Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by the presence in the brain of amyloid plaques, consisting predominately of the amyloid β peptide (Aβ), and neurofibrillary tangles, consisting primarily of tau. Hyper-phosphorylated-tau (p-tau) contributes to neuronal damage, and both p-tau and total-tau (t-tau) levels are elevated in AD cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) compared to cognitively normal controls. Our hypothesis was that increased ratios of CSF phosphorylated-tau levels relative to total-tau levels correlate with regulatory region genetic variation of kinase or phosphatase genes biologically associated with the phosphorylation status of tau. Eighteen SNPs located within 5′ and 3′ regions of 5 kinase and 4 phosphatase genes, as well as two SNPs within regulatory regions of the MAPT gene were chosen for this analysis. The study sample consisted of 101 AD patients and 169 cognitively normal controls. Rs7768046 in the FYN kinase gene and rs913275 in the PPP2R4 phosphatase gene were both associated with CSF p-tau and t-tau levels in AD. These SNPs were also differentially associated with either CSF t-tau (rs7768046) or CSF p-tau (rs913275) relative to t-tau levels in AD compared to controls. These results suggest that rs7768046 and rs913275 both influence CSF tau levels in an AD-associated manner.

Keywords: FYN, PPP2R4, MAPT, AD, CSF

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease is definitively diagnosed at autopsy according to the level and distribution of both amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) in the brain [Braak and Braak, 1991]. NFTs consist primarily of insoluble hyperphosphorylated microtubule-associated protein tau. Tau is a cytosolic protein expressed in neurons where it is involved in the stabilization of microtubules in the axon. Tau protein activity is post-translationally modulated by phosphorylation at multiple sites [Sato-Harada et al., 1996]. The list of kinases and phosphatases that actively phosphorylate and de-phosphorylate tau is long and constantly evolving [Hanger et al., 2009; Spires-Jones et al., 2009; Martin et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012]. Hyperphosphorylation of tau destabilizes the microtubule network which impairs axonal transport and leads to NFT formation and neuronal death [Hanger et al., 2009; Spires-Jones et al., 2009; Martin et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012].

The influence of phosphorylated-tau (p-tau) on neurodegeneration is thought to be due to a loss of a functional (and/or the gain of a toxic functional) mechanism which leads to the generation of multimeric intraneuronal phosphorylated tau species. As many as 85 putative phosphorylation sites of p-tau have been described [Hanger et al., 2009; Spires-Jones et al., 2009; Martin et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012] and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) have been developed for at least five of them. Studies examining different forms of p-tau in the early diagnosis of AD and in the differentiation from other causes of dementia have shown that as tau phosphorylated threonine 181 (p-tau 181) as well as the tau phosphorylation sites; p-tau 231–235, or p-tau 396–404, offer at least equivalent diagnostic utility for AD as compared with total-tau (t-tau) [Rosenbloom et al., 2010; van Harten et al., 2011].

CSF t-tau and p-tau 181 are elevated in AD compared to cognitively normal control subjects in a manner specific to neurodegenerative disease types [Arai et al., 1997; Price and Morris, 1999; Itoh et al., 2001; Lewczuk et al., 2004; Fagan et al., 2006]. Elevated CSF t-tau levels however do not appear to be specific to AD; they are also are seen in stroke [Hesse et al., 2001] and traumatic brain injury [Abdi et al., 2006]. Taken together these findings suggest that CSF t-tau and p-tau levels reflect different pathogenic processes in the brain; t-tau the degree of neuronal damage and p-tau the phosphorylation state of tau, and thus possibly the formation of NFTs.

Given that p-tau is the major component of NFTs found in AD brain and that CSF t-tau and p-tau levels are associated with AD, we hypothesized that genes involved in the phosphorylation (kinases) or de-phosphorylation (phosphatases) of tau may be associated with t-tau or p-tau levels in AD CSF differentially compared to cognitively normal controls. Eighteen SNPs, tagging putative regulatory regions and located within both the 5′ and 3′ regions of 5 kinase and 4 phosphatase genes, as well as SNPs within the MAPT gene, were chosen for this analysis. Two SNPs were found to be associated with CSF tau levels in AD.

METHODS

Subjects

For the tau phosphorylation gene analysis, subjects were 169 healthy cognitively normal controls and 101 AD patients (Table I). All procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of the participating institutions. A separate MAPT association analysis was performed to take into account MAPT H1 and H2 haplotypes. In the MAPT analysis, subjects were 149 healthy cognitively normal controls between 52–88 years old and 83 AD patients between 52–87 years old with an age-at-onset range of 46–82 years. After removing MAPT H2 positive subjects as defined by the SNP rs1800547, 90 healthy controls and 64 AD patients remained for analysis of MAPT SNP association with CSF t-tau and p-tau levels. Almost all subjects in the MAPT association analysis (88 of 90 controls and 63 of 64 AD patients) were also subjects in the tau phosphorylation gene analysis. Following informed consent, all subjects underwent extensive evaluation that consisted of medical history, family history, physical and neurologic examination, laboratory tests, and neuropsychological assessment; information was obtained from subjects and from informants for all patients.

TABLE I.

Sample Description

| Controls | AD | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 169 | 101 | |

| Mean age (range) | 68 (52–88) | 71 (52–87) | |

| Mean age-at-onset (range) | 66 (46–82) | ||

| Mean phosphorylated-tau (range) | 49.6 (15.0–140.0) | 88.7 (23.0–282.0) | <0.0001 |

| Mean total-tau (range) | 50.1 (9.0–168.0) | 110.9 (17.0–438.0) | <0.0001 |

| Mean Aβ42 (range) | 151.6 (73.0–240.0) | 105.7 (65.0–240.0) | <0.0001 |

| % Male | 39 | 54 | 0.0190 |

| % APOE ε4+ | 37 | 66 | <0.0001 |

| % Caucasian | 91 | 97 | 0.1000 |

All control subjects had normal cognition and underwent thorough clinical and neuropsychological assessment including: Logical memory (immediate and delayed), Category fluency for animals and Letter S, and Trail Making tests A and B, and all controls had Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) scores>26, and Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale scores of 0 [Peskind et al., 2006].

