Abstract

Although experimental behavioral interventions to prevent HIV are generally designed to correct undesirable epidemiological trends, it is presently unknown whether the resulting body of behavioral interventions is adequate to correct the social disparities in HIV-prevalence and incidence present in the United States. Two large, diverse-population meta-analytic databases were reanalyzed to estimate potential perpetuation and change in demographic and behavioral gaps as a result of introducing the available behavioral interventions advocating condom use. This review suggested that, if uniformly applied across populations, the analyzed set of experimental (i.e. under testing) interventions is well poised to correct the higher prevalence and incidence among males (vs. females) and African-Americans and Latinos (vs. other groups), but ill poised to correct the higher prevalence and incidence among younger (vs. older) people, as well as men who have sex with men, injection-drug users, and multiple partner heterosexuals (vs. other behavioral groups). Importantly, when the characteristics of the interventions most efficacious for each population were included in the analyses of behavior change, results replicated with three exceptions. Specifically, after accounting for interactions of intervention and facilitator features with characteristics of the recipient population (e.g. gender), there was no behavior change bias for men who have sex with men, younger individuals changed their behavior more than older individuals, and African-Americans changed their behavior less than other groups.

Keywords: health disparities, HIV, communication, persuasion

Introduction

It is both common and justified to link HIV disparities to unequal structural forces, including differential access to HIV-prevention resources, uneven decision-making power, and unfair distribution of poverty (Sumartojo, 2000; Sweat & Denison, 1995). The epidemic has clearly distributed HIV in a way that further burdens already oppressed groups such as ethnic and sexual-orientation minorities. It is perhaps less common to scrutinize health interventions as potential contributors to these health disparities. Of course, early in an epidemic, intervention practices are unlikely to say much about disparities in HIV prevalence and incidence, but how about after 25 years of HIV-prevention-intervention research? Is a lack of analysis of the impact of our HIV-prevention interventions justified? On the basis of currently available data, are our experimental interventions likely to correct current social disparities in HIV? Are experimental interventions more or less acceptable and efficacious for the groups that bear the burden of the disease than other groups?

Consider US social disparities in HIV prevalence. With respect to gender, 74% of HIV cases are male (Centers for Disease Control, 2007) even when the general population has comparable representations of men and women (United States Census, 2007). With respect to race/ethnicity, 60% of the HIV cases are African-Americans (Centers for Disease Control, 2007) even though only 13% of the general population is African-American (United States Census, 2007). Likewise, 16% of the HIV cases are Latino (Centers for Disease Control, 2007) even though only 15% of the general population is Latino (United States Census, 2007). With respect to age, 50% of the HIV cases are between 16 and 34 years old (Centers for Disease Control, 2007) even though only 40% of the general population falls in this age range (United States Census, 2007). With respect to behavior, 53% of people living with HIV contracted the virus through male-to-male sexual contact, 32% through high-risk heterosexual contact, 12% through injection-drug use, and 3% through either male-to-male sexual contact or injection-drug use (Centers for Disease Control, 2007). And here again, these sex- and drug-related behaviors are sometimes higher in people living with HIV than the US population as a whole (Brady et al., 2008; National Opinion Research Center, 1998). In this context, are the experimentally tested HIV-prevention interventions more likely to reach and reduce the behavioral risk of men than women, Black/African-Americans and Latinos than whites, or men who have sex with men, injection-drug users (IDUs), and multiple-partner heterosexuals (MPHs) than other groups?

A number of meta-analyses have summarized the results of interventions as they are being tested in the trials designed to establish intervention efficacy, hereafter termed “experimental interventions” (Noar, 2008). Unfortunately, most of these meta-analyses have considered a limited number of studies and/or selected a single population, thus failing to systematically analyze efficacy associations with gender, race/ethnicity, age, or behavioral risk let alone compare these results with present social disparities. Other meta-analyses have failed to consider demographic variables altogether. Understanding health disparities necessitates estimating not just if an intervention has a significant impact in a specific group, but also whether it has differential impact across groups. Fortunately, however, two comprehensive meta-analytic databases with demographic and behavioral-risk information are available, which we reanalyzed to estimate associations of demographic and behavioral-risk information with intervention completion and behavior change in the US. The goal was to inspect differences in intervention completion and efficacy and then judge whether the analyzed intervention set is likely to close social gaps in HIV prevalence.

The meta-analysis that provided data on completion of HIV-prevention interventions, which shared 33 primary studies with Noguchi et al.' s meta-analysis, included 28,429 participants from studies that reported either or both enrollment or attrition rates (Noguchi, Durantini, Albarracín, & Glasman, 2007). The interventions included in this meta-analysis required the presence of a condom-use component. As condom use is recommended in all HIV-prevention interventions, this set also represents the broad HIV-prevention-intervention domain even though it sometimes targets other preventive behaviors such as cleaning injection equipment. The current analyses are based on the included US studies, which comprised 14,889 participants from 71 statistically-independent conditions. To calculate completion rates, we divided the number of participants who completed the study by the number who commenced the study, obtaining odds of completion. Odds of 1 represent 50/50 chances of completing versus not returning to the last session of the program and corresponding follow-up in control groups. Enrollment rates were also calculated but, due to lack of frequent report of targeted and enrolled participants, we had insufficient data for meaningful analyses. These effects were calculated in both intervention groups and non-intervention control groups (e.g. wait-list controls).

The other meta-analysis, which provided data on condom-use change, included 138,850 participants enrolled in studies of the outcomes of condom-use-promoting interventions (Albarracín et al., 2005). Again, condom use is recommended even when other behaviors such as cleaning injection equipment are advocated, providing the broadest possible HIV-prevention-intervention set. The current analyses are based on the US studies, which included 100,759 participants from 353 statistically-independent conditions. In this meta-analysis, a g statistic representing condom-use change over time was calculated by subtracting the mean level of condom use at the baseline from the mean level of condom use at the most immediate posttest for which condom use was measured, and dividing the result by the standard deviation of the pretest. For both meta-analyses, we were able to regress effect sizes on each of the following demographic and behavioral variables: (a) proportion of males in the group, (b) proportion of European-Americans in the group, (c) proportion of Latinos in the group, (d) proportion of Asian-Americans or Pacific Islanders in the group, (e) median or mean age, (f) inclusion of MSM (men who have sex with men), (g) inclusion of MPHs, and (h) inclusion of IDUs. We computed analyses in both the intervention groups, as well as control groups in which no HIV-prevention intervention was delivered (e.g. wait-list control).1

Method

Meta-analysis of completion

Review and inclusion criteria

To capture interventions designed to increase condom use, we combined the key words AIDS and HIV with intervention, behavior, knowledge, education, prevention, condoms, communication, attitudes, and message. The search comprised the period between 1988 and 2006. We electronically searched Pubmed, PsycINFO, Medline, Cambridge, ERIC, and Dissertations Database, as well as relevant conference databases. We also manually searched all available issues appearing during or after 1980 of the journals AIDS, AIDS Education and Prevention, AIDS and Behavior, American Journal of Public Health, Basic and Applied Social Psychology, Health Psychology, Journal of the American Medical Association, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Finally, we checked prior meta-analyses, examined cross-references in the obtained reports, and requested reports from researchers in this area.

The selection criteria were strict because, due to objectives not relevant to this article, we needed to identify studies that had baseline measures of knowledge, motivation, or condom use. In addition, given the focus on attrition, we required precise reports of the sample sizes at the beginning and end of the intervention. Various other criteria were relevant as well.

-

(1)

Given our hypotheses, we synthesized studies that provided information on the levels of baseline knowledge, motivation, or condom use of the audience upon entering the intervention. These measures could be retrieved only when researchers reported the baseline levels of one of these measures for all commencers rather than only posttest completers.

