Abstract

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress contributes to acute kidney injury induced by several causes. Kidney dysfunction was shown to be influenced by gender differences. In this study we observed differences in the severity of kidney injury between male and female mice in response to tunicamycin, an ER stress agent. Tunicamycin-treated male mice showed a severe decline in kidney function and extensive kidney damage of proximal tubules in the kidney outer cortex (S1 and S2 segments). Interestingly, female tunicamycin-treated mice did not show a decline in kidney function, and their kidneys showed damage localized primarily to proximal tubules in the inner cortex (S3 segment). Protein markers of ER stress, glucose-regulated protein, and X-box binding protein 1 were also more elevated in male mice. Similarly, the induction of apoptosis was higher in tunicamycin-treated male mice, as measured by the activation of Bax and caspase-3. Testosterone administered to female mice before tunicamycin resulted in a phenotype similar to male mice with a comparable decline in renal function, tissue morphology, and induction of ER stress markers. We conclude that kidneys of male mice are much more susceptible to ER stress-induced acute kidney injury than those of females. Moreover, this sexual dimorphism could provide an interesting model to study the relation between kidney function and injury to a specific nephron segment.

Keywords: sex differences, endoplasmic reticulum stress, tunicamycin, acute kidney injury, outer cortex, inner cortex

acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common serious health problem with high mortality (4, 6, 13). There is accumulating evidence that gender differences may contribute to differential injury response in patients with AKI (5, 22). Similarly, animal models of ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) and nephrotoxic AKI showed gender differences in the response to injury (19, 25, 26, 32). Several reports demonstrated that endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress contributes to the development of AKI in humans and in animal models of AKI (10, 24, 27). The reason for this sexual dimorphism is not clear, and it is unknown whether gender differences also exist in an ER stress model of AKI. In this study, we investigated gender differences to kidney injury in response to ER stress in a mouse model of tunicamycin-induced AKI.

ER stress is induced by accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER (29). In mammalian cells three major ER sensors are activated by unfolded proteins: double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase-like ER kinase (PERK), activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), and inositol-requiring kinase 1 (IRE1). When ER stress is induced, these sensors initiate an unfolded protein response (UPR), which serves as an adaptive response but can cause apoptosis in cells when the stress is severe (29).

Upon activation, PERK activation causes general reduction of protein synthesis, thus decreasing the protein load on the ER. The PERK pathway can also induce expression of ER chaperones, such as the immunoglobulin heavy chain-binding protein BiP (also called GRP78) (3). The ATF6 pathway is also activated by ER stress to induce transcription of ER-associated degradation factors and ER chaperones (8, 33). IRE activation causes splicing of X-box-binding protein 1 (XBP1). This generates a 371-amino acid protein (XBP1S) that acts as an active transcription factor. The spliced XBP1 form subsequently binds to ER stress response element and UPR element, leading to expression of target genes, including ER chaperone (BiP/GRP78) and proteins involved in degradation of unfolded proteins (2). BiP/GRP78 is a central modulator of ER stress. In normal, unstressed conditions, BiP binds to the ER luminal domains of the ER stress sensors and keeps them in an inactive state (1, 30). Under stress conditions, BiP binds to misfolded proteins and dissociates from the ER stress sensors, which become active and initiate UPR.

During prolonged ER stress, cell death signals are also initiated. C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) is a 29-kDa transcription factor induced by PERK and ATF6 pathways (16), leading to proapoptotic signaling (23, 28, 34). In addition to CHOP-mediated apoptosis, ER stress-induced cell death is mediated by caspase-dependent apoptosis and IRE1 apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1-c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (18, 21, 31).

Using a mouse model of tunicamycin-induced AKI, we demonstrate that male mice are much more susceptible (measured by functional parameters) to ER stress-induced AKI than females. The pattern of the morphological damage is also different between males and females after tunicamycin administration; damage is mainly in proximal tubules (PT) in the outer cortex of the kidney (S1 and S2 segments) in males, but it is primarily in PT in the inner cortex (S3 segment) of female animals. Pretreatment of female mice with testosterone altered the pattern of damage caused by tunicamycin similarly to that seen in male animals. Activation of Bax and caspase-3 was higher in male compared with female animals after tunicamycin, and male mice showed higher induction of ER stress markers such as BiP/GRP78 and XBP1. This sexual dimorphism in ER stress-induced AKI can be used as a model to investigate the relation between kidney function and injury to a specific nephron segment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse model of tunicamycin-induced AKI.

Experiments were performed on sibling 129Sv mice (10 to 12 wk old) that weighed 20–28 g. The mice were housed with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle and with free access to standard diet and water at the Veterinary Medical Unit at the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System (Little Rock, AR). Animals were killed painlessly with methods of death approved by the Panel on Euthanasia of the American Veterinary Medical Association. All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Central Arkansas Veterans Health Care System. Wild-type female and male mice were given a single 1 mg/kg body wt intraperitoneal injection of tunicamycin in 0.02 M sodium phosphate, pH 7.99, 150 mM glucose, and they were killed after 3 and 5 days. A group of female mice was pretreated with testosterone by subcutaneous implantation of a 5-mg (21-day release) testosterone pellet (A-151; Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL) for 2 wk before tunicamycin injection. Untreated (control) mice received diluent alone. The induction of AKI was monitored by following blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels in blood obtained by retroorbital bleeding at the time of death using kits from Biotron Diagnostics and Sigma Diagnostics.

Histology assessment.

At various times after tunicamycin, kidneys were removed, immersed in 4% neutral-buffered formaldehyde, and fixed for 48–72 h. The tissues were paraffin embedded and processed for light microscopy. Sections were cut at a thickness of 5 μm and stained with periodic acid-Schiff. The following parameters were chosen as indicative of morphological damage to the kidney after tunicamycin administration: S1 and S2 necrosis, S3 necrosis, cast formation, tubule dilatation, red blood cell extravasation, tubule degeneration, and inflammatory cell infiltration. These parameters were evaluated on a scale of 0 to 4, which ranged from not present (0), mild (1), moderate (2), severe (3), to very severe (4). Each parameter was determined on at least six different animals. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) was assessed by the two-tailed Student's t-test for independent samples.