All AD patients were participants in research clinical cores at their respective institutions. Clinical diagnoses of AD were made according to well-established consensus criteria [McKhann et al., 1984; Petersen et al., 1999]. Most AD patients had a CDR score of 1, only a few had a CDR score of 2, and no AD patients had a CDR score of 3. No AD subjects had a known AD-causing mutation and none had a family history of AD that would suggest autosomal dominant AD.

Cerebrospinal Fluid

All CSF samples were collected in the morning after an overnight fast using the Sprotte 24-g traumatic spinal needle with the patient in either the lateral decubitus or sitting position [Peskind t al., 2005, 2006] Samples were aliquoted at the bedside and frozen immediately on dry ice and stored at −80°C until assayed. Total-tau and phosphorylated (181) tau were measured in the 9th ml of collected CSF using a sensitive multiplex xMAP Luminex platform (Luminex Corp, Austin, TX) with Innogenetics (INNO-BIA AlzBio3; Ghent, Belgium; for research use-only reagents) [Shaw et al., 2009]. CSF Aβ42 was also measured but was not further evaluated in this investigation (Table I). Intra-assay coefficient of variation was <10% for all assays.

Genes and SNP Selection

The tau phosphorylation gene analysis used SNPs from nine genes that were chosen for their biologically characterized role in tau phosphorylation. SNPs were also chosen according to the following criteria: (1) The SNP was located within a known or putative regulatory region of the gene. (2) The SNP had a minor allele frequency (MAF) of ≥0.1 in HapMap Caucasian (CEU) population and a minor genotype frequency in our study sample of ≥ 0.01. (3) The SNP genotyping assay was commercially available. (4) When necessary, tagging SNPs were chosen to capture putative regulatory regions. Based on these criteria, a total of 20 SNPs were selected (18 associated with tau phosphorylation genes and two within regulatory regions of the MAPT gene; see Table II). An additional SNP (rs429358) was also genotyped to determine APOE ε4 status.

TABLE II.

Genotype Frequency Description

| Gene name | Chromosome | SNP | Alleles | Location | NCBI (CEU), genotype frequency |

AD (n = 101), genotype frequency |

Control (n = 169), genotype frequency |

Chi-sq. unadjusted genotype P-value |

Chi-sq. adjusted genotypea P-value |

Adjusted collapsed genotypea P-value |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EE | EF | FF | EE | EF | FF | EE | EF | FF | ||||||||

| Protein kinases | ||||||||||||||||

| GSK3B | 3q13.33 | rs3755557 | T/a | 5′ Region | 0.02 | 0.33 | 0.65 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.82 | 0.01 | 0.25 | 0.74 | 0.247 | 0.037 | 0.041 |

| rs9826659 | A/g | Intron 11 | 0.13 | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.11 | 0.38 | 0.51 | 0.055 | 0.616 | 0.675 | ||

| CDK5 | 7q36.1 | rs1549759 | G/a | Intron 5 | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.73 | 0.05 | 0.27 | 0.68 | 0.02 | 0.30 | 0.69 | 0.312 | 0.173 | 0.419 |

| rs2069459 | T/g | Intron 9 | 0.15 | 0.47 | 0.38 | 0.20 | 0.33 | 0.48 | 0.17 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.310 | 0.899 | 0.374 | ||

| PRKCA | 17q24.2 | rs9910577 | C/t | Intron 2 | 0.20 | 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.25 | 0.47 | 0.29 | 0.23 | 0.46 | 0.31 | 0.890 | 0.668 | 0.658 |

| rs4791035 | G/c | 3′ Region | 0.27 | 0.40 | 0.33 | 0.22 | 0.50 | 0.29 | 0.23 | 0.49 | 0.28 | 0.967 | 0.691 | 0.479 | ||

| FYN | 6q21 | rs7768046 | A/g | Intron 1 | 0.16 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.44 | 0.32 | 0.17 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 0.261 | 0.512 | 0.981 |

| rs1621289 | T/c | Last intron | 0.07 | 0.46 | 0.48 | 0.18 | 0.46 | 0.37 | 0.09 | 0.49 | 0.42 | 0.092 | 0.238 | 0.558 | ||

| GAK | 4p16 | rs873785 | G/a | Intron 1 | 0.15 | 0.46 | 0.39 | 0.11 | 0.55 | 0.34 | 0.07 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.451 | 0.486 | 0.637 |

| rs6964 | C/t | 3′ Region | 0.07 | 0.51 | 0.41 | 0.08 | 0.38 | 0.54 | 0.09 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.471 | 0.303 | 0.289 | ||

| Protein phosphatases | ||||||||||||||||

| PPP3R1 | 2p15 | rs6546366 | C/a | 5′ Region | 0.23 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.10 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.08 | 0.48 | 0.44 | 0.825 | 0.910 | 0.776 |

| rs1868402 | C/t | Last intron | 0.06 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.07 | 0.39 | 0.54 | 0.06 | 0.42 | 0.52 | 0.839 | 0.996 | 0.864 | ||

| PTEN | 10q23.3 | rs1234224 | A/g | Intron 2 | 0.13 | 0.52 | 0.35 | 0.14 | 0.51 | 0.35 | 0.14 | 0.40 | 0.46 | 0.150 | 0.575 | 0.248 |

| rs478839 | A/g | 3′ Region | 0.15 | 0.44 | 0.41 | 0.13 | 0.37 | 0.50 | 0.17 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.469 | 0.538 | 0.417 | ||

|

PPP2R4 (PP2A) |

9q34 | rs10988217 | G/a | Intron 4 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.50 | 0.34 | 0.19 | 0.46 | 0.36 | 0.696 | 0.965 | 0.629 |

| rs913275 | A/g | 3′ Region | 0.05 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.09 | 0.45 | 0.47 | 0.12 | 0.40 | 0.49 | 0.630 | 0.912 | 0.524 | ||

| PIN1 | 19p13 | rs889162 | C/t | Intron 2 | 0.05 | 0.31 | 0.64 | 0.05 | 0.32 | 0.63 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.66 | 0.824 | 0.914 | 0.962 |

| rs2010457 | C/t | Intron 3 | 0.14 | 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.09 | 0.45 | 0.47 | 0.11 | 0.49 | 0.40 | 0.568 | 0.180 | 0.129 | ||

