Abstract

Rationale

Despite its high level of effectiveness, initial acceptance of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and regular use in patients with obstructive sleep apneoa syndrome (OSAS) are still an issue. Alternatively, oral appliances (OAs) can be recommended. To improve patient engagement in their treatment, physicians are advised to take into account patient preferences and to share the therapeutic decision. We aimed to determine patients’ preferences for OSAS treatment-related attributes, and to predict patients’ demand for both CPAP and OAs.

Methods

A discrete choice experiment (DCE) was performed in 121 newly diagnosed patients consecutively recruited in a sleep unit.

Results

Regression parameters were the highest for impact on daily life and effectiveness ahead of side effects. In the French context, the demanding probabilities for CPAP and OAs were 60.2% and 36.2%, respectively. They were sensitive to the variation in the amount of out-of-pocket expenses for both CPAP and OAs.

Conclusions

This first DCE in OSAS emphasises the importance to communicate with patients before the implementation of treatment.

Keywords: Health Economist, Sleep apnoea

Introduction

Following the most recent guidelines, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is indicated as a first-line treatment for patients suffering from obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS).1 However, initial acceptance and regular use of CPAP treatment are still an issue.2 Alternatively, oral appliances (OAs) are recommended in case of initial refusal or failure of CPAP option, and also as a first-line treatment in mild to moderate OSAS.1 Because of problems of compliance, patients and physicians are faced with difficult decisions regarding which OSAS treatment options to choose. Physicians are encouraged to take into account patients’ preferences, and possibly to involve them in the medical decision making.3 We used a preferences elicitation method, namely the discrete choice experiment (DCE),4 to determine patients’ preferences for OSAS treatment-related attributes, and to predict patients’ demand for both CPAP and OAs.

Methods

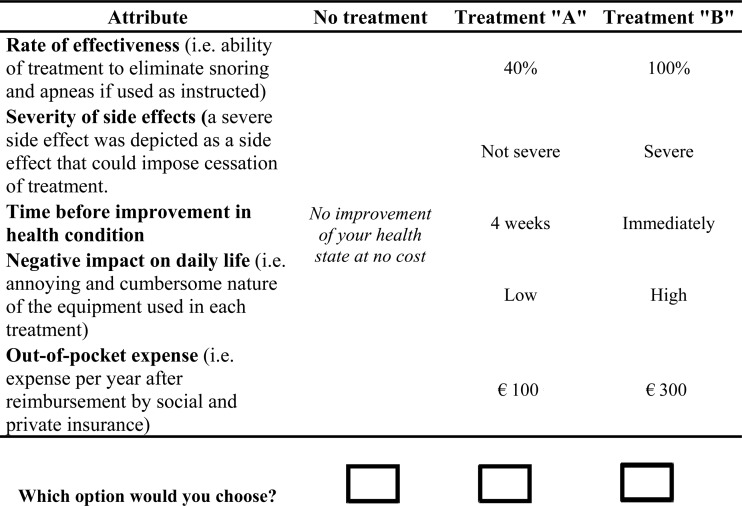

Five attributes were used to describe treatment options.5 The choice tasks were based on a paired comparison format and included an opt-out option (ie, no treatment) (figure 1). We used an experimental design with 16 choice tasks randomly allocated into two versions of eight tasks each. The two versions were randomly administered by a nurse to 121 patients newly diagnosed with OSAS and recruited consecutively in a French hospital sleep unit (67.8% were males, 53.5±12 years old (mean±SD), with a body mass index of 29.3±5.65 and an apnoea–hypopnoea index of 41.5±22.4). Patients’ choices led to 2904 observations from which preferences were estimated by logistic regression.

Figure 1.

Illustration of a choice task.

To predict patients’ demand for both CPAP and OAs, we assumed CPAP (OA) treatment to be 100% (40%) effective, with non-severe (severe) side effects, no time (4 weeks) to wait before improvement, with a high (low) negative impact on daily life and €378 (€233) out-of-pocket expense per year (in the French context).

Results

All the estimates of the model were significant and of the expected sign. Patients preferred a high rate of effectiveness, non-severe side effects, a short time to wait before treatment to be effective, a low negative impact on daily life and a less expensive treatment. ‘Negative impact on daily life’ was the most influential attribute on the patients’ choices. Its relative impact was twice larger than that of the second most influential attribute, which was the ‘effectiveness’ attribute (table 1).

Table 1.

Nested logit model estimates and impact analysis (n=2904 observations)

| Effect | Estimate (SE) | Partial effect* | Relative effect (%)† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment (A) | 0.024 (0.186) | – | – |

| (No) treatment | −0.964 (0.483)‡ | – | – |

| Rate of effectiveness | 1.065 (0.280)‡ | −62.7 | 25.9 |

| (ref: 40%) | |||

| Severity of side effects | 0.635 (0.202)‡ | −21.6 | 8.9 |

| (ref: severe) | |||

| Time before improvement | 0.412 (0.133)‡ | −8.9 | 3.7 |

| (ref: 4 weeks) | |||

| Negative impact on daily life (ref: high) | 1.586 (0.428)‡ | −141.7 | 58.6 |

| Out-of-pocket expense (continuous variable) | −0.004 (0.001)‡ | −6.9 | 2.9 |

Log likelihood (LL) of ‘full’ model=−662.3; LL of ‘null’ model=−420.5.

*Partial effect=LL of the model including only the attribute; LL of the ‘null’ model.

†Relative effect=100×(partial effect/(LL of ‘full’ model; LL of ‘null’ model)).

‡Estimated parameter significantly different from zero for a 5% α-risk.

In the French context, the demanding probabilities for CPAP and OAs were 60.2% and 36.2%, respectively. They were sensitive to the variation in the amount of out-of-pocket expense for both CPAP and OAs.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study that used the DCE method to measure patients’ preferences for OSAS treatments. Because it was a single-centre study which took place in one healthcare system in which public insurance covers 65% of treatment cost (ie, in France), we should be cautious with the generalisability of the results. This DCE in OSAS emphasises the importance of communicating with patients before the implementation of treatment, since effectiveness of treatment and impact on daily life constitutes the most important factors of choice ahead of side effects. However, these preferences could be threatened by the high level of out-of-pocket expenses. Further research is needed to investigate more specifically how financial constraint can influence patients’ preferences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Anne Campana for her assistance and seriousness in monitoring the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have made important contributions in the discussion and drafting of the article.

Competing interests: BF is consultant for a French company developing and selling oral appliance devices (Orthosom).

Ethical approval: This survey was approved by the ‘Comité de Protection des Personnes Ile de France V’ (number 10815, 7 September 2010).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Open Access: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 3.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/

References

- 1.Kushida CA, Morgenthaler TI, Littner MR, et al. Practice parameters for the treatment of snoring and obstructive sleep apnea with oral appliances: an update for 2005. Sleep 2006;29:240–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pepin JL, Krieger J, Rodenstein D, et al. Effective compliance during the first 3 months of continuous positive airway pressure. A European prospective study of 121 patients. Am J Respir Crit Med 1999;160:1124–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med 1999;49:651–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryan M, Scott DA, Reeves C, et al. Eliciting public preferences for healthcare: a systematic review of techniques. Health Technol Assess 2001;5:1–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pelletier-Fleury N, Gafni A, Krucien N, et al. The development and testing of a new communication tool to help clinicians inform patients with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS) about treatment options. J Sleep Res 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2012.01015.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.