Abstract

This unit describes a technique for the direct and quantitative measurement of the capacity of peptide ligands to bind Class I and Class II MHC molecules. The binding of a peptide of interest to MHC is assessed based on its ability to inhibit the binding of a radiolabeled probe peptide to purified MHC molecules. This unit includes protocols for the purification of Class I and Class II MHC molecules by affinity chromatography, and for the radiolabeling of peptides using the chloramine T method. An alternate protocol describes alterations in the basic protocol that are necessary when performing direct binding assays, which are required for (1) selecting appropriate high-affinity, assay-specific, radiolabeled ligands, and (2) determining the amount of MHC necessary to yield assays with the highest sensitivity. After a predetermined incubation period, dependent upon the allele under examination, the bound and unbound radiolabeled species are separated, and their relative amounts are determined. Three methods for separation are described, two utilizing size-exclusion gel-filtration chromatography and a third using monoclonal antibody capture of MHC. Data analysis for each method is also explained.

Keywords: MHC class I, MHC class II, T cell epitope, peptide ligand, binding affinity, CTL, epitope recognition

INTRODUCTION

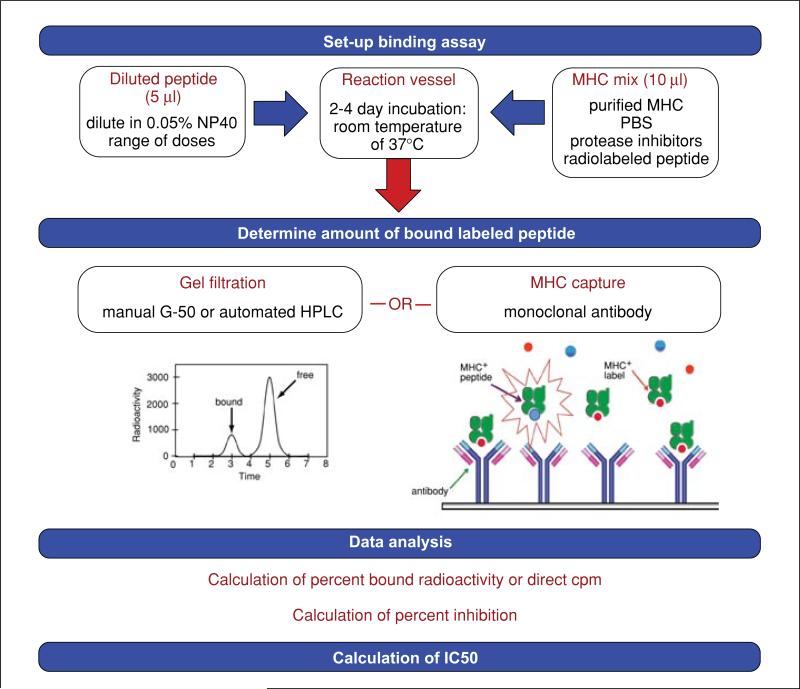

This unit describes a technique for the direct and quantitative measurement of the capacity of peptide ligands to bind Class I and Class II MHC molecules. The binding of a peptide of interest to MHC is assessed based on its ability to inhibit the binding of a radiolabeled probe peptide to MHC molecules. MHC molecules are solubilized with detergents and purified by affinity chromatography. Purified MHC is then incubated with the inhibitor peptide and a high-affinity binding radiolabeled probe peptide, in the presence of a cocktail of protease inhibitors. Incubation is typically for 2 days at room temperature, although some alleles require incubation at higher temperatures (i.e., 37°C) and longer time periods. At the end of the incubation period, MHC-peptide complexes are separated from unbound radiolabeled peptide by (a) an antibody-capture phase or (b) size-exclusion gel-filtration chromatography. The percent of bound radioactivity is then determined. The binding affinity of a particular peptide for an MHC molecule may be determined by co-incubation of various doses of unlabeled competitor peptide with the MHC molecules and labeled probe peptide. The concentration of unlabeled peptide required to inhibit the binding of the labeled peptide by 50% (IC50) can be determined by plotting dose versus % inhibition. Under conditions where [label] < [MHC] and IC50 ≥ [MHC], the measured IC50 values are reasonable approximations of true Kd values (Cheng and Prusoff, 1973; Gulukota et al., 1997). To date, the methods described below have been utilized to establish over 130 binding assays for Class I and Class II molecules of human, mouse, macaque (Indian and Chinese Rhesus macaque, and pig-tailed macaque), chimpanzee, and gorilla origin (Tables 18.3.1, 18.3.2, and 18.3.3). Note that UNIT 18.4 describes an alternate method for measuring peptide-MHC interactions using a spin column gel filtration assay.

Table 18.3.1.

Human, Non-Human Primate, and Murine Class I MHC-Peptide Binding Assays Established Using Purified MHC Molecules and Radiolabeled Ligands

| Radiolabeled peptidea |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | Allele | Preferred cell line | Sequence | Source |

