Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Despite recent media attention and potential public health importance, little is known about the prevalence and nature of sexting. Using a large school-based sample of adolescents, we examined the prevalence of sexting behaviors, as well as its relation to dating, sex, and risky sexual behaviors.

DESIGN

Data are from Time 2 of a three-year longitudinal study. Participants self-reported their history of dating, sexual behaviors, and sexting (sent, asked, been asked, bothered by being asked).

SETTING

Seven public high schools in southeast Texas.

PARTICIPANTS

A total of 948 public high school students (55.9% female) participated. The sample consisted of African American (26.6%), Caucasian (30.3%), Hispanic (31.7%), Asian (3.4%), and mixed/other (8.0%) teens.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Having ever engaged in sexting behaviors.

RESULTS

28% of the sample reported having sent a naked picture of themselves through text or email (sext), and 31% reported having asked someone for a sext. Over half (57%) had been asked to send a sext, with a vast majority bothered by having been asked. Adolescents who engaged in sexting behaviors were more likely to have begun dating and to have had sex than those who did not sext (all p<.001). For girls, sexting was also associated with risky sexual behaviors.

CONCLUSIONS

The results suggest that teen sexting is prevalent, and potentially indicative of teens’ sexual behaviors. Teen-focused health care providers should consider screening for sexting behaviors, so as to provide age-specific education about the potential consequences of sexting, and as a mechanism for discussing sexual behaviors.

Keywords: Teen sexting, adolescents, gender, dating, risky sexual behavior

Sexting (a combination of the words sex and texting), or the practice of electronically sending sexually explicit images or messages from one teen to another, has received an abundance of attention in the popular press.1–4 Much of this attention has been limited to 1) legal cases in which teens who create, send, receive, store, and/or disseminate nude pictures of themselves or another teen face criminal charges including child pornography,2,5–10 and 2) cases where teens are harassed and bullied as a result of the nude picture being distributed beyond the intended audience.2,11–12 Although media reports often cite various examples of sexting leading to bullying, and even suicide,11 we understand very little about the public health importance of sexting.

Considering the media attention and potential public health implications, it is surprising that research on this topic has been slow to develop. Data on teen sexting, including prevalence rates ranging from 1% to 31%, are primarily based on online polls or media-generated studies.3,13–16 For example, a frequently cited online survey conducted by the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy and Cosmogirl.com15 found that 20% of teens between the ages of 13 and 19 have sexted a nude or semi-nude picture of themselves to another teen. Conversely, a study by the Pew Research Center found that only 4% of 12–17 year olds have sent a sext, but that 15% reported receiving one.17 While these non-peer reviewed studies have brought needed attention to sexting, they suffer from methodological limitations including biased samples and unknown or extremely low response rates. In one of the few peer-reviewed studies to consider teen sexting, Dowdell and colleagues18 reported that 15% of their high-school sample had been sent a sext, and a third reported knowing someone who had been involved in sexting.

A recent national study of 10 to 17 year olds found a surprisingly low rate of teen sexting behaviors.19 In fact, when sexting was defined as sharing of naked images, they found that only 1.3% of youth appeared in or created a sext and only 5.9% received a sext. While this study addressed several limitations of previous work, the random-digit-dialing approach (relying mostly on households with landlines) likely resulted in an underestimate of actual sexting behaviors. Research has shown that households with landlines tend to be less ethnically diverse, have higher SES, and be more conservative compared to households relying solely on cell phone service.20 Indeed, youth in the Mitchell et al19 study were 73% White, 78% lived in a two-parent household, and 30% lived in households with an annual income of ≥$100,000. This sampling bias may explain the low prevalence of sexting relative to other studies and online polls.

With scant and equivocal empirical data, pediatricians, policy-makers, schools and parents are handicapped by insufficient information about the nature and importance of teen sexting. In addition to the aforementioned legal ramifications and potential for bullying, sexting may be a risk factor for or an indicator of risky sexual behavior. Given the lack of previous studies, it is unclear how this new behavior fits within the domain of teen dating and sexual behaviors. Thus, the purpose of this study is two-fold. First, we identify the prevalence and describe the nature of sexting (as sender and receiver) among a large ethnically diverse school-based sample of adolescents. Second, we examine the association between sexting and sexual behaviors. While the novelty of this topic prevents us from making specific empirically-guided hypotheses, we anticipate that sexting behaviors will differ by gender, be an extension of teens’ lives, and will co-occur with their intimate (dating) and sexual (intercourse, risky sex) behaviors.