-

(2)

To be eligible, studies had to include at least one standardized behavioral intervention designed to increase condom use among recipients. In addition, reports often included comparison and control conditions. Groups that researchers treated as “comparison” conditions but that participated in an intervention were considered treatment groups. We considered control groups only those not exposed to any kind of HIV-related intervention at the time of the study (e.g. waiting-list groups; education programs on other health topics; for similar criteria in a different meta-analysis, see Albarracín et al., 2003, 2005). These controls provide an estimate of what occurs in the absence of systematic exposure to an HIV-prevention intervention.

-

(3)

Studies were eligible only when they provided statistics to calculate either or both acceptance or completion. In practice, however, all studies reporting acceptance also reported completion. Completion rates required the initial number of participants and the number of completers of the intervention or the immediate post-test. Acceptance rates required initial number of participants and the numbers of people targeted for recruitment, but are not considered in the current analyses.

-

(4)

The need of measures of completion excluded reports containing pre- and post- test information from different audiences.

-

(5)

We only included studies conducted in the United States.

Coding of moderators

Independent raters coded relevant characteristics of the reports and methods used in the study. After the initial training, the overall inter-coder agreement was 95%. Occasional disagreements were resolved by discussion and further examination of the studies. For all variables, reliabilities were superior to r and k = 0.70. Of interest to the current article, we recorded the presence or absence of the different intervention components. (a) HIV information and/or information about condom use, (b) attitudinal arguments, such as statements about the positive implications of using condoms for the health of the partners and for the romantic relationship, (c) normative arguments asserting support for condom use on the part of friends, family members, or partners, (d) threat arguments, such as discussions about the recipient's personal risk of contracting HIV or other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), (e) behavioral strategies such as training negotiation skills (e.g. role-playing condom-use negotiation) and condom-use behavioral skills (e.g. opening wrapper without tearing it, unrolling condom in proper direction), (f) HIV counseling and testing, and (g) provision of condoms. We also recorded demographics of the participants as well as specific characteristics and behaviors that are associated with HIV-infection risk. These characteristics were recorded for the commencers and completers of the intervention or of the immediate follow-up. Specifically, we retrieved: (a) sample size; (b) percentage of females in each group; (c) mean or median age; and (d) percentage of participants of European, African, Latin-American, Asian, and Native-North-American descent. Further, we registered the inclusion of various behaviorally-at-risk groups, including men who have sex with men, intravenous-drug users, and multiple-partner heterosexuals. We classified each treatment group according to whether (a) the setting of the recruitment and intervention comprised clinical or community settings (community-based organizations, streets, bars, work settings, or schools), (b) whether the intervention was group based, (c) whether the source was a professionally-trained expert, (d) whether the intervention included gender-matched sources, and (e) whether the intervention included ethnically matched sources. Further, we recorded (a) the planned number of sessions, and (b) whether participants were paid for their participation.

Effect size calculation and analysis

For each paper, we retrieved each available intervention and control condition. In addition, whenever the report distinguished samples, we attempted to treat each sample separately. In three papers, however, interventions were collapsed into a single group. Hence, all statistics for these reports represent an average. In no case did we merge interventions and control groups.

As measures of completion, we recorded the number of commencers and completers of the intervention. When available, these data allowed us to compute the proportion of completion in a sample. These indices were then converted into odds (proportion of declinations). Odds of 1 correspond to equal probability of completion. Odds greater than 1 correspond to more likely completion than drop out. Odds smaller than 1 correspond to more likely drop out than completion.

We first calculated weighted-mean odds as estimates of the degree of completion and performed corrections for sample-size bias. As described before, proportions of completion were converted into odds, and then the odds were log transformed (see Haddock, Rindskopf, & Shadish, 1998). We used Hedges and Olkin's (1985) procedures to correct the effects for sample-size bias,2 as well as to calculate weighted-mean effect sizes, confidence intervals, and homogeneity statistics. Calculations of the between-subject variance followed procedures developed by Hedges and Olkin (1985).

Computations of effect sizes were performed using fixed-effects procedures. (Hedges & Olkin, 1985; Hedges & Vevea, 1998; Rosenthal, 1995; Wang & Bushman, 1999; but see Hunter & Schmidt, 2000; Raudenbush, 1994). The weights for fixed-effects followed Hedges and Olkin's computational formulas, and were used because we assume that the variance in effect sizes can be explained by study moderators. The moderator analyses included regressions using fixed-effects weights, with the error of the beta weights being corrected based on Hedges and Olkin's (1985) recommendations.

Meta-analysis of behavior change

Review and inclusion criteria

We conducted a review of reports that were available by September of 2003. First, we conducted a computerized search of Medline, PsycINFO, ERIC, Social Science Citation Index, and Dissertation Abstracts International using a number of keywords, including HIV (AIDS) messages, HIV (AIDS) communications, HIV (AIDS) interventions, HIV (AIDS) prevention, and health education and HIV (AIDS). Second, we manually searched all available issues appearing during or after 1985 of the journals, AIDS, AIDS Education and Prevention, AIDS Research, American Behavioral Scientist, American Journal of Community Psychology, American Journal of Nursing, American Journal of Public Health, Basic and Applied Social Psychology, Communication Research, Communications, Health Communication, Health Education Quarterly, Health Education Research, Health Psychology, Journal of the American Medical Association, Journal of Applied Communication Research, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Journal of Sex Research, Medical Anthropology, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Qualitative Health Research, and Social Science and Medicine. We also checked cross-references in the obtained reports, sent requests for information to researchers funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH), and contacted selected experts and agencies who could provide relevant materials.

We used several eligibility criteria to gather an optimal sample of studies that could serve our objectives well, as explained below.

-

(1)

Studies were included if they described the outcomes of a behavioral intervention to promote the use of condoms. We excluded interventions to promote abstinence from sex, except when they also included a condom-use component. The interventions sometimes included other targets, such as drug-related behaviors.

-

(2)

The studies we included concerned outcomes of different types of interventions. Therefore, we included simple communications, as well as interventions in which recipients engaged in behaviors as part of the intervention (i.e. role-playing, practicing condom-use related skills, and HIV counseling and testing).

-

(3)

We only included studies that provided information to calculate the effect of interventions over time and excluded reports without a pretest. Most of the reports obtained pre and posttest measures on the same sample, but others used independent samples at each time (for an explanation of the advantages of the use of independent samples for longitudinal studies, see Cook & Campbell, 1979).3

-

(4)

We only included studies conducted in the United States.

Coding of moderators

Two independent raters coded characteristics relevant to the report and the methods used in the studies. Inter-coder agreement for all categories included in the coding sheet was 85%, and inter-coder-reliability coefficients. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and further examination of the studies.

We recorded the type of intervention and strategy used in each case. Passive strategies included (a) factual information (i.e. mechanisms of HIV, HIV-transmission, HIV-prevention), (b) attitudinal arguments, such as discussions of the positive implications of using condoms for the health of the partners and for the romantic relationship, (c) normative arguments about support of condom use provided by friends, family members, or partners, (d) threat-inducing arguments, such as discussions about the recipients' personal risk of contracting HIV or other STIs. We also recorded the use of (a) behavioral-skill training (e.g. condom-use skills such as practice with unwrapping and applying condoms; interpersonal skills such as role playing of interpersonal conflict over condom use and initiation of discussions about protection; self-management skills such as practice in decision-making while intoxicated, avoidance of risky situations), (b) HIV counseling and testing involved the administration of a seropositivity test as well as the counseling in place, and (c) condom provision.

We also recorded characteristics of the participants, including demographics of the target group as well as specific characteristics and behaviors of the target group that are associated with HIV-infection risk. To describe the target population, we retrieved the: (a) percentage of males in each group; (b) mean age; (c) percentage of European Americans, African-Americans, Latino American, Asian American, and Native Americans; (d) inclusion of men who have sex with men, multiple-partner heterosexuals, and intravenous-drug users. Moreover, we classified each intervention group according to (a) the setting of the intervention (i.e. community vs. other). We also recorded (a) whether exposure to the communication was individual or in groups, (b) whether the facilitator was a professional expert, (c) whether the facilitator was gender-matched to the participants, (d) the duration of the communication in hours, and (e) whether participants were paid in exchange for participation.