| Gene name | Chromosome | SNP | Alleles | Location |

NCBI (CEU), genotype frequency |

AD (n = 83), genotype frequency |

Control (n = 149), genotype frequency |

Chi-sq. unadjusted genotypeP-value |

Chi-sq. adjusted genotypea P-value |

Adjusted collapsed genotypea P-value |

||||||

| EE | EF | FF | EE | EF | FF | EE | EF | FF | ||||||||

| Tau (with H2) | 17q21.1 | rs1800547 | A/g | Intron 4 | 0.01 | 0.40 | 0.59 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.77 | 0.04 | 0.36 | 0.60 | 0.030 | 0.036 | 0.016 |

| MAPT | rs7521 | A/g | 3′ Region | 0.19 | 0.49 | 0.33 | 0.27 | 0.49 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.368 | 0.361 | 0.867 | |

| rs1467967 | G/a | Intron 1 | 0.09 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.19 | 0.35 | 0.46 | 0.13 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.352 | 0.729 | 0.674 | ||

| Gene name | Chromosome |

SNP alleles |

Location |

AD (n = 64), genotype frequency |

Control (n = 90), genotype frequency |

Unadjusted genotype P-value |

Adjusted genotypea P-value |

Adjusted collapsed genotypea P-value |

||||||||

| EE | EF | FF | EE | EF | FF | |||||||||||

| Tau (without H2) | 17q21.1 | rs7521 | A/g | 3′ Region | 0.20 | 0.45 | 0.34 | 0.20 | 0.47 | 0.33 | 0.986 | 0.718 | 0.638 | |||

| MAPT | rs1467967 | G/a | Intron 1 | 0.25 | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.22 | 0.46 | 0.32 | 0.483 | 0.796 | 0.356 | ||||

Adjusted for covariates: age, gender, race, and APOE ε4 status. P-values are not multiple comparison corrected.

SNP Genotyping

Genomic DNA was genotyped using TaqMan allelic discrimination detection on 384-well plates as previously described [Bekris et al., 2008]. Briefly, for each reaction, SNP TaqMan Assay (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA), TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and DNA were pipetted into each well. PCR was carried out using a 9700 Gene Amp PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Plates were then subjected to an end-point read on a 7900 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The results were first evaluated by cluster variations; the allele calls were then assigned automatically before being integrated into the genotype database.

Statistical Analysis

We compared SNP genotype frequencies (FF vs. EE vs. EF, where F denotes the major allele and E denotes the minor allele) between AD patients and control subjects using the chi-squared test. To adjust for age, gender, race, and APOE ε4 status (ε4 positive vs. negative), we performed logistic regression using disease status as the response variable, and SNP and these covariates as predictor variables. We also compared frequencies of collapsed genotype groups (absence or presence of the minor allele; i.e., FF vs. EE and EF) between AD patients and control subjects after adjusting for covariates (Table II). All subsequent analyses involving SNPs were based on the collapsed genotype group.

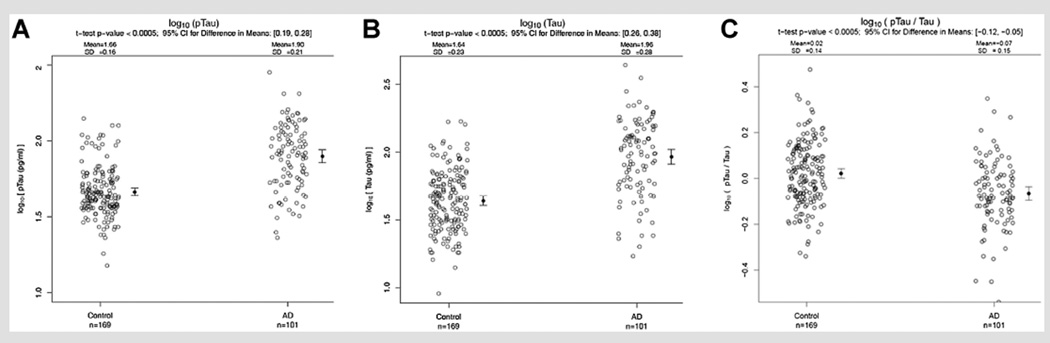

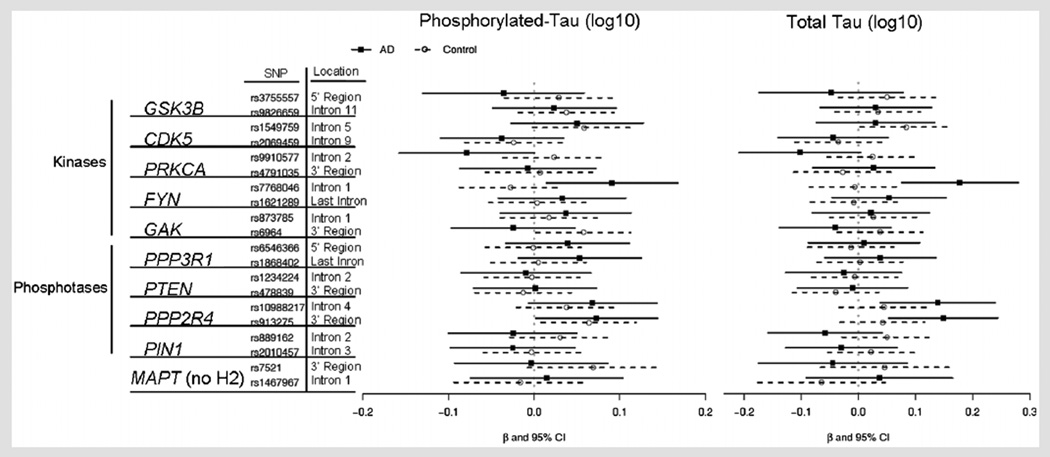

CSF t-tau and p-tau protein levels, as well as the ratio of these levels, were compared between AD patients and control subjects initially using t-tests (Fig. 1). We then examined the relationship between SNPs and CSF protein levels while taking into account gender, age, race, and APOE ε4 status using linear regression. Each of the initial linear regression models (one for each SNP) included the CSF protein level as the dependent variable and the predictor variables gender, age, race, APOE ε4 status, disease status, and SNP, as well as a disease status by SNP interaction term to allow the effect of SNP on disease (Fig. 2). For the t-tests and the linear regression models, CSF p-tau and t-tau protein levels and the p-tau/t-tau ratio were all log-transformed to induce homoscedasticity.