METHODS

Sample and Study Design

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of UTMB. Current data are from Time 2 of Dating it Safe, an ongoing longitudinal study of teen dating violence and other high-risk adolescent behaviors. Participants at Time 1 (Spring 2010) included 1042 students recruited from seven public high schools in four Houston-area school districts. 964 participants (93%) were retained for Time 2. Study recruitment occurred during school hours in courses with mandated attendance, and both parental permission and student assent were obtained. Assessments at each time point occurred during school hours, and students received a $10 gift card for participating. Participants no longer at their original school were surveyed at an alternate time and location.

For the current study, only Time 2 data were analyzed because the sexting items did not appear in the Time 1 survey. Only participants who answered at least one sexting item were included in the analysis (N=948).

Measures

Sexting

We assessed lifetime prevalence of sexting with four items developed for this study, including 1) Have you ever sent naked pictures of yourself to another through text or email; 2) Have you ever asked someone to send naked pictures of them to you; 3) Have you ever been asked to send naked pictures of yourself through text or email; and, 4) If so, how much were you bothered by this (Not at all, A little, A lot, A great deal). Questions were developed based on a review of relevant literature3,17 and in consultation with adolescent health experts. For some analyses, the question regarding whether teens were bothered by being asked for a sext was collapsed into two categories: 1) “not at all” and 2) “a little”, “a lot”, or “a great deal”. Given the increased potential for legal and psychosocial consequences, our definition of sexting was limited to sending naked pictures, as opposed to semi-nude pictures or explicit messages.

Dating and sexual behaviors

Participants were asked whether they “have begun dating, going out with someone, or had a boyfriend/girlfriend”, and if they have ever had sexual intercourse. Participants with a history of sexual intercourse were asked about their number of sexual partners in the past year, and how often they use alcohol or drugs before sexual intercourse. The last variable was collapsed into two categories: 1) “never” and 2) “rarely, “sometimes”, or “always”.

Demographic variables included gender, age, race/ethnicity, and parents’ education. Parents’ education was the highest level completed for either parent (high school or less; some college or more).

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS© 19.0 and SAS 9.2. Relationships between variables were examined using χ2, with alpha set at <.05.

RESULTS

Participants ranged in age from 14 to 19 (Mean=15.8), and were in either the 10th or 11th grade. Of the participants, 55.9% were female, and the race/ethnicity of the analyzed sample was 26.6% African American, 30.3% Caucasian, and 31.7% Hispanic.