Retrieval of effect sizes and analysis

Two raters calculated effect sizes independently. Disagreements were checked with a third researcher and resolved by discussion. Raters were instructed to calculate effect sizes representing change from the pretest to the most immediate posttest. When there was more than one measure of behavior, we first calculated effect sizes for each one and then obtained the average, which was used as the effect size for that particular variable.

To represent change from pretest to posttest measures, we used Becker's (1988) g, which is calculated by subtracting the mean at the posttest from the mean at the pretest and dividing the difference by the standard deviation of the pretest measure. This measure controls for the inflation in the standard deviation following treatment (for an excellent analysis of the problem, see Carlson & Schmidt, 1999). Effect sizes were also derived from exact reports of t-tests, F-ratios, proportions, p-values, and confidence intervals. To derive effect sizes for within-subject studies, one needs the correlation between posttest and pretest measures to calculate effect sizes. Because some reports did not offer this information, we adopted procedures recommended by Becker (1988) as well as by Dunlap, Cortina, Vaslow, and Burke (1996). We explain these procedures when they become relevant.

We also estimated effect sizes when a report contained inexactly described p-values – such as when the authors indicated that a given finding was not significant at 0.05 – using the appropriate within- or between-subjects procedures. Thus, a reported nonsignificant finding was estimated to have a probability of 0.99, whereas a significant finding was estimated to have a probability at the level of the cutoff value used in the study (e.g. 0.05 or 0.01). However, because the use of such reports may lead to incorrect estimations, we conducted separate analyses on the set of exactly-reported effect sizes, as well as on all the effect sizes, including the ones estimated on the basis of inexactly-reported p values. Because both sets of analyses yielded similar results, we only report the results that included all effect sizes.

We calculated effect sizes representing change in attitudes, norms, control perceptions, intentions, behavioral skills, knowledge, perceived severity, and perceived susceptibility, although only condom-use behavior was considered in this article. Condom-use measures included assessments on subjective frequency scales, as well as reports of the percentage and number of times participants use condoms over a period of time. For example, the Community Demonstration Projects Research Group (Centers for Disease Control, 1993) asked participants “When you have vaginal sex with your main partner, how often do you use a condom?” (p. 11), and participants provided their response on a scale from 1 (every time) to 5 (never). To obtain a more precise report of condom use, Ploem and Byers (1997) asked participants to report the frequency of sexual intercourse over the previous 4 weeks, as well as the number of occasions of sexual intercourse for which condoms were used. The researchers then derived the percentage of condom use for each participant. Similarly, Belcher et al. (1998) asked participants to list the first name of all of their sex partners in the previous 90 days. For each name listed, participants were then asked to identify the partner's gender, the partner type (regular, casual, or new), the total frequency of vaginal sex, the frequency of condom-protected vaginal sex, the total frequency of anal sex, and the frequency of condom-protected anal sex. Percentages were again derived based on relative frequencies.

We calculated weighted mean effect sizes to examine change over time in intervention and control groups, and performed corrections for sample-size bias to estimate d. We used Hedges and Olkin's (1985) procedures to correct the effects for sample-size bias,4 calculate weighted mean effect sizes, d, confidence intervals, and homogeneity statistics, Q, which test the hypothesis that the observed variance in effect sizes is no greater than that expected by sampling error alone. Calculations of the between-subject variance followed procedures developed by Hedges and Olkin (1985). For within-subjects designs, we calculated the variance of effect sizes using Morris' (2000) procedures. Specifically, we performed calculations for the variance of within-subject effect sizes using three alternate correlations between pre and posttest measures (see also, Albarracín et al., 2003). Thus, we assumed r = 0 and r = 0.99 as the most extreme values, and also imputed correlations from Project RESPECT (see Kamb et al., 1998), which provided moderate values of this association. Because results were similar regardless of the correlation we used, we present only the ones with the imputed correlations (see also Albarracín et al., 2003).

Computations of effect sizes were performed using fixed-effects procedures. In the first case, one assumes a fixed population effect and estimates its sampling variance, which is an inverse function of the sample size of each group. The inverse of the effect size's variance is used to weigh effect sizes before obtaining average values. Thus, effect sizes from studies with larger Ns are considered more precise and carry more weight than effect sizes obtained from studies with smaller sample sizes. These procedures are powerful and produce narrow confidence intervals (Rosenthal, 1995; Wang & Bushman, 1999). Presumably, fixed-effects models are reasonable when one assumes that effect sizes vary as a result of a few, identifiable study characteristics, whereas random-effects models are appropriate when variation derives from multiple, unidentifiable sources (Raudenbush, 1994).

Results and discussion

We included 29 research reports that included completion data from a total of 59 independent groups. We also included 146 reports that included behavior change data from a total of 353 independent groups. All references appear in the Appendix. Tables 1 and 2 present descriptive statistics for the meta-analyses of completion and behavior change. The studies had great gender and ethnic diversity and the interventions included various methods to elicit change in behavior.

Table 1.

Meta-analysis of completion.

| Variable | Statistic | k |

|---|---|---|

| Percent of interventions that included information about HIV | 85 | 52 |

| Percent of interventions that included attitudinal arguments | 30 | 53 |

| Percent of interventions that included threat arguments | 49 | 53 |

| Percent of interventions that included behavioral strategies | 46 | 52 |

| Percent of interventions that included HIV testing | 29 | 53 |

| Percent of interventions that included condom distribution | 26 | 53 |

| Mean percent of male participants | 35.08 | 59 |

| Mean age | 23.98 | 59 |

| Mean percent of European-American participants | 21 | 58 |

| Mean percent of African-American participants | 59 | 53 |

| Mean percent of Latino-American participants | 13 | 55 |

| Mean percent of Asian-American participants | 4 | 55 |

| Mean percent of native American participants | 0 | 55 |

| Percent of groups that included MSM | 9 | 59 |

| Percent of groups that included IDUs | 5 | 59 |

| Percent of groups that included MPHs | 17 | 59 |

| Percent of interventions conducted in a community setting | 85 | 52 |

| Percent of group-based interventions | 53 | 49 |

| Percent of expert delivered interventions | 77 | 53 |

| Percent of interventions that included a gender matched facilitator | 100 | |

| Percent of interventions that included an ethnically matched facilitator | NI | NA |

| Planned number of sessions | 3.6 | 53 |

| Percent of interventions in which participants were paid | 22 | 59 |

k = number of groups.

Table 2.

Meta-analysis of behavior change.

| Variable | Statistic | k |

|---|---|---|

| Percent of interventions that included information about HIV | 46 | 283 |

| Percent of interventions that included attitudinal arguments | 16 | 283 |

| Percent of interventions that included threat arguments | 45 | 283 |

| Percent of interventions that included behavioral strategies | 72 | 283 |

| Percent of interventions that included HIV testing | 20 | 283 |

| Percent of interventions that included condom distribution | 46 | 131 |

| Mean percent of male participants | 43 | 342 |

| Mean age | 26 | 243 |

| Mean percent of European-American participants | 38 | 317 |

| Mean percent of African-American participants | 47 | 322 |

| Mean percent of Latino-American participants | 14 | 291 |

| Mean percent of Asian-American participants | 4 | 258 |

| Mean percent of native-American participants | 0.47 | 257 |

| Percent of groups that included MSM | 13 | 353 |

| Percent of groups that included IDUs | 18 | 353 |

| Percent of groups that included MPHs | 18 | 353 |

| Percent of interventions conducted in a community setting | 21 | 283 |

| Percent of group-based interventions | 77 | 283 |

| Percent of expert delivered interventions | 51 | 217 |

| Percent of interventions that included a gender matched facilitator | 41 | 171 |

| Percent of interventions that included an ethnically matched facilitator | 55 | 111 |

| Duration of intervention in hours | 8 | 217 |

| Percent of interventions in which participants were paid | 37 | 283 |

k = number of groups.

