Abstract

Background:

While the use of functional knee braces for return to sports or high level physical activity after ACL reconstruction (ACLR) is controversial, brace use is still prevalent.1,2,3,4,5 All active patients in the practice are braced after ACLR and must pass a battery of sports tests before they return to play in their brace. Criteria include a 90% score on 4 one‐legged hop tests9 burst superimposition strength test,10 Knee Outcome Survey Activities of Daily Living Scale,8 and a global rating of knee function.

Purpose:

The purpose of this study was to describe the use of criterion‐based guidelines to determine if athletes who had undergone an ACLR function better with or without their functional brace, one year after surgery.

Study Design:

Cross‐Sectional Study

Methods:

Sixty‐four patients post ACLR performed 4 one‐legged hop tests,9 burst superimposition strength test,10 and completed the Knee Outcome Survey Activities of Daily Living Scale,8 and a global rating of knee function one year after surgery with and without their brace.

Results:

Participants included 35 men and 29 women with a mean age of 25 years. The Mean Knee Outcome Survey Activities of Daily Living score was 98%, and the global rating was 97%. Of the subjects, one patient failed hop testing by at least one criterion with and without the brace. Three additional patients failed the test while braced but passed un‐braced, and one patient passed with the brace, but failed without the brace. Subjects performed significantly better un‐braced than braced in all hop tests: single leg hop braced = 101%; un‐braced = 107% (p<0.001); cross‐over hop braced = 100%; un‐braced = 105% (p<0.001); triple hop braced = 99%; un‐braced = 101% (p=0.003); timed hop braced = 98%; un‐braced = 103% (p = 0.004).

Conclusions:

Sixty‐two of 64 patients continued to score above return to play criteria one year after ACLR. All but two subjects in the cohort performed better un‐braced than braced. Based on the criterion set for this testing session, 62/64 individuals performed well enough to discontinue use of their brace.

Level of Evidence:

2b

Keywords: ACL, functional brace, hop tests, knee

INTRODUCTION

While the use of functional knee braces for return to sports or high level physical activity after ACL reconstruction (ACLR) is controversial, brace use is still prevalent.1,2,3,4,5 Brace sales remain strong despite conflicting evidence regarding their use and the fact that most physicians that recommend bracing advise their use for the first post‐operative year.

Decoster and Vailas reported on a survey of members of the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine (AOSSM), to identify the prescription patterns for ACL bracing at that time. Eighty seven percent of all respondents prescribed functional braces post‐ACLR. Of those, 52% of the respondents reported the patient's sport or activity level as the number one indicator regarding whether to prescribe a brace to their patients after ACLR. Once a patient receives a brace the majority of physicians indicated they prescribed wear durations of 9‐12 months, while another 20% prescribed beyond 12 months.5

All patients who participated in the current study used an immobilizer for the first 2‐3 weeks after ACLR. They transitioned to a functional knee brace when their effusion was ≤2+6 and a proper fit of the custom or off‐the‐shelf brace could be achieved for return to activity. Rehabilitation consisted of a combination of open and closed kinetic chain therapeutic exercise, neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) as previously described by Snyder‐Mackler and others,7,8,9 manual therapy for ROM/flexibility, and modalities for pain management. Prior to return to sport (RTS) all braced patients were progressed through a running and agility program wearing their functional brace, and had to pass a battery of sports tests in the brace. The criteria for RTS7,8,9 required that patients had symmetrical ROM, minimal effusion ≤1+,6 and scores greater than or equal to 90% on the following: a burst superimposition strength test of the quadriceps,12 4 one‐legged hop tests as described by Noyes et al,11 a Knee Outcome Survey – Activities of Daily Living Scale (KOS‐ADLS),10 and a Global Rating Score (GRS) of knee function.14 Patients were asked to wear their functional knee braces for any running or sports related activity for the first post‐operative year. All patients post‐ACLR are reminded to return 12 months after surgery for a re‐evaluation, which includes the same previously mentioned tests in the same order with the addition of performing the one‐legged hop tests without the brace.