Immunohistochemistry.

To detect XBP1 and CHOP/GADD153 expression in situ, kidney sections from untreated and 3 days tunicamycin-treated animals were incubated with monoclonal antibodies against XBP1 and CHOP/GADD153. The positive staining was visualized by avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex using the Vectastain ABC elite kit (Vector Laboratories) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RNA preparation and RT-PCR analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from fresh kidney tissues using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) as specified by the manufacturer. The concentration of total RNA was determined by spectrophotometry. XBP1 cDNA was reverse transcribed from 4 ng total RNA and then amplified using the Superscript III One Step RT-PCR with platinum Taq DNA polymerase kit (no. 12574-026) (http://www.jbc.org/cgi/redirect-inline?ad=Invitrogen; Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions. To amplify both the spliced and the unspliced variants of XBP1 cDNA, we used a pair of primers that span the spliced site (17). Mouse XBP1 primers were as follows: mXBP1.3S (5′-A AAC AGA GTA GCA GCG CAG ACT GC-3′) and mXBP1.12AS (5′-TC CTT CTG GGT AGA CCT CTG GGA G-3′). The PCR product was either untreated or digested by Pst1, analyzed by 8% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Detection of Bax activation by immunoprecipitation.

For the analysis of Bax activation, mouse kidneys were homogenized on ice in lysis buffer [40 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 120 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 1% CHAPS, and 1 mM EDTA supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors] using a Dounce homogenizer. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 9,200 g for 20 min. One milligram of lysate protein was precleared by incubation with 1 μg of normal mouse IgG coupled to 30 μl of protein G Dynabeads (Invitrogen). To the precleared supernatant, 5 μg of mouse monoclonal antibody to active Bax (6A7) (Enzo Life Sciences) coupled to 30 μl of protein G Dynabeads were added and then incubated for 2–4 h at 4°C. The immunoprecipitates were then washed five times using 200 μl [50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl] and then resuspended in 100 μl [50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl]. The immunoprecipitates were eluted in 40 μl 1× Laemmli buffer followed by boiling for 5 min. Samples were resolved using 12% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and blotted with Bax antibody (BD Biosciences).

Western blot.

For analysis of BiP/GRP78 and caspase-3 (full and cleaved) protein expression, harvested mouse kidneys were homogenized either in ice-cold Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) lysis buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, and 0.5% NP-40 supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors] or, for CHOP/GADD153 expression, in RIPA buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% NP-40, and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors], and cleared by centrifugation. Protein concentrations were determined using a Bio-Rad protein assay (Hercules, CA), and equal amounts of proteins were analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE. Electrophoresed samples were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody. After washing, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody was applied. Bound proteins to the secondary antibody were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). The primary antibodies used were BiP/GRP78 polyclonal antibody (Cell Signaling), CHOP/GADD153 (Cell Signaling), and caspase-3 polyclonal antibody (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA).

Statistical analysis.

All of the quantitative values are expressed as means ± SE as a representative of a group. Statistical significance between animal groups was done using analysis of variance and Student's t-test with two-tailed distribution. P values <0.05 were considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Gender differences in renal function and morphology after tunicamycin-induced AKI.