Overall effects: What would we gain if the same set of interventions were applied across all groups?

We examined if the proportion of males in the samples of intervention recipients is positively correlated with the degree of completion or behavior change obtained. One complication, however, is the potential presence of a similar correlation between the proportion of men in a sample and naturally-occurring outcomes (e.g. changes in behavior). As a result, any association between a sample characteristic, such as gender, and either intervention completion or behavior change in intervention groups must be examined in comparison with the same association in control groups. We thus analyzed the effect sizes reflecting completion and behavior change as a function of each sample characteristics of interest and a dummy code representing experimental vs. control condition (experimental = 1; control = 0). An interaction term was included in the regression equation to determine if the influence of each sample characteristic on completion or behavior change was influenced by the intervention. A significant interaction indicates that the simple slopes for the effect of the sample characteristic on the effect size significantly differ across treatment and control conditions. All regressions were weighted by the inverse of the variance of the predicted effect sizes, with the standard errors appropriately corrected using fixed-effects models.

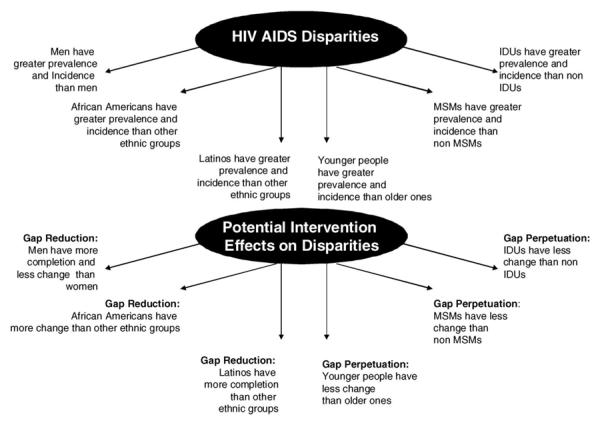

A summary of the data from the two target meta-analytic databases appears in Tables 3 and 4, presented for both intervention and control groups. We comment only on significant differences, which are highlighted in the table. These comments are also summarized in Figure 1, which depicts HIV disparities along with the likely effects of the interventions on either closing or perpetuating existing social gaps. The data in the first row of the tables indicate that the proportion of males in the synthesized samples. As a result of the interventions, samples with greater proportions of men had more completion but less behavior change. Overall then, interventions appeared to reduce the natural (control group) noncompliance of male groups and are probably well poised to reduce the male burden in HIV present in the US. As a result, the HIV prevalence among women may increase.

Table 3.

Simple regressions of completion on demographic and behavior risk characteristics.

| Interventions | Controls | Difference between correlations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of men | 0.14*** | −0.53*** | *** |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Proportion of participants from European-Americans | 00.25*** | −0.53*** | *** |

| Proportion of participants from African-Americans | −0.54*** | −0.13 | ns |

| Proportion of participants from Latinos | 0.33*** | −0.33*** | * |

| Proportion of participants from Asian/Pacific Islander backgrounds | 0.12*** | 0.54*** | ns |

| Mean or median age | 0.23*** | 0.02 | ns |

| Behavioral risks | |||

| Sample included MSMa | −0.03 | −0.07 | ns |

| Sample included MPHsa | −0.20*** | 0.43*** | *** |

| Sample included IDUsa | −0.06* | - | - |

Entries are standardized regression coefficients.

MSM, men who have sex with men; MPH, multiple partner heterosexuals; IDU, injection drug users.

1 = yes, included, 0 = no, not included.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Table 4.

Simple regressions of behavior change on demographic and behavior risk characteristics.

| Correlation in intervention groups | Correlations in control groups | Difference between correlations | Are described association in intervention groups and difference with the association in control groups retained after controlling for group specific strategies? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of men | 0.06*** | 0.17* | ns | The correlation in intervention groups becomes nonsignificant, but is still not significantly different from the control correlation |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Proportion of participants from European-Americans | −0.32*** | 0.22** | *** | The correlation in the intervention groups becomes nonsignificant but is still more negative than the control correlation |

| Proportion of participants from African-Americans | 0.30*** | 0.16* | *** | The correlation in the intervention groups becomes significantly negative and significantly more negative than the control association |

| Proportion of participants from Latinos | −0.02 | −0.18* | ns | The correlation in the intervention groups remains nonsignificant and nonsignificantly different from the control correlation |

| Proportion of participants from Asian/Pacific Islander backgrounds | 0.02 | −0.41*** | *** | The correlation in the intervention groups remains nonsignificant and significantly more positive than the control correlation |

| Mean or median age | 0.35*** | 0.25** | ** | The correlation in the intervention groups becomes nonsignificantly negative and significantly more negative than the control correlation |

| Behavioral risks | ||||

| Sample included MSMa | −0.27*** | 0 | *** | The correlation in the intervention groups becomes nonsignificant and not significantly different from the control correlation |

| Sample included MPHsa | 0.09*** | 0.12 | ns | The correlation in the intervention groups becomes nonsignificant but is still not significantly different from the control correlation |

| Sample included IDUsa | −0.17*** | 0.28* | *** | The correlation in the intervention groups becomes nonsignificant but is still significantly more negative than the control correlation |

Entries are standardized regression coefficients.

MSM, men who have sex with men; MPH, multiple partner heterosexuals; IDU, injection drug users.

1 = yes, included, 0 = no, not included.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Figure 1.

Summary of disparities across all interventions.

The data for the racial/ethnic composition of the synthesized samples are also interesting. As shown in the second horizontal panel of Tables 3 and 4, greater proportions of Latinos were more positively correlated with completion in interventions than controls. These results suggest that when it comes to completion, the analyzed set of experimental interventions could serve to reduce the HIV burden for Latinos. In contrast, the data for behavior change suggest that this set of interventions is well poised to reduce disparities for African-Americans but produces no bias for Latinos. Specifically, the proportion of African-Americans was more positively correlated with behavior change in intervention than control groups.

Two additional sets of analyses are also relevant to our analysis of the prospects of available interventions for reducing social disparities in HIV. First, older age was more positively correlated with behavior change in intervention groups than control groups. Second, samples including MPHs had less completion as a result of interventions than samples not including this population. Third, the inclusions of MSM and IDUs were more negatively correlated with behavior change in intervention than control groups. The implication from these data is that the current intervention set is better suited for older than younger samples, and better suited for groups other than MSM and IDUs. As young people, MSM and IDUs continue to be disproportionately affected by the epidemic, these data suggests that this set of interventions may be ill-armed to close the age and behavioral risk gaps in the US.

Analyses after the group specific strategies are considered: What would we gain after applying the most efficacious strategies for each recipient population?

