Abstract

The substantial number of young people in romantic relationships that involve intimate partner violence, a situation deleterious to physical and mental health, has resulted in increased attention to understanding the links between risk factors and course of violence. The current study examined couples’ interpersonal stress related to not liking partners’ friends and not getting along with parents as contextual factors associated with couples’ psychological partner violence and determined whether and when couples’ friend and parent stress increased the likelihood of couples’ psychological partner violence. A linear latent growth curve modeling approach was used with multiwave measures of psychological partner violence, friend stress, parent stress, and relationship satisfaction obtained from 196 men at risk for delinquency and their women partners over a 12-year period. At the initial assessment, on average, the men were age 21.5 years and the women were age 21 years. Findings indicated that couples experiencing high levels of friend and parent stress were more likely to engage in high levels of psychological partner violence and that increases in couples’ friend stress predicted increases in couples’ partner violence over time, even when accounting for the couples’ relationship satisfaction, marital status, children in the home, and financial strain. Interactive effects were at play when the couples were in their early 20s, with couples being most at risk for increases in psychological partner violence if they experienced both high friend stress and low relationship satisfaction. Couples’ friend stress had the greatest effect on psychological partner violence when the couples were in their early to mid 20s when levels of friend stress were high. As the couples reached their 30s, low relationship satisfaction became the leading predictor of couples’ psychological partner violence.

Keywords: Couples, Domestic violence, Intimate partner violence, Psychological aggression, Relationship satisfaction, Stress

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a common problem in romantic and marital relationships and has serious physical and mental health consequences (e.g., Breiding et al. 2008; Coker et al. 2002). Once initiated, violent patterns of interacting and resolving conflict with romantic partners become difficult to break (Shortt et al. 2012), underscoring the importance of identifying developmental precursors to and risk factors of IPV (Ehrensaft et al. 2003). It is notable that available prevention programs, which to date have demonstrated limited effectiveness in reducing IPV, overall have not been grounded in empirically supported models of IPV risk factors (Capaldi and Langhinrichsen-Rohling 2012; Whitaker et al. 2006). Stress has received relatively little attention as a contextual factor of IPV, but evidence from a recent review of risk factors for IPV indicates that stress may play a significant role in predicting IPV (Capaldi et al. 2012). Factors such as disliking partner’s parents and resenting the time partner spends out with friends can cause stress in a relationship, indeed family and friend involvement in couples’ lives has been found to be the most commonly described life-circumstance stressor (Stith et al. 2011). Despite this, interpersonal stress related to partners’ relationships with friends and parents has been little examined in relation to IPV. Thus, the current study sought to understand links between IPV and the contextual factors of friend and parent stress in relation to relationship satisfaction and determine whether and when friend and parent stress increase the likelihood of couples’ psychological IPV.

Psychological IPV (or emotional abuse) refers to offensive or degrading behavior toward the partner (e.g., threats, ridicule, and withholding affection) and is considered qualitatively different from negative communication and poor conflict management skills (Ro and Lawrence 2007). Psychological IPV is highly prevalent, relatively stable, largely bidirectional, and may have a severe impact (e.g., Carney and Barner 2012; Lawrence et al. 2009; O’Leary 2001; Taft et al. 2006). Psychological IPV has a higher prevalence than physical IPV and has been identified as a correlate and antecedent to physical IPV (e.g., Capaldi et al. 2007; Frye and Karney 2006). From a dynamic developmental systems perspective, IPV is conceptualized as an interactional pattern within the dyad that is responsive to the developmental characteristics and behaviors of each partner and to both broader and proximal contextual factors (Capaldi et al. 2004; Capaldi et al. 2005). Psychological IPV, which is present to at least a minor or infrequent degree for almost all couples (e.g., Shortt et al. 2012), may be relatively sensitive to stress. Thus, examining this association may provide insight into the effect of friend and parent related stress on couples’ IPV.

Regarding the effects of stress on couples’ adjustment, both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies on romantic relationships suggest that stressful experiences adversely impact couples’ relationship functioning (for reviews, see Neff 2012; Randall and Bodenmann 2009). Using daily diary studies, more stress at work was linked prospectively to more anger and withdrawal behaviors toward partners after work (Schulz et al. 2004; Story and Repetti 2006). Higher levels of newlywed couples’ chronic stress (related to family/friends/in-laws, work/school experiences, finances, health) were related to lower levels and greater declines in relationship satisfaction for husbands and wives over 4 years (Karney et al. 2005). At times when newlywed wives reported higher levels of external stress (related to parenthood, family/friends/in-laws, work/school experiences, unemployment, finances, living conditions, health) over 3.5 years, both the wives and their husbands reported lower levels of relationship satisfaction (Neff and Karney 2007). The stressful experiences of one partner can adversely impact the relationship functioning of both the other partner and the dyad.

Couples’ stress appears to impinge on relationship functioning by depleting couples’ abilities to respond to their partners and to interact with them in adaptive ways. Newlywed wives who experienced more acute life events (related to family/friends, work/school, finances, health, personal, living conditions, legal stress) and less relationship satisfaction over 4 years were more likely to exhibit a negative attribution style with marital problems and a tendency to blame husbands for these problems (Neff and Karney 2004). Using daily diary reports, couples with greater levels of external stress (related to family/friends/in-laws, work/school experiences, finances, health) and lower levels of relationship satisfaction were prone to perceive daily relationship experiences as more negative and to respond to these experiences in a more reactive manner (Neff and Karney 2009). Also using daily diary reports, higher levels of newlywed couples’ daily stress external to the marriage (e.g., poor feedback at work/school, argument with friends, sickness or injury, problems with transportation) were related to depleted self-regulatory capabilities, which in turn were related to more negative relationship behaviors toward partners (Buck and Neff 2012). Stress in couples’ lives interferes with their abilities to engage in adaptive relationship behaviors.

Although there are far fewer studies on links between couples’ stress and IPV, the limited evidence suggests that the stressful experiences can increase the likelihood of couples’ physical and psychological IPV. For newlywed couples, acute stress (e.g., being passed over for a work promotion, having a school application rejected, encountering unexpected expenses) was positively associated with psychological IPV over 3 years while controlling for simultaneous associations with relationship satisfaction (Frye and Karney 2006). When couples experienced higher levels of acute stress, both husbands and wives were more likely to engage in higher levels of psychological IPV. Husbands who experienced higher levels of chronic stress were also more likely to engage in higher levels of physical IPV (Frye and Karney 2006). In another study of newlywed couples, changes in couples’ chronic stress (related to family/friends/in-laws, work/school experiences, financial status, health) were positively associated with changes in physical IPV in the first 3 years of marriage (not controlling for relationship satisfaction) (Langer et al. 2008). Specifically, increases in couples’ chronic stress predicted increases in physical IPV over time for both husbands and wives (not controlling for relationship satisfaction). In a rare study, albeit cross sectional that did not involve newlywed couples, married couples experiencing external stress (job stress, financial strain, stress during free time, stress in other relationships) were more likely to be verbally aggressive with each other (not controlling for relationship satisfaction) (Bodenmann et al. 2010). In sum, there is evidence for pervasive negative effects of various types of stress on adjustment and IPV for couples in romantic relationships.