FIG. 1.

CSF tau levels in AD compared to Controls. CSF log 10 p-tau levels (Panel A). CSF log 10 t-tau levels (Panel B). CSF log 10 p-tau/t-tau levels (Panel C).

FIG. 2.

Beta coefficients for CSF phosphorylation tau and total tau levels in AD and controls for Tau phosphorylation pathway gene collapsed genotypes. The effect of a SNP for each disease group (AD or controls) was analyzed using linear regression, where CSF biomarker level was the outcome variable and the independent variables were age, gender, race, APOE ε4 status, disease status and SNP collapsed genotype (presence or absence of the minor allele; i.e., EF and EE vs. FF). A confidence interval which does not cross the vertical line at zero indicates that the difference in genotypes is significant (P<0.05) before adjustment for multiple comparisons for that group. A beta coefficient (solid square for AD, circle for controls) to the right of the vertical line represents higher CSF biomarker levels for the collapsed genotype group that contains minor alleles (EF, EE). Significant SNP P-values are shown in Table III.

In the case where significant SNP effects were found, we also investigated the model that included two-way interactions between the significant SNPs, as well as three-way interactions between the SNP pairs and disease status. We investigated the relationship between SNPs and age of onset in AD patients using linear regression models with age of onset as the response variable and SNP as a predictor variable, along with gender, age, race, and APOE ε4 status.

Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS (version 14) and R (version 2.12.2; R Development Core Team, 2009; http://www.R-project.org). When correcting for multiple comparisons the Holm [1979] method was used.

RESULTS

SNP Genotype Frequency

Eighteen SNPs from nine tau phosphorylation-related genes were genotyped (Table II). Comparison of the genotype frequency between AD and controls indicated that only rs3755557 in the GSK3B gene was significantly different (P = 0.041) when genotypes were collapsed into two groups, [the major genotype (FF) vs. the minor genotypes (EF, EE)], and after adjusting for age, gender, race, and APOE ε4 status. However, significance was lost after correcting for multiple comparisons.

CSF Tau Levels

CSF p-tau, t-tau, and p-tau/t-tau were compared between cognitively normal control subjects and AD patients. CSF p-tau and t-tau levels were significantly higher in AD patients compared to controls (P-value <0.0005; Fig. 1, Panels A and B). CSF p-tau relative to t-tau levels (p-tau/t-tau) were significantly lower in AD patients compared to controls (P-value <0.0005) (Fig. 1, Panel C). For p-tau, the mean (SD) for control subjects and AD patients was 1.66 (0.16) and 1.90 (0.21) log10(pg/ml), respectively, and the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for the difference was (0.19, 0.28) log10(pg/ml). For t-tau, the mean (SD) for control subjects and AD patients was 1.64 (0.23) and 1.96 (0.28) log10(pg/ml), respectively, and the 95% CI for the difference was (0.26, 0.38) log10(pg/ml). For the log10 (p-tau/t-tau) ratio, the mean (SD) for control subjects and AD patients was 0.02 (0.14) and −0.07 (0.15), respectively, and the 95% CI for the difference was (−0.12, −0.05).

SNP Genotype Effect on Tau Levels

Each SNP was tested individually for its effect on CSF tau levels in AD patients and controls. Figure 2 shows the effect of the SNP on p-tau or t-tau levels for each of the 18 tau phosphorylation-related SNPs and two SNPs within regulatory regions of the MAPT gene, based on the linear regression model described in the Methods Section. For each disease group, where disease group is defined as without disease (control subjects) or with disease (AD patients), the figures show either an increase or decrease in protein level (or ratio) for the collapsed minor allele carriers (EE, EF) compared to major genotype group (FF), along with 95% confidence intervals unadjusted for multiple comparisons. For example, CSF t-tau levels are significantly higher for minor allele carriers compared to major genotype carriers of rs7768046 in the FYN kinase gene within the AD group and remains significant after Holm correction for multiple comparisons (P = 0.0007, Holm corrected P = 0.01) while the difference between minor allele carriers and major genotype carriers is not significant within the control group (Fig. 2).

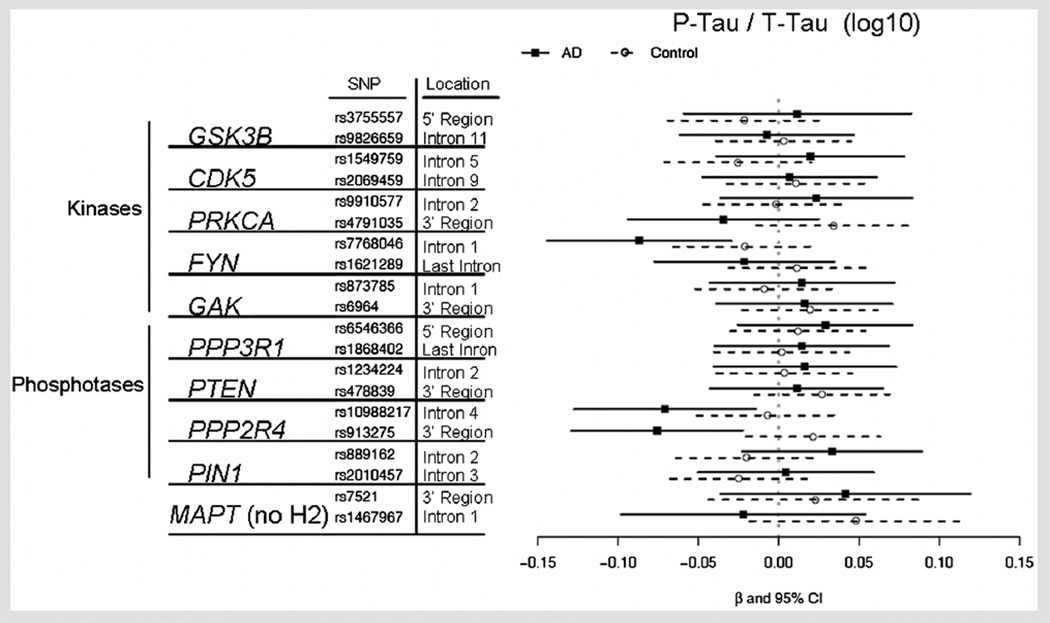

Figure 3 shows the effect of the SNP on p-tau relative to t-tau levels for each of the 18 tau phosphorylation-related SNPs, plus two SNPs within regulatory regions of the MAPT gene, based on the linear regression model described in the Methods Section.

