Abstract

Intestinal epithelial cells undergo differentiation as they move from the crypt to the villi, a process that is associated with up- and downregulation in expression of a variety of genes, including those involved in nutrient absorption. Whether the intestinal uptake process of vitamin B2 [riboflavin (RF)] also undergoes differentiation-dependent regulation and the mechanism through which this occurs are not known. We used human-derived intestinal epithelial Caco-2 cells and native rat intestine as models to address these issues. Caco-2 cells showed a significantly higher carrier-mediated RF uptake in post- than preconfluent cells. This upregulation was associated with a significantly higher level of protein and mRNA expression of the RF transporters hRFVT-1 and hRFVT-3 in the post- than preconfluent cells; it was also accompanied with a significantly higher rate of transcription of the respective genes (SLC52A1 and SLC52A3), as indicated by the higher level of expression of heterogeneous nuclear RNA and higher promoter activity in post- than preconfluent cells. Studies with native rat intestine also showed a significantly higher RF uptake by epithelial cells of the villus tip than epithelial cells of the crypt; this again was accompanied by a significantly higher level of expression of the rat RFVT-1 and RFVT-3 at the protein, mRNA, and heterogeneous nuclear RNA levels. These findings show, for the first time, that the intestinal RF uptake process undergoes differentiation-dependent upregulation and suggest that this is mediated (at least in part) via transcriptional mechanisms.

Keywords: intestinal transport, cell differentiation, riboflavin, RFVT-1, RFVT-3

vitamin B2 [riboflavin (RF)] is an essential micronutrient needed for normal cell functions, such as growth and development. In its biologically active forms (riboflavin 5-phosphate and FAD), RF plays an important metabolic role in cellular oxidation-reduction reactions involving carbohydrate, protein, and lipid metabolism (8). RF deficiency leads to serious clinical abnormalities, including degenerative changes in the central nervous system, anemia, growth retardation, and skin lesions (8, 14, 28, 33). Deficiency and suboptimal levels of RF have been observed in a variety of conditions: in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases, chronic alcoholism, and diabetes mellitus and in chronic users of certain psychotropic agents (5, 12, 19, 30–32). RF deficiency also occurs in patients with Brown-Vialetto-Van Laere syndrome, a neurological disorder that is caused by mutations in hRFVT-3, as well as in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma (1, 6, 9, 24, 38, 45). In these patients, RF supplementation significantly improves symptoms and biochemical abnormalities (1, 6, 16, 45).

Humans and other mammals cannot synthesize RF endogenously and, therefore, must obtain the micronutrient from exogenous sources via intestinal absorption. The intestinal epithelium, therefore, plays an essential role in determining and regulating the normal level of RF in the body. Previous studies from our laboratory and others utilized a variety of human and animal intestinal preparations and showed that the intestinal absorption process of dietary RF in the small intestine is via a specific carrier-mediated mechanism (reviewed in Refs. 34 and 35). The molecular identity of the systems involved in this absorptive event has only recently begun to emerge as a result of cloning of the RF transporters (RFVT-1, RFVT-2, and RFVT-3) from a variety of human and animal tissues (48–50). hRFVT-1 and hRFVT-3 share 43% identity at the amino acid level with one another, while hRFVT-2 shares ∼87 and 44% identity with hRFVT-1 and hRFVT-3, respectively (49). RFVT-1 and RFVT-3 (products of the SLC52A1 and SLC52A3 genes, respectively) are expressed at the basolateral and brush border membrane domains of the polarized enterocytes, respectively, and appear to facilitate the vectorial transport of RF from the lumen into the circulation (40).

Intestinal epithelial cells undergo differentiation, which transforms the cells from an immature (undifferentiated) state to a mature (differentiated) state. This event occurs as the cells move upward from their place of birth in the crypt to the villus region and is associated with up- and downregulation of expression of a variety of genes, including those involved in nutrient (vitamin) absorption (7, 11, 22, 23, 25, 26, 39, 47). This differentiation-dependent regulation of expression of membrane carriers is designed to achieve and maintain normal function of intestinal epithelia. Understanding the mechanisms involved in regulation may assist in the design of effective strategies to promote faster recovery of intestinal epithelial injury, which occurs under certain pathophysiological conditions and as a result of use of certain pharmacological agents (e.g., certain anticancer drugs); therefore, addressing this issue in the case of RF is of physiological significance and may have therapeutic potential. Nothing is known about possible regulation of intestinal RF uptake during differentiation and the molecular mechanism involved; thus these aspects were investigated in this study. We use as models the intestinal epithelial Caco-2 cells [which differentiate spontaneously in culture upon reaching confluence (4, 7, 17)] and native rat intestine. Our results show that the intestinal RF uptake process is upregulated as the intestinal epithelial cells are transformed from the undifferentiated to the differentiated state and that this differentiation-dependent regulation is mediated, at least in part, via transcriptional regulatory mechanism(s) involving the SLC52A1 and SLC52A3 genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

[3H]RF (specific activity 21.2 Ci/mmol, radiochemical purity 98%) was obtained from Moravek Biochemicals (Brea, CA). Oligonucleotide primers were obtained from Sigma Genosys (The Woodlands, TX). All other chemicals and reagents were of analytical/molecular biology grade and were obtained from commercial sources.

Caco-2 cell culture and RF uptake assay.

Human-derived intestinal epithelial Caco-2 cells, a well-established model for studying differentiation-related aspects of intestinal epithelia (7, 11, 22, 23, 25, 26, 39, 47), were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and grown in a modified Eagle's medium (American Type Culture Collection) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum and appropriate antibiotics. Cells were plated at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well onto 12-well plates (Corning, Corning, NY). Uptake assays [initial rate 3 min (36)] were performed on preconfluent (1 day after seeding) and postconfluent (5 days after seeding, i.e., 3 days after confluence) Caco-2 cells. [3H]RF uptake was measured at 37°C in Krebs-Ringer buffer (pH 7.4), as described previously (26, 36, 39). Total protein content was determined using a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Isolation of villus and crypt cells from rat small intestine and uptake assay.

An established fractionation procedure (29) was used to isolate villus and crypt intestinal epithelial cells from the proximal half of rat small intestine, as described elsewhere (26, 37, 46). For this fractionation method, 10 factions were collected, with fractions 1 and 2 representing upper villus (mature/differentiated) epithelial cells and fractions 9 and 10 representing crypt (immature/undifferentiated) cells. Purity of these villus and crypt fractions has been established previously using marker enzymes (alkaline phosphatase and thymidine kinase for villus and crypt epithelial cells, respectively) (26). A rapid-filtration method (18) was used to examine the initial rate of [3H]RF uptake by freshly isolated villus and crypt cells at 37°C in Krebs-Ringer buffer at pH 7.4. All animals received humane care in compliance with the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, and the study was conducted according to protocols approved by the Veterans Affairs Medical Center Long Beach Subcommittee of Animal Studies.

Western blot analysis.