| Human | A*0101 | STEINLIN | YTAVVPLVY | H. sapiens (J chain 102) |

| A*0201 | JY | FLPSDYFPSV | HBV (core 18) | |

| A*0202 | M7 | GLYSSTVPV | HBV (Pol 61) | |

| A*0203 | FUN | FVNYNFTLV | T. cruzi (trans-sialidase) | |

| A*0205 | DAH | FLPSDYFPSV | HBV (core 18) | |

| A*0206 | CLA | FLPSDYFPSV | HBV (core 18) | |

| A*0207 | AP | FLPSDYFPSV | HBV (core 18) | |

| A*0217 | AMALA | FLPSDYFPSV | HBV (core 18) | |

| A*0301 | GM3107 | YVFPVIFSK | H. sapiens (MAGE3 138) | |

| A*1101 | BVR | YVFPVIFSK | H. sapiens (MAGE3 138) | |

| A*2301 | WT51 | AYIDNYNKF | Non-natural (A24 consensus) | |

| A*2402 | KT3 | AYIDNYNKF | Non-natural (A24 consensus) | |

| A*2601 | QBL | ETFGFEIQSY | H. sapiens (leucine zipper 51) | |

| A*2902 | SWEIG | YTAVVPLVY | H. sapiens (J chain 102) | |

| A*3001 | RSH or S Buus | KTKDYVNGL | H. sapiens (F actin 235) | |

| A*3002 | DUCAF | RISGVDRYY | H. sapiens (NADH 53) | |

| A*3101 | SPACH | YVFPVIFSR | H. sapiens (MAGE3 138) | |

| A*3201 | WT47 | RILHNFAYSL | H. sapiens (Her2/neu 434) | |

| A*3301 | LWAGS | YVFPVIFSR | H. sapiens (MAGE3 138) | |

| A*6601 | TEM | YVFPVIFSR | H. sapiens (MAGE3 138) | |

| A*6801 | CIR | YVFPVIFSK | H. sapiens (MAGE3 138) | |

| A*6802 | AMAI | YVIKVSARV | H. sapiens (MAGE1 282) | |

| A*7401 | Pure Protein | YVFPVIFSR | H. sapiens (MAGE3 138) | |

| B*0702 | GM3107 | APRTLVYLL | H. sapiens (A2 signal seq 5) | |

| B*0801 | STEINLIN | FLRGRAYGI | HSV (EBNA 3 nuc) | |

| B*1402 | HO301 | DAYRRIHSL | H. sapiens (BRCA1/2) | |

| B*1501 | SPACH | AQIDNYNKF | Non-natural (A24 consensus) | |

| B*1503 | S Buus | YQAVVPLVY | H. sapiens (J chain 102) | |

| B*1801 | DUCAF | SEIDLILGY | H. sapiens (unknown) | |

| B*2705 | LG2 | FRYNGLIHR | H. sapiens (60s rL28 38) | |

| B*3501 | CIR | FPFKYAAAF | Non-natural (B35 consensus) | |

| B*3503 | KOSE | FPFKYAAAF | Non-natural (B35 consensus) | |

| B*3508 | TISI | FPFKYAAAF | Non-natural (B35 consensus) | |

| B*3701 | KAS011 | AEFKYIAAV | Non-natural (B4006 consensus) | |

| B*3801 | TEM | YHIPGDTLF | Variola virus (RNA-hel 346) | |

| B*4001 | 2F7 | YEFLQPILL | H. sapiens (XP090897) | |

| B*4002 | SWEIG | YEFLQPILL | H. sapiens (XP090897) | |

| B*4201 | RSH | FPFKYAAAF | Non-natural (B35 consensus) | |

| B*4402 | WT47 | SEIDLILGY | H. sapiens (unknown) | |

| B*4403 | PITOUT | SEIDLILGY | H. sapiens (unknown) | |

| B*4501 | OMW | AEFKYIAAV | Non-natural (B4006 consensus) | |

| B*5101 | KAS116 | FPYSTFPII | Non-natural (B51 consensus) | |

| B*5201 | HARA | YGFSDPLTF | Unknown (Mamu B39 ligand) | |

| B*5301 | AMAI | FPFKYAAAF | Non-natural (B35 consensus) | |

| B*5401 | KT3 | FPFKYAAAF | Non-natural (B35 consensus) | |

| B*5701 | DBB | KAGQYVTIW | H. sapiens (lamin C 490) | |

| B*5801 | AP | ISDSNPYLTQW | H. sapiens (E46 407) | |

| B*5802 | 35841 | GSVNVVYTF | H. sapiens (glucose trans 5 322) | |

| C*0401 | CIR | QYDDAVYKL | Non-natural (consensus) | |

| C*0602 | 721.221b | YRHDGGNVL | Rat (Ig variable 80) | |

| C*0702 | 721.221 | YRHDGGNVL | Rat (Ig variable 80) | |

| Macaque | Mamu A*01 | 721.221 | ATPYDINQML | SIV (Gag 181) |

| Mamu A*02 | 721.221 | YTAVVPLVY | H. sapiens (J chain 102) | |

| Mamu A*07 | 721.221 | YHSNVKEL | SIV (Pol 782) | |

| Mamu A*11 | 721.221 | GDYKLVEI | SIV (Env 497) | |

| Mamu A1*2201 | 721.221 | YVADALAAF | Non-natural (Mamu A26 consensus) | |

| Mamu A1*2601 | 721.221 | YLPTQQDVL | Non-natural (Mamu A26 consensus) | |

| Mamu B*01 | 721.221 | SDYLELDTI | Macaque (tumor reject gp96 235) | |

| Mamu B*03 | 721.221 | RRAARAEYL | Non-natural (consensus) | |

| Mamu B*08 | 721.221 | RRDYRRGL | Non-natural (Vif 172) | |

| Mamu B*17 | 721.221 | IRFPKTFGY | SIV (Nef 165) | |

| Mamu B*48 | 721.221 | AQFSPQYL | Non-natural | |

| Mamu B*52 | 721.221 | VGNVYVKF | H. sapiens (U2 RNA factor 1) | |

| Mamu B*8301 | 721.221 | KSINKVYGK | Vaccinia (B13R 64) | |

| Mane A*0301 | 721.221 | DHQAAFQYI | SIV (Gag analog 176) | |

| Mane A*0302 | 721.221 | DHQAAFQYI | SIV (Gag analog 176) | |

| Chimpanzee | Patr A*0101 | 721.221 | KVFPYALINK | Non-natural (A3 consensus) |

| Patr A*03 | 721.221 | KVFPYALINK | Non-natural (A3 consensus) | |

| Patr A*0401 | 721.221 | KFYGPFVDR | SARS (Orf 1ab 3420) | |

| Patr A*0701 | 721.221 | AYIDNYNKV | Non-natural (A24CON1) | |

| Patr A*0901 | 721.221 | AYISSEATTPV | HCV (NS4 1963) | |

| Patr B*0101 | 721.221 | YTGDFDSVI | HCV (NS3 1444) | |

| Patr B*1301 | 721.221 | FPFKYAAAF | Non-natural (B35 consensus) | |

| Patr B*2401 | 721.221 | SDYLELDTI | Macaque (tumor reject gp96 235) | |

| Mouse | Db | EL4 | SGPSNTYPEI | Adenovirus (EA1) |

| Dd | P815 | RGPYRAFVTI | HIV (Env 18) | |

| Kb | EL4 | RGYVFQGL | VSV (NP 52) | |

| Kd | P815 | KFNPMFTYI | Non-natural | |

| Kk | CH27 | SEAAYAKKI | Non-natural (Kk consensus) | |

| Ld | P815 | IPQSLDSYWTSL | HBV (Env 28) | |

All Class I assays are performed at pH 7.0, at room temperature, with a 48-hr incubation. With the exception of B*4402 and B*4403, which are captured with the B123.2 antibody, all primate Class I assays are captured for 3 hr with W6/32. Mouse Class I assays are captured using the antibodies as listed in Table 18.3.5.

721.221 refers to corresponding single allele transfected cell lines.

Table 18.3.2.

Human, Non-Human Primate, and Murine Class II MHC-Peptide Binding Assays Established Using Purified MHC Molecules and Radiolabeled Ligands: Cell Lines and Ligands for Class II Assays

| Radiolabeled peptide |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | Allele(s) | Preferred cell line | Sequence | Source |

| Human | DPB1*0101 | VAVY | EKKYFAATQFEPLAA | H. sapiens (aminopeptidase 285) |

| DPB1*0201 | WT51 | KYFAATQFEPLAARL | H. sapiens (aminopeptidase 287) | |

| DPB1*0301 | COX | AFKVAATAANAAPAY | Non-natural (Phl p 5 analog 196) | |

| DPB1*0401 | PITOUT | KYFAATQFEPLAARL | H. sapiens (aminopeptidase 287) | |

| DPB1*0402 | AMAI | EKKYFAATQFEPLAA | H. sapiens (aminopeptidase 285) | |

| DPB1*0501 | HO301 | IGRIAETILGYNPSA | H. sapiens (chimeric protein) | |

| DPB1*1401 | KAS011 | AFKVAATAANAAPANY | Non-natural (Phl p 5 analog 196) | |

| DPB1*2001 | EBV-D8 | AFKVAATAANAAPAY | Non-natural (Phl p 5 analog 196) | |

| DQA1*0501/B1*0201 | VAVY | KPLLIIAEDVEGEY | M. tuberculosis (65 kDa hsp 32) | |

| DQA1*0201/B1*0202 | PITOUT | EEDIEIIPIQEEEY | H. sapiens (CD20 249) | |

| DQA1*0301/B1*0301 | PF | YAHAAHAAHAAHAAHAA | Non-natural (ROIV reiterative) | |

| DQA1*0501/B1*0301 | HERLUF | YAHAAHAAHAAHAAHAA | Non-natural (ROIV reiterative) | |

| DQA1*0505/B1*0301 | SWEIG | YAHAAHAAHAAHAAHAA | Non-natural (ROIV reiterative) | |

| DQA1*0301/B1*0302 | PRIESS | EEDIEIIPIQEEEY | H. sapiens (CD20 249) | |

| DQA1*0401/B1*0402 | OLL | EEDIEIIPIQEEEY | H. sapiens (CD20 249) | |

| DQA1*0101/B1*0501 | LG2 | AAHSAAFEDLRVSSY | Influenza (nucleoprotein 335) | |

| DQA1*0102/B1*0502 | KAS011 | AAHSAAFEDLRVSSY | Influenza (nucleoprotein 335) | |

| DQA1*0104/B1*0503 | TEM | AAHSAAFEDLRVSSY | Influenza (nucleoprotein 335) | |

| DQA1*0102/B1*0602 | MGAR | AAATAGTTVYGAFAA | Non-natural (GAD65 analog 334) | |

| DQA1*0103/B1*0603 | OMW | AAATAGTTVYGAFAA | Non-natural (GAD65 analog 334) | |

| DRB1*0101 | LG2 | YPKYVKQNTLKLAT | Influenza (HA 307) | |

| DRB1*0301 | MAT | YARIRRDGCLLRLVD | H. sapiens (telomerase 854) | |

| DRB1*0401 | PRIESS | PVVHFFKNIVTPRTPPY | H. sapiens (MBP 85) | |

| DRB1*0404 | BIN40 | PVVHFFKNIVTPRTPPY | H. sapiens (MBP 85) | |

| DRB1*0405 | KT3 | PVVHFFKNIVTPRTPPY | H. sapiens (MBP 85) | |

| DRB1*0701 | PITOUT | YATFFIKANSKFIGITE | C. tetani (tetanus toxin 828) | |

| DRB1*0802 | OLL | EVFFQRLGIASGRARY | H. sapiens (PSA 522) | |

| DRB1*0901 | HID | TLSVTFIGAAPLILSY | H. sapiens (PSA 9) | |

| DRB1*1001 | WTAIL | AFKVAATAANAAPAY | Non-natural (Phl p 5 analog 196) | |

| DRB1*1101 | SWEIG | YATFFIKANSKFIGITE | C. tetani (tetanus toxin 830) | |

| DRB1*1201 | HERLUF | EALIHQLKINPYVLS | H. sapiens (unknown) | |

| DRB1*1302 | H0301 | QYIKANAKFIGITE | C. tetani (tetanus toxin 830) | |

| DRB1*1501 | L466.1 | PVVHFFKNIVTPRTPPY | H. sapiens (MBP 78) | |

| DRB1*1602 | RML | EALIHQLKINPYVLS | H. sapiens (unknown) | |

| DRB3*0101 | MAT | YTVDFSLDPTFTIETT | HCV (polyprotein 1460) | |

| DRB3*0202 | HERLUF | VIDWLVSNQSVRNRQEGLY | Non-natural | |

| DRB4*0101 | L257.6 | QVPLVQQQQFLGQQQP | T. aestivum (alpha gliadin 41) | |

| DRB5*0101 | GM3107 | YATFFIKANSKFIGITE | C. tetani (tetanus toxin 828) | |

| Macaque | Mamu DRBw*20101 | RM3 | ELYKYKVVKIEPLGV | HIV (gp120 482) |

| Mamu DRB1*0406 | RM3 | THGIRPVVSTQLLLY | HIV (gp120 analog 248) | |

| Mouse | IAb | LB27.4 | YAHAAHAAHAAHAAHAA | Non-natural (ROIV reiterative) |

| IAd | A20/ LB27.4 | YAHAAHAAHAAHAAHAA | Non-natural (ROIV reiterative) | |

| IAk | CH12/CH27 | YNTDGSTDYGILQINSR | G. gallus (HEL 46) | |

| IAs | LS102.9 | YAHAAHAAHAAHAAHAA | Non-natural (ROIV reiterative) | |

| IAu | 91.7 | YAHAAHAAHAAHAAHAA | Non-natural (ROIV reiterative) | |

| IEd | A20/ LB27.4 | YRKILRQRKIDRLID | HIV (Vpu 30) | |

| IEk | CH12 | YLEDARRLKAIYEKKK | Bacteriophage (lambda rep. 12) | |

Table 18.3.3.

Human, Non-Human Primate, and Murine Class II MHC-Peptide Binding Assays Established Using Purified MHC Molecules and Radiolabeled Ligands: Conditions for Class II Assays and MHC Capture Steps

| Assay conditions |

Capture conditions |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | Allele(s) | pH | NEM | Detergenta | Temp. | Incubation (hr) | Antibody | Time (hr) |

| Human | DPB1*0101 | 5.5 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 72 | B7/21 | 24 |

| DPB1*0201 | 5.5 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | B7/21 | 24 | |

| DPB1*0301 | 7 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | 37°C | 72 | B7/21 | 24 | |

| DPB1*0401 | 7 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | B7/21 | 24 | |

| DPB1*0402 | 7 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | 37°C | 72 | B7/21 | 24 | |

| DPB1*0501 | 5.5 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | 37°C | 72 | B7/21 | 24 | |

| DPB1*1401 | 7 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | 37°C | 72 | B7/21 | 24 | |

| DPB1*2001 | 7 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 72 | B7/21 | 24 | |

| DQA1*0501/B1*0201 | 5.5 | No | 0.82%Pluronic | 37°C | 72 | HB180 | 24 | |

| DQA1*0201/B1*0202 | 5 | No | 0.82% Pluronic | 37°C | 72 | HB180 | 24 | |

| DQA1*0301/B1*0301 | 7 | Yes | 0.82% Pluronic | RT | 72 | HB180 | 24 | |

| DQA1*0501/B1*0301 | 7 | Yes | 0.82% Pluronic | 37°C | 72 | HB180 | 24 | |

| DQA1*0505/B1*0301 | 7 | Yes | 0.82% Pluronic | 37°C | 72 | HB180 | 24 | |

| DQA1*0301/B1*0302 | 5 | Yes | 0.82% Pluronic | 37°C | 48 | HB180 | 24 | |

| DQA1*0401/B1*0402 | 5 | No | 0.82% Pluronic | 37°C | 72 | HB180 | 24 | |

| DQA1*0101/B1*0501 | 7 | No | 0.82% Pluronic | 37°C | 72 | HB180 | 24 | |

| DQA1*0102/B1*0502 | 7 | No | 0.82% Pluronic | 37°C | 72 | HB180 | 24 | |

| DQA1*0104/B1*0503 | 7 | No | 0.82% Pluronic | 37°C | 72 | HB180 | 24 | |

| DQA1*0102/B1*0602 | 5.5 | No | 0.82% Pluronic | 37°C | 72 | HB180 | 24 | |

| DQA1*0103/B1*0603 | 4.5 | No | 0.82% Pluronic | 37°C | 72 | HB180 | 24 | |

| DRB1*0101 | 7 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | LB3.1 | 3 | |