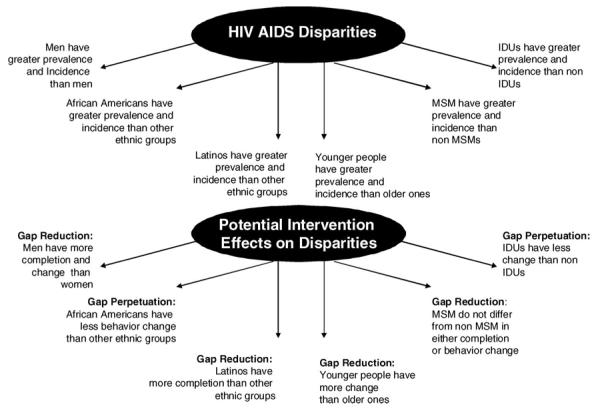

Of course one could argue that a selective application of the more efficacious interventions for a particular group might be an adequate way of resolving disparities. For example, expert facilitators have been shown to stimulate more change than peers and this difference is even stronger among African-Americans. There are also important differences in how the groups of interest in this article respond to the use of different information contents. Figure 2 shows decision trees constructed based on the data from the second meta-analysis (Albarracín et al., 2005) and describes various important interactions identified previously. Moreover, it has been shown that women change more in response to female experts, African-Americans change more in response to African-American experts (Durantini, Albarracín, Earl, & Mitchell, 2006), Latinos change more in response to Latino peers (Albarracín, Albarracín, & Durantini, 2008), MSM change more in response to all experts, and IDUs and MPHs respond better to experts accompanied by members of the recipients risk group. If one took into account these interactions, any remaining difference in the effect of a sample characteristic would imply that even after using the most appropriate known interventions biases in the effect of that characteristic remain. We were thus interested in performing these analyses.

Figure 2.

Summary of strategies that are effective for different groups (adapted from Albarracín et al., 2005).

The completion data were not sufficient to answer the question of potential disparities even after using the most promising intervention types for specific groups. However, the behavior change dataset is large and thus enabled such analyses. Specifically, we repeated the analyses described in Table 4 for the treatment groups only and after incorporating each sample characteristic along with the use of an expert or a peer facilitator, the similarity of the facilitator and the recipients in terms of ethnicity, gender, and risk group, the use of fear-inducing arguments, the use of normative arguments, the use of attitudinal arguments, the provision of information, the use of arguments to increase self-efficacy, the provision of condoms, the inclusion of behavior skills training, the inclusion of an HIV test, the duration of the intervention, and the use of a group or an individual delivery format. In addition to these moderators, each analysis included all interactions between the sample characteristic of interest and each of the other moderators. The regression weight for each sample characteristic (e.g. proportion of men in the sample) was then compared with the same weight in the control condition using confidence intervals constructed with the corrected standard errors. These supplementary analyses indicated that once the best possible combinations of recipient and strategies were taken into account the aforementioned findings replicated with three exceptions. First, the behavior-change bias for MSM disappeared. In addition, African-Americans changed their behavior less than other groups and younger recipients changed their behavior more than older ones. These conclusions are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Summary of disparities after controlling for interactions between group characteristics and intervention/facilitator features (for behavior change data only).

Final note

Naturally, attempting to answer the question that guided this paper is not simple. To begin, the interventions examined here had to include an intervention delivered to groups and individuals and thus excluded interventions in which only a structural modification was tested. As structural interventions are proposed to be the answer to many structural factors related to the problem of health disparities, future research should conduct similar analyses of those interventions. Moreover, we offer some tentative answers, but recognize that more precise data might be collected by the public health system with good tracking of implementation of interventions in the US. This tracking must include an evaluation of behavior change as well as enrollment and attrition, all factors that are central to reaching a community and reducing the burden of a disease. Other increases in precision would be facilitated as more data accrue and permit similar analyses for all possible ways of crossing ethnicity, gender, and risk behavior, as well as for the possible factors underlying these patterns (see Albarracín et al., 2003, 2005; Durantini & Albarracín 2009; Durantini et al., 2006; Noguchi et al., 2007). We offer the present data as an inspiration and opportunity for the community of researchers and practitioners to engage in a critical debate: Should our interventions correct social disparities in HIV and what is the likely progress in the years to come?

Appendix

References of reports included in meta-analyses

*Behavior change

**Completion

- *.Allen S, Serufilira A, Bogaerts J, Van de Perre P, Nsengumuremyi F, Lindan C, et al. Confidential HIV testing and condom promotion in Africa. JAMA. 1992;68:3338–3343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Allen S, Tice J, Van de Perre P, Serufilira A, Hudes E, Nsengumuremyi F, et al. Effect of serotesting with counselling on condom use and seroconversion among HIV discordant couples in Africa. British Medical Journal. 1992;304:1605–1609. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6842.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Baldwin JI, Whiteley S, Baldwin JD. Changing AIDS and fertility-related behavior: The effectiveness of sexual education. Journal of Sex Research. 1990;2:245–262. [Google Scholar]

- *.Basen-Engquist K. Evaluation of a theory-based HIV prevention intervention for college students. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1994;6:412–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Belcher L, Kalichman S, Topping M, Smith S, Emshoff J, Nurss J. A randomized trial of a brief HIV risk reduction counseling intervention for women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:856–861. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.5.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Bell RA, Grissom S, Stephenson JJ, Fricrson R, Hunt L, Teller D. Evaluating the outcomes of AIDS education. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1990;2:71–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Bentley ME, Spratt K, Shepherd ME, Gangakhedkar RR, Thilikavathi S, Mehendale SM. HIV testing and counseling among men attending sexually transmitted disease clinics in Pune, India: Changes in condom use and sexual behavior over time. AIDS. 1978;1:1869–1877. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199814000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Berrier J, Sperling R, Preisinger J, Evans V, Maso J, Walther V. HIV/AIDS education in a prenatal clinic: An assessment. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1991;3:100–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Boekeloo BO, Schamus LA, Simmens SJ, Cheng TL, O'Connor K, D'Angelo LJ. A STD/HIV prevention trial among adolescents in managed care. Pediatrics. 1999;103:107–115. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Booth-Kewley S, Minagawa RY, Shaffer RA, Brodine SK. A behavioral intervention to prevent sexually transmitted diseases/ human immunodeficiency virus in a Marine Corps sample. Military Medicine. 2002;167:145–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Boyer C, Barrett DC, Peterman TA, Bolan G. Sexually transmitted disease (STD) and HIV risk in heterosexual adults attending a public STD clinic: Evaluation of a randomized controlled behavioral risk-reduction intervention trial. AIDS. 1997;11:359–367. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199703110-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Boyer CB, Shafer MA, Tschann JM. Evaluation of a knowledge and cognitive– behavioral skills-building intervention to prevent STDs and HIV infection in high school students. Adolescence. 1997;32:25–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Branson BM, Peterman TA, Cannon RO, Ransom R, Zaidi AA. Group counselling to prevent sexually transmitted disease and HIV: A randomized trial. Sexually Transmitted Disease. 1998;25:553–560. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199811000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Brown LK, Barone VJ, Fritz GK, Cebollero P, Nassau JH. AIDS education: The Rhode Island experience. Health Education Quarterly. 1991;18:195–206. doi: 10.1177/109019819101800205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Brown LK, Fritz GK, Barone VJ. The impact of AIDS education on junior and senior high school students. Journal of Adolescent Health Care. 1989;10:386–392. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(89)90216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Brown LK, Reynolds LA, Lourie KJ. A pilot HIV prevention program for adolescents in a psychiatric hospital. Psychiatric Services. 1997;48:531–533. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Brown WJ. An AIDS prevention campaign. American Behavioral Scientist. 1991;34:666–678. [Google Scholar]