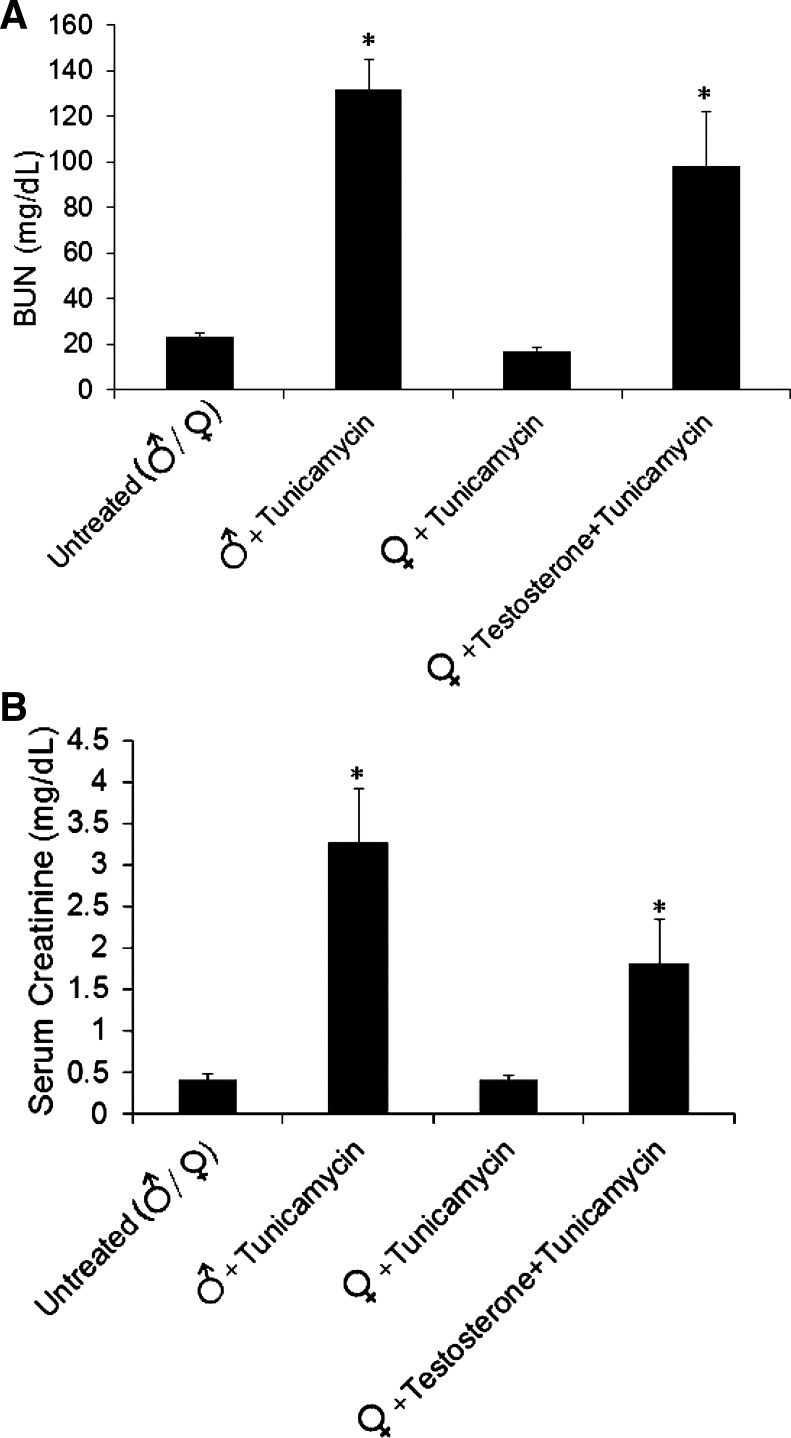

To study the effect of sex on ER stress-induced AKI, we used the tunicamycin-induced AKI model. Male and female mouse littermates were injected intraperitoneally with tunicamycin (1 mg/kg body wt). Untreated (control) mice received the same injection of diluent alone. Also, some female mice were pretreated with testosterone pellets (5 mg) for a period of 14 days, and, at that time, tunicamycin was injected. There were no functional or morphological differences between male, female, and testosterone-pretreated female mice under control conditions (data not shown). Three days after tunicamycin injection, male mice showed a slight but not significant increase in serum creatinine and BUN (0.7 ± 0.06 and 36.8 ± 8.4 mg/dl, respectively), whereas serum creatinine and BUN for tunicamycin-treated females (0.39 ± 0.01 and 17.23 ± 2.35 mg/dl) were similar to untreated control mice (0.39 ± 0.07 and 23.4 ± 1.16 mg/dl, respectively). As shown by Fig. 1, 5 days after tunicamycin injection, the BUN and creatinine levels in male mice were 132 ± 29.3 and 3.27 ± 0.63 md/dl, whereas the BUN and creatinine values of female mice were 17.2 ± 2.5 and 0.4 ± 0.05 mg/dl, similar to untreated (control) mice (23.4 ± 1.1 and 0.4 ± 0.07 mg/dl). Testosterone pretreatment of female mice increased BUN and creatinine values to 80.8 ± 19.4 and 1.8 ± 0.5 mg/dl (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Renal function 5 days after tunicamycin treatment. A: blood urea nitrogen (BUN). B: serum creatinine after tunicamycin (1 mg/kg body wt). Values, in mg/dl, represent means ± SE from at least 5 mice from each group. Statistical significance was assessed by the two-sided Student's t-test for independent samples. *Significance (P < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

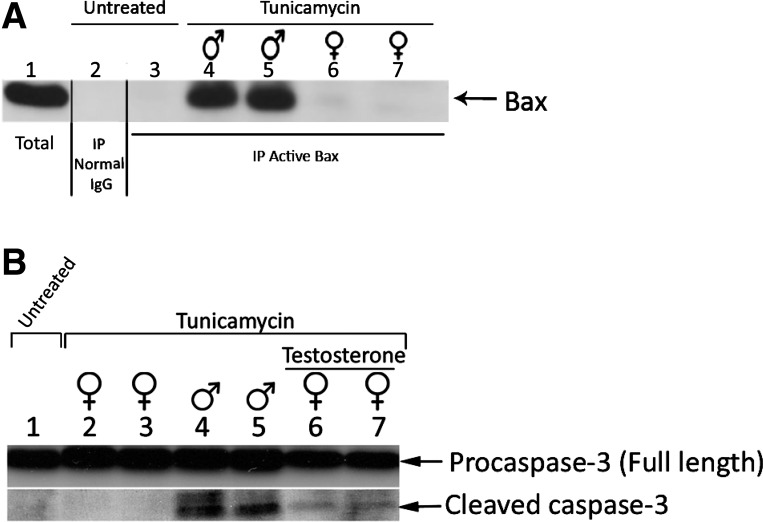

Activation of Bax and caspase-3 in male but not female mice after tunicamycin. A: Bax activation after tunicamycin is more significant in male compared with female mice. Immunoblot of Bax immunoprecipitated with nonspecific IgG (lane 2) or conformation-specific anti-Bax antibody (6A7) (lanes 3–7). Lane 1 represents the total Bax in the input samples. Proteins extracted from kidney of untreated mice (lanes 2 and 3), male mice injected with tunicamycin for 5 days (lanes 4 and 5), or female mice injected with tunicamycin (lanes 6 and 7). B: caspase-3 is activated in male but not female mice after tunicamycin injection. Caspase-3 (full length and cleaved) protein expression by Western blot. Whole kidney lysates (50 μg) prepared from untreated male (lane 1), tunicamycin-treated female (lanes 2 and 3), tunicamycin-treated male (lanes 4 and 5), and tunicamycin-treated female mice with testosterone (lanes 6 and 7). Both full-length (procaspase-3) and cleaved (active) caspase-3 are indicated.