| DRB1*0301 | 4.5 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | LB3.1 | 3 | |

| DRB1*0401 | 7 | No | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | LB3.1 | 3 | |

| DRB1*0404 | 7 | No | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | LB3.1 | 3 | |

| DRB1*0405 | 7 | No | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | LB3.1 | 3 | |

| DRB1*0701 | 7 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | LB3.1 | 3 | |

| DRB1*0802 | 7 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | LB3.1 | 3 | |

| DRB1*0901 | 7 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | LB3.1 | 3 | |

| DRB1*1001 | 7 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | LB3.1 | 3 | |

| DRB1*1101 | 7 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | LB3.1 | 3 | |

| DRB1*1201 | 7 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | 37°C | 48 | LB3.1 | 3 | |

| DRB1*1302 | 7 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | LB3.1 | 3 | |

| DRB1*1501 | 7 | No | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | LB3.1 | 3 | |

| DRB1*1602 | 7 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | LB3.1 | 3 | |

| DRB3*0101 | 7 | No | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | LB3.1 | 3 | |

| DRB3*0202 | 7 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | LB3.1 | 3 | |

| DRB4*0101 | 5 | No | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | LB3.1 | 3 | |

| DRB5*0101 | 7 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | LB3.1 | 3 | |

| Macaque | Mamu DRBw*20101 | 7 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | LB3.1 | 3 |

| Mamu DRB1*0406 | 5.5 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | LB3.1 | 3 | |

| Mouse | IAb | 7 | Yes | Digitonin 10% | RT | 48 | Y3JP | 3 |

| IAd | 7 | Yes | Digitonin 10% | RT | 48 | MKD6 | 3 | |

| IAk | 7 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | 10.3.6 | 3 | |

| IAs | 7 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | Y3JP | 3 | |

| IAu | 7 | Yes | 0.82% Pluronic | RT | 48 | Y3JP | 3 | |

| IEd | 4.5 | No | 0.82% NP40 | RT | 48 | 14.4.4 | 3 | |

| IEk | 5 | Yes | 1.6% NP40 | RT | 48 | 14.4.4 | 3 | |

Indicates the detergent utilized in the protease inhibitor cocktail, as well as added as a 1-μl spike to the reaction mix.

Because some residual proteolytic activity is evident in most preparations of purified MHC, the use of a cocktail of protease inhibitors in each assay is extremely critical. Many protease inhibitors are light-sensitive and very labile, so it is also very important that the cocktail be prepared fresh and used immediately (i.e., within minutes). Failure to use or prepare the protease inhibitor cocktail properly can result in assays with poor specificity and low sensitivity, and can give irreproducible results.

The establishment of an MHC/peptide binding assay, and its subsequent use in determining the MHC binding capacities of peptide ligands, requires sufficient stocks of purified MHC and both labeled and unlabeled peptides. Accordingly, this unit includes protocols for the purification of Class I and Class II MHC molecules by affinity chromatography (see Support Protocol 1) and for the radiolabeling of peptides using the chloramine T method (see Support Protocol 2). Peptides may be synthesized by a number of alternative methods described elsewhere (e.g., UNIT 9.1). The Alternate Protocol describes alterations in the Basic Protocol that are necessary when performing direct binding assays, which are required for (1) selecting appropriate high-affinity, assay-specific, radiolabeled ligands and (2) determining the amount of MHC necessary to yield assays with the highest sensitivity.

After a 2- to 3-day incubation, the bound and unbound radiolabeled species are separated, and their relative amounts are determined. Methods for separation by size-exclusion gelfiltration chromatography or antibody-based MHC capture are described in respective support protocols (see Support Protocols 3 and 4), along with data analysis. Support Protocol 5 describes the preparation of immunoaffinity columns for MHC purification.

DETERMINATION OF PEPTIDE BINDING TO AFFINITY-PURIFIED CLASS I AND CLASS II MHC MOLECULES

This protocol describes an assay in which the MHC binding capacity of peptides is determined by their ability to inhibit the binding of a high-affinity radiolabeled probe peptide to a specific MHC molecule. This assay is useful for screening synthetic peptides, or other materials, and the procedure can be used, with little variation, for either Class I or Class II MHC purified from a number of different sources (e.g., from human, mouse, or transfected Drosophila cell lines). The Alternate Protocol describes the minor changes required for conducting direct binding assays, which are used to establish binding assay conditions or perform MHC titrations. A flow chart schematizing the assay is presented in Figure 18.3.1.

Figure 18.3.1.

A schematic overview of the steps involved in performing an MHC-peptide binding assay.

With a few exceptions, Class I and Class II assays are largely performed in the same manner. These exceptions include (1) that N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) is not used in the protease inhibitor cocktail for Class I assays and (2) that human β2-microglobulin is included in Class I assays. These differences are also noted where appropriate in the protocol. Throughout the protocol we have indicated vendors for various reagents. These listings are by way of example, and other suppliers of comparable material may be utilized.

Materials

Inhibitor peptides

Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; APPENDIX 2A), pH 7.2 (Invitrogen)

Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)

0.05% (v/v) Nonidet P-40 (NP-40; Fluka)/PBS, pH 7.2

Citrate/phosphate buffer (optional; see recipe)

MHC (see Support Protocol 1 and Alternate Protocol for preparation and titration, respectively)

Protease inhibitor cocktail (prepare at step indicated, not in advance; see recipe)

1 to 3 μM human β2-microglobulin (Class I only; Scripps Laboratories, cat. no. M0114)

1.6% (v/v) NP-40/PBS: PBS, pH 7.2 (Class II only)

0.82% Pluronic in PBS, pH 7.2

10% digitonin in water

Radiolabeled peptide (see Support Protocol 2)

Reaction vessels (e.g., 96-well polypropylene round-bottom plates from Costar, or 12 × 75–mm culture tubes)

Mylar film plate sealer with adhesive backing (ICN Biomedicals) or Costar storage mat III (Corning)

Additional reagents and equipment for gel filtration or MHC capture and analysis (see Support Protocols 3 and 4)

Prepare peptides

- Solubilize lyophilized inhibitor peptides in water, PBS, pH 7.2, or 100% DMSO. Serially dilute peptides to the desired concentrations in 0.05% (v/v) NP-40/PBS.While peptide solubility and stability are optimal in DMSO, MHC assays do not appear to tolerate more than 1% DMSO (Class I) or 5% DMSO (Class II) in the final assay. Therefore, DMSO stocks should be concentrated enough that the DMSO is sufficiently diluted over the range of doses tested. For most applications, 10 to 20 mg/ml is suitable for peptide stocks.

- Load 5 μl of each peptide dose to be tested into a reaction vessel using a micropipettor. For positive (i.e., no inhibitor peptide) and negative (no MHC) controls, load 5 μl 0.05% (v/v) NP-40/PBS in place of inhibitor peptide.Peptides are tested in a final assay volume of 15 μl, which contains inhibitor peptide, MHC, labeled peptide, and a protease inhibitor cocktail. If separations are to be performed in an automated gel filtration system (see Support Protocol 3) or capture-based system (see Support Protocol 4), the reaction is performed in 96-well polypropylene plates or other format as required by the specific system configuration. For manual separation by gel filtration, the reaction may be performed in 12 × 75–mm culture tubes, snap-cap vials, or other similar vessels, depending on the configuration of the separation scheme and radiodetection method utilized.It is recommended that a full titration of a standard reference peptide (typically unlabeled probe peptide) also be included. Examples of high-affinity standard peptides for various Class I and Class II assays may be found in Tables 18.3.1, 18.3.2, and 18.3.3.

Prepare MHC/labeled peptide reaction mix

-

3Prepare a mix of the remaining ingredients. Prepare sufficient reaction mix for all data points, scaling the ingredients for a total volume of 10 μl per well/data point. Take care to add ingredients in the following order, and to prepare the protease inhibitor cocktail immediately before adding MHC to PBS.

- PBS, pH 7.2: Enough to bring volume to 10 μl (for experiments to be performed at a pH other than 7.0, substitute 6 μl PBS with 6 μl citrate/phosphate buffer at a pH 0.5 points below the desired final pH in the mix).

- MHC: Enough to yield a signal-to-noise ratio (S/N; maximum bound counts/background cpm) of at least 3, but ideally 5 to 10, in the capture-based system, or ~15% binding of labeled peptide, as determined by previous titration (see Alternate Protocol), in the gel-filtration system.Support Protocol 1 describes the purification of MHC from cell lysates. However, the assay described here is fully amenable to MHC purified from other sources, such as the recombinant solubilized MHC produced in a hollow-fiber bioreactor, as described by Hildebrand (Buchli et al., 2004, 2005), or the E. coli expression system described by Buus (Ferre et al., 2003; Justesen et al., 2009; Harndahl et al., 2011).

- 2 μl protease inhibitor cocktail.

- 1 to 3 μl of 1 μM human β2-microglobulin (Class I assays only; in Class II this spike is replaced with 1.6% (v/v) NP-40/PBS, 0.82% Pluronic, or 10% digitonin; see Table 18.3.3).

- Radiolabeled peptide: Sufficient amount to give ~40,000 counts per well in the gel-filtration system, or ~8500 cpm in the capture system for Class I, and 15,000 for Class II.An example of a mix “recipe” is given in Table 18.3.4. Mix proportions should be calculated prior to beginning an assay setup. Note that the proportions of MHC, radiolabeled peptide, and PBS will vary for each assay, depending upon the activity of the MHC preparation and specific activity of the radiolabeled peptide.A small amount of mix is typically irretrievable. Therefore, it is prudent to prepare a small (10%) excess of mix to avoid running short.Protease inhibitor cocktail must be used immediately, ideally within 2 min of preparation. Therefore, it should be prepared when indicated above, and the reaction mix should be added to wells (step 4) immediately upon its completion.Examples of assay-specific peptides that may be radiolabeled are given in Tables 18.3.1, 18.3.2, 18.3.3.

Table 18.3.4.