The Current Study

The current study examined interpersonal stress related both to not liking partners’ friends and not getting along with parents as contextual factors associated with psychological IPV. Couples’ friend stress, in this study, referred to disagreement related to not liking their partners’ friends and considering their partners’ friends negative influences. Not liking partner’s friends was a relatively frequently picked discussion topic by young couples in the problem-solving task in the Oregon Youth Study (OYS)-Couples Study (Capaldi et al. 2004), the sample for the current study. Friend stress, as defined, has some conceptual overlap with delinquent peer affiliation. Although there has been some evidence linking delinquent peer affiliation and peer delinquency training processes during adolescence to dating violence and later IPV (Capaldi et al. 2001; Casey and Beadnell 2010; Miller et al. 2009), systematic research on partners’ friend stress and IPV has been limited in the literature. Similarly, while some of the family variables (e.g., witnessing IPV of parents) are frequently studied precursors of IPV (e.g., Capaldi et al. 2012; Langhinrichsen-Rohling and Capaldi 2012; Olsen et al. 2010), stress related to relationships with parents has been less studied. Parent stress in the current study referred to not getting along with one’s own parents and disagreement within the relationship regarding one’s own or partners’ parents. The study’s focus on friend stress separate from parent stress avoids the tendency of previous studies to combine types of stress across domains (e.g., experiences with family, friends, work, and school combined together) and ignore the possibility that stressors may have differential effects. Although the source of friend and parent stress originates outside of the couple, both partners are likely to be affected by friend and parent stress to some degree (Bodenmann 2005).

The current study has a number of important strengths that enable us to take the next step in understanding links between stressful contexts and couples’ psychological IPV. The men and their partners in the current study comprise a community sample of couples, compared to existing studies focusing on newlywed couples. A multimethod, multiagent measurement strategy involving self- and partner reports as well as observational data was used to measure couples’ psychological IPV. The study started in young adulthood and, thus, provides important bridging information between studies of teen dating and studies with older newlywed or adult samples. Prior studies with the sample used in the current study showed that IPV in the adolescent years predicted IPV at age 20 years (Capaldi et al. 2003), which further predicted future IPV well into the 20s (Shortt et al. 2012). The current study extended this earlier work on the cross-sectional or short-term (less than 5 years) longitudinal designs and examined couples’ psychological IPV over the course of 12 years from when the men and their partners were in their early 20s through their early 30s. This substantial period with the availability of multiple waves of couples’ data provided the opportunity to specify the developmental timing of the effects, in other words, whether the effects of friend and parent stress on IPV were strongest for the couples at specific ages or influential across the study time period. This study acknowledged that couples’ relationship dissatisfaction and high discord are robust proximal contextual factors related to couples’ IPV (Capaldi et al. 2012). Controlling for relationship satisfaction allowed for testing whether both friend and parent stress had unique contributions to couples’ IPV above and beyond the association expected due to couples’ levels of satisfaction with their relationships. Further, this study was unique in its examination of the interactive effects between the contextual factors of couples’ friend and parent stress and relationship satisfaction on psychological IPV, and the ability to determine whether the effect of friend and parent stress on psychological IPV was moderated by relationship satisfaction.

Hypotheses on the association between couples’ interpersonal stress and psychological IPV were guided by the developmental systems perspective (e.g., Capaldi et al. 2004, 2005). We tested whether couples’ friend and parent stress would be associated with the likelihood of couples’ psychological IPV while simultaneously accounting for how satisfied couples were in their relationships, such that couples with high levels of friend or parent stress would be more likely to have high levels of psychological IPV and that changes in couples’ friend and parent stress would positively predict changes in couples’ psychological IPV over time (above and beyond what could be explained by couples’ levels and rates of change in relationship satisfaction). Additionally, we examined when or at what ages couples’ friend and parent stress, relationship satisfaction, and the interaction between friend and parent stress and relationship satisfaction would be associated with psychological IPV. We predicted that couples’ friend and parent stress would be more likely to be associated with an increase in the likelihood of couples’ psychological IPV at younger ages than at older ages, and that couples who experienced both high stress and low relationship satisfaction would be at the greatest risk for psychological IPV compared with those couples experiencing only one of these contextual risk factors. Several control variables also were included in the analyses: marital status due to research suggesting more IPV in cohabiting compared to marital relationships (e.g., Cui et al. 2010), children in the home due to research suggesting that the prevalence of IPV is higher for couples with children compared to couples without children (e.g., McDonald et al. 2006), and financial strain due to previous studies that have demonstrated that low income increases the likelihood of IPV (e.g., Cunradi et al. 2002).

Methods

Participants

The 196 couples that participated in the current study were comprised of the OYS men and their romantic women partners. The OYS men (N = 206) were recruited (with a 74 % participation rate) at ages 9–10 years from public schools in neighborhoods with a higher-than-usual incidence of juvenile delinquency located in a medium-size metropolitan area in the Pacific Northwest. The men were from families that were predominately working class (75 % according to the social status index; Hollingshead 1975). The OYS men were assessed annually through the ages of 31–33 years, with retention rates at each time point of at least 93 %.

The OYS-Couples Study was initiated when the men were aged 17–18 years. Using gender neutral wording, the men were informed of the opportunity to participate in a couples assessment with a romantic partner or spouse. No minimum length of relationship was set and the couples defined their relationship status (dating, living together, engaged, or married). Six further assessments were completed about every 2 years when the men were at ages 20–23, 23–25, 25–27, 27–29, 29–31, and 31–33 years. The current study involves these six later waves collected during calendar years 1994–2007, defined herein as T1–T6 because of limited assessment of IPV at ages 17–18 years. The OYS men’s participation rate in the couples assessment with a romantic partner across T1–T6 ranged from 76 to 96 %. For men who participated in the OYS-Couples Study with more than one partner, only data from the men’s longest heterosexual relationships were included (one man that participated with a same-sex partner was not included in the analyses). On average, men participated with their partners at three waves. The couples were predominantly European American (90 % for the men and 85 % for the women), and across assessments, couples reported an average combined annual income of $41,000 (standard deviation of $30,000). Additional demographic information for the couples is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Couples sample across 12 years

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N of couples | 86 | 110 | 126 | 123 | 118 | 105 |

| His age (in years) | 21.5 | 24.0 | 26.1 | 28.0 | 30.0 | 32.0 |

| Her age (in years) | 21.0 | 23.2 | 25.1 | 26.5 | 28.4 | 30.2 |

| Relationship length (in years) | 2.1 | 3.5 | 4.2 | 5.1 | 6.7 | 8.6 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married (N) | 20 | 47 | 68 | 70 | 83 | 82 |

| Married (%) | 10 | 24 | 35 | 36 | 42 | 42 |

| Children in the household | ||||||

| Average number of children | .41 | .78 | .93 | 1.04 | 1.25 | 1.50 |

| At least 1 child (N) | 28 | 59 | 69 | 72 | 76 | 77 |

| Financial strain (financial aid received, range 0–6) | ||||||

| Average number of sources | .50 | .39 | .33 | .34 | .25 | .18 |

| At least 1 source received (N) | 46 | 51 | 46 | 50 | 39 | 20 |

Procedures

At each time point, the couples participated in a 2-h assessment that included separate interviews and questionnaires for the men and women and a series of videotaped couples discussion tasks. The discussion tasks were as follows: warm up (7 min), party planning (5 min), problem solving (7 min for each partner’s issue related to the relationship), and goals (5 min for each partner’s goal). For more information regarding the discussion tasks, including safety procedures in the study, see Capaldi et al. (2003) or Shortt et al. (2006). Informed consent was obtained at each time point. For their time, participants were compensated $70 each at T1 and T2, $125 each at T3 and T4, and $150 each at T5 and T6.

Measures

Coding of the Discussion Tasks

The Family and Peer Process Code (FPPC: Stubbs et al. 1998) used for the discussion tasks is a real-time code comprised of 24 content codes, including verbal, vocal, nonverbal, and physical behaviors. There were six affect ratings (happy, caring, neutral, distress, aversive, and sad) assigned on the basis of body language, vocal inflection, facial expressions, and nonverbal gestures to assess the emotional tone of each content code. Content and affect codes were independent of each other (any affect could be assigned to any content). Approximately 15 % of the observations at each time point were randomly selected to be coded independently by two different coders to assess coder reliability. The overall content and affect kappas across time points ranged from .73 to .85. Coders also provided ratings on behaviors observed during the tasks including IPV and friend and parent stress.