- *.Butler RB, Schultz JR, Forsberg AD, Brown LK, Parsons JT, King G, et al. Promoting safer sex among HIV-positive youth with haemophilia: Theory, intervention, and outcome. Haemophilia. 2003;9:214–222. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2003.00722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Butts JB, Hartman S. Project BART: Effectiveness of a behavioral intervention to reduce HIV risk in adolescents. American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing. 2002;27:163–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Calsyn DA, Saxon AJ, Freeman G, Jr., Whittaker S. Ineffectiveness of AIDS education and HIV antibody testing in reducing high-risk behaviors among injection drug users. American Journal of Public Health. 1992;82:573–575. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.4.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Carey MP, Braaten LS, Maisto SA, Gleason JR, Forsyth AD, Jaworski BC. Using information, motivational enhancement, and skills training to reduce the risk of HIV infection for low-income urban women: A second randomized clinical trial. Health Psychology. 2000;19:3–11. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Carey MP, Maisto SA, Kalichman SC, Forsyth AD, Wright EM, Johnson BT. Enhancing motivation to reduce the risk of HIV infection for economically disadvantaged urban women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:531–541. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.CDC AIDS Community Demonstration Projects Research Group Community level HIV intervention in 5 cities: Final outcome data from the CDC AIDS Community Demonstration Projects. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:336–345. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.3.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Choi KH, Lew S, Vittinghoff E, Catania JA, Barrett D, Coates TJ. The efficacy of brief group counseling in HIV risk reduction among homosexual Asian and Pacific Islander men. AIDS. 1996;10:81–87. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199601000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Clark LR, Brasseux C, Richmond D, Getson P, D'Angelo LJ. Effect of HIV counseling and testing on sexually transmitted diseases and condom use in an urban adolescent population. Archive of Pediatrics and Adolescence Medicine. 1998;152:269–273. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Collins C, Kohler C, DiClemente R, Wang MQ. Evaluation of the exposure effects of a theory-based street outreach HIV intervention on African-American drug users. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1999;22:279–293. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7189(99)00018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Cottler LB, Leukefeld C, Hoffman J, Desmond D, Wechsberg W, Inciardi J, et al. Effectiveness of HIV risk-reduction initiatives among out-of-treatment non-injection drug users. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1998;30:279–290. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1998.10399703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Deren S, Davis WR, Beardsley M, Tortu S, Clatts M. Outcomes of a risk-reduction intervention with HIV-risk populations: The Harlem AIDS project. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1995;7:379–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.DiClemente RJ, Pies CA, Stoller EJ, Straits C, Olivia GE, Rutherford GW. Evaluation of school-based AIDS education curricula in San Francisco. Journal of Sex Research. 1989;26:188–198. [Google Scholar]

- *.Diers JA. (Unpublished dissertation) Princeton University; Princeton, NJ: 1999. Efficacy of a stage-based counseling intervention to reduce the risk of HIV in women. [Google Scholar]

- *.Dilley JW, Woods WJ, Sabatino J, Lihatsh T, Adler B, Casey S, et al. Changing sexual behavior among gay male repeat testers for HIV. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2002;30:177–186. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200206010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Dommeyer CJ, Marquardt JL, Gibson JE, Taylor RL. The effectiveness of an AIDS education campaign on a college campus. College Health. 1989;38:131–135. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1989.9938431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Eldridge GD, St. Lawrence JS, Little CE, Shelby MC, Brasfield TL, Sly K. Evaluation of an HIV risk reduction intervention for women entering inpatient substance abuse treatment. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1997;9:62–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Farley TA, Pompitius PF, Sabella W, Helgerson SD, Hadler JL. Evaluation of the effect of school-based education on adolescents' AIDS knowledge and attitudes. Connecticut Medicine. 1991;55:15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Ferreira-Pinto JB, Ramos R. HIV/AIDS prevention among female sexual partners of injection drug users in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. AIDS Care. 1995;7:477–488. doi: 10.1080/09540129550126425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:455–474. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Bryan AD, Misovich SJ. Information–motivation–behavioral skills model-based HIV risk behavior change intervention for inner-city high school youth. Health Psychology. 2002;21:177–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Flaskerud JH, Nyamathi AM. Effects of an AIDS education program on the knowledge, attitudes and practices of low income Black and Latina women. Journal of Community Health. 1990;15:343–355. doi: 10.1007/BF01324297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Flaskerud JH, Nyamathi AM, Uman GC. Longitudinal effects of an HIV testing and counseling programme for low-income Latina women. Ethnicity and Health. 1997;2:89–103. doi: 10.1080/13557858.1997.9961818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Fogarty LA, Heilig C, Armstrong K, Cabral R, Galavotti C, Green BM. Long term effectiveness of a peer-based intervention promoting condom and contraceptive use among HIV-positive and at-risk women. Public Health Reports. 2001;116:103–119. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Ford K, Wirawan DN, Reed BD, Muliawan P, Wolfe R. The Bali STD/AIDS study: Evaluation of an intervention for sex workers. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2002;29:50–58. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200201000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Fox LJ, Bailey PE, Clarke-Martínez KL, Coello M, Ordoñez FN, Barahona F. Condom use among high-risk women in Honduras: Evaluation of an AIDS prevention program. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1993;5:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Gerrard M, Reis TJ. Retention of contraceptive and AIDS information in the classroom. Journal of Sex Research. 1989;26:315–323. [Google Scholar]

- *.Gielen AC, Faden RR, Kass NE, O'Campo P, Chaisson R, Watkinson L. Evaluation of an HIV/AIDS education program in an urban prenatal clinic. Women's Health Issues. 1997;7:269–279. doi: 10.1016/S1049-3867(97)00029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Goertzel TG, Bluebond-Langner M. What is the impact of a campus AIDS education course? College Health. 1991;40:87–92. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1991.9936261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Harris RM, Barker Bausell R, Scott DE, Hetherington SE, Kavanagh KH. An intervention for changing high-risk HIV behaviors of African-American drug-dependent women. Research in Nursing and Health. 1998;21:239–250. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199806)21:3<239::aid-nur7>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Hillman E, Hovell MF, Williams L, Hofstetter R, Burdyshaw C, Rugg D, et al. Pregnancy, STDs, and AIDS prevention: Evaluation of new image teen theatre. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1991;3:328–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Hobfoll SE, Jackson AP. Effects of generalizability of communally oriented HIV-AIDS prevention versus general health promotion groups for single, inner-city women in urban clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:950–960. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Hobfoll SE, Jackson AP, Lavin J, Britton P, Shepherd JB. Reducing inner-city women's AIDS risk activities: A study of single, pregnant women. Health Psychology. 1994;13:397–403. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.5.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Hoffman HJA, Klein H, Crosby H, Clark DC. Project neighborhoods in action: An HIV related intervention project targeting drug abusers in Washington, DC. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 1999;76:419–434. doi: 10.1007/BF02351500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Hovell MF, Blumberg EJ, Liles S, Powell L, Morrison TC, Duran G, et al. Training AIDS and anger prevention socials kills in at-risk adolescents. Journal of Counseling and Development. 2001;79:347–355. [Google Scholar]