Sample Reaction Mix Recipe

| Ingredient | Vol (ml) per 10 ml | Vol (ml) for 100 samples | Vol (ml) with 10% excess |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBS | 5.5 | 550 | 605 |

| MHC | 1.0 | 100 | 110 |

| Protease inhibitor cocktail | 2.0 | 200 | 220 |

| β2-microglobulin | 1.0 | 100 | 110 |

| Labeled peptide | 0.5 | 50 | 55 |

| Total | 10 | 1000 | 1100 |

Perform binding reaction

-

4Immediately add 10 μl reaction mix to all but the negative control well(s). For negative controls, add 2 μl protease inhibitor cocktail, 1 μl of 1 μM human β2-microglobulin (in Class I assays only), the appropriate amount of radiolabeled peptide, and enough PBS, pH 7.2, to bring the final volume to 15 μl.The mix may be loaded from a reagent reservoir by multichannel pipettor if 96-well plates are used.

-

5Seal the reaction vessel to prevent evaporation. Use mylar film plate sealer or Costar mats (preferable) to seal 96-well plates; tightly seal tubes or close with stoppers.To avoid problems with evaporation in the outer wells of the plate, the mylar should be trimmed neatly along the edge of the plate, and then taped down with general-purpose laboratory tape.

-

6Incubate 2 days (for most assays) in the dark at room temperature or 37°C moist incubator (assay dependent).Kinetic studies have shown that, under the conditions described here, peptide binding to Class I, and most Class II, molecules generally begins to plateau after ~36 hr (e.g., Buus et al., 1986; Sette et al., 1992). Accordingly, all Class I, and most Class II assays are performed at pH 7, at room temperature, with a 48-hr incubation. However, some Class II assays do require longer incubation times and somewhat different conditions. Optimal conditions for each Class II assay, from our experience, are summarized in Table 18.3.3. Gel filtration or Ab capture can begin after the minimum incubation time. Once formed, peptide-MHC complexes are relatively stable, and assays can still be analyzed after a 60- to 72-hr incubation.

Separate unbound peptide from peptide-MHC complexes

-

7Separation of peptide-MHC complexes from unbound peptide can be achieved using two distinct platforms:

- Gel-filtration chromatography.Two procedures for gel-filtration separation are described (see Support Protocol 3). Other alternatives (e.g., spin columns) may be used. Data analysis is also discussed in Support Protocol 3.Alternatively, Class II assay plates may be frozen (–20°C) and analyzed at a later time.

- Capture assay utilizing monoclonal antibody-coated plates.A detailed procedure for capture-based separation is described in Support Protocol 4.

MHC PURIFICATION

Establishing a binding assay requires appropriate reagents and protocols for production and isolation of purified MHC molecules. The procedure outlined below for the affinity purification of MHC can be used for the isolation of both Class I and Class II molecules. It has been used to purify Class I and Class II MHC from mouse, human, and primate origin, as well as from transfected Drosophila cells (Buus et al., 1986, 1987, 1988; O'Sullivan et al., 1990; Sette et al., 1994). Regardless of the source, it does not appear to be necessary to specifically generate empty MHC molecules, or to copurify accessory molecules such as the molecule that catalyzes MHC-II peptide loading in endosomal/lysosomal compartments. Scatchard analysis of both Class I (Olsen et al., 1994; Sette et al., 1994) and Class II (Sette et al., 1992) assay systems indicate that, in most cases, a sufficient pool of active receptor, ranging between 2% and 20% of MHC present, is available for peptide binding.

Materials

Cell line(s): examples include Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–transformed human B cell lines; mouse B cell lymphomas or mastocytomas; singly transfected fibroblast, C1R, or 721.221 lines; or Drosophila cells (see Tables 18.3.1, 18.3.2, and 18.3.3 for specific lines that have been used). Cells should be checked for MHC expression prior to purification (or at harvest when freezing for later use).

Complete RPMI-10 (APPENDIX 2A)

Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; APPENDIX 2A), pH 7.4

Lysis buffer (see recipe), ice cold

Washing buffer: 10 mM Tris·Cl, pH 8.0 (APPENDIX 2A) with 1% Nonidet P-40 (store up to 6 months at 4°C)

0.4% (w/v) octylglucoside in PBS

Elution buffer (see recipe)

2 M Tris·Cl, pH 6.8 (APPENDIX 2A)

2.5 M glycine, pH 2.5

225-cm2 tissue culture flasks or roller bottle apparatus

Refrigerated centrifuge

0.8-μm filter

Columns (50-ml borosilicate glass containing one each of the following): inactivated Sepharose CL-4B (10-ml bed volume), protein A–Sepharose CL-4B (5-ml bed volume), and protein A-Sepharose CL-4B conjugated to the appropriate anti-MHC antibody (Table 18.3.5; 10-ml bed volume; see Support Protocol 5 for conjugation)

Centriprep-30 concentrator (Amicon)

Additional reagents and equipment for counting cells (APPENDIX 3A)

Table 18.3.5.

Monoclonal Antibodies Used in MHC Purification or Capture

| Monoclonal antibody | Specificity | Sourcea |

|---|---|---|

| M1/42 | H-2 Class I | ATCC |

| 28-14-8S | H-2 Db and Ld | ATCC |

| 34-5-8S | H-2 Dd | ATCC |

| Y3JP | H-2 IAb,IAs,IAu | Janeway et al. (1994) |

| MKD6 | H-2 IAd | ATCC |

| 10.3.6 | H-2 IAk | ATCC |

| 14.4.4 | H-2 IEd, IEk | ATCC |

| B8-24-3 | H-2 Kb | ATCC |

| Y-3 | H-2 Kb, Kk | ATCC |

| SF1-1.1.1 | H-2 Kd | ATCC |

| B123.2 | HLA B and Cb | Rebai and Malissen (1983) |

| W6/32 | HLA Class I | ATCC |

| HB180 | HLA Class II | ATCC |

| B7/21 | HLA DP | ATCC |

| IVD12 | HLA DQ | ATCC |

| SPVL3 | HLA DQ | Nepom et al. (1996) |

| LB3.1 | HLA DR | ATCC |

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection.

The B123.2 antibody will also bind some HLA A molecules. To date, we have identified HLA A*2301, A*2601, A*2902, A*3001, A*3002, A*3101, A*3201 and A*3301 as B123.2 reactive.

We would presume that corresponding subtypes are also reactive.

Prepare lysate

- Grow cell line(s) in complete RPMI-10 in 225-cm2 tissue culture flasks or, for large-scale cultures, in roller bottle apparatus. Centrifuge cells 10 min at 500 to 800 × g, 4°C, and wash three times with PBS 7.4. Count cells with a hemacytometer or Coulter counter (APPENDIX 3A), and pellet ~1010 cells.Drosophila cells require Schneider medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS and 500 μg/ml Geneticin (Invitrogen).

Lyse cells by adding 100 ml ice-cold lysis buffer (i.e., 10 ml lysis buffer and 100 μl 200 mM PMSF per 1 ml pellet; see Reagents and Solutions) and incubating 30 min at 4°C.

Clear nuclei and other debris by centrifuging 30 min at 15,000 × g, 4°C. Decant the lysate and filter through a 0.8-μm filter. Store the lysate at 4°C or continue directly with the purification.

Purify MHCs

-

4Pass lysate by gravity flow twice through two 50-ml precolumns: an inactivated Sepharose CL-4B column (10-ml bed volume) followed by a protein-A Sepharose-CL-4B column (5-ml bed volume).Both of these columns are stable for ~6 months to 1 year, depending on usage. Prior to use, these columns should be stripped with elution buffer, and then neutralized with washing buffer.

-

5Capture MHC by two passages on a protein A–Sepharose CL-4B column conjugated with the appropriate anti-MHC antibody (10-ml bed volume).Monoclonal antibodies relevant for human and mouse Class I and Class II molecules, and their specificities, are listed in Table 18.3.5. Depending on the antibodies used, it may be necessary to cascade a set of columns of differing antibody specificity to capture the appropriate MHC molecule. For example, the purification of HLA-DR molecules may be performed by removing HLA-A, -B, and -C molecules from the lysate by passage over a W6/32 (anti-HLA-A, -B, and -C) column, and then capturing DR molecules with an LB3.1 (anti-HLA-DR alpha) column.

-

6

Wash column by gravity flow with 4 column volumes (200 ml) of washing buffer.

-

7

Wash column with 50 ml PBS/0.4% octylglucoside. Allow wash to proceed to dryness.

-

8Elute MHC from the column with 50 ml elution buffer. Immediately neutralize the eluate with 2 M Tris·Cl, pH 6.8, for Class I MHC or 2 M glycine, pH 2.5, for Class II MHC, until pH 7 to 7.5 is reached.The column should also be immediately neutralized using washing buffer.

-

9Concentrate MHC preparation to a final volume of ~500 μl in a Centriprep-30 concentrator, according to manufacturer's specifications.Protein content may be evaluated using a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce) and confirmed by SDS-PAGE (UNIT 8.4). MHC preparations should be stored at 4°C. Alternatively, they may be diluted 50% with glycerol, and stored at –20°C. Stability in storage varies for different preparations and cell lines. Most preparations are stable for years at 4°C; others degrade within weeks and must be kept at –20°C.

RADIOLABELING OF PEPTIDES BY THE CHLORAMINE T METHOD

Peptides to be used as radiolabeled probes are iodinated using the chloramine T method (UNIT 8.11; Greenwood et al., 1963; Bolton and Hunter, 1986).

Materials

Tyrosinated peptide (10 to 20 mg/ml)

Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4 (APPENDIX 2A) with and without 0.05% Tween 20 (Sigma)

~40 μM [Na125]I (~100 μCi/μl; NEN Life Sciences, Perkin Elmer)

0.1 mg/ml chloramine T (Sigma) in PBS/0.05% Tween 20

0.1 mg/ml sodium metabisulfite (Fisher) in PBS/Tween

10% (w/v) sodium azide

Ethanol

0.82% NP-40

Sephadex G-10 column: multispin separation kits (Genesee Scientific) with a 0.8 ml bed volume suspended in PBS, pH 7.2

Microcentrifuge: Labnet International Spectrafuge 16M (cat. no. C0160-R; http://www.labnetinternational.com/)

Polyethylene storage vessel (e.g., 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes)

Label peptide

Dilute tyrosinated peptide at 1:600 for Class II, or 1:1200 for Class I, in PBS/0.05% Tween 20.

Decant excess PBS from a G-10 filled multispin column.

- Incubate 12.5 μl diluted peptide sequentially, for 60 sec per step, with each of the following:

- 100 μCi [Na125]I (~1 μl)

- 10 μl 0.1 mg/ml chloramine T (the reaction catalyst)

- 10 μl 0.1 mg/ml of sodium metabisulfite (to quench the reaction).That is, the peptide is incubated for 60 sec in the presence of Na[125I], and then, to catalyze the reaction, for an additional 60 sec after adding chloramine T. Lastly, to quench the reaction, the peptide is incubated for a final 60 sec in the presence of sodium metabisulfate. The radiolabeled peptides should be as hot as possible. Labels of low specific activity require the use of high amounts of radiolabeled peptide in the binding assay to achieve a significant signal. However, the use of too large an excess of peptide reduces the sensitivity of the assay substantially (see Troubleshooting, discussion of radiolabeled peptide). The proportions given here yield labeled peptide preparations of suitable specific activity for the binding assay; typically, between 0.01 and 0.1 μl of labeled peptide should be sufficient to give 10,000 counts per well.