Time-Variant Variables (Measured at T1–T6)

Psychological IPV

The psychological IPV construct was comprised of three agent indicators: (a) self-report using the 6-item psychological aggression scale from the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS: Straus 1979; “Yelled and/or insulted partner”), 1 item from Adjustment with Partner (AP: Kessler 1990; “When disagree, how often do you insult or swear, sulk or refuse to talk, stomp out of the room, threaten to hit?”), 10 items from the Dyadic Social Skills Questionnaire (DSSQ: Capaldi 1994; “Say mean things about your partner behind your partner’s back”), and 1 item from the Couples Interview (Capaldi and Wilson 1994; “Name calling, threats, sulking or refusing to talk, screaming or cursing, throwing or breaking something [not at partner], during most severe fight in past year lost my temper”); (b) partner report using the 6-item psychological scale from the CTS (Straus 1979; “Threw something (but not at them) or smashed something”), 4 items from the AP (Kessler 1990; “When disagree, how often does your partner insult or swear, sulk or refuse to talk, stomp out of the room, threaten to hit?”), 10 items from the DSSQ (Capaldi and Wilson 1994; “Your partner blames you when something goes wrong”), 1 item from the Couples Interview (Capaldi and Wilson 1994; “Name calling, threats, sulking or refusing to talk, screaming or cursing, throwing or breaking something not at you”), and 16/17 items from the Partner Interaction Questionnaire (PIQ: Capaldi 1991; “Broken or damaged something of yours on purpose”); and (c) observer report measured as the mean of the 11-item psychological aggression coder ratings (“Derogatory, sarcastic to partner or called partner negative names—e.g., jerk, dummy—during task”) and the observed rate per minute of three content codes (coerce, verbal attack, and negative interpersonal) in combination with four affects (neutral, distress, aversive, and sad) derived from the FPPC coding of the discussion tasks.

In order to keep a common metric across the three indicators (e.g., self- and partner-reports and observational coding/coder ratings), response categories were rescaled to range from 1 to 5 prior to combining the indicators. For example, the CTS items were recoded from 1 to 7 to 1 to 5 (i.e., 1 = 1, 2 = 1.67, 3 = 2.33, 4 = 3, 5 = 3.67, 6 = 4.33, and 7 = 5). Scale items for the IPV indicators were then checked for internal consistency (an item-total correlation greater than .20 and an alpha of .60 or higher) before calculating the scale by taking the mean of pertinent items. Each scale was then examined for convergence with other scales from the same reporting agent (i.e., loading for each scale on a one-factor solution had to be .30 or more). Once scales met these criteria, they were combined by calculating their mean, first within reporting agent and then the mean of each agent’s global score formed the final observed construct value. Psychological IPV was measured identically across the six time points. Reliabilities (based on Cronbach’s standardized alpha) ranged from .67–.82 for men and .65–.76 for women for the CTS self-report, .73–.82 for men and .79–.85 for women for the CTS partner report, .85–.91 for men and .82–.87 for women for the DSSQ self-report, .86–.91 for men and .89–.93 for women for the DSSQ partner report, .68–.81 for the men and .74–.84 for women for the AP partner report, .79–.94 for men and .81–.91 for women for the PIQ partner report, and .90–.94 for men and .89–.94 for women for the coder ratings across the assessments. At T1 and T2, 99 % of couples reported having psychological aggression in their relationships, with 100 % of couples at T3 through T6.

Friend Stress

Friend stress was comprised of two agent indicators: self-report and observer report measured as one coder rating item on the extent to which each member of the dyad was observed to mention not liking the partner’s friends because they were a bad influence. For self-report, there were four items: two items from the Partners Interview (Capaldi and Wilson 1994; “How well do you like your partner’s friends?” and “How well does your partner like your friends?”); one item from the PIQ (Capaldi 1991; “How often has your partner told you things such as s/he dislikes your friends and that they are no good?”); and one item from the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS; Spanier 1976; “Please indicate the appropriate extent of agreement or disagreement between you and your partner regarding friends.”). Friend stress was measured identically across the six time points. Reliabilities (based on Cronbach’s standardized alpha) ranged from .65 to .76 for the men and .68 to .75 for the women across the assessments.

Parent Stress

Parent stress was comprised of self-report indicators on five items: four items from the Partners Interview (Capaldi and Wilson 1994; “How well do you get along with your mother/father figure?” and “How often do you get into an argument with your mother/father figure?”); and one item from the DAS (Spanier 1976; “Please indicate the appropriate extent of agreement or disagreement between you and your partner regarding ways of dealing with parents and/or in-laws.”). At the initial time point, parent stress was measured for the men only but thereafter was measured identically for both the men and the women across the five following time points. Reliabilities (based on Cronbach’s standardized alpha) ranged from .55 to .67 for the men and .44 to .53 for the women across the assessments.

Relationship Satisfaction

Both partners reported on their relationship satisfaction using the DAS (Spanier 1976; “How often do you discuss or have you considered divorce, separation, or terminating your relationship”). The two items used in the friend and parent stress constructs were removed from the relationship satisfaction measure yielding 30 total items. In addition, one of the items was coded from 0–4 (versus 0–6) on the version used. As a result, the range of the total score was 0–139 instead of the usual 0–151. Relationship satisfaction was measured identically across the six time points. Reliabilities (based on Cronbach’s standardized alpha) ranged from .91 to .94 for the men and .86 to .94 for the women across the assessments.

Time-Invariant Covariates (Averaged Across T1–T6)

Participants indicated their marital status, whether children (biological, step, other) were living in their home full time, and whether they had received any sources of financial aid during the Partners Interview (Capaldi and Wilson 1994). Variables were averaged over couples’ time points to form time-invariant predictors of between couples’ differences in levels and rates of change in psychological IPV (sample descriptive statistics by assessment are given in Table 1).

Relationship Status

Couples identified whether they were married (coded as 1) or non-married, which included engaged, cohabitating, or dating couples (coded as 0). An average over each couple’s assessments was then calculated to denote the proportion of times that a couple participated as married verses non-married.

Children in the Home

Participants indicated the number of children living in their home fulltime. An average over each couple’s assessments was then calculated, denoting a combination of both the number of children living in the home and the proportion of times over the assessments that couples had children.

Financial Strain

Participants indicated whether or not they had received financial aid over the last year in the form of food stamps, temporary assistance of needy families (previously called aid to families with dependent children, ADC), welfare, Medicaid, unemployment insurance, or any other source of financial aid. All six items were coded as yes = 1 and no = 0 and then summed to form financial strain scores.

Analysis Plan

This study employed latent growth curve modeling (LGC) using Mplus 7 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012) to examine longitudinal associations between interpersonal stress, relationship satisfaction, and psychological IPV. For the 196 couples, a total of 668 persons by time measurements (the sum of couples available across waves as the unit of analysis; 86 couples at T1 + 110 couples at T2 etc.) were included in the analysis. Men’s age across time was used as the time metric and was person-mean centered such that each couple’s age scores were centered at the men’s average age of participation (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002).