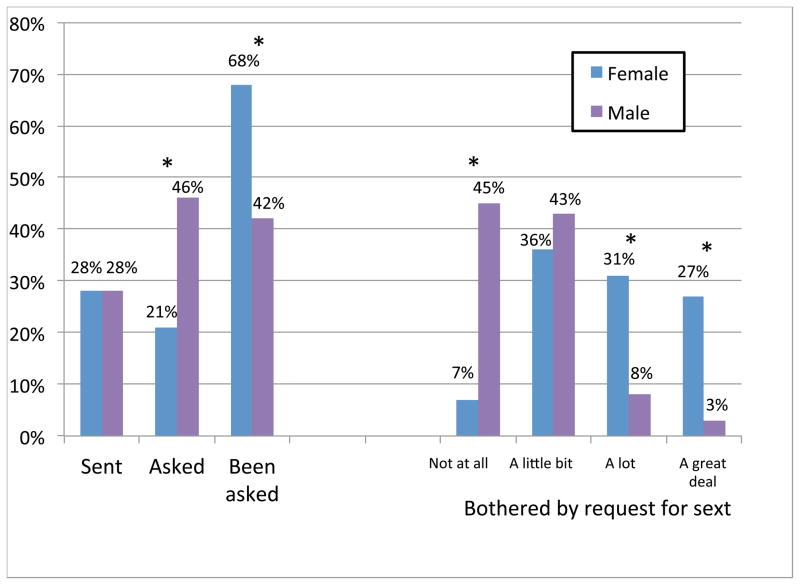

A sizeable minority of teens (n=259; 27.6%) reported having sent a naked picture of themselves through text or email (sext). There was no significant difference between boys (27.8%) and girls (27.5%) in the proportion of teens who reported having sent a sext (Figure 1). However, girls (68.4%) more often reported having been asked to send a sext, compared to boys (42.1%, p<.001). Boys were significantly (p<.001) more likely than girls to report having asked someone for a sext (46% and 21%, respectively). As demonstrated in Figure 1, of those who had been asked to send a sext, girls more often reported being bothered by the request. For example, whereas 27% of girls reported being bother a great deal, only 3% of boys endorsed this option (p<.001).

Figure 1.

Gender differences in sexting behaviors

As shown in Table 1, the proportion of teens who had been asked to send a sext and who had actually sent a sext differed by race/ethnicity, with White/non Hispanic and African American teens more likely than the other racial/ethnic groups to have both been asked and to have sent a sext.

Table 1.

Sexting behaviors by race/ethnicity, age, and parental education level.

| Demographics | Sent a sext | Asked for a sext | Been asked to sext | Bothered by being asked | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 21.5% | 63 | 29.4% | 86 | 49.8% | 151 | 83.3% | 125 |

| White/non hispanic | 34.5% | 99 | 33.7% | 97 | 61.0% | 177 | 76.8% | 136 |

| African American | 27.1% | 68 | 31.9% | 80 | 65.0% | 160 | 82.4% | 131 |

| Asian | 18.8% | 6 | 15.6% | 5 | 24.2% | 8 | 62.5% | 5 |

| Mixed/other | 31.1% | 23 | 36.5% | 27 | 57.9% | 44 | 88.6% | 39 |

| p=0.007 | p=0.21 | p<.0001 | p=.19 | |||||

| Age | ||||||||

| 15 or younger | 19.9% | 44 | 26.7% | 59 | 44.4% | 99 | 86.9% | 86 |

| 16 | 27.9% | 132 | 30.8% | 146 | 61.5% | 294 | 82.9% | 242 |

| 17 | 32.6% | 69 | 36.8% | 78 | 60.4% | 131 | 73.3% | 96 |

| 18 or older | 45.2% | 14 | 38.7% | 12 | 53.3% | 16 | 75.0% | 12 |

| p=.003 | p=.11 | p=.0002 | p=.04 | |||||

| Parent Education | ||||||||

| High school or less | 30.0% | 86 | 38.2% | 110 | 54.8% | 161 | 76.9% | 123 |

| Some college or more | 27.5% | 156 | 28.6% | 162 | 58.8% | 333 | 82.2% | 273 |

| p=.45 | p=.004 | p=.25 | p=.16 | |||||

There were also differences across age in the proportion of teens who were asked to send a sext (p=.0002), who sent a sext (p=.003), and who were bothered (at least a little) by being asked to send a sext (p=.04). Older teens were more likely to have sent a sext, and were less likely to have been bothered by being asked to send a sext. The proportion of teens who reported having been asked to send a sext appeared to peak at 16 and 17 years of age (61.5% and 60.4%, respectively), then declined in those aged 18 and older (53.3%).

Parental education level was significantly associated only with teens’ reports of having asked for a sext; adolescents with parents who had a high school education or less were more likely to have asked for a sext (p=.004).

Dating, sex, and sexting

Of the current sample, 93% of girls and 90% of boys have started dating, with 51.1% of girls and 54.6% of boys reporting a history of sexual intercourse. Of those reporting a history of sexual intercourse, boys (52%) were slightly more likely than girls (43%) to report having sex with more than one partner in the previous year (p=.05). With respect to using substances before sex, no differences emerged between boys and girls (37% and 32%, respectively).

Among girls, there was a significant association between all sexting behaviors and all dating, sex, and risky sex behaviors (Table 2). The prevalence of having started dating, having had sex, having multiple sex partners, and using alcohol or other drugs before sex were all higher among those who have sent, received, or asked for a sext than among those who had not engaged in those sexting behaviors. For example, among girls who had not sent a sext, 42.0% reported having sex, whereas among those who had sent a sext, 77.4% reported having sex (p<.0001). In addition, nearly all of the girls who were not at all bothered by having been asked to send a sext also reported that they have had sex (95.7%), whereas a smaller percentage of those who were bothered to some degree reported that they have had sex (44.9%–71.4%; p<.0001).