FIG. 3.

Beta coefficients for CSF phosphorylation tau relative to total tau levels in AD and controls for tau phosphorylation pathway gene collapsed genotypes. The effect of a SNP for each disease group (AD or controls) was analyzed using linear regression, where CSF biomarker level was the outcome variable and the independent variables were age, gender, race, APOE ε4 status, disease status, SNP collapsed genotype (presence or absence of the minor allele; i.e., EF and EE vs. FF). A confidence interval which does not cross the vertical line at zero indicates that the difference in genotypes is significant (P<0.05) before adjustment for multiple comparisons for that group. A beta coefficient (solid square for AD, circle for controls) to the right of the vertical line represents higher CSF biomarker levels for the collapsed genotype group that contains minor alleles (EF, EE). Significant SNP P-values are shown in Table III.

Table III shows the SNP effects and P-values for all SNPs which showed nominally significant (as shown in Figs. 2 and 3; i.e., P ≤ 0.05 before correcting for multiple comparisons). SNP by disease status interaction effects, or nominally significant SNP effects within at least one of the disease status groups. After adjusting for multiple comparisons, the only effects that remained significant were the SNP effects within AD patients for rs913275 in the PPP2R4 phosphatase gene and rs7768046.

TABLE III.

SNP Effect on CSF Biomarker Levels

| Biomarker | Gene | SNP | SNP by disease status | SNP within AD | SNP within controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log10 (p-tau) | PRKCA | rs9910577 | 0.0441 (0.8387) | 0.0509 (0.9157) | 0.4438 (1.0000) |

| FYN | rs7768046 | 0.0163 (0.3263) | 0.0203 (0.4066) | 0.3648 (1.0000) | |

| PPP2R4 | rs913275 | 0.8410 (1.0000) | 0.0447 (0.8501) | 0.0243 (0.4860) | |

| GAK | rs6964 | 0.0797 (1.0000) | 0.5039 (1.0000) | 0.0421 (0.7995) | |

| Log10 (t-tau) | CDK5 | rs1549759 | 0.4188 (1.0000) | 0.5674 (1.0000) | 0.0428 (0.8556) |

| FYN | rs7768046 | 0.0050 (0.1020) | 0.0007 (0.0141)a | 0.8723 (1.0000) | |

| PPP2R4 | rs10988217 | 0.1435 (1.0000) | 0.0069 (0.1236) | 0.2640 (1.0000) | |

| PPP2R4 | rs913275 | 0.0832 (1.0000) | 0.0024 (0.0451)a | 0.2629 (1.0000) | |

| Log10 (p-tau/t-tau) | FYN | rs7768046 | 0.0741 (1.0000) | 0.0032 (0.0630) | 0.3536 (1.0000) |

| PPP2R4 | rs10988217 | 0.0781 (1.0000) | 0.0142 (0.2560) | 0.7615 (1.0000) | |

| PPP2R4 | rs913275 | 0.0050 (0.0997) | 0.0057 (0.1087) | 0.3115 (1.0000) |

P-values and Holm multiple comparison corrected P-values (shown in parentheses) are based on linear regression models that include gender, age, race, APOE ε4 status, disease status, and collapsed SNPs.

Significant after Holm (multiple comparisons taken into account).

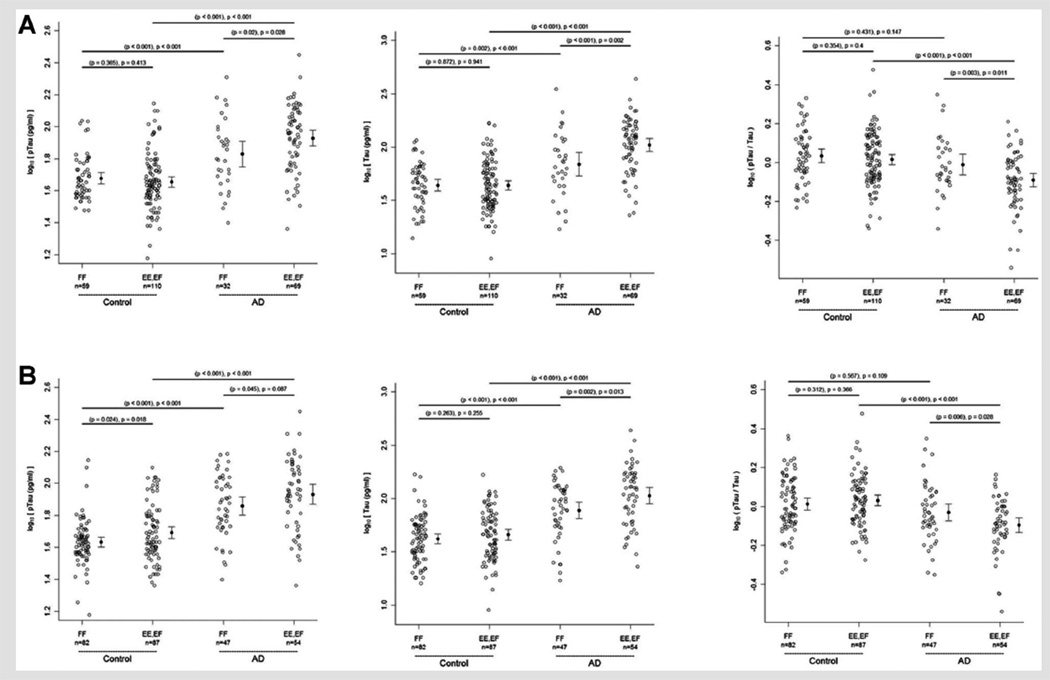

Effect of rs7768046 and rs913675 Genotype on CSF Tau Levels

One SNP in the FYN kinase gene (rs7768046) and one in the PPP2R4 phosphatase gene (rs913275) remained significant after Holm correction for multiple comparisons. The nature of this difference is summarized in Figure 4. For example, within the AD patient group the rs7768046 and rs913275 GG, AG collapsed genotype group (G allele carriers) have higher mean CSF p-tau and t-tau levels than the AA genotype, whereas this is not the case for control subjects. In addition, within the AD patient group the rs7768046 and rs913275 GG, AG collapsed genotype group have lower mean CSF p-tau/t-tau levels than the AA genotype and the difference between AD and controls is restricted to the GG, AG collapsed genotype group (Fig. 4). The differences between genotype and disease groups were analyzed with or without adjusting for gender, race, age, and APOE ε4 status. Unadjusted P-values are based on the two-sample t-test and adjusted P-values (in parentheses) are based on the linear model described in the Methods Section (Fig. 4), but not corrected for multiple comparisons.