Preliminary analysis indicated that correlations between men’s and women’s variables revealed linear dependency for major study variables. The T1–T6 correlations ranged from r = .80 to r = .85, p < .001 for men’s and women’s psychological IPV; r = .51 to r = .67, p < .001 for men’s and women’s friend stress; r = .13 to r = .38, p = .164 to p < .001 for men’s and women’s parent stress, which was significant at all assessments except T3 (r = .13, p = .164) and T5 (r = .17, p = .06); r = .45 to r = .66, p < .001 for men’s and women’s relationship satisfaction; r = .18 to r = .30, p < .05 for men’s and women’s financial strain. To avoid multicollinearity between partners’ scores, men’s and women’s scores were averaged to create dyadic levels of psychological IPV, friend stress, parent stress, relationship satisfaction, and financial strain. All predictor variables except marital status were also grand-mean centered (i.e., averaged over all persons and time points) to reduce multicollinearity among the predictor variables and ease the interpretation of the effects to correspond to couples exhibiting average levels of friend stress (1.66), parent stress (1.79), relationship satisfaction (103.59), number of children living in the home (0.86), and financial strain (0.38) (Cohen et al. 2003). Intercept effects, therefore, denote associations among the variables for non-married couples in the middle of the time period when the men were on average age 27 years.

To examine whether and when interpersonal stress increased the likelihood of couples’ psychological IPV (while controlling for couples’ marital status, children in the home, and financial strain), two sets of linear LGC modeling were conducted: (a) developmental process models to determine the association between couples’ friend and parent stress and psychological IPV while controlling for couples’ relationship satisfaction and (b) time-specific proximal effects models to determine whether the effects of couples’ friend and parent stress, relationship satisfaction, and the interaction between stress and satisfaction on couples’ psychological IPV varied over time. Separate models were run for friend stress and parent stress. Note that couples’ levels of relationship satisfaction were negatively associated at T1–T6 with friend stress (correlations ranging from r = −.60 to r = −.48, p < .001) and parent stress (correlations ranging from r = −.55 to r = −.25, p = .006 to p < .001). In the developmental process models, the association between couples’ stress and relationship satisfaction were accounted for by correlating the intercepts and slopes of stress and relationship satisfaction. In the time-specific proximal effects models, stress and relationship satisfaction were correlated within concurrent time points but constrained to be equal across time (i.e., a single correlation coefficient was estimated for T1–T6). Stress and relationship satisfaction were also allowed to correlate with the stress by satisfaction interaction term, which was also constrained to be equal across time.

Results

Unconditional Latent Growth Curve Models of Couples’ Psychological IPV, Interpersonal Stress, and Relationship Satisfaction

As an initial step, four unconditional linear LGC models were fit separately to the couples’ trajectories of psychological IPV, friend stress, parent stress, and relationship satisfaction. All models allowed for random intercept and slope parameters that were not allowed to correlate, and the manifest variances were constrained to be equal across all six time points. Whereas friend stress and relationship satisfaction were found to exhibit significant average linear decreases over time (b = −.016, p < .001 and b = −.593, p < .001, respectively), the average slope terms for psychological IPV and parent stress were nonsignificant, indicating that couples overall did not increase or decrease in their psychological IPV or parent stress over the 12-year period (b = .004, p = .568 and b = −.006, p = .106, respectively). All models, except parent stress, showed significant variability in both the random slope and intercept parameters, indicating variation in the couples’ linear rates of change and levels for friend stress (s2 = .001, p = .002 and s2 = .101, p < .001), relationship satisfaction (s2 = 1.144, p = .036 and s2 = 162.231, p < .001), and psychological IPV (s2 = .001, p = .016 and s2 = .242, p <.001). The parent stress model only showed significant variability in the random intercept parameter (s2 = .095, p <.001) and not the slope parameter (s2 = .000, p = .284). Means and standard deviations for the time-varying variables can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations of time-variant variables

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological IPV | 2.2 (.64) | 2.1 (.62) | 2.0 (.57) | 2.0 (.60) | 2.0 (.55) | 2.0 (.62) |

| Friend stress | 1.8 (.48) | 1.7 (.41) | 1.7 (.37) | 1.6 (.38) | 1.6 (.35) | 1.6 (.36) |

| Parent stress | 1.9 (.44)a | 1.8 (.41) | 1.8 (.34) | 1.8 (.39) | 1.7 (.36) | 1.7 (.38) |

| Relationship satisfaction | 103.0 (15.0) | 102.0 (16.3) | 105.1 (14.9) | 103.7 (16.3) | 103.3 (14.7) | 104.1 (13.4) |

Parent stress score at T1 based on men’s scores alone. All other variables denote averages of men’s and women’s scores

Developmental Process Models of Couples’ Interpersonal Stress, Relationship Satisfaction, and Psychological IPV

For friend stress and parent stress separately, a series of developmental process models were run: (a) a linear LGC model in which couples’ intercept and slope parameters of psychological IPV were predicted by the intercept and slope parameters of stress only, (b) a linear LGC model in which couples’ intercept and slope parameters of psychological IPV were predicted by the intercept and slope parameters of relationship satisfaction only, and (c) a final linear LGC model in which couples’ intercept and slope parameters of psychological IPV trajectories were predicted by the intercept and slope parameters of stress while controlling for couples’ trajectories of relationship satisfaction, average marital status, children in the home, and financial strain. Only final models are presented (see Table 3 for model parameter estimates and information criteria).

Table 3.

Developmental processes models of couples’ psychological IPV predicted by friend and parent stress, controlling for couples’ relationship satisfaction trajectories, average marital status, children in the home, and financial strain

| Psychological IPV predicted by | Friend stress controlling for satisfaction | Parent stress controlling for satisfaction |

|---|---|---|

| Information criteria | ||

| AIC | 6,143.489 | 6,266.387 |

| BIC | 6,231.998 | 6,354.896 |

| Adjusted BIC | 6,146.465 | 6,269.363 |

| Fixed effects | ||

| Intercept | ||

| Stress | 0.030 | 0.030 |

| Satisfaction | −1.328 | −1.317 |

| IPV | 1.969*** | 1.985*** |

| Slope | ||

| Stress | −0.011* | −0.004 |

| Satisfaction | −0.687*** | −0.704*** |

| IPV | −0.001 | −0.014 |

| Prediction of IPV intercept | ||

| Stress intercept | 0.603*** | 0.257* |

| Satisfaction intercept | −0.019*** | −0.025*** |

| Children in home | 0.063M | 0.079* |

| Marital status | 0.076 | 0.046 |

| Financial strain | −0.003 | 0.052 |

| Prediction of IPV slope | ||

| Stress intercept | 0.452** | −0.181 |

| Satisfaction slope | −0.026*** | −0.038*** |

| Children in home | 0.001 | −0.001 |

| Marital status | −0.009 | −0.010 |

| Financial stain | −0.013 | −0.018 |

| Variance at T1–T6 | ||

| Stress | 0.046*** | 0.057*** |

| Satisfaction | 64.843*** | 63.839*** |

| IPV | 0.113*** | 0.115*** |

| Random effects (variance estimates) | ||

| Intercept | ||

| Stress | 0.103*** | 0.096*** |

| Satisfaction | 163.908*** | 166.011*** |

| IPV | 0.082*** | 0. 095*** |

| Slope | ||

| Stress | 0.001*** | 0.000* |

| Satisfaction | 1.490** | 1.478** |

| IPV | 0.000*** | 0.000*** |

| Covariance | ||

| Intercepts | ||

| Stress and satisfaction | −2.907*** | −2.243*** |

| Slopes | ||

| Stress and satisfaction | −0.038*** | −0.017** |

p < .10;

p < .05;

p <.01;

p < .001

The friend stress model revealed that, on average, couples’ levels and rates of change in psychological IPV were significantly predicted from friend stress (b = .603, p < .001 for the intercept and b = .452, p = .001 for the slope) and relationship satisfaction (b = −.019, p < .001 for the intercept and b = −.026, p < .001 for the slope). Couples’ levels and rates of change in friend stress positively predicted the levels and rates of change in psychological IPV, even when accounting for relationship satisfaction and between-couple differences in marital status, children in the home, and financial strain. In the parent stress model, higher levels of parent stress predicted higher levels of psychological IPV when the men were on average age 27 years (b = .257, p = .046 for the intercept). Couples’ rates of change in parent stress, however, did not predict rates of change in psychological IPV (b = −.181, p = .546 for the slope). Relationships satisfaction was a significant predictor of couples’ psychological IPV (b = −.025, p < .001 for the intercept and b = −.038, p < .001 for the slope). Note also that the couples’ relationship satisfaction intercepts were significantly associated with couples’ friend stress intercepts and slopes (covariance = −2.907, p < .001; covariance = −.038, p < .001, respectively) and couples’ parent stress intercepts and slopes (covariance = −2.243, p < .001; covariance = −.017, p = .008, respectively). Couples who experienced more friend and parent stress also experienced less relationship satisfaction, and increases in couples’ friend and parent stress were associated with decreases in relationship satisfaction.

