptor signaling (19) was shown previously to regulate HGP through effects on glycogen metabolism. In addition, chronic hypercortisolemia had a more pronounced effect on glycogenolysis than gluconeogenesis during acute insulin deficiency (24). Consistent with those results, our data show that even after prolonged 11β-HSD1 inhibition it was hepatic glycogen metabolism, not gluconeogenic flux, that was affected by 11β-HSD1 inhibition. However, it remains possible that gluconeogenesis might be reduced under other circumstances, such as when the gluconeogenic precursor supply is elevated (23, 37). Nevertheless, the initial glycogenolytic surge that occurred in the control group was completely absent in the presence of the inhibitor such that net hepatic glycogenolysis remained suppressed throughout the study period despite elevated glucagon and epinephrine levels. This effect may have been mediated by increased insulin sensitization and/or decreased glucagon and epinephrine action in response to the reduction in cortisol during 11β-HSD1 inhibition. Cortisol can decrease insulin receptor binding (13) and affect postreceptor insulin action (50) in part by decreasing PI3K activity (11). Cortisol has also been shown to maintain physiological glycogen phosphorylase levels (52) and increase glucagon binding to hepatocytes (15). In addition, the potent effects of epinephrine and glucagon on glycogenolysis (25) are synergistically increased by cortisol (21, 53), probably via sensitization of the glycogenolytic process to cAMP (22). Thus, a reduction in intrahepatic cortisol levels via 11β-HSD1 inhibition would be expected to decrease hepatic glycogenolysis.

In addition to its glucoregulatory effects on the liver, cortisol can also regulate whole body substrate metabolism in part by sensitizing adipose tissue to the action of lipolytic hormones (47, 60). Whereas epinephrine infusion caused an initial increase in circulating glycerol and NEFA levels in both groups, lipolysis was reduced by 11β-HSD1 inhibition, which was in line with studies in adrenalectomized rats in which epinephrine-stimulated NEFA and glycerol release were impaired (22). This may have been due to an effect in subcutaneous adipose tissue since 11β-HSD1 activity was negligible in visceral tissues. The reduction in plasma NEFA may have allowed for greater glucose utilization seen in response to 11β-HSD1 inhibition. It is also possible that glucose uptake was increased by a dampening of the direct effects of cortisol on muscle insulin sensitivity and/or a reduction in the inhibitory effect of epinephrine on muscle glucose uptake (10). Although expression of 11β-HSD1 is low in the skeletal muscle of mice (27, 42), cortisol has been shown to potently induce insulin resistance in skeletal muscle through the glucocorticoid receptor (14), and 11β-HSD1 inhibition can increase skeletal muscle's sensitivity to insulin (41, 61). Regardless, the whole body response to the hormone challenge was improved by 11β-HSD1 inhibition due to complementary changes in glucose metabolism in both the liver and nonhepatic tissues.

In the present study, 1 wk of 11β-HSD1 inhibition did not appear to affect basal hormone or substrate concentrations. Because hepatic glucose metabolism is exquisitely sensitive to small changes in insulin and glucagon, it is possible that subtle variation in pancreatic hormone secretion was sufficient to maintain normal metabolism during the treatment. Nevertheless, our data do not provide compelling evidence that 11β-HSD1 inhibition altered basal fasting glucose, protein, or fat metabolism in these lean healthy animals. On the other hand, excess HGP [due to increased gluconeogenesis and/or glycogenolysis (5, 7, 44)] and decreased glucose clearance are hallmarks of type 2 diabetes (49) and stress-related hyperglycemia (21, 53), and it is possible that 11β-HSD1 inhibition would manifest important beneficial effects under pathological conditions (29).

In summary, our data show that 7 days of 11β-HSD1 inhibition had marked effects on whole body responses to a hormonally generated metabolic challenge. Of particular note, 11β-HSD1 inhibition ameliorated the stimulation of HGP, an effect that was accounted for primarily by inhibition of net hepatic glycogenolysis. Glucose utilization and the suppression of lipolysis were also increased during 11β-HSD1 inhibition.