FIG. 4.

CSF tau levels in controls and AD patients stratified by collapsed genotype for SNPs rs 7768046 (FF = AA; EE, EF = GG, AG) (Panel A) and rs913675 (FF = AA; EE, EF = GG, AG) (Panel B). Unadjusted P-values are based on the two-sample t-test while adjusted P-values take into account gender, race, age, and APOE ε4 status (parentheses) are based on a linear model.

Interaction Between rs7768046 and rs913275

To assess the possible combined influence of rs7768046 and rs913275 on CSF tau levels, we utilized a linear regression model that consisted of the initial model with the addition of two-way interactions between rs7768046 and rs913275 as well as three-way interactions between the SNP pairs and disease status. None of these two-way or three-way interactions were statistically significant (data not shown).

SNP Effect on AD Age-at-Onset

Each SNP was tested individually for its effect on AD age-at-onset. Only one SNP (rs873785 in the GAK kinase gene) showed nominal significance (P = 0.049), but significance was lost after correcting for multiple comparisons (Holm corrected P = 1; data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The abnormal phosphorylation of tau is a characteristic hallmark of AD and NFTs. The aim of this investigation was to determine if genetic variation within or near genes that encode kinases or phosphatases, with reported involvement in the phosphorylation status of tau, correlate with CSF t-tau or p-tau levels. This is a novel investigation because it involves the analysis of several tau phosphorylation-related genes in parallel using the same subjects, thus eliminating the variability and uncertainty associated with across study comparisons of individual genes. In addition, the hypothesis of this investigation focuses on a specific biological pathway implicated in the pathogenesis of AD which eliminates the large scale analysis of SNPs required in GWAS, further decreasing uncertainty.

The main finding of this investigation is that, after corrections for multiple comparisons, two SNPs, one within a kinase gene (FYN: rs7768046) and the other within a phosphatase gene (PPP2R4: rs913275), significantly correlate with CSF tau levels. These results suggest that genetic variation within genes that encode proteins implicated in the maintenance of tau phosphorylation influence tau levels measured in CSF.

Minor allele carriers for rs7768046 and rs913275 (i.e., G allele carriers: AG, GG collapsed genotype) were found to have higher t-tau and p-tau levels compared to the AA genotype within AD subjects but not within cognitively normal controls (with and without adjusting for gender, age, race, and APOE ε4 status). These differences remain significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons for t-tau but not p-tau. This difference in tau levels is further reflected in significantly lower ratios of p-tau/t-tau levels for rs7768046 and rs913275 G allele carriers compared to the AA genotype within AD subjects but not within cognitively normal subjects. Taken together, these results suggest a difference in CSF phosphorylated tau production between AD and cognitively normal controls that are related to the G allele of rs7768046 and the G allele of rs913275.

The genetic association found between FYN (rs7768046) and CSF tau levels are supported by a previous report by Cruchaga et al. [2010] that describes an association between rs7768046 and CSF p-tau levels in their initial series. Genetic associations between FYN SNPs and alcohol dependence [Schumann et al., 2003; Pastor et al., 2009], schizophrenia cognitive performance [Rybakowski et al., 2007] and allergic asthma [Szczepankiewicz et al., 2008] have been reported, but were not found for AD in a Japanese population [Watanabe et al., 2004].

A genetic association between CSF tau levels and rs1868402 in PPP3R1, another kinase gene investigated here, was reported in by Cruchaga et al. [2010], but was not found in our study. Interestingly, there was partial overlap between the Cruchaga et al. study sample and our study sample suggesting that variability in study sample contributes to the ability to detect a genetic association with CSF tau levels in AD and emphasizes the need to approach genetic biomarker association study results with caution.

FYN is a tyrosine kinase that has been implicated in the phosphorylation of tau and AD pathology [Ittner and Gotz, 2011; Yang et al., 2011]. FYN has been reported to be elevated in AD [Shirazi and Wood, 1993; Ho et al., 2005] and appears to affect AD pathology and cognition in animal models [Chin et al., 2004, 2005; Roberson et al., 2011]. Rs7768046 is located within intron 1 of the FYN kinase gene. Since rs7768046 is located near the core promoter region as well as within a dense ENCODE predicted H3K4Me1 histone mark promoter-enhancer region it may be speculated that trans-acting factors or other modifying factors specific to the microenvironment of the AD brain modulate FYN expression [Rosenbloom et al., 2010].

Rs913675 is located within the 3′ region of the PPP2R4 gene. The PPP2R4 gene encodes protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), a major tau phosphatase in the human brain that has been implicated in the hyperphosphorylation of tau in AD [Liu et al., 2005; Iqbal et al., 2009; Qian et al., 2010]. The association between PPP2R4 genetic variation and CSF tau levels is novel and to our knowledge has not been reported previously. Since rs913275 is located within a putative regulatory region for the gene, as well as within a dense ENCODE predicted H3K4Me1 histone mark promoter-enhancer region it may be speculated that trans-acting factors or other modifying factors specific to the microenvironment of the AD brain modulate its expression [Rosenbloom et al., 2010].

Interestingly, the FYN and PPP2R4 SNP effect within the AD patient group, but not the control subjects, suggests that both FYN and PPP2R4 may be influenced by modifying factors specific to the pathology of the AD brain that modulate G allele expression differentially compared to A alleles.

An advantage of this investigation, in contrast to GWAS, is that a small number of SNPs (n = 20), within the context of a specific hypothesis, were tested and restricted to a specific biological relationship between genetic variation and production of the phosphorylated tau in CSF. A limitation of this investigation’s approach is that only a few SNPs were used to capture putative regulatory genetic variations within and surrounding the kinase and phosphatase genes of interest. The tau phosphorylation status is regulated by many known and unknown kinase and phosphatase proteins that were not taken into account in this investigation. Thus, these results must be approached with caution since many important genes and SNPs may have been missed.