RIPA buffer (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was used to isolate total protein from pre- and postconfluent Caco-2 cells, as well as from rat small intestinal crypt and villus cells. Proteins (60 μg) were resolved onto premade 4–12% Bis-Tris minigel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and subjected to Western blot analysis, as described previously (27, 43). After electrophoresis, proteins were electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon, Fisher Scientific, Fremont, CA). Along with blocking buffer (LI-COR Bioscience, Lincoln, NE), the membranes were also incubated overnight with human RF transporters [hRFVT-1 (Abnova, Walnut, CA) and hRFVT-3 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Fremont, CA)] and rat RF transporters [rRFVT-1 (Sigma) and rRFVT-3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA)] specific polyclonal antibodies and the respective β-actin monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Specificity of the rat and human RFVT-1 bands has been previously established by overexpression of a green fluorescent protein-RFVT-1 construct in cells, followed by use of a green fluorescent protein monoclonal antibody (data not shown). Specificity of the rRFVT-3 band was determined using antigenic peptide (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) (data not shown), and specificity of the hRFVT-3 band was determined as described elsewhere (27). The immunoreactive bands were detected and quantified as described elsewhere (27, 43).

Real-time PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from pre- and postconfluent Caco-2 cells, as well as from rat jejunum villus and crypt cells. The DNase I-treated RNA was reverse-transcribed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad), and real-time PCR was performed using combinations of gene-specific primers (hRFVT-1, hRFVT-3, rRFVT-1, rRFVT-3, β-actin, and 18S; Table 1). Real-time PCR and determination of the relative level of mRNA expression of hRFVT-1 and RFVT-3 in pre- and postconfluent Caco-2 cells and rRFVT-1 and RFVT-3 in rat intestinal villus and crypt cells were performed as described elsewhere (21).

Table 1.

Combination of primers used to amplify the respective genes by real-time PCR, semiquantitative PCR, and cloning of the promoters

| Primers (5′-3′) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

| PCR primers | ||

| hRFVT-1 | AAAAGACCTTCCAGAGGGTTG | AGCACCTGTACCACCTGGAT |

| hRFVT-3 | CCTTTCCGAAGTGCCCATC | AGAAGGTGGTGAGGTAGTAGG |

| Human β-actin | AGCCAGACCGTCTCCTTGTA | TAGAGAGGGCCCACCACAC |

| rRFVT-1 | AGCTACCTGTAGTGGTGA | CTCAGCCCCTGAACCA |

| rRFVT-3 | TAAGGAAGATCACGGGCACCTC | GTCATCCAACTGGCCAACACAG |

| 18S | GGGAGGTAGTGACGAAAAATAACAAT | TTGCCCTCCAATGGATCCTC |

| hnRNA primers | ||

| hRFVT-1 | GACCTGCCTGTGAC | AACCCTCTGGAAGG |

| hRFVT-3 | TGACATCGCACAGG | CCTGCTGTTGATCTG |

| Human β-actin | TTCCTGGGTGAGTGGAG | GGACTCCATGCCTGAGAG |

| rRFVT-1 | CTTTAGGCCAGCTTCTTG | AAAATGCGAGTGGACAG |

| rRFVT-3 | TGGTGTTCTGCCCTCAG | GGGCCTGTGTTTGTAGC |

| Rat β-actin | CTGCTCTTTCCCAGATGAG | CTCATAGATGGGCACAGTG |

| Primers used for cloning of hRFVT-3 promoter | ||

| hRFVT-3 | CGACGCGTTTGATCAAATCCTGGTTG | CCGCTCGAGCTTCTTCCTTCTAGTACAAAGC |

hRFVT and rRFVT, human and rat riboflavin (RF) transporters, respectively; hnRNA, heterogeneous nuclear RNA.

Generation of hRFVT-3 (SLC52A3) full-length promoter construct and assay of promoter activity.

The transcriptional start site for the hRFVT-3 gene was determined by means of 5′-RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) using a kit from Life Technologies (RACE version 2.0 kit, Invitrogen). Genome analysis for hRFVT-3 reveals that it has one 5′-untranslated exon, and the putative ATG translational start site is located in exon 2. The transcriptional start site was determined by isolation of the total RNA from Caco-2 cells and synthesis of first-strand cDNA using gene-specific antisense primer (5′-TAGAGACACGCTAAC-3′), which is complementary to nucleotides 88–73 bp upstream from the putative ATG start of translation codon in mRNA. The first strand was isolated and deoxycytosine-tailed following the manufacturer's protocol. PCR was performed using abridged anchor primer (provided with the kit) and a second gene-specific reverse primer (5′-ATGGGAGACGAGGTCCGAAG-3′), which is complementary to nucleotides 109–132 bp upstream from the ATG codon. The PCR product was further subjected to nested PCR using a third gene-specific primer (5′-GCTCTCCTGGGATCTGGACTG-3′) complementary to nucleotides 142–165 bp upstream from the ATG codon. The PCR product was cloned in pGEM T Easy vector and sequenced (Laragen, Culver City, CA). We identified the hRFVT-3 transcriptional start site located 2,710 bp upstream from the ATG codon. We used human genomic DNA (Clontech) and gene-specific primers (Table 1) designed to amplify a ∼3.1-kb fragment of DNA, including the transcriptional start site, to clone the region 5,832 to 2,698 bp upstream from the ATG codon in pGL3-basic vector. Gene-specific sequence was obtained from GenBank (GI 306518672 for hRFVT-3). The PCR amplification was performed as described elsewhere (39), gel-purified using a GENECLEAN II kit (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH), and subcloned into the TA vector (Promega, Madison, WI) and then into the promoterless pGL3-basic vector (Promega) using enzymes MluI and HindIII for hRFVT-3. Sequence of the hRFVT-3 promoter was verified by sequencing (Laragen). The hRFVT-3 full-length promoter-luciferase reporter construct (4 μg), along with 100 ng of the transfection control plasmid Renilla luciferase-thymidine kinase (Promega), was transiently cotransfected into Caco-2 cells grown in 12-well plates at <50% confluence using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen). Caco-2 cells were lysed 24 h after transfection (preconfluence) and at 3 days after reaching confluence (postconfluence), and Renilla-normalized firefly luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase assay kit (Promega) and luminometer (Promega, Sunnyvale, CA) (26, 39).

Heterogeneous nuclear RNA analysis.

Level of heterogeneous nuclear RNA (hnRNA) is used as a measure of transcriptional activity of a given gene under different conditions (2, 10, 20, 41, 42). The RNA samples were treated with DNase I to avoid amplification of genomic DNA and reverse-transcribed with the random hexamer (Invitrogen). Using cDNA (synthesized from RNA) and gene-specific hnRNA primers that anneal to sequences in the intron/exon boundaries (Table 1), we determined the level of expression of human and rat RFVT-1 and RFVT-3 hnRNA in pre- and postconfluent Caco-2 cells and in rat villus and crypt epithelial cells. Real-time and semiquantitative PCR were performed as described previously (41, 42). The real-time PCR data for hRFVT-1 and hRFVT-3 were determined as described elsewhere (41, 42). The amplified rRFVT-1 and rRFVT-3 and β-actin hnRNA products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis, and the appropriate bands were quantified using UN-SCAN-IT gel digitizing software (Silk Scientific, Orem, UT).