To the best of the authors' knowledge there is no evidence in the literature to assist the clinician in determining when a patient can discontinue the use of a functional knee brace, when prescribed. The authors' criterion for discontinuing the brace is when the patient in the unbraced condition can perform equal to or better than the braced condition, on the hop tests and functional questionnaires listed above. By performing equally with and without the brace it was inferred that the brace is no longer providing the patient with assistance in control of their knee and that the brace may actually be a hindrance to their functional performance and confidence in their knee.

The purpose of this study was to describe the use of criterion‐based guidelines to determine if athletes who had undergone an ACLR function better with or without their functional brace, one year after surgery. The authors hypothesized that the majority of patients would demonstrate equal functional performance with and without the brace one year after ACLR.

METHODS

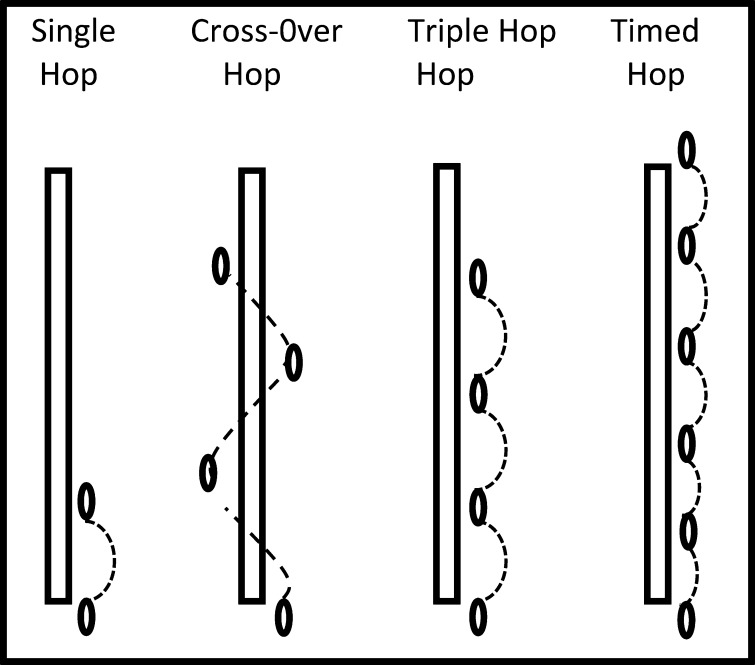

All patients who underwent ACLR were encouraged to schedule follow‐up testing one year post‐op, per the protocol of the surgeon. In a consecutive sample of convenience, sixty‐four subjects completed the one‐year post‐op testing. All subjects in the study were athletes participating in greater than 50 hours per year of level I sports (eg, football, basketball, soccer) or level II sports (eg, racquet sports, skiing) or manual labor occupations.13 All subjects underwent either a double loop semitendinosis‐gracilis autograft or allograft ACLR by a single surgeon. All subjects received formal physical therapy in the first three months after surgery, and subsequently passed a return to sports battery of tests in their brace at an average of 6 months post‐surgery as described previously by Adams et al.9 Injured and uninjured limb quadriceps strength was assessed with maximal volitional isometric contraction (MVIC) testing utilizing a burst superimposition technique as described previously.12 Functional hop testing was conducted using the protocol described by Noyes et al and shown in Figure 1.11 The testing protocol included two practice trials on each limb prior to the two test trials for each of the four hop test conditions. Subjects were allowed a brief rest period between trials as the subject felt was necessary, typically < 30 seconds. The test trials on each limb were averaged, and a limb symmetry index (LSI) was calculated for each test ([injured side score/uninjured side score] × 100) except for the timed hop test as the equation needs to be inverted to account for faster times comprising better scores ([uninjured side score/injured side score] × 100).11 Upon completion of the tests with the brace on, the braced LE was re‐tested without the brace. Immediately after completing the hop testing protocol, self‐assessed knee function was reported using the KOS‐ADLS and a GRS. The KOS‐ADLS consists of 14 items with 6 possible answers (each answer weighted from 0‐5 points) ranging from “not limited or symptomatic” to “unable to perform the task”, that evaluate symptoms and functional abilities during a variety of daily activities. A score of 100% equates to no symptoms or limitations during activities of daily living.10 The KOS‐ADLS has been established as a valid and reliable tool for evaluating changes in knee function over time. The GRS of knee function is a single number between 0% and 100% that requires subjects to rate their current functional status, including sports activities, compared to pre‐injury status. A score of 100% represents a full return to pre‐injury activity levels.14