- *.Huszti HC, Clopton JR, Mason PJ. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome educational program: Effects on adolescents' knowledge and attitudes. Pediatrics. 1989;84:986–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Jaworski BC, Carey P. Effects of a brief, theory-based STD-prevention program for female college students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;29:417–425. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00271-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB., III Increasing condom-use intentions among sexually active Black adolescent women. Nursing Research. 1992;41:273–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Johnson JA, Sellew JF, Campbell AE, Haskell EG, Gay AA, Bell BJ. A program using medical students to teach high school students about AIDS. Journal of Medical Education. 1988;63:522–530. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198807000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kalichman SC, Cherry C, Browne-Sperling F. Effectiveness of a video-based motivational skills-building HIV risk-reduction intervention for inner-city African American men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:956–966. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kalichman SC, Kelly JA, Hunter TL, Murphy DA, Tyler R. Culturally tailored HIV-AIDS risk-reduction messages targeted to African-American urban women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:291–295. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kalichman SC, Rompa D. Sexual sensation seeking and sexual compulsivity scales: Reliability, validity, and predicting HIV risk behavior. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1995;65:586–601. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6503_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Coley B. Experimental component analysis of a behavioral HIV-AIDS prevention intervention for inner-city women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;4:687–693. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.4.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Coley B. Lack of positive outcomes from a cognitive– behavioral HIV and AIDS prevention intervention for inner-city men: Lessons from a controlled pilot study. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1997;9:299–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kalichman SC, Sikkema KJ, Kelly JA, Bulto M. Use of a brief behavioral skills intervention to prevent HIV infection among chronic mentally ill adults. Psychiatric Services. 1995;46:275–280. doi: 10.1176/ps.46.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kegeles SM, Hays RB, Coates TJ. The Mpowerment project: A communitylevel HIV prevention intervention for young gay men. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:1129–1136. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.8_pt_1.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kelly JA, McAuliffe TL, Sikkema KJ, Murphy DA, Somlai AM, Mahy GM, et al. Reduction in risk behavior among adults with severe mental illness who learned to advocate for HIV prevention. Psychiatric Services. 1997;18:1283–1288. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.10.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kelly JA, Murphy DA, Sikkema KJ, McAuliffe TL, Roffman RA, Solomon LJ, the Community HIV Prevention Research Collaborative Randomised, controlled, communitylevel HIV-prevention Intervention for sexual-risk behavior among homosexual men in US cities. Lancet. 1997;350:1500–1505. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)07439-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kelly JA, Murphy DA, Washington CD, Wilson TS, Koob JJ, Davis DR, Davantes B. The effect of HIV/AIDS intervention groups for high-risk women in urban clinics. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84:1918–1922. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.12.1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kelly JA, St. Lawrence JS, Diaz YE, Stevenson LY, Hauth AC, Brasfield TL, et al. HIV risk behavior reduction following intervention with key opinion leaders of population: An experimental analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;81:168–171. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.2.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kelly JA, St. Lawrence JS, Hood HV, Brasfield TL. Behavioral intervention to reduce AIDS risk activities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:60–67. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kelly JA, St. Lawrence JS, Stevenson LY, Hauth AC, Kalichman SC, Diaz YE, et al. Community AIDS/HIV risk reduction: The effects of endorsements by popular people in three cities. American Journal of Public Health. 1992;82:1483–1489. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.11.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kipke MD, Boyer C, Hein K. An evaluation of an AIDS risk reduction education and skills training (arrest) program. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1993;14:533–539. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(93)90136-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kirby D, Korpi M, Adivi C, Weissman J. An impact evaluation of project SNAPP: An AIDS and pregnancy prevention middle school program. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1997;9:44–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kotranski L, Semaan S, Collier K, Lauby J, Halbert J, Feighan K. Effectiveness of an HIV risk reduction counseling intervention for out-of-treatment drug users. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1998;10:19–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Landis SE, Earp JL, Koch GG. Impact of HIV testing and counseling on subsequent sexual behavior. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1992;4:61–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Lauby JL, Smith PJ, Stark M, Person B, Adams J. A communitylevel HIV prevention intervention for inner-city women: Results of the Women and Infants Demonstration Projects. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:216–222. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.2.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Lazebnik R, Grey SF, Ferguson C. Integrating substance abuse content into an HIV risk-reduction intervention: A pilot study with middle school-aged Hispanic students. Substance Abuse. 2001;22:105–117. doi: 10.1080/08897070109511450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Leonard L, Ndiaye I, Kapadia A, Eisen G, Diop O, Kanki P. HIV prevention among male clients of female sex workers in Kaolack, Senegal: Results of a peer education program. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12:21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Li X, Stanton B, Feigelman S, Galbraith J. Unprotected sex among African-American adolescents: A three-year study. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2002;94:789–796. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Lindenberg CS, Solorzano RM, Bear D, Strickland O, Galvis C, Pittman K. Reducing substance use and risky sexual behavior among young, low-income, Mexican-American women: Comparison of two interventions. Applied Nursing Research. 2002;16:137–148. doi: 10.1053/apnr.2002.34141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.MacNair RR, Elliott TR, Yoder B. AIDS prevention groups as persuasive appeals: Effects on attitudes about precautionary behaviors among persons in substance abuse treatment. Small Group Research. 1991;22:301–319. [Google Scholar]

- *.MacNair-Semands RR, Cody WK, Simono RB. Sexual behavior change associated with a college HIV course. AIDS Care. 1997;9:727–738. doi: 10.1080/713613222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Malow RM, Corrigan SA, Pena JM, Calkin AM, Bannister TM. Effectiveness of a psychoeducational approach to HIV risk behavior reduction. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1992;6:120–125. [Google Scholar]

- *.Malow RM, West JA, Corrigan SA, Pena JM, Cunningham SC. Outcome of psychoeducation for HIV risk reduction. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1994;6:113–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Mansfield CJ, Conroy ME, Emans SJ, Woods ER. A pilot study of AIDS education and counseling of high-risk adolescents in an office setting. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1993;14:115–119. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(93)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.McCusker J, Stoddard AM, Hindin RN, Garfield FB, Frost R. Changes in HIV risk behavior following alternative residential programs of drug abuse treatment and AIDS education. Annals of Epidemiology. 1996;6:119–125. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(95)00128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.McCusker J, Stoddard AM, Zapka JG, Lewis BF. Behavioral outcomes of AIDS education interventions for drug users in short term treatment. American Journal of Public Health. 1993;83:1463–1466. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.10.1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.McGuinness T, Mason M, Tolbert G, DeFontaine C. Becoming responsible teens: Promoting the health of adolescents in foster care. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurse Association. 2002;8:92–98. [Google Scholar]

- *.McMahon RC, Malow RM, Jennings TE, Gómez CJ. Effects of a cognitive– behavioral HIV prevention intervention among HIV negative male substance abusers in VA residential treatment. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2001;13:91–107. doi: 10.1521/aeap.13.1.91.18921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Mercer MA, Gates N, Holley M, Malunga L, Arnold R. Rapid KABP survey for evaluation of NGO HIV/AIDS prevention projects. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1996;8:143–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Miller RL. Assisting gay men to maintain safer sex: An evaluation of an AIDS service organization's safer sex maintenance program. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1995;7:48–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Miller RL, Klotz D, Eckholdt HM. HIV prevention with male prostitutes and patrons of hustler bars: Replication of an HIV preventive intervention. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1998;26:97–131. doi: 10.1023/a:1021886208524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Miller TE, Booraem C, Flowers JV, Iversen AE. Changes in knowledge, attitudes, and behavior as a result of a community-based AIDS prevention program. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1990;2:12–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Neaigus A, Sufian M, Friedman SR, Goldsmith DS, Stepherson B, Mota P, et al. Effect of outreach intervention on risk reduction among intravenous drug users. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1990;2:253–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Newman C, Durant RH, Seymore Ashworth C, Gaillard G. An evaluation of a school-based AIDS/HIV education program for young adolescents. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1993;5:327–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.NIMH Multisite HIV Prevention Trial Group Social– cognitive theory mediators of behavior change in the National Institute of Mental Health Multisite HIV Prevention Trial. Health Psychology. 1998;20:369–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Nyamathi AM, Flaskerud J, Bennett C, Leake B, Lewis C. Evaluation of two AIDS education programs for impoverished Latina women. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1994;6:296–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Nyamathi AM, Flaskerud JH, Leake B, Dixon EL, Lu A. Evaluating the impact of peer, nurse case-managed, and standard HIV risk-reduction programs on psychosocial and health-promoting behavioral outcomes among homeless women. Research in Nursing and Health. 2001;24:410–422. doi: 10.1002/nur.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Nyamathi AM, Stein JA. Assessing the impact of HIV risk reduction counseling in impoverished African American women: A structural equations approach. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1997;9:253–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.O'Hara P, Messick B, Fichtner RR, Parris D. A peer-led AIDS prevention program for students in an alternative school. Journal of School Health. 1996;66:176–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1996.tb06271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.O'Leary A, Ambrose TK, Raffaelli M, Mailbach E, Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB, III, et al. Effects of an HIV risk reduction project on sexual risk behavior of low-income STD patients. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1998;10:483–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Orr D, Langefeld CD, Katz BP, Caine VA. Behavioral intervention to increase condom use among high-risk female adolescents. Journal of Pediatrics. 1996;128:288–295. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Otto-Salaj LL, Kelly JA, Stevenson LY, Hoffmann R, Kalichman SC. Outcomes of a randomized small-group HIV prevention intervention trial for people with serious mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal. 2001;37:123–144. doi: 10.1023/a:1002709715201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Ozer EJ, Weinstein RS, Maslack C. Adolescent AIDS prevention in context: Impact of peer educator qualities and classroom environments on intervention efficacy. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1997;25:289–323. doi: 10.1023/a:1024624610117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Peterson JL, Coates TJ, Catania J, Hauck WW, Acree M, Daigle D, et al. Education of an HIV risk reduction intervention among African-American homosexual and bisexual men. AIDS. 1996;10:319–325. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199603000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Picciano JF, Roffman RA, Kalichman SC, Rutledge SE, Berghuis JP. A telephone based brief intervention using motivational enhancement to facilitate HIV risk reduction among MSM: A pilot study. AIDS and Behavior. 2001;5:251–262. [Google Scholar]