Statistical analysis.

All uptake data (fmol·mg protein−1·unit time−1) are means ± SE of multiple separate uptake determinations. Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Uptake of [3H]RF by the carrier-mediated system was determined by subtracting uptake by passive diffusion {represented by residual uptake of [3H]RF in the presence of a high pharmacological concentration of unlabeled RF (1 mM)} from total [3H]RF uptake. Western blotting, real-time PCR, hnRNA, and promoter experiments were performed on at least three different occasions using different sample preparations.

RESULTS

Effect of differentiation on physiological and molecular parameters of RF uptake by human-derived intestinal epithelial Caco-2 cells.

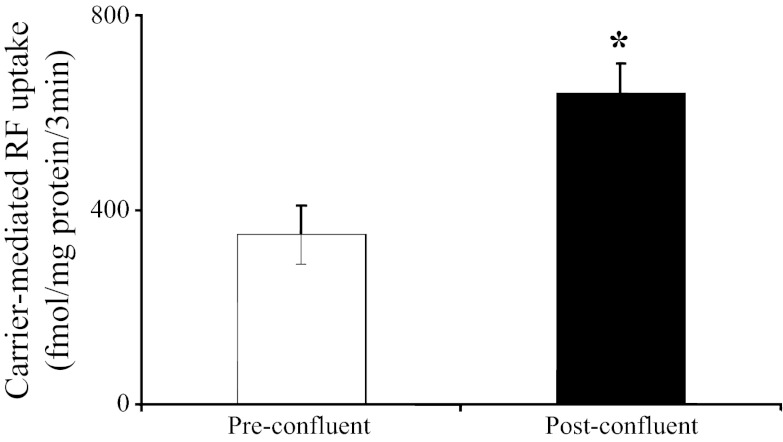

Figure 1 depicts the effect of differentiation of Caco-2 cells on the initial rate of carrier-mediated [3H]RF (14 nM) uptake. A significantly (P < 0.01) higher carrier-mediated RF uptake was observed in postconfluent (differentiated) than preconfluent (undifferentiated) Caco-2 cells.

Fig. 1.

Uptake of [3H]riboflavin (RF) by pre- and postconfluent Caco-2 cells. Carrier-mediated (initial rate) uptake of [3H]RF (14 nM) by pre- and postconfluent Caco-2 cells was studied at 37°C in Krebs-Ringer buffer (pH 7). Values are means ± SE from ≥3 independent uptake experiments from different batches of cells. *P < 0.01.

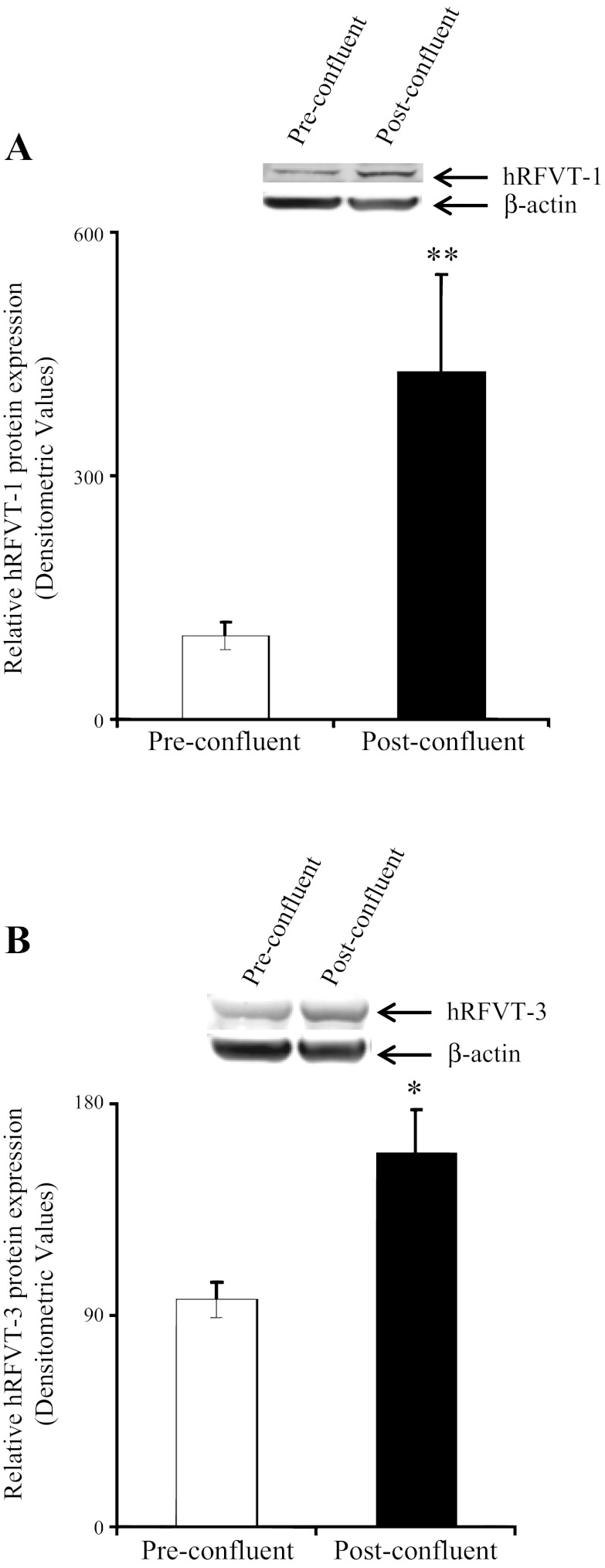

Figure 2 shows the effect of differentiation on the expression level of hRFVT-1 and hRFVT-3 proteins in Caco-2 cells. We focused on hRFVT-1 and hRFVT-3, since they represent the systems that transport RF across the basolateral and apical membrane domains of the enterocyte, respectively (40). The results showed that the level of expression of the hRFVT-1 and hRFVT-3 proteins was significantly (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively) higher in post- than preconfluent Caco-2 cells (Fig. 2). In another study, we examined the effect of differentiation on the level of expression of the hRFVT-1 and hRFVT-3 mRNA and observed a significantly (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively) higher expression of both transporters in post- than preconfluent Caco-2 cells (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Level of expression of RF transporter hRFVT-1 and hRFVT-3 proteins in pre- and postconfluent Caco-2 cells. Total proteins (60 μg) isolated from pre- and postconfluent Caco-2 cells were separated on 4–12% minigels and electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and probed with specific anti-hRFVT-1 (A) and anti-hRFVT-3 (B) polyclonal antibodies. The LI-COR detection system was used to detect immunoreactive bands and determine specific band intensity. Values are means ± SE from ≥3 independent sample preparations from different batches of cells. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.05.