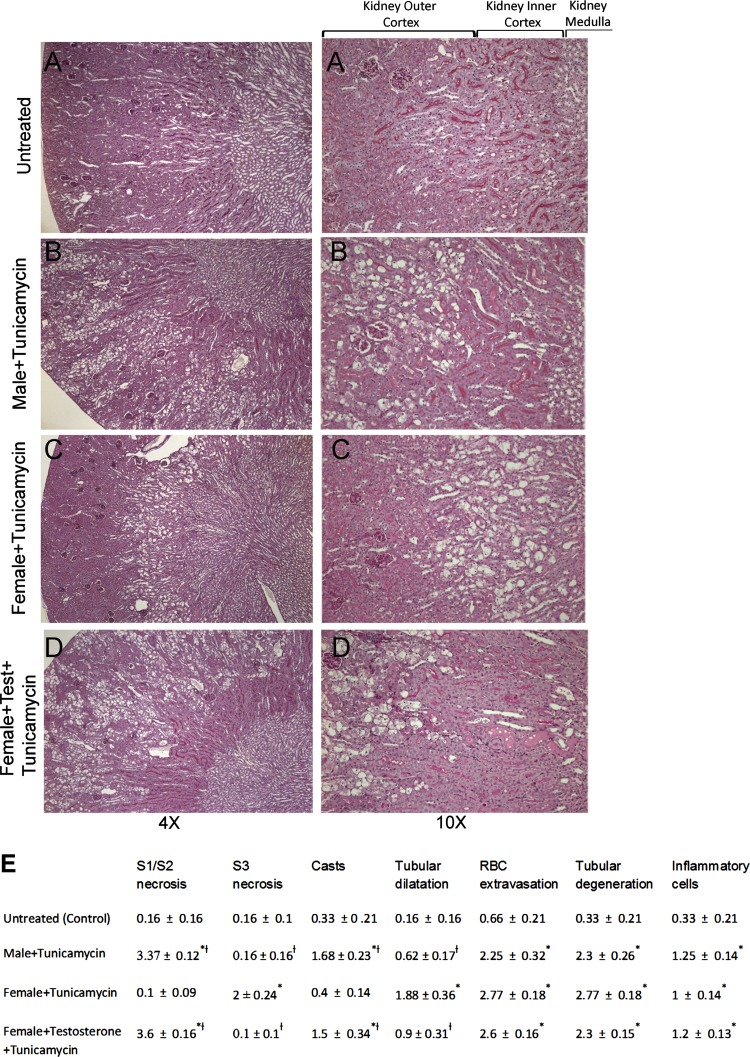

Histological evaluation of kidney morphology 3 and 5 days after tunicamycin injection showed a different injury pattern between male and female mice (Fig. 2). In untreated (control) conditions, male and female kidney histology was indistinguishable (Fig. 2A). Kidneys from 3 days tunicamycin-treated male mice showed signs of moderate vacuolic degeneration of the outer cortex (S1 and S2 segments of PT), whereas tunicamycin-treated female kidneys showed a similar degeneration in the inner cortex (S3 segment of PT) (data not shown). The morphological damage was more severe after 5 days of tunicamycin administration, with varying degrees of necrosis seen in the outer or inner cortex of male and female mice, respectively (Fig. 2, A–C and E). Testosterone pretreatment caused kidney damage in female mice after tunicamycin similar to damage seen in male mice (Fig. 2, D and E).

Fig. 2.

Morphological kidney damage of mouse kidneys 5 days after tunicamycin treatment. A–D: photomicrographs (×4 and ×10 magnification) of periodic acid-Schiff-stained kidney sections from untreated (A), tunicamycin-treated male (B), tunicamycin-treated female (C), or tunicamycin-treated female mice with testosterone (D). Kidney damage after tunicamycin is predominant in the outer cortex (S1 and S2 segments) in male and testosterone-treated female mice (B and D). In contrast, damage after tunicamycin in female mice is in the inner cortex (S3 segment) (C). E: quantitative evaluation of morphological kidney damage expressed as relative severity on a scale from 0 to 4. Values represent means ± SE of kidney sections from at least 6 mice in each group. *P < 0.05 compared with untreated (control). †P < 0.05 compared with females treated with tunicamycin.

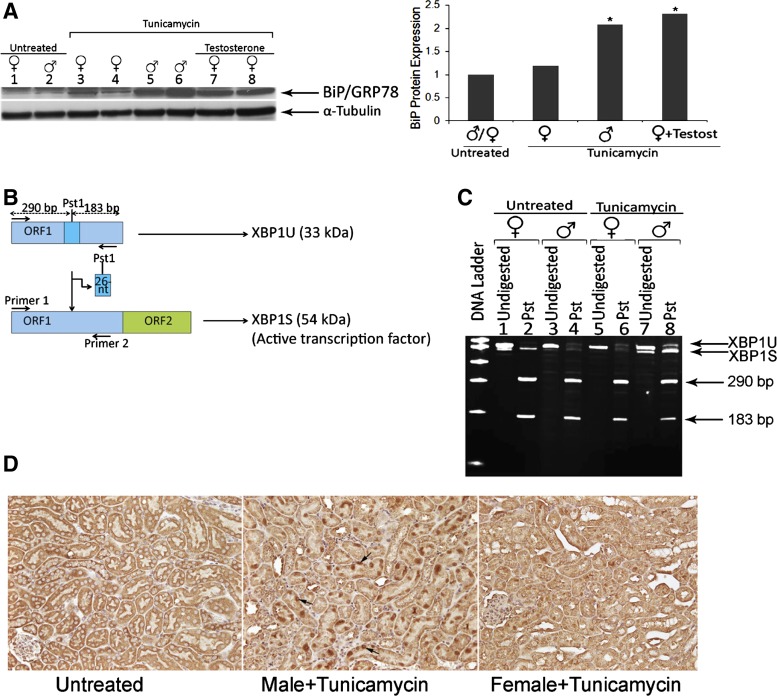

Induction of ER stress markers BiP/GRP78 and spliced XBP1 was higher in male mice after tunicamycin injection.