In addition, a positive SNP may represent a surrogate marker for a true functional SNP that was not analyzed in this study. Thus, the FYN and PPP2R4 SNPs found to have effects in this study, may be surrogate markers in linkage disequilibrium with functional SNPs that affect gene structure and thus protein function instead of modulation of expression levels. To elucidate a functional influence of genetic variation within the FYN and PPP2R4 regulatory regions, functional studies that fine map the specific contribution of the genetic variations, both within and surrounding these genes, on expression levels are required. In addition, these findings need to be further replicated because they were found to be only marginally significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons.

A disadvantage of this investigation is that only p-tau phosphorylation site threonine 181 was measured. Multiple previously described tau phosphorylation sites were not measured [Sato-Harada et al., 1996; Lebouvier et al., 2009; Martin et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012]. For example, FYN has been reported to phosphorylate tyrosine 18, not threonine 181 [Lebouvier et al., 2009]. Therefore, assessment of p-tau tyrosine 18 may be of greater interest in relation to a genetic association between CSF p-tau and FYN genetic variation. Furthermore, it may be speculated that the lack of significant association between FYN SNPs and CSF p-tau may be related to the phosphorylation site, but does not explain the association between the FYN SNP and CSF t-tau levels. The correlation between FYN and PPP2R4 SNPs and CSF t-tau levels in AD may implicate that the activity by these genes does not impact tau phosphorylation but instead may influence CSF total tau levels. Previous reports suggest that multiple proteins are influenced by FYN and PPP2R4 [Qian et al., 2010; Usardi et al., 2011]. For example, it has been reported that tyrosine phosphorylation of tau by FYN may alter the cellular localization of tau [Usardi et al., 2011]. In addition, indirect effects on phosphatase activity by PPP2R4 on t-tau levels have been reported to occur via activation of GSK-3beta [Qian et al., 2010].

In summary, in this exploratory investigation, CSF total-tau levels in AD were found to correlate with SNPs tagging putative regulatory regions within FYN and PPP2R4. These results suggest that the proteins encoded by these genes influence AD CSF tau levels. Characterization of the functional influence of FYN and PPP2R4 genetic variation on expression levels of these genes, as well as their impact on tau levels, may lead to a better understanding of AD pathogenesis, help find novel AD-specific biomarkers, and identify AD therapeutic targets.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported in part by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development Clinical Research and Development Program, the Biomedical Laboratory Research Program and NIH Grants 2P50AG005136-27, 1P50NS062684-01A1, and K99AG034214-02. Additional support includes University of Washington Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center NIH P50-AB005136, University of California San Diego Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center AGO 5131.