Table 2.

Association between dating, risky sexual behaviors and sexting behaviors among girls.

| Risky sex behaviors | Ever dated | Ever had sex | > 1 partner in last year | AOD sex | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | |

| Sent a sext | ||||||||

| Yes | 100.0% | 145 | 77.4% | 113 | 55.8% | 63 | 39.8% | 45 |

| No | 89.8% | 334 | 42.0% | 162 | 34.6% | 56 | 26.5% | 43 |

| p<.0001 | p<.0001 | p<.0005 | p<.02 | |||||

| Asked for a sext | ||||||||

| Yes | 100.0% | 107 | 80.6% | 87 | 56.3% | 49 | 41.4% | 36 |

| No | 90.7% | 372 | 44.3% | 188 | 37.2% | 70 | 27.7% | 52 |

| p<.0002 | p<.0001 | p<.003 | p<.02 | |||||

| Been asked to sext | ||||||||

| Yes | 98.3% | 354 | 63.6% | 232 | 49.1% | 114 | 36.2% | 84 |

| No | 79.8% | 126 | 23.7% | 40 | 7.5% | 3 | 10.0% | 4 |

| p<.0001 | p<.0001 | p<.0001 | p=.0008 | |||||

| Bothered by being asked | ||||||||

| Not at all | 100.0% | 24 | 95.7% | 22 | 50.0% | 11 | 27.3% | 6 |

| A little | 100.0% | 130 | 65.2% | 86 | 53.5% | 46 | 43.0% | 37 |

| A lot | 98.2% | 109 | 71.4% | 80 | 51.3% | 41 | 35.0% | 28 |

| A great deal | 95.8% | 91 | 44.9% | 44 | 36.4% | 16 | 29.6% | 13 |

| p=.08 | p<.0001 | p=.30 | p=.34 | |||||

AOD sex = Reports using alcohol or drugs before having sex in the past year

For boys, having sent a sext and having asked for a sext were each associated with dating and having had sex (Table 3). For example, 81.8% of boys who sent a sext reported that they have had sex before, whereas only 45.4% of boys who had never sent a sext reported that they have had sex (p<.0001). However, there was no significant association between having sent or received a sext and having multiple sex partners or using alcohol or other drugs before sex. There were significant associations between having been asked to send a sext and all dating and sexual behaviors. For instance, of those who reported that someone had asked them to send a sext, 76.2% have had sex, whereas of those who reported not having been asked to sext, only 38.2% have had sex before (p<.0001).

Table 3.

Association between dating, risky sexual behaviors and sexting behaviors among boys.

| Risky sex behaviors | Ever dated | Ever had sex | > 1 partner in last year | AOD sex | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | |

| Sent a sext | ||||||||

| Yes | 100.0% | 110 | 81.8% | 90 | 51.7% | 46 | 37.5% | 33 |

| No | 86.0% | 239 | 45.4% | 132 | 53.4% | 70 | 36.9% | 48 |

| p<.0001 | p<.0001 | p=.80 | p=.93 | |||||

| Asked for a sext | ||||||||

| Yes | 98.9% | 181 | 75.0% | 138 | 53.3% | 73 | 41.2% | 56 |

| No | 82.0% | 169 | 38.5% | 84 | 53.0% | 44 | 30.5% | 25 |

| p<.0001 | p<.0001 | p=.97 | p=.11 | |||||

| Been asked to sext | ||||||||

| Yes | 98.8% | 167 | 76.2% | 131 | 56.9% | 74 | 44.6% | 58 |

| No | 82.5% | 188 | 38.2% | 91 | 42.2% | 38 | 27.3% | 24 |

| p<.0001 | p<.0001 | p=.03 | p<.01 | |||||

| Bothered by being asked | ||||||||

| Not at all | 100.0% | 77 | 81.8% | 63 | 53.2% | 33 | 39.7% | 25 |

| A little | 97.2% | 70 | 74.0% | 54 | 59.3% | 32 | 50.0% | 27 |

| A lot | 100.0% | 12 | 64.3% | 9 | 66.7% | 6 | 33.3% | 3 |

| A great deal | 100.0% | 6 | 83.3% | 5 | 60.0% | 3 | 50.0% | 2 |

| p=.39 | p=.40 | p=.87 | p=.65 | |||||

AOD sex = Reports using alcohol or drugs before having sex in the past year

DISCUSSION

Findings from the current study suggest that sexting behaviors are prevalent among adolescents. While some differences were identified, sexting occurred across gender, age, and race/ethnicity. Specifically, more than 1 in 4 adolescents have sent a nude picture of her/himself through electronic means, about half have been asked to send a nude picture, and about a third have asked for a nude picture to be sent to them. Boys were more likely to ask and girls more likely to have been asked for a sext. These rates are at the higher end of estimates generated from available online research and opinion polls,13–15 and substantially higher than recently published data suggesting that only a little over 1% of teens had sexted naked pictures.19 The relatively older sample of adolescents in the current study may explain some of the higher rates of sexting. In addition, findings from the current study are based on a more representative sample than those used in previous research, suggesting a more accurate representation of U.S. adolescents’ sexting behaviors.

Our findings also make it clear that the commonness of a behavior does not condone its occurrence. On the contrary, we found that teens are generally bothered by being asked to send a naked picture. In fact, nearly all girls were bothered by having been asked. Even among boys, over half were bothered at least a little by having been asked. Given these results, future research should define more closely what is meant by being bothered (e.g., annoyed vs. embarrassed).

For both boys and girls, teens who engaged in sexting behaviors were more likely to have begun dating and to have had sex than those who did not sext. Although our survey did not ask for the identity of the sender/receiver of the sext messages, these results suggest that sexting may occur within the context of dating. This assertion is consistent with a recent focus group conducted by the Pew Research Center,17 in which teens reported that sexting often occurs between intimate partners or where at least one member participating in the sext hopes to be in a relationship. Perhaps most telling is the finding that adolescents who have engaged in a variety of sexting behaviors were overwhelmingly more likely to have had sex than their peers who have not experienced sexting. Because of the cross-sectional nature of our data, we were unable to determine the temporal relationship between sexting and sexual behavior. However, it is possible that sexting may act as an initial sexual approach or as a way of introducing sex in the relationship. It could also be that sending a sexually explicit image invites sexual advances from an intimate partner or other peers.21 Conversely, it may be that once an individual has sex they are more open to expressing themselves sexually or that the level of flirtation escalates to include nudity. Regardless of the reason for the association, current findings posit that sexting may be a fairly reliable indicator of sexual behavior.

Moreover, teen girls who engaged in sexting behaviors also had a higher prevalence of risky sex behaviors, including multiple partners and using drugs or alcohol before sex. Thus, among girls the use of sexting behaviors appears to coincide with much higher engagement in risky sex behaviors. The same is not true for boys, for whom only having been asked for a sext was related to risky sex behaviors. It is possible that sexting, like actual sexual behaviors, is perceived more permissively22 and positively23 for boys, and thus not considered a risky behavior and therefore less likely to be associated with other risky behaviors.24 Girls, on the other hand, may risk being stigmatized for their sexting behaviors (e.g., being identified as a “slut”).23 If true, it would be expected to correlate with other risky behaviors. Additional research, including qualitative studies, is needed to investigate these gender differences.

Clinical Implications

Given its prevalence and link to sexual behavior, pediatricians and other tween- and teen-focused health care providers may consider screening for sexting behaviors. Asking about sexting could provide insight into whether a teen is likely engaging in other sexual behaviors for boys and girls, or risky sexual behaviors for girls, and questions about sexting may be easier for teens to answer honestly than questions about sex and risky sex behaviors. However, this should be evaluated in future research. Regardless, talking to teen patients about sexting provides an opportunity to discuss sexual behavior and safe sex. Indeed, these findings reinforce calls by the American Academy of Pediatrics to discuss teen sexting with patients and patients’ parents (see http://www.aap.org/advocacy/releases/june09socialmedia.htm).25