We next examined whether the difference in kidney injury between male and female mice was caused by a difference in ER stress response. We measured expression of the ER stress marker BiP/GRP78 by Western blot using protein lysates from mouse kidneys (Fig. 3A). Tunicamycin treatment increased BiP/GRP78 expression in male mice, and a low level of expression was detected in female mice after tunicamycin, similar to untreated animals. Testosterone administration to female mice before tunicamycin induced the expression of BiP/GRP78 to similar levels seen in tunicamycin-treated males.

Fig. 3.

Induction of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress markers immunoglobulin heavy chain-binding protein (BiP)/glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78) and spliced X-box-binding protein 1 (XBP1) was more elevated in male compared with female mice after tunicamycin treatment. A: BiP/GRP78 protein expression by Western blot after tunicamycin (5 days). Whole kidney lysates (50 μg) prepared from untreated female (lane 1), untreated male (lane 2), tunicamycin-treated female (lanes 3 and 4), tunicamycin-treated male mice (lanes 5 and 6), or tunicamycin-treated female mice with testosterone (lanes 7 and 8). α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. BiP/GRP78 protein levels were normalized to α-tubulin expression. Results represent the means of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with control. B: schematic representation of unspliced and spliced XBP1 mRNAs. The relative locations of the 26-nucleotide (nt) intron, Pst1 site, and the open reading frames (ORF1 and ORF2) are shown. Primer (1 and 2) annealing sites and the size of the amplification products with or without Pst1 digestion are also shown. C: XBP1 mRNA splicing is induced in male but not female mice after tunicamycin. RT-PCR analysis done on total RNA extracted from untreated (lanes 1–4), tunicamycin-treated female (lanes 5 and 6), and tunicamycin-treated male (lanes 7 and 8) mice. The XBP1 PCR product was digested with Pst1 restriction enzyme that differentiates between the unspliced XBP1 (XBP1U) and the spliced form (XBP1S) missing a 26-nt sequence containing the Pst1 site. The PCR products were then subjected to 8% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Digestion of unspliced XBP1 with Pst1 yields two fragments (183/290 bp) indicated by arrows. D: XBP1 protein immunohistochemistry 3 days after tunicamycin treatment. Kidney sections from untreated (D, left), tunicamycin-treated male (middle), and tunicamycin-treated female (right) mice were stained immunohistochemically for XBP1. Induction in XBP1 protein levels after tunicamycin is more evident in male mice compared with female mice. Examples of XBP1-positive cells are indicated by arrows.

During UPR, XBP1 mRNA encoding unspliced XBP1U protein (33 kDa) is spliced to excise a 26-nucleotide intron, causing a translational frameshift (Fig. 3B). Spliced XBP1 mRNA encodes a 54-kDa transcription factor (XBP1S) that translocates to the nucleus and regulates genes involved in ER homeostasis (12, 35). To detect unspliced (XBP1U) and spliced XBP1 (XBP1S) mRNA, we performed RT-PCR analysis using a pair of primers designed to encompass the intron containing a Pst1 site (2). Splicing of XBP1 disrupts a Pst1 restriction site localized within the 26-nucleotide excision site (Fig. 3B). Thus, Pst1 digestion is expected to cut XBP1U into two fragments of 290 and 183 bp, whereas XBP1S should be resistant to Pst1 digestion (Fig. 3B). As expected, in untreated mice, the amount of XBP1U mRNA was much higher than that of XBP1S mRNA and was digested by Pst1 (Fig. 3C, lanes 1–4). In male mice, there was marked induction in XBP1S after tunicamycin injection, and this was resistant to Pst1 digestion (Fig. 3C, lanes 7 and 8). In contrast, there was no induction in XBP1S mRNA in tunicamycin-treated female mice, and XBP1U was digested by Pst1 (Fig. 3C, lanes 5 and 6).

To determine whether spliced XBP1 protein expression was also increased in male vs. female mice after tunicamycin, we performed immunohistochemical analysis using paraffin-embedded sections from kidneys 3 days after tunicamycin administration (Fig. 3D). Sections from untreated mice (Fig. 3D, left) showed low background reaction to XBP1 antibody in the cytoplasm. Nuclear XBP1 staining was increased in the PT in the deep cortex 3 days after tunicamycin in male mice (Fig. 3D, middle). Tunicamycin-treated female mice showed significantly less XBP1 staining that was localized in the nuclei of PT of the outer cortex (Fig. 3D, right).

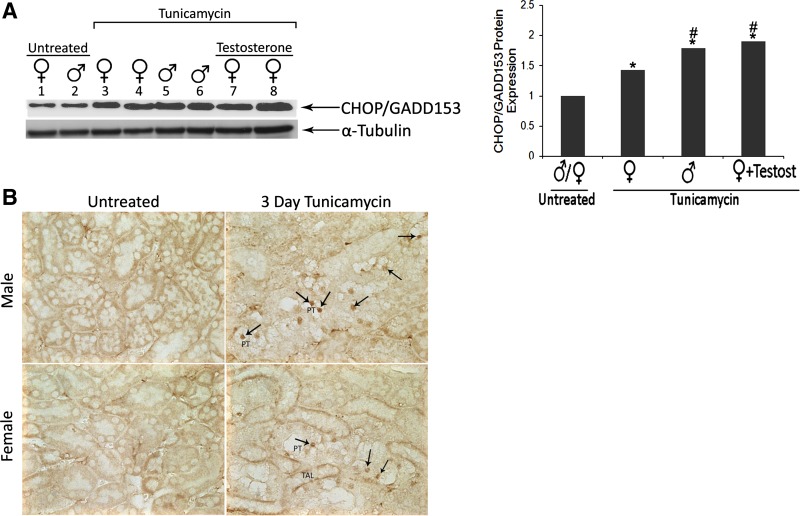

Induction of CHOP/GADD153 is higher in male and female mice after tunicamycin.