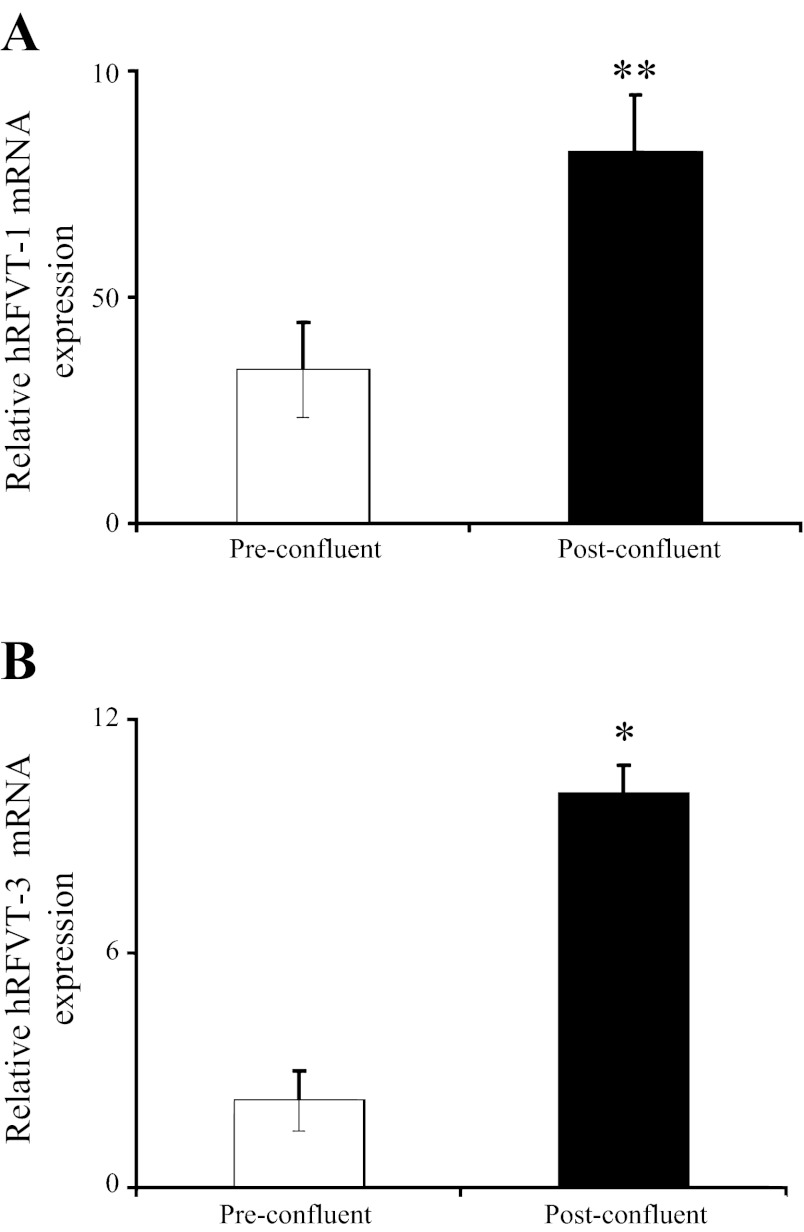

Fig. 3.

Level of expression of hRFVT-1 and hRFVT-3 mRNA in pre- and postconfluent Caco-2 cells. Real-time PCR was performed using hRFVT-1 (A) and hRFVT-3 (B) gene-specific primers and total RNA (5 μg) from pre- and postconfluent Caco-2 cells. Values are means ± SE from ≥3 independent sets of experiments from different batches of cells and were performed on different occasions. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.05.

To explore the effect of differentiation on transcriptional activities of the SLC52A1 and SLC52A3 genes (which encode hRFVT-1 and hRFVT-3, respectively), we used real-time PCR to examine the level of hnRNA of hRFVT-1 and hRFVT-3 in pre- and postconfluent Caco-2 cells. The hnRNA represents the first product of gene transcription, and its level reflects transcriptional activity of the particular gene (2, 10, 20, 41, 42). The results showed a significantly (P < 0.01 for hRFVT-1 and P < 0.05 for hRFVT-3) higher level of expression of the hRFVT-1 and hRFVT-3 hnRNA in post- than preconfluent Caco-2 cells (Fig. 4, A and B). These results suggest that the differentiation-dependent upregulation of the expression of hRFVT-1 and hRFVT-3 is, at least in part, mediated by an increase in the transcriptional activity of the respective gene. To further confirm this, we focused on the hRFVT-3 system, since it is the predominant and most efficient RF transport system expressed in the human small intestine and appears to play a key role in intestinal RF uptake (40), and cloned and sequenced the 5′-regulatory region (∼3.1 kb) of its gene (i.e., SLC52A3). We then examined the effect of differentiation of Caco-2 cells on the activity of the SLC52A3 promoter (attached to the firefly luciferase reporter gene) after transient transfection into Caco-2 cells. The results showed a significantly (P < 0.01) higher SLC52A3 promoter activity in post- than preconfluent Caco-2 cells (Fig. 4C). This finding further supports the suggestion that the increase in expression of RF transporters with differentiation is mediated, at least in part, via transcriptional mechanism(s).

Fig. 4.

Level of expression of hRFVT-1 and hRFVT-3 heterogeneous nuclear RNA (hnRNA) in pre- and postconfluent Caco-2 cells. A and B: real-time PCR was performed using hRFVT-1 and hRFVT-3 hnRNA gene-specific primers (Table 1) and RNA from pre- and postconfluent Caco-2 cells. Values are means ± SE of ≥3 independent determinations from 3 separate samples. C: activity of full-length SLC52A3 (hRFVT-3) promoter in pGL3-basic vector was determined following transient transfection into Caco-2 cells. Luciferase activity was determined in pre- and postconfluent Caco-2 cells and normalized relative to activity of simultaneously expressed Renilla luciferase. Values are means ± SE from ≥3 independent sets of determinations. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.05.

Effect of differentiation on physiological and molecular parameters of RF uptake by native rat intestine: studies using freshly isolated intestinal crypt and villus epithelial cells.

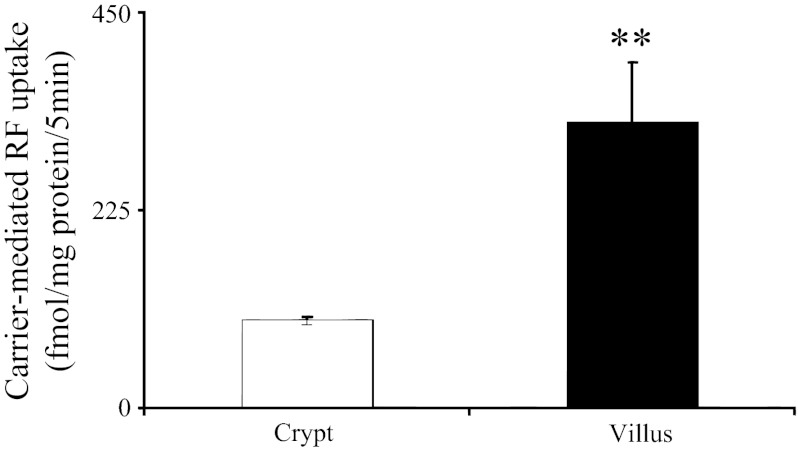

To validate the physiological relevance of the above-described findings with cultured Caco-2 cells, we used native rat intestine in these investigations. Immature crypt and mature villus epithelial cells were isolated from rat proximal small intestine and used fresh to study the initial rate of carrier-mediated [3H]RF (24 nM) uptake (36). The results showed a significantly (P < 0.05) higher carrier-mediated RF uptake in intestinal villus than crypt epithelial cells (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Uptake of [3H]RF by freshly isolated native rat intestinal crypt and villus epithelial cells. Carrier-mediated (initial rate) uptake of [3H]RF (24 nM) by crypt and villus intestinal epithelial cells isolated from rat jejunum was examined in Krebs-Ringer buffer (pH 7.4). Values are means ± SE of ≥3 independent uptake determinations performed on cells isolated from 3 different rats. **P < 0.05.