Dilute the quenched reaction with 25 μl PBS/0.05% Tween 20.

- Separate labeled peptide from free iodine by passing the reaction over the G-10 multispin columns. Layer the newly labeled peptide on the G-10 beads so as not to disturb the bed, and spin in centrifuge for 2 min at 1 speed (see the note below). Add 50 μl PBS, pH 7.4, to the top of the spin column×and centrifuge for another 2 min at 1× speed. Next add 150 μl of PBS, 7.4, and centrifuge for an additional 2 min at 1× speed. Then, in a last rinse, add 75 μl PBS, pH 7.4, and centrifuge again for 2 min. Collect the labeled peptide in a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube containing 5 μl of 10% NaN3, 10 μl ethanol (as a free radical scavenger), and 25 μl 0.82% NP40/PBS. Store at 4°C.The centrifugal force of the specific microcentrifuge that we utilize (Labnet International Spectrafuge 16M, catalog #C0160-R) is 82 times the force of gravity when the centrifuge dial is set at its 1× speed. Because each make and model of microcentrifuge will be different in terms of rotor size and weight, etc., the appropriate speed adjustment necessary to obtain force appropriate to allow clear separation of free and bound iodine must be determined empirically for each specific instrument.It is crucial that these settings be optimized to enable consistent and sufficient separation of the radiolabeled peptide from the later-eluting free iodine. Besides ensuring collection of the maximal amount of radiolabeled peptide, establishing the optimal times for separation ensures that radiolabeled peptide preparations are free from contaminating amounts of free iodine, the presence of which would represent a major safety risk outside of an appropriate chemical hood.The length of time that a peptide remains usable as a label is dependent on the particular peptide. Typically, a label remains very active for 2 to 3 weeks. The integrity of a label may be checked periodically by HPLC. If any sign of degradation is detected, the peptide should be discarded, even if binding is observed. Otherwise, the quantitative aspects of the peptide-MHC assay could be seriously affected.

DIRECT BINDING ASSAYS TO IDENTIFY APPROPRIATE HIGH-AFFINITY LIGANDS

In the establishment of a binding assay, it is necessary to identify an appropriate high-affinity ligand that can be used as the radiolabeled probe in subsequent inhibition assays. A high-affinity ligand not only ensures that the assay will be as sensitive as possible, but also allows the most efficient use of a purified MHC preparation. The importance of identifying a high-affinity ligand cannot be overstated.

Additionally, it is necessary to perform complete titrations of MHC preparations. These titrations reveal the appropriate concentration of MHC for use in inhibition assays, which is also a critical factor in determining assay sensitivity. A high MHC concentration results in poor assay sensitivity, while a low concentration yields a signal that is difficult to distinguish from background. Under conditions where [label] < [MHC], and IC50 ≥ [MHC], measured IC50 values are reasonable approximations of true Kd values. With typical MHC preparations, these conditions are achieved when the percent bound radioactivity is ~15%, or with a signal to noise ratio of 5 to 10.

The identification of an appropriate high-affinity ligand and the determination of the optimal MHC concentration are both done using direct binding assays. These assays are performed essentially as described in the Basic Protocol, with the following variations at the indicated steps. MHC titrations and ligand screening can be performed simultaneously by combining these steps.

For materials, see Basic Protocol.

For MHC titrations

-

2a

Rather than loading 5 μl of an inhibitor peptide (see Basic Protocol, step 2), add 5 μl of various concentrations of MHC to the assay well. As in the Basic Protocol, load the negative control (no MHC) wells with 5 μl PBS/0.05% (v/v) NP-40.

-

3a

Omit MHC from the 10 μl reaction mix (see Basic Protocol, step 3), replacing it with an equal volume of PBS or citrate/phosphate buffer.

For screening ligands

-

3b

Perform multiple binding assays using a separate reaction mix (see Basic Protocol, step 3) for each labeled peptide.

SEPARATION OF MHC-PEPTIDE COMPLEXES BY SIZE-EXCLUSION GEL-FILTRATION CHROMATOGRAPHY

Filtration

The use of HPLC systems capable of automated loading, separation, radio-detection, and data analysis of samples following incubation offers the potential to analyze binding events literally around the clock. As a result, hundreds of data points may be generated daily. For automated separation, use a TosoHaas QC-PAK TSK GFC200 column (7.8 mm × 15 cm) with a particle size of 5 μm. Use PBS, pH 6.5 (APPENDIX 2A), containing 0.5% (v/v) Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) and 0.1% (w/v) sodium azide as the eluent, at a flow rate of 1.2 ml/min. In this configuration, one sample can be analyzed every 7 to 9 min, depending on the age of the column. Set up the HPLC hardware configuration to include an integrator (e.g., Hewlett-Packard 3396A), a disc drive (e.g., Hewlett-Packard 9114B), a dilutor (e.g., Gilson 401), a sample injector (e.g., Gilson 231), a radioisotope detector (e.g., Beckman 170), and a solvent delivery module (pump; e.g., Beckman 110B).

Alternatively, samples may be separated manually by gravity flow over medium-grade Sephadex G-50 (Buus et al., 1986; O'sullivan et al., 1990), or with spin columns (Boyd et al., 1992; Olsen et al., 1994). For Sephadex G-50 separation on a 22.5 × 1.5–cm borosilicate column, elute with PBS, pH 7.0 (APPENDIX 2A) containing 0.5% (v/v) NP-40 and 0.1% (w/v) sodium azide. Collect 1-ml fractions and determine the amount of radioactivity per fraction with a standard gamma counting apparatus. Although this method cannot achieve the high throughput of an automated system, its low cost may be attractive in situations where only a limited number of samples need to be analyzed.

Analysis

Chromatographic separation typically results in the identification of two prominent peaks, representing peptide-MHC complexes and free peptide, respectively (Fig. 18.3.1). Calculate percent binding, which is equal to the percent area of the first peak relative to the total area integrated:

Calculate IC50 values for each test peptide by plotting dose versus percent inhibition, where:

Use this plot to extrapolate the dosage yielding 50% inhibition (IC50). Assay sensitivity may vary somewhat from day to day, or between batches of purified MHC. To compare data obtained in different experiments and with different batches of MHC, normalize binding values for each peptide to an assay-specific positive control for inhibition (i.e., the assay standard peptide; see Basic Protocol, step 2). These relative binding values represent the ratio of the IC50 of the positive control for inhibition to the IC50 of the test peptide:

Relative binding values appear to be the most accurate and consistent for comparing peptides that have been tested on different days or with different lots of purified MHC. To convert back into nM IC50 values, divide the nM IC50 of the positive controls for inhibition by the relative binding of the peptide of interest.

Affinity/rate constant information may be obtained directly using the direct binding assay (see Alternate Protocol). In this case, multiple tubes/wells are set up, and % binding is determined at multiple time points starting from t = 0. Constants may then be calculated as described in any basic biochemistry text.

SEPARATION OF MHC-PEPTIDE COMPLEXES BY ANTIBODY-BASED MHC CAPTURE

Capture Assay

As a more efficient, higher-throughput alternative to the gel-filtration-based separation protocol described in Support Protocol 3, MHC-peptide complexes can be separated from unbound peptide using monoclonal antibody capture. In this approach, monoclonal antibodies specific for various MHC types are coated onto the wells of 96-well microplates. After an incubation phase to maximize MHC capture, the plates are washed and the amount of bound radioactivity is determined with a microscintillation counter.

The specific approach described here has been developed to use 96-well white polystyrene microtiter plates specifically designed for high-volume, in-plate, radiometric assays. Measurement of the 125I-labeled peptide bound to MHC is accomplished using the Topcount (PerkinElmer Instruments) benchtop microplate scintillation and luminescence counter, although other system configurations are feasible.

Capture assays are performed essentially as described in the Basic Protocol. In this section, however, we have provided additional details, including some variations, facilitating the use of the capture assay for the purpose of high-throughput screening. Accordingly, the present section details dilution and handling of peptides for compatibility with the 96-well format, preparation of antibody-coated plates, transfer of assay samples for the MHC-capture phase, and then final washing and counting of the plates. All of the steps described here can be performed with standard 8- or 12-channel pipettors, and most can take advantage of the high capacity of instrumentation such as automated plate washers and other liquid-handling devices. As described here, the protocol can essentially permit the analysis of about 150 plates, or 3600 samples, per Topcount instrument, per day.

Additional Materials (also see Basic Protocol)

Anti-MHC monoclonal antibody (see first annotation to step 9): 30 μg/ml in 0.1 M Tris·Cl, pH 8.0 (APPENDIX 2A; the same antibodies used for the affinity columns for MHC purification are used in the capture assay)

Blocking solution: 0.3% (v/v) Tween 20 in PBS or 1% (w/v) BSA in PBS

96-well round-bottom polystyrene microtiter plate (Greiner-bio-one, cat. no. 650201, http://www.greinerbioone.com/en/start/)

Mylar plate sealer with adhesive back (MP Biomedicals, LLC, cat. no. 76-402-05)

View Seal (Greiner-bio-one, cat. no. 676070, http://www.greinerbioone.com/en/start/)

Costar Sealing Mat (Corning, cat. no. 3080)

96-well flat-bottom white polystyrene Optiplate (Greiner-bio-one, cat. no. 655074, http://www.greinerbioone.com/en/start/)

TopSeal-A for 96-well microplates (PerkinElmer, cat. no. 6005185)

Microscint-20 (PerkinElmer; Cat. #6013621)

Topcount microscintillation counter (Perkin-Elmer Instruments)

Basic capture assay setup

Dilution of inhibitor peptides

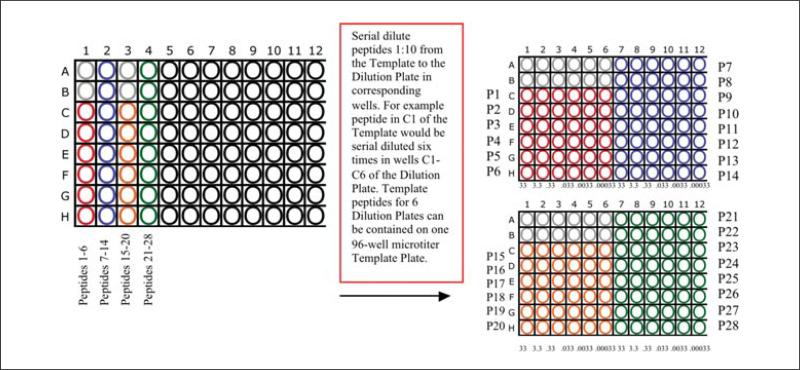

- Inhibitor peptides are first diluted 1:10 in a “Template Plate” (Fig. 18.3.2). Peptides then undergo six subsequent 1:10 serial dilutions in a “Dilution Plate.” Typically, the six serial dilutions in the “Dilution Plate” range from 100 μg/ml to 300 pg/ml. The six serial dilutions from the “Dilution Plate” are transferred at 5 μl/well into the “Assay Plate.” Since the final assay volume is 15 μl, this represents an assay range of 33 μg to 0.33 ng.