- *.Ploem C, Byers S. The effects of two AIDS risk-reduction interventions on heterosexual college women's AIDS-related knowledge, attitudes and condom use. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality. 1997;9:1–23. doi: 10.1300/j056v09n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Ponton LE, DiClemente RJ, McKenna S. AIDS education and prevention program for hospitalized adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30:729–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Quirk ME, Godkin MA, Schwenzfeier E. Evaluation of two AIDS prevention interventions for inner-city adolescent and young adult women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1993;9:21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Ragon BM, Kittleson MJ, St. Pierre RW. The effect of a single affective HIV/AIDS educational program on college students' knowledge and attitudes. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1995;7:221–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Reeder GD, Pryor JB, Harsh L. Activity and similarity in safer sex workshops led by peer educators. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1997;9:77–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Rhodes F, Wolitski R. Affect of instructional videotapes on AIDS knowledge and attitudes. College Health. 1989;37:266–271. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1989.9937493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Roffman RA, Stephens RS, Curtin L, Gordon JR, Craver JN, Stern M, et al. Relapse prevention as an interventive model for HIV risk reduction in gay and bisexual men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1998;10:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Rosser BRS, Bockting WO, Rugg DL, Robinson BBE, Ross MW, Coleman E. A randomized controlled intervention trial of a sexual health approach to long term HIV risk reduction for men who have sex with men: Effects of the intervention on unsafe sexual behavior. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2002;14:59–71. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.4.59.23885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Koopman C, Haignere C, Davies M. Reducing HIV sexual risk behaviors among runaway adolescents. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1991;266:1237–1242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Lee MB, Murphy DA, Futterman D, Duan N, Birnbaum JM, et al. Efficacy of a preventive intervention for youth living with HIV. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:400–405. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.3.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Murphy DA, Fernández MI, Srinivasan S. A brief HIV intervention for adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68:553–563. doi: 10.1037/h0080364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Ruder AM, Flam R, Flatto D, Curran AS. AIDS education: Evaluation of school and worksite based presentations. New York State Journal of Medicine. 1990;90:129–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Schinke SP, Gordon AN. Self-instruction to prevent HIV infections among African-American and Hispanic-American adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:432–436. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.4.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Scollay PA, Doucett M, Perry M, Winterbottom B. AIDS education of college students: The effect of an HIV-positive lecturer. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1992;4:160–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Shrier LA, Ancheta R, Goodman E, Chiou VM, Lyden MR, Emans SJ. Randomized controlled trial of a safer sex intervention for high-risk adolescent girls. Archive of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2001;155:73–79. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Shulkin JJ, Mayer JA, Wessel LG, de Moor C, Elder JP, Franzini LR. Effects of a peer-led AIDS intervention with university students. College Health. 1991;40:75–79. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1991.9936259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Siegel DM, Aten MJ, Roghmann KJ, Enaharo M. Early effects of a school-based human immunodeficiency virus infection and sexual risk prevention intervention. Archive of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 1998;152:961–970. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.10.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Siegel DM, DiClemente R, Durbin M, Krasnorsky F, Saliba P. Change in junior high school students' aid-related knowledge, misconceptions, attitudes, and HIV-preventive behaviors: Effects of a school-based intervention. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1995;7:534–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Sikkema KJ, Kelly JA, Winett RA, Solomon LJ, Cargill VA, Mercer MB. Outcomes of a randomized community level HIV prevention intervention for women living in 18 low-income housing developments. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:57–63. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Sikkema KJ, Winett RA, Lombard DN. Development and evaluation of an HIV-risk reduction program for female college students. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1995;7:145–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Slap GB, Plotkin SL, Najma K, Michelman DF, Forke C. A human immunodeficiency virus peer education program for adolescent females. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1992;12:434–441. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(91)90020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Smith MU, Dane FC, Archer ME, Devereux RS, Katner HP. Students together against negative decisions (STAND): Evaluation of a school-based sexual risk-reduction intervention in the rural south. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12:49–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Smith MU, Katner HP. Quasi-experimental evaluation of three AIDS prevention activities for maintaining knowledge, improving attitudes, and changing risk behaviors of high risk school seniors. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1995;7:391–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.St. Lawrence JS, Crosby RA, Basfield T, O'Bannon RE., III Reducing STD and HIV risk behavior of substance-dependent adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:1010–1021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.St. Lawrence JS, Jefferson KW, Alleyne E, Brasfield TL. Comparison of education versus behavioral skills training interventions in lowering sexual HIV-risk of substance-dependent adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:154–157. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.1.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.St. Lawrence JS, Wilson TE, Eldridge GD, Brasfield TL, O'Bannon RE., III Community-based interventions to reduce low income, African American women's risk of sexually transmitted diseases: A randomized controlled trial of three theoretical models. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29:937–964. doi: 10.1023/A:1012919700096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Stall RD, Paul JP, Barrett DC, Crosby GM, Bein E. An outcome evaluation to measure changes in sexual risk-taking among gay men undergoing substance use disorder treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:837–844. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Stanton BF, Li X, Kahihuala J, Fitzgerald AM, Neumbo S, Kanduuombe G, et al. Increased protected sex and abstinence among Namibian youth following an HIV risk-reduction intervention: A randomized longitudinal study. AIDS. 1998;12:2473–2480. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199818000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Stanton BF, Li X, Ricardo I, Galbraith J, Feigelman S, Kaljee L. A randomized, controlled effectiveness trial of an AIDS prevention program for low-income African-American youths. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 1996;150:363–372. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290029004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Sterk CE, Theall KP, Elifson KW. Effectiveness of a risk reduction intervention among African American women who use crack cocaine. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2003;15:15–32. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.15.23843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Turner JC, Garrison CZ, Korpita E, Waller J, Addy C, Mohn LA. Promoting responsible sexual behavior through a college freshman seminar. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1994;6:266–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Valdiserri RO, Lyter DW, Kingsley LA, Leviton LC, Schofield JW, Huggins J, et al. The effect of group education on improving attitudes about AIDS risk reduction. New York State Journal of Medicine. 1987;87:272–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Valente T, Bharath U. An evaluation of the use of drama to communicate HIV/AIDS information. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1999;11:203–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Walter HJ, Vaughan RP. AIDS risk reduction among a multiethnic sample of urban high school students. JAMA. 1993;270:725–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Waters JA, Morgen K, Kuttner P, Schmitt B. The “Guiding Adolescents to Prevention” program: Reducing HIV transmission and drug use in youth in a detention center. Crisis Intervention. 1996;3:85–96. [Google Scholar]

- *.Week K, Levy SR, Zhu C, Perhats C, Handler A, Flay BR. Impact of a school-based AIDS prevention program on young adolescents' self-efficacy skills. Health Education Research. 1995;10:329–344. [Google Scholar]