Policy Implications

The ubiquity of sexting supports recent efforts to soften the penalties of this behavior.10,17,25 Under most existing laws, if our findings were extrapolated nationally, several million teens could be prosecuted for child pornography.10 Sexting may be more aptly conceptualized as a new type of sexual behavior in which teens may (or may not) engage. In an adolescent period characterized by identity development and formation, sexting should not be considered equivalent to childhood sexual assault, molestation, and date rape. Doing so not only unjustly punishes youthful indiscretions, but minimizes the severity and seriousness of true sexual assault against minors. At the same time, any efforts to soften penalties of sexting should be done cautiously so as not to introduce legal loopholes for other cases involving sexual assault.26 Further, while juvenile-to-juvenile sexting may come to be understood as part of adolescents’ repertoire of sexual behaviors, this understanding should not be applied to sexting between teens and adults, or when sexting is used to bully others.

Limitations

We do not know from the current study if adolescents’ sexual experiences and engagement in risky sexual behavior preceded or followed sexting behaviors. Longitudinal studies that explicitly account for the time sequence are needed. In addition, questions on sexting were developed for this study and were not vetted by teens, potentially limiting the validity of our findings. We also did not inquire about the identity of whom teens sexted, who asked for a sext, and under what conditions sexting occurred. Future research, including qualitative studies, should include contextual questions. In addition, findings regarding 18 year olds should be interpreted with caution due to the relatively small number of these participants in our sample. Finally, although the sample represents a diverse cross-section of students from several high schools/districts, it is possible that regional differences influenced prevalence estimates. Despite these limitations, the current study is among the first to examine the prevalence and nature of sexting in a racially and ethnically diverse school-based sample, and to demonstrate a link between sexting and sexual behavior.

Conclusions

While some differences were noted with respect to gender, age, and race/ethnicity, it is clear that teen sexting is prevalent among adolescents. Over one quarter of teens in the current sample reported sending a naked picture of themselves to another teen, and over half have been asked to send one. Perhaps most telling is the finding that teens who have participated in sexting were substantially more likely to report a history of sexual intercourse (for boys and girls) and risky sexual behavior (for girls). The use of cell phones and text messaging has increased rapidly over the past five years, and the age of cell phone ownership has become steadily younger.16,27 It is therefore essential that pediatricians, adolescent medicine specialists, and other health care providers become familiar with, routinely ask about, and know how to respond to teen sexting.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Temple is supported by Award Number K23HD059916 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. Dr. van den Berg is supported by Award Number K23HD06326102 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development or the national Institutes of Health. This study was also made possible with funding to Dr. Temple by the Hogg Foundation for Mental Health (JRG-082) and the John Sealy Memorial Endowment Fund for Biomedical Research. Dr. Temple has full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. This work would not have been possible without the permission and assistance of the schools and school districts.

Footnotes

None of the authors have conflicts of interest or financial disclosures to report.

References

- 1.Bialik C. Which is Epidemic – Sexting or Worrying About It? [Accessed November 1, 2011];Wall Street Journal. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB123913888769898347.html. Updated April 8, 2009.

- 2.Gifford NV. Sexting in the USA. Washington, DC: Family Online Safety Institute Report 2009; 2009. [Accessed November 1, 2011]. http://www.fosi.org/downloads/resources/Sexting.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Sexting: A brief guide for educators and parents. Cyberbullying Research Center; [Accessed October 18, 2011]. Available at: http://www.cyberbullying.us/Sexting_Fact_Sheet.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bensonhurst Junior High School Suspended 32 For Sexting. Huffington Post; [Accessed December 19, 2011]. Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/12/19/bensonhurst-junior-high-s_n_1157764.html. Updated December 19, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolak J, Finkelhor D, Mitchell KJ. How often are teens arrested for sexting? Data from a national sample of police cases. Pediatrics. 2012;129:4–12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunker M. Sexting surprise: Teens face child porn charges, 6 Pa. high school students busted after sharing nude photos via cell phones. [Accessed November 1, 2011];MSNBC.com. 2009 Jan 15; Available at http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/28679588/#.TrBTv_Sa9tk.