- Dilute inhibitor peptides 1:10 in 96-well round-bottom polystyrene microtiter plates (“Template Plate”) using 0.05% NP-40. Typically, 5.5 μl of 10 mg/ml peptide is diluted into 50 μl 0.05% NP-40, although larger (or smaller) volumes may be utilized if necessary.

- Further dilute inhibitor peptides in 0.05% NP-40 in additional 96-well round bottom polystyrene microtiter plates (“Dilution Plate”) six times in 10-fold serial dilutions.

- The “Dilution Plate” is typically laid out with peptide 1 in C1 to C6, peptide 2 in D1 to D6, etc., with peptides 7 to 12 in A7 to A12, B7 to B12, etc. Wells A1 to A6 and B1 to B6 are left blank such that standard and control peptides may be added to the “Assay Plate.”

- High-affinity peptides, such as those used as the assay standard (i.e., a positive control), may require additional dilution to ensure that an appropriate titration range is achieved to cover from 100% to 0% inhibition.

- Seal the “Template Plate” and the “Dilution Plate” with plate sealer (mylar or mat) for storage. Plates may be stored at 4°C for up to 4 weeks.

Figure 18.3.2.

Example layout for serial dilution of inhibitor peptides amenable to high throughput screening.

Assay plate set-up

-

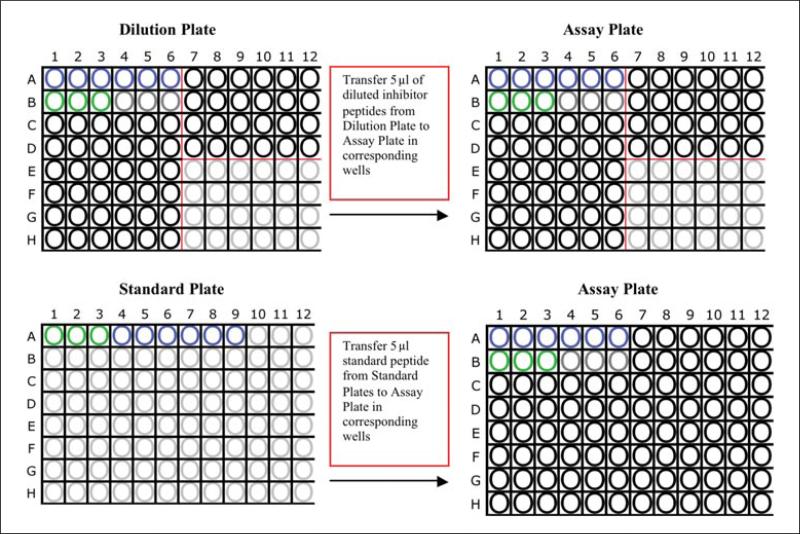

2Transfer 5 μl from each well of the “Dilution Plate” to the corresponding well in the “Assay Plate” (Fig. 18.3.3). For replicates, this may be done in triplicates, or other replicates.

- Load 5 μl of the six lower dilutions of standard peptide to the “Assay Plate” from the “Standard Plate” in wells A1 to A6.

- Load 5 μl of “high-concentration” standard peptide to wells B1 to B3. These wells are negative (background) control wells. “Cold Mix” is also loaded into these wells (see below).

- Wells B4 to B6 are not loaded with peptide as they are the no-inhibitor positive control wells. Only “Hot Mix” (see below) and 5 μl PBS NP-40 is loaded into these wells.

Figure 18.3.3.

Example layout for setting-up assays plates to screen serial dilutions covering a 6-log dose range.

Prepare radiolabeled peptide/MHC mix (Hot Mix)

-

3

The radiolabeled peptide/MHC mix is prepared as described in the Basic Protocol. Dispense the radiolabeled peptide/MHC mix at 10 μl/well into the “Assay Plate” containing the unlabeled inhibitor peptides. Do not add “Hot Mix” to the negative (background) control wells, B1 to B3.

Prepare protease inhibitors (PI Mix)

-

4

Protease inhibitors are prepared as described in Reagents and Solutions.

Plate out controls

-

5Add the No Inhibitor (+) into wells B4 to B6 of the 96-well round-bottom “Assay Plate.” Alternatively, these wells may be loaded when loading the inhibitor peptide wells. The no-inhibitor control contains the following ingredients.

- 10 μl/well “Hot Mix” (radiolabeled peptide/MHC mix).

- 5 μl/well 0.05% NP-40.

-

6Add the Cold (–) (Background) Control into wells B1 to B3 of the 96-well round bottom “Assay Plate.” This mix is the same as the Hot Mix, but without MHC. Enough mix should be prepared sufficient for all of the “Assay Plates.” These wells contain:

- 5 μl “high concentration” unlabeled high-affinity peptide.

- 10 μl “Cold Mix,” composed of:

- 2 μl protease inhibitor cocktail.

- X μl 125I-labeled peptide (enough to provide assay specific optimal cpm).

- Spike: 0.1 μl or 0.3 μl β2 microglobulin at 2 mg/ml or 1 μl detergent, as in “Hot Mix.”

- 6 μl pH buffer if other than pH 7.2 is used.

- X μl PBS, pH 7.2 (adjust volume for a total of 10 μl).In general, Class I assays have optimal sensitivity at 8,000 to 10,000 cpm of input radioactivity. Class II assay have optimal sensitivity at about 15,000 cpm, although in some cases higher counts (up to about 40,000 cpm) may be necessary.

Seal and incubate plates

-

7

Seal plates with Greiner bio-one View Seal. Alternatively, plates may also be sealed with a Costar Sealing Mat applied with a Costar Sealing Press. These sealing mats may be recycled once for room temperature assays (assays incubated at 37°C must be sealed with a new sealing mat).

-

8

Incubate plates in the dark, at room temperature or 37°C, for 48 to 120 hr. All Class I assays are incubated for 48 hr at room temperature. For Class II, see Tables 18.3.3 for assay-specific temperature and incubation times.

Coat capture plates

-

9Coat antibody capture plate(s) (Optiplates) with 125 μl/well of anti-MHC antibody.Anti-MHC antibodies, such as W6/32 or L243 (see Table 18.3.5), are common reagents available from a wide variety of commercial vendors (e.g., OneLambda, eBioscience, etc.). However, such sourcing can be prohibitively expensive, given the quantity of antibody required. Alternatively, it is recommended that antibodies be purified from hybridomas (see Table 18.3.5) following standard methods (see, e.g., Bonifacino et al., 2013, Chapter 16). Purification from hybridomas on a large scale can also be performed under contract from various vendors, such as Strategic Biosolutions (http://www.sdix.com/) or Maine Biotechnology Services, Inc. (http://www.mainebiotechnology.com/).Antibody stocks must be kept frozen until needed. Thawed aliquots of purified antibody are added to 0.1 M Tris·Cl, pH 8.0, to make a working antibody solution with a final concentration of 30 μg/ml. Because the working solution is at 30 μg/ml, each well is effectively coated with 3.75 μg of antibody.Plates are incubated at room temperature, in the dark, for 24 hr. With the exception of B*4402 and B*4403, which are captured with the B123.2 antibody, all primate Class I assays are captured using the W6/32 antibody. Mouse Class I assays are captured using the antibodies as listed in Table 18.3.5. See Table 18.3.2 to determine the specific antibody used to capture a specific Class II MHC.

Block coated plates

-

10

Antibody solution is removed from the 96-well flat-bottom Optiplate and discarded, or collected for recycling (retrieved antibody solution may be used for one additional coating).

-

11Blocking solution (0.3% Tween 20 /PBS or 1% BSA/PBS) is added to each well, at 180 μl for short-term storage, or 200 μl/well for long-term storage. Typically, Class I antibody capture plates are blocked with 0.3% Tween 20/PBS and Class II antibody capture plates are blocked with 1% BSA to reduce background counts.96-well flat bottom Optiplates pre-coated with anti-MHC antibody can be used for the capture assay after incubating with blocking buffer at least 3 hr. Plates can be stored up to 5 days at room temperature, or stored for up to 3 months at 4°C with blocking solution remaining in the wells. If stored, plates must be covered with mylar adhesive seals.

Prepare capture plates

-

12Antibody pre-coated and blocked Optiplates (see above) must be prepared before the “Assay Plate” is transferred into them. To prepare the Optiplate:

- Remove blocking buffer.

- Wash plates with 200 μl of 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20/PBS two times.

- Transfer the “Assay Plate” into the antibody plate as soon as possible to prevent the antibody from drying inside the plate.

Transfer binding assay

-

13Peptide/MHC complexes from binding “Assay Plates” are transferred to anti-MHC antibody coated and blocked plates.

- Add 100 μl of 0.05% NP-40/PBS to each well of the 96-well round-bottom microtiter assay plate. The entire plate can be transferred at one time using the Costar 96-well pipettor and the Costar 96-well pipet cartridge.

- Using a 12-channel pipettor set at 125 to 150 μl or a Costar 96-well pipettor, transfer each well from the assay plate to the precoated/blocked and washed antibody plate.

- If using the Costar 96-well pipettor and the Costar 96-well pipet cartridge, change the cartridge after approximately nine plates, or when transferring different alleles.

- The antibody plate is then sealed with a mylar adhesive seal and incubated at room temperature for > 3 hr for Class I and most Class II assays. Some Class II assays are incubated for up to 24 hr (see Table 18.3.3).

Wash and count capture assay plate

-

14

Once the capture step (step 13) is completed, the liquid contents of the plate are discarded into an appropriate radioactive liquid waste container.

-

15

Wash plates with 200 μl of 0.05% Tween 20/PBS two times for Class I assays, and four times for Class II assays.

-

16

Dispense Microscint-20 scintillation fluid at 125 μl to each well, then seal the plates with a TopSeal adhesive cover sheet. Wipe plates with antistatic wipes.