Regarding the time-invariant covariates in the developmental process models, in the parent stress model, on average, couples with more children were found to have had significantly higher levels of psychological IPV when the men were on average age 27 years compared to couples with fewer children (b = .079, p = .029); in the friend stress model, the intercept effect of children in the home was found to be marginally predictive of couples’ levels of psychological IPV (b = .063, p = .090). However, neither marital status nor financial strain significantly predicted couples’ levels of psychological IPV in the parent stress model (b = .046, p = .566 and b = .052, p = .448, respectively) or the friend stress model (b = .076, p = .314 and b = −.003, p = .963, respectively). Likewise, in both the parent and friend stress models, couples’ rates of change in psychological IPV were not significantly predicted by any of the time-invariant predictors of children in the home (b = −.001, p = .918 and b = .001, p = .915, respectively), marital status (b = −.010, p = .498 and b = −.009, p = .521, respectively) or financial strain (b = −.018, p = .208 and b = −.013, p = .315, respectively).

Time-Specific Proximal Effects Models of Couples’ Interpersonal Stress, Relationship Satisfaction, and Psychological IPV

For friend stress and parent stress separately, a series of time-specific proximal effects models were run: (a) a linear LGC model of couples’ psychological IPV with time-varying covariates of stress only, (b) a linear LGC model of couples’ psychological IPV with time-varying covariates of relationship satisfaction only, and (c) a final linear LGC model of couples’ psychological IPV with time-varying covariates of stress, relationship satisfaction, and the interaction between stress and satisfaction while also controlling for couples’ average marital status, children in the home, and financial strain. Only final models are presented (see Table 4 for model parameter estimates and information criteria). Whether the effect of couples’ stress on psychological IPV varied over the 12-year period was determined using the scaled Chi Square Difference Test, which compares the change in overall model fit of two nested models (denoted as TRd) (Satorra and Bentler 2011). In this case, the model that constrained the effect of stress on psychological IPV to be equal over time was compared to the model that did not constrain the effect to be equal across the six time points.

Table 4.

Time-specific proximal effects models of couples’ psychological IPV predicted by time-varying predictor variables of friend and parent stress and relationship satisfaction, controlling for average marital status, children in the home, and financial strain

| Psychological IPV predicted by | Friend stress, satisfaction, and interaction | Parent stress, satisfaction, and interaction |

|---|---|---|

| Information criteria | ||

| AIC | 10,977.606 | 11,042.551 |

| BIC | 11,151.346 | 11,216.291 |

| Adjusted BIC | 10,983.447 | 11,048.392 |

| Fixed effects | ||

| Intercept of IPV | 2.005*** | 2.018*** |

| Slope of IPV | 0.001 | −0.009 |

| Prediction of IPV intercept | ||

| Children in home | 0.081* | 0.078* |

| Marital status | 0.011 | 0.008 |

| Financial strain | 0.069 | 0.123 |

| Prediction of IPV slope | ||

| Children in home | 0.001 | −0.001 |

| Marital status | −0.013 | −0.004 |

| Financial strain | −0.003 | −0.025M |

| Stress | ||

| T1 stress | 0.553*** | −0.055 |

| T2 stress | 0.439*** | 0.076 |

| T3 stress | 0.518*** | 0.024 |

| T4 stress | 0.225M | −0.040 |

| T5 stress | −0.019 | 0.005 |

| T6 stress | 0.099 | 0.042 |

| Relationship satisfaction | ||

| T1 satisfaction | −0.018*** | −0.023*** |

| T2 satisfaction | −0.016*** | −0.019*** |

| T3 satisfaction | −0.011*** | −0.017*** |

| T4 satisfaction | −0.018*** | −0.020*** |

| T5 satisfaction | −0.021*** | −0.020*** |

| T6 satisfaction | −0.023*** | −0.024*** |

| Stress by relationship satisfaction | ||

| T1 stress by satisfaction | 0.013* | 0.007 |

| T2 stress by satisfaction | 0.010* | 0.003 |

| T3 stress by satisfaction | 0.000 | −0.003 |

| T4 stress by satisfaction | 0.005 | 0.002 |

| T5 stress by satisfaction | 0.000 | 0.005 |

| T6 stress by satisfaction | −0.004 | −0.005 |

| T1–T6 covariance between predictors | ||

| Stress with satisfaction | −3.197*** | −2.140*** |

| Stress with stress by satisfaction | −0.681** | −0.035 |

| Satisfaction with stress by satisfaction | 26.512** | 4.534 |

| T1–T6 variance | ||

| Stress | 0.150*** | 0.145*** |

| Satisfaction | 227.759*** | 227.759*** |

| Stress by satisfaction | 41.982*** | 32.205*** |

| IPV | 0.098*** | 0.103*** |

| Random effects (variance estimates) | ||

| IPV intercept | 0.107*** | 0.121*** |

| IPV slope | 0.000 | 0.000 |

p < .10;

p < .05;

p <.01;

p < .001

Time-Specific Proximal Effects Friend Stress Model

A significant improvement in overall model fit was attained when the effect of couples’ friend stress on their psychological IPV was allowed to vary over time (TRd [5] = 18.022, p = .003), suggesting that the effect of couples’ friend stress on psychological IPV varied depending on the men’s ages. Couples’ friend stress significantly predicted psychological IPV at the first three time points only (for T1–T3, b = .553, .439, .518, p < .001), indicating that couples who experienced more friend stress when the men were approximately 21.5 to 26 years were also likely to experience more psychological IPV. Couples’ relationship satisfaction significantly predicted psychological IPV at all time points (for T1–T6, range of b = −.023 to b = −.011, p < .001), indicating that as relationship satisfaction decreased psychological IPV increased over time. The interaction term was significant at the first two time points only (b = .013, p = .022 and b = .010, p = .034); thus, the extent to which couples’ psychological IPV increased in early adulthood when the men were approximately ages 21.5 and 24 years was dependent not only on how much friend stress the couples experienced but also on how satisfied the couples were with their relationships.

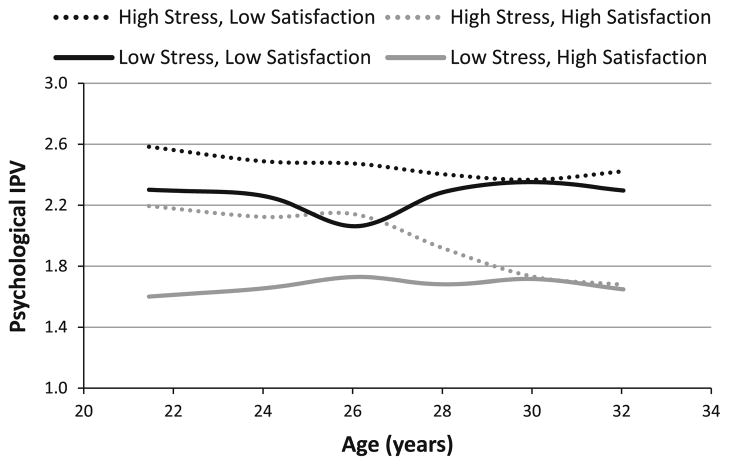

The predicted psychological IPV scores for couples experiencing one standard deviation above or below the average levels of friend stress and relationship satisfaction are depicted in Fig. 1. Low levels of relationship satisfaction and high levels of friend stress predicted high levels of couples’ psychological IPV and high levels of relationship satisfaction and low levels of friend stress predicted low levels of psychological IPV. The co-occurrence of high friend stress and low relationship satisfaction in couples’ relationships predicted high levels of psychological IPV only in early adulthood when the men were in their early to mid 20s. As the men reached their 30s, no differences existed in couples’ predicted psychological IPV depending on level of friend stress, and relationship satisfaction became the best predictor of couples’ psychological IPV.