GRANTS

This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Diabetes Research and Training Center Grant SP-60-AM-20593. C. J. Ramnanan was supported by an American Diabetes Association Mentor-based Fellowship. A. D. Cherrington was supported by the Jacquelyn A. Turner and Dr. Dorothy J. Turner Chair in Diabetes Research.

DISCLOSURES

P. Jacobson and P. Jung are employees of Abbott Laboratories, which provided financial support and compound 392 to complete the reported studies. A. D. Cherrington is a consultant for Abbott Laboratories. There are no other conflicts of interest to declare. D. S. Edgerton is the guarantor of this work, had full access to all of the data, and takes full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.J.W., C.J.R., V.S., J.R., M.S., P. Jung, R.B., and D.S.E. performed the experiments; J.J.W., C.J.R., V.S., M.S., and D.S.E. analyzed the data; J.J.W., C.J.R., V.S., R.B., A.D.C., and D.S.E. interpreted the results of the experiments; J.J.W., A.D.C., and D.S.E. prepared the figures; J.J.W., A.D.C., and D.S.E. drafted the manuscript; J.J.W., C.J.R., V.S., J.R., P. Jacobson, P. Jung, R.B., A.D.C., and D.S.E. edited and revised the manuscript; J.J.W., C.J.R., V.S., J.R., M.S., P. Jacobson, P. Jung, R.B., A.D.C., and D.S.E. approved the final version of the manuscript; P. Jacobson, A.D.C., and D.S.E. contributed to the conception and design of the research.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alberts P, Nilsson C, Selen G, Engblom LO, Edling NH, Norling S, Klingström G, Larsson C, Forsgren M, Ashkzari M, Nilsson CE, Fiedler M, Bergqvist E, Ohman B, Björkstrand E, Abrahmsen LB. Selective inhibition of 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 improves hepatic insulin sensitivity in hyperglycemic mice strains. Endocrinology 144: 4755–4762, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anagnostis P, Athyros VG, Tziomalos K, Karagiannis A, Mikhailidis DP. Clinical review: The pathogenetic role of cortisol in the metabolic syndrome: a hypothesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94: 2692–2701, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Andrew R, Smith K, Jones GC, Walker BR. Distinguishing the activities of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases in vivo using isotopically labeled cortisol. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87: 277–285, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Basu R, Basu A, Grudzien M, Jung P, Jacobson P, Johnson M, Singh R, Sarr M, Rizza RA. Liver is the site of splanchnic cortisol production in obese nondiabetic humans. Diabetes 58: 39–45, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Basu R, Chandramouli V, Dicke B, Landau B, Rizza R. Obesity and type 2 diabetes impair insulin-induced suppression of glycogenolysis as well as gluconeogenesis. Diabetes 54: 1942–1948, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Basu R, Edgerton DS, Singh RJ, Cherrington A, Rizza RA. Splanchnic cortisol production in dogs occurs primarily in the liver: evidence for substantial hepatic specific 11beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 activity. Diabetes 55: 3013–3019, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Basu R, Schwenk WF, Rizza RA. Both fasting glucose production and disappearance are abnormal in people with “mild” and “severe” type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 287: E55–E62, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Basu R, Singh RJ, Basu A, Chittilapilly EG, Johnson CM, Toffolo G, Cobelli C, Rizza RA. Splanchnic cortisol production occurs in humans: evidence for conversion of cortisone to cortisol via the 11-beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (11beta-hsd) type 1 pathway. Diabetes 53: 2051–2059, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bratusch-Marrain PR. Insulin-counteracting hormones: their impact on glucose metabolism. Diabetologia 24: 74–79, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chiasson JL, Shikama H, Chu DT, Exton JH. Inhibitory effect of epinephrine on insulin-stimulated glucose uptake by rat skeletal muscle. J Clin Invest 68: 706–713, 1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Corporeau C, Foll CL, Taouis M, Gouygou JP, Berge JP, Delarue J. Adipose tissue compensates for defect of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase induced in liver and muscle by dietary fish oil in fed rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290: E78–E86, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cowan JS, Hetenyi G., Jr Glucoregulatory responses in normal and diabetic dogs recorded by a new tracer method. Metabolism 20: 360–372, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Pirro R, Bertoli A, Fusco A, Testa I, Greco AV, Lauro R. Effect of dexamethasone and cortisone on insulin receptors in normal human male. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 51: 503–507, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dimitriadis G, Leighton B, Parry-Billings M, Sasson S, Young M, Krause U, Bevan S, Piva T, Wegener G, Newsholme EA. Effects of glucocorticoid excess on the sensitivity of glucose transport and metabolism to insulin in rat skeletal muscle. Biochem J 321: 707–712, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dunbar JC, Schultz S, Houser F, Walker J. Regulation of the hepatic response to glucagon: role of insulin, growth hormone and cortisol. Horm Res 31: 244–249, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Edgerton DS, Basu R, Ramnanan CJ, Farmer TD, Neal D, Scott M, Jacobson P, Rizza RA, Cherrington AD. Effect of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-1 inhibition on hepatic glucose metabolism in the conscious dog. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 298: E1019–E1026, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Edgerton DS, Cardin S, Emshwiller M, Neal D, Chandramouli V, Schumann WC, Landau BR, Rossetti L, Cherrington AD. Small increases in insulin inhibit hepatic glucose production solely caused by an effect on glycogen metabolism. Diabetes 50: 1872–1882, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Edgerton DS, Cardin S, Neal D, Farmer B, Lautz M, Pan C, Cherrington AD. Effects of hyperglycemia on hepatic gluconeogenic flux during glycogen phosphorylase inhibition in the conscious dog. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 286: E510–E522, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Edgerton DS, Jacobson PB, Opgenorth TJ, Zinker B, Beno D, von Geldern T, Ohman L, Scott M, Neal D, Cherrington AD. Selective antagonism of the hepatic glucocorticoid receptor reduces hepatic glucose production. Metabolism 55: 1255–1262, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Edgerton DS, Ramnanan CJ, Grueter CA, Johnson KM, Lautz M, Neal DW, Williams PE, Cherrington AD. Effects of insulin on the metabolic control of hepatic gluconeogenesis in vivo. Diabetes 58: 2766–2775, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Eigler N, Sacca L, Sherwin RS. Synergistic interactions of physiologic increments of glucagon, epinephrine, and cortisol in the dog: a model for stress-induced hyperglycemia. J Clin Invest 63: 114–123, 1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Exton JH, Friedmann N, Wong EH, Brineaux JP, Corbin JD, Park CR. Interaction of glucocorticoids with glucagon and epinephrine in the control of gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis in liver and of lipolysis in adipose tissue. J Biol Chem 247: 3579–3588, 1972 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fujiwara T, Cherrington AD, Neal DN, McGuinness OP. Role of cortisol in the metabolic response to stress hormone infusion in the conscious dog. Metabolism 45: 571–578, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goldstein RE, Wasserman DH, McGuinness OP, Lacy DB, Cherrington AD, Abumrad NN. Effects of chronic elevation in plasma cortisol on hepatic carbohydrate metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 264: E119–E127, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gustavson SM, Chu CA, Nishizawa M, Farmer B, Neal D, Yang Y, Donahue EP, Flakoll P, Cherrington AD. Interaction of glucagon and epinephrine in the control of hepatic glucose production in the conscious dog. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 284: E695–E707, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hsieh PS, Moore MC, Neal DW, Emshwiller M, Cherrington AD. Rapid reversal of the effects of the portal signal under hyperinsulinemic conditions in the conscious dog. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 276: E930–E937, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Itoh E, Iida K, Kim DS, Del Rincon JP, Coschigano KT, Kopchick JJ, Thorner MO. Lack of contribution of 11betaHSD1 and glucocorticoid action to reduced muscle mass associated with reduced growth hormone action. Growth Horm IGF Res 14: 462–466, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Iwasaki Y, Takayasu S, Nishiyama M, Tsugita M, Taguchi T, Asai M, Yoshida M, Kambayashi M, Hashimoto K. Is the metabolic syndrome an intracellular Cushing state? Effects of multiple humoral factors on the transcriptional activity of the hepatic glucocorticoid-activating enzyme (11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1) gene. Mol Cell Endocrinol 285: 10–18, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Joharapurkar A, Dhanesha N, Shah G, Kharul R, Jain M. 11beta-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1: potential therapeutic target for metabolic syndrome. Pharmacol Rep 64: 1055–1065, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kannisto K, Pietiläinen KH, Ehrenborg E, Rissanen A, Kaprio J, Hamsten A, Yki-Järvinen H. Overexpression of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-1 in adipose tissue is associated with acquired obesity and features of insulin resistance: studies in young adult monozygotic twins. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89: 4414–4421, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kotelevtsev Y, Holmes MC, Burchell A, Houston PM, Schmoll D, Jamieson P, Best R, Brown R, Edwards CR, Seckl JR, Mullins JJ. 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 knockout mice show attenuated glucocorticoid-inducible responses and resist hyperglycemia on obesity or stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 14924–14929, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Krikorian A, Khan M. Is metabolic syndrome a mild form of Cushing's syndrome? Rev Endocr Metab Disord 11: 141–145, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lindsay RS, Wake DJ, Nair S, Bunt J, Livingstone DE, Permana PA, Tataranni PA, Walker BR. Subcutaneous adipose 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 activity and messenger ribonucleic acid levels are associated with adiposity and insulinemia in Pima Indians and Caucasians. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88: 2738–2744, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mari A, Stojanovska L, Proietto J, Thorburn AW. A circulatory model for calculating non-steady-state glucose fluxes. Validation and comparison with compartmental models. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 71: 269–281, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Masuzaki H, Paterson J, Shinyama H, Morton NM, Mullins JJ, Seckl JR, Flier JS. A transgenic model of visceral obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Science 294: 2166–2170, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Masuzaki H, Yamamoto H, Kenyon CJ, Elmquist JK, Morton NM, Paterson JM, Shinyama H, Sharp MG, Fleming S, Mullins JJ, Seckl JR, Flier JS. Transgenic amplification of glucocorticoid action in adipose tissue causes high blood pressure in mice. J Clin Invest 112: 83–90, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Molusky MM, Li S, Ma D, Yu L, Lin JD. Ubiquitin-specific protease 2 regulates hepatic gluconeogenesis and diurnal glucose metabolism through 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1. Diabetes 61: 1025–1035, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Moore MC, DiCostanzo CA, Dardevet D, Lautz M, Farmer B, Cherrington AD. Interaction of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor with insulin in the control of hepatic glucose uptake in conscious dogs. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 288: E556–E563, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Moore MC, DiCostanzo CA, Dardevet D, Lautz M, Farmer B, Neal DW, Cherrington AD. Portal infusion of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor enhances hepatic glucose disposal in conscious dogs. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 287: E1057–E1063, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Moore MC, Satake S, Lautz M, Soleimanpour SA, Neal DW, Smith M, Cherrington AD. Nonesterified fatty acids and hepatic glucose metabolism in the conscious dog. Diabetes 53: 32–40, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Morgan SA, Sherlock M, Gathercole LL, Lavery GG, Lenaghan C, Bujalska IJ, Laber D, Yu A, Convey G, Mayers R, Hegyi K, Sethi JK, Stewart PM, Smith DM, Tomlinson JW. 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 regulates glucocorticoid-induced insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. Diabetes 58: 2506–2515, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Morton NM. Obesity and corticosteroids: 11beta-hydroxysteroid type 1 as a cause and therapeutic target in metabolic disease. Mol Cell Endocrinol 316: 154–164, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Morton NM, Paterson JM, Masuzaki H, Holmes MC, Staels B, Fievet C, Walker BR, Flier JS, Mullins JJ, Seckl JR. Novel adipose tissue-mediated resistance to diet-induced visceral obesity in 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1-deficient mice. Diabetes 53: 