-

17

Radiolabeled peptide binding to MHC is then determined by counting cpm for 1 min for each plate in the TOPCOUNT microscintillation and luminescence counter.

Notes on capture assay variations

Some assays require specific conditions and reagents. Essentially, however, all Class I and most Class II assays are performed at pH 7 and incubated at room temperature for 48 hr, followed by a 3-hr antibody plate capture incubation. However, all HLA-DQ assays, and some DP and DR assays, must be incubated at 37°C for 72 hr, followed by a 24-hr antibody plate capture incubation.

Class I assays always have a β2-microglobulin spike, whereas Class II assays require different detergent spikes. 1.6% NP-40 is generally used for DR and DP assays, while 0.82% Pluronic or 1.6% Pluronic is used for DQ assays. Additionally, some H-2 Class II assays require a 10% digitonin spike. Assays may also differ in their final pH. These assay variations for Class II are indicated in Table 18.3.3.

Analysis

In principle, analysis of data generated from the capture assay is performed essentially as described in Support Protocol 3 for the gel filtration–based assay. The primary difference is that while the chromatographic separation results in the identification the percent of input radioactivity associated with the free peptide and peptide-MHC complex species, the capture assay provides a direct count of cpm associated with radiolabeled peptide bound to the MHC. As with the gel-filtration system, the percent inhibition of binding of the radiolabeled peptide attributed to the specific dose of the input unlabeled inhibitor peptide can be determined by comparison with the positive control wells (i.e., those with no inhibitor peptide added). Then, the IC50 value of a test inhibitor peptide can be determined with a dose-response curve (dose versus percent inhibition).

PREPARATION OF IMMUNOAFFINITY COLUMNS

Anti-MHC antibodies, such as W6/32 or L243 (see Table 18.3.5), are common reagents available from a wide variety of commercial vendors (e.g., OneLambda, eBioscience, etc.). However, such sourcing can be prohibitively expensive, given the quantity of antibody required. Alternatively, it is recommended that antibodies be purified from hybridomas (see Table 18.3.5) following standard methods (see, e.g., Bonifacino et al., 2013, Chapter 16). Purification from hybridomas on a large scale can also be performed under contract from various vendors, such as Strategic Biosolutions (http://www.sdix.com/) or Maine Biotechnology Services, Inc. (http://www.mainebiotechnology.com/). A typical purification column will have a bed volume of 10 ml. Antibody is used at a ratio of 2 to 3 mg per ml of column bed.

Triethanolamine, DMP, and ethanolamine solutions should all be made immediately before use.

Materials

Protein A–Sepharose CL4 B (Sigma, cat. no. P-3391)

Sepharose CL4 B (Sigma, cat. no. CL4B-200; for use in uncoupled pre-columns)

100 mM borate buffer, pH 8.2: dissolve 6.18 g boric acid (Sigma, cat no. B-7660)/9.54 g borax (Sigma, cat. no. B-0127)/4.38 g NaCl in H2O

Monoclonal antibody (approximately 20 to 30 mg; see annotation to step 3) in PBS, pH 7.2 (see below) at a concentration of about 2 mg/ml or higher

PBS, pH 7.2: 20 mM Na2HPO4/150 mM NaCl/0.05% NaN3

200 mM triethanolamine, pH 8.2 (Sigma, cat. no. T-1377)

20 mM dimethyl pimelimidate (DMP; Pierce, cat. no. 21667) in 200 mM triethanolamine, pH 8.2

Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Invitrogen, cat. no. 10010-023) containing 0.02% sodium azide (NaN3; Fisher Scientific, cat. no. S227-500)

20 mM ethanolamine pH 8.2 (Sigma, cat. no. E-9508)

0.02% sodium azide (NaN3) (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. S227-500) in PBS, pH 7.2 (Invitrogen, cat. no. 10010-023)

Elution buffer (see recipe)

2 M glycine, pH 2.5

Washing buffer: 10 mM Tris·Cl, pH 8.0 (APPENDIX 2A) with 1% Nonidet P-40 (store up to 6 months at 4°C)

50-ml borosilicate glass column with stopcock

Rotator

Spectrophotometer

- Swell Protein A–Sepharose-CL4B (or Sepharose-CL4B for columns without antibody) in a column with 40 ml of borate buffer for 1 hr, while gently rotating the column.Approximately 2.5 mg of Protein A Sepharose-CL4B is used per 10 ml of column bed. A 10-ml column bed is the most commonly used column.

After swelling, drain, and then wash the column twice with 10 ml borate buffer.

Add 2 to 3 mg of antibody for each ml of bed volume, bring the volume to 40 ml with borate buffer, and incubate for 1 hr at room temperature on a rotator.

Collect the flowthrough and read optical density at 280 nm. If the reading is more than 20% of the initial reading, incubate for another hour.

Wash the column with 50 ml of borate buffer. Collect the flowthrough in 10-ml fractions and measure OD at 280 nm. Continue washing until the reading is less than 0.020.

Wash the column with 20 ml of 200 mM triethanolamine pH 8.2.

- Add 40 ml of 20 mM dimethyl pimelimidate (DMP) in 200 mM triethanolamine and incubate for 45 min at room temperature on a rotator.For this and the remaining steps, always save the column flowthrough in case the antibody did not cross-link.

Wash twice with 10 ml of 20 mM ethanolamine, pH 8.2, leaving the column on the rotator for 5 min between washes.

Wash the column with 200 ml of borate buffer, then with 100 ml PBS containing 0.02% sodium azide.

Take a final OD280 reading of flowthrough to completion of coupling. Store the column upright at 4°C in borate buffer.

To verify the column is not leaking antibody, perform a sham elution by passing 30 ml of elution buffer through the column and collect the flowthrough. Neutralize the flowthrough to pH 7.0 to 8.0 with 2 M glycine, pH 2.5. At the same time, neutralize the column to pH 8.0 using washing buffer, pH 8.0. Concentrate the flowthrough and run a gel to confirm that the column is not leaking antibody (no bands should appear on the gel).

REAGENTS AND SOLUTIONS

Use deionized, distilled water in all recipes and protocol steps. For common stock solutions, see APPENDIX 2A; for suppliers, see APPENDIX 5.

Citrate/phosphate buffer

Prepare stock solutions of 0.1 M citric acid (19.21 g/liter) and 0.2 M dibasic sodium phosphate (e.g., 53.65 g/liter Na2HPO4 ·7H2O). To prepare a working buffer at the desired pH, mix as shown in Table 18.3.6, and dilute to 100 ml with water. Store both stock and working solutions up to 6 months at 4°C.

Table 18.3.6.

Preparation of Citrate/Phosphate Buffer Working Solutions from Stock Solutionsa

| Citric acid (ml) | Phosphate (ml) | pH |

|---|---|---|

| 44.6 | 5.4 | 2.6 |

| 42.2 | 7.8 | 2.8 |

| 39.8 | 10.2 | 3.0 |

| 37.7 | 12.3 | 3.2 |

| 35.9 | 14.1 | 3.4 |

| 33.9 | 16.1 | 3.6 |

| 32.3 | 17.7 | 3.8 |

| 30.7 | 19.3 | 4.0 |

| 29.4 | 20.6 | 4.2 |

| 27.8 | 22.2 | 4.4 |

| 26.7 | 23.3 | 4.6 |

| 25.2 | 24.8 | 4.8 |

| 24.3 | 25.7 | 5.0 |

| 23.3 | 26.7 | 5.2 |

| 22.2 | 27.3 | 5.4 |

| 21.0 | 29.0 | 5.6 |

| 19.7 | 30.3 | 5.8 |

| 17.9 | 32.1 | 6.0 |

| 16.9 | 33.1 | 6.2 |

| 15.4 | 34.6 | 6.4 |

| 13.6 | 36.4 | 6.6 |

| 9.1 | 40.9 | 6.8 |

| 6.5 | 43.6 | 7.0 |

See recipe for citrate/phosphate buffer in Reagents and Solutions.

Elution buffer

0.15 M NaCl

50 mM diethylamine

1% (w/v) octylglucoside

0.02% (w/v) sodium azide

Adjust pH to 11.5

Store up to 6 months at 4°C

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 86 mg/ml

Prepare 86 mg/ml tetrasodium EDTA tetrahydrate (Calbiochem, cat. no. 34103) in PBS (APPENDIX 2A). Warm gently in a water bath if EDTA does not go into solution easily. Adjust pH to 7.0 with 10 N NaOH. Store up to 6 months at –20°C.

Lysis buffer

20 mM Tris·Cl, pH 8.5 (APPENDIX 2A)

1% (v/v) Nonidet P-40 (NP-40; Fluka)

150 mM NaCl

2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF)

Adjust pH before adding detergent. Store without PMSF up to 6 months at 4°C. Immediately before use, add PMSF from a 40 mg/ml stock in isopropanol (store PMSF up to 6 months at –20°C).

Protease inhibitor cocktail

61 μl PBS/NP-40: PBS, pH 7.2 (APPENDIX 2A) with 0.82% (v/v) Nonidet P-40 (NP-40)

12 μl 8 mM tetrasodium EDTA (tetrasodium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tetrahydrate; 86 mg/ml in PBS, pH 7.2; Calbiochem, cat .no. 34103)

12 μl 73 μM pepstatin A (5 mg/ml in methanol; EMD, cat no. 516481)

12 μl 0.8 M N-ethylmaleimide (NEM; 100 mg/ml in isopropanol; Class II assays; Sigma, cat. no. E-1271)

12 μl 1.3 nM 1,10-phenanthroline (26 mg/ml in ethanol; Sigma, cat. no. P-9375)

6 μl 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF; 40 mg/ml in isopropanol; Sigma, cat. no. P-7626)

3 μl 200 μM Nα-p-tosyl-L-lysine chloromethyl ketone (TLCK) hydrochloride (20 mg/ml in PBS; Sigma, cat. no. T-7254)

- Prepare fresh, immediately before use (e.g., within 2 min)NEM is not used in Class I assays; replace NEM with 12 μl isopropanol.For murine IA assays only, replace PBS/NP-40 with 61 μl of 20% digitonin (Fluka, Wako) or 61 μl Pluronic (PBS, pH 7.2, with 0.82% (w/v) Pluronic).Stock solutions can be stored up to 6 months at –20°C. It may be necessary to resolubilize the PMSF by gently warming before use.Because of water/alcohol mixing and alcohol evaporation, each batch yields ~100 μl of retrievable cocktail. A single large batch that is sufficient for the entire experiment should be made at the start.