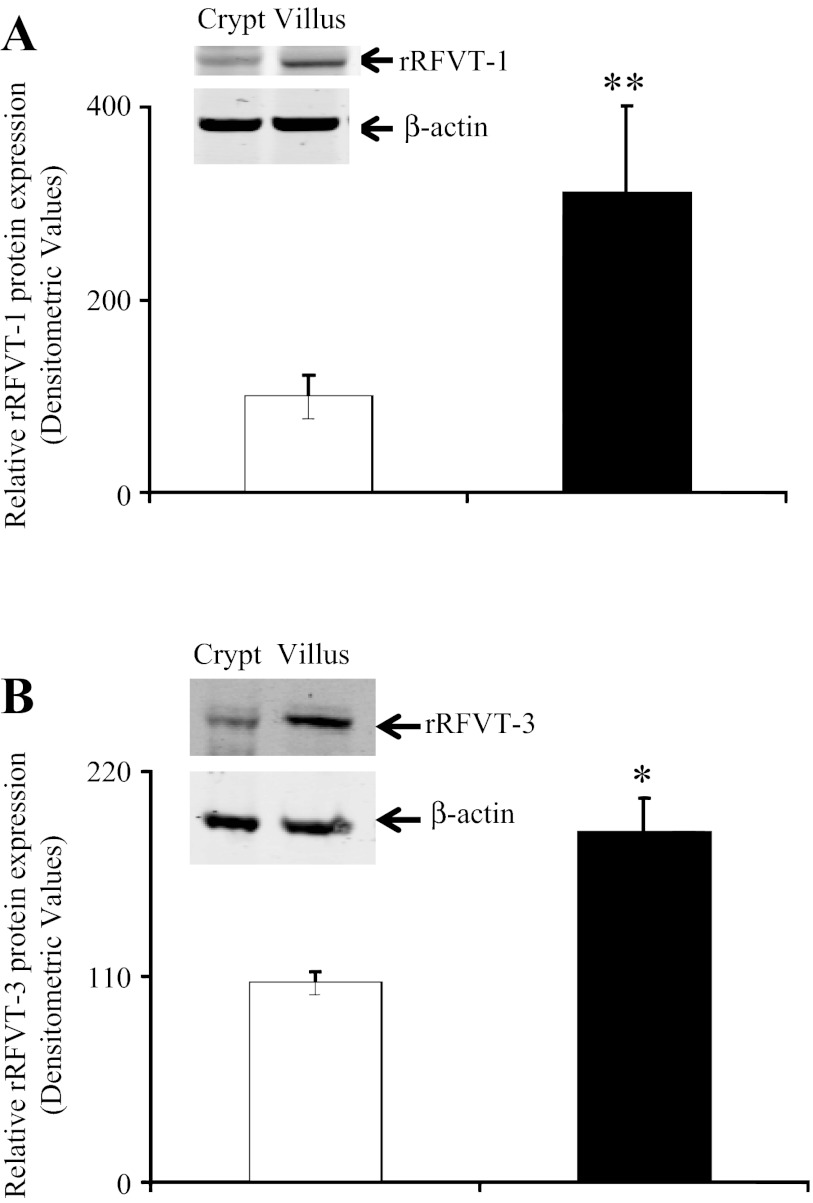

We also examined the level of expression of the rRFVT-1 and rRFVT-3 proteins in rat intestinal crypt and villus cell preparations by Western blotting using specific polyclonal antibodies. The results showed a significantly (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively) higher level of expression of the rRFVT-1 and rRFVT-3 proteins in intestinal villus than crypt epithelial cells (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Level of expression of rRFVT-1 and rRFVT-3 proteins in rat jejunum crypt and villus cells. Total proteins (60 μg) isolated from crypt and villus cells were separated onto 4–12% minigels and electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and probed with specific anti-rRFVT-1 (A) and anti-rRFVT-3 (B) polyclonal antibodies. Intensity of immunoreactive bands was determined as described in Fig. 2 legend. Values are means ± SE of 3 separate determinations from 3 different rats. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.05.