Figure 1.

Noyes Hop Test Series.

DATA ANALYSIS

Descriptive statistics were determined for age, the KOS‐ADLS and GRS. Paired t‐test were used to compare the mean braced LSI to the mean un‐braced LSI for each hop test performed (alpha level of 0.05). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows, Version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

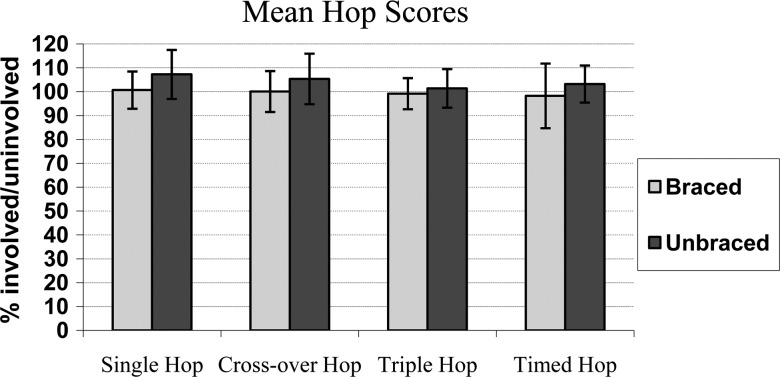

RESULTS

Subjects included 35 men and 29 women with a mean age of 24.62 years and a range from 15 to 47 years of age. Means and standard deviations to describe the subject's age and scores on functional outcome measures are reported in Table 1. The authors' return to play criterion‐based guidelines are described in Table 2. The mean perceived level of function on both questionnaires for all patients one‐year after ACLR surgery remained above the return to play criteria of 90%. In comparing the paired means and the paired differences of the four hop tests, subjects demonstrated better results in the un‐braced condition for all trials (Figure 2 and Table 3).

Table 1.

Demographics.

| N | Mean | Median | Std. Deviation | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs.) | 64 | 24.62 | – | 9.221 | 15‐47 |

| Quadriceps LSI (%)* | 47 | 100.4 | 97 | 10.590 | 88‐132 |

| KOS‐ADL (%)† | 63 | 97.54 | 99 | 3.801 | 81‐100 |

| GRS (%)†† | 63 | 96.78 | 99 | 4.654 | 80‐100 |

Quadriceps LSI was not included on all subjects' data forms as this criteria needed to be met prior to the hop testing.

Knee Outcome Scale‐Activities of Daily Living10

Global Rating Scale14

Table 2.

Return to Play Criteria.

| Criteria | Score |

|---|---|

| Quadriceps MVIC (in volved/uninvolved) | ≥90% |

| All Hop Tests (LSI) | ≥90% |

| Knee Outcomes Score ‐ ADL's | ≥90% |

| Global Rating Score | ≥90% |

Figure 2.

Mean Hop Scores of all 4 hop tests described by Noyes. All hops were performed in the braced condition prior to the unbraced condition.

Table 3.