COMMENTARY

Background Information

The induction and functionality of both helper and cytotoxic T cells are dependent upon the formation of a trimolecular complex between antigenic peptides, Class I or Class II MHC molecules, and the antigen-specific TCR of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. As such, this event represents one of the most crucial elements in the generation of immune responses. Indeed, both the normal functions of the immune response—e.g., induction of delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) responses against parasites, induction of cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses against tumors and viruses, and induction of specific antibodies against bacteria—as well as pathological reactions—e.g, autoimmunity and allergy—are ultimately dependent on the formation of such trimolecular complexes. To gain insight into the very basis of the functioning of the immune system, it is evident that the accurate and quantitative measurement of the capacity of peptides to bind MHC is essential.

Recognition of the vital role of peptide-MHC complexes in the immune response has generated considerable interest over the years in understanding the biology of peptide-MHC binding (for early, but still very relevant, reviews see, for example, Sette and Grey, 1992; Barber and Parham, 1993; Germain, 1993, 1994; Germain and Margulies, 1993; Engelhard, 1994; Joyce and Nathenson, 1994; Rothbard, 1994; Rötzschke and Falk, 1994; Sinigaglia and Hammer, 1994; Stern and Wiley, 1994; Madden, 1995; Rammensee et al., 1995). X-ray crystallographic structures of dozens of MHC molecules and MHC-peptide complexes have been reported in the literature, and new binding motifs still appear regularly. A considerable amount of data is now also available regarding the processing of peptides and the recognition of peptide-MHC complexes by T cell receptors.

Various methods, encompassing both whole-cell and cell-free systems, have been employed to characterize peptide binding to MHC molecules. Assay systems that are powerful in characterizing MHC peptide binding motifs or in identifying individual bound peptides include the use of phage-display libraries (Hammer et al., 1993), the sequencing of naturally processed peptides, either individually or in pools (van Bleek and Nathenson, 1990; Falk et al., 1991; Harris et al., 1993), and tandem mass spectrometry (Hunt et al., 1992; Cox et al., 1994).

Other assay systems are more amenable to the quantitation of the binding of individual peptides. A number of these systems use live-cell assays (Ceppellini et al., 1989; Busch et al., 1990; Christnick et al., 1991; Hill et al., 1991; del Guercio et al., 1995). Cell-free systems utilize detergent lysates (e.g., Cerundolo et al., 1991), biotinylated and europium-labeled ligand binding to immobilized purified MHC (Hill et al. 1994; Marshall et al., 1994), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs; Reay et al., 1992; Sylvester-Hrid, 2002, 2004), surface plasmon resonance (Khilko et al., 1993), and a high-flux soluble-phase assay using both radiolabeled peptides and biotinylated antibodies (Hammer et al., 1994). Assays specific for Class I MHC based on stabilization or assembly are also commonly utilized (Ljunggren et al., 1990; Schumacher et al., 1990; Townsend et al., 1990; Parker et al., 1992). Buus and co-workers have developed high-throughput nonradioactive binding assays based on Luminescent Oxygen Channeling (LOCI) for both Class I (Harndahl et al., 2009) and Class II molecules (Justesen et al., 2009), as well as an essentially label-free scintillation proximity assay allowing real-time measurement of peptide-MHC Class I dissociation (Harndahl et al., 2011). Dedier and co-workers, as well as Hildebrand's group, have used fluorescence polarization and solubilized MHC for real-time measurement of peptide binding (Dedier et al., 2001; Buchli et al., 2004, 2005). The assay system described in this unit utilizes 125I-labeled peptide ligands and detergent-solubilized, affinity-purified MHC molecules. Similar procedures using solubilized MHC have also been reported (Roche and Cresswell, 1991; Boyd et al., 1992; Olsen et al., 1994).

Each method, including the one described in this unit, has distinctive advantages and disadvantages. Many of these aspects have been reviewed elsewhere (Engelhard 1994; Joyce and Nathenson, 1994; Hammer, 1995; Rammensee et al., 1995). The procedure described here is recommended because of its overall adaptability and very high sensitivity (typically in the 1 to 5 nM range). The techniques, reagents, and materials required are readily available to most immunology laboratories, and are relatively inexpensive. The method is highly quantifiable and very reproducible, and specifically addresses the capacity of individual peptides to bind MHC, rather than their capacity, for example, to survive processing in a live-cell environment. The method's high-throughput capacity enables screening of large peptide libraries in a reasonable period of time. As a result, detailed peptide binding motifs can be ascertained while simultaneously characterizing the binding of individual peptides. This particular utility has been demonstrated in a number of instances for both Class I (see, for example, Ruppert et al., 1993; Kondo et al., 1995, 1997; Sidney et al., 1996a,b; 2008a; for review see, e.g., Sidney et al., 2008b) and Class II (see, for example, O'sullivan et al., 1990, 1991; Sette et al., 1990, 1993; Sidney et al., 1992, 1994; 2001a,b; Alexander et al., 1994; Geluk et al., 1994, Greenbaum et al., 2011) molecules. Besides the identification of anchor residues, motifs generated by this procedure can also precisely address the facilitative or deleterious effects of specific amino acids at specific secondary positions.

Critical Parameters

Identification of a high-affinity ligand

The identification of a high-affinity ligand that can be radiolabeled and gives a clearly detectable signal is perhaps the single most challenging problem in establishing an MHC binding assay. Until such a ligand is identified and some binding is detected, it is not possible to optimize the experimental conditions and establish a final protocol.

This hurdle may often be bypassed by using peptides restricted to the MHC molecule of interest, or by using natural or engineered peptides known to have degenerate MHC binding (e.g., Sinigaglia et al., 1988; Ceppellini et al., 1989; Panina-Bordignon et al., 1989; Busch et al., 1990; Sette et al., 1990, 1994; Hill et al., 1991; Roche and Cresswell, 1991; Ruppert et al., 1993; Alexander et al., 1994; Kondo et al., 1995; Sidney et al., 1996a,b). In some cases, if the tyrosine residue required for iodination is not present in the parent sequence, it may be necessary to synthesize analogs. In these instances, a tyrosine residue should be substituted for a noncritical residue, if possible. Thus, for Class I ligands, the substitution is typically made at positions other than position 2 and the C-terminal main anchor. For Class II ligands, suitable peptides may be synthesized by adding an N- or C-terminal tyrosine. In both instances, if internal tyrosine residues are present in the natural sequence, analogs in which they have been replaced with phenylalanine should also be synthesized. This precaution reduces the possibility of labeling a potential anchor residue, or of producing doubly labeled peptides.

Sensitivity to size- and allele-specific motifs is also important. It has been widely reported in the literature that Class I ligands are of very specific size, and bear allele-specific motifs (for reviews see Sette and Grey, 1992; Barber and Parham, 1993; Germain, 1993; Germain and Margulies, 1993; Engelhard, 1994; Stern and Wiley, 1994; Madden, 1995; Rammensee et al., 1995). Peptides chosen for use as radiolabeled ligands for Class I assays should strictly adhere to these specifications. For Class II radiolabeled ligands, it has been the authors’ experience that long peptides (i.e., >18 residues in length) are often difficult to use from a separation standpoint, in the context of gel filtration assays, although they may still be suitable in the context of MHC capture assays. Ideally, peptides to be used as potential radiolabeled probes for Class II assays should be between 13 and 18 amino acids in length. Thus, it may be necessary to synthesize truncated analogs of known Class II–binding peptides.

Once a peptide that yields a detectable signal is identified, a larger panel of unlabeled peptides may be screened without having to label large numbers of peptides. From these panels, it may be possible to identify other ligands of even higher affinity, which may then be radiolabeled.

Assay validation

MHC molecules, in some situations, can yield low-affinity and artifactual binding. Thus, in the course of developing peptide-MHC binding assays, it is essential to validate them at both the biochemical and biological levels. Validity at the biochemical level is demonstrated by the specificity of the assay: the interaction should be inhibitable by an excess of unlabeled peptide ligand, and the peptide ligand should be capable of binding to some but not all MHC types. Conversely, it should also be demonstrated that the MHC molecule of interest binds some but not all peptide ligands.

The biological relevance of an assay may be established by assessing the correlation between binding specificity and MHC restriction. In most cases, peptides capable of eliciting a response restricted to a given MHC molecule will bind with relatively high affinity to that MHC molecule. For Class I alleles, this high-affinity binding has a threshold that appears to be ~500 nM (Ruppert et al., 1993; Sette et al., 1994; Sidney et al., 1995; Assarasson et al., 2007). For Class II, the threshold appears to be ~1 μM (Sidney et al., 1992, 1994; 2001a,b; Alexander et al., 1994; Southwood et al., 1998; Oseroff et al., 2010). Conversely, the failure to detect binding with a given MHC-peptide combination should correlate with a failure to detect a T cell response in the same context.

As an alternative approach, biological validity can be determined by measuring the correlation between the capacity of unrelated peptides to compete with antigen for MHC-restricted antigen presentation and their direct MHC binding capacity as measured in the binding assay. If the binding site involved in the interaction measured by the binding assay is the same site involved in the presentation of antigenic fragments to the T cell receptor, a good correlation should be observed (Buus et al., 1987, 1988; Lamont et al., 1990).

Troubleshooting

The assay system described in this unit is usually trouble free as long as fresh and high-quality reagents are used. However, there are some areas where problems may be encountered. Specific precautions and recommendations regarding these areas of concern are discussed briefly below.

MHC

While MHC can be purified from many different types of cell lines, EBV-transformed homozygous cell lines are usually the best first choice for human MHC. These lines are typically easy to grow, and have high expression of MHC. However, because MHC expression varies between cell lines, it is prudent to have more than one cell line available that expresses the desired molecule. Single-allele-transfected, HLA-deficient, 721.221 or RM3 lines, for Class I and Class II, respectively, are also excellent for MHC cultivation and purification. The purity and concentration of MHC preparations should also be monitored, thereby guaranteeing that each assay is as specific and sensitive as possible.

Support Protocol 1 describes the purification of MHC from cell lysates. However, the assay described here is fully amenable to MHC purified from other sources, such as the recombinant solubilized MHC produced in a hollow-fiber bioreactor, as described by Hildebrand (Buchli et al., 2004, 2005), or the E. coli expression system described by Buus (Ferre et al., 2003; Justesen et al., 2009; Harndahl et al., 2011). This type of material may also be purchased from Pure Protein, LLC.

Radiolabeled peptide

As with all other reagents used, fresh material presents the fewest problems. Na[125I] stocks less than 6 weeks old generally give the most reliable labels. While some labels will last up to a month, in most cases peptides should be relabeled after 2 weeks. Old and degraded labels often show HPLC profiles with wide or multiple peaks on gel filtration, or poor signal in the capture assay, and will decrease the sensitivity of the assay, in general.