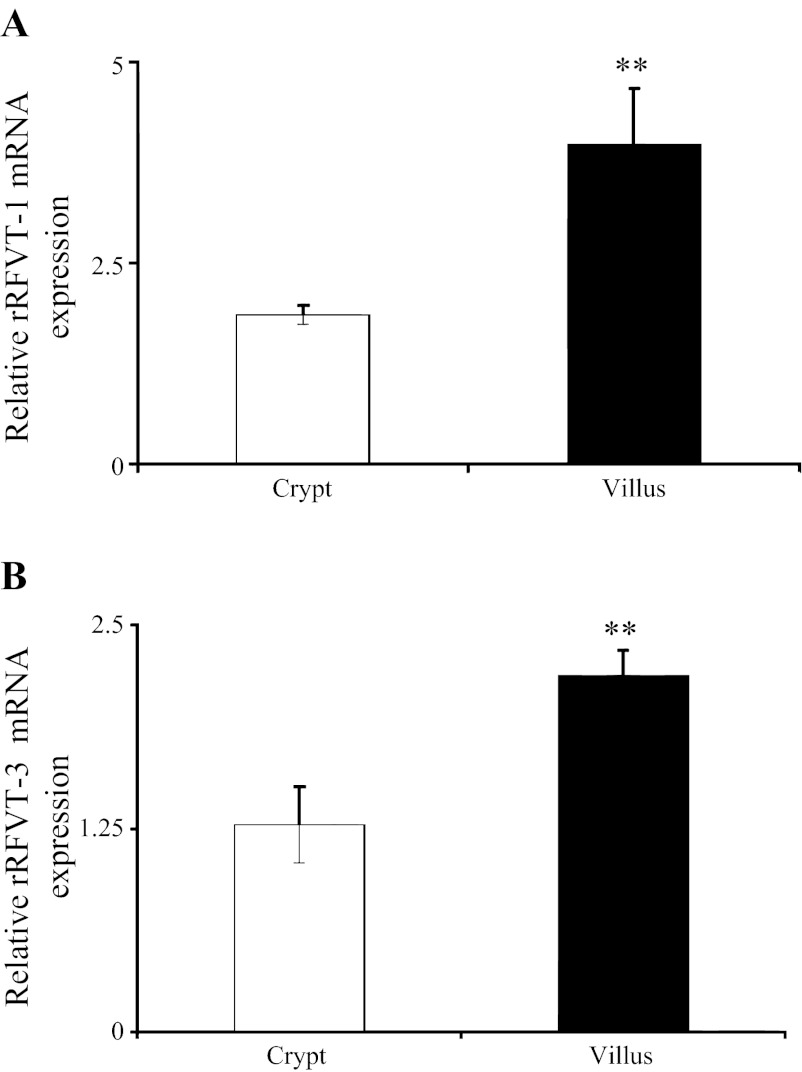

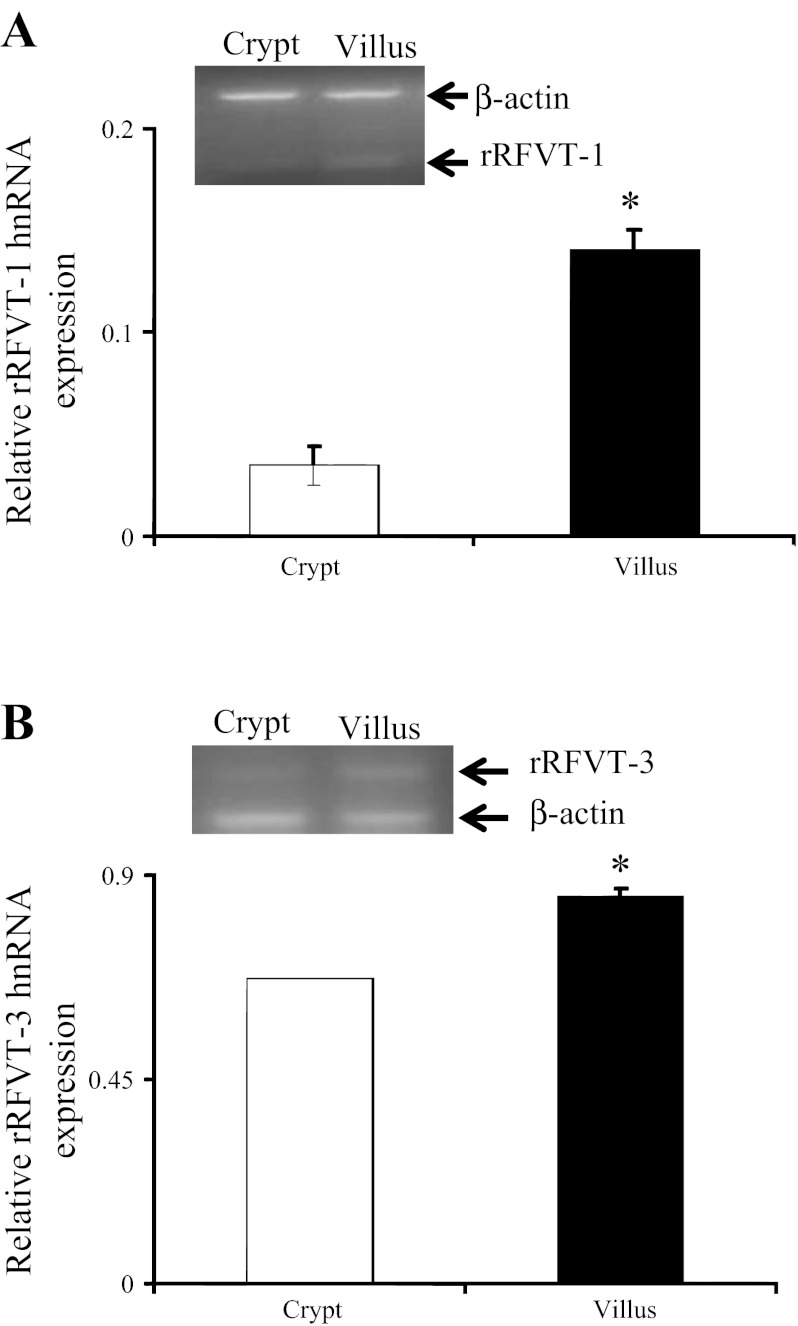

Level of expression of rRFVT-1 and rRFVT-3 mRNA in rat intestinal crypt and villus epithelial cells was also determined by means of PCR, with the results showing a significantly (P < 0.05 for both) higher level of expression of rRFVT-1 and rRFVT-3 mRNA in intestinal villus than crypt epithelial cells (Fig. 7). Finally, we examined the level of expression of rRFVT-1 and rRFVT-3 hnRNA in rat intestinal crypt and villus epithelial cells to gain an insight into the transcriptional activities of the Slc52a1 and Slc52a3 genes. Results of semiquantitative PCR showed a significantly (P < 0.01 for both) higher level of expression of rRFVT-1 and rRFVT-3 hnRNA in villus than crypt epithelial cells (Fig. 8). These findings with native rat intestine again suggest that the differentiation-dependent regulation of intestinal RF uptake is mediated, at least in part, via transcriptional mechanism(s).

Fig. 7.

Level of expression of rRFVT-1 and rRFVT-3 mRNA in native rat jejunum crypt and villus epithelial cells. Real-time PCR was performed using rRFVT-1 (A) and rRFVT-3 (B) gene-specific primers (Table 1) and total RNA isolated from rat intestinal crypt and villus epithelial cells. Values are means ± SE from ≥3 separate determinations on cells isolated from 3 different rats. **P < 0.05.

Fig. 8.

Level of expression of rRFVT-1 and rRFVT-3 hnRNA in rat jejunum crypt and villus epithelial cell. Semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed using rRFVT-1 (A) and rRFVT-3 (B) hnRNA gene-specific primers (Table 1) and RNA isolated from rat intestinal crypt and villus cells. Values are means ± SE of 3 separate samples from 3 rats. *P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Our aim in this investigation was to study whether the intestinal RF uptake process undergoes differentiation-dependent regulation and, if so, to shed light onto the physiological and molecular mechanisms involved in such regulation. It is well established that differentiation of intestinal epithelial cells is associated with changes in levels of expression of many genes, including those involved in nutrient (vitamins) uptake (11, 23, 26, 39). We used the human-derived cultured intestinal epithelial Caco-2 cells in our investigations, since they differentiate spontaneously in culture after reaching confluence and acquire a phenotype that closely reflects the mature absorptive enterocyte (4, 7, 17); indeed, a large number of studies have used these cells in such investigations (7, 23, 26, 39, 44, 47). We complemented our findings using this cultured cell model with studies utilizing freshly isolated rat native intestinal epithelial cells.