Paired braced vs. unbraced hop test mean differences.

| Pairs | Hop Test (mean ± SD) | 95% CI | t Value | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Braced/Unbraced Single Hop | −6.570 ± 7.156 | −8.358; −4.783 | −7.345 | <.001 |

| Braced/Unbraced Cross Over Hop | −5.278 ± 7.229 | −7.098;−3.457 | −5.795 | <.001 |

| Braced/Unbraced Triple Hop | −2.226 ± 5.767 | −3.690;−.761 | −3.039 | <.01 |

| Braced/Unbraced Timed Hop | −4.947 ± 12.894 | −8.221;−1.672 | −3.021 | <.01 |

One subject failed hop testing at one year post‐op both with and without the brace, after having passed at 6 months after surgery. Three additional subjects failed the test while braced, but passed un‐braced, and one patient passed with the brace, but failed without the brace.

DISCUSSION

Criterion‐based functional testing revealed maintenance of successful RTP criteria for 62/64 individuals. This resulted in the recommendation to discontinue brace use at this time interval, one year after ACLR. All patients were back to their premorbid level of function, after passing the RTS criteria on average of 6 months post‐operatively. All test trials compared the involved to the uninvolved, first in the braced condition and second in the un‐braced condition. The results demonstrated that the vast majority of patients one year after ACLR have the strength, confidence, and control of their knee to perform at least at an equivalent level as their uninjured lower extremity (LE). Overall, subjects were able to hop significantly farther and faster without a brace on their involved knee during all hop tests. All but one subject continued to score above the return to sport criteria at one year post‐op, and only two subjects did better braced than un‐braced.

Athletes were recommended to discontinue use of their brace because the brace could actually become a hindrance to their function, based on their test results. Reductions in strength and ROM have been noted in patients when wearing a functional brace in previous studies.15,16 This is even more of a concern when considering the patient who continues to wear a knee brace that may no longer be indicated. Risberg and colleagues have reported significant weakness in the quadriceps muscle in subjects who wore their functional braces for a period of time of greater than one year.17 Testing the patients at one year post‐op without a brace was the agreed upon time period amongst the clinical staff and the surgeon referring the patients, based upon a lack of consensus evidence to support earlier discontinuation, other than surgeon preference.5 By studying this group it was expected that the majority of the patients would be able to succeed without a brace one year after surgery, and hopefully prevent such complications that could arise related to quadriceps weakness.

The controversy regarding whether to use a functional brace post ACLR will continue as long as there are concerns about the strength of the graft and its' ability to withstand the stresses placed upon it during the first post‐operative year and as an athlete returns to high‐level sports. However, for those clinicians who brace their patients, the criterion provided by the authors could be used to objectively support clinical decisions for return to play with or without the brace at one year post‐op. If patients scored ≥ to 90% in the assessment of strength of the quadriceps compared to their uninvolved leg, on the KOS‐ADL score and GRS, and scored better in the 4 hop tests described by Noyes without their brace than with their brace, then the athlete was considered ready to discontinue the use of a functional brace for high‐level activity.

Successful completion of these proposed criterion can assist physicians and physical therapists performing pre‐employment screens, evaluating patients whose brace no longer fits or is damaged, and in trying to answer the patient's question as to when they can discontinue using it.

Limitations of this study include a possible order effect and the lack of a randomized control group. The order of the testing was always two practice trials followed by two testing trials with the uninvolved leg tested first and the braced condition being performed prior to the un‐braced condition. The concern regarding this sequence is the potential for increase in confidence and possible physiologic changes may occur with increased activity, which may have played a role in the outcomes of the study. There is also the issue that a hop test with and without the brace was not performed any earlier than one year post‐op. Therefore, the authors do not know if subjects could have succeeded in passing the criterion at an earlier point in time. It was determined during this study that there would have been benefit to collecting qualitative data about which patients had actually been compliant (and to what level) with wearing their brace during sports activities between their testing sessions. Not having this data is a limitation in understanding why patients may have done better without their brace at the 1‐year postoperative testing period.