- 7.Feyerick D, Steffen S. “Sexting” lands teen on sex offender list. [Accessed October 18, 2011];CNN.com. 2009 Apr 8; Available at: http://www.cnn.com/2009/CRIME/04/07/sexting.busts/index.html?iref=hpmostpop.

- 8.Holley J. State senator’s bill would reduce penalty for teen sexting. [Accessed September 26, 2011];Houston Chronicle. 2011 Feb 7; Available at: Chron.com Web site. http://www.chron.com/news/houston-texas/article/State-senator-s-bill-would-reduce-penalty-for-1685811.php.

- 9.Jaishankar K. Sexting: A new form of victimless crime? International Journal of Cyber Criminology. 2009;3(1):21–25. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker J, Moak S. Child’s play or child pornography: The need for better laws regarding sexting. [Accessed November 1, 2011];ACJS Today. 2010 XXXV(1):3–9. Available at: www.acjs.org/pubs/uploads/acjstoday_february_2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Celizic M. Her teen committed suicide over “sexting”. [Accessed October 18, 2011];MSNBC.com. Available at: http://today.msnbc.msn.com/id/29546030#.Tp4Gp5xU2KM. Updated March 6, 2009.

- 12.McCarthy C. Report: Teen blackmailed classmates via facebook. [Accessed October 18, 2011];Cnet.com. Available at: http://news.cnet.com/8301-13577_3-10157626-36.html. Updated February 5, 2009.

- 13. [Accessed September 26, 2011];A thin line: 2009 AP-TVT digital abuse study. Available at: www.athinline.org/MTV-AP_Digital_Abuse_Study_Executive_Summary.pdf.

- 14.Cox Communications. [Accessed November 1, 2011];Teen Online & Wireless Safety Survey. 2009 Available at http://ww2.cox.com/wcm/en/aboutus/datasheet/sandiego/internetsafety.pdf.

- 15.National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Sex and Tech: Results of a Survey of Teens and Young Adults. Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregancy; 2008. [Accessed September 26, 2011]. Available at: http://www.thenationalcampaign.org/SEXTECH/PDF/SexTech_Summary.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Keeffe GS, Clarke-Pearson K Council on Commications and Media. The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics. 2011;127:800–804. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lenhart A. Teens and Sexting. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2009. [Accessed September 26, 2011]. Available at: http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2009/Teens-and-Sexting.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dowdell EB, Burgess AW, Flores JR. Online social networking patterns among adolescents, young adults, and sexual offenders. Amer J Nurs. 2011;111:28–36. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000399310.83160.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell KJ, Finkelhor D, Jones LM, Wolak J. Prevalence and Characteristics of Youth Sexting: A National Study. Pediatrics. 2012;129:13–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christian L, Keeter S, Purcell K, Smith A. Assessing the Cell Phone Challenge to Survey Research in 2010. Pew Internet; [Accessed January 31, 2012]. Available at: http://pewresearch.org/pubs/1601/assessing-cell-phone-challenge-in-public-opinion-surveys. Published May 20, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown JD, Keller S, Stern S. Sex, sexuality, and sexed: Adolescents and the media. The Prevention Researcher. 2009;16:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carvajal SC, Parcel GS, Basen-Engquist K, et al. Psychosocial predictors of delay of rst sexual intercourse by adolescents. Health Psychol. 1999;18:443–52. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuffee JJ, Hallfors DD, Waller MW. Racial and gender differences in adolescent sexual attitudes and longitudinal associations with coital debut. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: A psychosocial framework for understanding and action. J Adolesc Health. 1991;12:597–605. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(91)90007-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Academy of Pediatrics. [Accessed November 2, 2011];Talking to kids and teens about social media and sexting. Available at: http://www.aap.org/advocacy/releases/june09socialmedia.htm.

- 26.Muscari ME. Sexting: New technology, old problem. Medscape Public Health and Prevention; 2010. [Accessed November 2, 2011]. Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/702078. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rideout VJ, Foehr UG, Roberts DF. Generation M2: Media in the lives of 8–18 year-olds. Kaiser Family Foundation; Jan, 2010. [Accessed November 2, 2011]. Available at http://www.kff.org/entmedia/upload/8010.pdf. [Google Scholar]