Next we investigated the expression of the proapoptotic ER stress marker CHOP/GADD153 in male and female mice after tunicamycin. Western blot analysis showed induction in expression levels of CHOP/GADD153 protein in male and female mice (Fig. 4A). CHOP/GADD153 protein levels after tunicamycin in testosterone-treated female mice were slightly higher than females with no testosterone, and similar to tunicamycin-treated males. Immunohistochemical analysis using the same antibody detected CHOP/GADD153 staining in both male (Fig. 4B, top right) and female (Fig. 4B, bottom right) mice 3 days after tunicamycin; however, this positive staining was more widespread in male compared with female mice after tunicamycin (Fig. 4B). CHOP/GADD153 positive staining in both male and female mice was predominantly in the nuclei of the PT cells that show signs of cell injury, such as vacuolization.

Fig. 4.

Induction of C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP)/GADD153 in male and female mice after tunicamycin. A: CHOP/GADD153 protein expression by Western blot. Whole kidney lysates (50 μg) prepared from untreated female (lane 1), untreated male (lane 2), tunicamycin-treated female (lanes 3 and 4), tunicamycin-treated male (lanes 5 and 6), or tunicamycin-treated female mice with testosterone (lanes 7 and 8). α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. CHOP/GADD153 protein levels were normalized to α-tubulin expression. Results represent the means of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with control. #P < 0.05 compared with female + tunicamycin by two-tailed Student's t-test. B: CHOP/GADD153 protein immunohistochemistry 3 days after tunicamycin treatment. Kidney sections from untreated male (top left), untreated female (bottom left), tunicamycin-treated male (top right), and tunicamycin-treated female (bottom right) mice were stained immunohistochemically for CHOP/GADD153. Examples of CHOP/GADD153-positive cells are indicated by arrows. Positive signals were observed mainly in the proximal tubules (PT). TAL, thick ascending limb.

Activation of Bax and caspase-3 in male but not in female mice after tunicamycin injection.

Previous in vitro data have suggested that Bax/Bak is required for mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis induced by ER stress (11). To examine Bax activation, we immunoprecipitated proteins using anti-Bax 6A7 antibody that recognizes the conformationally active form of Bax (Fig. 5A). As shown in Fig. 5A, active Bax was not detected in lysates from untreated mice (lanes 2 and 3). Immunoprecipitations using lysates from tunicamycin-treated male mice showed high levels of active Bax (lanes 4 and 5), whereas active Bax was not detected in tunicamycin-treated female mice (lanes 6 and 7). Immunoblotting showed levels of total Bax in the lysates (lane 1) and confirmed absence of active Bax after immunoprecipitation using normal IgG (lane 2).

The presence of activated (cleaved) caspase-3, the executor of apoptosis downstream of ER stress-mediated apoptotic signaling (36), is shown in Fig. 5B. During apoptosis, caspase-3 is processed from the inactive full-length p32 proform (also known as proscaspase-3) to a partially active p19/p12 and, through further autoprocessing, to a highly active p17/p12 form. Western blot analysis revealed that caspase-3 cleavage was significantly increased in the tunicamycin-treated male kidneys (Fig. 5B, lanes 4 and 5) compared with females (Fig. 5B, lanes 2 and 3). Caspase-3 cleavage was detected in testosterone-treated female mice after tunicamycin (Fig. 5B, lanes 6 and 7).

DISCUSSION

We found that male mice were more susceptible to renal failure caused by tunicamycin-induced ER stress than female mice (Fig. 1). The damage in male mice was located in the kidney outer cortex, in the S1 and S2 segments of the PT, while in females it was limited to the kidney inner cortex, mainly the S3 segment of the PT. Despite the presence of morphological damage in the female mice (Fig. 2C), their kidney function was normal (Fig. 1). Testosterone pretreatment of female mice increased their susceptibility to ER stress-induced AKI, shifted the major morphological site of kidney damage similar to the males (i.e., S1 and S2 segments of PT), and was also accompanied by functional impairment. Previous studies have implicated gender differences in renal I/R and nephrotoxin models of AKI (19, 26, 32). However, this is the first report to show sexual dimorphism in ER stress-induced AKI. Park et al. (26) demonstrated that male rats are more susceptible to I/R-induced kidney injury and that testosterone administration increased the susceptibility of females to I/R injury. In this study, both males and females showed kidney injury in the outer medullary S3 segment of the PT, although damage was more severe in males. In another study, Wei et al. (32) demonstrated that male mice were more sensitive to I/R, and most damage was identified in the outer stripe of the outer medulla that included the S3 segment of the PT and thick ascending limbs. In contrast, female mice were more sensitive to cisplatin nephrotoxicity (34). Tissue damage was concentrated throughout the cortex and outer medulla. In the current study we found gender differences in AKI caused by tunicamycin-induced ER stress. We demonstrated that testosterone increased the sensitivity of female mice to ER stress-induced kidney injury, and, furthermore, in presence of testosterone, the pattern of tubular injury and functional impairment in females was similar to males (Figs. 1 and 2). This suggests that, in this model of AKI, the damage of the outer cortex is important for functional kidney damage.