Fig. 1.

Couples’ predicted psychological IPV by friend stress and relationship satisfaction. Note. The predicted psychological IPV scores were one standard deviation above or below the average levels of friend stress and relationship satisfaction

Time-Specific Proximal Effects Parent Stress Model

When the effect of couples’ parent stress on their psychological IPV was allowed to vary over time, the improvement in overall model fit was not significant (TRd [5] = .269, p = .998), providing no support that the effect of couples’ parent stress on psychological IPV varied depending on the men’s ages. Moreover, couples’ relationship satisfaction was the only significant time-varying predictor of couples’ psychological IPV (for T1–T6, range of b = −.024 to b = −.017, p < .001), indicating that over the years when couples were more satisfied they engaged in less psychological IPV. Both the main effect of parent stress (for T1–T6, range of b = −.055 to b = .076, p = .472 to .963) and the interaction of parent stress by relationship satisfaction (for T1–T6, range of b = −.005 to b = .007, p = .308–.754) were not significant time-varying effects of couples’ psychological IPV at T1–T6.

Regarding the time-invariant covariates in the friend stress and parent stress time-specific proximal effects models, similar to the previous developmental process models, the only significant predictor of couples’ psychological IPV intercepts was the average number of children living in the home (b = .081, p = .025 and b = .078, p = .033, respectively), indicating that the more children that couples had the more psychological IPV couples experienced when the men were on average age 27 years. The other time-invariant effects were nonsignificant predictors of couples’ psychological IPV intercepts in the friend stress and parent stress models (for marital status: b = .011, p = .887 and b = .008, p = .923, respectively; for financial strain, b = .069, p = .377 and b = .123, p = .101, respectively). Also in the friend stress and parent stress models, couples’ rates of change in psychological IPV were not significantly predicted by any of the time-invariant predictors of children in the home (b = .001, p = .795 and b = −.001, p = .826, respectively), marital status (b = −.013, p = .390 and b = −.004, p = .818, respectively), or financial strain (b = −.003, p = .837 and b = −.025, p = .099, respectively).

Discussion

Intimate partner violence in young men and women’s romantic relationships is a significant public health problem due to its high prevalence, adverse physical and mental health consequences, and status as a precursor to future violence (e.g., Breiding et al. 2008; Coker et al. 2002; Shorey et al. 2008; White 2009). The current study helps elucidate the associations between couples’ interpersonal stress, relationship satisfaction, and psychological IPV that take place at the transition from adolescence into young adulthood when the couples were in their early 20s to early to midadulthood when the couples were in their early 30s. Findings from the current study indicated that couples’ interpersonal stress related to not liking their partners’ friends and relationships with parents was an important contextual factor related to couples’ psychological IPV in early adulthood and that couples’ friend and parent stress was associated with the likelihood of couples’ psychological IPV over time. Couples’ trajectories of psychological IPV were relatively stable over a 12-year time span, with high prevalence rates of 99 to 100 % of any such IPV but with significant variability to be explained. As hypothesized, couples experiencing high levels of friend and parent stress were more likely to engage in high levels of psychological IPV and increases in couples’ friend stress (not parent stress) predicted increases in couples’ IPV over time, even when accounting for the couples’ relationship satisfaction, children in the home, marital status, and financial strain.

This study was unique in its inclusion of interactive and time-specific proximal effects. Interactive effects were at play when the couples were in their early to mid 20s with couples most at risk for increases in psychological IPV if they experienced both high friend stress and low relationship satisfaction. This suggests that the effect of couples’ friend stress on psychological IPV varied according to the couples’ ages and how satisfied the couples were with their relationships, highlighting the potential moderating effect of couples’ relationship satisfaction on the association between friend stress and psychological IPV. Thus far, there has been relatively little research directed at understanding how couples’ relationship satisfaction may interact with other relationship variables such as stress in impacting IPV (Stith et al. 2008), and the findings of the current study indicates that this is an oversight.

As hypothesized, couples’ friend stress predicted psychological IPV at younger ages when the couples were in their early to mid 20s only. Couples’ friend stress was also at its peak when the couples were in their early 20s, as indicated by the couples’ trajectories of friend stress that decreased over time. Thereby, couples’ friend stress had the greatest effect on psychological IPV in early adulthood when levels of friend stress were high. It may be that by the late 20s and 30s men and women spend less time with their friends as the demands of home and children take more of their time. Indeed, the young men and women who participated in the National Youth Survey reported spending about 50 % less time with peers in general and significantly less time with delinquent friends after marriage in comparison to their unmarried peers (Rhule-Louie and McMahon 2007; Warr 1998). Further, as men and women tend to show significant decreases in antisocial behaviors across their 20s (e.g., Wiesner et al. 2007), they may be less likely to engage in behaviors, such as drinking in bars with friends, that are bothersome to their partners and thus likely to cause stress. Couples also may change their network of friends over the years to become more interdependent. In fact, a failure to increase overlap between family and friend networks for newlywed couples was associated with relationship dissatisfaction at the first anniversary for the wives (Kearns and Leonard 2004).

In contrast to friend stress, couples’ rates of change in parent stress did not predict rates of change in psychological IPV, and no interactive effects emerged between couples’ levels of parent stress and relationship satisfaction in predicting IPV, suggesting the salience of friend stress as a contextual factor over parent stress. Given the parallels in function and similarity in experiences with friends and romantic partners during adolescence and emerging adulthood, it follows that friends may influence romantic relationships and thereby IPV more strongly during this period compared to parents (Linder and Collins 2005). Romantic partners also usually are selected from the peer group and often met through or with friends, leading to assortative partnering (Kim and Capaldi 2004). As the couples in this study reached their 30s and couples’ trajectories of relationship satisfaction declined, low relationship satisfaction was the leading predictor of couples’ psychological IPV. Early adulthood has been characterized as a period in which the influence of romantic partners becomes more salient than that of friends (Meeus et al. 2007). This shift is reflected in this study with processes in the relationship context such as relationship satisfaction being more influential on IPV than interpersonal stress from friends or parents. It is also possible that other relationship influences from friends and parents on couples’ IPV are mediated through couples’ relationship satisfaction. Consistent with previous work (e.g., Schumacher and Leonard 2005; Shortt et al. 2010), couples who were not satisfied in their relationships were more likely to exhibit psychological IPV with each other across the couples’ ages.