REFERENCES

- Abdi F, Quinn JF, Jankovic J, McIntosh M, Leverenz JB, Peskind E, Nixon R, Nutt J, Chung K, Zabetian C, Samii A, Lin M, Hattan S, Pan C, Wang Y, Jin J, Zhu D, Li GJ, Liu Y, Waichunas D, Montine TJ, Zhang J. Detection of biomarkers with a multiplex quantitative proteomic platform in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with neurodegenerative disorders. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9(3):293–348. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai H, Morikawa Y, Higuchi M, Matsui T, Clark CM, Miura M, Machida N, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Sasaki H. Cerebrospinal fluid tau levels in neurodegenerative diseases with distinct tau-related pathology. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;236(2):262–264. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekris LM, Millard SP, Galloway NM, Vuletic S, Albers JJ, Li G, Galasko DR, DeCarli C, Farlow MR, Clark CM, Quinn JF, Kaye JA, Schellenberg GD, Tsuang D, Peskind ER, Yu CE. Multiple SNPs within and surrounding the apolipoprotein E gene influence cerebrospinal fluid apolipoprotein E protein levels. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;13(3):255–266. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-13303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82(4):239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin J, Palop JJ, Puolivali J, Massaro C, Bien-Ly N, Gerstein H, Scearce-Levie K, Masliah E, Mucke L. Fyn kinase induces synaptic and cognitive impairments in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2005;25(42):9694–9703. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2980-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin J, Palop JJ, Yu GQ, Kojima N, Masliah E, Mucke L. Fyn kinase modulates synaptotoxicity, but not aberrant sprouting, in human amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2004;24(19):4692–4697. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0277-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruchaga C, Kauwe JS, Mayo K, Spiegel N, Bertelsen S, Nowotny P, Shah AR, Abraham R, Hollingworth P, Harold D, Owen MM, Williams J, Lovestone S, Peskind ER, Li G, Leverenz JB, Galasko D, Morris JC, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM, Goate AM. SNPs associated with cerebrospinal fluid phospho-tau levels influence rate of decline in Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(9):pii, e1001101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Mach RH, Lee SY, Dence CS, Shah AR, LaRossa GN, Spinner ML, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, DeKosky ST, Morris JC, Holtzman DM. Inverse relation between in vivo amyloid imaging load and cerebrospinal fluid Abeta42 in humans. Ann Neurol. 2006;59(3):512–519. doi: 10.1002/ana.20730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanger DP, Anderton BH, Noble W. Tau phosphorylation: The therapeutic challenge for neurodegenerative disease. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15(3):112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse C, Rosengren L, Andreasen N, Davidsson P, Vanderstichele H, Vanmechelen E, Blennow K. Transient increase in total tau but not phospho-tau in human cerebrospinal fluid after acute stroke. Neurosci Lett. 2001;297(3):187–190. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho GJ, Hashimoto M, Adame A, Izu M, Alford MF, Thal LJ, Hansen LA, Masliah E. Altered p59Fyn kinase expression accompanies disease progression in Alzheimer’s disease: Implications for its functional role. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26(5):625–635. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm S. Asimple sequential rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal K, Liu F, Gong CX, Alonso Adel C, Grundke-Iqbal I. Mechanisms of tau-induced neurodegeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118(1):53–69. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0486-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh N, Arai H, Urakami K, Ishiguro K, Ohno H, Hampel H, Buerger K, Wiltfang J, Otto M, Kretzschmar H, Moeller HJ, Imagawa M, Kohno H, Nakashima K, Kuzuhara S, Sasaki H, Imahori K. Large-scale, multicenter study of cerebrospinal fluid tau protein phosphorylated at serine 199 for the antemortem diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2001;50(2):150–156. doi: 10.1002/ana.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ittner LM, Gotz J. Amyloid-beta and tau—A toxic pas de deux in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12(2):65–72. doi: 10.1038/nrn2967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebouvier T, Scales TM, Williamson R, Noble W, Duyckaerts C, Hanger DP, Reynolds CH, Anderton BH, Derkinderen P. The microtubule-associated protein tau is also phosphorylated on tyrosine. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;18(1):1–9. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewczuk P, Esselmann H, Bibl M, Beck G, Maler JM, Otto M, Kornhuber J, Wiltfang J. Tau protein phosphorylated at threonine 181 in CSF as a neurochemical biomarker in Alzheimer’s disease: Original data and review of the literature. J Mol Neurosci. 2004;23(1–2):115–122. doi: 10.1385/JMN:23:1-2:115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Gong CX. Contributions of protein phosphatases PP1, PP2A, PP2B and PP5 to the regulation of tau phosphorylation. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22(8):1942–1950. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin L, Latypova X, Terro F. Post-translational modifications of tau protein: Implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Int. 2011;58(4):458–471. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor IJ, Laso FJ, Ines S, Marcos M, Gonzalez-Sarmiento R. Genetic association between −93A/G polymorphism in the Fyn kinase gene and alcohol dependence in Spanish men. Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24(3):191–194. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peskind ER, Li G, Shofer J, Quinn JF, Kaye JA, Clark CM, Farlow MR, DeCarli C, Raskind MA, Schellenberg GD, Lee VM, Galasko DR. Age and apolipoprotein E*4 allele effects on cerebrospinal fluid beta-amyloid 42 in adults with normal cognition. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(7):936–939. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.7.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peskind ER, Riekse R, Quinn JF, Kaye J, Clark CM, Farlow MR, Decarli C, Chabal C, Vavrek D, Raskind MA, Galasko D. Safety and acceptability of the research lumbar puncture. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2005;19(4):220–225. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000194014.43575.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: Clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56(3):303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price JL, Morris JC. Tangles and plaques in nondemented aging and “preclinical” Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;45(3):358–368. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199903)45:3<358::aid-ana12>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian W, Shi J, Yin X, Iqbal K, Grundke-Iqbal I, Gong CX, Liu F. PP2A regulates tau phosphorylation directly and also indirectly via activating GSK-3beta. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19(4):1221–1229. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson ED, Halabisky B, Yoo JW, Yao J, Chin J, Yan F, Wu T, Hamto P, Devidze N, Yu GQ, Palop JJ, Noebels JL, Mucke L. Amyloid-beta/Fyn-induced synaptic, network, and cognitive impairments depend on tau levels in multiple mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2011;31(2):700–711. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4152-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom KR, Dreszer TR, Pheasant M, Barber GP, Meyer LR, Pohl A, Raney BJ, Wang T, Hinrichs AS, Zweig AS, Fujita PA, Learned K, Rhead B, Smith KE, Kuhn RM, Karolchik D, Haussler D, Kent WJ. ENCODE whole-genome data in the UCSC Genome Browser. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Databaseissue):D620–D625. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybakowski JK, Borkowska A, Skibinska M, Hauser J. Polymorphisms of the Fyn kinase gene and a performance on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Genet. 2007;17(3):201–204. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e3280991219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato-Harada R, Okabe S, Umeyama T, Kanai Y, Hirokawa N. Microtubule-associated proteins regulate microtubule function as the track for intracellular membrane organelle transports. Cell Struct Funct. 1996;21(5):283–295. doi: 10.1247/csf.21.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann G, Rujescu D, Kissling C, Soyka M, Dahmen N, Preuss UW, Wieman S, Depner M, Wellek S, Lascorz J, Bondy B, Giegling I, Anghelescu I, Cowen MS, Poustka A, Spanagel R, Mann K, Henn FA, Szegedi A. Analysis of genetic variations of protein tyrosine kinase fyn and their association with alcohol dependence in two independent cohorts. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(12):1422–1426. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00635-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw LM, Vanderstichele H, Knapik-Czajka M, Clark CM, Aisen PS, Petersen RC, Blennow K, Soares H, Simon A, Lewczuk P, Dean R, Siemers E, Potter W, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker signature in Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative subjects. Ann Neurol. 2009;65(4):403–413. doi: 10.1002/ana.21610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi SK, Wood JG. The protein tyrosine kinase, fyn, in Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Neuroreport. 1993;4(4):435–437. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199304000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spires-Jones TL, Stoothoff WH, de Calignon A, Jones PB, Hyman BT. Tau pathophysiology in neurodegeneration: A tangled issue. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32(3):150–159. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczepankiewicz A, Breborowicz A, Skibinska M, Wilkosc M, Tomaszewska M, Hauser J. Association analysis of tyrosine kinase FYN gene polymorphisms in asthmatic children. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2008;145(1):43–47. doi: 10.1159/000107465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usardi A, Pooler AM, Seereeram A, Reynolds CH, Derkinderen P, Anderton B, Hanger DP, Noble W, Williamson R. Tyrosine phosphorylation of tau regulates its interactions with Fyn SH2 domains, but not SH3 domains, altering the cellular localization of tau. FEBS J. 2011;278(16):2927–2937. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Harten AC, Kester MI, Visser PJ, Blankenstein MA, Pijnenburg YA, van der Flier WM, Scheltens P. Tau and p-tau as CSF biomarkers in dementia: A meta-analysis. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2011;49(3):353–366. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2011.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JZ, Xia YY, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Abnormal hyperphosphorylation of tau: Sites, regulation, and molecular mechanism of neurofibrillary degeneration. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012 doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-129031. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Ohnuma T, Shibata N, Ohtsuka M, Ueki A, Nagao M, Arai H. No genetic association between Fyn kinase gene polymorphisms (−93A/G, IVS10+37T/C and Ex12+894T/G) and Japanese sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2004;360(1–2):109–111. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K, Belrose J, Trepanier CH, Lei G, Jackson MF, MacDonald JF. Fyn, a potential target for Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;27(2):243–252. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]