No subjects injured their involved knee while testing without the brace. Based on these results, the authors recommend further research on 1) whether or not patients can safely return to sport without their brace earlier than one year post‐op, and 2) patient compliance with brace wear during the time when they are supposed to be utilizing it. There is no consensus as to when the graft is equivalent to the normal ACL with regard to stress to ultimate failure and linear stiffness. A case study by Beynnon and colleagues suggests load to ultimate failure and linear stiffness approaches that of the contralateral ACL by 8 months post‐op.18 The next step could be to look at what time after surgery it is possible for patients to pass the return to sports criteria without their brace. Other research could consider whether there are additional factors that need to be evaluated for criterion for RTS without a brace, such as if the sport is a high impact/contact activity.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, all but one patient in the cohort performed significantly better in the un‐braced than braced condition at one year post ACLR, as determined by functional hop testing. Their subjective outcome reports remained high (>90%) at one year after ACLR, indicative of excellent function. When combined, these outcomes indicate that this cohort of subjects was able to discontinue brace use based upon the established criterion for RTS used by the authors.

References

- 1.McDevitt ER, Taylor DC, Miller MD, et al. Functional bracing after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective, randomized, multicenter study. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(8):1887–1892 PMID: 15572317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sterett WI, Briggs KK, Farley T, et al. Effect of functional bracing on knee injury in skiers with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(10):1581–1585 PMID: 16870823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kruse LM, Gray B, Wright RW. Rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(19):1737–1748 PMID: 23032584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delay BS, Smolinski RJ, Wind WM, et al. Current practices and opinions in ACL reconstruction and rehabilitation: results of a survey of the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine. Am J Knee Surg. 2001;14(2):85–91 PMID: 11401175 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Decoster LC, Vailas JC. Functional anterior cruciate ligament bracing: a survey of current brace prescription patterns. Orthopedics. 2003;26(7):701–706; discussion 706 PMID: 12875565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sturgill LP, Snyder-Mackler L, Manal TJ, et al. Interrater reliability of a clinical scale to assess knee joint effusion. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39(12):845–849 PMID: 20032559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snyder-Mackler L, Delitto A, Bailey SL, et al. Strength of the quadriceps femoris muscle and functional recovery after reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. A prospective, randomized clinical trial of electrical stimulation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(8):1166–1173 PMID: 7642660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manal TJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Practice guidelines for anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation: a criterion-based rehabilitation progression. Operative Techniques in Orthopaedics. 1996;6(3):190–196 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams D, Logerstedt D, Hunter-Giordano A, et al. Current concepts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a criterion-based rehabilitation progression. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(7):601–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irrgang JJ, Snyder-Mackler L, Wainner RS, et al. Development of a patient-reported measure of function of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(8):1132–1145 PMID: 9730122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noyes FR, Barber SD, Mangine RE. Abnormal lower limb symmetry determined by function hop tests after anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(5):513–518 PMID: 1962720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snyder-Mackler L, De Luca PF, Williams PR, et al. Reflex inhibition of the quadriceps femoris muscle after injury or reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76(4):555–560 PMID: 8150823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daniel DM, Stone ML, Dobson BE, et al. Fate of the ACL-injured patient: A prospective outcome study. Am J Sports Med. 1994; 22(5):632–644 PMID:7810787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzgerald GK, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. The efficacy of perturbation training in non-operative anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation programs for physical active individuals. PhysTher. 2000; 80(2):128–140 PMID: 10654060 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Houston ME, Goemans PH. Leg muscle performance of athletes with and without knee support braces. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1982;63(9):431–432 PMID: 7115043 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knutzen KM, Bates BT, Hamill J. Electrogoniometry of post-surgical knee bracing in running. Am J Phys Med. 1983;62(4):172–181 PMID: 6881314 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Risberg MA, Holm I, Steen H, et al. The effect of knee bracing after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A prospective, randomized study with two years' follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(1):76–83 PMID: 9934423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beynnon BD, Risberg MA, Tjomsland Ole, et al. Evaluation of knee joint laxity and the structural properties of the anterior cruciate ligament graft in the human a case report. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(2):203–206 PMID: 9079174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]