These findings extend the work of previous studies (e.g., Frye and Karney 2006) on the extent to which couples’ stressful experiences, originating outside the couple, impact relationship functioning by increasing maladaptive interactions such as psychological IPV. Consistent with the developmental systems perspective (e.g., Capaldi et al. 2004, 2005), this study illustrates how understanding IPV necessitates knowledge of the contexts in which couples’ interactions are embedded and that antecedents and risk factors of IPV may be found in couples’ external contexts. In this study, not liking the other partner’s friends and perceiving partner’s friends to be negative influences turned out to be a source of stress that couples must contend with as a dyad and puts couples at risk for psychological IPV. Identifying stress due to friends as a predictor of couples’ psychological IPV augments the limited information available on friend predictors of IPV in early adulthood beyond peer predictors identified in adolescence, such as having aggressive friends and delinquent peer affiliation (Olsen et al. 2010; Vézina et al. 2011). Clearly, additional research on the role that friends play in couples’ IPV is warranted, including specifying possible mechanisms in operation regarding the associations between couples’ stress and IPV. Although a relatively small sample size precluded us from examining individual mechanisms, the most common reasons given by the couples for disliking friends were minor unskilled behaviors (e.g., dishonest; 15 %), substance use (14 %), negative influence on partner (14 %), and attitudes and behaviors toward others (e.g., arrogant; 7 %).

There are other limitations to this study to mention. The measurement of friend and parent stress was restrictive in number of items available. Because of potentially important differences between psychological and physical IPV that exist in prevalence, stability, and desistence (Fritz and O’Leary 2004; Lawrence et al. 2009; Shorey et al. 2008; Shortt et al. 2012), for clarity, the modeling focused on psychological IPV and did not include physical IPV. The use of dyadic variables due to the high correlation between men and women’s scores (e.g., psychological IPV) precluded examination of gender effects in the modeling and gender differences in the associations between interpersonal stress, relationship satisfaction, and psychological IPV. Also regarding the modeling, it is possible that null effects found in the parent stress models were due to insufficient power. Lastly, the couples in the current study were largely from a lower socioeconomic status and predominantly European American. Thus, the findings of this study may not generalize to couples of higher socioeconomic status and other racial/cultural backgrounds.

In conclusion, this study broadens the empirical base on longitudinal predictors and course of IPV and increases the knowledge on empirically supported models of risk factors needed to develop effective IPV prevention programs (Langhinrichsen-Rohling and Capaldi 2012). The evidence that couples’ stress related to friends and parents increased the likelihood of couples’ IPV in early adulthood has several implications. The stability or continuity of psychological IPV over time in couples’ relationships indicates that preventing IPV or intervening early before IPV becomes an interaction pattern is advised (Shortt et al. 2012). Focusing on dyadic processes and the behavior of both partners also will be necessary in order to reduce IPV (Stith and McCollum 2009). However, teaching couples adaptive relationship behaviors may not be enough to improve relationship functioning if couples’ relationships are taking place in contexts containing many stressors such as friend and parent stress. With stress interfering with and depleting couples’ capacities to engage in relationship-promoting behaviors (e.g., Buck and Neff 2012), it may be helpful for couples also to learn how to manage stress and how to navigate the positive and negative experiences each partner brings into the relationship on a daily basis. There is some evidence suggesting that couples’ dyadic coping strategies can be helpful in reducing the effects of stress on couples’ psychological IPV (Bodenmann et al. 2010). Recent research suggests that couples can learn to be stress resilient, and stress under certain conditions can serve to enhance couples relationship functioning and stability (Neff and Broady 2011). As indicated by the current study, friends and parents can be a source of stress to couples in early adulthood and an intervention component on issues related to friends, parents, and other stress sources could be effective in reducing maladaptive relationship functioning such as IPV. Identifying contextual factors such as interpersonal stress that increase the likelihood of couples’ IPV can provide a more complete understanding of IPV and inform prevention and intervention efforts to promote healthy nonviolent romantic relationships.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the couples for their participation, Jane Wilson for coordinating the project, and Sally Schwader for editorial assistance. The project described was supported by Award Number R01 HD 46364 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or National Institutes of Health.

Biographies

Joann Wu Shortt received her Ph.D. from the University of Washington and is a Research Scientist at the Oregon Social Learning Center (www.oslc.org). Shortt investigates how relationships and emotions shape our development across the lifespan. She has been a co-investigator on the Oregon Youth Study-Couples Study for over 10 years. A recent paper from this study found higher stability in intimate partner violence (IPV) for men who stayed with the same partners and that the IPV of new partners was linked to changes in men’s IPV.

Deborah M. Capaldi received her Ph.D. in Developmental Psychology from the University of Oregon and is a Senior Scientist at the Oregon Social Learning Center. Her research involves lifespan risk factors related to antisocial behavior, substance use, and couples’ adjustment, including intimate partner violence. She developed the Dynamic Developmental Systems Model and is the Principal Investigator of the Oregon Youth Study-Couples Study.

Hyoun K. Kim received her Ph.D. from the Ohio State University and is a Research Scientist at the Oregon Social Learning Center. Her research involves the development of health-risking behaviors (drug use, risky sexual behaviors, delinquent behavior, and intimate partner violence [IPV]) in adolescents and young adults from at-risk backgrounds. She has been a co-investigator on the Oregon Youth Study-Couples Study for over 10 years and has published on IPV and young couples adjustment in multiple journals.

Stacey S. Tiberio earned her doctorate in Quantitative Psychology from the University of Notre Dame and is currently a data analyst at the Oregon Social Learning Center. Her major research interests include longitudinal modeling of the internal and external dynamics of psychological processes.

Footnotes

Author contributions JWS took the lead in the current study’s conceptualization, research design, and data analysis, drafted and revised the manuscript. DMC participated in study conceptualization, design, and manuscript preparation. HKK contributed to conceptualization, analysis plan, and manuscript preparation. SST contributed to construct building, analysis plan, and model refinements, carried out the analyses, co-drafted the Methods and Results sections, reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Contributor Information

Joann Wu Shortt, Email: joanns@oslc.org.

Deborah M. Capaldi, Email: deborahc@oslc.org.

Hyoun K. Kim, Email: hyounk@oslc.org.

Stacey S. Tiberio, Email: staceyt@oslc.org.

References

- Bodenmann G. Dyadic coping and its significance for marital functioning. In: Revenson T, Kayser K, Bodenmann G, editors. Couples coping with stress: Emerging perspectives on dyadic coping. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. pp. 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G, Meuwly N, Bradbury TN, Gmelch S, Ledermann T. Stress, anger, and verbal aggression in intimate relationships: Moderating effects of individual and dyadic coping. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2010;27:408–424. [Google Scholar]

- Breiding MJ, Black MC, Ryan GW. Chronic disease and health risk behaviors associated with intimate partner violence—18 U.S. states/territories, 2005. Annals of Epidemiology. 2008;18:538–544. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck AA, Neff LA. Stress spillover in early marriage: The role of self-regulatory depletion. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0029260. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM. Unpublished instrument. Eugene: Oregon Social Learning Center; 1991. Partner interaction questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM. Unpublished Questionnaire. Eugene: Oregon Social Learning Center; 1994. Dyadic social skills questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Kim HK, Shortt JW. Women’s involvement in aggression in young adult romantic relationships: A developmental systems model. In: Putallaz M, Bierman KL, editors. Aggression, antisocial behavior, and violence among girls: A developmental perspective. New York: Guilford; 2004. pp. 223–241. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Kim HK, Shortt JW. Observed initiation and reciprocity of physical aggression in young, at-risk couples. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:101–111. doi: 10.1007/s10896-007-9067-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, Kim HK. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:231–280. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J. Informing intimate partner violence prevention efforts: Dyadic, developmental, and contextual considerations. Prevention Science. 2012;13:323–328. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0309-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi JM, Shortt JW, Crosby L. Aggression in at-risk young couples: Stability, change, and prediction to relationship dissolution. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Shortt JW, Crosby L. Physical and psychological aggression in at-risk young couples: Stability and change in young adulthood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2003;49:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Shortt JW, Kim HK. A life span developmental systems perspective on aggression toward a partner. In: Pinsof W, Lebow JL, editors. Family psychology: The art of the science. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 141–167. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Wilson J. Unpublished questionnaire. Oregon Social Learning Center; 1994. The Partners interview. [Google Scholar]