931–938, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nuttall FQ, Ngo A, Gannon MC. Regulation of hepatic glucose production and the role of gluconeogenesis in humans: is the rate of gluconeogenesis constant? Diabetes Metab Res Rev 24: 438–458, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pagliassotti MJ, Holste LC, Moore MC, Neal DW, Cherrington AD. Comparison of the time courses of insulin and the portal signal on hepatic glucose and glycogen metabolism in the dog. J Clin Invest 97: 81–91, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Paterson JM, Morton NM, Fievet C, Kenyon CJ, Holmes MC, Staels B, Seckl JR, Mullins JJ. Metabolic syndrome without obesity: Hepatic overexpression of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 7088–7093, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Qi D, Rodrigues B. Glucocorticoids produce whole body insulin resistance with changes in cardiac metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292: E654–E667, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ramnanan CJ, Saraswathi V, Smith MS, Donahue EP, Farmer B, Farmer TD, Neal D, Williams PE, Lautz M, Mari A, Cherrington AD, Edgerton DS. Brain insulin action augments hepatic glycogen synthesis without suppressing glucose production or gluconeogenesis in dogs. J Clin Invest 121: 3713–3723, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rizza RA. Pathogenesis of fasting and postprandial hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: implications for therapy. Diabetes 59: 2697–2707, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rizza RA, Mandarino LJ, Gerich JE. Cortisol-induced insulin resistance in man: impaired suppression of glucose production and stimulation of glucose utilization due to a postreceptor detect of insulin action. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 54: 131–138, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Satake S, Moore MC, Igawa K, Converse M, Farmer B, Neal DW, Cherrington AD. Direct and indirect effects of insulin on glucose uptake and storage by the liver. Diabetes 51: 1663–1671, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schaeffer LD, Chenoweth M, Dunn A. Adrenal corticosteroid involvement in the control of liver glycogen phosphorylase activity. Biochim Biophys Acta 192: 292–303, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shamoon H, Hendler R, Sherwin RS. Synergistic interactions among antiinsulin hormones in the pathogenesis of stress hyperglycemia in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 52: 1235–1241, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Steele R, Wall JS, DeBodo RC, Altszuler N. Measurement of size and turnover rate of body glucose pool by the isotope dilution method. Am J Physiol 187: 15–24, 1956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Stimson RH, Andrew R, McAvoy NC, Tripathi D, Hayes PC, Walker BR. Increased whole-body and sustained liver cortisol regeneration by 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 in obese men with type 2 diabetes provides a target for enzyme inhibition. Diabetes 60: 720–725, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tomlinson JW, Walker EA, Bujalska IJ, Draper N, Lavery GG, Cooper MS, Hewison M, Stewart PM. 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1: a tissue-specific regulator of glucocorticoid response. Endocr Rev 25: 831–866, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Torrecilla E, Fernández-Vázquez G, Vicent D, Sánchez-Franco F, Barabash A, Cabrerizo L, Sánchez-Pernaute A, Torres AJ, Rubio MA. Liver upregulation of genes involved in cortisol production and action is associated with metabolic syndrome in morbidly obese patients. Obes Surg 22: 478–486, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Walker BR. Extra-adrenal regeneration of glucocorticoids by 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1: physiological regulator and pharmacological target for energy partitioning. Proc Nutr Soc 66: 1–8, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Walker BR, Andrew R. Tissue production of cortisol by 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 and metabolic disease. Ann NY Acad Sci 1083: 165–184, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Weissman C. The metabolic response to stress: an overview and update. Anesthesiology 73: 308–327, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zhang M, Lv XY, Li J, Xu ZG, Chen L. Alteration of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 in skeletal muscle in a rat model of type 2 diabetes. Mol Cell Biochem 324: 147–155, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]