The involvement of ER stress in AKI has been shown in human and in various animal models (10, 24, 27). However, no evidence of gender differences during ER stress-induced renal injury has been reported before. To study whether the ER stress response is different between male and female mice, we measured the expression of ER markers, such as BiP/GRP78, spliced XBP1 mRNA, and markers involved in ER stress-induced apoptosis such as CHOP/GADD153, Bax, and caspase-3. We found that male mice injected with tunicamycin have higher levels of BiP induction than females (Fig. 3A). To confirm the differential regulation of the IRE-XBP1 signaling pathway, we assessed spliced XBP1 mRNA levels by RT-PCR. Similar to BiP expression, tunicamycin caused higher levels of spliced XBP1 mRNA in male than female mice (Fig. 3C). XBP1 immunohistochemistry showed increased nuclear staining especially in male mice compared with females after tunicamycin (Fig. 3D), suggesting higher splicing of XBP1. XBP1 staining in both groups was more obvious in areas showing no damage after tunicamycin. This suggests that XBP1 may play a role in the adaptive response to protect PT cells during ER stress. Previous studies have shown that cells with defects in XBP1 splicing are susceptible to ER stress-induced cell death and that XBP1 splicing is important in cell survival (12, 14, 15). The data from our study suggest that cells in the outer cortex of males and in the inner cortex of females (injured cells) are defective in XBP1 splicing, whereas cells in the deep cortex of males and outer cortex of females maintain their ability to activate XBP1 after tunicamycin. The evidence that BiP and spliced XBP1 levels are higher in male mice than females after tunicamycin supports the finding that males are more sensitive to ER stress. Both BiP and XBP1 are involved in the adaptive response to lessen damage from ER. However, the data showing that male mice are more susceptible to ER stress-induced AKI (Fig. 1) suggest that it may be due to differences in ER-induced apoptosis in the kidneys.

Several pathways have been shown to participate in mediating ER stress-induced apoptosis. One of them is CHOP/GADD153, which can be induced by PERK-eukaryotic initiation factor 2α-ATF4 and ATF6 pathways (16). We found an increase in CHOP expression in both males and females after tunicamycin, with levels slightly higher in males and in testosterone-treated female mice (Fig. 4A), and, similarly, immunohistochemistry for CHOP showed positive staining in both male and female mice after tunicamycin. This positive staining was mainly in the nuclei of the PT cells that show signs of injury (Fig. 4B). Although this suggests that CHOP induction may contribute to tunicamycin-induced AKI, it is unlikely that CHOP induction is the cause of the sexual dimorphism. This suggests that CHOP-independent cell death pathways may contribute to the sex differences. Severe ER stress may also induce apoptosis by caspase-12- and caspase-4-dependent apoptosis in mice and humans, respectively (9, 20). However, it has also been shown that ER stress could induce cell death in mice through a caspase-12-independent pathway (7). Here we did not detect active caspase-12 (data not shown), suggesting that, in this model, apoptosis is through a caspase-12-independent pathway. Another pathway for ER stress-induced apoptosis is through a Bax-dependent pathway. The fact that active Bax was only detected in male but not female mice after tunicamycin (Fig. 5A) suggests that Bax-dependent apoptosis may play a role in the sexual dimorphism of AKI induced by ER stress. This hypothesis is supported by the evidence showing activation of caspase-3 in male and in testosterone-treated female but not in female mice after tunicamycin (Fig. 5B).