Our studies with Caco-2 cells showed a significantly higher RF uptake by postconfluent (differentiated) than preconfluent (undifferentiated) cells, clearly suggesting that the uptake process is under a differentiation-dependent type of regulation. This was associated with a higher level of expression of hRFVT-1 and hRFVT-3 at the protein and mRNA levels in the former than the latter cell type. The latter findings suggest possible involvement of a transcriptional mechanism(s) in mediating, at least part, the differentiation-dependent effect on the intestinal RF uptake process. The findings that the level of expression of the hnRNA of hRFVT-1 and hRFVT-3 is higher in post- than preconfluent Caco-2 cells support this suggestion, because the level of hnRNA (the first product of gene transcription) reflects the transcription rate of the relevant gene and, thus, has been used as an indicator for involvement of transcriptional mechanism(s) in changes in gene expression under different conditions (2, 10, 20, 41, 42). Involvement of transcriptional mechanism(s) in mediating, at least part, the differentiation-dependent regulation of intestinal RF uptake was further confirmed by the finding of activity of the SLC52A3 full-length promoter expressed in pre- and postconfluent Caco-2 cells: a significantly higher SLC52A3 promoter activity was found in post- than preconfluent Caco-2 cells. Further studies are required to determine the differentiation-dependent responsive region in the SLC52A3 promoter of the RF transporter and the cis- and trans-acting elements that mediate the differentiation-dependent effect.

The results with native rat intestinal epithelial cells complemented the findings with cultured Caco-2 cells, in that a significantly higher carrier-mediated RF uptake was observed in intestinal villus (differentiated) than crypt (undifferentiated) cells. This was again associated with a higher level of expression of rRFVT-1 and rRFVT-3 at the protein and mRNA levels in the mature villus than immature crypt epithelial cells. Also, the level of expression of rRFVT-1 and rRFVT-3 hnRNA was higher in villus than crypt epithelial cells. These findings again suggest possible involvement of a transcriptional mechanism(s) in mediating the differentiation-dependent regulatory effect on the intestinal RF uptake process.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate, for the first time, that the intestinal RF uptake process undergoes differentiation-dependent regulation and suggest that this regulation is, at least in part, mediated via a transcriptional mechanism(s).

GRANTS

The study was supported by grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants DK-58057 and DK-56061.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