- Carney MM, Barner JR. Prevalence of partner abuse: Rates of emotional abuse and control. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:286–335. [Google Scholar]

- Casey EA, Beadnell B. The structure of male adolescent peer networks and risk for intimate partner violence perpetration: Findings from a national sample. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:620–633. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9423-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Cohen J, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral analysis. 3. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, Desai S, Sanderson M, Brandt HM, et al. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;23:260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Durtschi JA, Donnellan MB, Lorenz FO, Conger RD. Intergenerational transmission of relationship aggression: A prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:688–697. doi: 10.1037/a0021675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Schafer J. Socioeconomic predictors of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Journal of Family Violence. 2002;17(4):377–389. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes E, Chen H, Johnson J. Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: A 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:741–753. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz PA, O’Leary KD. Physical and psychological partner aggression across a decade: A growth curve analysis. Violence and Victims. 2004;19:3–16. doi: 10.1891/088667004780842886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye NE, Karney BR. The context of aggressive behavior in marriage: A longitudinal study of newlyweds. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:12–20. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Unpublished manuscript. A. B. Hollingshead, Department of Sociology, Yale University; New Haven, CT: 1975. Four factor index of social status. [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Story LB, Bradbury TN. Marriages in context: Interactions between chronic and acute stress among newlyweds. In: Revenson TA, Kayser K, Bodenmann G, editors. Couples coping with stress: Emerging perspectives on dyadic coping. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. pp. 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kearns JN, Leonard KE. Social networks, structural interdependence, and marital quality over the transition to marriage: A prospective analysis. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:383–395. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.2.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. The national comorbidity survey. DIS Newsletter. 1990;7(12):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Capaldi DM. The association of antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms between partners and risk for aggression in romantic relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:82–96. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer A, Lawrence E, Barry RA. Using a vulnerability-stress-adaptation framework to predict physical aggression trajectories in newlywed marriage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:756–768. doi: 10.1037/a0013254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Capaldi DM. Clearly we’ve only just begun: Developing effective prevention programs for intimate partner violence. Prevention Science. 2012;13:410–414. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0310-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence E, Yoon J, Langer A, Ro E. Is psychological aggression as detrimental as physical aggression? The independent effects of psychological aggression on depression and anxiety symptoms. Violence and Victims. 2009;24:20–35. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.24.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder JR, Collins WA. Parent and peer predictors of physical aggression and conflict management in romantic relationships in early adulthood. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:252–262. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R, Jouriles EN, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Caetano R. Estimating the number of American children living in partner-violent families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:137–142. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeus WHJ, Branje SJT, van der Valk I, de Wied M. Relationships with intimate partner, best friend, and parents in adolescence and early adulthood: A study of the saliency of the intimate partnership. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2007;31(6):569–580. [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Gorman-Smith D, Sullivan T, Orpinas P, Simon TR. Parent and peer predictors of physical dating violence perpetration in early adolescence: Tests of moderation and gender differences. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38:538–550. doi: 10.1080/15374410902976270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 7. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Neff LA. Putting marriage in its context: The influence of external stress on early marriage development. In: Campbell L, Loving TJ, editors. Interdisciplinary research on close interdisciplinary relationships: The case for integration. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2012. pp. 179–203. [Google Scholar]

- Neff LA, Broady EF. Stress resilience in early marriage: Can practice make perfect? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;101:1050–1067. doi: 10.1037/a0023809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff LA, Karney BR. How does context affect intimate relationships? Linking external stress and cognitive processes within marriage. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:134–148. doi: 10.1177/0146167203255984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff LA, Karney BR. Stress crossover in newlywed marriage: A longitudinal and dyadic perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:594–607. [Google Scholar]

- Neff LA, Karney BR. Stress and reactivity to daily relationship experiences: How stress hinders adaptive processes in marriage. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97:435–450. doi: 10.1037/a0015663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD. Psychological abuse: A variable deserving critical attention in domestic violence. In: O’Leary KD, Maiuro RD, editors. Psychological abuse in violent domestic relations. New York: Springer; 2001. pp. 3–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen JP, Parra GR, Bennett SA. Predicting violence in romantic relationships during adolescence and emerging adulthood: A critical review of the mechanisms by which familial and peer influences operate. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:411–422. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall AK, Bodenmann G. The role of stress on close relationships and marital satisfaction. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rhule-Louie DM, McMahon RJ. Problem behavior and romantic relationships: Assortative mating, behavior contagion, and desistance. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2007;10(1):53–100. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0016-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ro E, Lawrence E. Comparing three measures of psychological aggression: Psychometric properties and differentiation from negative communication. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:575–586. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler P. Scaling corrections for statistics in covariance structure analysis. University of California Los Angeles: Department of Statistics; 2011. Retrieved from http://escholarship.org/uc/item/8dv7p2hr. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz MS, Cowan PA, Cowan CP, Brennan RT. Coming home upset: Gender, marital satisfaction, and the daily spillover of workday experience into couple interactions. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:250–263. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Leonard KE. Husbands ‘and wives’ marital adjustment, verbal aggression, and physical aggression as longitudinal predictors of physical aggression in early marriage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:28–37. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Cornelius TL, Bell KM. A critical review of theoretical frameworks for dating violence: Comparing the dating and marital fields. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2008;13:185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Shortt JW, Capaldi DM, Kim HK, Kerr DCR, Owen LD, Feingold A. Stability of intimate partner violence by men across 12 years in young adulthood: Effects of relationship transitions. Prevention Science. 2012;13:360–369. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0202-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortt JW, Capaldi DM, Kim HK, Laurent HK. The effects of intimate partner violence on relationship satisfaction over time for young at risk couples: The moderating role of observed negative and positive affect. Partner Abuse. 2010;1(2):131–151. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.1.2.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortt JW, Capaldi DM, Kim HK, Owen LD. Relationship separation for young, at-risk couples: Prediction from dyadic aggression. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:624–631. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Amanor-Boadu Y, Strachman Miller M, Menhusen E, Morgan C. Vulnerabilities, stressors, and adaptations in situationally violent relationships. Family Relations. 2011;60:73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Green NM, Smith DB, Ward DB. Marital satisfaction and marital discord as risk markers for intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Family Violence. 2008;23:149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, McCollum EE. Couples treatment for psychological and physical aggression. In: O’Leary KD, editor. Psychological and physical aggression in couples: Causes and interventions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. pp. 233–250. [Google Scholar]

- Story LB, Repetti R. Daily occupational stressors and marital behavior. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:690–700. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The conflict tactics (CT) scale. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs J, Crosby L, Forgatch M, Capaldi DM. Family and peer process code: Training manual: A synthesis of three OSLC behavior codes. Eugene: Oregon Social Learning Center; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, O’Farrell TJ, Torres SE, Panuzio J, Monson CM, Murphy M, et al. Examining the correlates of psychological aggression among a community sample of couples. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:581–588. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vézina J, Hébert M, Poulin F, Lavoie F, Vitaro F, Tremblay RE. Risky lifestyle as a mediator of the relationship between deviant peer affiliation and dating violence victimization among adolescent girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:814–824. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9602-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warr M. Life course transitions and the desistance from crime. Criminology. 1998;36:183–216. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker DJ, Morrison S, Lindquist C, Hawkins SR, O’Neil JA, Nesius AM, et al. A critical review of interventions for the primary prevention of perpetration of partner violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2006;11:151–166. [Google Scholar]

- White JW. A gendered approach to adolescent dating violence: Conceptual and methodological issues. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2009;33:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner M, Capaldi DM, Kim HK. Arrest trajectories across a 17-year span for young men: Relation to dual taxonomies and self-reported offense trajectories. Criminology. 2007;45:835–863. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2007.00099.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]