In summary, we found that male mice are more susceptible to ER stress-induced AKI than females and that the presence of testosterone plays a critical role in sexual dimorphism in susceptibility to ER stress-induced AKI. The damage is mainly in the outer cortex (S1 and S2 segments of the PT) of males and the inner cortex in females (S3 segment). The vulnerability of males is associated with damage in the outer cortex, higher activation of markers involved in ER stress response, higher Bax activation, and higher caspase-3 activation. Our findings may have important implications for understanding the molecular basis of gender differences during AKI and also may provide an interesting model for studying kidney-specific segment damage and kidney function.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by research grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01-DK-54471), a Veterans' Affirs Merit Review, and with resources and the use of facilities at the John L. McClellan Memorial Veterans' Hospital (Little Rock, AR). H. I. Mustafa was a T32 fellow supported by the National Institutes of Health under the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award T32 DK061921 to the Division of Nephrology at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: R.H., J.M., H.I.M., and P.M.P. conception and design of research; R.H., J.M., A.T., N.S.H.L.S, and H.I.M. performed experiments; R.H. and J.M. analyzed data; R.H., J.M., A.T., H.I.M., P.M.P, and N.S.H.L.S. interpreted results of experiments; R.H. prepared figures; R.H. drafted manuscript; R.H., A.T., J.M., N.S.H.L.S, and P.M.P. edited and revised manuscript; R.H., J.M., A.T., H.I.M., N.S.H.L.S, and P.M.P. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Timothy C. Chambers (University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences) for sharing the Bax immunoprecipitation protocol. We thank Dr. Robert L. Safirstein for fruitful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bertolotti A, Zhang Y, Hendershot LM, Harding HP, Ron D. Dynamic interaction of BiP and ER stress transducers in the unfolded-protein response. Nat Cell Biology 2: 326–332, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calfon M, Zeng H, Urano F, Till JH, Hubbard SR, Harding HP, Clark SG, Ron D. IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature 415: 92–6, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao SS, Kaufman RJ. Unfolded protein response. Curr Biol 22: R622–R626, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chertow GM, Lee J, Kuperman GJ, Burdick E, Horsky J, Seger DL, Lee R, Mekala A, Song J, Komaroff AL, Bates DW. Guided medication dosing for inpatients with renal insufficiency. J Am Med Assoc 286: 2839–2844, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chertow GM, Lazarus JM, Paganini EP, Allgren RL, Lafayette RA, Sayegh MH. Predictors of mortality and the provision of dialysis in patients with acute tubular necrosis. The Auriculin Anaritide Acute Renal Failure Study Group. J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 692–698, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Mendonça A, Vincent JL, Suter PM, Moreno R, Dearden NM, Antonelli M, Takala J, Sprung C, Cantraine F. Acute renal failure in the ICU: risk factors and outcome evaluated by the SOFA score. Intensive Care Med 26: 915–921, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Sano F, Ferraro E, Tufi R, Achsel T, Piacentini M, Cecconi F. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces apoptosis by an apoptosome-dependent but caspase 12-independent mechanism. J Biol Chem 281: 2693–2700, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haze K, Yoshida H, Yanagi H, Yura T, Mori K. Mammalian transcription factor ATF6 is synthesized as a transmembrane protein and activated by proteolysis in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Biol Cell 10: 3787–3799, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hitomi J, Katayama T, Eguchi Y, Kudo T, Taniguchi M, Koyama Y, Manabe T, Yamagishi S, Bando Y, Imaizumi K, Tsujimoto Y, Tohyama M. Involvement of caspase-4 in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis and Abeta-induced cell death. J Cell Biol 165: 347–356, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawakami T, Inagi R, Takano H, Sato S, Ingelfinger JR, Fujita T, Nangaku M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces autophagy in renal proximal tubular cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 2665–2672, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim H, Tu HC, Ren D, Takeuchi O, Jeffers JR, Zambetti GP, Hsieh JJ, Cheng EH. Stepwise activation of BAX and BAK by tBID, BIM, and PUMA initiates mitochondrial apoptosis. Mol Cell 36: 487–499, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN, Glimcher LH. XBP-1 regulates a subset of endoplasmic reticulum resident chaperone genes in the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell Biol 23: 7448–7459, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liangos O, Wald R, O'Bell JW, Price L, Pereira BJ, Jaber BL. Epidemiology and outcomes of acute renal failure in hospitalized patients: a national survey. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 43–51, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin JH, Li H, Yasumura D, Cohen HR, Zhang C, Panning B, Shokat KM, Lavail MM, Walter P. IRE1 signaling affects cell fate during the unfolded protein response. Science 318: 944–949, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin JH, Li H, Zhang Y, Ron D, Walter P. Divergent Effects of PERK and IRE1 signaling. Plos One 4: e4170, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma Y, Brewer JW, Diehl JA, Hendershot LM. Two distinct stress signaling pathways converge upon the CHOP promoter during the mammalian unfolded protein response. J Mol Biol 318: 1351–1365, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marciniak SJ, Yun CY, Oyadomari S, Novoa I, Zhang Y, Jungreis R, Nagata K, Harding HP, Ron D. CHOP induces death by promoting protein synthesis and oxidation in the stressed endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev 18: 3066–3077, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morishima N, Nakanishi K, Takenouchi H, Shibata T, Yasuhiko Y. An endoplasmic reticulum stress-specific caspase cascade in apoptosis. Cytochrome c-independent activation of caspase-9 by caspase-12. J Biol Chem 277: 34287–34294, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Müller V, Losonczy G, Heemann U, Vannay A, Fekete A, Reusz G, Tulassay T, Szabó AJ. Sexual dimorphism in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats: possible role of endothelin. Kidney Int 62: 1364–1371, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakagawa T, Zhu H, Morishima N, Li E, Xu J, Yankner BA, Yuan J. Caspase-12 mediates endoplasmic-reticulum-specific apoptosis and cytotoxicity by amyloid-beta. Nature 403: 98–103, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishitoh H, Matsuzawa A, Tobiume K, Saegusa K, Takeda K, Inoue K, Hori S, Kakizuka A, Ichijo H. ASK1 is essential for endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced neuronal cell death triggered by expanded polyglutamine repeats. Genes Dev 16: 1345–1355, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Obialo CI, Crowell AK, Okonofua EC. Acute renal failure mortality in hospitalized African Americans: age and gender considerations. J Natl Med Assoc 94: 127–34, 2002 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohoka N, Yoshii S, Hattori T, Onozaki K, Hayashi H. TRB3, a novel ER stress-inducible gene, is induced via ATF4-CHOP pathway and is involved in cell death. EMBO J 24: 1243–1255, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pallet N, Bouvier N, Bendjallabah A, Rabant M, Flinois JP, Hertig A, Legendre C, Beaune P, Thervet E, Anglicheau D. Cyclosporine-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress triggers tubular phenotypic changes and death. Am J Transplant 8: 2283–2296, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park KM, Cho HJ, Bonventre JV. Orchiectomy reduces susceptibility to renal ischemic injury: a role for heat shock proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 328: 312–317, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park KM, Kim JI, Ahn Y, Bonventre AJ, Bonventre JV. Testosterone is responsible for enhanced susceptibility of males to ischemic renal injury. J Biol Chem 279: 52282–52292, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peyrou M, Hanna PE, Cribb AE. Cisplatin, gentamicin, and p-aminophenol induce markers of endoplasmic reticulum stress in the rat kidneys. Toxicol Sci 99: 346–353, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puthalakath H, O'Reilly LA, Gunn P, Lee L, Kelly PN, Huntington ND, Hughes PD, Michalak EM, McKimm-Breschkin J, Motoyama N, Gotoh T, Akira S, Bouillet P, Strasser A. ER stress triggers apoptosis by activating BH3-only protein Bim. Cell 129: 1337–1349, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 519–29, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen J, Chen X, Hendershot L, Prywes R. ER stress regulation of ATF6 localization by dissociation of BiP/GRP78 binding and unmasking of Golgi localization signals. Dev Cell 3: 99–111, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Urano F, Wang X, Bertolotti A, Zhang Y, Chung P, Harding HP, Ron D. Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science 287: 664–666, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei Q, Wang MH, Dong Z. Differential gender differences in ischemic and nephrotoxic acute renal failure. Am J Nephrol 25: 491–499, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu J, Rutkowski DT, Dubois M, Swathirajan J, Saunders T, Wang J, Song B, Yau GD, Kaufman RJ. ATF6α optimizes long-term endoplasmic reticulum function to protect cells from chronic stress. Dev Cell 13: 351–364, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamaguchi H, Wang HG. CHOP is involved in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis by enhancing DR5 expression in human carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem 279: 45495–45502, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshida H, Matsui T, Hosokawa N, Kaufman RJ, Nagata K, Mori K. A time-dependent phase shift in the mammalian unfolded protein response. Dev Cell 4: 265–271, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu F, Megyesi J, Price PM. Cytoplasmic initiation of cisplatin cytotoxicity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F44–F52, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]