V.S.S., A.G., and H.M.S. are responsible for conception and design of the research; V.S.S., A.G., S.B.S., and C.L. performed the experiments; V.S.S., A.G., S.B.S., and H.M.S. analyzed the data; V.S.S., A.G., S.B.S., and H.M.S. interpreted the results of the experiments; V.S.S., A.G., and S.B.S. prepared the figures; V.S.S., A.G., and H.M.S. drafted the manuscript; V.S.S., A.G., S.B.S., C.L., and H.M.S. edited and revised the manuscript; V.S.S., A.G., S.B.S., C.L., and H.M.S. approved the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Anand G, Hasan N, Jayapal S, Huma Z, Ali T, Hull J, Blair E, McShane T, Jayawant S. Early use of high-dose riboflavin in a case of Brown-Vialetto-Van Laere syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol 54: 187–189, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aydemir F, Jenkitkasemwong S, Gulec S, Knutson MD. Iron loading increases ferroportin heterogeneous nuclear RNA and mRNA levels in murine J774 macrophages. J Nutr 139: 434–438, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Betz AL, Ren XD, Ennis SR, Hultquist DE. Riboflavin reduces edema in focal cerebral ischemia. Acta Neurochir Suppl Wien 60: 314–317, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blais A, Bissonnette P, Berteloot A. Common characteristics for Na+-dependent sugar transport in Caco-2 cells and human fetal colon. J Membr Biol 99: 113–125, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bonjour JP. Vitamins and alcoholism. V. Riboflavin. VI. Niacin. VII. Pantothenic acid. VIII. Biotin. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 50: 425–440, 1980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bosch AM, Abeling NG, Ijlst L, Knoester H, van der Pol WL, Stroomer AE, Wanders RJ, Visser G, Wijburg FA, Duran M, Waterham HR. Brown-Vialetto-Van Laere and Fazio-Londe syndrome is associated with a riboflavin transporter defect mimicking mild MADD: a new inborn error of metabolism with potential treatment. J Inherit Metab Dis 34: 159–164, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Costa C, Huneau JF, Tome D. Characteristics of l-glutamine transport during Caco-2 cell differentiation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1509: 95–192, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cooperman JM, Lopez R. Riboflavin. In: Handbook of Vitamins: Nutritional, Biochemical and Clinical Aspects, edited by Machlin LJ. New York: Dekker, 1984, p. 299–327 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dipti S, Child AM, Livingston JH, Aggarwal AK, Miller M, Williams C, Crow YJ. Brown-Vialetto-Van Laere syndrome: variability in age at onset and disease progression highlighting the phenotype overlap with Fazio-Londe disease. Brain Dev 27: 443–446, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Elferink CJ, Reiners JJ., Jr Quantitative RT-PCR on CYP1A1 heterogeneous nuclear RNA: a surrogate for the in vitro transcript run-on assay. Biotechniques 20: 470–477, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fan MZ, Matthews JC, Etienne NM, Stoll B, Lackeyram D, Burrin DG. Expression of apical membrane l-glutamate transporters in neonatal porcine epithelial cells along the small intestinal crypt-villus axis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 287: G385–G398, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fernandez-Banares F, Abad-Lacruz A, Xiol X, Gine JJ, Dolz C, Cabre E, Esteve M, Gonzalez-Huix F, Gassull MA. Vitamin status in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 84: 744–748, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fujimura M, Yamamoto S, Murata T, Yasujima T, Inoue K, Ohta KY, Yuasa H. Functional characteristics of the human ortholog of riboflavin transporter 2 and riboflavin-responsive expression of its rat ortholog in the small intestine indicate its involvement in riboflavin absorption. J Nutr 140: 1722–1727, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goldsmith GA. Riboflavin deficiency. In: Riboflavin, edited by Rivlin R. New York: Plenum, 1975, p. 221–224 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Green P, Wiseman M, Crow YJ, Houlden H, Riphagen S, Lin JP, Raymond FL, Childs AM, Sheridan E, Edwards S, Josifova DJ. Brown-Vialetto-Van Laere syndrome, a ponto-bulbar palsy with deafness, is caused by mutations in c20orf54. Am J Hum Genet 86: 485–489, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. He Y, Ye L, Shan B, Song G, Meng F, Wang S. Effect of riboflavin-fortified salt nutrition intervention on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in a high incidence area, China. Asian Pac J Cancer 10: 619–622, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hidalgo IJ, Raub TJ, Borchardt RT. Characterzation of the human colon carcinoma cell line (Caco-2) as a model system for intestinal epithelial permeability. Gastroenterology 96: 736–749, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hopfer U, Nelson K, Perrotto J, Isselbacher KJ. Glucose transport in isolated brush border membrane from rat small intestine. J Biol Chem 248: 25–32, 1973 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kodentsova VM, Vrzhesinskaia OA, Sokol'nikov AA, Kharitonchik LA, Spirichev VB. [Metabolism of B group vitamins in patients with insulin-dependent and non-insulin-dependent forms of diabetes mellitus]. Vopr Med Khim 39: 26–29, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kohler CU, Roos PH. Focus on the intermediate state: immature mRNA of cytochrome P450—methods and insights. Anal Bioanal Chem 392: 1109–1122, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Livek KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mariadason JM, Nicolas C, L'Italien KE, Zhuang M, Smartt HJ, Heerdt BG, Yang W, Corner GA, Wilson AJ, Klampfer L, Arango D, Augenlicht LH. Gene expression profiling of intestinal epithelial cell maturation along the crypt-villus axis. Gastroenterology 128: 1081–1088, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maulen NP, Henriquez EA, Kempe S, Carcamo JG, Schmid-Kotsa A, Bachem Grunert A, Bustamante ME, Nualart F, Vera JC. Up-regulation and polarized expression of the sodium-ascorbic acid transporter SVCT1 in post-confluent differentiated Caco-2 cells. J Biol Chem 278: 9035–9041, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McShane MA, Boyd S, Harding B, Brett EM, Wilson J. Progressive bulbar paralysis of childhood. A reappraisal of Fazio-Londe disease. Brain 115: 1889–1900, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mordrelle A, Jullian E, Costa C, Cormet-Boyaka E, Benamouzig R, Tome D, Huneau JF. EAAT1 is involved in transport of l-glutamate during differentiation of the Caco-2 cell line. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 279: G366–G373, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nabokina SM, Reidling JC, Said HM. Differentiation-dependent up-regulation of intestinal thiamin uptake: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Biol Chem 280: 32676–32682, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nabokina SM, Subramanian VS, Said HM. Effect of clinical mutations on functionality of the human riboflavin transporter-2 (hRFT-2). Mol Genet Metab 105: 652–657, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pangrekar J, Krishnaswamy K, Jagadeesan V. Effects of riboflavin deficiency and riboflavin administration on carcinogen-DNA binding. Food Chem Toxicol 31: 745–750, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pinkus LM. Separation and use of enterocytes. Methods Enzymol 77: 154–162, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pinto J, Huang YP, Rivlin RS. Inhibition of riboflavin metabolism in rat tissue by chloropromazine, imipramine, and amitriptyline. J Clin Invest 67: 1500–1506, 1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pelliccione M, Pinto J, Huang YP, Rivlin RS. Acceleration of development of riboflavin deficiency by treatment with chloropromazine. Biochem Pharmacol 32: 2949–2953, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rosenthal WS, Adham NF, Lopez R, Cooperman JM. Riboflavin deficiency in complicated chronic alcoholism. Am J Clin Nutr 26: 858–860, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Said HM, Ross C. Riboflavin. In: Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease (11th ed.), edited by Ross C, Caballero B, Cousins RJ, Tucker KL, Ziegler TR. New York: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2011, p. 325–330 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Said HM, Nexo E. Intestinal absorption of water-soluble vitamins. In: Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract (5th ed.), edited by Johnson LR, Ghishan FK, Merchand JL, Said HM, Wood JD. San Diego, CA: Elsevier, 2012, p. 1711–1756 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Said HM. Intestinal absorption of water-soluble vitamins in health and disease. Biochem J 437: 357–372, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Said HM, Ma TY. Mechanism of riboflavine uptake by Caco-2 human intestinal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 266: G15–G21, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Said HM, Nguyen TT, Dyer DL, Cowan KH, Rubin SA. Interstinal folate transport: identification of a cDNA involved in folate transport and the functional expression and distribution of its mRNA. Biochim Biophys Acta 1281: 164–172, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Siassi F, Ghadirian P. Riboflavin deficiency and esophageal cancer: a case control-household study in the Caspian Littoral of Iran. Cancer Detect Prev 29:464–469, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Subramanian VS, Reidling JC, Said HM. Differentiation-dependent regulation of the intestinal folate uptake process: studies with Caco-2 cells and native mouse intestine. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295: C828–C835, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Subramanian VS, Subramanya SB, Rapp L, Marchant JS, Ma TY, Said HM. Differential expression of human riboflavin transporters-1, -2, and -3 in polarized epithelia: a key role for hRFT-2 in intestinal riboflavin uptake. Biochim Biophys Acta 1808: 3016–3021, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Subramanya SB, Subramanian VS, Said HM. Chronic alcohol consumption and intestinal thiamin absorption: effect of physiological and molecular parameters of the uptake process. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 299: G23–G31, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Subramanya SB, Subramanian VS, Kumar SJ, Hoiness R, Said HM. Inhibition of intestinal biotin absorption by chronic alcohol feeding: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 300: G494–G501, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Subramanya SB, Subramanian VS, Sekar VT, Said HM. Thiamin uptake by pancreatic cells: effect of chronic alcohol feeding/exposure. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 301: G896–G904, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vachon PH, Beaulieu JF. Transient mosaic patterns of morphological and functional differentiation in the Caco-2 cell line. Gastroenterology 103: 414–423, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang LD, Zhou FY, Li XM, Sun LD, Song X, Jin Y, Li JM, Kong GQ, Qi H, Cui J, Zhang LQ, Yang JZ, Li JL, Li XC, Ren JL, Liu ZC, Gao WJ, Yuan L, Wei W, Zhang YR, Wang WP, Sheyhidin I, Li F, Chen BP, Ren SW, Liu B, Li D, Ku JW, Fan ZM, Zhou SL, Guo ZG, Zhao XK, Liu N, Ai YH, Shen FF, Cui WY, Song S, Guo T, Huang J, Yuan C, Huang J, Wu Y, Yue WB, Feng CW, Li HL, Wang Y, Tian JY, Lu Y, Yuan Y, Zhu WL, Liu M, Fu WJ, Yang X, Wang HJ, Han SL, Chen J, Han M, Wang HY, Zhang P, Li XM, Dong JC, Xing GL, Wang R, Guo M, Chang ZW, Liu HL, Guo L, Yuan ZQ, Liu H, Lu Q, Yang LQ, Zhu FG, Yang XF, Feng XS, Wang Z, Li Y, Gao SG, Qige Q, Bai LT, Yang WJ, Lei GY, Shen ZY, Chen LQ, Li EM, Xu LY, Wu ZY, Cao WK, Wang JP, Bao ZQ, Chen JL, Ding GC, Zhuang X, Zhou YF, Zheng HF, Zhang Z, Zuo XB, Dong ZM, Fan DM, He X, Wang J, et al. Genome-wide association study of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Chinese subjects identifies susceptibility loci at PLCE1 and C20orf54. Nat Genet 42: 759–763, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Weiser MM. Intestinal epithelial cell surface membrane glycoprotein synthesis. J Biol Chem 248: 2536–2541, 1973 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wong WK, Chen K, Shih JC. Decreased methylation and transcription repressor Sp3 up-regulated human monoamine oxidase (MAO) B expression during Caco-2 differentiation. J Biol Chem 278: 36227–36235, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yamamoto S, Inoue K, Ohta KY, Fukatsu R, Maeda JY, Yoshida Y, Yuasa H. Identification and functional characterization of rat riboflavin transporter 2. J Biochem 145: 437–443, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yao Y, Yonezawa A, Yoshimatsu H, Masuda S, Katsura T, Inui K. Identification and comparative functional characterization of a new human riboflavin transporter hRFT3 expressed in the brain. J Nutr 140: 1220–1226, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yonezawa A, Masuda S, Katsura T, Inui K. Identification and functional characterization of a novel human and rat riboflavin transporter, RFT1. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295: C632–C641, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]